International Journal of Communication 3 (2009), 307-331 1932-8036/20090307

Copyright © 2009 (Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon). Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Non-

commercial No Derivatives (by-nc-nd). Available at http://ijoc.org.

Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica

The Homogenization of Content and Americanization

of Jamaican TV through Programme Modeling

NICKESIA STACY ANN GORDON

Barry University

There is a great deal of discussion about the globalization of media, particularly

television, especially as it is being driven by the spread of satellite technology and cable.

While certain scholars view this as promoting cultural heterogeneity and the

diversification of programme content, others see this trend as a proliferation of the

homogenization of programme content and American popular culture. The paper

investigates the relevance of the two above perspectives within the Jamaican media

context. By conducting informant interviews, as well as a programme analysis of content

aired on local television stations, the research reveals that the cultural imperialism

perspective remains quite relevant, as is evidenced through the modeling of

programming originating predominantly in the United States of America.

Key words: Jamaica, Content homogenization, Cultural imperialism, Programme

modeling, Jamaican television, Globalization, Media privatization

Introduction

The phenomenon of globalization has spawned myriad developments in a number of arenas,

namely the social, political, economic, and cultural. As an industry that is inextricably linked to all four

spheres just mentioned, the media has witnessed tremendous changes under the auspices of

globalization. These changes have primarily been facilitated through privatization initiatives engendered

by the economic paradigm of market liberalization, ushered in by globalization. As part of the adjustment

to market liberalization imperatives, the media has been reinvented on the political and economic front

through massive mergers, giving birth to the term ‘media globalization’ and the business entities known

as transnational corporations (TNCs). Socially and culturally, the reinvention of the industry has intensified

old debates and given rise to new questions. One of these debates is the relationship between media and

cultural imperialism, and one of these questions pertains to the relationship between private media and

content diversity.

Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon: [email protected]

Date submitted: 2007-11-15

308 Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon International Journal of Communication 3(2009)

On a global scale, there has been a lot of discussion about the globalization of media, particularly

television, as it is being driven by the spread of satellite technology and cable. Certain scholars such as

Tomlinson (1991), Sinclair (2004), and Waisbord (2004) view this as promoting cultural heterogeneity and

the diversification of programme content. However, others such as McChesney (2004; 2005), Mody

(2000), and Schiller (1991; 1996) see this trend as proliferating the homogenization of programme

content and American popular culture. In Jamaica during the 1970s and 1980s, research on international

programme flow (Brown, 1979; Dunn, 1988) concurred with the latter perspective, repeatedly pointing

out and confirming the dominant position of the American audiovisual industry on Jamaican television.

Since then, Jamaica’s predominantly state-owned media have been deregulated, resulting in increased

private ownership of media entities. How has this shift influenced international programme flow on

Jamaican television, and has privatization lead to the diversification of content as proposed by the

proponents of a free market system?

In an effort to extend the studies mentioned formerly and locate the current state of Jamaican

television media within the globalization discourse, this paper questions whether or not the increased

private ownership of television media in the country and the rising influence of globalization on the

industry during the 1990s and onward signify a continued cycle of one-way television flow from the United

States. This is a relevant question given the argument that privatization will augment political and cultural

diversity in the media sphere by delinking mass communications from the state and placing it in the hands

of private owners, the latter supposedly being better guardians of free speech and a free press. The

contention that private media will best facilitate and encourage diversity in content is premised on the

assumption that these entities have an inherent economic incentive to give the people what they want. If

not, audiences would simply tune out and media organizations would simply lose money. Whether or not

this promise has been lived up to in the Jamaican context is highly debatable and warrants some

exploration, both from a cultural as well as socio-political perspective.

This paper focuses on these issues as they relate to television. This is because, in Jamaica,

television is perhaps the medium most affected and transformed by globalization. It is also the medium

most deeply implicated in facilitating globalization as a cultural process (Sinclair, 2004, p. 69).

Specifically, the paper examines the programming of Jamaica’s three national television stations, namely

Television Jamaica (TVJ), CVM Television (CVMTV), and Love Television (LOVETV). Based on a

programme analysis of content aired on these stations, as well as interviews conducted with Jamaican

media practitioners, both from the private and public sector, the paper concludes that a one-way flow of

information and cultural goods from more industrialized countries such as the United States to Jamaica

persists in more nuanced ways. There is a strong tendency toward content homogenization and

programme modeling on all three stations and a strong economic bias toward content originating in the

United States in the industry overall. These may very well be new forms of cultural imperialism

precipitated by media privatization and the accompanying economic model of a market-oriented media

management style. After giving a brief background to Jamaica’s television media, as well as the context

within which privatization of television occurred, the paper delineates the competing arguments of the

cultural imperialism and cultural hybridity perspectives. The latter contextualizes the paper’s argument

that content homogenization and programme modeling on Jamaican television constitute trends that

International Journal of Communication 3 (2009) Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica 309

resonate with the cultural imperialism thesis. Cultural proximity, an extension of the cultural hybridity

thesis, is also examined as it relates to Jamaican television, revealing that even as Jamaicans prefer to

watch programmes that are reflective of their cultural or local orientation, what passes for local production

is merely a localized version of American popular culture.

Background to Jamaican Television Media

At present, the Jamaican media are privately owned. Most of these privately owned stations burst

onto the scene in the late 1990s after the changes in media regulation allowed private entrants into the

media sphere. Prior to 1990, the airwaves were dominated by primarily two rival stations, the Jamaica

Broadcasting Corporation Radio and Television (JBC) and Radio Jamaica (RJR). The former was

government-owned, while the latter was a privately owned competitor. RJR was Jamaica’s first commercial

broadcasting station and began operations in May 1940 as a radio entity (Virtue, 2001, p. 12). Today,

RJR, or the RJR Communication Group as the entity is now known, is the largest media entity in Jamaica,

owning three of the island’s 16 radio stations, as well as the largest of the island’s three television

stations.

There are three national television stations, Television Jamaica (TVJ), formerly JBCTV; CVM

Television (CVMTV); and Love Television (LOVETV). TVJ is the largest and oldest of the three and began

its operations as JBCTV in 1963. In 1993, CVMTV came onto the scene as a competitor to the then-

government-owned JBCTV with a mandate to fulfill a 50/50 balance between local and imported

programming (Virtue, 2001, p. 13). LOVETV followed later in 1998, and it provides religious programming

for a Christian demographic. Subscription Cable Television (STV) provides access to a range of

programming from North America to local subscribers, and at times, operators produce their own in-house

programming which airs on community channels. The government’s voice is represented by the Jamaica

Information Service Television (JISTV), and it does not have direct broadcast capacity. JISTV programmes

receive airtime on the other three stations during time mandated for government broadcast.

Literature Review: Issues of Privatization and Media

Privatization, in the sense that it is used by the World Bank and IMF in reference to developing

countries, entails converting state-owned and -operated industries and firms into private ones (Stiglitz,

2003, p. 54). It is based on the belief that private firms can perform certain government (business)

functions more efficiently. It is the hand maiden of the global economic paradigm, market liberalization,

which paves the way for the removal of government “interference” in financial markets, capital markets,

and barriers to trade. This conception/application of privatization constitutes what Audenhove, Burgelman,

Nulens, and Cammaerts (1999, p. 388) refer to as the “dominant scenario,” which informs the framework

that guides development in so called “Third World” states.

Based on two macro-economic assumptions, that 1) competition on all levels is a precondition for

economic growth, no matter the context, and 2) interventions by public authorities — the state — have

310 Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon International Journal of Communication 3(2009)

restraining rather than enabling effects on economic growth and prosperity (Audenhove, Burgelman,

Nulens, and Cammaerts, 1999, p. 389), privatization was viewed by international financial institutions

such as the WB and IMF as the way to achieve development goals in developing countries. It was seen as

a tool for reforming the public sector in developing countries where the operations of public entities were

presumed to be (and rightly so in some instances) inefficient and inimical to economic growth.

Subsequently, between 1988 and 1993, approximately 2,700 public enterprises in more than 60

developing countries were transferred to private ownership (Turner & Hulme, 1997, p.190), most

occurring as conditions to acquiring international loans from the above-mentioned institutions.

Privatization of “Third World” economies therefore opened up the floodgates of competition nationally, but

more importantly, internationally, from competing enterprises in a wide range of goods and services.

In the telecommunications sector, liberalization of the industry at the international level and the

direction in which it will go have both been secured by the WTO, which, in an agreement between 130

countries, treats telecommunication as a service. This agreement was secured under the General

Agreement in Trade and Services (GATS) during the 1994 Uruguay Round of international trade

negotiations and came into effect in January 1995 (http://www.wto.org). The GATS establishes a set of

multilateral rules covering international trade in services wherein negotiations concerning said trade “shall

take place with a view to promoting the interests of all participants on a mutually advantageous basis” and

“with due respect for national policy objectives and the level of development of individual members”

(http://www.wto.org). However, outside of its formal declarations, the GATS operates to secure the

dominance of industrialized societies by developing “a stringent international system of intellectual

property rights protecting the technologies of transnational enterprises” (Rivero, 2001, p. 49). This means

that communication products can largely be treated as cultural goods because the lines between digital

services and cultural products have been somewhat blurred. Accordingly, countries will have little to no

rights in establishing cultural rights or protective measures over cultural goods. International trade

agreements perceive such independent cultural policies as unfair barriers to trade (Hamelink, 2003, p. 8).

Regarding communications, privatization of the industry is seen to be beneficial for the public

good as it restricts government monopoly of information and ensures plurality in the public sphere

(Sinclair, 2004, p. 79). Thus, where national governments attempt to apply measures of control over their

media industries, they are seen as contravening WTO/international legislation. The WTO has gained

enormous importance in managing communications networks and in regulating the circulation of cultural

goods (Neveu, 2004, p. 332). Consequently, the pertinence of the nation-state as the analytical unit of

economic and legal media regulation appears more and more doubtful (Neveu, 2004, p. 332).

Privatization is often seen as a strategy for revitalizing national media industries,

primarily because such efforts are done to maximize the proceeds from sales to help minimize a state’s

fiscal balance problems, as well as to improve the overall performance of the sector. However, as

Audenhove, Burgelman, Nulens, and Cammaerts (1999) observe of the South African context, “the

question remains of whether and under what conditions privatization does contribute to the development

of the sector” (p. 395). This is in light of the fact that, in many instances, sale packages are skewed

toward increasing the sale prices of private firms rather than increasing efficiency of the sector. In

addition, because the terms of exchange are not equal on the global scene, countries that embrace

International Journal of Communication 3 (2009) Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica 311

liberalization and privatization may find themselves at a disadvantage and risk losing substantial power

over the development of their media industries.

Apart from the economic and social drawbacks that accompany privatization, there is also the

cultural dimension. As the cultural imperialism argument holds, privatization can affect sovereignty where,

intentionally or not, imported programming weakens cultural bonds and accelerates the incidence of

cultural attrition (Price, 2002, p. 98). This is because privatization affects content by reorienting its

distribution from the public to the private sphere, which in most cases results in increased non-indigenous

programming, rendering local systems as mere distribution systems for imported Western programming.

The role that national media play in building national identities and stabilizing nation states is well

documented (White, 1976; Cuthbert, 1977; George, 1981; Hafez, 1999; Price, 2002; Goonasekera, 2003;

Hamelink, 2003; Curran, 2005). Where state-owned media is replaced by private media, the cultural

rights of indigenous citizens are placed in the context of calculation, one where commercial imperatives do

not cater to the linguistic and other cultural needs of ethnic minorities or indigenous groups, but instead to

the financial bottom line.

Media Globalization and Cultural Imperialism

The rise of media globalization has precipitated the porosity of cultural boundaries, giving rise to

concerns over cultural sovereignty and cultural rights. While such concerns have been dismissed by

proponents of globalization as unfounded, for developing countries such as Jamaica, whose economic

reality precludes the development of strong local productions and so fosters reliance on imported

programming, these concerns are quite relevant. Research has shown that, where local productions are

weak, inroads made by foreign media can be dangerous (Lee, 2003, p. 51). Media privatization

exacerbates this reliance, given that it encourages the inflow of imported content on the principle that,

within a free market system, there should be no barriers erected against the free flow of cultural products

across borders. Most importantly, as private media rely heavily on advertising dollars for economic

viability, there is a constant stream of cultural goods originating in North America and Europe that

inundate the local scene by way of paid television commercials.

However, proponents of the cultural imperialism strain of globalization have been widely criticized

by theorists who view their perspective as decidedly romantic and curiously oblivious to available empirical

evidence that suggests otherwise. According to Tomlinson (1997, in Banarjee, 2003, p. 66), the cultural

imperialism perspective makes “unwarranted leaps of inference from the simple presence of cultural goods

to the attribution of deeper cultural or ideological effects.” These critics suggest that instead of creating

homogenization, globalization succeeds in producing a heterogenization of cultures. As such, the

perception that the West has cultural dominance over world cultures is overstated. Aided by a postmodern

theoretical sensibility, the global cultural perspective contends that globalization, instead of overpowering

indigenous cultures and engendering a mono-culture, leads to cultural hybridity or heterogenization. In

this respect, proponents of the cultural hybridity perspective argue against the cultural imperialism

concept for its perceived assumption that the media audiences of receiving countries are cultural

simpletons incapable of resisting or even negotiating such messages.

312 Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon International Journal of Communication 3(2009)

Although not a hardcore proponent of the global cultural perspective, Lee (2003, p. 51), makes

an important observation that audiences usually prefer local to foreign media products, and usually have a

taste for things local (Atal, 2003; Banarjee; 2003; Sinclair, 2004). This concept is better known as the

cultural proximity theory, popularized through the work of scholars such as Joseph Straubhaar.

Cultural Proximity

The main assumptions of cultural proximity theorists are that local programming is more

culturally proximate or relevant than imported programming originating from culturally disparate places

and therefore preferred by local viewers. As a result, the point has been made that while Western media

has penetrated the boundaries of other national cultures, they have only managed to do so in a

conditional or negotiated sense. That is to say, because media companies compete and operate in a global

as well as domestic marketplace for audience share and advertising revenue (Albarran (2005, p. 299), in

order to gain local access, many transnational corporations (TNCs), such as Sony Entertainment Television

and Star TV, have had to localize their products and advertising. This is based on the argument that local

audiences still prefer local programming to imported content and will support local productions as long as

they are of good production quality.

In India, for example, despite the fears of cultural invasion that accompanied the advent of Star

TV and CNN in the early 1990s, it was Indian satellite to cable channels that captured the allegiance of the

local audience based on their offerings of local programme content produced in Hindi (Sinclair, 2004, p.

78). Again using India as an example, Lee (2003, p. 50) points to the preference for local output when he

says, “No channel of STAR TV can match the popularity of Zee TV in India, which employs Hindi

programming and a hybrid approach.” The same has been said of Asian countries such as China and

Taiwan, and of Latin American countries such as Brazil and Mexico (Curtin, 2005, pp. 163-165; Lee, 2003,

p. 51; Wang, 2003, pp. 36-41, Banarjee, 2003, pp. 66-67; Chadha & Kavoori, 2000, pp. 425-428), where

local channels such as Phoenix in China and Taiwan, TV Globo in Brazil, and Televisa in Mexico dominate

the local market.

However, the discourse surrounding the idea of cultural proximity is more often than not

articulated in reference to Latin American countries such as Brazil and Mexico and Asian states such as

Japan, Taiwan, and India. In these areas, regional markets for television programming have emerged

based on geo-linguistic factors, which aided in the growth of regional media products. Populations defined

by similar language, shared history, and other cultural characteristics tend to seek out cultural products,

such as television programs or music, which are most similar or proximate to them (Straubhaar &

Viscasillas, 1991; Straubhaar, Fuentes & Giraud, 2002). As such, places like Brazil, Mexico, the Dominican

Republic, Japan, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and India have witnessed an increase in local output as the

demand for U.S. media products is less than that for local media (Straubhaar & Viscasillas, 1991). For

example, over a period of 38 years, from 1962 to 2000, national production in Mexico has grown

exponentially, from 59% in 1962 to 71% in 2000 (Straubhaar, Fuentes & Giraud, 2002).

International Journal of Communication 3 (2009) Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica 313

In places such as Jamaica, cultural proximity does not seem to operate in the same way that it

does in the above mentioned places. As will be discussed later on in the paper, there are no significant

increases in national or regional production based on shared geo-linguistics. This is because the geo-

linguistic similarities between Jamaica and places such as the U.S., as well as the former’s poor economy,

enable excessive programming importation instead facilitating regional exchange. In Latin America and

Asia, language acts as a sort of shield from American cultural imports, which makes the resistance to such

products through the circulation of culturally proximate ones more feasible and successful. However,

whereas local programming appears to be the preferred televisual choice where the geo-linguistic context

allows, it is important to note that in the media marketplace, that which scholars identify as cultural

proximity, television executives see as a great business opportunity. That is to say, with the recognition

that local audiences tend to prefer culturally proximate programmes, executives have come to understand

the value of localization through programme modeling.

Programme Modeling

Programme modeling refers to the replication of the design, form, and content of a programme

originating from elsewhere without any adjustments to fit the cultural, social, and economic context within

which such a programme will be commercially disseminated by a station or network and viewed by a local

audience. The term emerged from discussions based on the topic of this paper between the author and

her mentor, Patricia McCormick. It closely resembles what Liu and Chen (2003) refer to as closed format

adaption, but it varies in that the latter infers or presupposes some degree of alteration or conversion of

the programme material to fit a local cultural context, while the former does not. Format adaptation is

therefore less culturally intrusive than programme modeling. According to Liu and Chen (2003), format

adaptation occurs where significant elements of a programme are copied or taken and adapted for local

consumption. There are levels of adaptations which range from open, where selective generic elements

are utilized, to closed, wherein a higher level of replication occurs (Liu and Chen, 2003). Muller (2008)

even goes as far as to say that “while formats may carry certain recognizable elements, the content is

always nationalized, adapted for different national markets and cultures.” Programme modeling often

becomes manifest where an imported programme is “localized” for national TV with a lack of

distinguishing indigenous characteristics.

The dissemination of television formats from dominant industrialized nations has become very

popular over the past ten years, with the United Kingdom accounting for 33 percent of the global market,

making it the main originator of global formats (Worldscreen.com). These include shows such as Dancing

With the Stars, Got Talent, The X Factor, Wife Swap and Pop Idol, the successes of which helped boost the

global sale of UK programme exports by 20% in 2007, earning the industry an estimated US$1.17 billion

(Pact, 2008). Other global players include the U.S. and the Netherlands, which together account for 21%

of the share of global formats in total (Worldscreen.com). As reported by Freemantle Media, the most

successful global entertainment format of 2007 was the U.S. game show Are You Smarter than a 5

th

Grader, which entered 22 new countries within just eight months of its release. The latter is a testimony

to the growing popularity of global format exports, which are available in an average of 200 countries

worldwide.

314 Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon International Journal of Communication 3(2009)

While some critics argue that the popularity of television formats are reflective of the

interconnectivity among television systems and industries worldwide (Waisbord, 2004), and that they are

a vehicle for localization (Keane, 2002), there are very important socio-political implications that

international format adoptation has for lesser developed societies such as Jamaica. First of all, the

exportation of television formats is a business wherein a few media companies are able to sell the same

idea worldwide, where audiences tune in to a national variation of the same programme. Not only does

this represent a standardization of content, but also a subversive glocalization wherein cultural

imperialism is perpetuated in a more subtle form. TV formats thereby become a ‘Trojan Horse,’ to borrow

a term from Keane (2002), in which foreign content migrates across national boundaries in a seemingly

benign and nonthreatening way.

Imported formats are formulaic in nature, relying on the “‘pie and the crust’ model — whereby

the format is the crust and the various localizations are the pie” (Keane, p. 7, 2002). In this regard,

programme modeling is a more appropriate description of what exists when imported formats are adapted

to local television. In the case of Jamaica, local programming resembles a miniature version of American

television, given that is from where most of the programme formats are imported. While format

adaptation is a global phenomenon, the implications of this trend for a country such as Jamaica are not

the same as for more industrialized societies. As the social and economic capital of industrialized countries

is similar, importation of models does not have the same socioeconomic consequences as it does for

Jamaica — consequences such as stunting the growth of local industries while enabling the expansion of

material consumption and the development of wants that are incompatible with the social and economic

realities of a developing country. As Fung (2003) argues, “adapting global television formats might result

in cultural globalization while being at odds with local cultural values . . . in most instances, cultural

dissonance is inevitable and unavoidable” (p. 86). Local Jamaican television has not modified the U.S.

television programmes to fit the “local structures of feeling” (Lee, 2003, p. 52) and the transnational

adaptation of such programmes have not been deeply conditioned by the local cultural coding. The

remainder of the paper addresses the cultural implications of programme modeling on Jamaican television

and seeks to discover how present television content aired on Jamaica’s three national commercial

television stations compares to content aired prior to increased private ownership of television media in

the country. Such a comparison will help to determine whether or not privatization has ushered in more

localization as promised and if there is a continued dominance of U.S. cultural imports on Jamaican TV.

Methodological Framework

The study employed a programme analysis of content aired on Jamaica’s three national

commercial television stations, as well as informant interviews to investigate the nature of the flow of

imported television content to Jamaica. A programme analysis was done to disclose the significance of

particular types of programming or content based on the space or amount of airtime they are allotted.

Such an analysis helps to determine the nature of information flow between Jamaica and the industrialized

countries of the West by facilitating a quantitative comparison of the hours devoted to national

programming and imported programming. It also helps to determine what types of content dominates the

airwaves in terms of quantity of airtime, as well as to facilitate comparisons between the stations to

International Journal of Communication 3 (2009) Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica 315

determine which stations, if any, exhibit a particular predilection for certain types of content, whether

imported or local, entertainment or informative, etc.

The programme schedule for all three national commercial television stations, namely, TVJ,

CVMTV and LOVETV, were analyzed over the period of a week starting on January 27 and ending February

3, 2007. While some stations remained on air for 24 hours, others went off the air after midnight.

Programmes were analyzed according to 1) length, meaning the total airtime allotted; 2) type, meaning

essential characteristics; and 3) origin, meaning point of production or creation. For the purposes of

coding, several mutually exclusive categories were identified a priori.

This week was randomly chosen and does not take into account seasonal influences on

programming which may affect the volume of content derived from the various points of origin identified

in the study. For example, during the Easter season, Jamaican television has an increased proportion of

religious programming, much of which may be classified as national in its origin. As a result, the amount

and categories of imported content would be affected at times such as those days when “special” Easter

programming is not available, and the proportion of non-religious and imported content would be

increased.

Additionally, programming on Jamaican television is also influenced by seasonal sporting events

such as cricket. For example, in 1999, a study conducted by McCormick (1999) revealed that Jamaican

television programming was significantly influenced by a live five-day cricket match between the West

Indies and Australia during the week of Sunday, March 28 and Saturday, April 3. According to the study,

the days on which cricket was not aired, the hours of imported content on TVJ and CVMTV increased by

approximately 2,022 minutes (McCormick, 1999). Thus, although the period that was examined was

“normal” and free of special events programming, the results would refer to the overall nature of

programming on Jamaican television.

The study also utilized the informant type interview as one of its primary data gathering sources.

These were individual interviews that sought to garner the perspectives of key actors in the media

industry, government, and civil society at large who have expert knowledge of, and insights into, the

media industry and its practices. These individuals have special mobility within media organizations,

meaning they have uninhibited access to certain domains of information, such as policing, making, and

implementation. Interviewees were derived from the media industry, including personnel from the three

previously mentioned national stations, the JIS, CPTC, and STV operators. They were also drawn from

academia, including professors from the leading university’s school of Communications; the government,

including officers from the Ministry of Information and Development; and the professional sector, including

Public Relations executives and practitioners. The discursive elements of the interviews were significant to

the study in that they allowed for a comparative analysis with the data gathered from the programme

analysis of content aired on the three national commercial television stations, as well as with the

theoretical framework guiding the research.

316 Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon International Journal of Communication 3(2009)

Findings

For the week under review, the hours of programming for all three stations combined totalled

24,900. Of this number, 8,515 hours or 34% of this was devoted to programmes of national origin. A

cursory examination of the data would indicate that the most significant category related to national

programming would be religious. It represents approximately 1,860 or 22% of the total hours attributed

to national content. However, closer examination of the data reveals that these hours are

disproportionately distributed among the three national commercial stations, given that LOVETV, a

religious station, accounts for 100% of such programming. Its percentage representation of total hours

allotted to national content is therefore skewed and is more an indicator of the ideological framework of a

particular station than it is of overall national content. When religious programming is excluded from the

total hours devoted to national programming, local content is reduced to just 27% of total television

airtime. As a result, the most important programme category of national origin becomes the news, which

accounts for approximately 19% of the total national hours.

Programmes originating in the United States comprised 15,170 hours, or 61% of total airtime for

all three national commercial stations, while those categorized as deriving from other international sources

accounted for approximately 975 hours, or 4% . Together, the programming of U.S. and International

origins make up 65% of the total airtime. The majority of imported programming coming from the United

States falls under the category of religious. This category makes up 4,835 hours, or 32% of imported

programming. However, as was the case with local content, this representation is more reflective of the

religious bias intrinsic to LOVETV’s programming than it is of imported content across the board. Outside

of this category, the movies or feature films grouping become most significant, representing 3,630 hours

or 35% of imported content. Children’s programming follows closely, comprising 1,770 hours, or 17% of

imported programming, outside of the religious category.

When compared to previous data, the overall airtime allotted to imported content remains fairly

consistent. For example, in 1994, imported programming comprised 66% of total airtime (McCormick,

1994), which is only 1% more than that recorded for 2007. In 1999, imported content accounted for 79%

of total airtime, but this spike from previous years is only indicative of LOVETV’s entry into the television

landscape the year before, as well as prolonged broadcasting hours, as indicated before. This also explains

the apparent jump in the percentage of international programming noted in the same period, i.e., from

2.2% in 1994 to 17% in 1999. Therefore, what seems to be an increase in these categories of

programming is probably indicative of the addition of more airtime that was not previously present. With

regard to regional programming, this category shows a steady decline from 1994 to the present (see

Table 3). In 1994, regional content made up 0.9% of total television airtime. In 1999, it comprised .01%,

showing a decline of approximately 90%. At present, regional content is nonexistent on Jamaican

television.

In summation, the data derived from the programme analysis seem to indicate that increased

private ownership of television media in Jamaica since 1994 has done little to change the ratio of imported

programming to local. While there is an observed 10% increase in local content between 1994 and 2007,

it may not be a real indicator of growth, given that LOVETV was absent from the television scene in 1994

International Journal of Communication 3 (2009) Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica 317

and only came into being in 1998. Thus, the hours of added airtime that LOVETV contributes to the overall

broadcasting time is perhaps what this 10% difference represents. The proportion of imported content is

still significantly higher than local content, and it has more or less remained the same since 1994. What

are the implications of this trend?

Homogenization of Content

What the interview data and the programme analysis data imply is that there is little variety in

the content that is aired on the three national commercial television stations. For example, the types of

programmes aired on both TVJ and CVMTV are remarkably similar in nature and essentially take up the

same percentage of airtime. Both stations appear to carry the same type of content, and in roughly the

same proportion. For example, both TVJ and CVM have feature films or movies as their primary category

of programming, which takes up roughly the same percentage of airtime on both stations, i.e., 18.8% and

18.3%, respectively.

This apparent lack of variety in programming is a classic example of the kind of media landscape

that a market-driven model of media eventually creates. What the market reveals as financially

sustainable is what everyone else is producing (Copps, 2005), and as a result, the same types of

programming dominate the airwaves. Media operators are loathe to produce material outside of the

handful of genres or types of programming that have already proven to be successful. As McChesney

(2004, p. 193) argues, “Entertainment programming has mostly gravitated toward a handful of

commercially successful genres with formulaic characters and plots.” Innovative material is not necessarily

attractive, as there is no track record of success that will guarantee large and sustained viewership and

subsequent advertising dollars. Television networks thus operate on the basis of minimizing risk by relying

on the “tried and true.” This approach essentially stifles variety and promotes sameness of content,

otherwise known as content homogenization, wherein repetitiveness takes precedence over inventiveness.

Globalization has ushered in what McChesney (2005) refers to as the conglomerate era, wherein,

working through economies of scale, corporate media seek to bring about uniformity in their operations in

order to establish an economic model that promotes synergy among various media products and entities.

The homogenization that this way of doing business brings about means the packaging and promotion of

programming through a one-size-fits-all strategy. Through expanding media globalization, content

homogenization emerges in countries such as Jamaica with the indirect flow of ideas about program

production and programming strategy through satellite from places such as the United States. More

countries seem to be producing similar soap operas, talk shows, and reality shows, among other television

genres (Straubharr, Fuentes, Giraud & Campbell, 2002). This tendency seems to be naturally affiliated

with globalization as it relates to media industries, as Straubharr, Fuentes, Giraud & Campbell (2002)

argue:

At the global level, we can observe the ongoing spread of underlying paradigms of

cultural production, like the shift toward commercial cultural industries, such as

commercial network television. Those changes do shift the boundaries of what is seen as

318 Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon International Journal of Communication 3(2009)

possible in television programming and production. We can observe an ongoing global

convergence or homogenization of general ideas about how to program broadcast

television networks, such as the prevalence of entertainment genres like soap opera,

reality shows, comedy, sports, talk, and drama, especially in prime time. (pp. 1-2)

It is quite apparent that this general prevalence toward the standardization of content is present

in Jamaican television programming. There exists what one participant refers to as a “bandwagon"

mentality approach to content, meaning that most of the local programmes being produced and aired

pivot around the same themes and are of the same genres. The types of local programmes produced by

CVM and TVJ are strikingly similar, and the basis of their competition seems to rest more on their ability to

“out imitate” each other, instead of any desire to be different. As the data from the programme analysis

indicate, the vast majority of the content aired by the stations, especially CVM and TVJ, can be classified

as entertainment, primarily as it relates to locally produced material. This is a clear reflection of what

Chester and Larson (2005) observe as the market’s strong economic bias toward the cheap and the

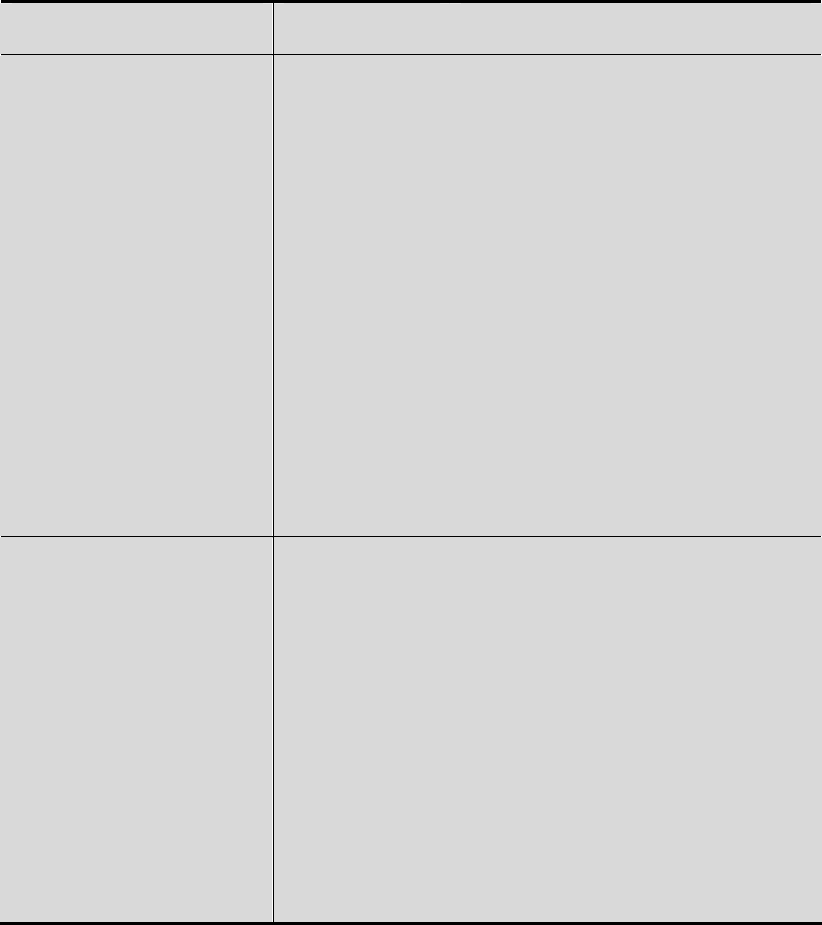

imitative when it comes to television production. Figure one demonstrates just how alike CVMTV and TVJ’s

local productions are.

As the figure illustrates, what is available locally on CVMTV is merely a slight variation of what is

available on TVJ. Each station seems to adopt a formulaic approach to producing content, which often

entails a cocktail of hype, sex, and triviality, what is referred to as “lowest common denominator”

programming. Having adopted the market model approach to media operations, national commercial

stations try to minimize their risks by producing programming which will capture the attention of viewers

across the population instead of creating original and innovative material, and as mentioned before, most

of this material is strictly entertainment. What is also articulated by the stations’ programming schedule,

as well as by the programming managers, is that there is a strong need to compete with U.S.

programming formats, as well as content. The types of programmes produced reflect the strong influence

of U.S. media industries on the global scene. This dominance of the U.S. in the televisual market

continues to foster dependence on imported products in places such as Jamaica through the competition it

fosters with local economies. Media in Jamaica operate under certain economic boundaries which limit the

cultural outcomes within them (Straubhaar & Hammond, 1998), meaning that such countries cannot

afford to produce material with the blockbuster values, inclusive of the glitz and fancy graphics to which

participant 5 referred, that characterize U.S. productions. While local programming may not necessarily

need blockbuster values to be successful or popular among Jamaican viewers, Hollywood production

values have become the standard by which local producers measure quality programming. It is partly for

this reason that Jamaica has in the past, and still does today, import much of its content from the U.S.,

which has perhaps cultivated a taste for American genres, if not among viewers, then certainly among

producers of television content. At the global level, the U.S. is the primary media exporter in the world,

largely due to its economic wealth (De Bens & de Smaele, 2001). It dominates certain kinds of

productions, such as feature films, which require huge investments, as well as certain kinds of television

genres such as action-adventure, which also require big budgets (Straubhaar & Hammond, 1998).

International Journal of Communication 3 (2009) Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica 319

Stations Programme

Name

Description

CVMTV The Party

The E-Strip Hit List

Wad-Up

A one hour programme that entails a

dance party staged at a local café. It

showcases the latest trends in

Jamaican popular music, dance, and

party style.

A music programme presented by two

radio disk jockeys who play the latest

music videos and host a special

musical guest each show. The

programme also provides the

audience with a chance to appear on

the show and to win cash prizes by

voting for their favorite videos.

A half hour programme involving vox

pops that ask questions pertaining to

a range of entertainment and topical

issues.

TVJ Weh yu sey

Hype Zone

Groove Music

Vox pops bringing the views of

Jamaicans on topical issues of the day

A music video programme that entails

interviews and profiles of Jamaican

entertainment celebrities and

highlights of popular parties. These

are interspersed with music videos,

and the show is presented by a host.

A music video programme that

profiles the party scene and airs local

and overseas music videos chosen by

viewers.

Figure 1. Similarity of CVMTV and TVJ Local Programming.

320 Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon International Journal of Communication 3(2009)

It is therefore able to dominate the market and thus export its models, genres, and ways of

creating and managing television, thereby becoming the driving force behind the increasing global

economic structure of market capitalism that reinforces the attractiveness of U.S. models.

Perhaps the rationale behind the modeling of U.S. programming and the resulting

homogenization of content on Jamaican television is related to the role that advertising plays as the

primary source of revenue for media operations. Advertising has come to colonize much of media,

“radically transforming its logic and content” (McChesney, 2004, p. 138). As a result, the interests of

consumers are increasingly being filtered through the demands of advertisers who covet particular

demographics. The end product of this commercial sifting is formulaic TV. A standard entertainment

package is being leveraged across the various media corporations with the aim of capturing advertiser-

preferred demographics. Seemingly, the repetitive nature of television content in Jamaica as iterated by

media practitioners seems to be driven by the need to procure advertising revenue on the part of

commercial media organizations. This compulsion drives producers to adopt a “copycat” approach to local

production, so that, while a programme may employ Jamaican talent, it is merely a Jamaicanized version

of American television as mentioned earlier.

As such, the argument could be made that the apparent influence of American programming on

Jamaican television is evidence of the inevitable impact of globalization on world cultures. Globalization

has ushered in growing cultural interdependency among nations (Goonasekera, 2003), and the global

proliferation of media has heightened and hastened the porosity of cultural borders. This phenomenon is

what critics such as Sinclair (2004) and Straubhaar (1997, 1999, 2002) refer to as cultural hybridity or

cultural fusion, one of the benefits of globalization that is propagated through international media.

According to these arguments, cultures are not static, but complex systems that respond to the

introduction of new cultural forms through conduits such as television, through synthesis. Consequently,

the apparent Jamaicanization of American programming could be read by such critics as evidence of this

synthesis or glocalization, a concept that connotes the intersection or fusion of the global and local (Hines,

2000, p. 8). This argument is partly premised on the idea of cultural proximity as previously mentioned.

Cultural Proximity and Local Production

There is a general perception among those interviewed that “Jamaicans love to see themselves

on TV,” meaning that Jamaican audiences literally like seeing themselves on television. At the individual

level, the ordinary citizen is keen on having his or her proverbial 15 minutes of fame on the television

screen. However, more significantly, what this statement connotes is that at the macro level, Jamaican

viewers are very interested in seeing culturally representative or relevant images of themselves portrayed

on local television. This general attitude is reflective of what Straubhaar (1996, 1997) and other scholars

refer to as cultural proximity, the idea that local audiences tend to prefer local cultural products when

available over imported ones. Audiences are therefore inclined to favor media which are illustrative of

their own culture nationally as well as regionally (Burch, 2002), as they “want to see people and styles

they recognize, jokes that are funny without explanation” (Straubhaar, Fuentes & Giraud, 2002, p. 5). To

use another framework, people acquire cultural capital based on their experience, family background, and

education, which enables them to understand things (Bourdieu, 1984). Thus construed, it is therefore not

International Journal of Communication 3 (2009) Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica 321

surprising to discover that Jamaicans have an impulse to see culturally pertinent images of their locality

on display.

This is partially responsible for the popularity of the only available local soap opera, Royal Palm

Estate, produced by Jamaican media owner and independent content producer, Lennie Littlewhite. Royal

Palm Estate first aired on CVMTV in March 1994, shortly after that television station made its debut. It is

one of the longest running and most successful local programmes which still air on television. For this

reason, it is often used as the yardstick by which the potential popularity of local programming is

measured. That is to say, the success of Royal Palm is often used as a sort of litmus test for the success of

future local programmes. It is popular by demand, primarily because it satisfies that desire held by

Jamaicans to see themselves on TV, meaning, the need to see culturally relevant images that are

reflective of what they perceive to be Jamaican cultural identity.

In this respect, the idea of cultural proximity appears to hold true. Jamaican audiences gravitate

toward Royal Palm, unlike other local productions currently being aired on TVJ and CVMTV, because Royal

Palm does not just rely on local actors for its “Jamaican-ness.” As a cultural product, it engages many

aspects of Jamaica’s socio-historical heritage for its authenticity. The script often pivots around traditional

Jamaican mythology and folklore, such as obeah and folk religion, and also draws on elements of the

current political and social milieu, such as rural and urban poverty, crime, and partisan politics, for

inspiration. In this respect, Jamaicans do see themselves reflected on the screen, as life on Royal Palm

Estate often imitates life as they sometimes experience it. Even the very name, “Royal Palm Estate,” is

evocative of Jamaica’s historical past involving sugar and slavery, wherein the plantation estate emerged

as emblematic of this era.

That Royal Palm Estate is popular based on its “localness” resonates with Lee’s (2003, pp. 50-51)

observation that audiences usually prefer local to foreign media products and will support local

programmes as long as they are of good production quality. Such programmes capture the allegiance of

local audiences and are a defense against the onslaught of imported media content, especially in a context

such as Jamaica, where a diseconomy of scale makes it easier and cheaper to import media programming.

Scholars such as Burch (2002), Ferguson (1992), and Straubhaar (1996; 1997) surmise that cultural

proximity may act as a defense against the onslaught of imported programming, especially in regions such

as Latin America and the Caribbean, by driving an increase in national production based on demand.

However, what appears on the surface as localization in many Jamaican programmes is, in fact,

thinly veiled American popular culture. The localization of global media products constitutes Euro-

American programme modeling, which becomes a front for the homogenization of content. Although it

would appear that there is a market for indigenous content, and that that demand is being filled, what is

being produced on Jamaican television cannot accurately be defined as local. This is because glocalization

in its true sense connotes a space in which the local and the global exist as some form of hybrid, wherein,

as Ingleby (2006, p. 3) argues, people continue to draw identity from their locality and its traditions but

are also keen to take advantage of global cultural offerings. This is not what exists on Jamaican television.

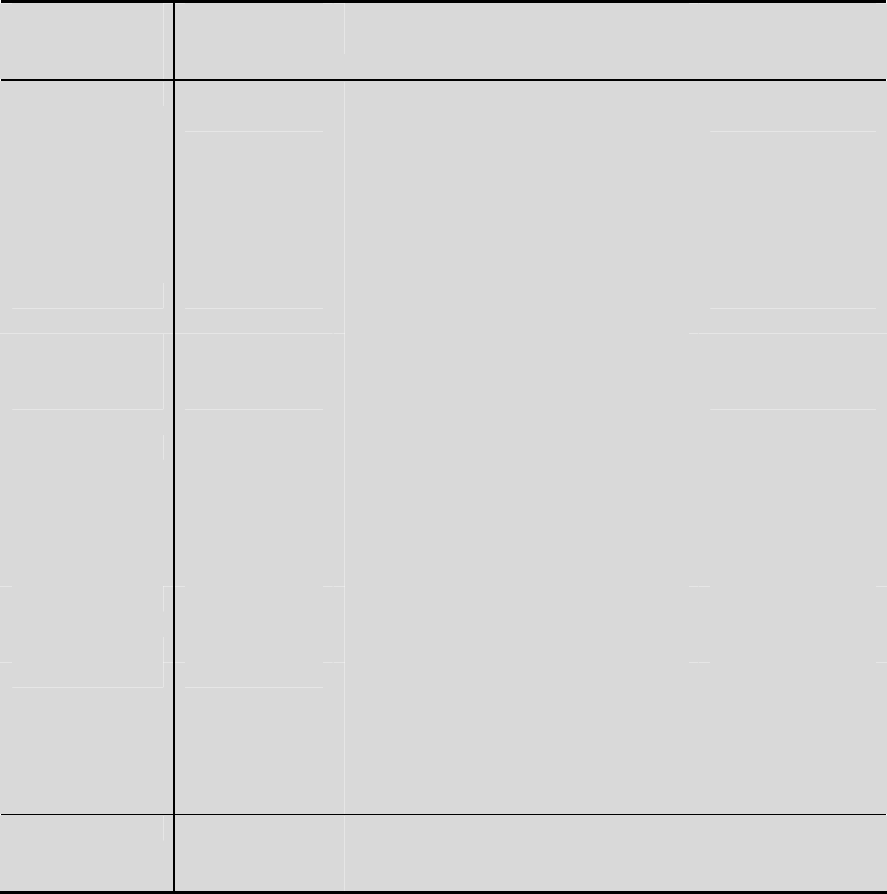

In practice, there is an override of the local by the global. Local programmes, such as TVJ’s Rising Stars, a

spin-off of FOX network’s American Idol, and CVMTV’s Model Search, a spin-off of the CW’s America’s Next

322 Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon International Journal of Communication 3(2009)

Top Model, are only local insofar as they rely on Jamaican talent. There is an over-reliance on American

programme modeling, as is evidenced by the programme formatting and styles of production (see Figure

2). A simple reliance on local talent is not enough to say that producers are drawing on the identity of the

Jamaican locality. There is no true localizing element which would legitimize the production as a truly

‘glocal’ product.

Programme

Name

Programme

Type/Genre

Description and Format

American Version

Rising Stars Performance

reality

A talent show that showcases untapped

Jamaican musical (singing) talent.

Contestants sing live in front of an

audience and three judges drawn from

the entertainment industry. At the end of

each show, viewers call in their votes and

the persons with the highest number of

votes proceed to the next round.

Fox TV’s

American Idol

Watch and Win Game show A challenge/question and answer show

where kids compete for prizes

On a Personal

Note

Reality Goes behind the scenes of the lives of

Jamaican personalities

VH1’s All Access

Weh yu seh Infotainment Vox pops bringing the views of Jamaicans

nationwide

Island Dreams Reality A home decorating and real estate show

that highlights the architecture and

decorating details of upper-class

Caribbean residents. It also gives

decorating and building tips as well as real

estate advice.

The Home and

Garden Channel’s

(HGTV)Homes

Across America

A Day in the Life Reality A behind-the-scenes look at the lives of

Jamaican celebrities

VH1’s The

Fabulous Life

Family Fortune Game Show Two families square off for cash prizes Family Feud

Hype Zone Entertainment A music video programme that entails

interviews and profiles Jamaican

entertainment celebrities and highlights of

popular parties. These are interspersed

with music videos, and the show is

presented by a host.

BET’s 106 and

Park

Groove Music Entertainment A music video programme that profiles

the party scene and airs local and

overseas music videos chosen by viewers.

BET’s 106 and

Park

Figure 2. Description of Local Programming on TVJ.

International Journal of Communication 3 (2009) Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica 323

Drawing upon issues that are identifiably Jamaican, such as reggae or popular Jamaican folklore,

would help to make the tone of such programmes more local. Jamaican television is thus not adapting to

global media trends as cultural hybridity theorists would suggest, but rather, assimilating. The difference

between the two is significant, as adaptation implies some sort of mutuality or harmony, such as that

which exists between parts of a mechanism, while assimilation entails absorption to the point where things

become identical. While the former suggests a symbiotic relationship, the latter denotes erasure.

Therefore, the observation that privatization of TV media will eventually lead to an increase in local

content is problematic, as the legitimizing element of the local is overwritten. As successful as Royal Palm

is, it is more an exception than the norm in terms of local production. Local production is not necessarily

increasing as the ratio of local to imported programming has remained fairly consistent over the past 30

years. In 1972, imported content comprised 71% of national airtime (Straubhaar, 1996); in 1988, it made

up 76% of total television airtime (Dunn, 1988); and in 1999, it constituted 79% of overall television

airtime (McCormick, 1999). Imported programming, predominantly from the U.S., continues to dominate

television airtime in Jamaica.

This by-product of cultural proximity has not been manifest in Jamaica for obvious reasons, the

primary one being Jamaica’s economy. Jamaica’s media industries do not have an adequate economic

base to create the type of programming that can compete with the slick productions emanating from the

U.S. Thus, although there may be a national demand for national productions, Jamaica’s economic

constraints bind and frame its cultural possibilities. Notwithstanding, when it comes to the operation of

cultural proximity at the Caribbean regional level, the economic argument does not adequately explain the

lack of such programming in Jamaica. Although Jamaica shares many cultural similarities, such as

language, history, and political system, with other Caribbean countries like Trinidad and Tobago and

Barbados, there is 0% regional programming on Jamaican television, despite the fact that places such as

Trinidad and Tobago have fairly well-established local production industries. While a regional news agency,

Caribbean News Agency (CANA) exists, its focus is news, not television programming. Another regional

entity, the Caribbean Broadcasting Union (CBU) produces a regional television magazine programme,

Caribscope, which airs features submitted by various Caribbean countries. However, this organization is

primarily a collection and dissemination centre for programmes produced by member states, and it does

not develop content. While it was a feature of Jamaican television in the 1990s, Caribscope no longer airs

on local television. The presence of regional content is therefore not very strong, and it is absent from

Jamaican television altogether.

As the U.S. is the largest regional exporter of television programmes, national television stations

are inclined to import content from that country. As Straubhaar, Campbell, Youn, Champagnie, Elasmar &

Castellon (1992) point out, in terms of actual programs and channels directly watched by audiences, the

"global" flow of television outward from the U.S. is probably strongest among the Anglophone nations of

the world, such as the English-speaking Caribbean. These are the countries or regions where U.S.

television exports tend to be most popular and best understood, based on language and geographic

proximity. In addition, U.S. television media exports tend to be more accessible in Jamaica because it falls

under the direct reach or footprint of U.S. television satellites (Straubhaar, Campbell, Youn, Champagnie,

Elasmar & Castellon, 1992).

324 Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon International Journal of Communication 3(2009)

Conclusion

There are strong implications for cultural imperialism embedded in the use of imported models

for producing local television content. While “commercial assumptions and modes of presenting society to

potential consumers may very well survive such adaptations” (Straubhaar et al., 1997, p. 2), meaning

that such models may become so localized to the point that their original formatting is unrecognizable,

this does not seem to be the case with Jamaica. It is well recognized that in places such as Mexico and

India, for example, the adaptation of American programme models have been so successfully localized

that a whole, separate product has emerged, as in the telenovela in Mexico and the Bollywood film

industry in India. However, there is no such successful amalgamation of genres in Jamaica. Local

programmes do not bridge the gap between local and global to the point where an original genre is

actually created.

The market model of media management that characterizes media operations in Jamaica has a

bias for imported content which is extended by, and reflected in, the tendency to model current local

content from U.S. programming. This business model further compromises the growth of quality local

productions, as the convenience of modeling discourages the creativity and innovation required to produce

local content on a budget. Given the market imperatives of privatized media, it becomes much easier to

adapt successful Western programme formats in Jamaica than to create productions of local originals.

As previously discussed, the trend in adapting or modeling successful Western genres is not a

phenomenon specific to Jamaica. Under the new market conditions of the multi-channel cluster brought

about by new technologies and increased privatization of service, the adaptation of successful and popular

TV formats from one country to another is occurring on an increasingly regular basis (Malbon & Moran,

2006). However, although this is a global phenomenon, the implications of this trend for a country such as

Jamaica are not the same as for more industrialized societies. As the social and economic capital of

industrialized countries is similar, importation of models does not preclude the growth of local industries in

the same way that it does for Jamaica. In Jamaica, the modeling of programme formats exacerbates the

local industry’s dependence on Euro-American cultural goods, as most of these genres originate in the

U.S. and England. Programme modeling in Jamaica gives a false sense of local production, as it is, in fact,

unoriginal. A developing caveat concerning this matter rests with the fact that issues of copyright

protection are now arising concerning the adaptation of formats. In the future, the media industries of the

U.S. and UK are set to collect massive returns on format exports, having already cornered the global

market, as those importing these genres may eventually have to pay copyright fees

(http://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/300159, retrieved 2/24/2007). In this event, programme

modeling in Jamaica may only be serving as a temporary crutch bearing up local production output. This

poses a double jeopardy for local programming. As modeling does not contribute to the creation of original

local content, local programming is already weak. If national commercial stations have to pay for adapting

Western programming formats, what now passes for local content may eventually dissipate.

That imported programming still dominates airtime and whatever local productions that do exist

model U.S. programming formats and genres, means that most of the cultural images to which Jamaican

viewers are exposed through television are not their own. The implications of this are that the cultural

International Journal of Communication 3 (2009) Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica 325

imperialism thesis is still relevant in this age of increased private ownership of media in Jamaica. The

resulting homogenization of content that this type of media operation encourages may be viewed as an

extension of U.S. domination of the television content market. As De Bens and Smaele (2001) conclude at

the end of a similar study done on television content flow in Europe, national governments face an

important task in dealing with the continued imbalance of television content on national airwaves. Not only

does television media policy in Jamaica need to adopt a more cultural approach, but the audiovisual sector

and broadcasting stations are too important to be left only to market forces for their general growth and

evolution. American soap operas and entertainment offer little substance to address the needs of the local

poor, uneducated, dispossessed, and unemployed.

References

Albarran, A. B. (2004). Media Economics. In Downing, A., McQuail, D., Schlesinger, P.,Wartella, E. (Eds.)

The sage handbook of Media Studies, 291-308. ThousandOaks: Sage Publications.

Atal, Y. Globalization of the media and the issue of cultural rights with special reference to India. In

Goonasekera, A, Hamelink, C. & Iyer, V. (Eds.) Cultural rights in a global world, 225-241. New

York: Eastern Universities Press.

Audenhove, L. V., Burgelman, J., Nulens, G. & Cammaerts, B. (1999). Information society policy in the

developing world: A critical assessment. Third World Quarterly, 20, 2, 387-404.

Bagdikian, B. H. (1996). Brave new worlds minus 400. In Gerbner, G., Mowlana, H. & Schiller, H. I. (Eds.)

Invisible crises: What conglomerate control of media means for America and the world, 7-14.

Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Banarjee, I. (2003). Cultural autonomy and globalization. In Goonasekera, A, Hamelink,C. & Iyer, V.

(Eds.) Cultural rights in a global world, 57-79. New York: Eastern Universities Press.

Barnett, C. (1999). The limits of media democratization in South Africa: Politics, privatization and

regulation. Media, Culture and Society, 21, 5, 649-671.

Boyd, D. (1984). The Janus effect? Imported television entertainment programming in developing

countries, Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 1, 379-391.

Brown, A. (1976). The mass media of communications and socialist change in the Caribbean: A case study

of Jamaica. Caribbean Quarterly, 22, 4, 43- 49.

Brown, A. (1981). The dialectics of mass communication in national transformation.Caribbean Quarterly,

27, 2&3, 40-46.

326 Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon International Journal of Communication 3(2009)

Brown, A., & Sanatan, R. (1987) Talking to whom? A report on the state of the media in the Caribbean.

Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press.

Brown, A. (n.d). A contextual macro-analysis of media in the Caribbean in the 1990’s. Retrieved February

12, 2005, from http://www.wacc.org.uk/wacc/content/pdf/1274

Brown, A. (2001). Caribbean Cultures, global mass communication, technology, and opportunity in the

twenty-first century. In Regis, H. A. (Ed.) Culture and mass communication in the Caribbean:

Domination, dialogue, dispersion, 169-183. Florida: University Press of Florida.

Burch, E. (2002). Media literacy, cultural proximity and TV aesthetics: Why Indian soap operas work in

Nepal and the Hindu Diaspora. Media, culture and society, 24, 571- 579.

Chadha, K., & Kavoori, A. (2000). Media imperialism revisited: Some findings from the Asian case. Media,

Culture and Society, 22, 415-432.

Chester, J., & Larson, G. (2005). Sharing the wealth: An online commons for the nonprofit sector. In R.

McChesney & R. Newman, (Eds.), The future of media: Resistance and reform in the 21

st

century

(pp. 9-20). New York: Seven Stories Press.

Cooper, M. (2005). Reclaiming the first amendment: Legal, factual, and analytical support for limits on

media ownership. In R. McChesney & R. Newman, (Eds.), The future of media: Resistance and

reform in the 21

st

century (pp. 9-20). New York: Seven Stories Press.

Copens, T., & Saeys, F. (2006). Enforcing performance: New approaches to govern public service

broadcasting. Media, Culture and Society, 28, 2, 261-284.

Copps, M. (2005). Where is the public interest in media consolidation? In R. McChesney & R. Newman,

(Eds.), The future of media: Resistance and reform in the 21

st

century (pp. 117-126). New York:

Seven Stories Press.

Cuthbert, M. (1976). Some Observations on the role of mass media in the recent socio-political

development of Jamaica. Caribbean. Caribbean Quarterly, 22, 4, 50-58.

Cuthbert, M. (1977). Mass media in national development: Governmental perspectives in

Jamaica. Caribbean Quarterly, 23, 2&3, 90-104.

Curtin, M. (2005). Murdoch’s dilemma, or “What’s the price of TV in China?” Media, Culture and

Society, 27, 2, 155-175.

Dagron, A. G. (2004). The long and winding road to alternative media. In Downing, A.,McQuail, D.,

Schlesinger, P., Wartella, E. (Eds.) The sage handbook of Media Studies, 41-64. Thousand Oaks:

Sage.

International Journal of Communication 3 (2009) Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica 327

Davis, L. (1999). Satellite based change in Mexican television programming and advertising. Journal of

Popular Culture, 33, 3, 49-61.

De Bens, E., & Smaele, H. (2001). The inflow of American television fiction on European broadcasting

channels revisited. European Journal of Communication, 16,1, 51-76.

Demery, L., & Addison, T. (1987). The alleviation of poverty under structural adjustment. Washington DC:

World Bank.

Dunn, H. (1988). Broadcasting flow in the Caribbean. Intermedia, 16, 39-41.

Dunn, H. (2000, November 14). Toward redesigning media policy” Part 2. The Gleaner. Retrieved October

10, 2006, from http://www.jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20001114/lead/lead5.html

Dunn, H. (2001). Facing the digital millennium: Culture, communication and globalization in Jamaica and

South Africa. In K. Tomaselli & H. Dunn (Eds.), Media, Democracy and renewal in Southern Africa

(pp. 55-81)/ Colorado: International Academic Publishers.

Ferguson, M. (1992). The mythology about globalization. European Journal of Communication, 7, 69-93.

Goonasekera, A. (2003). Introduction. In Goonasekera, A, Hamelink, C. & Iyer, V. (Eds.) Cultural rights in

a global world, 1-6. New York: Eastern Universities Press.

Groswiller, P. (2004). Continuing media controversy. In de Beer, A. S. & Merrill, J. C., (Eds.), Global

journalism: Topical issues and media systems (pp. 128-139). Boston: Pearson Education, Inc.

Hafez, K. (1999). International news coverage and the problems of media globalization:In search of a

‘new global-local nexus.’ Innovation, 12, 1, 47-62.

Hamlelink, C. (2003). Cultural rights in the global village. In Goonasekera, A, Hamelink,C. & Iyer, V.

(Eds.) Cultural rights in a global world, 7-27. New York: Eastern Universities Press.

Hart, P. (2005) Media bias: How to spot it and how to fight it. In R. McChesney & R. Newman, (Eds.), The

future of media: Resistance and reform in the 21

st

century (pp. 51-63). New York: Seven Stories

Press.

Ibelema, M. (2001). Perspectives on mass communication and cultural domination. In Regis, H. A. (Ed.)

Culture and mass communication in the Caribbean: Domination, dialogue, dispersion15-36.

Florida: University Press of Florida.

Ingleby, J. (2006). Globalisation, glocalization and mission. Transformation, 23, 1, 49-53.

328 Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon International Journal of Communication 3(2009)

Isbister, J. (2001). Promises not kept: The betrayal of social change in the third world. Connecticut:

Kumerian.

Keane, M. (2002). As a hundred television formats bloom, a thousand television stations contend. Journal

of Contemporary China, 11, 30, 5-16.

Keane, M., & Moran, A. (2005). Re-presenting local content: Programme adaptation in

Asia and the Pacific. Media International Australia (Culture and Policy), 1-11.

Krishnamurthy, V. (2005). The media and campaign reform. In R. McChesney & R.

Newman, (Eds.), The future of media: Resistance and reform in the 21

st

century (pp. 141-148).

New York: Seven Stories Press.

Lee, P. S. (2003). Reflections on mergers and TNC influence on the cultural autonomy of developing

countries. In Goonasekera, A, Hamelink, C. & Iyer, V. (Eds.) Cultural rights in a global world, 47-

56. New York: Eastern Universities Press.

Machin, D., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2004). Global Media: Generic Homogeneity and Discursive Diversity.

Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 18, 1, 99-120.

Malbon, J., & Moran, A. (2006). Understanding the global TV format. Intellect Limited.

Maxwell, R. (2003). Key thinkers in critical media studies: Herbert Schiller. Lanham: Rowman and

Littlefield Publishers.

McChesney, R. (2004). The Problem of the media: U.S. communication politics in the 21

st

century. New

York: Monthly Review Press.

McChesney, R. (2005). The emerging struggle for a free press. In R. McChesney & R. Newman, (Eds.),

The future of media: Resistance and reform in the 21

st

century (pp. 9-20). New York: Seven

Stories Press.

McCormick, P. (1994). [Content analysis of television programming in Jamaica] Unpublished raw data.

McCormick, P. (1999). [Content analysis of television programming in Jamaica] Unpublished raw data.

McCormick, P. (1999). Television programming in Jamaica: Sunday March 28 through Saturday April 3,

1999. Unpublished manuscript.

McLeod, A. (2005). Globalization, markets, and the ideal of economic freedom. Journal

of Social Philosophy, 36, 2, 143-148.

McPhail, T. (2002). Global communication: Theories, stakeholders, and trends. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

International Journal of Communication 3 (2009) Globalization and Cultural Imperialism in Jamaica 329

Melkote, S. (2000). Reinventing development support communication. In K.G. Wilkins, (Ed.),

Redeveloping communication for social change: Practice theory and power (pp. 39-53). New

York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Melkote, S., & Steeves, L. (2001). Communication for development in the third world:

Theory and practice for empowerment, 2

nd

ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Mody, B. (2000). The contexts of power and the power of the media. In K.G. Wilkins, (Ed.), Redeveloping

communication for social change: Practice theory and power (pp. 185-195). New York: Rowman

and Littlefield.

Mojto, J. (1998). Strengthening the competitiveness of the European audiovisual industry. Paper

presented at the European Audiovisual Conference, Birmingham, London, April 6-8.

Murray, S. (2005). Brand loyalties: Rethinking content within global corporate media. Media, Culture and

Society, 27, 3, 415-435.

Nettleford, R. (1979). Caribbean cultural identity: The case of Jamaica. Los Angeles, California: UCLA Latin

American Centre Publications.

Neveu, E. (2004). Government, the state, and media. In Downing, A., McQuail, D., Schlesinger, P.,

Wartella, E. (Eds.) The sage handbook of Media Studies, 331-350. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Pacey. P. (1985). Cable television in a less regulated market. Journal of Industrial Economics, 34, 1, 18-

91.

Pact. (2005). UK TV dominates the global programme formats market.

Paredes, R. D. (2003). Privatization, and regulation: Challenges in Jamaica. Inter-America Development

Bank.

Parsons, P., & Frieden, R. (1998). The cable and satellite television industries. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Peet, R. (2003). Unholy trinity: The IMF, World Bank and WTO. New York: Zed Books. Pfennig, W. (1979).

The transplantation of media: Some preliminary questions and remarks. In P.Hermann and R.

Kabel, (Eds.), Media technology and development: The role of media adapted by developing

countries (pp. 48-51). Berlin: R. Sperber, Dialogus Mundi.

Price, M. E. (2002). Media and sovereignty. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Reeves, G. (1993). Communications and the ‘Third World.’ New York: Routledge.

330 Nickesia Stacy Ann Gordon International Journal of Communication 3(2009)

Salmon, K. (1996). The development game: Jamaican broadcasting’s longest running show. Unpublished

Thesis. London: Queens University Film Studies.

Schiller, H. I. (1991). Not yet the post-imperialist era. Critical Studies in Mass Communications, 8, 13-28.