RESPIRATORY DISTRESS IN

NEWBORN: TREATED WITH

VENTILATION IN A LEVEL II

NURSERY

A.K. Malhotra

R. Nagpal

R.K. Gupta

D.S. Chhajta

R.K. Arora

ABSTRACT

Fifty consecutive neonates with respiratory

distress persisting beyond 6 h of age were

studied during a 18 month period (total delive-

ries 2000/y). Twenty two neonates were mana-

ged with oxygen hood with increasing oxygen

concentration, 28 with continuous positive air-

way pressure (CPAP) ventilation using a nasal

cannula. Of these babies on CPAP, 10 were

shifted to intermittent positive pressure ventila-

tion (IPPV) on a pressure limited, time cycled

ventilator (Neovent, Vickers). Babies were

monitored with continuous hemoglobin oxygen

saturation (SaO

2

), hourly blood pressure and

vital charting. Radial arterial blood gas analysis

(ABG) was done when feasible and especially on

clinical deterioration. Oxygen (FiO

2

0.95) from

an oxygen concentrator was used as a source of

continuous supply of oxygen. Commonest cause

of respiratory distress was hyaline membrane

disease (18%), followed by wet lung syndromes

(14%), meconium aspiration (12%), asphyxia

(12%) and septicemia (8%). In 8 babies, a lung

biopsy (postmortem) was done to confirm the

diagnosis. Nineteen of the 50 babies with respi-

ratory distress died, there was a survival of 50%

on CPAP and 30% on IPPV. No case of oxygen

toxicity or other major complications was

encountered. Even with moderate resources,

neonatal ventilation in a Level II nursery is a

Respiratory distress is the most com-

mon problem in neonatal nurseries. It

results from a variety of causes and an

urgent work up is essential. Yet for

hypoxemia some form of assisted venti-

lation is immediately warranted. The

outlook of babies with respiratory dis-

tress syndrome has changed after the

first use of continuous positive airway

pressure (CPAP) by Gregory et al.(l). It

is now an established modality for neo-

nates for many years.

In India, a survival of 100% in babies

more than 1.5 Kg on CPAP mode is

reported(2). It is also recommended that

neonatal ventilation should be ventured

in centres where basic facilities for Level

II care already exist. Ours is a well

equipped nursery recognized by the

National Neonatology Forum (NNF).

We treated 50 babies with respiratory

distress, of which 31 survived.

Material and Methods

In a prospective study, we analyzed

the causes of respiratory distress and

indications for ventilation in newborns

during a 18 month period (Jan '92-June

'93). There were a total of 2931 booked

deliveries during this period in our hos-

pital which caters to a mixed Indian

challenging task. Babies less than 1000g require

aggressive measures which is not very economi-

cal in a special care baby unit (SCBU).

Key words: Neonatal ventilation, Respiratory

distress.

From the Neonatal Unit, Department of Pediat-

rics, Command Hospital, Pune All 040.

Reprint requests: Lt. Col. A.K. Malhotra, 174,

Military Hospital C/o 56 A.P.O.

Received for publication: October 2,1993;

Accepted: June 8,1994

MALHOTRA ET AL.

population. For the diagnosis of respira-

tory distress, the important signs are

respiratory rate more than 60 per

minute, grunt and sub-costal recessions.

These signs being non-specific, we con-

sider two out of three of these as

confirmative of respiratory distress(3).

Rarely, apneic attacks may present as a

sole manifestation of ventilatory failure.

As the spectrum of respiratory dis-

tress in newborns is large, we start a

workup at four hours of age and give a

provisional diagnosis at 6 hours of post

natal life. The initial workup included a

gastric aspirate shake test, chest X-ray

and an arterial blood gas (ABG) analy-

sis. Blood pressure and vital signs were

recorded. Oxygen saturation (SaO

2

) and

heart rate were monitored using a pulse

oximeter (Ohmeda Biox 3760). Oxygen

from a oxygen concentrator (Air Sep

Forlife) with FiO

2

0.95 was used to sup-

ply oxygen. Intravenous fluids were

started at the rate of 60 ml per kg body

weight of 10% dextrose solution. If clini-

cal condition warranted antibiotics,

blood cultures were taken prior in 10 ml

culture bottles. Downes RDS Score(4)

was recorded and babies with a score of

six or more were put on CPAP with a

nasal cannula (Argyle). Babies with a

score of five or less were managed with

oxygen hood with increasing FiO

2

con-

centrations.

The indication for giving CPAP were

(i) Downes score of 6 or more; (ii) inabi-

lity to maintain a SaO

2

of 87% with oxy-

gen hood; (iii) PaO

2

of less than 50 mm

Hg; and (iv) radiological evidence of

severe hyaline membrane disease

(HMD) with a negative shake test.

CPAP is considered a failure if a baby

has (i) inability to maintain a SaO

2

of

208

VENTILATION FOR RDS

87% with CPAP of 12 cm H

2

O and FiO

2

of 0.9; (ii) PaO

2

<50 mm Hg with FiO

2

0.9; (iii) pH <7.25, PaCO

2

>60 mm Hg;

and (iv) recurrent (more than 3) apneic

attacks as a manifestation of respiratory

failure. CPAP failures were shifted to

intermittent positive pressure ventila-

tion (IPPV) mode on a time cycled, pres-

sure limited continuous flow neonatal

ventilator (Neovent, Vickers). We use

minimal ventilatory settings depending

on the lung pathology to achieve a SaO

2

of 90±3% or PaO

2

60-80 mm Hg. Subse-

quent ABG was done through repeated

radial arterial punctures at 6-12 hourly

intervals. The definitions suggested by

NNF Group on Neonatal Nomencla-

ture(3) were accepted. Babies delivered

with a thick meconium stained liquor

were intubated prior to first breath. Sep-

ticemia was diagnosed if the blood cul-

ture grew pathogenic organisms. Imma-

turity was labelled when a baby less

than 1000 g had no other primary cause

of death.

Results

Out of the 50 babies enrolled in the

study, 26 were males and 24 females.

There were 40 babies with low birth

weight; of these 10 babies were less than

1000g. Mean birth weight was 1823 g

(range 740-3900 g) and mean gestational.

age 33 wk (range 26-42 wk). The smal-

lest baby a non survivor was 740 g with

a gestational age of 26 weeks. Table I de-

picts the modes of oxygenation. Twenty

two babies were managed with oxygen

hood and 28 required CPAP ventilation.

Of these 10 babies had a failure of CPAP

ventilation and were shifted to IPPV

mode. The mean duration of CPAP

mode was 53 h (range 11-156 h) and

IPPV mode 46 h (range 7-74 h).

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

Hyaline membrane disease (18%)

was the commonest cause of respiratory

distress, followed by wet lung syn-

dromes (14%), meconium aspiration

syndrome (12%), asphyxia (12%) and

VOLUME 32-FEBRUARY 1995

septicemia (8%) (Table II). There was one

baby 1000 g who developed chronic pul-

monary insufficiency of prematurity

(CPIP) and was discharged with a

weight of 1750g. In 8 cases (birth weight

MALHOTRAETAL.

900-2000g) with a clinical diagnosis of

HMD, the cause of death was confirmed

by a postmortem lung biopsy. In all

these cases, the histopathological fea-

tures were consistent with hyaline

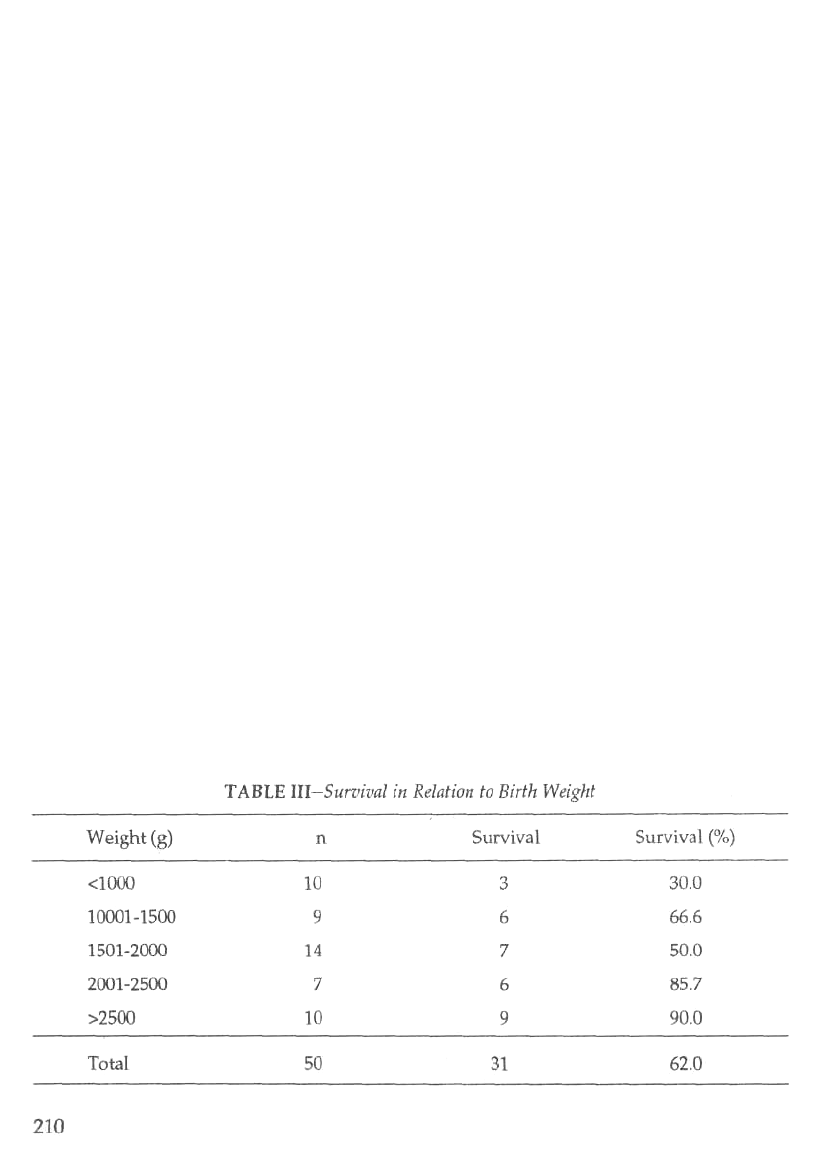

membrane disease. Table III depicts the

survival in relation to the birth weight

and mode of ventilation. There was a

50% survival on CPAP and 30% on IPPV

mode. Survival of babies less than 1000g

was 30%. Three babies had a symptom-

atic ductus arteriosus (PDA) and were

managed on standard lines. No baby

developed pneumofhorax or other

major complications of ventilation or

oxygen therapy.

Discussion

Majority of the medical colleges in

our country lack the basic infrastructure

to ventilate babies(2). Ventilation has

only been reported from tertiary centres

and experience from Level II nurseries

is lacking. We have the expertise but the

resources are limited. At the same time,

IPPV and aggressive monitoring results

in a significant iatrogenic morbidity.

Within the frame work of the physics of

ventilation every nursery evolves its

protocols and settings for ventilation.

VENTILATION FOR RDS

As oxygen is a drug, we choose a mid-

line path whereby the complications are

minimum. The CPAP mode with nasal

cannula is an easy way to improve oxy-

genation. This makes the routine endo-

tracheal intubation of infants requiring

only continuous airway distending

pressures no longer justifiable(5).

Once oxygenation is adequate and

signs of respiratory distress decrease, an

optimal CPAP is achieved. CPAP failu-

res appear to have an omnious progno-

sis regardless of the birth weight(5). In

our series, we had 10 babies less than

1000g and the mortality in them was

70%. CPAP is not an ideal treatment for

them and they may require IPPV at the

outset(2). Chronic pulmonary insuffi-

ciency of prematurity is a distinct entity

as these babies are less than 1000g and

have a normal chest X-ray at birth but

are oxygen dependent at 3-4 weeks of

age. We agree with Singh et al. in

considering a cut off of immaturity at

750 g(2). In a review of literature(5) the

incidence of pneumothoraces was 0 to

14%. We had no case of pneumofhorax

or other major complications of oxygen

toxicity.

INDIAN PEDIATRICS

Pulse oximetry is a reliable tech-

nique for monitoring of oxygenation in

newborns(6,7). It is a handy tool in a

Level II nursery as apart from SaO

2

it

displays the heart rate. It obviates the

use of an electrocardiograph and apnea

monitors. In managing cases of respira-

tory distress, it has few limitations and

the artifacts are avoidable. Fanconi et

al.(8) constructed oxygen dissociation

curves with pulse oximeter SaO

2

, mea-

sured SaO

2

and calculated SaO

2

; they

were all similar. A pulse oximeter read-

ing of 85% to 90% is a clinically safe tar-

get. We maintain a SaO

2

level of 90±3%

and titrate FiO

2

to that level. On clinical

deterioration and failure to maintain

saturation, an ABG helps in correcting

the acid base defect. As oxygen is

always at a premium in a Level II nur-

sery, oxygen (FiO

2

0.95) from an oxygen

concentrator is a useful equipment to

supply oxygen.

Getting a neonatal autopsy in India

is a difficult task. We have found a lung

biopsy done immediately after death an

easy method to come to a diagnosis. In 8

of our babies, biopsy showed features

suggesting HMD. Considering babies

more than 1000g, we have a survival of

70% and only 30% in less than 1000g.

These babies require aggressive mea-

sures which is not very economical in a

Level II nursery.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Director

General, Armed Forces Medical Ser-

vices, New Delhi for financial assistance

as part of AFMRC Project No 1912/92.

VOLUME 32-FEBRUARY 1995

REFERENCES

1. Gregory JZA, Kitterman JA, Phibbs

RH, et al. Treatment of idiopathic res-

piratory distress syndrome with con-

tinuous positive airway pressure. N

Engl J Med 1971, 284:1333-1341.

2. Singh M, Deorari AK, Paul VK, et al.

Three year experience with neonatal

ventilation from a tertiary care hospi-

tal in Delhi. Indian Pediatr 1993, 30:

783-789.

3. Singh M, Paul VK, Bhakoo ON. Neo-

natal Nomenclature and Data Collec-

tion. New Delhi, National Neonato-

logy Forum, 1989.

4. Downes JJ, Vidyasagar D, Morrow

GM, et al. Respiratory distress syn-

drome of infants I. New clinical sco-

ring system (RDS Score) with acid-

base and blood-gas correlction. Clin

Pediatr 1970, 9: 325.

5. Boros SJ, Reynolds JW. Hyaline mem-

brane disease treated with early nasal

and expiratory pressure: One year's

experience. Pediatrics 1975, 56:' 218-

223.

6. Jennis MS, Peabody JL. Pulse

oximetry: An alternative method of

assessment of oxygenation in newborn

infants. Pediatrics 1987, 79: 524-527.

7. Ramnathan R, Durand M, Larrazabal

C. Pulse oximetry in very low birth

weight infants with acute and chronic

lung disease. Pediatrics 1978, 79: 612-

616.

8. Fanconi S, Doherty P, Edmonds JF, et

al. Pulse oximetry in pediatric inten-

sive care: Comparison with measured

saturations and transcutaneous oxy-

gen tension. J Pediatr 1985, 107: 362-

366.

211