EN EN

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

Brussels, 14.7.2020

SWD(2020) 137 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

EVALUATION

of the

Directive 2007/59/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2007

on the certification of train drivers operating locomotives and trains on the railway

system in the Community

{SWD(2020) 138 final}

1

Table of contents

ABBREVIATIONS ………………………………………………………………………………………….2

1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 3

2. PURPOSE AND SCOPE ...................................................................................................................... 4

3. BACKGROUND TO THE INTERVENTION ..................................................................................... 5

4. IMPLEMENTATION / STATE OF PLAY ........................................................................................ 10

5. METHOD............................................................................................................................................ 12

6. ANALYSIS AND ANSWERS TO THE EVALUATION QUESTIONS .......................................... 15

7. CONCLUSIONS ................................................................................................................................. 31

ANNEX I: PROCEDURAL INFORMATION …………………………………………………………….34

ANNEX II: STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION ……………………………………………..…………36

2

ABBREVIATIONS

ATO

Automatic Train Operation

CEFR

Common European Reference Framework

CER

Community of European Railways

ERA

European Union Agency for Railways

ERTMS

European Rail Traffic Management

System

ETF

European Transport Workers’ Federation

IM

Infrastructure Manager

NLR

National Licence Register

NSA

National Safety Authority

RINF

Register of Infrastructure

RMMS

Report on Monitoring Development of the

Rail Market

RU

Rail Undertaking

TSI

Technical Specifications for

Interoperability

3

1. INTRODUCTION

The creation of a European Railway Area through the integration of national rail systems

is an EU long-term target, aiming to make rail more competitive and thereby transport

more sustainable. Making sure that national borders no longer constitute obstacles for EU

wide operations is at the heart of it. This includes ensuring that cross-border operations

are not hampered by diverging national staff requirements and standards requiring

changing train drivers and crew every time a train crosses a border. The European train

driver certification scheme set out by Directive 2007/59/EC is an important step in

facilitating cross-border operations.

In many Member States, the Railway Undertakings (RU) are among the largest national

employers. At the end of 2016, just over 1 million people were employed in the European

railway sector

1

. Between 2011 and 2016, reported employment rose by 8% in total

2

.

Based on the data

3

collected by the European Union Agency for Railways (ERA), at the

end of 2016 there were more than 180.000 train drivers in the EU; out of these, about two

thirds were certified based on Directive 2007/59/EC on the certification of train drivers

(the Directive) and one third not yet certified based on the Directive.

Since adoption of the Directive, the ageing of the workforce in the rail sector intensifies.

The structure tends towards older workers, with workers older than 40 years typically

representing more than 50%. Despite the apparent improvement in the age pyramid over

the years, the high percentage of railway staff older than 50 in 2016 suggests that a large

contingent of workers is expected to leave the railways soon.

The ageing of staff increases the need for developing lifelong learning programmes and

increasing recruitment efforts. It is also important to avoid a loss of knowledge and

competencies when generations change, in particular for key occupations with skill

shortages such as train drivers.

At the same time, since the adoption of the Directive, digitalisation of railways has

gained momentum, offering important opportunities to increase reliability, improve

performance and efficiency of the rail system, and fundamentally change the way

companies provide service to customers and organise their operations.

The European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS)

4

, has the potential to reduce

costs dramatically by eliminating trackside signalling, as well as boosting capacity and

safety. The current state of deployment of ERTMS raises the issue of combining “new”

and “traditional” technologies during the transition; train drivers have to master both. A

1

Based on the 6

th

Report on Monitoring Development of the Rail Market (RMMS) adopted in February

2019. The 7

th

RMMS report is currently under preparation.

2

However, as mentioned in the 6

th

RMMS report, this change appears to be dominated by increases in

the number of reported staff at both infrastructure manager and incumbent railway undertaking in

France.

3

Data from 18 Member States, Switzerland and Norway

4

ERTMS aims at replacing the different national train control and command systems in Europe. Its

deployment will enable the creation of a seamless European railway system and increase European

railway's competitiveness. ERTMS has two basic components: ETCS, the European Train Control

System, is an automatic train protection system (ATP) to replace the existing national ATP-systems;

and GSM-R, a radio system for providing voice and data communication between the track and the

train, based on standard GSM using frequencies specifically reserved for rail application with certain

specific and advanced functions.

4

study conducted in the Netherlands

5

indicated that driving in ERTMS may lead to a low

activation of the driver and could decrease its situational awareness. At the same time,

with ERTMS the driver receives key information on both static and dynamic

characteristics of the tracks several kilometers ahead, e.g. speed restrictions subsequent

to an occupied track, which allows the driver to anticipate. This is of particular

importance for freight trains in order to improve energy consumption and limit the efforts

on the coupling. ERTMS therefore provides all the necessary data for the driver, and in

longer term, it is expected to influence the content of training regarding the

infrastructure.

In the future, the Automatic Train Operation (ATO)

6

is expected to dramatically change

the interaction between the infrastructure and the traffic management system, thanks to

ever more intelligent onboard systems. The first levels of ATO assist train drivers to have

better performance in terms of speed profiles, provide easier interfaces with the

infrastructure and dispatch, and further increase the safety of the rail operations.

Demand for new and advanced skills will be manifold in all future scenarios. Fully

tapping the potential of automation and digitalization will undoubtedly lead to gains in

customer service, costs and safety.. Moreover, given that the ageing of workers in the rail

sector is a significant concern, the opportunities offered by the technological innovation

could help identifying ways to attract young people to the sector. The present evaluation

of the Directive is an important contribution to making sure that the skillset remains

adequate in changing circumstances.

2. PURPOSE AND SCOPE

Purpose of the evaluation

The aim of this evaluation is to provide a complete overview of the implementation of

the Directive as well as the effectiveness of the measures it introduced.

The results of this evaluation may be used as an input for possible future policy

development, including for impact assessments.

Scope of the evaluation

The evaluation assesses to what extent the Directive has contributed to reaching its

objective of setting an effective framework for EU-wide acceptance and comparability of

procedures and requirements for licences and certificates and a resulting positive impact

on the interoperability and mobility of train drivers.

The evaluation is based on the standard evaluation criteria of relevance, effectiveness,

efficiency, EU-added value and coherence.

5

R. van der Weide, D. de Bruin, M. Zeilstra: ERTMS pilot in the Netherlands – impact on the train

driver

https://www.intergo.nl/public/Publicaties/13/bestand/2017_ERTMS%20pilot%20in%20the%20Netherl

ands%20%E2%80%93%20impact%20on%20the%20train%20driver.pdf

6

Automatic train operation (ATO) is an operational safety enhancement device used to help automate the

operation of trains. The degree of automation is indicated by the Grade of Automation (GoA), up to

GoA level 4 (where the train is automatically controlled without any staff on board).

5

This evaluation covers all elements and provisions of the Directive as amended by

Commission Directive (EU) 2014/82

7

, and assesses its implementation and effects from 4

December 2007, when it entered into force. It takes into consideration the gradual

phasing-in and transition periods as indicated in the Article 37 of the Directive.

This evaluation covers all Member States except Cyprus and Malta (which do not

possess a railway network on their territory and hence, do not apply the Directive).

3. BACKGROUND TO THE INTERVENTION

Description of the intervention and its objectives

In the past, in the absence of a certification scheme with EU-wide acceptability and

comparability, train drivers licences and certificates obtained in a Member State were not

recognized in another Member State. Hence, the train drivers had to undergo training and

certification in each and every Member State they worked in. This situation led to

considerable duplication with all the significant effort, costs and time involved.

The Directive aimed at addressing the aforementioned patchwork of national solutions

regarding the certification of train drivers by providing EU-wide acceptance and

comparability of procedures. Its main objective is to facilitate the mobility of train drivers

in the context of the increasing opening of the railway market while at least maintaining

the current safety levels. The specific objectives were to define and implement common

minimum requirements for certification of train drivers, their EU-wide interoperability

and to streamline training.

The Directive is built in large parts on the “Autonomous Agreement on the European

licence for drivers carrying out a cross-border interoperability service”

8

of 27 January

2004 concluded by the sectoral social partners Community of European Railways (CER)

and the European Transport Workers’ Federation (ETF). Through this agreement, the

parties decided to set up a European licence for drivers system, which was aimed at:

Facilitating the interoperability of driving staff as a means to increase international

railway traffic;

Maintaining and even increasing the level of safety, and, towards this end,

guaranteeing the quality level of the driving staff’s performance by ensuring and

verifying compliance with competence level geared to the relevant European railway

systems;

Contributing to the efficiency of management of drivers in interoperability services

by the railway companies;

Reducing the risks of social dumping.

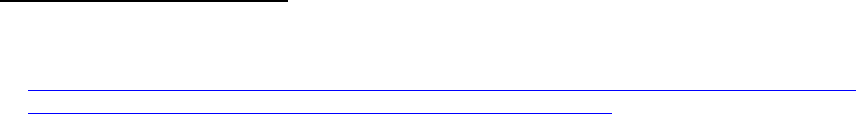

The intervention logic of the Directive is summarised in the diagram below.

7

OJ L 184, 25.6.2014, p. 11-15

8

https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=521&langId=en&agreementId=1099

6

Enhancingthe interoperability

of train drivers

Mai ntain and raise the safety

level

More efficient RU

ma nagement of

interoperable train drivers

Wi de diversity of

national legislation

on trai n drivers

Administrative

burden (cost,time )

for rail undertakings

especially SMEs

Operational

difficulties in

orga nising cross-

border services

Specify a nd implement common

mi nimum requirements for

certification of train drivers

EU-wi de interoperability

Simplify training of train drivers by

taki ng advantage of

implementation of harmonized

systems

Specification of mimimim

requi rements for medical

examinations and regular check-

ups

Bi lateral a pproach

between MS

regarding

interoperability

Common specification of

ps ychological profiles

Common specifications of skills for

personal i n cros-border operations

Ens uring the follow-up of the level

of competence of the certified

train drivers

Us e of a simplfied communication

system combined wi th basic

knowledge of common language

Developing and implementing

operational rules harmonized at

European level

Lack of common

framework for

certification of train

drivers (e.g.

duplication of

training)

Reducing both the duration of

additional drivng training and the

necessary a ssessment associated

Reducing the duration of railway

undertaking certification

Reducing the costs of training and

certi fication of drivers

Reducing the risk of error, accident

and incident

Facilitating the entry into market

of small and medium-sized rail

undertakings

Greater mobility of train drivers

between ra il undertakings

Greater fl exibility in the

employment market

Increased quality of services

provided by train drivers

General Speci fic Operational

Objecti ves

Probl ems

Outputs

Results

Impacts

Expected effects

A more competitive rail sector

permitting the interoperability of

train drivers a nd ensuring high

sa fety s tandards

Increased market share for rail

undertakings compared withroad

hauliers

7

An important contextual element of the pre-Directive period was the Second Railway

Package

9

and its four interlinked legislative proposals under which staff certification was

still based on documents to be provided by the RUs. This included the proof of evidence

of staff meeting the requirements of the Technical Specifications for Interoperability

(TSI) or the national rules and that the staff has been duly certified. It has rapidly become

clear that common rules should be adopted on certification of train drivers to facilitate

their interoperability and improve their management and mobility.

Another important contextual element was the agreement reached between the CER and

ETF on general social conditions for the European Railway Area. This agreement,

implemented by Directive 2005/47/EC

10

, reaffirmed the general objectives of the

introduction of a European train driver’s licence:

enhancing the interoperability of train crews so as to stimulate international railway

transport;

maintaining and even raising the safety level and thus guarantee the quality of

services provided by train drivers while ensuring and verifying the level of skills

adapted to the European networks used;

contributing to the efficiency of methods for managing interoperable train drivers for

railway undertakings;

reducing the risk of downward pressure on social conditions.

Against this background, the Directive entered into force on 4 December 2007. It lays

down conditions and procedures for the certification of train drivers operating rolling

stock on the railway market of the EU.

More specifically, the train drivers shall have the necessary fitness and qualifications to

drive trains and hold a licence demonstrating that they satisfy minimum conditions

(medical requirements, basic education and general professional skills), as well as one or

more certificates indicating the infrastructure and the rolling stock the holder is

authorised to drive. The licence is issued by the competent authority that is the National

Safety Authority (set up according to the Safety Directive

11

), while the certificates are

issued by Rail Undertakings (RUs) and Infrastructure managers (IMs). Moreover, the

procedures for maintain the validity of licences and certificates are also laid down.

The Directive also specifies the tasks of competent authorities in the Member States

(related for example to issuance, renewal and withdrawal of the licence, monitoring of

train drivers, carrying out inspections, and monitoring of the certification process), train

drivers and other stakeholders such as RUs and IMs (setting up the procedures for

issuing, updating and suspension of the certificate, ensuring that the train drivers they

contract are in possession of valid certification documents).

9

OJ L 164, 30.4.2004, p. 114–163

10

OJ L 195, 27.7.2005, p. 15-17

11

OJ L 138, 26.5.2016, p. 102-149

8

The Directive provides for a gradual phasing in of the certification scheme:

By 29 October 2011, the certificates or licences of drivers performing cross-border

services, cabotage services or freight services in another EU country or working in at

least two EU countries had to be issued in accordance with the Directive.

At the latest on 29 October 2013, all new licences and certificates had to be issued in

accordance with the Directive.

Four related acts concern the models for licences and certificates, the registers of licences

and certificates and training:

The annexes to Commission Regulation (EU) 36/2010

12

set out the models for the

train driving licences, complementary certificates and their certified copies, and

application forms for the train driving licences.

Commission Decision 2010/17/EC

13

provides for the basic parameters for registers of

train driving licences and complementary certificates.

Commission Decision 2011/765/EU

14

defines the criteria for the recognition of

training centres, of examiners of train drivers, and for the organisation of

examinations.

Commission Recommendation 2011/766/EU

15

sets out recommended practices and

procedures for the recognition of training centres providing professional training, and

of examiners of train drivers and of train drivers candidates.

Since 2007, the Directive has been amended by the following acts:

Commission Directive 2014/82/EU of 24 June 2014

16

as regards general professional

knowledge and medical and language requirements. A main element of this revision

was the replacement of Level 3 for language requirements with level B1 Common

European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR).

Commission Directive (EU) 2016/882 of 1 June 2016

17

as regards language

requirements. The aim of this revision was to give the possibility of exempting, from

the B1 level requirements, train drivers on border crossing sections, who drive only

up to the first station after crossing the border with the neighbouring Member State.

Commission Regulation (EU) 2019/554 of 5 April 2019

18

as regards language

requirements, which creates the legal basis for testing alternative options to the

current language requirements in pilot projects.

In accordance with Article 31(2) of the Directive, when the adaptation of the Annexes

concern health and safety conditions, or professional competence, the social partners

have to be consulted prior to their preparation.

12

OJ L 13, 19.1.2010, p. 1–27

13

OJ L 8, 13.1.2010, p. 17–31

14

OJ L 314, 29.11.2011, p. 36–40

15

OJ L 314, 29.11.2011, p. 41–46

16

OJ L 184, 25.6.2014, p. 11-15

17

OJ L 146, 3.6.2016, p. 22–24

18

OJ L 97, 8.4.2019, p. 1–5

9

Baseline and points of comparison

The establishment of a single market for railway transport services required a framework

for the opening up of the market and regulating it at EU level. The gradual extension of

the access rights of licensed RUs led to an increase in the number of companies operating

in more than one Member State and to higher demand for drivers trained and certified in

more than one Member State.

In 2002, the Commission contracted a study on training and requirements for railway

staff (including train drivers) in cross-border operations

19

. Its conclusions highlighted the

wide diversity of national legislation on train drivers certification and the administrative

burden resulting from this, as well as operational difficulties in organising cross-border

services:

There were significant differences from country to country with regard to the

educational level required for external recruitment for all staff categories. Internal

recruitment was preferred by some of the former national railways in order to make

best use of redundant staff.

All countries had medical requirements for staff selection and a system of medical

check-ups; the requirements for the different staff categories and the frequency of

medical check-ups were slightly different between countries.

There were also significant differences in the approach to training; for example, the

balance between classroom training and on-the-job training was different from

country to country, with more on-the-job training in Italy, France, Belgium, Sweden,

Norway and Switzerland.

Similar differences in recruitment levels and composition of training were also observed

for other staff categories.

Moreover, based on cross-border case studies, it was assumed that a number of two- or

three-system locomotives

20

were likely to be introduced for cross-border freight

operations in Europe,with the aim of saving time at border stations; this could lead to a

demand for more cross-border operations for train drivers. However, requirements on

working hours, language skills and training needs for specific knowledge in “foreign”

operational rules were expected to limit this development.

The main conclusions from the study contracted in 2002 highlighted the need for

common formal requirements for a driver licence for cross-border operations, while

national licensing systems would manage the knowledge and skill requirements for

national routes, operating procedures and rolling stock. Moreover, it was suggested to

replace the mutual recognition of requirements between “railway networks” by either

minimum requirements at European level or mutual recognition of requirements between

Member States.

19

ATKINS: Training and staff requirements for railway staff in cross-border operations; Final Report, 28

November 2002.

20

These locomotives would provide a single journey over two or three electrification systems without

interruption from changing locomotives.

10

4. IMPLEMENTATION / STATE OF PLAY

Description of the current situation

Transposition

Article 36 of the Directive required the Member States to bring into force the laws,

regulations and administrative provisions necessary to comply with the Directive by

4 December 2009 and to communicate them to the Commission. By the deadline,

22 Member States had not communicated the transposition to the Commission; hence, the

Commission launched 22 non-communication infringements still in 2009, which were all

closed subsequently. In case of Croatia, the deadline for transposition was 1 July 2013

and it was met.

Following the conformity assessment, the Commission examined for five Member States

whether the transposition was correct and complete. Subsequently infringement

procedures were launched against Austria, Czech Republic, and Hungary. Two

infringement procedures have been closed (Hungary in 2018 and Czech Republic in

2019); while in case of Austria, the procedure (2015/2151)

21

is still on-going and it

mainly refers to the designation of the competent authority.

Two complaints were received regarding the implementation of the Directive: one

regarding the fees charged for issuing the train driver licence, which have been perceived

as a disproportionate financial burden, in contradiction with the provisions of the

Directive, and a second one regarding a possible lack of implementation of the Directive

in Portugal. In case of the first complaint, no infringement of the Directive was identified

and hence the file was closed. In the second case, further information was necessary and

the Portuguese authorities were requested to provide clarification. Their answer is

pending.

Implementation

A first assessment of the implementation of the Directive was done by the European

Union Agency for Railways (ERA) in the report

22

submitted to the Commission in

December 2013 (as requested by Article 33 of the Directive). This report is based on the

outcome of a survey conducted in spring 2013 with stakeholders’ participation and on the

experience gathered by ERA during 5 years of accompanying the implementation process

in the Member States; hence it does not present the views of the Commission but of

stakeholders and ERA.

The report

23

shows the benefits of the system but it also reveals a series of provisions,

which are unclear or incomplete as well as inconsistencies in the text, which impact on

the implementation. Along the same lines, the majority of the stakeholders participating

in the public consultation

24

that took place from 3 March to 10 June 2016 signalled that

21

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/api/files/document/print/EN/ip_19_4262/IP_19_4262_EN.pdf

22

https://www.era.europa.eu/sites/default/files/activities/docs/141118_art_33_report_development_certifica

tion_train_drivers_en.pdf

23

https://www.era.europa.eu/sites/default/files/activities/docs/141118_art_33_report_development_certificati

on_train_drivers_en.pdf

24

https://ec.europa.eu/transport/content/evaluation-directive-200759ec-certification-train-drivers-operating-

locomotives-and-trains_en

11

some provisions of the Directive are more difficult to implement, for example by leaving

considerable room for interpretation.

More specifically, the following categories of issues have been identified:

Use of terms: The title of Article 16 is “Periodic checks”, then in the text it is about

“periodic examinations and/or tests”, while Annex IV speaks about “medical

examinations”. While both concepts are actually similar, it may have created

confusions for some of the stakeholders.

Provisions regarding the licence

o Some stakeholders regret that there is no provision in the Directive explicitly

stating that the train driver shall have only one valid licence, even though the

idea of a licence that is valid EU-wide and the provisions regarding supervision

of the train driver or suspension of the licence implies this.

o Some stakeholders pointed out that the absence of specific provisions for

assessing the psychological fitness of the candidate train driver (Annex II point

2.2) could lead to requirements being applied differently from one Member State

to another. The stakeholders consider that it would be justified to have more

specific provisions, given the relevance of the psychological fitness for the safe

exercise of the duties. The same applies to the minimum frequency for the

psychological checks, where some stakeholders consider that it would be

justified to specify that frequency.

o Provisions regarding the certificatesSome stakeholder regret that the list with

exemptions from possessing a certificate for the respective infrastructure (Article

4.2) does not cover cases such as driving work trains or non-exceptional services

of historical trains. They consider this would be justified.

Moreover, in the opinion of stakeholders, the list is not well aligned the

operational practice and includes provisions such as the requirement of a second

driver sitting next to the driver without certificate during driving. However, for

certain types of traction unit, it is not possible to “sit next to the driver”, and

therefore, the exemption cannot be used. Further, the purpose of informing the

infrastructure manager whenever an additional driver is used is not clear and may

have created some confusion.

o Categories of drivers (Article 4.3): While the definition of category B driver is

clear as it embraces drivers carrying passengers and/or goods, the definition of

category A appears to be less clear x

o Some stakeholders regret the absence of provisions on the geographic scope of

validity of a accreditation and recognition issued to persons or bodies (Article

20). This leads to in practice to differences between Member States; some of

them recognise the accreditation/recognition issued in another Member State

while in some other Member States there is no full recognition and the accredited

persons or bodies have to submit another application. The stakeholders consider

that it would be justified for the accreditation/recognition to have an EU-wide

validity; this would provide for more legal certainty and reduce the administrative

burden on both the applicants and the competent authorities.

Other provisions:

o When a driver ceases to work for a RU or an IM, he shall inform the competent

authority without delay (Article 17). Given that the licence remains valid in case

12

of cessation of employment, provided that the conditions defined in Article 16.1

continue to be fulfilled, and the National Licence Register (NLR) does not

include such information, the use of such information is unclear for the competent

authorities. Some competent authorities developed their own system of

information and registration of the employment status of train drivers, despite the

lack of clarity on the purpose.

Annex I point 4 of the Directive refers to minimum data contained in national

registers, which relates to the licence as well as to the certificate. However,

Article 22 of the Directive distinguishes between data on the licence to be

registered by the competent authorities and data on the certificate to be recorded

by each RU and IM in the registers for certificates (Art.22.2). This inconsistency

leads to confusion among stakeholders on the scope of the NLR, more

specifically whether it should include only data on the licences or also data on

certificates.

Outdated provisions and references

The basic requirements for the licence include the successful completion of nine years of

primary and secondary education, and basic training equivalent to level 3 referred to in

Council Decision 85/368/EEC of 16 July 1985 on the comparability of vocational

training qualifications between the Member States of the European Community

25

.

However, this Decision has been repealed in October 2008 by Decision

No 1065/2008/EC of 22 October 2008

26

and it was superseded by the adoption of the

Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2008 on the

establishment of the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning, which

was revised in 2017

27

. However, the aforementioned basic requirement continues to be

based on the repealed Decision, which creates confusion for the competent authorities,

who have to assess the applications for the licence.

These aspects lead to difficulties in the implementation and to different application in

Member States. Consequently, the effectiveness of the certification scheme could be

limited and the specific objectives to define and implement common minimum

requirements for certification of train drivers, facilitate their EU-wide interoperability

and to streamline training not met in full.

5. METHOD

The evaluation of the Directive was based on a series of questions focused on relevance,

effectiveness, efficiency, coherence and EU-added value both in a general way as well as

regarding specific provisions of the Directive.

Relevance

1) To what extent are the operational objectives of the Directive relevant and

proportionate to address the need of overcoming the differences in certification

25

OJ L 199, 31.7.1985, p. 56–59

26

OJ L 288, 30.10.2008, p. 4

27

Council Recommendation on the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning, OJ C 189

of 15.6.2017, p.15-28..

13

conditions for train drivers across Member States (single market objective) while

maintaining the high level of safety of the EU railway system (safety objective)?

2) To what extent are the requirements set out in the Directive relevant instruments to

achieve the objectives?

Effectiveness

3) To what extent has the Directive contributed to EU-wide interoperability of train

drivers?

4) To what extent has the Directive contributed to enhancing and facilitating the

mobility of train drivers?

5) To what extent has the Directive contributed to maintain or raise the safety level?

6) Has the Directive led to any positive and/or negative unintended effects (both in

terms of impacts and results)? If so, what is the extent of these effects and which

stakeholder groups are affected the most?

7) To what extent the form of intervention was the most adequate one?

Efficiency

8) To what extent are the costs incurred by stakeholders (such Member States

authorities, Infrastructure managers, Railway Undertakings, train drivers)

proportionate to the benefits achieved?

Coherence

9) Are the objectives of the Directive coherent with the general EU objectives, notably

of the 2011 White Paper on Transport and current EU policy priorities/objectives?

10) Are the provisions of the Directive (still) consistent with the co-existing EU railway

legislation despite its evolution? Can inconsistencies of references and definitions,

and overlaps of provisions be identified? Is there scope to streamline the existing

regulatory framework?

EU added value

11) What is the EU-added value of the common certification scheme for train drivers?

Short description of methodology

The main source for qualitative data is the outcome of the stakeholders consultation

carried out for the evaluation, which included the aforementioned public online

consultation and the stakeholders meeting. The public online consultation was open to all

interested parties and received 72 replies. There were 40 participants to the stakeholders

meeting, which was open to all interested parties.

The public consultation was longer than the mandatory 12 weeks in order to give as

many stakeholders as possible the possibility to contribute.

14

The stakeholder meeting took place in Brussels on 1 July 2016 with the aim of

presenting the preliminary results of the consultation and gathering additional input from

stakeholders.

In addition, two meetings with the Social Partners took place on 22 April and

5 September 2016.

In the framework of these two exercises, stakeholders were asked to:

assess the strengths and weaknesses of the Directive,

express their opinions about different measures in the Directive and their usefulness,

describe their experiences with its implementation and problems encountered,

assess whether a revision of the Directive would be desirable, and,

identify possible enhancements that should be considered in any future revision of the

policy in general.

The information gathered in the public consultation complements the findings from the

report submitted in December 2013 by ERA. This report is based on the consultation and

experience of a variety of stakeholders, more specifically on the outcome of a

questionnaire survey conducted in spring 2013 and the experience ERA gathered during

five years of accompanying the implementation process in the Member States.

In addition to the public consultation and the ERA report, other sources of information

were position papers of various stakeholders, the impact assessment accompanying the

proposal

28

for the Directive and the final report (including the annexes) of the

aforementioned study contracted in 2002.

The data collected was used to respond to the evaluation questions. All the analytical

findings constitute the basis for the assessment on how the Directive has performed on

the five defined evaluation criteria of relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, coherence and

EU added value. This in turn allowed establishing the causality and the attribution of

effects to the intervention.

When developing the methodology for answering the evaluation questions, it became

necessary to cover additional issues that were not initially foreseen, but proved necessary

to evaluate the five evaluation criteria. Therefore, a series of additional issues were

included in the questionnaire for the public consultation and hence addressed in the

evaluation:

on the possible re-consideration of using smart cards

29

;

on the usefulness of a certification system for other crew members performing safety-

critical tasks

30

; and

28

COM(2004) 142 final

29

Article 34 of the Directive foresees the examination of the possibility of using smartcards combining

the licence and certificates. However, following the cost-benefit analysis hereof prepared by ERA

(https://www.era.europa.eu/sites/default/files/activities/docs/229_20121214_report_on_smartcards_en.

pdf), no further action was taken with regard to the use of smart cards.

30

Article 28 of the Directive foresees the possibility of bringing forward a legislative proposal on a

certification system for other crew members performing safety-critical tasks. However, this option was

discarded following the report produced by ERA in 2009.

15

whether the introduction of a single, common operational language (like in aviation)

would be beneficial.

Limitations and robustness of findings

The evaluation faced some difficulties in producing robust quantitative comparisons with

the data from 2004. This is mainly due to the lack of comparable data on the impacts of

the Directive and is a limitation to the delivery of robust quantitative conclusions.

The first problem relates to the fact that no systematic data collection on the certification

of train drivers takes place in the Member States. There is data on employment available

both at national and European level, which, however, it is mostly limited to generally

describing the employment in the rail sector without much detail.

Secondly, there is no data available on the costs and benefits linked to the

implementation of the Directive, which would allow a comparison with the costs and

benefits estimated in the impact assessment accompanying the proposal for the Directive.

The data in the ERA report has 31 March 2013 as reference date and presents the state of

play in terms of number of train drivers, licences/certificates issued, fees, training centres

etc. However, the evidence gathered by ERA is incomplete, as it does not cover all

Member States. Moreover, given the phasing-in schedule of the Directive, the ERA

report is a snapshot at an early moment, when across Member States in average 11% of

train drivers had a European driving licence. Another limitation of the ERA report

concerns its scope, as it did not cover all provisions of the Directive but was focused on

the following elements: procedures for issuing licences and certificates, accreditation of

training centres and examiners, quality systems, mutual recognition of certificates,

adequacy of training requirements specified in Annex IV, V and VI, and the inter-

connection of registers and mobility in the employment market.

Furthermore, the data collected by ERA from the Member States after 2013 in the

context of cooperation activities under Article 35 of the Directive has gaps and does not

offer a complete picture of the implementation of the Directive.

The stakeholders in the public consultation were asked to give not only qualitative but

also quantitative assessments of the effects of the Directive. The latter has proven very

difficult and some of the respondents draw attention to the fact that no conclusive

estimates on the sector cost were available and/or they did not have access to concrete

information and statistics. In some cases, the costs incurred were not identified, while in

other cases an estimate was difficult because older requirements and procedures have

been updated and/or changed through the Directive.

6. ANALYSIS AND ANSWERS TO THE EVALUATION QUESTIONS

The evaluation of the Directive was based on a series of questions, focused on the

Directive's relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, coherence and EU-added value both in a

general way as well as regarding specific provisions of the Directive.

16

6.1 Relevance

6.1.1 Relevance of the operational objectives for addressing the identified problems

Due to the increase in the cross-border operations and the fact that many RUs operate in

several Member States the objective of developing and implementing operational rules

harmonised at European level is still relevant. Operational circumstances differ between

RUs, national networks and even in local situations; under its Safety Management

System (SMS) a RU must ensure that the driver meets the requirements for a specific

situation. It is important that train drivers are interoperable and have among others

knowledge of the different signalling and operational rules, to ensure smooth cross-

border operations and provision of reliable services for passengers and freight, thus

contributing to making rail more attractive and competitive. This means that it is still

relevant to have common specifications for skills for drivers in cross-border operations.

Stakeholders pointed out that flexibility and interoperability in cross-border operations

depends on common European standards for staff carrying out safety-relevant tasks such

as train drivers. These standards should cover both the medical and psychological fitness

as well as the training and examination.

There is a consensus among the stakeholders that overall the Directive solved to some

extent the problem of fragmentation regarding the licences and certificates of train

drivers, by setting a common framework for certification, training and monitoring of

train drivers, which however consists only in a minimum set of requirements.

With regard to the requirement of checking the physical fitness after any occupational

accident or any period of absence following an accident involving persons (Annex II

point 3.1), stakeholders considered that after an accident involving persons, a train driver

would need psychological support rather than a physical check, the latter being often

perceived by the concerned driver as a sanction. This could lead to train drivers not

reporting all relevant incidents.

Moreover, stakeholders consider that increasing the number of psychological

examinations is not efficient particularly in the case of psychiatric issues, where the lack

of exchange of information between doctors and employers due to medical

confidentiality is also risk for safety.

By defining a minimum set of requirements for obtaining the licence, the Directive has

ensured some consistency in the issuing procedure and the requirements for obtaining a

licence. The minimum set of requirements, some of which leaving room for interpretation

and diverging assessments across Member States, contributes to a limited extent to

developing and implementing harmonized rules and common specifications for medical

and psychological examinations, and for regular checks. For example, the public

authorities contributing to the public consultation consider the non-alignment of validity

period of the licence and the intervals for health checks as inconsistent.

The stakeholders, especially RUs, suggested to explore the use of standardised and

interoperable digital tools for simplifying the application for licence and update

procedures in order to reduce the administrative burden and costs for RUs which operate

in more than one Member State. Further, the necessary training for obtaining the licence

involves familiarisation with the rules of operation and signalling that are in force in the

Member State concerned, therefore differences between Member States continue to exist.

17

With regard to the complementary certificate, common requirements for the same rolling

stock and for similar infrastructure would help to simplify the training of the drivers,

even though the rolling stock used by different RUs and in different Member States still

varies. Different interpretations in Member States of the required competences for rolling

stock and infrastructure create obstacles for mutual recognition of certificates, especially

for cross-border services.

Moreover, the stakeholders consider that in the absence of a uniform definition of an

infrastructure registry, the specification of the infrastructure routes on the complementary

certificate is not standardized. Since the end of stakeholder consultation there was

progress with regard to the Register of Infrastructure (RINF), which aims at providing a

general description of the rail networks within EU. ERA set up and manages a

computerised common user interface, which simplifies queries of infrastructure data.

This interface is in production since end of October 2015. As of end May 2018, around

62 % of the total expected data were already imported by the entities in charge of the

RINF implementation at national level.

As provided for in the Technical Specification for Interoperability relating to the

Operation and Traffic management Subsystem of the Rail System (TSI OPE)

31

, the train

drivers shall be provided with a document called the “Route Book”. This document

includes the description of the lines and the associated line-side equipment for the lines

over which they shall operate and relevant for the driving task. The IM shall provide the

RU with at least the information for the Route Book as defined in the Annex to TSI OPE

through RINF. Based on these developments, aligning the specifications on the

infrastructure in the complementary certificate with the information in RINF and Route

Book could provide for more harmonisation of the content of the complementary

certificate.

Basic principles of the certification scheme are closely linked to key elements of the

Directive (EU) 2016/798 on railway safety (recast)

32

such as the definition of the

competent authority, which is the NSA within the meaning of that Directive. The impact

of the changes brought by the Directive (EU) 2016/798, i.e. the new role of ERA in the

safety authorisation, on the definition of the competent authority would have to be

assessed. The same applies to Article 5 of Commission Decision 2011/765/EU on the

recognition by the Member States of the training centres belonging to a RU or an IM.

They are recognised in combination with the safety certification or safety authorisation

process in accordance with Safety Directive. This Article might have to be revised, given

the change in responsibilities regarding the issuance of safety certificates (i.e. ERA

instead of the NSAs).

6.1.2 Relevance of the requirements as instruments to achieve the objectives

The requirements concerning the licence and the complementary certificate were, to a

limited extent, the right instrument to achieve the objectives.

31

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/773 of 16 May 2019 on the technical specification

for interoperability relating to the operation and traffic management subsystem of the rail system within

the European Union and repealing Decision, OJ L 139I , 27.5.2019, p. 5–88

32

OJ L 138, 26.5.2016, p. 102

18

The framework provided by the Directive seems to be the right one to achieve common

minimum requirements, although the skills required for the licence are currently a small

part of the skills that a driver must have to drive a train.

One of the requirements for the licence is the successful completion of nine years of

primary and secondary education (Article 11.1). Neither is the relevance of this

requirement clear for the competency of the train driver nor is any standard of education

required. Further, public authorities consider that the provisions concerning education are

difficult to implement due to differences in the educational systems.

Furthermore, the conditions of psychological assessments, costs and contents of general

competence trainings are not enough harmonised and concretised to fully meet the

objectives on common specifications for psychological profiles and minimum

requirements for medical examination and regular checks.

Concerning the requirements for the complementary certificate, even though the rolling

stock used by different Rail Undertakings and in different countries still varies very

much, common requirements for complementary certificates for the same rolling stock

and similar infrastructure would help to simplify the training of the train drivers. There is

a lack of specific certificate requirements for train drivers in cross-border operations.

Moreover, as pointed out also by the train drivers participating in the consultation, the

duration of training vary across Member States between 24 and over 600 hours; this

raises questions about the proportionality of the training.

The Rail Undertakings commented that the general level B1 language requirements are

too high, difficult and expensive to implement. Another stakeholder considered level B1

as too high and suggested B1 level for listening and speaking and a lower level, A2, for

writing. In its report on rail freight transport in the EU

33

the European Court of Auditors

recommends that the European Commission and the Member States should also assess

the possibility of progressively simplifying language requirements for locomotive drivers

to make medium- and long-distance rail freight traffic in the EU easier and more

competitive.

Including more competences from the certificate in the licence would enhance the

flexibility of train drivers to operate in different Member States. Moreover, the train

drivers should have the possibility to renew their licences in case of long-term

unemployment and to obtain languages certification at their own initiative.

6.1.3 Conclusions

The operational objectives of the Directive continue to be relevant. Overall, the Directive

led to a certain degree of harmonisation and consistency in the requirements for licences

and complementary certificates by setting minimum requirements. Therefore, the

Directive solved to some extent the problem of fragmentation regarding the licences and

certificates of train drivers, by setting a common framework for certification, training and

monitoring of train drivers.

The objective of developing and implementing operational rules harmonised at European

level is still relevant, for providing flexibility and interoperability in cross-border

33

https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/SR16_08/SR_RAIL_FREIGHT_EN.pdf

19

operations, and hence overcoming operational difficulties in cross-border services. The

latter remains relevant against the background of increase in cross-border operations and

the number of RUs active in more than one Member State, which requires more and more

interoperable train drivers. The requirements concerning the licence and the

complementary certificate are, to a limited extent, the right instrument to achieve the

objectives, due to the insufficient harmonisation and concretisation of requirements.

6.2 Effectiveness

The analysis of effectiveness defines whether and to what extent the intervention has

brought the envisaged effects with reference to the stated objectives.

6.2.1 Facilitating the mobility of train drivers between Member States

Through the mutual recognition of licenses and certificates, the Directive makes it easier

for train drivers to work in different Member States. However, even though the basic

requirements are the same, the framework set by the Directive is too wide, the aim of

some requirements is not clear, and the role of the various actors in the certification

process is not described precisely enough. Hence, the measures taken by the Member

States could lead not to harmonisation but on the contrary to fragmentation due to

divergent implementing measures, which could impact the mobility of train drivers

between different Member States.

Some stakeholders perceive the absence of a single document combining licence and

certificate valid in the EU as an obstacle to the mobility of train drivers between Member

States. A first step in that direction would be simplifying the training of train drivers by

developing common requirements for the complementary certificates for the same rolling

stock and similar infrastructure.

6.2.2 Facilitating the mobility of train drivers between Rail Undertakings

The Directive contributed to facilitating the move of train drivers from one employer to

another. The harmonised definition of competences, the standardised copy of the

complementary certificate, all this combined with the harmonised licence make it easier

for the new employer to assess the competence of a train driver, who has obtained

competences in another company. In this respect, it is highly beneficial that the former

employer must release a certified copy of the former complementary certificate including

detailed information about acquired knowledge and working experience. Furthermore,

the fact that the licence is personal property of the train driver and not of the employer

seems to facilitate the passage from one company to another.

The mobility of train drivers between RUs operating in the same Member State is

certainly facilitated by the Directive, for example because both former and new employer

operate on the same network. However, as also pointed out by stakeholders, it is not

necessarily the licence influencing the mobility of drivers between companies in the

same country, but the mutual recognition of complementary certificates.

Unclear provisions, leaving room for interpretation, have an impact on the mobility of

train drivers between RUs; for example Article 24 of the Directive requests Member

States to ensure that RUs or IMs do not unduly benefit of the investments made by other

companies in training the drivers. While this principle is understandable, there is no

20

guidance in the Directive on how to compensate in practice the source company for the

training given to the train driver for obtaining the certificate, in case the respective train

driver changes the company. This leads to various arrangements in place in the Member

States, from provisions rooted in national law (such as labour law) to leaving it up to

employers to deal with it. The latter concretises in clauses included in the work contract

and stipulating for example that the train driver has to work for a certain number of years

for that very company, for the training costs to be covered. In case of leaving the

company before the end of this compulsory period, then the driver has to make a

termination pay. This is a constraint for mobility because train drivers who wish to

change the employer but cannot afford the termination pay, have to wait for the end of

the compulsory period to do so.

6.2.3 Contribution to maintain (or even raise) the safety level of the railway system

The Directive contributes to achieving the safety objective. By establishing minimum

common requirements for certification of train drivers, the Directive raised awareness of

industry and NSAs concerning the importance of staff competences in the field of safety.

Due to the Directive, best practices of some Member States have been extended to other

Member States; at the same time, there is more clarity on the responsibilities of the

various actors involved in the certification.

Thanks to a consistent approach on physical fitness and competence standards, the

Directive helps maintain the safety level.

However, it is difficult to estimate the direct contribution of the Directive to maintaining

(or even raising) the safety level of the railway system, because the safety level was

already very high when the Directive entered into force. One Member State reports that

the safety-related objectives of the Directive were already fulfilled at national level when

the Directive entered into force. Along the same lines, a RU comments that the minimum

requirements set out in the Directive were already met or exceeded in most of the

countries they operated in.

The Directive does not include any provisions on the duration of training for the

certificate and the number of training hours varies across Member States (between 24 and

over 600 hours); this could lead to questions about the quality of the training and

lowering the standards in order to reduce the costs, and hence the possible impact on

safety.

The stakeholders also draw the attention to the fact that requirements and procedures

alone - including those brought by the Directive - are not themselves sufficient to ensure

the operational safety, they have to be properly implemented and enforced.

It is necessary to better reconcile the requirements for safety in the rail sector with the

need for rail to be attractive and competitive. Overall, the language requirements are

perceived as not being very effective in ensuring a high level of safety while allowing

efficient operation of the rail network. This is particularly true in case of disruptions on

the railway network of a Member State requiring the use of deviation routes through

neighbouring Member States. In those cases, train drivers with specific language skills

are sought at short notice to drive on deviation routes, hence ensuring the continuity of

operations, as it was the case when, due to an incident in Rastatt, the Karlsruhe-Basel line

21

was closed for all traffic for a period of seven weeks in August-September 2018

34

.

Although diversion routes were available, the capacity on these routes was limited and

interoperability proved to be a major hurdle. Many locomotives were not equipped to

operate on the railway network in neighbouring countries and train drivers with the

language and route knowledge to operate a train in another country were not sufficiently

available.

Commission Regulation (EU) 2019/554 of 5 April 2019 amends the Directive with regard

to language requirements and creates the legal basis for exploring alternative options to

the current language requirements allowing for greater flexibility while ensuring at least

an equivalent level of safety with the current requirements. Those options could consist in

more targeted language requirements (i.e. with focus on rail specific terminology), or to a

lower general language level combined with alternative means to support effective

communication. They should ensure an active and effective communication in routine,

degraded and emergency situations.

The Directive does not foresee the possibility of introducing a single operational

language; however, this issue was addressed in various discussions with stakeholders and

eventually in the public consultation. Fifty-one percent of the respondents considered the

introduction of a single, common operational language at least to some extent beneficial

especially for cross-border traffic, as it could simplify the language training and increase

safety, but at the same time, be a costly requirement.

6.2.4 More efficient management of interoperable train drivers

Before entering into force of the Directive, the Member States had to conclude bilateral

agreements for the recognition of licences. The stakeholders consider that the EU-wide

recognition of the licence has a positive impact on assigning train drivers to operations in

various Member States; however, this impact is limited because only a minimum of basic

skills and qualifications is requested for the licence; most specific skills and competences

are required for the complementary certificate.

Further to the common requirements for certificates, they have a limited impact on EU-

wide interoperability of train drivers since an important part covers the safety and

operational rules, which are national and/or depend on the IMs.

The lack of EU-wide training programmes makes it difficult for RUs operating cross-

border services to issue certificates that allow driving in another country, hence limiting

the impact of the certification scheme on the assigning train drivers to operations in

different Member States. Different interpretations in Member States of the required

competences for rolling stock and infrastructure create obstacles for mutual recognition

of certificates, especially for cross-border services.

34

The Karlsruhe-Basel railway line is part of the important north-south corridor connecting the ports of

Rotterdam, Hamburg and Antwerp with Switzerland and Italy. The Rastatt incident and ramifications

led to big financial losses and reputational damage for the rail freight industry. Economic damage was

estimated to be more than two billion Euros according to HTC Hanseatic Transport Consultancy, the

European Rail Freight Association (ERFA), the European Rail Network (NEE) and the International

Union for Combined Rail-Road Transport (UIRR). Moreover, rail transport lost an approximate one per

cent of its market share in Switzerland.

22

For safety reasons, it is essential that the train drivers are able to communicate actively

and effectively with the IMs in routine, adverse and emergency situations. However, the

language requirements are perceived as an obstacle to achieving EU-wide interoperability

of train drivers as well as for simplifying their training, since they create considerable

extra costs for RUs, and limit the attractiveness of cross-border operations.

With regard to monitoring of train drivers, the provisions of the Directive are not always

clear when it is about the allocation of responsibilities/tasks to the actors. One public

sector entity reports examples where it was unclear if it was the license or the certificate

to be withdrawn and who (i.e. the competent authority or the employer) was supposed to

act. Moreover, the shared responsibility between the competent authority and the

RUs/IMs can lead to difficulties (for example in case of periodic medical checks). The

public sector entities consider for example that having a register for licences and another

one for certificates makes monitoring of train drivers is more difficult. Further, Article 17

of the Directive requires that the RU shall inform the competent authority about cessation

of employment. For the RUs, the reason behind this obligation is not clear, as there is no

obligation to report the start of the work for a RU to the competent authority and there is

no process triggered by reporting to the competent authority.

6.2.5 Form of intervention

As regards the adequacy of the form of intervention, in principle the idea of a Directive

was good, giving the Member States the freedom to take the measures they consider

appropriate to achieve the goals. However, the Directive sets a too wide frame for

example by not setting any quantitative targets, not spelling out clearly the role of various

actors in the process or the clear purpose of requirements (see also section on

implementation). Hence the measures taken by the Member States could lead not to

harmonisation but on the contrary to fragmentation due to divergent implementing

measures, which could create problems for interoperability of train drivers.

More prescriptive and detailed provisions would have been beneficial for implementing

common minimum requirements for certification of train drivers.

Accompanying the Directive by guidelines for implementation would have been

beneficial for a consistent interpretation of the provisions of the Directive and hence,

avoid different interpretations and applications of the provisions.

6.2.6 Conclusions

The Directive was effective in contributing to enhancing and facilitating the mobility of

the train drivers as well as easing, for the employer, the assignment of train drivers to

operations in various Member States. However, there are some weaknesses, which seem

to be mainly linked with differences between Member States in the implementation of the

Directive and with setting national standards. The Directive set consistent requirements

for operation in different Member States; however, as they are minimum requirements,

national standards go sometimes further than the Directive.

The EU-wide validity of the licence has a positive impact on assigning train drivers to

operations in various Member States. However, this impact is limited because only a

minimum of the level of skills and qualifications is requested for the licence; most skills

are required for the complementary certificate (valid only on specific

infrastructure/rolling stock). The certificate part of the Directive has a limited impact on

23

EU-wide interoperability of train drivers since an important part covers the safety and

operational rules, which are national and/or depend on the Infrastructure Manager.

The set-up of the Directive, lacking details, being not specific enough and the absence of

interpretative guidelines, led to differences in interpretation, understanding and

implementation, which had an impact on interoperability as well as on the achievement of

the objectives.

6.3 Efficiency

The efficiency of the Directive refers to achieving its effects with a reasonable use of

resources and whether the same results could have been achieved with fewer resources.

6.3.1 Expected impacts of the Directive

According to the impact assessment of the Directive, maintaining the status quo (i.e. the

patchwork of national certification schemes) would have entailed a loss of

Euro 66.5 million for the EU-25, while the benefits of the Directive were estimated at

Euro 226 million and the costs at Euro 169 million

35

.

6.3.2 Costs incurred due to complying with the Directive

The Directive certainly provided a framework for consistent requirements for train driver

licences and certificates but the details and processes have created an additional layer of

bureaucracy and burden falling upon several entities (NSAs, employers, and drivers) and

increased the costs for RUs.

With regard to the types and levels of costs (including fees and charges) incurred due to

complying with the requirements of the Directive, several categories of costs were

identified, based on the examples given by the a few participants to the public

consultation.

The various fees vary across Member States, for example, the fee for issuing the licence

varies from 0 to 224 Euro. The fees for issuing a duplicate licence are lower than for the

original licence. Some stakeholders who contributed to the public consultation consider

that a harmonisation of the procedure for obtaining the licence would also require

harmonising the fees for obtaining a licence.

To give another example, in a Member State, the fee for examination of a train driver is

800 Euro, while for the certification of an examiner the fee is 1000 Euro for the first year

and 500 Euro per subsequent year. In some Member States, the fees are reduced for

operators of historical trains.

35

These estimations were based on the following assumptions:

approximately 200.000 train drivers in EU-25, out of which at most 5% (i.e. 10.000 drivers)

concerned by the first phase of implementation (i.e. cross-border services);

an annual increase of 5% in the number of train drivers, following increases in cross-border traffic,

i.e. 500 drivers annually;

an annual staff turnover of 5%, i.e. 500 drivers/year.

This led to the conclusion that there would be 1.000 drivers to be certified each year in phase 1 (cross-

border) but 10 000 in phase 2 (all other drivers).

24

The fee for recognition of training centres also varies from one Member State to another.

For the various fees, there are different payment schemes in place, e.g. the fee can be

paid for a period of 5 years, per hour or the fee for renewal could be lower than the fee

paid the first time.

Below there are some categories of costs, identified by NSAs:

costs linked to the registers for licences and complementary certificates (including

human resources). One NSA estimated that the management of the National Register

for Licences, which has to be set up according to the Directive, required the

equivalent of a full time post. However, the costs setting the NRL could be

understood as one-off costs, given that the registers were set up once.

development costs for the design, testing and material for the licences. One NSA

estimated these costs at about 12.710 Euro.

costs linked to submission of applications for licences. One NSA considers that these

costs increased due to the Directive because the application file includes more

documents to be assessed than it was the case before the Directive entered into force.

costs for the issuance of the licence and the migration to licences based on the

Directive. With regard to the latter, one NSA estimated that it required the equivalent

of two full time posts until 13 January 2017.costs for printing and sending out the

licences. One NSA estimated the costs at about 26.608 Euro for 4.700 licences issued

costs for the appointment of examiners (both in terms of administrative procedure

and human resources).

According to a NSA, the Directive increased the workload that was not reflected in an

increase in the number of staff.

Another example shows some of the categories of costs incurred to RUs are linked to:

Application, issuing, and updating of licences and complementary certificates. An RU

consider that he costs for issuing and updating the certificate would be lower, if the

certificate would be displayed on mobile devices such as tablets.

Change of existing licences;

Production of complementary certificates (labour and material costs);

More frequent examinations of train drivers (examination costs and more difficult

management of drivers / replacement costs);

Oversight of training facilities, recognition and renewal of accredited/recognised

examiners;

Training (increased costs for language training after introduction of level B1).

An RU estimated the costs for a period of 10 years as follows: Euro 4,8 million for the

licence, Euro 0,5 million Euro for the IT development of the register for complementary

certificates, Euro 16 million for the periodic psychological assessment, and

Euro 42 million for the certificate global process. However, the costs for the IT

development of the register for complementary certificates could be understood as one-

off costs, given that the registers were set up once.

The stakeholders also report on the high administrative burden related to the

administrative procedures to follow for the issuance and update of the certificates, which

25

can be very complex. In one Member State, the introduction of the complementary

certificate created an additional administrative burden for all domestic RUs.

The possibility of gradually phasing-in the harmonised certification has resulted in

temporary extra administrative burden for some Rail Undertakings with cross-border

operations, since the implementation date for the harmonised certification documents

varied across the Member States. In addition, there are some other tasks causing a high

administrative burden to RUs such as the requirement to register the date of the last

examination in the complementary certificate, or even to both NSAs and RUs. An

example for the latter is the NSA having to register periodic health checks, while the RU

must also keep track of this information, which is double administration and creates

confusion regarding responsibilities.

Given that the evidence is only anecdotal, it is difficult to quantify the sector costs

incurred due to compliance with the Directive, and hence to make a reality check of the

expected impacts presented in the impact assessment of the Directive. In addition, it is

difficult to make an estimation of the impact of putting in place the new certification

scheme also because the Directive did not fill a vacuum at national level; there were

already national certification schemes in place. This implies that older requirements and

procedures have been updated and/or changed and hence some of the costs incurred are

one-off costs due to adaptation of national certification schemes to the requirements of

the Directive.

6.3.3 Benefits achieved by complying with the Directive

The benefits of complying with the Directive were not apparent to all categories of

stakeholders. For the Public Authorities, the submission process for the licence is more

clear and simple since the Directive entered into force. In addition, it is easier to ensure

that the train drivers meet all requirements for the licence. Moreover, the NSAs have now

more complete and on-line information about each train driver on the infrastructure and

rolling stock. Previously, when this information was needed, they had to send a request to

the respective RU.

One NSA reported that being responsible for the maintenance of NRL helps to ensure a

higher level of control.

For the cross-border operating RUs it is beneficial that the Directive set up a common

framework to be followed also by their counterparts, as well as that now they have to

issue one single complementary certificate valid in the EU as opposed to one for each

Member State, which was the case before the Directive entered into force.

Further, due to its specificities and limitations, the ERA report does not include any

figures on the benefits achieved by complying with the Directive.

6.3.4 Proportionality between costs and benefits

The costs incurred by complying with the Directive were not perceived by the

stakeholders as being proportional with the benefits achieved. This could be due to the

lack of awareness of the stakeholders with regard to the real costs incurred due to

complying with the Directive (and hence considering them too high based on no