Maya, Aztec, and

Inca Civilizations

Grade 5 | Unit 2

Teacher Guide

History • GeoGrapHy • CiviCs • arts

Sapa Inca

Aztec Warrior

Moctezuma II

Maya Pyramids

Maya, Aztec,

and Inca

Civilizations

Grade 5 | Unit 2

Teacher Guide

Creative Commons Licensing

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-

ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

You are free:

to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work

to Remix—to adapt the work

Under the following conditions:

Attribution—You must attribute the work in the

following manner:

This work is based on an original work of the Core

Knowledge® Foundation made available through

licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This does not in any way imply that the Core

Knowledge Foundation endorses this work.

Noncommercial—You may not use this work for

commercial purposes.

Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this

work, you may distribute the resulting work only under

the same or similar license to this one.

With the understanding that:

For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to

others the license terms of this work. The best way to

do this is with a link to this web page:

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

Copyright © 2016 Core Knowledge Foundation

www.coreknowledge.org

All Rights Reserved.

Core Knowledge® and

Core Knowledge Curriculum Series™

are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation.

Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book

strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and

are the property of their respective owners. References

herein should not be regarded as affecting the validity of

said trademarks and trade names.

ISBN: 978-1-68380-027-9

Maya, Aztec,

and Inca

Civilizations

Table of Contents

Introduction ...................................................... 1

Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations Sample Pacing Guide .................. 14

Chapter 1 The Maya: Rainforest Civilization ............ 16

Chapter 2 Maya Science and Daily Life ....................30

Chapter 3 The Aztec: Empire Builders .................... 38

Chapter 4 Tenochtitlán: City of Wonder ................. 45

Chapter 5 The Inca: Lords of the Mountains ............ 52

Chapter 6 Inca Engineering ................................ 59

Chapter 7 The End of Two Empires ........................67

Teacher Resources ................................................. 77

1INTRODUCTION

UNIT 2

Introduction

About this unit

The Big Idea

The Maya, Aztec, and Inca had developed large, complex civilizations prior to the arrival of

theSpanish.

The civilizations of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca that once flourished in Central

and South America shared common elements. People practiced farming,

developed social structures, raised armies, and worshipped many gods.

The three civilizations were as diverse as the terrains in which they lived.

The Maya, known for developing a system of mathematics, thrived in the

rainforests of the Yucatán Peninsula, Belize, Honduras, and Guatemala from

about 200 to 900CE. From 1325 to 1521, the Aztec built a large and dense city

at Tenochtitlán, located on a swampy lake in the middle of a semi-arid basin

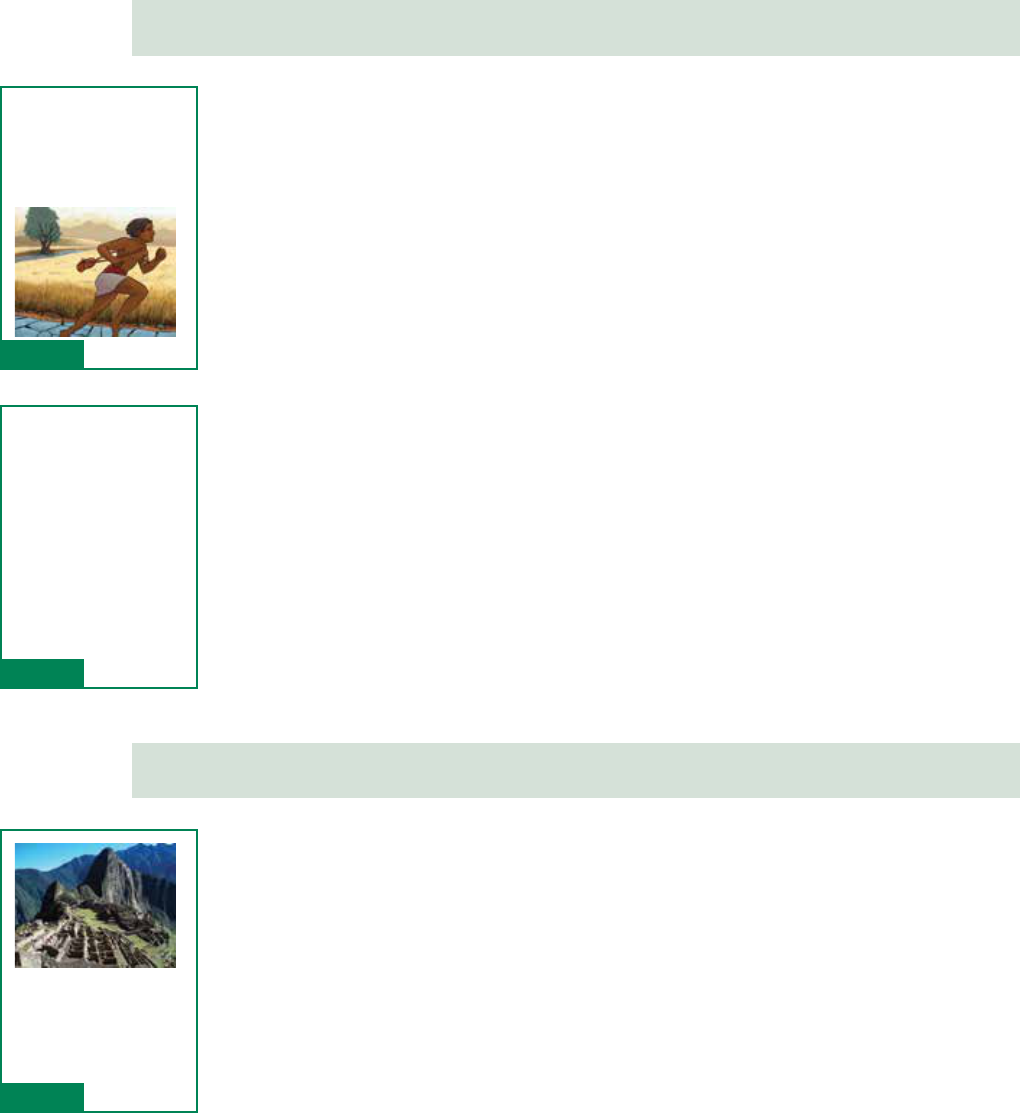

in central Mexico. The Inca were skilled engineers who built a vast system of

roads and bridges to unite their empire located high in the Andes Mountains,

reaching their peak in the 1400s and early 1500s.

It remains in question why and how the rainforest cities of the Classic Maya fell.

We know that Spanish explorers precipitated the destruction of both the Aztec

and Inca empires.

2 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

What Students Should Already Know

Students in Core Knowledge schools should be familiar with:

Kindergarten

• The voyage of Columbus in 1492

- Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain

- The Niña, Pinta, and Santa Maria

- Columbus’s mistaken identification of “Indies” and “Indians”

- The idea of what was, for Europeans, a “New World”

Grade 1

• Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations

- The development by the Maya of large population centers in the

rainforests of Mexico and Central America

- The establishment of a vast empire in central Mexico by the Aztec, its

capital of Tenochtitlán, and its emperor Moctezuma (Montezuma)

- The Inca’s establishment of a far-ranging empire in the Andes

Mountains of Peru and Chile, including Machu Picchu

• Columbus

• The conquistadors

- The search for gold and silver

• Hernán Cortés and the Aztec

• Francisco Pizarro and the Inca

• Diseases devastate Native American population

Grade 2

• The geography of South America

- Brazil: largest country in South America, Amazon River, rainforests

- Peru and Chile: Andes Mountains

- Locate: Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador

- Bolivia: named after Simón Bolívar, “The Liberator”

- Argentina: the Pampa (also known as the Pampas)

- Main languages: Spanish and (in Brazil) Portuguese

3INTRODUCTION

Time Period Background

The items below refer to content in Grade 5.

Use a classroom timeline with students to

help them sequence and relate events from

different periods and groups.

c. 1500 BCE Earliest Mesoamerican villages

c. 200–900 CE Peak of Maya civilization

c. 1300s Beginning of Aztec Empire

c. 1300s Beginning of Inca Empire

1400s First cargo of enslaved people

from Africa brought by

Portuguese to their colonies

1492 Columbus’s first voyage to

the Americas

1496 Santo Domingo on

Hispaniola founded as

first permanent Spanish

settlement in Americas

1500s Spanish brought the first

cargo of enslaved Africans

to Hispaniola

1513 Balboa “discovers” the

Pacific Ocean

1517 Luther initiates Protestant

Reformation

1517 Ponce de León lands in Florida

1519–21 Magellan circumnavigates

the globe

1521 Conquest of the Aztec by

Cortés

1534 Conquest of the Inca by

Pizarro

1534 Cartier of France explores

the St. Lawrence River

1535 Most of central Mexico in

Spanish hands

1539–42 De Soto explores

NorthAmerica

1540 Most of Peru under Spanish

control

1545–65 Major silver discoveries in

Mexico and Peru

c. 1570 End of era of conquistadors

What Students Need to Learn

• Identify and locate Central America and South America on maps

andglobes

- Largest countries in South America: Brazil and Argentina

• Amazon River

• Andes Mountains

• The Maya

- Ancient Maya lived in what is now southern Mexico and parts of

Central America; their descendants still live there today

- Accomplishments as architects and artisans: pyramids and temples

- Development of a system of hieroglyphic writing

- Knowledge of astronomy and mathematics; use of a 365-day

calendar; early use of the concept of zero

• The Aztec

- At its height in the 1400s and early 1500s, the Aztec

empire covered much of what is now central Mexico

- The island city of Tenochtitlán: aqueducts, massive temples, etc.

- Moctezuma (also spelled Montezuma)

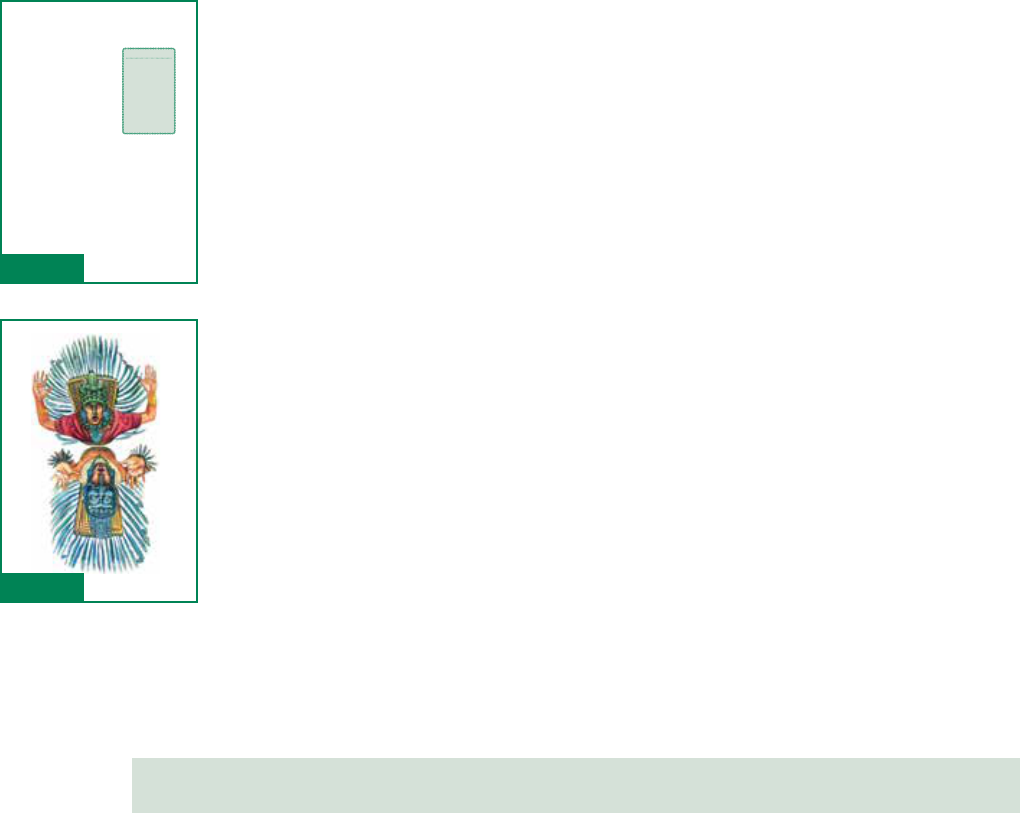

- Ruler-priests; practice of human sacrifice

• The Inca

- Ruled an empire stretching along the Pacific Coast of South America

- Built great cities (Machu Picchu, Cuzco) high in the Andes, connected

by a system of roads

• Conquistadors: Cortés and Pizarro

- Advantages of Spanish weaponry (guns and cannons)

- Devastation of native peoples by European diseases

4 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

At A GlAnce

The most important ideas in Unit 2 are:

• Students should be able to locate Mexico, Central America, South America,

and the major countries, rivers, and mountain chain in South America on

maps and globes.

• Mesoamerica is a cultural area that covers central and southern Mexico as

well as northern Central America.

• The Maya people constructed large monumental buildings, created a

hieroglyphic writing system, employed a 365-day calendar, and developed

the concept of zero.

• The Aztec dominated central and southern Mexico through force and a

tribute system.

• The Inca developed a widespread empire in the Andes Mountains linked by

a network of roads.

• Both the Aztec and the Inca empires were conquered by Spanish

conquistadors; the Aztec Empire was conquered by Cortés, and the Inca

Empire was defeated by Pizarro.

• The Spanish had an advantage over native peoples because the former had

guns, cannons, and horses.

• European diseases killed thousands of native peoples, who had no natural

immunity against them.

WhAt teAchers need to KnoW

Geography Related to Central and South America

Central America is part of North America and contains the countries of Belize,

Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama. It is

bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the east and by the Pacific Ocean to the

west. To the south is the continent of South America. Central America is an

isthmus, or land bridge, that connects the two larger bodies of land.

South America is the fourth largest continent. To the east is the Atlantic

Ocean, and to the west, the Pacific Ocean. The Caribbean Sea borders South

America to the north. The Andes Mountains range from north to south on

the far western side of South America. The northern portion of the continent,

including much of Brazil, is covered by tropical rainforest.

Brazil

Brazil covers almost half of the South American continent and is the fifth

largest country in the world. Brazil is so large that it borders all but two (Chile

5INTRODUCTION

and Ecuador) of the other twelve countries in South America. The word Brazil

comes from the name of a tree found in the Amazon rainforest. Brazil lies

mostly within the tropical zone, so its climate is mainly warm and wet.

Most of the people live in urban areas, and about thirty percent of the

population lives on the coastal plain, a narrow strip along the Atlantic Ocean.

About seven hundred thousand native people live within the rainforest, but

many others live in cities and urban areas. The overall population is a mix of

descendants of Portuguese, native peoples, and Africans. Brazil was conquered

by Portugal, unlike most of South America, which was conquered by the

Spanish. Its official language is Portuguese.

Argentina

Argentina is the second largest country in South America. A long, narrow

country, Argentina extends east and south of the Andes and south of Paraguay

and Uruguay. The Andes form the boundary between Argentina and Chile.

The Gran Chaco, a region of low forests and grasslands, dominates Argentina’s

northern region. The south is a collection of barren plateaus, known as

Patagonia. The major economic area of Argentina is the Pampa (also known

as the Pampas) in the center of the country. This region of tall grasslands and

temperate climate is famous for its cattle ranches. About seventy percent of

the population lives in this area.

Most Argentines are descendants of Spanish colonists, and Spanish is the

official language.

Amazon River

The Amazon River forms at the junction of the Ucayali (/ooh*cah*yah*lee/) and

Marañón (/marn*yeown/) Rivers in northern Peru and empties into the Atlantic

Ocean through a delta in northern Brazil. The Amazon is the second longest

river in the world after the Nile but has the largest volume of water of any

river in the world. Hundreds of tributaries feed into it. The Amazon River basin

drains more than forty percent of South America. With no waterfalls, the river is

navigable for almost its entire length.

The Amazon flows through the world’s largest rainforest. This rainforest is

home to more than 2.5 million species of insects, tens of thousands of plants,

and over one thousand species of birds. In fact, almost half of all of the

world’s known species can be found in the Amazon. Mammals in the Amazon

rainforests include the tapir (a hoofed mammal), the nutria (an otter-like

creature), the great anteater, and various kinds of monkeys. Insects include

large, colorful butterflies. Birds include hummingbirds, toucans, and parrots. A

famous reptile dweller is the anaconda, a huge snake that squeezes its victims

to death; alligators are also common. Fish include flesh-eating piranhas and

the electric eel, capable of discharging a shock up to 650 volts. In recent years,

environmentalists have grown concerned about threats to the ecosystem

posed by logging and deforestation in this rainforest.

6 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

The Amazon was named by a Spanish explorer, Francisco de Orellana, who

explored the river in 1541 and named it after women warriors he encountered

who reminded him of descriptions of the Amazons in ancient Greek mythology.

Andes Mountains

The Andes Mountains are over five thousand miles (8,047 km) in length, the

longest mountain system in the Western Hemisphere. The mountains begin as

four ranges in the Caribbean area on the northeastern coast of South America.

In Peru and Bolivia, the mountains form two parallel ranges that create a wide

plateau known as the Altiplano. The Andes then form a single range that

separates Chile from Argentina.

With an average height of 12,500 feet (3,810 m), the Andes are the second

highest mountain range in the world. (The Himalayas are the highest.) The

tallest peak in the Western Hemisphere is the Andes’s Mount Aconcagua,

which rises 22,835 feet (6,960 m) above sea level. Many of the mountains are

volcanoes, either active or dormant.

Approximately fifty to sixty percent of Peru’s people live in the Altiplano. About

a third of the country’s population lives in the narrow lowlands between the

Andes and the Pacific Ocean. Because the Andes run north to south along the

entire length of Chile, most Chileans live in the Central Valley region between

the Andes and low coastal mountains. The Central Valley, a fertile area, is home

to large cities, manufacturing centers, and agriculture.

The Andes Mountains were the home of the Inca people, whom students

in Core Knowledge schools studied in Grade 1 and will study again as part

of this unit. Core Knowledge students should also have learned about

Mount Aconcagua and the Andes during the Grade 4 geography subsection

“Mountains and Mountain Ranges.”

Historical Background

Students who studied the Core Knowledge curriculum in Grade 1 learned

about how civilizations in the Americas grew. The Maya civilization was located

in the Yucatán Peninsula and covered parts of Mexico, Belize, Honduras,

and Guatemala. Maya cities were built with large centers that included

large temples and often ball courts. Houses did not exist in the city centers,

indicating that they were meant for religious purposes. It’s important to note

that first-grade students were not exposed to the concept of human sacrifice

as a part of both Maya and Aztec religions that will be discussed in this unit.

Most Maya earned a living as farmers. Priests acted as the ruling class. The

Maya civilization disappeared around the year 900 CE; some of their cities

were in ruins by the time Spanish arrived in the 1600s.

The Aztec, also referred to as the Mexica, began as a group of nomadic

peoples who settled on Lake Texcoco in central Mexico around the year 1325.

Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital, was the home to as many as three hundred

thousand people at the time of Spanish arrival. Students learned that the Aztec

7INTRODUCTION

built a vast empire through conquest. They did not directly rule but relied

on a tribute system to expand their wealth. Aztec rulers were seen as divine,

part man and part god. Moctezuma II was ruler of the Aztec when Cortés first

explored Mexico.

The Inca, like the Aztec, built an empire through conquest. From about 1438

to 1525, the Inca ruled an empire that stretched from Ecuador through parts

of Peru, Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina. Students learned that the Inca built an

advanced system of roads to maintain their empire. Roads, bridges, and other

infrastructure made it easier to travel and communicate to administer a vast

empire. Runners called chasquis carried messages throughout the Inca world.

To learn more background information about specific topics taught in Maya,

Aztec, and Inca Civilizations, go to www.coreknowledge.org/about-maya-

aztec-inca.

unit resources

Student Component

The Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations Student Reader—seven chapters

Teacher Components

The Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations Teacher Guide—seven chapters.

This includes lessons aligned to each chapter of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca

Civilizations Student Reader with a daily Check For Understanding and

Additional Activities, such as virtual field trips and cross-curricular art activities,

designed to reinforce the chapter content. A Unit Assessment, Performance

Task Assessment, Activity Pages, and Nonfiction Excerpts of primary source

documents are included at the end of this Teacher Guide in Teacher Resources,

beginning on page 77.

» The Unit Assessment tests knowledge of the entire unit, using

standard testing formats.

» The Performance Task Assessment requires students to apply and

share the knowledge learned during the unit through either an oral or

written presentation.

» The Activity Pages are designed to reinforce and extend content

taught in specific chapters throughout the unit. These optional

activities are intended to provide choices for teachers.

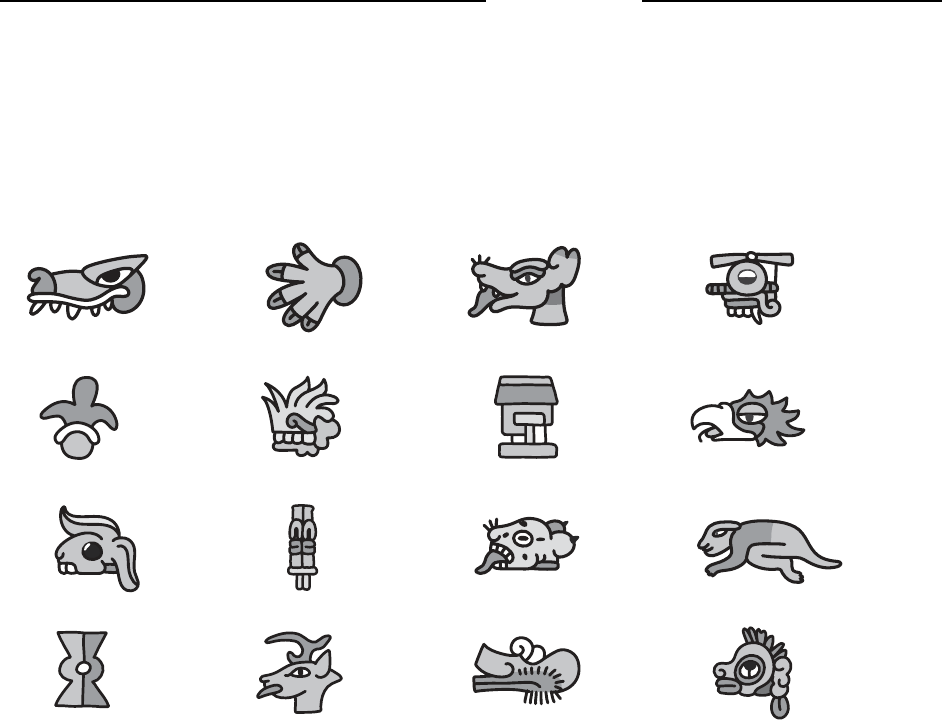

Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations Timeline Image Cards include nine individual

images depicting significant events and individuals from the time when the

Maya, Aztec, and Inca civilizations flourished. In addition to an image, each

8 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

card contains a caption, a chapter number, and the Big Question, which

outlines the focus of the chapter. You will construct a classroom Timeline with

students over the course of the entire unit. The Teacher Guide will prompt you,

lesson by lesson, as to which image card(s) to add to the Timeline. The Timeline

will be a powerful learning tool enabling you and your students to track

important themes and events as they occurred within this time period.

Timeline

Some advance preparation will be necessary prior to starting Unit2.

You will need to identify available wall space in your classroom of

approximately 10 feet on which you can post the Timeline Image

Cards over the course of the unit. The Timeline may be oriented either

vertically or horizontally, even wrapping around corners and multiple

walls, whatever works best in your classroom setting. Be creative—some

teachers hang a clothesline so that the image cards can be attached with

clothespins!

Create five time indicators or reference points for the Timeline. Write each

of the following dates on sentence strips or large index cards:

• 1500 BCE

• 200 CE

• 1300s

• 1400s

• 1500s

Affix these time indicators to your wall space, allowing sufficient space

between them to accommodate the actual number of image cards you will be

adding to each time period, as per the following diagram.

1500 BCE 200 CE 1300s 1400s 1500s

• • • • • • • • •

Chapter 1 2 3, 5 7 7

9INTRODUCTION

You will want to post all the time indicators on the wall at the outset before

you place any image cards on the timeline.

1500 BCE

200 CE

1300s

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3

1300s

1400s

1500s

Chapter 5 Chapter 7 Chapter 7

1500s

1500s

1500s

Chapter 7 Chapter 7 Chapter 7

The Timeline in Relation to the Content in the Student Reader Chapters

You will see that the events highlighted in the Unit 2 Timeline are in

chronological (date) order. The unit as a whole deals with large, thematic

concepts that are reflected in the Timeline.

Understanding References to Time in the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations Unit

As you read the text, you will become aware that in some instances general

time periods are referenced and that in other instances specific dates are cited.

For example, Chapter 1 states that the Maya civilization thrived over a period

of many centuries—200 CE to 900 CE. In addition, certain events are only

10 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

generally fixed in time—for example, that the Inca Empire gained strength in

the 1400s. In contrast, there are many references to specific dates in history.

Here are just a few:

The Aztec founded their capital city by 1325.

Hernán Cortés launched his final attack on Tenochtitlán in 1521.

Pizarro began his quest to find the Inca Empire in 1527.

Because of this, it is important to explain to students that some chapters deal

with themes that were important throughout the entire era of civilization

building in the Americas. It is also important to note that our knowledge of

these times is inhibited by our limited understanding of or access to the record

keeping of these great civilizations. It is sometimes difficult to know precisely

when certain events took place. In some cases, however, the chapters deal with

important people and particular events that occur in specific moments in time.

In these instances, we do have specific knowledge and records. Therefore,

these chapters tend to contain specific dates for key events in history. In

addition, when citing specific dates, the abbreviation CE is used. It’s important

that students understand that the abbreviation CE is used to denote “Common

Era.” (BCE—before the Common Era—is also used here and in other units in

this program.) Students may have encountered CE before, or they may be more

familiar with the traditional abbreviations AD and BC. Both CE and AD refer

to the time period from the time of Jesus Christ. BCE and BC refer to the time

period before Christ.

Time to Talk About Time

Before you use the Timeline, discuss with students the concept of time and how

it is recorded. Here are several discussion points that you might use to promote

discussion. This discussion will allow students to explore the concept of time.

1. What is time?

2. How do we measure time?

3. How do we record time?

4. How does nature show the passing of time? (Encourage students to think

about days, months, and seasons.)

5. What is a specific date?

6. What is a time period?

7. What is the difference between a specific date and a time period?

8. What does CE mean?

9. What is a timeline?

11INTRODUCTION

usinG the teAcher Guide

Pacing Guide

The Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations unit is one of thirteen history and

geography units in the Grade 5 Core Knowledge Curriculum Series™. A total of

ten days have been allocated to the Maya, Aztec, Inca unit. We recommend that

you do not exceed this number of instructional days to ensure that you have

sufficient instructional time to complete all Grade 5 units.

At the end of this Introduction, you will find a Sample Pacing Guide that provides

guidance as to how you might select and use the various resources in this unit

during the allotted time. However, there are many options and ways that you may

choose to individualize this unit for your students, based on their interests and

needs. So we have also provided you with a blank Pacing Guide that you may

use to reflect the activity choices and pacing for your class. If you plan to create a

customized pacing guide for your class, we strongly recommend that you preview

this entire unit and create your pacing guide before teaching the first chapter.

Reading Aloud

In each chapter, the teacher or a student volunteer will read various sections of

the text aloud. When you or a student reads aloud, always prompt students to

follow along. By following along in this way, students become more focused on

the text and may acquire a greater understanding of the content.

Turn and Talk

In the Guided Reading Supports section of each chapter, provide students

with opportunities to discuss the questions in pairs or in groups. Discussion

opportunities will allow students to more fully engage with the content and

will bring “to life” the themes or topics being discussed.

Big Questions

At the beginning of each Teacher Guide chapter, you will find a Big Question,

also found at the beginning of each Student Reader chapter. The Big Questions

are provided to help establish the bigger concepts and to provide a general

overview of the chapter. The Big Questions, by chapter, are:

Chapter Big Question

1

What do the ruins of the Maya tell you about the importance of

religion to their civilization?

2

Why is the 365-day solar calendar developed by the Maya

particularly impressive?

12 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

3

Why did the Aztec make human sacrices?

4

What does the description of Tenochtitlán reveal about the Aztec

civilization?

5

Why were llamas so important to the Inca?

6

How did the Inca use their engineering skills to manage and grow

their empire?

7

What were the factors that contributed to the end of the Aztec

and Inca empires?

Core Vocabulary

Domain-specific vocabulary, phrases, and idioms highlighted in each chapter of

the Student Reader are listed at the beginning of each Teacher Guide chapter,

in the order in which they appear in the Student Reader. Student Reader page

numbers are also provided. The vocabulary, by chapter, are:

Chapter Vocabulary

1

Mesoamerica, Maya, civilization, architecture, archaeologist,

city-state, temple, hieroglyph, sacrice

2

astronomy, leap year, equinox, “initiation ceremony,” priest

3

Aztec, nomadic, empire, emperor

4

causeway, canal, scribe, codex, pictogram, litter, reign

5

Inca, conquistador, “geographical diversity,” plateau, clan, alpaca,

llama, census

6

ocial, engineer, mortar, suspension bridge, terrace

7

expedition, “religious ceremony,” smallpox, immunity, epidemic

Activity Pages

The following activity pages can be found in Teacher Resources, pages 88 to 100.

They are to be used with the chapter specified either for additional class work

or for homework. Be sure to make sufficient copies for your students prior to

conducting activities.

• Chapter 1—World Map (AP 1.1)

• Chapter 1—World Geography (AP 1.2)

• Chapter 1— Modern Map of North America, Central America, and South

America (AP 1.3)

• Chapter 1—Geography of the Americas (AP 1.4)

• Chapter 1—Map of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP 1.5)

• Chapter 1—Geography of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP 1.6)

13INTRODUCTION

• Chapters 2, 4, 6—Summary of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP 2.1)

• Chapter 4—Domain Vocabulary: Chapters 1–4 (AP 4.1)

• Chapter 4—Create a Codex (AP 4.2)

• Chapter 7—Domain Vocabulary: Chapters 5–7 (AP 7.1)

Nonction Excerpts

Two nonfiction excerpts can be found in Teacher Resources, pages 101 to 105.

They may be used with the chapter specified either for additional class work or

at the end of the unit as review and/or a culminating activity. Be sure to make

sufficient copies for your students prior to conducting the activities.

Nonfiction Excerpts

Chapter 7—Primary Source Document: Cortés’s Second Letter to Charles V (NFE 1)

Chapter 7—History of the Conquest of Peru (excerpts from the book by William

Hickling Prescott) (NFE 2)

Additional Activities

An Additional Activities section, related to material in the Student Reader, may

be found at the end of each chapter. You may choose from among the varied

activities when conducting lessons. Many of the activities include website links,

and you should check the links prior to using them in class.

booKs

Haberstroh, Marilyn & Panik, Sharon. A Quetzalcoatl Tale of Chocolate.

CO: University Press of Colorado, 2014.

DK Publishing. Aztec, Inca, & Maya. New York: DK Children, 2011.

Newman, Sandra. The Inca Empire (True Books: Ancient Civilizations). New York:

Scholastic, 2010.

Mathews, Sally Schofer. The Sad Night: The Story of an Aztec Victory and a Spanish

Loss. Boston: HMH Books for Young Readers, 2001

Maloy, Jackie. The Ancient Maya (True Books). Danbury, CT: Children’s Press, 2010

14 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

Maya, aztec, and Inca cIvIlIzatIons sAmple pAcinG Guide

For schools using the Core Knowledge Sequence and/or CKLA

TG – Teacher Guide; SR – Student Reader; AP – Activity Page;

NFE – Nonfiction Excerpt

Week 1

Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5

Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations

“World Map,” “Modern

Map of North America,

Central America, and

South America,” and “Map

and Geography of the

Maya, Aztec, and Inca

Civilizations”

(TG, Chapter 1, Additional

Activities, AP 1.1, 1.3, 1.5,

and 1.6)

Homework: “World

Geography,” AP 1.2 and

“Geography of North

America, Central America,

and South America,” AP1.4

“The Maya:

Rainforest

Civilization”

(TG & SR, Chapter 1)

“Maya Science and Daily

Life”

Core Lesson

(TG & SR, Chapter 2)

“Summary of the

Maya, Aztec, and Inca

Civilizations”

(TG, Chapter 2, Additional

Activities, AP 2.1)

“The Aztec: Empire

Builders”

Core Lesson

(TG & SR, Chapter 3)

CKLA

“Personal Narratives” “Personal Narratives” “Personal Narratives” “Personal Narratives” “Personal Narratives”

Week 2

Day 6 Day 7 Day 8 Day 9 Day 10

Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations

“Tenochtitlán: City of

Wonder”

Core Lesson

(TG & SR, Chapter 4)

Homework: “Summary

of the Maya, Aztec,

and Inca Civilizations”

(TG, Chapter4, Additional

Activities, AP 2.1)

“The Inca: Lords of the

Mountains”

Core Lesson

(TG & SR, Chapter 5)

Homework: “Domain

Vocabulary: Chapters 1–4,”

AP 4.1)

“Inca Engineering”

Core Lesson

(TG & SR, Chapter 6)

Homework: “Summary

of the Maya, Aztec,

and Inca Civilizations”

(TG, Chapter 6, Additional

Activities, AP 2.1)

“The End of Two Empires”

Core Lesson

(TG & SR, Chapter 7)

Homework: “Domain

Vocabulary: Chapters 5–7,”

AP 7.1)

Unit Assessment

(TG)

CKLA

“Personal Narratives” “Personal Narratives” “Personal Narratives” “Personal Narratives” “Personal Narratives”

15INTRODUCTION

Maya, aztec, and Inca cIvIlIzatIons pAcinG Guide

‘s Class

(A total of ten days have been allocated to the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations unit in order to

complete all Grade 5 history and geography units in the Core Knowledge Curriculum Series™.)

Week 1

Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5

Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations

CKLA

Week 2

Day 6 Day 7 Day 8 Day 9 Day 10

Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations

CKLA

16 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

CHAPTER 1

The Maya:

Rainforest Civilization

The Big Question: What do the ruins of the Maya tell you about the importance of

religion to their civilization?

Primary Focus Objectives

✓ Identify the Maya as one of the earliest civilizations in the Americas, located in parts of Mexico and

Central America. (RI.5.2)

✓ Describe how archaeologists have been able to learn more about the Maya civilization by studying

ancient ruins. (RI.5.2)

✓ Explain how religion was linked to Maya society. (RI.5.2)

✓ Understand the meaning of the following domain-specific vocabulary: Mesoamerica, Maya,

civilization, architecture, archaeologist, city-state, temple, hieroglyph, and sacrifice. (RI.3.4)

What Teachers Need to Know

For more background information about the content taught in this lesson, see:

www.coreknowledge.org/about-maya

Note: Prior to conducting the Core Lesson, in which students read Chapter 1 of the Maya, Aztec,

and Inca Civilizations Student Reader, we strongly recommend that you first conduct the activities

titled World Map (AP 1.1); World Geography (AP 1.2); Modern Map of North America, Central America,

and South America (AP 1.3); Geography of the Americas (AP 1.4); Map of the Maya, Aztec, and

Inca Civilizations (AP 1.5); and Geography of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP 1.6) found

in the Teacher Resources section beginning on page 88 and described at the end of this chapter

under Additional Activities. By first providing students with an understanding of the geographical

features of the Western Hemisphere and the relative and absolute locations of the Maya, Aztec,

and Inca civilizations, you will help students more fully understand the world in which these great

civilizationsdeveloped.

17CHAPTER 1 | THE MAYA: RAINFOREST CIVILIZATION

Materials Needed

• World Map (AP 1.1); World Geography (AP 1.2); Modern Map of North

America, Central America, and South America (AP 1.3); Geography of the

Americas (AP 1.4); Map of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP 1.5);

and Geography of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP 1.6) (Teacher

Resources, pages 88 to 93) (Note: Maps 1.3 and 1.5 will be used again in

Chapters 3, 5, 6, and 7.)

• enlarged versions of the maps on AP 1.1, AP 1.3, and AP 1.5

• red and green pencils

Core Vocabulary (Student Reader page numbers listed below)

Mesoamerica, n. a historical region that includes what are today the central

and southern parts of Mexico and the northern parts of Central America (2)

Example: The Maya were an early civilization of Mesoamerica.

Variation(s): Mesoamerican

Maya, n. a group of peoples who have inhabited a region that includes parts

of present-day Mexico and Central America from thousands of years ago to

the present. Before the arrival of Europeans, Maya cities thrived in rainforest

locations between about 200 to 900 CE. (4)

Example: The Maya were skilled builders who constructed great stone

structures.

Variation(s): Mayan, Mayas

civilization, n. a society, or group of people, with similar religious beliefs,

customs, language, and form of government (4)

Example: The Maya civilization thrived for hundreds of years.

Variation(s): civilizations

architecture, n. the style and construction of a building (4)

Example: By studying the architecture, we have learned a great deal about

the Maya.

Variation(s): architect

archaeologist, n. an expert in the study of ancient people and the objects from

their time period that remain, generally including stones, bones, and pottery (5)

Example: In studying the ruins, the archaeologist made many key findings

about the Maya.

Variation(s): archaeologists, archaeology

city-state, n. a city that is an independent political state with its own ruling

government (5)

Example: Thousands of people lived in the city-state of Copán.

Variation(s): city-states

Activity Pages

AP 1.1

AP 1.2

AP 1.3

AP 1.4

AP 1.5

AP 1.6

18 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

temple, n. a building with a religious use or meaning (5)

Example: The priest performed important rituals at the temple.

Variation(s): temples

hieroglyph, n. a picture or symbol representing an idea, an object, a syllable,

or a sound (6)

Example: The scientist figured out what the hieroglyph meant.

Variation(s): hieroglyphs, hieroglyphic

sacrifice, v. to give or to kill something for a religious purpose (9)

Example: The loser of the ball game was doomed to be a human sacrifice.

Variation(s): sacrifices, sacrificed, sacrificial

the core lesson 35 min

Introduce the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations Student Reader 5 min

Distribute copies of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations Student Reader.

Give students a few minutes to examine the reader and flip through its pages,

reading the Table of Contents and headings and looking at the illustrations.

Invite students to call out words or phrases that identify what they see and

what they should expect to be learning about in the unit. Record student

observations on the board or chart paper. Students are likely to mention things

such as buildings, carvings and writing, games, warfare, and cities—all of which

are indicators of the development of civilization.

Introduce the vocabulary word civilization to students: “a society, or group

of people, with similar religious beliefs, customs, language, and form of

government.” Students who studied the Grade 1 Core Knowledge curriculum

have seen this definition before. Review the meaning of the word with

students. Explain that civilizations often include larger populations of people

living in cities, as well as individuals who farm. Characteristics include some

form of government directed by leaders and a common language with some

form of writing, as well as religious beliefs that impact daily life. Ask students

who have studied the Core Knowledge curriculum in earlier grades to think

about civilizations they have studied. Students in Grade 1 studied the Inca,

Aztec, and Maya. Students in Grade 2 studied ancient Greece. Students in

Grade 3 studied ancient Rome.

It’s important for students to recognize that while the Maya civilization reached

its peak from 200 to 900 CE and that this is the time period they will be

learning about in more detail, the Maya culture began to emerge long before

that time. There is evidence that Mesoamerican civilization began to emerge as

early as 1500 BCE.

Tell students that they will be reading about events and developments that

took place in the Americas before the Age of Exploration, a period that began

19CHAPTER 1 | THE MAYA: RAINFOREST CIVILIZATION

in the late 1400s with Christopher Columbus’s encounter with the New World.

We know about this time mainly through the study of objects and buildings

the people left behind. Students will also be writing about the first contacts

between Europeans and these great civilizations. These events are known

mainly based on the writings of the Europeans.

Introduce “The Maya: Rainforest Civilization” 5 min

Students who used this history program in earlier grades have already studied

the rise and fall of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca civilizations. They have also studied

the geography of South America. Remind them how the arrival of Europeans

was a key turning point in the history of the great civilizations of the Americas.

This began with the journey of Christopher Columbus in 1492. After Columbus’s

encounter with what the people of Europe called a “new world,” European

powers raced to send explorers and conquerors to exploit the land, extract

wealth, and expand their empires.

Refer students to the map on page 3. If students have already completed the

Map of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP 1.5) and the Modern Map of

North America, Central America, and South America (AP 1.3), you may want to

ask students to take out these activity pages for reference. You may also want to

display enlarged versions of these activity pages for all students to look at while

they refer to the map on page 3.

Orient students by explaining that the Maya civilization was largely located in

the present-day country of Mexico and also in parts of Guatemala, Honduras,

and Belize. Have students locate these places on the Modern Map of North

America, Central America, and South America (AP 1.3) and circle them in green

pencil. Explain that this is a tropical region, largely covered in rainforest. Ask:

How do you think this environment may have influenced the rise and fall of

these civilizations?

Ask students to first identify characteristics of a rainforest and tropical

environment. Students may respond that rainforests have tall trees and dense

greenery. Tropical environments are generally humid and can experience heavy

rainfall. Students may also note that rainforests are the home to many different

types of animals.

Select five different items (for example a glasses case, car keys, or a piece of fruit)

and place them at the front of the room. Ask students to take a moment to look

at the items. What can they tell about the person who owns these things? Have

students share their responses out loud. Explain to students that much of what

we know about past civilizations comes from the things they’ve left behind.

We have learned many clues about what was important to the Maya from their

buildings. Call attention to the Big Question. Encourage students to look for ways

Maya ruins inform people today about the role of religion in Maya civilization.

Note: it is important to understand the distinction between the words Maya

and Mayan. Explain to students that the word Maya is used as both a noun

Activity Pages

AP 1.3

AP 1.5

20 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

and an adjective that describes the people and the various aspects of their

civilization and culture. An example of the correct use of the word as a noun

is, “The ancient Maya lived in parts of present-day Mexico until about the year

900 CE.” An example of the word as an adjective is, “Archaeologists study Maya

writing to better understand the civilization’s history and culture.” The word

Mayan describes the language spoken by the Maya people. An example of

this word used correctly is, “People living in parts of Mexico continue to speak

Mayan today.”

Guided Reading Supports for “The Maya: Rainforest Civilization” 25 min

When you or a student reads aloud, always prompt students to follow along.

By following along, students may acquire a greater understanding of the

content. Remember also to provide classroom discussion opportunities.

“The Vanishing Civilization,” Pages 2–4

Scaffold understanding as follows:

Invite a volunteer to read the title of this section and the opening paragraph.

CORE VOCABULARY—Note the term Mesoamerica when it is encountered

in the text. Explain to the class that this term refers to a historical region, the

place where certain civilizations emerged, and it is not used to describe or

locate any modern-day place.

SUPPORT—Help students recognize that this illustration is a map showing

the land that is today Mexico, Central America, and the northern part of

South America.

Ask students to read quietly to themselves the remainder of this section

up to the next section entitled “Ruins in the Rainforest.”

After students read the text, ask the following questions:

LITERAL—The text refers to a key question about the Maya civilization.

What is the mystery?

» The mystery is the disappearance of the Maya cities that were part of

the thriving Maya culture from 200 to 900 CE.

SUPPORT—The title of this section is “The Vanishing Civilization.” What is

a synonym for vanishing?

» Disappearing is a synonym for vanishing.

INFERENTIAL—Why do you think the disappearance of the Maya cities is

considered a mystery?

» The cities were thriving and strong, but then they ceased to exist.

Nobody is sure why this happened.

NORTH AMERICA

Atlantic Ocean

The Maya

The Aztec

CENTRAL

AMERICA

SOUTH AMERICA

The Inca

N

S

E

W

Pacic Ocean

3

In the centuries before Europeans came to the Americas, great civilizations thrived in present-day

Mexico, Central-America, and South America. These included the Maya, Az tec, and Inca.

G5_U2_Chap01_SE.indd 3 7/1/16 2:02 PM

Page 3

NORTH AMERICA

Atlantic Ocean

The Maya

The Aztec

CENTRAL

AMERICA

SOUTH AMERICA

The Inca

N

S

E

W

Pacic Ocean

Chapter 1

The Maya: Rainforest

Civilization

The Vanishing Civilization Do you

like mysteries? Try this one: More

than a thousand years ago, a great

civilization of American Indian peoples

built cities across Mesoamerica—an

area today that is made up of parts

of Mexico and Central America. They

built stone temples and pyramids that rose far above the

forest treetops.

The Maya, one group of native peoples,

discovered important mathematical ideas.

They also studied the movements of the

stars. Using this knowledge, the Maya

made a calendar almost as accurate as the

one we use today. Then, after hundreds

of yearsof growth, many key elements of

Mayacivilization disappeared. The people abandoned their

once-thriving cities. This great urban society and many of

2

The Big Question

What do the ruins

of the Maya tell you

about the importance

of religion to their

civilization?

Vocabulary

Mesoamerica, n. a

historical region that

includes what are today

the central and southern

parts of Mexico and

the northern parts of

Central America

G5_U2_Chap01_SE.indd 2 7/1/16 2:02 PM

Page 2

21CHAPTER 1 | THE MAYA: RAINFOREST CIVILIZATION

LITERAL—What happened to the people and culture that built the great

Maya cities?

» Archaeologists and historians are unsure as to what happened to the

Maya people. Their historical records stop around the year 900 CE, and

their temples and buildings fell into ruin.

INFERENTIAL—The text says that the brief history of the disappearance

of the Maya’s cities reads like a movie plot. What do you think this means?

» The disappearance of the cities was abrupt and in some sense

surprising, but it opens up key research questions for archaeologists.

SUPPORT—Movie plots are often fiction and have unexpected events

and endings. How might the disappearance of the Maya cities be similar?

» Answers may vary, but students’ responses should show they understand

that the disappearance of Maya cities may have a cause or causes that no

one has yet thought of.

“Ruins in the Rainforest” and “Mysterious Writing,” Pages 4–7

Scaffold understanding as follows

CORE VOCABULARY—Choose a volunteer to read the first two

paragraphs under the heading “Ruins in the Rainforest,” on pages 4

and 5. Discuss the meanings of the words architecture and archaeologist

when they are encountered.

Ask students to refer to AP 1.5 and point to the city of Copán. Ask if Copán

is located in North America (Mexico), Central America, or South America.

CORE VOCABULARY—Choose a volunteer to read the second full

paragraph on page 5. Note the term city-state. Point out that this term is

a compound word made up of two words—city and state. Ask students to

examine the definition of the word included in their reader to explain the

relationship between the two words that make it up.

CORE VOCABULARY—Have the students read the last paragraph

beginning on the bottom of page 5 and continuing on page 6 to

themselves. Point out the term temple. Use the illustration on the page to

help define the term temple. Point out to students that the temple featured

in the image is a pyramid. It has sloped sides, and the building on top is

the temple.

CORE VOCABULARY—Call attention to the term hieroglyphs in the next

section, “Mysterious Writing,” and clearly pronounce the word for students.

Explain that Maya writing was often carved into stone structures, like the

stairway shown in the picture. Have the students read the entire section

of “Mysterious Writing” on pages 6–7 to themselves.

5

about their findings. Their tales and drawings

inspired worldwide interest in the history of

the Maya.

Since the mid-1800s, archaeologists

and other experts have continued to

study these remarkable people. Recent

breakthroughs in research have revealed

just how much the Maya accomplished.

Let’s take a closer look at what we know

about them and what still remains

amystery.

At its peak, the Maya civilization included

a large group of city-states that were

allied with, fought, and conquered each

other. These cities were located on the Yucatán Peninsula

in what is today southeastern Mexico and the countries

of Guatemala,

Honduras, and Belize.

Archaeologists believe

that Maya civilization

reached its greatest

extent between about

200 and 900 CE.

The largest buildings

in Maya cities were

pyramids that also

served as temples.

Maya pyramids were grand monuments that reached

toward the sky.

Vocabulary

archaeologist, n. an

expert in the study

of ancient people

and the objects from

their time period that

remain, generally

including stones and

bones, and pottery

city-state, n. a

city that is an

independent political

state with its own

ruling government

temple, n. a building

with a religious use or

meaning

G5_U2_Chap01_SE.indd 5 7/1/16 2:02 PM

Page 5

6

These structures served religious purposes. From their size, it is

clear that religion was a key part of Maya life. Maya pyramids rose

high above the surrounding treetops. Maya pyramids were some

of the tallest structures in the Americas until 1902. That year, the

twenty-two-story Flatiron Building was constructed in New York City.

Mysterious Writing

Archaeologists found hieroglyphs

(/hie*roe*glifs/) carved into Maya buildings

and monuments. The Temple of the

Hieroglyphic Stairway stands in Copán. A

climb up this staircase is a journey back in

time. Each of the sixty-three steps has a story

to tell. Carved symbols called

glyphs name all of the rulers of

Copán. The glyphs also explain

their military victories. The

American explorers who visited

this site in 1839 marveled over

these carvings. They could not,

however, figure out what the

symbols meant. For a long time,

neither could any other experts.

Hieroglyphs are like a code.

You must crack the code

to read the messages.

Mayan hieroglyphs are

complicated and include

Vocabulary

hieroglyph, n. a

picture or symbol

representing an idea,

an object, a syllable,

or a sound

The Mayan hieroglyphs were carved into

each step of this stairway.

G5_U2_Chap01_SE.indd 6 7/1/16 2:03 PM

Page 6

4

its traditions were mysteriously

transformed, although Mayan-speaking

people continue in this part of

Mesoamerica to the present.

This may sound like the plot of a science-

fiction movie, but it isn’t. In fact, it is a short

history of the Maya (/mah*yuh/), one of

the first great civilizations of the Americas

that flourished between 200 and 900 CE.

Ruins in the Rain Forest

In 1839, two American explorers heard stories

of mysterious ruins in the rain forests of

Central America. Curious, they set out to see

for themselves. The two men first explored

the remains of the

city of Copán

(/koh*pahn/) in

the present-day

country of

Honduras. From the architecture, it

was clear the ruins had been left by

an ancient and advanced civilization.

The two Americans continued their

journey, exploring many other ruins.

Then, they returned to the United

States and wrote a best-selling book

Archaeologists still study the remarkable Maya.

Vocabulary

architecture, n. the

style and construction

of a building

Vocabulary

Maya, n. a group of

peoples who have

inhabited a region

that includes parts of

present-day Mexico and

Central America from

thousands of years

ago to the present.

Before the arrival

of Europeans, Maya

cities and civilization

thrived in rainforest

locations between

about 200 and 900CE.

civilization, n. a society,

or group of people,

with similar religious

beliefs, customs,

language, and form of

government

G5_U2_Chap01_SE.indd 4 7/1/16 2:02 PM

Page 4

22 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

After students read the section, ask the following questions:

LITERAL—What did the two American explorers find in the rainforest

in1839?

» The explorers heard about ruins located in Copán. They found the

Maya city and explored the area. They wrote a book that sparked

worldwide interest in the civilization.

LITERAL—How was the Maya civilization organized?

» The Maya civilization was broken into city-states. The Maya people

spoke a common language, but they were not a unified country.

Instead, city-states allied with each other but also went to war and

conquered each other.

LITERAL—Why were pyramids important in Maya culture?

» Pyramids were constructed as platforms for large temples that were

used for religious purposes.

LITERAL—In what way are Maya hieroglyphs like a code?

» In hieroglyphic writing, each symbol represents, or is code for, something

else. You can only understand the writing if you know the code.

LITERAL—Were the original American archaeologists able to translate and

understand the meaning of the hieroglyphs? Why or why not?

» The original archaeologists could not understand the meaning of

the hieroglyphs. It was like cracking a very complex code. Once later

archaeologists determined the meaning of the “code,” however, they

were able to learn much about the Maya civilization.

INFERENTIAL—Why do you think cracking the Maya code has enabled

experts to learn a lot about the Maya?

» When people gained the ability to read Maya hieroglyphs, they could

read what had been recorded during the time period when Maya

civilization actually existed. These written records provided much

information about Maya culture and history.

CHALLENGE—The Maya used hieroglyphs as a way to record events,

history, and religious beliefs. What other civilization do you know of that

used hieroglyphs as its form of writing?

» The ancient Egyptians also used hieroglyphs to write.

7

more than eighthundred symbols. It wasn’t until the 1960s that

archaeologists began to crack the code with early computers.

Since then, we have learned a great deal about the ancient Maya.

Breath on a Mirror

We have learned that daily life for the Maya revolved around family,

farming, and service to the gods. No person or group took any

important action without consulting the gods. Priests decided

which days were best for planting a field, starting a war, or building

a hut. The Maya believed the gods were much wiser than humans.

According to Maya legend, the first people could see everything.

The creator gods decided that this gave people too much

power. So the gods decided to limit human sight and power.

The Maya sacred book, the Popol Vuh, explains that the gods

purposely clouded human understanding. As a result, a human’s

view of the world is unclear. The Popol Vuh explains that human

understanding is “like breath on a mirror.”

Serious Play

Breaking the hieroglyph code also helped archaeologists understand

how the Maya spent some of their time. A specific kind of ball court

can be found in many Maya cities. Archaeologists were puzzled

about these courts, which varied in size. Some were the size of

volleyball courts. Others were larger than football fields.

Archaeologists now think the Maya played a game called pok-ta-

pok in these courts. They believe the goal of pok-ta-pok was to

drive a solid rubber ball to a specific place on the opponents’ side

G5_U2_Chap01_SE.indd 7 7/1/16 2:03 PM

Page 7

23CHAPTER 1 | THE MAYA: RAINFOREST CIVILIZATION

“Breath on a Mirror” and “Serious Play,” Pages 7–9

Have students read the section “Breath on a Mirror” independently.

After students read the text, ask the following questions:

LITERAL—Why, according to Maya legend, did the gods limit human

understanding?

» The gods limited human understanding in order to make humans less

powerful.

INFERENTIAL—How does the phrase “like breath on a mirror” explain the

Maya belief about human understanding?

» When a person breathes on a mirror, it makes it hard to see details in

the image it’s reflecting. In the same way, people’s ability to see the

world clearly and in detail is obscured by the gods.

Scaffold understanding as follows:

CORE VOCABULARY—Call attention to the word sacrifice on page 9,

found in the section “Serious Play,” and discuss its meaning. Help students

understand that the Maya believed that human sacrifice was the greatest

gift that could be made to the gods they worshipped.

Have students refer to Map of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP 1.5),

and locate Chichén Itzá on the map. Have students volunteer to read

the section “Serious Play” out loud.

SUPPORT—After students read the second full paragraph on page 8, call

attention to the idiom “the stakes are high.” Explain to students that when

the stakes are high, a person has a lot to lose.

SUPPORT—Call attention to the word spectators in the third full paragraph

on page 8. Explain that spectators are people who go to an event to watch.

The Maya watched pok-ta-pok much like people today go to watch games

such as football, baseball, or basketball.

SUPPORT—In the fifth full paragraph of page 8, explain the context of

the statement, “There is no whistle for a foul.” Many students may play a

sport or have seen one in person or on television. The Maya did not have

referees to make sure the athletes were playing fairly in pok-ta-pok. This

shows that they were probably very ruthless while playing.

After students read the text, ask the following questions:

LITERAL—What is pok-ta-pok?

» Pok-ta-pok is a ball game that the Maya played on the ball courts that

are found at the sites of many Maya cities.

8

of the court. The balls were heavy. Also, players were not allowed

to use their hands or feet! Experts think players may have had to

use hips, elbows, knees, or other body parts to score a goal.

The court at the Maya site of Chichén Itzá (/chee*chen/eet*sah/) is

still visible today. This court had stone rings, and a team could win

the game by driving the hard rubber ball through the ring on the

other team’s side of the court. If you use your imagination, you can

picture what a pok-ta-pok game might have looked like.

Imagine big, strong pok-ta-pok players stepping out onto the

court. They wear leather helmets and pads to protect themselves.

You can also see that they are worried. They know that the stakes

are high. Pok-ta-pok is a game with religious meaning. The Maya

think of it as a battle between good and evil. The only way to find

out who’s good and who’s evil is to see who wins the game.

Hundreds of spectators have gathered. They see the game as

meaningful for their world and as a way of honoring the gods.

When the game begins, the sound of the bouncing ball is added

to the cheers. Pok, pok, pok! goes the hard rubber ball as it hits the

ground and bounces off the walls of the court.

One player begins driving the ball up the court with his elbows,

knees, and chest. Then, whack! Another player slams into him and

knocks him to the ground. There is no whistle for a foul. In fact,

there are very few rules in pok-ta-pok! The game continues until

someone finally scores. The side that scores wins the game.

The winners of pok-ta-pok games were considered to be the “good”

ones. Sometimes they were rewarded with clothing andjewelry.

G5_U2_Chap01_SE.indd 8 7/1/16 2:03 PM

Page 8

7

more than eighthundred symbols. It wasn’t until the 1960s that

archaeologists began to crack the code with early computers.

Since then, we have learned a great deal about the ancient Maya.

Breath on a Mirror

We have learned that daily life for the Maya revolved around family,

farming, and service to the gods. No person or group took any

important action without consulting the gods. Priests decided

which days were best for planting a field, starting a war, or building

a hut. The Maya believed the gods were much wiser than humans.

According to Maya legend, the first people could see everything.

The creator gods decided that this gave people too much

power. So the gods decided to limit human sight and power.

The Maya sacred book, the Popol Vuh, explains that the gods

purposely clouded human understanding. As a result, a human’s

view of the world is unclear. The Popol Vuh explains that human

understanding is “like breath on a mirror.”

Serious Play

Breaking the hieroglyph code also helped archaeologists understand

how the Maya spent some of their time. A specific kind of ball court

can be found in many Maya cities. Archaeologists were puzzled

about these courts, which varied in size. Some were the size of

volleyball courts. Others were larger than football fields.

Archaeologists now think the Maya played a game called pok-ta-

pok in these courts. They believe the goal of pok-ta-pok was to

drive a solid rubber ball to a specific place on the opponents’ side

G5_U2_Chap01_SE.indd 7 7/1/16 2:03 PM

Page 7

Nearly every Maya city had at least one ball court.

9

But what do you think happened to the

losers? Experts believe that at least in

certain situations, some of them were

offered as sacrifices to the gods.

Human sacrifice was a part of the Maya religion. Maya priests

sought to please the gods by offering sacrifices atop the pyramids.

No wonder the pok-ta-pok players looked worried as they walked

onto the court!

Pok-ta-pok and human sacrifice are two parts of Maya life that we

have learned about from Maya hieroglyphs. In the next chapter,

you will learn more about the scientific achievements and daily life

of the ancient Maya.

Vocabulary

sacrifice, v. to give or

to kill something for a

religious purpose

G5_U2_Chap01_SE.indd 9 7/1/16 2:03 PM

Page 9

24 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

SUPPORT—Was pok-ta-pok just a game or sporting event to entertain the

Maya who watched the game?

» No, the game had religious meaning.

LITERAL—In what way did pok-ta-pok have religious significance to the Maya?

» The game was seen as a contest between good and evil. The winners

were considered the “good,” and the losers were considered “evil.”

LITERAL—What was the purpose of the Maya practice of sacrificing

human beings?

» The Maya sacrificed humans in the hopes of pleasing the gods.

EVALUATIVE—Why do you think the Maya allowed the outcome of a

game to determine who lived or died?

» Perhaps they believed the outcome of the game was actually in the

hands of the gods.

Timeline

• Show students the Chapter 1 Timeline Image Card. Read and discuss the

caption, making particular note of any dates.

• Review and discuss the Big Question: “What do the ruins of the Maya tell

you about the importance of religion to their civilization?”

• Post the first image card as the very first image on the far left side of the

Timeline, under the date referencing 1500 BCE.

checK for understAndinG 10 min

Ask students to:

• Write a short answer to the Big Question, “What do the ruins of the Maya

tell you about the importance of religion to their civilization?”

» Key points students should cite include: Maya ruins contain writings

and other remnants of their central religious practices, including

pyramids and temples built for religious ceremonies, and ball courts

on which the Maya played the sacred ball game that helped determine

who would be sacrificed to the gods.

• Choose one of the Core Vocabulary words (Mesoamerica, Maya, civilization,

architecture, archaeologist, city-state, temple, hieroglyph, or sacrifice), and

write a sentence using the word.

To wrap up the lesson, ask several students to share their responses.

25CHAPTER 1 | THE MAYA: RAINFOREST CIVILIZATION

Additional Activities

Background for Teachers: Before beginning any of the geography activities,

review What Teachers Need to Know on pages 4–6 of the Introduction. The

geography activities are best introduced prior to teaching the Chapter 1 Core

Lesson, so they can serve as an introduction for students to the geography

of the places in which the Maya, Aztec, and Inca civilizations developed

andthrived.

World Geography (RI.5.7, RI.5.9) 10–20 min

Materials Needed: Display copy of (1) World Map (AP 1.1). Sufficient printed

copies of the World Map (AP 1.1) and World Geography (AP 1.2) found in the

Teacher Resources section (pages 88 and 89).

Note to Teachers: Time allotted for this activity varies based on what work you

choose to assign in class or as homework. Plan for ten minutes of classroom

time to work through the World Map (AP 1.1) and an additional ten minutes if

you choose to assign World Geography (AP 1.2) during class.

Display the enlarged World Map (AP 1.1) for all students to see. Point first to

the compass rose, and review each of the cardinal directions—north, south,

east, and west—relative to the map. Then point to the United States and the

approximate location of the state in which your students live to identify their

current location.

Next, point to each of the continents in the following order, asking students

to verbally identify each continent: North America, South America, Antarctica,

Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. Review the names of various world oceans,

as well as the use of the map scale.

Ask students to complete the questions on the World Geography page (AP 1.2).

This can also be assigned as homework, if preferred.

Geography of the Americas (RI.5.7, RI.5.9) 10–20 min

Materials Needed: Display copy of (1) Modern Map of North America, Central

America, and South America (AP 1.3). Sufficient printed copies of the Modern

Map of North America, Central America, and South America (AP 1.3) and

Geography of the Americas (AP 1.4), found in Teacher Resources (pages 90 and

91). Green, brown, and blue colored pencils or crayons should also be made

available to students.

Note to Teachers: Time allotted for this activity varies based on what work you

choose to assign in class or as homework. Plan for ten minutes of classroom

time to work through the Modern Map of North America, Central America, and

South America (AP 1.3) and an additional ten minutes if you choose to assign

Geography of the Americas (AP 1.4) during class.

Activity Pages

AP 1.3

AP 1.4

Activity Pages

AP 1.1

AP 1.2

26 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

Tell students that during Unit 2 they will be learning about the Maya, Aztec,

and Inca. They will focus primarily upon countries and areas included in the

southern part of North America, often referred to as Central America, and in

South America.

Now display the enlarged Modern Map of North America, Central America,

and South America (AP 1.3), and distribute copies to all students. Explain that

students are now looking at a map that shows the borders of the modern-day

countries of North America, Central America, and South America in greater

detail. Begin by identifying the country of Mexico, noting that it is in North

America, just south of the United States. Have students circle the same area on

their own maps. Then ask students to name and point to the following labeled

areas: the Yucatán Peninsula, Guatemala, Honduras, and Belize. Have students

color this area on the map green.

Next point out the continent of South America. Have students name and point

to the Andes Mountains, Peru and the city of Cuzco, and the largest countries

in South America (Brazil and Argentina). Have students color the Andes

Mountains brown and have them draw a star next to Cuzco to show that it is an

important city.

Ask students to identify the color typically used to depict large bodies of water

on maps (blue). Take time to point out the following bodies of water on the

displayed map as students use a blue pencil or crayon to shade these areas on

their own maps: Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, Amazon River,

and Pacific Ocean.

Now ask students to complete the questions on AP 1.4. These questions can

also be completed for homework.

Tell students to put this modern map of North America, Central America, and

South America aside but to keep it available for reference, if needed, during the

remaining activities.

Geography of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (RI.5.7, RI.5.9) 20–30 min

Materials Needed: Display copies of (1) Map of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca

Civilizations (AP 1.5) and (2) Modern Map of North America, Central America,

and South America (AP 1.3). Sufficient printed copies of the Map of the Maya,

Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP 1.5) and Geography of the Maya, Aztec, and

Inca Civilizations (AP 1.6) found in Teacher Resources (pages 92 and 93). Green,

orange, and yellow colored pencils or crayons should also be made available

tostudents.

Note to Teachers: Time allotted for this activity varies based on what work you

choose to assign in class or as homework. Plan for twenty minutes of classroom

time to work through the Map of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP 1.5)

and an additional ten minutes if you choose to assign Geography of the Maya,

Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP 1.6) during class.

Activity Pages

AP 1.5

AP 1.6

27CHAPTER 1 | THE MAYA: RAINFOREST CIVILIZATION

Display the map of the Map of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP1.5), and

distribute copies to all students. Explain to students that this is a map that shows

the same land areas of North America, Central America, and South America as

the previous map but that it depicts these areas at an earlier time in history. Tell

students that they will be studying the historical period represented by the map,

so it will be useful to understand both the geography of this area and where

the different civilizations they will study were located. Explain that the period of

history began before the Europeans arrived in the Americas and before the kinds

of political boundaries we recognize today were established.

Point out shaded areas of the map and the key that indicates that these shaded

areas represented the territories that were part of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca

civilizations. Students who used the Core Knowledge curriculum in Grade1 have

already studied these civilizations. Tell students that they may refer to their maps of

North America, Central America, and South America as you discuss the following:

• On the displayed Map of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations (AP 1.5),

point to the shaded area representing the Maya civilization. Ask students to

identify the name of this civilization and lightly shade the area of the Maya

civilization green.

Then ask students to refer to the Modern Map of North America, Central

America, and South America to describe the modern-day locations that the

Maya civilization of 200 to 900 occupied. (The Maya civilization was centered

on the Yucatán Peninsula of modern-day Mexico and also occupied parts of

Guatemala, Honduras, and Belize.)

• Point to the shaded area representing the Aztec civilization. Ask students to

identify the civilization and to describe the modern-day locations that the

Aztec occupied. (The Aztec occupied much of what is modern Mexico.) Have

students lightly shade the area of the Aztec civilization orange.

• Point to the shaded area representing the Inca civilization. Ask students to

identify the civilization. Then ask students to refer to the Modern Map of

North America, Central America, and South America (AP 1.3) to describe the

modern-day locations that the Inca occupied. (The Inca occupied much of

what is present-day Peru, as well as parts of Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile,

and Argentina.) Have students lightly shade the area occupied by the Inca

yellow. Have students fill in the map key with each respective color that

represents the civilizations on the map.

• Ask students to identify the key geographic features that dominated the

historical empire of the Inca (the Andes Mountains, as well as the coast of

South America).

Have students complete the Geography of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca Civilizations

(AP 1.6). Depending on your students’ map skills, you may choose to do this

as a whole-class activity so that you can scaffold and provide assistance. You

may also choose to have students work with partners or small groups or assign

AP1.6 for homework. If students complete AP 1.6 with partners or small groups,

28 GRADE 5 | UNIT 2 | MAYA, AZTEC, AND INCA CIVILIZATIONS

orfor homework, be sure to review the answers to the questions with the entire

class. Be certain that students save these activity pages for future reference

throughout their study of the unit on the Maya, Aztec, and Inca civilizations.

Visit Copán 35 min

Take this opportunity to reinforce the domain-specific vocabulary words

city-state and archaeologist by introducing students to the ruins of one of the

most spectacular Maya cities, Copán.

Background for Teachers: Prior to discussing Copán with students, read the

Encyclopaedia Britannica article about Copán. This primary unit link will take

you to the Core Knowledge web page, where specific links to background

information about Copán, a video for a virtual tour, and a gallery of images may

be found.

www.coreknowledge.org/hgca-g5-maya-aztec-inca-activities

Discuss City-States

Tell students that you are going to explore the idea of a city-state in more detail.

Observe that this term is made up of two words. A city is a large settlement

of people. A state is an organized community that is united under a single

government. A city-state, therefore, is a city that functioned as an independent

state, like a small country. The Maya civilization was actually a collection of