Trauma-Informed Care in

Behavioral Health Services

Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series

57

Part 3: A Review of the Literature

Contents:

Section 1—Literature Review

Section 2—Annotated Bibliography

Section 3—General Bibliography

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment

1 Choke Cherry Road

Rockville, MD 20857

Contents

Section 1—A Review of the Literature .................................................................................... 1-1

Introduction to Trauma and Traumatic Stress Reactions ....................................................... 1-1

Types of Trauma .................................................................................................................. 1-15

Extent and Effects of Trauma and Traumatic Stress Reactions in Specific Populations ..... 1-24

Responses to Trauma: Trauma and Behavioral Health ........................................................ 1-38

Screening and Assessing Trauma and Trauma-Specific Disorders ..................................... 1-65

Prevention and Early Interventions for Traumatic Stress Reactions ................................... 1-72

Trauma-Specific Treatments ................................................................................................ 1-79

Integrated Approaches for Trauma and Substance Abuse ................................................... 1-93

Other Integrated Approaches ............................................................................................... 1-95

Treating Complex Trauma/PTSD ........................................................................................ 1-96

Treatment for Specific Populations ..................................................................................... 1-97

Trauma-Informed Intervention Considerations ................................................................. 1-102

Building a Trauma-Informed Workforce ........................................................................... 1-105

References .......................................................................................................................... 1-108

Appendix—Methodology .................................................................................................. 1-153

Section 2—Links to Select Abstracts ........................................................................................ 2-1

Section 3—General Bibliography ............................................................................................. 3-1

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services 1-1

Section 1—A Review of the Literature

Introduction to Trauma and Traumatic Stress Reactions

Providing a comprehensive literature review on trauma, traumatic stress, trauma-informed care

(TIC), and trauma-related interventions is a daunting task when considering the quantity and

prolific production of research in this area in the past 20 years. To manage the volume of

information, this literature review mainly focuses on reviews and meta-analyses rather than

seminal work to address many of the most relevant topics.

What Is Trauma?

In this text, “trauma” refers to experiences that cause intense physical and psychological stress

reactions. “Trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is

experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and that has

lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and physical, social, emotional, or spiritual

well-being” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], Trauma

and Justice Strategic Initiative, 2012, p. 2). Although many individuals report a single specific

traumatic event, others, especially those seeking mental health or substance abuse services, have

been exposed to multiple or chronic traumatic events. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5), trauma is defined as when an individual

person is exposed “to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence” (American

Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013, p. 271).

The definition of psychological trauma is not limited to diagnostic criteria, however. In fact,

some clinicians have moved away from considering trauma-related symptoms as indicators of a

mental disorder and instead view them as part of the normal human survival instinct or as

“adaptive mental processes involved in the assimilation and integration of new information with

intense survival emphasis which exposure to the trauma has provided” (Turnbull, 1998, p. 88).

These normal adaptive processes only become pathological if they are inhibited in some way

(Turnbull, 1998), or if they are left unacknowledged and therefore untreated (Scott, 1990).

Trauma has been characterized more broadly by others. For example, Horowitz (1989) defined it

as a sudden and forceful event that overwhelms a person’s ability to respond to it, recognizing

that a trauma need not involve actual physical harm to oneself; an event can be traumatic if it

contradicts one’s worldview and overpowers one’s ability to cope.

How Common Is Trauma?

Trauma exposure is common in the United States. However, trauma exposure varies

considerably according to different demographic characteristics and is especially high among

clients receiving behavioral health services (see the discussions under the headings “Extent and

Effects of Trauma and Traumatic Stress Reactions in Specific Populations” and “Other Disorders

That May Be Related to Trauma ” for more information on relevant rates). Although the large

surveys discussed here provide data on trauma exposure for the general population, published

1-2 Part 3, Section 1—A Review of the Literature

literature often provides more specific data as well, which is one reason why differences in

exposure according to gender and race/ethnicity are highlighted here.

At one time, trauma was considered an abnormal experience. Contrary to this myth, the first

National Comorbidity Study (NCS), a large national survey designed to study the prevalence and

effects of mental disorders in the United States, established how prevalent traumas are in the

lives of the general U.S. population (Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995).

Presented with a list of 11 types of traumatic experiences and a 12th “other” category, 60.7

percent of men and 51.2 percent of women reported experiencing at least one trauma in their

lifetime (Kessler, 2000; Kessler et al. 1995; 1999):

The most common trauma was witnessing someone being badly injured or killed (cited by

35.6 percent of men and 14.5 percent of women).

The second most common trauma was being involved in a fire, flood, or other natural

disaster (cited by 18.9 percent of men and 15.2 percent of women).

The third most common trauma was a life-threatening accident/assault, such as from an

automobile accident, a gunshot, or a fall (cited by 25 percent of men and 13.8 percent of

women.

The NCS also found that it was not uncommon for individuals to have experienced multiple

traumatic events (Kessler, 2000). Among men in the total sample, 14.5 percent reported two

traumatic events, 9.5 percent reported three, 10.2 percent reported four or more, and 26.5 percent

reported only one such event. Among women, 13.5 percent of the total sample reported two

traumatic events, 5 percent reported three, 6.4 percent reported four or more, and 26.3 percent

reported only one.

The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) is another

large national survey of behavioral health, but it only assessed posttraumatic stress disorder

(PTSD) and trauma exposure in its second wave of interviews, in which 34,653 of the original

43,093 respondents were reinterviewed (Pietrzak, Goldstein, Southwick, & Grant, 2011a). In the

Wave 2 interview, respondents were asked about 27 different types of potentially traumatic

events; the most commonly reported traumatic events were serious illness or injury to someone

close (affecting 48.4 percent of those who did not have PTSD symptoms and 66.6 percent of

those with PTSD), unexpected death of someone close (affecting 42.2 percent of those without

PTSD and 65.9 percent of those with PTSD), and seeing someone badly injured or killed

(affecting 24 percent of those without PTSD and 43.1 percent of those with PTSD; Pietrzak,

Goldstein, Southwick, & Grant, 2011a). According to the same data, 71.6 percent of the sample

witnessed trauma, 30.7 percent experienced a trauma that resulted in injury, and 17.3 percent

experienced a trauma that was purely psychological in nature (e.g., being threatened with a

weapon; El-Gabalawy, 2011).

NESARC also found that exposure to specific traumatic events varied considerably according to

race, ethnicity, or cultural group. The survey found that 83.7 percent of non-Latino White

Americans reported a traumatic event, compared with 76.4 percent of African Americans, 68.2

percent of Latinos, and 66.4 of percent of Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, or Pacific

Islanders (Roberts, Gilman, Breslau, Breslau, & Koenen, 2011). Exposure to specific traumas

also varied considerably. White Americans were more likely to report an unexpected death of

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services 1-3

someone they knew (44.7 percent did) than were African Americans (39.9 percent), Latinos

(29.6 percent), and Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, or Pacific Islanders (25.8 percent) as

well as being more likely to report having a close friend/relative who experienced a life-

threatening injury. On the other hand, African Americans were the most likely to report being the

victim of assaultive violence (29.7 percent), followed by White Americans (26.1 percent),

Latinos (25.6 percent), and Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, or Pacific Islanders (16.3

percent). In terms of combat trauma, White Americans and African Americans were about as

likely to have been combatants (10 percent of each group reported combat trauma), and more

likely than Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, or Pacific Islanders (5.4 percent) or Latinos (4.4

percent). However, Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, or Pacific Islanders were the most

likely to have been unarmed civilians in a war zone (7.5 percent), followed by Latinos (3.8

percent), White Americans (2 percent), and African Americans (1.9 percent).

Across the world, according to data from the World Health Organization (WHO) surveys, which

includes the NCS and NCS replication (NCS-R) and surveys from 20 other countries, the most

commonly reported traumas are the death of a loved one (30.5 percent), witnessing violence to

others (21.8 percent), and experiencing interpersonal violence (18.8 percent; Stein et al., 2010).

As Kessler (2000) noted, trauma from assaultive violence in the United States is likely to be

more common than in most other developed countries in general. However, trauma related to

other traumatic events (e.g., automobile accidents, natural disasters) appear to be quite similar

throughout developed countries.

A longitudinal survey from New Zealand also provides useful data on trauma exposure. In this

survey, a cohort of subjects from a single town was interviewed at age 26 and again at age 32 in

order to evaluate what constituted the worst trauma those individuals had experienced (Koenen,

Moffitt et al., 2008). The types of worst experiences reported before age 26 were:

Sudden unexpected death by trauma of a close family member or friend (38 percent).

Personal assault or victimization (32 percent).

Serious accidents (14 percent).

Hearing about or witnessing a close friend or relative experiencing an assault, serious

accident, or serious injury (12 percent).

Personal illness (3 percent).

Natural disaster (1 percent)

How Common Are Traumatic Stress Reactions?

As with trauma rates, PTSD rates vary considerably across different demographic groups. The

reader should consult the section titled “Extent and Effects of Trauma and Traumatic Stress

Reactions in Specific Populations” for more specific information on PTSD rates. More general

information from major surveys is included in this section.

The DSM-5 (APA, 2013) estimates that the prevalence rate of PTSD in the U.S. adult population

is about 8 percent, but studies of populations at high risk for PTSD (e.g., combat veterans,

survivors of natural disasters) have found PTSD rates ranging from 3 to 58 percent. The NCS

(which evaluated behavioral health disorders, including PTSD) found that, for Americans ages

15 to 54, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD (based on DSM Third Edition, text revision [DSM-III-

1-4 Part 3, Section 1—A Review of the Literature

R; APA, 1987] criteria) was 7.8 percent, with women more than twice as likely as men to have

the disorder during their lives (10.4 percent of women and 5 percent of men; Kessler et al.,

1995). In the NCS-R, which interviewed 9,282 individuals ages 18 and older between February

2001 and April 2003, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD was 6.8 percent, again with a much higher

rate for women (9.7 percent) than for men (3.6 percent; Kessler, Berglund et al., 2005; NCS,

2005). The past-year prevalence rate for PTSD was 3.5 percent, with 5.2 percent of women and

1.8 percent of men having PTSD in the 12 months prior to their interviews (Kessler, Chiu et al.,

2005).

Kessler, Berglund et al. (2005) examined the issue of lifetime prevalence in the NCS-R to

determine whether the prevalence statistics of the NCS were still valid in light of changes to the

diagnostic criteria that occurred with the publication of the DSM Fourth Edition, text revision

(DSM-IV-TR; APA, 2000). The study was divided into two parts. Part I included face-to-face

diagnostic interviews of 9,282 participants who were 18 years of age or older. Part II included

factors related to diagnosis (e.g., risk factors) and was completed only with participants from

Part I who had a “lifetime disorder” and a probability sample from other Part I participants

(n=5,692). Data analysis in this study estimated a lifetime PTSD prevalence of 6.8 percent, but

the authors also analyzed the data to determine projected lifetime risk and found that at age 75,

the lifetime risk for PTSD was 28 percent higher than the lifetime prevalence estimate. However,

the authors suggested that because of certain study limitations (e.g., related to sample

parameters, reluctance to participate or to disclose diagnoses), these results should be considered

a conservative estimate.

As noted earlier, Wave 1 of NESARC did not evaluate PTSD, but Wave 2 found that 6.4 percent

of the population (8.6 percent of women and 4.1 percent of men) had PTSD at some point during

their lives (Pietrzak et al., 2011a). NESARC researchers also evaluated lifetime prevalence of

partial PTSD (defined as including at least one symptom under Criteria B, C, and D, with

symptom duration of at least 1 month) and found that 6.6 percent of the total population (8.6

percent of women and 4.5 percent of men) met criteria for partial but not full PTSD at some

point during their lives. It should be noted, however, that most large behavioral health surveys,

such as the NCS and NESARC, rely on retrospective evaluation of symptoms, and some research

indicates that they underestimate behavioral health disorders compared with prospective

longitudinal studies (Moffitt et al., 2009). Differences in prevalence estimates may also be

related both to changes in PTSD diagnostic criteria and to a variety of methodological

differences in the research (e.g., different diagnostic instruments, procedures) on which these

estimates were based (Kessler, 2000; Kessler, Chiu et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 1995; Narrow,

Rae, Robins, & Regier, 2002).

It is also worth noting that delayed PTSD may account for a considerable percentage of PTSD

cases. A meta-analytic review that included studies in which individuals were assessed 1 to 6

months after trauma exposure and again at least 6 months later found that 24.8 percent of PTSD

cases involved delayed trauma (Smid, Mooren, van der Mast, Gersons, & Kleber, 2009). Studies

included in the review found between 3.8 and 83.3 percent of their samples had delayed PTSD.

Factors that were associated with significantly greater odds of having delayed rather than

nondelayed PTSD included a Western (as opposed to non-Western) cultural background and

military combat exposure.

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services 1-5

More recently, Smid, van der Velden, Gersons, and Kleber (2012) conducted a study of 1,083

individuals affected by a large fireworks disaster to evaluate delayed PTSD rates at both 18

months and 4 years after the disaster. In their review of prospective studies of disaster survivors,

they found that between 2 and 19 percent of survivors developed delayed PTSD, whereas in their

own study, 3.8 percent (n=24) of the total sample (n=636) who were available for all assessments

had delayed PTSD and 13.5 percent had PTSD that was not delayed.

What Is Complex Trauma?

An individual has been exposed to complex trauma when he or she has either experienced

repeated instances of the same type of trauma over a period of time or experienced multiple types

of trauma (van der Kolk, McFarlane, & Weisaeth, 1996). Expert consensus is that people who

have complex trauma will typically require more intensive and extensive treatment as well as

possible adaptations to standard treatment (see the expert clinician survey in Cloitre et al., 2011).

This Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) uses a definition of complex trauma developed by

the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN; 2003), which defines complex trauma as

a “dual problem” involving both “exposure to traumatic events and the impact of this exposure

on immediate and long-term outcomes” (p. 5). NCTSN notes that complex trauma usually

involves multiple instances of trauma (occurring either simultaneously or sequentially) and

multiple forms of trauma (e.g., experiencing emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and physical abuse).

Also, complex trauma, such as that experienced by children who sustain repeated abuse,

typically results in emotional dysregulation and a lack of appropriate coping mechanisms, which

in turn can increase the risk of further traumatic experiences. Although the NCTSN definition

was developed for explaining childhood trauma, it can be adapted to fit an adult population.

Herman (1992) was among the first to highlight the inadequacy of existing diagnostic criteria for

PTSD for people who have complex trauma by pointing out that these criteria were developed

based on a clinical consideration of symptoms experienced by individuals who had survived

relatively time-limited traumatic experiences (e.g., combat veterans, survivors of rape). Herman

proposed that many individuals with a history of prolonged and repeated trauma (as opposed to

trauma that is time-limited or related to a single traumatic event) present with clinical

characteristics that “transcend simple PTSD” (p. 379); these characteristics include physical

symptoms (including many of the symptoms listed in the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, although

they may appear more “complex, diffuse, and tenacious” [p. 379]), personality changes in which

the individual’s sense of identity is negatively affected and which may inhibit the individual’s

ability to form relationships with others, and a propensity for vulnerability to further harm (by

self or others).

In 1992, Herman published the seminal work Trauma and Recovery (revised in 1997), which

discussed proposed changes to the next DSM that would include a new term for this trauma-

related constellation of symptoms. Her suggestion was the term “complex post-traumatic stress

disorder” (complex PTSD). However, none of the proposed changes she discussed were included

in the DSM-IV (APA, 1994), DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000), or DSM-5 (APA, 2013). Jackson,

Nissenson, and Cloitre (2010) observed that the DSM-IV classification of “associated features

and disorders” (APA, 2000) for PTSD is intended to cover symptoms of complex PTSD (e.g.,

problems with affect regulation, impaired relationships), but it does not take into account one key

aspect of complex PTSD as it was originally defined, which is that such symptoms and disorders

1-6 Part 3, Section 1—A Review of the Literature

(e.g., substance abuse) are not viewed as secondary to PTSD symptoms, but rather, as equally

important and directly related to traumatic experiences.

Complex trauma is typically interpersonal and generally involves situations in which the person

who is traumatized cannot escape from the traumatic experiences because he or she is

constrained physically, socially, or psychologically (Herman, 1992). Because of this, people who

have experienced complex trauma often have additional disturbances in their ability to self-

regulate—beyond those seen in PTSD—that are not related to complex trauma. These include

difficulties in emotional regulation, difficulties in one’s capacity for relationships, problems with

attention or consciousness (e.g., dissociative experiences), a disturbed belief system, and/or

somatic complaints or disorganization (Briere & Scott, 2012; Cloitre et al., 2011; van der Kolk,

McFarlane, & Van der Hart, 1996).

What Is Acute Stress Disorder?

Acute stress disorder (ASD), according to the DSM-5, involves a traumatic stress reaction that

occurs within 1 month of trauma exposure and includes at least nine symptoms from any of the

five categories (intrusion, negative mood, dissociation, avoidance, and arousal; APA, 2013). To

receive this diagnosis, the individual also has to display a reaction that causes significant distress

or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. ASD can occur at

the time of the trauma exposure or any time within 4 weeks of that event As Roberts, Kitchiner,

Kendardy, and Bisson (2010) observed, there is a large degree of overlap between ASD and

PTSD symptoms, but what distinguishes them is the timing of those symptoms relative to trauma

exposure. Cardeña and Carlson (2011) provided a history of the ASD diagnosis and discussed

the validity of the diagnostic criteria. ASD can develop into PTSD if the symptoms extend

beyond 1 month.

What Is PTSD?

PTSD is a traumatic stress reaction that develops in response to a significant trauma. It is a

mental disorder, and for behavioral health providers in the United States, the currently accepted

diagnostic criteria for the disorder are those provided by the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). For

professionals in the field of behavioral health, the definition of psychological trauma is

historically and clinically tied to the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, which made their first

appearance in the DSM-III (APA, 1980). However, over the years, the diagnostic criteria have

undergone some significant changes. These changes are important factors to consider when

reading, evaluating, and especially comparing research.

Criterion A concerns the type of trauma involved; Criterion B describes symptoms of intrusion;

Criterion C includes the presence of persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma;

Criterion D highlights symptoms of negative alterations in cognitions and mood associated with

the traumatic event(s); Criterion E includes marked alterations in arousal and reactivity as it

relates to the trauma; Criterion F addresses the duration of the symptoms; and Criterion G

includes clinical distress or impairment in important areas of functioning (e.g., occupational).

The presenting symptoms cannot be attributable to the physiological effects of a substance,

including alcohol or medications.

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services 1-7

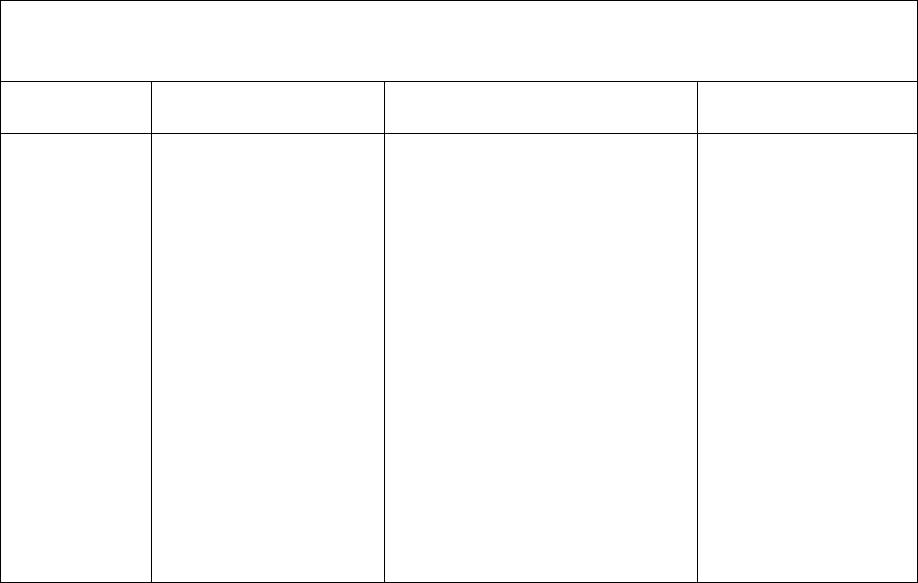

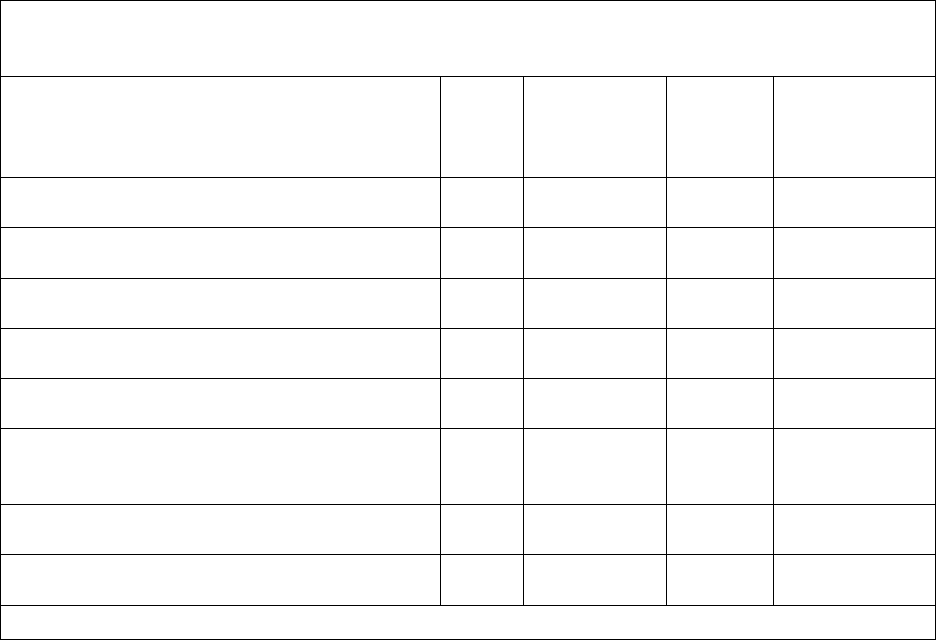

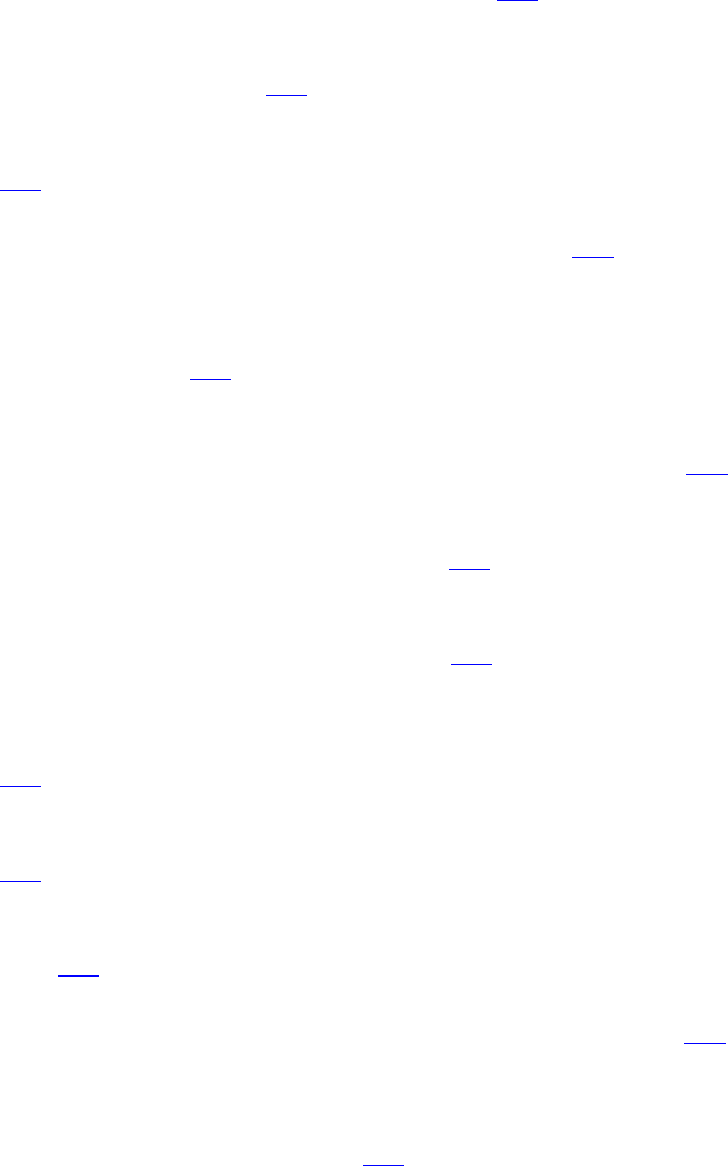

The first part of the evolving PTSD definition is Criterion A (Exhibit L-1), which describes

changes in the definition of a traumatic event from that of “a recognizable stressor,” to “an event

that is outside the range of usual human experience,” to an event that is defined by two specific

descriptors, to “exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.”

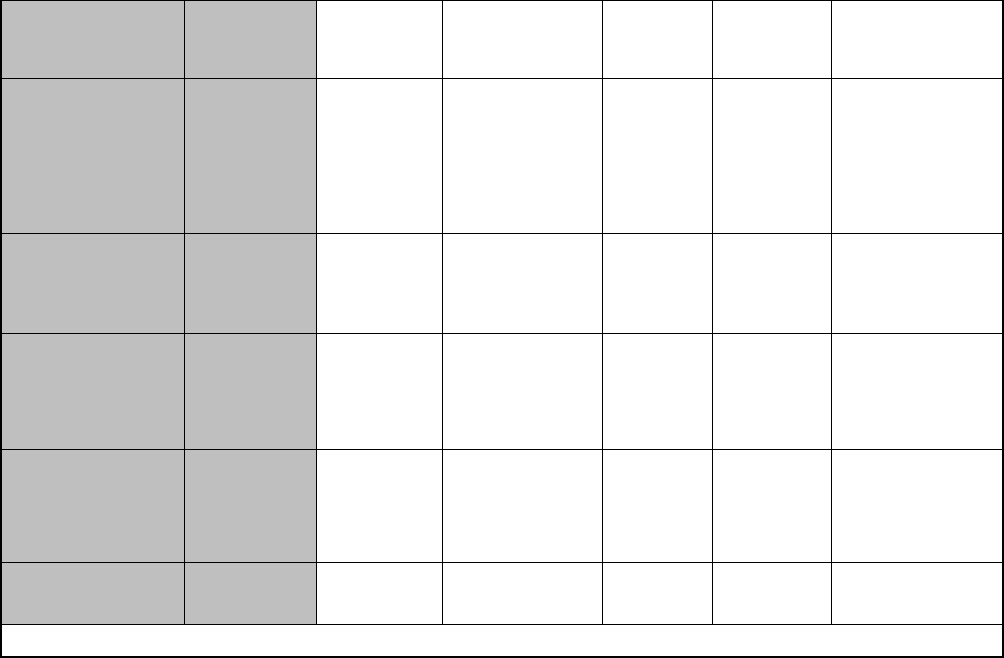

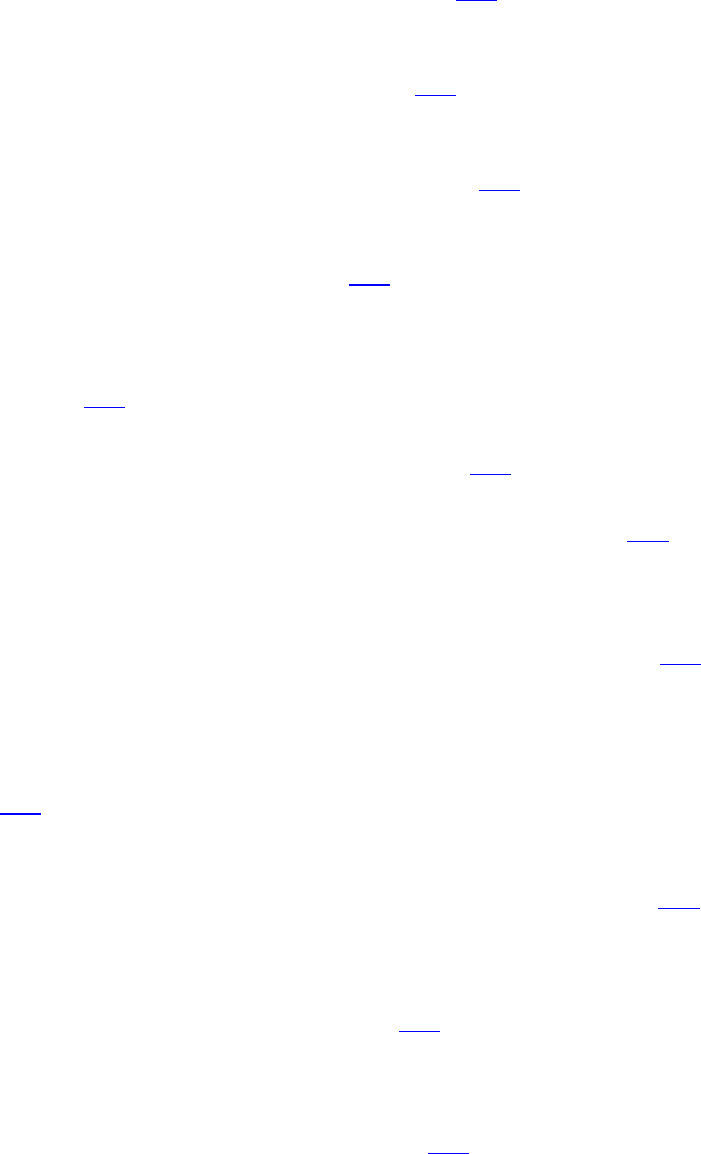

Exhibit L-1

Evolution of Criterion A for PTSD in the DSM

DSM-III (1980) DSM-III-R (1987)

DSM-IV (1994) & DSM-IV-TR

(2000) DSM-5 (2013)

“Existence of

a

recognizable

stressor that

would evoke

significant

symptoms of

distress in

almost

everyone”

(APA, 1980,

p. 238).

“The person has

experienced an event

that is outside the

range of usual

human experience

[emphasis added] and

that would be

markedly distressing

to almost anyone”

(APA, 1987, p. 250;

examples given

include serious threat

or harm to self or

others).

“The person has been exposed

to a traumatic event in which

both of the following were

present [emphasis added]:

(1) the person experienced,

witnessed, or was confronted

with an event or events that

involved actual or threatened

death or serious injury, or a

threat to the physical integrity of

self or others.

(2) the person’s response

involved intense fear,

helplessness or horror” (APA,

1994, pp. 427–428; APA, 2000,

pp. 467–468).

“Exposure to actual

or threatened death,

serious injury, or

sexual violence”

(APA, 2013, p. 271).

There are four ways

that an individual can

experience the

traumatic event(s):

directly, witnessing

the event, learning

about the event, or

through repeated or

extreme exposure to

aversive details of the

traumatic event(s).

Criterion B has also evolved. In the DSM-III (APA, 1980), it described reexperiencing a trauma

through three symptoms: intrusive thoughts, recurrent dreams, or the feeling of reexperiencing

the trauma as a result of some sort of stimulus. DSM-III-R (APA, 1987) expanded Criterion B by

adding another symptom: “intense psychological distress at exposure to events that symbolize or

resemble an aspect of the traumatic event, including anniversaries of the trauma” (p. 250). It also

added information regarding symptom presentations that may occur in children (e.g., repetitive

play expressing aspects of the trauma). DSM-IV (APA, 1994) added a fifth symptom of

“physiological reactivity on exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an

aspect of the traumatic event” (p. 428) and additional symptom presentations that may occur in

children (e.g., nightmares that lack recognizable features, reenactments of the trauma). Likewise,

DSM-5 (2013) became more developmentally focused in diagnostic criteria and added a separate

criterion for children younger than 7 years of age. Additional changes in the DSM-5 include a

more explicit definition of the stressor criterion, an additional and separate symptom cluster

highlighting avoidance and persistent negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and the

elimination of an individual’s subjective reaction to the traumatic event (intense fear,

helplessness, or horror).

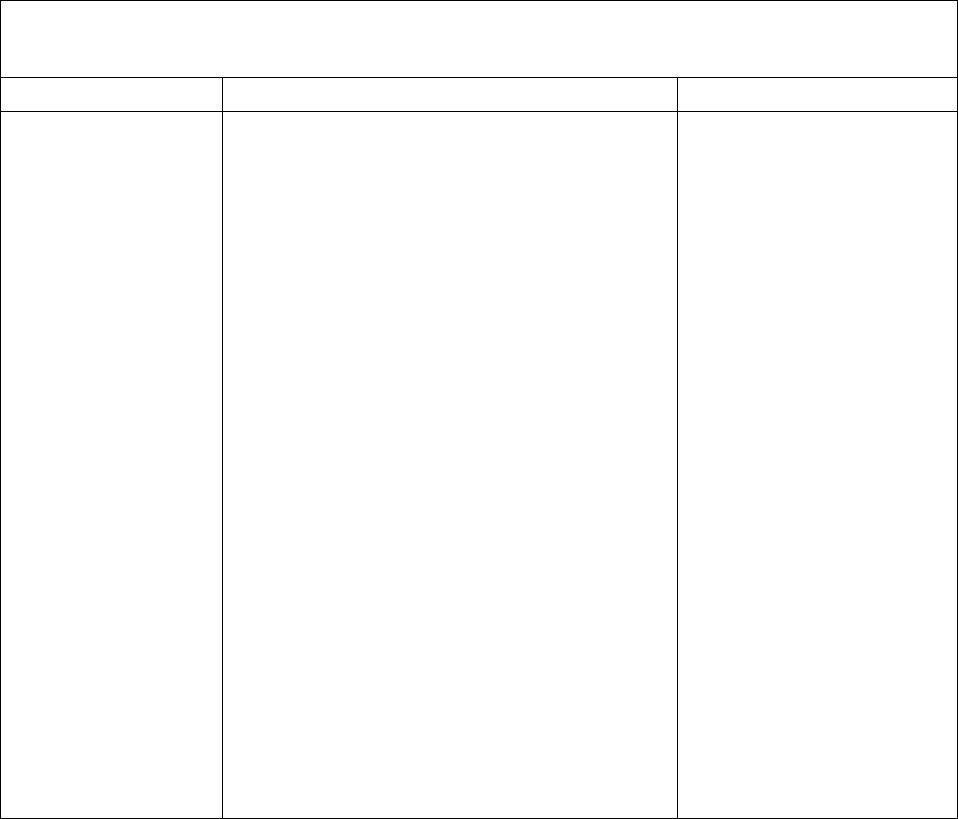

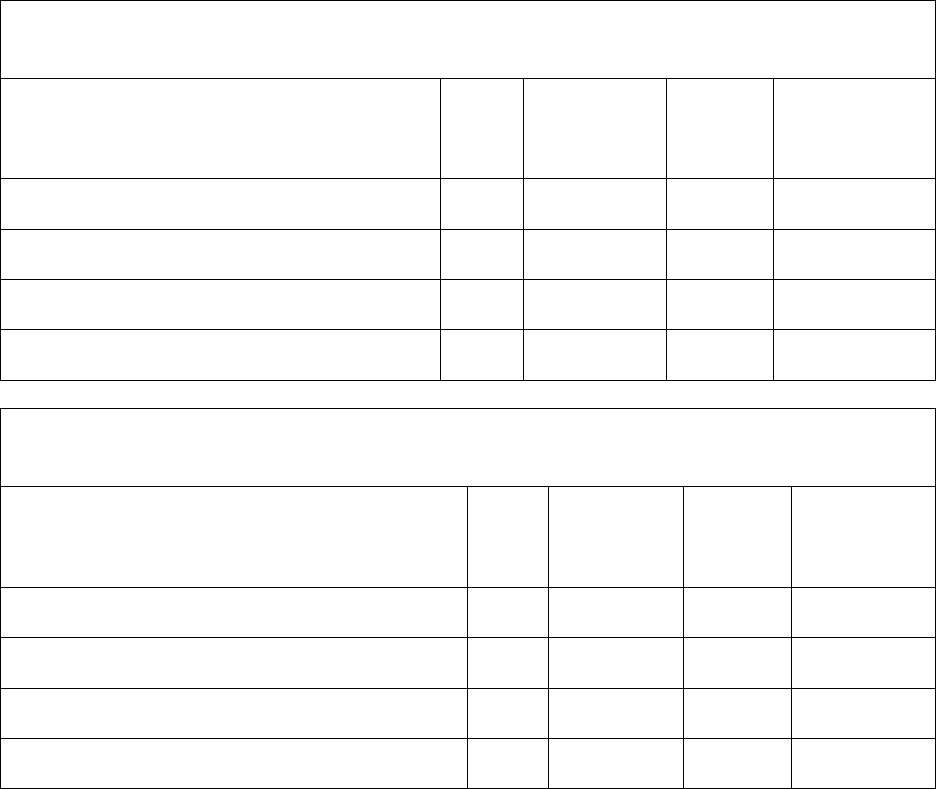

Criterion C addresses avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event(s). Criterion C

evolved between DSM-III and DSM-III-R (Exhibit L-2), with only minimal changes in language

1-8 Part 3, Section 1—A Review of the Literature

in the DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR (APA, 1994; 2000). The DSM-5 dropped the terminology of

numbing of general responsiveness in this criterion’s heading (APA, 2013).

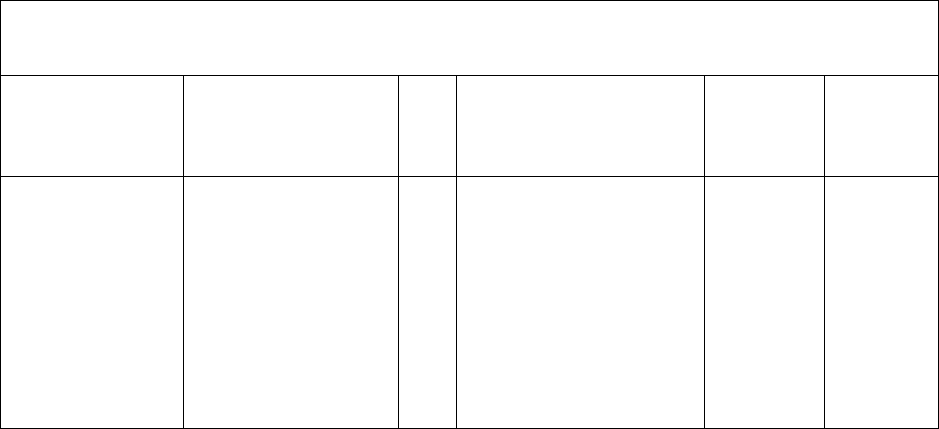

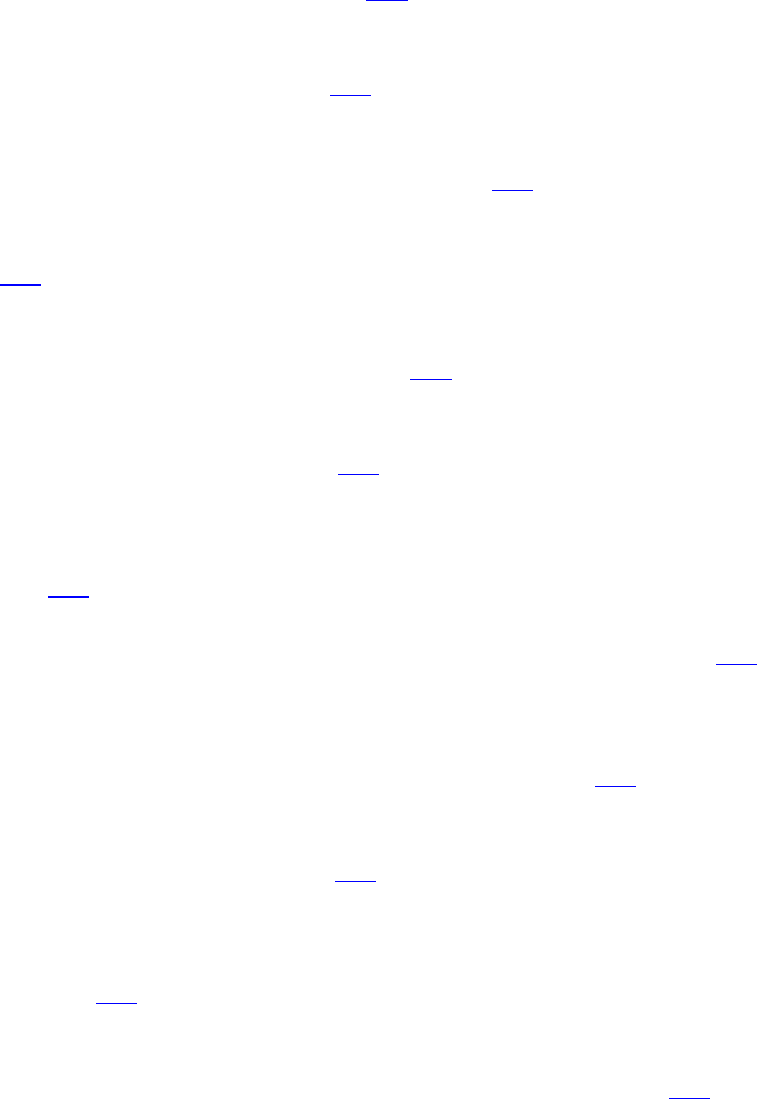

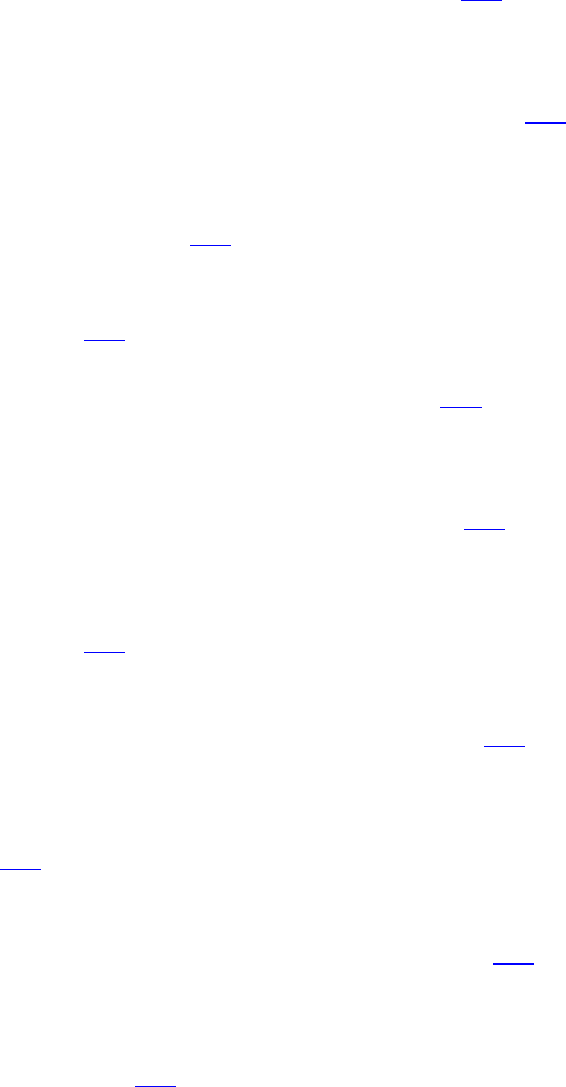

Exhibit L-2

Evolution of Criterion C for PTSD in the DSM

DSM-III (1980) DSM-III-R (1987) DSM-5 (2013)

“Numbing of

responsiveness to

or reduced

involvement with the

external world,

beginning sometime

after the trauma, as

shown by at least

one of the following:

(1) markedly

diminished interest

in one or more

significant activities

(2) feeling of

detachment or

estrangement from

others

(3) constricted

affect” (APA, 1980,

p. 238).

“Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated

with the trauma or numbing of general

responsiveness (not present before the

trauma), as indicated by at least three of the

following:

(1) efforts to avoid thoughts or feelings

associated with the trauma

(2) efforts to avoid activities or situations

that arouse recollections of the trauma

(3) inability to recall an important aspect of

the trauma (psychogenic amnesia)

(4) markedly diminished interest in

significant activities (in young children, loss

of recently acquired developmental skills

such as toilet training or language skills)

(5) feeling of detachment or estrangement

from others

(6) restricted range of affect, e.g., unable to

have loving feelings

(7) sense of a foreshortened future, e.g.,

does not expect to have a career, marriage,

or children, or a long life” (APA, 1987, p.

250).

“Persistent avoidance of

stimuli associated with the

traumatic (event(s),

beginning after the

traumatic event(s)

occurred, as evidenced by

one or both of the

following:

(1) Avoidance of or efforts

to avoid distressing

memories, thoughts, or

feelings about or closely

associated with the

traumatic event(s).

(2) Avoidance of or efforts

to avoid external

reminders ( people,

places, conversations,

activities, objects,

situations) that arouse

distressing memories,

thoughts, or feelings

about or closely

associated with the

traumatic event(s)” (APA,

2013, p. 272).

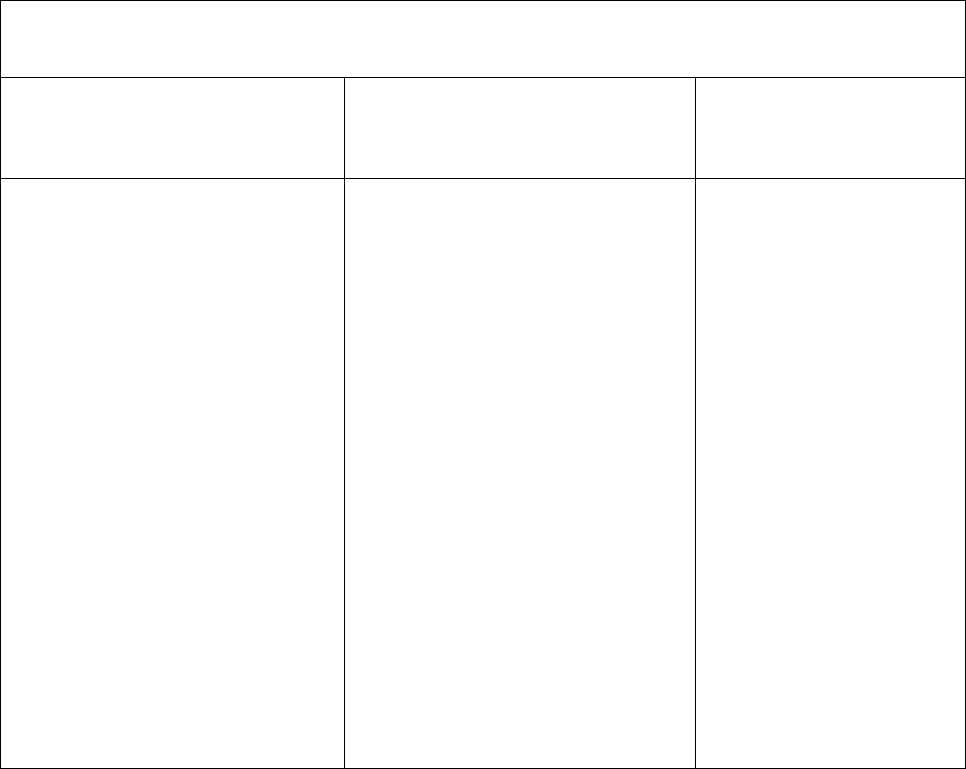

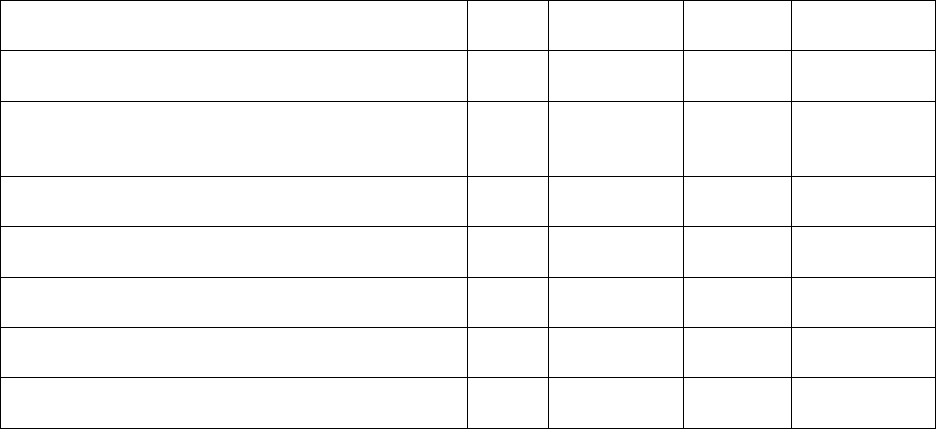

Criterion D addresses symptoms related to negative alterations in cognitions and mood

associated with the traumatic event(s). This symptom cluster is a new addition to DSM-5 and

includes “irritable behavior and angry outbursts (with little or no provocation), typically

expressed as verbal or physical aggression toward people or objects; reckless or self-destructive

behavior; hypervigilance; exaggerated startle response; problems with concentration; sleep

disturbance (e.g., difficulty falling or staying asleep or restless sleep)” (APA, 2013, p. 272). In

prior DSM publications, criterion D related to increased arousal (e.g., difficulties with sleep and

concentration). In DSM-5, this criterion has moved to Criterion E, with no other changes in

symptoms. This criterion has also evolved from the description in the DSM-III to a more concise

description in the DSM-III-R, and it has become even more concise in the DSM-IV, DSM-IV-

TR, and DSM-5 (Exhibit L-3).

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services 1-9

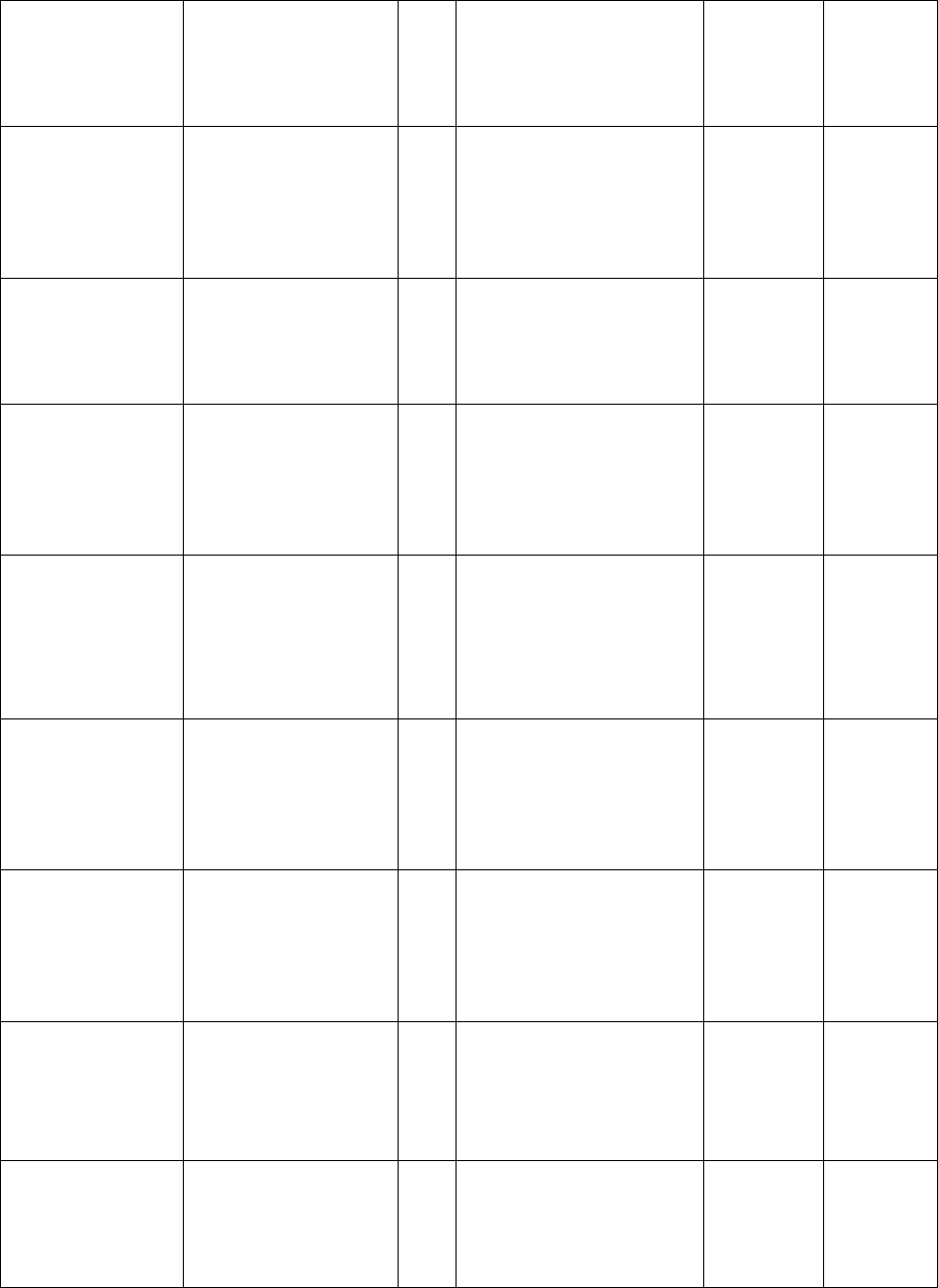

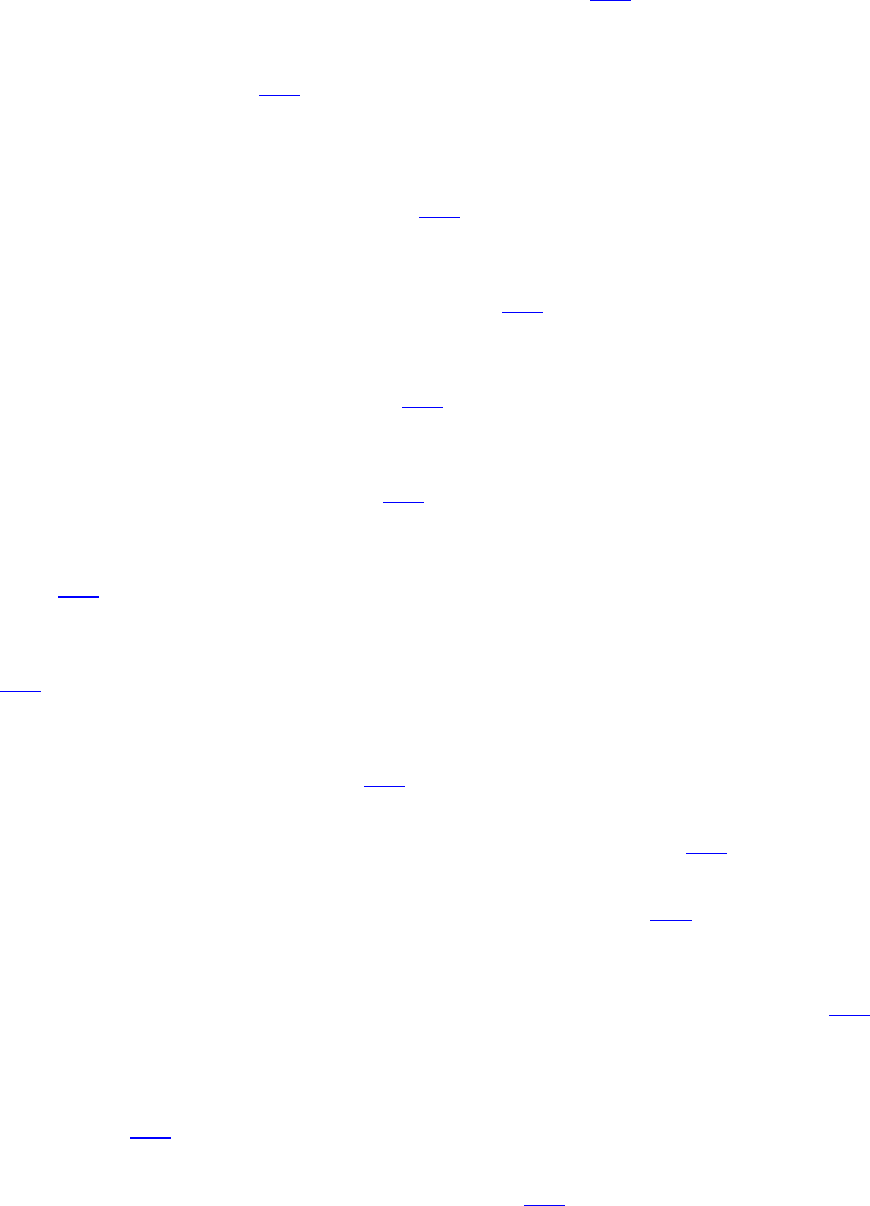

Exhibit L-3

Evolution of Criterion E for PTSD in the DSM

DSM-III (1980) DSM-III-R (1987)

DSM-IV (1994),DSM-IV-

TR (2000), and DSM-5

(2013)

“At least two of the following

symptoms that were not present

before the trauma:

(1) hyperalertness or

exaggerated startle response

(2) sleep disturbance

(3) guilt about surviving when

other have not, or about

behavior required for survival

(4) memory impairment or

trouble concentrating

(5) avoidance of activities that

arouse recollection of the

traumatic event

(6) intensification of symptoms

by exposure to events that

symbolize or resemble the

traumatic event” (p. 238)

“Persistent symptoms of

increased arousal (not present

before the trauma), as

indicated by at least two of the

following:

(1) difficulty falling or staying

asleep

(2) irritability or outbursts of anger

(3) difficulty concentrating

(4) hypervigilance

(5) exaggerated startle response

(6) physiologic reactivity upon

exposure to events that

symbolize or resemble an aspect

of the traumatic event (e.g., a

woman who was raped in an

elevator breaks out in a sweat

when entering any elevator)” (p.

250)

“Persistent symptoms of

increased arousal (not

present before the

trauma), as

indicated by two or more

of the following:

(1) difficulty falling or

staying asleep

(2) irritability or outbursts

of anger

(3) difficulty

concentrating

(4) hypervigilance

(5) exaggerated startle

response” (p. 428, p.

468, and p. 272,

respectively).

A time criterion was added in the DSM-III-R (APA, 1987) to specify a minimum timeframe of 1

month or more for experiencing symptoms in Criteria B, C, D, and E. In the DSM-IV (APA,

1994), DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000), and DSM-5 (APA, 2013), this criterion was retained, with the

slight change of requiring more than 1 month of symptoms (APA, 1994; 2000, 2013). The

criterion that addresses the level of distress and functioning was not included until the

publication of the DSM-IV (APA, 1994) and has remained the same in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013).

This criterion added a new defining characteristic, which specifies that “the disturbance causes

clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupation, or other important areas of

functioning” (APA, 2013, p. 272).

Turnbull (1998) describes the historical development of the idea of PTSD up to its inclusion in

the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 9th

Revision (1979) and the DSM-III-R. The DSM-5 recognizes certain specifiers that may further

characterize PTSD (APA, 2013). For example, a specific case of PTSD may be with delayed

expression (full criteria are not met until at least 6 months have passed since the trauma

exposure, although the onset of symptoms may immediately follow the trauma; APA, 2000;

2013).

1-10 Part 3, Section 1—A Review of the Literature

What Is Partial PTSD?

Partial PTSD is a category developed by researchers to evaluate people who have some

impairment related to elevated PTSD symptoms but do not meet full criteria for the disorder. The

term is commonly defined as either having at least one PTSD symptom from Criteria B, C, and

D that lasts at least 1 month after a traumatic event (Criterion A) or as meeting Criterion A plus

two of the other three criteria (Mylle & Maes, 2004). These authors also reviewed studies about

the prevalence of partial PTSD according to both criteria. Partial PTSD has been associated with

several of the same negative consequences associated with full PTSD, but not to the same extent

as a full PTSD diagnosis (e.g., Pietrzak et al., 2011a).

What Is TIC?

In the past 15 years, there have been many definitions of TIC and various models for

incorporating it across organizations. This TIP uses SAMHSA’s definition of TIC, which

describes this type of care involving “these key elements: (1) realizing the prevalence of trauma;

(2) recognizing how trauma affects all individuals involved with the program, organization, or

system, including its own workforce; and (3) responding by putting this knowledge into practice”

(SAMHSA, Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative, 2012, p. 4). In a seminal article on the

development of a trauma-informed service system, Harris and Fallot (2001) proposed that such a

system is one in which administrators and staff understand how traumatic experiences negatively

affect behavioral health in multiple ways and are committed to responding to those needs

through universal trauma screening, staff education and training regarding trauma and its effects,

and willingness to review and change policies and procedures to prevent the (re)traumatization

of clients.

As part of the overall review of policies, practices, and research involving trauma-informed

services for individuals who are homeless, Hopper, Bassuk, and Olivet (2010) reviewed the

literature and organizational principles on TIC and found several common themes. These

included an awareness of how symptoms and behaviors are related to traumatic experiences, an

emphasis on safety, an opportunity for individuals to develop or regain a sense of control over

their lives, and an emphasis on strengths rather than on deficiencies. They used these themes to

develop the following definition of TIC (Hopper, Bassuk, & Olivet, 2010, p. 82):

Trauma-Informed Care is a strengths-based framework that is grounded in an understanding of

and responsiveness to the impact of trauma, that emphasizes physical, psychological, and

emotional safety for both providers and survivors, and that creates opportunities for survivors to

rebuild a sense of control and empowerment.”

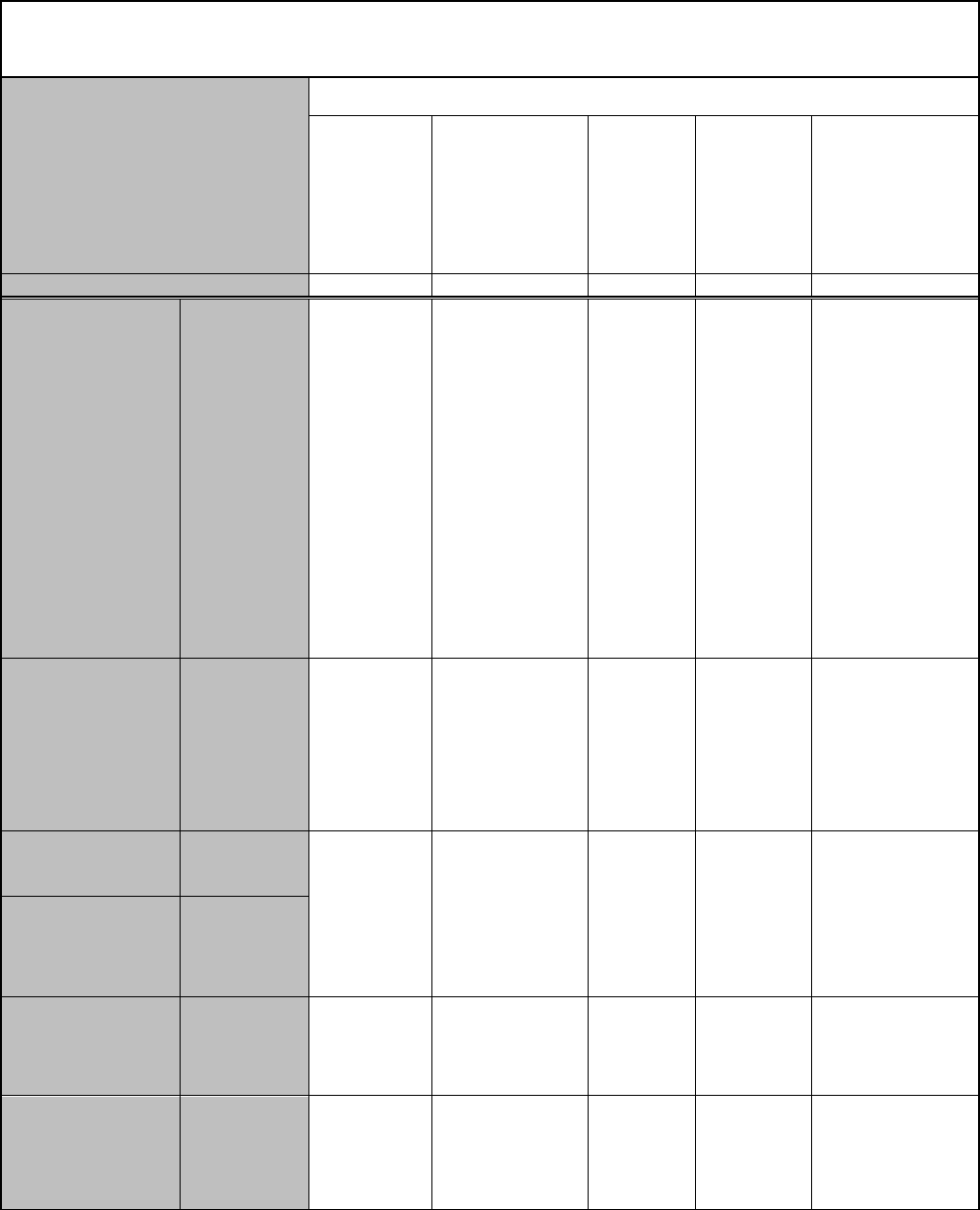

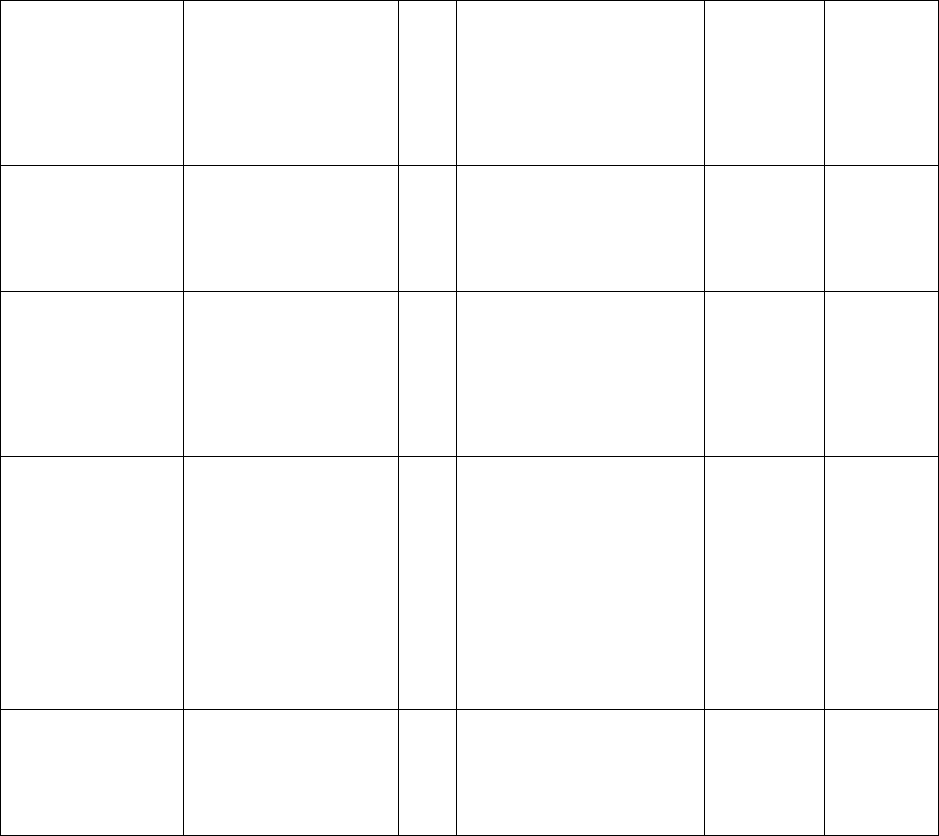

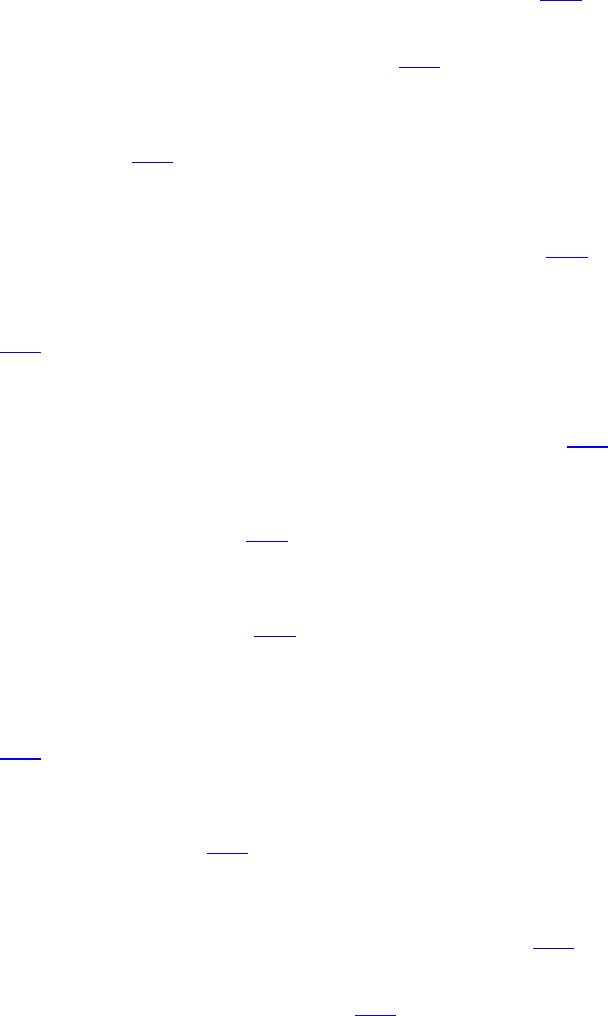

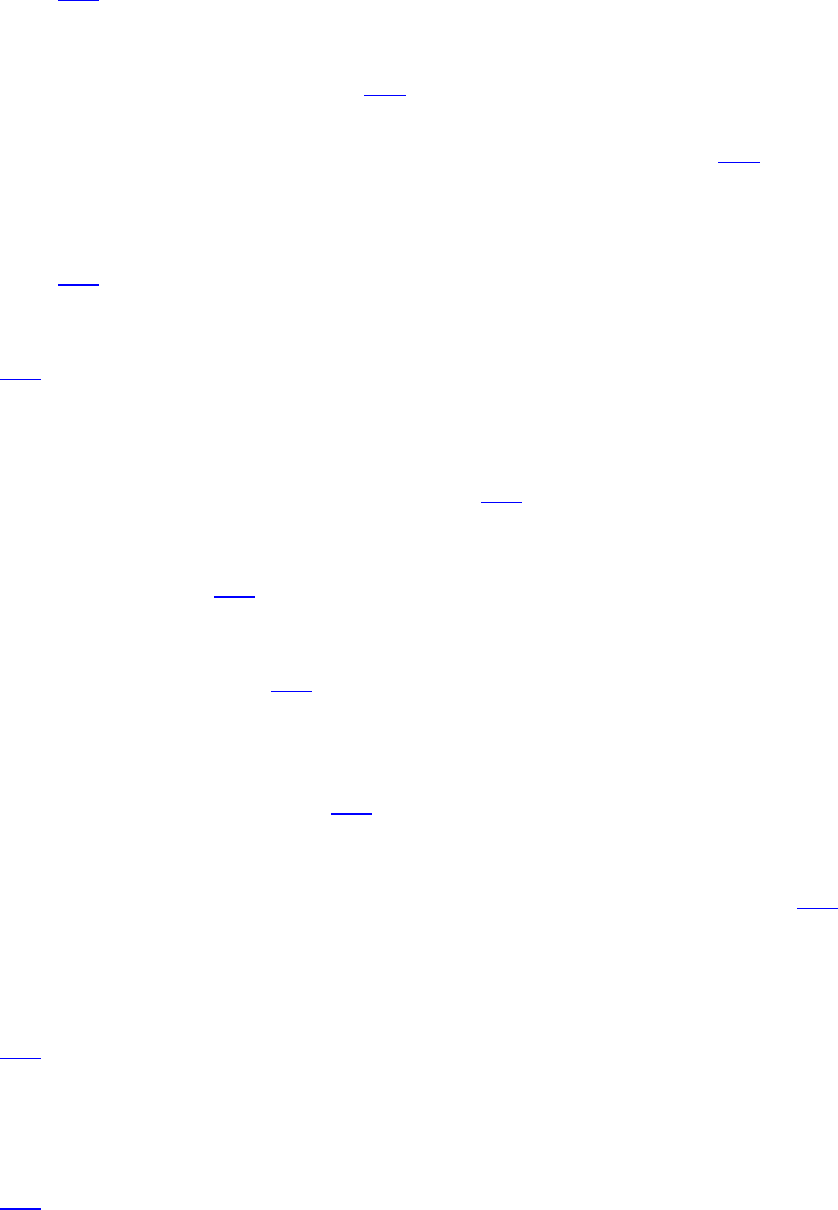

Other definitions of TIC exist, and Hopper and colleagues (2010) reviewed some of the better-

known versions of these and presented them in a table (see Exhibit L-4) for easy comparison.

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services 1-11

Exhibit L-4

Principles of TIC

Example Definitions of Trauma-Informed Care

Common Principles Across Definitions

Community

Connections:

Five Guiding

Principles for

Trauma-

Informed

Services

NASMHPD:

a

Criteria for

Building a Trauma-

Informed Mental

Health Service

System

NCTSN:

b

Principles of

Trauma-

Informed

Care for

Children

NCFH:

c

Operating

Principles for

Trauma-

Informed

Organizational

Self-

Assessment

WCDVS:

d

Trauma-

Informed or Trauma-

Denied: Principles&

Implementation of

Trauma-Informed

Services for Women

Consensus-Based Principles

Theory-Based

Expert Trauma Panel

Experts

Theory-Based

Research-Based

1. Trauma Awareness

a. Program

philosophy

and mission

Trauma function/

focus; trauma policy

or position; financing

for best practices;

trauma- informed

services; clinical

practice guidelines for

people with trauma

histories; trauma-

informed disaster

planning; systems

integration; research

& data on trauma &

evidence-based &

best- practice

treatment models;

access to evidence-

based & best-practice

trauma treatment

Recognize the impact

of trauma on

development and

coping

b. Staff

education,

training, and

consultation

Workforce

orientation,

training, support,

competencies and

job standards

related to trauma;

promote education

of professionals in

trauma

Emphasize trauma

recovery as a primary

goal

c. Practices

Trauma screening

and assessment;

Trauma- specific

services, including

evidence-based and

emerging best-

practice treatment

models

Integration

(symptoms such

as adaptive

coping,

integrating

services,

trauma-specific

services)

d. Recognition

of vicarious

trauma and staff

self- care

2. Safety

a. Physical and

emotional

safety

Safety

(physical

and

emotional)

Maintaining

clear and

consistent

boundaries

Safety, basic

needs,

consistency,

and

predictability

Create an

atmosphere of safety,

respect, and

acceptance

b.

Relationships:

authentic,

respectful,

clear

boundaries

Trustworthiness

(clear tasks,

consistent

practices, staff-

consumer

boundaries)

[see

Delivering

services

below]

Engagement:

respectful

nonjudgmental

relationships,

clear

boundaries

Use a relational

collaboration model.

Growth is fostered by

mutual, respectful,

authentic relationships

1-12 Part 3, Section 1—A Review of the Literature

c. Avoid

retraumatization

Procedures to avoid

retraumatization and

reduce impacts of

trauma

Minimize

retraumatization

d. Acceptance of

and respect for

diversity

Trauma policies and

services that respect

culture, race

ethnicity, gender,

age, sexual

orientation, disability,

and socioeconomic

status

Delivering

services in a

nonjudgmental

and respectful

manner

Cultural

competence

Work towards cultural

competence,

understand contextual

factors

3. Choice &

Empowerment

a. Choice and

control

Choice: maximize

consumer choice

and control

Consumer/trauma

survivor/ recovering

person involvement

and trauma-informed

rights

Maximizing

choice and

control for

participants

Consumer

control, choice

and autonomy

Underscore consumers’

choice and control over

recovery

b. Empower

ment model

Empowerment:

prioritize

consumer

empowerment,

skill-building, and

growth

Avoiding

provocation

and power

assertion

Open

communication:

provide

information

openly to

consumers

Use an empowerment

model

c. Consumers

nvolved in

service

development and

evaluation

Collaboration:

maximize

collaboration and

sharing of power

between staff and

consumers

Sharing power

in the running

of shelter

activities

Shared power

and governance

Involve consumers in

design and evaluation of

services

4. Strengths- based

Focus on

strengths,

resiliency

[see

Empowerment

above]

Healing, instill-

ing hope

Highlight consumers’

strengths, adaptations,

and resiliencies

Source: Hopper, Bassuk, & Olivet, 2010. Adapted with permission.

a

NASMHPD= National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors.

b

NCTSN = National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

c

NCFH = National Center on Family Homelessness.

d

WCDVS = Women, Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence Study.

Elliott, Bjelajac, Fallot, Markoff, and Reed (2005) discussed TIC within the context of services

for women and suggested some guiding principles for such services; they also briefly reviewed

literature in support of those principles.

What Is the Relationship of Culture to Traumatic Stress Reactions?

Although cultural responses to trauma may vary, high PTSD rates have been diagnosed in a wide

range of cultures following exposure to a significant traumatic event, including Ju’hoansi (i.e.,

Kalahari Bushmen) exposed to domestic violence, Cambodians who lived through the Khmer

Rouge regime, survivors of the Rwandan genocide, and Filipinos who experienced a large-scale

natural disaster (Marques, Robinaugh, LeBlanc, & Hinton, 2011). Neurobiological research also

indicates that affect dysregulation, changes in right hemisphere functioning, and a kindling

phenomenon occurs across cultures in individuals who have PTSD or a prolonged stress reaction

as the result of trauma exposure (Wilson, 2007).

Marsella and Christopher (2004) observed that intrusive PTSD symptoms appear to be more

common cross-culturally than symptoms of avoidance or the reexperiencing of trauma and that

the occurrence of the two latter categories of symptoms may vary considerably across cultures.

Other international research indicates that the presentation and occurrence of specific PTSD

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services 1-13

symptoms and the rates of other mental disorders and/or symptoms following trauma vary

considerably among nations/cultural groups (Marques et al., 2011). For example, research

conducted with Vietnamese survivors of a typhoon found that both depression and panic disorder

appeared to be more common responses to the trauma than PTSD (Amstadter et al., 2009). Other

studies conducted with Vietnamese (Hinton et al., 2001) and Cambodian (Hinton, Ba, Peou, &

Um, 2000) refugees have also found high rates of panic disorder/panic attacks co-occurring with

PTSD among trauma survivors.

Members of some cultural groups may also have increased risk for PTSD, or for certain PTSD

symptoms, compared with members of other groups. Research from the United States suggests

that Latinos have greater risk for PTSD when trauma exposure is controlled for than African

Americans, White Americans, or Asian Americans (e.g., see Marshall, Schell, & Miles, 2009). A

study conducted in the Netherlands with a diverse group of individuals affected by an airline

disaster found that those who came from non-Western cultures (n=379) experienced significantly

more health-related anxieties, more severe PTSD symptoms, more fatigue, and more impaired

health-related quality of life than did those from Western cultures (n=406; Verschuur, Maric, &

Spinhoven, 2010). Other research conducted with refugees in Finland who were survivors of

torture (N=78) found that those from southeastern European cultures had significantly more

PTSD symptoms than did those from Middle Eastern, Central African, or Southern Asian

cultures (Schubert & Punamäki, 2011).

Marsella (2010), as part of a review of the ethnocultural aspects of PTSD, noted that culture may

affect individuals’ responses to trauma by providing meaning to symptoms (e.g., nightmares), by

shaping individuals’ beliefs about traumatic events (e.g., through different concepts of destiny or

fate), by affecting individuals’ beliefs about their own responsibility for the trauma and their

subsequent response, by indicating what disabilities or impairments may result from the trauma,

and by shaping the threshold for normal versus pathological levels of arousal (e.g., through

perceptions and interpretations of stressors). He also indicated that cultural beliefs may be used

to help heal maladaptive responses to trauma. Hoshmand (2007) reviewed research that

suggested the importance of understanding cultural sources of strength/resilience when

interpreting trauma from a cultural perspective.

Because of these differences, members of certain cultural groups may not present symptoms in a

manner that can be easily identified as PTSD or another behavioral health disorder. For instance,

clinicians working with Cambodian refugees have observed that traumatic memories in the form

of flashbacks or nightmares may be interpreted as attacks by dead spirits, whereas hyperarousal

symptoms may indicate a physical or spiritual weakness (Hinton, Hinton, Pich, Loeum, &

Pollack, 2009; Hinton, Park, Hsia, Hofmann, & Pollack, 2009). Hoshmand (2007) recommended

taking an ecological approach to interpreting trauma, which means that traumatic experiences

and trauma responses are interpreted within the context of the individual’s culture and with

respect to other factors (e.g., gender, age) that might shape those responses.

Role of acculturation

Another relevant concern is the degree to which acculturation affects responses to trauma.

Research in this area is limited, but the preponderance of evidence seems to indicate that greater

acculturation is associated with lower levels of PTSD symptoms (Dunlavy, 2010). This is

contrary to the evidence relating acculturation, for some immigrant groups, to certain other

1-14 Part 3, Section 1—A Review of the Literature

behavioral health problems, notably substance abuse and depressive symptoms (e.g., Alegría et

al., 2008; Gonzalez & Gonzalez, 2008; Grant et al., 2004; Xie & Greenman, 2005). In her own

data analysis concerning African immigrants to Sweden, however, Dunlavy found no significant

associations between acculturation and PTSD symptoms.

A large study in this area was conducted in the Netherlands with a group of 221 immigrants

affected by a large fireworks explosion and a matched group of 127 immigrants unaffected by

the disaster (Drogendijk, van der Velden, & Kleber, 2012). The study found that lower

acculturation (assessed with the Lowlands Acculturation Scale [LAS]) was associated with

increased behavioral health problems for individuals who had experienced this trauma but not for

those in the control group. Specifically, a greater need to keep the norms and values of one’s

original culture (measured with a subscale of the LAS) was significantly associated with more

intrusion and avoidance symptoms (indicative of PTSD), anxiety, depression, hostility, and

somatic complaints for those affected by this trauma. For those unaffected, acculturation had no

significant association with behavioral health measures, nor were other domains of acculturation

significantly associated with PTSD symptoms, although having skills to cope with a new

culture/society and feeling socially integrated into that society were associated with better

outcomes in the other areas of behavioral health measures. The authors observed that their

findings may indicate that, in the context of a disaster affecting large numbers of people, a lack

of flexibility in terms of cultural norms and values may be a source of additional stress.

The role of acculturation vis-à-vis PTSD, however, may vary according to cultural group and the

predominant culture’s relationship to that group (e.g., it may be different for immigrant and

indigenous populations). For example, a study conducted in Taiwan with members of an

aboriginal group affected by an earthquake (N=196) found that lower levels of acculturation to

mainstream Taiwanese culture were associated with significantly higher levels of PTSD

symptoms following the disaster (Lee et al., 2009). Other studies indicate that a domain from the

Demographic and Post-Migration Living Difficulty Questionnaire labeled “difficulties adjusting

to cultural life” in a new society was also associated with greater PTSD symptom severity among

refugees in studies in Australia (Schweitzer, Melville, Steel & Lacherez, 2006) and the United

Kingdom (Carswell, Blackburn, & Barker, 2011). This domain, which evaluates feelings of

isolation, loneliness, boredom, and a lack of access to preferred foods, may also represent

difficulties in acculturation, as the sense of isolation may be greater among less acculturated

refugees who are not able to establish social connections in their new culture.

For immigrants/refugees, better acquisition of the language of their new country, which may also

represent greater acculturation, has also been associated with significantly lower levels of PTSD

symptoms among Iraqi refugees living in Sweden (N=48) but not with significant differences in

rates of PTSD diagnosis (Söndergaard & Theorell, 2004). Similarly, a study of Burmese refugees

living in Australia (N=70) found a significant association between postmigration living

difficulties, of which concern about communication problems was the most often-cited example,

and PTSD symptoms (Schweitzer, Brough, Vromans, & Asic-Kobe, 2011).

Schweitzer and colleagues (2006), in their study of 63 Sudanese refugees in Australia, also found

that support from family and others within a Sudanese community was a significant resilience

factor with regard to behavioral health, whereas social support from the larger Australian society

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services 1-15

was not. The planned TIP, Improving Cultural Competence (SAMHSA, planned c), includes

more information on the role of acculturation in behavioral health disorders and their treatment.

Types of Trauma

There are numerous forms and types of trauma. In this section, the research reviewed explores a

wide variety of traumas; however, the sheer volume of research available precludes a thorough

review of each trauma type. In addition, the order of appearance in this document does not

denote a specific trauma’s importance or prevalence, nor is a lack of relevance implied if a given

trauma is not specifically addressed in this TIP. The intent of this section is to give the reader a

broad science-based perspective on the types of trauma.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), often referred to as early childhood or interpersonal

trauma, are childhood experiences that can have a negative effect on an individual’s well-being

that often lasts into adulthood. These experiences include child abuse and neglect as well as

substance abuse and mental illness in the family, having a family member incarcerated, and

violence directed toward a parent (usually the mother; Dube et al., 2005). ACEs are associated

with significant increases in a number of negative social, behavioral health, and physical health

outcomes, including alcohol and drug use disorders, depression, suicidality, risky sexual

behavior, sexual victimization in adulthood, domestic violence, self-harm behaviors, physical

inactivity, obesity, heart disease, cancer, liver disease, sexually transmitted diseases, teen

pregnancy, homelessness, unemployment, and being both a perpetrator and/or a victim of

interpersonal violence (Dietz et al., 1999; Felitti et al., 1998; Herman, Susser, Struening, & Link,

1997; Hillis, Anda, Felitti, Nordenberg, & Marchbanks, 2000; Lalor & McElvaney, 2010; Noll,

Horowitz, Bonanno, Trickett, & Putnam, 2003; Roberts, McLaughlin, Conron, & Koenen, 2011;

Tam, Zlotnick, & Robertson, 2003).

Childhood trauma also appears to be more likely to result in PTSD than trauma experienced in

adulthood. Wrenn and colleagues (2011), using a largely African American, inner-city sample of

people who had experienced trauma (N=767), found that childhood trauma was associated with

significantly greater PTSD risk than trauma experienced in adulthood alone. Childhood abuse

was associated with even greater risk than other trauma experienced in childhood.

A major study evaluating the effects of ACEs was conducted with 17,421 members of a large

health maintenance organization (HMO) in California in collaboration with the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention (Dube et al., 2005). Two rounds of questionnaires were given,

with 7,641 respondents completing both assessments (Edwards, Anda, Felitti, & Dube, 2004). In

the initial assessment, 29.9 percent of men and 27 percent of women reported experiencing

physical abuse as children; 24.7 percent of women and 16 percent of men, sexual abuse; and 13.1

percent of women and 7.6 percent of men, emotional abuse (Dube et al., 2005). Also, 29.5

percent of women and 23.8 percent of men reported parental substance abuse, 23.3 percent of

women and 14.8 percent of men reported parental mental illness, and 13.7 percent of women and

11.5 percent of men reported violence directed toward their mothers.

The NCS and NCS-R evaluated a similar group of 12 experiences, labeled childhood adversities

(CAs), which included parental death, parental divorce/separation, life-threatening illness, and

1-16 Part 3, Section 1—A Review of the Literature

extreme economic hardship in addition to the experiences included in the ACE study (Green et

al., 2010). In this sample, 8.4 percent reported childhood physical abuse; 6 percent, sexual abuse;

5.6 percent, neglect; 14 percent, family violence; 10.3 percent, parental mental illness; 8.5

percent, parental substance abuse; and 5.8 percent, life-threatening illness (Green et al., 2010).

In a multivariate model, almost all of the CAs evaluated in the NCS were associated with

increased odds of having a mental disorder; the strongest associations were with parental mental

illness, parental substance abuse, family violence, childhood physical abuse, childhood sexual

abuse, and life-threatening illness (Green et al., 2010). These data also show a significant

association between certain CAs (i.e., parental mental illness, substance abuse in the family,

family violence, childhood physical/sexual abuse, childhood neglect, economic hardship) and the

persistence of mental disorders (McLaughlin, Green, Gruber et al., 2010a). The associations of

single trauma to mental disorders were modest, but multiple traumas had a cumulative effect, so

that exposure to multiple CAs further increased the strength of the association with both onset

and persistence of mental disorders. These same CAs were also significantly associated with

functional impairment related to behavioral health disorders (McLaughlin et al., 2010b).

Another large study, the Developmental Victimization Survey, investigated forms of childhood

abuse and maltreatment in 2,030 children and adolescents ages 2 to 17. The study found that 13.8

percent had sustained some form of maltreatment in the year of the survey; 10.3 percent,

psychological/emotional abuse; 3.6 percent, physical abuse; 1.4 percent, neglect; and 0.6 percent,

sexual abuse (Finkelhor, Ormord, Turner, & Hamby, 2005). However, some literature indicates

that all these data underrepresent the extent of childhood abuse and neglect, as both research and

expert opinion indicate that these traumas are generally underreported (see review by Gilbert et

al., 2009).

Gilbert and colleagues (2009) specifically reviewed data on psychological abuse, which is not

often evaluated in the literature. They found that approximately 10 percent of children in the

United States and the United Kingdom experience psychological abuse in any given year, and

between 4 and 9 percent sustain severe emotional abuse. Children who have sustained one type

of abuse or neglect are likely to have experienced other types as well, according to research

conducted with a variety of samples (see reviews by Edwards et al., 2003; Gilbert et al., 2009).

Research indicates that women are much more likely to sustain sexual abuse than men. Some

studies have found that men are more likely than women to sustain physical abuse in childhood

(e.g., Dube et al., 2005), whereas others did not find significant differences (e.g., Finkelhor et al.,

2005). Although childhood sexual abuse is more common for women than for men, research

evaluating outcomes for both genders has, for the most part, found similar long-term

consequences for men and women (Banyard, Williams, & Siegel, 2004; Dube et al., 2005).

Research also indicates that children living in households with yearly incomes of $20,000 or less

(in 2003–2004) are significantly more likely than children from other households to experience

psychological/emotional abuse, but not physical or sexual abuse (Finkelhor et al., 2005).

According to the same study, children from low-income families are also significantly more

likely to witness domestic violence and violence in their communities, and they are significantly

more likely to sustain violent assault or rape not perpetrated by a family member. Other research

has also found that children who are maltreated, especially those who sustain physical abuse, are

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services 1-17

more likely to be exposed to violence in their communities and to witness domestic violence;

these latter traumatic experiences have specific negative effects on children’s functioning beyond

those associated with abuse/neglect (Lynch & Cicchetti, 1998).

Different types of childhood abuse may have different behavioral health effects. In a study of

196 clients in treatment for alcohol dependence, a history of emotional abuse in childhood was

associated with a significant increase in risk for mood disorders (especially major depression)

and PTSD, physical abuse in childhood was associated with a significant increase in suicide

attempts, and sexual abuse in childhood was associated with significant increases in risk for

anxiety disorders, including PTSD (Huang, Schwandt, Ramchandani, George, & Heilig, 2012).

A study of 140 women found that those who experienced sexual abuse in childhood were

significantly more likely to engage in self-harm behaviors, those who sustained emotional abuse

were significantly more likely to be victims of sexual assault/rape in adulthood, and those who

were neglected in childhood were significantly more likely to be victims of physical abuse in

adulthood (Noll et al., 2003).

More so than other ACEs, physical and sexual abuse in childhood are associated with even

greater and more lasting problems, including significantly higher rates of depression, substance

use disorders, and PTSD in later life (see review by Gilbert et al., 2009). In addition, Gilbert and

colleagues (2009) found strong evidence linking childhood abuse with suicide attempts, high-risk

sexual behavior, criminal behavior, and obesity. As one seminal article on the effects of

childhood trauma observes, “deficits in virtually all of the major tasks of development” can

result from such abuse in childhood (Lynch & Cicchetti, 1998, p. 238). A more recent analysis of

NCS-R data that controlled for other anxiety disorders, depression, and demographic factors also

found that childhood sexual abuse was associated with significantly greater risk for social

anxiety disorder (SAD), panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), in addition to

PTSD, in adulthood (Cougle, Timpano, Sachs-Ericsson, Keough, & Riccardi, 2010). Physical

abuse in childhood, however, was only associated with significantly higher risk for specific

phobias and PTSD.

Abuse during childhood also appears to predispose individuals to further abuse and trauma as

they grow older. Sexual abuse in childhood and the severity of such abuse have been shown in a

number of studies to be significantly associated with a greater risk for sexual abuse in adulthood

(see review by Classen, Palesh, & Aggarwal, 2005). Physical abuse in childhood, to a lesser

degree, is also associated with an increased risk for sexual abuse in adulthood (Classen et al.,

2005). Women who were physically abused as children are at greater risk for being victims of

domestic violence, whereas men who were physically abused are at greater risk for being

perpetrators of domestic violence (Whitfield, Anda, Dube, & Felitti, 2003). This study, which

used data from the ACE study described previously, did not assess the relationship of child abuse

to violence perpetrated by women or sustained by men.

In addition to likely contributing to behavioral health disorders, childhood abuse may also affect

behavioral health treatment outcomes. Research conducted with 146 women who were homeless

and had substance use disorders found that those who had histories of childhood abuse (physical,

sexual, and/or emotional) had significantly worse outcomes in terms psychological functioning

(assessed with multiple instruments) and substance abuse (assessed with an instrument derived

from the Addiction Severity Index [ASI]; Sacks, McKendrick, & Banks, 2008). More

1-18 Part 3, Section 1—A Review of the Literature

information on the relationship between childhood abuse/neglect and substance abuse in

adulthood can be found in TIP 36, Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons With Child Abuse and

Neglect Issues (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment [CSAT], 2000).

Ford (2009) reviewed the neurobiological and development research that helps explain how

trauma experienced in childhood can affect the brain and how those effects may continue

throughout a person’s lifetime (see also earlier work, Anda et al., 2006). More recent studies

confirm this research. As one example, Dannlowski and colleagues (2012) found strong

associations between childhood maltreatment (assessed retrospectively using the Childhood

Trauma Questionnaire) and both decreased gray-matter volume in a number of areas of the brain

and increased response in the amygdala upon seeing pictures of threatening facial expressions.

Schumm, Briggs-Phillips, and Hobfoll (2006) reviewed three theories on why sexual abuse in

childhood has extensive and lasting negative effects: these individuals develop a generalized fear

response as a result of their inability to control or predict abuse, and this leaves them unable to

emotionally engage in interpersonal relationships; they feel worthless and perceive others as

disapproving of them; and/or they become easy targets for exploitative social networks, which

further harm their ability to trust. The authors noted that these patterns together may contribute to

problems with interpersonal relationships, which in turn affect behavioral health.

Disasters/Mass Trauma

Large-scale traumatic events like natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes, hurricanes), human

disasters (e.g., chemical spills, nuclear accidents), and terrorist attacks have unique effects

because of the number of people affected and the fact that whole communities/populations may

experience consequences (Norris, Friedman, & Watson, 2002). In addition to affecting

behavioral health, such traumatic events often involve multiple losses, including the loss of lives

(of friends and family), home, occupation/employment, health/physical well-being, and even

one’s worldview (such events may affect one’s sense of security or beliefs about the justice of

the world; Walsh, 2007).

Not all disasters/mass trauma incidents appear to have the same effect on people’s behavioral

health. In their review of 160 studies of mass trauma events, Norris and colleagues (2002) found

that rates of serious psychological impairment (measured with a number of different instruments)

were significantly higher for individuals who endured trauma from mass violence (e.g., terrorist

attacks) than for those who experienced a technological or natural disaster. Severe impairment

was also more common if the event occurred in a developing (rather than developed) country,

and, in most studies, if the individual who experienced the event was female rather than male.

DiGrande, Neria, Brackbill, Pulliam, and Galea (2010) assessed PTSD symptoms for 3,271

individuals evacuated from the World Trade Center on 9/11 by phone interview (and by face-to-

face interview for 5 percent of the sample) 2 to 3 years after the event. They found that 95.6

percent had at least one PTSD symptom and 15 percent had probable PTSD according to their

scores on the PTSD Checklist (PCL), Stressor-Specific Version. Specific experiences associated

with significantly higher odds for PTSD included witnessing a horrific incident (e.g., the airplane

hitting the towers, people falling from the building, people who were injured or killed), being

injured in the attack, being exposed to the dust cloud that resulted from the building collapse,

being above the impact zone when the attack occurred, and evacuating later rather than earlier.

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services 1-19

Another study of people affected by the 9/11 attacks that used a national sample (n=933

respondents to the 2-month follow-up assessment; n=787 respondents to the 6-month

assessment) and a Web-based survey also found that 17 percent reported at least one ASD/PTSD

symptom 2 months after the 9/11 attack; 5.8 percent reported at least one symptom 6 months

after the attack (Silver, Holman, McIntosh et al., 2002). Individuals were significantly more

likely to report symptoms if they were female, were separated/divorced/widowed, had a

diagnosed depressive or anxiety disorder, had a physical illness, had disengaged from coping

efforts, and/or had greater exposure to the actual attacks. The authors concluded that individuals

need not be directly exposed to mass trauma events for those events to have a negative effect on

their behavioral health.

Norris and colleagues (2002) reviewed information on risk and protective factors associated with

behavioral health disorders and symptoms for survivors of natural disasters and those caused by

people drawn from 160 studies published between 1981 and 2001. For the most part, these are

the same as found with other populations of trauma survivors, with possible exceptions being the

presence of children, which is a risk factor for anxiety in mothers involved in disasters (fathers

were not studied in the four articles reviewed), and the loss of material resources, which has been

found to be a risk factor for behavioral health disorder symptoms in survivors of disasters but is

rarely evaluated in studies involving other types of trauma. Such losses also appear to have a

greater effect on older adults involved in disasters (see the “People in Specific Age Groups”

section).

Domestic Violence/Intimate Partner Violence

Domestic violence or intimate partner violence, also referred as interpersonal trauma, is a major

source of trauma for women (and can affect men as well) and carries with it a high risk for PTSD

(Coker, Weston, Creson, Justice, & Blakeney, 2005). Between 2001 and 2005, intimate partner

violence accounted for 21.5 percent of nonfatal violence against women and 3.6 percent of

violence against men (Catalano, 2012). Rates of domestic violence are high for people with

behavioral health disorders, especially people with substance use disorders.

Coker and colleagues (2005) evaluated data regarding links between intimate partner violence

and PTSD taken from the National Violence Against Women Survey, a large national household

survey of 8,000 women and 8,000 men conducted in the mid-1990s (see Tjaden & Thoennes

[2000] for more information on the study). Among a subsample of men and women who were

survivors of intimate partner violence (368 women, 185 men), PTSD rates were high, with 24

percent of the women and 20 percent of the men having moderate to severe levels of PTSD

symptoms, indicating possible current PTSD (although rates of possible PTSD were higher for

women, the difference between genders was not significant). The authors also found that higher

socioeconomic status (SES), current marriage, and the cessation of intimate partner violence

were all associated with significantly lower odds of having elevated PTSD symptoms.

Research from Spain suggests a dose–response relationship between intimate partner violence

and PTSD (Pico-Alfonso, 2005); although physical, sexual, and psychological abuse from

partners were all significantly related to PTSD, the latter had the strongest relationship.

1-20 Part 3, Section 1—A Review of the Literature

Political Violence/Torture

Trauma from political violence and torture varies considerably across the globe and is common

among some refugee groups (Johnson & Thompson, 2008). Histories of torture are also common

among smaller populations, such as former prisoners of war (Engdahl, Dikel, Eberly, & Blank,

1997). Accurate data on the prevalence of such trauma in the United States is difficult to obtain,

because most major surveys do not inquire specifically about it.

Because of the high degree of interpersonal violence involved, political violence and torture

often result in traumatic stress reactions that pose particular problems for providers in terms of

treatment and assessment. In Steel and colleagues’ (2009) meta-analysis of research on trauma

and traumatic stress among refugees and others exposed to mass conflict and political violence,

of all the experiences evaluated, torture was associated with the greatest increase in PTSD risk

(more than doubling the odds of having PTSD).

Johnson and Thompson (2008) reviewed literature on the prevalence of PTSD among survivors

of political and civilian war trauma. They cited studies involving torture survivors that found

PTSD rates ranging from 18 to 90 percent of study participants. They observed evidence of a

dose–response relationship between torture and both initiation and maintenance of PTSD. This

review suggests that protective factors for PTSD that results from torture and civilian war trauma

include being prepared for torture, having strong social and family support, and having stronger

religious beliefs.

Some theories hold that having redress for torture and other political violence may help survivors

process their traumatic experiences and thus aid in behavioral health treatment (e.g., Roht-

Arriaza, 1995). However, Başoğlu and colleagues (2005) found only a relatively weak

association between the lack of redress for war-related trauma and PTSD symptoms among a

group of 1,358 civilian war survivors in the former Yugoslavia. Fears about threats to one’s

safety and beliefs about losing control over one’s life had much stronger associations with PTSD

symptoms.

The role of forgiveness in the behavioral health of survivors of torture and other political

violence may depend on the context of the violence and the object of forgiveness. Kira and

colleagues (2009) found, among a group of 501 Iraqi refugees, that those who forgave

perpetrators of violence in general as well as those who collaborated with the regime (as

measured with a modified version of the Forgiveness Versus Refusal To Forgive Scale) had

significantly better physical and behavioral health than did those who did not forgive those

people. On the other hand, forgiveness of dictators and specific individuals who were the

principal perpetrators of the violence was associated with significantly worse physical and

behavioral health outcomes.

Sexual Assault/Rape

In 2010, 1.3 percent of women age 12 and older were victims of sexual assault/rape, and it was

estimated that, in the general population, about 0.1 percent of men were victims—although there

were not sufficient data to be certain of the accuracy of that estimate (Truman, 2011). These data

are based on a general population survey that excluded the institutionalized population, which

sustains even higher rates of sexual assault/rape. For example, from 2008 to 2009, 4.4 percent of

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services 1-21

prison inmates were victims of sexual assault (Beck & Harrison, 2010). Although women are

more likely than men to be sexually assaulted even in prison, there are about 13 times as many

men as women in such facilities, so a large number of incarcerated men are affected. Among

prison inmates in 2008–2009, 1.9 percent of men and 4.7 percent of women reported being

sexually victimized by other inmates in the prior year, whereas 2.9 percent of men and 2.1

percent of women reported being sexually victimized by staff members during that period.

Histories of sexual abuse among clinical populations are also likely to be considerably more

common than in the general population (e.g., see TIP 51, Substance Abuse Treatment:

Addressing the Specific Needs of Women [CSAT, 2009b], for a review of data on sexual assault

among female clients in substance abuse treatment settings). Certain other populations, including

survivors of childhood physical and/or sexual abuse, people with disabilities, and people who are

homeless, also have a higher risk for sexual assault (Luce, Schrager, & Gilchrist, 2010).

Accurate data on sexual assault among patients institutionalized for mental disorders are difficult

to locate, but rates of sexual assault should be expected to be high in this group as well.