Resource Mobilization Information Digest

N

o

42

March 2013

Sectoral Integration in Bahamas

Contents

1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 3

Integration of biodiversity concerns in sectoral plans, policies and projects ............................................... 3

2. Agriculture Resources Sector Five Year Plan ............................................................................................ 3

3. Marine Resources Sector Five Year Plan ................................................................................................... 4

4. Forestry ..................................................................................................................................................... 6

5. Tourism ..................................................................................................................................................... 7

6. The Bahamas National Trust Strategic Five Year Plan (2008-2013) .......................................................... 8

7. Network of Protected Areas ..................................................................................................................... 9

Sectoral Coordination ................................................................................................................................. 10

8. Inter-Ministerial Coordination ................................................................................................................ 10

9. Legal and Regulatory Framework ........................................................................................................... 11

Cross-sectoral Integration (mainstreaming) Biodiversity ........................................................................... 11

10. Multi-sectoral Committees ................................................................................................................... 11

11. Co-management Partnerships .............................................................................................................. 14

12. Land Use Project ................................................................................................................................... 15

13. The Bahamas Land Use, Policy and Administration Project (LUPAP) ................................................... 15

14. Cross-sectoral Strategies ....................................................................................................................... 16

Regional Partnerships and Projects ............................................................................................................ 16

2

15. International Agreements ..................................................................................................................... 16

16. Mitigating the threat of Invasive Alien Species in the Insular Caribbean (MTIASIC) ............................ 17

17. Integrating Watershed and Coastal Areas Management (IWCAM) Project ......................................... 18

18. The Caribbean Challenge ...................................................................................................................... 19

19. Regional Initiative of The Caribbean Sub-Region for the Development of a Sub-regional strategy to

implement the Ramsar Convention ............................................................................................................ 20

20. Integration of Biodiversity in Environmental Impact Assessments and Strategic Environmental

Assessments. ............................................................................................................................................... 20

21. The Way Forward: Enhancing Cross-Sectoral Integration (Mainstreaming) of Biodiversity in The

Bahamas ...................................................................................................................................................... 21

3

1. Introduction

Bahamas reported

1

on integration of biodiversity concerns in sectoral plans, policies and projects,

including agriculture resources sector five year plan, marine resources sector five year plan, forestry,

tourism, the Bahamas national trust strategic five year plan (2008-2013), network of protected areas;

sectoral coordination, such as inter-ministerial coordination, legal and regulatory framework; cross-

sectoral integration (mainstreaming) biodiversity, for instance, multi-sectoral committees, co-

management partnerships, land use project, the Bahamas land use, policy and administration project,

cross-sectoral strategies; regional partnerships and projects, such as international agreements,

mitigating the threat of invasive alien species in the insular Caribbean, integrating watershed and coastal

areas management project, the Caribbean challenge, regional initiative of the Caribbean sub-region for

the development of a sub-regional strategy to implement the Ramsar convention; integration of

biodiversity in environmental impact assessments and strategic environmental assessments; the way

forward: enhancing cross-sectoral integration (mainstreaming) of biodiversity in the Bahamas.

Integration of biodiversity concerns in sectoral plans, policies and projects

2. Agriculture Resources Sector Five Year Plan

The Five Year Plan for Agriculture and Marine Resources (2010 - 2014) was developed with the

assistance of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States (FAO) through a Rapid

Assessment process. The Rapid Assessment entailed review of existing literature, consultations with key

stakeholders and inter-island subsector teams for specific thematic areas. The thematic areas focused

on in agriculture were: vegetables, root crops and herbs; tree crops; ornamental horticulture, livestock,

agro-processing; land and water. The policy framework for The Bahamas agriculture resources is based

on the long term development and conservation of the national agricultural resource base as well as the

protection of the country’s future capacity to produce.

The specific agriculture objectives are:

• Vegetable, root crop and herbs: Increase in production and productivity of selected

commodities for import substitution.

• Tree crops: Develop, expand and improve the existing tree crop production systems.

• Ornamental horticulture: Engagement and intensification of ornamental systems in The

Bahamas.

1

Bahamas (2011). The Fourth National Biodiversity Report of the Bahamas to the UNCBD, Ministry of the

Environment, June 2011, 139 pp.

4

• Livestock: Establish a system of integrated livestock production, allowing for access to markets

and based on principles of sustainable development so as to improve livelihoods, food security and

animal health and welfare.

• Agro-processing: To support the cottage type processing industries in the sparsely populated

Family Islands and encourage and strengthen the links between the commercial agro processors and

the farming communities to minimize the periods and levels of gluts.

• Land and water: To promote sustainable use of land and water resources in agriculture.

Management Objectives of the Agriculture Sector Plan for addressing threats to agriculture biodiversity

Invasive Species

An ornamental research and development programme will be established within the Gladstone Road

Agricultural Complex (GRAC) with the initial research priority being, to investigate possible invasive

species pathways for importations from Florida and mites which affect the Ficus species.

Recommendations from the research would be considered for improved legislation and regulatory

protocols within the industry.

Diseases

To combat diseases, the DOA will establish experimental investigations in tree crop diseases and

production systems in order to provide appropriate technologies. Measures will be taken to improve

the Tree crop research capabilities at the GRAC. In addition, a tree crop plant nursery will be established

at Bahamas Agricultural Research Centre BARC to multiply selected planting material for cultivation by

producers.

Land Conversion

Currently in The Bahamas, even though land may be zoned as agricultural land, the land may be re-

zoned and used for a different use. In order to combat this, Department of Agriculture (DOA) is

proposing the development of a land evaluation system and land zone map for agricultural lands.

3. Marine Resources Sector Five Year Plan

The policy framework for The Bahamas marine resources is based on the conservation and sustainable

use of fisheries resources and the marine environment for the benefit of current and future generations

of all Bahamians (DMR, 2009).

The specific marine resources objectives are (DMR, 2009):

• Ensure that the fishing issues are integrated into the policy and decision-making process

concerning coastal zone management;

5

• Take into account traditional knowledge and interests of local communities, small-scale artisanal

fisheries and indigenous people in development and management programs;

• Ensure effective monitoring and enforcement with respect to fishing activities;

• Promote scientific research with respect to fisheries resources;

• Promote a collaborative approach to freshwater and marine management;

• Maintain and restore populations of marine species at levels that can produce the optimal

sustainable yield as qualified by relevant environmental and economic factors, taking into

consideration relationships among various species;

• Protect and restore endangered marine and freshwater species (e.g., marine turtles);

• Promote the development and use of selective fishing gear and practices that minimize waste in

the catch of target species and minimize by-catch of non-target species;

• Cooperate with other nations in the management of shared or highly migratory stocks;

• Preserve rare or fragile ecosystems, as well as habitats and other ecologically sensitive areas,

especially coral reef ecosystems, estuaries, mangroves, sea grass beds, and other spawning and

nursery areas; and

• Develop and increase the potential of living marine resources to meet human nutritional needs,

as well as social, cultural, economic and development goals in a manner that would ensure sustainable

use of the resources.

A few of the priority areas for development are:

• Creation of a data collection system to provide necessary biological, economic and social data

for assessment and management for all major species/fisheries;

• Promote efforts to reduce the amount of Lionfish in The Bahamas;

• Approve a Government policy for aquaculture and provide the legal framework for aquaculture

in The Bahamas; and

• Consult with the public to develop a marine reserve network/national marine park network.

Management Objectives of the Fisheries Sector Plan for addressing threats to marine biodiversity:

Lionfish

In 2009, DMR in conjunction with the College of The Bahamas Marine Environmental studies Institute

(COB-MESI) developed a National Lionfish Response Plan which has been incorporated as an activity

into the 5 year strategic plan for marine resources. Through GEF funding, studies will be conducted on

6

the effects to lionfish populations and other marine species populations in areas where lionfish will be

captured and removed. An educational and outreach programme will also be undertaken to educate

people about the policies and regulations that will be developed to manage Lionfish in The Bahamas.

Illegal Fishing

To help combat illegal fishing, The Bahamas intends to conduct additional patrols and investigations

during the spiny lobster and Nassau Grouper closed seasons, to address illegal fishing in the

southeastern and northwestern areas of The Bahamas. The GOB purposes to develop the necessary

diplomatic contacts to reduce illegal fishing/poaching by Dominican Republic fishermen in the southern

Bahamas and US fisherman in the north western Bahamas.

Data (Biological, economic, social)

A data collection system is to be fully implemented by 2014 to provide the necessary biological,

economic and social data for assessment and management for all major species. A Fisheries Census will

be collected by the end of 2011 as part of the dataset. The data will be posted on the DMR website for

access to the general public.

Regulatory Review

By 2014, a regulatory review will be completed to ensure that all major fisheries are covered by

adequate regulations. Issues such as lionfish, aquaculture, and licensing requirement for certain types

of gears and vessels will be considered for incorporation into the legislation/regulations.

4. Forestry

The Bahamas has taken steps to develop a national forestry programme for the sustainable

management of all forest resources, by the enactment of the Forestry Act, 2010. The Department of

Forestry will be under the Ministry of The Environment. The Forestry Act provides protection to

wetlands, endemic flora and fauna and protected trees. The key objectives of the Forestry Act are to:

• Provide a legal framework for the long-term sustainable management of forests;

• Establishment of a Governmental forestry agency;

• Appoint a Director of Forestry;

• Establish a permanent forest estate;

• Declaration of protected trees; and

• Licensing of timber cutting activities.

The Act specifically addresses the following biodiversity concerns:

7

• Section 4 of the Act under subsections (e) (f) (g) (h) (l) and (m) mandates that the Forestry Plan

include resources assessment and continuous monitoring activities.

• Section 4 of the Act under subsection (g) and (h) mandates that the Forestry Plan include these

activities.

• Section 5 of the Act mandates that the Director of Forestry develop such plans that included

ways and means for sustaining resources.

• Section 8 of the Act classes forest into the following designations Forest Reserves, Protected

Forests and Conservation Forests

• Section 9 of the Act specifies how the Forest Management Plans are to be formulated by the

Director of Forestry.

This Act mandates that a National Forest Plan be developed every five years to govern management

activities, such as harvesting and reforestation measures, prescriptions for fire prevention, wildfire

suppression and prescribed burning and soil and water conservation. The GOB is partnering with FAO to

develop a five year National Forest Plan. The Department of Forestry has a Memorandum of

Understanding (MOU) with the BNT. The MOU provides for financial assistance in establishing

programmes to protect and manage the protected forest reserves.

5. Tourism

In 1994, a sustainable tourism policy, guidelines and implementation strategy was developed for the Out

Islands of The Bahamas by the Department of Regional Development and Environmental Secretariat for

economic and social affairs organization of American States. The purpose of the report was to “define

policies for all components of the travel industry in order to minimize impact on the environment,

restore destroyed environments and protect endangered landscapes and species” (MOT, 1994). The

report consists of a series of policies, with goals, objectives and targets, along with a road map for

achieving the policy. The policies paper addressed green management of accommodation facilities,

EIAs, protection of marine resources, water conservation, sustainable tourism planning and an

environmental educational campaign.

The green management of accommodation facilities encouraged hotels to have an environmental

statement along with an environmental programme that extended into the local community by

discouraging the use of environmentally damaging cleansing agents, and encourage energy conservation

through the use of fluorescent light bulbs and low flow water fixtures. The use of locally sourced

materials for construction and food was encouraged. EIAs were encouraged as method to assess and

preserve the ecological sustainability of the environment. The protection of the marine resources was

encouraged by requiring marinas to have pump out facilities. Water conservation was encouraged by

setting restrictions on use of freshwater lens and by recycling of the wastewater effluent and grey

water. The policy also outlined the formation of a Sustainable Tourism Development Unit. Even though

the entire plan was not implemented, MOT has undertaken projects dealing with aspects of sustainable

8

tourism, such as the Blue Flag Marina Certification Programme, The Coastal Awareness Committee and

the Birding Program.

The Blue Flag Marina is implemented through the MOT and BREEF. The Blue Flag Program is a voluntary

eco-label environmental certification program which is renewed annually for beaches and marina. The

categories in which participants are evaluated are: Environmental Education and Information,

Environmental Management, Safety & Services, and Water Quality. The major partners for this initiative

are UNEP, UNWTO, IUCN, ILS, ICOMIA, EUCC and EU. Currently, The Bahamas has 3 marinas with Blue

Flag Certification, the Old Bahama Bay (1st in the Caribbean) (5 years), Atlantis (4 years) and Cape

Eleuthera Marina (2 years).

The National Coastal Awareness Committee chaired by the MOTA is a group of stakeholders drawn from

the private and public sectors, with an aim to educate the public on the threats to our coastal

environment. Some of the activities of the project involve radio and television ads, national school

competitions, field trips for children to various ecosystems, radio and television awareness programs

and coastal clean-ups and exhibitions.

The Bird Watching Programme is an initiative between the MOT and BNT. A draft manual is being

peered reviewed. The manual will be used to train birding guides. Some of the topics covered in the

manual are how to conduct birding tours, identification of birds and trees in which birds nest.

In 2005, a sustainable tourism project for small hotels was undertaken by The Bahamas Hotel

Association. Funding was provided through a grant from the Multi-Lateral Investment Fund of the Inter-

American Development Bank. The project’s main objective was to improve the competitiveness of 10

islands that have been designated as pilot destinations in The Bahamas. The end result of the plan is to

obtain a new mix of diversified tourist products and packages appealing to specific markets such as

heritage eco, cultural and nature tourism. In Exuma, linkages were created between the farers and the

small hoteliers. As a result of the linkage, farmers started producing some of the products required for

the small hotels, allowing them to purchase local goods.

6. The Bahamas National Trust Strategic Five Year Plan (2008-2013)

The Bahamas National Trust (BNT) was established in 1959 by an Act of Parliament for the protection of

the environment. The BNT is a unique collaboration of the private, scientific, and government sectors,

and is the only non-governmental organization to manage a country’s entire national park system. The

Vision of its Strategic Plan is a “Comprehensive system of national parks and protected areas, with every

Bahamian embracing environmental stewardship” (BNT, 2007). The Plan outlines three primary

programmes (National Park Management, Public Education and Environmental Advocacy) and three

support programmes (Membership growth and Fundraising, Financial Development and Institutional

Development) all to be implemented. The goals of the projects are as follows:

9

• National Park Management – To effectively manage the nation’s system of parks and protected

areas by creating general management plans for two additional parks per year during the next five

years and by implementing programmes to reduce the impacts of invasive species.

• Public Education - To inspire greater environmental stewardship through diverse educational

programmes by implementing a public awareness programme for the sustainable use of wetlands, by

creating an accessible and comprehensive reference library on The Bahamas environment and by

developing materials and teaching resources in collaboration with the Ministry of Education and other

agencies.

• Environmental Advocacy - To advise decision-makers on ways to balance economic

development with natural resource protection by collaborating with others on critical environmental

issues and by making recommendations to the appropriate governmental agencies on environmental

issues.

7. Network of Protected Areas

Several agencies assist in the management of protected areas in The Bahamas. The DOA for the Wild

Bird Reserves, the DMR for the Marine Reserves, the MTE for Conservation of Forests and the BNT for

the system of National Parks. From the Protected Area Management Effectiveness report (2009) the

following protected areas were identified as facing the most threats and pressures are North Bimini,

South Berry Island, Exuma Marine Reserve – Jewfish, Lucayan, Inagua and Abaco and that the relatively

secure and unthreatened protected areas include Moriah, Exuma, Andros Reef, Andros Crab, Rand, and

the New Providence protected areas. Currently, there are no sustainable financing plans in place that

support the national systems of protected areas. However, the National Parks that are under the

management of The Bahamas National Trust receives $1.25 Million annually from the GOB and raises

the rest of its budget through grants, membership fees and private donations.

The existing marine protected areas in The Bahamas comprise approximately 154,011 hectares, spread

over 10 national parks and three marine reserves (BEST, 2009a). They include coastal and open ocean

sites, inclusive of seabird nesting sites, turtle nesting beaches, coastal mangroves, seagrass beds, coral

reefs and spawning aggregation sites. Species protected as a result of these areas include, but are not

limited to, the Queen Conch (Strombus gigas), Nassau Grouper (Epinephelus striatus) and West Indian

Flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber) and endemic Rock iguanas (Cyclura spp.).

In 2000, the Minister responsible for Fisheries announced the creation of five marine reserve sites North

Bimini, The Berry Islands, South Eleuthera, Exuma and Abaco. The intent of the marine reserves are for

the maintenance of marine life and habitat in an undisturbed state and for the replenishment of

fisheries while the marine parks were created primarily for the purpose of enhancing recreational use of

coastal waters. The proposed areas, all fall under category IV, Habitat/Species Management Area, of the

IUCN categories for protected area management (Fisheries website).

10

In addition to the five marine reserves, The Bahamas has nine marine parks, which are managed by BNT,

the Exuma Cays Land and Sea Park (1958); Moriah Harbor Cay, Exuma; Pelican Cays Land and Seas Park,

Abaco; Black Sound, Abaco; Walker’s Cay, Abaco; Union Creek, Inagua; West side of Andros National

Park; Andros Barrier Reef National Park; and Bonefish Pond, New Providence. The Exuma Cays Land and

Sea Park was designated a no take zone in 1986. Casual observation and scientific research

demonstrate that the fish are larger and more abundant within the park than outside of the park limits

(Sluka etal.). To help sustain the marine resources, The Bahamas has committed to protect and manage

20% of the marine resources by 2020.

Under the coordination of the National Implementation Support Programme (NISP) Committee, a

Master Plan for the National Protected Area System was created and has been presented to the GOB for

approval. This plan outlines national activities that are to be completed over the next ten years. To

facilitate the Program of Work on Protected Areas (PoWPA), The Bahamas started a Full Sized GEF

Project (2010) – “Building a Sustainable National Marine Protected Area Network” to assist in the

expansion and sustainability of the marine protected area network. The goal of the project is to expand

protected areas of globally significant marine biodiversity and increase the management effectiveness of

the national marine protected area network across the Bahamian archipelago. The three demonstration

projects are 1) controlling invasive species (Lionfish) in protected areas (DMR), 2) assessing the impacts

of climate change with mangrove restoration (TNC) and 3) building a sustainable tourism model (BNT).

The project will develop a sustainable financing mechanism for The Bahamas National Protected Area

System (BNPAS) and provide demonstration projects which address specific threats to MPAs. The

Sustainable Finance Plan for the National Protected Area System was completed in June 2008 and

recommends that a Protected Areas Trust Fund be established and administered by a professional

Trustee, such as The Bank of Bahamas Trust Company. The proposed Master Plan and Funding

Mechanisms have been presented to the GOB for approval, optimistically before the end of 2010.

Sectoral Coordination

8. Inter-Ministerial Coordination

In July 2008, The Ministry of the Environment was established. It has the overall responsibility for

coordination of environmental management activities in The Bahamas. Four departments within the

Ministry share various responsibilities. The Bahamas Environment Science & Technology (BEST)

Commission is responsible for protection, conservation and management of the environment and

manages relations with the National and International organisations on matters relating to the

Environment. The Department of Physical Planning is responsible for land use planning and review of

environmental impact assessments. The Port Department is responsible for maritime affairs and the

Department of Environmental Health Services (DEHS) is responsible for scientific research and

environment control. However, several other government ministries, departments, statutory

organizations and NGO’s have varying responsibilities for different aspects of biodiversity management

(Table 1).

11

9. Legal and Regulatory Framework

The Bahamas has a cadre of legislation, which fragments the management of environmental issues

among several public agencies. In 2010, the Forestry Act and the Planning Subdivision Bill were passed

by Parliament. The Planning Subdivision Act, requires EIAs be completed for projects that may likely

have adverse impacts on the environment. The Forestry Act establishes forest reserves, protected

forest and conservation forest. Table 2 provides key features of the legislation and the applicable

Agencies.

Cross-sectoral Integration (mainstreaming) Biodiversity

10. Multi-sectoral Committees

The Bahamas has many agencies that share the responsibility for national resource management. The

BEST Commission sub-committees bring together experts from relevant agencies. The sub-committees

are: National Implementation Support Partnership (NISP), Biodiversity, Climate Change, Science &

Technology and Wetlands. The BEST Commission itself needs to be strengthened.

The NISP Committee was established in 2004 to implement the Programme of Work on Protected Areas.

The Committee consists of The BEST Commission, DMR, BNT and TNC. A gap analysis, a management

effectiveness plan, a capacity and needs assessment, a sustainable finance plan and a master plan for

protected areas has been completed. The Master Plan with the incorporation of a Trust Fund

mechanism has been presented to the GOB for approval.

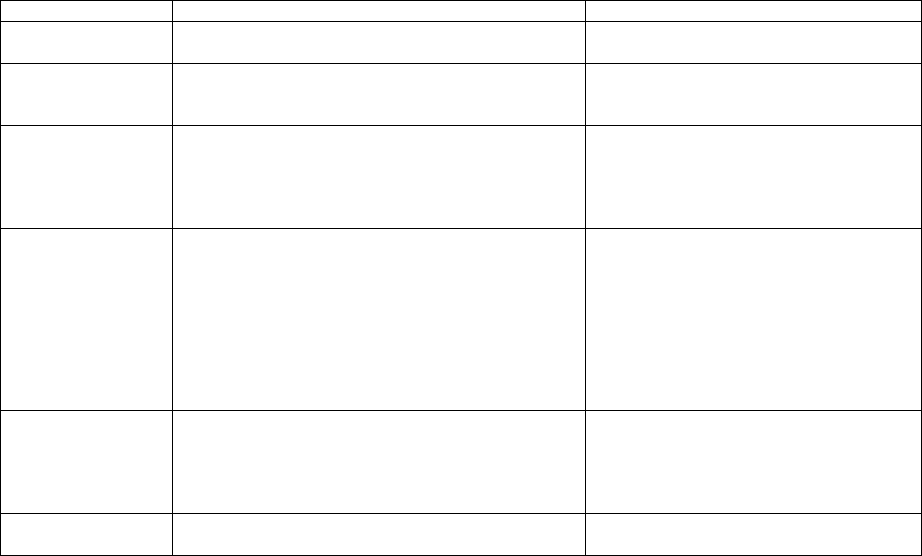

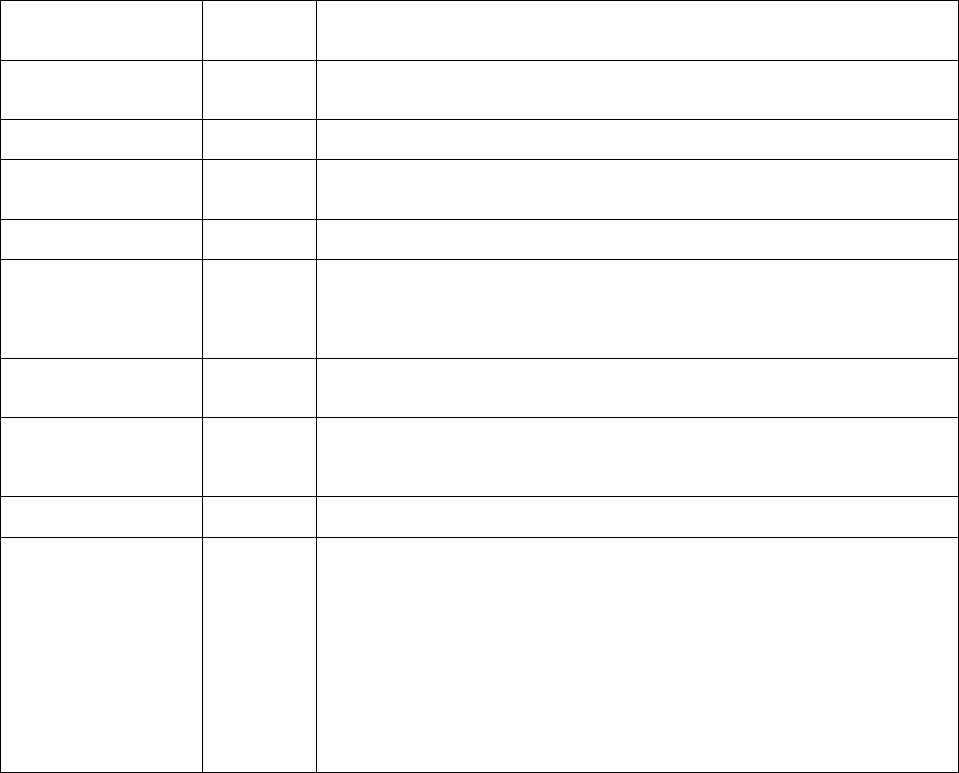

Table 1: Institutions and Legislation based on Biodiversity Management

Subject Area

Name of Legislation

Institutions Responsible

Urban Planning

Town Planning Act

Dept. of Physical Planning

Dept. of Local Government

Forestry

Penal Code

Forestry Act

Forestry Section (Ministry of the Environment)

Dept. of Agriculture

Dept. of Local Government

Agriculture

Agriculture and Fisheries Act

Animal Contagious Diseases Act

Plant Protection Act

Dept. of Agriculture

Dept. of Fisheries

Forestry Section (Ministry of the Environment)

Customs

Dept. of Local Government

Crown Lands

Lands Surveyors Act

Forestry Act

Dept. of Lands and Surveys

Dept. of Agriculture

Bahamas National Trust

Bahamas Agricultural and Industrial

Corporation

Water and Sewerage Corporation

Ministry of Housing

Dept. of Local Government

Office of The Prime Minister

Beaches

Town Planning Act

Conservation and Protection of the Physical Landscape Act

Coastal Protection Act

Dept. of Physical Planning

Dept. of Lands and Surveys

Port Department

Dept. of Local Government

DEHS

Protected Areas

Bahamas National Trust Act

Wild Birds Protection Act

Bahamas National Trust

Dept. of Agriculture

12

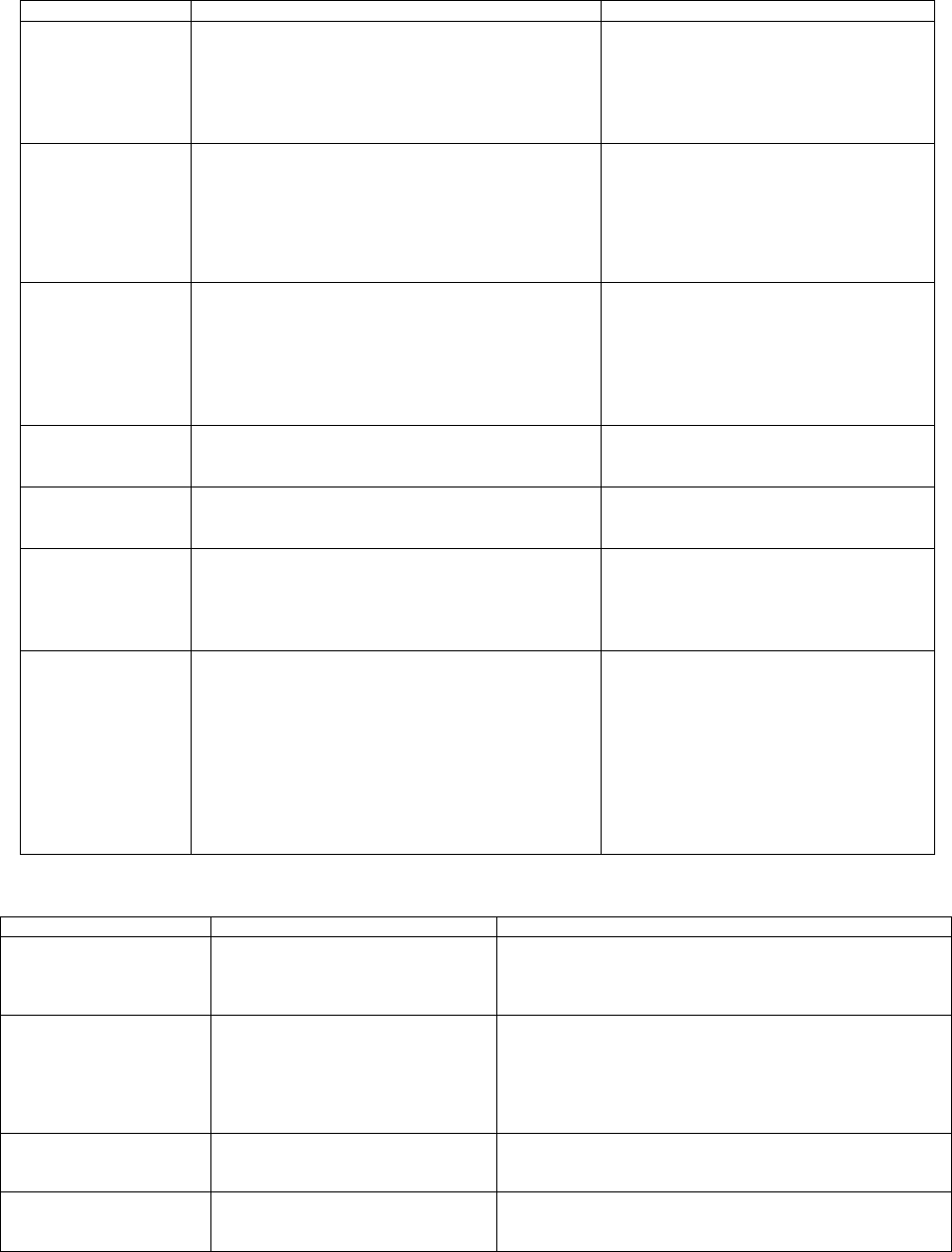

Subject Area

Name of Legislation

Institutions Responsible

Forestry Act

Plant Protection Act

Water and Sewerage Act

Fisheries Resources and Jurisdiction

Antiquities Monuments & Museums Act

DMR

Dept. of Lands and Surveys

Water and Sewerage Corporation

Dept. of Local Government

AMMC

Clifton Heritage Authority

Wildlife

Wild Animals Protection Act

Wild Birds Protection Act

Plant Protection Act

Marine Mammal Protection Act

Fisheries Resources and Jurisdiction

Wildlife Conservation and Trade Act

Bahamas National Trust

Dept. of Agriculture

Dept. of Lands and Surveys

Royal Bahamas Police Force

Dept. of Local Government

DMR

Marine Habitat

Agriculture and Fisheries Act

Fisheries Resources (Jurisdiction and Conservation Act)

Continental Shelf Act

Merchant Shipping (Oil and

Pollution) Act

Conservation and Protection of the Physical Landscape Act

Dept. of Marine Resources

Royal Bahamas Defence Force

Royal Bahamas Police Force

Bahamas National Trust

Dept. of Lands and Surveys

Port Department

Local Government

Waste Management

Environmental Health Act

Water and Sewerage Act

Dept. of Environmental Health Services

Water and Sewerage Corporation

Dept. of Local Government

Water

Water and Sewerage Act

Water and Sewerage Corporation

Forestry Section (Ministry of the Environment)

Dept. of Local Government

Land Use Development

Conservation and Protection of the Physical Landscape Act

Dept. of Physical Planning

Dept. of Lands and Surveys

Dept. of Agriculture

Ministry of Public Works

Dept. of Local Government

Fisheries

Agriculture and Fisheries Act

Fisheries Resources (Jurisdiction and Conservation Act)

Wildlife Conservation and Trade Act

Dept. of Marine Resources

Bahamas National Trust

Port Department

Dept. of Lands and Surveys

Royal Bahamas Defence Force

Royal Bahamas Police Force

Customs

MOE

DOA

Dept. of Local Government

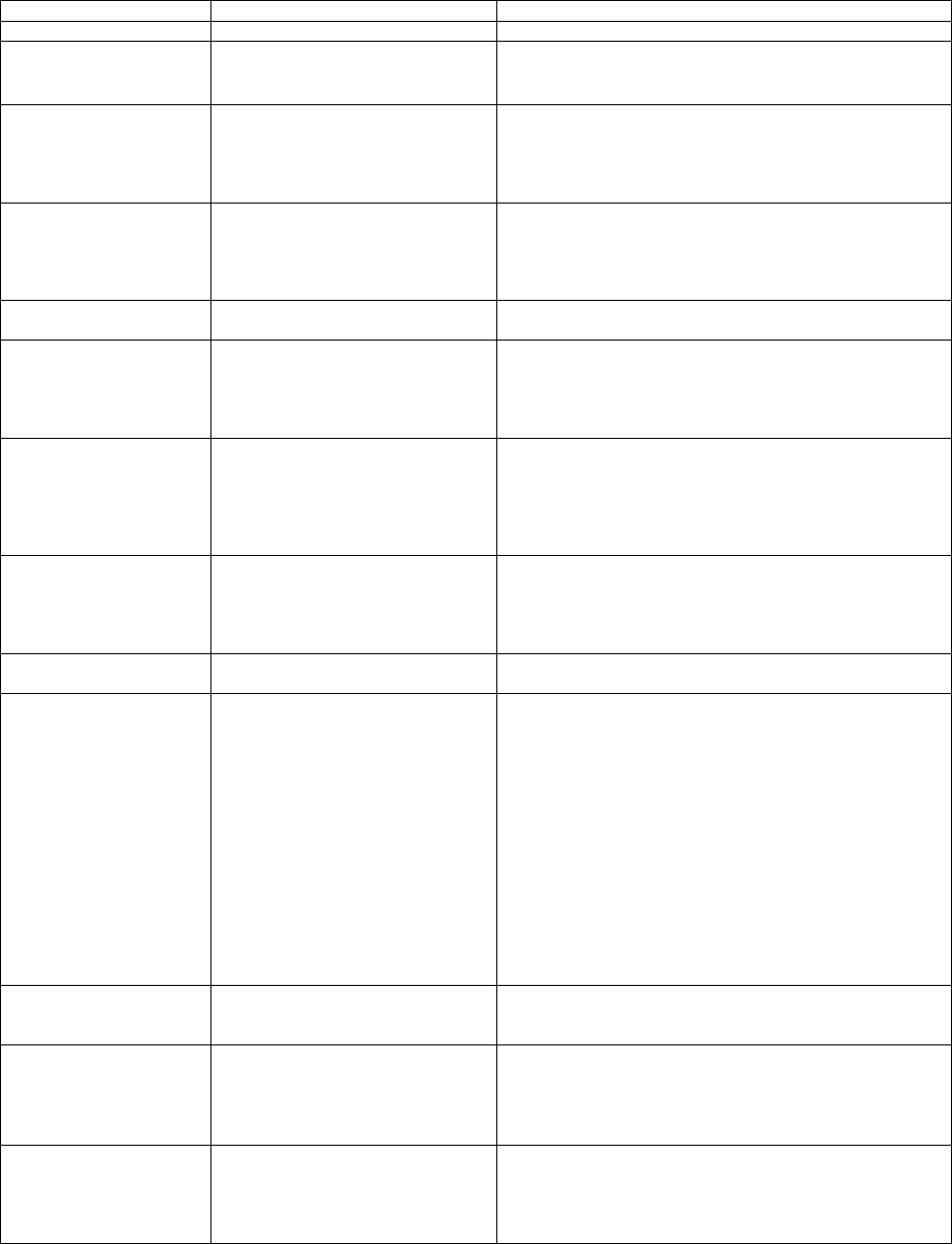

Table 2: Legal and Regulatory Framework

ENABLING LEGISLATION

AGENCY

KEY FEATURES

Continental Shelf Act, 1970

Department of Marine resources

(administration); Department of

Environmental Health Services (DEHS)

(monitors and enforces)

Protection, exploration and exploitation of the continental

shelf

Coast Protection Act, 1968

Port Department

Provides power to carry out works for the protection of the

coast (Minister responsible for Ports and Harbours)

Mandates publication of specific maintenance work being

conducted

Provides a recovery mechanism from owners of land abutting

the coast for coastal maintenance work

Archipelagic Waters and

Maritime Jurisdiction Act,

1993

Department of Marine Resources

Delineates the archipelagic waters and exclusive economic

zone of The Bahamas

Roads Act, 1968

Ministry of Public Works & Transport

Governs the removal and possession of sand from coastal

areas

Establishment and control of public roads

13

ENABLING LEGISLATION

AGENCY

KEY FEATURES

Local Government Act, 1996

Ministry of Lands and Local Government

Govern solid waste collection in the Family Islands

Freeport Bye-Laws Act, 1965

The Grand Bahama Port Authority

Regulatory oversight of sanitation and hygiene within the

Grand Bahama Port Area

Conservation of water in the Grand Bahama Port Area

Water and Sewerage

Corporation Act, 1976

Water & Sewerage Corporation

Development and control of water supply and sewerage

facilities and related matters;

Regulates the granting of licenses

Designation of water and waste control areas

Protect water resources

Environmental Health

Services Act, 1987

Department of Environmental Services

Regulatory oversight and disposal of solid and liquid wastes

Regulatory oversight of emission or discharge of contaminate

or pollutant into the environment

Facilitates a tipping fee for solid waste and environmental

levies for some imported goods

Ministry of Agriculture

(Incorporation) Act, 1993

Department of Agriculture

Provides the Minister of Agriculture powers to acquire, hold,

lease and dispose of agricultural land

Agriculture and Fisheries Act,

1963

Ministry of Agriculture and Marine

Resources

Establishment of protected areas

Management of Botanicalal Station

Prohibits export of cave earth or guano

Governs produce exchanges and packing houses

Grants powers to inspect, seize and arrest

The Wild Life Protection and

Trade Act, 2004

Ministry of Agriculture

Regulates trade in protected plants and animals

Establishes a National Advisory Committee for the

management and enforcement of wildlife protection

Governs the export and import of species listed in the

Appendices of the Convention on International Trade in

Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna

Marine Mammal Protection

Act, 2005

Marine Mammal Protection

(General) Regulations, 2005

Department of Marine Resources

Protection and conservation of marine mammals

Governs facilities with dolphins in captivity, and marine

mammal research

Governs the export, import, transport and selling of marine

mammals

Sportfishing Regulations

Department of Marine Resources

Regulates licensing, method of fishing, type of equipment and

catch limits for specific species

Fisheries Resources

(Jurisdiction and

Conservation) Act, 1977

Department of Marine Resources

Establishment of exclusive fishery zones, protected areas,

fisheries access agreements

Regulates local and foreign fishing licensing

Governs fish processing establishments, fisheries research,

fisheries enforcement and the registration of fishing vessels

Provides for conservation measures such as prohibiting the

use of any explosive, poison or other noxious substance for the

purpose of harvesting marine resources; gear restrictions;

close seasons; size restrictions of any fishery resource

Creation of new regulations for the management of fisheries

as and when necessary (Minister responsible)

Prohibits taking, having in one’s possession, buying or selling

any marine turtle, any part of a marine turtle and marine turtle

eggs

Protects the nest of a marine turtle

Fisheries Resources

(Jurisdiction and

Conservation) Regulations

Department of Marine Resources

Prohibits fishing or molesting for marine mammals

Limits the size of the sponges

Governs aquaculture and sport fishing licensing

Wild Animals (Protection)

Act, 1968

Ministry of Agriculture and Marine

Resources; Ministry of the Environment

Governs the removal and export of wild animals such as:

Wild horses (on Abaco Island) and any member species

(Equus Caballus)

Agouti or Hutia (Geocapromys ingrahami)

Iguana (Cyclura species)

Wild Birds Protection Act,

1952

Ministry of Agriculture and Marine

Resources

Ministry of the Environment

Govern hunting licenses and wild bird research

Provides for conservation measures such as closed seasons; kill

and catch limits

Designation of wild birds protected areas and appointment of

game wardens

14

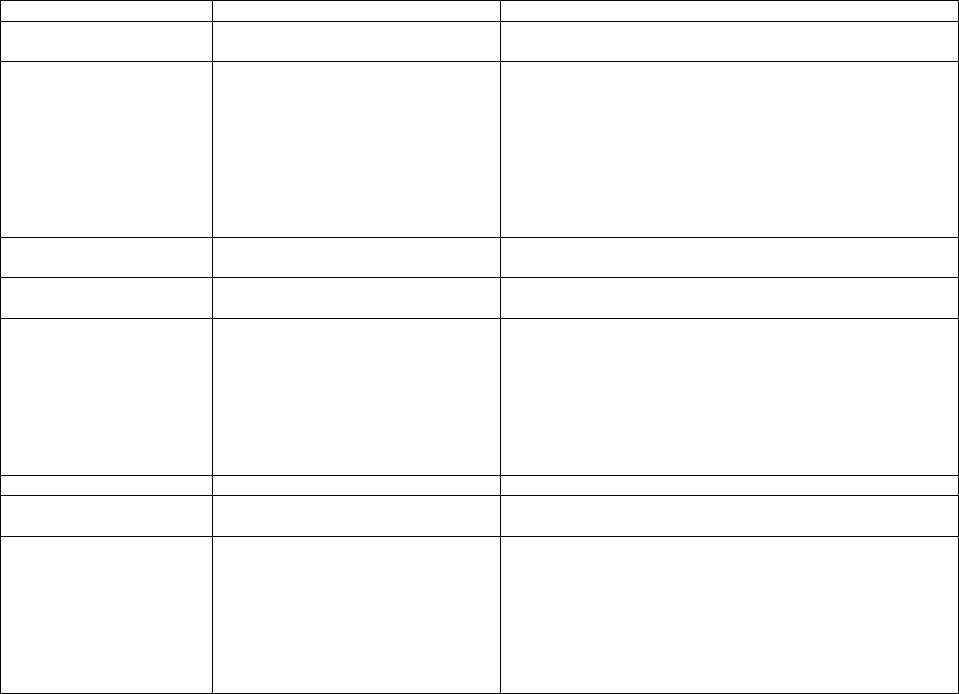

ENABLING LEGISLATION

AGENCY

KEY FEATURES

Plants Protection Act, 1916

Department of Agriculture

Govern the importation, detention and examination of plants

Control of pests and diseases injurious to plants

Conservation and Protection

of the Physical Landscape of

The Bahamas Act, 1997

Department of Physical Planning

Protects physical landscape from environmental degradation,

regulates filling of wetlands, drainage basins or ponds,

prohibits digging or removing sand from beaches and sand

dunes

Regulates excavation, landfill, quarry/mine operations and

indiscriminate land clearing and issuance of permits

Management of protected trees

Levies fines for illegal movement of sand, trees, vegetation

and excavation

Merchant Shipping (Oil

Pollution) Act, 1976

Port Department;

DEHS (nearshore)

Governs the provision concerning oil pollution of navigable

waters by ships

The Bahamas National Trust

Act, 1959

The Bahamas National Trust

Management of parks and protected areas;

Protection of places and buildings of historic interest

Planning and Subdivision Bill,

2010

Department of Physical Planning

Ministry of The Environment

Ensuring appropriate and sustainable use of all land

Providing for the orderly sub-division of land

Protecting and conserving the natural and cultural heritage of

The Bahamas

Governs the preparation of Land-use plans for each island, the

preparation physical plans, development control and

regulation, environmental impact assessment and

miscellaneous matters

Registered Land Bill, 2010

Department of Lands & Survey

Govern the registration and transfer of land

Animal Protection and

Control Act, 2009

Animal Control Unit of the

Department of Agriculture

Establishes an Animal Protection and Control Board

Protecting animals from cruelty

Forestry Act, 2010

Ministry of the Environment

Management of the National Forest Estate

Development of management systems compatible with

conservation

Protects rare and endangered species and threatened

ecosystems

Requires an EIA for consideration of an alternate land use

Issues permits for harvesting of protected trees

Governs forestry on private lands

11. Co-management Partnerships

The Government of The Bahamas has partnered with various Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs)

for sustainable development and conservation of biodiversity ecosystems. The Department of Marine

Resources (DMR) continues to work with The Bahamas National Trust (BNT) to implement the “Master

Plan for The Bahamas National Protected Area System.” The DMR partners with TNC and BNT for

meeting the requirements of “The Caribbean Challenge” and the “UN convention on Biological

Diversity.”

The DMR partnered with The Bahamas Marine Exporters Association and TNC for the Lobster Fisheries

Implementation Project (FIP). The project resulted from an independent pre-assessment of the lobster

fishery against Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification standards. The pre-assessment showed

that the lobster fishery would not be likely to attain MSC certification. As a result the FIP was developed

to address the various shortfalls in the way the fishery is managed with hopes that MSC certification and

better management result. Multiple areas are addressed as a part of the FIP including data collection,

outreach, monitoring, enforcement, stock assessments and management. The hope is that MSC

certification will allow the Bahamian lobster fishery to maintain access to foreign markets and at

minimum result in greater assurance that the fishery is well managed.

15

The GEF Full Size Project – “Building a Sustainable National Network of Marine Protected Areas” is being

implemented by BEST, DMR, TNC and BNT. The project life is four years and funding is provided by GEF.

12. Land Use Project

“In 2010, a new Planning and Subdivision Act 2010 was enacted by Parliament, which consolidated all

aspects of town planning and subdivisions; including regulations for a revised and restructured

Department of Physical Planning and Town Planning Committee, a new Appeals process and public

participation. A key component of this new law is provisions for land use plans to be prepared for every

Family Islands. The Act sets out what shall comprise a land use plan, which must be consistent with the

National Land Use Development Policies (First Order, 2010).”

To assist in creating the land use plan, first order existing land use maps were created from the

compilation of all existing land use and land resources datasets and information in the country, that was

collected from relevant governmental agencies. For large tracts of land privately owned, the owners

were consulted to ascertain their plans for developing their landholdings. Designations such as

Agriculture, Forest, Green Spaces, Conservation Forest, National Parks, Restricted

Development/mangroves, Heritage Site, Industrial, Residential and Commercial were assigned to the

zoning maps. See Figure 3.2 for the zoning areas assigned for New Providence. One of the major

outputs of the project is the creation of land use and zoning maps, which would be accessible online to

accompany the Land Use Plan. Maps will be created for all of The Family Islands.

13. The Bahamas Land Use, Policy and Administration Project (LUPAP)

The LUPAP project began in 2005 and ended in October 2009. The project’s goals were to improve the

efficiency of land administration and land information management in The Bahamas, prepare modern

land legislation and policy guidelines for the GOB, and thereby contribute to the improved use of land

resources in The Bahamas. The four main components of the project were: 1) land administration

modernization (LS); 2).land information management (and the re-activation of the BNGIS Centre); 3).

the development of national land issues and policy guidelines (LS); and 4) a PCU management – crown

land policy study, crown surveys & GPS (LS). The project was implemented by the Department of Land

Surveys (LS) and the BNGIS Centre (Component 2 Land Information Management only).

An “Initial Global satellite” system was established, as part of a new geodetic infrastructure, for all types

of surveys across the 5 major islands, as well as the development of a new datum (WGS 84 ITRF05

replacing the old North American datum of 1927) was created under LUPAP Component 2. A National

GIS Strategy was conceptualized in consultation with the Geospatial Advisory Committee which

promotes the vision for a comprehensive Bahamas Spatial Data Infrastructure (BSDI), along with draft

legislation for the BSDI with BNGIS as the lead agency.

Under LUPAP Components 1 and 3 executed by the Lands & Surveys Department land use issues and

policy guidelines have been created, but are underutilized in the planning process. Additionally access

to the Parcel Information Management System (PIMS) for New Providence and Grand Bahama which

contains information on crown lands, private lands and land use data is somewhat restricted. Although

16

the LUPAP completed the collection of Geospatial data on Inagua which was widely distributed to all

GAC member agencies the data collected on Abaco and Andros was not complete. Maps were produced

identifying conservation and ecologically sensitive areas for the entire Bahamas by BNGIS and will be

presented to GOB for approval. Even though the BNGIS has been re-activated, the information provided

to the BNGIS Centre from custodian agencies such as The Lands & Surveys 2004 ortho-imagery and

vector datasets, the Centre is not authorized to distribute this information to the general public. In

addition, the government agencies would have to submit a formal request for information. LUPAP was

Funded the by a loan from IDB as well as counterpart funds provided by the Centre.

14. Cross-sectoral Strategies

The Bahamas has not developed other national and sub-national strategies and programmes, such as a

Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper or a National Plan for Achieving the Millennium Development Goals

but is seeking to conserve its environment and improve coastal management (World Development

Indicators, 2003). A Draft National Action Programme to Combat Land Degradation was developed and

shelved.

Regional Partnerships and Projects

15. International Agreements

The Bahamas is a party to approximately twenty (20) International Agreements that deal with

environmental and public welfare issues. From a national perspective, The Bahamas is actively involved

in the following Conventions:

• Ramsar Convention – The Bahamas has developed a draft policy on wetlands that seeks to

balance conservation and development efforts and promote greater public awareness. The Bahamas

has also designated the Inagua National Park a Ramsar site, which limits the type of development in and

around the park.

• The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change – The Bahamas has developed a

National Climate Change Policy and is in the process of completing the 2nd National Report for Climate

Change. The report will include a national inventory of anthropogenic emission sources.

• United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification – A draft National Action Programme to

address land degradation has been developed, but has not received government’s approval.

• The Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) – In December 2004, the

Wildlife Conservation and Trade Act (2004) was passed by Parliament to implement CITES in The

Bahamas. This Act allows the Department of Agriculture (the managing authority) to assume

responsibility for implementing CITES in The Bahamas. Included among the implementation duties are:

the coordination of implementation and enforcement legislation relating to conservation of species, the

establishment of a scientific authority to advise on the import and monitor the export of species and the

17

appointment of a national advisory committee to advise the Minister responsible for agriculture on

matters relating to the Act and the implementation of CITES.

• The United Nations Convention on Laws of the Sea (UNCLOS) - The BNGIS Centre continues to

play a pivotal role in providing the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with GIS technical expertise in conducting

desktop studies for the establishment of the Country’s Maritime Border (Published with the United

Nations December 2009). The Centre also conducted desktop studies on UNCLOS Article 76 “outer

limits’ of the continental shelf and beyond” which resulted in The Bahamas submission of its claim to the

Continental Shelf to the United Nations. Further as a member the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Delegation

for the resumption of talks with Cuba, The BNGIS Centre continues to perform complex geodetic

calculations utilizing specialized modeling software for map reproduction to support The Bahamas

position. This work continues with the latest talks taking place in September 2010 with The Republic of

Cuba Officials. Future talks with Cuba and the Turks and Caicos Islands are anticipated.

A list of the policies and strategies with key features are provided in Table 3.

16. Mitigating the threat of Invasive Alien Species in the Insular Caribbean (MTIASIC)

The MTIASIC project is a regional project between The Bahamas, The Dominican Republic, Trinidad and

Tobago, St. Lucia and Jamaica for the development of a regional invasive species strategy based on

terrestrial, marine and freshwater invasive species. Each country will design a project to either

control/manage or eradicate/prevent the chosen invasive species. The results from the individual

projects would provide input into the regional strategy for combating aquatic and terrestrial invasive

species in the wider Caribbean. The project has a five year life span from 2009-2013 and is funded by

GEF and is implemented by UNEP and Centre for Agricultural Bioscience International (CABI).

The Bahamas’ component will consist of a population control experiment, the development of a Lionfish

collection and Handling Protocol, research into the lionfish ecology, policy and regulatory reform to aid

Lionfish Management and a public education and awareness campaign. The population control

experiment will monitor and determine the effect of lionfish removal, frequency on lionfish densities

and on native fish diversity and food web structures. The study sites are located in New Providence,

Eleuthera, Abaco and Andros. The project provides training of local persons to assist in the underwater

assessments of biodiversity at the study sites. The project involves the Department of Marine

Resources, some of the local NGOs: BEST, BNT, Stuart Cove, BREEF, TNC, along with international

partners from REEF, Simon Fraser University and the University of Oregon.

Table 3: Policies and Strategies

POLICY / STRATEGY

CABINET

APPROVAL

DATE

KEY FEATURES

The Bahamas National

Energy Policy

November

2009

Recommends measures to make the country more energy efficient by utilizing more

sustainable sources of energy

National Policy for the

Adaptation to Climate

Change

March 2005

Recommends steps to be taken to combat climate change as it relates to agriculture,

coastal and marine resources and fisheries, forestry, terrestrial biodiversity, tourism and

water resources.

18

POLICY / STRATEGY

CABINET

APPROVAL

DATE

KEY FEATURES

National Environmental

Management and Action

Plan

August 2005

Outlines how consideration of conservation and sustainable use of biological resources can

be integrated into national decision making through the identification of appropriate

administrative structures and involvement of technical and scientific advisors

National Clearing House

Mechanism

June 5, 2005

Facilitate the exchange and cooperation with other partners on biodiversity information

Draft National Action

Programme to Combat

Land Degradation

DRAFT

Identifies some issues of concern within local communities and aims to develop activities

to remedy the negative effects of land degradation in specific ecosystems.

National Environmental

Policy

2005

Highlights five basic principles to guide the environmental policy of The Bahamas

Deals with conserving the diversity, integrity and productivity of natural resources

Road Map for the

Advancement of Science

and Technology in The

Bahamas

March 2005

Presents the Science and Technology Policy

Outlines goals for Science and Technology within the educational system and indicators of

progress and achievement

Promotes the popularization of Science, Technology, Environmental Protection and

Sustainable Development

National Invasive Species

(Policy and) Strategy (NISS)

October 28,

2003

Code of conduct for various categories of stakeholders

Recommends five plant species and two animal species for eradication

Recommends sixteen plant species and six animal species for control and management

Pollution Control and

Waste Management

Regulations

2000

Regulates releases of certain hazardous wastes, contaminates and pollutants

Establishes water quality and air quality criteria

Governs discharge and hazardous waste management permits, packaging and labeling

standards

National Oil Spill and

Contingency Plan

2000

Manage oil spills in territorial waters to minimize damage to the environment and

biodiversity

National Biosecurity

Strategy (NBS) The

Commonwealth of The

Bahamas

DRAFT

Interconnects activities outlined in the NISS and the NBSAP

Highlights priorities and threats to Biosecurity, along with commercial and economic

opportunities arising from Biosecurity

Draws attention to Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) issues such as the need to regulate

access to and benefits derived from biological and genetic resources in The Bahamas

Establishes a sequenced approach to invasive species control

Outline measures that should be implemented for the Protection of traditional knowledge

Includes a Biosecurity Act for the eradication of effective management of unwanted

organisms within The Bahamas, and governance of the entry of all alien organisms.

Provides regulations for: management of unwanted organisms and for the control and

management of GMO’s, conservation and sustainable use of biological resources, access

and benefit sharing and protection of traditional knowledge.

17. Integrating Watershed and Coastal Areas Management (IWCAM) Project

The regional IWCAM project commenced in 2005 and involves thirteen (13) of the Small Island

Developing States (SIDS) in the Caribbean. The project is funded by GEF and implemented by UNEP and

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The goal of the project is to strengthen the

commitment and capacity of the participating countries, to implement an integrated approach to

management of watershed and coastal areas. The main issues addressed by IWCAM are diminishing

freshwater supplies, degraded freshwater and coastal water quality, inappropriate land use and hygiene

and sanitation. Two of the eight demonstration projects are being implemented by The Bahamas. In

Andros, the Land and Sea Use Planning for Water Recharge Protection and Management and in Exuma,

The Marina Waste Management at Elizabeth Harbor, these demonstration projects commenced in

January 2007.

The Exuma project focuses on waste disposal in one of the Caribbean’s busiest harbours. This harbour

has up to 500 marine vessels per day during the peak yachting season in November through April. A

Fixed Activated Sludge Treatment wastewater system with a deep well disposal was installed and is

19

waiting commissioning before the 2010-2011 yachting season. The facility will receive waste from a

pump out boat which operates in Elizabeth Harbour. As an interim measure, Sandals resort accepts the

wastewater collected by the pump out boat. Also, 15 moorings for dockage have been installed in

Gaviota Bay, Elizabeth Harbor to prevent boaters from docking on sensitive marine areas. A harbour

inspection and coastal water quality monitoring program was established by the DEHS. Baseline water

quality data has been collected for comparison to water samples collected during the upcoming yachting

season. This component is being implemented by the BEST Commission, the Water & Sewerage

Corporation, BREEF and DEHS.

Andros is home to The Bahamas’ largest freshwater aquifers, vast tidal creek wetlands, and one of the

world’s largest barrier reefs and to a nursery that supports diverse sea life well beyond Bahamian

territorial waters. Andros represents the largest source of freshwater and wetland habitat in The

Bahamas. The main threats to the water regime and related biodiversity include pollution of the

aquifer (salt water intrusion, agriculture, sewage, unsanctioned domestic use, and puncture as a result

of development), encroachment, and destruction of sensitive habitats, dredging, and over-fishing. The

Andros project focuses on managing the sensitive coastal and fresh water resources. A small scale

demonstration project dealing with water conservation will be completed with the North Andros High

School agricultural programme. Composting toilets and mechanical low flow faucets are being installed

at the High School. The project will also provide a zoning map for land and sea areas for future use, an

Ecotourism Plan, baseline information on the marine and terrestrial resources, maps showing the

location of the biodiversity, an economic valuation of resources and biodiversity on Andros, and a water

conservation strategy. The TNC conducted an awareness and educational programme to sensitize the

community to the project benefits.

18. The Caribbean Challenge

In May 2008, The Bahamas’ government alongside leaders from Jamaica, Grenada, The Dominican

Republic and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, launched the Caribbean Challenge. The Caribbean

Challenge is an unprecedented commitment by Caribbean governments to build political support and

financial sustainability for protected areas in the Caribbean. The Bahamas will be the largest contributor

of protected areas and aims to set aside 20% of the marine habitats by 2020. The goals of the project

are to create a network of marine protected areas expanding across 21 million acres of territorial coasts

and waters, to establish protected areas and trust funds to ensure sustainable funding and to develop

national level demonstration projects for climate change adaptation. The GOB has committed $2 million

dollars for the establishment of The Bahamas National Protected Area Fund. Funding has also been

committed by The Nature Conservancy, KfW (the German Development Bank) and other international

funding agencies (BNT, 2010a). The aim is to end paper parks in the Caribbean forever. The project is

supported by the Global Island Partnership and private NGO’s.

20

19. Regional Initiative of The Caribbean Sub-Region for the Development of a Sub-regional

strategy to implement the Ramsar Convention

The goal of the project is to create a sub-regional strategy for implementing the Ramsar Convention by

dealing in a comprehensive manner with challenges that climate change, biodiversity loss,

socioeconomic development, conservation and wise use of wetlands and coastal areas entail for

Caribbean States. The Strategy will provide guidelines for the development and establishment of a

coordinated international cooperation framework, the processes and actions for the handling,

management and exchange of experiences best practices and information to address in a regional

manner the problems and challenges associated to the management of wetlands in the Caribbean Sub-

region. This project is in its initial phase.

20. Integration of Biodiversity in Environmental Impact Assessments and Strategic

Environmental Assessments.

Under the Draft Environmental Planning and Protection Act of 2005, Environmental Impact Assessment

(EIA) Regulations were developed. Even though the EIA regulations were not legally enforceable,

foreign developers were required to undertake an EIA and EMP. A review of the documents were

conducted by the BEST Commission in tandem to a third party reviewer.

The Planning and Subdivision Bill 2010, provides a mechanism for consideration to be given to

environmental impacts from national projects, by requiring EIAs for projects that may likely have

adverse impacts on the environment. The legislation mandates that the EIA be circulated to relevant

referral agencies for review and comments. However, it does not outline specific strategies for

conservation and sustainability of biodiversity. Even though it is not outlined in the legislation, a list of

proposed plants for landscaping either from local nurseries or by importation is included in the EIAs.

Currently, Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is not undertaken in The Bahamas.

In Grand Bahama, the Port Authority formed an Environmental Department in March 2006 with the aim

of developing a capacity to introduce an environmental regulatory framework within the area

designated as the Port Area. Since the formation of the Department, EIA guidelines have been produced

for projects of various natures. In addition, guidelines for License applications relating to a myriad of

projects which may seek to start business in the Freeport area have also been developed. The License

Department has been given a checklist which would determine whether new projects would have an

environmental concern/component. If identified as requiring environmental review, a further

determination would be made as to whether a Basic Site Assessment, EIS, EIA or EMP is also needed

(Wilchcombe, 2010).

All the guidelines consider biodiversity and the impacts and mitigation on the same as a result of

whatever activity is being proposed

21

21. The Way Forward: Enhancing Cross-Sectoral Integration (Mainstreaming) of Biodiversity

in The Bahamas

The Bahamas has had numerous studies conducted, adopted policies and enacted legislation which

would contribute to the protection of biodiversity in the country. Despite using the various

mainstreaming mechanisms to develop these documents, the country struggles with making the findings

of the document a reality. Many local environmentalists feel that the environmental protection is

considered as an afterthought. Implementation is hampered by lack of technical skills, lack of man

power, lack of equipment and scarce financial resources. Even though these tools exist to assist in

decision making for development in the country they are more often than not referred to for guidance.

In order to enhance cross-sectoral integration in The Bahamas, the GOB has to make a commitment of

adequate financial resources to provide the needed technical skills, manpower and equipment to

successfully implement the strategic plans for the agriculture, fisheries, forestry and the tourism sectors.

In addition, all of the plans need to have a follow-up mechanism to evaluate the effectiveness of the

plans.

Further, to the five year plan for agriculture, the DOA should ensure that new leases issued on

agriculture land have clauses relating to conservation of biodiversity and the use of pesticides. The DOA

should promote management of agricultural lands with plant biodiversity in mind. Farmers should be

encouraged to set aside a portion of their agricultural land to be fallow for biodiversity conservation and

establish protocols for valuable plant conservation. The number of trained people working with

appropriate facilities in plant conservation should be increased, according to the national needs. The

country should also establish networks for plant conservation activities at the national, regional and

international levels.

In conjunction with the five year plan for marine resources, the DMR should conduct ecological

assessments and continuous monitoring of selected coral reefs and develop and implement restoration

and rehabilitation plans for designated degraded coral reef habitats. EIAs should be required for all

mariculture projects. DMR needs to develop an effective evaluation method for site selection of

mariculture projects along with the appropriate guidelines for effluent and waste control. Also, The

Bahamas should expand the number of inland water ecosystems (e.g. Big Pond) in the existing national

system of protected areas.

The Forestry Act, 2010 mandates that a five year management plan be developed for the forestry sector.

In order to enhance biodiversity conservation and sustainable use, the plan should include the

following:-

• Incorporation of the ecosystem approach in the management of the three types of forest areas

(forest reserves, protected forest and conservation forest);

• An assessment of based plant sources (e.g. silver tops, cascarilla, etc.) and creation of a

management plan for these species;

• Programmes to protect, recover and restore forest biological diversity;

22

• Plans to promote the sustainable use of forest biological diversity;

• Measures to improve the country’s understanding of the role of forest biodiversity and

ecosystem functions; and

• Mechanisms to promote access and benefit-sharing of forest genetic resources.

When the NBSAP is updated, and new sectoral plans are developed, many of the guidelines on

biodiversity and tourism development (developed by CBD) should be integrated.

Broadly, there is a need for the GOB to develop strategic plans to deal with environmental matters in

the Commonwealth.

Further enhancement of cross-sectoral integration in The Bahamas requires increasing knowledge and

awareness regarding biodiversity issues among the key decision makers in the various government

agencies, policy makers, stakeholders and the school populous. Policy makers need to be sensitized to

the issues facing biodiversity and should be educated on the economic worth of biodiversity in the

country. Through this insight it will be understood that protection of biodiversity does not hinder

economic development in the country, but helps to safeguard the environment and livelihoods for

future generations. Agencies need to be educated on their responsibilities for implementation of the

Convention on Biological Diversity and other biological diversity related conventions. This should assist

in broadening the mindset of the involved persons. Tourists and locals should be educated on some of

the regulations and conservation methods being used to protect biodiversity in the country, such as

looking at but not touching the marine turtles or that it is illegal to catch, transport or sell birds captured

in The Bahamas. Currently, NGO and private sector partners have on-going educational programmes on

biodiversity matters but are limited due to lack of funding.

Implementation is hampered by the lack of communication among and within agencies. There needs to

be a shift in thinking from territorialism to integrated thinking and that the sharing of knowledge does

not mean a loss of control. Due to the size and archipelagic nature of The Bahamas, enforcement is a

vast task. Dedicated resources such as man-power, equipment and money would assist in more

efficient implementation and enforcement. To truly make enforcement better, the entire country needs

to assist with enforcement. An environmental hotline should be established to direct concerns to the

relevant agencies, instead of the current situation where an individual reporting a concern must often

endure the frustration of calling several different agencies before locating the appropriate contact.