RESEARCH REPORT

November 30, 2023 (51 pages)

The effectiveness of Duolingo vs.

classroom instruction on Spanish

speakers’ L2 English proficiency and

lexical development

Beatriz González-Fernández, University of Sheffield

Research Report

Table of Contents

Abstract..................................................................................................................2

Introduction............................................................................................................ 3

Effectiveness of MALL Apps................................................................................... 4

Motivation and Language Learning......................................................................... 6

Duolingo Course..................................................................................................... 7

The Present Study.................................................................................................. 9

Methodology.........................................................................................................10

Participants................................................................................................................ 10

Instruments................................................................................................................ 12

Procedure...................................................................................................................15

Analyses..................................................................................................................... 16

Results................................................................................................................. 17

L2 proficiency and Lexical Development..................................................................17

L2 Motivation and Engagement................................................................................18

Effect of Mode of Instruction and Learner Factors on L2 Development................20

Discussion............................................................................................................ 24

RQ1: Effectiveness of Duolingo for L2 Development.............................................. 24

RQ2: L2 Motivation and Engagement.......................................................................26

Conclusion............................................................................................................28

Notes....................................................................................................................29

Acknowledgements.............................................................................................. 29

References........................................................................................................... 30

Appendices...........................................................................................................34

Appendix A: Pre-test Motivation Questionnaire.......................................................34

Appendix B: Post-test Motivation and Engagement Questionnaire....................... 40

Appendix C: Additional Analyses..............................................................................47

1

Research Report

Abstract

Language learners around the world are increasingly employing applications (apps)

in order to learn second/foreign languages (L2). However, research on the

effectiveness of these apps for developing general language proficiency, particularly

compared to traditional classroom instruction, is still limited. The manuscript reports

a study that compares L2-English proficiency and lexical development by L1-Spanish

learners in app-based (i.e., Duolingo) versus classroom-based instruction.

Participants completed a background and motivation questionnaire, a test of L2

general proficiency and two tests of receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge

before and after a 16-week instruction period. The results showed a positive effect of

type of instruction in favor of Duolingo on general L2 proficiency and receptive

vocabulary development, and in favor of classroom instruction on listening scores.

For productive vocabulary knowledge, both groups exhibited comparable learning

gains. L2 motivation was high for both groups prior and after the study period, with

Duolingo learners generally reporting higher interest and motivation levels. These

findings demonstrate the effectiveness of Duolingo in developing general L2

proficiency and receptive vocabulary knowledge relative to classroom-based

instruction.

2

Research Report

Introduction

The way in which second/foreign languages (L2s) are learnt has experienced a shift

in recent decades, largely due to the surge in instructional technologies. Computer

and mobile-assisted language learning (CALL and MALL) tools and applications have

become increasingly popular among learners worldwide (Burston, 2015; Jiang,

Rollinson, Plonsky, et al., 2021; Loewen et al., 2019), significantly impacting the field

of (instructed) second language acquisition (SLA) in and outside the classroom. This

move became even more acute in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, when

platforms such as Duolingo experienced an increase in new learners of 101% only in

March 2020 (Blanco, 2020). Given their numerous affordances for L2 learning and

instruction (e.g., autonomy and flexibility of use), the adoption of MALL technologies,

and particularly language learning apps, is expected to continue flourishing and

expanding (Loewen, 2020).

Yet, despite the popularity and rapid expansion of language learning apps, research

investigating their effectiveness in promoting L2 proficiency development is lagging

behind adoption (Rachels & Rockinson-Szapkiw, 2018). As a consequence, many in

the SLA field remain skeptical about apps’ potential to be a legitimate alternative to

traditional language classroom instruction (Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky, et al., 2021;

Loewen et al., 2020). The present study aims to shed light on this issue by exploring

the effectiveness of Duolingo’s English course in facilitating the L2-English

proficiency and lexical development of L1-Spanish learners, and comparing it to the

linguistic development of similar learners enrolled in traditional face-to-face

classroom instruction.

Mobile-assisted Language Learning and Instructed SLA

Alongside traditional L2 classroom teaching, the use of language learning

technologies (CALL and MALL) is now considered one of the core contexts of

instructed SLA (Loewen, 2020). These technologies have been effectively employed

as complements to traditional L2 classroom instruction both during class time and

outside the class. For example, Guaqueta and Castro-Garces (2018) integrated

traditional English lessons with the use of Duolingo during in-class time for a

6-month period, and found not only improvement in learners’ vocabulary knowledge

but also a better attitude to the language learning process. Examining MALL use

outside the class, Wu (2015) found that combining traditional English instruction

with the autonomous use of a vocabulary-building app led to increased study time by

making use of ‘dead time’ (e.g., commuting), which in turn led to significant

improvement in their lexical knowledge compared to receiving only classroom

lessons. Some scholars even argue that MALL apps have the potential to further

transform language learning in the classroom, by moving away from traditional

textbooks towards adaptive learning platforms (Heil et al., 2016).

3

Research Report

However, Loewen (2020) suggests that MALL apps are perhaps more valuable as

independent-use instructional tools, as a means of learning an L2 when access to a

traditional classroom might not be an option. One of the main reasons for the rising

popularity of language learning apps is that they provide learners with a convenient

and affordable solution to L2 learning (Loewen et al., 2020; Rachels &

Rockinson-Szapkiw, 2018). Apps’ other beneficial affordances include: autonomy

(i.e., learners can choose what and how they want to study), flexibility of use in time

and location (i.e., learners can access and practice language learning anytime and

anywhere), individualization and personalization of the learning process (deliver

adaptive materials tailored to learners’ specific proficiency level, personal needs and

study habits) (Kukulska‐Hulme & Viberg, 2018; Loewen, 2020), or course availability

(in some cases, it may be the only alternative to learning minority or artificial

languages). Thus, although apps can be used as one of many tools for learning a

language (including traditional instruction), they are also being employed by learners

as the main or only form of autonomous L2 instruction (Loewen et al., 2020). Yet, it

is well established that the type of instruction learners receive influences their L2

development greatly (Norris & Ortega, 2000). Thus, understanding how effective

independent app-based instruction is for L2 learning relative to traditional classroom

instruction is crucial to advance our knowledge of MALL apps’ role in instructed SLA.

Effectiveness of MALL Apps

As MALL apps become more popular, it is more important for researchers and

practitioners to understand their effectiveness for language learning (Burston, 2015).

While most research on the use of MALL apps has focused on describing their

design instead of investigating their influence in L2 development (Shortt et al., 2023),

there has been in recent years a rise in studies examining the acquisition of L2s

through language learning apps (e.g., Jiang & Pajak, 2022; Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky,

et al., 2021; Loewen et al., 2019, 2020; Sudina & Plonsky, 2023).

The majority of MALL studies support the use of apps as effective learning tools

(Burston, 2015). Significant learning gains have been reported particularly regarding

reading ability (e.g., Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky, et al., 2021; Jiang & Pajak, 2022) and

knowledge of vocabulary and grammar at the receptive level (e.g., Loewen et al.,

2020; Rachels & Rockinson-Szapkiw, 2018). However, apps’ effectiveness in

developing oral skills and productive knowledge of lexis and grammar is far less

evident. Most studies do not focus on these aspects of language (Shortt et al.,

2023), and when they do, results show small (or even a lack of) significant gains in

listening skills (e.g., Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky, et al., 2021), speaking skills (e.g.,

Loewen et al., 2019, 2020; Lord, 2015) or productive vocabulary knowledge.

Regarding the latter, in a meta-analysis of research on the efficacy of apps for

developing L2 vocabulary, Lin and Lin (2019) found that only 7 out of the 29 target

studies examined included some focus on productive vocabulary knowledge; more

4

Research Report

importantly, they showed that learners’ scores in productive vocabulary measures

obtained a smaller effect size than in receptive vocabulary measures. Similarly,

Jiang, Rollinson, Chen, et al., (2021) found that productive vocabulary knowledge

experienced the weakest scores among their L2 measures, suggesting that apps

might be more facilitative in developing receptive vocabulary knowledge. Therefore,

further research is needed to investigate the extent of linguistic development

through the use of language learning apps, particularly in language components

where the available evidence is scarce and less apparent (i.e., productive vocabulary

and oral skills).

Significantly, very few studies have attempted to empirically compare the relative

effectiveness of app-based instruction vs. traditional, face-to-face classroom

instruction (Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky, et al., 2021). One of the first attempts was

Lord’s (2015) examination of beginning-level Spanish learners in traditional

face-to-face classes vs. using Rosetta Stone to learn English over a 16-week

instruction period. She found no differences between the two groups’ performance

on standardized L2-English tests, despite the discovery that the app-based group

dedicated substantially less time in the program. Yet, she noted that while both

groups had similar outcomes on the linguistic measures, the app-learning students

seemed to struggle more in conversation compared to those in classroom-based

instruction. It should be noted, however, that the study’s sample was very small (12

participants), and thus, the findings are tentative and should be interpreted with

caution. Rachels and Rockinson-Szapkiw (2018) investigated primary school

students learning L2 Spanish through either Duolingo or traditional classroom

instruction, and found that Duolingo was equally effective than traditional lessons in

developing grammatical and vocabulary knowledge when dedicating the same

amount of time studying (40-mins a week during 12 weeks). This led the authors to

conclude that Duolingo may be an alternative option for L2 instruction (p. 84). More

recently, Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky, et al. (2021) showed that Duolingo learners of two

different L2s (Spanish and French) attained comparable reading and listening skills

to university students studying the L2 for 4 semesters, while spending only half the

amount of time on the program.

As can be seen, the findings from prior studies on the effectiveness of app-based vs.

classroom-based instruction are inconclusive. Some conclude that apps are more

effective than traditional face-to-face language courses based on the fewer hours of

study required to achieve similar outcomes (i.e., Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky, et al.,

2021; Vesselinov & Grego, 2012). Other research argues in favor of face-to-face

language instruction (despite finding similar language test outcomes) based on the

better ability of classroom-based learners to use the language for communication

(i.e., Lord, 2015). Other studies regard apps and face-to-face classroom courses as

equally effective given similar language learning gains (Rachels &

Rockinson-Szapkiw, 2018). The seemingly inconsistent findings across studies might

5

Research Report

be partially explained by their limitations. Some of the main ones include: a) lack of

pre-test data and control/comparison group (e.g., Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky, et al.,

2021; Loewen et al., 2019, 2020); b) lack of or minimal control of study time by

participants (e.g., Lord, 2015); c) small variability in learning environment and

samples, mainly covering learners at University level and in the US; and d) small

sample sizes, which present a threat to the validity of their findings – the present

study seeks to improve on these features. These limitations and the mixed findings

highlight the need for further research to offer additional clarity on the comparison of

app-based vs. classroom-based instruction in facilitating L2 proficiency development

(Sudina & Plonsky, 2023).

Motivation and Language Learning

The field of SLA has long established the role of individual differences in L2

development, but how learners’ individual differences affect MALL is still largely

unclear. Learner factors such as motivation or engagement with the course have

been found to be important predictors of language development by research

examining the effectiveness of apps (He & Loewen, 2022; Loewen et al., 2020) as

well as traditional classroom instruction (Saito et al., 2018). Learning a language can

be challenging and stressful, is time-consuming and requires perseverance to keep

studying and practicing (Shortt et al., 2023). Thus, without adequate motivation and

engagement with the language, students are less likely to succeed. As Dörnyei

(2019) explains, the two concepts are interlinked: L2 motivation refers to a student’s

potential for actively learning a language, whereas engagement is the behavioral

manifestation of motivation.

Regarding MALL, app-based learners have been found to struggle significantly with

motivation, engagement and persistence using apps long term, which in turn

influences their learning outcomes (García Botero et al., 2019; Loewen et al., 2019;

Vesselinov & Grego, 2012). For example, García Botero et al. (2019) found that

university students supplementing their language instruction with Duolingo did not

engage with the app and logged in 10 or fewer times in one year. Similarly, Loewen et

al. (2019) showed that only 22% of their participants achieved the goal of studying

the L2 using Duolingo for 34 hours in one semester, and reported that this general

lack of interaction and variation with apps’ features might have affected their

motivation and persistence in using the app.

Conversely, some scholars argue that apps’ typically engaging designs, attractive

interface and gamified features (i.e., game-based elements such as leaderboards,

experience points or reinforcement streaks) might make app learning more

motivating and engaging than traditional instruction for L2 learners, thus promoting

learning (Boudadi & Gutierrez-Colon, 2020; He & Loewen, 2022; Nami, 2020; James &

Mayer, 2019; Shortt et al., 2023). For example, James and Mayer (2019) examined

6

Research Report

college students learning L2-Italian at home using Duolingo versus learning it using

an online slideshow during 7 sessions, and found that, while the groups did not differ

on linguistic achievement, Duolingo learners reported the experience to be more

enjoyable, appealing and less difficult, as well as more willingness to continue

studying the language. In a recent systematic review on the effect of gamification in

language learning, Dehganzadeh and Dehganzadeh (2020) also discovered that most

studies showed an increase in student motivation and enhanced user engagement

and persistence in gamified environments, pointing to the motivational benefits of

MALL apps.

Given this mixed picture on apps’ potential to generate sustained engagement and

motivation, it is important to gain a better understanding of how language motivation

develops and compares across app-based and classroom-based instruction

(Loewen et al., 2019). It is possible that the prevailing gamified features of

app-based self-study and traditional classroom learning settings influence learners’

levels of motivation and engagement with the course differently, and research needs

to further explore this issue (He & Loewen, 2022).

Duolingo Course

Duolingo is one of the most dominant and influential MALL apps in the market, with

more than 300 million users (Shortt et al., 2023). For this reason, it has also attracted

the attention of scholars, being the most investigated MALL platform by SLA

researchers (Dehganzadeh & Dehganzadeh, 2020). The present study is specifically

concerned with the effectiveness of Duolingo’s most popular course: the English

course for Spanish speakers, with over 47 million learners

1

. To better situate the

study, this section provides an overview of the Duolingo English-from-Spanish course

structure at the time of data collection, and compares it generally to the classroom

course. The Duolingo course is aligned with the CEFR (Council of Europe, 2017), and

includes lessons from A1.0 level (targeted to real beginner/basic user) to B1 level

(intermediate/independent user). Participants in the current study were finishing the

A1 level content (section A1.2), which covers general functional and grammatical

topics, and were starting level A2 just before or shortly after the pretest. Based on

Duolingo data, it was estimated that learners would progress through only the A2

content during the 16-week instruction period. Lessons are built around

communicative topics such as family, food, and travel; each topic introduces some

grammar and cultural concepts, although with limited explanations, but the main

focus is teaching new words and sentence structures through various exercise types

(e.g., gap-filling, translations, listen and repeat). Typical exercises include translation,

multiple-choice word recognition questions and spelling. Like other MALL platforms,

Duolingo also possesses gamified elements, such as challenging tasks, reward

incentives, systematic levels, and user rankings based on achievement (Shortt et al.,

2023).

7

Research Report

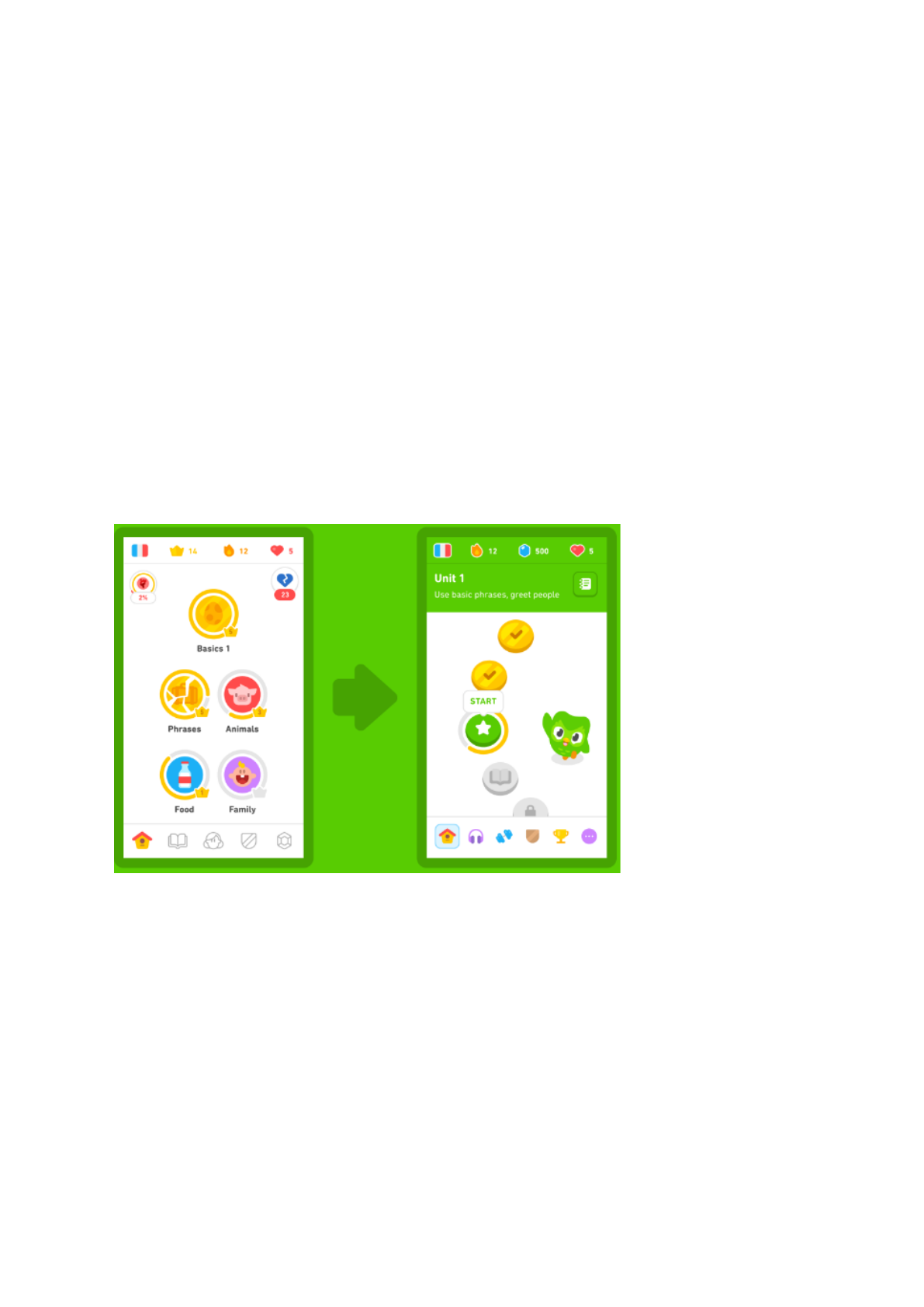

The current study uses the new Duolingo Version 2, launched in 2022. In the earlier

version, students navigated the platform autonomously and could choose not to

cover all the content on each theme (e.g., animals), because each theme included 5

levels of content but learners were only required to finish the first level to move down

the course. To control for the variation in individual learner behavior and time spent

in each section of the course found in the earlier version (Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky, et

al., 2021), the new Duolingo Version 2 requires all learners to progress through the

same path, going through the different difficulty levels in each section in a logical

and linear manner (Figure 1). This new version aligns more directly with traditional

classroom instruction, where the teacher typically follows a syllabus and learners are

exposed to the content in the same order and manner. Version 2 provides more

comparability between classroom and app-based learners in the present study.

Figure 1

Duolingo’s New Learning Path (Version 2)

Like the Duolingo course, the classroom course in the present study is also aligned

with the CEFR. Target learners were enrolled in a face-to-face A2-level English

course, and had completed the A1 level in the same mode of instruction. The

classroom syllabus is similar to Duolingo’s in that it follows a communicative

approach, covering familiar topics such as food, travel and family. However, they

differ in that the classroom syllabus has a greater focus on the use of the L2 and

social exchange, and the L1 was discouraged in the classroom. The gamification of

Duolingo’s course is also a main differential point with the classroom instruction.

8

Research Report

The Present Study

Expanding on previous MALL research, the current study follows a

quasi-experimental pretest-posttest design to compare Spanish speakers’ L2-English

proficiency and lexical development after studying Duolingo’s English course (i.e.,

treatment) and after receiving traditional face-to-face English instruction (i.e.,

control). It also evaluates sustained motivation and engagement levels across both

learner groups. To account for the differences in the study-time distribution of

app-based and classroom-based settings (e.g., Lord, 2015), the current study

controls for the length of instruction (fixed to 16 weeks for both groups) as well as

the amount of time spent in the language course (3-4 hours per week) (Jiang,

Rollinson, Plonsky, et al., 2021; Lin & Lin, 2019).

The following research questions are addressed:

RQ1. How effective is Duolingo in developing the general L2 proficiency and

receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge of L1-Spanish learners of

English at a basic proficiency level? How does it compare to the L2-English

development of similar learners receiving face-to-face classroom instruction?

RQ2. How do learner-related factors such as total time spent studying the

course and level of motivation associate with the L2 proficiency and lexical

development of learners in the Duolingo and classroom-based courses?

Following Sudina and Plonsky’s (2023) approach, the current study can be

categorized as a “natural experiment”. This is a type of observational study which

describes “any event not under the control of a researcher that divides a population

into exposed and unexposed groups” (Craig et al, 2017, p.2). In natural experiments,

researchers have less control over the intervention, and use the naturally occurring

variation in exposure to examine the impact of a particular event on the target

outcome. This approach addresses concerns raised on the ecological validity of

findings derived from L2 instruction studies conducted in lab conditions, and their

replicability in less controlled instructional settings (Rogers & Cheung, 2021). In this

sense, natural experiments are considered to have higher ecological validity than

rigidly controlled experiments (Sudina & Plonsky, 2023), and seem particularly

appropriate for studies comparing the effectiveness of app-based and

classroom-based learning, where researcher control is limited (Loewen et al., 2020).

Thus, the present study could be considered a natural experiment insofar as: a) it

follows a pretest-posttest design; b) has a clear intervention that is not rigidly

controlled, as the aim is to examine the effect of input mode in authentic

environments, and c) lacks a random assignment to intervention (i.e., participants

9

Research Report

had already independently enrolled in the target mode of instruction) (Craig et al.,

2017, p.19).

Methodology

Participants

The participants in this study comprised adult Spanish speakers learning L2 English

at a basic proficiency level (A2 CEFR) under two instruction modes: Duolingo or

traditional, face-to-face classroom instruction. The treatment participants were

invited through Duolingo when they were in the latest session of level A1.2 (aligned

with the CEFR) and about to begin level A2.1 (Units 45-46) of the Duolingo English

from Spanish course. In order to qualify to participate in the study, participants had

to be at least 18 years old, reside in English-as-a-foreign-language countries/regions

in Europe (to control for learners’ exposure to the target language outside the

course), self-assess as having low/basic English proficiency, self-report using

Duolingo as the only English language learning tool (i.e., not taking classes or using

other apps during the time of the study), and commit to studying English on Duolingo

for approximately 30 minutes a day for the duration of the study (16 weeks), with a

weekly study target of 3-4 hours. Participants received 100 euros in compensation

for the completion of the study.

The control participants were recruited in the Escuela Oficial de Idiomas (Official

Language School) in Spain. It is a public institution that offers extra-curricular

language courses to the general public (adults over the age of 16). It is regulated and

subsidized by the Spanish Ministry of Education, offering an official language

certificate and making it relatively affordable compared to private language schools.

Same-level courses are typically offered in the morning and evening to cater to as

many people as possible regardless of their professional, educational or personal

commitments. These features result in a diverse student population in terms of age,

profession, or socioeconomic status, who want to improve their English skills for

various reasons (from enhancing their CV/employability to keeping active after

retirement). In this school, the curriculum is aligned to CEFR and approved nationally

by language education authorities. They were adult learners enrolled to begin the

A2-level course, which involves 4 hours of face-to-face instruction per week. To

participate, they had to report only receiving traditional face-to-face classroom

instruction (i.e., not being engaged in app-based English learning at the time of the

study), and commit to regularly attending the English lessons for the duration of the

study. In exchange for their collaboration, a contribution of 700 euros was made to

the institution for purchasing English learning materials (e.g., books).

After initial screening to ensure they met the selection criteria, interested

participants were invited to the pretest (see Procedure). A total of 544 participants

(188 Classroom learners and 356 Duolingo learners) completed the pretesting stage.

10

Research Report

However, 207 participants (72 classroom and 135 Duolingo learners) dropped out

during the study period (i.e., ceased consistently attending the lessons [n=58] or

using the app [n=132]) and/or did not complete the posttest.

The final participant pool of the study were 337 adult L1-Spanish learners of L2

English beginning an A2 level course. They were divided into a treatment group, who

studied English using Duolingo (k = 221) and a control group, who received

traditional classroom English instruction (k = 116). The two groups were matched in

Age (U = 12570.0, z = -.292, p = .770). All participants lived in Spain, except for 4

Duolingo students that lived in Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Serbia. Table 1

presents a comprehensive picture of participants’ demographic and language-related

features by group.

Table 1

Participant Characteristics

Classroom

(k=116)

Duolingo

(k=221)

Characteristic

k

%

k

%

Age

Mean

45.20

45.5

SD

16.79

11.93

Range

18-79

18-71

Gender

Male

38

32.8

104

47.1

Female

77

66.4

117

52.9

Other

1

.9

Nationality

Spanish

93

80.2

202

91.4

Latino-American (Venezuelan, Peruvian,

Argentinian, Colombian)

23

19.8

19

8.6

Reasons for learning English

For travel

87

75

128

57.9

For education

29

25

27

12.2

For job-related purposes

52

44.8

104

47.1

For fun/leisure

73

62.9

137

62

For memory/brain acuteness

51

44

64

29

For social purposes

39

33.6

45

20.4

As a challenge

44

37.9

69

31.2

Other

Other languages spoken

No

76

65.5

135

61.1

11

Research Report

Yes

40

34.5

86

38.9

Education

Primary

2

1.7

2

.9

Secondary

14

12.1

6

2.7

A-levels

19

16.4

22

10

Vocational

28

24.2

44

19.9

BA

35

30.2

114

51.7

MA

13

11.2

28

12.7

PhD

4

3.4

3

1.4

Prefer not to say

1

.9

2

.9

Studied English before current instruction

No

22

19

45

20.4

Yes

94

81

176

79.6

Years studying

Mean

6.27

6.53

SD

4.97

4.31

Range

0-20

1-20

Spent time abroad in English-speaking country

No

110

94.8

213

96.4

Yes

6

5.2

8

3.6

Months abroad

Mean

7.67

12.88

SD

8.64

14.68

Range

1-24

1-36

Learning difficulty

No

110

94.8

216

97.7

Yes

6

5.2

5

2.3

Instruments

In order to establish generalizations on linguistic development across studies,

standardized rather than researcher-developed measures of language ability are

preferred (Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky, et al., 2021; Rachels & Rockinson-Szapkiw,

2018). Thus, this study employed standardized tests of English proficiency and

vocabulary knowledge.

Oxford Placement Test (OPT)

The OPT (Allen, 2004) is a standardized measure of overall L2-English ability. It

comprises two sections: 1) Listening, which assesses students' general listening

ability by choosing correct word heard in short sentences; and 2) Grammar, assesses

students’ grammatical and lexical knowledge in context via items that require

reading short sentences and choosing right answer. These multiple-choice tasks are

12

Research Report

similar to the exercises that learners of lower proficiency levels are familiar with

(García Botero et al., 2019). The test takes approximately 60 minutes to complete

(~13 mins for the Listening part, and 50 mins for the Grammar part), and each

section is scored over 100 points (1-0 per item) to produce a total aggregate score

out of 200. The test scores match the CEFR proficiency levels from pre-A1 to C2, and

are fine-grained in that they distinguish between beginner and minimal users at the

pre-A1 CEFR proficiency, making it ideal for the participants in the current study. The

test was validated with multilevel samples of students from more than 40

nationalities over 5 years, and the results calibrated onto the CEFR (Allen, 2004).

Independent investigations also report its reliability as a proficiency test (α=.809,

Wistner et al., 2009). Thus, it is considered a reliable instrument to examine

L2-English proficiency (e.g., Borràs & Llanes, 2020).

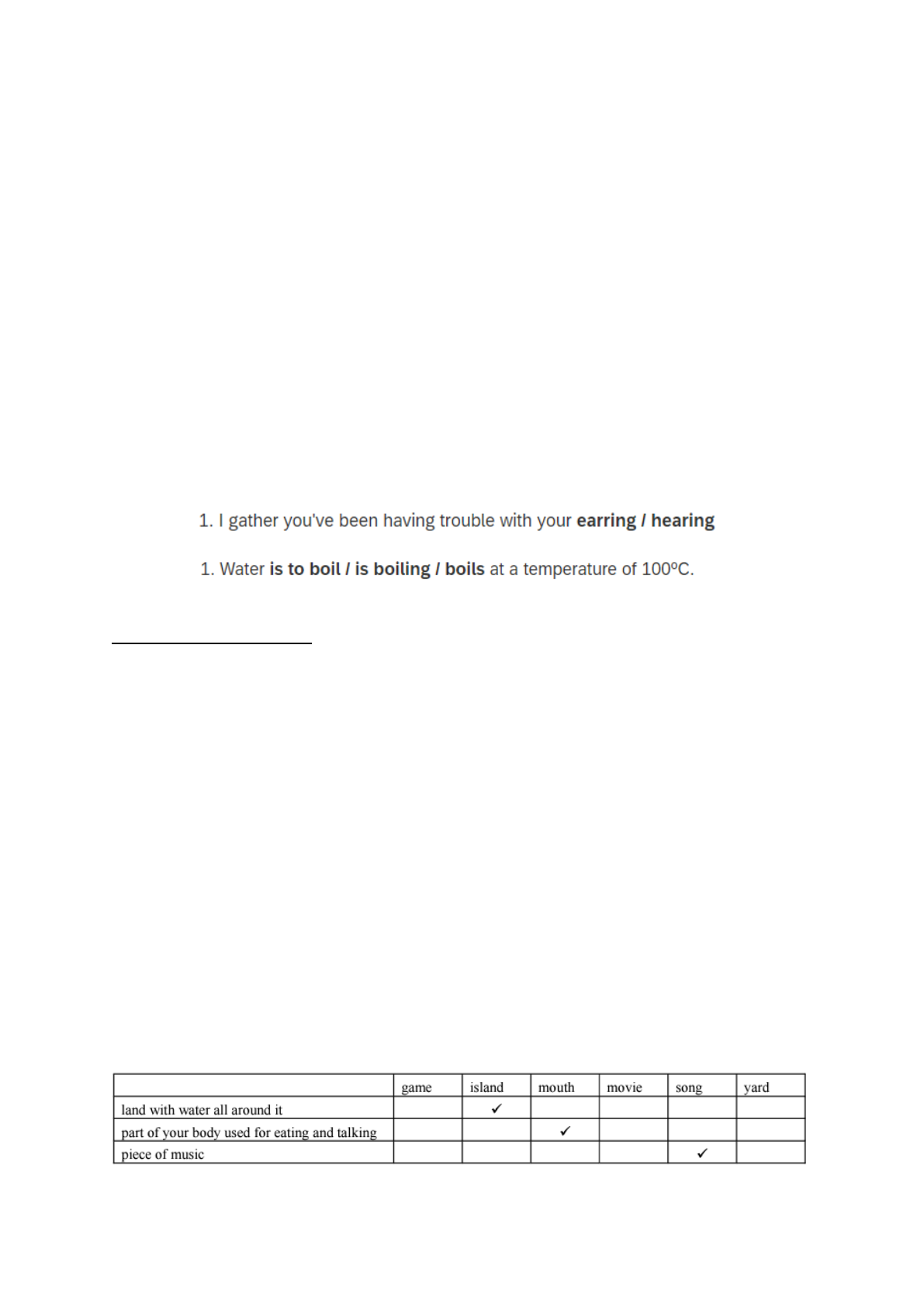

Figure 2

OPT Sample Items (listening and grammar respectively)

Vocabulary Levels Tests

Two validated non-timed standardized measures of vocabulary knowledge were

employed to assess learners’ receptive and productive lexical development over the

learning period. The Updated Vocabulary Levels Test (uVLT; Webb et al., 2017)

assesses receptive vocabulary knowledge (meaning recognition) of the most

frequent 5,000 words (1,000-5,000 frequency levels), making it ideal for lower-level

English learners. It takes the form of a word-matching task with extra options, asking

test takers to choose the right meanings (L2 definitions) corresponding to target

items. This format minimizes the chances of guessing as compared to a

multiple-choice task (Kremmel, 2020). The test comprises 30 items representing

each of the five frequency levels. Given participants’ low-proficiency, only sections

1,000-3,000 of the uVLT were administered, comprising 90 items in total (30 per

section) scored dichotomously. The maximum score for these three sections of the

test is therefore 90.

Figure 3

uVLT Sample Items

13

Research Report

The Productive Vocabulary Levels Test (PVLT; Laufer & Nation, 1999) measures

controlled productive knowledge (ability to recall the L2 forms) of the most frequent

2,000, 3,000, 5,000 and 10,000 words, plus academic vocabulary (each in a different

section). Each of the five sections includes 18 items. The task requires learners to

fill-in a gapped English sentence given the first few letters of the target word, and

contextual sentences were carefully created so that target words would not be easily

inferred. Considering the complexity of this test and the lower-proficiency

participants in the present study, only the 2,000 and 3,000 sections of the PVLT were

administered (36 items in total). Elicited responses were scored dichotomously as

correct or incorrect, but minor errors including misspellings (e.g., apartament for

apartment) or grammatical infelicities (e.g., *this skirts) were accepted as correct

responses for these learners as long as the original word identity remained easily

inferable. Thus, the maximum possible score in this test was 36.

Figure 4

PVLT Sample Item

Since research has reported significant improvements in the outcomes of the uVLT

(Borràs & Llanes, 2020) and the PVLT (Nadarajan, 2009) after relatively short

treatments (from 3 weeks to 1 semester), these tests are deemed appropriate for the

current study’s purpose of assessing incremental vocabulary gains over a semester.

In addition, tapping into two different levels of sensitivity (receptive and productive

knowledge) increases the likelihood of detecting small lexical improvements

(Kremmel, 2020) and offers more nuanced insights on learners’ general vocabulary

development.

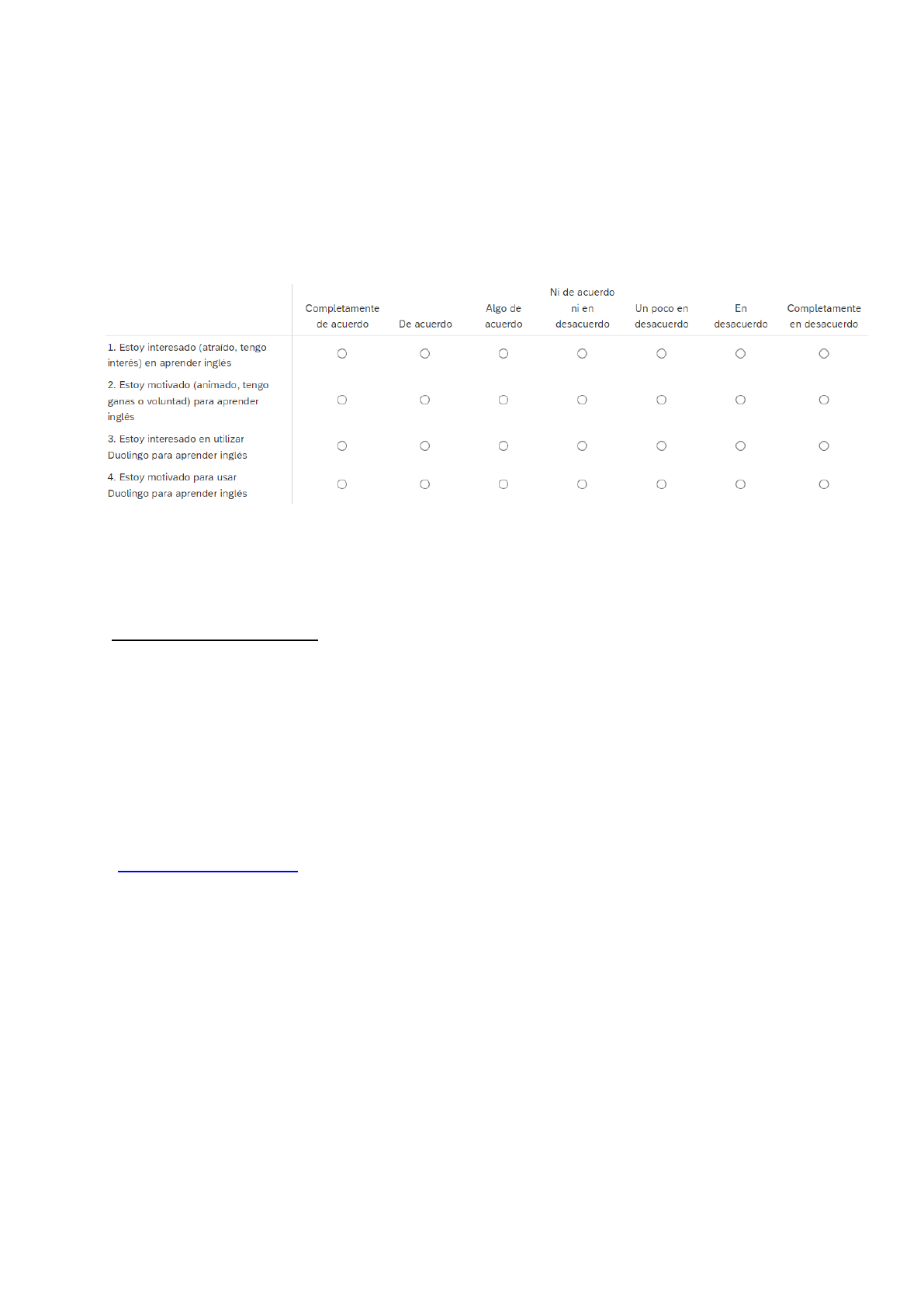

Background and Motivation Questionnaires

This background portion of the questionnaire was designed following similar

instruments in prior language learning app research (i.e., Loewen et al. 2020 and

Jiang et al., 2021). It included questions related to participants’ linguistic

background, self-assessed English proficiency, previous experience learning English

(in classroom settings as well as with apps), interest in and reasons for learning the

target language. To examine the influence of motivation and engagement in

Duolingo and classroom-instruction learners, the questionnaire also featured

questions targeting the level of engagement with the lessons and their motivation for

learning the language and for the respective course (Duolingo vs. classroom) prior to

starting the course (see Appendix A) and again in the posttest (see Appendix B).

Finally, additional questions about time spent per week using the target language

outside the class or Duolingo, perceptions on learning progress, and level of overall

14

Research Report

enjoyment with the course were included in the post-test questionnaire. Most

questions followed a 7-point Likert scale, making the questionnaire quicker to

answer.

Figure 5

Questionnaire Sample Item

Procedure

The study involved three phases:

Screening and Pretesting

Interested participants completed a screening form to ensure compliance with the

selection criteria (see Participants). After providing their informed consent to

participate in the research, the pretesting session was scheduled with the

participants. Pretesting required participants to take (in the stated order) the

background and motivation questionnaire, proficiency test (OPT) and vocabulary

tests (first PVLT and then uVLT), to control for learners’ prior English knowledge and

motivation level before the learning period. Duolingo learners completed the tests

individually online on Qualtrics, but proctored via a remote monitoring system

(https://hubstaff.com/) which tracks learners’ activity during testing by taking

screenshots, and thus can achieve the aim of monitoring performance in an

unobtrusive way. This remote monitoring ensures the validity of the test scores.

Duolingo participants were informed prior to taking part that the testing sessions

required completion on a computer with good internet access and sound system.

The classroom-based participants completed the tests in person in their classroom

group under the supervision of the researcher. While practical constraints did not

allow for classroom-based participants to be tested online as Duolingo participants,

this provides greater ecological validity to the study design as the groups are

assessed in the same manner in which they receive instruction, aligning with the

requirements of a natural experiment. All instructions were given in participants’ L1

(Spanish). The pretesting stage took approximately 1.5 hours to complete, and the

researchers controlled that participants did not spend too much time in each test by

15

Research Report

limiting completion time according to test guidelines (i.e., approximately 60 minutes

for the OPT) and piloting information (approximately 15 minutes for the uVLT and

PVLT). Participants were informed of these times prior to completion of each task.

Learning Period

Following prior app-based studies (Loewen et al., 2019, 2020; Lord, 2015; Rachels &

Rockinson-Szapkiw, 2018), participants engaged in their respective instruction

program (Duolingo or classroom) over the course of an academic semester (fixed

length of 16 weeks between pretesting and post-testing). To ensure that the amount

of time spent in language learning was comparable between the treatment and

control groups, Duolingo participants were instructed to study approximately 30

minutes per day, with a weekly study target of 3-4 hours. This was measured via

self-reported engagement questions. Duolingo data analytics were also collected,

but not employed in analyses because they were not reliably recorded due to

technical issues. No cut-off minimum number of hours per week was applied, but the

analysis shows that 73.8% of Duolingo learners studied at least 2-3h per week, and

53.7% did more than 3-4h per week. Previous research findings indicate that

app-based learners tend to revisit known material rather than advance through the

course content (Jiang et al., 2021). Thus, Duolingo participants in this study were

instructed to progress along the course as much as they could. Classroom

participants were asked to attend most of the lessons and follow the teachers’ study

plans (~64 hours of instruction in total). Teachers confirmed that the classroom

participants included in the analysis attended regularly (>80%). During the 16-week

study period, the researchers maintained frequent communications with the

Duolingo learners, while allowing for independent study, and with the classroom

teachers. On week 14, a reminder was sent that the posttest was due in week 16.

Post-testing

After the learning stage, participants completed the same tasks and questionnaire

as in the pretest stage –questionnaire, proficiency test, vocabulary tests– in the

same format and order. Additional post-testing questions were added to the

questionnaire asking participants whether they made use of any other courses or

programs than the target ones during the duration of the study, to reflect on their

learning experience and self-assess their English progress. Post-testing was

completed in approximately 1.5 hours. This stage concluded with the conferral of

participant compensation.

Analyses

A series of linear regression analyses were run to examine how mode of instruction

(Duolingo vs. classroom) and learner factors (e.g., total time spent learning English

and motivation) influence learners’ L2 proficiency and lexical development in English

(RQs 1-2). Other potentially influencing factors were controlled for by adding them as

16

Research Report

covariate in the regression analyses (e.g., pretest scores). Separate models were fit

for the pretest and posttest scores for each of the test outcomes (uVLT, PVLT and

OPT). The regression models were run using the lm (Hothorn, 2002) package in R.

Results

L2 proficiency and Lexical Development

Table 2 shows that, overall, the participants’ mean scores across all language tests

were higher in the Duolingo group than the Classroom group, both at pretest and

posttest. However, there was an exception with the OPT Listening task, in which

classroom learners outperformed Duolingo learners prior to and after the study

period. This might be explained by the classroom learners’ higher viewing and

listening exposure to English prior to and after the treatment (see Appendix C, Table

1).

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics for Language Test Scores (N= 337)

Classroom

(k=116)

Duolingo

(k=221)

Test

M(%)

SD

Range

M(%)

SD

Range

OPT Total pretest

Pretest

49.3

8.1

28.5-71

54.6

9.9

13-74.5

Posttest

53

9

14.5-77

58.5

8.9

32.5-77.5

OPT Listening

Pretest

63.8

8.2

42-82

63

12.2

10-85

Posttest

67.2

6.6

47-87

65

10.4

30-84

OPT Grammar

Pretest

34.8

11

8-66

46.3

11.6

12-75

Posttest

39.7

12.3

8-74

52.1

10.8

27-86

uVLT

Pretest

54.7

18.4

8.9-92.2

72.6

15.1

34.4-100

Posttest

63.2

17.5

17.8-93.3

80.2

13.6

40-100

PVLT

Pretest

23.6

11.5

0-61

33.2

13.5

5.6-83.3

Posttest

31.1

10.6

11.1-58.3

39.9

15.5

8.3-88.9

Note. OPT = Oxford Placement Test; uVLT = Updated Vocabulary Levels Test; PVLT = Productive VLT

17

Research Report

To estimate the increase in linguistic knowledge across the two testing times, a

series of Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were conducted for each group independently.

The tests revealed statistically significant gains between the pretest and posttest

scores across all linguistic measures for both the classroom and Duolingo groups (p

<.05, see Table 3 for exact p and d values). This indicates that participants’ general

L2 proficiency and vocabulary knowledge improved significantly during the learning

period, although the effect size (calculated using Cliff’s delta) was small (<.40,

Plonsky & Oswald, 2014).

Table 3

Significance and Effect Size for the Paired Samples (pre-post) Test Contrasts

OPT Total

uVLT

PVLT

Group

p

d

p

d

p

d

Classroom

8.918e-11

0.30

4.015e-14

0.31

6.416e-12

0.18

Duolingo

6.154e-14

0.33

< 2.2e-16

0.46

< 2.2e-16

0.23

In both groups, learning gains were more evident in the two vocabulary measures

than the OPT measure. For the classroom learners, the difference in uVLT scores

between pretest and posttest was 8.5% (63.2-54.7) and for the PVLT 7.5%

(31.1-26.3). In raw figures, this means a learning gain of 7.7 words in the uVLT and

2.7 words in the PVLT standardized measures. Since in the uVLT test 30 items

represent 1,000 words in each frequency band, this translates to an average gain of

256.7 real words at the receptive level of mastery (7.7*33.3). In the PVLT, each item

in the test represents approximately 55.5 words in a frequency band, meaning that

classroom learners gained approximately 150 real words on average (2.7*55.5) at

the productive level of mastery.

The picture is similar for the Duolingo learners, with a difference of 7.6% in the uVLT

(80.2-72.6) and 6.7% in the PVLT (39.9-33.2) from pretest to posttest. In raw figures,

this is an average gain of 7 words in the uVLT task and 2 in the PVLT task, translating

into 233.3 real words gained at receptive knowledge and 111.1 at productive level.

L2 Motivation and Engagement

As shown in Table 4, participants’ level of motivation and interest in the language

and the target program prior and after the instruction period was very high in both

groups. However, a decline in motivation and interest was found for both groups

after the study period.

18

Research Report

Table 4

Interest and Motivation prior and after Instruction

Classroom

(k=116)

Duolingo

(k=221)

Characteristic

M

SD

Range

M

SD

Range

Interested in English

pretest

6.69

.55

4-7

6.81

.51

2-7

posttest

6.65

.59

4-7

6.75

.49

5-7

Motivated in English

pretest

6.61

.68

4-7

6.62

.66

2-7

posttest

6.53

.71

4-7

6.47

.84

2-7

Interested in the lessons

pretest

6.72

.49

5-7

6.71

.62

1-7

posttest

6.54

.73

4-7

6.60

.62

4-7

Motivated in the lessons

pretest

6.69

.57

4-7

6.70

.60

1-7

posttest

6.43

.91

2-7

6.57

.75

2-7

Note. Rated on a 1-7 Likert-Scale (1= Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree).

To estimate changes in motivation from pretest to posttest, a two-way ANOVA with

repeated measures was run, checking the effects of sustained motivation at posttest

(within-subject), group (between-subject), and their interaction on the motivation

pretest scores. The results showed a significant main effect of posttest motivation in

English within-subjects (p < 2e-16). However, no significant main effect of group was

found (p = 0.486). The interaction effect between posttest motivation in English and

group was also not significant (p = 0.149). The effect size, eta squared (η²), was

0.26, indicating a moderate effect (Plonsky & Oswald, 2014). Overall, this suggests

that, on average, participants’ motivation significantly changed from pretest to

posttest, showing decreased levels of motivation after the study period, but this

occurred at the individual level (within each participant) rather than at the group

level.

A series of t-tests were conducted to compare the interest and motivation in the

language between the two groups prior and after the intervention. A Welch Two

Sample t-test (used to account for the different sample size between the two groups)

showed no significant differences between the Classroom and Duolingo participants

in their interest and motivation in learning the language prior to the study period (p

=0.060 and 0.965, respectively). However, when level of motivation in the posttest

(i.e., sustained motivation) was compared, a Wilcoxon rank sum test indicated a

significant difference between the groups (p =2.458e-08). The median score for the

Classroom group was 5 (Q1 = 4, Q3 = 6), and for the Duolingo group it was 6 (Q1 = 5,

Q3 = 7), indicating that the Duolingo learners reported being more motivated on

19

Research Report

average in the posttest than the Classroom learners, with a medium-size effect (r =

0.49). Thus, these analyses show that both groups had higher motivation levels at

the pretest, but the Duolingo learners in general seemed to report slightly higher

levels of motivation at posttest than the classroom learners.

Finally, in order to explore the influence of engagement with the course, students

were asked to report the average time they spent studying English per week during

the study period. Table 5 shows that classroom learners reported spending an

average of 4-5 hours per week studying English (including lesson time), while

Duolingo learners spent on average about 2.5 hours studying English weekly. A

Welch Two-Sample t-test showed a statistically significant difference between the

groups (p <.001), indicating that Classroom learners spent significantly more time

studying English than Duolingo learners. This suggests that, on average, the

Duolingo group did not reach the weekly study goal of 3-4 hours. However, a

frequency analysis revealed that 53.7% of Duolingo learners reported studying the

English course 3 or more hours per week, meaning that most of them met the study

target.

Table 5

Average Time Studying English per Week in the Target Mode

Classroom

(k=116)

Duolingo

(k=221)

Characteristic

M

SD

Range

M

SD

Range

Average time studying English per week

a

6.17

1.6

3-8

4.37

1.4

1-6

Note:

a

Values represent: 1= 1-30 mins, 2= 31-60 mins, 3= 1-2h, 4= 2-3h, 5= 3-4h, 6= 4-5h, 7= 5-6 h,

8=6+ h

Effect of Mode of Instruction and Learner Factors on L2 Development

To answer RQs 1 and 2, learners’ language gains over time were examined in relation

to their target mode of instruction and self-reported motivation and engagement

level in the course. General linear models were conducted with Mode of Instruction

(i.e., Duolingo vs. Classroom) as the main independent variable and the scores on

the language tests (OPT, uVLT and PVLT) as the dependent variables. Separate

models were run for each dependent variable. Motivation and time spent studying

English (i.e., engagement) were also modeled as predictors to isolate and better

understand the effect of mode of instruction on any gains.

First, the two groups were compared statistically to check for any differences in their

L2 knowledge prior to the treatment. Mann-Whitney U pairwise comparisons

between the pretest scores of the two groups with post-hoc analyses (Bonferroni

adjustment p =.025) showed significant differences across all linguistic measures,

20

Research Report

with an advantage of the Duolingo group (p <.001). Although both groups were

starting an A2-level course, it is possible that the Duolingo students’ level was higher

than estimated (OPT Total raw mean score was 109.3, which corresponds to an

A2-level in the CEFR [105-119 OPT scores = A2 CEFR]). Thus, the Duolingo learners

overall might have been in the beginning stages of the A2-level when completing the

pretest, as compared to the classroom learners who had just achieved the A1 level

(OPT Total raw mean scores was 98.6 [90-104 = A1]). This aligns with Jiang and

Pajak’s (2022) finding that their Duolingo learners at the end of the A2 Duolingo

English course for Spanish speakers aligned with an Intermediate level on the ACTFL

scale.

To control for the difference in prior knowledge between groups, the pretest scores

for each dependent variable was included as a covariate in their respective posttest

model. Preliminary ANCOVA tests were first conducted using only the main predictor

Mode of Instruction and the relevant pretest scores as covariates to control for the

differences observed at pretest (see Appendix C). Then, linear regression analyses

were computed to help us better understand how each variable contributes to the

variation in the posttest scores and provide more detailed insights into our data. The

results are presented below by dependent variable.

OPT

A linear regression model was conducted to examine the effect of the target

predictors (i.e., Mode of Instruction, Engagement [time spent studying per week] and

Motivation) on the OPT Total posttest scores. The pretest score was included as a

covariate to control for initial differences. The results showed a significant effect of

Mode of Instruction (p <.001), with the coefficient (3.25) indicating that participants

in the Duolingo group had a higher estimated OPT posttest score compared to the

Classroom group. This suggests that, after statistically controlling for initial

differences in the OPT Total scores at the start of the course, the learners in the

Duolingo group outperformed the Classroom group in their general L2 proficiency at

the end of the study period. The baseline scores (OPT pretest) and self-reported

interest in English learning (Interested English) were also found to be statistically

significant predictors of the OPT posttest scores, but time studying per week did not

appear to be significant. This suggests an influence of interest but not engagement

on the OPT scores (see Table 6).

Table 6

OPT Total Posttest Model

Predictor

Estimate

SE

t value

Pr (>|z|)

Intercept

27.55001

10.68310

2.579

0.01*

OPT Total pretest

0.68732

0.03704

18.556

<.001***

Group

3.24871

1.60978

2.018

0.04*

21

Research Report

Time studying per week

-0.03905

0.44840

-0.087

0.93

Interested in English

3.91826

1.84460

2.124

0.03*

Motivated in English

-2.78241

1.58261

-1.758

0.08

Interested in the lessons

1.06851

2.60555

0.410

0.68

Motivated in the lessons

-1.09533

2.51819

-0.435

0.66

Model Adjusted R-squared

0.55

Linear regression models were also fit for each section of the OPT to explore the

relationship between the Grammar and Listening posttest scores and the target

predictors. The pretests scores were included as covariates to control for initial

differences. The results (see Table 7) showed that Mode of Instruction (p <.001) and

Motivation in English (p <.01) were significant predictors of OPT Grammar posttest

scores when controlling for the pretest scores. This suggests that Duolingo learners

displayed a significantly greater improvement in grammar knowledge than the

classroom students after the 16-week study period.

Table 7

OPT Grammar Posttest Model

Predictor

Estimate

SE

t value

Pr (>|z|)

Intercept

11.39841

6.05196

1.883

0.06.

OPT Grammar pretest

0.73809

0.03587

20.579

<.001***

Group

3.64244

1.01250

3.597

<.001***

Time studying per week

-0.01732

0.26501

-0.065

0.95

Interested in English

2.40508

1.08986

2.207

0.03*

Motivated in English

-2.95534

0.94412

-3.130

.002**

Interested in the lessons

1.94174

1.57181

1.235

0.22

Motivated in the lessons

-1.57028

1.50515

-1.043

0.30

Model Adjusted R-squared

0.66

For the Listening posttest scores (Table 8), the results showed that Listening pretest

scores were a significant predictor of improvement in listening, indicating that

participants who scored higher at pretest tended to perform better in the posttest.

The model also showed a significant difference in listening scores at posttest (p =

0.05) between the Classroom group and the Duolingo group. Importantly, however,

as opposed to the previous models, the advantage in this case was for the

Classroom group. This suggests that classroom learners exhibited a greater

improvement in their Listening skills when compared to the Duolingo learners.

22

Research Report

Table 8

OPT Listening Posttest Model

Predictor

Estimate

SE

t value

Pr (>|z|)

Intercept

30.87740

6.83350

4.519

<.001***

OPT Listening pretest

0.45019

0.03913

11.505

<.001***

Group

-1.85377

0.98190

-1.888

0.05*

Time studying per week

0.18606

0.28208

0.660

0.51

Interested in English

1.69864

1.15959

1.465

0.14

Motivated in English

-0.54888

0.99536

-0.551

0.58

Interested in the lessons

0.34264

1.63924

0.209

0.83

Motivated in the lessons

-0.23880

1.58579

-0.151

0.88

Model Adjusted R-squared

0.30

uVLT

The linear regression analysis for the uVLT shows that Mode of Instruction was a

significant predictor of learning in the posttest when controlling for pretest scores,

with an advantage for the Duolingo group (p =.001). Moreover, a significant effect of

the uVLT pretest scores was found, indicating that higher receptive vocabulary

pretest scores are associated with higher posttest scores, regardless of the group

(Table 9).

Table 9

uVLT Posttest Model

Predictor

Estimate

SE

t value

Pr (>|z|)

Intercept

14.36422

7.38224

1.946

0.05*

uVLT pretest

0.73731

0.03105

23.746

<.001***

Group

4.16426

1.27380

3.269

0.001**

Time studying per week

0.23758

0.32902

0.722

0.47

Interested in English

-0.32990

1.35565

-0.243

0.81

Motivated in English

0.48811

1.16303

0.420

0.68

Interested in the lessons

2.20469

1.90978

1.154

0.25

Motivated in the lessons

-1.92205

1.85138

-1.038

0.30

Model Adjusted R-squared

0.71

PVLT

Linear regression analyses fitted to predict PVLT posttest scores while controlling for

the target predictor variables showed that only Mode of Instruction (p <.001) and

prior Motivation in English (p <.001) had significant effects on the PVLT posttest

scores. However, the model showed a very small adjusted R-squared (0.1016),

indicating that it could explain only a relatively small proportion of the variance.

23

Research Report

Given the relationship between receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge,

where development of receptive knowledge precedes that of productive knowledge

(González-Fernández & Schmitt, 2020), the uVLT pretest scores were also included

as a covariate in this model. The new model fitted the data better, and found that

only Motivation in English and the PVLT (p<.001) and uVLT (p<.05) pretest scores

were significant predictors of PVLT posttest scores (Table 10). This suggests that

when accounting for prior vocabulary knowledge, the effect of mode of instruction

disappeared in the learning of productive vocabulary.

Table 10

PVLT Posttest Model

Predictor

Estimate

SE

t value

Pr (>|z|)

Intercept

10.63522

8.05631

1.320

0.19

PVLT pretest

0.63633

0.06535

9.737

<.001***

Group

0.98457

1.39053

0.708

0.48

Time studying per week

0.22917

0.36019

0.636

0.53

uVLT pretest

0.11787

0.05085

2.318

0.02*

Interested in English

-0.20992

1.48677

-0.141

0.89

Motivated in English

-2.60732

1.28310

-2.032

0.04*

Interested in the lessons

2.13170

2.08418

1.023

0.31

Motivated in the lessons

0.15412

2.02151

0.076

0.94

Model Adjusted R-squared

0.53

Discussion

The present study set out to compare the motivation level and gains in L2 proficiency

and vocabulary knowledge of classroom and Duolingo L1-Spanish beginner learners

of English. It builds on prior research by controlling for length of program and study

time, while allowing for learner autonomy to maximize ecological validity. The

findings and implications are discussed below.

RQ1: Effectiveness of Duolingo for L2 Development

There are two main findings connected to this RQ. First, the scores across the

standardized linguistic measures were significantly higher at posttest compared to

pretest for both groups. This shows that both modes of instruction (i.e.,

classroom-based vs. app-based) led to significant improvement in L2 proficiency and

lexical knowledge after 16 weeks of studying. This finding corroborates the notion

that low-proficiency L2 learners benefit from deliberate instruction in the L2,

regardless of type (Lord, 2015; Rachels & Rockinson-Szapkiw, 2018). Although the

gains seem modest, the fact that they are evident in standardized measures is

24

Research Report

significant (Lord, 2015; Rachels & Rockinson-Szapkiw, 2018). Among all the linguistic

tasks, students showed a greater average improvement on vocabulary knowledge,

both at the receptive and productive levels of mastery. This corroborates prior claims

that MALL apps are effective for vocabulary development (Lin & Lin, 2019). As

shown by much previous research (e.g., Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky, et al., 2021; Lin &

Lin; 2019; González-Fernández & Schmitt, 2020), improvement was greater in

receptive vocabulary than productive vocabulary. Although expected, the current

study shows that this applies under app-based instruction as well as

classroom-based instruction. In a previous study, Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky, et al.,

(2021) found that their productive vocabulary knowledge task reported the weakest

performance among all their measures, suggesting that apps such as Duolingo

might be more facilitative in developing receptive than productive vocabulary

knowledge. The current findings demonstrate that Duolingo’s course focus on lexis

(Shortt et al., 2023) is effective at the receptive and productive level.

Secondly, after accounting for pretest differences in L2 knowledge between the

groups, the results of regressions analyses showed that there was a significant main

effect of Mode of Instruction on posttest scores across all linguistic measures,

except the PVLT. The models showed a general advantage of Duolingo learners over

classroom learners on the scores in the OPT Total, OPT grammar, and uVLT after the

16-week learning period. However, for the OPT Listening task the classroom learners

were found to significantly outperform Duolingo students after the study period. This

finding corroborates previous claims that type of instruction significantly influences

students’ L2 development (Norris & Ortega, 2000). Importantly, it points to the

positive effect of using Duolingo compared to traditional classroom instruction for

the acquisition of overall L2 proficiency, receptive grammar knowledge and receptive

vocabulary knowledge. This finding is in line with much prior research which shows a

beneficial impact of the use of apps, and specifically Duolingo, on various language

competencies (see Shortt et al.’ 2023 systematic review). The results also

demonstrate that when the study time between app-based and classroom-based

learners is more comparable (unlike in studies such as Lord 2015), app-based

instruction can outperform classroom instruction on certain linguistic aspects.

The findings also indicate that classroom instruction was more beneficial for the

development of listening skills than MALL instruction. This aligns with prior

statements that classroom instruction may provide more opportunities to interact via

spoken language and thus for developing oral skills. For example, Lord (2015) noted

that while both groups had similar outcomes on the linguistic measures, the

app-learning students struggled more in conversation compared to those in

classroom-based instruction. Participants in Loewen et al. (2020) also perceived

app-based learning to be effective for grammar and vocabulary development, but

less so for speaking skills (even by the most successful participants). One of the

advantages of apps is flexibility of use, and research has shown that apps are

25

Research Report

typically used during ‘dead time’ such as commuting (Wu, 2015). It is possible that

when using apps in this manner, students do not turn on the audio in the listening

activities, but they can still complete the task and progress through the path because

listening tasks tend to be supported by reading. Thus, their listening opportunities

would be reduced. To improve on this aspect, apps could try to better control the

listening exposure that students received, perhaps by including self-evaluation

exercises to raise awareness of how many audios they have listened to, or by

implementing progression locks, whereby students have to complete a minimum

number of listening-only tasks before they can progress on to the next lesson

(balanced with flexibility to avoid frustration and disengagement). It is worth noting

that the Classroom learners reported higher weekly exposure to oral English than the

Duolingo learners through watching videos/TV programs and listening to radio,

podcasts, and music, which might explain classroom learners’ greater listening

ability. Previous research has shown that regular out-of-class exposure to

listening-oriented activities can be effective at developing listening skills (e.g.,

Muñoz & Cadierno, 2021).

Interestingly, the findings of the current study show that both modes of instruction

were equally effective regarding the development of productive vocabulary

knowledge. While receptive vocabulary knowledge is considered important for

receptive L2 skills, such as reading and listening, productive vocabulary knowledge is

needed for the productive skills of writing and speaking. Indeed, the PVLT is strongly

associated with L2 production proficiency (Suzuki & Kormos, 2023). Based on this, it

seems that both modes of instruction have similar potential to promote the

development of productive skills at a basic proficiency level. However, further

research is needed to demonstrate if this is the case by actually assessing learners

on their productive skills. In addition, it is worth mentioning that Spanish and English

share a significant number of cognate words (i.e., words that derive from the same

original language). Between 34–37% of English words are cognates with Spanish

(Lubliner & Hiebert, 2011). Thus, it is possible that this cognateness might explain

the relatively good vocabulary gains in the current sample, particularly at the

productive level. Future investigations could compare app-based and

classroom-based learning on the lexical development of English learners from

non-cognate languages.

RQ2: L2 Motivation and Engagement

Regarding the effect of motivation and engagement on L2 learners’ linguistic

development under both modes of instruction, the results paint a mixed picture. The

level of engagement (as measured by average time studying per week) was found to

be significantly different between the two groups, with classroom learners reporting

spending on average more time studying English compared to Duolingo learners. Yet,

54% of the Duolingo learners met the study target of 3-4 hours per week, and thus

26

Research Report

engaged with the course a similar amount of time than classroom learners. This

differs from prior app-based research which showed a general lack of engagement

and persistence with the app course (e.g., only 22% of learners achieved study target

in Loewen et al. 2019). It also might explain why average time studying per week did

not significantly predict development across any of the linguistic measures in this

study, despite study time and persistence being known to strongly influence learners’

linguistic development (García Botero et al., 2019; Loewen et al., 2019, 2020; Norris &

Ortega, 2000).

Interestingly, despite spending more time studying English, classroom learners’ L2

improvement was smaller than for the Duolingo learners. One possible explanation is

that although classroom-based learners spend more hours per week attending

English lessons, it does not necessarily mean that they are engaged with the

activities. On the contrary, in order to complete the lessons and progress on the

course, app-based learners need to actively engage with the tasks, even if for a short

period of time. Another factor might be the gamification elements in app-based

learning, which provide learners with a sense of achievement and progression after

every unit. In a classroom setting, however, feedback and sense of progression may

be delayed or restricted to end-of-semester testing. Thus, even though Duolingo

learners spent somewhat less time studying on average, the lesson time seems to

have been more effective.

Concerning motivation, the study shows that learners in both groups had a high level

of motivation in the lessons and the language prior to the learning period, but that

this motivation decreased significantly after the study period. Due to its dynamic

nature, it is common for motivation levels to change over time (Dörnyei, 2019), and

the present study shows that this occurs in both app-based and classroom-based

instruction. Interestingly, the findings also indicate that Duolingo learners in general

seemed to have slightly higher levels of motivation at posttest than the classroom

learners. This runs counter to prior research that shows that app-based learners

struggle significantly with motivation, engagement and persistence using apps long

term (e.g., García Botero et al., 2019; Loewen et al., 2019). This difference in

motivation

2

between both groups could be influenced by the learning experience. It is

possible that the gamification of Duolingo has led to learners finding the experience

more appealing and enjoyable, leading to increased levels of motivation after the

study period (e.g., James & Mayer, 2019). As suggested by He and Loewe (2022),

another possible reason why Duolingo learners in this study experienced greater

levels of motivation and engagement than in previous studies might be the explicit

weekly goal-setting (i.e., specifying a target study time per week and recording this

time). Overall, the current findings point to the motivational benefits of Duolingo for

L2 learning.

27

Research Report

Finally, regarding the influence of motivation on linguistic achievement, self-reported

motivation in this study only seemed to have a significant effect on the OPT Total,

OPT Grammar and PVLT scores at posttest. This contradicts previous claims that

consider motivation as one of the main predictors of linguistic performance

(Loewen, 2020). The reason for this finding might be inconsistencies between

students’ questionnaire responses and their behavior. For example, García Botero et

al. (2019) found that students reported high motivation and positive attitude toward

using apps, but when interviewed they demonstrated mixed perceptions and a lack

of interest in using the app long term. Future research could further examine this

relationship by collecting interview data on participants’ motivation. Admittedly, the

motivation survey employed in the current study conceptualizes the construct

somewhat broadly. Future research should adopt existing validated scales of

motivation and engagement to assess these constructs, which would allow for a

more precise interpretation of the effect of motivation/engagement on learning

gains.

Conclusion

Although several studies have researched L2 learning through Duolingo (e.g., Loewen

et al., 2019; or Sudina & Plonksy, 2023), this is the first study to examine the

effectiveness of Duolingo on overall L2 proficiency with a control group, and to

assess learners’ vocabulary development at receptive and productive levels (Shortt

et al., 2023). The results show that for older L1-Spanish adult learners at a basic

proficiency level, Duolingo instruction seems to be more effective for L2-English

development than classroom instruction. Specifically, Duolingo’s English course for

Spanish speakers was most effective in developing L2 general proficiency and

receptive vocabulary knowledge. However, the study shows that some more

refinement might be needed to enhance the course’s efficacy in facilitating listening

skills and productive vocabulary knowledge. In summary, the findings from the

present study point to Duolingo as a promising alternative to more traditional L2

teaching methods for the development of L2 proficiency and lexis in learners of

basic proficiency level. Given that Duolingo is one of the most popular language

learning apps, the findings of the present study also offer more generalizable

insights on the effectiveness of app-based vs. classroom-based instruction for the

acquisition of L2s.

28

Research Report

Notes

1. Information on the number of learners in the English course for Spanish

speakers was found at https://www.duolingo.com/courses.

2. The motivation results only represent participants who persisted and

completed the study, who are likely to have more sustained motivation than

those participants who dropped out.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by a Duolingo Efficacy Research grant but was designed and

conducted independently by the author. I would like to thank Duolingo and its