1

Using Music to Teach Phonological Awareness

by

Sophia Ann Thompson

A thesis submitted to the faculty of

Wittenberg University

In partial fulfillment of the requirements for

DEPARTMENTAL HONORS IN EDUCATION AND UNIVERSITY HONORS

Wittenberg University

May 2024

2

Abstract

In this study, I analyzed the ways music can teach phonological awareness to contribute

to student engagement and literacy achievement. In recent years, literacy achievement has fallen

short. With phonological awareness skills contributing to the success of a reader, an

improvement needs to be found. Through the completion of teacher interviews and assessing the

different outcomes between phonological awareness lessons with and without music, I was able

to determine that music has the capability to improve a student’s literacy skills. These findings

contribute to the field of education by highlighting the need for supplemental instruction and the

power that music integration into core content areas can have for students. This study provides

insights for future research that can be done in this field to achieve more positive educational

outcomes.

3

Contents

Using Music to Teach Phonological Awareness .................................................................................1

Abstract ............................................................................................................................................2

Chapter One .....................................................................................................................................4

Introduction......................................................................................................................................4

Chapter Two .....................................................................................................................................6

Literature Review .............................................................................................................................6

Music in Education .......................................................................................................................6

Phonological Awareness ................................................................................................................8

Reading Success and Phonological Awareness ............................................................................9

Typical Phonological Awareness Instruction ............................................................................. 10

Current State of Literacy Achievement ...................................................................................... 11

Music and Phonological Awareness ............................................................................................. 13

Chapter Three ................................................................................................................................ 16

Method ........................................................................................................................................... 16

Background................................................................................................................................. 16

Teacher interviews and beliefs on music integration ................................................................... 17

Lesson Plans ................................................................................................................................ 18

Chapter Four .................................................................................................................................. 21

Results ............................................................................................................................................ 21

Teacher Interviews ...................................................................................................................... 21

Lesson Observations.................................................................................................................... 26

Chapter Five ................................................................................................................................... 31

Discussion ....................................................................................................................................... 31

Teacher Interviews ...................................................................................................................... 31

Consonant Blend Lessons ............................................................................................................ 33

Limitations .................................................................................................................................. 35

Future Research .......................................................................................................................... 36

References....................................................................................................................................... 37

4

Chapter One

Introduction

Literacy is a huge part of a child’s education. From the very first year that they are in school,

they are learning important literacy skills. Learning these skills is a key indicator of someone’s

ability to be literate as they get older. A huge piece of this puzzle is phonological awareness. This

is the ability to hear, identify, and manipulate the sounds of spoken language (Scarborough,

2002). This is a critical skill that everyone needs to develop in elementary school. In recent

years, literacy achievement has decreased and new ways to teach skills may be worth exploring

to try and close the gap. A way that this can be done is through music. Music within education

has typically been a “special” that students go to once a week for a short period of time.

Research has proven that music is able to enhance one’s learning of other skills such as

phonological awareness (Bolduc, 2009; Hurwitz et. al, 1975; Wiggins, 2007). The effects of

incorporating music intentionally into the general education classroom could help close the gap

in literacy achievement for the state of Ohio.

Given the gap in literacy achievement, this study aimed to analyze whether or not music

had an effect on the learning of phonological awareness skills in relation to academic

performance and engagement. I conducted my study at a small rural school in Ohio. The first

part of my study consisted of interviews with both grade-level teachers and the music teacher at

the school to get an idea of what is already in place for phonological awareness instruction and

music integration. Then, I conducted a series of lessons in a second-grade classroom on an

important phonological awareness skill, consonant blends. Some of these lessons used music as

an aid to support the students’ acquisition of knowledge and the other lessons did not use music.

5

The results were qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed to see the effects that music has on

instruction.

I chose to study this topic because of how important phonological awareness is to student

literacy achievement. There is also a natural connection between both phonological awareness

and music. Some phonological awareness skills that we see frequently in music are alliteration

and rhyming. Alliteration is when the same consonant sound is present in multiple words that are

near each other like in the common phrase, “Sally sold seashells by the seashore.” (Invernizzi et.

al, 2023). Rhyming occurs when words have the same middle and ending sound. For example,

cat, bat, and hat (Invernizzi et. al, 2023). Because of this connection, it could potentially be more

relevant to students, engage students, and help to make their learning more concrete. Outside of

these skills, there are multiple other phonological awareness skills that are important to literacy

success in students that could be taught using music. I aimed to discover whether or not music

could be used as a tool to make gains in the literacy achievement gap that is currently present.

The primary hypothesis of this study was that using music in phonological awareness instruction

would result in increased student engagement and achievement.

6

Chapter Two

Literature Review

In this study, I wanted to identify whether or not music was beneficial in classrooms

while teaching phonological awareness skills. Although many teachers may be using music in

their classroom, there is very limited data available on specific instructional practices for

teaching phonological awareness using music which shows the importance of analyzing the two

domains separately. In this chapter, I will go through three different categories relevant to the

study. First, there will be background knowledge given on the current state of music in the

schools both within and outside of the music classroom. Then, I will discuss the importance of

phonological awareness on early literacy skills. Lastly, I will focus on the intersection of music

and phonological awareness instruction.

Music in Education

Typically, we see music offered to elementary students once a week that students attend

for a small amount of time. This is typically around thirty minutes. It is separate from the general

education classroom and typically focuses on music skills such as singing or playing an

instrument. The music teacher typically teaches a wide range of grades in elementary school and

covers multiple areas. This is also seen in the Ohio Standards for music. The standards begin as

very basic musical ideas such as K.1.CR, which states that students experience a wide variety of

vocal and instrumental sounds and then progresses to 1.3.CR where students compose simple

rhythms (Ohio Fine Arts Learning Standards, 2022). As the students increase in age, the music

teachers typically teach one discipline. This is mostly seen in middle school and high school

when they teach band, choir, or orchestra. These standards are more complex and consist of

students composing melodies using accompaniment and specific forms of notation. In

7

elementary music, standards are general music and middle and high school standards are more

specific.

In a research study done by Ling-Yu Liza Lee (2009), it was found that when combining

music into other skills, students were more motivated to learn the material. In this particular

study, the researcher taught three- to four-year-olds four different songs throughout a twenty-

four-week period with two lessons a week that focused on learning vocabulary in the English

language. Lee recognized how important language and communication skills are to the age group

of students she was focused on and incorporated music in order to teach these skills. Not only are

these students learning their native language, but Lee used music to teach the concepts in a

foreign language, in this case English. In this study, they found that this benefitted the students in

multiple ways. Students were learning English and vocabulary better with music. Some

vocabulary that researchers focused on were high and low, soft and loud, stop and go, and fast

and slow. Students made connections from the songs to the English language. Music forms a

bridge for students between the two hemispheres of their brain and allows them to work together

to promote complex thinking (Lee, 2009). Students in this study were connecting their

knowledge of music and the sounds to their newfound knowledge of the English vocabulary and

language.

In another study, researchers investigated the effect that music has on students’ emotional

development (Blasco-Magraner et. al, 2021). Emotional development is important to students

and includes their ability to communicate and collaborate with those around them. In traditional

school settings, students are exposed to these opportunities daily which makes emotional

development crucial. In this study, researchers analyzed several areas of music used in school.

They found that students who were exposed to music were better at recognizing their emotions.

8

They found the same results in emotional regulation. When looking at the effect on school tasks,

researchers found that when video clips and background music were used, students had a more

positive mood. These students subsequently performed better on reasoning activities, had higher

levels of creativity, and higher motivation.

Phonological Awareness

Phonological awareness refers broadly to the many different skills that involve the ability

to manipulate and hear the sounds of spoken words (Scarborough, 2002). Many skills need to be

acquired for students to have phonological awareness. Students need to know that an individual

sound in a word is called a phoneme. Within phonological awareness, students are manipulating

and hearing these sounds. These sounds do not always directly correlate the number of letters in

the word they may be writing. For example, the word ‘chip’ has four letters but only three

phonemes because CH has two letters to represent one phoneme. As students progress forward in

their knowledge of phonemes and graphemes, the written representation of a sound, they will be

able to decode, or read, with more accuracy and encode, or spell, with more accuracy.

Phonological awareness encompasses many different skills such as rhyming, alliteration,

segmentation, syllables, deletion, isolation of phonemes, and blending. Phonological awareness

is important to reading success and is a skill that begins to develop early in a child’s life and

develops into early adulthood (National Reading Panel, 2002).

Emergent Literacy is the first stage of literacy development. Emergent literacy skills are

skills that students start to develop from their first interactions with print. These skills are pre-

reading skills that prepare the student for further skills that are essential to becoming literate.

Phonological awareness, print concepts, alphabet knowledge, and literate language are all part of

emergent literacy (Eccles et. al., 2021). Phonological awareness is an integral part of emergent

9

literacy and continues to develop throughout elementary school. The skills developed here are

predecessors of a successful reader. Students’ ability to blend words together when given

phonemes or identify the number of phonemes in a word relies heavily on the knowledge that

they developed during emergent literacy. During that time, students were exposed to print and

letters that they are now seeing used in the words around them. This permits them to form

connections between graphemes and phonemes. This begins as larger segments of sounds such as

words and syllables and further breaks down into individual phonemes (Whitehurst & Lonigan,

2001). Throughout emergent literacy, students are learning the foundation of reading success that

will continue to develop.

Reading Success and Phonological Awareness

The science of reading consists of decades worth of research on the importance of

foundational skills to develop into successful readers. In a study done by Lea and Ely Kozminsky

(1995), they found that early phonological awareness instruction in kindergarten had effects on the

reading success of third graders. In the study, half of the students received a phonological

awareness program while the other students maintained the typical instructional methods being

offered by the school. They were tested in kindergarten and first grade for phonological awareness

skills using a standard phonological awareness screener (PAT). This assessment looks at many

skills under the umbrella of phonological awareness such as rhyme detection, sentence

segmentation, syllable synthesis, syllable segmentation, phoneme isolation, phoneme deletion,

phoneme segmentation, and phoneme synthesis. In each of these tasks, the average score for the

experimental group was higher than those of the control group. The two most notable tasks were

those of phoneme deletion and isolation. In deletion tasks, the experimental group was averaging

a 1.50 and the control group a 0.67. In isolation, the experimental group averaged 2.41 while the

10

control group averaged 1.07. Researchers pointed out that these two skills explained 70% of the

comprehension scores they analyzed later. Overall, the PAT scores between the two groups had a

difference of nearly seven points with the group receiving phonological awareness instruction

showing more success (Kozminsky & Kozminsky, 1995).

In the same study, the researchers analyzed the comprehension abilities of the two sets of

students. Comprehension is the ability to recall what they have read in a text. This is important

because understanding what they have read will allow them to use their new knowledge elsewhere.

Before they can read, they need the basic knowledge of words and their parts. This is what

phonological awareness instruction leads them to. In the study, they found a significant difference

in the control group and experimental group in comprehension of third grade texts. After their

kindergarten year, students took the comprehension test. The experimental group who received the

phonological awareness instruction scored an average of 20.0 while the control group scored an

average of 15.33. In third grade, the same students were given the same comprehension

assessment. The experimental group scored an average of 40.60 and the control group scored an

average of 36.93 (Kozminsky & Kozminsky, 1995). These results show that the group who

received phonological awareness instruction in kindergarten was now able to comprehend the texts

better than the other group. The effects of instruction in kindergarten were still showing a

difference two years later. The students who had higher phonological awareness could in turn read

better and comprehend text better as they got older.

Typical Phonological Awareness Instruction

Phonological awareness instruction needs to occur explicitly in order for students to

begin thinking about individual phonemes more intentionally (Scarborough, 2022). Although

many students understand the concept of syllables, rhyming, and alliteration, they need explicit

11

instruction from a teacher. This will assist in their development of phonological awareness and

their ability to read. Special education professors Chard and Dickinson (1999) analyzed the

continuum of phonological awareness instruction given the complexity of skills. Students

progress in complexity in this order: rhyming, sentence segmentation, syllable segmentation and

blending, onset-rime segmentation and blending, and finally blending and segmenting individual

phonemes. They also give guidance on how to teach different levels of ability within those tasks.

While all students may be working on rhyming, some may be ready for rhyming in multi syllable

words, while others are focusing on one syllable words. Chard and Dickinson state that

phonological awareness instruction could begin as early as age four (1999). Instruction across the

ages may look different as they get more complex but should be engaging and age appropriate.

Some strategies include using colorful picture cards, games, props, etc. Chard and Dickonson

conclude their research by outlining that phonological awareness instruction has the ability to

help fill gaps for students who have reading disabilities (1999).

Current State of Literacy Achievement

The state of Ohio publishes a state report card each year outlining the achievement of

schools across the state. Looking at these results helps gain a sense of the learning that is

occurring and the students’ knowledge. Although the report card reports many different subjects,

I chose to first look at the early literacy component K-3 as this is when phonological awareness

instruction is most prominent. The state of Ohio scored at a 30.6% achievement rate. This

percentage is further broken down into three categories: proficiency in third grade reading,

promotion to fourth grade, and improving K-3 literacy. The third category, improving K-3

literacy, was the only category counted across the state and was 30.6%. This means that 30.6% of

students in grades K-3 were improving and making gains in that year that were previously

12

behind the expected norms for the grade level. They look at the students’ achievement in fall of

2021, 2022, and the 2022-’23 state test. In the fall of 2022, 44.5% of kindergarten students,

29.7% of first grade students, and 27.6% of second grade students were not on track. Out of

these, only 30% of them improved their literacy skills throughout the year (Ohio State Report

Card, 2023).

The above data highlights the need for supplemental literacy instruction. With that many

students performing behind the grade level norms and only a small percentage of them coming

back on track after a years’ worth of typical instruction, something extra is necessary. The state of

Ohio recognizes the need and has written a guide to improve literacy achievement throughout the

state. One component outlines the need for multi-tiered support school wide to meet the needs of

every student. It is focused on growth and improvement. Another component is to provide

educators with professional learning in the science of reading to further their knowledge on

instructional strategies for their students. Many of these focused on the theory of the Simple View

of Reading which breaks down the three main parts of reading and puts it into an equation. The

first piece is word reading or decoding, which is the student’s ability to read the words on the page

correctly. It then works with the second piece, language comprehension, which is a student’s ability

to understand spoken language put together to form meaning. When both word reading and

language comprehension are high, the students’ reading comprehension is subsequently high as

well. This is often written as word knowledge multiplied by language comprehension equals

reading comprehension (Gough & Tumner). The Department of Education takes this equation and

expands on each part to outline the importance that a student develops each. Furthermore, it

supports students’ varying needs by differentiating each component to fit the student. The state of

Ohio aims to use data-driven decision-making through engagement in the improvement process,

13

ensure that plans to improve are meaningful, evidence-based, and align to the literacy plan, support

the implementation of practices, and provide financial assistance for these efforts (Ohio

Department of Education, 2020). Through the outlined plan, The Ohio Department of Education

hopes to see literacy achievement in Ohio on the rise in the coming years.

Music and Phonological Awareness

Music and literacy share multiple elements in common and have an important role to the

emergent reader as noted by Donna Gwynn Wiggins (2007). Both music and learning to read

depend on the student hearing the difference in sounds and shapes of symbols. They are also both

read left to right. Aside from these, Wiggins points out that other parallels are phonological

awareness, phonemic awareness, vocabulary, and fluency. Wiggins studied a group of

preschoolers during a literacy lesson. The preschoolers were engaged in a literacy lesson that

integrated music. Students read a book and sang along as the book progressed. Students were

extremely energetic and were helping the teacher finish repeating phrases to show their recall of

the material. Then, students completed a matching exercise and sang the song through more

times where they acted out the story and used musical instruments. Wiggins related this lesson to

both music standards as well as the literacy standards to illustrate the connection. In the music

standards, students are to use their voices expressively, sing simple songs, experiment with

instruments, and demonstrate awareness of the elements of music (Ohio Fine Arts Standards,

2022). In the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) language and

communication standards, students are to expand their vocabulary, sing simple songs, talk in

front of a group, and relate vocabulary to their own experiences (NAEYC Standards, 2005). In

this lesson, we see the connection of the two sets of standards by seeing students singing simple

songs paired with a book, both of which assist in the expansion of their vocabulary. Students are

14

also being exposed to print which will help develop the concept of print which is an emergent

literacy skill. In a short mini-lesson, Wiggins identified multiple connections that music has to

literacy for preschool students.

Music can be used to teach a wide variety of ideas in the classroom, but there has been

success in integrating music to teach phonological awareness skills specifically. Jonathan Bolduc

(2009) studied the effect of music training programs on the development of phonological

awareness skills in kindergartners. The control group used the currently adopted program while

the experimental group participated in an adapted version of the music program that aimed to

increase interest in reading and writing through music. Before undergoing any musical training,

students took a pretest and then retook the test after the training was completed. The three

phonological awareness skills that were assessed were syllable identification, rhyme

identification, and phoneme identification. It was found that the experimental group developed

stronger phonological awareness skills according to the assessment results. In phoneme

identification tasks, the control group improved by 10% and the experimental group improved by

23.4%. For syllable identification, the control group improved by 12.6% and the experimental

group improved by 32.5%. For rhyme identification, the control group improved by 11.1% and

the experimental group improved by 30.5%. Although both the control group and experimental

group had improved phonological awareness skills, the experimental group improved their

average score more with the adapted musical program.

Another study focused on the non-musical effects that a music program had on first grade

students (Hurwitz et. al, 1975). The researchers had two separate groups of first grade students.

They were each at different schools and were taught using different musical programs. The

experimental group was taught using the Kodaly music program. The reading abilities of the

15

students were tested throughout the study. The students were tested at the beginning of first

grade, end of first grade, and the end of second grade. At the beginning of first grade, there were

no significant differences. At the end of first grade, the control group scored a 72.3 on the

achievement test and the experimental group scored significantly higher with an 87.9. Then, a

year later the students were tested one final time. The experimental group averaged 90.2 and the

control group 83.5. This again shows a significant difference and the continuation of the effects

of the program on students’ reading abilities. Not only did the experimental group’s academic

achievement improve, but researchers notated that the students had an increase in motivation and

engagement in the material when the Kodaly program was being used in the first-grade

classroom.

Phonological awareness is important to the literacy achievement of students. Reading

scores are low and need to improve. Prior studies show that there is a link between music and

reading. Research on the topic is currently very limited. We need to continue to explore how

music can improve a child’s phonological awareness skills to improve their engagement and

achievement. Next, I will review the methodology for my current study.

16

Chapter Three

Method

This chapter outlines the methodology that I used to analyze how music integration

during phonological awareness instruction improves student engagement and achievement. In

my research, I utilized teacher interviews of the school across a variety of grades to gauge how

music was currently being integrated. I also taught targeted phonological awareness lessons on

consonant blends with and without music. This methodology offers a comprehensive approach to

understanding the impact music has in the classroom.

Background

I completed my research and interviews in a Midwest Ohio town. The school I was in is a

rural school with a population of almost 900 students and a teacher-student ratio of 1 to 21. Over

half of the teachers have been evaluated as accomplished and 41.3% are considered skilled. No

teachers have been evaluated as ineffective. Around ninety percent of students are white/non-

Hispanic. The other 10% of students are multiracial, Hispanic, or black. Many students, around

350, are economically disadvantaged and the school qualifies for title I funds. With this funding,

48% of students receive free or reduced lunch.

I will now look at the Ohio state report card for the school district I was completing my

research in. I chose to look at this data because it pulls a lot of information from the school’s

performance throughout the previous year. The report card reports a lot of data on achievement,

but I specifically looked at the early literacy component as this is the grade bands and content

that I am focusing my research on. The early literacy component measures the school’s

effectiveness in reading and literacy supports in grades K-3. This district was rated as 83.3%

17

overall, and this score is further broken down into three additional categories. Proficiency in

third grade is 72.2% and is the number of students who scored proficient on the state English

test. In order to qualify in this measure, students had to score a 50 or higher. The second

component is promotion to fourth grade and 100% of students were promoted. The final

component tracks the reading improvement that occurs in grades K-3 for students who have

previously been off track but are back on track. This measure uses fall reading diagnostics as

well as the state tests but was not reported (Ohio State Report Card, 2023). Another area of the

school report card is the gap closing. This school was rated a four out of five stars which exceeds

state standards in closing educational gaps. This measure is evaluated to show how well students

are meeting performance expectations in different subjects. In English Language Arts, the

students’ performance goal was 80.5 and they reached 85. For English Language Arts growth, the

school fell by 2.3 points. The reason for the school’s growth decreasing is because in the

previous year the school had more growth in early literacy. Although students were improving it

was not as much as they had previously shown improvement for.

Teacher interviews and beliefs on music integration

In order to gather more information on what teachers currently do to integrate music into

their classroom as well as their personal beliefs on the idea of using music to teach phonological

awareness skills, I conducted interviews with general education teachers. The teachers that I

conducted interviews with were three general education teachers and the music teacher. These

teachers teach kindergarten, second grade, and third grade. I chose these grades because

kindergarten is a grade where students learn many foundational phonological awareness skills. I

chose second grade because I was teaching the lessons here and it is another large year for

growth. Lastly, I chose third grade because of the third grade reading guarantee and wanted to

18

see how the teacher in third grade taught phonological awareness skills. I also interviewed the

music teacher who teaches grades kindergarten through sixth. During the brief interview, I asked

a series of questions related to their beliefs and use of music in the classroom. The questions that

I asked the general education teachers and the music teacher differed. This is because the

standards for the general education teachers and the music teachers are different. I was interested

in seeing how much integration of the two was done in both areas. The questions I asked the

general education teachers focused on the strategies they find effective in their classroom for the

teaching of phonological awareness skills and how they were using music. For a full list of

questions, see appendix A. The questions that I asked the music teacher consisted of questions

regarding engagement in her classroom as well as how she is able to assist general education

teachers in integrating music into their classrooms. The full list of questions for the music

teacher are in Appendix B. After I taught the series of lessons on consonant blends with and

without music, I asked the second-grade teacher another set of questions to gauge her thoughts

on student engagement and use of music. These questions can be found in Appendix C.

By completing these interviews, I was able to gather a sense of how music was or was not

used in this elementary school. Gaining perspective from a wide range of grade levels and the

music discipline provided unique perspectives because they are instructing different aged

students who are learning different skills related to phonological awareness.

Lesson Plans

In the second-grade classroom, I implemented a total of four different lessons centered

around consonant blends. Consonant blends are when two to three consonants are right next to

each other in a word, and each give their own sound (Invernizzi et. al, 2023). Examples of blends

in a word include the bl in blend, sl in slip, and cr in crate. These relate to phonological

19

awareness because students need to hear the two consonants and how they seamlessly slide from

one to the other in the word. As they hear these consonant sounds, they can then write the words

or recognize the word when spoken aloud. I chose this skill because this group of second grade

students were completing a review of the subject after the grade level teachers saw there was a

gap in the students’ knowledge of blends. Two of these lessons incorporated music within them

while the other two did not use music. They were taught in two segments, each taking two days.

They occurred in back-to-back weeks. The first lesson of each segment did not incorporate music

and the second of each included brief exposures to music through YouTube that supplemented

the teaching of the blend. These lessons all began with their typical phonological awareness

instruction – Heggerty. Heggerty is a curriculum that provides students a short daily lesson on

phonological awareness skills (Heggerty, 2020). Through Heggerty, students practice necessary

phonological awareness skills that will help them become successful readers. These skills include

segmentation of words into phonemes, blending phonemes to form a word, identifying the

medial vowel in a word, rhyming, counting the sounds in a word compared to letters, and more

phonological awareness skills such as consonant blends and digraphs (Heggerty, 2020). The two

weeks when the lessons were implemented consisted mostly of words with blends in them

through each activity. It gave a segue into the lesson on the blend of that day. After Heggerty,

students would be asked the sounds of the letters in the blends and then the sound together. I

would then ask students to raise their hands and give examples of words they know with that

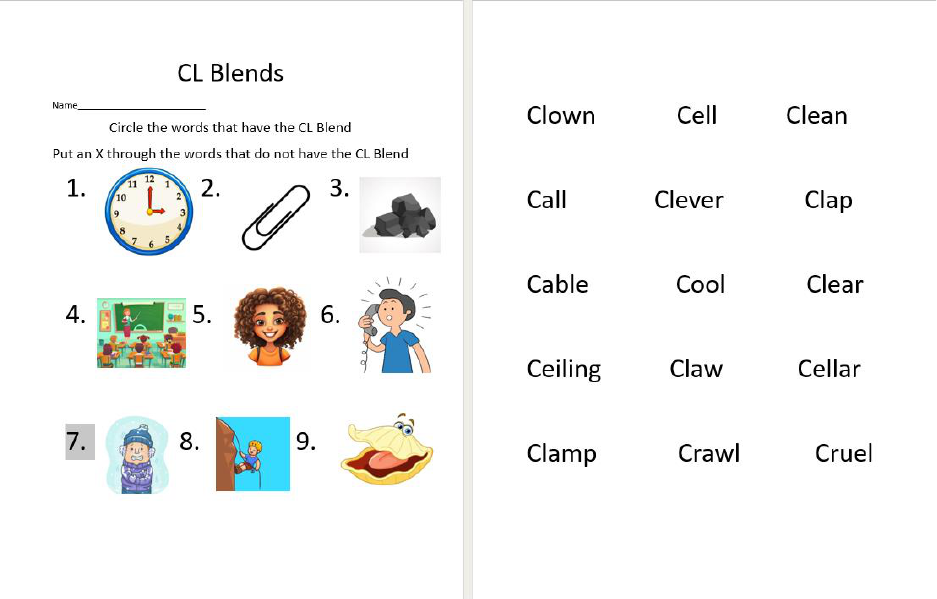

blend. Then, students would complete a worksheet about the specific blend. An example of these

worksheets can be found in appendix D. On the two days with music, before we discussed the

blend and gave examples, students would watch and listen to the short instructional music video.

These songs were carefully picked to have a catchy tune that students could easily pick up on

20

and participate in throughout the song as well as remember after the song is no longer being

played. The links to these videos can be found in Appendix E.

The worksheets for each lesson all followed the same structure. The first page consisted

of nine pictures. I would read aloud the words that these pictures depicted and ask students to

circle the picture if it has the blend and cross it off if it does not have the blend. The reason for

me reading it to them is because pictures can be subjective as to what their representation is.

Phonological awareness is also based on the students’ ability to recognize sounds in spoken

language, so I wanted to see their performance on an auditory exercise. On the back side of the

sheet, there were printed words and students were asked to circle the words that have the daily

bend and underline the blend. This side of the sheet assesses if students were able to recognize

the blend in printed words. This tells me that when they come across a word in a story with the

blend, they will know how to begin sounding the word out.

21

Chapter Four

Results

In this chapter I will report the results of my study to answer the question on if music has

an effect on engagement and student achievement in phonological awareness instruction. The

results will be in two parts. The first part will be the teacher interviews on their current

phonological awareness instruction and their beliefs on integrating music. I will be summarizing

the interviews and the answers that I received from them. The second part consists of results

from the series of lessons taught on consonant blends to the class of second graders. These

lessons will be summarized and focused on their achievement on the worksheet as well as their

participation and engagement throughout the entirety of the lessons.

Teacher Interviews

At this particular school, the music teacher, Mrs. Emigh, teaches kindergarten through

sixth grade music. She sees students twice every six school days for forty minutes. She explained

to me that most all of the students are engaged when they are in music class. She attributes this to

the pacing of the activities being fast as well as the students getting to use their whole body to

participate. Mrs. Emigh believes that if there is a way for music to be included in the general

education classroom that it should be done because it offers the students another way to learn.

Mrs. Emigh is available to teachers if they have any questions or need support in using music in

their classroom. After talking to the teacher to see what their needs are, she would offer help in

any way that she is able. This could range from offering resources she knows or making a

recording of the music that they need. Because students only go to music class twice every six

days, she has difficulty incorporating general education skills into her lesson plans. Mrs. Emigh

has been teaching for many years and used to teach a unit on the Underground Railroad when

22

that grade was learning it, but she did not have enough time to get to everything, so it had to be

cut out. She does, however, incorporate classroom skills within her lessons when the opportunity

arises and is relevant to the music content. For example, she talks about syllables when

transferring lyrics to notated rhythms. She has also called upon students’ knowledge of fractions

to help them understand the math behind rhythms and their names. She explained that with the

demand of the music content standards as well as preparing for performances, there is just not

enough time to “take deep dives” into full unit lessons on classroom skills.

I interviewed Ms. Miser at the school I completed my research in to get a perspective on

music in her kindergarten classroom. Currently, she uses Heggerty, Visual Phonics, and Core

Knowledge Language Arts Skills (CKLA) to teach phonological awareness. She likes these

curricula because they use a combination of visual and kinesthetic approaches to learn early

literacy skills. In Heggerty and CKLA, students often sing nursery rhymes with the goal of

identifying the rhyming words in them. She explains that for both Heggerty and Visual Phonics,

students manipulate sounds within words by using their hands and arms. Outside of these

curricula, Ms. Miser uses Play-Doh and sand for students to practice writing their letters. She

likes giving them another form of practice that is hands on. With her use of different curricula as

well as adding in her own activities, she gives students multiple ways to practice that suits the

needs of each student in her classroom. To her, the most effective strategies are strategies that use

a kinesthetic approach. Students are demonstrating those literacy skills with their hands, arms,

and legs. Students with special needs and speech IEPs are also benefiting from these strategies.

They get to visualize letter sounds that they are not remembering when only hearing them orally.

After I learned more about Ms. Miser’s instruction on phonological awareness, I wanted

to see if and how she was incorporating music into her instruction. Ms. Miser uses music all of

23

the time in her classroom. She explained that not only does she introduce concepts through

music, but she also uses it as a review tool. Ms. Miser said, “I have never come across a student

who didn’t benefit from learning a concept through music.” Students of all different abilities are

able to use music to learn and she noted that even her lowest achieving students have been able

to learn hard concepts when being taught with songs and rhymes. Ms. Miser is creative in using

music and makes up her own songs and rhymes for everything in her classroom, spanning all of

the subject areas as well as school rules and daily routines. Jack Hartman and Scratch Garden are

YouTube pages she frequents to teach these skills (Hartman, n.d., Garden, n.d.). She likes them

for their interactive components and feels that it is an easy way to incorporate music into the

curriculum. Nothing is holding Ms. Miser back from using music in her classroom. Music is

implemented in her lessons and throughout the day to get the day started, end the day, and used

as a calming tool. Ms. Miser explained to me that “our (her and her class’s) day never exists

without a song!”

I also interviewed a third-grade teacher, Mrs. Stuart. Mrs. Stuart has been teaching for

many years in the district and has a lot of experience in using many techniques to teach her

students. In response to her current strategies that she uses to teach phonological awareness

skills, she explained that by third grade, the students should already have mastered the skills.

When she does return to these skills, she says she finds it best to put the skills in context by using

literature to help students brush up on these skills. She has created multiple binders of different

pieces of literature that she will use if it is necessary. When it comes to using music to help

amplify her phonological awareness instruction, it was explained that she does not use it for that

because it is review but does use music in other domains that are more third-grade friendly. She

shared a story with me about a student of hers who also attends the same church as her. One

24

Sunday at church there was a question asked about the continents, and her student quickly named

all seven of them. At school the next day, this student said, “that song you taught me really

helped me remember!” Although this is unrelated to phonological awareness skills, this shows

the power that music can have on students’ knowledge of any subject. Mrs. Stuart talked about

how music helps because students remember it. Mrs. Stuart said that “this act of remembering

can be used for many years to come and can be helpful in tasks that require them to recall their

knowledge on formal assessments like quizzes and tests, but also in informal ways like a

conversation they may have outside of school.”

Before I conducted lessons in the second-grade classroom, I interviewed Mrs. Lester

about her beliefs on integrating music in her phonological awareness instruction. A strategy that

she uses frequently is read-alouds, specifically read-alouds with books that have been

purposefully chosen such as books with many rhymes, alliteration, and repetitive patterns. She

says these help students recognize phonological elements. She also uses the Heggerty curriculum

each morning which allows students to practice blending and segmenting words into individual

sounds. Mrs. Lester also uses games that engage students to practice different skills. These

games consist of rhyming games or word-building games. Lastly, Mrs. Lester uses a code chart

book that the CKLA curriculum uses. Students learn the different patterns in words and color

their code book based on the sound and the pattern’s frequency in words. Mrs. Lester likes this

because students are able to make the connection from the sound they hear to the spelling. Mrs.

Lester feels that the most effective strategy that she uses is Heggerty. When asked about using

music to teach phonological awareness skills, she explained that she often uses songs that she

finds on YouTube. She does believe that music is an effective tool and said, “students are

25

engaged, and recall is stronger for many students.” There is nothing holding Mrs. Lester back

from using music in her instructional strategies for phonological awareness.

After I had taught the series of lessons in the classroom, I re-interviewed Mrs. Lester to

gain her perspective on the lessons. She said she saw a difference in the students’ participation

and much more engagement when music was being used. She believes that the music helped

students recall and learn. When asked if her thoughts had changed on incorporating music into

phonological awareness lessons, she explained, “I have known this is an effective method for

teachers to use, especially with elementary students.” She also said that she would like to start

using it more frequently now that she has seen it used and that there is still nothing holding her

back.

Throughout the school that I completed my research, music has been used in many ways

to help students learn. In Ms. Miser’s kindergarten classroom and Mrs. Lester’s second grade

classroom, students are using music to build upon other curricula such as Heggerty, CKLA, and

Visual Phonics. They are also using music to supplement with other additional activities that are

used in their classrooms frequently. In Mrs. Stuart’s third grade classroom, although she does not

use music for phonological awareness skills, she implements music to teach other third grade

content. In each of the three classrooms, the teachers report seeing a positive impact on their

students’ learning when using music. Students are engaged, focused, using the song outside of

the school setting, and truly love when they get to learn in that way. YouTube, specifically Jack

Hartman and Scratch Garden, was noted multiple times as the place to find catchy songs to help

students learn. With many years of experience from each of these teachers, they understand the

importance of students developing phonological awareness skills that will help them become

better readers and writers, especially in Mrs. Lester and Ms. Miser’s classes where they are

26

building a foundation. There are many ways that these teachers are teaching these skills like

rhyming, alliteration, blends, digraphs, short and long vowels, decoding, encoding, etc., but

music is a staple in each of their classrooms to supplement the instruction on these necessary

skills. In addition to the methods being used by these teachers, the music teacher, Mrs. Emigh, is

there to offer support in whatever way that they may need it. Although she is unable to do much

with the content learning standards in her class time, she recognizes the importance of making

connections when she can. She also sees every day how engaged her students are in music class

which remains consistent with what the grade level teachers have seen in their room when they

incorporate music.

Lesson Observations

Throughout the implementation of the lessons, I primarily focused on the students’

engagement and participation. I also analyzed the worksheets that they completed directly

following the lesson and tracked any changes in performance. I will now discuss each of these

points in correspondence to the lessons.

The first lessons I will discuss will be the lessons on the blends SL and CL. SL was

taught without music. First, I completed Heggerty which consists of many key phonological

awareness skills. The three main skills that were focused on in these Heggerty lessons were

blending phonemes, segmenting words into phonemes, and encoding. I also focused on the

student’s engagement/disengagement. I noted engagement when students were keeping eyes

forward, completing the hand motions in Heggerty, speaking the parts of Heggerty, participating

in discussion by raising hand, answering prompts, etc. I noticed disengagement when students

were looking around the room, not staying in their seats, not doing the hand motions for

Heggerty, not speaking aloud Heggerty prompts, and not willing to participate in discussion.

27

When students were blending phonemes, I provided them with the phonemes like in the example

word blast. I said the phoneme sounds rather than the letters. Students then repeated the sounds

and blended the word to say blast. The next skill, segmenting, involved students hearing a word

such as blast and then students were to ‘chop it up’ into the sounds. They would say, “b-l-a-s-t,

blast.” The final skill was encoding. I said a word, students broke it up into the sounds they

heard, then they spelled the word. This skill helps students transfer the knowledge of phoneme

sounds to how they would write the word. After Heggerty, I briefly taught the concepts of a

consonant blend in a class wide discussion. I introduced them to the SL blend and gave them

multiple words as examples, then I asked them for examples. Some students were eager to share

and came up with a variety of words. Other students were less engaged in this and did not raise

their hands to participate but were looking around the room. Around 25% of the students were

actively participating in this discussion based off of hands raised. Students then started on the

worksheet. The first page featured pictures of words with and without the SL blend. I read these

aloud and instructed students to circle pictures of words that they heard the SL blend sound and

to cross off the ones that did not. As I said the words, a handful of students would say it slower

using the skill of breaking apart phonemes like in Heggerty. However, most were very quickly

circling or crossing off.

I taught the CL blend the following day. After Heggerty was completed, the CL blend was

taught in a whole group setting. Students were asked what C sounds like and then L. They then

blended them together and correctly said the CL sound. A song on the CL blend was then shown.

Students were invited to sing along and interact with the video shown. Throughout the song,

students slowly started singing, dancing, and clapping with the song as they became more

comfortable. Before we moved to the worksheet, we reviewed the CL blend as a group. I asked

28

students to raise their hands and give examples of words with this blend, just like the day before.

Immediately, hands were in the air. Nearly the entire class was raising their hands ready to

provide a word for the CL blend. We then moved into completing the worksheet for the CL

blend. Like SL, I read the first page, and they circled words with the SL blend. Unlike the day

before, students were humming the words quietly and a few were even singing the sound aloud

to help them. Others were tapping out the words like they are used to doing. Students were

utilizing this new song about the CL blend to help them determine if the CL blend was in the

word I had said.

When looking at the achievement level on the SL and CL lesson segments, there was

improvement in many students in the CL lesson that utilized music. Fifteen students were present

for both the SL and the CL lesson, and their data was included in this comparison. Of these

students, five students improved on the recognition of sounds and circled more blends correctly

during the CL lesson. Eight students circled all pictures correctly on both the SL and the CL

lesson. Two students had a slight decline in performance on day two and circled some of the non-

blend CL words in the picture. Pictures that depicted curl, cold, and call were the most missed by

these two students. On the back of the worksheet students had a list of words and circled the

words with the blends in them. During the SL worksheet, thirteen of the fifteen perfectly

recognized the blends in the words. The other two students had missed circling two of the SL

blend words. During the CL worksheet, all fifteen students circled all of the words correctly.

The following week, I taught the second segment of lessons on the blends BR and CR. I

started with BR. I followed the same format with Heggerty, discussion, and then a worksheet for

the BR blend. At this point, students were very familiar with the lesson and many asked, “are we

going to hear another song?” or “is there another video to watch?” When I answered them and

29

said that there was not today, many were disappointed. Engagement was lower in Heggerty than

previous days. The same students who are always active participants in Heggerty were still

participating, but the students who do not always participate were not participating and required

many reminders. After Heggerty, we talked about the BR blend, and I again asked for some

examples. Some students shared and then we moved on to completing the worksheet. On this

day, I saw less hands than the day we had learned with music. All students present completed the

worksheet and if they were using a skill to hear the blend, they would tap it out. I noted that

students seemed very disengaged with the worksheet. Students’ focus was wandering to look out

the window, tapping their pencil, talking, and overall, not engaged with the lesson as a whole.

The following day, I taught the CR blend, this time incorporating music in between

Heggerty and the worksheet. When the screen came on with a video, many were very excited

about the song. They showed their excitement by cheering and I even had a few students thank

me for showing them a video. It took less time for students to start interacting with the video.

They were clapping and singing along in no time. Just like in the lessons before, I asked for

examples with the blend in it. After the music, almost the entire class was raising their hands

ready to share a word with me. Students were sitting up and attentive to the words their peers

were providing and were eager to answer. Throughout the worksheet, I saw the same results.

More students had stopped tapping it out and were instead singing the song from the video to

help them determine if the word had the CR blend or not. I observed a small group of students,

around six or seven, using both the song and tap out the word. There was even an increase in

those using the song from the CL lesson to this lesson on CR. During the CR worksheet,

approximately 75% of the students in the class were connecting the worksheet to the song they

had heard whether it be through humming, mouthing the words to the lyrics, or very quietly

30

singing it to themselves. I noted this by writing down names of students who I saw and heard

using the song.

During the BR and CR lesson segment, there was apparent growth in knowledge of

blends. Fifteen students completed both lessons in this segment. Eleven students had perfect

scores on the blend recognition picture side of the worksheet for both the BR and CR blend. This

is an improvement from eight during the SL and CL lesson segment. Three students made

improvements from the BR lesson to the CR lesson. Only one student had a decline from the BR

lesson to the CR lesson. On the backside of the worksheet, all fifteen students had perfect

performance in recognizing the blends in a list of words.

31

Chapter Five

Discussion

Throughout this chapter, I will discuss the key takeaways from the research I studied, my

interviews, and the lessons I taught on blends with and without the integration of music. As I

discuss the results, I will align them with my research question: Does using music in

phonological awareness instruction increase student engagement and achievement?

Teacher Interviews

I conducted interviews with grade level kindergarten, second, and third grade teachers to

gauge an understanding of their phonological awareness instruction and their beliefs of using in

their classroom to teach phonological awareness. In each grade level, I saw many common

themes across the teachers’ beliefs on the use of music within their classroom that I will expand

on.

Each teacher in the grade level classroom explained that when they use music, they see

an increased level of engagement across their class. Mrs. Emigh also stated that most kids are

engaged in music lessons during music class. Students are interacting with the material in a way

that is beneficial to their recall of the knowledge when using music as a support. In Mrs. Stuarts’

class, she explained that music was beneficial in her students’ lessons on continents and in both

Mrs. Lester and Mrs. Miser’s classes music was beneficial to teach different aspects of language

like rhyming, alliteration, syllables, etc. This is consistent with the study completed by Lee

(2009) who taught students vocabulary in a new language using music. Lee found that students

retained the new material much better as well as interacted with it better when put in music form.

In the study completed using the Kodaly music program (Hurwitz et. al, 1975), the researchers

32

noted the same outcome of more energy, engagement, and motivation. Not every lesson will

initially strike a student as being interesting or entertaining, but by providing an additional

support with the integration of music into the lesson, more students will be engaged, which will

help them take in the information being presented.

Integrating music can be as simple or as complex as a teacher would like it to be. Many

teachers, including Ms. Miser and Mrs. Lester, use pre-made music tracks available on YouTube.

These are easily accessible and include songs that cover many different skills and content areas.

These also provide a visual along with the music. If a teacher was interested in creating a song

based on the content in their curriculum, they could always use the school music teacher as a

resource. Mrs. Emigh, the music teacher at the school where I completed my research, explained

that there is not enough time to focus on both the music standards and the content standards in

the short amount of time she spends with students, but that she is able to help teachers locate

resources or record tracks if needed. With this resource available to teachers, they could find

more opportunities to integrate music in their classroom. In the study by Hurwitz (1975),

teachers were using the Kodaly music program which showed a positive correlation with

phonological awareness abilities. Kodaly does not have direct ties to phonological awareness, but

researchers found that it did have an effect on literacy performance (Hurwitz, 1975). This shows

that there may be programs that already have elements that combine the two domains. If these

are available for schools to adopt, the integration could happen more naturally yet still have the

same effect on students in their knowledge of other content areas.

Throughout my conduction of interviews, I saw that music was a common thread in each

of the classrooms that I visited. It was aiding in their instruction of the curricula that the school

had already adopted. I went into each interview unsure of what to expect from the different

33

teachers as they had different levels of experience in teaching and were taught at different ages.

Because they all do incorporate music in some way, there is evidence to show the many

capabilities that music has across the lower elementary grades. My research was conducted in a

K-3 setting but would be interesting to see if the use of music being beneficial to instruction is

also occurring in the upper elementary grades. As students progress in school, the academic

content standards become more rigorous, similar to the music content standards. By integrating

them together, students have the potential to increase their achievement in both areas.

Interviewing teachers was a beneficial and necessary piece of the research that I

conducted as it gave me insight to the current use of music across elementary school. Students

spend very limited time in music class and because of this not much integration can be

completed during that small amount of time. However, teachers in grade level classrooms are

integrating music in cohorts with the school adopted curricula using pre-made music they find on

the internet. They primarily see a difference in the engagement of their students which remains

consistent with the currently published research. A teacher needs to know their students to know

how they best learn, but Ms. Miser stated that she has never seen a student not benefit from

music integration.

Consonant Blend Lessons

In the series of four lessons taught on consonant blends, Mrs. Lester and I observed the

stark difference between when the lessons incorporated music and when they did not. Not only

was engagement higher class-wide, but students’ performance on the short worksheet was also

different in the lessons with and without music. Using the songs gave students more exposure to

words with the specific blend and without the music, students were not engaged and not provided

with words that they could share and discuss.

34

I used songs in the CR blend and the CL blend lessons taught on the second day of that

learning segment. In the previous days, engagement was low and there was not much

participation, but on these days, the engagement was much higher. Students were excited to have

both the visual of the video and the music. On the second day with music, students were even

asking for music and had much more energy. They sang along, danced, and then applied it to

their worksheet. When students knew that music would be a part of that day’s lesson, they

showed even more interest in the topic through more participation in conversation and Heggerty.

Herwitz (1975), Wiggins (2007), and Blasco-Magraner (2021) all noticed increased engagement

and motivation in their research as well. With literacy performance being at a 30.6% in the

previous school year for the state of Ohio (Ohio State Report Card, 2023), something that

increases student motivation and achievement could be beneficial to literacy performance. This

would hopefully raise the literacy performance score. In multiple observational and quantitative

studies, including my own, this integration of music was proven beneficial.

Phonological awareness is important to the success of the reader (National Reading

Panel, 2002)). In these lessons, students learned the phonological awareness skill of a consonant

blend. Consonant blends are when two to three consonants are right next to each other in a word,

and each give their own sound (Invernizzi et. al, 2023). On the back side of the worksheet,

students had a list of words that they were reading and then circled the words with the consonant

blend present. Throughout the worksheets, students excelled at recognizing the blends. By the

second segment of lessons, all students who participated missed zero words on the back of the

paper. Because students knew the sound of the blend, they were able to use their skills to read the

word. When students come across words in their reading, they will be able to read words with

consonant blends in them. In the research completed by Kozminsky and Kozminsky (1995), they

35

saw that students with phonological awareness instruction were better readers and comprehended

texts better. This relationship makes the solidification of skills valuable for students as they will

continue to read for comprehension throughout school and life. Although students could have

learned the blends through lessons without the use of music, the music makes the learning

memorable, and material stays with the students for a longer period of time.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to the research that I have conducted. The first is that I

had a small sample size of only 24 students. Among these 24 students, there were many absences

throughout the four days that I taught the lessons. This caused me to only have data on 15

students for each segment of blends lessons who were there for both lessons. With more students

and a larger sampling group, the data has the potential to show more about the achievement

across the lessons. Another addition could be to do lessons with music that is pre-made like I did

as well as lessons with songs that are created by the teacher in conjunction with the music

teacher. This could add more engaging elements like instruments and movement and be even

more purposeful. These two styles of integrating music could be compared with no music to

further show the differences. I only completed instruction for two days using music and two days

without. Due to time and scheduling constraints, the four lessons were not taught in four

consecutive days but had the weekend in between which is the reason for being taught in two

segments. Lastly, the group of second grade students, although I had relationships with them,

were not part of my personal class. I did not regularly teach them lessons in my teacher

preparation program at this time, so there may have been hesitation on both of our parts in the

instruction.

36

Future Research

Through the completion of my research on the effectiveness of integrating music into

phonological awareness instruction, I was met with the challenge of having little research to

draw from. The topic of music integration into the general education classroom as a whole has

not been researched to the extent that it could be. Finding specific studies on phonological

awareness instruction with music was even more of a challenge. Phonological awareness is a

predecessor of successful reading which makes it that much more important. I recommend more

research on this material to create an educational system that recognizes the benefits of music

integration and the role it plays on literacy success. It is being used and this can be seen through

the multitudes of YouTube videos, but with even more purposeful use, the growth of students’

literacy could be improved. There is work that needs to be done to improve the current state of

literacy achievement and as more support is researched, we can find more ways to help students.

As educators, our main goal is to teach our students and continue to foster their learning growth.

More research would provide the resources that educators need in order to integrate music

successfully into their instruction.

37

References

Blasco-Magraner, J.B., Bernabe-Valero, G.V., Marin-Liebana, P.M., Moret-Tatay, C.M. (2021).

Effects of the Educational use of music on 3 to 12-year-old children’s emotional

development: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and

Public Health.

Bolduc, J.B. (2009). Effects of a music programme of kindergartners’ phonological awareness

skills. International Journal of Music Education, Vol. 27.

Chard, D.C. & Dickinson, S.D. (1999). Phonological awareness: Instructional and assessment

guidelines. Reading Rockets. https://www.readingrockets.org/topics/phonological-and-

phonemic-awareness/articles/phonological-awareness-instructional-and#skip-to-main

Eccles, R.E., Linde, J.L., Roux, M.R., Swanepoel, D.S., MacCutcheon, D.M., Ljung, R.L.

(2021). The effect of music education approaches on phonological awareness and early

literacy: A systematic review. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, Vol. 44.

Gough, P.G., Tunmer, W.T. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and

Special Education, Vol. 7.

Hartman. (n.d.) Jack Hartman Kids Music Channel [YouTube Channel]. Retrieved April 12,

2023, from https://www.youtube.com/@JackHartmann

Heggerty, M. (2020). Phonemic awareness. Literacy Resources, Inc.

Hurwitz, I.H., Wolff, P.W. (1975). Nonmusical effects of the kodaly music curriculum in primary

grade children. Journal of Learning Disabilities, Vol. 8.

38

Invernizzi, M.I., Bear, D.B., Templeton, S.T., Johston, F.J. (2020). Words their way: Word study

for phonics, vocabulary, and spelling instruction (7

th

ed.). Pearson.

Kozminsky, L.K. & Kozminsky, E.K. (1995). The effects of early phonological awareness

training on reading success. Learning and Instruction, Vol. 5.

Lee, L.L. (2009). An empirical study on teaching urban young children music and english by

contrastive elements of music and songs. US-China Education Review, Vol. 6.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (2018). NAEYC Early Learning

Program Standards. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-

shared/downloads/PDFs/accreditation/early-learning/overview_of_the_standards.pdf

National Reading Panel (U.S.). (2002). Teaching children to read : an evidence-based

assessment of reading scientific research literature on reading and its implications for

reading instruction.

Ohio Department of Education (2017). Ohio’s learning

standards. https://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/OLS-Graphic-

Sections/Learning-Standards

Ohio Department of Education (2023). Ohio School Report Cards.

https://reportcard.education.ohio.gov/

Ohio Department of Education (2019). Ohio’s Plan to Raise Literacy Achievement.

Ohio Department of Education (2022). Fine Arts Standards.

https://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Learning-in-Ohio/Fine-Arts/Fine-Arts-Standards

39

Phonics Garden. (2022, Oct. 1). CR Blend| Blue Grass Phonics| Letter Blend Sounds| Phonics

Garden [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/F5sfOQKe0Bo?si=C1cOSnZQykTahM4o

Rock ‘N Learn. (2022, Oct. 1). CL Blend Sound | CL Blend Song and Practice | ABC Phonics

Song with Sounds for Children [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/yrDffjZaMCs?si=Q-

Meg_ltGY_2XF4o

Scarborough, H.S. (2002). Toward a common terminology for talking about speech and reading:

A glossary of the “phon” words and some related terms. Journal of Literacy Research,

Vol. 34.

Scratch Garden. (n.d.). Scratch Garden [YouTube Channel]. Retrieved April 12, 2023, from

https://www.youtube.com/@ScratchGarden

Whitehurst, G.W., Lonigan, C.L. (2001). Emergent literacy: Development from prereaders to

readers. Neuman, S.N. (ed.), Dickinson, D.D. (ed.). Handbook of Early Literacy

Research (pp. 11-29). New York, New York. Guilford Publications, Inc. .

Wiggins, D.G. (2007). Pre-K music and the emergent reader: Promoting literacy in a music-

enhanced environment. Early Childhood Journal, Vol. 35.

40

Appendix A

General Education Teacher Interview Questions

1. What are the instructional strategies that you use to teach students emergent literacy

and phonological awareness skills?

2. Which of these strategies have you found to be the most effective in your classroom?

3. Have you ever used music to teach these skills?

4. What are your thoughts on incorporating music into your instruction to emulsify your

instruction on emergent literacy and phonological awareness skills?

5. Is there anything holding you back from using music in your instruction?

41

Appendix B

Music Teacher Interview Questions

1. What is the engagement like when students are in music class?

2. Do you think that music should be used in general education classroom to help amplify

the teacher’s instruction on certain topics such as phonological awareness and emergent

literacy?

3. In what ways can you support a classroom teacher if they want to or do use music in their

instruction?

4. Do you ever incorporate their skills from their general education classroom into your

instruction with the students? Why or why not?

42

Appendix C

Post-Lesson Interview Questions

1. Did you see a difference in the students’ participation, engagement, etc. when I used

music in the lesson compared to when I didn’t?

2. Do you think that using music helped instruction?

3. Have your thoughts changed on your view of incorporating music into a lesson on

emergent literacy or phonological awareness skills?

4. Would you be interested in trying to use music in your classroom more frequently now

that you have seen it used?

5. Is there anything holding you back?

43

Appendix D

Lesson Worksheet

44

Appendix E

Lesson Videos

Rock ‘N Learn, R.N. (2022, Oct. 1). CL Blend Sound | CL Blend Song and Practice |

ABC Phonics Song with Sounds for Children [Video]. Youtube.

https://youtu.be/yrDffjZaMCs?si=Q-Meg_ltGY_2XF4o

Phonics Garden, P.G. (2022, Oct. 1). CR Blend| Blue Grass Phonics| Letter Blend Sounds|

Phonics Garden [Video]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/F5sfOQKe0Bo?si=C1cOSnZQykTahM4o

45

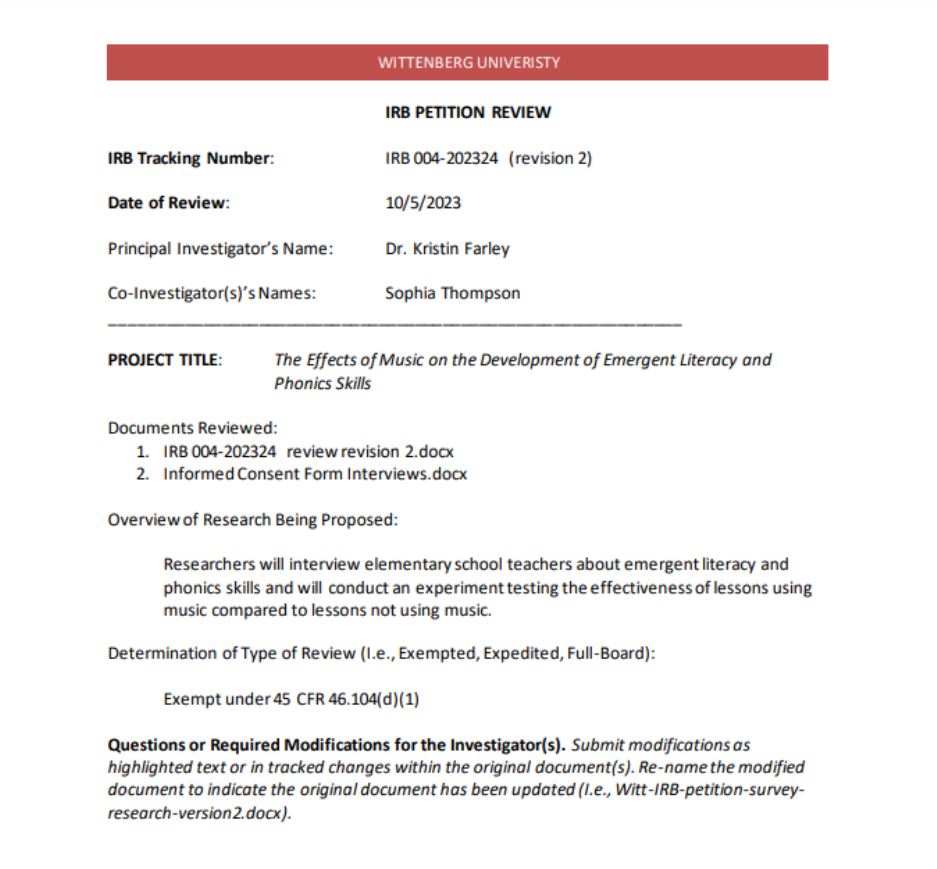

Appendix F

IRB Paperwork