Citation: Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila (2024). Generation Z Linguistic Behavior in the UAE: A Threat to Emirati Arabic?.

Sch Int J Linguist Lit, 7(4): 120-144.

120

Scholars International Journal of Linguistics and Literature

Abbreviated Key Title: Sch Int J Linguist Lit

ISSN 2616-8677 (Print) |ISSN 2617-3468 (Online)

Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Journal homepage: https://saudijournals.com

Original Research Article

Generation Z Linguistic Behavior in the UAE: A Threat to Emirati

Arabic?

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila

1*

1

ESERP Business and Law School, 08010 Barcelona, Spain

DOI: 10.36348/sijll.2024.v07i04.004 | Received: 22.03.2024 | Accepted: 26.04.2024 | Published: 30.04.2024

*Corresponding author: Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila

ESERP Business and Law School, 08010 Barcelona, Spain

Abstract

This research analyzes the characteristics of Emirati Generation Z, millennials, and baby boomers, and the influence of

social media to explain linguistic changes in the UAE. To do so, we administered a questionnaire containing 100 English

words commonly used in Emirati Arabic; We have classified the types of English words and expressions used by the three

generation cohorts. Participants also responded to a qualitative questionnaire, concerning the role that English played

during the pandemic, Emiratis’ behavior towards social media, and their viewpoint regarding the influence of English in

Emirati Arabic. Results showed that Generation Z uses more English words and expressions than the other two generations.

Generation Z attended bilingual education in English and Arabic since primary school whereas most millennials and all

baby boomers attended school exclusively in Arabic. We have examined that social media contributed to more English

words in Emirati Arabic and determined the reasons why Generation G prefers to use English on social media and in their

daily lives. We could conclude that Generation Z and most millennials see English positively and as inevitable progress in

a globalized world while baby boomers see it as a threat to their language and culture. Generation Z also outperformed the

other two generations regarding the pronunciation of words in English when speaking Emirati Arabic.

Keywords: Emirati Arabic, Gulf Arabic, Gen Z, millennials, baby boomers, English, social media, code-mixing, code-

switching, multilingualism, linguistic diversity.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s): This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License (CC BY-NC 4.0) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium for non-commercial use provided the original

author and source are credited.

1. INTRODUCTION

People throughout the world are affected by

technology’s quick development, particularly those who

belong to generation Z (from now on Gen Z), born

between 1997 and 2013 (Dolot, 2018). Gen Z was born

in the digital era and it is impossible for them to function

without modern technologies (Ivanova and Smrikarov,

2009; Tarihoran and Sumirat, 2022). Since Gen Z is the

first genuinely digital generation to have grown up with

technology and cell phones, they like social media for

communication and other purposes. According to

Morning Consult's survey (Briggs, 2022), YouTube is

the most-used platform for Gen Z — with 88% spending

their time on the app followed by Instagram (76%),

TikTok (68%,) and Snapchat (67%). They have access to

mobile gadgets, digital devices, and the internet, which

has a significant impact on them (Tarihoran and Sumirat,

2022). They like communicating through social media

rather than conventional ways of communication such as

SMS and phone calls (Murray and Waller, 2007;

Tarihoran and Sumirat, 2022). Furthermore, the

literature shows that English is the language that

dominates social media (Tarihoran and Sumirat, 2022).

Social media gives people access to a

globalized world, and connects Western and Arab

identities, particularly throughout adolescence and the

early years of adulthood. As a result, we want to

investigate if this transition poses a risk to linguistic

stability and how the self-definition of young people in

the UAE may be replicated via the use of communication

technology, particularly by engaging with the social

media ecosystem. To do this, we will analyze the

sociolinguistic behaviors of Gen Z, marked by

complexity and contradictions, and situated in a culture

that is basically characterized by a dynamic clash

between tradition and modernity. In addition, we will

also analyze two previous generations - millennials and

baby boomers- and compare the number of English

words they use in Emirati Arabic with Gen Z.

Regarding language use in the UAE, it is

important to note that except for court documents

(Dorsey, 2018), all other documents are available in

English (in most banks, hospitals, and universities) or

they may be solely in English as is the case with bank

documents for expats, who make up for 90% of the

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 121

population (Ribeiro Daquila, 2020, p.1; GMI, 2023). It is

essential to understand the distinctions between Modern

Standard Arabic (MSA) and Emirati Arabic to

completely understand this research. The dialectal

Arabic spoken in the UAE is known as Emirati Arabic.

The formal and official language used in the Arab World,

Modern Standard Arabic, is the language used in the

Arab world for formal speeches, publications, and news

broadcasts (Ribeiro Daquila, 2020, 2021, 2022).

However, to perform daily tasks like ordering food,

eating at restaurants, or buying clothes in shopping malls

in big cities like Dubai and Abu Dhabi, Emiratis are

forced to speak in English. (Ribeiro Daquila, 2020, p. 1).

Alenazi (2023, p.3) identified the same phenomenon in

Saudi Arabia. This study added to the list of situations in

which Saudi locals use English on social media

platforms, such as Snapchat and X. According to a

survey conducted by Al-Hussien and Belhiah (2016)

with Emirati Gen Z students aged 12 to 17, these

participants primarily speak their dialect at home with

their family and among their Emirati friends, but 98% of

them prefer to use English when using the internet.

Additionally, 85% would rather read in English than

Arabic. Although Emirati Arabic is the preferred

language at home, the literature reveals that there has

been an increase in English in Emirati residences

(O’Neill, 2017; Kennetz and Carroll, 2018, p. 175). Arab

native speakers rarely use MSA to communicate with

other natives. Instead, they use their dialects. Emirati

Arabic is full of English words and verbs; therefore, this

study will analyze the impact of English on Emirati

Arabic in the three aforementioned generations. Emirati

official policies favor English over other languages – like

Hindi, for instance, which is spoken by 28% of the

population in the UAE – since it is the lingua franca.

Government-funded schools have progressively

embraced a bilingual curriculum in order to give the

majority of Emiratis a similar educational experience to

wealthy Emiratis and migrant students, who attend

English-medium private schools (Kennetz and Carroll,

2018, p. 180). These funded and private schools in

primary and secondary school (K-12) in Dubai cater to

90% of all school students. This change to a bilingual

curriculum led Emirati students to bilingualism.

However, English proficiency was acquired at the

expense of Arabic (Ziad, 2019, p. 143).

In the UAE, in Formal contexts such as

educational institutes, code-mixing [

1

] between MSA

and English is prohibited (Cummins, 2007; Hopkyns et

al., 2021, Carroll and van den Hoven, 2017; Hopkyns et

al., 2021). These researchers say that such rules cause

young Emiratis to assume that 'double monolingualism'

(Al-Bataineh and Gallagher, 2018) is preferable to

1

Mixing two languages in a sentence. For the full

definition of code-mixing, see section 2.1.5.

2

Alramsa Institute was founded in Dubai by Ms. Hanan

Al-Fardan and Mr. Abdulla Alkaabi, more than 25

books have been published in the Emirati dialect, most

linguistic mixing in formal contexts. In addition to

speaking Emirati Arabic with family and friends,

according to Hopkyn et al., (2021) and Ribeiro Daquila

(2020, 2021, 2022), Gen Z in the United Arab Emirates

(UAE) is heavily influenced by the English language.

This study will analyze to what extent English words and

expressions are being used in Emirati Arabic. We

consider English and Emirati Arabic the most used

language for communication among Emiratis in the

everyday context, instead of MSA (Kennetz and Carroll,

2018; Ribeiro Daquila, 2020, 2021; Hopkyn et al.,

2021).

1.2. Motivation

Being a translator and editor of Emirati Arabic

books at Alramsa Institute [

2

], I have always encountered

so many English words in Emirati Arabic that I started to

do research on this phenomenon in 2018. Previous

research (Ribeiro Daquila, 2022, p. 328-331) revealed

that Gen Z has a predilection for using more English

words when speaking Emirati Arabic than older Emiratis.

The previous questionnaire included only 30 English

words used in Emirati Arabic (Ribeiro Daquila, 2022, p.

338) and participants suggested others that were

included in this study. Therefore, this study looks into

how English is being used in Emirati Arabic by three

different generations; we intend to broaden the academic

knowledge of the lexicon of English words used in

Emirati Arabic.

1.3. Research Question

Regarding Emirati Gen Z and the use of words

and expressions in English, the following research

questions were posed:

Regarding the 100-English-word questionnaire

(Appendix B):

1. Are there phonetical and/or grammar

differences in the incorporation of English

words and expressions in the three groups?

2. Is the influence of English greater in the present

Gen Z group aged 15-16, when compared to our

previous Gen Z aged 17-18 surveyed three

years ago?

3. How much English is used in Emirati Arabic by

Gen Z when compared with older Emiratis (60

and over)?

Regarding the qualitative questionnaire (Appendix C):

4. Does social media have an impact on the

increase in English words and expressions in

Emirati Gen Z speech?

5. Can English be considered a threat to the

endurance of Emirati Arabic?

of which are textbooks for expats and even for Emiratis

who want to dive into their own dialect. Alramsa is an

institute specialized in teaching Emirati Arabic. I have

been working as a translator, proofreader, and editor for

Alramsa since June 2018.

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 122

2. Characteristics of Each Generation Cohort

For decades, Pew Research Center has been

measuring public attitudes on key issues and

documenting differences in those attitudes across

demographic groups (Parker, 2022). Researchers divide

modern generations into 6 groups:

• The Silent Generation: Born 1928-1945

• Baby Boomers: Born 1946-1964

• Generation X: Born 1965-1980

• Millennials: Born 1981-1996

• Generation Z: Born 1997-2010

• Generation Alpha: Born 2010-2025

Image generated by fotor, (2023) [

3

]

Our study compares the use of English words in

Emirati Arabic among Gen Zeers, millennials, and baby

boomers. As Pew Research Center (Pekerti and Denni,

2017) reminds us, Stereotypes and oversimplification are

sometimes caused by generational designations. Just as

not all Southerners, Catholics, or Black Americans are

the same, not all millennials or baby boomers are either.

Shared identities and experiences should be

acknowledged since they may be inspiring when done

well, but uniqueness shouldn't be sacrificed in the

process. We decided to leave out Generation X to keep

the focus on the three generations researched in our

previous study (Ribeiro Daquila, 2022), and to have a

generation gap that allows us to compare two younger

generations (Gen Z and millennials) with an older one

(baby boomers).

2.1. Generation Cohorts

Inglehart initially presented the generational

cohort theory in 1977 to segment a population.

Accordingly, the lifespan of a generational cohort may

be 20–25 or even more years long, depending on the

average amount of time for a particular birth group in a

given country to go from conception to childbearing

(Strauss and Howe, 1991; Meredith and Schewe, 2004).

The early adult years (ages 17 to 24) of each generation

are often characterized by shared experiences and

socially significant events.

3

Fotor, 2023 https://www.fotor.com/images/create

2.1.2. Generation Z

Gen Z is defined as those who were born in the

1990s and reared in the 2000s through the most

significant changes of the century and who live in a

world with the web, internet, smartphones, laptops,

freely accessible networks, and digital media (Dangmei

and Amarendra, 2016; Ribeiro Daquila, 2023a). The

social web has been a part of Gen Z's upbringing, and the

digital world is important to their identity. Their

existence is more closely tied to technology and the

digital world than any prior generation since they were

born and nurtured in it. The most racially and

technologically diverse generation is Gen Z, according

to Dangmei and Amarendra (2016). Social networking is

a crucial aspect of Gen Z's existence, and they have a

casual, direct, and distinctive communication style. Gen

Zeers are considered digitally self-taught and they turn

to YouTube to learn something new (Ameen and Anand,

2020, p. 184). According to research (Schawbel, 2014;

Dangmei and Amarendra, 2016), Gen Z is less driven by

money than Millennials and is more entrepreneurial,

trustworthy, tolerant, and open-minded.

Four out of five of their favorite brands are

technology companies. They’re abandoning traditional

corporate jobs in favor of content creation, and they’ve

even devised a new vocabulary inspired by algorithmic

guidelines (Briggs, 2022).

The influence of English in the United Arab

Emirates (UAE) has been significant, particularly among

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 123

Gen Z (Ribeiro Daquila, 2022, p. 328-331). Arab

countries are diverse in terms of culture, language, and

demographics, so it’s important to recognize that

experiences may vary across different countries within

the Arab world. There are a lot of foreigners living and

working in the UAE, who come from many different

nations (Onley, 2009). These various communities

communicate in English as a common language.

Emiratis use their dialect except for the interaction with

other Emiratis or with other Arabs. We must keep in

mind that Emiratis and Arabs account for only 15% of

the population in the UAE (GMI, 2023). Since they were

raised in such a diverse setting, Emirati Gen Zeers have

naturally adopted English as a way of communication

(GMI, 2023; Ribeiro Daquila, 2021, p.5). As the

language of global business and commerce, English

proficiency is highly prized in the UAE employment

market. Gen Z prioritizes studying and using English

because they are aware of how important it is for job

growth and access to global possibilities (Ribeiro

Daquila, 2020, p. 3). The UAE is a popular tourist

destination and receives millions of visitors annually.

English is the business standard for tourism and

hospitality, enabling Gen Z to communicate effectively

with tourists and participate in the growing tourism

sector (Ameen and Anand, 2020 p.182).

2.1.3. Generation Z and COVID-19

Learning at home was more challenging for

kids who lacked motivation when COVID-19 divided

homes from one another and parents and guardians were

worried about their financial future (Daniel, 2020; Wan

Pa et al., 2021). Depending on their level, topic of study,

and program of study, the COVID-19 pandemic had a

substantial influence on students' lives in several ways.

In addition, many students discovered that they were

unable to finish their university coursework and tests on

time, and in many cases, they had been abruptly excluded

from their social group. In these situations, social media

was essential as a medium for communication and

information dissemination. People regularly turned to

the media in response to hardship and ordinary

annoyances (Wan Pa et al., 2021). Literature (Zhao and

Zhou, 2021; Wan Pa et al., 2021) found that people

tended to use social media for problem-focused

activities, such as looking up health-related information

and emotion-focused coping, when faced with COVID-

19 problems, such as expressing emotions for mood

management or joining online communities for social

support.

Despite the clear advantages of social media

during emergencies like COVID-19, more frequent

usage of the platform is likely to lead to social media

addiction (Kashif, et al., 2020; Zhao and Zhou, 2021),

which may be caused by the government's policy to stay

at home and the abundance of free time. Many people

became agitated and afraid if they did not use it during

the coronavirus lockdown. According to Wan Pa et al.,

(2021) whose study included 96 Gen Zeers, 57.6% of

respondents' academic performance was considerably

impacted by social media addiction. Our research

question 4 will analyze if there was an increase in the use

of English words in Emirati Arabic due to social media

in the UAE as well as if there was a rise in the use of

social media during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.1.4. Millennials (less commonly Gen Y)

People who were born between 1981 and 1996

are referred to as millennials, also known as Generation

Y or Gen Y, while the exact dates might vary by one or

two years depending on the source. William Strauss and

Neil Howe initially adopted it in their 1991 book

Generations because they thought it was a fitting

moniker for the first generation of adults born in the new

century. Between Generation X (Gen X; defined as those

born between 1965 and 1980) and Gen Z is the group

known as millennials (Zelazko, 2023). Millennials came

of age during an era of major technological shifts,

especially those associated with the rise in the use of the

Internet. Yet millennials don't merely use technology in

a passive way. They are a few of its primary motivators.

Over the course of ten years, Mark Zuckerberg—

possibly one of the most well-known millennials—grew

Facebook from a student directory into a potent and

significant social networking platform. The creators of

Instagram, Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, as well as

the creator of TikTok, Zhang Yiming, are other

millennial innovators (Zelazko, 2023). Millennials are

also considered the most educated generation.

Hopykns et al., (2021) research concentrates on

Emirati millennials in the educational setting. This study

concluded that the idea of 'language purity' is

unsustainable and undesirable in today's globalized

world. Both English and Arabic are often used. Arabic is

more common at home, but English is more common in

public settings, internet, and academic settings (Hopykns

et al., 2021, p. 187-189). Moreover, this generation has

earned considerable attention in the literature,

particularly regarding human resources in the workplace

(Alaleeli and Alnajjar, 2019).

2.1.5. Generation Z’s and Millennials’ linguistic

behavior

Gen Z and millennials share some common

linguistic traits in regions or countries in which English

functions as lingua franca such as the Gulf Countries

(Hopkyns et al., 2021 p. 177; Ribeiro Daquila, 2022, p.

337-338) or even where it is the co-official language, in

the Philippines for instance (Sales, 2022, p. 43). In

cosmopolitan cities such as Dubai and Abu Dhabi,

Emirati Gen Z and Millennials have developed a strong

proficiency in English, enabling them to carry out daily

activities like ordering meals, dining at restaurants, and

purchasing at shopping malls. Other traits are code-

mixing. Code-switching is a common term for alternate

use of two (or more) languages, or varieties of languages

in the execution of a speech act. In other words, code-

mixing is intrasentential while code-switching is

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 124

intersentential. Some scholars maintain that there is no

sharp distinction between code-mixing and code-

switching (Ritchie & Bhatia, 2013. p. 337, Tarihoran and

Sumirat, 2022).

Code-switching is also used to emphasize or

clarify a sentence. Even if a non-Arab individual is

proficient in Arabic, the Arab native speaker shifts to

English to ensure that he is understood (Hopkyns et al.,

2021 p. 178; Ribeiro Daquila, 2022, p. 319-320). Code-

mixing, the mixing of expressions, phrases, or words of

the grammar of two languages within a sentence —in this

case, Gen Z and millennials switch between Emirati

Arabic and English words, depending on the context and

the people they are communicating with (Hopkyns et al.,

2021, p. 178-180; Ribeiro Daquila, 2022, p. 319-320,

Alenazi, 2023, p. 7-8). An example of code-mixing

identified in our study in the UAE was:

1. khalni a post b a picture c

Let me a post b a picture c

Let me post a picture.

Al-Hussien and Belhiah's (2016) study in Abu

Dhabi supports this convergence, revealing Emirati Gen

Z's preference for English in reading, writing, and online

communication, reserving Arabic primarily for close

social circles (54% with friends, 90.7% with family). To

delve deeper, our research employs a questionnaire

(Appendix B) featuring 100 English words to analyze

their integration within Emirati Arabic across three

generations.

2.1.6. Baby Boomers

Baby boomers are the group born in the years

immediately after World War II, when birth rates spiked

significantly in several nations, including the USA,

Canada, Australia, Norway, and France. No one

component can fully explain each boom (Bump, 2023).

The fact that they identify as "digital immigrants" does

not imply that they utilize digital media for everyday

communication. They have significant purchasing

power, and they place a high priority on their health,

particularly women (Saucedo Soto et al., 2018; Carrillo-

Durán et al., 2022), who are worried about the financial

security of their families, want to support their

community, want to maintain their youth, and want to be

fully integrated into society and context (Carrillo-Durán

et al., 2022).

No other generation group has increased their

presence on social media platforms as much as baby

boomers, who went from using it at a rate of 24% in 2016

to 48% in 2017, according to research from the

Coolhunting Group (2017, p. 20-26). 91% of baby

boomers use one or more social media networks.

Additionally, baby boomers are more dependable in the

digital environment, more inclined to get better material,

read more, and spend more time on company websites.

Additionally, almost 70% of people love viewing videos

(Coolhunting Group, 2017, p. 20-26).

2.1.6.1. Baby Boomers’ Linguistic Behavior

There is little literature on baby boomer’s

linguistic behavior in the UAE. In a previous study

(Ribeiro Daquila, 2022, p. 329-330), Baby boomers

demonstrated to be more loyal to MSA when compared

to the younger generations Gen Z and millennials. They

rarely use verbs in English when speaking Emirati

Arabic, such as check, download, and cancel.

Nevertheless, these verbs are commonly used among the

younger Emirati generations. One study carried out in the

UAE (Al-Shibami and Khan, 2020, p.6128) concluded

that baby boomers might have difficulties with

technological advancements and they would rather learn

content through an instructor rather than learning from

the internet.

2.2. Early connections between the Emirates and

English

Only diachronically can English progress in the

UAE be understood. From 1809 to 1966, the UAE

experienced the foundation phase or the start of the

English language (Ribeiro Daquila, 2021 p.3; Schneider,

2007) occurred when Britain dispatched expeditions to a

few Qasimi ports in the regions of Sharjah and Ras al-

Khaimah, two of the Emirates that make up the UAE.

During this time, locals made their first interactions with

English. The ties between the UAE and England

deepened in 1820 when England implemented the

General Treaty in the area.

The second phase, also known as the

exonormative stabilization (Schneider, 2007), lasted

from 1966 to 2004 and saw the adoption of English as

the bureaucratic language and the language of instruction

at schools (Boyle, 2012; Ribeiro Daquila, 2021, p.4).

The third and last phase is the nativization

phase, which began in 2004 and continues today

(Schneider, 2007). This time is still developing;

therefore, it cannot yet be fully described. Karmani

(2005) asserts that the UAE government rapidly

modernized and westernized the educational system,

abandoning an antiquated memorization-based

educational system in the process.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A short questionnaire was made (see Appendix

A) to select participants for this study to find out their

age, gender, level of education, place of residence, and

of work when applicable.

A quantitative questionnaire containing 100

words in English that are often used in Emirati Arabic

was made specifically for this study (see Appendix B).

This questionnaire was initially a 30-English-word

questionnaire used in Emirati Arabic extracted from

Ribeiro Daquila’s study (2022, p.337-338). In the study

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 125

in 2022, other twenty-five English words used in Emirati

Arabic were suggested by Emirati participants and these

words were added to our present questionnaire. Finally,

we interviewed Emirati teachers at Alramsa Institute in

Dubai who helped us complete our 100-item

questionnaire. The data were collected from November

2022 to January 2023. All respondents lived mostly in

Dubai, however, in the baby boomers’ group, there were

8 respondents from Sharjah; in the millennials, there

were two participants from Sharjah who work in Dubai

and two male participants from Abu Dhabi. The

questionnaires were administered at Alramsa Institute in

Dubai. Some Emirati friends and teachers at Alramsa

Institute also participated as respondents and

collaborated to find the most participants for the

research; 10 questionnaires were administered in Dubai

Mall and Mall of the Emirates.

A second qualitative questionnaire was created

to find out Emiratis’ language preferences when they are

on social media and if social media led them to use more

English words in their speech (see Appendix C). We also

enquired about the amount of English they use when they

talk in Emirati Arabic and their fears or expectations

regarding such practice. Both questionnaires (Appendix

B and C) lasted around 12 minutes. AI was used in this

article to assist in the improvement of grammar accuracy

and connectors, and to generate the image in the previous

section.

3.1. Participants

Both questionnaires were administered in

Dubai to 150 participants:

50 generation-Z respondents born in 2007 and 2008 – 24

females and 26 males. All of whom go to high school in

Dubai and have never lived in an English-speaking

country.

50 millennial respondents born between 1978 and 1983

– 25 females and 25 males all from Dubai except for two

male participants from Abu Dhabi. They have never

lived in an English-speaking country.

50 Baby Boomers born between 1946 and 1964 – 24

females and 26 males.

3.2. Procedures

After signing the consent form, participants

received a laminated copy of the questionnaire in

Appendix B. Consequently, they were instructed that

they were supposed to pronounce the 100 English words

(see Appendix B) in the way they pronounce them when

speaking Emirati Arabic if they ever use them. For each

word they should express the frequency they use it when

speaking Emirati Arabic: always, almost always,

sometimes, rarely, or never. Next, the interviewer

explained to participants that they should form sentences

from verbs 1, 4, 6, and the adverb 66 already, which were

highlighted in yellow in their laminated version of the

questionnaire.

Finally, the interview started. After asking

about the frequency with which they used the first word

on the list in Appendix B — the verb to cancel —

participants were asked in Emirati Arabic: ‘Could you

provide a sentence with this verb?’ One example was the

following:

2. Ana a bakansil b il-party c

I a will cancel b the party c

I will cancel the party.

Asking these initial questions in Emirati Arabic

- their first language (L1) makes participants focus on

their L1. In addition, the Arabization of these verbs and

the use of the adverb already were analyzed.

We would have liked to analyze more words in

context, but as the questionnaire was long, we did not

want to demotivate participants. We video-recorded

three and audio-recorded five of the interviews

(Appendix B) to be able to observe more in depth how

these English elements are being pronounced in Emirati

Arabic. We did not record more because some

participants did not give consent to be recorded. We used

a cell phone Samsung S22 to record the participants.

Apart from marking the frequency for each word

(always, almost always, sometimes, rarely, and never),

the interviewer took notes manually of the pronunciation

of some words which were highlighted in green. He also

took notes of other words whenever it was considered

relevant. The technique employed was simple:

Marking the letter ‘A’ for the pronunciation of a word

with a typical Arabic accent, for instance: if participants

pronounced ‘bark’ instead of ‘park’. The letter ‘G.’ was

marked in front of the words meaning good

pronunciation, that is, the user pronounced the word

close to English, for instance, they pronounced ‘park’,

but without making the puff of air in the phoneme [p]

which is typical in English. The letter ‘N’ stood for

native-like pronunciation whenever participants changed

the pronunciation of the sentence, going from Arabic

pronunciation to English pronunciation when they used

an English word or expression. Besides, ‘Am’ was used

for American or Canadian native-like pronunciation. Just

‘N’ implied British native-like pronunciation. For

example, one female Gen Zeer while answering question

8.c. (Appendix C) ‘Can you name some words you use

in English when you are speaking Emirati Arabic

because of social media?’ gave an example in a sentence:

3. khalni a post b a picture c

Let me a post b a picture c

Let me post a picture.

When she said ‘khalni’, meaning ‘let me’ she

used Arabic pronunciation, as the sentence follows ‘post

a picture’ she used perfect American English

pronunciation. So, the interviewer underlined ‘post a

picture’ and marked ‘Am’ after it.

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 126

The interviewer encouraged participants to use

Arabic, for instance, by asking for confirmation using

Arabic instead of English:

Interviewer: y3ni, abadan? ‘You mean, never?’

Gen Zeer: Yes, abadan. ’Yes, never.’

Interviewer: wa il-kalima althania? ‘And the next

word?’

The pronunciation of the following words was

analyzed. They were highlighted in green (see Appendix

B) in all the questionnaires that were exclusively filled

in by the interviewer. The analyzed phonemes were

identified in a previous study as difficult sounds for

Emirati speakers to pronounce (Ribeiro Daquila, 2023b).

In verb 4. park and in the word 19. computer the

phoneme [p] was analyzed, as most Arabs tend to

pronounce it [b] (Ribeiro Daquila, 2023b, p. 4, 6-7). The

phoneme [æ] as in ‘cat’ /kæt/ was analyzed in words 1.

cancel, 20. laptop. The pronunciation of the letter r was

analyzed in the words 48. glittler and 66. already. As

shown in Ribeiro Daquila (2023b, p.9), the ‘Standard’

English r: postalveolar approximant in English is absent

in Arabic. If participants "flapped" or "tapped" the letter

r (one single alveolar flap [ɾ]) as in Scottish, in Welsh,

and northern England English, it was considered ‘N’.

This single flap is also present in Arabic. Arabic speakers

also perform the multiple alveolar vibrating sound or

trilled r [r], as in Spanish, Italian, and Catalan in the word

burro (meaning ‘donkey’ in Spanish and Catalan; and

‘butter’ in Italian). The trilled r sound is absent in

English.” and was marked as ‘A’ (typical Arabic sound).

And finally, we analyzed the sound l in the word

‘hospital’.

After completing the 100-English-word

questionnaire in Appendix B, respondents were asked

eleven qualitative questions in Appendix C. Participants

were asked if they knew the equivalent of each word in

MSA. In case they did not, it might indicate that the word

is disseminated in English and not in the official

language. When asked if they know the equivalent words

in MSA, participants tend to say ‘yes’. The interviewer

asked participants to go through the pages of the 100-

English-word questionnaire. This second questionnaire

was available in English and in Emirati Arabic (see

Appendix D) when participants had difficulty

understanding English. 16 baby boomers answered it in

Arabic. The majority responded to questionnaire C orally

in the presence of the interviewer while some took them

home and handed them in later.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We will present the results obtained from both

questionnaires in order to find out how English and

social media have been affecting Emirati Arabic in the

three generations in this study. In the 100-English-word

questionnaire, we will present how these English words

are pronounced in Emirati Arabic by the three different

generations, as well as a grammatical analysis of English

verbs and the adverb ‘already’ in Emirati Arabic.

4.1. Questionnaire with 100 words, verbs, and

expressions in English

Regarding the 100 English items used in

Emirati Arabic (see Appendix B), we divided them into

verbs, technology, food and food establishments,

medicine, cosmetics, means of transportation and car

vocabulary, and miscellaneous. We only added to the

graphs the vocabulary that is always or almost always

used by the respondents, for instance, if a participant

sometimes or rarely uses the word enjoy, we did not add

this data to the graphs.

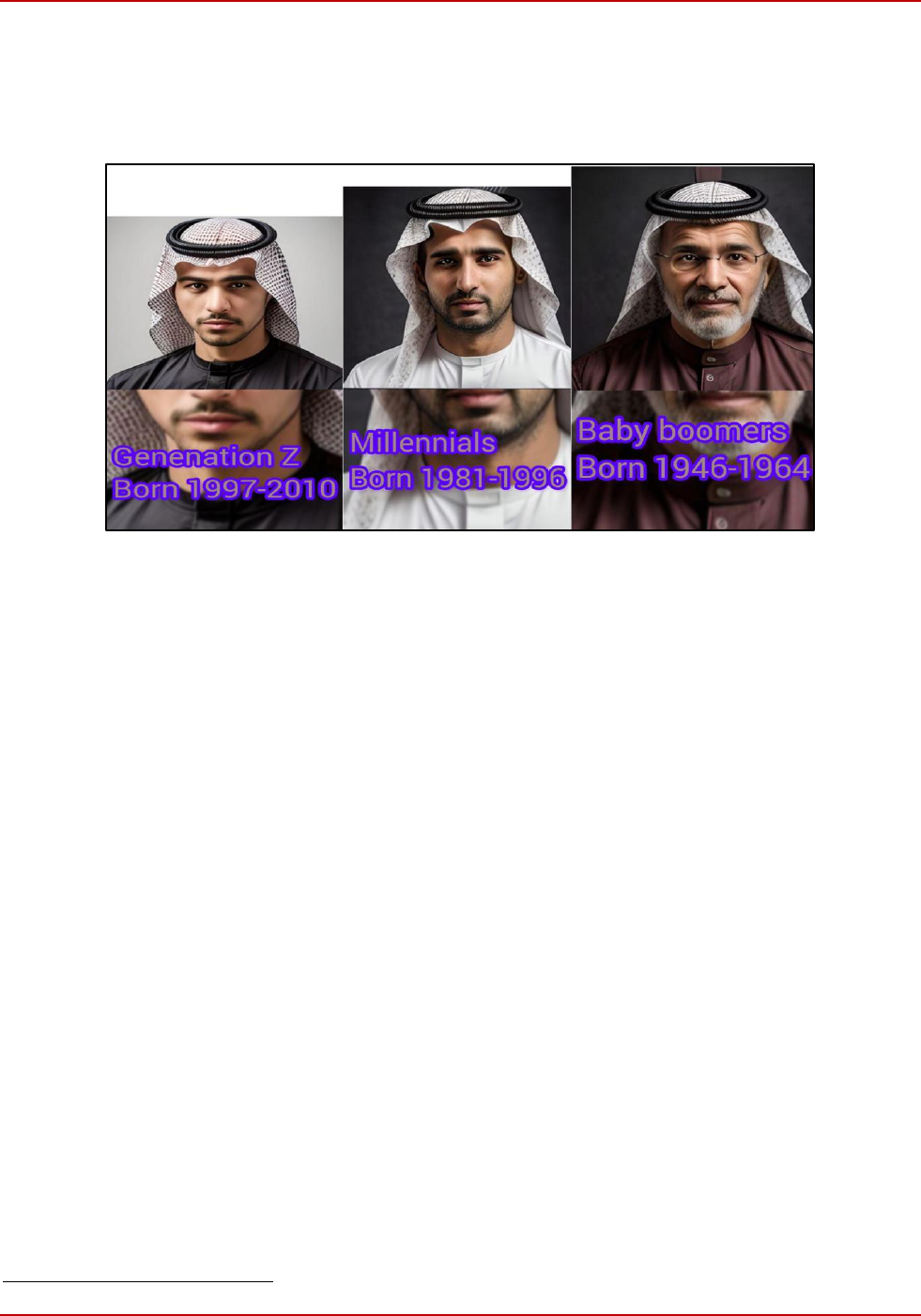

Figure 1: Verbs in English when speaking Emirati Arabic

With regard to the participants in Gen Z,

totaling 50 young Emiratis, all of them always or almost

always use the English verbs to charge, to download, to

park, to check, to cancel, and enjoy—only used in the

imperative form—when talking in Emirati Arabic, as we

can observe in Figure 1. The only verb that Gen Z does

not use exclusively in English is the verb ‘to finish’,

meaning ‘to quit or be dismissed from work’ in Emirati

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 127

Arabic; this may be because this verb is related to the

labor market, and Gen Z participants are still students.

Gen Z’s mean for verbs used in English is 96.6%, while

the millennials’ mean is 69.4%. On the other hand, 14%

of baby boomers use the verb to charge and ignore most

of the other verbs. Baby boomers’ mean is 2.57%. We

can observe that the younger the generation, the more

verbs in English they employ in Emirati Arabic. These

results are in keeping with our previous study (Ribeiro

Daquila, 2022). With regard to the verb to download,

78% of millennials in this study always or almost always

use this verb, while in our previous study, 60% of

millennials used it. Therefore, there was an 18% increase

in the use of the verb to download in the present study

regarding millennials.

Concerning the pronunciation of the verb to

park, five male and two female Gen Zeers pronounced it

as ‘bark’. This means 86% of Gen Z had correct

pronunciation. Although 86% of millennials use the verb

to park, only six participants (12%)— five females, and

one male—pronounce the phoneme [p] correctly, and the

remaining participants pronounce it as bark. All baby

boomers pronounced it as ‘bark’. This is due to the fact

that the sound [p] is non-existent in Arabic, and most

Arabs replace [p] with [b].

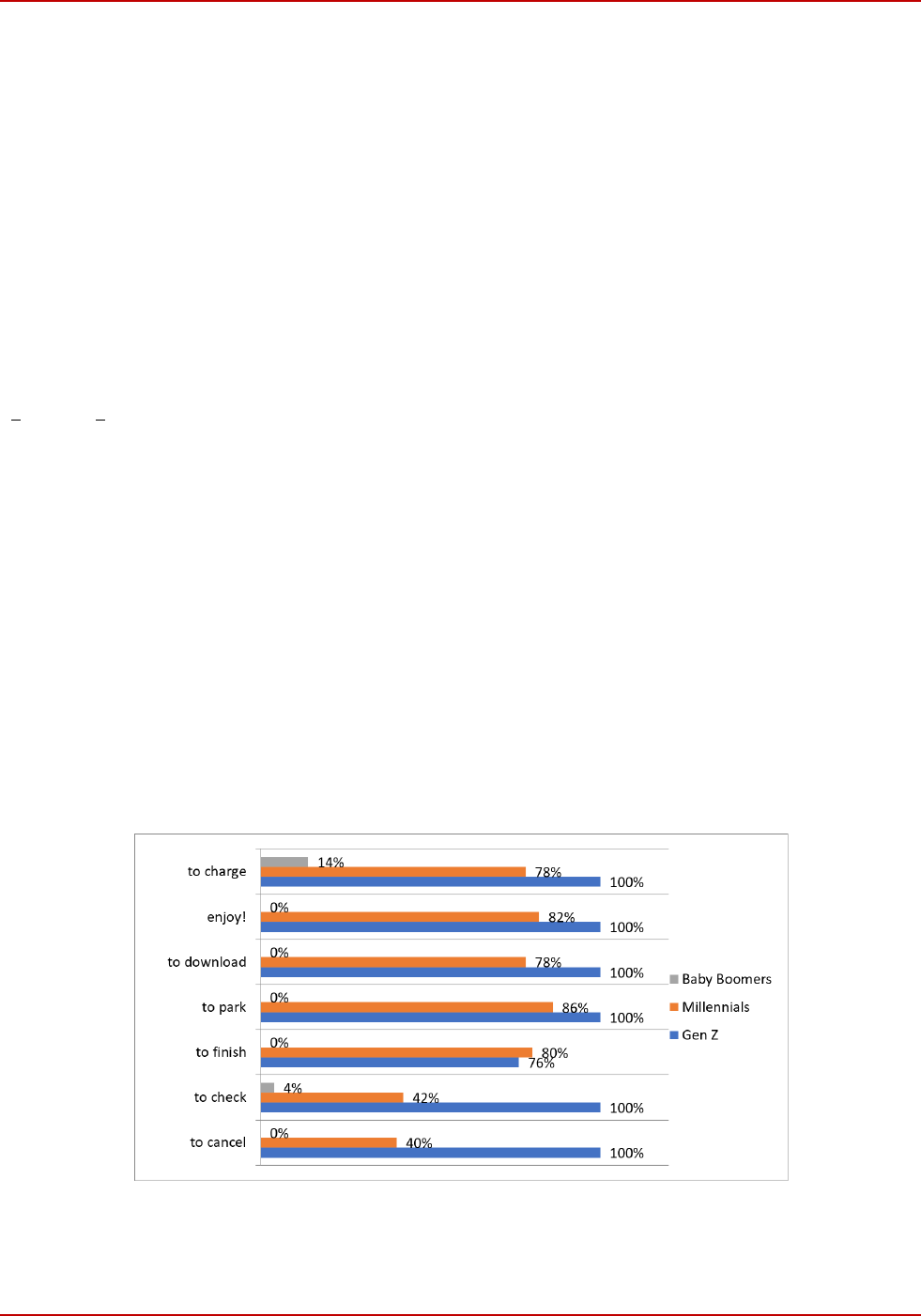

Figure 2: Technology

Regarding the words related to technology in

Figure 2, the word light is the only one used 100% in the

three groups. This word was introduced in the Emirates,

more specifically in Dubai, by an Indian businessman in

1957 (D’Mello, 1919; Ribeiro Daquila, 2022). As India

was an English colony until 1947, many English words

entered the Emirates straight in English. Some of these

words suffered phonological changes in India before

entering the UAE (Al Fardan & Al Abdulla 2014;

Ribeiro Daquila 2022, p. 320). Regarding the

pronunciation of the word PDF, all participants in the

three generations pronounce it in English either /pi di ef/

or /bi di ef/.

As we can observe, many technological words

are not commonly used among baby boomers, such as

GPS, telephone, USB, power bank, laptop, and www.

When asked what they call a laptop, baby boomers

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 128

answered ‘computer’ and regarding www., they said that

it is not important to say it out loud when you see a

webpage; another participant said that when he sends a

link, he just copies and pastes the address without the

need to say it. One participant answered: “I have seen

‘waw, waw, waw’ (referring to the consonant waw in

Arabic), but I think it is not MSA.”

Millennials always or almost always use

technological words more than 60% when compared to

baby boomers. Gen Zeers, the ‘technology generation’,

proved why they are called so, as Generation Z’s mean

for the words related to technology is 99.89%.

Baby boomers’ mean for the words related to

technology is 21.47%; millennials’ mean is 86%.

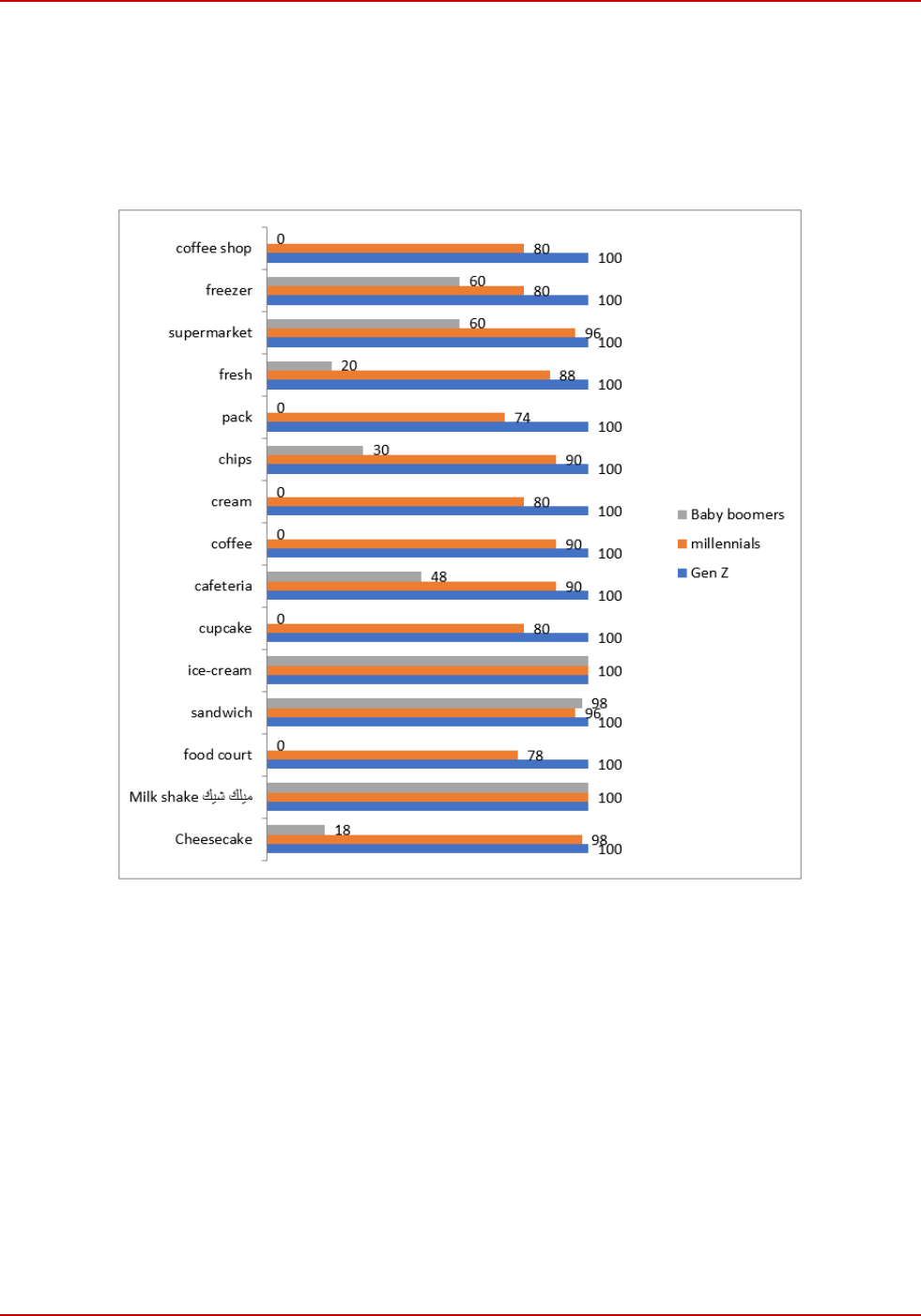

Figure 3: Food and Food Establishments

With regard to food and food establishments in

Figure 3, we can observe that some words belong to the

first linguistic phase, or the foundation phase (1809 -

1966) (Ribeiro Daquila, 2021, p. 3; Schneider, 2007),

such as milkshake, sandwich, and ice-cream, which

Emiratis do not know an equivalent in MSA; therefore,

they are used by the three generations. On the other hand,

some modern words are only used by Gen Z and

millennials, such as pack, coffeeshop, and food court.

Emiratis only experienced the concept of a food court

after the opening of the first shopping mall in the mid-

80s (Nair, 2002), that is, in the second linguistic phase of

Schneider (1966-2004).

We can conclude that, regarding food and food

establishments, millennials and Gen Zeers use more

words in English than baby boomers. Gen Z's mean is

100%, while the millennials’ is 88, and the baby

boomers’ mean is 28.93%. Concerning the word

milkshake among millennials, the mean rose from 86%

in our previous study (Ribeiro Daquila, 2022) to 100%.

In our previous study, there were only two participants

in the millennials who did not use the word milkshake.

One participant was from Al-Ain, a city not so

influenced by English, where 35% of the population

consists of Emiratis, while the other participant worked

for the government and confessed to avoiding using

foreign words. It is important to notice that Emiratis also

use the word coffee as a synonym for coffee shop.

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 129

Figure 4: Medicine

Concerning the medicine vocabulary in Figure

4, we can see that doctor is the preferred word by

Emiratis to mean doctor, instead of the MSA word

‘tabib’, 32% of baby boomers pronounce it as dakhtoor.

One female baby boomer also said that she might say:

‘baseer dakhtoor’ or ‘baseer dakhtar’ meaning ‘I’m

going to the doctor’ or ‘I am going to the hospital’.

Interviewer: Same same? meaning ‘the same thing?’

Baby boomer: Same same! meaning ‘the same thing.’

100% of Gen Z would not always/almost

always use the word hospitalia. But four girls said they

could sometimes use the word hospital. When the

interviewer asked one of them why she uses the word

hospital, she said that it was too sound ‘cool’ with her

girlfriends. Instead of using the regular plural suffix for

borrowed words -at hospitalat, she would say hospitals.

There are only 12% of baby boomers who sometimes say

hospital pronounced ‘ospital’, 80% rarely use the word

hospital and prefer the MSA word Moustashfa or the

Emirati variant dakhtar. These percentages for the word

hospital are not present in our graph, as we only added

words that are always or almost always used by Emiratis.

Another important observation is that 76% of Gen Z and

8% of the millennials pronounced the word hospital with

a perfect English velar l sound (dark l [ɫ]), while most

speakers belonging to millennials and all participants in

baby boomers pronounced the typical Arabic l sound

(light l [l]).

Baby boomers’ mean concerning medical terms

is 33.3%; millennials’ is 64%, while Gen Z’ mean is

66.6%. While millennials obtained the same mean for the

word coat abyad ‘white coat’ in our previous study, Gen

Z increased it from 96% to 100%.

Figure 5: Cosmetics

As we can observe in Figure 5, make-up items

are new in the Arab cultures, as baby boomers only put

on mainly eyeliners, or in Arabic, kohl, a type of coal

used by queens of ancient Egypt and still worn by

Bedouin men (Bateman, 2020). All female Gen Zeers, 24

out of 50 participants, use cosmetics vocabulary

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 130

exclusively in English, and they do not know the

equivalents of glitter, base, and lipstick in MSA.

Regarding boys, although they do not put make-up on,

when asked ‘would you call it a lipstick or do you know

another name for that?’ Some of the answers were: ‘My

sister says it’, ‘I hear it on Snapchat/Instagram’. If boys

did not know another word for the item, then we

considered it valid; in other words, we counted it as

always/almost always.

Regarding pronunciation, all female and three

male Gen Zeers pronounced glitter either with the final

[ɹ] sound as in American, Canadian, and Irish English

(retroflex) /ˈɡlɪt̬ .əɹ/, or non-Rhotic (typical British

pronunciation) /ˈɡlɪt.ə/. Eight female millennials were

marked with the letter ‘N’, meaning ‘British

pronunciation’, as they flapped the final r only once.

Almost all men in the millennials and all participants in

the baby boomers pronounced it with the trilled r [r], the

typical r sound in Arabic.

Baby boomers’ mean of words related to

cosmetics is 0%, while millennials’ mean is 67.2%, and

Gen Z’s mean is 86.4%. We can conclude that

globalization brought new cosmetic items into Emirati

culture. All these cosmetics given in English were

mentioned in our previous study (Ribeiro Daquila, 2022)

by female participants belonging to the Gen Z group as

examples of words they used in Emirati Arabic.

Regarding the word lipstick, the alternative word is not

the Arabic word 'ahmar alshifah lit. ‘red of the lips’, but

the French word rouge meaning ‘red’, as the clipped

form for the full form rouge à lèvres, lit. ‘red for the lips’.

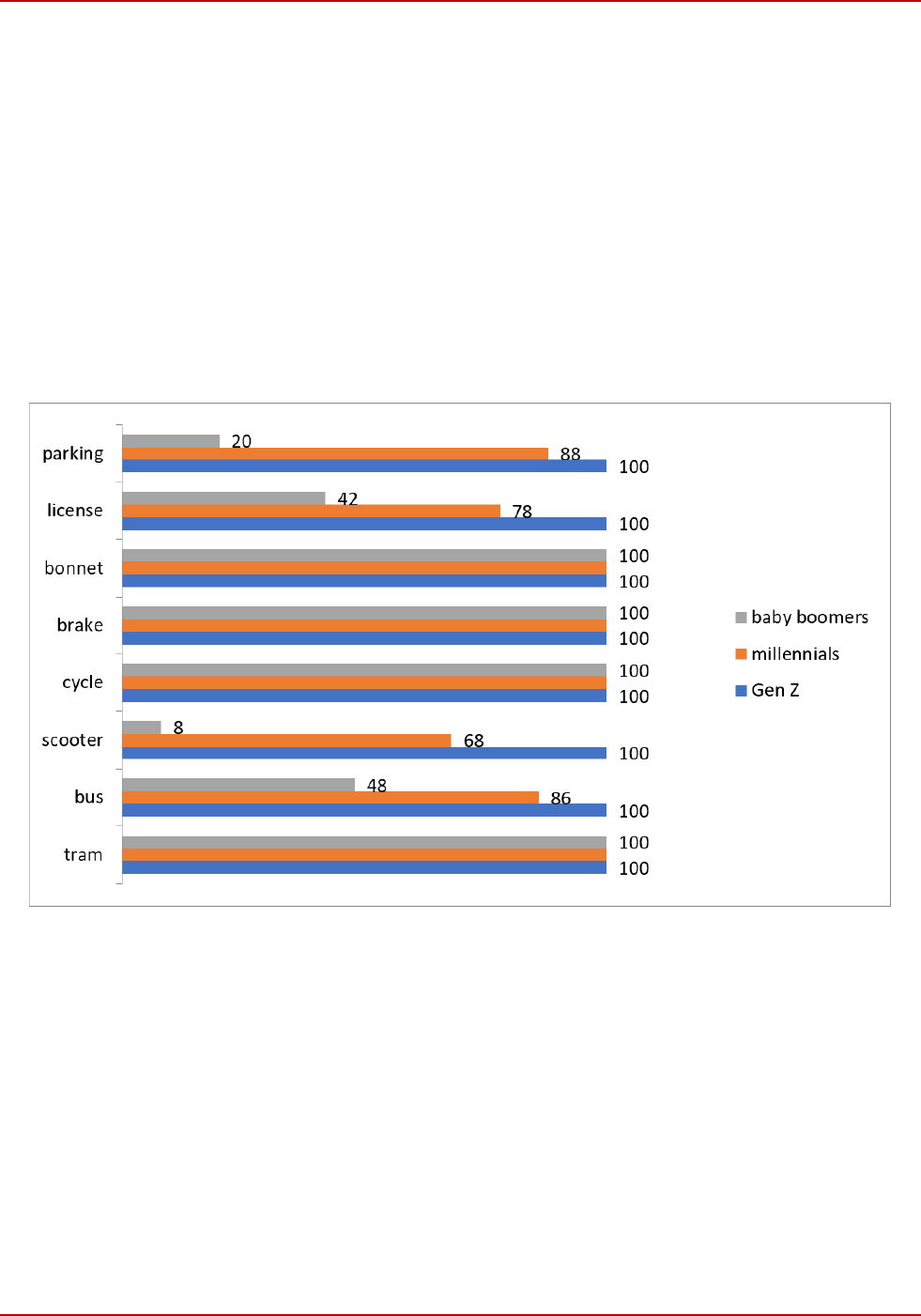

Figure 6: Means of transportation and car vocabulary

In Figure 6, The words tram, cycle (meaning

bicycle), brake, and bonnet are always used in Emirati

Arabic by the three generations. Regarding the word bus,

the first minibuses were introduced in Dubai in 1968 by

the Indian Tata Motors group (Gokulan, 2015), and since

then it has been called bus. The mean of Gen Z is 100%;

millennials’ is 90%, and baby boomers’ is 64.75%.

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 131

Figure 7: Miscellaneous

100

90

100

100

100

100

98

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

98

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

98

92

90

70

86

80

68

66

80

82

90

92

62

88

88

80

90

94

60

90

90

88

60

90

40

66

96

86

68

78

82

64

100

80

8

0

0

0

70

0

0

0

0

0

100

0

0

66

0

6

6

100

8

0

2

0

80

72

0

0

0

12

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

baby boomers

millennials

Gen Z

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 132

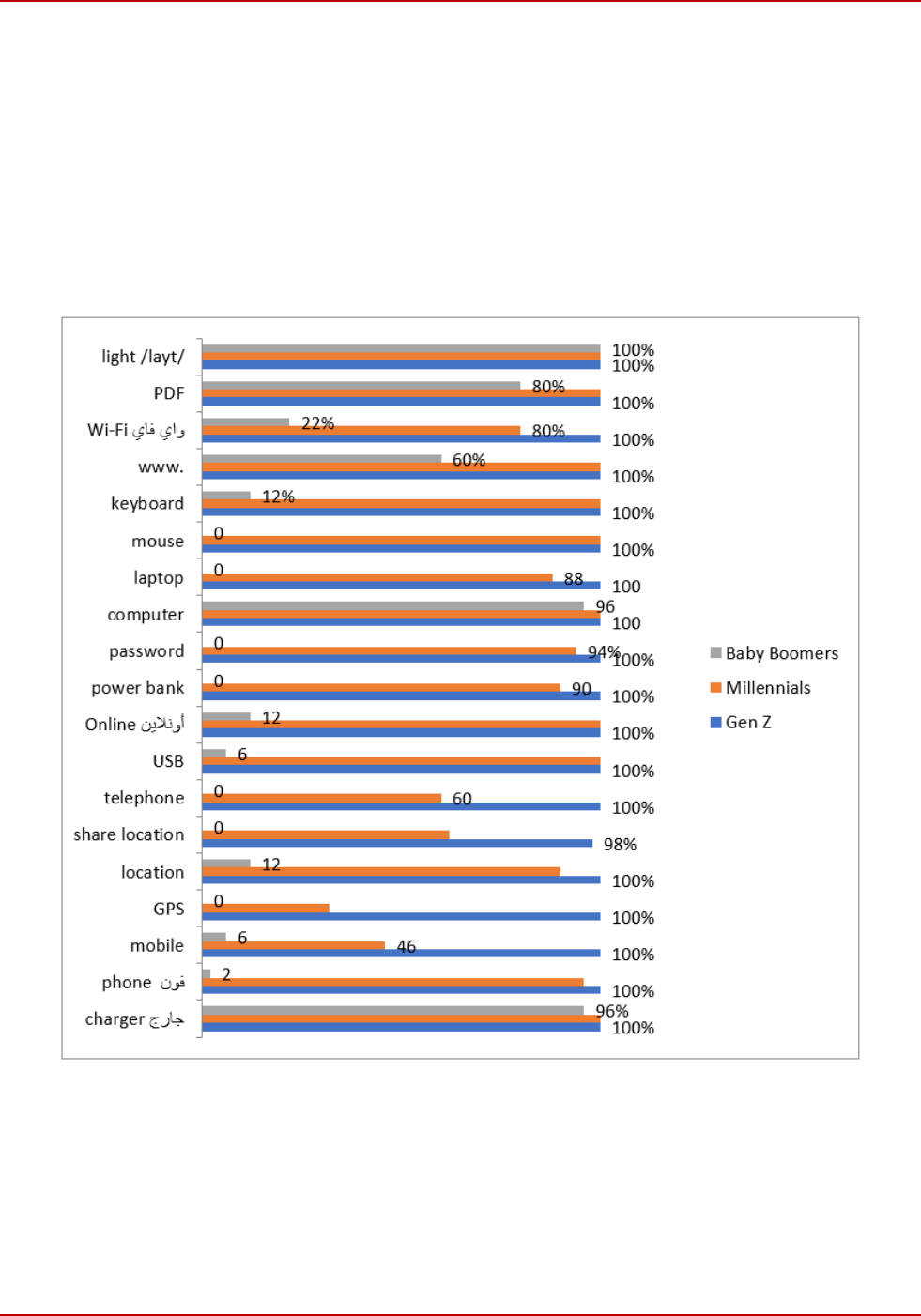

Figure 7 shows us miscellaneous words in

English used in Emirati Arabic. We can observe Gen Z’s

proclivity to words and expressions in English,

millennials using them more moderately and baby

boomers avoiding them. Gen Z’s mean for these words

is 99.65%. This mean is greater than millennials’, which

is 84.24%.

Baby boomers’ mean is 24.63%. The words

used by baby boomers are the ones that were introduced

into Emirati Arabic straight from English, like television,

wire, glass, shovel, and hose. The words that are used

less than 10% in this group were employed by female

speakers, like weekend, lab, and free. Only two male

Emiratis always/almost always use the word

businessman instead of the Arabic word rajul a’mal.

All Gen Zeers use the adverb already, whereas

62% of millennials use it. When asked to make a

sentence with already, participants came up with the

following sentences:

4. already a sharabt b gahwa c

already a drank b coffee c

I’ve already drunk coffee.

5. Hanan a already b aklat c

Hanan a already b ate c

Hannan has already eaten.

As we can see, the adverb already when used in

Emirati Arabic has a much more flexible position than in

English. There was a slight increase in the use of the

word already, both among millennials and Gen Z, from

60% to 62%, and 98% to 100% respectively.

30% of the Gen Z participants (all of them girls)

reported always using the word good luck, and 70% said

that they almost always employ it. In the millennial

group, 16% sometimes use good luck, and 4% (all boys)

rarely use it and prefer the Arabic form bi tawfeeq.

Regarding the word stamp, it is important to

highlight that in 1941 the British post was inaugurated in

Dubai (Onley, 2009; Ribeiro Daquila, 2023b). From

1948 on, all letters sent in the Trucial States used British

stamps showing the British monarchy. Therefore, the

word stamp is common in Emirati Arabic; even 90% of

baby boomers sometimes or rarely use this word when

speaking Emirati Arabic.

Our first research question poses the question

whether there are phonetical and/or grammar differences

in the incorporation of English words and expressions in

the three groups.

With respect to pronunciation, we can conclude

that some words keep the original pronunciation in

English, this was the case of the word PDF, which was

Arabized in more than 50% of the cases to /bi di ef/ or

maintained the [p] sound. Baby boomers tend to Arabize

the pronunciation of English words in Emirati Arabic

when compared to the younger generations. For instance,

the verb to park, was pronounced as ‘bark’ by 100% of

baby boomers, while 88% of millennials also Arabized

the pronunciation. Only 10% of male and 4% of female

Gen Zeers Arabized the word, pronouncing it ‘bark’

while the remaining 86% pronounced park with a [p]

sound.

Regarding the word computer, the percentage

of English-like pronunciation slightly decreased among

Gen Zeers and millennials. Nine male and five female

Gen Zeers – totaling 28% – Arabized the pronunciation

of the word computer, pronouncing it as [b] instead of

[p]. Only 1 male and 3 female millennials (8%)

pronounced a clear [p] sound. All baby boomers

pronounced it as [b]. This Arabization may be because

the [m] is voiced, and the tendency is to pronounce a

voiced sound after it, in this case, [b]. There were nine

cases in which the [p] sound in the word computer was

not clear. A study in a laboratory should be carried out to

analyze this phenomenon.

Concerning the sound of the letter r in the word

glitter. All female and 11 male Gen Zeers used either the

American retroflex sound [ɹ] or the British non-rhotic r.

Eight male Gen Zeers who were marked with ‘N’,

pronounced the final r with a single flap [ɾ] (the typical

Scottish pronunciation). Most male millennials and all

participants in the baby boomers pronounced a trilled r

[r]. Eight female millennials were marked with the letter

‘N’, as they pronounced it with a single flap. Regarding

the word ‘already’ (where [ɹ] is in mid-position), two

female Gen Zeers pronounced a single flap r which was

considered ‘N’. In final position in the word ‘glitter’, this

single flap r sound did not occur among the female Gen

Zeers. One female Gen Zeer also pronounced the trilled

r [r], common in Arabic. Seven female and 4 male

millennials pronounced a single flap. The remaining

participants pronounced it as a trilled r [r].

Regarding the letter l in final position, 76% of

Gen Z (24 females and 14 males) pronounced the word

hospital with the English velar l sound, or dark l [ɫ].

Female Gen Zeers outperformed the male participants.

Our findings are in keeping with those of Oga-Baldwin

and Nakata (2017), who concluded that, compared to

boys, girls exhibit a stronger propensity to engage in

language-focused activities, such as learning a foreign

language.

8% of the millennials also pronounced it with

the English velar l sound, while most millennials and all

participants in baby boomers pronounced the typical

Arabic l sound (light l).

With regard to the phoneme [æ] as in cat /kæt/,

it is the most Arabized sound. Participants had to create

sentences in Arabic with the verb cancel and the word

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 133

laptop. Only 4 female Gen Zeers pronounced these two

words with a perfect [æ] sound.

We can conclude that the younger the

generation, the less Arabization of sounds there is.

Concerning grammar, we could observe that all

the verbs follow the conjugation of Arabic verbs, except

for the verb enjoy, which is only used in the imperative

form, and the verb post and take, mentioned by one

female Gen Zeer, in the sentence ‘khalni post a picture’,

meaning ‘let me post a picture’ and in the expression

‘khalna take a selfie’, meaning ‘let’s take a selfie’. These

were the only three verbs that were not Arabized in our

study.

The adverb already has a flexible position in the

verb; however, there are some rules. The following two

sentences are correct, for instance:

6. Hanan a already b aklat c is-simach d

Hanan a already b ate c the fish d

Hannan has already eaten the fish.

7. Hannan a aklat b is-simach [

4

] c already d

Hannan a. ate b the fish c already d

Hannan has already eaten the fish.

It would be incorrect to start this sentence with

already. That is, ‘already Hanan ate the cake’ is

incorrect. Nevertheless, it is possible to start a sentence

with the adverb already when we omit its subject. This

is uncommon in English, but it is common in Latin

languages and in Arabic. The following sentence is

correct:

8. already a sharab b maai c

already a drank b water c

He has already drunk water.

This shows that when integrating certain

English grammatical categories into Emirati Arabic,

their integration follows the grammatical structure of

Arabic, not English.

Regarding our second research question ‘Is the

influence of English in Emirati Arabic greater in the

present Gen Z group aged 15-16, when compared to Gen

Zeers aged 17-18 surveyed three years ago (Ribeiro

Daquila, 2022)?’, a slight increase in the use of English

by Gen Zeers in this present study was noticed when

compared to our previous study, whose data was

collected prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The word free increased from 82% to 100%.

However, let us break down this figure: 82% of Gen

Zeers always used the word free when speaking Emirati

Arabic, and 18% sometimes used it. In the present study,

we have 86% that always use free and 14% that almost

always use it. Even though this small increase is not

statistically significant, future studies should analyze

whether these percentages keep increasing. In other

words, it should be analyzed whether Gen Zeers keep

increasing the number and frequency of English words

in Emirati Arabic.

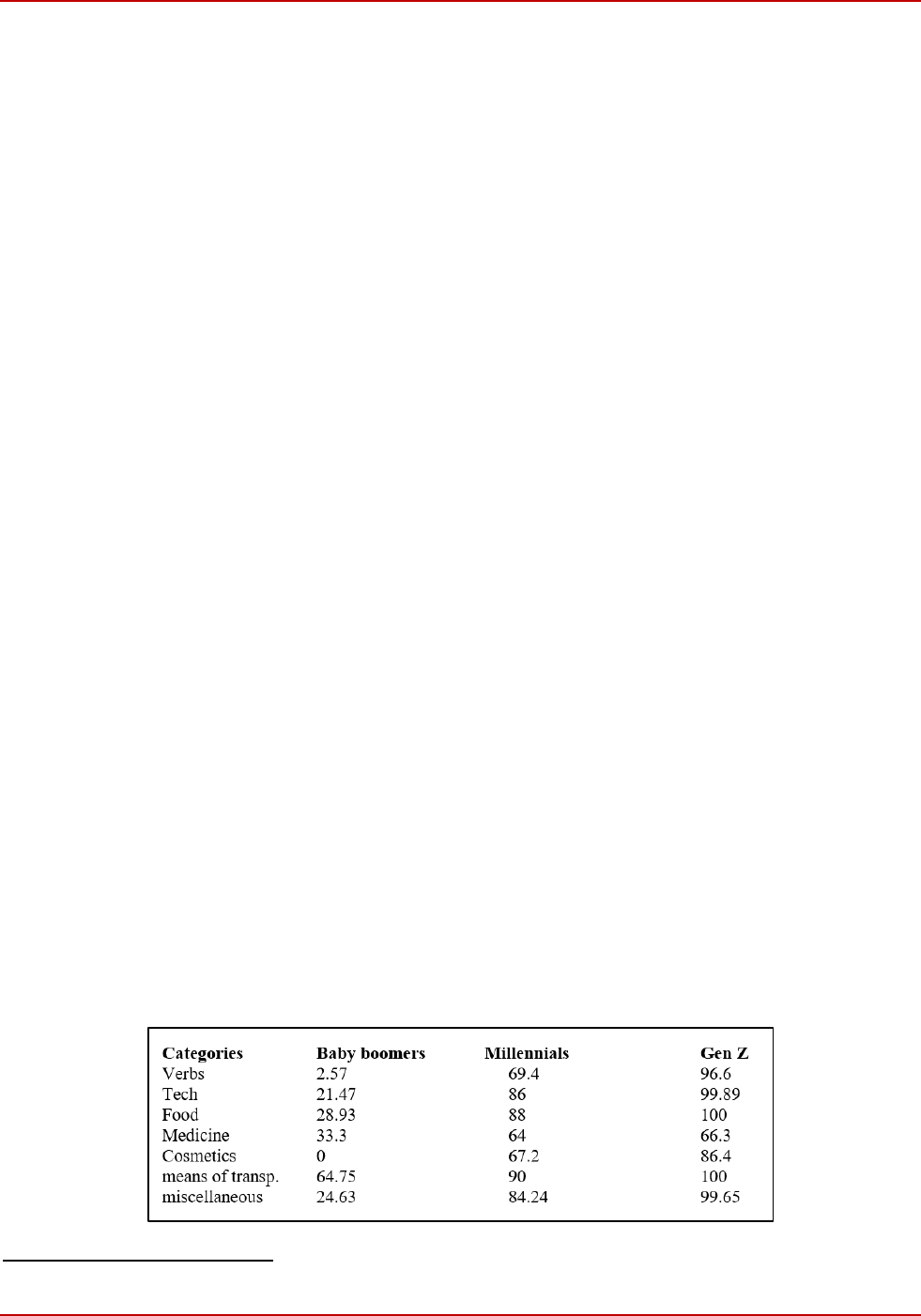

With regard to our third research question,

which analyzes English usage across the three

generations, Table 1 reveals a marked increase in English

adoption among Gen Z Emiratis compared to Baby

Boomers. On average, Gen Z participants used English

significantly more frequently across all seven categories

examined. The most striking discrepancy appears in

technology-related vocabulary, where Gen Z

demonstrated near-complete reliance on English

(99.89%) compared to a mere 21.47% for Baby

Boomers. Furthermore, Gen Z consistently surpassed

Millennials in English usage across nearly all categories,

suggesting a generational shift towards increasing

English integration in everyday communication.

Notably, while Baby Boomers rarely used English words

for cosmetics (0%), Gen Z embraced it readily (86.4%).

This aligns with trends of globalization and

digitalization, where English serves as a common

language for online interaction and technology

consumption. However, while the trend towards English

prevalence within Gen Z is evident, the table also

highlights variations across categories. In medicine, for

example, both Millennials and Gen Z exhibited a decline

in English usage compared to Baby Boomers, reflecting

the importance of different terminology in healthcare

contexts, such as moustashfa and dakhtar.

Table 1: The mean of each category for the three generation cohorts

4

Simach in Emirati Arabic equals to samak in MSA,

meaning ‘fish’.

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 134

4.2. Second Questionnaire

In this second questionnaire (see Appendix C),

we analyzed the influence of social media in the Arabic

language, its use during the pandemic, and the linguistics

concerns of the three generations regarding the future of

Emirati Arabic.

Concerning question one ‘Are there other

words you can think of?’, Emirati Gen Zeers suggested

the following words in English that they regularly use

when speaking Emirati Arabic.

Aksayt – Derived from the English word ‘excite,’ it is

used to express excitement or enthusiasm. For example:

9. Ana a aksayt b l’il-party c

I a excited b about the party c

I am excited about the party.

Baby /Beibi/ – it is commonly used as a term of

endearment for a loved one. For example:

10. Inta a baby b

You a baby b

You are my baby.

Joke – used to refer to a joke, often inserted into Arabic

conversations. For instance:

11. ’Andak a joke? b

At you a joke? b

Do you have a joke?

Cute – used to describe something or someone as

adorable or charming. For example:

12. Hatha a baby b cute. c

This a baby b cute. c

This baby is cute.

Happy– for instance:

13. kul a sana b wa c inta d happy e

every a year. b and c you d happy e

Happy birthday!

Selfie – an example provided by a female Gen Zeer:

14. khalna a take a selfie b

let us a take a selfie b

Let us take a selfie.

Hashtag – for example:

15. La a tansa b the hashtags c

Don’t a forget b the hashtags c

Don’t forget the hashtags.

The following English words and phrases

related to the workplace and professional environments

were also suggested by Emirati millennials:

CV – for instance,

16. tarrasht a CV b

I sent a CV b

I sent a CV.

Deadline – for instance,

17. ‘andy a deadline b at 3 pm c

At me a deadline b at 3 pm c

I have a deadline at 3 pm.

Interview – for instance:

18. ‘andy a interview b alyoum c

At me a interview b today c

I have an interview today.

We recommend adding these words to future

studies in order to build a greater English lexicon in

Emirati Arabic.

As regards question two, ‘Is there any word

from the list above that you do not know how to say in

Modern Standard Arabic?’, baby boomers know all the

equivalent words in Arabic. It is also true that there are

some words that they did not understand, such as

cupcake, power bank, share location, food court, glitter,

and base. Millennials, on the other hand, did not know

the equivalent in Arabic for some words, such as –

power bank, scooter, gas cylinder, food court, glitter,

base, and hose. The most alarming result is Gen Z’s, who

did not know the equivalent in Arabic of 36 words. These

are the words that were unknown to more than twenty-

five Gen Zeers: those related to cosmetics: glitter, base,

lipstick; words related to technology: Wi-Fi, GPS, power

bank (some said charger, which is not the same), and

PDF; food-related vocabulary: cheesecake and

milkshake; and transportation: scooter.

In order to answer research question 4, ‘Does

social media have an impact on the increase in English

words and expressions in Emirati Gen Z speech?’,

questions 4 to 10 were created (see Appendix C).

Question 3 will be analyzed later in this section.

Concerning question four, ‘During the

pandemic, did you increase the use of social media?’ The

three generation cohorts confessed to increasing it.

However, Gen Zeers were the ones who increased the

most, an average of 4 hours and a half more per day,

while millennials and baby boomers increased by around

3 hours. Most millennials confessed to teleworking, so

they could not spend more time on the phone, whereas

baby boomers preferred to spend time with the family

and the females also had to take care of the house chores.

Regarding question five, the most used social

media for baby boomers were Facebook with 49 users,

including Facebook Messenger, and YouTube with 41

users. 13 baby boomers also reported using Instagram.

The reasons why these were baby boomers’ favorite

platforms were 74% because they could get information

about the pandemic; 86% to be in touch with family and

friends; and 60% to shop online.

Regarding millennials, 40 participants used

YouTube, 37 used Facebook, and 33 used Instagram.

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 135

The reasons why these were their favorite platforms in

the case of millennials were 62% because they could get

information about the pandemic; 82% to be in touch with

family and friends; and 64% to shop online.

Concerning Gen Z, 50 Gen Zeers used

Instagram, 43 used TikTok, and 39 used Snapchat. 48%

of Gen Z preferred Instagram, TikTok, and Snapchat to

kill time; 68% to follow influencers and brands; and

mainly to be in touch with their friends (78%).

These results are not in accordance with

Tarihoran and Sumirat’s study (2022, p. 61) with

Indonesian Gen Zeers, whose favorite platform was

Facebook with 43.15%, followed by YouTube with

31.25%.

Regarding the present use of social media –

question number 6 – baby boomers use it to be in touch

with friends and family (78%), to read the news (38%),

and to purchase (34%). 80% of millennials use social

media to be in touch with friends; 62% to work, do

research, or work-related issues; 60% to make new

contacts; 58% to read the news; 56% to purchase items;

and 52% to follow brands and celebrities. They use

English either because it is trendier or because they have

just seen the information in English and retweeted it (in

the case of X). Concerning Gen Z, 96% use social media

to be in touch with friends; 68% to make new contacts;

64% to see the content of brands; and 60% to follow

celebrities.

With respect to question seven, ‘When you use

social media, which language do you use?’, baby

boomers post and comment in Emirati Arabic, but more

than posting, they use social media to see others’ posts.

They feel that Arabic is their language; therefore, it

should be reflected in their posts. They think that social

media is affecting the Arabic language as more and more

posts are in English; hence, all of them would like to see

more posts in Arabic. Millennials post more than 85% in

English as they seek a global reach and consider English

the language of social media. On the other hand,

Millennials see English as an inevitable consequence of

globalization and modernity; 84% do not mind

posting/reading posts in English, while 16% would like

to see more posts in Arabic. With respect to Gen Z,

which is the generation of technology, 96% post

exclusively in English. They see English as the

international language of communication, and they do

not see English as a threat to their Arabic.

With reference to question 8, ‘Do you use more

English words in Emirati Arabic because of social

media?’, 82% of baby boomers answered no. Other

answers were: ‘a little’, ‘only influencer, haha’, ‘I don’t

think so’, and ‘a couple of words, maybe’. 89% of

millennials said yes. The ones who disagreed answered:

‘I don’t think it is influence; it is globalization’, ‘I don’t

see any harm in saying influencer or hashtag’; ‘We speak

like the rest of the world’. 88% of Gen Z answered yes.

The ones who differed replied: ‘The influence is

everywhere, social media is just another more’, ‘Going

to a mall makes me speak more English than using

Snapchat.’ One male Gen Zeer said that he likes to add

stories on Snapchat in which he is listening to the Emirati

hip-hop singer ‘Freek’, who sings both in Emirati

Arabic, and English. In his case, he prefers to listen to

music in Arabic and whenever he comments on a Snap,

it depends on the friend, he might use either English or

Arabic.

Gen Zeers indicated that they enjoy listening to

English-language music, both on TikTok and Instagram;

one female participant indicated that the Reels contain

mostly songs in English, and another female participant

mentioned that the trendy songs on TikTok are always in

English, which contributes to more English words and

expressions in their vocabulary in Arabic. Two female

Gen Zeers confirmed that they use most make-up

vocabulary in English because of influencers or make-up

tutorials they watch on social media.”

The participants use the following social media words

when speaking Emirati Arabic:

Baby boomers: Two female participants mentioned the

word hashtag, 4 participants mentioned social media,

and 3 females gave the word influencer as an example.

The majority of participants did not come up with any

words.

Millennials: hashtag (12 participants), social media (3

participants), selfie (9 participants), and swipe (1

participant).

Gen Z: block (4 participants), selfie (4 participants),

swipe (7 participants), screenshot (3 participants),

hashtag (5 participants), followers (4 participants),

password (3 participants), live (2 participants), content

(1 participant), social media (2 participants), post (2

participants), location (1 participant), take a selfie and

post a picture (1 female Gen Zeer).

These results are in line with Alenazi’s study

(2023, p.20), which demonstrated that social media

significantly increased and propagated several English

expressions in Saudi culture. Saudis learned various

English words through social media apps, and they

utilized these phrases in oral and written interactions

throughout their everyday lives. Depending on how the

Saudis used the English language, this phenomenon was

either beneficial or detrimental.

In order to answer our final research question,

‘Can English be considered a threat to the endurance of

Emirati Arabic?’, questions 3, 11, and 12 (see Appendix

C) were analyzed. With reference to question three,

which enquires about the influence of English on Arabic,

100% of baby boomers are concerned about such

influence. 84% of millennials also see English as a threat

to Emirati Arabic. These results are in keeping with our

study (Ribeiro Daquila, 2020, p. 6-7), in which 84% of

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 136

parents, whose mean age was 38, believed that MSA and

Emirati Arabic should be the focus at school in lieu of

English. Gen Z, on the other hand, sees English

proficiency as development and a signal of globalization.

One male Gen Zeer answered: ‘Dubai is international,

you can’t do business without English’; 6 male and 4

female Gen Zeers mentioned English as a key to

succeeding at university; one male Gen Zeer said: ‘We

need to pass the English exam to enter university’; 1

female and 6 male Gen Zeers said that they can’t have a

good salary without English.

Regarding question 11, exclusively to baby

boomers and millennials, ‘Does the fact that the new

generations might speak English instead of Emirati

Arabic worry you?’ Not only do baby boomers see

English as a threat to future generations, but they also

consider it a threat to Gen Z at present. They were

unanimous in saying that Gen Z overuses English and is

losing some Arabic vocabulary.

68% of millennials see the use of English as an

inevitable consequence of globalization and modernity,

while 32% see the overuse of English as a threat to future

generations. Three female millennials also mentioned

that future generations might lose Arabic proficiency.

One female millennial Expressed: ‘The young

generation doesn’t know Fusha (MSA), and it will be

worse in the future, but the dialect will not die, but

change.’

Concerning question 12, exclusively to Gen

Zeers, ‘Are you concerned about the fact that your kids

might speak English instead of Emirati Arabic?’, the

answer was no. Participants were unanimous in saying

that they were willing to have bilingual kids and that this

would make their kids prepared for the future. Fourteen

female Gen Zeers stated that they would speak both

Emirati Arabic and English with their kids. Seven female

Gen Zeers expressed that they would enroll their kids in

international schools, while 4 female participants

mentioned bilingual education for their kids. Male Gen

Zeers were very succinct, the great majority just

answered ‘no’.

As the three groups do not see eye to eye on

whether English poses a threat to Arabic in the UAE, we

suggest further studies to analyze the complex

sociolinguistics of the country. The findings regarding

our fourth research question are in keeping with Kennetz

and Carroll’s (2018) study, which concluded that even

though English is also perceived as having a detrimental

impact on culture and the local language, it nonetheless

provides Emiratis with access to education, work, and

the global community. They claim that English has

undoubtedly established a place in Emirati society, rather

than that it is completely displacing native Arabic.

5. CONCLUSIONS

As we have observed, English words and

phrases are being used in the Arabic language in the

UAE, particularly among Gen Z, and social media is also

responsible for such influence. These results are in line

with the studies of Siemund et al., (2020), Carroll et al.,

(2017), Kennetz and Carroll (2018), and Ribeiro Daquila

(2020, 2022) concerning an increase in English words in

Emirati Arabic by Gen Z, and are also in keeping with

Tarihoran and Sumirat’s (2022) and Alenazi’s (2023)

research regarding the increase of English words in

Indonesian and in Saudi Arabic –respectively – due to

social media use.

English has ingrained itself into many Gen Z

Emiratis' daily lives and identities (Ziad, 2019, Ribeiro

Daquila, 2022). The UAE's cosmopolitan atmosphere

and willingness to interact with the international

community are reflected in the country’s bilingualism.

This influence is also due to globalization, technology,

the widespread use of the internet, the labor market

(Ameen and Anand, 2020), and the change in the school

curriculum from Arabic to bilingual English and Arabic

(Ziad, 2019, Ribeiro Daquila, 2022).

Social media and media in general are

responsible for making English more and more popular

among Gen Z, who has easy access to English content

through social media platforms, streaming services, and

internet platforms, English language use is being

increasingly supported (Alenazi, 2023, p. 5). Gen Z also

stated that they feel comfortable posting in English. The

fluency of Generation Z in English is due in part to their

early exposure to the language (KHDA, 2011; Ribeiro

Daquila, 2020, 2023b).

Emirati Arabic demonstrates some grammatical

characteristics in the use of the adverb already that has a

flexible position and the Arabization of most English

verbs, except enjoy, which is always used in the

imperative form by most users, and post and take, which

were used in the bare infinitive form by a Gen Zeer.

More research is needed to analyze the Arabization of

verbs in the UAE.

Regarding pronunciation and having Arabic as

the matrix language, when Emiratis use some loan words

from English in the middle of their speech, Gen Z has a

more English-like pronunciation when compared to

millennials. Girls in Gen Z and millennials outperformed

the boys. Baby boomers use Arabic pronunciation to

pronounce words in English, for instance, they

pronounce park as ‘bark’ and computer as ‘combuter’.

This may be because they went to school in the Arabic

curriculum.

It is important to note that the degree of the

English language effect on Emirati Gen Z may vary

based on elements like urbanization, educational

attainment, and exposure to transnational trends. Arabic

Jean Pierre Ribeiro Daquila, Sch Int J Linguist Lit, Apr, 2024; 7(4): 120-144

© 2024 | Published by Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 137

continues to be the primary language for formal

communication and cultural expression in Arab

communities, despite the fact that English phrases have

undoubtedly entered the vocabulary of many Gen Z

Arabs, as previous studies (Ribeiro Daquila, 2022;

Alenazi, 2023) indicated.

We hope to have sparked new scholarly interest

in the linguistics and repertoires of Emiratis. Even

though the current study could only scratch the surface

of the fascinatingly complex linguistic environment of