The Taxpayer Costs of

Divorce and Unwed Childbearing

First-Ever Estimates for the Nation

and All Fifty States

A Report to the Nation

Benjamin Scafidi, Principal Investigator

Institute for American Values

Institute for Marriage and Public Policy

Georgia Family Council

Families Northwest

On the cover: Man and Woman Splitting Dollar by

Todd Davidson, Stock Illustration RF, Getty

Images.

© 2008, Georgia Family Council and Institute for

American Values. No reproduction of the materi-

als contained herein is permitted without the

written permission of the Institute for American

Values.

ISBN: 1-931764-14-X

Institute for American Values

1841 Broadway, Suite 211

New York, New York 10023

Tel: (212) 246-3942

Fax: (212) 541-6665

Website: www.americanvalues.org

Email: [email protected]

M

OST OF THE PUBLIC DEBATE o

ver marriage focuses on the role of marriage as

a social, moral, or religious institution. But marriage is also an economic

institution, a powerful creator of human and social capital. Increases in

divorce and unwed childbearing have broad economic implications, including

larger expenditures for the federal and state governments. This is the first-ever

report that attempts to measure the taxpayer costs of family fragmentation for

U.S. taxpayers in all fifty states. Among its findings: Even programs that result in

very small decreases in divorce and unwed childbearing could yield big savings

for taxpayers.

The report’s principal investigator is Benjamin Scafidi, an economist in the

J. Whitney Bunting School of Business at Georgia College & State University. The

co-sponsoring organizations are the Institute for American Values, the Institute for

Marriage and Public Policy, Georgia Family Council, and Families Northwest.

The co-sponsoring organizations are grateful to Chuck Stetson and Mr. and Mrs.

John Fetz for their generous financial support of the project. The principal investi-

gator is grateful to Deanie Waddell for her expert research assistance.

Page 3

Project Advisors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4

Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .5

I. Why Should Government Care about Marriage? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

II. How Might Marriage Affect Taxpayers? Empirical Literature Review . . . . . . .9

How Much Does Marriage Reduce Poverty? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .10

Does Family Fragmentation Increase Crime? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .11

III. Is the Methodology Used in This Estimate Reasonable? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .12

What Costs Are Associated with Means-Tested Government Programs? . . .13

What Costs Are Associated with the Justice System? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

How Are Foregone Tax Revenues Estimated? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .16

IV. What Is the Total Estimated Cost of Family Fragmentation? . . . . . . . . . . . . .17

V. What Are the Policy Implications? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20

Appendix A: Testing the Analysis: Is the Estimate of $112 Billion

Too High or Too Low? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .22

Appendix B: Explaining the Methodology for State-Specific Costs . . . . . . . . . . .31

Tables

Table 1: U.S. Children Residing in Two-Parent Families . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Table 2: Percent of U.S. Children in a Single-Parent Household that Has... .7

Table 3: Persons and Children Lifted out of Poverty via Marriage . . . . . . .14

Table 4: Household Income and Usage of Food Stamps . . . . . . . . . . . . . .14

Table 5: Household Income and Usage of Cash Assistance . . . . . . . . . . . .15

Table 6: Household Income and Usage of Medicaid . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .15

Table 7: Estimated Costs of Family Fragmentation for U.S. Taxpayers . . . .18

Table A.1: Sub-Calculations of State and Federal Taxpayer Costs . . . . . . .32

Notes to Table A.1 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .33

Table A.2: Sub-Calculations for EITC and Justice System Estimates . . . . . .35

Table A.3: Total Poverty and Family Structure by State . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .36

Table A.4: Child Poverty and Family Structure by State . . . . . . . . . . . . . .37

Table A.5: Estimates of State and Local Taxpayer Costs of

Family Fragmentation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .38

Endnotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .39

Contents

The Taxpayer Costs of

Divorce and Unwed Childbearing

First-Ever Estimates for the Nation and All Fifty States

Page 4

Project Advisors

Project advisors provided expert review but are not authors of the report. Affiliations

are listed for identification purposes only. Any errors or omissions in this report are

the responsibility of the principal investigator and not of the project advisors.

James Alm

Andrew Young School of Policy Studies at Georgia State University

Obie Clayton

Morehouse College

Ron Haskins

The Brookings Institution

Brett Katzman

Kennesaw State University

Robert Lerman

Urban Institute

Theodora Ooms

Center for Law and Social Policy

Roger Tutterow

Mercer University

Matt Weidinger

U.S. House Ways and Means Committee

W. Bradford Wilcox

University of Virginia

About Benjamin Scafidi

Ben Scafidi is an associate professor in the J. Whitney Bunting School of Business

at Georgia College & State University. His research has focused on education and

urban policy. Previously he served as the Education Policy Advisor for Georgia

Governor Sonny Perdue and served on the staff of both of Georgia Governor Roy

Barnes’ Education Reform Study Commissions. He received his Ph.D. in Economics

from the University of Virginia and his bachelor’s degree in Economics from the

University of Notre Dame. Ben was born and raised in Richmond, Virginia. Ben and

Lori Scafidi and their four children reside in Milledgeville, Georgia.

Page 5

Executive Summary

T

HIS STUDY PROVIDES THE FIRST RIGOROUS ESTIMATE of the costs to U.S. taxpayers

of high rates of divorce and unmarried childbearing both at the national and

state levels.

Why should legislators and policymakers care about marriage? Public debate on

marriage in this country has focused on the “social costs” of family fragmentation

(that is, divorce and unwed childbearing), and research suggests that these are

indeed extensive. But marriage is more than a moral or social institution; it is also

an economic one, a generator of social and human capital, especially when it

comes to children.

Research on family structure suggests a variety of mechanisms, or processes,

through which marriage may reduce the need for costly social programs. In this

study, we adopt the simplifying and extremely cautious assumption that all of the

taxpayer costs of divorce and unmarried childbearing stem from the effects that

family fragmentation has on poverty, a causal mechanism that is well-accepted and

has been reasonably well-quantified in the literature.

Based on the methodology, we estimate that family fragmentation costs U.S. tax-

payers at least $112 billion each and every year, or more than $1 trillion each

decade. In appendix B, we also offer estimates for the costs of family fragmenta-

tion for each state.

These costs arise from increased taxpayer expenditures for antipoverty, criminal jus-

tice, and education programs, and through lower levels of taxes paid by individuals

who, as adults, earn less because of reduced opportunities as a result of having been

more likely to grow up in poverty.

The $112 billion figure represents a “lower-bound” or minimum estimate. Given the

cautious assumptions used throughout this analysis, we can be confident that cur-

rent high rates of family fragmentation cost taxpayers at least $112 billion per year.

The estimate of $112 billion per year is the total figure incurred at the federal, state,

and local levels. Of these taxpayer costs, $70.1 billion are at the federal level, $33.3

billion are at the state level, and $8.5 billion are at the local level. Taxpayers in

California incur the highest state and local costs at $4.8 billion, while taxpayers in

Wyoming have the lowest state and local costs at $61 million.

If, as research suggests is likely, marriage has additional benefits to children, adults,

and communities, and if those benefits are in areas other than increased income lev-

els, then the actual taxpayer costs of divorce and unwed childbearing are likely

much higher.

Page 6

How should policymakers, state legislators, and others respond to the large taxpayer

costs of family fragmentation? We note that even very small increases in stable mar-

riage rates as a result of government programs or community efforts to strengthen

marriage would result in very large savings for taxpayers. If the federal marriage

initiative, for example, succeeds in reducing family fragmentation by just 1 percent,

U.S. taxpayers will save an estimated $1.1 billion each and every year.

Because of the modest price tags associated with most federal and state marriage-

strengthening programs, and the large taxpayer costs associated with divorce and

unwed childbearing, even modest success rates would be cost-effective. Texas, for

example, recently appropriated $15 million over two years for marriage education

and other programs to increase stable marriage rates. If this program succeeds in

increasing stably married families by just three-tenths of 1 percent, it will be cost-

effective in its returns to Texas taxpayers.

This report is organized as follows: Section I explains why policymakers may have

an interest in supporting marriage. Sections II and III explain the methods used to

estimate the taxpayer cost of family fragmentation by using evidence about the rela-

tionship between family breakdown and poverty. Section IV reveals the national

estimate of the taxpayer cost. Estimated costs for individual states are found in

appendix B.

Finally, a note to social scientists: Few structural estimates exist of the relationships

needed to estimate the taxpayer costs of family fragmentation. Therefore, we have

used indirect estimates based on the assumption that marriage has no independent

effects on adults or children other than the effect of marriage on poverty.

Page 7

I. Why Should Government Care about Marriage?

O

VER THE LAST FORTY YEARS, marriage has become less common and more frag-

ile, and the proportion of children raised outside intact marriages has

increased dramatically. Between 1970 and 2005, the proportion of children

living with two married parents dropped from 85 percent to 68 percent, according

to Census data. About three-quarters of children living with a single parent live with

a single mother.

These important changes in family structure stem from two fundamental changes in

U.S. residents’ behavior regarding marriage: increases in unmarried childbearing

and high rates of divorce.

1

More than a third of all U.S. children are now born out-

side of wedlock, including 25 percent of non-Hispanic white babies, 46 percent of

Hispanic babies, and 69 percent of African American babies.

2

In 2004, almost 1.5

million babies were born to unmarried mothers.

3

Divorce rates, by contrast, after

increasing in the 1960s and 1970s, appear to have declined modestly in recent

years. The small decline in divorce after 1980, however, seems to have been offset

by increases in unwed childbearing, as the percentage of children living with one

parent increased steadily between 1970 and 1998 with only a small drop after 1998.

Overall, divorce rates remain high relative to the period before 1970. Today’s young

adults in their prime childbearing years are less likely to get married, and many

more U.S. children each year are

born to unmarried mothers. Should

U.S. taxpayers be concerned about

these increases in family fragmen-

tation, and if so, why?

Public debate on marriage in this

country has focused on the “social

costs” of increases in divorce and

unmarried childbearing. Research

suggests that the social costs are

indeed extensive. When parents

part, or fail to marry, their children

seem to suffer from increased risks

of poverty, mental illness, infant

mortality, physical illness, juvenile

delinquency and adult criminality,

sexual abuse and other forms of

family violence, economic hard-

ship, substance abuse, and educa-

tional failure, such as increased

risk of dropping out of school.

4

Table 1. U.S. Children Residing in Two-Parent Families

2005

85.2%

68.1%

68.3%

1970

1998

(Source:U.S.Bureau of the Census)

One Female Parent

21.5%

78.5%

One Male Parent

(Source:2005 American Community Survey)

Table 2. Percent of U.S.Children

in a Single-Parent Household that Has . . .

Page 8

But marriage is more than a moral or even social institution; it is also an economic

one, a generator of social and human capital, especially when it comes to children.

Not much attention has been focused to date on the hard, economic costs of family

fragmentation, by which we mean not only the economic costs to affected individ-

uals and families but also to the public purse.

There are good reasons for suspecting that taxpayer costs associated with family

fragmentation are substantial: To the extent that the decline of marriage increases

the number of children and adults eligible for and in need of government services,

costs to taxpayers will grow. To the extent that increases in family fragmentation

also independently drive social problems faced by communities—such as crime,

domestic violence, substance abuse, and teen pregnancy—the costs to taxpayers of

addressing these increasing social problems are also likely to be significant. Pointing

out these concerns is not to “blame the victim,” but rather to launch a serious effort

to determine what these costs are. If these costs are deemed substantial, then it is

worth thinking carefully about how these costs can be lowered so that resources

can be freed for other useful purposes.

In 2000, a group of more than one hundred family scholars and civic leaders noted

the range of public costs associated with family breakdown, concluding:

Divorce and unwed childbearing create substantial public costs, paid by tax-

payers. Higher rates of crime, drug abuse, education failure, chronic illness,

child abuse, domestic violence, and poverty among both adults and children

bring with them higher taxpayer costs in diverse forms: more welfare expen-

diture; increased remedial and special education expenses; higher day-care

subsidies; additional child-support collection costs; a range of increased direct

court administration costs incurred in regulating post-divorce or unwed fami-

lies; higher foster care and child protection services; increased Medicaid and

Medicare costs; increasingly expensive and harsh crime-control measures to

compensate for formerly private regulation of adolescent and young-adult

behaviors; and many other similar costs.

While no study has yet attempted precisely to measure these sweeping and

diverse taxpayer costs stemming from the decline of marriage, current research

suggests that these costs are likely to be quite extensive.

5

In response to public concerns about the negative consequences of divorce and

unmarried childbearing for child well-being, the federal government and many

states have modestly funded programs aimed at strengthening marriage.

Since the mid-1990s, at least nine states have publicly adopted a goal of strength-

ening marriage, and seven states have dedicated funding (often using a very small

Page 9

portion of their federal TANF, or welfare, funds) to various programs designed to

strengthen marriage.

6

For example, Oklahoma offers marriage skills classes throughout the state, provid-

ing the courses at no charge to low-income participants. In 2007, Texas legislators

mandated that a minimum of 1 percent of the federal TANF block grant to the state

be spent on marriage promotion activities, providing an estimated $15 million per

year for two years.

7

In addition to the TANF block grants, the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 provided an

additional $150 million annually for a Healthy Marriage and Responsible

Fatherhood Program, administered by the Administration for Children and Families

of the Department of Health and Human Services. These monies were specifically

allocated for programs designed to help couples form and sustain healthy marriage

relationships, with up to $50 million available for responsible fatherhood promo-

tion.

8

Overall, less than 1 percent of TANF dollars are spent annually on healthy

marriage programming.

Evaluation is under way to determine the effectiveness of these programs. In the

meantime, this study provides the first rigorous estimate of the costs to taxpayers of

the decline of marriage, both at the national level and the state level.

9

II. How Might Marriage Affect Taxpayers?

Empirical Literature Review

R

ESEARCH SUGGESTS THAT MANY of the social problems and disadvantages

addressed by federal and state government programs occur more frequently

among children born to and/or raised by single parents than among children

whose parents get and stay married.

10

The potential risks to children raised in

fragmented families that have been identified in the literature include poverty,

mental illness, physical illness, infant mortality, lower educational attainment

(including greater risk of dropping out of high school), juvenile delinquency, con-

duct disorders, adult criminality, and early unwed parenthood. In addition, family

fragmentation seems to have negative consequences for adults as well, including

lower labor supply, physical and mental illness, and a higher likelihood of commit-

ting or falling victim to crime.

11

To the extent that family fragmentation causes negative outcomes for children and

adults, it also leads to higher costs to taxpayers through higher spending on

antipoverty programs and throughout the justice and educational systems, as well

as losses to government coffers in foregone tax revenues.

Page 10

A crucial issue for this study is to ascertain to what extent the associations between

family fragmentation and these negative outcomes are causal. There are of course

powerful selection effects into marriage, divorce, and unwed childbearing, and

some portion of the negative outcomes for children in nonmarital families are

caused by habits, traits, circumstances, and disadvantages among adults that may

also lead to divorce and nonmarital childbearing.

12

For example, a dating couple facing an unexpected pregnancy may choose not to

marry because the man is unemployed. Depending on how one looks at it, the

out-of-wedlock birth may be said to result from the father’s low-earnings or the

mother and child’s poverty may be said to result from the out-of-wedlock birth.

Untangling “what causes what” is a challenge faced by many researchers who

study the family.

How Much Does Marriage Reduce Poverty?

Researchers respond to this challenge by using a variety of methods to control for

unobserved selection effects (that is, to account for other factors that could be

explaining the finding) and to tease out causal relationships (that is, to untangle

“what causes what”). In this case, the idea that family fragmentation contributes to

child poverty has been studied extensively and is widely accepted.

13

Marriage can

help to reduce poverty because there are two potential wage earners in the home,

because of economies of scale in the household, and possibly also because of

changes in habits, values, and mores that may occur when two people marry.

14

In addition, there is recent, intriguing research that uses naturally occurring evi-

dence to examine whether family fragmentation causes poverty. Elizabeth Ananat

and Guy Michaels, for example, use an unusual predictor of whether a married

couple will stay married (the predictor is whether their firstborn child is a male,

since research has shown that divorce is less likely when this is the case). With this

predictor they are able to study married couples who do and do not divorce and

conclude that “divorce significantly increases the odds that a woman with children

is poor.”

15

Their analysis suggests that almost all of the increase in poverty

observed among divorced mothers is caused by the divorce. Less than 1 percent

of these women and children live in poverty if their first marriage is intact, while

more than 24 percent of divorced women with children are living in poverty.

16

Another area of research uses national data to simulate changes in family structure.

For example, Robert Lerman used the Current Population Survey (CPS) and simu-

lated “plausible” marriages by matching single mothers to single males who were

the same race and were similar in age and education levels. He found that if these

theoretical marriages occurred they would reduce poverty by 80 percent among

these single-mother households.

17

Adam Thomas and Isabel Sawhill used a similar

Page 11

approach and concluded that marriage would reduce poverty among single moth-

ers substantially, by about 65 percent.

18

Both Lerman’s and Thomas and Sawhill’s estimates assume that getting married has

no effect on men’s labor supply (and therefore male earnings). Most research on

this topic, by contrast, finds that marriage leads to a modest increase in male labor

supply, which would further reduce poverty rates. David Ribar did a useful survey

of the literature on the impact of marriage on men’s earnings.

19

Other research that seeks to analyze the impact of marriage on poverty consists of

studies that conduct a “shift-share analysis,” which show what poverty rates would

be if the proportion of households in different family structures remained constant

over a given time period. Examples of this research include work done by Hilary

Hoynes, Marianne Page, and Ann Stevens and by Rebecca Blank and David Card.

These studies find that over 80 percent of poverty is related to changes in family

structure, such as increases in households headed by single mothers.

20

One cautionary note, however, is that these studies could overstate the impact of

family structure on income because they do not account for the likelihood that, as

Thomas and Sawhill say, “single-parent families possess characteristics that dispro-

portionately predispose them to poverty.”

21

For example, persons struggling with

mental illness, substance abuse, or criminal records might find it difficult both to

hold a job and to get or stay married. Nevertheless, even studies that attempt to

control for these factors strongly suggest that family fragmentation negatively affects

the income available to single parents and their children.

Does Family Fragmentation Increase Crime?

In addition to poverty, family fragmentation also appears to have large effects on

rates of crime, according to three separate bodies of literature.

For example, research that considers entire communities has found a strong associ-

ation between the percent of single-parent households and crime rates. In one case,

Robert O’Brien and Jean Stockard found that increases in the proportion of adoles-

cents born outside of marriage were linked to significant increases in homicide

arrest rates for fifteen to nineteen year olds.

22

A second large body of literature—investigations of individual families using vari-

ables, such as parent-child relationships or mothers’ education levels—finds that a

child raised outside of an intact marriage is more likely to commit crimes as a teen

and young adult. In one study Cynthia Harper and Sara McLanahan control for a

large number of demographic and other characteristics and find that boys reared in

single-mother households and cohabitating (or “living together”) households are

Page 12

typically more than twice as likely to commit a crime that leads to incarceration,

when compared to children who grow up with both their parents.

23

Finally, a body of literature that analyzes future crime rates of juvenile offenders

shows that stable marriages reduce the likelihood that adult males will commit addi-

tional crimes. With a unique data set of former juvenile offenders spanning several

decades, Robert Sampson and his colleagues find evidence that marriage leads

these former juvenile offenders to commit fewer crimes as adults, even when con-

trolling for unobserved selection effects.

24

Overall, research on family structure suggests a variety of ways marriage might

reduce the demand for costly public services. A stable marriage might reduce the

likelihood of domestic violence, alcohol abuse, and parental depression, and might

increase the human and social capital available to children in the home in ways that

(independent of income) improve children’s educational and other outcomes. Two

parents in the home might provide more effective supervision of adolescents,

reducing the risk of delinquent activities. At the same time, divorce may be some-

times desirable. For example, about one-third of marriages ending in divorce are

“high conflict” marriages, and children, on average, appear to be better off when

those marriages end.

25

In this analysis, however, we adopt the simplifying and extremely cautious

assumption that all of the taxpayer costs of divorce and unmarried childbearing

stem solely from the negative effects family fragmentation has on poverty in female-

headed households. We make this simplifying assumption because the effect of

marriage on poverty has been established, is widely accepted, and can be reason-

ably well-quantified based on existing data.

III. Is the Methodology Used in This Estimate Reasonable?

T

HIS STUDY USES SEVERAL CALCULATIONS to estimate the taxpayer costs of family

fragmentation. These estimates include calculations of foregone tax revenue

in income taxes, FICA (Social Security and Medicare) taxes, and state and

local taxes as a result of family fragmentation. They also include the direct costs to

taxpayers as a result of increased expenditures on local, state, and federal taxpayer-

financed programs in the following areas:

• Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance

• Food Stamps

• Housing Assistance

• Medicaid

• State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP)

• Child Welfare programs

Page 13

• Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) assistance

• Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP)

• Head Start

• School Lunch and Breakfast Programs

• The Justice System

26

As noted previously, we assume taxpayer costs are driven exclusively by increases

in poverty; that is, we used the most widely accepted and best quantified conse-

quence of divorce and unmarried childbearing. It is important to recognize that if

family fragmentation has additional negative effects on child and adult well-being

that operate independently of income—and if these effects increase the numbers of

children or adults who need and are served by taxpayer-funded social programs—

then our methodology will significantly underestimate taxpayer costs. For example,

if family fragmentation increases the number of children who suffer from chronic

illnesses,

27

these additional costs to taxpayers would not be reflected in the esti-

mates provided by this study.

To put it another way, the methodology we use assumes that marriage would not

improve the habits, mores, or other behaviors of adults or children in ways that lead

to reduced social problems or increased productivity.

What Costs Are Associated with Means-Tested Government Programs?

To obtain an estimate of the taxpayer costs of family fragmentation, this study uses

the literature and information already described to make three key assumptions:

• Assumption 1: Marriage lifts zero households headed by a single male out

of poverty.

• Assumption 2: Marriage lifts 60 percent of households headed by a single

female out of poverty.

• Assumption 3: The share of expenditures on government antipoverty

programs that is due to family fragmentation is equal to the percent of

poverty that results from family fragmentation.

28

Taken as a group, these assumptions err on the side of caution. They are more likely

to lead to an underestimate of the actual taxpayer costs of family fragmentation

rather than an overestimate. Assumption 1 leads us to understate taxpayer costs

because marriage might bring a second wage earner into single-father households

and/or allow men to focus more effort on labor market activities that would

increase household earnings. Assumption 2 is based on the discussion on pages

10–11 of this report, specifically the empirical results provided by Ananat and

Michaels and Thomas and Sawhill.

29

Page 14

Assumption 3 implies that the proportion of poverty that can be attributed to fam-

ily fragmentation is equal to the proportion of expenditures on a variety of govern-

ment programs that are caused by family fragmentation. As shown in table 3, if mar-

riage would lift 60 percent of single-mother households out of poverty, then the

total number of persons in poverty would decline by 31.7 percent and the total

number of children in poverty would decline by 36.1 percent.

30

By virtue of

assumption 3, marriage would reduce the costs of some government programs by

31.7 percent and the costs of government programs that are exclusively for children

by 36.1 percent. Put another way, this assumption suggests that family fragmenta-

tion is responsible for 31.7 percent of the costs of government antipoverty programs

and is responsible for 36.1 percent of the costs of government programs that are

exclusively for children.

31

This crucial assumption seems cautious not only because single-parent households

have higher rates of poverty and other negative outcomes but also because at the

same income level single-parent households are much more likely than married

households to make use of government benefits.

In the cautious assumptions used in this analysis, we assume no behavioral effects

from marriage on the likelihood of choosing to use government programs, even

though (as shown in tables 4, 5, and 6) single-mother households use the Food

Stamp, cash assistance, and Medicaid programs at much higher rates than married

households with similar incomes.

Percent Receiving

Percent Receiving Food Stamps

Food Stamps Families Earning < 200%

Family Type All Income Levels of Poverty Level

Married 3.9% 16.2%

Male head no spouse present 8.6% 21.2%

Female head no spouse present 26.1% 42.5%

(Source: 2006 CPS)

Table 4.Household Income and Usage of Food Stamps

Number Lifted Out of

Poverty via Marriage

(thousands)

Total U.S.

@60% of female-headed

Poverty 2006

households in poverty Percent Lifted Out of

(thousands)

are lifted out of poverty Poverty via Marriage

Total Persons 36,460 11,554 31.7%

Children 12,827 4,629 36.1%

(Source:2006 CPS)

Table 3.Persons and Children Lifted out of Poverty via Marriage

Page 15

Assumption 1 means that our analysis focuses on female-headed households only;

that is, taxpayer costs associated with single-father households are excluded.

Assumptions 2 and 3 allow us to make cautious and straightforward estimates of

increased government expenditures on TANF, Food Stamps, housing assistance,

Medicaid, SCHIP, child welfare programs, WIC, LIHEAP, Head Start, and school

breakfast and lunch programs that result from family fragmentation. (See more

details in “Notes to Table A.1” on page 33.) For government programs that serve

both adults and children (TANF, Food Stamps, housing assistance, Medicaid, WIC,

and LIHEAP), we assume that 31.7 percent of these costs are due to family fragmen-

tation. We make this assumption because existing data (as shown in table 3) sug-

gests that family fragmentation is responsible for 31.7 percent of overall poverty,

and assumption 3 suggests that family fragmentation is responsible for 31.7 percent

of taxpayer costs on these programs.

For government programs that serve only or predominantly children (such as SCHIP,

child welfare programs, Head Start, and school breakfast and lunch programs), we

assume that 36.1 percent of these costs are due to family fragmentation.

32

We offer one cautionary note: The taxpayer costs associated with family fragmen-

tation may be real, but this link does not mean that taxpayers would necessarily

choose to realize all the tax savings from reductions in family fragmentation.

Percent Receiving

Percent Receiving Medicaid

Medicaid Families Earning < 200%

Family Type All Income Levels of Poverty Level

Married 15.4% 40.3%

Male head no spouse present 27.9% 43.9%

Female head no spouse present 45.6% 62.7%

(Source: 2006 CPS)

Table 6.Household Income and Usage of Medicaid

Percent Receiving

Percent Receiving Cash Assistance

Cash Assistance Families Earning < 200%

Family Type All Income Levels of Poverty Level

Married 3.6% 8.5%

Male head no spouse present 7.8% 13.2%

Female head no spouse present 17.2% 24.8%

(Source: 2006 CPS)

Table 5. Household Income and Usage of Cash Assistance

Many transfer programs, such as Head Start, Section 8 housing vouchers, and

LIHEAP are not entitlements. That means not all individuals or households poten-

tially eligible to receive funding or services under these programs receive them.

For non-entitlement programs, savings realized from increases in marriage and

marital stability could be reaped by taxpayers or the savings might be passed on

to other poor people.

33

But if such savings were to occur, legislators and voters

could either choose to change the rules and use the money for other government

purposes or return it to taxpayers.

The next steps in our study were finding ways to estimate any increased costs to

the justice system caused by family fragmentation and any foregone tax payments

that would result from eliminating family fragmentation. These two sets of calcula-

tions require some discussion.

What Costs Are Associated with the Justice System?

Evidence suggests that boys raised in single-parent households are likely to commit

crimes at much higher rates than boys raised in married households.

34

Further, mar-

riage reduces the likelihood that adult men will commit crimes.

35

For the purposes of calculating the impact of family fragmentation on increased

costs to the justice system, however, we use the following cautious and simplifying

assumption: All of the effects of family fragmentation on crime operate through their

impact on childhood poverty rates. In this analysis, we are following Harry Holzer

and his colleagues. They created a methodology to estimate the impact of eradicat-

ing childhood poverty on costs to the U.S. economy. One cost they consider is the

cost to the justice system—which includes courts, police, prisons, and jails.

Essentially, based on several assumptions taken from the empirical literature on

crime, they report that 24 percent of crime is caused by childhood poverty.

36

Using

this result, we estimate that if marriage were to reduce childhood poverty rates by

36.1 percent, then costs for the justice system would be reduced by approximately

$19 billion. (See details of this calculation in table A.1.)

How Are Foregone Tax Revenues Estimated?

To estimate the impact of family fragmentation on foregone tax revenues, we must

estimate the increase in taxable income that would result from marriage. We again

make the simplifying assumption that marriage has no behavioral effect; in other

words, marriage would not increase the labor supply of men and would therefore

have no impact on the taxable earnings of single parents who marry. Again, given

the rich literature on how marriage impacts male labor supply,

37

this is a cautious

assumption, which increases our confidence that our analysis does not overestimate

the actual taxpayer costs of the decline of marriage.

Page 16

Similarly, we assume that all of the effects of family fragmentation on children’s

future earnings capacity operate only through their impact on rates of childhood

poverty. Given the rich but difficult-to-quantify body of evidence that married par-

ents contribute to increasing the human and social capital of their children in other

ways (in addition to income),

38

this decision represents another simplifying but cau-

tious assumption, which increases our confidence that our results will not overesti-

mate the taxpayer costs.

There is good evidence on the impact of childhood poverty on future productivity.

Holzer and his colleagues estimate that childhood poverty reduces income nation-

ally by $170 billion per year. That is, they find that if children in poverty had instead

grown up in households that were not in poverty, then these children would as

adults earn $170 billion more each year.

39

Using Holzer’s estimate of total costs of

childhood poverty on adult annual earnings and the estimate that marriage would

reduce childhood poverty by 36.1 percent, we estimate that marriage would

increase taxable earnings by over $61 billion per year.

To translate this data into an estimate of tax losses from losses in future productiv-

ity, we must make simplifying assumptions about tax rates. For this analysis, we

assume that all of the increase in earnings is taxed at the 10 percent rate for U.S.

income taxes and that all of this increase in earnings is taxed at 15.3 percent for

FICA (as tax economists generally find that employees bear the burden of FICA tax-

ation through lower wages). To estimate losses in state and local taxation, we use

the national average percentage of income that is paid in state and local taxes—11

percent—as reported by the Tax Foundation on April 4, 2007.

40

(The details of this

calculation are shown in table A.1.)

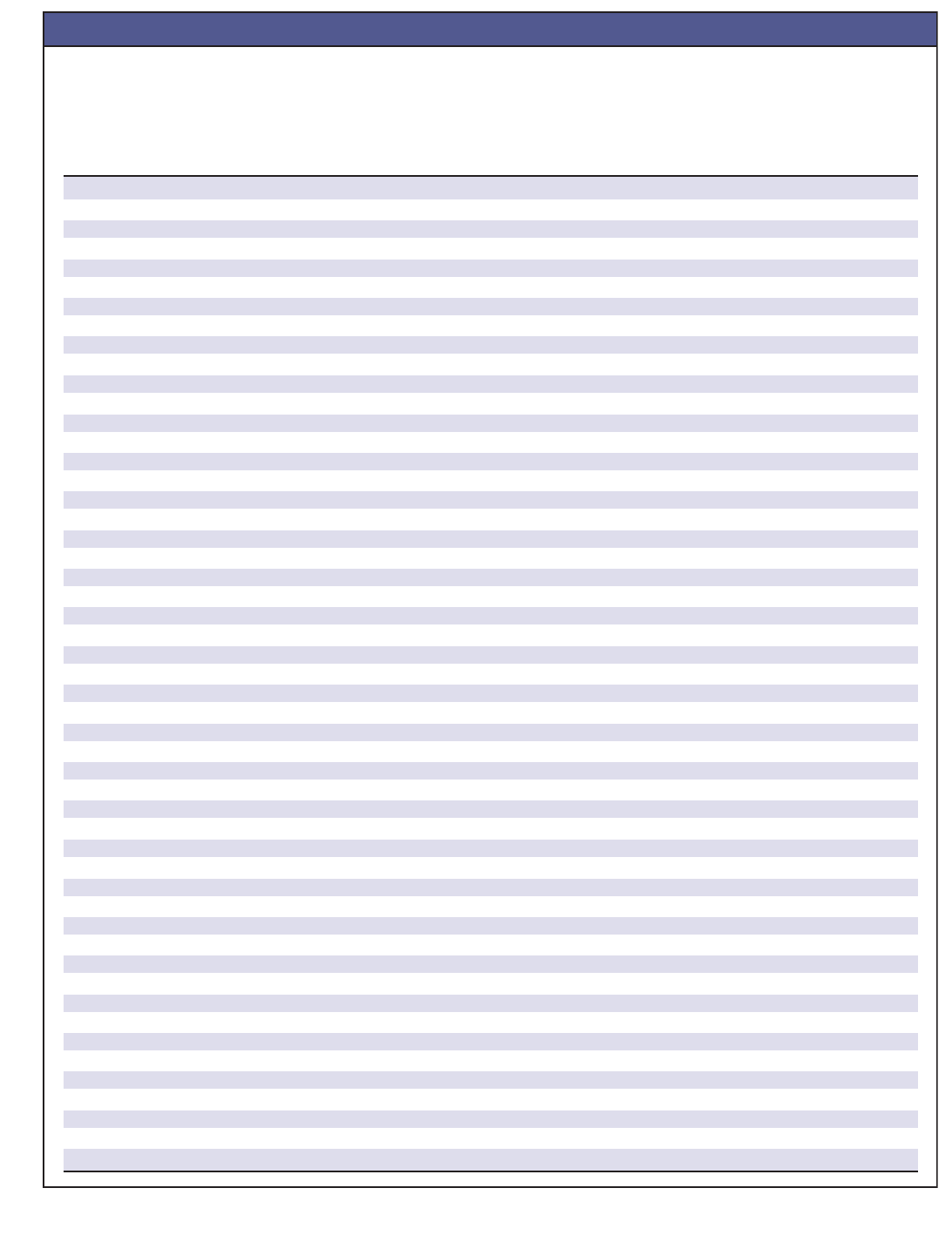

IV. What Is the Total Estimated Cost of Family

Fragmentation?

H

OW MUCH DO HIGH RATES of divorce and unmarried childbearing cost U.S. tax-

payers? Here is our estimate:

Family fragmentation costs U.S. taxpayers at least $112 billion each year, or

over $1 trillion dollars per decade.

41

This $112 billion annual estimate includes the costs of federal, state, and local gov-

ernment programs and foregone tax revenues at all levels of government. Table 7

shows an itemized estimate.

To find the cost of family fragmentation in your state, turn to page 38.

Page 17

Table A.5 (page 38) reveals state-by-state estimates for the costs of family fragmen-

tation, and appendix B (page 31) describes the methods used to estimate the costs

of family fragmentation for state and local taxpayers. These state-by-state estimates

are a subset of the $112 billion total taxpayer cost.

We are confident this is a minimum figure because of the uniformly cautious

assumptions built into our methodology. For those who would like to dig deeper,

appendix A (page 22) provides a detailed response to possible arguments that we

have overestimated or underestimated taxpayer costs. For example, here are four

potential underestimates:

First, our estimate focuses exclusively on female-headed households; that is, we

assume the taxpayer costs of single-father families are zero. This assumption almost

certainly leads to an underestimate.

Second, we have excluded from analysis several expensive government programs

(because existing data does not allow us to quantify them with confidence), which

nonetheless very likely include significant marriage-related taxpayer costs. The tax-

payer-funded programs excluded from analysis include the Earned Income Tax

Credit (EITC), public education,

42

and Medicare and Medicaid benefits for older

adults. The EITC alone is a $40 billion taxpayer-funded program. Estimating the

effect of marriage on the EITC involves making complex judgments about who mar-

ries whom, and how their income shifts as a result. Since we lack hard data to make

Page 18

inbillions

Justice System $19.3

TANF – Cash Assistance $5.1

Food Stamps $9.6

Housing Assistance $7.3

Medicaid $27.9

SCHIP $2.8

Child Welfare $9.2

WIC $1.6

LIHEAP $0.7

Head Start $2.7

School Lunch and Breakfast Program $3.5

Additional U.S. IncomeTaxes Paid $6.1

Additional FICA Taxes Paid $9.4

Additional State & Local Taxes Paid $6.8

Total U.S.Taxpayer Cost of Family Fragmentation $112.0

* These costs include federal,state,and local costs.

Table 7.Estimated Costs of Family Fragmentation for U.S. Taxpayers*

these judgments with the precision necessary to quantify them, we left this program

out of the analysis. While some fraction of currently cohabiting taxpayers might pay

a marriage penalty if they were to marry, the overall poverty-reducing effects of

marriage are likely to move many more families off the EITC rolls. (See appendix

A for more detail.)

Similarly, some fraction of public school budgets is likely spent in dealing with social

problems created by divorce and unmarried childbearing. Children whose parents

stay married are less likely to repeat a grade, exhibit conduct disorders requiring

special education outlays, or require expensive special education services generally.

Again, none of these costs are reflected in our analysis.

We have also excluded one of the largest taxpayer costs on the book: Medicaid for

the elderly and Medicare for unmarried adults. They are excluded partly because

most people do not think of older single adults when they think of “fragmented

families.” But high rates of divorce and failure to marry mean that many more

Americans enter late middle-age (and beyond) without a spouse to help them man-

age chronic illnesses, or to help care for them if they become disabled.

43

Through

the Medicare and Medicaid system taxpayers are picking up a large, but difficult to

quantify, part of the costs as a result.

Third, we have ignored for the purposes of this analysis any behavioral effects of

marriage. We have assumed that all the benefits of marriage come solely from

reduced rates of poverty for children, ignoring the evidence that stably married par-

ents provide human and social capital to their children other than income in ways

that increase children’s well-being and reduce the likelihood they will need or incur

expensive government services, from repeating grades at school to ending up in the

child protective system or the juvenile justice system.

Similarly, we have assumed no behavioral effects of marriage on fathers’ earning

capacity. If stable marriage increases men’s earnings, as the literature suggests, and/or

decreases the likelihood that they will commit crimes as adults, our methodology

most likely underestimates the taxpayer costs associated with unmarried parenthood.

Fourth, there is one other major reason we believe $112 billion each year repre-

sents a cautious, minimum estimate: For the purposes of this analysis, we assume

that households that marry will “take up” or use government benefits for which they

are eligible at the same rate as single-mother households. In reality, existing data

shows that lower-income married couples are far less likely to choose to use gov-

ernment benefits for which they are eligible than single-mother households.

Overall, single mothers are roughly twice as likely to take advantage of government

benefits for which they are eligible than are low-income married couples.

44

Page 19

Many more details, including a discussion of the empirical literature on which our

conclusions are based, are found in appendix A.

V. What Are the Policy Implications?

H

OW SHOULD POLICYMAKERS, state legislators, and others respond to these new,

rigorous estimates of the large taxpayer costs of family fragmentation?

First, public concern about the decline of marriage need not be based only on the

important negative consequences for child well-being or on moral concerns, as impor-

tant as these concerns may be. High rates of family fragmentation impose extraordi-

nary costs on taxpayers. Reducing these costs is a legitimate concern of government,

policymakers, and legislators, as well as civic leaders and faith communities.

Second, even very small increases in stable marriage rates would result in very large

returns to taxpayers. For example, a mere 1 percent reduction in rates of family

fragmentation would save taxpayers $1.12 billion annually.

Given the modest cost of government and civic marriage-strengthening programs,

even more modest success rates in strengthening marriages would be cost-effective.

Texas, for example, recently appropriated $15 million over two years for marriage

education and other programs to increase stable marriage rates. If such a program

succeeded in increasing stably married families by just three-tenths of 1 percent, it

would still save Texas taxpayers almost $9 million per year. Efforts are currently

underway to evaluate the impact of these programs.

Conclusion

E

ACH YEAR, FAMILY FRAGMENTATION costs American taxpayers at least $112 billion

dollars. These costs are recurring—that is, they are incurred each and every

year—meaning that the decline of marriage costs American taxpayers more

than $1 trillion dollars over a decade.

These costs are due to increased taxpayer expenditures for antipoverty, criminal jus-

tice and school nutrition programs, and through lower levels of taxes paid by indi-

viduals whose adult productivity has been negatively influenced by growing up in

poverty caused by family fragmentation.

This figure represents a minimum or “lower-bound” estimate. If, as research sug-

gests is likely, marriage has additional economic and social benefits to children,

adults, and communities—benefits that reduce the need for government services

and that operate through mechanisms other than increased income—then the actu-

al taxpayer costs of the retreat from marriage are likely much higher.

Page 20

Given the cautious assumptions used throughout this analysis, we can be confident

that current high rates of family fragmentation cost taxpayers at least $112 billion a

year, or more than $1 trillion over a decade. Finding new ways to strengthen mar-

riage and reduce unnecessary divorce and unmarried childbearing is a legitimate

and pressing public concern.

Because of the very large taxpayer costs associated with high rates of divorce and

unmarried childbearing, and the modest price tags associated with most marriage-

strengthening initiatives, state and federal marriage-strengthening programs with

even very modest success rates will be cost-effective for taxpayers.

Page 21

Appendix A: Testing the Analysis:

Is the Estimate of $112 Billion Too High or Too Low?

In this appendix, we consider in detail four arguments that suggest the estimate that

the total taxpayer cost of family fragmentation of $112 billion is too high and four

arguments that it is too low.

Is $112 Billion Too High?

In this section, we consider four arguments that suggest the $112 billion estimate is

too high:

1. If cohabitating households were to marry, most of them receiving transfer

payments would receive a marriage bonus from the federal tax and trans-

fer system.

2. The use of Holzer’s research in this study exaggerates the actual impact of

low income on childhood poverty.

3. The use of Thomas and Sawhill’s research in this study overestimates the

impact of marriage on reducing poverty.

4. The main assumption of this study—that the percentage of government

program costs due to family fragmentation is proportional to the amount

of poverty due to family fragmentation—overestimates the taxpayer costs.

1. If cohabitating couples were to marry, they would receive a marriage bonus from

the federal tax and transfer system.

The earned income tax credit (EITC) is an approximately $40 billion antipoverty

program that provides cash subsidies to low-income working adults, and Temporary

Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) is a $16 billion cash assistance program for

low-income families. Gregory Acs and Elaine Maag report that of the 1.1 million

people living in cohabitating households earning less than 200 percent of the

poverty level and receiving the EITC and/or TANF, about three-fourths of these

households would receive an average marriage bonus of approximately $2,423,

while about 10.5 percent of these households would receive a marriage penalty of

$1,742 in 2008. Thus, if the cohabitating adults in these households were to marry,

taxpayers would face increased expenditures for these two social programs. Taken

together, these estimates from Acs and Maag suggest that taxpayer expenditures for

the EITC, TANF, and the child tax credit would increase by about $0.5 billion if all

cohabitating couples were to marry.

45

Given the results in Acs and Maag, is our estimate of the taxpayer cost of family

fragmentation too high by $0.5 billion? In table 7, we ignore any costs of family frag-

mentation on the EITC. We do so because of complications such as the one pointed

out by Acs and Maag that some households would get higher EITC payments if they

became married households and nothing else about them (e.g., labor supply)

changed. Nevertheless, it appears likely that the net taxpayer costs of family

Page 22

fragmentation on the EITC would be positive because marriage would render mil-

lions of EITC recipients ineligible for any EITC benefits by adding a second wage

earner to the household and/or possible positive effects on male labor supply. If

marriage, as discussed in the next subsection, would decrease net expenditures on

the EITC, then the approach used in this study would underestimate the taxpayer

costs of family fragmentation by ignoring the EITC.

2. The use of Holzer’s results in this study overestimates the impact of low income

in childhood on adult outcomes.

We rely on results from Harry Holzer’s research to make two calculations—costs to

the justice system and increased tax payments. Holzer and his colleagues make a

case that the assumptions that underlie their estimates are cautious, and we find

their case persuasive. However, they make a broad interpretation of the relationship

between childhood poverty and life outcomes as follows:

[W]e interpret the causal effects of childhood poverty quite broadly. They

include not only the effects of low parental incomes, but also of the entire range

of environmental factors associated with poverty in the U.S., and all of the per-

sonal characteristics imparted by parents, schools, and neighborhoods to chil-

dren who grow up with or in them. We define “poverty” broadly in this way in

part because researchers have been unable to clearly separate low income from

other factors that affect the life chances of the poor, and also because the set

of potential policy levers that might reduce the disadvantages experienced by

poor children go beyond just increasing family incomes. Of course, in defining

poverty this way, we also assume that the entire range of negative influences

associated with low family incomes would ultimately be eliminated if all poor

children were instead raised in non-poor households.

46

(Holzer’s emphasis)

Childhood poverty may be a proxy for “environmental factors” that may or may

not be improved by the income gains from marriage. Thus, reliance on Holzer’s

estimates of the costs of childhood poverty could potentially overstate any bene-

fits of marriage that come from marriage reducing childhood poverty. One way to

think about this issue carefully is to list the broad pathways (i.e., “the environ-

mental factors”) through which growing up in poverty is associated with child-

hood disadvantage:

a. Low income may mean lower quality food, shelter, transportation, and

medical care for children.

b. Low income may necessitate living in worse neighborhoods (fewer parks,

more crime, less social trust), and poor neighborhood quality may

adversely affect child well-being.

c. Low income may mean attending worse schools.

d. Low income may negatively affect parenting processes (warmth, monitor-

ing, discipline) because of the stress economic hardship places on other-

wise competent parents.

Page 23

e. Conversely, parents may have low incomes because they are less

motivated and skilled and this lesser competence may be exhibited in

parenting as well.

f. Low income may hurt children because low-income families are more

likely to have only one parent present, and therefore only half the social

and human capital available to the child.

If absence of money itself is the root cause of the negative effects of childhood

poverty, then any strategy that increases income will increase child well-being.

With more money, parents can provide better nutrition, education, housing, and

medical care. They can move to better neighborhoods and enjoy better schools. It

may be the case, however, that not all the potential pathways through which child-

hood poverty negatively affects child well-being can be “treated” with more

money. More money may lower the income stress but not the emotional stress of

single parenting, for example. In addition, there may be less human and social cap-

ital that results when one parent—only half the potential talent pool for parent-

ing—is available.

If marriage increases household income, then marriage would ameliorate the neg-

ative effects of childhood poverty that operate through pathways labeled a, b, c,

and d above. Marriage may also address at least some of the other pathways

through which childhood poverty is associated with relative deprivation (f). But

marriage does not address all of the pathways: What if low-income parents are sim-

ply less competent generally in parenting as in other domains of life (e)? What if

they are less motivated to help their children succeed or have fewer of the skills

needed to help their children manage school or work?

To the extent that childhood poverty is caused by living with adults who have per-

sistent personality traits or skill deficits that lessen child well-being, neither income

supports nor increased marriage alone will “treat” these problems.

Holzer and his colleagues make an adjustment for genetic factors that may be pres-

ent in the ability to generate labor market earnings that they believe errs on the side

of caution. But not all the selection effects may be understood to be genetic in

nature. What if single moms or dads simply are people who have lower average

parenting skills and less motivation to begin with? If this is the case, then the use

of Holzer’s results for two calculations leads to an overestimate of the taxpayer cost

of family fragmentation.

Like Holzer, this analysis is constrained by the availability and quality of relevant

empirical evidence. We believe, however, that the way we use Holzer’s results does

not lead to an overestimate for at least three reasons:

• If the assumptions Holzer and his colleagues used are cautious, then that

offsets at least some of the “environmental” effects of having a mother or

father with less motivation, whether married or not.

Page 24

• Our analysis assumes no effect of marriage on the labor supply of parents.

The best evidence, as reported in Ribar’s extensive literature review in

2004, indicates that marriage increases male labor supply and seems not to

depress the average female labor supply in the more recent groups of

women studied.

47

• Our analysis assumes no behavioral effect of marriage on parenting skills. If

marriage reduces stress on parents, which leads to better parenting, then this

approach underestimates the true taxpayer costs of family fragmentation.

Given the limits of the available empirical evidence, we implicitly assume that these

three reasons exactly offset any of the effects of childhood poverty that are due to

unobserved lower motivation and/or skills present among single parents. To the

extent this assumption is wrong and it leads to overstating taxpayer costs because

of the use of Holzer’s research, the magnitude of the overestimate would have to

be viewed in light of the magnitude of our underestimates as described in the next

subsection. As suggested below, these underestimates are likely quite substantial.

3. The use of Thomas and Sawhill’s research overestimates the impact of marriage

on reducing poverty.

Thomas and Sawhill estimate that marriage would lift 65.4 percent of single-

mother households out of poverty.

48

In their microsimulation they place individu-

als in the March 1999 CPS in “plausible” marriages until they obtain a marriage rate

similar to 1970. Attempting to marry all single-mother households would likely fall

short because of a lack of marriageable men—prisoners are disproportionately men,

as are the unemployed, and men have lower life expectancies than women. The

dearth of marriageable men is one reason that we use a 60 percent figure instead

of the 65.4 percent estimate from Thomas and Sawhill. In addition, Thomas and

Sawhill assume no behavioral effects of marriage on male labor supply, which sug-

gests they underestimate the effect of marriage on poverty reduction. For these two

reasons, our use of Thomas and Sawhill’s research should not lead to an overesti-

mate of the taxpayer cost of family fragmentation.

4. The main assumption of this study—the percentage of the costs of government

programs due to family fragmentation is proportional to the percent of poverty

due to family fragmentation—overestimates the taxpayer costs.

To the contrary, the following thought experiment suggests that this assumption

likely leads to an underestimate of the taxpayer cost of family fragmentation.

Suppose there was an antipoverty program that cost taxpayers a total of $100 bil-

lion. Also suppose this program provided $5,000 per year to 10 million married

households and $5,000 per year to 10 million single-mother households. In addi-

tion, suppose that 20 million married households were eligible for the program but

only 10 million used it, while all 10 million single-mother households eligible for

the program used it.

Page 25

If each of the 10 million single-mother households in this thought experiment were

instead married households, consider two questions:

• How would the methodology used in this study estimate the taxpayer cost

of family fragmentation?

• What would be the “true” taxpayer cost of family fragmentation?

Using the methodology of this study, 6 million of the single-mother households (at

60 percent) using this program would no longer use it, which means the cost of

family fragmentation would be 6 million multiplied by $5,000, which equals $30 bil-

lion. Also, the analysis would assume that the remaining 4 million single-mother

households that are now married households would still use the program.

Would $30 billion likely be the “true” costs? We suspect not, because married

couples use benefits for which they are income-eligible at a much lower rate

than single-parent households: Only 50 percent of initially married households

eligible for the program use it. As shown in tables 4–6, single-mother house-

holds are far more likely at any given income level to choose to use govern-

ment benefits:

• Single-mother households with incomes less than 200 percent of the

poverty line are 2.6 times more likely to receive Food Stamps than married

households earning less than 200 percent of the poverty line.

• Single-mother households with incomes less than 200 percent of the

poverty line are 2.9 times more likely to receive cash assistance than mar-

ried households earning less than 200 percent of the poverty line.

• Single-mother households with incomes less than 200 percent of the

poverty line are 1.56 times more likely to receive Medicaid than married

households earning less than 200 percent of the poverty line.

If we assume that currently single mothers had instead married and that they

would use government benefits for which they are eligible at the same rate as

other married households (50 percent), then the “true” taxpayer costs of family

fragmentation would be $40 billion ($30 billion + 0.5 x 4 million x $5,000). Thus,

using the methodology of this study would understate the “true” costs by 33 per-

cent using the assumption that married households and single-mother households

receive the same average benefit ($5,000 per household in this example), and that

single-mother households take up the antipoverty program at a rate twice as large

as married households.

The main assumption of this study seems to be a reasonable simplifying assump-

tion, because of the much higher take-up rate of antipoverty programs of single-

parent households relative to similarly situated married households; this assumption

perhaps leads to an underestimate of the taxpayer cost of family fragmentation.

Page 26

To sum up, any differences in unobserved levels of average motivation between

single and married mothers complicate using much of the existing empirical litera-

ture to estimate the taxpayer cost of family fragmentation. The assumptions that

underlie this analysis, however, are extremely cautious in an attempt not to over-

state the taxpayer costs. Specifically, by assuming no beneficial behavioral effects

of marriage on adults or children, we are likely underestimating taxpayer costs.

Is $112 Billion Too Low?

In this section, we consider four arguments that suggest that the $112 billion esti-

mate is too low:

1. Ignoring the EITC, public education, and other government programs

underestimates the true taxpayer costs of family fragmentation.

2. Ignoring the direct impact of family fragmentation on crime (independent

of poverty) underestimates the taxpayer costs.

3. Ignoring any impact of marriage on single fathers understates the tax-

payer cost of family fragmentation.

4. Ignoring the fact that, given income-eligibility, single-mother households

are much more likely than married households to take up subsidies from

transfer programs underestimates the likely taxpayer costs of family frag-

mentation.

1. Ignoring the EITC, public education, and other government programs underesti-

mates the true taxpayer costs of family fragmentation.

We ignore EITC expenditures largely because of the lack of empirical information

needed to make reasonable assumptions about how marriage will affect usage of

the EITC and related programs in our complex tax code. But ignoring potential tax-

payer savings produced by marriage on EITC expenditures means ignoring a very

expensive government program that is almost certainly affected by marriage rates.

Taxpayers spend approximately $40 billion on cash assistance to the working poor

under the EITC. As shown in table A.2, using the assumptions in this study, family

fragmentation would lead to about $12.68 billion in higher taxpayer costs on the

EITC. Adjusting this estimate based on the results of Acs and Maag, as discussed

under the first argument in the previous subsection, would reduce that amount by

about $0.5 billion, leaving a net taxpayer cost of about $12.18 billion.

We have chosen to ignore the EITC expenditures (including potential savings of an

additional $12.18 billion each year) because the consequences of marriage for the

EITC are complex and would involve multiple assumptions of how marriage would

affect men’s and women’s earnings.

In addition to the EITC, this analysis does not assume any costs of family fragmen-

tation to the public school system, which is almost certainly not true. Considerable

research suggests that children raised outside of intact marriages are more likely to

Page 27

be held back a grade, to be in special education, and to qualify for remedial serv-

ices, although we do not have hard data on how much of these effects are due to

unobserved selection bias and how much are “caused” by lack of marriage.

If marriage were to reduce the percentage of children receiving special or remedial

services, then family fragmentation would create significant taxpayer costs for

public education, as federal and state funding formulas tend to provide large

amounts of extra funding for children receiving these services. (These costs may

be offset, however, by more teens dropping out of school as a result of family

fragmentation, which reduces the direct taxpayer costs of public education.

49

)

The lack of evidence of exogenous changes in family structure on the likelihood of

receiving special education or remedial services or staying in school, and the lack of

comparable cost data on remedial and special education services across states,

makes it impossible to estimate these costs with confidence. But the lack of data

does not mean that family fragmentation has no impact on educational expenditures.

Finally, we exclude the approximately 71 percent of Medicaid expenditures devoted

to the disabled and the elderly from the analysis, thereby making the cautious

assumption that family fragmentation has no impact on these expenditures. Most

people do not think of elderly unmarried adults or middle-aged disabled singles as

belonging to “fragmented families.” Nonetheless, there is considerable evidence that

older adults who are unmarried are more likely to become disabled, to manage

chronic diseases less successfully, and to need nursing home care as they age.

50

Excluding these large public costs thus likely significantly underestimates the

actual costs to taxpayers from the decline in marriage.

2. Ignoring the direct impact of family fragmentation on crime (independent of

poverty) underestimates the taxpayer costs.

Estimates of the potential impact of family structure on crime, even those that do

not control for selection bias, are large and arguably should not be ignored. As dis-

cussed in the section on methodology on page 12, it appears that family fragmen-

tation has large effects on crime, both in terms of increasing the likelihood that a

child raised outside of marriage will commit crimes

51

and the likelihood that adult

men will leave criminal activity after they are married.

52

While Harper and

McLanahan use a large number of control variables to help isolate the effect of fam-

ily structure on youth crime, they do not control for unobserved selection effects.

Nonetheless, their estimated effects of family structure on crime are extremely

large—typically children reared in single-mother households are more than twice as

likely to engage in criminal activities as children reared in a married household. For

example, they report that children living with a single mother are 2.168 times more

likely to be incarcerated than children living with both parents, all else being

equal.

53

Suppose we had assumed that over half their result was due to selection

bias—that the single mothers in their sample possessed such poor parenting skills

that even if they got married most of the estimated effect Harper and McLanahan

reported was due to selection bias. Specifically, suppose that children reared with

Page 28

a single mother are only 50 percent more likely to engage in criminal activity than

children raised with both parents, all else being equal. As shown in table A.2, using

this more aggressive approach yields an estimate that family fragmentation is

responsible for about $29 billion in costs to the justice system as opposed to the

$19.3 billion estimate used to generate the main result of this study.

The $29 billion estimated cost of family fragmentation to the justice system is

either too high or too low depending on the true magnitude of any exogenous

effects of marriage on criminal activity. The $19.3 billion figure represents about

8.7 percent of all costs to the justice system ($19.3 billion / $222.8 billion = 0.087),

while the $29 billion figure represents 13 percent of all costs to the justice system

($29 billion / $222.8 billion = 0.13).

To put these two estimates in context, note that, according to the Bureau of Justice

Statistics, in 2002 only 43.6 percent of inmates report that they lived with both par-

ents “most of the time” while growing up.

54

While the majority of inmates did not

live with both parents most of the time while growing up, the figure used to gen-

erate the main estimate of this study suggests that only 8.7 percent of the costs of

the justice system can be attributed to family fragmentation. As stated previously,

Sampson and his colleagues endeavor to control for selection effects and find that

former juvenile offenders commit fewer crimes as adults when married. Because

our estimates here ignore these potential taxpayer savings from marriage, our

method is more likely to underestimate than overestimate the taxpayer costs of fam-

ily fragmentation to the justice system.

3. Ignoring any impact of marriage on single fathers understates the taxpayer cost

of family fragmentation.

Research suggests that married men become more committed workers at least in part

as a result of marriage. Therefore, if single fathers were to marry, it is likely that their

labor supply would increase leading to increased tax payments. Further, tables 4–6

show that single-father households have higher take-up rates of antipoverty pro-

grams than married households with similar incomes.

Adding a second wage earner would render single-father households less likely to

receive government assistance via increased income and economies of scale.

Economies of scale via marriage—essentially “savings from size”—imply that by liv-

ing together, two adults are better able to share expenses and escape poverty. Ribar

provides an example of how marriage leads to economies of scale:

Consider the outcomes for a couple with a 9th–11th grade education and one

child in 2001. The median annual income for a woman with this level of edu-

cation was $10,330, while the median annual income for a similarly educated

man was $19,434. If the mother and child lived apart from the father, their

income would have been below the two-person poverty threshold of $12,207;

however, if the family lived together, their combined income would have

Page 29

exceeded the three-person threshold of $14,255. The mother and child would

have also met the gross income requirement for food stamps if they lived apart

from the father but would [sic] been ineligible if they lived with him. Even if

the mother had no income and the family just depended on the father’s

resources, they would have been above the poverty line and ineligible for food

stamps if they all lived together.

55

4. Ignoring the fact that, given income-eligibility, single-mother households are

much more likely than married households to take up subsidies from transfer

programs underestimates the taxpayer costs.

As shown in tables 4–6, single-mother households have higher take-up rates of gov-

ernment antipoverty programs than married households with similar incomes. Thus,

even if single-mother households that were instead married households were to

remain eligible for transfer programs, it appears they would be less likely to use

them. The methods used to estimate the taxpayer cost of family fragmentation at

$112 billion ignore this likelihood, and suggest this estimate is too low.

To sum up, this study is likely underestimating the taxpayer cost of family fragmen-

tation because (1) there likely would be net savings of EITC expenditures due to

any increase in marriage rates of non-cohabitating single parents and savings from

other programs not considered here; (2) the estimated costs to the justice system

are too low if there is a direct effect of marriage on reducing crime—which seems

likely given the research done to date; (3) there are taxpayer costs of single-father

households that are ignored here; and (4) the take-up rate of antipoverty programs

would likely decline if single-parent households were instead married households

that remained eligible for these programs.

Page 30

Appendix B:

Explaining the Methodology for State-Specific Costs

This appendix describes the methodology used to estimate state-specific tax-

payer costs of family fragmentation. These estimates include costs to state and

local taxpayers.

The methods used to create the state-specific estimates are similar to the methods

employed to create the national estimate described in the body of this report. For

the state-specific estimates, we used the 2006 Current Population Survey to estimate

the state-specific reductions in total poverty and child poverty that would result

from marriage. These estimates are shown in the last columns of tables A.3 and A.4

and are based on assumptions 1–3 described on page 13. These tables include the

underlying data used as well as other information that reveal how total and child

poverty fall disproportionately on unmarried households, and on households

headed by single females in particular.

Table A.5 shows the components and the total state and local taxpayer costs of fam-