i

The perceptions of educators towards inclusive

education in a sample of government primary

schools

Cara Blackie

A research report submitted in partial fulfilment of the

requirements for the degree of Master of Education (Educational

Psychology) in the faculty of Humanities, University of the

Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 2010

brought to you by COREView metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk

provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE

i

DECLARATION

I, Cara Blackie, hereby declare that this research report is my own work. It is being submitted for

the Degree of Masters of Education (Educational Psychology) at the University of the

Witwatersrand. It has not been submitted for any other degree or examination at any other

university.

_______________________

Cara Blackie

_______________________

Date

ii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my sincere thanks to:

Dr Zaytoonisha Amod, my supervisor for her assistance and understanding throughout this

research process. Her guidance and support were invaluable in extending my understanding

of and skills in research and writing.

The principals at the primary schools for allowing me to use their educators‟ precious time.

To all the educators who participated within this study, thank you for your time, knowledge

and views on inclusive education.

Mrs Nicky Israel, for offering her assistance and statistical knowledge throughout this

research process.

My parents for their unwavering support and encouragement throughout this research

process.

My fellow colleagues who were there to offer support and shoulder to lean on during the

difficult times. I will be forever grateful for the friendship and support you offered me

throughout this year.

My friends and family who stuck with me this year and always offered words of support and

encouragement.

iii

ABSTRACT

This study examined the perceptions of educators towards inclusive education. The educators‟

perceptions of the barriers to learning, the skills required in an inclusive environment, the

involvement of support in inclusive education and the training programmes required were all

examined. Education White Paper 6 was introduced in 2001 by the South African Department of

Education stipulating inclusive education policies and a long term goal of successful

implementation of inclusive education country wide. The sample of this study consisted of forty

educators from six government primary schools in the Johannesburg region. The questionnaire was

created to look at educators perceptions of all aspects of inclusive education within their school.

The results demonstrated an equal amount of positive and negative perceptions towards the

implementation of inclusive education. The educators of this study reported perceiving themselves

to be inadequately trained to assume the responsibilities of inclusive education. The perceived

prevalent barriers to learning in the classroom were emotional and cognitive barriers to learning.

Due to South Africa‟s diverse population language was also seen to be a prominent barrier to

learning within these schools. Educators reported the need for parental support for the successful

implementation of inclusive education; however, the reality of these educators is that parental

support is minimal and often nonexistent. Finally the limitations of the study are discussed and

suggestions for further research made.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page No.

Declaration i

Acknowledgements ii

Abstract iii

Table of contents iv

List of tables and figures viii

Chapter 1: Introduction to the study and literature review

1.1.Introduction 1

1.2.Rationale for the study 3

1.3.Theoretical background 4

1.4.International perspective on inclusive education 5

1.5.Inclusive education policy in South Africa 8

1.5.1. Contextual factors to consider in the implementation

of inclusive education 11

1.5.2. Conceptualisation of barriers to learning and development 12

Chapter 2: Educators perceptions of inclusive education

2. Factors influencing educators‟ perceptions of inclusive education 17

2.1. Educator attitudes towards inclusive education 18

2.2. Educator stress 19

2.3. Curriculum related issues 20

2.4. Training issues 21

2.5. Support structures and systems 24

v

2.6. Educators personal characteristics 26

2.7. Class size 28

2.8. Conclusion 28

Chapter 3: Methodology

3.1. Aims and Research Questions 30

3.2. Context of the study 30

3.3. Research Design 31

3.4. Sampling 32

3.5. Instruments 32

3.6. Procedure 35

3.7. Data Analysis 36

3.8. Ethical considerations 38

Chapter 4: Results

4.1. Educators‟ views and understanding of inclusive education

within a sample of government primary schools 39

4.1.1. Educators understanding of inclusive education 39

4.1.2. Educators perceptions towards inclusive education 41

4.2. Educators perception of barriers to learning within the classroom 47

4.2.1. Barriers to learning in the classroom 47

4.3. The skills that educators think they need in order to implement

inclusive education 51

4.4. Support structures used by educators to assist them in the

implementation of inclusive education 55

vi

4.5. Educators‟ participation in inclusive education training programmes

and their perceptions of these programmes 56

4.6. Other inclusive education training programmes that educators would

like to participate in 58

4.7. The relationship between the number of years teaching experience

and the perceptions of educators towards inclusive education 59

Chapter 5: Discussion of results

5.1. Research Question 1: What are the educators‟ views and

understanding of inclusive education within a sample

of government primary schools? 60

5.2. Research Question 2: What do educators perceive to be

barriers to learning within the classroom? 64

5.3. Research Question 3: What are the skills educators think

they need in order to implement inclusive education? 69

5.4. Research Question 4: What are the support structures

educators use to assist them in the implementation of

inclusive education? 72

5.5. Research Question 5: What are the training programmes

educators have participated in involving inclusive education

and their perceptions of these training programmes? 73

5.6. Research Question 6: What are other training programmes

educators would like to assist them in implementing

inclusive education? 74

5.7. Research Question 7: Is there a relationship between the number

of years teaching experience and the perceptions of educators

towards inclusive education? 75

vii

5.8. Limitations of the study 75

5.9. Directions for future research 77

5.10. Summary and Conclusion 78

REFERENCE LIST 80

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Participant Information Sheet 87

Appendix B: Inclusive Education Questionnaire 89

Appendix C: Principal Information Sheet 95

Appendix D: Principal Consent Form 97

Appendix E: School Survey Checklist 98

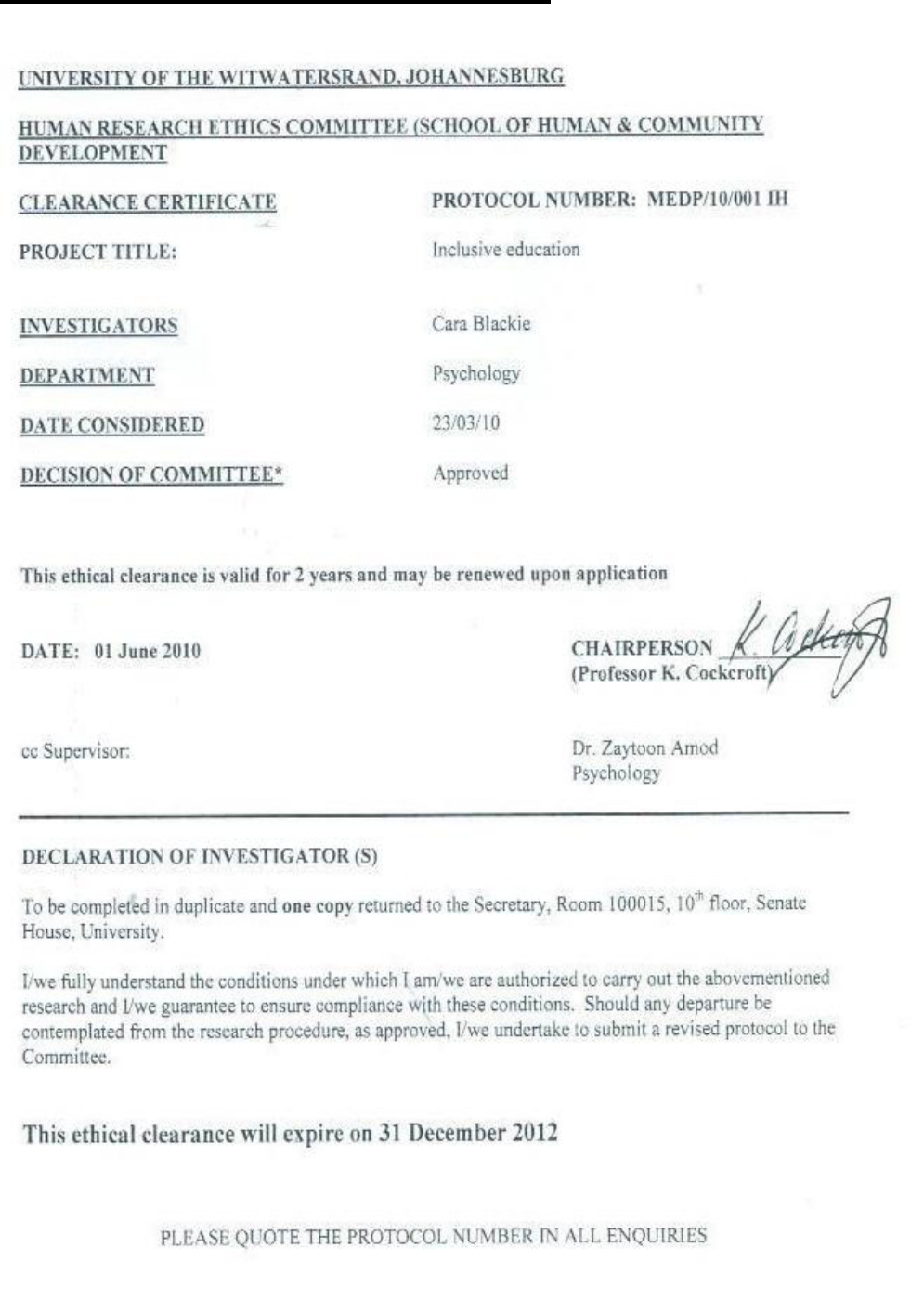

Appendix F: Ethical Clearance Certificate 99

Appendix G: Gauteng Department of Education Certificate 100

viii

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

Table 4.1: Statistical results of the T-test indicating no significant difference between the two

variables

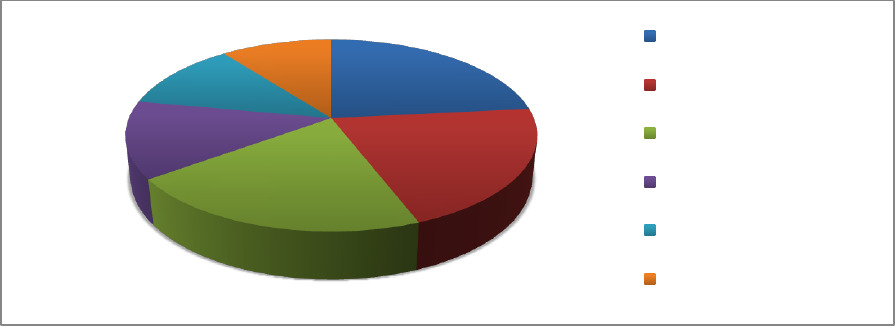

Figure 4.1: The distribution of participants‟ perceptions towards inclusive education

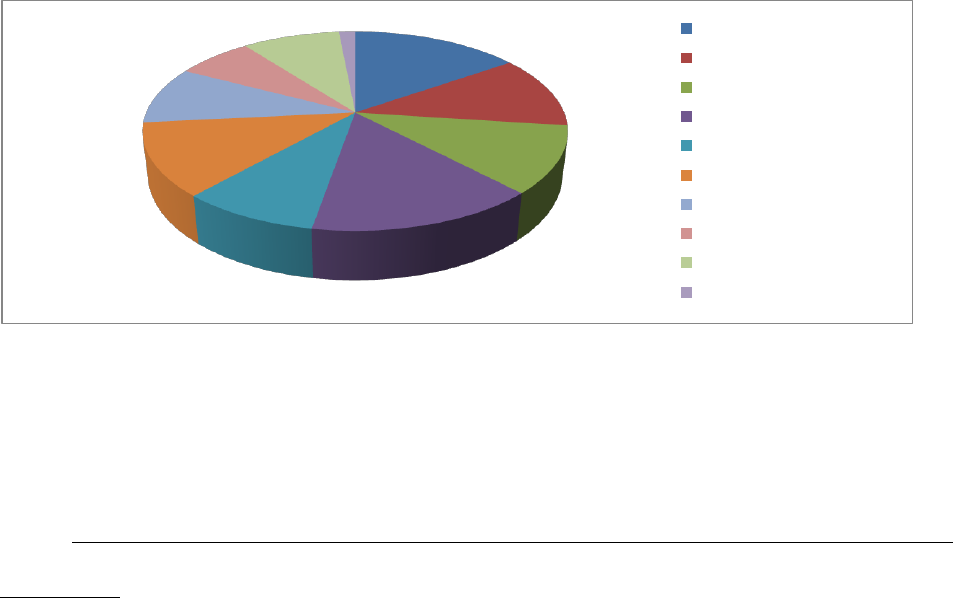

Figure 4.2: The distribution of participants‟ perceptions of the barriers to learning within the

classroom

Figure 4.3: The distribution of participants‟ perceptions of the skills required in an inclusive

classroom

Figure 4.4: The distribution of perceived supportive support structures present within the school

system

1

Chapter 1: Introduction to the study and literature review

1.1.Introduction

Philosophies involving inclusive education have changed dramatically over the past two decades

(Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007). In the past, segregation of special education needs students seemed

an easy solution, however, it denied those students the right to develop their personality in a social

and school environment (Koutrouba, Vamvakari & Steliou, 2006). Special education needs is

described to include the view that learning and behaviour problems are the reciprocal product of

individual and environmental interaction (Landsberg, 2005). Inclusive education should not just be

about addressing a marginal part of the education system, it should rather constitute a framework

that all educational development systems should follow (Booth, 1999).

Inclusive education is aimed at increasing the participation of students in the curricula, cultures

and communities of governmental educational systems (Booth, 1999; Landsberg, 2005; Gross,

1996). Inclusion should involve creating an environment that allows all students to feel supported

emotionally, while being given the appropriate accommodations in order to learn. Most

importantly, those students need to be respected and appreciated for all their personal differences

(Hammond & Ingalls, 2003; Gaad, 2004). Avramidis and Norwich (2002) proposed that

integration can take on three forms. Locational integration, which allows special needs students to

attend mainstream schools. Social integration, which is the integration of special needs students

with mainstream peers. Finally functional integration, which is the participation of students with

special education needs within the learning activities that occur in the classroom (Avramidis &

Norwich, 2002). Engelbrecht (2006) states that inclusion is culturally determined and depends on

the political values and processes of the country for it to become effective. Even taking this into

consideration, it is extremely important to realise that there is not just one perspective on inclusion

within a single country or even within a specific school (Engelbrecht, 2006).

2

In 2001, the South African Government promulgated Education White Paper 6: Building an

Inclusive Education and Training System. This was intended to address the difficulties

surrounding the inclusion of students with barriers to learning within the mainstream school

(Engelbrecht, 2006). The only way to really determine if this policy has been effective is through

the understanding and information gained from the one group of individuals who has constant

contact with students with barriers to learning, namely the educators. This study is intended to

focus on the perceptions of educators towards inclusive education. As Landsberg (2005) states

perceptions are assumptions, beliefs and attitudes that are directly translated into actions and

teaching practices and can be seen to inform decision making. The future success of inclusion

policies in any country will ultimately depend on educators‟ perceptions towards inclusive

education (Hammond et al., 2003; Burke & Sutherland, 2004). Educators have the ability to affect

their students‟ emotional, social and intellectual development (Parasuram, 2006). Educators‟

perceptions, beliefs and attitudes influence their acceptance of the policy of inclusion and their

commitment to implementing it (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Landsberg, 2005).

To fully understand the results of this study it is fundamental to understand the concept of a

perception. Perceptions are the means by which we sense the world we live in and so it is the basis

of our basic human functioning (Wylde, 2007). The way in which all individuals interpret the

world is controlled by our unique perceptions (Wylde, 2007). In this research, perceptions will

involve all aspects of how one senses the world, such as a person‟s personal attitudes, beliefs,

behaviour and views.

When reviewing previous research done in this area, it is vital to see the importance of researching

educators‟ perceptions towards inclusive education as perceptions have the ability to guide

behaviour, attitudes and beliefs (Parasuram, 2006; Gaad, 2004). Hammond et al. (2003)

highlighted the connection between educators‟ attitudes and the implementation of inclusion;

3

however, they state that there is very little research that exists on educators‟ attitudes and namely

perceptions towards inclusive education. This study aims to understand the perceptions of

educators towards inclusive education which would assist in informing inclusive educational

practices in South African schools. Restructuring of mainstream schooling is vital in order for all

schools to be able to accommodate every child, irrespective of their specific special learning needs

(Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Department of Education, 2001).

1.2.Rationale for study

The South African Education Department implemented Education White Paper 6 (Department of

Education, 2001) to address the rights of all South Africans regardless of race, gender, sexual

orientation, disability, religion, disease, culture or language to receive basic education and access

to an education institution (Engelbrecht, 2006; Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001). It aimed at providing

training programmes in inclusive educational policies and strategies in order for educators to

successfully implement inclusive education within the school (Department of Education, 2001).

There is limited research in the field of inclusive education in South Africa (Schimper, 2004;

Wylde, 2007; Hays, 2009; Gordon, 2000; Christie, 1998). Furthermore, only a few studies have

been conducted on educators‟ attitudes towards inclusive education in this country. These studies

have mainly focussed on research samples from independent schools (Wylde, 2007; Schimper,

2004). This current study aims to add insight into educators‟ perceptions towards inclusion using a

sample of government schools within the Gauteng area. The School Survey Checklist (Appendix

C) could also contribute to future research which looks at the link between resources of a school

and educators‟ perceptions towards inclusive education.

South African research has stressed the importance for educators to attend training programmes

involved in inclusive education practices (Amod, 2004; Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007). The

4

Department of Education (2001) stated the importance of training educators in order for inclusive

education to become successful however, little to no research has been conducted in the last few

years to assess the impact of these training programmes that have been implemented in South

Africa. Research has not focused on educators‟ perceptions on the effectiveness of training

programmes implemented within South Africa. The current study provides data on the training that

has occurred within a sample of schools in Gauteng, and this could lead to further research being

conducted within this area. It is extremely important for further research to be conducted on

training programmes as they have a direct influence on educators who are the implementers of

inclusive education.

Education White Paper 6 is intended to focus on recognising the needs of all learners and

overcoming barriers that may hinder optimal learning (Department of Education, 2001). There are

many factors that affect and create difficulties in fully implementing inclusive education policies

within the South African context. This study aims to explore the factors that educators perceive to

influence their ability to implement inclusive education policies. This is vital as this policy has a

20 year plan and this year it is almost mid-way through the implementation of inclusive education

as outlined in Education White Paper 6 (Department of Education, 2001).

1.3.Theoretical background

Inclusive education means different things to different individuals in different contexts, however

there are some commonalities. These being a commitment to building a more just society, a

commitment to building a more equitable education system and a conviction that the extension of

the responsiveness of mainstream schools to students‟ diverse barriers to learning can offer a

means of translating these commitments into a reality (Engelbrecht, Green, Swart &

Muthukrishna, 2001). Inclusive education is meant to not only offer individual students

5

educational equality, but also social, economic and political equality regardless of that student‟s

intelligence, disability, gender, race, ethnicity and social background (Shongwe, 2005).

As this study focuses on educators‟ perceptions towards inclusive education it is necessary to look

at those perceptions that they may bring into the classroom. According to Brofenbrenner‟s theory,

people create perceptions based on reality as well as subjective experiences (Hays, 2009). This

allows this current study to gain an understanding of the reality of educators‟ reality of teaching

students with barriers to learning while taking into account their own subjective accounts. In

terms of the barriers to learning that will be discussed in this study it is vital to define what

„Barriers to learning‟ involve. „Barriers to learning‟ involve both intrinsic and extrinsic factors that

can either prevent optimal learning or that can lessen the extent to which learners can benefit from

education (Amod, 2003). „Barriers to learning‟ are seen to result from pervasive social conditions

and attitudes, inappropriate education policies, unhelpful family or school conditions, or a

classroom situation that does not match the learning needs of a particular student (Booth, 1999;

Engelbrecht, Green, Naicker & Engelbrecht, 1999). In the past „disability‟ was one of the many

factors that caused segregation within schools. Disability is referred to as an affliction from which

a minority of individuals may suffer and is often attributed to physical and medical causes,

however, different cultures and countries will have different views on disability (Engelbrecht et

al., 1999).

1.4.International perspective on inclusive education

Inclusive education is not a newly formulated goal; it emerged many years ago on an international

level. Inclusive education has become an important international policy issue of the past decade

(Frederickson, Dunsmuir, Lang & Monsen, 2003). To fully understand inclusive education it is

important to discuss the history of inclusive education found in the literature.

6

International United Nations‟ policies that affirm the right of all children to receive equal

education without discrimination include the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989),

the UN Standard Rules on the Equalisation of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities (1993),

and the UNESCO Salamanca Statement (1994) (Florian, 1998). The most commonly discussed

and fundamental policy was the Salamanca Statement, which will be discussed in more detail. At

the Jomtiem Conference in 1990, the United Nation Organisations adopted the term “education for

all” to dictate the growth and movement that is needed for universal rights in education (Booth,

1999). The most fundamental and revolutionary act towards inclusive education was formulated at

the World Conference on Special Education. This occurred in 1994, where representatives from 92

countries signed the Salamanca Statement, which called on all Governments of those countries to

adopt the principal of inclusive education (Frederickson et al., 2003). This statement requires

governments to enrol all students in regular schools unless there are valid reasons for not doing so

(Frederickson et al., 2003; Smith & Thomas, 2006). This statement describes inclusion as not only

being about reconstructing provision for students with disabilities, but it also implies extending

educational opportunities to a wide range of marginalised groups who may have historically had

little to no access to schooling institutions (Gordon, 2000).

In many countries over the past decade, the inclusion of students with barriers to learning has

become a key government policy objective due to the Special Education Needs and Disability Act

2001 (Smith & Thomas, 2006). Internationally, most legislative frameworks have now included

inclusion into their educational laws. In 1985, the Greek education system started to implement

special classes within the schools, which allowed students with learning difficulties of a moderate

to severe level to be incorporated when parental consent was obtained (Avramidis & Kalyva,

2007). In America in 2001, the „No Child Left Behind Act‟ was formulated to guide educators in

reconstructing the academic content for students with special education needs in line with local

and state-wide grade level standards for students with no special education needs (Cushing, Clark,

7

Carter, & Kennedy, 2005). In 2004, the Individual with Disabilities Act (IDEA), was formed to

make provisions for students with physical disabilities, cognitive difficulties and behavioural

disorders to be taught in mainstream classrooms (Hays, 2009). In the UK, the Special Educational

Needs and Disability Act stated that students need to be educated in a mainstream school unless

parental wishes differ or if fellow students‟ education gets compromised (Frederickson et al.,

2003).

International studies have focussed on the inclusion of particular students within the mainstream

schooling system. These studies particularly focussed on intellectual disabilities as being more

„serious‟ barriers to learning within the classroom (Gaad, 2004). In the United Arab Emirates this

particular barrier to learning namely intellectual disabilities, were dealt with by placing those

particular students into separate classes (Gaad, 2003). Intellectually disabled students were viewed

as having different ability levels and therefore required different teaching methods and curriculum

compared to other students. An international study conducted by Avramidis & Kalyva (2007),

focused on the students‟ „disability‟ as being the predominant barrier to learning. A study on

Greek educators found that educators tended to have more negative attitudes towards students who

were blind, deaf, had mild mental retardation or who had serious behavioural problems (Avramidis

& Kalyva, 2007). In Cyprus, the two major factors that were seen to hinder inclusive education

practices were the lack of infrastructure and a lack of knowledge, skill and confidence amongst

their educators (Hays, 2009; Koutrouba et al., 2006). This resulted in Cyprus changing their

legislation in order to adapt the attitudes of various role-players in the education system into

accepting difference (Hays, 2009).

These countries mentioned above, all follow the Salamanca Statement however; even these

countries that are committed to inclusive education face considerable difficulties, dilemmas and

contradictions that often result in poor implementation (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007). Through

8

assessing international literature in the field of inclusive education, it is interesting to note that

developed countries where resources are not scarce, like the USA, Australia, UK, Cyprus and

Spain to name a few, educators‟ perceptions of the ability to cope was not based on resources.

Educators in these studies reported knowledge, skills and experience as being fundamental aspects

to the implementation of inclusive education (Hays, 2009). International legislation on inclusion

aims at creating multilevel shifts in attitudes of all participants involved in the successful

implementation of inclusive education (Koutrouba et al., 2006).

1.5.Inclusive education policy in South Africa

It is fundamental for this research to take into consideration South Africa‟s past educational

system and the changes that occurred that have resulted in the current revised educational policies.

In 1948, the Apartheid Government come into power and this had an extreme impact on the South

African education system (Engelbrecht, 2006). There were separate education departments in

South Africa, which were all governed by specific legislation. This legislation was based along

racial and disability lines and reinforced segregation and division among the people of South

Africa (Engelbrecht, 2006).

When students were segregated in accordance with their abilities, that policy followed a more

medical model approach of categorisation (Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001; Engelbrecht, 2006; Hays,

2009). This model states that the source of the deficits are within the individual and justifies that

social inequalities are due to biological inequalities (Engelbrecht, 2006; Hays, 2009; Moolla,

2005). This view of diversity within the education system of South Africa legitimized exclusionary

practices while affirming the status and power of professionals. This created the belief among

educators that teaching students with disabilities or barriers to learning is beyond their area of

expertise (Engelbrecht, 2006). This medical model that focused on a deficit view of individuals

still impacts on the current attitudes towards disability and difference that are experienced in South

9

Africa (Engelbrecht, 2006). Only in the 1990‟s with the reconceptualisation of „special needs‟

were disabilities viewed as products of students‟ predispositions and the nature of the environment

they were exposed to (Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001; Moolla, 2005). This was described by the

ecological framework, in which various systems namely the individual, family, school and

organisations interact to result in that individual being at risk for mental health problems (Hays,

2009).

The South African education system has shifted from a policy that favoured one section of the

population and the unequal distribution of resources, to what we have today where equitable state

funding is expected (Booth, 1999; Moolla, 2005). In 1994, due to the changes in the constitution a

democracy evolved that aimed at acknowledging the rights of all previously marginalised

communities and individuals as complete members of society (Engelbrecht, 2006). This also

involves the recognition and celebration of diversity which will be reflected in the attitudes of

communities and institutions (Engelbrecht, 2006; Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001). This was finally

formalised by the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act of 1996, which also included

the Bill of Rights (Engelbrecht, 2006). This act highlighted the rights of all South Africans

regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, disability, religion, culture or language to be able to

receive basic education and access to an education institution (Engelbrecht, 2006; Lomofsky &

Lazarus, 2001). The first move towards acknowledging the complexity of educational needs as

well as the role that social and political processes play in excluding children from education

systems was seen in the Report of the National Committee on Education Support Services

(NCESS) in 1997. This particular report focused on the shift from the predominant spotlight on

students with special needs to a systemic approach that identifies and addresses the barriers to

learning (Engelbrecht, 2006; Hays, 2009). Then in 1999, the Department of Education released the

Green Paper on emerging policy on inclusive education. Responses by the public resulted in the

10

release of Education White Paper 6: Building an Inclusive Education and Training System in 2001

(Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001).

Education White Paper 6 stipulated that inclusive education is based on an ideal of freedom and

equality in which all individuals have the opportunity of becoming competent citizens in an ever

changing and diverse world (Department of Education, 2001; Engelbrecht, 2006; Landsberg, 2005;

Hays, 2009). Inclusive education within South Africa is more of a human rights approach, in

which it transforms the human values of inclusion into the rights of many excluded learners

(Engelbrecht, 2006). Inclusive education aimed at addressing the notion of a democratic society

which is based on human dignity, freedom and equality which is entrenched in the Constitution of

the Republic of South Africa (Engelbrecht, Oswald, Swart & Eloff, 2003). These policies focus on

the inter-related issues of health, social, psychological, academic and vocational development for

special education needs students (Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001). The Department of Education

(2001) stated in Education White Paper 6 that the vision for inclusive education is a long-term

goal. Their short to medium-term goals provided a model for future system wide application. The

short to medium-term goals would be able to provide information on capital, material and human

resource development, funding requirements required to build a fully functional inclusive

education and training system (Department of Education, 2001). Education White Paper 6 aims at

providing support not only for the students that attend mainstream schools, but also for educators

and learning institutions (Hays, 2009). District-based support teams (DBST) which comprise of

staff from provisional and regional head offices as well as from special schools have been

identified as a major resource to help provide training and capacity building for mainstream

schools (Hays, 2009).

11

1.5.1. Contextual factors to consider in the implementation of inclusive education

South Africa‟s Department of Education has struggled to successfully implement inclusive

education due to complex contextual influences (Engelbrecht, 2006). Even now in a post-apartheid

society there are still large disparities between former advantaged schools for white children and

former disadvantaged schools (Engelbrecht, 2006). The former disadvantaged schools, mainly in

rural areas are still affected by poverty and all its manifestations (Amod, 2004; Engelbrecht, 2006;

Department of Education, 2001). According to Engelbrecht (2006) these more disadvantaged

schools still have a lack of resources and efficient administrative systems and suitable educators,

despite the equitable allocation of resources that should have occurred. She adds that while there

has been a shift towards more equitable allocation of resources across all schools the overall output

of the school system is still seen to however, vary considerably. Many schools still seem to lack

resources and the institutional capacity, namely administrative systems and trained educators, and

this places constraints on the effective implementation of new educational policies.

In South Africa, the socio-economic situation can have a severe negative effect on the education

system (Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001). Schools have the ability to determine their own school fees

and depending on the location and community this can range drastically. Disadvantaged schools

generally have a smaller budget that results in less money being set aside for helping educators to

become more efficient in the necessary inclusion policies and training (Lomofsky & Lazarus,

2001). In South African schools, the lack of resources and the overcrowded classrooms are

predominantly due to financial constraints (Engelbrecht et al., 2003). Chronic illnesses are also

barriers to learning for many students in South Africa, the most prevalent and severe illness to

consider is HIV Aids (Booth, 1999). This disease does not just influence the students themselves,

but their parents, community as well as the educators who have to deal with this disease on a day-

to-day basis (Booth, 1999).

12

1.5.2. Conceptualisation of barriers to learning and development

According to the Department of Education (2001), the students that will be most vulnerable to

barriers to learning and exclusion within South Africa are those who have historically been termed

„learners with special needs‟ or, as it is understood, students with disabilities and impairments. The

barriers that will be discussed below can often prevent access to education or can limit

participation within a school. As defined earlier in this chapter, „Barriers to learning‟ are seen to

result from pervasive social conditions and attitudes, inappropriate education policies, unhelpful

family or school conditions and norms, or a classroom situation that does not match the learning

needs of a particular student (Booth, 1999; Engelbrecht et al., 1999). General negative attitudes

from educators, fellow students and the community can result in prejudice on the basis of race,

gender, class, culture, language, religion and disability (Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001). These in turn

can result in barriers to learning when they have been directed at special education needs students

in an inclusive classroom (Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001).

An important barrier to learning that needs to be considered is that of disability. Individuals who

are viewed as being disabled are seen as different from their peers and in need of medical

treatment, as stated in the description of the medical model (Hays, 2009; Engelbrecht et al., 2001).

The disabilities found in schools can include physical, neurological, psycho-neurological and

sensory impairment as well as moderate to mild learning difficulties involved in reading, writing,

maths, and speech and language problems (Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001; Hays, 2009). A study

conducted in 1994 in private schools in Johannesburg found that educators only mentioned the

barriers to learning that were previously referred to as a disability (Schimper, 2004). These mainly

included more physical and mental abnormalities that are more noticeable in the community, for

example Down Syndrome and blindness. Inclusion, however, involves more aspects than just

disability, including cognitive barriers, emotional barriers, physical and environmental barriers as

13

well as external barriers to learning for example factors such as the teacher-pupil ratio, curriculum

and language.

Physical barriers to learning include the physical structure of the school and the physical deficits

students may experience. Some schools may not be able to accept all students with physical and

sensory disabilities due to limitations relating to the physical infrastructure of the school such

ramps for wheel chairs (Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001; Thomas, Walker & Webb, 1998). Avramidis

et al. (2000) reported that sixty five percent of the participants in their study stressed the

importance of the classroom layout and the physical restructuring of the school to accommodate

those students with physical disabilities. Functional adaptations of the classroom are fundamental

to the students‟ safety and wellness (Hays, 2009).

According to the medical model, students were normally categorised according to their intellectual

functioning in order to assess their cognitive ability (Hays, 2009). A more general, exploratory

definition states that students with an intellectual or cognitive impairment are described as having

difficulty with the processing of information through their senses which as a result will impact on

their ability to learn (Hays, 2009). Avramidis & Norwich (2002) reported that students with mild

physical and mild intellectual disabilities should be on a part time basis rather than on a full time

basis.

Language is an important factor to take into consideration as there are twelve official languages in

South Africa and often schools have one medium of instruction and this is not often the first

language of the students (Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001; Booth, 1999). Pearson and Chambers

(2005) highlighted that student educators were optimistic towards educating students with

language differences, as they seeked strategies, approaches and support to facilitate them in the

classroom. However, according to this research, student educators reported the unavailability of

14

applicable resources necessary for dealing with language as a barrier to learning. The majority of

mainstream schools can promote the linguistic, social and academic development of second

language learners in English; however, general educators have not been trained to address the

educational needs of these learners in a classroom setting (Salend & Dorney, 1997). This could be

rectified by cooperative teaching arrangements between bilingual special education teachers and

general education teachers (Salend & Dorney, 1997). This is seen to remedy the problem as many

general educators are not always adequately trained and equipped to cater specifically for the

needs of the students who are learning in their second, third or even sometimes forth language

(Landsberg, 2005; Salend & Dorney, 1997; Wylde, 2007). However, in South African schools the

joining of bilingual special educators and general educators has been limited (Salend & Dorney,

1997).

Emotional barriers to learning are seen to include students who have been affected by divorce,

disintegration of family life, single parent households or lack of support structures. In South

Africa, many students are exposed to violence and crime which affects students‟ emotional

wellbeing; this can include deprivation, neglect and abuse. According to Hays (2009), socio-

economic and challenging behaviour is seen to fall under the category of emotional barriers to

learning. In South African schools, behaviour control among the students can be a challenging and

often unsuccessful endeavour taken on by educators. This difficult behaviour could include

negative attitudes, oppositional behaviour, aggression and lack of respect for fellow students and

educators (Hays, 2009). Salend & Dorney (1997) stated that the behaviour of a student is seen to

be related to that individual‟s cultural perspective and language background, this may then cause

conflicts as the behaviour of the students may not be the same as the expectations educators may

have within the classroom (Salend & Dorney, 1997). These cultural conflicts may lead educators

to view the student negatively and as having a „deficit‟, this then often results in educators

15

believing that specialised educational services are the only way to assist that student (Salend &

Dorney, 1997).

Studies have shown a common uncertainty about the suitability of including children with

profound sensory deficits, low cognitive ability, mild intellectual disability and hyperactivity in

mainstream schools (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007). However,

contradictory studies found that educators ranked emotional and behavioural difficulties as being

the most challenging to include within the classroom (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Avramidis &

Kalyva, 2007; Avramidis, Baylis, Burden, 2000; Hays, 2009). Engelbrecht et al. (2003) indicated

that apart from learners with behavioural or emotional difficulties, students with intellectual

disabilities seem to provoke the most disagreement over the efficacy of inclusive education

(Avramidis et al., 2000). Lifshits et al. (2004), believes that the inclusion of students with mild or

moderate physical, sensory or medical handicaps do not need as much assistance compared to

students with severe behavioural, intellectual or physical difficulties. Like Avramidis et al. (2000)

they also found that some educators favoured the inclusion of students with hearing impairments

or physical handicaps rather than students who experienced academic or behavioural problems.

These factors have resulted in negative attitudes towards inclusion being formed when educators

were placed in classrooms with these students, as also noted by Burke & Sutherland (2004).

Education White Paper 6 (Department of Education, 2001) stipulates the establishment of three

different types of schools that should provide the structures to accommodate students who

experience barriers to learning and development. This includes special schools as resource centres

for students that need high intensity support. These schools are aimed at providing professional

support for neighbouring schools (Landsberg, 2005). Another level of school is the full service

school, where medium intensity support students are integrated. The third level is the ordinary

schools or mainstream schools, where students that need low intensity support are included

16

(Landsberg, 2005; Hays, 2009). Research has indicated that in developing countries like South

Africa, special needs education requires more financial and human resources than mainstream

education. Due to the lack of these resources to these resource centre schools, the majority of them

are not highly considered by the community which results in students attending mainstream

schools where their barriers to learning may not be optimally addressed (Hays, 2009).

Past research has involved educators‟ attitudes towards students with intellectual disabilities

(Gaad, 2004; Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007), however, there appears to

be more limited research involving educators‟ perceptions towards students with emotional and

behavioural problems even though these were ranked as the hardest to include (Avramidis &

Norwich, 2002; Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007; Avramidis et al., 2000; Hays, 2009). This current

research aims at exploring educators‟ perceptions towards all the barriers to learning which they

may experience within the classroom and not just particularly intellectual functioning.

17

Chapter 2: Educators perceptions of inclusive education

2. Factors that may influence educators‟ perceptions towards inclusive education

Educators need to ensure that students with barriers to learning are provided with opportunities,

just like other students, to construct and engage with knowledge necessary for living in society

(Chappell, 2008). Many educators feel that teaching children with barriers to learning is beyond

their area of expertise and so they should not be expected to teach those students without

assistance (Engelbrecht, 2006; Gaad, 2004; Fox, 2003). Educators have reported several obstacles

that prevent the successful inclusion of all learners in the classroom; namely class size, lack of

resources and teacher training (Lifshitz, Glaubman & Issawi, 2004). Past research has shown that

regular educators lack the appropriate knowledge, support and assistance needed to effectively

meet all the needs of their students (Burke & Sutherland, 2004). Engelbrecht et al. (2003),

identified five areas that are proposed to be the most stressful to eduactors, namely administrative

issues, lack of appropriate support, issues relating to students behaviour, educators self percieved

competence and a lack of interaction with parents of students. O‟Rourke & Houghton (2008),

found that the percieved lack of teaching expertise, limited allocated planning time and a limitation

of resources were the most frequently raised concerns in relation to the implementaion of inclusive

education.

The perceived needs of educators who are seen to accommodate a diversity of learner needs in

mainstream classes needs to be addressed (Engelbrecht et al., 2003). The failure to address the

educators‟ needs and concerns may result in difficulties with the implementation of inclusive

education as well as contribute to educator stress. Inclusive education aims to eliminate barriers to

learning which are inherent in the system itself, which may consist of physical barriers to access,

curriculum barriers or barriers that are created by the climate of the learning environment, to name

18

a few (Engelbrecht et al., 2001). The barriers educators experience in implementing inclusive

education practices will be discussed in detail as it often affects perceptions towards inclusion.

2.1. Teacher attitudes towards inclusive education

Landsberg (2005) states that assumptions, beliefs and attitudes are directly translated into actions

and teaching practices and can also then inform decision making. Attitudes are defined as

educators‟ positive or negative perceptions of what is happening within their classroom with

regard to the students who have barriers to learning (Cross, Traub, Hutter-Pishgahi & Shelton,

2004) 2009). It is fundamental to look at educators attitudes towards inclusive education and

students with barriers to learning as it influences their perceptions as well as their behaviour,

actions and as a result their teaching practices that will inform their decision making (Engelbrecht

et al., 2001; Moolla, 2005). Attitudes are seen to be set once they are formed and are experienced

to be very difficult to change, therefore if educators develop positive attitudes towards inclusion

before they start teaching, then their attitudes towards implementing inclusive education will

become more positive (Lambe & Bones, 2007). Research has indicated that educators often have

very different definitions of inclusion and inclusive education, and the definition that they believe

in is seen to affect the way educators implement inclusive practices in the classroom (Hays, 2009).

A limited number of studies have been conducted on the attitudes of educators towards inclusion

in South Africa (Schimper, 2004; Wylde, 2007; Hays, 2009; Gordon, 2000; Christie, 1998).

Research conducted by Schimper (2004) and Wylde (2007) reported that the majority of their

respondents were positive towards inclusive education, and this indicated the educators dedication

to the underlying rationale for the practice of inclusive education. Studies that have been done on

educators attitudes towards inclusive education have suggested that attitudes are strongly

influenced by the nature of the students disabilities. Educators were seen to be more positive

towards including learners with barriers to learning do not require extra instructional or

19

management skills on the part of the educator (Engelbrecht et al., 2003; Hays, 2009). There is

evidence that suggests that educators‟ improved positive self-evaluation regarding their ability to

teach students with barriers to learning was associated with higher positive attitudes towards

inclusive education (Lifshitz et al., 2004).

Another possible reason why inclusion has struggled in South Africa is due to the African culture

and beliefs on disabilities (Gaad, 2004). Many Africans associate disabilities with witchcraft, juju

or as a phenomenon of God mediated forces. Many negative attitudes towards disabilities stem

from these previously held misconceptions and the lack of proper understanding towards the

medical side of disabilities (Gaad, 2004). These perceptions may filter down into the community,

school and the educators whose attitudes and perceptions could hinder the effective

implementation of inclusive education (Gaad, 2004).

2.2. Educator Stress

Educator stress is best described as a complex process that involves an interaction between the

educator and the environment that includes a stressor(s) and a response (Engelbrecht et al., 2003).

This is seen to involve unpleasant emotions such as tension, frustration, anxiety, anger as well as

depression (Engelbrecht et al., 2003; Moolla, 2005). Educators are seen to experience four types of

stress in terms of their profession. These being namely, difficulties with learners, time pressures,

poor ethos due to poor staff relations and poor working conditions (Engelbrecht et al., 2003;

Engelbrecht, 2006; Moolla, 2005). The implementation of inclusive education could be seen to

place additional demands on educators, potentialy causing stress. It is assumed that educator stress

will be reduced if there are minimal discrepancies between educators‟ perceptions of the

availability of resources and support and their perceived need for those resources and support that

are seen to be used in an inclusive educational environment (Engelbrecht et al., 2003).

20

2.3. Curriculum related issues

The curriculum within a school reflects the economic, social and cultural conditions of the

community and gives all members of society a voice (Chappell, 2008). However, this is not always

that easy to achieve. Educators were expected to shift their teaching to Outcomes Based Education

(OBE), this resulted in many educators feeling overwhelmed, frustrated and helpless due to the

changes that occurred (Engelbrecht et al., 2001). OBE is „inclusive‟ by nature and focuses on

students learning at their own pace, and takes into consideration the barriers to learning found in

the classroom (Hays, 2009; Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001). Educators became concerned and

worried about meeting governmental standards that the Educational Department emphasised and

then also meeting the individualised goals for each special needs student (Cushing et al., 2005).

The governmental standards educators need to meet involves the adapting of the Government

Curriculum as well as their teaching styles in order for inclusion to become successful (Burke &

Sutherland, 2004; Engelbrecht et al., 1999). Research has indicated that educators are generally too

inexperienced to be able to handle the demands of the new curriculum (Curriculum 2005), and this

could result in educators being reluctant to introduce new concepts and approaches to their

teaching (Hays, 2009). Recently, Curriculum 2005 has changed and this may require educators to

once again adapt themselves to further changes. This is due to many educators perceiving

themselves as incapable of managing diverse classrooms (Hays, 2009).

The curriculum is classified as an inflexible standard, which results in the lack of relevance of

subject content to all students. This could result in high levels of failures and drop outs

(Department of Education, 2001; Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001). The curriculum is seen to be an

external barrier to learning and it therefore obliges educators to use different teaching methods to

address these concerns (Hays, 2009). Therefore, curriculum differentiation is a vitally important

aspect to assist in the effective implementation of inclusive education (Engelbrecht et al., 2003).

Ghesquiere, Moors, Maes and Vanddenberghe (2002) indicated that educators differentiated

21

teaching methods in the hope of differentiating the curriculum; however, the educators in their

study did not adapt the goals, content and evaluation methods to each individual need. Avramidis

et al. (2000), reported that educators perceived material resources as vital components in adapting

the curriculum to students with different barriers to learning. Changes to existing educational aids

are fundamental to enable students to participate in classroom activities and routines (Hays, 2009;

Wylde, 2007).

O‟Rourke & Houghton (2008) and Moolla (2005) mentioned mechanisms or skills that are

effective in the implementation of inclusive education, these being co-operative learning, explicit

and indivualised instruction, peer support, curriculum differentiation and instructional strategies as

well as teacher collaboration. Shongwe (2005) reported the following effective strategies for

teaching in an inclusive classroom, namely group work, which provides support for students with

barriers to learning from their educators and their peers in the classroom. Group work may also

create a better understanding of cooperative learning and is beneficial to effective classroom

management (Shongwe, 2005). Fox (2003) stated that if educators used a structured teaching style,

and appropriate support was provided, then the successful inclusion of students, irrespective of the

type or severity of their barrier to learning is possible.

2.4. Training issues

In South Africa, teacher education has been characterised by fragmentation and involves deep

disparities in both duration and quality (Engelbrecht et al., 2003). Many educators are seen to be

disadvantaged due to their poor quality of their training within the field (Engelbrecht et al., 2003).

Research has indicated the need for professional development including initial teacher training and

continued professional development as being central to the effective development of inclusive

practices (Avramidis et al., 2000; Pearson & Chambers, 2005).

22

In the past, in-service training was predominantly provided by universities, teacher training

colleges and non-governmental or private organisations (Logan, 2002). These were generally

uncoordinated with no clear overall policy guidelines formulated by government education

departments (Logan, 2002). This resulted in educators determining their own development

programmes to be able to meet the needs and knowledge necessary (Logan, 2002). The problems

found with these in-service training programmes were that they were predominantly inaccessible

to all educators in South Africa; this was due to their cost, entry criteria and qualifications,

language proficiency of the educators, travelling costs as well as the workload (Logan, 2002). All

of these factors mentioned created barriers that prevented educators from benefiting from theses

training services.

Internationally funded government programmes within South Africa like The Danish Development

Agency (DANIDA project) and the South African-Finnish Co-operation Programme in the

Education Sector (SCOPE) funded various in-service programmes in which a cascade model was

used to introduce and support inclusive education in several South African provinces (Amod,

2004; Logan, 2002). The cascade model was designed for one or two representatives from each

school to attend the programmes and then relate the knowledge and skills they learnt to their

fellow colleagues (Engelbrecht, 2006). Problems occurred when representatives had to transfer

their knowledge and skills to their colleagues, who often seemed disinterested in the activity or

time constraints made it impossible to relay all the information (Engelbrecht, 2006). Another cause

for the poor outcomes of training programmes in South Africa has been poor teacher collaboration,

which has resulted in educators working in isolation (Logan, 2002). The absence of a team or

whole school approach in many school districts results in external professional development

courses being restricted to individual educators and classrooms; this resulted in small pockets of

students benefiting (Logan, 2002).

23

Studies have shown that professional development courses on inclusive education have resulted in

less resistance towards inclusive practices by educators and a reduction in educators stress levels

when coping with inclusion (Avramidis & Kalyva, 2007). Educators‟ prior knowledge of inclusive

education from pre-service training, as well as in-service training were found to have more

positive attitudes towards inclusion than teachers who had not gained that knowledge (Downing &

Williams, 1997; Hays, 2009; Logan, 2002; Wylde, 2007). Training that involves administrative

issues surrounding inclusive education, exposure to the best inclusive practices, collaboration with

colleagues and parents, as well as the availability of support structures are viewed as fundamental

aspects of educator training in inclusive education (Amod, 2004; Engelbrecht et al., 2003).

Engelbrecht et al. (2003) stated that educators should be provided with extensive training in

managing emotional and behavioural problems of students in the classroom in an attempt to

address barriers to learning within the classroom.

Educators that were trained to teach students with barriers to learning expressed more positive

attitudes towards inclusion compared to educators that had not had any previous training (Lambe

& Bones, 2007; Lifshitz et al., 2004). Research has suggested that students who complete a Post

Graduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) course have very different school experiences and are

often exposed to different levels of barriers to learning in the classroom, which has resulted those

universities to assess their training course to allow all educators to be exposed to the same teaching

experiences (Pearson & Chambers, 2005). The researchers of this study found that students were

largely positive about the principle of inclusion, however, challenged by the implementation of the

policies. Emotional and behavioural changes were seen to occur when educators were informed

and exposed to practical experiences involving disabilities and barriers to learning (Lifshitz et al.,

2004). A study conducted by Lambe and Bones (2006) found that positive attitudes are seen in

student educators at the start of their pre-service training, it concluded that educators attitudes

24

should be nurtured during that period and this could be done by the provision of high quality

training.

Research conducted by Engelbrecht (2006) found that in-service training for South African

educators was fragmented and short term and often lacked in-depth content and knowledge. These

training programmes often do not take into consideration the unique contextual influences of each

school. The National Professional Teachers‟ Organisation of South Africa (NAPTOSA) criticised

the trainers of many of these programmes for discouraging educators from being critical and

asking questions within the training programmes (Logan, 2002). Inclusive education would be a

difficult task if there is no future education and training for educators. This is due to the proven

fact that educators‟ perceptions or attitudes become more favourable and positive with more

training in the inclusive policies and skills (Amod, 2004; Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Thomas et

al., 1998). A study completed by Scott (2006), reflected the frustration educators felt towards

promised classroom support and curriculum training by the government. As these studies

mentioned above purely focused on educators perceptions of the training courses, this study needs

to take into consideration that perceptions represent subjective experiences and not always reality.

Educators may have had excellent training in reality but they may have perceived it to be

insufficient and unhelpful (Hays, 2009; Logan, 2002). The researcher reiterates the views of others

such as Logan (2002) and Moolla (2005) on how possible training in South Africa can become

given the large amount of educators needing training with the limited financial resources available.

2.5. Support structures and systems

In the past, the inadequate resources provided to mainstream education was seen to be the cause of

educational stress for educators interested in helping students with special needs (Engelbrecht et

al., 2003). The active involvement of parents is a central factor in the child‟s effective learning and

25

development (Amod, 2004; Burke & Sutherland, 2004; Hammond et al., 2003; Engelbrecht et al.,

2003). The South African Schools Act mentions the recognition of parents as the primary

caregivers of their children and therefore they are the central resource to the education system.

This however, does not occur frequently in government schools and educators report the increase

of stress surrounding the limited contact with parents of students especially with intellectual

disabilities. The socio-economic status of the parents was seen to be the main contributor of

parents‟ lack of involvement with their child‟s education (Amod, 2004; Engelbrecht et al., 2003).

The reasons for this may be due to the difficulty for parents to attend after school meetings,

parents who work long distances away from home as well as poor health affecting their ability to

get involved in school activities. In poorer communities, educators need to take initiative to reach

out to parents to make them a part of the school community (Engelbrecht et al., 2003).

The support provided to educators, namely from parents, principals, colleagues and special needs

educators is often lacking in schools or just ineffective in helping the educators deal with the

pressures of inclusive education (Hammond et al., 2003; Burke & Sutherland, 2004). Educators

have reported the need for consultation with other professionals namely psychologists, speech and

language therapists to name a few (Moolla, 2005; Shongwe, 2005). Engelbrecht et al. (2001) and

Amod (2004) mentioned the enabling structures and mechanisms that could be put into place to

help support educators. These include the establishment of school-based support teams (SBST),

district support teams (DST), special schools as resources, School Governing Body (SGB),

School-Based Staff Development Programmes (SBSDT) as well as the use of local community

resources, and learner-to-learner support. A study completed by Avramidis et al. (2000), reported

that 56% of educators stated they needed more support with students with barriers to learning, this

was not just more people in the class (extra teachers) but a stronger Special Educational Needs

Department and Learning Support Team.

26

Students with barriers to learning are often seen to require social support in an inclusive

classroom. This is broadly viewed as the process by which individuals feel valued, cared for, and

connected to a group of people which as a result will shape that individuals values, belief systems

and thought processes (Pavri & Monda-Amaya, 2001). The sense of belonging and membership at

school, recieving instrumental assistance and emotional support from key members in ones social

network, impacts positively on the social well being of students with barriers to learning (Pavri &

Monda-Amaya, 2001; Wylde, 2007). Research indicates that inclusive classrooms promote

reciprocal friendships between students with learning difficulties and their peers, and this then

enhances students social satisfaction at school (Pavri & Monda-Amaya, 2001; Shongwe, 2005).

However, there is conflicting research that indicates that inclusive education could be disasterous

to disabled peers, detrimental to students with no barriers to learning and students with barriers to

learning may suffer from peer rejection and inferiority complexes (Shongwe, 2005; Wylde, 2007).

Studies have reported that students without any particular barriers to learning become more

accepting, understanding and acknowledge similarities with students with special educational

needs when they are exposed to them in the classroom (Downing & Williams, 1997). These

students become more aware of other children‟s needs, more comfortable around people with

disabilities, more accepting of differences as well as an improved social and emotional

development (Downing & Williams, 1997; Hays, 2009). However, even though inclusive

education can be a positive factor to students with no barriers to learning, it is also reported to be

detrimental to these students at times (Shongwe, 2005). This can be due to parents reporting

educators‟ lack of time spent assisting all learners in the class (Shongwe, 2005).

2.6. Educators personal characteristics

Research has shown mixed views on the relationship between educators‟ age and gender and their

views towards inclusive education. Avramidis et al. (2000) stated that none of those variables were

27

found to be significantly related to educators‟ attitudes. Research conducted in South Africa did

not produce any significant relationships between the age of the educator and their attitudes

towards inclusive education (Wylde, 2007). In contrast Parasuram (2006) reported that educators

in the age range of 20-30 years had more positive attitudes towards inclusion compared to 40-50

year olds (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Christie, 1998). This could be due to the younger

generation being exposed to changes such as globalisation, information technology and internet

growth (Parasuram, 2006). Some studies found that woman tend to have more positive attitudes

towards people with disabilities (Parasuram, 2006; Avramidis & Norwich, 2002), while others

reported that gender was not related to attitudes towards inclusive education (Avramidis &

Norwich, 2002).

Research has also shown mixed views on the relationship between the number of years of teaching

experience and educators‟ views towards inclusive education. According to a study reported by

Parasuram (2006), educators who had 5-10 years experience had more favourable or positive

attitudes compared to those with 10 to 12 years experience. A recent study conducted in South

Africa showed that educators who had been teaching for 12 years or more really struggled to

change their perceptions towards effective teaching methods (Scott, 2006). The inability to adapt

their teaching methods can result in added stress for educators which could possibly result in

negative perceptions towards inclusive education (Scott, 2006; Lambe & Bones, 2007). The

amount of years educators have been in contact with special education needs students is also an

important factor to consider (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Lambe & Bones, 2007; Avramidis, et

al., 2000; Hays, 2009). Avramindis & Norwich (2002), found that the more experience educators

had with special needs students the more favourable their attitudes towards inclusion tended to be

and the more confident the educators became. However, according to a study conducted by Moolla

(2005), the majority of educators reported limited experience working with students with barriers

to learning and this resulted in educators‟ lack of confidence to teaching in new situations.

28

2.7. Class size

A very commonly reported barrier to effective learning in an inclusive classroom is class size

(Avramidis & Norwich, 2002; Shongwe, 2005; Wylde, 2007). The more students with barriers to

learning in a class, the less time is given to all the other students as majority of special education

needs students need more one-on-one time from the educators (Avramidis & Norwich, 2002).

Avramidis et al. (2000) reported that educators agreed that class size should be reduced to 20

students per class, in order to allow for the effective implementation of inclusive education.

Educators also may struggle with too many students as the discipline and behaviour issues become

more of a problem. Many of the barriers to learning mentioned above relate to the insufficient

allocated time educators have in order to fully address inclusive education practices, namely time

to plan the following day and time to adapt the curriculum in order to address the students with

barriers to learning (Avramidis, et al., 2000).

Due to all these barriers to learning mentioned above, it can be seen that it is vital to take into

account the unique context of the school when planning and developing inclusive educational

programmes (Engelbrecht, 2006). Research has indicated that while educators support inclusive

education on the whole, many have concerns regarding its implementation (Amod, 2004; Hays,

2009). Salisbury (2006, pg. 70) states “The capacity of schools to address the diverse needs of

students who differ in their ability, language, culture and socio-economic standing will require that

schools alter not only their structures, policies and practices, but the underlying philosophy of the

school and the attitudes and beliefs of school personnel”.

2.8. Conclusion

In some international government schools where inclusive education is a law, there are many

examples where students with barriers to learning are fully included and successful. However,

29

most of the time the implementation of these policies is the real challenge (Lomofsky & Lazarus,

2001). Without a strong view on the development of an inclusive education and training system for

educators, the goal of implementing inclusive education throughout South Africa will not become

a reality (Lomofsky & Lazarus, 2001; Hays, 2009). Education White paper 6 defined one aspect of

inclusive education and training that is vitally important in this research. This is the ability to

change perceptions, attitudes, behaviour, teaching methods, curricula and the environment in order

to meet the needs for all students (Department of Education, 2001). This study aims to research the

perceptions of educators as perceptions can only be changed if you know what they are to begin

with and by changing people‟s perceptions often their behaviour can be changed as well. The way

that inclusion is perceived by educators is seen to impact significantly on the way students‟

barriers to learning are perceived and addressed.

30

Chapter 3: Methodology

This chapter presents the methodology used within the research study. It begins by describing the

aims and methods used for the investigation and then describe the methodology used in the study.

3.1 Aims and Research Questions

The aim of this research study was: To explore educators‟ perceptions towards inclusive

education.

The specific research questions in relation to the above aim of the study were:

i) What are the educators‟ views and understanding of inclusive education within a sample

of government primary schools?

ii) What do educators perceive to be barriers to learning within the classroom?

iii) What are the skills educators think they need in order to implement inclusive education?

iv) What are the support structures educators use to assist them in the implementation of

inclusive education?

v) What are the training programmes educators have participated in involving inclusive

education and their perceptions of these training programmes?

vi) What are other training programmes educators would like to assist them in implementing

inclusive education?

vii) Is there a relationship between the number of years of teaching experience and the

perceptions of educators towards inclusive education?

3.2. Context of the study

In the current study six government primary schools in the Gauteng region participated in the

research. Government schools were used within this study as they follow the policy of Education

White Paper 6: Building an Inclusive Education and Training System (Department of education,

31

2001). These six schools selected were from the Johannesburg East District and were all located in

the northern suburbs of Gauteng. These schools had different numbers of educators who taught

from Grade 0 to Grade 9 in a co-ed environment. According to the School Survey Checklist, all

the schools fall within a similar socio-economic bracket in terms of resources present at each

school. Many of the schools in this current study do not have specialised professionals at the

school, however, they stated that they have professionals to whom they refer students and with

whom they communicate with on a regular basis. All the schools in this study indicated that they

had no ramps for wheelchairs, and this will be discussed in terms of barriers to learning within the

discussion section. The schools were not consistent with the relation of the number of students per

educator within a class, and as a result this fluctuated between less than 30 students to one

educator to 40 students per one educator, the average being in the range of one educator per 30 to

35 students. The results of the ratio of students per class teacher will be discussed in more detail

later in this chapter.

3.3. Research Design

As the aim of this study was to explore educators‟ perceptions towards inclusive education, a

qualitative research design approach appeared to be the appropriate strategy to use. The aim of a

qualitative research design is to understand experiences as they are „lived‟ or „felt‟ according to

each individual (Sherman & Webb, 1988). The research was a non-experimental, descriptive study

that used a survey approach to explore the perceptions of educators towards inclusive education.

The non-experimental design described by Terre Blanche & Durrheim (2002) was used to meet the

descriptive nature and aims of the study.

32

3.4. Sampling

A non-probability sampling method of convenience sampling (Terre Blanche & Durrheim, 2002)

was used and the sample was chosen according to their geographic location. This is due to the

studies aim to focus on a wide range of government primary schools in the Gauteng region. The

sample size of this study was aimed at approximately 100 educators in total, from the selected ten

government primary schools in Gauteng. However, after all questionnaires were collected from the

schools only six schools had collected completed the Inclusive Education Questionnaires

(Appendix B) while the other four schools responded that the educators were too busy and none

had responded. After collecting all the completed forms from the six schools, only forty Inclusive

Education Questionnaires (Appendix B) were collected in total.

In relation to sample description, there were equal amounts of educators from the ages of 20 – 30

years as there were educators above the age of 30 years. The majority of the sample (53%) of the

sample had less than 5 years of teaching experience and had been teaching at their current school

for less than 5 years (70%).

3.5. Instruments

The principals of the government primary schools that participated in the study completed the

School Survey Checklist, which involved a checklist of resources available in the school and the

demographic data of each school (Appendix E). Each Checklist was allocated a unique two digit

code that was then placed on the Inclusive Education Surveys that the educators completed. This

was used to maintain the confidentiality of the participants as no identifying information was

required. The School Survey Checklists took approximately five minutes to complete by each

principal. The questions included the number of learners in the school, the teacher-pupil ratio,

33

physical resources, teaching materials and human resources that are present in the school. This

helped form part of the demographic data for each school that participated in this research study.

The educators who participated in this study completed the Inclusive Education Questionnaire,

which was a self adapted questionnaire that involved different aspects related to the

implementation of inclusive education. Internal consistency of the questionnaire was measured

using Cronbach Alpha coefficient (Huck, 2004). Initially the result of the Cronbach Alpha

coefficient was 0.65 which is a weak result according to the reliability of the test. The researcher

removed Question i and j from the analysis which related to the perception of inclusive education

being successful at different schools. The therapist then reran the reliability which yielded a more

positive Cronbach Alpha coefficient of 0.8. The questionnaire consisted of three biographical

questions to describe the sample: the number of years the participants had been teaching, the

number of years they had been teaching at their current school and their age range. Each Inclusive

Education Questionnaire that was administered was given a unique two digit code (same as the one

used on the School Survey Checklist) and a unique number that gave each questionnaire a separate

coding system. The questionnaire took approximately 30 minutes to complete.

The questionnaire was based on previous questionnaires developed by Schimper (2004) and

subsequently used by Wylde (2007). The questionnaire originally devised by Schimper (2004)