TYPE Original Research

PUBLISHED 07 December 2023

DOI 10.3389/fmed.2023.1088672

OPEN ACCESS

EDITED BY

Eun-Jeong Lee,

Illinois Institute of Technology, United States

REVIEWED BY

Mansoor Malik,

The Johns Hopkins Hospital, United States

Giulia Brisighelli,

University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

*CORRESPONDENCE

Hong Zhen-Xu

†

These authors have contributed equally to this

work and share first authorship

RECEIVED 16 November 2022

ACCEPTED 23 October 2023

PUBLISHED 07 December 2023

CITATION

Lv M, Fang YF, Wang Y and Xu HZ (2023) Factors

contributing to emotional distress when caring

for children with imperforate anus: a multisite

cross-sectional study in China.

Front. Med. 10:1088672.

doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1088672

COPYRIGHT

© 2023 Lv, Fang, Wang and Xu. This is an

open-access article distributed under the terms

of the

Creative Commons Attribution License

(CC BY )

. The use, distribution or reproduction

in other forums is permitted, provided the

original author(s) and the copyright owner(s)

are credited and that the original publication in

this journal is cited, in accordance with

accepted academic practice. No use,

distribution or reproduction is permitted which

does not comply with these terms.

Factors contributing to emotional

distress when caring for children

with imperforate anus: a multisite

cross-sectional study in China

Meng Lv

†

, Ya Feng-Fang

†

, Yi Wang and Hong Zhen-Xu

*

Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Background: Imperforate anus (IA) has a life-long impact on patients and their

families. The caregivers of children with IA (CoCIA) might experience distress,

which could be detrimental to them physically and mentally. However, there are

limitations in the related studies. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of

IA an d the associated factors contributing to the distress experienced by CoCIA.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted in three tertiary children’s

hospitals from November 2018 to February 2019. Distress was assessed using

the Chinese version of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale, and possible

determinants were assessed by the Caregiver Reaction Assessment, the Parent

Stigma Scale, the Parent Perception of Uncertainty Scale, and the Social

Support Scale. Demographic and clinical information was also collected. Multiple

regression analysis was performed to explore the association between variables.

Results: Out of 229 CoCIA, 52.9% reported experiencing a high level of distress

or above. The data analysis revealed that health problems associated with

caregiving, stigma, uncertainty, social support, and children who underwent

anal reconstruction surgery 1 year before or earlier could significantly predicate

caregivers’ distress, and these factors could explain 50.1% of the variance.

Conclusions: The majority of the caregivers of children with IA experience high

levels of distress, particularly when their children undergo an al reconstruction

surgery 1 year before or earlier. Additionally, health problems related to caregiving,

stigma, uncertainty, and low social support could significantly predicate caregivers’

distress. It is important for clinical sta to be aware of the prevalent situation

of caregivers’ distress and to make targeted interventions focused on addressing

modifiable factors that should be carried out in family-based care.

KEYWORDS

anus, imperforate, caregiver, distress, cross-sectional studies

Background

Imperforate anus (IA) is one of the most common types of anore ctal malformation (1),

with an incidence ranging from 1/2,000 to1/5,000 (

2), and its prevalence appears higher in

Eastern countries, possibly due to variations in ethnic and medical settings (

3). IA is generally

categorized into three types: low, intermediate, and high, according to the Wingspread

classification (

4). Anorectal reconstruction is necessary for all affected children, following

which anal dilations are performed until the desired size for their age is achieved (

5).

Additionally, intermediate- and high-type IA patients require a temporary colostomy and

Frontiers in Medicine 01 frontiersin.org

Lv et al. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1088672

typically undergo surgeries in three stages (6, 7). It is essential

for children with IA and their families to have frequent follow-up

sessions (

8).

Caregivers, who are mostly family members, often experience

significant physical, financial, and psychological pressure while

providing care (

9). Additionally, caregiving is a time-consuming

task that may disrupt the daily schedule of caregivers (

10). Thus,

the abovementioned factors may promote a certain le vel of negative

feelings, such as distress, in caregivers of children with IA (CoCIA)

(

11), and the presence of negative emotions can have a detrimental

effect on the quality of care provided. Therefore, it is import ant

to identify the factors associated with distress to help them

more effectively.

It is common to observe stigma in children who are affected

(

12). However, the family members, especially those responsible for

caregiving, may experience stigma due to their close relationship

with the patients (

13, 14). Stigma usually triggers feelings of shame

about their situation, leading to the social isolation of caregivers

(

15). Furthermore, it adversely affects their mental health, thereby

increasing their distress levels (

16).

Despite the advancements in surgical procedures over the past

several decades, postoperative constipation and fecal and urinary

incontinence are highly prevalent among affected individuals (

17),

and it was reported that CoCIA often feel inadequately informed

about the children’s prognosis and how to properly manage their

bowel functions (

1). The aforementioned factors could significantly

increase caregivers’ perception of uncertainty surrounding the

disease (

18), thus contributing to higher levels of distress of

caregivers (

19).

However, studies show that social support is an important

protective factor of an individual’s psychological health and may

have the potential to alleviate caregivers’ distress (

20). Support

from friends, family, or social organizations could alleviate

negative emotional reactions experienced by caregivers during IA

caregiving (

21). Such support might also reduce caregivers’ distress.

Nevertheless, certain studies have shown that caregivers of children

with congenital diseases often lack adequate support (

22), implying

that CoCIA may also potentially experience lower social support

than average.

To date, numerous studies have explored the mental health

of children with IA, but there is limited research on the mental

wellbeing of families caring for children with IA, which include

CoCIA (

10). A previous study indicated that approximately 50%

of CoCIA reported disruptions in their social lives and family

function (

1). However, studies related to caregivers’ psychological

health and its associated factors are currently limited. Therefore,

in this study, we aimed to explore the caregivers’ distress level

and its contributing factors to provide evidence to improve f amily-

based care.

Methods

Study design, setting, and sample

This study utilized a cross-sectional design. Sequential

participant recruitment was conducted, enrolling care givers of

children receiving treatment for IA based on their arrival

order at the hospital between November 2018 and February

2019.

The sample size was calculated using PASS 13.0 software

(NCSS, Kaysville, USA). Considering the number of variables and

pre-test analysis, the effect size was estimated to be moderate at

0.20, according to the result of the pilot study, and a sample size

of 197 caregivers was estimated to achieve the power of 0.8 when

α was set as 0.05. Considering a dropout rate of approximately

20% according to our experience, a minimum sample size of 246

caregivers was required for this study.

Participants

Children who were enrolled in the study were selected if

they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) congenital absence

of anus or congenital anal fistula, (2) a history of surgical

treatment, and (3) those whose guardians had agreed to provide

their children’s data. Children excluded from the study were as

follows:(1) those diagnosed with other life-threatening diseases or

severe comorbidity, such as congenital c ardiac malformation, and

(2) those whose guardians had refused treatment. To participate in

this study, caregivers needed to be (1) aged ≥ 18 years (2) have

cared for the children for at least 4 weeks, and (3) the primary

caregivers, who spent the longest time in caregiving, without any

remuneration. The exclusion criteria included candidates (1) who

underwent severe life events such as cancer in the past 3 months (a

short questionnaire was used for screening) and (2) who refused to

take part in this study.

Measures

Sample characteristics

This study examined the characteristics of both caregivers

and children. The characteristics of caregivers included their

age, gender, marriage, education, work status, income, place of

residence, religion, household structure, and relationship with the

affected children. On the other hand, the characteristics of children

included their age, gender, birth order, the period following anal

reconstruction surgery, IA type, and medical insurance. Some

general questions were also asked: do you deliberately conceal the

children’s disease in your social life (yes/no)?; Are you afraid to give

birth to another child because the current one was born with an IA

(yes/no)?; How frequently do you communicate with medical staff

(never/seldom/general/often/always)?; What is the degree of your

understanding of the disease (not all/little/some/a lot/very well)?

Dependent variable

In our study, distress levels were assessed using the Chinese

version of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) (

23). The

K10 is a screening scale with 10 questions that were constructed

based on t he item response theory models. It was originally

designed for use in the annual US National Health Interview

Survey (NHIS) to measure non-specific psychological distress

experienced by individuals with different mental disorders. The

Frontiers in Medicine 02 frontiersin.org

Lv et al. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1088672

K10 has demonstrated excellent precision within its intended scale

distribution range and consistent levels of severity across various

sociodemographic subgroups (

24). It can be easily administered

by participants themselves or through an interviewer, taking only

approximately 3 min to complete, and is available for free on a

website (

www.crufad.org) (25). The K10 is a validated and effective

measure of nonspecific psychological distress and is widely utilized

in international epidemiological trend surveys (

26, 27). Within the

K10, respondents were asked to indicate the frequency at which

they had experienced mental health-related conditions such as

psychological anxiety and stress over the past 30 days. Each item

was rated on a scale of 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater

severity. The total scores ranged from 10 to 50, with higher scores

indicating higher levels of distress (

28). According to the Victorian

Population Health Survey, a score of 10–15 represented a low level

of distress while a score of 16–21 indicated a moderate level of

distress. A score of 22–29 represented a high level of distress, and

a score of 30–50 indicated a very high level of distress (

29). We

adopted this classification in our study, and the total score of K10

was used for the analysis. The Cronbach’s alpha value of K10 was

0.93 in this study.

Independent variable

The burden of caregivers was assessed using the Chinese

version of the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) (

30).

The 24 items on the questionnaire were divided into five

dimensions, including impact on health, financial situation,

a lack of family support, disrupted daily schedule, and

caregivers’ esteem. Each dimension was analyzed as a separate

factor. The former four dimensions reflected the caregivers’

burden, while the last one assessed the positive reaction of

caregivers. In this study, the total score of each dimension

was used as independent variables (

31), and the Cronbach’s

alpha values were 0.651, 0.802, 0.710, 0.753, and 0.694 for

each dimension.

Stigma was measured using the Chinese version of the

Parent Stigma S cale (

32), which consisted of five items. A 5-

point Likert scale was used to assess each item ranging from

strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5) (

33). The total score

was used for analysis. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha value

was 0.883.

The perception of uncertainty was assessed using

the revised Chinese version of the Parent Perception of

Uncertainty in Illness Scale (PPUS) (

34). The 29 items were

ranked from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree)

(

34). The total score was calculated as an independent

variable. The Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.914 in

this study.

The Social Support Scale developed by Xiao (

35) was used in

this study. There were 10 items in total, and higher scores indicated

greater level of social support. This classic scale was developed in

the Chinese context and is widely used in Chinese studies (

36). In

this study, Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.819, and the total score was

summed as an independent factor.

Data analysis

For qualitative data, the frequency and percentage were

used to represent the results. For quantitative data, normally

distributed data were described using the mean plus or minus

the standard deviation, while non-normally distributed data were

described using the median and quartiles. A univariate analysis was

conducted with K10 serving as the dependent variable and sample

characteristics as the independent variable. If the independent

variable satisfies the assumption of normality and homogeneity of

variance, the Student’s t-test was used to compare the two groups,

while ANOVA was used to compare the means among multiple

groups. However, if the data deviate from a normal distribution or

display heteroscedasticity, non-parametric tests such as the Mann-

Whitney U-test were employed. In the case of non-parametric

comparisons involving multiple groups, the Kruskal-Wallis test was

utilized. The Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated

to assess the potential correlations between distress and variables

such as CRA, stigma, PPUS, and social support. Multiple linear

regression was performed to analyze the associated factors of

caregivers’ distress. Statistical significance was assessed at the 5%

level (p < 0.05).

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained for this study (2018-IRB-081).

A pilot test of 30 primary caregivers was conducted to ensure

that the questionnaire contents could be properly understood. In

our formal study, we utilized an online survey to collect data.

Specifically, the principal investigator set up three separate WeChat

groups, one for each center involved in our multi-center study. In

each group, a pediatric surgeon and a wound ostomy continence

nurse were invited to act as consultants. To ensure maximum

participation, we first added each caregiver participant on WeChat.

If they expressed a willingness to complete the survey, the principal

investigator would contact them online and provide them with

the link to the online survey. This link was composed of two

parts: an electronic consent form and a set of questionnaires.

Caregivers could only proceed to the questionnaires after clicking

on “I have read all the content and agree to participate in the study”.

Participants were able to complete the survey eit her in a separate

room at the clinic of pediatric surgery or in the comfort of their

own homes, depending on their preference and convenience. For

illiterate candidates, researchers read and explained every item to

ensure inclusivity. All caregivers were informed about the WeChat

groups and given a brief introduction to the study. They were also

offered the option to join the groups, regardless of whether t hey

would like to participate in the survey. These groups provided a

forum for patients and caregivers to connect with others who had

comparable experiences. They were able to discuss any questions

that came up while filling out the questionnaires and receive

additional information and support. It is also noteworthy that

these WeChat groups continued to operate after the project had

concluded, providing ongoing medical advice and social support

to caregivers.

Frontiers in Medicine 03 frontiersin.org

Lv et al. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1088672

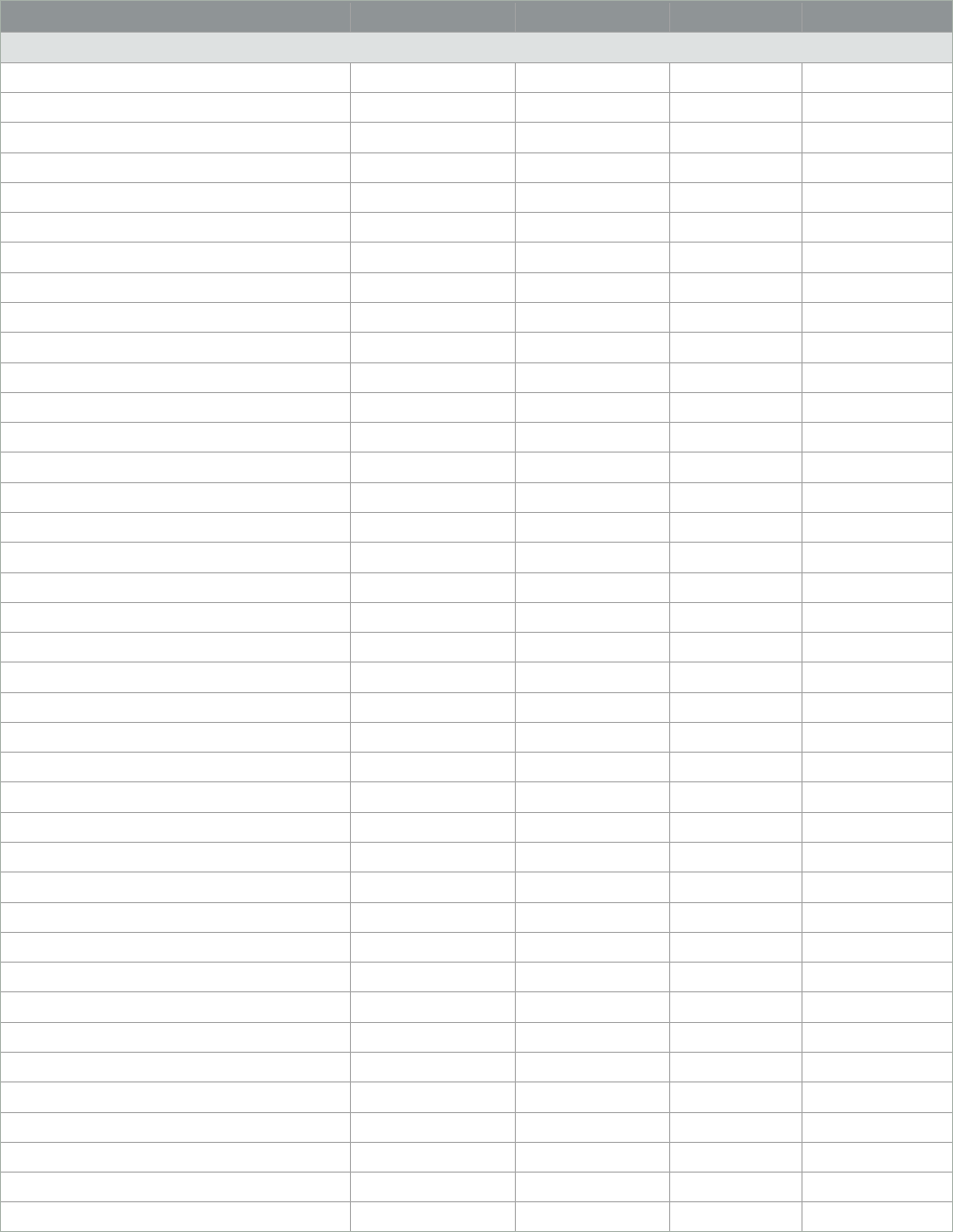

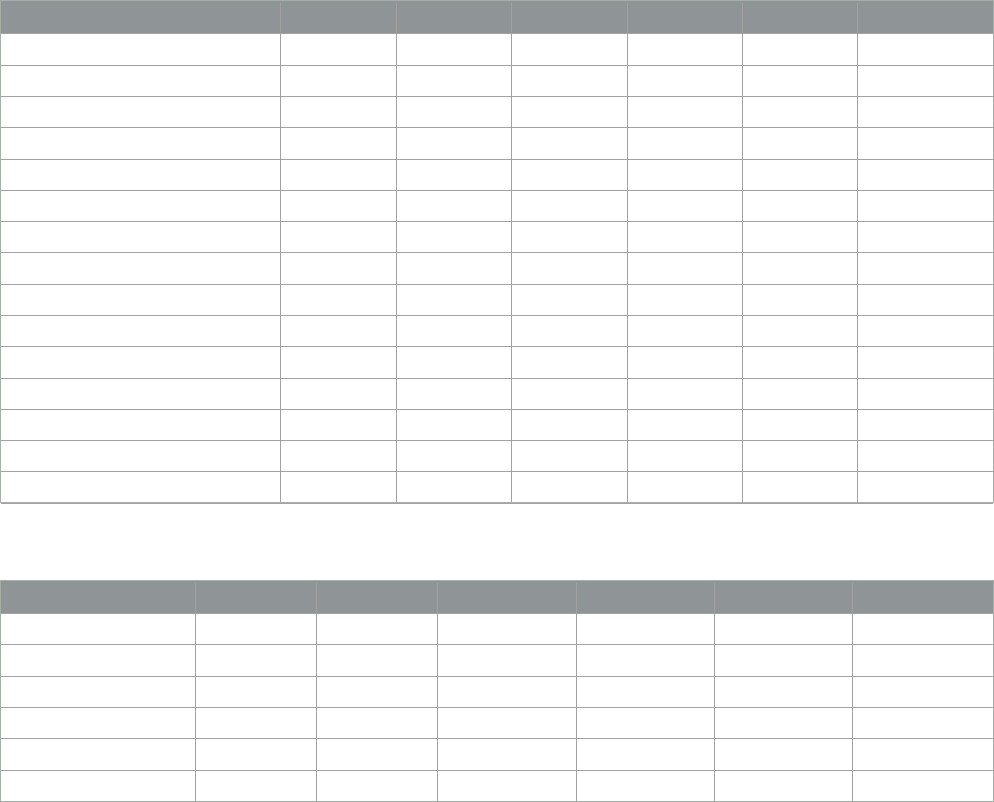

TABLE 1 Descriptive statistics and univariate analysis (N = 229).

Item N (%) K10 χ

2

/t/z P

Caregiver

Age 0.402 0.670

<30 100 (43.7) 22.80 ± 7.33

30–40 106 (46.3) 23.47 ± 7.30

>40 23 (10.0) 22.13 ± 8.56

Gender 0.677 0.499

Men 41 (17.9) 23.76 ± 6.70

Women 188 (82.1) 22.89 ± 7.58

Marriage −0.087 0.930

Married 222 (96.9) 23.04 ± 7.49

Other 7 (3.1) 23.29 ± 5.44

Education 0.543 0.653

Primary school or below 17 (7.4) 24.06 ± 6.83

Junior high school 68 (29.7) 23.77 ± 6.81

High school 45 (19.7) 22.91 ± 6.81

University/college or above 99 (43.2) 23.04 ± 7.42

Occupation 1.725 0.181

Part-time job 32 (14.0) 25.22 ± 6.50

Full-time job 84 (36.7) 22.39 ± 7.72

Unemployed 113 (49.3) 22.91 ± 7.40

Relationship wit h children 1.636 0.197

Mother 178 (77.7) 22.76 ± 7.44

Father 44 (19.2) 24.64 ± 7.00

Others 7 (3.1) 20.29 ± 8.90

Income (RMB)

<8,000 111 (48.5) 24.56 ± 6.75 −3.465 0.001

≥8,000 118 (51.5) 20 (16, 25)

Inhabitant 1.692 0.187

City 61 (26.6) 21.72 ± 7.61

Suburban 76 (33.2) 22.99 ± 7.16

Countryside 92 (40.2) 23.97 ± 7.46

Household structure −1.097 0.274

Extended family 150 (65.5) 22.65 ± 6.72

Nuclear family 79 (34.5) 23.79 ± 8.60

Religion 1.250 0.212

Yes 71 (31.0) 23.96 ± 8.62

No 158 (69.0) 22.63 ± 6.81

Medical insurance −1.633 0.104

Yes 173 (75.5) 22.59 ± 7.29

No 56 (24.5) 24.45 ± 7.71

(Continued)

Frontiers in Medicine 04 frontiersin.org

Lv et al. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1088672

TABLE 1 (Continued)

Item N (%) K10 χ

2

/t/z P

Concealment behavior 2.522 0.012

Yes 161 (70.3) 23.84 ± 7.49

No 68 (29.7) 21.16 ± 6.96

Afraid to have another child 3.273 0.001

Yes 139 (60.7) 24.31 ± 7.59

No 90 (39.3) 21.09 ± 6.75

Communication frequency with medical staff 1.569 0.118

General or below 138 (60.3) 23.67 ± 7.24

Often or above 91 (39.7) 22.10 ± 7.64

Understanding of IA 0.154 0.878

Some or below 176 (76.9) 23.09±7.40

A lot or above 53 (23.1) 22.91 ± 7.57

Children

Age (y) −0.849 0.397

<2 189 (82.5) 22.85 ± 7.39

≥2 40 (17.5) 23.95 ± 7.62

Gender 0.062 0.951

Men 154 (67.2) 23.07 ± 7.18

Women 75 (32.8) 23.00 ± 7.96

Birth order −0.849 0.397

1 102 (44.5) 22.58 ± 7.22

≥2 127 (55.5) 23.42 ± 7. 60

Time since anal reconstruction surgery (y) −1.995 0.047

<1 128 (55.9) 22.18 ± 7.37

≥1 101 (44.1) 24.14 ± 7. 39

IA type 5.136 0.007

Low 124 (54.1) 21.64 ± 6.63

Intermediate 41 (17.9) 24.29 ± 9.60

High 64 (27.9) 24.97 ± 6.82

Combined with other abnormalities 1.687 0.093

Yes 94 (41.0) 24.03 ± 7.79

No 135 (59.0) 22.36 ± 7.11

Results

Sample characteristics

The data analysis was conducted using 229 completed

questionnaires from primary caregivers (response rate = 90.16%).

Out of the initial pool of 254 participants who were eligible for

this study, 18 individuals declined to participate citing the reason

as the lack of interest or unwillingness to discuss their child’s

disease. Additionally, seven participants were excluded from the

study due to incomplete questionnaires. Based on the sample

size of 229, an effective size of 0.20, and an α-value set at 0.05,

the actual statistical power of this study was calculated to be

0.857. The characteristics of both the caregivers and children are

presented in

Table 1. The age of the caregivers who participated

in the study ranged from 18 to 67 years, with a median age

of 30 (interquartile range: 28–36). The age of children who

participated in the study ranged from 0.08 to 6.37 years old,

with a median age of 0.87 years (interquartile range: 0.37–

1.78).

Frontiers in Medicine 05 frontiersin.org

Lv et al. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1088672

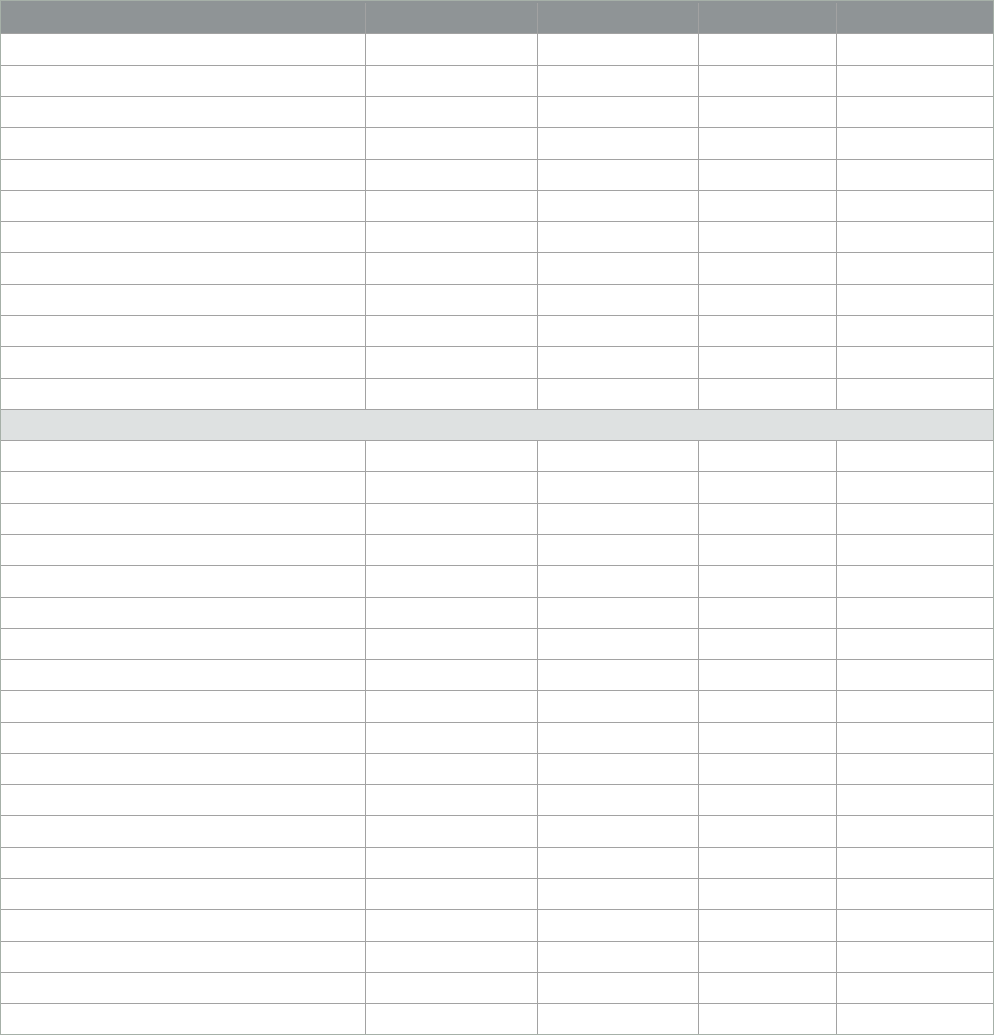

TABLE 2 Category of K10 score (N = 229).

Degree of distress N (%)

Low 34 (14.8)

Moderate 74 (32.3)

High 75 (32.8)

Very high 46 (20.1)

TABLE 3 Descriptive statistics for measurement scales (N = 229).

Item Total score (range) Item average

(range)

K10 23.04 ± 7.42 (10.00–50.00) 2.30 ± 0.74 (1.00–5.00)

CRA

Health problem 10.74 ± 2.63 (4.00–18.00) 2.69 ± 0.66 (1.00–4.50)

Financial problem 8.77 ± 2.77 (3.00–15.00) 2.92 ± 0.92 (1.00–5.00)

Lack of family support 11.22 ± 3.19 (5.00–22.00) 2.24 ± 0.64 (1.00–4.40)

Disrupted schedule 18.00 ± 3.60 (5.00–25.00) 3.60 ± 0.71 (1.00–5.00)

Self-esteem 29.01 ± 3.20 (20.00–35.00) 4.14 ± 0.46 (2.86–5.00)

Stigma 14.98 ± 4.81(5.00–25. 00) 3.00 ± 0.96 (1.00–5.00)

PPUS 72.58 ± 14.06 (29.00–102.00) 2.59 ± 0.50 (1.04–3.64)

Social support 40.33 ± 8.36 (16.00–62.00) 2.88 ± 0.60 (1.14–4.43)

K10, Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; CRA, Caregiver Reaction Assessment; PPUS, Parent

Perception of Uncertainty Scale.

Measurement results

The mean distress score of caregivers was 23.04.

Table 2

presented the distribution of distress levels, which were as follows:

low-−34 (14.8%), moderate−74 (32.3%), high−75 (32.8%), and

very high−46 (20.1%). The total score and average score of the

items for the measurement scales, including K10, CRA, PPUS,

social support, and stigma, were shown in Table 3.

Univariate analysis

The univariate analysis identified the significant differences in

income, the period following anal reconstruction surgery, IA type,

concealment behavior, and fear of having another child (

Table 1).

The relationships between CRA, stigma, PPUS, social support, and

distress are shown in

Table 4. The correlation analysis showed

that there were statistically significant correlations between CRA,

stigma, PPUS, and social support with K10.

Multiple regression analysis

The associated factors of caregivers’ distress were explored

using the multiple regression analysis.

Table 5 displays the results

of the multiple regression analysis of significant univariable factors.

Table 6 reveals that independent factors contributing to the distress

of IA care givers included health problems pertaining to caregiving

TABLE 4 Correlations (r) between CRA, stigma, PPUS, social support, and K10.

K10 CRA health

problem

CRA

financial problem

CRA lack of

family

support

CRA

disrupted schedule

CRA self-

esteem

PPUS Social

support

Stigma

K10 1.00 0.623

∗∗

0.435

∗∗

0.285

∗∗

0.322

∗∗

−0.250

∗∗

0.529

∗∗

−0.424

∗∗

0.397

∗∗

CRA

Health problem 0.623

∗∗

1.00 0.506

∗∗

0.277

∗∗

0.424

∗∗

−0.270

∗∗

0.407

∗∗

−0.343

∗∗

0.314

∗∗

Financial problem 0.435

∗∗

0.506

∗∗

1.00 0.330

∗∗

0.443

∗∗

−0.217

∗∗

0.489

∗∗

−0.378

∗∗

0.233

∗∗

Lack of family support 0.285

∗∗

0.277

∗∗

0.330

∗∗

1.00 0.263

∗∗

−0.251

∗∗

0.358

∗∗

−0.438

∗∗

0.163

∗

Disrupted schedule 0.322

∗∗

0.424

∗∗

0.443

∗∗

0.263

∗∗

1.00 00.099 0.201

∗∗

−0.275

∗∗

0.283

∗∗

Self-esteem -0.250

∗∗

−0.270

∗∗

−0.217

∗∗

−0.251

∗∗

00.099 1.00 −0.332

∗∗

0.305

∗∗

−0.185

∗∗

PPUS 0.529

∗∗

0.407

∗∗

0.489

∗∗

0.358

∗∗

0.201

∗∗

−0.332

∗∗

1.00 −0.364

∗∗

0.283

∗∗

Social support -0.424

∗∗

−0.343

∗∗

−0.378

∗∗

−0.438

∗∗

−0.275

∗∗

0.305

∗∗

−0.364

∗∗

1.00 −0.293

∗∗

Stigma 0.397

∗∗

0.314

∗∗

0.233

∗∗

0.163

∗

0.283

∗∗

−0.185

∗∗

0.283

∗∗

−0.293

∗∗

1.00

CRA, Careg iver Reaction Assessment; PPUS, Parent Perception of Uncertainty Scale.

∗∗

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

∗

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Frontiers in Medicine 06 frontiersin.org

Lv et al. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1088672

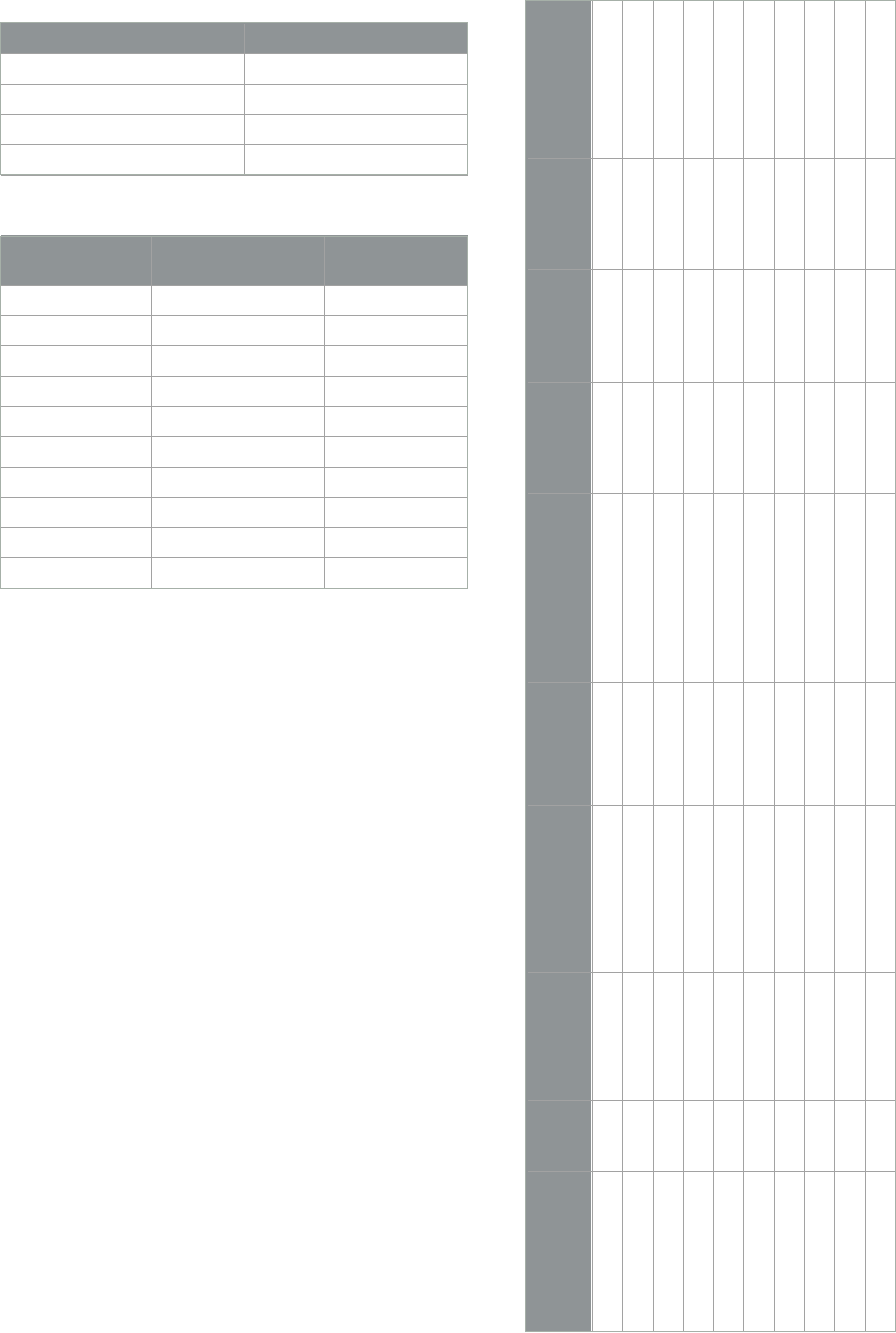

TABLE 5 Multiple regression analysis of significant univariable factors (N = 229).

Item B SE SB t P VIF

Constant −0.553 6.204 −0.089 0.929

Stigma 0.228 0.083 0.148 2.745 0.007 1.311

CRA

Health problem 1.333 0.183 0.472 7.278 <0.001 1.898

Finance problem −0.125 0.175 −0.047 −0.716 0.475 1.912

Lack of family support −0.011 0.134 −0.005 −0.082 0.935 1.501

Disrupted schedule −0.047 0.131 −0.022 −0.356 0.722 1.761

Self-esteem 0.119 0.127 0.051 0.934 0.351 1.354

Social support −0.104 0.053 −0.117 −1.966 0.051 1.598

PPUS 0.128 0.032 0.242 3.978 <0.001 1.675

Time since anal reconstruction surgery 1.385 0.724 0.093 1.914 0.057 1.062

Income −1.249 0.804 −0.084 −1.553 0.122 1.327

Concealment behavior −0.944 0.832 −0.058 −1.135 0.258 1.188

Afraid to have another child 0.167 0.776 0.011 0.216 0.829 1.18

IA type 0.15 0.436 0.018 0.344 0.731 1.178

R

2

= 0.524, R

2

ad

= 0.495, F = 18.178, P < 0.01. Durbin-Watson = 2.020.

TABLE 6 Multiple regression analysis of independent influencing factors (N = 229).

Item B SE SB t P VIF

Constant −0.809 3.711 – −0.218 0.828 –

CRA Health problem 1.186 0.153 0.420 7.747 <0.01 1.341

PPUS 0.132 0.028 0.251 4.652 <0.01 1.327

Stigma 0.243 0.078 0.157 3.105 0.002 1.171

Social support −0.104 0.047 −0.118 −2.212 0.028 1.289

Time since surgery 1.445 0.704 0.097 2.051 0.041 1.017

R

2

= 0.512, R

2

ad

= 0.501, F = 46.714, P <0.01. Durbin-Watson = 2.011.

(B = 1.186), PPUS (B = 0.132), stigma (B = 0.243), social support

(B = −0.104), and children who underwent anal reconstruction

surgery ≥1 year (B = 1.445). These factors accounted for a variance

of 50.1% of c are givers’ distress.

Discussion

This study investigated the extent of distress experienced

by CoCIA and identified its contributing factors. On average,

the caregivers obtained a K10 score of 23.04, which indicates

a high level of distress. This score was much higher than both

the average population score (15.42) (

37) and the score for

patients with chronic illness (20.25) (

38). According to a study,

the K10′s cutoff point was found to be 16, which falls under

the moderate classification category. The study also found that,

when higher scores were observed on the scale, the level of

psychological distress reported was proportionally higher as well

(

39). In this study, it was found that approximately 85.15% of

the caregivers scored at least 16 points, which suggested that

professional psychological consultation should be recommended

for this population. Caregivers play a crucial role in establishing

a connection between the affected children and medical staff;

however, if they experience psychological distress, the quality of

care given to IA children may be compromised due to ineffective

cooperation with the medical staff (

14). Therefore, clinical medical

staff should pay more attention to the caregivers’ mental health,

screen out the high-risk population with effective tools, such as

K10, and cooperate with professional psychiatrists.

Different stages of IA diagnosis have an effect on caregivers’

psychological state (

10). According to our study, children who

underwent surgery for IA for 1 year before or earlier were found to

be significantly associated with higher levels of caregivers’ distress,

highlighting their role as a significant predictor, that is, the longer

the caregiving duration, t he greater the possibility of burnout (

40).

One possible explanation might be that caregiving for a short

period can be manageable, but over a long period of time, it can

have a detrimental effect on the psychological health of caregivers

and ultimately result in burnout. Therefore, clinical nurses and

surgeons should pay particular attention to CoCIA with a history

Frontiers in Medicine 07 frontiersin.org

Lv et al. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1088672

of anal reconstruction surgery 1 year before or earlier. While

caregiving tasks eventually reduce at the end of surgical therapy,

distress levels may, on the other hand, increase due to the long

duration of caregiving.

Health problems can play a significant role in causing distress

for IA caregivers. Caring for a child with chronic illness can be a

challenging task that imposes a considerable amount of stress on

the caregivers and can have a negative effect on the physical health

of caregivers (

41). In a previous study, it was found that caregivers

of children with chronic illness experience more healt h problems

compared to caregivers of healthy children, and this can be solely

attributed to the challenges of caregiving (

42). Moreover, the health

problems could also negatively influence caregivers’ mental health

and increase their distress level, which is harmful to both the

caregivers and their children (

43). Thus, medical staff could provide

caregivers with more he alth-keeping knowledge while treating the

affected children and encourage caregivers to ask for medical help

if necessary. Additionally, it is important to teach nursing skills

such as ostomy-c are experience and dietary recommendations

to enhance caregivers’ illness management abilities, which may

potentially alleviate caregiving burden and reduce the caregivers’

health problems (

44).

Perceiving uncertainty of the children’s illness improvement is

an important determinant of IA caregivers’ distress. The persistent

uncertainty could lead to higher levels of anxiety and distress

among caregivers, thus negatively affecting their overall wellbeing

(

19, 45). However, some studies indicated that caregivers might also

benefit from embracing uncertainty, as acknowledging it opens up

the possibility for positive prognoses in the affected children, which

could also be viewed as an opportunity for a favorable outcome

(

46). However, the impact of uncertainty on caregivers’ distress

usually depends on their individual perspectives and personal

viewpoints. On the one hand, as a member of medical staff,

we could provide additional information to support caregivers

to mitigate their unnecessary anxiety about their children and

reduce the negative effect of uncert ainty (

45). On the other hand,

encouraging caregivers to focus on the benefits that can come from

uncertainty could help promote optimism and a more positive

outlook on the prognosis. Stigma is also a determinant of caregivers’

distress. Since the children are usually unaware of their situation,

particularly when they are young, the caregivers may experience

higher perceived stigma and social discrimination since the burden

falls solely on caregivers (

16). The stigma causes them to experience

more distress because of their personal disapproval and self-

depreciation as well as poses a barrier for the c are givers to seek

help from medical services, which might result in undermining the

quality of the care given (

47). Thus, interventions focused on stigma

should be implemented. Studies have shown that providing detailed

explanations about the disease, sharing testimonies of individuals

living with the stigma, and incorporating active-learning exercises

contribute to mitigating stigmatization, thus reducing c are givers’

distress (

47).

According to the results of this study, it was found that

social support is a determinant of distress among IA caregivers.

Social support plays a significant protective role in individual

psychological health, potentially reducing caregivers’ distress (

20).

Medical staff should motivate caregivers to seek additional social

support, such as encouraging them to seek help from their family

members, and ensuring they have increased access to contact

medical staff for further inquiries. Peer support can be harnessed

through initiatives such as establishing IA-related communication

groups to provide assistance (

48).

Conclusions

CoCIA experience a high level of distress, especially when their

children undergo anal reconstruction surgery 1 year before or

earlier. This heightened distress is linked to health problems arising

from caregiving, increased perception of stigma and uncertainty,

and a lower level of social support. Therefore, it is crucial for

medical staff to pay attention to t he continuing needs of these

caregivers during follow-up appointments, e ven after the patients

have completed their surgical therapy. Additionally, some measures

aiming to improve the caregivers’ health condition and reduce

their stigma should be implemented. We should also provide

more medical information to alleviate caregivers’ anxiety caused by

uncertainty, encourage them to be optimistic, and help them find

greater social support to promote their psychological health.

Limitations

This study, as any other study, has its limitations. First, we used

an outdated classification system. During the data collection period,

the Wingspread classification was still being used as the standard in

the Chinese medical system. Unfortunately, due to restricted access

to patient data, we were unable to obtain detailed descriptions of the

disease to accurately reclassify our patients according to updated

systems such as the Krickenbeck classification. Second, due to the

correlational nature of the evidence, we could not ascertain the

direction of some associations. For example, distress resulting from

prolonged caregiving might, in turn, negatively affect the health of

caregivers. Therefore, prospective studies are required to identify

the dire ction of associations. Finally, we may have overlooked some

important factors that could potentially contribute to caregivers’

distress, such as family function, which is regarded as a crucial

factor in personal psychological health.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be

made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Zhejiang

University School of Medicine, China. The studies were conducted

in accordance with the local legislation and institutional

requirements. Written informed consent for participation in

this study was provided by the participants’ le gal guardians/next

of kin.

Frontiers in Medicine 08 frontiersin.org

Lv et al. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1088672

Author contributions

YF-F conceived and supervised the study and extracted data.

ML extracted data, performed data analysis, and developed the

manuscript. YW performed data analysis and provided input on

manuscript development. HZ-X helped write the manuscript and

provided critical input on its revisions. All authors contributed to

the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants who took part in the

survey. We also want to extend our gratitude to Dr. Shoujiang

Huang and Dr. Qi Qin for their assistance in informing the

caregivers about this study, as well as Nurse Fang Li, who patiently

answered the caregivers’ questions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that t he research was conducted

in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships

that could be construed as a potential conflict

of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those

of the aut hors and do not necessarily represent those of

their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher,

the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be

evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by

its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the

publisher.

References

1. Cai ro S, Gasior A, Rollins M, Rothstein D. Challenges in transition

of care for patients with anorectal malformations: a systematic review and

recommendations for comprehensive care. Dis Colon Rectum. (2018) 61:390–

9. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001033

2. Steeg Hvd, Botden S, Sloots C, Steeg Avd, Broens P, Heurn Lv, Travassos D,

Rooij Iv, Blaauw Id: Outcome in anorect al malformation type rectovesical fistula:

a nationwide cohort study in The Netherlands. J Pediat Surg. (2016) 51:1229–

33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.02.002

3. Gangopadhyay AN, Pandey V . Controversy of single versus staged

management of anorectal malformations. Indian J Pediatr. (2017)

84:636–42. doi: 10.1007/s12098-017-2373 -6

4. Steeg Hvd, Schmiedeke E, Bagolan P, Broens P, Demirogullari B, Garcia-Vazquez

A, et al. European consensus meeting of ARM-Net members concerning diagnosis and

early management of newborns with anorec tal malformations. Techniq Coloproctol.

(2015) 19:181–5. doi: 10.1007/s10151-015-1267-8

5. Jenetzky E, vanRooij IALM, Aminoff D, Schwarzer N, Reutter H, Schmiedeke E,

et al. The challenges of the European anorectal malformations-net registry. Eur J Pediat

Surg. (2015) 25:481–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1569149

6. Baayen C, Feuillet F, Clermidi P, Crétolle C, Sarnacki S, Podevin G, et al. Validation

of the French versions of the Hirschsprung’s disease and Anore c tal malformations

Quality of Li fe (HAQL) questionnaires for adolescents and adults. Health Qual Life

Outc. (2017) 15:24. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0599-7

7. Nam SH, Kim DY, Kim SC. Can we expect a favorable outcome after

surgical treatment for an anorectal malformation? J Pediatr Surg. (2016) 51:421–

4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.08.048

8. Goudarzi Z, Askari M, Seyed-Fatemi N, Asgari P, Mehran A. The effect

of educational program on stress, anxiety and depression of the mothers of

neonates having colostomy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2016) 29:3902–

5. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2016. 1152242

9. Al-Gamal E, Long T, Shehadeh J. Health satisfaction and family impact of parents

of children with cancer: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Scand J Caring Sci. (2019)

33:815–23. doi: 10.1111/scs.12677

10. Witvliet MJ, Bakx R, Zwaveling S. Dijk THv, Steeg AFWvd: Quality of

life and anxiety in parents of children with an anorectal malformation or

Hirschsprung disease: the first year after diagnosis. Eur J Pediat Surg. (2016) 26:002–

6. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1559885

11. Majestic C, Eddington KM. The impact of goal adjustment and caregiver burden

on psychological distress among caregivers of cancer patients. Psychooncology. (2019)

28:1293–300. doi: 10.1002/pon.5081

12. Ojmyr-Joelsson M, Nisell M, Frenckner B, Rydelius P-A, Christensson K. A

gender perspective on the extent to which mothers and fathers each take responsibility

for care of a child with high and intermediate imperforate anus. J Pediatr Nurs. (2009)

24:207–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2007.0 9.004

13. Hamlington B. E.lvey L, Brenna E, Biesecher LG, B.Biesecker B,

Sapp J. Characterization of courtesy stigm a perceived by parents of

overweight children with bardet-biedl syndrome. PLoS ONE. (2015)

10:e0140705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140705

14. Chang C, Su JA, Tsai CS, Yen C, Liu JH, Lin CY. R asch analysis suggested three

unidimensional domains for Affiliate Stigma Scale: additional psychometric evaluation.

J Clin Epidemiol. (2015) 68:674–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.01.018

15. Li J, Mo P, Wu A, Lau J. Roles of self-stigma, social support, and

positive and negative affects as determinants of depressive symptoms among HIV

infected men who have sex with men in China. AIDS Behav. (2017) 21:261–

73. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1321-1

16. Zhou T, Wang Y, Yi C. Affiliate stigma and depression in caregivers of children

with Autism Spectrum Disorders in China: Effects of self-esteem, shame and family

functioning. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 264:260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.071

17. Lane VA, Nacion KM, Cooper JN, Levitt MA, Deans KJ, Minneci P.

Determinants of quality of life in children with colorectal diseases. J Pediatr Surg. (2016)

51:1843–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.08.004

18. Giuliani S, Decker E, Leva E, Riccipetitoni G, Bagolan P. Long term follow-up

and transition of care in anorectal malformations: an international survey. J Pediatr

Surg. (2016) 51:1450–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.03.011

19. Aldaz BE, Hegarty RSM, Conner TS, Perez D, Treharne GJ. Is avoidance of illness

uncertainty associated with distress during oncology treatment? A daily diary study.

Psychol Health. (2019) 34:422–37. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2018.1532511

20. Choi E, Yoon S, Kim J, Park H, Kim J, Yu E. Depression and distress in

caregivers of children with brain tumors undergoing treatment: psychosocial factors

as m oderators. Psychooncology. (2016) 25:544–50. doi: 10.1002/pon.3962

21. Okuyama J, Funakoshi S, Amae S, Kamiyama T, Ueno T, Hayashi Y. Coping

patterns in a mother of a child with multiple congenital anomalies: a case study. J Intens

Criti Care. (2017) 3:1–6. doi: 10.21767/2471-8505.100075

22. Jacobs R, Boyd L, Brennan K, Sinha CK, Giuliani S. The importance

of social media for patients and families affected by congenital anomalies: a

Facebook cross-sectional analysis and user survey. J Pediatr Surg. (2016) 51:1766–

71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.07.008

23. Zhou C, Chu J, Wang T, Peng Q, He J, Zheng W, et al. Reliability and validity

of 10-item Kessler Scale (K10) Chinese version in evaluation of mental health status of

Chinese population. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2008) 16:627–9.

24. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand

SL, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences

and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. (2002)

32:959–76. doi: 10.1017/S003329170200607 4

25. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening

for serious mental illness i n the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2003)

60:184–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184

26. Sunderland M, Slade T, Stewart G, Andrews G. Estimating the prevalence

of DSM-IV mental illness in the Australian general population using the

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2011) 45:880–

9. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011. 606785

27. Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, Ono Y, Nakane Y, Nakamura Y, et al. The

performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health

Survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. (2008) 17:152–8. doi: 10.1002/mpr.257

Frontiers in Medicine 09 frontiersin.org

Lv et al. 10.3389/fmed.2023.1088672

28. Chan SM, Fung TCT. Reliability and validity of K10 and K6 in screening

depressive symptoms in Hong Kong adolescents. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. (2014)

9:75–85. doi: 10.1080/17450128. 2013.86 1620

29. Victorian Population Health Survey. Victorian Population Health Survey 2008

vol. 26. Melbourne, Victoria: Department of Health. (2008).

30. Yaping Z, Yan L, Huiqin W. Validity and reliability research of Chinese

edition of caregiver reaction assessment. Chin J Nurs. (2008) 43:856–9.

doi: 10.3761/j.issn.0254-1769.2008.09.042

31. Petrinec A, Burant C, Douglas S. Caregiver reaction assessment: psychometric

properties in caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Psychooncology. (2016) 26:1–

3. doi: 10.1002/pon.4159

32. Wang D, Jia Y, Gao W, Chen S, Li M, Hu Y, et al. Relationships

between stigma, social support, and distress in caregivers of Chinese children with

imperforate anus: a multicenter cross-sectional study. J Pediat Nus. (2019) 49:e15–

e20. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2019.0 7.008

33. Austin J, MacLeod J, Dunn D, Shen J, Perkins S. Measuring stigma in children

with epilepsy and their parents: instrument development and testing. Epilep Behav.

(2004) 5:472–82. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.04.008

34. Jiaxuan M, Wanhua X, Chunhua M, Yeqing D, Lili D. Initial revision of Chinese

version of parents’ perception of uncertainty scale. Chin J Pract Nurs. (2013) 29:46–50.

doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1672-7088.2013.28.023

35. Xiao S. The theoretical basis and research application of Social Support Scale. J

Clini Psychol Med. (1994) 1994:98–100.

36. Yang Y, Zhang B, Meng H, Liu D, Sun M. Mediating effect of social support

on the associations between health literacy, productive aging, and self-rated health

among elderly Chinese adults in a newly urbanized community. Medicine. (2019)

98:1–8. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000 000015162

37. Chen J. Some people may need it, but not me, not now: seeking professional

help for mental health problems in Urban China. Transcult Psychiat. (2018) 55:754–

74. doi: 10.1177/1363461518792741

38. Xu M, Markström U, Lyu J, Xu L. Survey on tuberculosis patients in rural areas

in China: tracing the role of stigma in psychological distress. Int J Environ Res Public

Health. (2017) 14:1–9. doi: 10.17504/protocols.io.i2fcgbn

39. Peltzer K, Naidoo P, Matseke G, Louw J, McHunu G, Tutshana B.

Prevalence of psychological distress and associated factors in tuberculosis patients

in public primary care clinic s in South Africa. BMC Psychiatry. (2012) 12:1–

9. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-89

40. Nguyen JT, Roberts C, Thorpe CT, Thorpe JM, Hogan SL, McGregor J, et al.

Economic and objective burden of caregiving on informal careg ivers of patients

with systemic vasculitis. Musculoskeletal Care. (2019) 17:282–7. doi: 10.1002/msc.

1394

41. Riffin C, Ness PHV. L.Wolff J, Fried T. Multifactorial examination of caregiver

burden in a national sample of family and unpaid caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2019)

67:277–83. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15664

42. Brehaut JC, Guèvremont A, Arim RG, Garner RE, Miller AR, McGrail KM,

et al. Changes in caregiver health in the years surrounding the birth of a child

with health problems: administrative d ata from B ritish Columbia. Med Care. (2019)

57:369–76. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001 098

43. Venkataramani M, Cheng TL, Solomon BS, Pollack CE. Caregi ver health

promotion in pediatric primary care settings: results of a national survey. J Pediatr.

(2017) 181:1–7.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.10.054

44. Jingting W, Nengliang Y, Yuanyuan W, Fen Z, Yany an L, Zhaohui G, et al.

Developing “Care Assistant”: A smartphone application to support caregivers of

children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. J Telemed Telecare. (2016) 22:163–

71. doi: 10.1177/1357633X15594753

45. Szulczewski L, Mullins LL, Bidw ell SL, Eddington AR, Pai ALH. Meta-analysis:

caregiver and youth uncertainty in pediatric chronic illness. J Pediatr Psychol. (2017)

42:395–421. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsw097

46. Bell M, Biesecker BB, Bodurtha J, Peay HL. Uncertainty, hope, and coping

efficacy among mothers of children with Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy. Clini

Genet. (2019) 95:677–83. doi: 10.1111/cge.13528

47. Nyblade L, Stockton MA, Giger K, Bond V, Ekstrand ML, Lean RM, et al.

Stigma in health facilities: why it matters and how we can change it. BMC Med. (2019)

17:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1256- 2

48. Sari BA, Demirogullari B, Ozen O, iseri E, Kale N, Basaklar C. Quality of life

and anxiety in Turkish patients with anorectal malformation. J Paediatr Child Health.

(2014) 50:107–11. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12406

Frontiers in Medicine 10 frontiersin.org