DECEMBER

UNITED STATES INTERAGENCY COUNCIL ON HOMELESSNESS

ALL IN:

The Federal Strategic Plan to

Prevent and End Homelessness

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 2

December 19, 2022

Every American deserves a safe and reliable place to call home. It’s a matter of security,

stability, and well-being. It is also a matter of basic dignity and who we are as a Nation.

Yet many Americans live each day without safe or stable housing. Some are in emergency

shelters. Others live on our streets, exposed to the threats of violence, adverse weather, disease,

and so many other dangers exacerbated by homelessness. Both the COVID-19 pandemic and the

reckoning our Nation has faced on issues of racial justice have also exposed inequities that have

been allowed to fester for far too long.

At the same time, we know we can do something about it. That is why I’m proud to present the

Biden-Harris Administration’s Federal Strategic Plan to reduce homelessness by 25 percent by

January 2025—an ambitious plan that will put us on the path to meeting my long-term vision of

preventing and ending homelessness in America. We need partners at the State and local levels,

in the private sector, and from philanthropies to all play a part in meeting this goal.

My plan offers a roadmap for not only getting people into housing but also ensuring that they

have access to the support, services, and income that allow them to thrive. It is a plan that is

grounded in the best evidence and aims to improve equity and strengthen collaboration at all

levels.

My plan builds on the foundation my Administration has laid since I came to office. When I

signed the American Rescue Plan in March 2021, we provided tens of billions of dollars in rental

assistance to people who were struggling during the pandemic through no fault of their own—

reducing eviction filings and keeping millions of Americans from being thrown out of their

homes. Communities across the country are using American Rescue Plan funds to create more

permanent affordable housing and support State and local initiatives to address homelessness.

But, there’s much more to do. Americans of all backgrounds all across the country are

struggling with housing costs that have far outpaced wage growth. At the same time, often due

to historical inequities, veterans, low-income workers, people of color, LGBTQI+ Americans,

people with disabilities, older adults, and people with arrest or conviction records are at greater

risk of homelessness. They have fewer opportunities to access safe, affordable housing and

health care and face more barriers to fulfilling these basic needs once they lose them.

This plan meets the urgency of the moment. It recognizes that it’s not enough to go back to the

way things were before the pandemic. We must build a better future for all Americans. This

plan also recognizes that homelessness should not be a partisan issue. A great nation has a moral

obligation to ensure housing, but it’s also the smart thing to do.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 3

When we provide access to housing to people experiencing homelessness, they are able to take

steps to improve their health and well-being, further their education, seek steady employment,

and bring greater stability to their lives and to the community that surrounds them. That not only

saves individual lives, it also pays ongoing dividends for neighborhoods, cities, states, and our

entire country. By ensuring more Americans have safe, stable, and affordable homes, we can

build a stronger foundation for our entire Nation.

J

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 4

Message From USICH Chairs

It has been our shared honor to lead the United States Interagency Council on

Homelessness (USICH) through the development of this new Federal Strategic

Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness, which will put our country back

on track toward the goal of ending homelessness. Homelessness should not

exist in the richest country in the world. As the former chair (Marcia Fudge,

2021-2022) and current chair (Denis McDonough, 2022-) of USICH, we are

working not just to reduce but to ultimately end homelessness, period.

Homelessness is solvable. We know this because we have seen it done. When

the Obama-Biden administration released the nation’s first comprehensive

strategy to prevent and end homelessness in 2010—titled Opening Doors: The

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness—it launched a period

of focus, resolve, and targeted investment that drove year-on-year reductions

in homelessness, especially for veterans. Since 2010, veteran homelessness

has decreased by more than half,

1

with over 960,000 veterans and their

family members becoming permanently housed or prevented from becoming

homeless. The lessons learned and the innovative practices that emerged

from our work with veteran homelessness serve as a roadmap for solving homelessness among all

Americans. And though in recent years that progress has slowed, we have seen those eorts renewed

with the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021* (ARP) and other federal eorts to address the current

crisis.

The Biden-Harris Administration has made ending homelessness a top priority. The ARP

provided a historic opportunity to invest in short- and long-term solutions to homelessness, with

an unprecedented level of funding going directly to local governments. The Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (CDC) supported new collaborations between health departments and

local homeless Continuums of Care with funding and public health guidance. The Department of

the Treasury distributed emergency rental assistance to millions of low-income renters and gave

state and local governments flexibility to use ARP funds for aordable housing. Under ARP, the

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

reimbursed the cost of non-congregate shelter to

reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission in congregate settings. The Department of Education

granted states and school districts funds to better identify students experiencing homelessness

and to connect those children and youth to school and community-based interventions and

wraparound services. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) distributed ARP

funds

2

to nearly 1,400 health centers across the country, which provide health care and support

services to nearly 1.5 million people experiencing homelessness. The Department of Housing and

Urban Development (HUD) distributed emergency housing vouchers and HOME-ARP funding,

focused on strengthening fair housing and tenants’ protections, and doubled its homeless services

budget since President Biden took oce. The Department of Veterans Aairs (VA) used the

additional resources and flexibilities provided under the ARP to prevent and end homelessness

*The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (P.L. 117-2) was signed into law by President Joe Biden on March 11, 2021.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 5

for 69,946 veterans and their family members during fiscal year 2021 and, between January and

September 2022, VA worked with veterans to achieve more than 30,000 permanent housing

placements from homelessness.

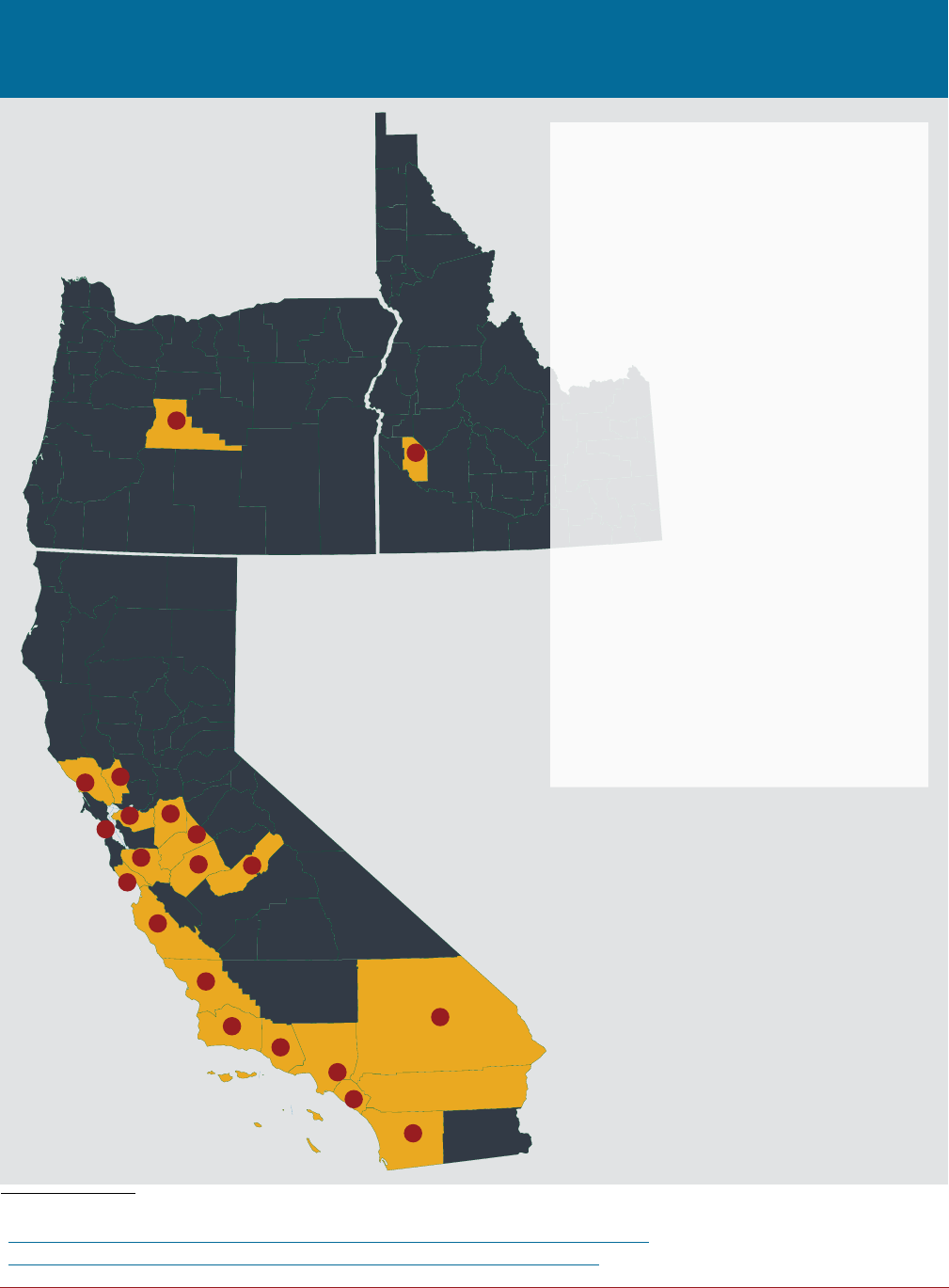

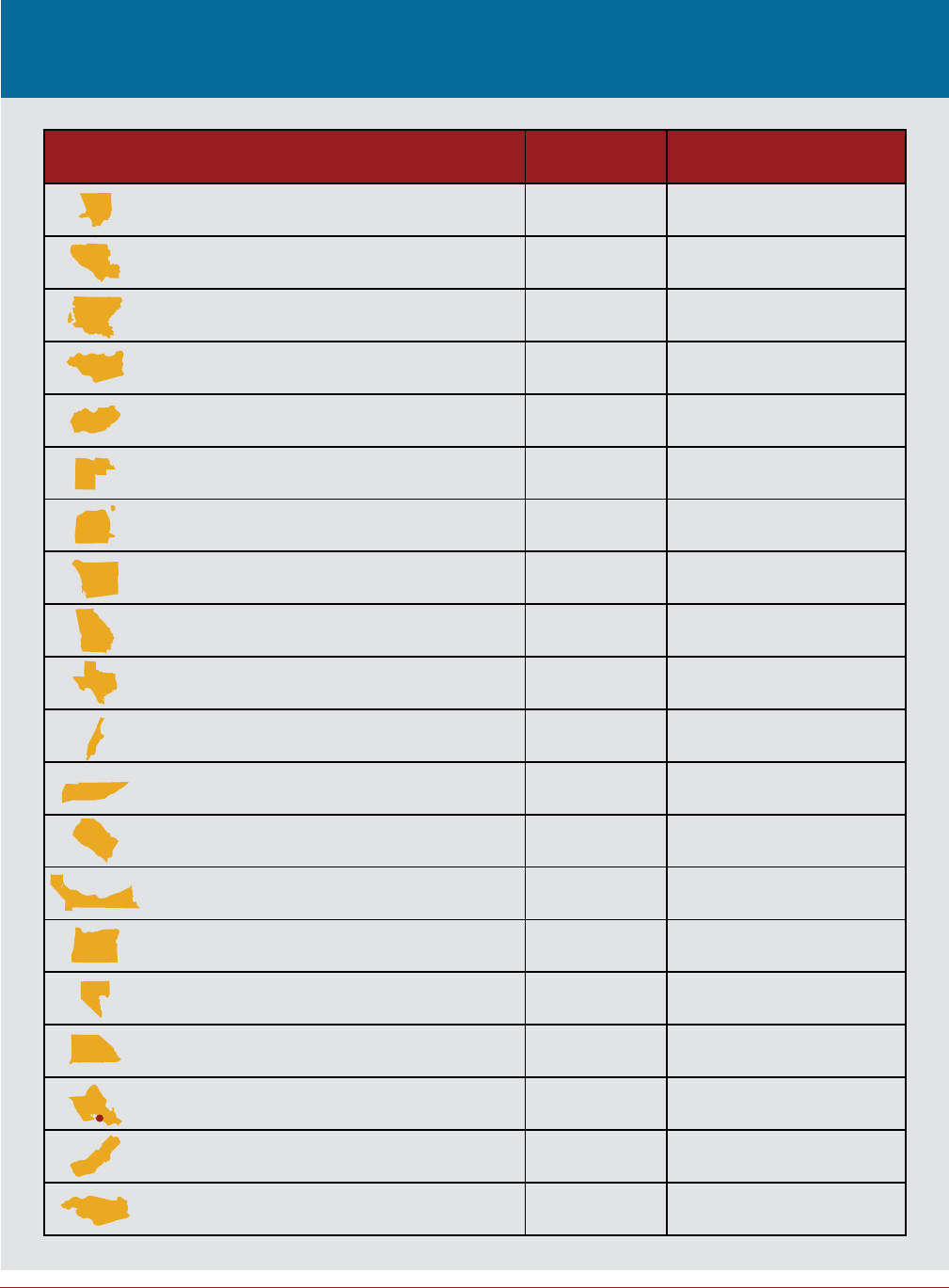

In 2021, HUD and USICH launched House America: An All-Hands-on-Deck Eort to Address the

Nation’s Homelessness Crisis to invite mayors, city and county leaders, tribal nation leaders, and

governors into a national partnership to rehouse people and expand aordable housing using

ARP funding and the Housing First approach. Leaders of more than 100 communities joined

this nationwide initiative and committed to setting goals for rehousing and housing production

through the end of 2022. We thank them for their leadership, and we are eager to share the lessons

of their success with even more communities across the country.

Along with these activities across the federal government, USICH engaged in extensive listening

sessions with thousands of leaders, providers, and advocates, and hundreds of people with lived

experience to inform the new Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness. We are

proud and pleased to present this new plan, which restores the importance of Housing First; is

grounded in the voices of people who have experienced the trauma of homelessness; and does

more than any previous plan to set a strategic and equitable path toward the systematic

prevention of homelessness.

Solving homelessness means recognizing and confronting the factors that may have led to the

tragic circumstance of homelessness. It means being guided by the data and evidence that some

Americans who face ongoing discrimination are disproportionately overrepresented among

those experiencing homelessness—especially people of color, LGBTQI+ people, and people

with disabilities. It means recognizing that experiencing the crisis of homelessness is a form of

significant trauma that can impact individuals and families for decades and generations. Solving

homelessness means delivering help to the people who need it most and who are having the

hardest time. It means putting housing first, along with the person-centered supports needed to

succeed and thrive.

With this plan, we recommit the federal government to person-centered, trauma-informed,

and evidence-based solutions to homelessness. We are confident in the knowledge that recovery

is possible, that voluntary supportive services are the most eective way to reach people in need,

and that communities across this nation can welcome and treat their unhoused neighbors with

justice, respect, and dignity.

While we acknowledge there is much work ahead, we are proud of the work this administration has

done to address homelessness. Together and with our fellow members of USICH, we look forward

to partnering with and learning from you as we continue our work to end homelessness in America.

VA Secretary Denis R. McDonough

USICH Council Chair, 2022-2023

HUD Secretary Marcia L. Fudge

USICH Council Chair, 2021-2022

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 6

Message From the Executive Director

Homelessness in the United States is an urgent life-and-death public health

issue and humanitarian crisis. Far too many Americans live—and die—without

a roof over their heads. This is disproportionately true for people of color—

Black, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Latino

3

people in particular—

reflecting the compounding eects of racial discrimination in housing,

employment, health care, and education that persist to this day. It does not have

to be this way. Homelessness is not inevitable, and it is not unsolvable. At

USICH, we envision a future in which no one experiences homelessness—not even for one night.

USICH believes that housing should be treated as a human right, and that housing is health care.

We prioritize the use of data and evidence for eective policymaking and know that an evidence-

informed approach to ending homelessness will require us to address the barriers and disparities

that people of color and other marginalized groups too often face. Advancing the most eective

policy solutions will require that people who have experienced homelessness firsthand should

be in positions of power to shape federal, state, and local policy. We can prevent homelessness

before it starts by scaling up housing and supports, —both of which are critical to ending

homelessness. The federal government must listen to local needs, support local innovation, and

foster collaboration and partnerships. The United States of America can end homelessness

by fixing public services and systems—not by blaming the individuals and families who

have been left behind by failed policies and economic exclusion.

Many Americans, especially those whose neighborhoods and communities have been most directly

impacted by the homelessness crisis, ask, “How do we end homelessness in the United States?”

This plan outlines a set of strategies and actions for achieving such a vision. The plan is built upon

the foundations of equity, data, and collaboration, and designed around the solutions of housing

and supports, homelessness response, and prevention. It points to a single goal—a 25% reduction

in homelessness by 2025. Achieving this ambitious goal is a critical first step on our national

journey to end homelessness.

This work will require a deep commitment on the part of the federal government as well as state

and local leaders, nonprofits, the faith community, and the business and philanthropic sectors; and

it must be shaped by those closest to the crisis—people who have experienced homelessness.

Homelessness is not a partisan issue. Division and finger-pointing will not solve the crisis. We as

a nation have come together before to tackle dicult challenges, and we can do the same with

homelessness. We must find common ground, scale what works, and develop new and

creative solutions until homelessness is a relic of the past and every American has a safe, stable,

accessible, and aordable home.

Je Olivet

USICH Executive Director

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 7

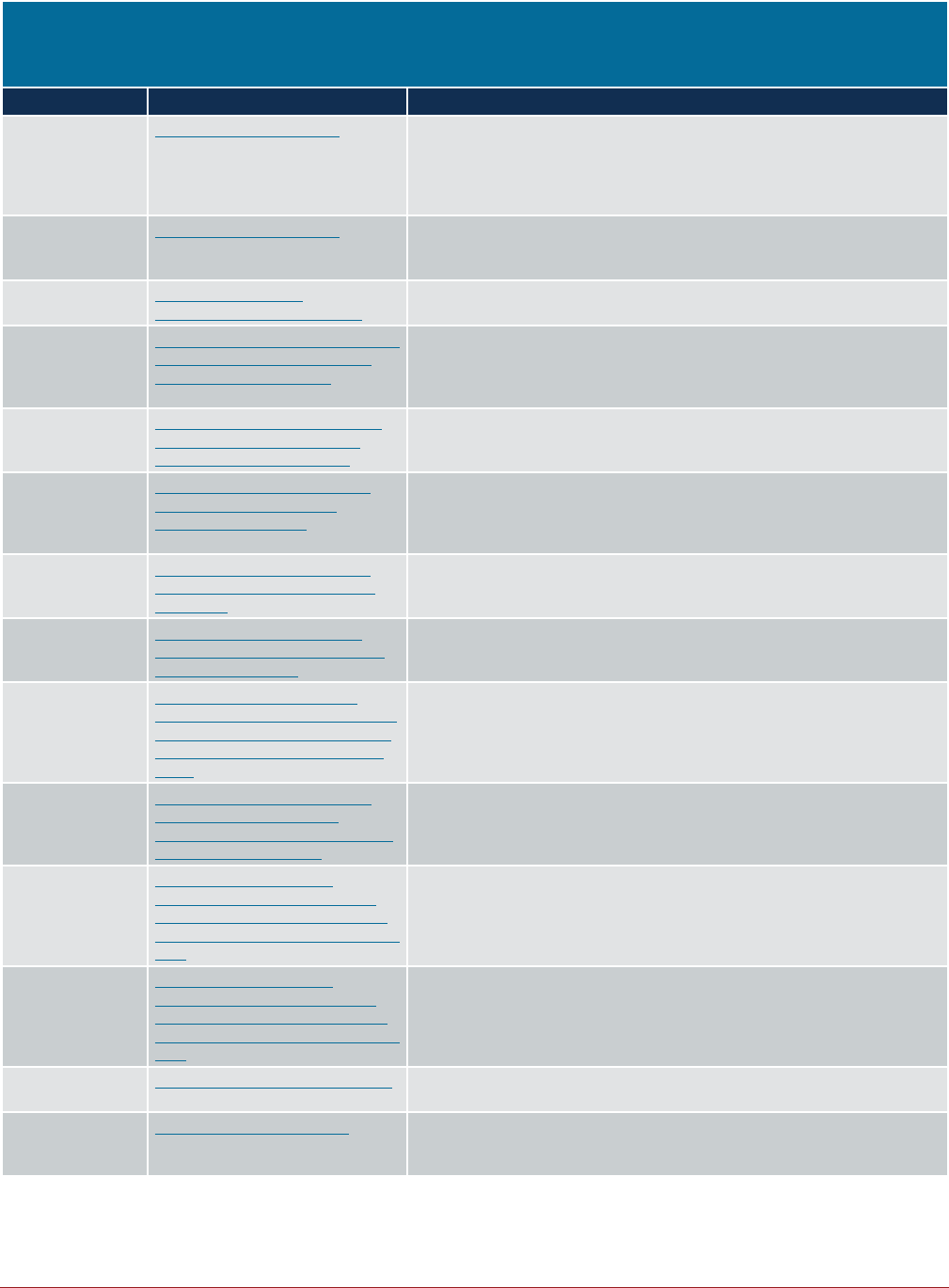

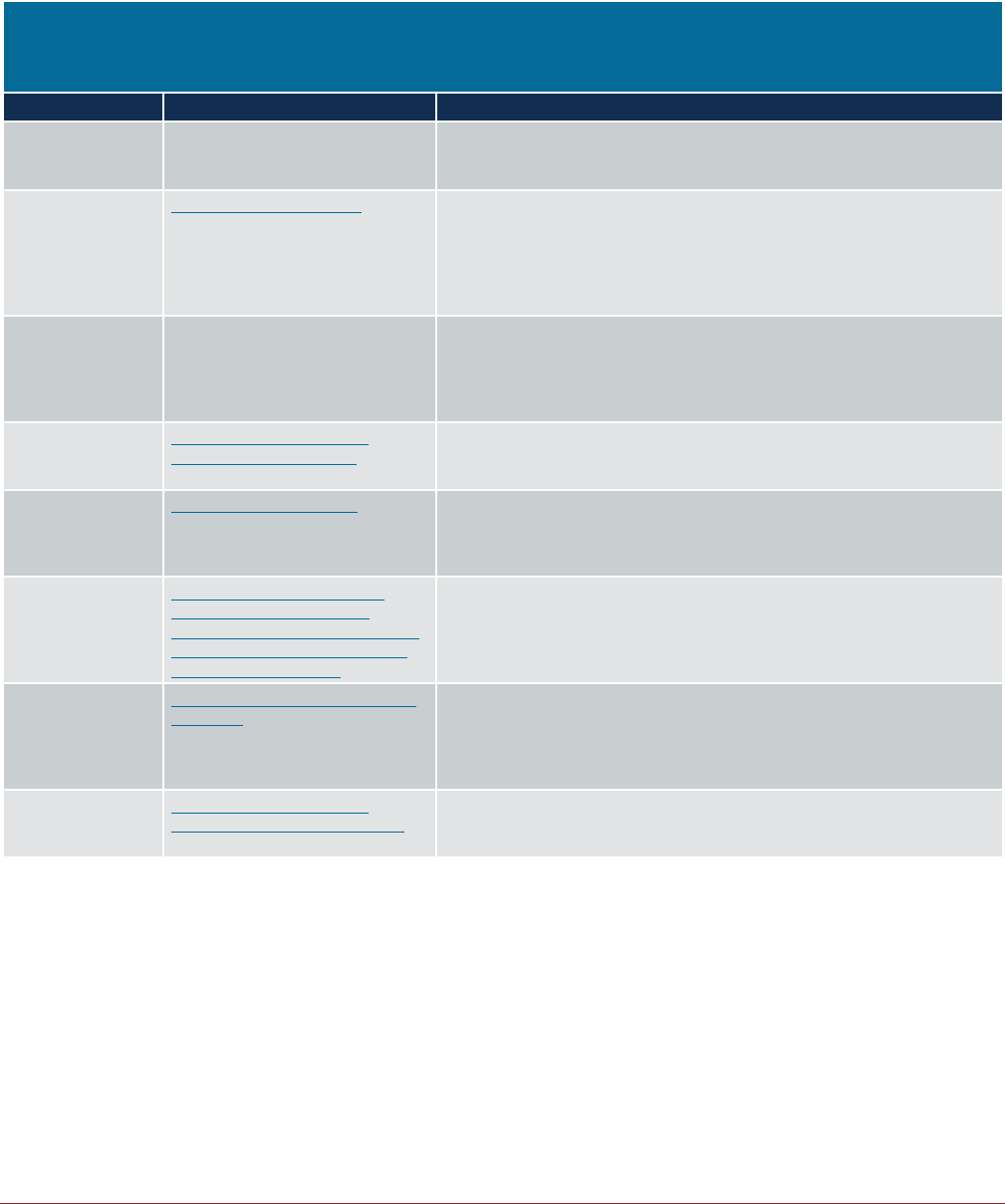

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................8

Executive Summary

....................................................................................................................................9

State of Homelessness

.............................................................................................................................12

Vision for the Future

................................................................................................................................24

Federal Strategic Plan

.............................................................................................................................. 26

Framework for Implementation

..............................................................................................................70

Appendix A: How This Plan Was Created

................................................................................................72

Appendix B: Inventory of Targeted and Non-Targeted Federal Programs

................................................73

Appendix C: Glossary

...............................................................................................................................88

Appendix D: References...........................................................................................................................96

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 8

Acknowledgements

This plan builds upon the successes and strengths of previous USICH plans as well as the work of our

partners at the federal, state, and local levels.

USICH would like to thank the thousands of people across the country—including sta from local,

state, and national agencies and organizations; community volunteers; advocates; and the more than

500 people with past and current experiences of homelessness—who provided their time and expertise

to ensure this plan reflects a diversity of perspectives. Their continued counsel and partnership will be

necessary for action and implementation.

USICH would also like to thank the 19 federal agencies* that make up the council as well as the White

House Domestic Policy Council, each bringing its own perspectives and priorities to the plan:

1. AmeriCorps

2. U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)

3. U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC)

4. U.S. Department of Defense (DOD)

5. U.S. Department of Education (Education)

6. U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)

7. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

8. U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS)

9. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

10. U.S. Department of Interior (Interior)

11. U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ)

12. U.S. Department of Labor (DOL)

13. U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT)

14. U.S. Department of Veterans Aairs (VA)

15. General Services Administration (GSA)

16. Oce of Management and Budget (OMB)

17. Social Security Administration (SSA)

18. U.S. Postal Oce (USPS)

19. White House Oce on Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships (FBNP)

Special thanks to consultants Colleen Echohawk, Norweeta Milburn, Rhie Azzam Morris, and Jama

Shelton, who partnered with USICH by sharing their expertise and unique lenses to the development of

this plan—and to designers David Dupree and Malcolm Jones of Abt Associates for designing the plan.

For more information on how this plan was created, see Appendix A on Page 72.

* USICH’s federal collaboration is not limited to the 19 agencies that make up the council. USICH also engages with other agencies and oces,

including the U.S. Department of the Treasury, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, White House Council on Native American Aairs, and

White House Oce of National Drug Control Policy.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 9

After steady declines from 2010 to 2016, homelessness in America has been rising, and more

individuals are experiencing it in unsheltered settings, such as encampments. This increase stems from

decades of growing economic inequality exacerbated by a global pandemic, soaring housing costs, and

housing supply shortfalls. It is further exacerbated by inequitable access to health care, including mental

health and/or substance use disorder treatment; discrimination and exclusion of people of color, LGBTQI+

people, people with disabilities and older adults; as well as the consequences of mass incarceration. As our

nation faces the growing threats of climate change, more Americans are being displaced from their homes

and people experiencing unsheltered homelessness face even greater risk to their health and safety as a

result of climate-related crises like wildfires, floods, and hurricanes. Even as homelessness response systems

are helping more people than ever exit homelessness, more people are entering or reentering homelessness.

Homelessness has no place in America. All In: The Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End

Homelessness (herein referred to as All In) is a multi-year, interagency blueprint for a future where no

one experiences homelessness, and everyone

has a safe, stable, accessible, and aordable

home. It serves as a roadmap for federal action to

ensure state and local communities have sucient

resources and guidance to build the eective,

lasting systems required to end homelessness. While

it is a federal plan, local communities can use it

to collaboratively develop local and systems-level

plans for preventing and ending homelessness. To

reach the Biden-Harris Administration’s vision, the

plan sets an ambitious interim goal to reduce

homelessness by 25% by January 2025 and sets

us on a path to end homelessness for all Americans.

To develop this plan, USICH undertook a

comprehensive and inclusive process to

gather input from a broad range of perspectives.

Through more than 80 listening sessions and

1,500 public comments, USICH received feedback

Executive

Summary

Within this plan, USICH is using the term

“people of color” to be inclusive

4

of all racial

groups other than non-Hispanic white,

including Black/African American; American

Indian/Alaska Native; Asian/Asian

American; Latino/a; and; Native Hawaiian

or Pacific Islander. USICH acknowledges

that the experiences of each of these groups

is not the same and that the needs of each

group must be uniquely considered and

addressed upon implementation. For more

information on terms used in this plan, see

the Appendix C on Pages 88-95.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 10

from organizations and people—including more than 500 who have experienced homelessness—

who represent nearly 650 communities across nearly every state as well as tribes and territories. All of

this input directly influenced All In, which was created by USICH with collective thinking of the 19

federal agencies that make up the council.

Although All In builds o former federal strategic plans to prevent and end homelessness, it is reflective of

the Biden-Harris Administration’s priorities. It goes further than any prior USICH federal strategic plan

to comprehensively advance equity and to address systemic racism and the ways in which federal

policies and practices have resulted in severe racial and other disparities in homelessness. While other

plans have mentioned homelessness prevention, this plan includes specific strategies focused on upstream

prevention. And All In aligns with the administration’s existing work to transform social service systems—

including the National Mental Health

5

and National Drug Control

6

strategies. This plan also builds upon

the national Housing Supply Action Plan

7

that seeks to close the housing supply gap in the next five years.

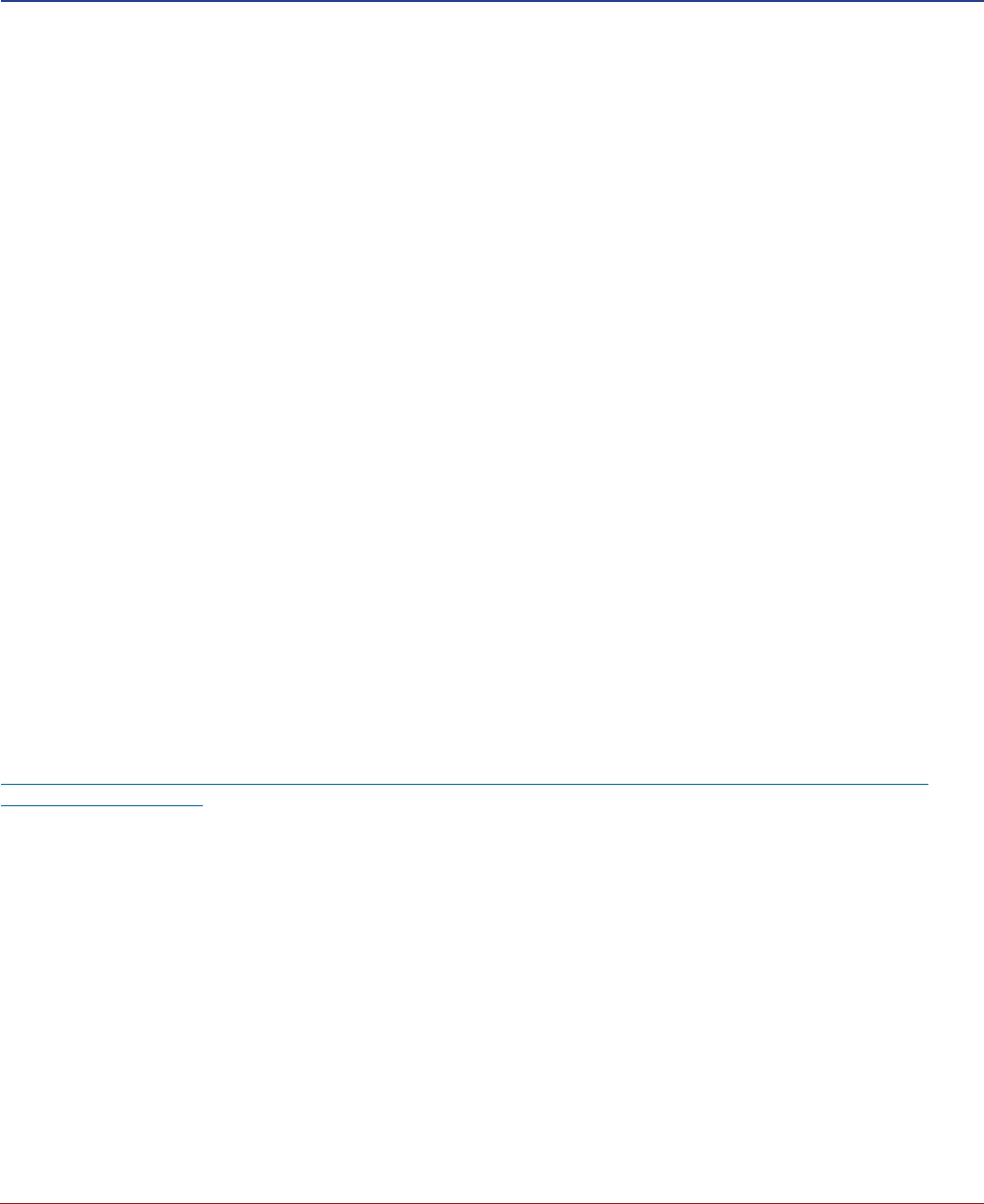

How All In: The Federal Strategic Plan (FSP) Aligns With

Other Biden-Harris Administration Work

Housing Supply Action Plan

Legislative and administrative

actions to close the housing

supply shortfall

National Mental Health

Strategy

A vision to transform how

mental health is understood

and treated

National Drug Control

Strategy

A whole-of-government call

to action to combat overdose

epidemic

FSP identifies ways to reform

zoning and land-use policies and

to reduce regulatory barriers.

See Housing & Supports

Strategy 2: Expand engagement,

resources, and incentives for the

creation of new supportive and

aordable housing.

FSP pilots new approaches,

expands pipeline of providers,

and invests in peer support

models.

See Housing & Supports

Strategy 6: Strengthen system

capacity to address and meet

the needs of people with chronic

health conditions, including

mental health conditions and/or

substance use disorders.

FSP focuses on high-impact

harm-reduction interventions.

See Housing & Supports

Strategies 6 and 7: Maximize

current resources that can

provide voluntary and trauma-

informed supportive services

and income supports to people

experiencing or at risk of

homelessness.

Ending homelessness requires an all-hands-on-deck response grounded in authentic collaboration.

Upon release of this plan, USICH will immediately begin working with federal partners as well as local

and state entities in the public and private sectors to develop implementation plans that will identify

key activities, milestones, and metrics for making, tracking, and publicizing progress. USICH will regularly

measure progress and update the implementation plans. The plan itself, All In, will be annually updated to

reflect evolving evidence, input, and lessons.

This plan is built around three foundational pillars—equity, data, and collaboration—and three

solution pillars—housing and supports, homelessness response, and prevention. Each pillar

includes strategies the federal government will pursue to facilitate increased availability of and access to

housing, economic security, health care, and stability for all Americans.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 11

Summary of All In: The Federal Strategic Plan to

Prevent and End Homelessness

FOUNDATION PILLARS

Lead With Equity

Strategies to address racial and other

disparities among people experiencing

homelessness:

1. Ensure federal eorts to prevent and

end homelessness promote equity and

equitable outcomes.

2. Promote inclusive decision-making and

authentic collaboration.

3. Increase access to federal housing and

homelessness funding for American

Indian and Alaska Native communities

living on and o tribal lands.

4. Examine and modify federal policies

and practices that may have created

and perpetuated racial and other

disparities among people at risk of or

experiencing homelessness.

Use Data and Evidence to Make

Decisions

Strategies to ground action in research,

quantitative and qualitative data, and

the perspectives of people who have

experienced homelessness:

1. Strengthen the federal government’s

capacity to use data and evidence to

inform federal policy and funding.

2. Strengthen the capacity of state and

local governments, territories, tribes,

Native-serving organizations operating

o tribal lands, and nonprofits to

collect, report, and use data.

3. Create opportunities for innovation

and research to build and disseminate

evidence for what works.

Collaborate at All Levels

Strategies to break down silos between

federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial

governments and organizations; public,

private, and philanthropic sectors;

and people who have experienced

homelessness:

1. Promote collaborative leadership at

all levels of government and across

sectors.

2. Improve information-sharing with

public and private organizations at the

federal, state, and local level.

SOLUTION PILLARS

Scale Housing and Supports That

Meet Demand

Strategies to increase supply of and

access to safe, aordable, and accessible

housing and tailored supports for people

at risk of or experiencing homelessness:

1. Maximize the use of existing federal

housing assistance.

2. Expand engagement, resources, and

incentives for the creation of new safe,

aordable, and accessible housing.

3. Increase the supply and impact

of permanent supportive housing

for individuals and families with

complex service needs—including

unaccompanied, pregnant, and

parenting youth and young adults.

4. Improve eectiveness of rapid

rehousing for individuals and families—

including unaccompanied, pregnant,

and parenting youth and young adults.

5. Support enforcement of fair housing

and combat other forms of housing

discrimination that perpetuate

disparities in homelessness.

6. Strengthen system capacity to address

the needs of people with disabilities

and chronic health conditions,

including mental health conditions

and/or substance use disorders.

7. Maximize current resources that can

provide voluntary and trauma-informed

supportive services and income

supports to people experiencing or at

risk of homelessness

.

8. Increase the use of practices grounded

in evidence in service delivery across

all program types.

Improve Eectiveness of

Homelessness Response Systems

Strategies to help response systems

meet the urgent crisis of homelessness,

especially unsheltered homelessness:

1. Spearhead an all-of-government eort

to end unsheltered homelessness.

2. Evaluate coordinated entry and

provide tools and guidance on eective

assessment processes that center

equity, remove barriers, streamline

access, and divert people from

homelessness.

3. Increase availability of and access

to emergency shelter—especially

non-congregate shelter—and other

temporary accommodations.

4. Solidify the relationship between CoCs,

public health agencies, and emergency

management agencies to improve

coordination when future public health

emergencies and natural disasters

arise.

5. Expand the use of “housing problem-

solving” approaches for diversion and

rapid exit.

6. Remove and reduce programmatic,

regulatory, and other barriers that

systematically delay or deny access

to housing for households with the

highest needs.

Prevent Homelessness

Strategies to reduce the risk of housing

instability for households most likely to

experience homelessness:

1. Reduce housing instability for

households most at risk of experiencing

homelessness by increasing availability

of and access to meaningful and

sustainable employment, education,

and other mainstream supportive

services, opportunities, and resources.

2. Reduce housing instability for

families, youth, and single adults with

former involvement with or who are

directly exiting from publicly funded

institutional systems.

3. Reduce housing instability among

older adults and people with

disabilities—including people with

mental health conditions and/or with

substance use disorders—by increasing

access to home and community-based

services and housing that is aordable,

accessible, and integrated.

4. Reduce housing instability for veterans

and service members transitioning from

military to civilian life.

5. Reduce housing instability for

American Indian and Alaska Native

communities living on and o tribal

lands.

6. Reduce housing instability among

youth and young adults.

7. Reduce housing instability among

survivors of human traicking, sexual

assault, stalking, and domestic violence,

including family and intimate partner

violence

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 12

Housing is a social determinant of health,

8

meaning lack of stable housing has a negative impact on

overall health and life expectancy. Tens of thousands

9

of people die every year due to the dangerous

conditions of living without stable housing—conditions that have worsened due to climate change and

the rise in extreme weather. For those who survive, the trauma caused by homelessness can have a lasting

impact—even after a person moves back into housing. Children who have experienced homelessness

are more likely to

10

experience serious health conditions and to become more vulnerable to abuse and

violence.

State of

Homelessness

“

Positive results can be achieved if we treat homelessness as a crisis all the time, not just during a

pandemic.

”

– Person with lived experience from San Diego, California

* https://nationalhomeless.org/category/mortality/#:~:text=People%20who%20experience%20homelessness%20have,mental%20health%2C%20

and%20substance%20abuse

11

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db427.htm#Summary

12

Microsoft Word - MemDayFlyer06.doc (nhchc.org)

13

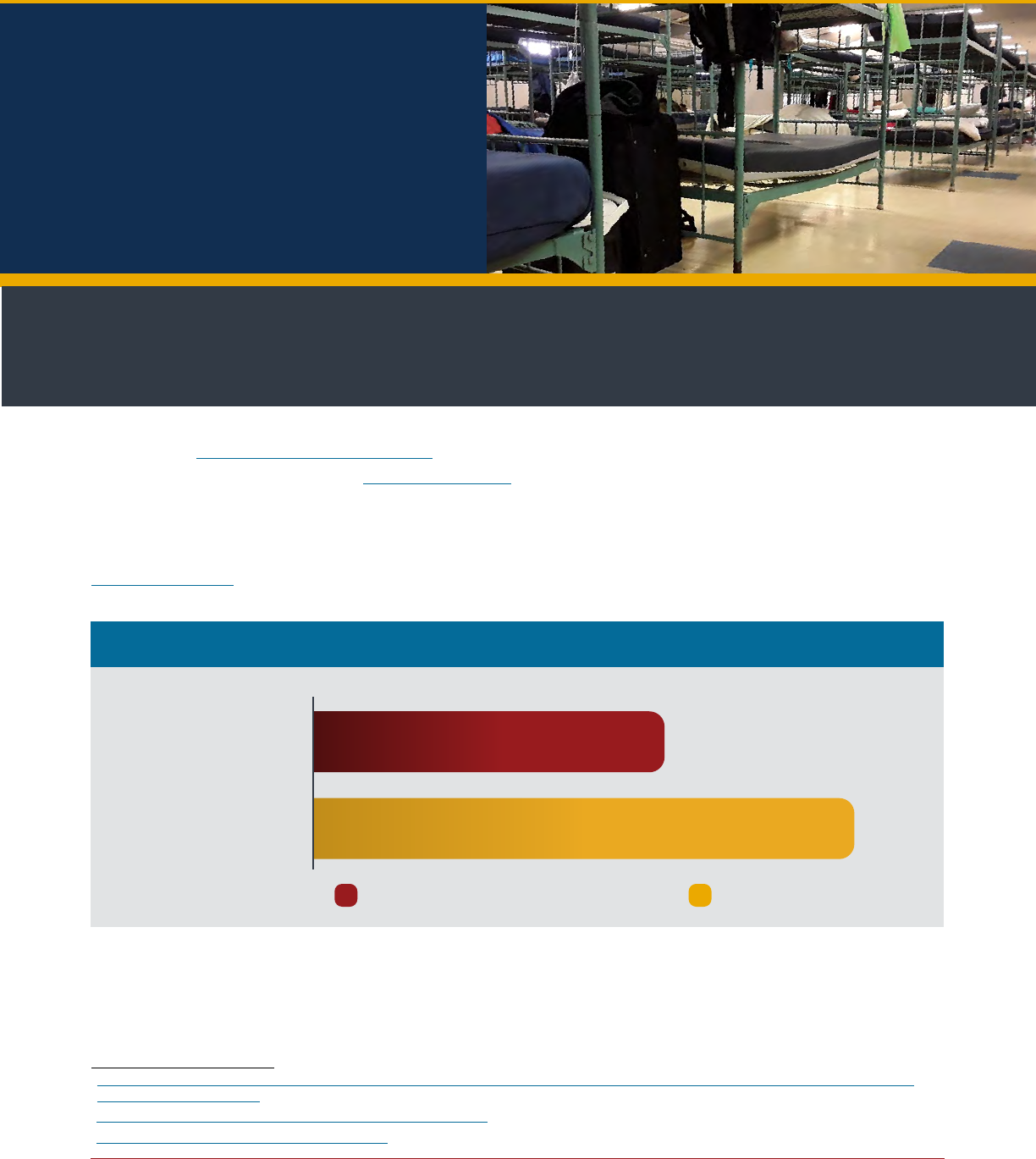

Homelessness Is Deadly

*

50 Years Old

77 Years Old

People who experience

homelessness die

nearly 30 years earlier

than the average

American—and at

the average age that

Americans died in 1900

People who experience homelessness Average American

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 13

According to HUD, on any given night, more than half a million people sleep in shelters and unsheltered

places not meant for human habitation, such as cars and encampments. But this single night datapoint

only provides part of the picture of who experiences homelessness. While some people experience it for

extended periods, most experience homelessness in shorter episodes. Over the course of a year, more than

a million individuals and families experience homelessness, and many more experience housing instability

placing them at risk for homelessness. For the first time since data collection began, more individuals

experiencing homelessness in the U.S. are unsheltered than sheltered. When considering households

that are “doubled up”—where multiple families or generations are living together out of necessity—or

households that are severely rent-burdened, the number of households experiencing homelessness or

housing instability surges even higher.

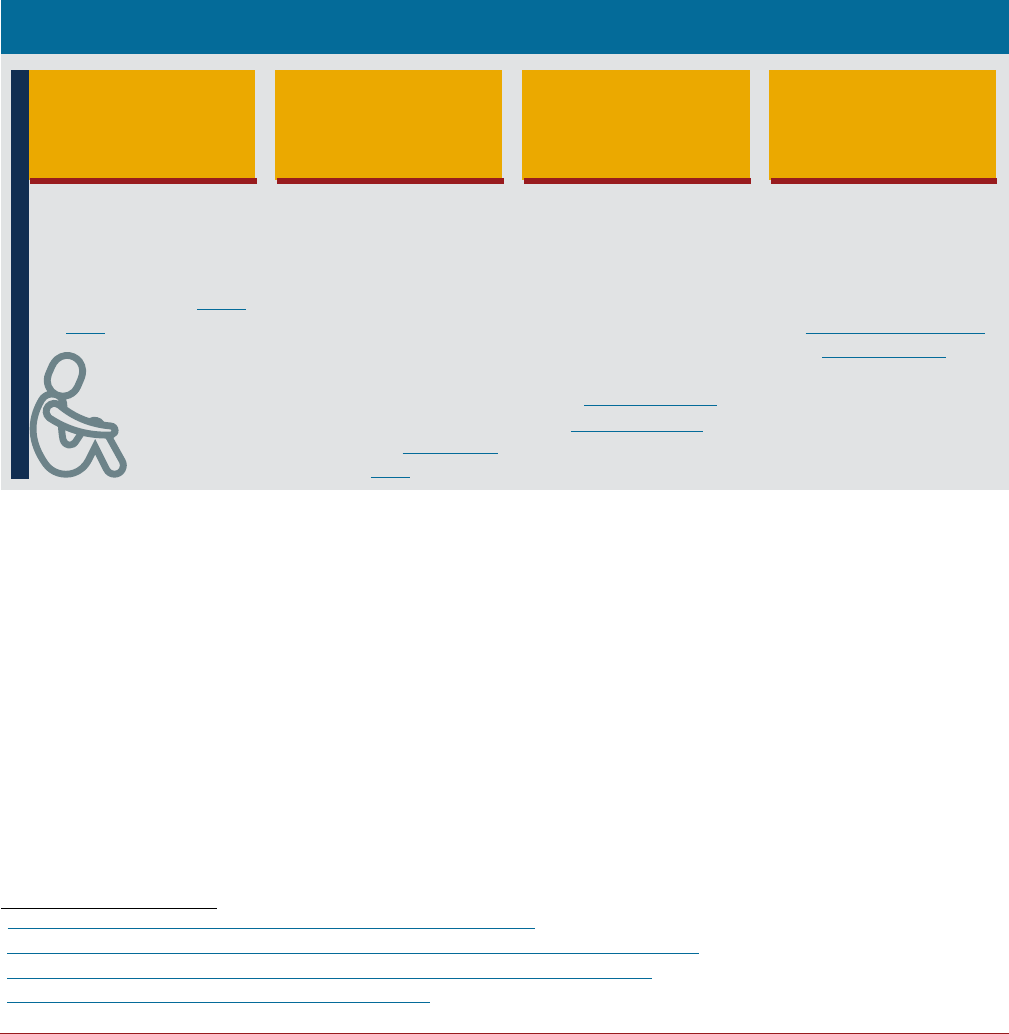

How Many People Experience Homelessness in the U.S.?*

1. 25

million

Experienced sheltered

homelessness at

some point in 2020,

the last year for which

complete annual HUD

data are available

1.29

million

People experiencing

homelessness

served by the health

center program

administered by the

Health Resources and

Services Administration

within HHS, including

Health Care for the

Homeless programs,

according to 2020 HHS

data

1.28

million

Students (not including

their parents or

siblings not enrolled

in K-12 schools)

experienced some

form of homelessness

during the 2019-20

school year, according

to Department of

Education data

582,462

Experienced

homelessness on a

single night in January

2022—a .34% increase

from 2020—according

to HUD’s annual Point-

in-Time Count

*The data in this graphic

does not reflect the

COVID-19 pandemic.

Given the pervasiveness of homelessness, most Americans—often unknowingly—have friends, family,

coworkers, or neighbors who are experiencing homelessness today or who have experienced homelessness

at some point in their lives.

*https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2020-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

14

https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/data-reporting/program-data/national/table?tableName=Full&year=2020

15

https://nche.ed.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Student-Homelessness-in-America-2021.pdf

16

https://www.hudexchange.info/homelessness-assistance/ahar/

17

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 14

“

It is time that we quit blaming

people and start blaming

bad policy that has displaced

people since the beginning of

time.

”

– Person with lived experience from

Sacramento, California

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 15

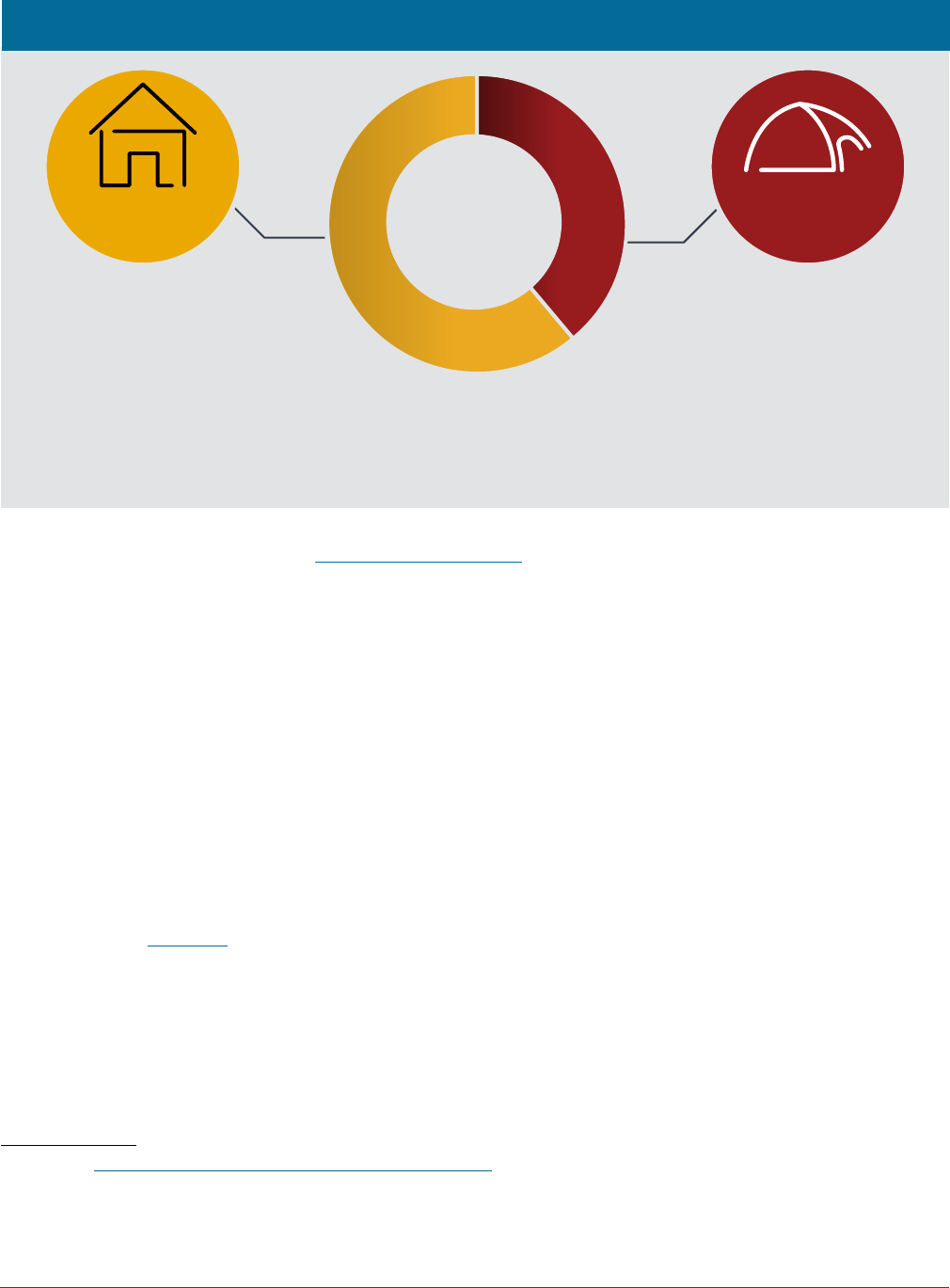

Sheltered vs. Unsheltered Homelessness

*

Portion of the total homeless

population (including

individuals and families) that is

sheltered, living in shelters or

other temporary housing

Portion of the total homeless

population (including

individuals and families) that

is unsheltered, living in cars,

streets, or encampments

While more people experiencing homelessness overall live in sheltered locations, according to the

2022 Point-in-Time Count, for only the second time since HUD started collecting this data, people who

experience homelessness as individuals (versus families) are more likely to live in unsheltered locations.

60%

40%

Homelessness in the United States has surged and receded

18

throughout our nation’s history.

**

The early

1980s marked the emergence of what now may be considered the modern era of homelessness. While

there have been many structural drivers, the evidence shows that homelessness is largely the result of

failed policies. Severely underfunded programs and inequitable access to quality education, health

care (including treatment for mental health conditions and/or substance use disorders), and economic

opportunity have led to an inadequate safety net that fails to keep individuals and families from falling

through the cracks when they fall on hard times. Underinvestment in both aordable housing development

and preservation has led to severe shortages of aordable, safe, and accessible housing. Wages have not

kept up with soaring housing costs for many working Americans, leading to persistent housing insecurity

and in some cases exacerbating poverty.

Central to many of these systemic failures are policies and programs that led to discriminatory practices

against people of color and members of marginalized groups. For example, during the 20th century, federal

and local governments implemented discriminatory housing, transportation, and community investment

policies, such as redlining,

*** 19

that segregated neighborhoods, inhibited equal opportunity and wealth

creation, and led to the persistent undervaluation of properties owned by people of color. These federal

policies eroded intergenerational wealth creation for individuals and families across the United States,

leaving many people of color more vulnerable to housing instability and homelessness. Similarly, policies

like forced relocation have put American Indians and Alaska Natives at greater risk of housing insecurity

and homelessness. At the same time, discriminatory policies and practices against marginalized groups—

such as LGBTQI+ Americans, people with disabilities, and people with HIV—have resulted in inequitable

*Data Source: https://www.hudexchange.info/homelessness-assistance/ahar/

17

** According to Kusmer (2002) and Leginski (2007), the most prominent spikes in homelessness occurred during the colonial period, pre-industrial

era, post-Civil War years, Great Depression, and today.

*** Redlining refers to a discriminatory practice in which services (financial and otherwise) are withheld from potential customers who reside in

neighborhoods classified as ‘hazardous’ to investment; these neighborhoods have significant numbers of racial and ethnic minorities, and low-

income residents.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 16

access to economic opportunity, housing security, and an inclusive social safety net.

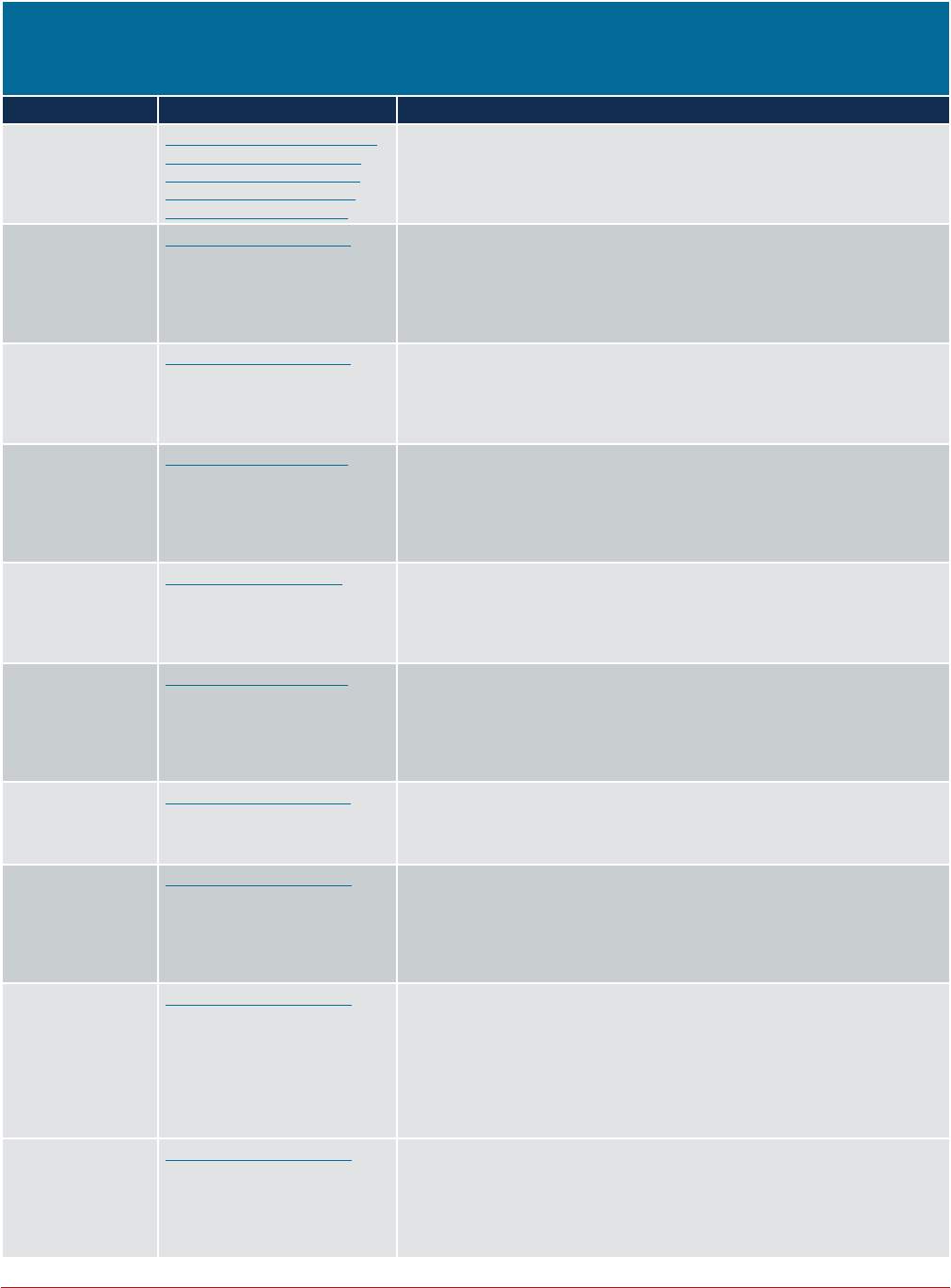

The impacts of systemic racism

20

and discrimination can be seen in federal homelessness data. While

homelessness impacts people of all ages, races, physical and cognitive abilities, ethnicities, gender

identities, and sexual orientations, it disproportionately impacts some groups and populations. Compared

to their overall proportion of the U.S. population, people of color are overrepresented in the homeless

population. Black Americans are especially overrepresented at a rate of 3 to 1 compared to the general

population. For American Indians and Alaska Natives, the ratio may be as high as 5 to 1. Latinos and

some sub-groups of Asian Americans, including Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, also experience

homelessness at high rates. Latinos, however, are routinely and drastically undercounted. Building an

ecient and eective homeless services system will require partners at all levels to understand

and address these racial disparities.

The Disproportionate Impact of Homelessness*

50.1%

37.4%

6.1%

1.4%

3.4%

1.7%

61.6%

12.4%

10.2%

6.0%

1.1%

0.2%

Non-Hispanic

White

Non-Hispanic

Black

American Indian

and Alaska

Native**

Native Hawaiian

and other

Pacific Islander

Multiple Races

Asian

Share of Population Experiencing Homelessness, 2022

Share of U.S. Population, 2020

Most people of color are

overrepresented in the

homeless population.

24.1%

18.7%

Hispanic or

Latino***

Data Sources:

* HUD 2020 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report Part 1:

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2020-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

17

U.S. Census Bureau. 2020 Census Illuminates Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Country: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/

improved-race-ethnicity-measures-reveal-united-states-population-much-more-multiracial.html

21

Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research - The Rental Assistance Demonstration; The Hispanic Housing Experience in the

United States - Understanding Low-Income Hispanic Housing Challenges and the Use of Housing and (huduser.gov)

3

** This number represents the number of individuals identified as AI/AN during the point-in-time count, which the majority of Tribes do not

participate in and is therefore a significant undercount.

*** All individuals identifying as Hispanic or Latino are included in the Hispanic or Latino category. All other categories exclude those

identifying as Hispanic or Latino.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 17

The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated homelessness, putting more people at risk of losing

jobs and homes, and putting people already living without a home at greater risk of disease and death.

People experiencing homelessness are more likely to have chronic disease, increasing their vulnerability

to COVID-19 and other

22

infectious diseases. The experience of homelessness can also make it more

challenging to access and receive necessary care, which can exacerbate homelessness and poor health

conditions.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, many agencies that provide vital supportive services and

benefits closed their oces to protect the health of employees and the public; public restrooms were

locked; and agencies faced severe sta shortages as the trauma of homeless services work intensified and

turnover increased. In the early days of the pandemic, many communities heeded the CDC’s guidance to

avoid clearing encampments. But more recently, in response to unsheltered homelessness becoming more

visible in many communities, there has been a sharp rise in the number of local laws and ordinances that

reverse course and criminalize homelessness.

The pandemic has also made it even more dicult for some to find shelter. Traditional, congregate shelters

drastically cut the number of people that could be served to comply with public health guidelines for

mitigating the spread of COVID-19. To account for that limitation, many communities have implemented

innovative solutions to expand non-congregate shelters by moving people into hotels, motels, and other

previously vacant spaces where they could socially distance from others. This expansion of non-congregate

shelter has provided an opportunity to rapidly and eectively address the needs of people experiencing

homelessness and has advanced new models that could be sustained and replicated.

“

We can never ever go back to sheltering people as we once did. Too much has changed since this

pandemic began. Congregate housing and large shelters didn’t work that well in the first place, did not

support the dignity of the homeless as people. The pandemic has shown us clearly that other ways of

securing housing—such as hotels, small transitional units, and private low-income housing units—are

essential, and more creative thinking needs to be encouraged if we are going to eliminate massive

homelessness.

”

– Person with lived experience from Portland, Maine

People with preexisting health issues are more likely to experience homelessness, and they are more

likely to live in unsheltered locations than shelters. Children who experience homelessness are more at

risk for poor health conditions and developmental delays. Health problems—coupled with lack of access

to quality health care—can contribute to risk of homelessness, and in turn, homelessness can worsen

health, including mental health conditions and/or substance use disorders. While rates of homelessness

for people with mental health

23

conditions and/or with substance use disorders are high, the majority of

people experiencing homelessness

24

do not have a mental health condition and/or substance use disorder.

Furthermore, the majority of Americans with mental health conditions and/or with substance use disorders

do not experience homelessness.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 18

Housing Is Health Care*

Asthma

22.4%

16.7%

Viral, chronic, or

acute hepatitis

29.2%

5.6%

Cerebrovascular

accident

(i.e., stroke)

4.3%

1.0%

5.7%

1.9%

Dementia

Epilepsy

10.9%

3.3%

HIV

5.8%

1.1%

Cirrhosis

7. 2%

1.9%

Tuberculosis

3.2%

0.8%

Chronic obstructive

lung disease

23.0%

10.6%

Certain health conditions are more

common among people experiencing

homelessness, who are up to 7 times

more likely to lack health insurance.

People Who Have Experienced Homelessness

General Population Sample With Similar or Same Reported Age and Gender

* Health Conditions Among Individuals with a History of Homelessness Research Brief | ASPE (hhs.gov)

25

Fact sheet (nhchc.org)

26

CoC_PopSub_NatlTerrDC_2020.pdf (hudexchange.info)

27

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 19

Through the comprehensive input process to inform the development of this plan, USICH heard about the

key challenges to implementation as well as opportunities to advance progress, which are highlighted below.

Challenges

“

Direct service providers are soul-crushingly tired. Please reach out to them. Please listen to them. They

need to know that people in power support them and want to improve the broken systems they’re

working in.

”

– Provider from Fairbanks, Alaska

Lack of Housing Supply

While housing is the solution to homelessness, the United States suers from a severe shortage of safe,

aordable, and accessible rental housing. Prior to the pandemic, there was a shortage of 7 million

28

aordable and available homes for renters with the lowest incomes. The shortage is caused by many

factors,

29

including a shortage of available land and labor, increased costs of raw materials, local zoning

restrictions, land-use regulations, opposition to inclusive development—which is commonly referred to as

“Not In My Back Yard” (NIMBY), and the destruction of homes in climate change’s path. Compounding

this, people with housing vouchers or other rental assistance compete for limited housing in a highly

competitive rental market, and they often face stigma, barriers, and/or discrimination from landlords. In

addition, many landlords deny housing to people based on their criminal records and/or credit history.

And many renters of color, LGBTQI+ renters, and renters with disabilities continue to face outright

discrimination when they apply for housing. The lack of accessible housing for some people with

disabilities further complicates the situation.*

Rise of Rent Amid Slow Wage and Income Growth

Wage growth has been slow for the lowest-paid workers for decades, and for many Americans, rental

housing is unaordable because wages have not kept up with the fast rise of rent. According to a 2021

report, in no state

30

can a person working full-time at the federal minimum wage aord a two-bedroom

apartment at the fair market rent. As a result, 70% of the lowest-wage households routinely spend more

than half of their income on rent, placing them at risk of homelessness if any unexpected expenses or

emergencies arise. Housing unaordability disproportionately impacts people with disabilities, LGBTQI+

people, and people of color. Discriminatory employment practices toward these groups further contribute

to these disparities. Similarly, there is no housing market within the U.S.

31

in which a person living solely

on Supplemental Security Income (SSI) can aord housing without rental assistance.

Challenges and Opportunities

* The American Housing Survey of 2011 found that less than five percent of housing in the U. S. is accessible for individuals with moderate

mobility diculties and less than one percent of housing is accessible for wheelchair users. Accessibility of America’s Housing Stock: Analysis of

the 2011 American Housing Survey (AHS) | HUD USER

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 20

Inadequate Access to Quality Health Care, Education, and Supportive Services

“Low-barrier,” culturally appropriate, readily available, and accessible supportive services—including

treatment for mental health conditions and/or substance use disorders—often are not available or funded

at a level to meet the need. This is particularly true in rural areas. As a result, people seeking these services

may face long waits or may not receive them at all, and service providers may only be reimbursed for a

fraction of the cost of care. Furthermore, collaboration and coordination between homelessness response

and other systems—including health, victim services, workforce development, aging- and disability-

related services, early care and education,*

32

K-12 and higher education—is often not as strong as it

could be, creating silos in service delivery. People of color, especially Black people and other marginalized

populations face greater barriers

33

to receiving the supports they need, which leads to severe health

inequities and disparities in health outcomes.

Limited Alternatives to Unsheltered Homelessness

The number of people living in unsheltered locations is rising, yet there are often not enough safe,

low-barrier shelter or interim housing options for people waiting for permanent housing and support.

Many shelters are full or deny entry to people who are struggling with a mental health condition and/

or who have a substance use disorder, have criminal records, live with a disability or chronic condition,

or identify as LGBTQI+—despite regulations that prohibit this discrimination. People who have

disabilities, pets, partners, or older children (especially male teenagers) have fewer options for sheltering

together. Additionally, shelters often fail to meet the needs of people either because they are not culturally

appropriate or do not have the capacity to provide adequate support and accommodations for people with

significant physical disabilities, mental health conditions and/or substance use disorders. As unsheltered

homelessness increases in some communities, the impact on surrounding neighborhoods has eroded

support for further investments in homeless services.

Criminalization of Homelessness

In some communities, a rise in encampments has resulted in harmful public narratives and opposition to

development of aordable housing and programs that serve people experiencing homelessness. As elected

leaders respond—and not always in the most eective ways—some have resorted to clearing encampments

without providing alternative housing options for the people living in them. Many communities have made

it illegal for people to sit or sleep in public outdoor spaces or have instituted public space design that makes

it impossible for people to lie down or even sit in those spaces. Unless encampment closures are conducted

in a coordinated, humane, and solutions-oriented way that makes housing and supports adequately available,

these “out of sight, out of mind” policies can lead to lost belongings and identification which can set people

back in their pathway to housing; breakdowns in connection with outreach teams, health care facilities, and

housing providers; increased interactions with the criminal justice system; and significant traumatization—

all of which can set people back in their pathway to housing and disrupt the work of ending homelessness.

*Early care and education includes child care, Head Start, home visiting and preschool

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 21

Trauma and Fatigue Among Providers

The pandemic has strained the capacity of service providers—many of whom earn wages low enough

to qualify them for the programs they help administer. Even before the pandemic, housing and service

programs had high sta turnover. These essential workers provide life-saving crisis services while dealing

with stang shortages, navigating evolving guidance for protecting themselves and their clients, and doing

their best to implement best practices and quickly deploy new federal funding. Many are overwhelmed and

exhausted from the pressure and trauma associated with supporting not only the people they serve but

also themselves and their families during a sustained global pandemic.

Opportunities

“

When there is adequate funding and community will to do something, a large dierence can be

made.

”

– Person with lived experience from San Diego, California

Unprecedented Investment of New Funding

The American Rescue Plan—along with the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES)

Act—provides billions of dollars for new and existing programs that can move people into housing

and increase the availability of housing and housing subsidies. Section 2001 of the ARP

34

also created

new funding to directly connect students experiencing homelessness with educational and wraparound

supportive services. These resources provide communities with a historic opportunity to innovate and

improve existing systems. Moreover, President Biden’s budget request for Fiscal Year 2023 includes

significant increases in funding for targeted programs, vouchers, and Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, as

well as new funding to increase the aordable housing supply.

Demonstrated Commitment Through Regulatory Flexibility and Executive

Action

The CARES and American Rescue Plan Acts created regulatory flexibilities that spurred greater

innovation, strengthened partnerships, and created new collaborations. Furthermore, the Biden-Harris

Administration has taken critical action to address the challenges outlined in the previous section.

President Biden has issued several executive orders focused on bold and ambitious steps to root out

inequity within the economy and to expand opportunity for people of color and other marginalized

groups. The White House has also initiated whole-of-government action plans and strategies that address

the nation’s most pressing needs, such as the Housing Supply Action Plan,

7

the National Mental Health

Strategy,

5

and the National Drug Control Strategy.

6

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 22

Many communities are using

American Rescue Plan funds

to convert vacant hotels and

motels into non-congregate

shelters.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 23

Lessons Learned From the Pandemic

COVID-19 has spurred a sense of urgency and innovation across government to keep people safe and

healthy. Federal programs have found ways to rapidly waive requirements that were impeding mitigation

and recovery. As a result, new partnerships have been created and new approaches have emerged,

including the conversion of previously vacant hotels to non-congregate shelter and housing; expansion

of unemployment benefits; use of eviction moratoriums; launch of emergency rental assistance; and

provision of direct cash transfers. The expansion of non-congregate shelter, in particular, and the greater

coordination among public health, health care, aging and disability network organizations, and other

supportive services has provided an opportunity to improve housing stability and health outcomes.

Increased Focus on Racial Equity

The murder of George Floyd during an encounter with law enforcement in 2020 sparked greater awareness

of historic and ongoing racism—especially anti-Black racism—and its impact. A nationwide discourse on

racial justice ensued, demanding urgent change and accountability at all levels of government in public

policies and programs that either intentionally or unintentionally perpetuate racism. Since then, awareness

of racial disparities has risen, along with eorts to correct these inequities, at all levels of government and

in the homelessness sector. While homelessness impacts people of all races, ethnicities, gender identities,

and sexual orientations, it disproportionately impacts some groups and populations, particularly people

of color, and especially Black people. This increased focus, as well as the Biden-Harris administration’s

commitment to a whole-of-government approach to advancing equity, provides an opportunity to hold

federal, state, and local governments accountable for achieving more equitable outcomes for people of

color.

Dedication of Providers

The homeless services sector is comprised of many passionate and compassionate people—many of whom

are volunteers—who dedicate every day of their lives to the work of preventing and ending homelessness in

their communities. This work is dicult under any circumstances, and the pandemic made it exponentially

more dicult. But people continue to show up, persevering through the toughest circumstances.

The following plan oers a roadmap to bring renewed energy to address these challenges and make the

most of these opportunities.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 24

This plan is built upon our vision of a nation in which no one experiences the tragedy and

indignity of homelessness, and everyone has a safe, stable, accessible, and aordable home.

We envision a future where every state and community have the systems and the resources to prevent

homelessness whenever possible, or if it cannot be prevented, to quickly connect people experiencing

homelessness to permanent housing with the services and supports they need to help them achieve and

maintain housing stability.

Achieving this vision for the future will require the transformation of systems and institutions that displace

and exclude people from housing.

National Goal

This plan sets the United States on a path to end homelessness and establishes an ambitious national

goal to reduce the number of people experiencing homelessness by 25% by January 2025.* Such a

reduction will serve as a down payment on the longer-term work of ending homelessness once and for all.

Achieving this ambitious national goal is the responsibility of all public systems in partnership with the

private sector and philanthropy—not the homelessness response system alone. It will require a whole-of-

government, cross-system approach to implement. We encourage state and local governments—in

collaboration with people who have experienced homelessness and with local organizations

working to end homelessness—to establish their own, more ambitious goals for 2025.

In the months ahead, USICH will provide guidance on setting local goals and measuring local progress.

It will also provide additional metrics, equity outcomes, and other federal data targets that can be

monitored to measure progress toward the national reduction goal. In the meantime, the Framework for

Implementation on Pages 70-71 can serve as a reference.

Vision for

the Future

* This goal reflects a projected 25% reduction in total overall homelessness in the 2025 Point-in-Time count compared to the 2022 Point-in-Time

count. In January 2022, the total number of people experiencing homelessness on a single night was 582,462. A 25% reduction would mean fewer

than 437,000 people will be counted on a single night in January 2025.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 25

Key Populations and Geographic Areas

This plan recognizes that the needs of people experiencing homelessness vary based on factors like age,

location, disability, race and ethnicity; and it acknowledges that tailored guidance will be needed for key

populations and geographic areas. For the purposes of this plan, this includes:

Racial/Ethnic Groups (“People of Color”)

• American Indians and Alaska Natives

• Asian/Asian Americans

• Black/African Americans

• Hispanics/Latinos

• Multiracial people

• Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders

Marginalized Groups

• Child welfare-involved families and youth

• Immigrants, refugees, and asylees

• LGBTQI+ people

• People with chronic health conditions and co-

occurring disorders

• People with current or past criminal justice

system involvement

• People with disabilities

• People with HIV

• People with mental health conditions

• People with substance use disorders

• Pregnant and parenting youth

• Survivors of domestic violence, stalking, sexual

assault, and human traicking

Subpopulations

• Children (younger than 12)

• Youth (age 12-17)

• Young adults (age 18-25)

• Families with minor children

• Older adults (age 55 and older)

• Single adults (age 25 to 55)

• Veterans

Geographic Areas

• Remote

• Rural

• Suburban

• Territory

• Tribal land/Reservation

• Urban

As the strategies outlined in this plan are implemented, USICH will work with a broad range of stakeholders

to adopt a “targeted universalism”

35

framework that promotes a universal reduction goal with targeted and

tailored solutions based on the structures, cultures, and geographies of certain groups to help them overcome

unique barriers. USICH recognizes that tailored solutions are needed for specific populations and geographic

areas and that individuals and families experiencing multiple barriers often require special consideration and

resources. USICH also recognizes that the federal government will need to rely on those most impacted by

the policies and strategies promoted in this plan to design the tailored actions and guidance.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 26

All In serves as a roadmap for federal action to ensure state and local communities have sucient

resources and guidance to build the eective, lasting systems required to end homelessness. While it is

a federal plan, local communities can use it to collaboratively develop local and systems-level plans for

preventing and ending homelessness. This plan creates an initial framework for meeting the ambitious

goal of reducing overall homelessness by 25% by 2025 and sets the United States on a path to end

homelessness.

This plan is built around six pillars: three foundations—equity, evidence, and collaboration—and three

solutions—housing and supports, homelessness response, and prevention—all of which are required to

prevent and end homelessness. Within each pillar of foundations and solutions are strategies that the

federal government will pursue to facilitate increased access to housing, economic security, health, and

stability. Some agency commitments, cross-government initiatives, and eorts are already underway and are

highlighted throughout.

Upon release of this plan, USICH will immediately begin to develop implementation plans that will

identify specific actions, milestones, and metrics for operationalizing the strategies in close partnership

with its member agencies and other stakeholders representing a broad range of groups and perspectives,

including people with lived experience. For more on this, please see Framework for Implementation on

Pages 70-71.

Federal

Strategic

Plan

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 27

FOUNDATIONS

ALL IN: THE FEDERAL STRATEGIC PLAN:

EQUITY DATA AND

EVIDENCE

COLLABORATION

PREVENTION

CRISIS RESPONSE

HOUSING AND SUPPORTS

SOLUTIONS

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 28

As detailed earlier, discrimination in housing, education, employment, criminal justice, and health care have

led to inequitable access to wealth and economic opportunity and to a greater likelihood of experiencing

homelessness. To acknowledge and address these and other inequities, the following strategies and actions

are intended to ensure that the solutions in this plan will be designed and implemented equitably.

Strategy 1: Ensure federal eorts to prevent and end homelessness promote

equity and equitable outcomes.

In recent years, the homelessness sector has increasingly focused on equity and inclusivity. To achieve

equity, we must build o the work already underway through President Biden’s Executive Order on

“Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government”

and take additional steps to armatively advance equity, civil rights, racial justice, and equal opportunity.

To accomplish this strategy, USICH and relevant member agencies will:

• Identify expected equity outcomes with qualitative and quantitative measures and plans for how

programs and agencies responsible for carrying out strategies and actions included in this plan will

collect and report on the information used to measure these outcomes.

• Establish tools and processes for identifying, analyzing and updating agency-specific policies,

practices, and procedures for programs and agencies responsible for carrying out strategies and

actions included in this plan that may inhibit opportunity to advance and promote equity.

• Create a mechanism to publicly report federal actions taken by USICH and its member agencies to

advance equity and support local and state eorts to address disparities.

• Provide messaging and guidance to state and local stakeholders about promising practices that are

having a measurable impact on disparities.

• Ensure all guidance, tools, and websites are designed to be accessible and to ensure eective

communication for people with disabilities; and take steps to ensure meaningful access for people

with limited English proficiency.

• Create learning opportunities across USICH and its member agencies on racial equity, cultural

competence, cultural humility, and disability competence.

• Hire people and partner organizations with a strong equity analysis to inform actions taken under

this strategy.

“

Anti-Black racism continues to be ignored as a root cause of homelessness, and Black people

experiencing homelessness continue to be inadequately protected from housing discrimination,

over-policing, criminalization of poverty, and other systemic forces that contribute to their

overrepresentation in the total population of people experiencing homelessness.

”

– Advocate from Washington, District of Columbia

Lead With Equity

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 29

Strategy 2: Promote inclusive decision-making and authentic collaboration.

It is critical that people who have experienced or who are experiencing homelessness and housing

instability lead and participate in the development and implementation of policies and programs. This

includes not only people of color but other historically marginalized groups that are overrepresented in

homeless populations, especially people identifying as LGBTQI+ and people with disabilities.

To accomplish this strategy, USICH and relevant member agencies will:

• Identify existing federal advisory groups, committees, and workgroups that are focused on preventing

and ending homelessness and seek ways to expand membership to include people with lived

experience and for ensuring meaningful participation and compensation for their time and expertise.

• Review federal processes and administrative requirements for contractors that deliver relevant

technical assistance (TA) and capacity-building related to implementation of the strategies within

this plan to allow for an expanded pool of selected contractors and firms with higher diversity of sta

and management and/or people with lived experience.

• Identify ways to conduct accessible outreach to and hire people with lived experience in federal

job announcements for programs and agencies responsible for carrying out strategies and actions

included in this plan.

• Allow for and incentivize inclusive processes that allow for meaningful engagement in all federal

funding grants that directly impact people at risk of or experiencing homelessness.

• Create flexibilities in existing federal programs to encourage funding recipients that serve people at

risk of or experiencing homelessness to hire people with lived experience and compensate them on

par with other sta.

• Create flexibilities in existing federal programs to allow recipients to use program funds to

compensate people with lived experience participating on local advisory councils.

How People With Lived Experience Can Shape Policy

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 30

• Examine barriers such as federal program caps on earned income and explore opportunities to

provide flexibilities for people with lived experience to be compensated for their participation in

planning activities and input processes without risking any benefits or assistance that they receive

from the federal government.

• Incentivize, strengthen, and expand opportunities for professional development and mentoring

focused on supporting people with lived experience as they take on new types of roles, especially

leadership roles.

• Create learning opportunities across USICH and its member agencies on creating environments that

will allow people with lived experience to thrive and not be retraumatized.

Strategy 3: Increase access to federal housing and homelessness funding for

American Indian and Alaska Native communities living on and o tribal lands.

Although tribes have exercised inherent sovereignty over their lands, AI/AN communities continue to face

unique challenges today—including federal disinvestment in basic infrastructure, severe housing shortages

that lead to dangerous overcrowding, and complex legal constraints related to land ownership. These

challenges make it extremely dicult to improve housing conditions. Solutions to these challenges must

be developed and designed through consultation and in partnership with tribes and must be culturally

appropriate and adaptive to the unique circumstances of AI/AN communities living on and o tribal lands.

To accomplish this strategy, USICH and relevant member agencies will:

• In accordance with Executive Order 13175 and the Presidential Memorandum on Tribal

Consultation and Strengthening Nation-to-Nation Relationships,

36

build upon the tribal

consultation that took place to inform the development of this plan and further consult tribes on

strategies and solutions that will impact housing instability and homelessness for American Indian

and Alaska Native communities living on and o tribal lands.

• Explore opportunities to expand Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act

programs (the primary vehicle for developing housing in tribal land).

• Promote and expand opportunities to hire more AI/AN people across agencies responsible for

carrying out strategies and actions included in this plan.

• Coordinate a federal TA strategy to support eorts of tribes and Native-serving organizations

operating o tribal land to address homelessness and increase access to funding streams that are

newly available to tribes.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 31

Strategy 4: Examine federal policies and practices that may have created

and perpetuated racial and other disparities among people at risk of or

experiencing homelessness.

“

Inequitable access is rooted from the top down. The federal government must be tasked with

recognizing and ALLOWING FOR the undoing of systemic and institutional discrimination that

PERMEATES its systems.

”

– Person with lived experience

Policies and practices that may be intended to promote racial neutrality sometimes inadvertently led

to worse housing outcomes for people of color. Our collective response to homelessness should advance

policies and practices specifically designed to eliminate racial inequities in homelessness and housing.

To accomplish this strategy, USICH and relevant member agencies will:

• Partner with the agencies responsible for carrying out the strategies and actions within this plan

and review policies and regulations associated with the federal programs and initiatives to assess

whether and how current policies and programs may perpetuate racial disparities or create barriers

for marginalized groups and people of color and identify achievable policy and program changes to

advance equity.

• Develop tools and provide direct TA to help grantees, states, local governments, and U.S. territories

to implement equitable policies and practices and build the capacity of organizations to serve

people of color and marginalized groups who face current and historic discrimination based on race,

disability, class, and gender identity.

• Highlight communities that achieve reductions in racial and other disparities, and create tools,

products, and guidance based on their strategies.

Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness 32

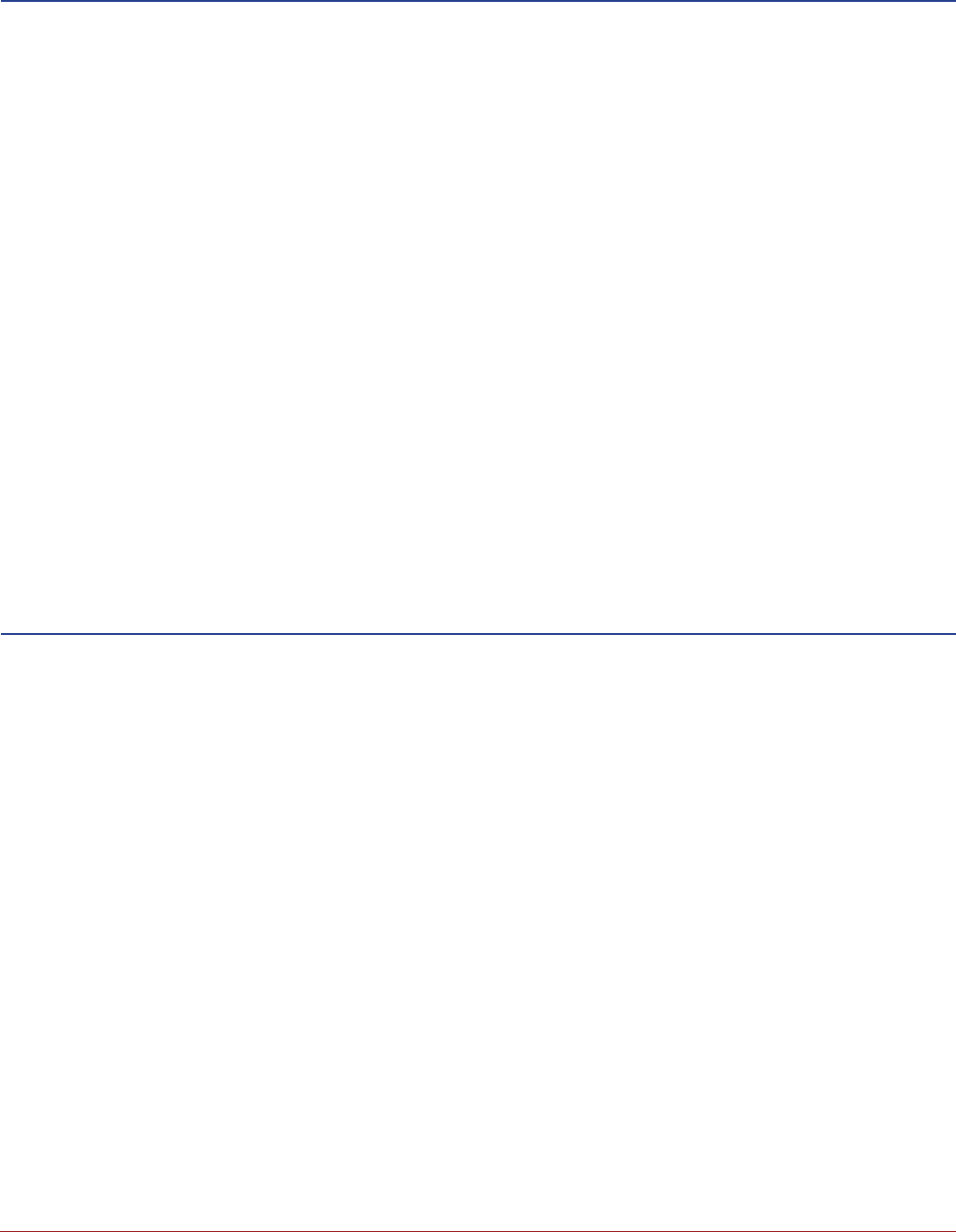

Recent Biden-Harris Administration Actions

to Lead With Equity

Agency/Entity Policy/Program/Initiative Action

White House

Memo on “Redressing Our

Nation’s and the Federal

Government’s History of

Discriminatory Housing

Practices and Policies”

Issued to Secretary of HUD to declare that the Biden-Harris Administration

will work to end housing discrimination and ensure equitable access to

housing for all

White House

Executive Order 13985:

Advancing Racial

Equity and Support for

Underserved Communities

Through the Federal

Government

Established policy of Biden-Harris Administration to pursue comprehensive

approach to equity for all, including people of color and others who have

been historically underserved, marginalized, and adversely aected by poverty

and inequality

White House

Executive Order 13988:

Preventing and Combating

Discrimination on the Basis

of Gender Identity or Sexual

Orientation

Established policy of Biden-Harris Administration to address overlapping forms

of discrimination, to prevent and combat discrimination on the basis of

gender identity or sexual orientation, and to fully enforce Title VII, the Fair

Housing Act, and other laws that prohibit such discrimination

White House

Executive Order 14008:

Tackling the Climate Crisis

Abroad and at Home

Established policy of Biden-Harris Administration to address the climate

crisis proactively and includes the development of the Justice40 Initiative,

which seeks to ensure that disadvantaged communities receive 40% of any

investments made in areas such as clean energy and energy eiciency;

aordable and sustainable housing; and the development of critical clean

water infrastructure

White House

Executive Order 14020:

Establishment of White

House Gender Policy

Council

Established policy of Biden-Harris Administration to ensure that the federal

government is working to advance equal rights and opportunities,

regardless of gender or gender identity, in advancing domestic and

foreign policy, and to prevent and address gender-based violence in the

United States

White House

Executive Order 14031:

Advancing Equity, Justice,

and Opportunity for

Asian Americans, Native

Hawaiians, and Pacific

Islanders

Established President’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans, Native

Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders as well as the White House Initiative on Asian

Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders

White House

Executive Order 14035:

Diversity, Equity, Inclusion,

and Accessibility in the

Federal Workforce