Recovery and resolution

for the EU insurance

sector: a macroprudential

perspective

August 2017

Report by the ATC Expert Group on Insurance

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Contents 1

Executive Summary 3

Section 1 Introduction 9

Section 2 Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution

framework for insurers 10

2.1 Introduction 10

2.2 Systemic risks in the insurance sector 10

2.2.1 Spillovers to other sectors 12

2.2.2 Cross-border spillovers 15

2.3 Systemic risks associated with a low interest rate environment 17

2.4 A recovery and resolution framework for insurers from a macroprudential

perspective 18

Section 3 International and European initiatives on recovery and resolution

for insurers 24

3.1 Introduction 24

3.2 Global initiatives 24

3.3 EU initiatives 28

3.4 Current status and recent initiatives at national level 30

Section 4 Recovery and resolution powers and tools 35

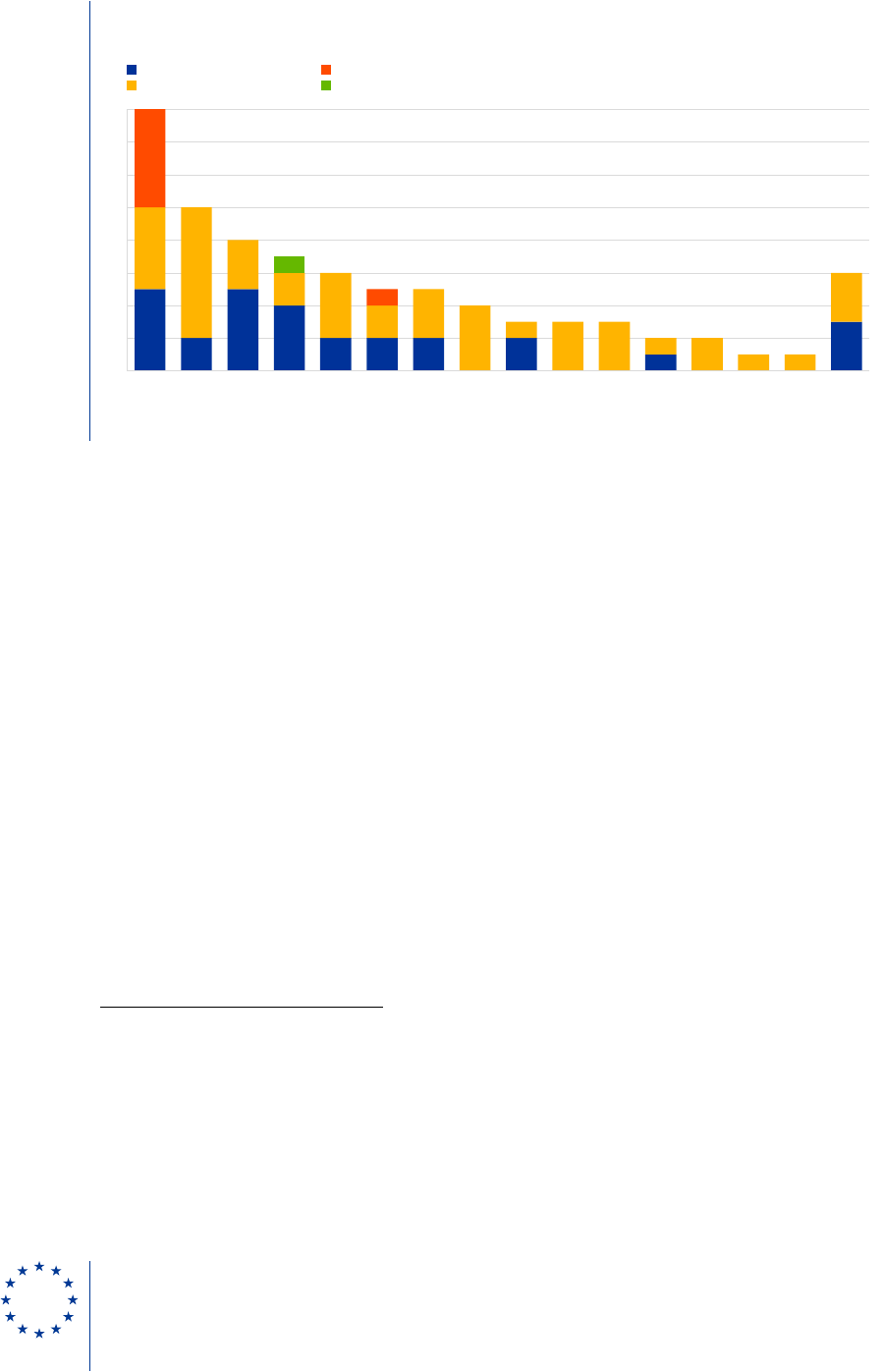

4.1 Introduction 35

4.2 Recovery and resolution planning 35

4.3 Recovery measures and early intervention tools 37

4.4 Resolution tools 38

4.4.1 Commonly used resolution tools 39

4.4.2 Resolution powers and tools that allow the business to be transferred

or separated 41

4.4.3 Resolution tools affecting contractual rights 45

4.5 Cross-sectoral implications of resolution measures 47

4.5.1 Stay on termination rights tool 47

4.5.2 Bail-in tool 48

Section 5 Resolution funding 50

Contents

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Contents 2

5.1 Introduction 50

5.2 Funding sources other than public funds 50

5.2.1 Resolution funded by a resolution fund 51

5.2.2 Resolution funded by an insurance guarantee scheme 52

5.3 Ex post and ex ante industry financing 55

Section 6 Role of the macroprudential authority 60

Section 7 Conclusions and possible ways forward 62

References 65

Abbreviations 69

Members of the drafting team 70

Imprint 71

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Executive Summary 3

1. This report focuses on a recovery and resolution (RR) framework for insurers

1

from a

macroprudential perspective. Covering primary insurers and reinsurers, the report

(i) discusses the need for comprehensive RR policies to complement supervisory and

macroprudential policies; (ii) identifies and describes a number of potential RR tools;

(iii) highlights funding aspects of the resolution process; and (iv) considers cross-sectoral and

cross-border implications and contagion channels that arise when resolution tools are applied.

2. The disorderly failure of an insurer or a group of insurers may pose financial stability

risks. Recent studies have shown that the contribution of the insurance sector, especially that

of the life insurance segment, to systemic risk has increased. This is, in particular, due to a

substantial common exposure to aggregate risk, caused partly by the ever more explicit

sensitivity of insurers’ balance sheets to interest rate volatility, and to its growing

interconnectedness with the rest of the system through financial markets, e.g. due to their

active role in the capital and, to some extent, derivatives markets. As a result, rather than

absorbing adverse shocks, the EU insurance sector may transmit and/or amplify shocks to

other parts of the financial system once negatively affected. Moreover, there are also strong

linkages between insurers. For example, the failure of a reinsurer will directly affect other

insurers. More generally, certain types of insurers, in particular non-life insurers offering

compulsory and sometimes niche insurance, provide essential services that are necessary for

the functioning of the real economy. The disorderly failure of an important insurer of this type

at short notice might lead to a temporary shortfall in supply and an inability to address the

needs of the real economy, leading to a stalling in goods supply.

3. The regular insolvency procedure might be unable to manage a failure in the EU

insurance sector in an orderly fashion. A broad set of tools, in addition to those related to

insolvency proceedings, may enable authorities to be better prepared to deal with situations

involving the distress and default of insurers. The regular insolvency procedure may not

always be consistent with policyholder protection and financial stability objectives. In contrast

to other resolution tools, it may not consider the continuity of critical functions or the

preservation of any other important functions.

2

As such, in the event of the failure of a large

insurer or the simultaneous failure of multiple insurers, it may not be possible to prevent

contagion spreading to other parts of the financial system. Moreover, following the regular

insolvency procedure, the settlement of policyholders’ claims could be delayed by several

years, possibly undermining the wider public’s trust in the EU insurance sector as whole.

4. Financial stability and policyholder protection objectives are equally relevant to an RR

framework in the insurance sector. The possibility of the simultaneous disorderly failure of

several life insurers cannot be disregarded at this juncture. A prolonged low interest rate (LIR)

1

Unless otherwise specified, this report uses the term “insurer” to collectively refer to insurers that directly insure businesses

and households (primary insurers) and insurers that provide insurance to other insurers (reinsurers). The terms “primary

insurer” and “reinsurer” are used when the text only applies to one type of insurer. Specific references are made to

differences in the business models of reinsurers and primary insurers, since reinsurers insure primary insurers (and other

reinsurers), but not private households.

2

The report advocates further discussion of critical functions in the insurance sector. For details, see Box 2.

Executive Summary

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Executive Summary 4

environment could lead to solvency problems throughout the life insurance sector, in particular

for life insurers that offered products with guaranteed returns at a time when interest rates

were higher.

3

In the very unlikely scenario that the LIR environment were combined with an

event of suddenly falling asset prices (a so-called double-hit scenario), there could be a risk of

life insurers in several countries coming under stress simultaneously. Even if no failing insurer

were systemically important on its own, the disorderly simultaneous failure of several insurers

could, collectively, pose a risk to financial stability. Against this background, this report argues

that financial stability aspects should be considered as part of insurance RR frameworks,

together with policyholder protection objectives.

5. An effective RR framework needs to take a sectoral view, while allowing for the

principle of proportionality. The international effort has so far focused on global

systemically important insurers – nine global systemically important insurers (G-SIIs) have

been designated by the FSB, with five of these domiciled in the European Union (EU). G-SIIs

are subject to an enhanced RR framework, used primarily as a tool to address the “too-big-to-

fail” issue. There are, however, multiple challenges, such as the LIR affecting the sector as a

whole. Moreover, in addition to considering the financial stability implications related to a

disorderly failure of a single insurer, systemic risks arising from common exposures should

also be taken into account. In the LIR environment some institutions may prove unable to

successfully adjust their business models to new challenges and, if all other regulatory

measures fail, their orderly exit should be assured. This suggests that regulatory attention

should focus on the overall sector, including smaller and less diversified insurers which might

threaten financial stability if they failed simultaneously in a disorderly manner. Nevertheless,

the benefits of a RR framework with a broad scope need to be weighed against the additional

costs, allowing national authorities to follow the principle of proportionality.

6. An effective RR framework also requires arrangements to fund resolution without

having to resort to public funds. In some EU Member States the existing national

frameworks might have difficulty to avoid the event of the disorderly failure of a large insurer

or the simultaneous disorderly failure of several insurers without having to resort to public

funds. An undesirable alternative to the use of public funds would be a policyholder-funded

bail-in, with policyholders losing a significant part of their investments, which could have

widespread negative implications for sovereigns and financial markets. Moreover, if the

insurance guarantee schemes (IGSs) are not properly equipped to compensate policyholders

for their losses, public trust might also suffer.

7. Differences between national legislations increase the complexity of ensuring that the

failure of an insurer active in several EU Member States can be managed in an orderly

manner. The recent crisis has illustrated the consequences of a lack of effective crisis

management for financial institutions that are active across borders. Following the saying

“international in life and national in death”, the authorities in individual jurisdictions have the

power which could be applied only at the level of local entity rather than at the level of cross-

border group. As in the banking sector, large and internationally active groups play an

important role in the insurance sector in the EU, while reinsurers from the EU play a leading

3

As shown by the EIOPA 2016 insurance stress tests, both explicit and implicit guarantees are of relevance. For the

distinction of contractual guarantees, please consult the IAIS report on Systemic Risk from Insurance Product Features

(IAIS 2016b).

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Executive Summary 5

role in the global market. At the same time, however, national insolvency procedures,

insurance RR frameworks and national IGSs continue to differ widely across the EU. Although

this allows national authorities to account for national specificities, a patchwork of national

rules cannot fully take account of the cross-border implications of a complex failure. This could

result in legal uncertainty, unequal treatment of domestic and foreign policyholders, potential

spillover effects into host countries and competitive distortions of national actions. The cross-

sectoral implications of the failure scenario, particularly in the case of a financial conglomerate

active across borders, would increase the complexity even further. This indicates that the

harmonisation of the EU RR framework for insurers across the EU would be a step in the right

direction.

8. While a comprehensive RR framework for the banking sector is operational at EU level,

an EU-wide policy strategy addressing risks related to the insurance sector is lacking.

Whereas the Solvency II Directive is a major step forward in the enhancement of the Single

Market, no EU legislation has been proposed, in respect of an RR framework for insurers or

IGSs. Filling this regulatory gap will require a broad range of stakeholders in Europe to work

together, including EU and national legislators, EIOPA, macroprudential authorities and

microprudential regulators. The possibility of an LIR environment continuing for a protracted

period of time underlines the fact that the work to develop, strengthen and harmonise an

effective RR framework for insurers at EU level should be reinvigorated and include

consideration of the related funding aspects.

9. The report considers a number of RR tools for the EU insurance sector. The tools

considered in this report vary in terms of their costs and benefits, implications for the different

stakeholders and applicability in the EU insurance sector. They are grouped as shown below,

reflecting how, and at what stage of an insurer’s distress or failure, they may be used.

• RR planning. The Solvency II framework includes provisions that require insurers that

breach their Solvency Capital Ratio (SCR) to prepare recovery plans (“ex post recovery

plans”). However, this report stresses that pre-emptive RR plans can increase

awareness (e.g. in terms of recovery capacity, resolvability and obstacles to the

resolution of an insurer) and might thus support more decisive action by both insurers

and supervisors if the solvency position of an insurer deteriorates. This indicates that

more attention should be devoted to the RR planning phase during “good” or normal

times and that supervisors’ powers should be aligned with this principle.

• Recovery measures and early intervention tools. Financial stability and consumer

protection are best served if the failure of an insurer can be avoided by applying

recovery measures (designed and implemented by insurers) and early intervention tools

(available to home authorities). Some early intervention tools are already available in

individual EU Member States. However, they typically only allow supervisory authorities

to intervene once solvency requirements have been breached. This might prevent

supervisory authorities from intervening in a timely manner. The expansion and

harmonisation of early intervention tools would help supervisors in individual EU Member

States to limit disruption to the wider financial market and would limit the unnecessary

destruction of value.

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Executive Summary 6

• Commonly used resolution tools. Liquidation (as part of regular insolvency proceedings)

and run-off,

4

which is an insurance-specific resolution tool, are the most frequently used

and broadly available tools across the EU. They come, however, with a number of

deficiencies. Liquidation does not ensure the continuity of critical functions or the

preservation of other functions, it sometimes has priorities that differ from policyholder

protection and financial stability, and it is a time-consuming process. Despite these

shortcomings, liquidation remains a valid resolution tool – e.g. in conjunction with other

resolution tools discussed in this report. A run-off can ensure continuity of cover for

existing policyholders. It also does not require the fire sale of assets, thereby reducing

the destruction of value for policyholders. However, it may result in a partial settlement of

claims if not used in conjunction with other resolution tools discussed in this report.

Given the benefits to financial stability of the continuity of critical functions, the use of

run-off should be available across the EU and should include solutions to address any

funding shortfalls that might occur.

• Resolution tools that allow the transfer or separation of all or part of the portfolio.

Portfolio transfer, separation of assets and liabilities, and the use of bridge institutions

are considered in this report. With the exception of portfolio transfers, these tools are not

currently widely available in the EU for the resolution of an insurer. They increase the

resolution authority’s flexibility in identifying and separating viable business and/or vital

economic functions and liquidating the remainder under ordinary liquidation proceedings.

• Tools affecting contractual rights. The bail-in tool and the power to impose restrictions on

the termination of contracts are also considered in this report. These tools interfere with

contractual rights and have therefore been used rarely in the EU. The rationale for

imposing restrictions on the termination of contracts is to give the resolution authorities

the time to deal with a distressed insurer. The bail-in tool involves the restructuring,

limiting or writing down of liabilities and, at the same time, allocates losses to

shareholders and creditors, including policyholders, in a transparent manner. In contrast

to the ordinary insolvency procedure, it ensures the continuity of the critical functions and

viable parts of the insurer. The introduction of the bail-in tool is under consideration in

the Netherlands, and a few EU Member States allow policyholders to restructure

liabilities for the purpose of portfolio transfer. Further consideration could be given to the

option of granting the authorities in charge of resolution the powers to restructure, limit or

write down liabilities, including both insurance and non-insurance liabilities. The report

recognises that, due to the particular structure of insurers’ balance sheets, the bail-in tool

is probably less effective in the insurance sector than in the banking sector, when

applied to capital or debt. Still, the change to insurance liabilities should be a measure of

last resort and with adequate safeguards and a reliable source of funding in place to

ensure protection of policyholders. This could include the power to modify the terms of

existing contracts, for example, for life and saving contracts by reducing guaranteed

rates of return or by reducing benefits by a specified percentage.

10. The report highlights the relevance of insurance industry-funded arrangements for an

effective resolution process. Any failure and the related resolution process, including the

normal insolvency procedure, is associated with significant costs. Against this background, the

4

In the context of resolution, a run-off as a voluntary decision of the company is not viewed as a resolution tool.

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Executive Summary 7

expansion and/or creation of funding arrangements should be assessed as part of any

discussion on RR tools. Dedicated resolution funds (RFs) or insurance guarantee schemes

(IGSs) are two possible sources of funding for resolution, and the costs of these are directly

borne by the industry. At this juncture, Romania is the only country in the EU with an

operational RF, whereas IGSs operate in the majority of EU Member States, albeit often with

limited scope for specific insurance policies. Moreover, the possible use of IGSs beyond

compensating policyholders is mostly restricted to the use of a limited number of resolution

tools (mostly portfolio transfer) and focused on a single objective of policyholder protection.

Taken together, the current funding arrangements appear incomplete and, in the event that a

default of an insurer or several insurers were to pose risks to financial stability, the need to

resort to public funds would be very likely. The report argues that both IGSs and RFs can play

an important and complementary role in the resolution process

5

and that their use could be

further explored at EU level. Notwithstanding the role IGSs could play in resolution funding,

the question of adequate policyholder protection across the EU also warrants further attention

(ESRB 2017).

11. Any resolution action should pay attention to the significant cross-sectoral spillover

effects of the resolution tools applied. For example, the application of a stay on termination

rights could impact counterparties through open derivative positions. The report recognises

that the application of the bail-in tool increases interconnectedness across sectors and,

therefore, the consistency of resolution regimes across sectors should be further evaluated

and improved. This would guarantee the effectiveness of the tools and minimise the costs and

cross-sectoral spillovers of resolution actions, particularly in the case of financial

conglomerates.

12. The interaction between resolution and macroprudential authorities poses some

practical challenges. This report argues that ongoing interaction between the resolution

authority and other stakeholders, in particular the supervisory and macroprudential authorities,

is desirable, and this interaction should be decided prior to any crisis. However, the process of

assigning responsibilities during a failure could be hampered by the fact that a resolution

authority for insurers has not been designated in most EU Member States.

13. Against this background, this report advocates the development of a harmonised

effective RR framework for insurers across the EU. This includes the following:

• Existing RR frameworks should be evaluated and, if appropriate, enhanced and

harmonised at EU level. Furthermore, efforts should be made to ensure their consistent

implementation.

• The existing RR toolkit should be expanded and the multiple use of RR tools should be

allowed. A majority of ESRB member institutions take the view that this should include

giving resolution authorities the power to modify the terms of existing contracts as a

measure of last resort and subject to adequate safeguards.

• The RR framework should cover the whole insurance sector, while allowing for

proportionality.

5

The existence of IGSs can provide compensation for policyholders where losses are too burdensome and the existence of

a resolutions funds (RFs) for cases when compensation is needed in line with the no creditor worse off (NCWO) principle.

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Executive Summary 8

• The financial stability objectives of the RR framework should be recognised, with a

majority of ESRB member institutions taking the view that it should be put on an equal

footing with the objective of policyholder protection. In addition, the interactions of the

resolution authority with the macroprudential authorities should also be clarified.

• Lastly, work on RR frameworks should go hand-in-hand with a discussion of how

resolution should be funded.

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Introduction 9

14. The global financial crisis revealed, amongst other fault lines, the shortcomings from a

financial stability perspective of a government bailout and normal insolvency

procedure. Although a government bailout mitigates contagion both within a sector and in

terms of its spread to other financial sectors, the associated increase in sovereign debt

creates substantial cost to current and/or future taxpayers. It also increases the risk of moral

hazard. The crisis also showed that a normal insolvency procedure can lead to spillovers such

as concerns about the liquidity and solvency positions of other market participants with similar

business models or asset holdings. These self-perpetuating dynamics then become an

important driver of market developments, leading to a systemic crisis and a generalised loss

of confidence in the financial system.

15. Recovery and resolution frameworks have been developed to address these

shortcomings. Since the crisis, new legislation has been put in place – at both global and EU

level – with the aim of making financial institutions more robust and reducing their risk of

failure. Moreover, new recovery and resolution (RR) tools are being developed to enable

authorities to intervene more effectively prior to a failure and, when institutions do fail, to

resolve them in an orderly manner that does not require taxpayer support and that minimises

the impact on financial stability. While the EU-wide RR framework for the banking sector is

operational and some EU Member States are in the process of strengthening their national

RR frameworks for insurers, no EU legislative proposal has been put forward for an RR

framework in the insurance sector.

16. This report aims to contribute, from a macroprudential perspective, to the ongoing

debate in the EU on the RR framework for insurers. Building on previous ESRB positions,

6

and the recent ESRB Secretariat staff response to the EIOPA Discussion Paper (ESRB 2017),

the report (i) discusses the need for comprehensive RR framework to complement supervisory

and macroprudential policies; (ii) identifies and describes a number of potential RR tools;

(iii) highlights funding aspects of the resolution process; and (iv) considers cross-sectoral and

cross-border implications and contagion channels.

6

See ESRB (2015), ESRB (2016a) and ESRB (2016b).

Section 1

Introduction

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 10

2.1 Introduction

17. This section describes systemic risks in the insurance sector and makes the case, from

a macroprudential perspective, for an EU recovery and resolution framework for

insurers. The first subsection reviews the relevance of insurance from a macroprudential

perspective, thereby laying the foundations for the discussion in the remainder of the report. It

highlights the possible occurrence of spillover effects in other (financial) sectors and other

countries when an insurer is in distress or fails. The second subsection analyses the impact of

a low interest rate (LIR) environment, while the final subsection sets out arguments for and

against strengthening existing frameworks in EU Member States and supports the

development of an EU-wide, harmonised RR framework.

2.2 Systemic risks in the insurance sector

18. A well-functioning insurance sector contributes to economic growth and financial

stability. Insurers play an important role in the economy as providers of protection against

idiosyncratic, financial and economic risks. With liabilities standing at one-third of EU

households’ wealth, consumers depend on the insurance sector for their future income.

Moreover, with assets worth two-thirds of EU GDP, the EU insurance sector is a significant

part of the financial sector and one of the largest institutional investors (ESRB 2015). In

particular, insurers are an important source of long-term funding, and their long-term

investment strategy can – in principle – enable them to act as shock absorbers in financial

markets (IMF 2016).

19. However, the sector may also pose systemic risks. The ESRB previously identified four

main transmission channels of systemic risk: (i) insurers amplifying shocks due to their

involvement in so-called non-traditional and non-insurance activities (NTNI); (ii) insurers acting

procyclically in terms of investment and pricing; (iii) the collective failure of life insurers under

a scenario of prolonged low risk-free rates and suddenly falling asset prices (i.e. “the double

hit”); and (iv) a lack of substitutes in certain classes of insurance vital to economic activity

(ESRB 2015).

20. The contribution of the insurance sector to systemic risk has increased since the

financial crisis. Although the systemic risk associated with a default by individual insurers

has changed little, the contribution of the insurance sector as a whole to systemic risk has

increased in recent years (IMF 2016a). This increase is associated with higher commonalities

in exposures to aggregate risk within the insurance sector and with the rest of the financial

sector, as well as greater exposure to market risks through asset and liability (duration)

mismatches, induced by increased sensitivity of certain types of insurers to interest rates. The

changing nature of insurance activities, both in terms of investments and product offerings

(e.g. a switch to unit-linked/defined contribution models for life insurance or the increased use

of early cancellation clauses), has resulted in greater commonality across the financial

Section 2

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery

and resolution framework for insurers

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 11

system. It thus follows that insurers may be more likely to perform poorly when other parts of

the financial system are also facing difficulties.

Box 1

Systemic risks of reinsurers

Reinsurers traditionally transfer risk within the insurance sector. They are important to the

global insurance industry in that they provide a mechanism by which the risks of a cedent (local

primary insurers or other reinsurers that cede certain risks to a reinsurer) can be pooled. As a

result, the cedent is protected from extreme events and “tail losses” on its own exposures as

specific underwriting (or targeted market) risks are transferred to a reinsurer. This system not only

allows insurers to limit potential losses from an individual policy contract (or from a portfolio of

policies), but also to increase underwriting capacity and achieve a targeted risk profile (e.g. by

reducing risk concentration). By spreading insurance risks globally, reinsurance diversifies losses

stemming from local insurance markets, while providing capital relief and balance sheet protection.

While the reinsurance industry is small in comparison with the primary insurance industry, it still

plays an important role in the non-life sector.

Reinsurance may also be a source of concern for financial stability. Although the ways in

which reinsurers and primary insurers may pose systemic risks are similar, there may be features

specific to reinsurance which need to be monitored from a financial stability perspective (ESRB

2015). The ESRB previously identified the following systemic risks posed by reinsurance: (i) intra-

industry interconnectedness with both primary insurers and other reinsurers (known as ‘reinsurance

and retrocession spirals’),

7

increasing the risk of contagion within the insurance sector; (ii) the risk

arising from high market concentration of reinsurers, both globally and in the EU, and the related

substitutability issue, which may lead to a risk of market friction in the event of a reinsurer failing;

(iii) interconnectedness with the rest of the financial system and possible procyclical investment

behaviour and (iv) captive reinsurance (ESRB 2015).

Not much is known about the systemic risk posed by the failure of a reinsurer, although

there are indications that it might have increased. Little is known about the pattern and degree

of damage caused by the failure of a reinsurer as there have been few such events in the past.

Indeed, major risk events in recent years have demonstrated the well-designed risk-absorbing

capacity of the global reinsurance market, with little spillover effects. However, several metrics

indicate that the likelihood of a failure might have increased, and the spillover effects for the whole

insurance sector might be more severe than those observed in the past. First, the reinsurance

business has become more concentrated, with the top five reinsurers accounting for more than half

of the reinsurance capacity worldwide.

8

This process has led, to better diversified portfolios across

risks and regions, including additional benefits of economics of scale, although it might also

increase the risk that reinsurers have become too-big-to-fail. Second, the ratings of reinsurers’

7

Insurance market spirals, both reinsurance spirals and retrocession spirals, arise from the interplay of practices employed

by the insurance industry to disperse risk and spread it across other insurers. Reinsurance spirals refer to links between

primary insurers and reinsurers whereas, whereas retrocession spirals refer to links between reinsurers themselves.

8

The top five reinsurers accounted for 53% of the market in 2015, up from 51% in 2010 (A.M.Best 2010 and A.M.Best 2015).

From a longer-term perspective, the top five reinsurers in 2009 accounted for roughly the same amount of the market as

the top ten reinsurers in 1998 (roughly 52%). In 1991, the top ten reinsurers accounted for 35% of the market (Cummins

and Weiss 2014).

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 12

financial strength have deteriorated in recent years and, although they are still characterised by a

high degree of robustness, their outlook is negative (A.M.Best 2016). Furthermore, a change in

business practices, such as the increased use of a special termination clause (e.g. with respect to

rating triggers in reinsurance contracts) might exacerbate the problem of reinsurance and

retrocession spirals.

9

2.2.1 Spillovers to other sectors

21. Insurers can transmit shock across financial markets. Within Europe and North America

respectively, there could be large spillovers a between different sectors, including insurers. In

Asia, non-life insurers and reinsurers seem to be highly interconnected with other sectors in

the region. In terms of spillovers across the regions, Europe and North America appear to be

the most interconnected, with insurers (in particular life insurers) from Europe having a high

potential to transmit spillovers to the American financial market (IMF 2016a).

10

A separate

analysis for Europe indicated that, before the global financial crisis, insurers were recipients of

spillovers from other sectors although, more recently, they seem to have become a source of

spillovers (IMF 2016a).

22. Insurers may pose systemic risks arising from their funding and investment activities.

Collectively, insurers are among the largest investors in financial assets in the EU. They can

contribute to systemic risks through various channels, which include taking up more risks,

increasing commonality in asset composition within the financial sector, leading to increased

exposure to common shocks (“tsunami risk”), or increasing procyclicality in their investment

behaviour. For instance, analysis by the Bank of England concludes that the systemic risk

associated with activities of the UK insurance sector that propagate or amplify shocks to

financial counterparties or markets may be the greatest source of systemic risk from insurers

for the UK (French et al 2015).

23. Disruption to systemically important financial counterparties can occur if these

institutions no longer have access to funding from EU insurers. Insurers hold large

amounts of debt securities and shares issued by banks and other financial institutions in the

EU. From the perspective of banks’ balance sheets, these accounted for 4% of total bank

funding in the euro area in 2014 (ESRB 2015), while, on average, around 13% of debt issues

by euro area banks is held by insurers domiciled in the euro area and Sweden.

11

This figure is

even higher in some EU Member States, e.g. 28% in Belgium, Greece and Slovakia and 37%

in France. The ECB has emphasised that contagion risks from ownership links to banks and

other financial institutions are among the most significant risks (ECB 2008). Insurers also

9

Insurance market spirals, whether reinsurance spirals or retrocession spirals, arise from the interplay of practices employed

by the insurance industry to disperse risk and spread it across other insurers. While reinsurance spirals may impact primary

insurers, retrocession spirals may trigger failures of multiple reinsurers at the same time, which would also have a further

impact on a wide range of primary insurers.

10

According to the IMF, spillovers are defined as the impact of changes in asset price movements (or their volatility) in one

region/sector on asset prices in other regions/sectors, and are measured as each region’s/sector’s contribution to the total

residual variance of the equity returns of all other regions/sectors.

11

From the perspective of the insurers, 18% of the total financial assets of EU insurers in 2014 were investments in bank

bonds (ESRB 2015).

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 13

place deposits with banks which can easily be withdrawn

12

and may lend cash to banks and

other financial institutions through repo transactions. Taken together, if the funding activities of

EU insurers were to cease abruptly on large scale, this could pose a systemic risk to other

parts of the financial system.

24. Insurers’ growing participation in capital markets and their increased “non-core”

activities seem to be the main reasons for their growing links with the rest of the

financial sector. According to the IMF, as a result of increased exposure to man-made

catastrophes (such as terrorist attacks) and through the concentration of insurance risks in

danger zones, insurers have been turning more frequently to capital markets and alternative

risk transfer (ART) mechanisms to mitigate the impact of catastrophes on their balance

sheets.

13

This has increased their links with the rest of the financial sector, including the

banks, which act as counterparties to ARTs, albeit that the amount of these transactions is

low. Insurers are interconnected with other financial market participants through credit default

swaps and securities lending, which caused major spillovers during the financial crisis.

14

They

are also interconnected through derivatives trades, in particular interest rate swaps (Abad et al

2016). Moreover, insurers participate in capital markets to diversify risk via credit-linked

securities (Baluch et al 2011). It also seems likely that these links may be attributed to the

“non-core” or “banking-like” activities of insurers, such as the provision of financial guarantees,

asset lending, issuing credit default swaps, investing in complex structured securities, and an

excessive reliance on short-term sources of financing (Cummins and Weiss 2014).

25. Procyclical investment behaviour by insurers could make them more likely to transmit

shocks, albeit that evidence to date has been mixed. Procyclical investment behaviour by

insurers as a group may exacerbate the tendency for financial markets to experience “booms”

and “busts”. The capital position of other financial and non-financial institutions could then

deteriorate by a fall in the market prices of financial assets held, which could lead to second-

round effects resulting from fire sales and liquidity spirals (Brunnermeier and Pedersen 2009).

Evidence of insurers in the EU demonstrating procyclical investment behaviour has so far

been mixed (Bank of England and Procyclicality Working Group 2014; Bijlsma and Vermeulen

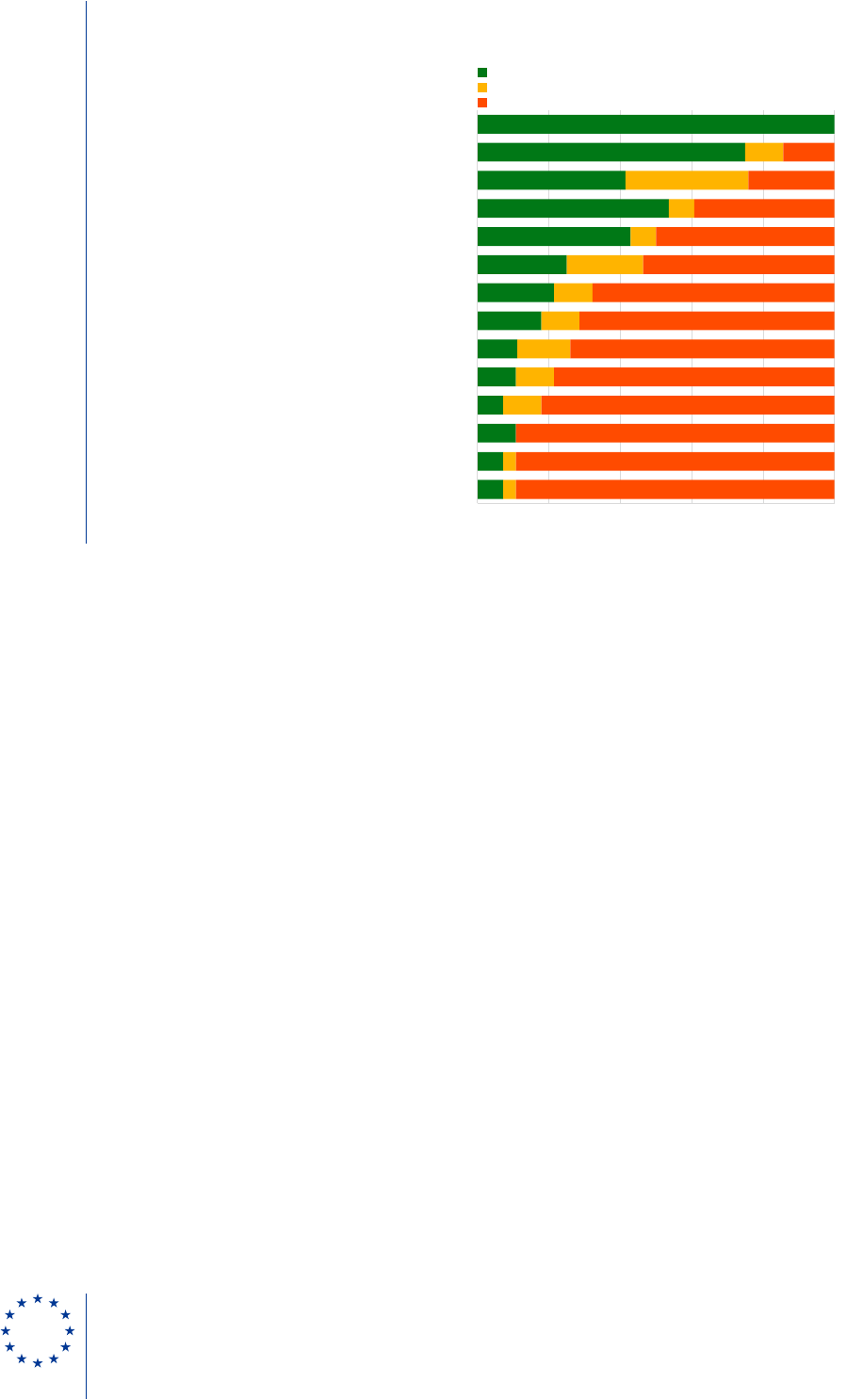

2015, Timmer 2016).

26. Some insurers are directly interconnected with other parts of the financial sector since

they are part of financial conglomerates. There were 83 financial conglomerates in Europe

in 2016, up from 75 in 2009 (Joint Committee of European Supervisory Authorities 2016).

Insurer-led conglomerates are the second most common type of conglomerate after bank-led

conglomerates (Chart 1) – an insurance entity often forms part of a bank-led conglomerate,

since those conglomerates traditionally follow a bancassurance model. They are also present

in conglomerates led by asset managers or pension funds, which have gained prominence

over the last decade. In general, insurer-led conglomerates tend to be smaller than bank-led

conglomerates (European Commission 2010c) and some of these only operate locally. At the

same time, the 30 largest financial conglomerates, most of which have an insurance entity,

12

This was, for example, the case in Greece in 2014 (ESRB 2015).

13

The data on ART is for the US insurance sector only. There is a lack of EU data on this.

14

See, for example, Cummins and Weis (2014); Dungey et al (2014) and Pierce (2014).

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 14

belong to the biggest financial groups in Europe: ten of the 13 EU G-SIBs and three out of five

EU G-SIIs are also financial conglomerates.

15

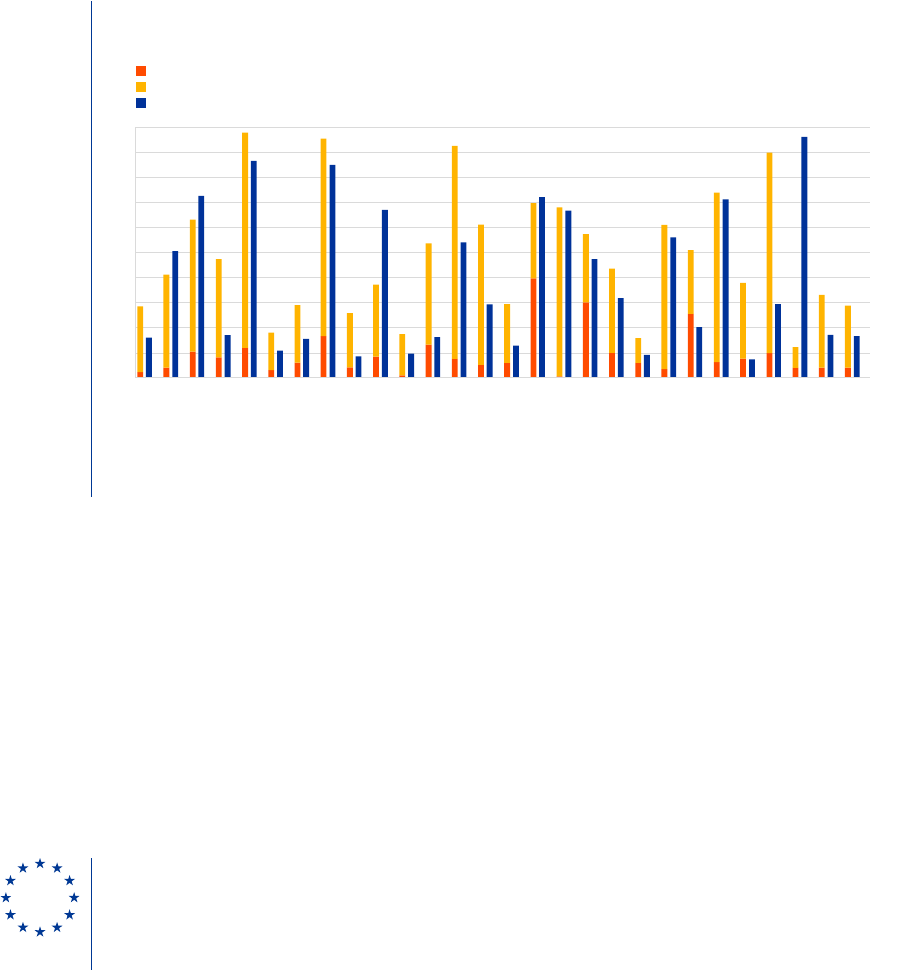

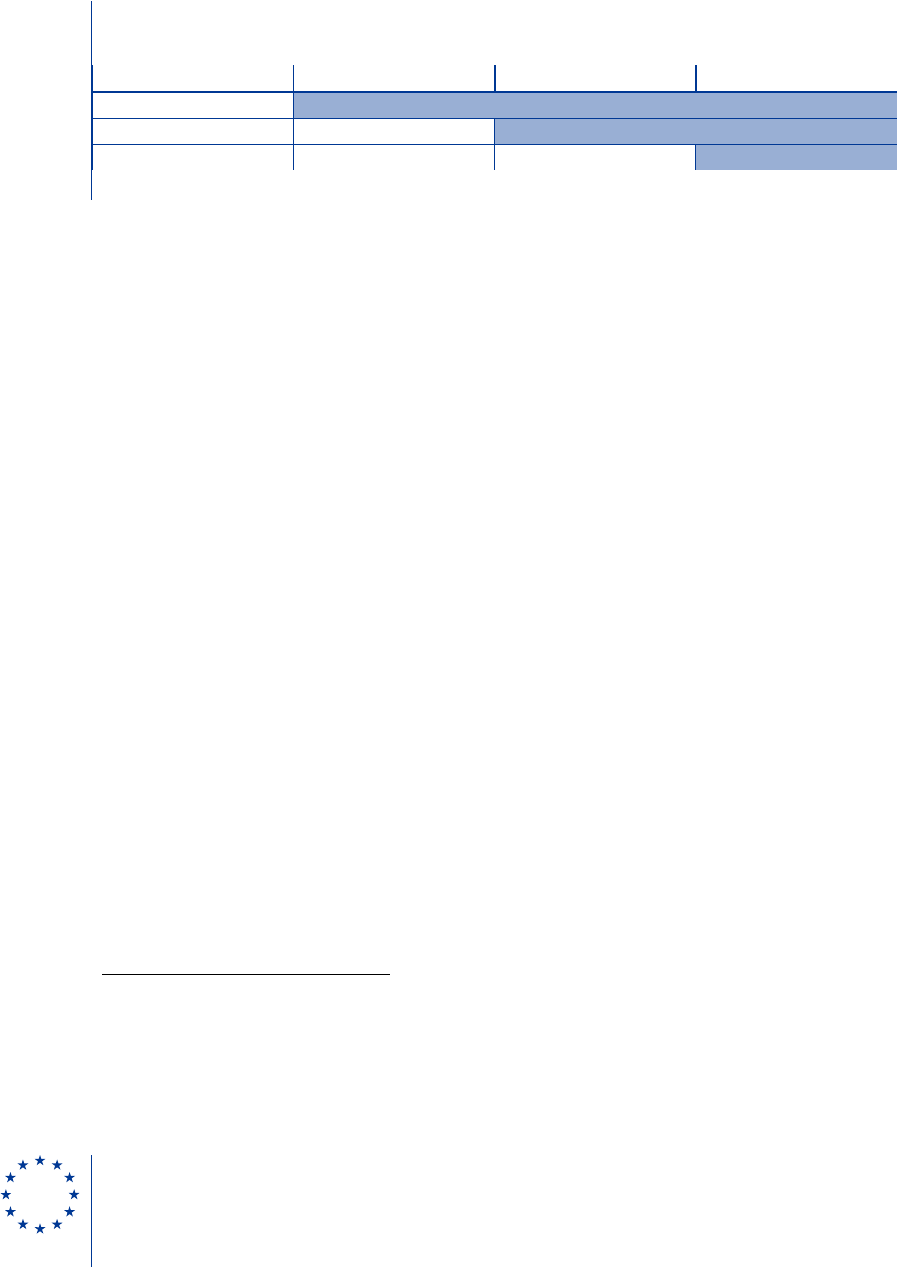

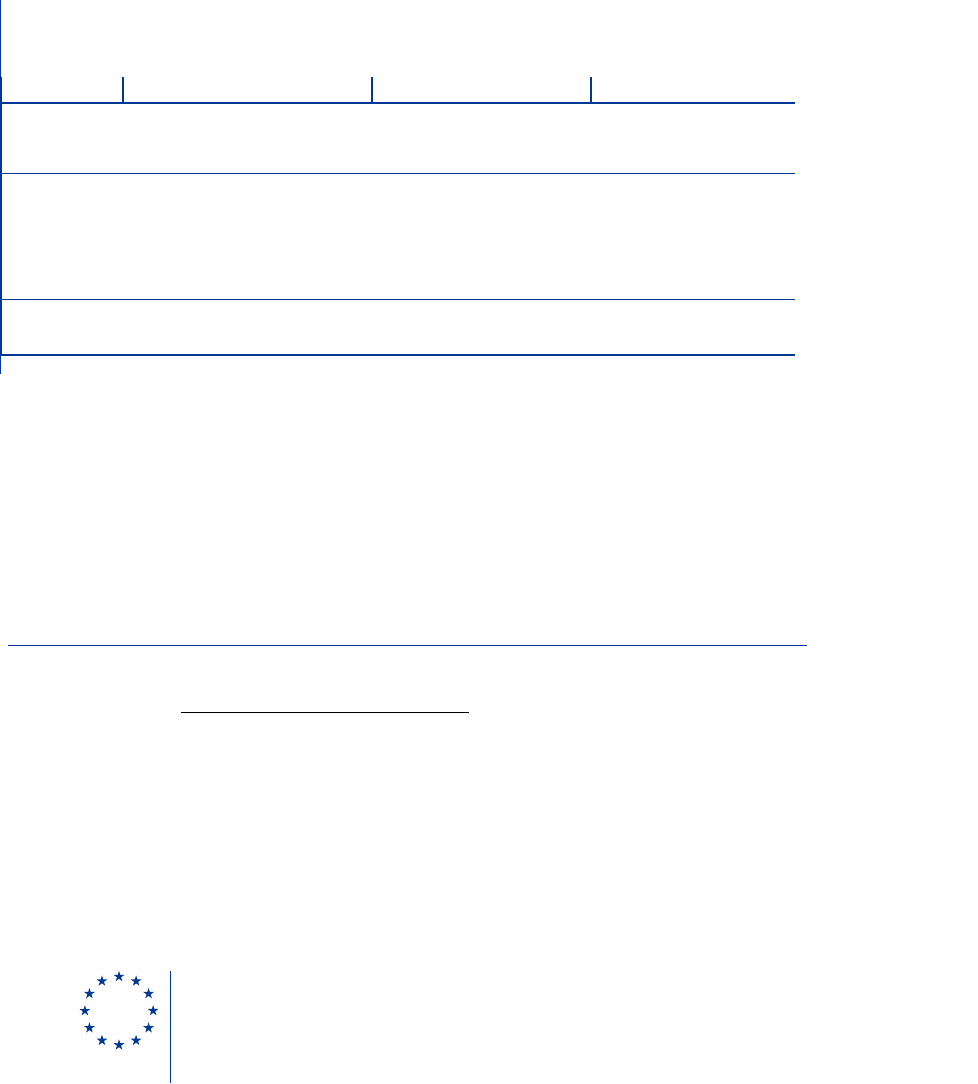

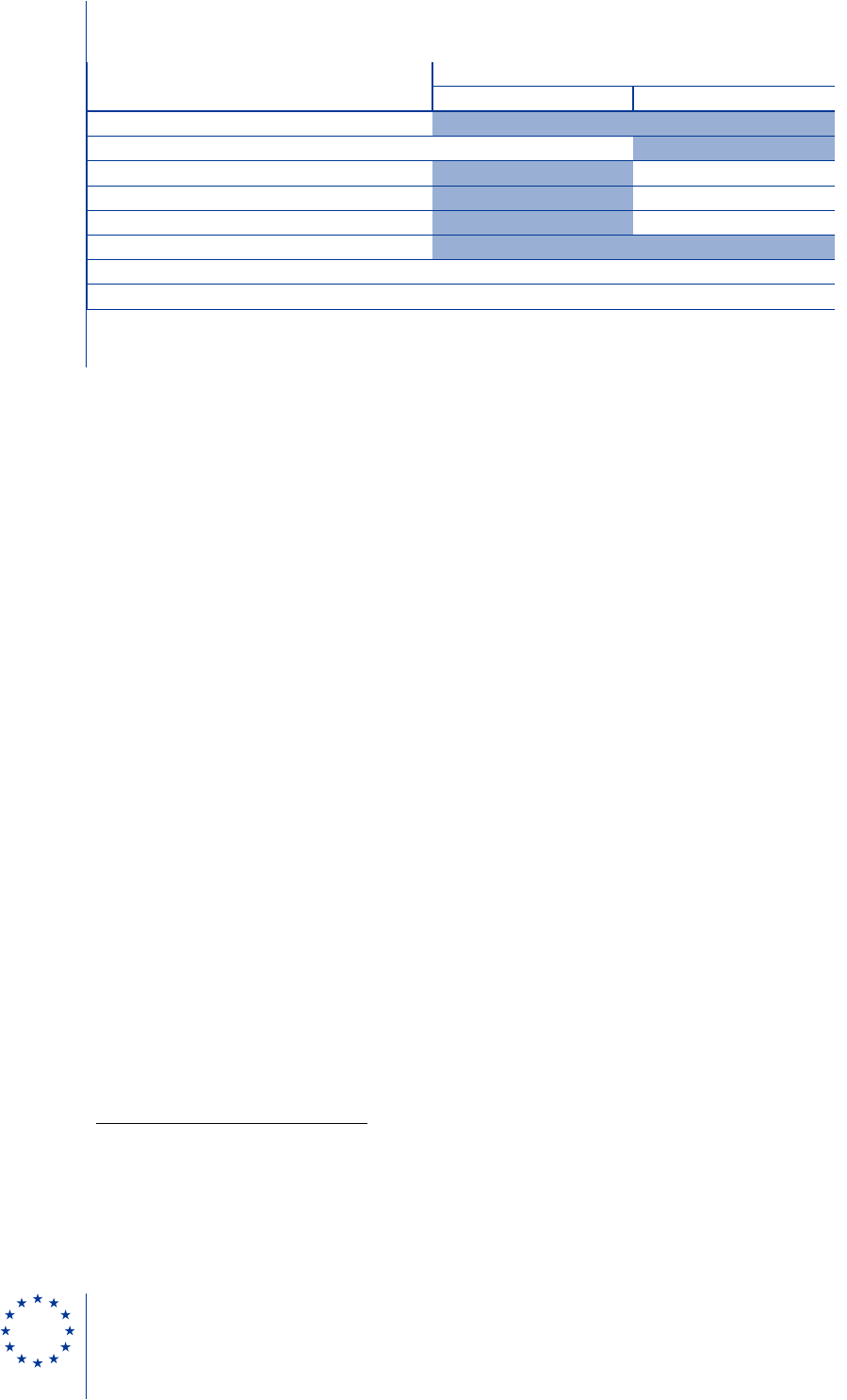

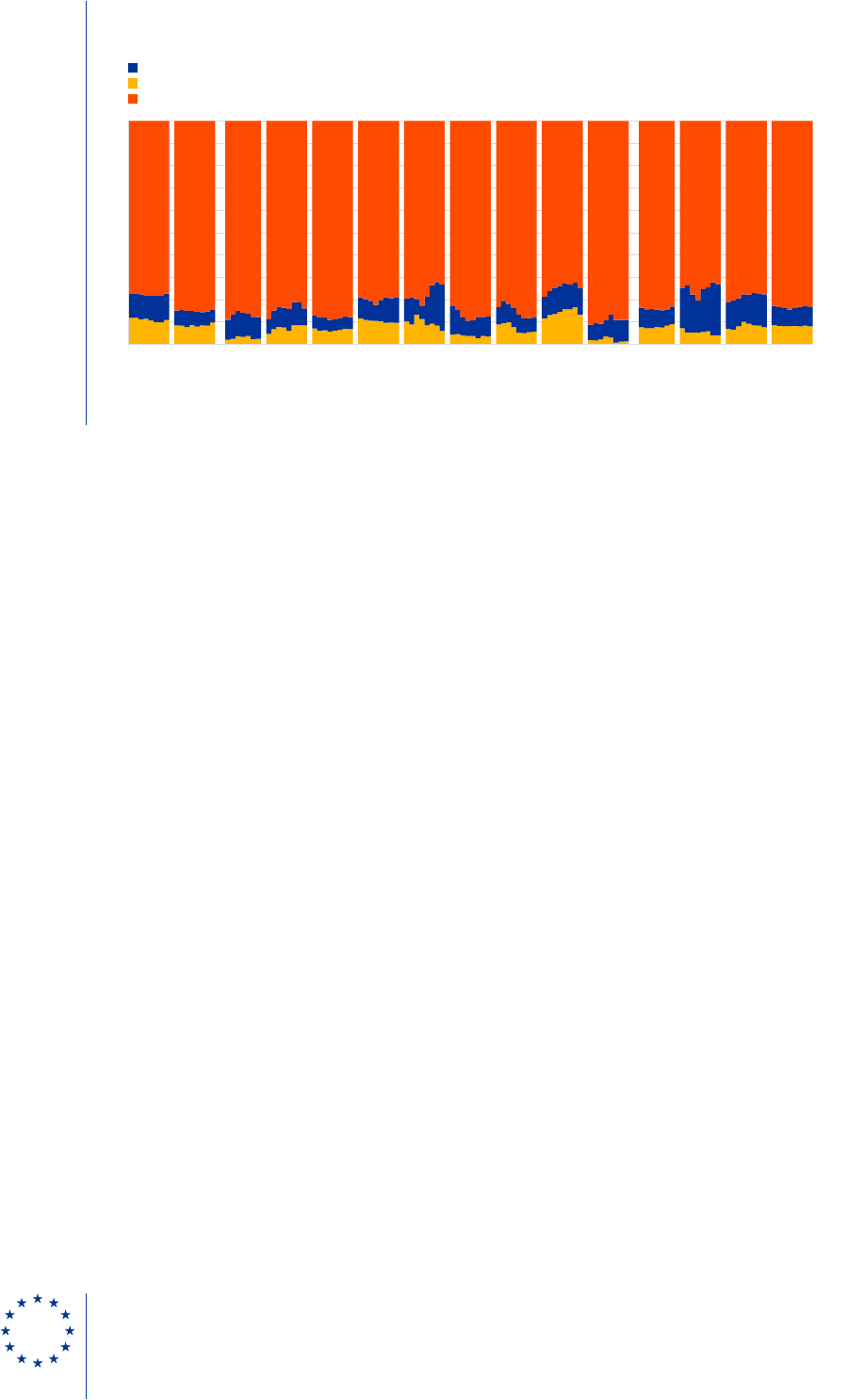

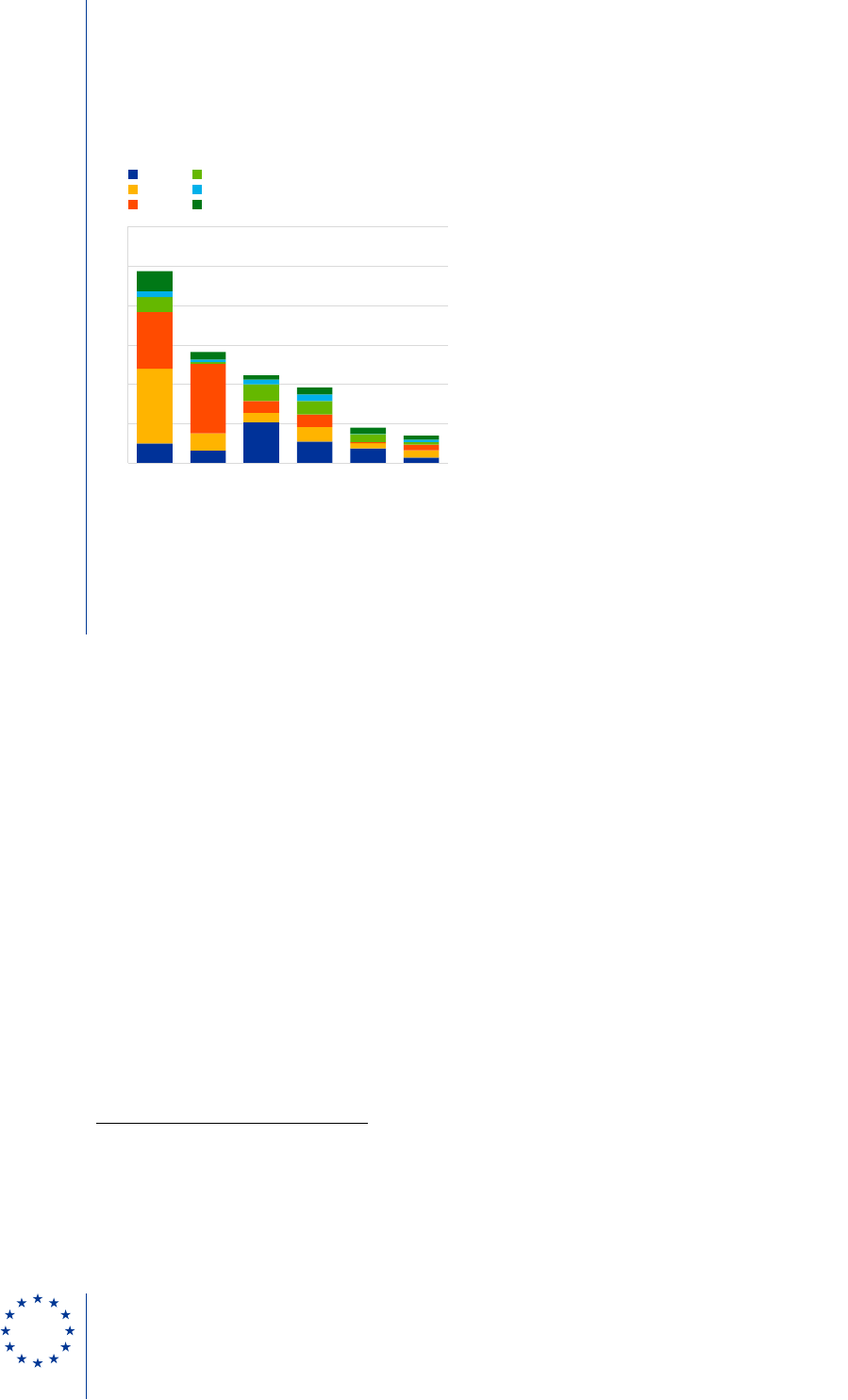

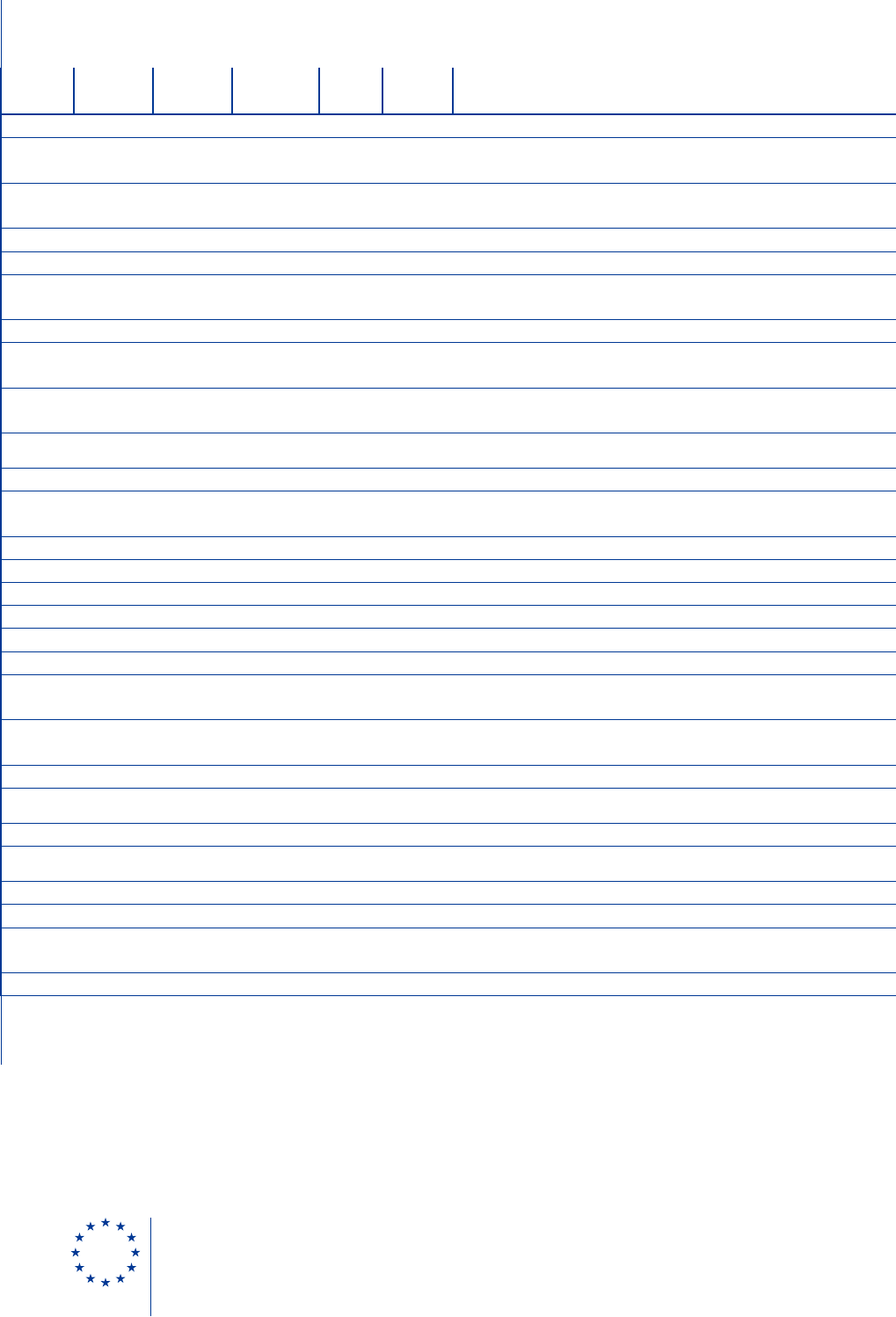

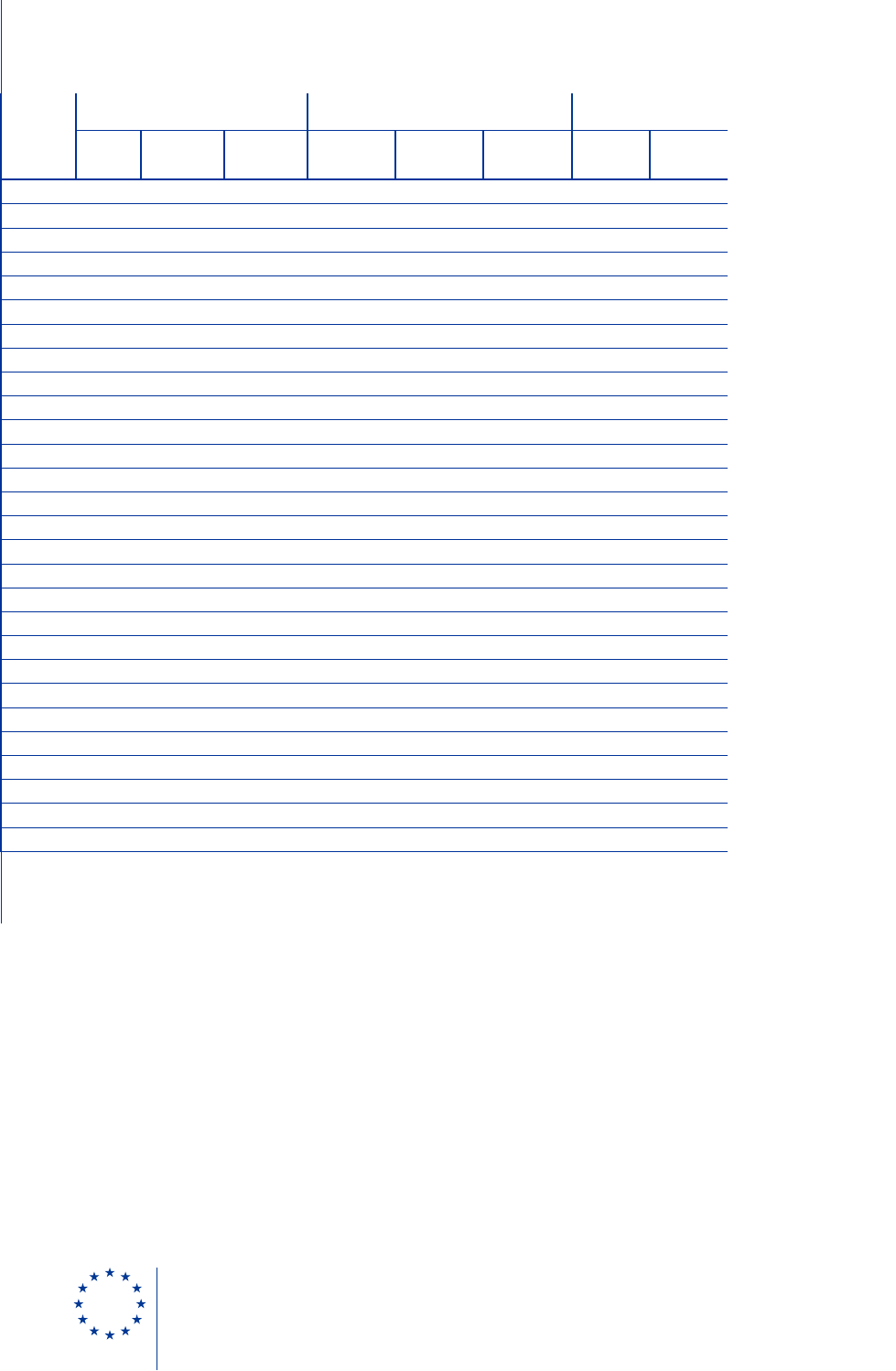

Chart 1

Number of financial conglomerates by type and domicile (2016)

Source: JC of ESAs (2016) and ESRB based on national data.

Note: Data for the UK also include four conglomerates with the head of group outside the EU/EEA.

27. A financial conglomerate may pose high risks of contagion spreading from one part of

the conglomerate to the others. Conglomerates have certain benefits, e.g. in terms of risk

diversification and the reinforcement of commercial capacity. This comes, however, with

additional costs in terms of interdependencies and, therefore, higher risks of contagion

between group entities. The intensity of the interconnections within a conglomerate depends

on what strategy the conglomerate employs to combine activities in different sectors. There

could be financial (e.g. intra-group transactions), operational (e.g. shared services) and

commercial links

16

and, moreover, there could also be reputational risks. For instance, the

failure of the insurance part of a financial conglomerate could lead to the significant

degradation of the financial position of other parts through the reputational channel. Contagion

could also spread in the other direction, e.g. the financial position of the insurance part could

deteriorate if another part were no longer able to reimburse a loan granted by the insurer or if

a breakdown of the banking agent network had materially affected the distribution model of

the insurance part. As parts of financial conglomerates, the distress or failure of the insurance

part could have a direct impact on other parts, and vice versa.

28. The degree of interconnectedness is one of the key elements in the global assessment

of systemic importance of insurers. The global financial crisis highlighted the

consequences of the close interconnectedness of the financial sector. This resulted in the

FSB placing high importance on the degree of interconnectedness in its G-SIFI framework.

15

G-SIBs refer to global systemically important banks and G-SIIs to global systemically important insurers. Both G-SIBs and

G-SIIs are designated annually by the Financial Stability Board.

16

Financial interconnectedness is related to intragroup transactions, operational interconnectedness to shared supporting

systems and services (e.g. IT), and commercial interconnectedness arises when a common distribution channel is used by

different parts of a conglomerate.

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

UK FR DE NL SE FI IT ES AT BE PT DK MT BG IE NO

insurer-led

bank-led

asset manager-led

pension fund-led

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 15

The IAIS approach weighted the interconnectedness category for insurers with almost 50%

(IAIS 2016c). The indicator covers both direct exposures via the counterparty exposure

channel and indirect exposures of insurers to the macroeconomy via the macroeconomic

exposure channel.

2.2.2 Cross-border spillovers

29. Cross-border activity of primary insurers in the EU is high. Considering both subsidiaries

and branches, the cross-border activity is more prominent in the EU primary insurance sector

than in the EU banking sector (Chart 2). For their EU cross-border business, EU insurers

operate mostly via separate legal entities in the form of subsidiaries. On average, only 3.5% of

gross premiums is written by foreign EU branches. Branches are, however, significant in some

EU Member States and their connections still form a dense and diversified network within the

EU insurance sector. As Chart 3 shows, in some cases the direction of exposures of branches

goes from small EU Member States (in terms of the size of the economy and the financial

sector) to large EU Member States. This means that even if the exposure is small for the

country in which the branch is located it could be large for the country in which the insurer is

domiciled. This argument also applies to exposures via subsidiaries.

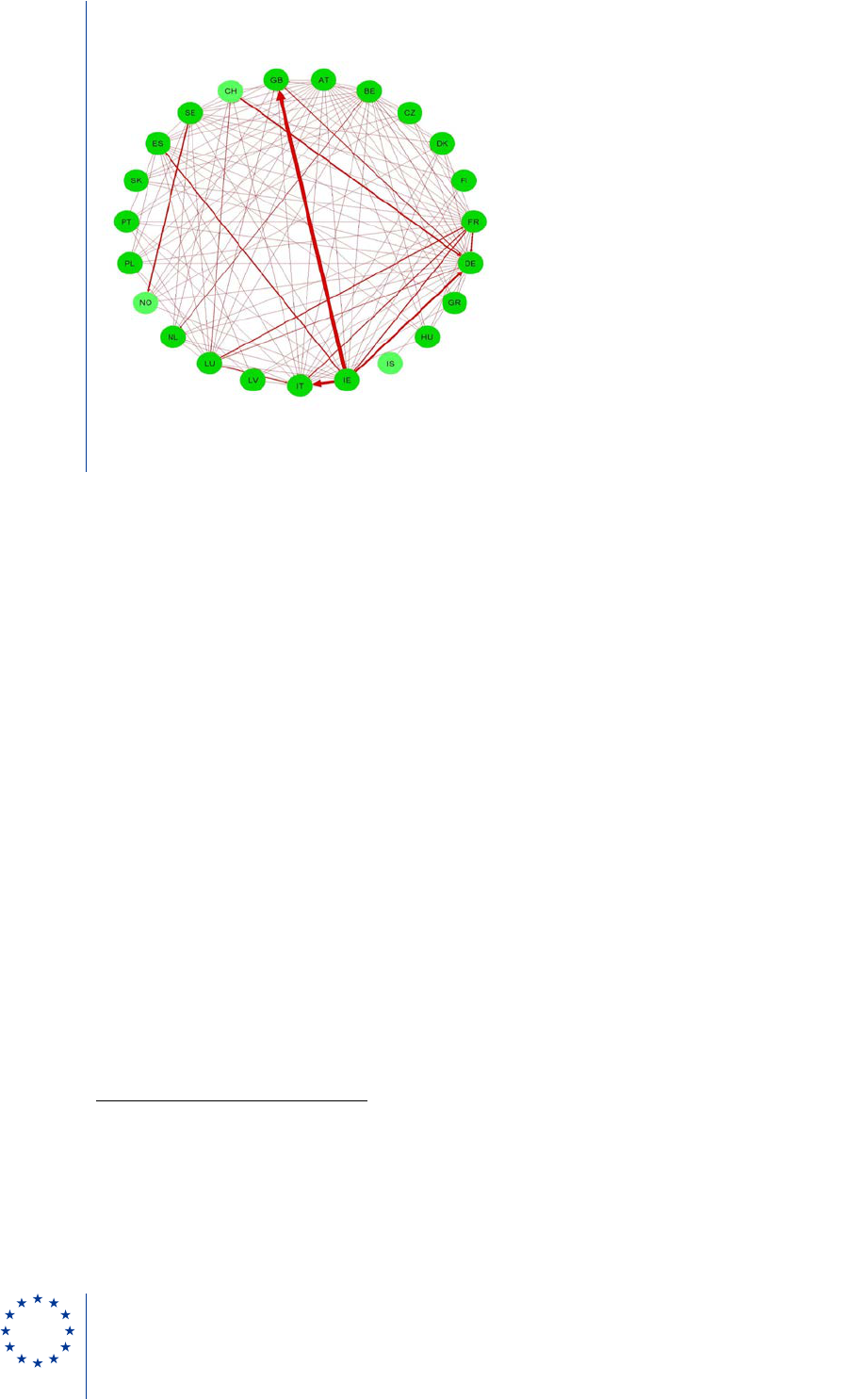

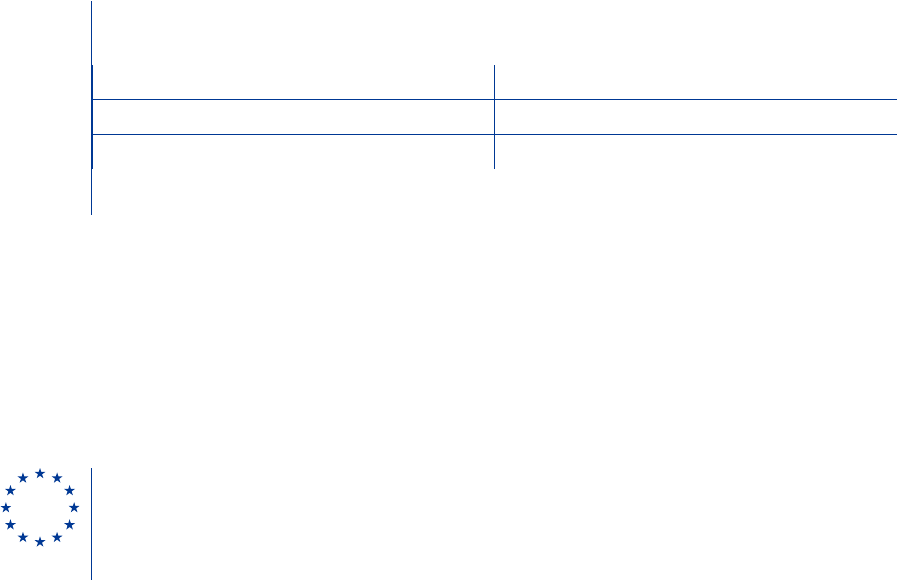

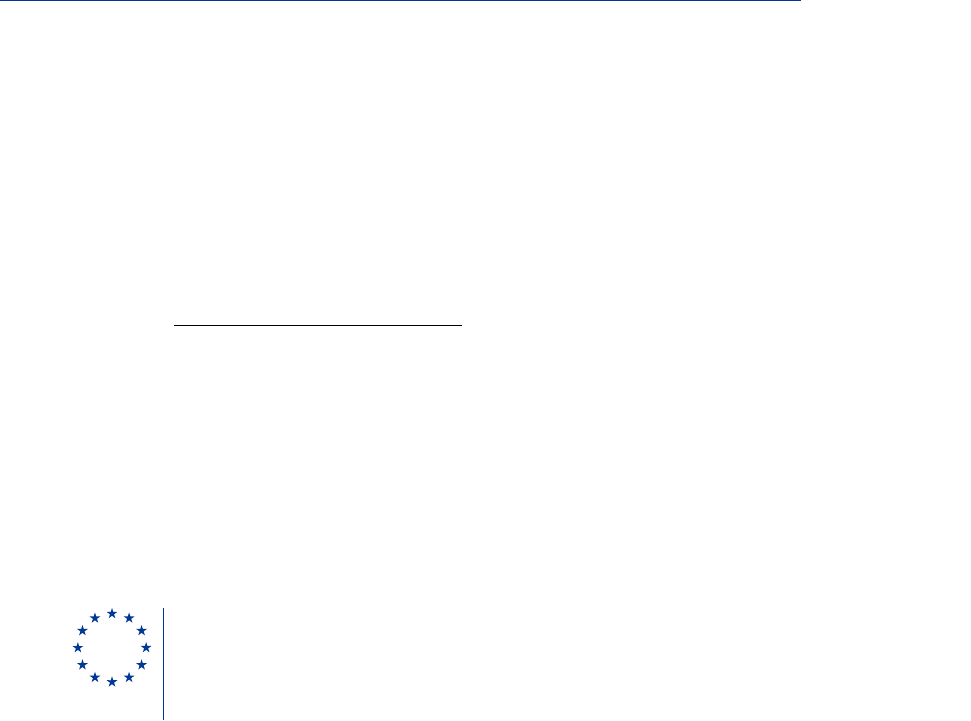

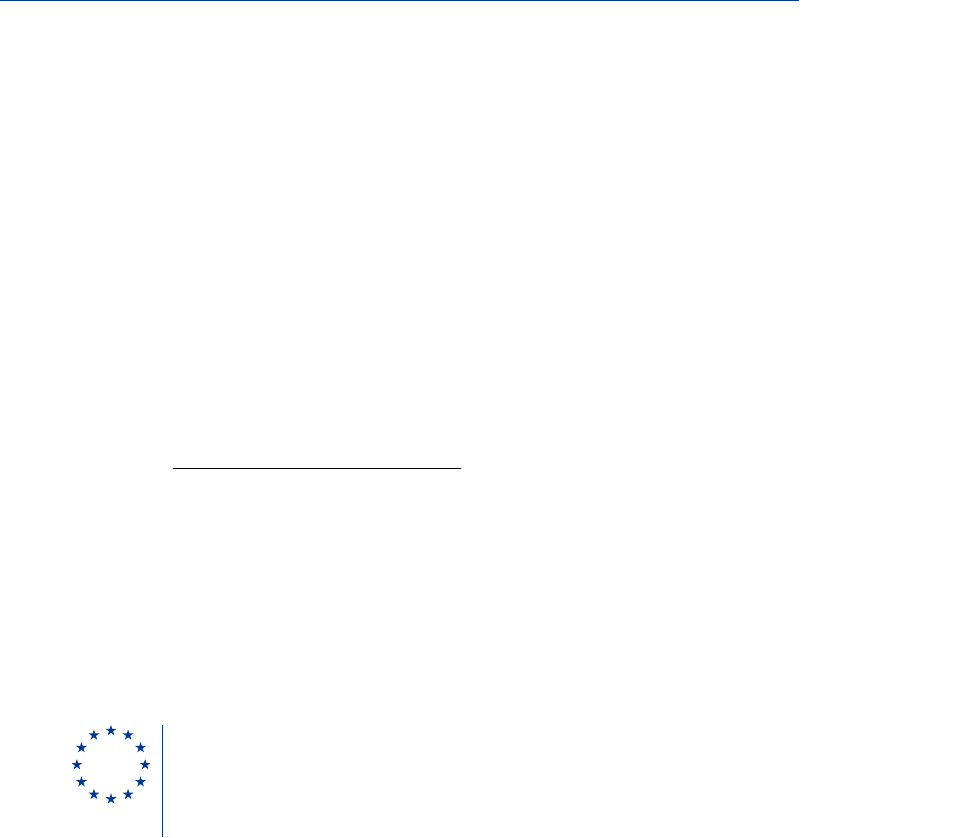

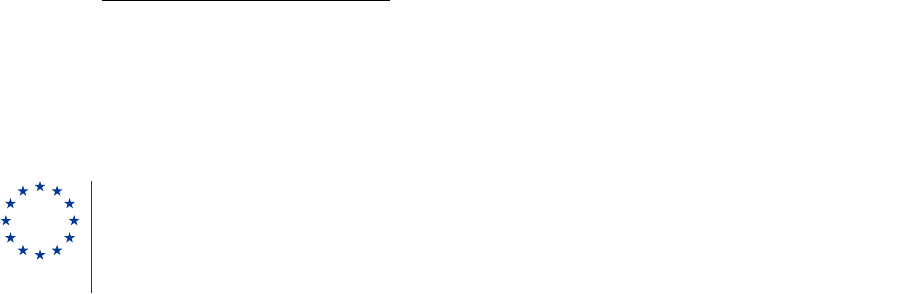

Chart 2

Cross-border activity in the banking and insurance sectors within the EU (2012, %)

Source: EIOPA (2016), based on Schoenmaker and Sass (2014).

Note: Data refer to 2012. Cross-border activity in the insurance sector is measured as the percentage of gross written premiums written by

subsidiaries and branches controlled by foreign enterprises located in the EU. For the banking sector, cross-border activity is measured as the total

amount of foreign lending (assets) as a percentage of total lending (assets). The chart illustrates the cross-border activity in the EU coming from other

EU Member States only. The EU uses a simple average across all EU Member States.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

AT BE BG CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GR HU IE IT LT LU LV MT NL PL PT RO SE SI SK UK EU

insurers - branches

insurers - subsidiaries

banks

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 16

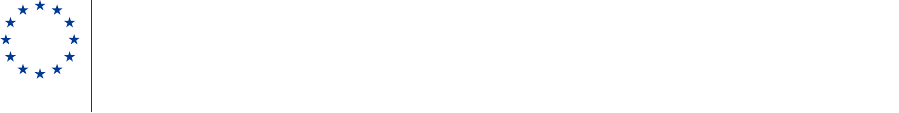

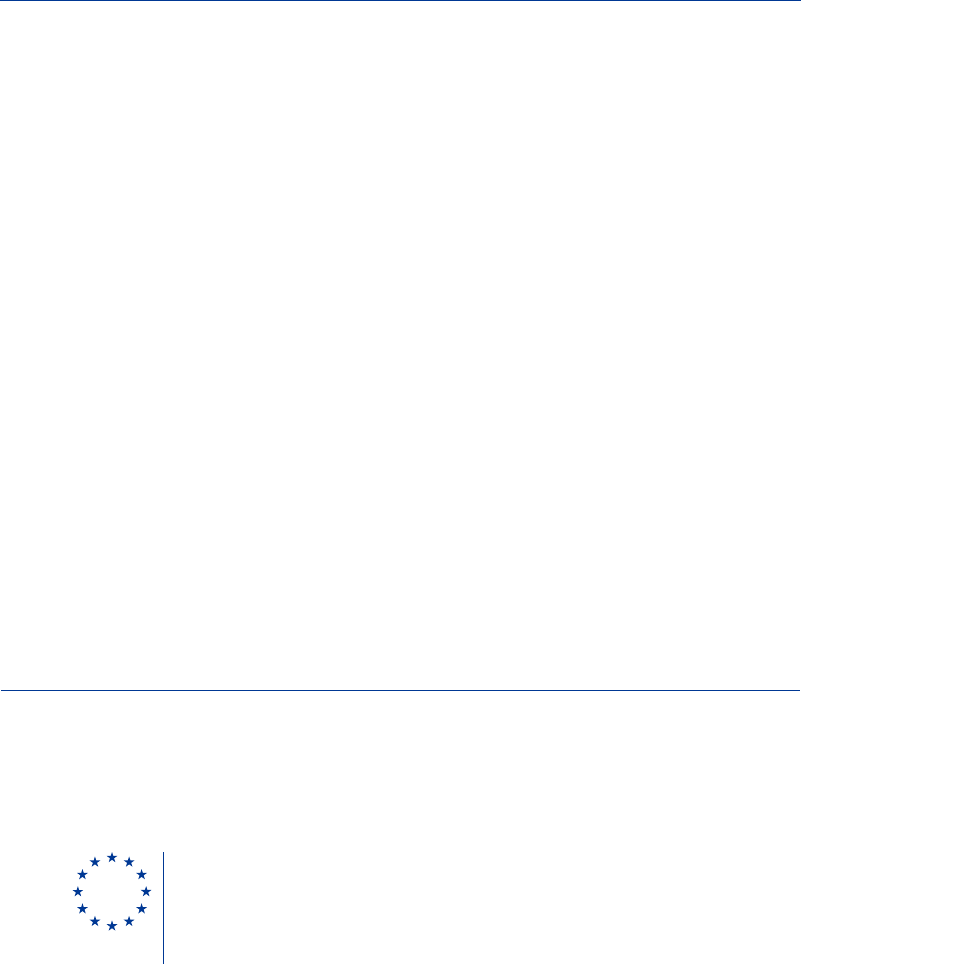

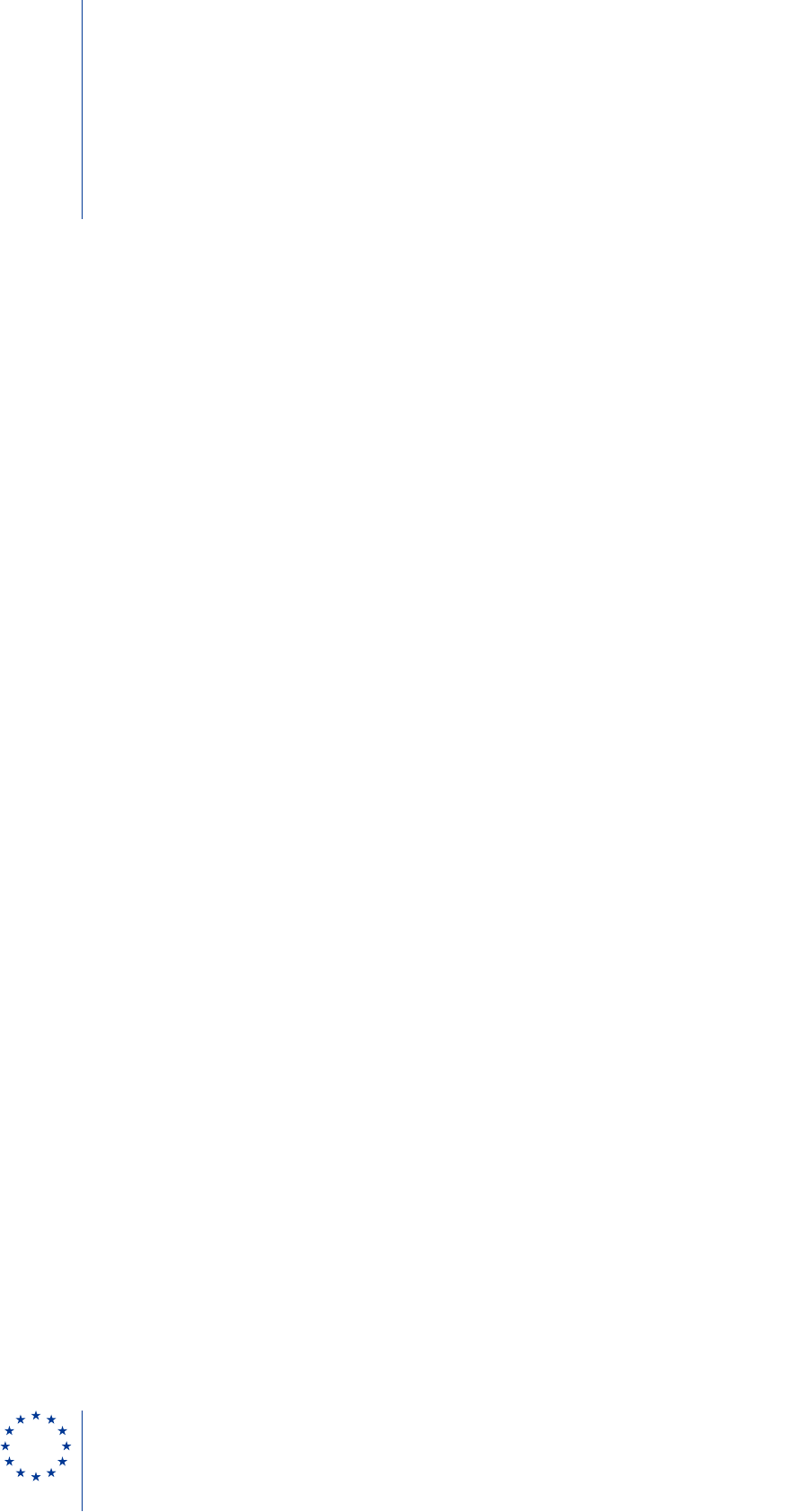

Chart 3

Network of exposures in terms of insurance branches (2014)

Source: OECD Insurance Statistics 2015. ECB Exchange Rate Statistics used for currency conversion.

Note: Data refer to 2014, and to business written abroad by EU/EEA insurers through branches and agencies. The thickness of the lines is relative to

the size of the business. Non-EU EEA countries (CH, IS, NO) are shown in light green.

30. The reinsurance sector is traditionally an international business, with EU-based

reinsurers playing an important role. The international nature of the reinsurance business

serves to diversify exposures to risk in the insurance sector. In particular, the EU-domiciled

reinsurers account for more than 45% of gross premiums written worldwide (A.M. Best

2014).

17

Moreover, in terms of the relative transfer of risks between geographic regions,

aggregated gross reinsurance premiums assumed and ceded by regions show that European

reinsurers are – in contrast to any other region – “net insurance risk takers” (IAIS 2017).

18

31. The failure of an insurer could have cross-border spillover effects. Given the high degree

of cross-border activity in the EU insurance sector, the failure of a cross-border insurance

entity in one country could impact financial stability in other countries. Similarly to financial

conglomerates, the effects relate primarily to financial (e.g. intra-group transactions),

operational (e.g. shared services), commercial and reputational links. They will differ

depending on the nature and intensity of interconnectedness within an insurance group, and

on whether cross-border insurers operate in host countries through subsidiaries or through

branches. Analogously, the failure of a reinsurer with a large international portfolio could have

repercussions in several countries due to the nature of their business associated with

retrocession and reinsurance spirals, as well as a high level of concentration in the

reinsurance market.

17

This figure increases to more than 60% if Swiss reinsurers are also included.

18

This is a persistent finding over time. See also previous reports (e.g. IAIS 2012).

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 17

2.3 Systemic risks associated with a low interest rate environment

32. The LIR environment increases the likelihood of insurers’ failures, particularly in the

life sector. The current LIR environment highlights how the systemic importance of insurers

may change over time. Globally, the outlook for many insurance companies continued to

deteriorate in 2016 as expectations of an extended period of low interest rates rose (IMF

2016) and, even though Europe has shown some economic recovery, interest rates are likely

to remain low for some time. The LIR environment is not a risk in itself, although it is a trigger

for vulnerabilities, in particular in respect of life insurance.

19

Therefore, if the LIR environment

extends into the future, it is likely to weaken the resilience of the insurance sector across the

EU. Despite the varying exposure of national insurance sectors to this risk, the impact on the

insurance sector would be noticeable in all EU Member States.

33. The 2016 EIOPA stress test showed that in a prolonged LIR environment a significant

number of EU insurers would lose a substantial part of their assets over liabilities.

20

In

a situation of secular stagnation with yields remaining low for a long period of time, insurers

would experience a highly negative impact on their excess of assets over liabilities and own

funds.

21

In particular, insurers with long-term life policies involving interest rate guarantees

could face difficulties keeping their financial promises. If rates stayed low for long, a situation

could arise where policies would continue to pay out a return that is higher than incoming

returns on assets. In such an environment, relatively high interest rate guarantees on liabilities

with a longer payout period would weigh on the profitability and solvency of these companies

over time, which could eventually lead to failures. The evidence shows that the insurance

sector is reacting to the LIR environment by shifting towards policies with lower or no

guarantees for new contracts (ESRB 2016b).

34. The likelihood of a “double-hit” scenario has also increased. If the LIR environment were

combined with a sudden increase in risk premia there would be a risk that life insurers in

several countries could simultaneously come under stress. The 2016 EIOPA stress test shows

that European insurers are highly sensitive to this scenario, which would negatively impact on

their excess of assets over liabilities and own funds.

22

However, the impact would not be

equally spread among the different insurers or national markets. Even though the failure of an

individual insurance company may not be systemically important, if it failed at the same time

as other insurers it might contribute significantly to systemic risk. Against this background, the

common vulnerability to a “double hit” from low interest rates and declining asset prices is

19

Non-life insurers are experiencing less pressure due to their shorter investment horizons and the possibility of repricing

existing contracts.

20

The exercise involved 236 insurance undertakings at solo level, from 30 European countries (EIOPA 2016c).

21

According to the 2016 EIOPA stress test results, at an aggregated level, the “low-for-long” scenario resulted in a fall in the

excess of assets over liabilities of about EUR 100 billion, with insurers representing 16% of the sample losing more than a

third of their excess of assets over liabilities. If long-term guarantees (LTG) and transitional measures were not included,

25% of the sample lost more than a third of their excess of assets over liabilities in the low-for-long scenario. No impact on

groups was considered.

22

According to the 2016 EIOPA stress test results, the so-called “double-hit” scenario (reflecting a sudden increase in risk

premia in conjunction with the low yield environment) had a negative aggregated impact on the undertakings’ balance

sheets of close to EUR 160 billion (-28.9% of the total excess of assets over liabilities) with more than 40% of the sample

losing more than a third of their excess of assets over liabilities. If LTG and transitional measures were not included, almost

75% of the sample would lose more than a third of their excess of assets over liabilities. It should be noted that the “double

hit” scenario reflects a very extreme and rare combination of events.

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 18

viewed as one of the most prominent systemic risks, possibly leading to cascading failures in

the sector (ESRB 2016a).

35. The changing nature of the insurance business exposes insurers to new types of risks

and increases their interconnection with the rest of the financial sector. For example,

the ESRB has identified that, as a result of structural changes in investments and product

offerings by life insurers, liquidity risks in the life insurance sector could become more

prominent than in the past. This is due to (i) the risk of selective redemptions by policyholders

when insurers invest in less liquid and long-term assets (e.g. infrastructure and real estate),

(ii) the transfer of investment risk to policyholders, including the broader provision of unit-

linked/defined contribution models, which are more easily surrendered at short notice, and

(iii) a move into bank-like savings products without adequate expertise and risk management

(ESRB 2016b). Moreover, with greater integration into financial markets, life insurers are more

exposed to risks stemming from other sectors, in particular through (i) higher lending to banks

and (ii) an increase in the impact of risk factors shared with the investment fund sector due to

greater product similarity following the shift to unit-linked products (ESRB 2016b).

36. A protracted LIR environment could also induce some insurers to increase investments

in risky and/or less liquid assets with a higher return, thus exposing them to a higher

probability of distress (search-for-yield behaviour). The move towards less liquid and

higher-risk assets such as stocks, infrastructure and real estate could occur, in particular, in

life insurance and long-tail non-life (casualty) insurance, although risk-oriented capital

requirements in Solvency II could mitigate this development. Although no shift of portfolios

towards riskier categories of assets has been generally observed throughout the insurance

sector, firm-level case studies suggest that smaller life insurers, in particular those with

weaker capital positions and those with higher shares of guaranteed liabilities, tend to take on

more risk (IMF 2016). This riskier behaviour could be also relevant for reinsurers, given the

high level of competition they face as other investors offer an alternative to traditional

reinsurance and drive down prices.

2.4 A recovery and resolution framework for insurers from a macroprudential

perspective

37. In this context it is worth revisiting the need to strengthen the RR toolkit at national

level and to examine the case for a harmonised RR framework in the EU. New

challenges and developments in the insurance sector mean that the existing legal and

institutional frameworks should be revisited across the EU in order to assess their sufficiency

to address systemic risks in the insurance sector in an effective manner, without creating

unnecessary distortions to other financial sectors or countries. An effective RR framework

should provide authorities with a set of early intervention tools in order to deal with, in a timely

manner, distressed insurers under a “going-concern” approach, and a set of resolution tools to

deal effectively with a failing insurer under a “gone concern” approach.

38. An effective resolution toolkit could mitigate the financial stability implications of a

failure in the insurance sector, in comparison with normal insolvency procedure. As the

experience of the recent crisis has shown, the insolvency procedure has several

shortcomings. First, it may not provide continuity of critical functions (see Box 2 on critical

functions). This could mean that the key economic transactions facilitated by insurance might

not be possible without policyholders incurring significant additional costs. Second, it might not

be able to prevent possible contagion to other parts of the financial system. This is especially

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 19

so for large insurers (e.g. the failure of AIG), but is also the case for the simultaneous failures

of small insurers. Another disadvantage of liquidation is the time required, which could result

in delays of several years in the settlement of outstanding claims, possibly undermining

society’s trust in the insurance sector as a whole and the financial system in general.

39. If they are equipped with a broad set of tools in the recovery phase, authorities might

be better able to avoid a failure. Insurance risks are typically “slow-burning”, including

longevity risks as well as risks associated with the LIR environment. This means that they lead

to failure only after a number of years if not properly addressed under the “going-concern”

approach. This period of time allows supervisory action to be taken, within the limits of legal

and institutional frameworks. It follows that expanding the toolkit for early intervention periods

provides authorities with more options to avoid an insurer needing to be wound down, which

would benefit policyholders as well as financial stability.

40. It follows that the objectives of the resolution of insurers are both financial stability and

policyholder protection, and that they are interlinked. According to the FSB, the objectives

of resolution are (without ranking): (i) to avoid severe systemic disruption; (ii) to avoid

exposing taxpayers to losses; (iii) to protect vital economic functions;

23

and (iv) to protect

policyholders (FSB 2014a). These objectives are interlinked and overlap. If vital economic

functions are impaired because of a failing insurer, systemic disruptions may arise and the

government might step in to bail out the failing insurer, exposing taxpayers to losses.

24

In the

event of a capital shortfall at a life insurer, there could be an impact on consumer confidence

in the financial sector as well as political pressure to bail out this insurer rather than let it enter

liquidation, given the nature of its liabilities (ESRB 2015).

41. Moreover, an effective RR framework requires taking a sectoral view, albeit subject to

the principle of proportionality. The challenges the insurance industry is facing indicate that

the RR framework needs to look beyond the individual firms that could pose a systemic risk on

their own. Instead, a broad perspective, where all insurers (including smaller insurers) are

subject to the RR framework, is warranted.

25

The potential solvency problems of individual

firms may lead to cascading effects that could become systemic. Although the RR framework

should, in principle, cover the whole sector, its implementation should follow the principle of

proportionality. For example, the benefits related to the application of certain pre-emptive

measures, such as RR plans, should be considered against the additional costs of their

implementation, in particular with respect to small insurers and/or insurers with less diversified

product offerings and with strong capital positions. Furthermore, national authorities should

have the flexibility to apply the RR tools that best suit local conditions and should also have

the power to exempt some insurers from certain aspects of the RR framework, e.g. RR plans,

without preventing authorities from applying all the powers at their disposal should the need

arise. The principle of proportionality as explained above applies across the whole report.

42. Strengthening existing RR frameworks for insurers across the EU could limit systemic

risks following distress or failure. Strengthening the current RR framework at national level

could help mitigate financial stability concerns in the ways below.

23

The terms “vital economic functions” and “critical functions” are used interchangeably by the FSB (e.g. FSB 2014a).

24

The EU state aid rules must be complied with before a state bailout is approved by the European Commission.

25

As indicated by the IMF, firm-level case studies suggest that the behaviour of smaller and weaker insurers warrants the

attention of supervisors (IMF 2016a), since they tend to take on relatively more risk.

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 20

• Critical functions could be identified in RR planning and could be better protected in

resolution.

• Strengthening frameworks could encourage better preparation for crises and the early

implementation of preventive actions. For example, measures such as RR planning and

resolvability assessments could reveal potential contagion channels.

• A strengthened set of early intervention tools may help to avoid an insurer’s failure,

allowing national competent authorities to address a potential issue with the right tool,

which would benefit policyholders as well as financial stability. Moreover, an enhanced

set of resolution tools could help to avoid a liquidation in which it might not be possible to

preserve critical functions, and which could also lead to a potential destruction of value.

• The exchange of confidential information in times of crisis and the requirements of

coordination between the relevant authorities within the country during the resolution

process would be defined and governed by a strengthened legal framework.

43. Increased harmonisation in Europe could limit systemic risks of cross-border

contagion. Strengthening national frameworks might not be sufficient, given that insurance is

an international business, with large cross-border insurers operating in several EU Member

States. At the same time, the fact that a failing insurer would typically not need to be resolved

as quickly as a failing bank, offers some room for national discretion. While it is recognised

that the harmonised framework could provide a certain flexibility to address the national

specificities of local insurance sectors, some degree of harmonisation across the EU may help

to mitigate systemic risks and create a level playing field in the ways described below.

• A harmonised EU-wide RR framework would enable better evaluation of the implications

for other jurisdictions of any national measure taken. This would mean that the protection

of critical functions in one country would not adversely affect the critical functions in

another country.

• Harmonised RR plans would make it easier for authorities to compare measures planned

for distressed insurers across the EU and enable them to better analyse and mitigate

any spillovers to other sectors or across borders.

• A common set of rules is particularly relevant in the event of the distress of a large

international insurer conducting significant business in several EU Member States or in

the event of the simultaneous distress of several unrelated insurers in several EU

Member States.

• A strengthened legal framework applicable EU-wide would increase coordination and

cooperation mechanisms, including information sharing, across borders. Enhanced

cross-border coordination could prevent cross-border spillovers. Although coordination

arrangements for supervisory colleges, including emergency planning, are currently in

place,

26

appointed administrators or liquidators at national level or national resolution

26

See Annex 1.E of EIOPA Guidelines on the operational functioning of colleges (EIOPA 2014b).

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 21

authorities for insurers are not required to coordinate their resolution planning and

actions across jurisdictions.

27

• Investors and customers would be treated more similarly in all countries, which could

contribute to a higher level of financial integration. This could increase trust in the

insurance sector and in the EU internal market.

44. This report recognises that a few ESRB members might hold a different view on some

aspects of RR frameworks for insurers. It is broadly recognised that RR frameworks for

insurers need to be strengthened across the ESRB membership. Moreover, several

authorities initiated or are considering measures to strengthen their national frameworks,

either due to recent experience or to the fact that low systemic risk of insurers in the past does

not guarantee the absence of systemic risk in the future (IAIS 2015). However, a few ESRB

member institutions take the view that it might not be cost effective to introduce an ambitious

RR framework for insurers. This reflects sparse evidence to date that traditional lines of

business of insurance have generated or amplified systemic risk within the financial system or

in the real economy and, that existing national frameworks have functioned properly so far.

Moreover, they are of the view that national frameworks could be reinforced without the

introduction of a comprehensive single EU-wide RR framework. Furthermore, since most

failures of EU insurers have not impaired the EU financial system to any great extent, and

given concerns over potential conflict between policyholder protection and financial stability,

some authorities prefer to place higher importance on the policyholder protection objective

than the financial stability objective in the RR framework for insurers, while recognising the

importance of both (ESRB 2017).

Box 2

Critical functions in the insurance sector

The concept of critical functions has been developed by the FSB as part of its RR

framework. Critical functions are “essential and systemically important functions” (FSB 2013) or

“vital economic functions” (FSB 2014a), for which continuity should be maintained in the resolution

process while avoiding unnecessary destruction of value.

28

Where such functions have been

identified resolution tools other than regular liquidation proceedings should be considered. The

reason for this is that safeguarding critical functions is not an objective of the regular liquidation

proceedings; the liquidation process could, instead, lead to the destruction of their value. Moreover,

a regular liquidation process could also include the possible disruption of payments to policyholders

or other financial institutions (FSB 2016).

The FSB considers criticality in the context of the impact of a failure on the financial system

and the possible substitutability of the failed insurer. According to the FSB, the provision of

27

Title IV of the Solvency II Directive (“Reorganisation and winding-up of insurance undertakings”) provides regulation in this

area in the EU. The regulation largely refers to the right of the competent authorities of the home EU Member State to take

action in line with national legislation, while keeping the supervisory authorities of other EU Member States informed of the

decisions. It should be noted, however, that cross-border cooperation in the form of crisis management groups and

cooperation agreements are foreseen, and partially implemented, in the EU as a result of global standards for G-SIIs;

although these would not necessarily apply to a population broader than the five EU GSIIs.

28

Critical functions, systemically important functions, essential functions and vital economic functions are used

interchangeably.

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 22

insurance includes three key functions carried out by insurers which may be viewed as critical:

(i) writing new business; (ii) providing insurance cover for existing business; and (iii) making

payments to policyholders (FSB 2016b). Insurers also provide important non-insurance functions to

third parties, such as asset management. The criticality of all functions provided by insurers varies

across insurance products, insurers and jurisdictions. The FSB defines a function of an insurer as

critical if it satisfies all of the following conditions: (i) it is provided by an insurer to third parties not

affiliated to the firm; (ii) the sudden failure to provide that function would probably have a material

impact on the financial system and/or the real economy as it would give rise to systemic disruption

or undermine general confidence in the provision of insurance; and (iii) it cannot be substituted

within a reasonable period of time and at a reasonable cost (FSB 2016b).

The identification of critical functions is dependent on time and context. The impact of an

insurance failure could vary, depending on the conditions in the financial system and the economy

at the time of the failure. It is, therefore, difficult to identify all critical functions prior to a resolution.

For example, during the distress of an insurer it might not be possible to find a substitute insurer

within a reasonable period of time and at a reasonable cost. As a result of this, certain types of

insurance might become critical if a lack of substitutability of an insurer within a reasonable period

of time is likely to have a significant impact on the financial system and/or the real economy.

Similarly, if a reinsurer fails, primary insurers could face a situation where – for a considerable

period of time – they are not able to buy reinsurance for certain risks at a reasonable cost and, as a

result, they might stop underwriting these risks. The lack of substitutability might therefore justify

resolution measures aimed at recapitalising the insurer so it can continue to be able to write new

business, or resolution measures aimed at providing continuity in order to facilitate substitutability

over time. Furthermore, the FSB also recognises that the identification of critical functions involves

making a broader political and economic judgement, e.g. it might be necessary to preserve the

continuity of functions that are material to the real economy, e.g. in the event of disruption of cover

or payments to a significant number of policyholders, in particular in the life business (FSB 2016b).

It may be appropriate to consider critical functions from a broader perspective. Some

elements of the previous definition have not proved very helpful in identifying critical functions in the

insurance sector. It should be noted, especially in the current environment of low yields, that the

failure of an insurer does not occur suddenly, but gradually. Slow-burning distress can materially

impact the financial system and the real economy, undermining confidence. This type of failure

should therefore be taken into account in the RR framework. Furthermore, there may be other

important functions which may be worth examining in the context of insurance resolution, including

pension fund management and asset management. Lastly, it might be of interest to safeguard the

viable parts of an insurer.

Furthermore, the industry-wide definition of critical functions might prove more relevant in

the LIR environment. The FSB focuses on criticality stemming from the failure of a single entity.

As pointed out by the IMF, such an approach covers “domino” systemic effects, where the failure of

a single entity has systemic consequences for the broader economy (IMF 2016). Another

contribution to systemic risk is, however, through common exposures across firms that may

endanger financial intermediation in the system as a whole in the event of an adverse shock,

referred to as “tsunami” systemic effects. In the LIR environment, which raises the possibility of an

extreme severe double-hit scenario, no individual failing insurer might have a significant impact on

financial stability on its own, but if several insurers were to fail simultaneously they might

collectively produce a material systemic effect.

For the purpose of this report, a broader perspective is taken in respect of criticality, and the

report advocates further discussion of critical functions in the insurance sector. Within the

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

Systemic risks and the case for an effective recovery and resolution framework for insurers 23

spirit of the FSB statement that criticality is not a binary concept and that there is a spectrum of

criticality (FSB 2013), the report goes beyond a narrow interpretation of the FSB definition of critical

functions in the insurance sector. A critical function, in the context of this report, is understood as

any function of an insurer or a group of insurers, which (if not provided) might have a significant

impact on the financial system or the real economy. On the back of these considerations, it is

recognised that the definition and the scope of critical functions merit further discussion, both at

European and global level, i.e. when a harmonised EU-wide RR framework is being developed, in

order to adequately cover all critical functions worth preserving, from both an individual-firm and an

industry perspective.

ESRB

Recovery and resolution for the EU insurance sector: a macroprudential perspective August 2017

International and European initiatives on recovery and resolution for insurers 24

3.1 Introduction

45. This section provides an overview of recent initiatives in both a global and a European

context. It describes the work of the IAIS and the FSB, with a special focus on the approach

to G-SIIs. It shows how some of the ideas developed for G-SIIs are being integrated into the

IAIS Insurance Core Principles (ICPs) for all insurers. Moreover, the section describes the

initiatives at European level, in particular by the COM and EIOPA. It would appear that, in the

absence of a harmonised approach, several national initiatives aimed at reinforcing national

RR frameworks are increasingly under consideration.

3.2 Global initiatives

46. At a global level, the IAIS and the FSB are the main driving forces establishing the

principles of recovery and resolution (RR) in the insurance sector. The IAIS is the global