February 2018

SDN/18/02

I M F S T A F F D I S C

U S S I O N N O T

E

Trade-offs in Bank Resolution

Giovanni Dell’Ariccia, Maria Soledad Martinez Peria,

Deniz Igan, Elsie Addo Awadzi, Marc Dobler, and

Damiano Sandri

DISCLAIMER: Staff Discussion Notes (SDNs) showcase policy-related analysis and research being

developed by IMF staff members and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The

views expressed in Staff Discussion Notes are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the

views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

TRADE-OFFS IN BANK RESOLUTION

2 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Trade-offs in Bank Resolution

Prepared by Giovanni Dell’Ariccia, Maria Soledad Martinez Peria, Deniz Igan,

Elsie Addo Awadzi, Marc Dobler, and Damiano Sandri

†

Authorized for distribution by Maurice Obstfeld, Tobias Adrian, and Ross Leckow

February 2018

DISCLAIMER: Staff Discussion Notes (SDNs) showcase policy-related analysis and research

being developed by IMF staff members and are published to elicit comments and to encourage

debate. The views expressed in Staff Discussion Notes are those of the author(s) and do not

necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

JEL Classification Numbers: G21, G28, H81, K20

Keywords: Bank resolution, Spillovers, Financial regulation

Authors’ E-mail Addresses:

mmartinezperia@imf.org; dsandri@imf.org;

eaddoawadzi@imf.org; mdobler@imf.org

†

The authors are grateful to John Bluedorn, Enrica Detragiache, Rishi Goyal, Anna Ilyina, Marina Moretti, Alvaro Piris

Chavarri, Mahmood Pradhan, Miguel Savastano, and Miguel Segoviano for valuable comments and discussions. Nicola

Babarcich and Antoine Malfroy-Camine provided outstanding research support and Gabriela Maciel invaluable

administrative support.

TRADE-OFFS IN BANK RESOLUTION

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 3

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ________________________________________________________________________ 4

INTRODUCTION _______________________________________________________________________________ 5

I. KEY INSIGHTS FROM A SIMPLE MODEL __________________________________________________ 7

II. EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE ____________________________________________________________________ 11

III. RESOLUTION FRAMEWORKS IN PRACTICE ______________________________________________ 24

IV. CONCLUSION _____________________________________________________________________________ 26

Figures

1. Optimal Resolution Framework as a Function of Spillover Intensity __________________________ 9

2. Bank Size and Reaction to Events Altering Bail-out Expectations ____________________________ 14

3. Holdings of Bank Equity, Contingent Capital, and Bail-in-able Debt_________________________ 23

Tables

1. Market Reaction to Bail-out Events _________________________________________________________ 13

2. Borrowing Costs and Risk Metrics for Large versus Small Banks ____________________________ 15

3. Size and Risk Taking ________________________________________________________________________ 16

4. Market Reaction to EU Bail-in Events ________________________________________________________ 18

5. Market Reaction to US Bail-in Events________________________________________________________ 19

6. Reducing the Cost of Resolutions ___________________________________________________________ 25

Boxes

1. Fiscal Implications of Bail-outs ______________________________________________________________ 28

2. What Is Bail-in? _____________________________________________________________________________ 29

3. Resolution Regimes in Key Large Home Jurisdictions _______________________________________ 30

4. Making Bail-in a Credible Policy Option for Systemic Banks _________________________________ 31

5. Good International Practice in Public Solvency Support _____________________________________ 32

Appendix I. A Simple Model of Bail-ins and Bail-outs __________________________________________ 33

Appendix II. Sample Coverage and Empirical Specifications ___________________________________ 35

Appendix Table 1. Bail-in Events in Europe ____________________________________________________ 38

Appendix Table 2. Bail-in Events in the United States __________________________________________ 39

References _____________________________________________________________________________________ 40

TRADE-OFFS IN BANK RESOLUTION

4 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

During the global financial crisis, national authorities faced a steep policy trade-off in dealing with

systemic bank failures. On the one hand, they knew bail-outs would reinforce expectations of future

public support for distressed financial institutions. This could then undermine market discipline and

lead to excessive risk taking—potentially seeding the ground for the next crisis. On the other hand,

partly due to the absence of legal powers to resolve systemic failures through bail-ins, the use of

public resources seemed necessary to prevent distress in one bank from spreading to others and

becoming system-wide and to contain the economic and social costs of the crisis. Thus, in most cases,

failing banks were bailed out. Most of the costs and risks were borne by taxpayers, sometimes to such

a degree that the financial standing of the sovereign was threatened.

Since then, reforms have aimed to reduce the likelihood of crises and minimize costs should a crisis

occur, including by shifting the burden to private investors and improving the trade-off between bail-

outs and bail-ins. First, given the fiscal and moral hazard risks associated with government-funded

resolution, the consensus is that bail-outs need to be the exception rather than the rule. With this

objective in mind, reforms have aimed at formally delimiting the role of fiscal resources in the context

of crisis resolution. Several countries have imposed strict conditions on the use of public funds in

support of ailing banks and have introduced measures aimed at minimizing moral hazard. Second,

new frameworks provide comprehensive powers to resolve a financial institution, including by bailing

in private stakeholders (equity holders and unsecured and uninsured creditors). These include

statutory bail-in powers, which enable resolution authorities to terminate or write down unsecured

liabilities of failing banks and to convert claims of unsecured creditors into equity. The reforms have

also sought to contain potential financial stability risks stemming from bail-ins by ensuring that banks

(especially, large and complex ones) are subject to adequate loss-absorbing capacity requirements,

and have aimed to make these banks more resolvable via effective resolution planning.

This note revisits the trade-off entailed in a policymaker’s decision on the relative role of bail-ins of

private stakeholders and public bail-outs. It does this by presenting an illustrative welfare-based and

micro-founded model that juxtaposes the spillover effects from bail-ins and the moral hazard

consequences of bail-outs. It also provides empirical evidence consistent with the existence of moral

hazard effects associated with bail-outs and of spillovers associated with bail-ins. Finally, it discusses

progress in shifting the burden of a crisis to private investors, strengthening resolution frameworks,

and improving the bail-in/out trade-offs by enhancing resolvability and increasing loss absorbency.

The note supports the ongoing reform agenda to provide resolution authorities with effective bail-in

powers and stresses that frameworks should aim at minimizing moral hazard associated with bail-

outs. Nonetheless, it also emphasizes the need to allow for sufficient, albeit constrained, flexibility to

be able to use public resources in the context of systemic banking crises—when spillovers are

significant and deemed likely to severely jeopardize financial stability. Furthermore, the analysis calls

for continued efforts to enhance loss-absorbing capacity, ensure that holders of bail-in-able debt are

those best situated to absorb losses, and improve arrangements for cross-border resolution. This is

essential to further boost the effectiveness of bail-in powers and contain the risk of spillovers.

INTRODUCTION

During the global financial crisis, governments in the United States and Europe resorted extensively

to public bail-outs to prevent bank failures from destabilizing the financial sector and the economy.

This strategy fueled strong public resentment against using scarce fiscal resources to rescue banks,

especially given the fiscal consolidation efforts that followed. Furthermore, the use of bail-outs

reignited the well-known debate about their moral hazard impact on the behavior of financial

institutions. The perception that there would be few consequences for those responsible for the

banks’ losses reinforced this concern and public frustration about the handling of the crisis.

The academic literature and policy debate have long recognized that bail-outs entail a policy trade-

off between ex ante and ex post efficiency. On the one hand, expectations of public financial

support for distressed financial institutions may undermine market discipline and lead to excessive

risk taking—essentially seeding financial vulnerabilities that may precipitate a crisis. Expectations

of a bail-out may also trigger a leverage cycle, where lending standards are relaxed and leverage

becomes too high in boom times and too low in crisis times (Geanakoplos 2010). On the other

hand, in a crisis, the use of public resources to support the financial sector may sometimes be

necessary to contain the effects of system-wide financial distress.

A key question for policymakers

is how to balance these two effects—where to position the system along the trade-off (how much

to bail in and how much to bail out)—and how to improve the trade-off itself.

Against this backdrop, recent regulatory reforms and international standards on resolution have

placed significant emphasis on reducing the need for and mitigating the risk of future bail-outs,

including by improving the viability of bail-ins. Put differently, bail-outs need to become the

exception rather than the rule. To this end, a new international standard—the Financial Stability

Board’s Key Attributes (KA) of Effective Resolution Regimes, issued in 2011—advocates for

stronger resolution powers, available at early stages of distress, combined with better planning,

resolvability assessments, and cross-border cooperation. The KA aim to make systemic financial

institutions resolvable “without severe systemic disruption and without exposing taxpayers to loss.

. .” while making “it possible for shareholders and unsecured and uninsured creditors to absorb

losses.” Bail-in powers, which enable resolution authorities to recapitalize financial firms by

reducing the nominal value (that is, a “haircut”) of bank liabilities or converting them into equity,

are a key feature of the KA.

Resolution regimes that can allocate losses effectively among bank stakeholders through bail-ins

are beneficial for several reasons. First, stakeholders that could be exposed to loss in the event of

failure are likely to impose greater discipline on managers, thus reducing leverage and excessive

risk taking. This should in turn reduce the likelihood that banks fail. Second, by recognizing the

potential for loss and by calling for adequate loss-absorbing capacity, these frameworks may

reduce the risk of systemic spillovers. Third, by clarifying ex ante how losses would accrue to private

creditors in resolution, these frameworks may help address cross-border burden-sharing issues.

Not least, they reduce the direct fiscal cost of the crisis and may weaken the feedback effects

between sovereign and bank vulnerabilities (the “sovereign-bank nexus”).

TRADE-OFFS IN BANK RESOLUTION

6 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Reform efforts since the crisis have improved the trade-off between bail-ins and bail-outs by

seeking to make bail-ins a credible option and bail-outs less likely. In some countries (especially in

Europe), the default approach to handling distressed banks before the crisis was bail-outs, and this

had fiscal and moral hazard costs. The reforms aimed to change this faulty approach and establish

frameworks that allow for orderly bail-ins, while maintaining some flexibility to provide public

funding to preserve financial stability and contain the macroeconomic consequences of a systemic

crisis. Yet some fear that resolution reforms may have gone too far and overly restrict a

government’s ability to use fiscal resources when necessary (see, for instance, Geithner 2014). For

example, a bail-in could create expectations for further bail-ins in other banks. This could

undermine investor confidence even in healthy banks. Spillovers could also arise if those

experiencing losses are forced to rebalance their portfolio and sell their claims on the initially

nondistressed banks, threatening the stability of these other banks. The key feature of these

spillovers is that they involve externalities that may not be fully priced by banks and private

investors and therefore provide a rationale for policy intervention.

In this note, we examine the economic forces that determine the relative costs and benefits of bail-

ins and bail-outs. We use the term “bail-in” in a generic sense, as the ability of resolution authorities

to impose losses on private stakeholders in order to recapitalize a failing bank. Bail-in-able claims

comprise equity and unsecured and uninsured liabilities with certain features. We use “bail-out” to

refer to the ability of governments to provide public funds to restore the solvency of banks. We

consider a model that provides a framework to assess under what circumstances losses may need

to be borne by the public sector rather than private investors. The answer crucially hinges on the

trade-off between the moral hazard costs associated with bail-outs and the potential spillovers

arising from bail-ins. We then examine the pre-reform trade-off by presenting empirical evidence

on these costs and spillovers. By reviewing the literature and performing some new analysis, we

confirm that the expectation of bail-outs lowers funding costs and, in some instances, generates

greater risk taking. We assess the extent of spillovers by looking at pre-reform events during which

bank stakeholders suffered losses and find evidence consistent with financial spillovers, though we

recognize that the evidence lends itself to alternative interpretations. Finally, we discuss the

progress made under the reformed frameworks to improve the bail-in/out trade-offs.

The key takeaways from the note are as follows:

• Recent regulatory reforms have improved the trade-off between bail-ins and bail-outs.

Effective resolution frameworks (as contemplated by the KA) are likely to reduce the potential

spillovers from bail-ins. Better-defined constraints on the use of public funds have likely

reduced the expectation of future bail-outs and the associated potential for moral hazard.

Greater loss-absorbing capacity has reduced the probability of financial distress.

• Bail-outs should be the exception not the rule—their use justified as a last resort, exclusively

when financial stability is gravely threatened, and structured to mitigate the associated costs.

They should occur only alongside loss sharing with private stakeholders of the troubled bank

and time-bound restructuring plans that address the underlying weaknesses and help restore

the bank’s long-term viability.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 7

• Yet the framework should allow for the use of some public funds, with appropriate safeguards,

during systemic crises if and when this is necessary to protect financial stability. Public funds

may be needed if imposing extensive losses on private stakeholders would unleash large

spillovers. In these exceptional cases, the moral hazard and fiscal costs of bail-outs would be

preferable to the disruptive effects that spillovers associated with bail-ins could have on

financial stability and the economy at large.

• To further reduce the recourse to bail-outs, policymakers should continue ongoing efforts to

enhance resolvability and minimize the risk that bail-ins may result in large spillovers. Further

clarifying which financial instruments can be subject to bail-in and increasing the loss-

absorbing capacity of major financial institutions is key. Regulation should ensure that holders

of loss-absorbing capacity in banks are those most capable of understanding and absorbing

losses with a low risk of transmitting further shocks to the financial system and the economy.

Furthermore, more progress is needed to improve cross-border resolution aspects.

The rest of this note is structured as follows. Section I presents the theoretical model. Section II

discusses the empirical evidence. Section III provides a brief discussion of the recent reforms to

enhance resolution frameworks. Section IV concludes.

I. KEY INSIGHTS FROM A SIMPLE MODEL

To gain clear insights into the optimal use of bail-ins and bail-outs, we develop a simple banking

model that builds on Sandri 2015 and Cordella, Dell’Ariccia, and Marquez 2016. This section

provides an overview of the model and presents its key implications; we refer the reader to

Appendix I for the formal details.

The model features a continuum of banks that are heterogeneous in size. Banks raise deposits and

issue debt to finance loans. Loan repayments are subject to both idiosyncratic and aggregate

shocks. Banks can increase the likelihood that loans are repaid by exercising a costly monitoring

effort that can be interpreted as an inverse measure of risk taking. They choose the level of

monitoring to maximize expected profits. Thanks to limited liability, banks are not responsible for

losses beyond their capital buffer. Losses exceeding capital are covered with a bail-in of private

creditors, a public bail-out, or a combination of the two.

1

The key feature of the model is that bail-ins may entail systemic spillovers; that is, they may impose

negative externalities on society at large in addition to the losses borne by the bank’s stakeholders.

These externalities are modeled in reduced form, possibly proportional to the total size of bail-ins

in the banking sector. They can involve bankruptcy costs, heightened macro-financial uncertainty,

and a deterioration of the economic outlook. In practice, spillovers can spread through several

channels. They can operate mechanically through balance sheet transmission, whereby a bail-in

can jeopardize the solvency of exposed stakeholders and trigger bankruptcy chains. Or a bail-in

1

The combination or mix of bail-ins and bail-outs can be interpreted as corresponding in practice to burden

sharing, where part of the losses is borne by private stakeholders and the remaining part is assumed by the

government and, ultimately, taxpayers.

TRADE-OFFS IN BANK RESOLUTION

8 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

can act as a wake-up call and lead to a sudden reassessment of bank risk. This can in turn

undermine banks’ market access and have negative repercussions for credit supply and GDP. The

strength of spillovers varies across time and depends on broader economic and financial

conditions, including the amount and structure of loss-absorbing capacity. For example, bail-in of

a midsize bank may entail no spillovers if it happens during an economic upswing, but may become

destabilizing if it occurs at a time of severe distress in the banking sector. The strength of spillovers

may also vary across countries, reflecting different macro-financial and institutional characteristics.

For instance, countries with more developed or larger financial sectors may be prone to spillovers

due to greater interconnectedness across institutions and stronger macro-financial linkages.

Whereas bail-ins can be socially costly due to spillovers, bail-outs entail costs as well. The model

recognizes that bail-outs may have administrative fixed costs (for example, operating a program

of government investment and divestment). Bail-outs also involve fiscal costs and may threaten

sovereign debt sustainability. The model leaves aside this aspect since bail-ins can also have fiscal

consequences when spillovers endanger output and fiscal revenues. Box 1 shows that assessing

net fiscal costs of bail-outs based on up-front outlays may be misleading because mitigating the

output effects of a financial crisis can prevent even bigger tax revenue losses.

Crucially, the model emphasizes that bail-outs generate moral hazard by leading to insufficient

monitoring by banks; that is, to excessive risk taking. This can occur through two main channels.

First, bail-outs can undermine market discipline. When bank stakeholders expect to be bailed out,

they do not penalize banks for taking on excessive risk by charging higher interest rates on their

liabilities.

2

By weakening market discipline, the expectation of bail-outs can also lead to higher

leverage, possibly magnifying dangerous leverage cycles (Geanakoplos 2010; Adrian and Shin

2014). This can further increase risk taking because of a stronger risk-shifting motive: due to limited

liability, the bank neglects the losses associated with its default, so that it finds it optimal to exercise

less monitoring the more leveraged it is. Second, bail-outs can generate moral hazard by providing

transfers to bank shareholders and managers. For example, this can happen if bail-outs prevent

the ousting of bank management or preserve equity values. Then, by providing some

compensation even in the case of large losses, bail-outs promote risk taking.

3

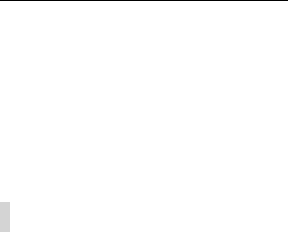

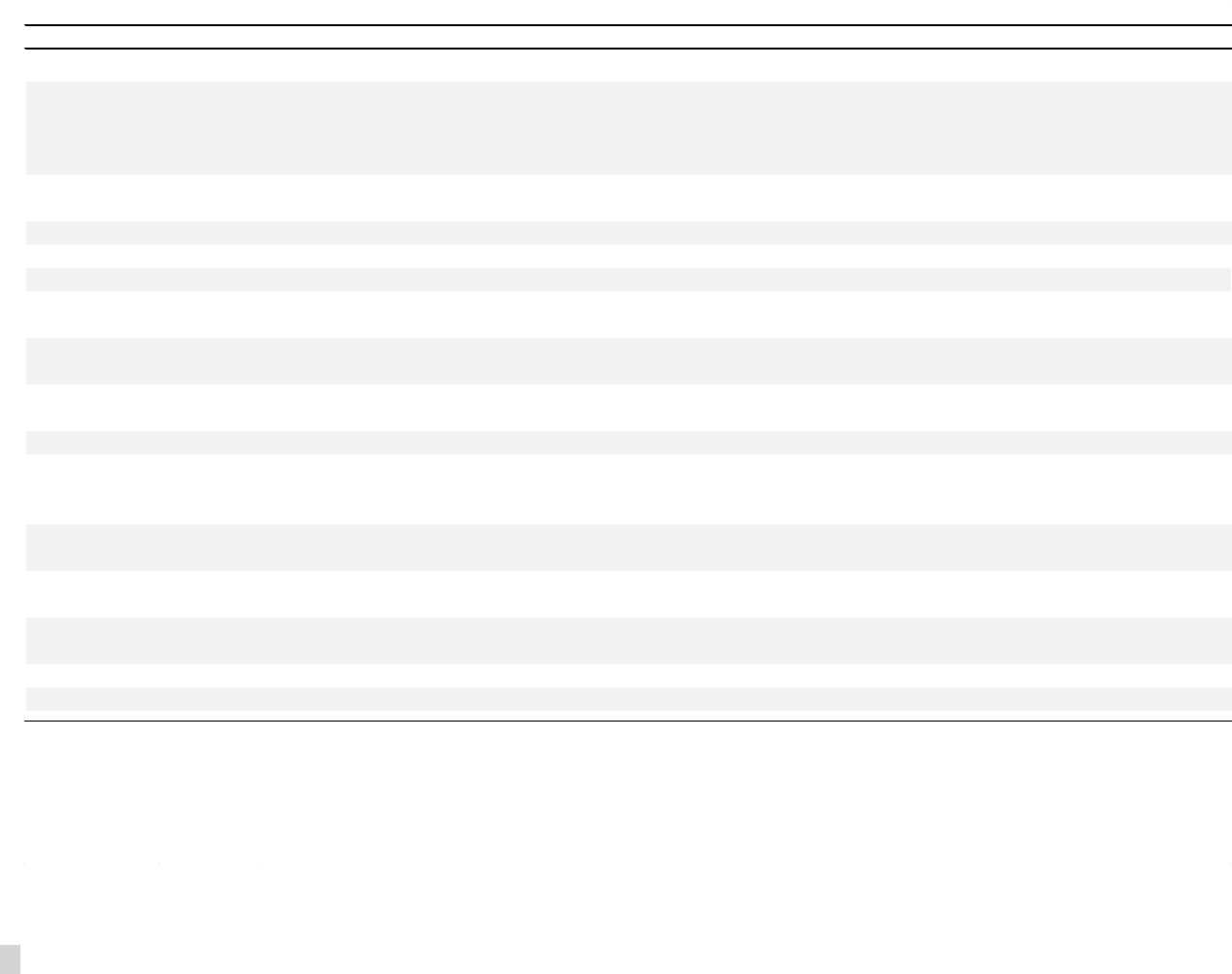

In designing a framework to address bank losses through bail-ins or bail-outs, policymakers need

to carefully consider the relative costs of these two instruments. Specifically, the model highlights

the key trade-off between the possible spillover effects associated with bail-ins and the moral

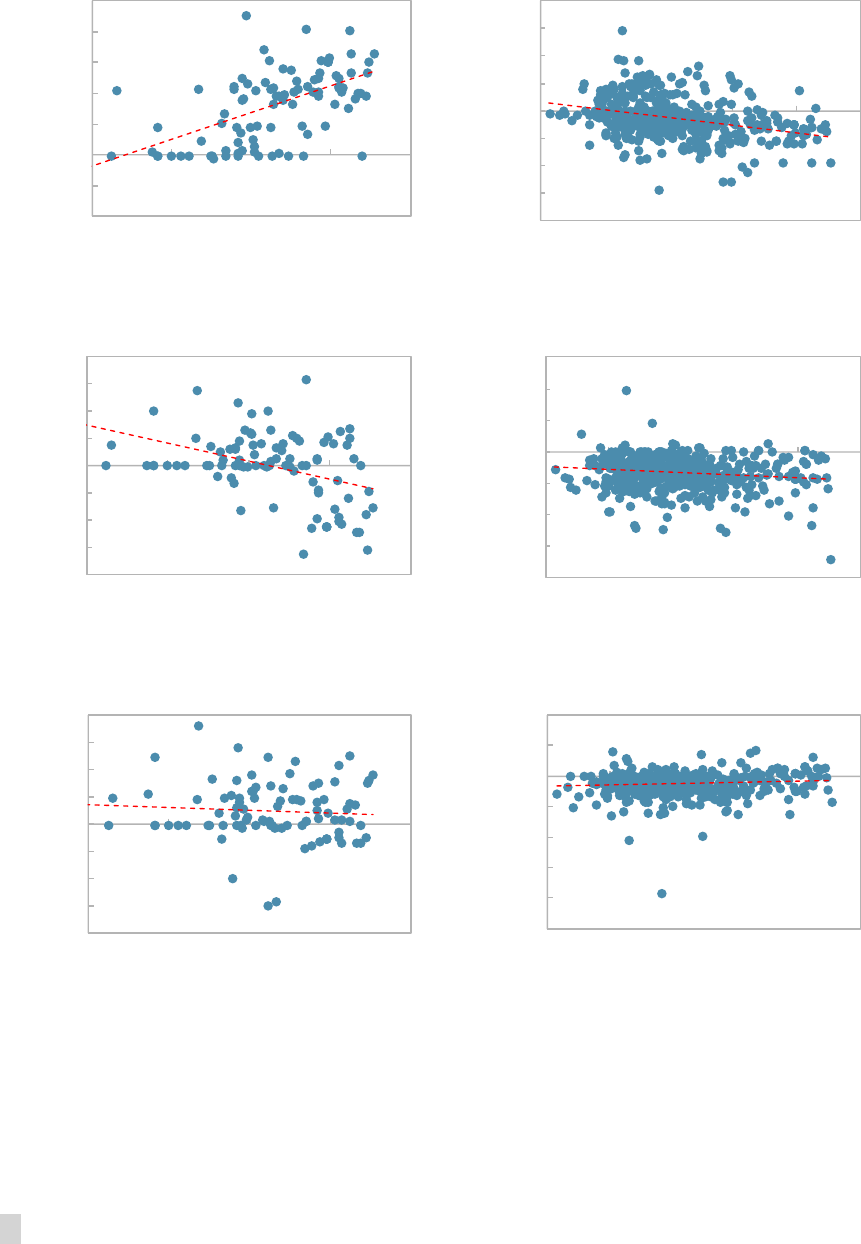

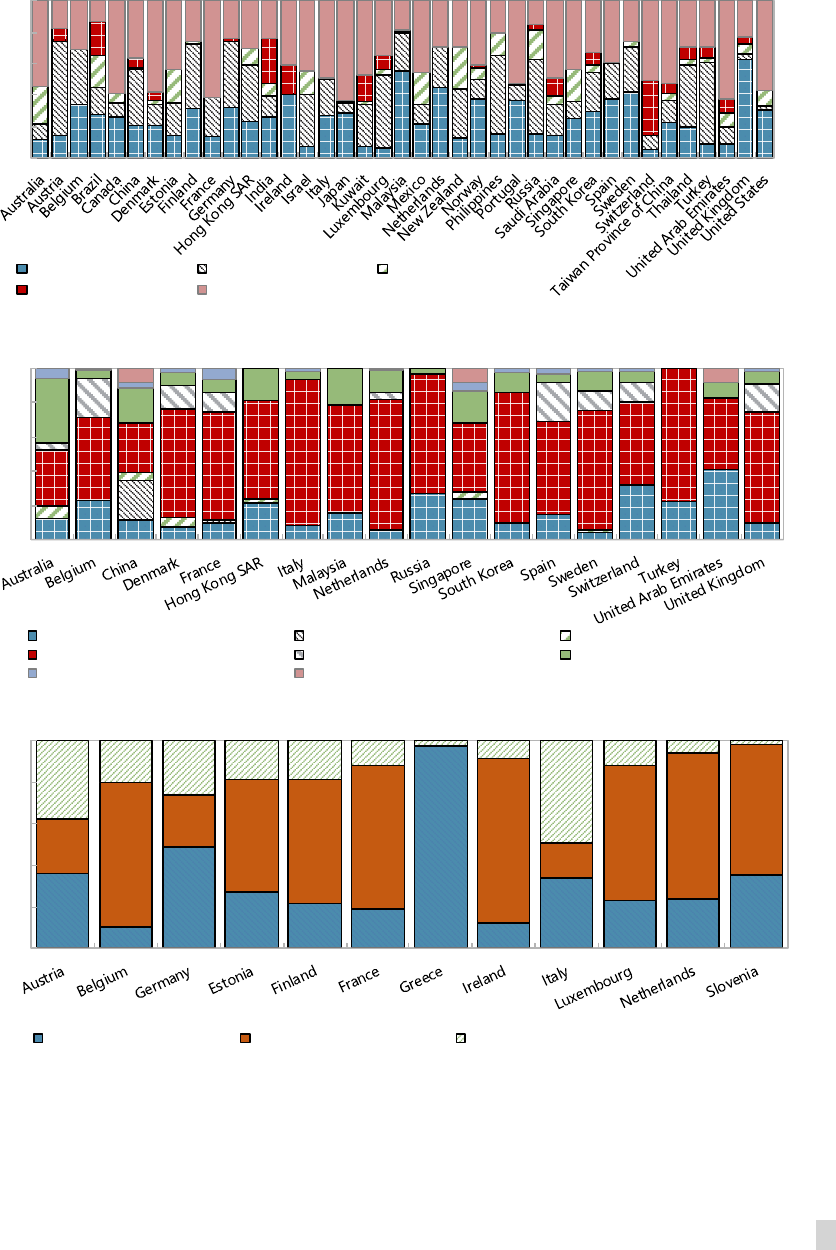

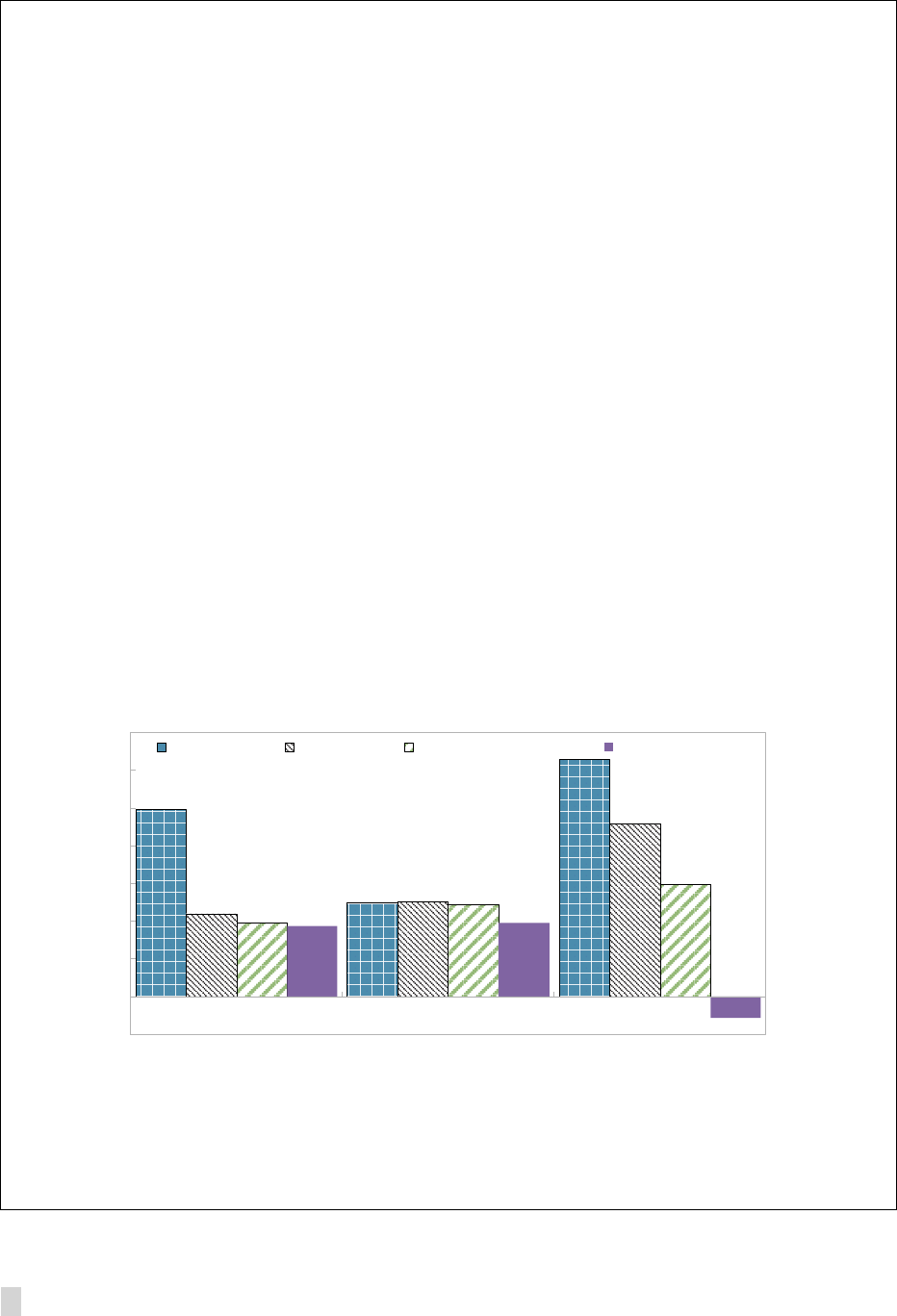

hazard consequences and fixed costs of bail-outs. Figure 1 illustrates the model implications about

how an optimal resolution approach should depend on the intensity of spillovers. The figure shows

how losses exceeding bank capital should be covered through bail-ins and bail-outs (panel 1), the

implications for bank risk taking (panel 2), and the consequences for social welfare (panel 3).

2

This argument hinges on the assumption that bank stakeholders can observe how much risk the bank is taking.

If they cannot, say, because of the complexity of a bank’s operations, they cannot penalize additional risk taking

by proportionally raising funding costs. So, market discipline is absent. Bail-outs then merely reduce funding costs

by lowering or eliminating the risk of bail-ins. In turn, this increases the bank’s franchise/charter value, thus

strengthening incentives for prudent risk management. See Section II for more on this counterargument.

3

Careful bail-out design could mitigate this effect. See Box 5.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 9

Figure 1. Optimal Resolution Framework as a Function of Spillover Intensity

Consider first the optimal resolution approach in the absence of spillovers. In this case, bail-ins

entail no social welfare costs since they simply reallocate losses from the bank to its creditors

without imposing externalities. By contrast, bail-outs are costly not only due to fixed costs but also

because they generate moral hazard and increase risk taking. So when spillovers are not a concern,

it is best to avoid bail-outs and absorb losses entirely through bail-ins.

When instead spillovers are present, bail-ins are socially costly since they not only involve a transfer

of losses from the bank to its creditors but also impose negative externalities on society at large.

In choosing whether to absorb bank losses with bail-ins or bail-outs, it is crucial to trade off these

externalities with the moral hazard consequences of bail-outs. When spillovers are relatively small,

it is preferable to suffer their consequences than generate moral hazard by providing bail-outs.

If spillovers are instead severe, bail-outs become more justified, possibly entirely replacing bail-ins

in exceptional cases. Panel 2 shows that such a large use of bail-outs has the potential to generate

serious moral hazard by increasing risk taking. Nonetheless, when spillovers are particularly severe;

for example, when an aggregate shock triggers a systemic banking crisis, it is preferable to tolerate

the consequences of moral hazard than suffer the destabilizing effects associated with bail-ins.

These insights call for a resolution framework that allows use of public funds if and when the risks

to macro-financial stability from bail-ins are exceptionally severe. Embedding the option to use

public funds in such exceptional cases completes the framework and also makes it more resilient

to the issues that may arise in practice (see below and Section III for more on this point).

The model provides three additional insights. First, even if bail-ins and bail-outs are used optimally

in line with the model prescriptions, social welfare is declining as spillovers become more severe

(panel 3). It is therefore crucial for policymakers not only to tailor bank resolution to the extent of

spillovers, but also to design resolution regimes that can reduce the potential for spillovers in the

first place.

4

This agrees with recent reform efforts to enhance the resolvability of large and complex

financial institutions via effective resolution powers and planning and adequate loss-absorbing

capacity. Furthermore, spillovers can be contained by restraining cross holding of bank debt within

the financial sector and applying enhanced prudential standards to financial institutions that are

too systemic to fail. Ample liquidity provision is also essential to contain the risk of spillovers, even

though at times of severe financial distress it is often difficult to ascertain whether a financial

institution is confronting a liquidity or solvency crisis. Finally, authorities should be mindful of

4

Measures to reduce spillovers should be designed in a way that does not impair risk sharing. For example, blunt

restrictions on interbank linkages may backfire by undermining risk and funding diversification.

TRADE-OFFS IN BANK RESOLUTION

10 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

financial institutions’ perverse incentives to become more systemic to benefit from future bail-

outs. This can occur both at the level of individual banks that may try to become more systemic—

for example, by increasing their balance sheets despite weak lending opportunities—or at the level

of the whole banking sector, for example, as banks correlate their exposures to increase systemic

risk (Schneider and Tornell 2004; Farhi and Tirole 2012).

Second, the model shows that when spillovers are relatively weak, the use of bail-outs should be

restrained. This raises a time-consistency problem. Policymakers may pledge ex ante to limit bail-

outs and use them only when spillovers are high. But, once bank failures occur, they may be

tempted to use them if spillovers exceed the fixed costs of bail-outs, neglecting the moral hazard

effects. To contain this time-consistency problem, it is imperative to put in place a resolution

framework that induces policymakers to rely on bail-ins when systemic concerns are absent or

moderate, and have a transparent approach for determining “systemic-ness.”

5

Importantly,

frameworks that induce the use of bail-ins should be credible. Otherwise investors and banks may

still expect to be bailed out, while being in fact bailed in during a crisis. This is a very dangerous

scenario since it entails both moral hazard costs and spillover effects.

Third, the model can also be used to analyze the role of leverage limits. By boosting capital ratios,

these limits reduce the likelihood that banks will face capital shortfalls and thus require socially

costly bail-ins or bail-outs. This benefit should be traded off, however, against the possible

negative effect of leverage limits on credit supply. Also noteworthy is that leverage limits reduce

the moral hazard effects of bail-outs since they lower the likelihood that a bank will benefit from

them. This improves the trade-off policymakers face and may provide more room to use bail-outs

if needed.

Four additional considerations may be relevant when it comes to deciding between bail-ins and

bail-outs, but they are not explicitly captured in the model. First, the case for bail-outs may seem

weaker if the sovereign faces debt sustainability problems because of the fiscal costs involved. But,

this concern must be weighed against the risk that the spillovers from bail-ins could themselves

endanger the fiscal position by lowering GDP and tax revenues. Therefore, whether fiscal concerns

should tilt the balance against bail-outs or bail-ins depends again on the strength of the spillovers.

Second, since banks most likely to receive bail-outs benefit from lower funding costs, they enjoy a

competitive advantage relative to others. This can generate significant distortions within the

banking sector, possibly leading to inefficient credit allocation and positions of market power. To

level the playing field, policymakers may thus consider imposing capital surcharges on those

institutions that are more likely to benefit from bail-outs. Further, levies could be imposed on a

resolution fund (where one exists) to mitigate bail-out benefits for large banks.

5

We use the term “systemic-ness” not necessarily in the context of individual financial institutions but also to

encompass situations that may raise systemic concerns (for example, clustered failures of many small banks). A

sound financial stability assessment framework is critical in making this determination. Such determination could

be made based on the growing toolkit to assess systemic risk (see, for instance, IMF-BIS-FSB 2009 and Blancher

and others 2013).

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 11

Third, the model neglects potential implementation costs and challenges associated with bail-ins

(Avgouleas and Goodhart 2015). For example, the bail-in process may be time demanding and

subject to legal challenges, especially in the context of cross-border resolution. Moreover, bail-ins

may face political opposition if they entail the transfer of bank ownership to foreign investors. Last

but not least, the extent of state ownership of the banking sector, depth of financial markets, and

availability of sophisticated private investors that can absorb the losses could affect the trade-off

a country may find itself facing.

Finally, the model considers the trade-offs from the point of view of a single policymaker. In some

cases, multiple policymakers from different jurisdictions or a college of policymakers would be

involved. For instance, in a currency union, one member state’s bail-out could affect its public debt

and may raise the perception that banks in other member states would also be bailed out in the

event of trouble. Then, what may seem optimal based on purely domestic considerations may end

up shifting risks and vulnerabilities to other countries. This points to the importance of cross-

border aspects of resolution frameworks, which are discussed in Section III.

II. EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

The discussion so far has highlighted the theoretical pros and cons of bail-ins and bail-outs. These

are based on assumptions―moral hazard effects of bail-outs and spillover risks of bail-ins―that

we seek to verify in this section. We rely largely on the existing literature but present new evidence

where needed. Appendix II provides information on the details.

A critical caveat to consider is the fact that resolution frameworks explicitly featuring statutory bail-

in powers are new and have not yet been fully tested. Furthermore, adequate loss-absorbing

capacity in sufficient quality and quantity is not yet in place. This hinders the feasibility of direct

comparisons of costs and benefits of bail-ins and bail-outs in today’s regulatory environment.

Rather, this section focuses on the trade-offs policymakers faced at the time of the crisis. Consistent

with this, we use a broad definition of bail-in encompassing potentially any resolution that

imposed losses on private stakeholders. Despite these limitations, we believe the empirical analysis

presented can be useful in considering the trade-offs entailed. As reforms since the crisis have

likely reduced the spillovers stemming from bank resolution, the estimates could be considered an

upper bound for the spillover effect associated with bail-ins in the current environment.

Do bail-outs entail moral hazard?

From a theory perspective, it is ambiguous whether bail-outs motivate banks to behave less or

more responsibly. On the one hand, bail-outs encourage risk taking in a classic moral hazard

interpretation. If bank managers and shareholders know that they will not have to bear the full

consequences of the risk they are taking when negative outcomes are realized, they have stronger

incentives to take on more risk. Moral hazard also weakens the incentives of shareholders,

creditors, and depositors to discipline banks. Less monitoring and underpricing of risk may, in turn,

result in riskier portfolios and higher leverage. On the other hand, there is also an argument in the

literature that bail-outs may result in higher franchise/charter values because they reduce funding

TRADE-OFFS IN BANK RESOLUTION

12 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

costs and, hence, discourage risk taking (Sarin and Summers 2016).

6

The lower rates promised to

creditors/depositors increase payoffs, conditional on success, to managers/shareholders (as

residual claimants). This enhances their incentives to choose safer portfolios.

It is an empirical question whether the former effect—banks take on more risk because they don’t

have to bear all the losses—or the latter—banks take less risk because bail-outs help them boost

their charter values—dominates.

7

The evidence is far from clear-cut: the expectation of bail-outs

does seem to reduce funding costs, but it is unclear if this results in higher or lower risk taking.

Indirect evidence on the effects of bail-outs is provided by cross-country studies that analyze the

system-wide association between government guarantees and risk taking—and, ultimately,

financial system fragility. Using deposit insurance, government ownership, and bank concentration

as proxies for the scope of the public financial safety net,

8

some report destabilizing effects (Caprio

and Martinez Peria 2002; Demirguc-Kunt and Detragiache 2002), while others find no significant

impact or even a stabilizing effect (Barth, Caprio, and Levine, 2004; Beck, Demirguc-Kunt, and

Levine 2006). The mixed findings can in part be attributed to differences in controlling for factors

such as charter values and institutional quality. If banks earn rents through limits on competition,

relationship lending, or reputation building, the effects of the public financial safety net on risk

taking may be mitigated because these rents increase charter value and lower moral hazard (Gropp

and Vesala 2004). If there is strong contract protection/regulation/supervision and low corruption,

incentives and opportunities for excessive risk taking may be reduced (Hovakimian, Kane, and

Laeven 2003). The macro-financial backdrop also plays a role: guarantees induce risk taking in

tranquil times but dissuade it during crises (Anginer, Demirguc-Kunt, and Zhu 2014). One

interpretation is that, by shielding banks from macroeconomic and contagion risks, guarantees

increase charter values and reduce risk taking.

With the recognition that cross-country studies may suffer from endogeneity problems, we turn

to studies that exploit banks’ varying likelihood of benefiting from bail-outs. Moral hazard effects,

if present, should be particularly visible for larger financial institutions—which expect or are

perceived as more likely to be bailed out. The literature shows that large banks indeed benefit from

lower borrowing costs and credit default swap (CDS) spreads.

9

Since the crisis, the funding

advantage of large banks—the too-big-to-fail subsidy—has been reduced but not eliminated (IMF

6

Franchise value is defined as the present value of the stream of profits that a firm is expected to earn as a going

concern. In banking, given the important role of regulation, charter value—the present value of being able to

continue to do business in the future and earn rents in a highly regulated environment with high barriers to entry—

is often used synonymously with franchise value (Demsetz, Saidenberg, and Strahan 1996; Furlong and Kwan 2006).

7

The model in Section I assumes that the former effect dominates to illustrate the trade-off between moral hazard

costs of bail-outs and spillover effects of bail-ins. Also note that the literature is mostly based on guarantees (in

many cases for depositors), which are distinct from bailing out equity holders or managers.

8

The reasoning for the last proxy is that an individual bank is more likely to be systemically important in a

concentrated than in a dispersed sector and, thus, more likely to benefit from public support measures.

9

See Acharya, Anginer, and Warburton 2014; Ueda and Weder di Mauro 2013; GAO 2014; and Santos 2014 for

evidence of the funding advantage enjoyed by large banks. Kroszner 2016 provides a thorough and critical review

of the literature.

(continued)

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 13

2014a; GAO 2014). But many studies focus on the gross subsidy. It is plausible that the subsidy net

of the higher regulatory costs now faced by larger banks—including enhanced capital and liquidity

requirements and closer supervision—is lower today.

10

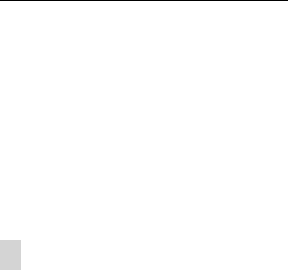

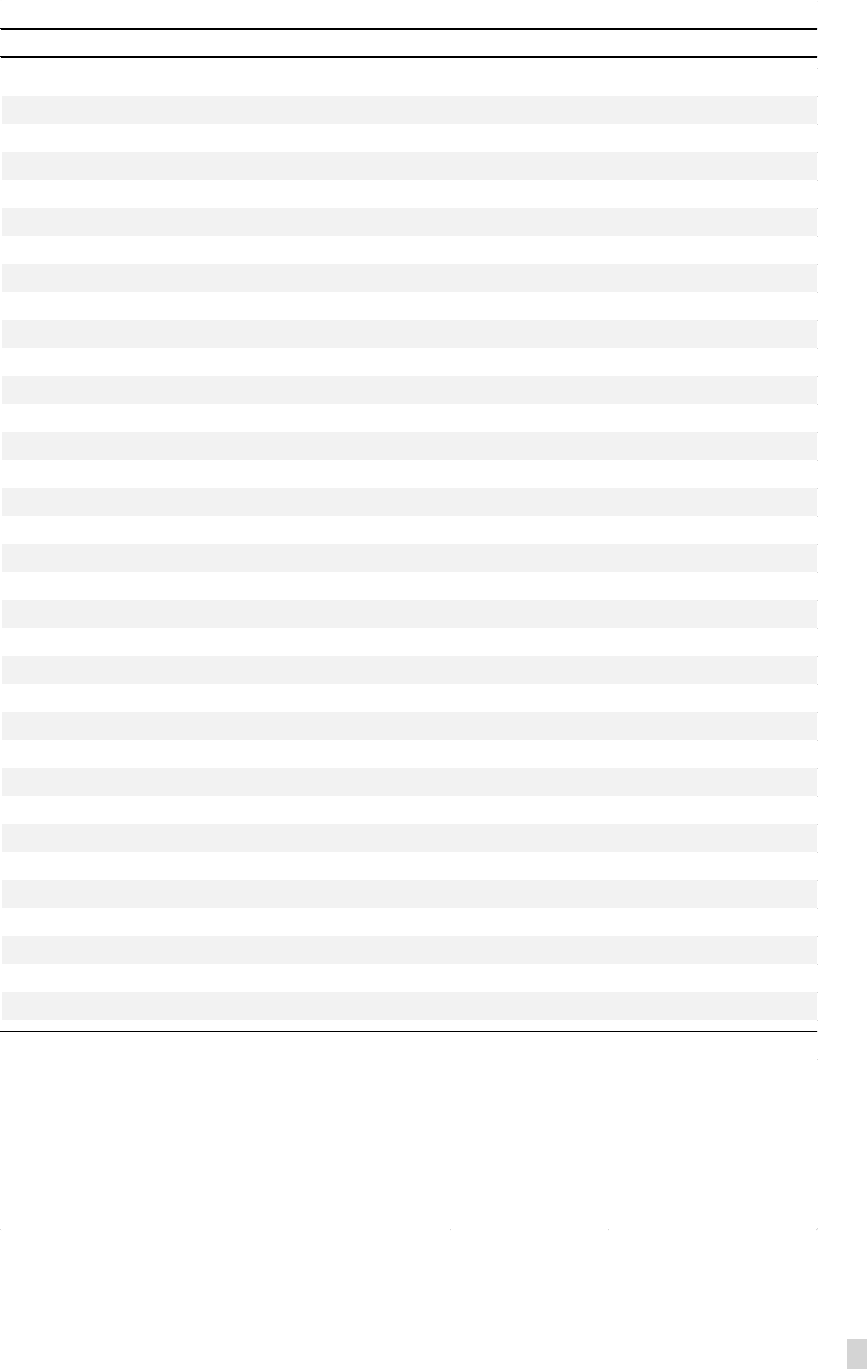

To provide stronger evidence that the lower funding costs enjoyed by large banks are linked to

the expectations of bail-outs, we look at how funding costs change around episodes that affect

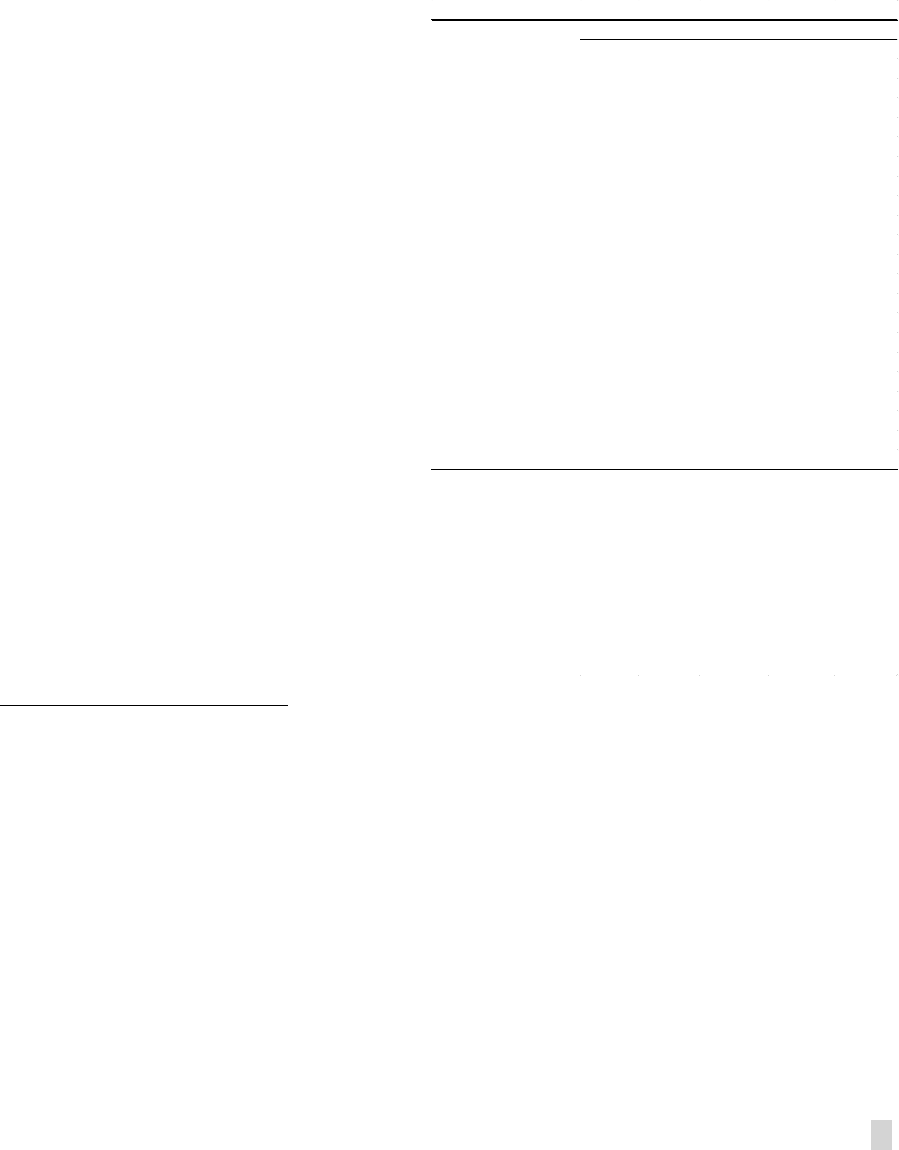

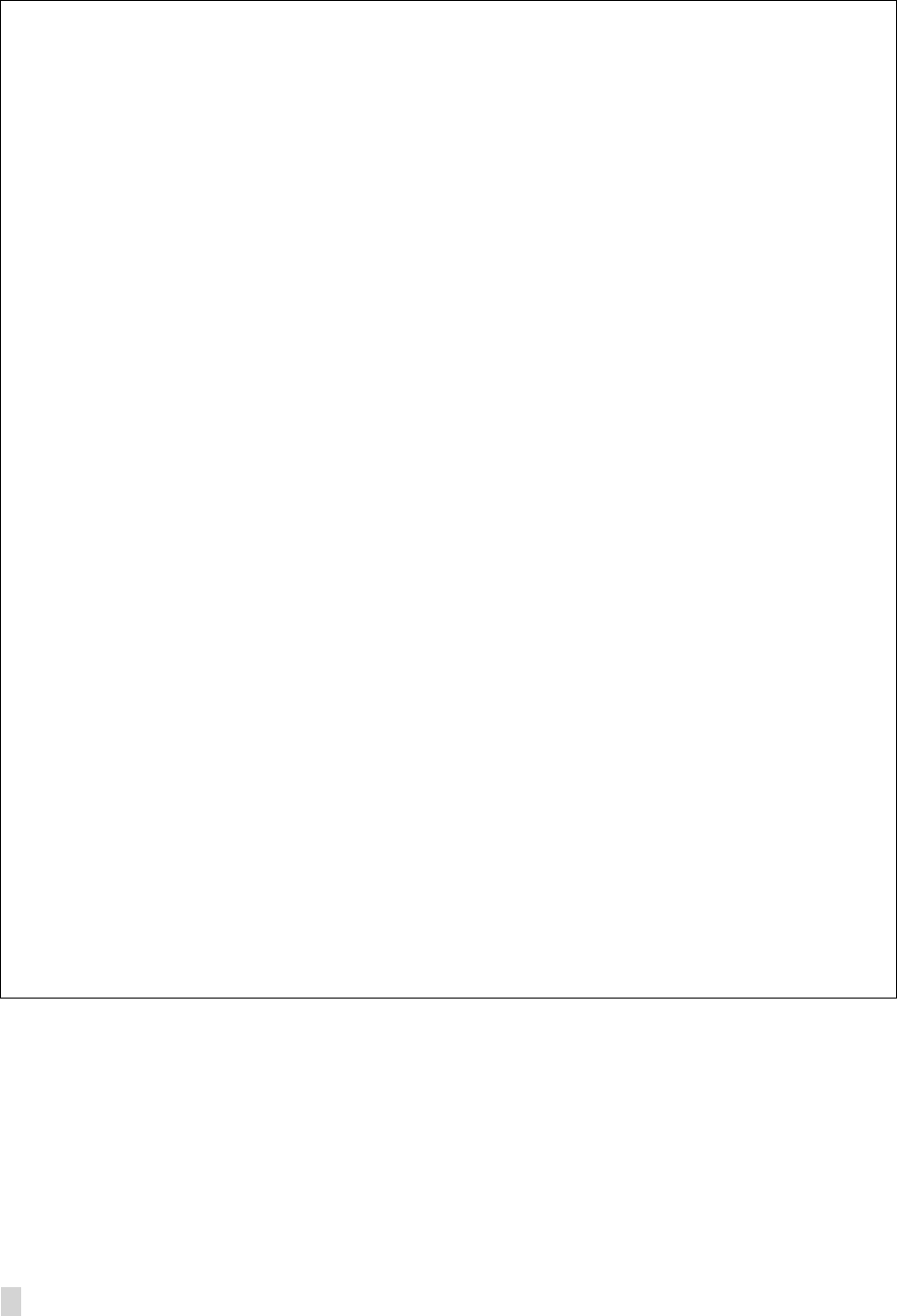

the likelihood of bail-outs. Concretely, we look at the change in CDS spreads and equity prices

following the failure of Lehman Brothers and the passage of the Emergency Economic Stabilization

Act of 2008―which established the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP)―as well as the

beginning of the European bail-outs, distinguishing large banks from small banks.

11

We assume

that the first of these events—the Lehman

bankruptcy—sent a signal that policymakers’

appetite for bail-outs was low. The latter two

would signal the opposite. Figure 2 presents

the raw data of daily changes in spreads and

prices. As anticipated, large banks suffered

more than small banks with the Lehman

failure—consistent with a decline in their

funding cost advantage—and enjoyed better

outcomes when TARP was approved as well

as when Dexia was recapitalized. Importantly,

these relationships survive in an event-study

setup (Table 1). In fact, when changes are

calculated controlling for market

benchmarks, the relationship between size

and equity returns is statistically significant

and positive in the European event as well,

while the reaction in CDS spreads is still

insignificant.

12

Whether lower funding costs due to bail-outs

translate into more risk taking is not clear-

cut. Using mainly precrisis data, some studies

10

A net subsidy may still exist if market perceptions of bail-out probability have not changed yet. See Elliott 2014

for further discussion.

11

The event we use for Europe is the capital injection to Dexia in September 2008. There were other events between

October and December of the same year involving government interventions (capital injections and asset/debt

guarantees) in other European banks (see Fratianni and Marchionne 2013 for a list). The key insights from examining

these are similar. Note that comparing the failure of Lehman Brothers to the recapitalization of Dexia (and others)

is difficult, given the systemic nature and shock value of the former.

12

This insignificance may be due to pooling the banks located in the country where the event took place with

those in other countries. To explore this, we split the sample and execute the event studies separately for US and

non-US banks in the Lehman and TARP events and for EU and non-EU banks in the Dexia event. The findings are

comparable to those obtained in the pooled sample: even though they are smaller in magnitude, the coefficient

on bank size has the same sign and is statistically significant in the subsamples of non-US and non-EU banks.

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Lehman Lehman TARP TARP Dexia Dexia

Size 4.147* 2.816 -8.641*** -5.723* -1.394 0.086

(2.405) (3.650) (2.588) (3.061) (2.007) (2.233)

Constant -36.62 -28.82 94.21*** 133.8*** 20.00 5.016

(29.12) (48.92) (30.93) (41.03) (26.03) (29.93)

Observations 79 79 79 79 79 79

R squared 0.331 0.295 0.478 0.621 0.454 0.500

Country FE NO YES NO YES NO YES

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

Lehman Lehman TARP TARP Dexia Dexia

Size -1.565** -0.536** 2.033*** 2.412** 1.651*** 2.014***

(0.678) (0.233) (0.549) (0.916) (0.426) (0.499)

Constant 18.68* -28.52*** -14.63* -43.96*** -10.47* -28.30***

(9.934) (2.728) (7.359) (10.72) (5.695) (5.844)

Observations 461 461 461 461 461 461

R squared 0.586 0.581 0.464 0.494 0.454 0.511

Country FE NO YES

NO

YES NO YES

Panel 1. Cumulative Abnormal Changes in the Cross Section of CDS spreads

Table 1. Market Reaction to Bail-out Events

Note: Cumulative abnormal CDS spread and equity price changes are computed

over a seven-day (t−3 to t+3) event window for TARP and Dexia and a four-day (t

to t+3) event window for Lehman, defined relative to the bail-out event date (t),

over 2008:Q1–2016:Q3. Bail-out event dates are recorded on September 15, 2008

(Lehman bankruptcy), October 30, 2008 (TARP passage), and September 30, 2008

(Dexia capital injection). Size is the log of total assets. Standard errors clustered at

the country level are displayed in parentheses; statistical significance at the 10

percent, 5 percent, and 1 percent levels is denoted by *, **, and ***, respectively.

For sample coverage and further details on the empirical analysis, see Appendix II.

Panel 2. Cumulative Abnormal Changes in the Cross Section of Equity Prices

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P.; SNL Financial; Thomson Reuters Datastream; and

IMF staff calculations.

TRADE-OFFS IN BANK RESOLUTION

14 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 2. Bank Size and Reaction to Events

Altering Bail-out Expectations

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P.; Thomson Reuters Datastream; and IMF staff calculations.

Notes: Daily changes in spreads and prices around the events affecting bail-out expectations are

shown. The event dates are recorded as September 15, 2008 (Lehman bankruptcy), October 30, 2008

(TARP passage), and September 30, 2008 (Dexia capital injection). For sample coverage and further

details on the empirical analysis, see Appendix II.

y = 8.6352x - 76.159

R² = 0.3051

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

100

8 10 12 14 16

CDS spreads, percent change

Total assets (log)

Lehman Bankrutpcy

CDS spreads

y = -2.8168x + 23.622

R² = 0.1166

-80

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

6 8 10 12 14 16

Equity prices, percent change

Total assets (log)

Lehman Bankruptcy

Equity prices

y = -6.6207x + 82.936

R² = 0.1528

-80

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

8 10 12 14

16

CDS spreads, percent change

Total assets (log)

TARP Passage

CDS spreads

y = -0.8678x - 4.1854

R² = 0.0202

-80

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

6 8 10 12 14 16

Equity prices, percent change

Total assets (log)

TARP Passage

Equity prices

y = -1.0101x + 22.626

R² = 0.0051

-80

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

8 10 12 14 16

CDS spread, percent change

Total assets (log)

Dexia Capital Injection

CDS spreads

y = 0.4106x - 8.986

R² = 0.0089

-100

-80

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

6 8 10 12 14 16

Equity prices, percent change

Total assets (log)

Dexia Capital Injection

Equity prices

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 15

show that larger banks take on larger positions on riskier loan segments, greater reliance on riskier

funding, lower buffers against potential loan losses, and greater loan losses after a shock).

13

Examination of our sample covering a set of global banks since 2008 gives some indication that

large and small banks respond differently to a bail-out event: large banks increase risk taking while

small ones decrease it (see Black and Hazelwood 2012 for a similar finding). This is, however, not

robust across specifications. The evidence on whether large banks take on more risk in general is

similarly mixed: large banks tend to have less

core capital to total assets relative to risk-

weighted assets—pointing to riskier

portfolios—but also higher distance-to-

default and lower nonperforming loan ratios

(Table 2).

14

Of course, plotting various

indicators against a proxy for bail-out

probability does not account for other factors

that may be at play. Yet regressions

controlling for bank characteristics and fixed

effects paint a similar picture: not all risk-

taking measures point in the same direction

(Table 3).

15

A possible explanation is that

tighter postcrisis supervision has prevented

large banks from taking excessive risk.

16

The impact of bail-outs on funding costs and

risk taking is analyzed also in a series of

recent studies using German data that allow

for better identification. Some find a positive

link between bail-out expectations—

predicted using regional political factors—

and probability of distress (Dam and Koetter

2012). Furthermore, in a natural experiment

13

See, among others, Boyd and Gertler 1994; Hovakimian and Kane 2000; and Schnabel 2009 for evidence of

excessive risk taking by large banks. In addition to having higher stand-alone risks, large banks contribute more to

systemic risk. See Laeven, Ratnovski, and Tong 2016 and the references therein.

14

Large banks may extend riskier loans on an individual basis, but this may not be reflected in a riskier loan portfolio

or balance sheet because of greater diversification. Empirical support for such an effect of diversification on bank

risk, however, is limited: better diversification resulting from larger size can generate both scale economies and

risk-taking incentives (Hughes and Mester 2013), and large banks may use their diversification advantage to

operate with lower capital ratios and pursue riskier activities (Demsetz and Strahan 1997).

15

Based on a comparison of return on assets and return on equity between large and small banks, there is no

obvious sign of potential charter-value effects (Table 2). Controlling for bank and time fixed effects (and a measure

of bank risk) reveals a positive, albeit not robust, relationship between bank profitability and size (Table 3). This is

in line with findings reported elsewhere (see, for instance, Goddard, Molyneux, and Wilson 2004).

16

Recent research argues that the relationship between bank size and risk taking changed in the aftermath of the

crisis—as did the relationship between bank size and funding cost advantage. See, for instance, Bhagat, Bolton,

and Lu 2015, who report that the positive correlation between total assets and z-scores breaks down in 2010–12.

Obs. Mean Std. Dev. Min. Max.

Large Banks

CDS spread 2,361 157.7 144.0 5.9 1623.0

Senior unsecured spread 101 169.0 150.5 13.1 901.8

Subordinated spread 108 350.6 164.8 45.4 860.9

CoCo spread 411 581.2 248.9 159.4 1837.8

Z-score 1,044 3.9 0.9 1.6 7.9

Tier 1 ratio 1,426 11.7 2.8 6.7 26.4

Leverage ratio 936 9.1 13.1 2.8 71.7

NPL ratio 959 3.2 3.1 0.0 21.4

ROA 1,209 0.5 0.6 -2.8 2.4

ROE 1,223 9.1 8.4 -36.7 30.0

Small Banks

CDS spread 1,240 183.0 166.3 1.2 1698.7

Senior unsecured spread 41 181.9 165.0 20.1 641.7

Subordinated spread 18 322.5 122.7 215.6 667.6

CoCo spread 137 667.3 290.8 146.1 2050.6

Z-score 10,741 3.6 1.0 -2.4 6.0

Tier 1 ratio 11,699 12.4 3.2 6.7 27.9

Leverage ratio 10,856 12.8 16.6 2.7 82.0

NPL ratio 11,010 3.5 4.9 0.0 85.4

ROA 12,609 0.9 0.8 -2.8 3.6

ROE 12,540 9.2 7.5 -35.9 34.9

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P.; SNL Financial; Thomson Reuters Datastream;

and IMF staff calculations.

Table 2. Funding Costs, Risk, and Profitability in Large versus Small Banks

Note: Large banks are defined as those with assets in the top percentile. CoCo

refers to contingent convertible bonds. Z -score is computed as equity capital

ratio plus return on assets divided by the standard deviation of return on

assets (calculated over a rolling window of 10 quarters). Tier 1 ratio is defined

as the ratio of Tier 1 capital to risk-weighted assets, and leverage ratio is

defined as the ratio of Tier 1 capital to total tangible assets. NPL ratio is the

ratio of nonperforming loans to total loans. ROA is return on average assets

and ROE is return on average equity. For sample coverage and further details

on the empirical analysis, see Appendix II.

TRADE-OFFS IN BANK RESOLUTION

16 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

where government guarantees for savings banks were removed due to litigation, banks that lost

their guarantees are shown to cut off the riskiest borrowers, adjust their liabilities away from risk-

sensitive debt instruments, and see their bond yield spreads increase (Gropp, Gruendl, and Guettler

2014).

However, others report that capital support—instrumented by exploiting geographically

driven differences in insurance and acquisition frameworks across Germany—reduces bank risk

taking as well as lending (Berger and others 2016).

17

A growing body of literature on the US experience with TARP arrives at mixed conclusions. Some

argue that banks receiving government funds shifted to riskier segments within the same asset

class, resulting in increased volatility and default risk, despite improved capital ratios (Duchin and

Sosyura 2014). Others deliver a more nuanced message that weak banks—those with low charter

values and high leverage—increased risk taking, but strong banks—those with high charter values

and low leverage—decreased it (Schenk and Thornton 2016) and that TARP reduced systemic risk,

especially in larger, safer banks located in economically stronger areas (Berger, Roman, and

Sedunov 2016).

Analysis using changes in bank ratings to gauge the perceived likelihood of government support

suggests that nuances exist through time in addition to across banks: higher bail-out probabilities

result in higher risk taking in tranquil periods but in less risk taking when there is a crisis (Damar,

Gropp, and Mordel 2012).

18

This is consistent with the argument that the charter value effect may

dominate when the economy is hit by a systemic shock and contagion risk is high.

17

They interpret this as support for the theory showing that capital reduces moral hazard (Morrison and White

2005) and strengthens banks’ monitoring incentives (Allen, Carletti, and Marquez 2011; Mehran and Thakor 2011).

18

In October 2006, Dominion Bond Rating Service introduced a change to its rating system to explicitly account

for the potential of government support. This led to rating changes that were not a result of changes in the

respective banks’ credit fundamentals. Damar, Gropp, and Mordel (2012) exploit this natural experiment.

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4) (5)

(6) (7)

(8) (9)

(10) (11) (12)

Z

-score Z

-score

Tier 1

ratio

Tier 1

ratio

Leverage

ratio

Leverage

ratio

NPL

ratio

NPL

ratio

ROA

ROA

ROE ROE

Size

-0.1481***

-0.1348***

-3.1073***

-1.7066***

-0.9142***

-0.6241***

-1.6868***

-0.5621***

0.6799*** 0.0275

7.9816*** 0.2720

(0.0238)

(0.0220) (0.3982) (0.2557) (0.3459) (0.1424) (0.5101)

(0.1991) (0.1099) (0.0370) (1.4334) (0.3393)

Loan ratio

-0.0059***

-0.0061***

-0.1233***

-0.1344***

0.0312** 0.0194** -0.0139 -0.0089 0.0164***

0.0004 0.2060*** -0.0098

(0.0012) (0.0011)

(0.0250)

(0.0223) (0.0134) (0.0097) (0.0201) (0.0143) (0.0044) (0.0031) (0.0559) (0.0321)

Deposit ratio -0.0001

0.0000

-0.0245 -0.0275*

-0.0161 -0.0180**

-0.0024

0.0059 0.0201***

0.0119*** 0.2111*** 0.1401***

(0.0011) (0.0011) (0.0189) (0.0165) (0.0104) (0.0082) (0.0229) (0.0175) (0.0044) (0.0037) (0.0567) (0.0384)

Z

-score

3.6889*** 1.1025***

43.9870***

9.8422***

(0.2904) (0.1382) (3.8339)

(1.2880)

Observations 11,259

11,259 12,317 12,317 1,762

1,762 12,145 12,145 11,242 11,242

11,183 11,183

R

squared

0.160 0.172

0.263 0.070 0.365 0.310

Number of banks

583

583 634 634 312

312

634 634 584 584

581

581

Bank FE YES YES YES YES YES

YES

Quarter FE YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES

YES

YES YES

Country FE

YES

YES YES

YES

YES

YES

Table 3. Size and Risk Taking

Note: Size is the log of total assets. Loan ratio refers to gross loans in percent of total assets. Deposit ratio refers to total deposits in

percent of total assets.

Z-score is computed as equity capital ratio plus return on assets divided by the standard deviation of return on

assets (calculated over a rolling window of ten quarters). Tier 1 ratio is defined as the ratio of Tier 1 capital to risk-weighted assets, and

leverage ratio is defined as the ratio of Tier 1 capital to total tangible assets. NPL ratio is the ratio of nonperforming loans to total

loans. ROA is return on average assets and ROE is return on average equity. Standard errors are displayed in parentheses; statistical

significance at the 10 percent, 5 percent, and 1 percent levels is denoted by *, **, and ***, respectively. For sample coverage and further

details on the empirical analysis, see Appendix II.

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P.; SNL Financial; Thomson Reuters Datastream; and IMF staff calculations.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 17

When interpreting the mixed evidence, it is also important to consider that the moral hazard effects

of bail-outs might be attenuated by the fact that banks that are more likely to receive government

support might be subject to tighter scrutiny by supervisors and regulators. In this respect, the

postcrisis regulatory changes (for example, leverage ratios) may have helped limit risk taking by

systemically important financial institutions in the presence of implicit and explicit government

guarantees. While it is too early to judge, existing evidence on the role played by regulation and

governance in determining risk taking (Laeven and Levine 2009) supports cautious optimism.

Do bail-ins entail systemic spillovers?

We now turn to the spillovers associated with bail-ins before the regulatory reforms. Since these

reforms have likely reduced the magnitude and scope of these spillovers, the evidence should be

read as a rationale for the reforms, rather than as an estimate of potential spillovers under the new

resolution frameworks (see Section III and Box 3). We consider whether, during the crisis and in its

aftermath, bail-in of a financial institution led to a repricing of (bail-in-able) unsecured debt and

equity of other banks. Providing an accurate measure of the extent of spillovers is, however, an

arduous task for several reasons.

On the one hand, the analysis may underestimate the extent of spillovers because the decision to

impose losses on unsecured creditors is endogenous: aware of the possible spillovers,

policymakers may use bail-outs rather than bail-ins in the context of a systemic crisis or failure of

a large, complex, interconnected institution. Further, there have been very few events during which

bail-in of private stakeholders has not been combined with (or has not been a precondition for)

injection of public funds, thus containing the potential for spillovers.

On the other hand, comovement in bank equity and bond prices may not accurately reflect the

kinds of spillovers highlighted in the model that are relevant for the bail-in/out trade-off (for

example, those due to fire sales or a sudden shift to a worse equilibrium driven by heightened risk

aversion). Comovement may instead arise because a bail-in reveals genuine information about a

deterioration of the macro-financial outlook or because it leads investors to update their beliefs

about the credibility of a bail-in regime. Distinguishing between spillovers and aggregate shocks

is particularly challenging because the potential for spillovers is much greater in the context of a

deteriorating outlook. So what in normal times would be an idiosyncratic bail-in may turn into an

event that leads to panic among holders of claims on unaffected banks.

With these significant caveats, we start our analysis by looking at some European resolution cases

where losses were imposed on private stakeholders (see list in Appendix Table 1). Given the

heterogeneity of the surrounding circumstances (applicable resolution framework, extent of losses

imposed and of public support, type of instrument or investor bailed in, macro-financial backdrop,

etc.), we analyze each event separately. It is important to note that these cannot be regarded as

examples of good resolution practice. Most occurred before the adoption of the new regulatory

standards and resolution frameworks compliant with the KA. As such, the new frameworks are

likely to deliver better outcomes, especially once they become fully operational. That said, these

examples provide insights into the challenges the new frameworks are meant to tackle.

TRADE-OFFS IN BANK RESOLUTION

18 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

(1) (2) (3)

(4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16)

Austria Cyprus

Denmark

(1)

Denmark

(2)

Greece (1) Greece (2) Greece (3) Italy (1) Italy (2) Netherlands

Portugal

(1)

Portugal

(2)

Slovenia Spain (1) Spain (2)

United

Kingdom

Country -1.059*** - -7.590*** -3.618** -16.76***

-5.239*** 11.09 0.390 -0.827 -6.236*** -13.18*** -5.369*** - -5.739** -5.032*** 1.963

(0.209) (0.969) (1.455) (2.995) (1.620) (9.602) (0.913) (1.334) (0.961) (1.709) (0.133) (2.254) (1.446) (1.653)

EU less country -0.915*** -2.971*** -1.097*** 2.083** -2.498** -3.515*** 0.626 -0.339 -2.393 1.744 -1.098** -0.519** -1.808** -1.338* -2.613*** -2.359***

(0.337) (0.914) (0.367) (0.851) (1.099) (0.845) (0.542) (0.493) (1.522) (1.184) (0.557) (0.256) (0.705) (0.686) (0.938) (0.856)

Russia -2.802**

(1.277)

Constant 1.008*** -0.906*** 0.441** -1.590*** 0.217 0.938*** 0.146 -0.858*** -1.292*** -0.407 -0.252 0.361*** 0.475** -1.020*** -0.978*** 2.345***

(0.0853) (0.257) (0.214) (0.260) (0.325) (0.267) (0.193) (0.213) (0.186) (0.961) (0.241) (0.0896) (0.229) (0.220) (0.219) (0.309)

Observations 582 553 538 578 545 551 580 577 579 552 562 580 557 550 553 554

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16)

Austria Cyprus

Denmark

(1)

Denmark

(2)

Greece (1) Greece (2) Greece (3) Italy (1) Italy (2) Netherlands

Portugal

(1)

Portugal

(2)

Slovenia Spain (1) Spain (2)

United

Kingdom

Country 3.459** -

-9.034*** -7.411*** - - - 6.986*** 0.153 8.874** 7.840* -1.161 - -3.640 4.328** 1.848***

(1.476) (1.713) (1.300) (1.460) (1.506) (3.628) (4.333) (1.478) (3.937) (1.797) (0.360)

EU less country 0.845 1.356* -5.785*** -1.956 4.457** 4.898*** 0.976 4.146*** -0.762 -0.245 2.667* 3.593*** 4.156** 1.280 2.488*** 1.325***

(1.816) (0.740) (1.925) (1.602) (2.232) (1.427) (0.973) (1.177) (1.053) (1.558) (1.497) (0.779) (1.796) (1.127) (0.900) (0.420)

Russia 0.244

(1.103)

Constant -4.608*** 3.136*** 0.876 -0.579 -9.867*** 1.094 -2.301*** -1.600** -0.193 -1.433 0.800 0.270 -0.282 -1.150** 3.685*** -0.411

(1.476) (0.394) (1.713) (1.300) (1.372) (0.963) (0.695) (0.667) (0.790) (1.254) (0.723) (0.380) (1.649) (0.539) (0.467) (0.360)

Observations 97 98 92 97 98 99 97 97 97 99 97 97 70 97 98 99

Panel 2.

Cumulative Abnormal Changes in the Cross Section of CDS Spreads

Panel 1. Cumulative Abnormal Changes in the Cross Section of Equity Prices

Table 4. Market Reaction to EU Bail-in Events

Note: Cumulative abnormal changes in equity prices and in CDS spreads are computed over a ten-day (t+1 to t+10) event window, defined relative to the event date (t), over the period between 2008:Q1 and

2016:Q3. Event window for Denmark (1) and Portugal (1) in Panel 1 and for Spain (2) and Cyprus in Panel 2 is (t+1 to t+5) while that for the United Kingdom in Panel 2 and Portugal (2) in both panels is (t to

t+1). Standard errors are displayed in parentheses; statistical significance at the 10 percent, 5 percent, and 1 percent levels is denoted by *, **, and ***, respectively. For sample coverage and further details on

the empirical analysis, see Appendix II. For a list and description of the events, see Appendix Table 1.

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P.; SNL Financial; Thomson Reuters Datastream; and IMF staff calculations.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 19

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16)

Wamu Silverton Independent Waterfield Midwest Tierone Enterprise Community Bankeast Easternshore Dupage Union Syringa Multiple1 Allendale Aztec

In-state

36.03

***

10.30

**

2.574

**

4.382

***

-4.671

***

-3.415

***

-1.362

***

-0.572 -2.545

-0.470

*

-0.483 -4.623** -1.733*

2.372

***

-2.327

***

-2.078***

(0.000) (0.012) (0.015) (0.000) (6.89-e05) (0.002) (3.06-e6) (0.599) (0.139) (0.057) (0.448) (0.022) (0.055) (0.000) (0.003) (1.88-e06)

Out-of-state

21.67

***

3.111

**

3.422

***

2.805

***

-7.971

***

-1.329

*

-0.934

***

-1.332

***

-5.160

***

-0.654

***

-0.821 -5.841*** -2.499***

2.459

***

-0.923

*

-1.511***

(0.000) (0.047) (6.81-e08) (0.002) (1.44-e06) (0.093) (1.13-e05) (0.007) (0.000) (1.82-e05) (0.156) (0.000) (3.51-e09) (9.2-e07) (0.051) (0.000)

Constant

3.463

***

1.503

***

-0.525

***

0.534

**

-1.238

***

-0.386 0.003

0.699

**

2.934

***

-0.132

*

-1.105*** -0.230 -1.038***

0.762

**

-0.667

***

1.408***

(1.83-e05) (0.002) (0.007) (0.031) (4.32-e05) (0.104) (0.977) (0.021) (0.000) (0.090) (1.59-e05) (0.323) (1.67-e05) (0.022) (0.009) (7.10-e06)

Observations

517 518 522 530 533 533 538 538 547 548 557 557 557 557 559 561

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16)

Wamu Silverton Independent Waterfield Midwest Tierone Enterprise Community Bankeast Easternshore Dupage Union Syringa Multiple1 Allendale Aztec

In-state

2.978

**

19.00

***

-9.390

***

1.725

**

4.333

***

-5.046

2.604

**

1.380 1.018

3.736

**

0.273 -12.32*** 1.167

2.978

**

3.078

*

1.097

(0.017) (3.67-e07) (1.49-e05) (0.429) (4.94-e05) (0.448) (0.017) (0.584) (0.550) (0.036) (0.956) (0.000) (0.776) (0.017) (0.087) (0.525)

Out-of-state

2.775

21.41

***

-5.117

**

1.823

**

3.121

***

1.698 0.613

4.656

**

7.735

***

4.256

***

-5.686** 0.293 5.094 2.775 0.385 -1.717

(0.411) (7.08-e06) (0.041) (0.028) (0.007) (0.417) (0.741) (0.014) (0.006) (2.4-e05) (0.012) (0.948) (0.178) (0.411) (0.749) (0.222)

Constant

1.767

**

-16.60

***

2.236

***

-2.738

***

-1.891

***

-3.171

***

-0.858

-3.398

***

-2.308

-2.272

***

9.287*** 2.932*** -1.387

1.767

**

-3.676

***

-1.076

(0.033) (0.000) (0.001) (0.000) (0.000) (0.002) (0.164) (0.006) (0.124) (8.99-e06) (0.000) (0.000) (0.112) (0.033) (6.64-e07) (0.106)

Observations

97 72 100 73 101 101 91 91 99 99 70 70 70 97 97 97

Table 5. Market Reaction to US Bail-in Events

Panel 1. Cumulative Abnormal Changes in the Cross Section of Equity Prices

Panel 2. Cumulative Abnormal Changes in the Cross Section of CDS Spreads

Note: Cumulative abnormal changes in equity prices and in CDS spreads are computed over a ten-day (t+1 to t+10) event window, defined relative to the event date (t), over the period between 2008:Q1 and 2016:Q3.

Event window for Easternshore, Enterprise, and Silverton in Panel 1 is (t+1 to t+5) while that for Midwest and Waterfield in Panel 1 and Easternshore and Enterprise in Panel 2 is (t to t+1). Event labeled “Multiple1”

represents two bail-in events which occurred on the same day (Millennium Bank NA and Vantage Point Bank). Standard errors are displayed in parentheses; statistical significance at the 10 percent, 5 percent, and 1

percent levels is denoted by *, **, and ***, respectively. For sample coverage and further details on the empirical analysis, see Appendix II. For a list of the events, see Appendix Table 2.

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P.; SNL Financial; Thomson Reuters Datastream; and IMF staff calculations.

TRADE-OFFS IN BANK RESOLUTION

20 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16)

Columbia Slavie Freedom Eastside Greenchoice NBRS Chicago Frontier Northernstar Crestview Highland Capitol Doral Edgebrook Premier Multiple2

In-state

-0.388 2.146** -0.978 1.109* 1.493*** -1.107** 2.811*** -2.579*** -0.574

2.042

***

4.496***

-1.924

***

3.141

***

1.193*** -1.114* -1.120**

(0.158) (0.039) (0.256) (0.577) (0.015) (0.035) (3.13-e05) (1.53-e07) (0.364) (0.001) (0.000) (3.95-e05) (0.000) (0.002) (0.078) (0.034)

Out-of-state

-1.223*** 2.044*** -0.608 -0.068 0.511 -1.987*** 2.637*** -2.679***

-0.708

**

0.884 5.686***

-2.359

***

5.113

***

1.247*** -1.613*** -0.395

(2.09-e05) (0.000) (0.211) (0.954) (0.780) (1.05-e08) (8.83-e08) (0.000) (0.028) (0.132) (0.000) (6.5-e07) (0.000) (6.57-e05) (5.61-e08) (0.455)

Constant

0.141 0.381** -0.875*** 0.872*** -0.526* 0.878*** 0.777** -0.594**

0.599

***

-1.063

***

-1.238***

0.764

***

1.117

***

0.112 0.868*** -1.179***

(0.450) (0.044) (0.000) (0.001) (0.058) (1.15-e08) (0.019) (0.015) (0.005) (0.001) (0.000) (0.007) (0.001) (0.620) (5.70-e07) (0.002)

Observations

561 561 562 562 562 568 568 568 570 570 570 572 573 576 576 578

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16)

Columbia Slavie Freedom Eastside Greenchoice NBRS Chicago Frontier Northernstar Crestview Highland Capitol Doral Edgebrook Premier Multiple2

In-state

5.528* 10.11*** 1.232*** 0.754 -7.502*** 4.185*** -0.232 -6.486*** 0.808 0.478 -2.367

5.431

**

-8.613

***

1.303** 1.629 2.197*

(0.069) (0.002) (0.820-e09) (0.584) (1.19-e05) (2.52-e10) (0.725) (4.28-e05) (0.331) (0.588) (0.429) (0.021) (0.000) (0.044) (0.599) (0.067)

Out-of-state

4.821*** -1.020 -0.007 4.040 -3.358 2.613*** 2.088* -5.442*** 0.327 1.329 -2.571***

8.308

**

-2.057 1.962*** 1.314 2.615

(0.000) (0.862) (0.995) (0.179) (0.146) (0.008) (0.057) (4.50-e07) (0.769) (0.298) (0.005) (0.043) (0.330) (0.000) (0.588) (0.127)

Constant

-6.580*** -6.353*** 0.841*** 1.340* 4.417*** -1.014** -1.214*** 5.544***

2.508

***

-2.820

***

2.259**

-5.988

***

-0.268 -1.386*** -3.630*** -1.232***

(0.000) (0.000) (2.96-e07) (0.062) (1.68-e07) (0.013) (0.008) (0.000) (8.72-e09) (7.41-e05) (0.010) (4.81-e06) (0.790) (0.000) (6.49-e07) (3.36-e08)

Observations

97 97 97 97 97 97 97 97 97 96 96 97 87 97 97 97

Note: Cumulative abnormal changes in equity prices and in CDS spreads are computed over a ten-day (t+1 to t+10) event window, defined relative to the event date (t), over the period between 2008:Q1 and 2016:Q3.

Event window for Chicago, Edgebrook, Freedom, Multiple2, and NBRS in Panel 1 is (t to t+1) while that for Columbia, NBRS, and Premier in Panel 2 is (t+1 to t+5). Event labeled “Multiple2” represents two bail-in events

which occurred on the same day (the Bank of Georgia and Hometown National Bank). Standard errors are displayed in parentheses; statistical significance at the 10 percent, 5 percent, and 1 percent levels is denoted by

*, **, and ***, respectively. For sample coverage and further details on the empirical analysis, see Appendix II. For a list of the events, see Appendix Table 2.

Table 5. Market Reaction to US Bail-in Events (continued)

Panel 1. Cumulative Abnormal Changes in the Cross Section of Equity Prices

Panel 2. Cumulative Abnormal Changes in the Cross Section of CDS Spreads

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P.; SNL Financial; Thomson Reuters Datastream; and IMF staff calculations.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 21

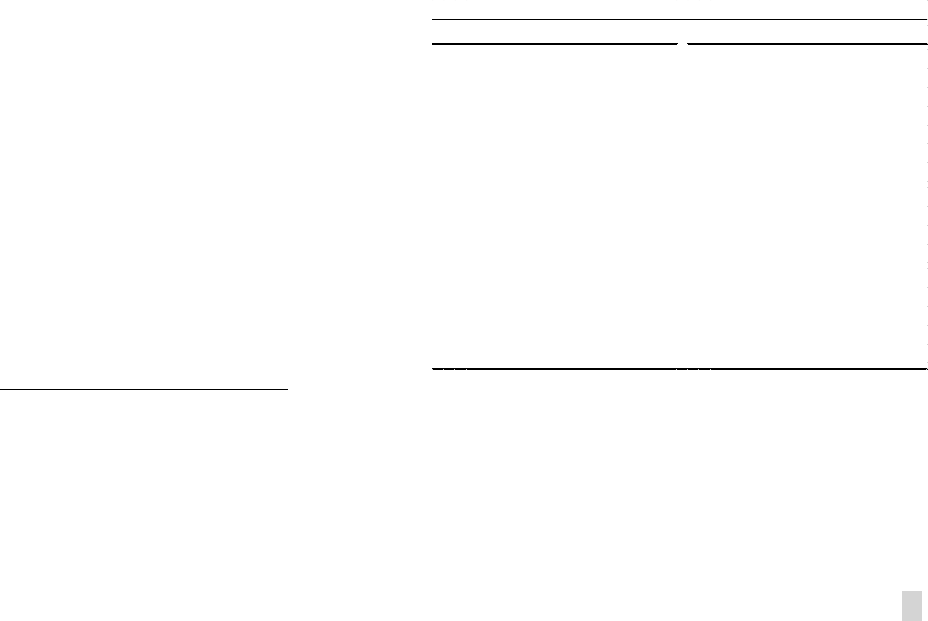

The empirical analysis suggests that imposing losses on unsecured creditors may have implications

not only for the bailed-in bank but also for other banks, especially when there is a considerable degree

of uncertainty and when macro-financial risks are high (Table 4). In 11 out of 16 cases, equity prices

for banks in EU countries other than the country in which the event took place show negative and

significant changes. This is notable because equity holders would suffer losses or be wiped out one

way or another independently of which debt securities are bailed in. In eight of these cases, CDS

spreads show significant increases.

20

Almost all of these cases (the asset transfer and bail-in in Cyprus;

two resolutions in Greece where shareholders and subordinated debtholders were significantly

diluted; Portuguese and Spanish bridge bank operations; and resolutions and recapitalizations in

Slovenia affecting five banks) took place in environments of heightened systemic risk.

Noteworthy in the European cases was a lack of significant prior experience with bank resolutions that

would impose losses on private stakeholders, insufficient clarity ex ante on how losses would be

allocated, and lack of explicit loss-absorbing capacity—as enshrined in the recent reforms. In

particular, which funding instruments get bailed in and by how much likely has a bearing on the extent

of spillovers.

21

An interesting case in point is Cyprus, where bail-in of unsecured bondholders and

depositors had negative effects in other EU and non-EU countries (primarily Russian banks). These

effects were mostly transitory, with CDS spreads and equity stabilizing about a week or so after the

shock. That said, there may be other costs associated with bailing in unsecured creditors, particularly

depositors, under an ad hoc regime (for example, bail-in of depositors in Cyprus led to claims for

compensation and may have also encouraged strategic defaults on bank loans, exacerbating the

nonperforming loan problem).

We also look at the resolutions executed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in the

United States. It is worth noting that many of these were handled through a purchase and assumption,

and the FDIC has a track record of imposing losses on bank creditors. We examine the cases that

involved relatively large banks—those ranked in the top 30 by total assets among the more than 500

bank failures the FDIC handled since 2000 (Appendix Table 2)—and find mixed results on the equity

prices and CDS spreads of other banks (Table 5). In half of the cases we find negative coefficients for

equity prices of banks located in a state other than that of the failed bank, while in roughly 30 percent

of the cases the coefficients are positive (the rest are insignificant). For CDS spreads, a third have

positive coefficients, and for about 10 percent they are negative. These are smaller percentages than

in the European case (of which two-thirds have negative significant coefficients for equity prices and

more than half have positive significant coefficients for CDS spreads). The lack of firm evidence is not

surprising given that the US cases involve relatively small, local banks.

With the caveat that the analysis does not control for any other factors that might have affected these

groups of banks differently around the event dates, the dynamics examined are consistent with the

20

We also examine senior bond spreads and observe that they rose as well, but these increases are not statistically

significant. One reason could be that the sample size is much smaller for bonds. Other data limitations could also be

an explanation—for example, the 10-year bonds we are looking at may or may not be subject to bail-in under the rules

of a particular jurisdiction. Yet another reason could be that bondholders believed that they would ultimately be wholly

compensated through litigation (in many cases, investors that were subject to losses took their case to courts).

21

Spillovers may also be affected by a bank’s liability structure and creditor hierarchy. See IMF 2013.

TRADE-OFFS IN BANK RESOLUTION

22 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

possibility that bailing in some banks may have had spillovers for creditors and equity holders in other

banks that were not yet subject to bail-ins. That said, the evidence is also consistent with markets

revising their beliefs about the macro-financial outlook or on the credibility of a bail-in regime. For

instance, negative effects in the European cases could reflect increased market discipline resulting

from the imposition of bail-ins or from signaling to investors that policymakers have become less

inclined to bail them out (Schafer, Schnabel, and Weder di Mauro 2016). There is no easy way to tell

the two interpretations apart. It is worth noting that the latter interpretation is less likely to apply in

the US case, given the commonality in macro-financial factors across states and the existence of a