Original Paper

Experiences With Wearable Activity Data During Self-Care by

Chronic Heart Patients: Qualitative Study

Tariq Osman Andersen

1*

, DPhil; Henriette Langstrup

2*

, DPhil; Stine Lomborg

3*

, DPhil

1

Department of Computer Science, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

2

Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

3

Department of Communication, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

*

all authors contributed equally

Corresponding Author:

Tariq Osman Andersen, DPhil

Department of Computer Science

University of Copenhagen

Universitetsparken 5

Copenhagen, 2100

Denmark

Phone: 45 26149169

Email: [email protected]

Abstract

Background: Most commercial activity trackers are developed as consumer devices and not as clinical devices. The aim is to

monitor and motivate sport activities, healthy living, and similar wellness purposes, and the devices are not designed to support

care management in a clinical context. There are great expectations for using wearable sensor devices in health care settings, and

the separate realms of wellness tracking and disease self-monitoring are increasingly becoming blurred. However, patients’

experiences with activity tracking technologies designed for use outside the clinical context have received little academic attention.

Objective: This study aimed to contribute to understanding how patients with a chronic disease experience activity data from

consumer self-tracking devices related to self-care and their chronic illness. Our research question was: “How do patients with

heart disease experience activity data in relation to self-care and chronic illness?”

Methods: We conducted a qualitative interview study with patients with chronic heart disease (n=27) who had an implanted

cardioverter-defibrillator. Patients were invited to wear a FitBit Alta HR wearable activity tracker for 3-12 months and provide

their perspectives on their experiences with step, sleep, and heart rate data. The average age was 57.2 years (25 men and 2 women),

and patients used the tracker for 4-49 weeks (mean 26.1 weeks). Semistructured interviews (n=66) were conducted with patients

2–3 times and were analyzed iteratively in workshops using thematic analysis and abductive reasoning logic.

Results: Of the 27 patients, 18 related the heart rate, sleep, and step count data directly to their heart disease. Wearable activity

trackers actualized patients’ experiences across 3 dimensions with a spectrum of contrasting experiences: (1) knowing, which

spanned gaining insight and evoking doubts; (2) feeling, which spanned being reassured and becoming anxious; and (3) evaluating,

which spanned promoting improvements and exposing failure.

Conclusions: Patients’experiences could reside more on one end of the spectrum, could reside across all 3 dimensions, or could

combine contrasting positions and even move across the spectrum over time. Activity data from wearable devices may be a

resource for self-care; however, the data may simultaneously constrain and create uncertainty, fear, and anxiety. By showing how

patients experience self-tracking data across dimensions of knowing, feeling, and evaluating, we point toward the richness and

complexity of these data experiences in the context of chronic illness and self-care.

(J Med Internet Res 2020;22(7):e15873) doi: 10.2196/15873

KEYWORDS

consumer health information; wearable electronic devices; self-care; chronic illness; patient experiences

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 1https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Introduction

Consumer Wearable Activity Trackers in Chronic

Care

Consumer health information technologies such as wearable

activity trackers are increasingly being considered to improve

chronic care management [1-4]. Contrary to traditional health

information technologies, these devices are developed as

consumer devices and not as clinical devices. Most commercial

activity trackers aim to monitor and motivate sport activities,

healthy living, and similar wellness purposes. Wristbands such

as Fitbit and smart watches that track bodily signs (eg, heart

rate) do not provide diagnostic services or disorder-specific

information, and they are regulated less rigorously than are

monitoring devices aimed at specific patient groups and clinical

measures. This makes them readily available to consumers.

Moreover, their designs aim at easy and noninvasive integration

into everyday life, by way of automated tracking. These features

are attractive for application in chronic disease management,

where a healthy lifestyle can be a central part of treatment,

rehabilitation, and prevention [1,5-8].

The separate realms of “wellness tracking” and “disease

self-monitoring” and “activity data” and “medical data” are thus

blurred, which is somewhat mirrored in an increasing

prominence of concepts such as “patient-generated health data”

and “personal health technology” where the focus is on the

individual producer of data, rather than on the specific context

or purpose of use. Applying leisure activity tracking to chronic

care management provides new opportunities but is often based

on assumptions about what characterizes these devices: easy,

applicable, user-friendly, empowering, and motivating

technology that can collect data with relevance for self-care and

treatment. While there are great expectations and promising

results emerging [2,3,9], little attention has been paid to the

embodied and embedded experiences of self-tracking among

patients with a chronic disease using consumer devices, which

are not integrated in the health care system.

In this paper, we explored how patients who use consumer

wearable devices make sense of them and of the data they

produce and display vis-à-vis their embodied disorders. We

recruited 27 patients with chronic heart disease who had an

implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) to wear a Fitbit

wearable tracker to understand the experiential qualities of how

they relate self-tracking and activity data to their disease to

explore the question: How do the embodied experiences and

self-care practices of dealing with a specific health condition

respond to the introduction of activity trackers?

Background and Significance: Experiences with

Self-Monitoring in Health Care and Leisure Contexts

The existing literature of experiences with self-tracking

comprises two related fields: (1) rich literature on how patients,

as part of their prescribed treatment, engage in and make sense

of clinically validated data related to self-care for chronic

illnesses and (2) emerging literature that primarily explores

users’ experiences with leisurely oriented self-tracking

technologies that are outside of the health care system. Patients’

experiences with consumer activity-tracking technologies

designed for use outside the clinical context have received scant

academic attention. There is an important research gap in

understanding the relation between the rich human-information

interaction and the contexts of activity tracking such as self-care

[1,10]. Consequently, studies that explore the experiences of

people coping with illnesses — while recognizing the specific

ramifications that self-tracking might have for those who have

severe health problems — are necessary.

Self-Care and Chronic Illness in eHealth

Many patients routinely engage with data from digital devices

that are part of the prescribed treatment. These clinically

integrated data-producing devices affect self-care activities as

they enable managing symptoms, taking medicine, dealing with

the emotional impact, and tackling lifestyle changes [11-13].

Fostering self-care has been a central ambition of much telecare

and electronic health (eHealth) development during the last 20

years. Early telecare technologies were typically designed from

a clinical standpoint with measures to support remote decision

making such as blood glucose tracking in diabetes [14,15],

oxygen saturation, pulse rate and respiration rate tracking in

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [16], and heart

arrhythmia detection through remote monitoring of cardiac

implantable electronic devices such as pacemakers and ICDs

[17]. In recent years, a more participatory agenda frames eHealth

innovation, aiming to enhance independence and enable patients

to become more active participants in managing their own

disorder (eg, through use of wearable activity trackers) [18,19].

While much research has focused on measurable outcomes of

digital self-tracking and self-management on clinical parameters,

emergent studies have also explored the experiential qualities

of patients’ “data work” [20-22]. Central to such data work,

along with the experiential qualities of patients engaging with

self-tracking data in chronic care management, are the affective

aspects. It is known that self-monitoring of blood glucose data

by patients with diabetes and their caretakers is tightly bound

to an emotional struggle ranging between control and freedom,

peace of mind and anxiety, and empowerment and the burden

of managing technology [23]. Similarly, it is found that

self-tracking data in fertility self-monitoring promotes the

achievement of certain positive goals but may accentuate

negative emotions such as feeling burdened or abandoned [24].

Others have studied patient experiences in heart arrhythmia

telemonitoring and found that not having access to data or

feedback from clinicians has an emotional and life-changing

impact, which in turn creates doubt, guilt, and concern [25].

Self-Tracking and Activity Data

While clinically validated self-monitoring technologies have

become the standard in chronic care, the rise of low-cost sensors

has accelerated the consumer market, making wearable activity

trackers and mobile data-logging applications a widespread

commodity. Large corporations like FitBit and Apple are

entering the medical domain with consumer wearable devices,

most prominent through automated activity measures like step

count [1,26] to support disease monitoring and rehabilitation

of cardiac, pulmonary, and cancer patients [8,27-29], among

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 2https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

others, and most recently, through large-scale interventions

using the Apple Watch for screening of atrial fibrillation.

Literature on the so-called Quantified Self over the past decade

has explored users’ (ie, self-trackers) experiences with these

technologies and the data they produce when applied voluntarily

for leisure or wellness activities [30-34]. Lomborg and Frandsen

[35] showed that, while self-tracking is often depicted as an

entirely individual endeavor to retrieve calculable, reliable

knowledge, it is experienced by users as a deeply communicative

activity, with an often playful and pleasurable quality to it.

In their exploration of self-tracking cycling, Lupton et al [36]

presented the concept of “data sense” to describe how people’s

experience with data from sensors is not just a matter of

cognitive “knowing” — as often assumed in data literacy

approaches — but equally involves sensory and affective

dimensions such as alerting cyclists to new bodily sensations

while possibly invoking feelings of frustration or even

embarrassment. Thus, what emerges are accounts of

self-tracking experiences as complex encounters between the

metric and sensuous, between knowing and feeling. This, in

turn, suggests that self-tracking, while often a purposeful and

systematic practice, is not necessarily guided by goals of

improving the self, forming new and healthier habits, or getting

to know oneself better, as suggested by many of the wellness

technologies currently entering the market [37].

The critical question is then: what happens when technologies,

practices, and data from the consumer market for self-tracking

are introduced in the context of chronic self-care? What kinds

of experiences do they offer in a setting where self-tracking is

“pushed” [38] to patient-consumers who live with a chronic

disorder?

Several studies have examined patients’ experiences with

wearable activity trackers, and the focus tends to be on patient

acceptability and feasibility among the elderly [39-41] and in

the chronic care context [1,5-8,28]. Some support positive

outcomes like ease-of-use and willingness among patients to

wear activity trackers and integrating them into clinical care

[5,28]. Rosenberg et al [28] conducted a 3-week study

examining the acceptability of the Fitbit Zip and attitudes

towards integrating fitness tracking into clinical care among

men with prostate cancer. All participants were willing to wear

the device and endorsed its value in ensuring they engaged in

a “minimal amount of activity.” However, several barriers to

use were found, including health-related limitations (like pain

and injuries making it difficult to walk) and practical or technical

problems with syncing devices and experiencing data

inaccuracies (eg, not capturing the activities).

Other studies present negative aspects and challenges with

integrating patient-generated data in clinical settings [6,7]. Zhu

et al [6] found technical challenges (such as security and privacy

issues and the practical work of clinicians transferring

self-tracking data to the electronic medical record), social

challenges (such as health professionals adapting to new forms

of care where patients are collaborative partners), and

organizational challenges (like organizational policies and

workflows that do not include attending to patient-self tracking

data). Ancker et al [7] conducted an interview study to explore

self-tracking among patients with multiple chronic conditions.

They found that patients associated several negative experiences

with self-tracking and self-tracking data can negatively influence

the patient-clinician relationship owing to a lack of trust in the

data. For these patients, self-tracking thus became burdensome,

which contrasts the pleasurable and playful experiences

promoted in wellness self-tracking.

Objective

The objective of this study was to understand how patients with

chronic heart disease, as opposed to healthy individuals,

experience activity data from consumer self-tracking devices

when engaging in self-care. With this study, we contribute to

the emergent literature on how patients’ experiences with

consumer wearable activity trackers are related to their illness

and their self-care activities and the implications that arise for

design and deployment of these devices. There is a need for

going beyond acceptability and feasibility studies and

conducting more fine-grained analysis of the experiential

qualities of interacting with personal health data outside the

context of clinical practice among the increasing number of

people with chronic illnesses.

Methods

Overview

We conducted a qualitative study to understand how patients

with an ICD experience self-tracking of activity data in relation

to their embodied condition and daily practices of dealing with

a chronic heart condition. As we know from the self-tracking

literature, such experiences may change over time [33]. To grasp

this, we followed patients over a 49-week period from January

2018 to December 2018, during which we observed their activity

tracking data and interviewed them repeatedly (2-3 times each)

about their experiences and insights gleaned from the data.

Setting

This study was part of a larger research and development project,

SCAUT (Self-, Collaborative- and AUTo-detection of signs

and symptoms of deterioration), 2014–2018, which aimed to

improve early detection of deterioration and communication

among patients with a cardiac device and health professionals.

The overall project was carried out at a cardiac device clinic at

the Rigshospital, University of Copenhagen, Denmark, which

is one of the largest cardiac device remote monitoring centers

in Europe, following more than 3500 patients.

Recruitment of Participants

The study comprised a sample of 27 patients with chronic heart

disease who had a secondary prevention ICD and were already

part of an (R&D project). Secondary prevention ICDs were

offered to individuals who survived sudden cardiac arrest or

had a history of dangerous and recurrent abnormal heart

rhythms, which is relevant for this study due to the chronicity

of the disease and related self-care activities. While patients

were similar in having an ICD, their underlying cardiac

diagnosis, possible comorbidities, and psychosocial situation

differed substantially. Participants were recruited through a mix

of purposive sampling and self-signup to ensure that patients

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 3https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

were interested and not too ill to participate. Of the 65 ICD

patients we invited to participate, 27 ICD patients provided

written informed consent to this study, which explored the

experiences of activity data as related to being an ICD patient

and the data’s potential for predictive analytics of dangerous

arrhythmias. Of the 27 patients, 25 patients were male (93%),

and 2 patients were female (7%); the average age was 57 years.

The sample largely reflected the demographic profile of ICD

patients in Denmark in 2017, when 18% of patients were female

and the majority of procedures were carried out on patients aged

55-74 years [42].

The participants were provided with and instructed to wear a

Fitbit Alta HR (Fitbit, San Francisco, CA), which is a wristband

activity tracker that can record and visualize heart rate, sleep,

and steps onscreen and in a Fitbit mobile app. They were

informed that wearing the activity tracker was unrelated to their

treatment at the clinic and that our purpose was to explore how

they experience the relationship between activity data and their

heart disease.

Data Collection: Semi-Structured Interviews

Data were collected with 66 semistructured interviews in 3

overall iterations using 3 interview guides. The first iteration

aimed to create a baseline of patients’ expectations concerning

activity-illness relationships and get a sense of their embodied

experience of everyday living with an ICD. The second iteration

aimed to understand the initial 2-week experiences with activity

tracking using concrete examples from their own tracking data

and asking them what they had learned or wondered about when

using the Fitbit and looking at the data. The third iteration aimed

to understand the longer-term experiences and data-sensing

practices and any ambivalences arising from using the Fitbit

(4–49 weeks).

Patients were interviewed individually (sometimes with

relatives) in their homes or in locations convenient to them (eg,

workplace or hospital office space). Each interview lasted

between 25 minutes and 1 hour and 40 minutes. During

interviews, the interviewers took field notes and pictures of

participants showing concrete examples of activity data in the

Fitbit mobile app to support the analysis of the data. All

interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed either in full or

in selected passages.

Data Analysis

The interview transcripts were hand-coded iteratively, following

an abductive reasoning logic [43,44], starting with a joint

analysis workshop after the second interview with all 27 patients

to identify emergent themes regarding data sensing and insights

from the data to be followed up in the final interviews. At this

stage, field notes and pictures from the interviews offered an

interpretive aid, offering contextual guidance for those of us

who had not been present at the interview. Upon the final round

of interviews, another joint workshop solidified and elaborated

the initial insights and ideas against the body of related work,

to develop a joint analytical framework and coding protocol.

This framework combined dimensions of data sensing —

knowing, feeling, and evaluating the self through data with

contextual embedding and experiences of illness in daily chronic

living [45] — to clarify how patients with an ICD make sense

of Fitbit data relating to their heart disease. Finally, we recoded

the complete empirical material manually according to these

dimensions, first individually and then together, to ensure

reliability in producing a thematically organized analysis of

patients’ data sensing [46].

Study Approval and Ethical Considerations

This paper was based on a substudy of the SCAUT research

and development project, which was approved by the Danish

Data Protection Agency and reviewed by the National Board

of Health and Danish National Committee on Health Research

Ethics (H-19029475). We took several measures to respond to

possible ethical concerns. First, we ensured voluntary

participation through an open invitation with self-signup, and

we emphasized in interviews that participants could opt out at

any time. Second, we communicated with all participants

between interviews to ensure they were comfortable with

wearing the wristband. We made sure that the participants

understood that the Fitbit activity tracker was a consumer device

and not a clinical device and that the data did not have diagnostic

validity. Finally, we adjusted the conversation in interviews

accordingly if patients expressed specific health concerns

brought on by their interaction with the Fitbit; specifically, we

urged them to contact their health professional for guidance.

Results

Device Engagement

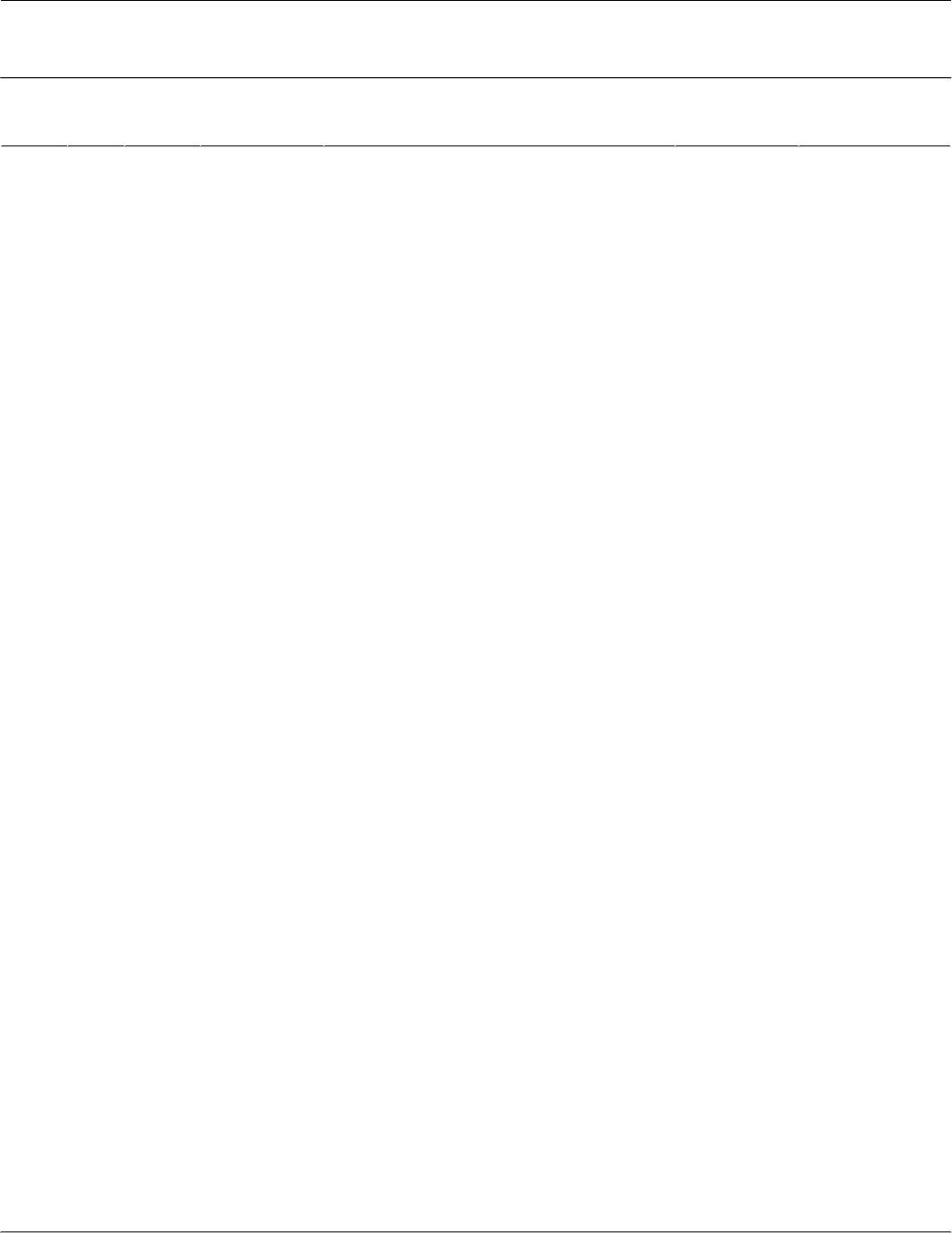

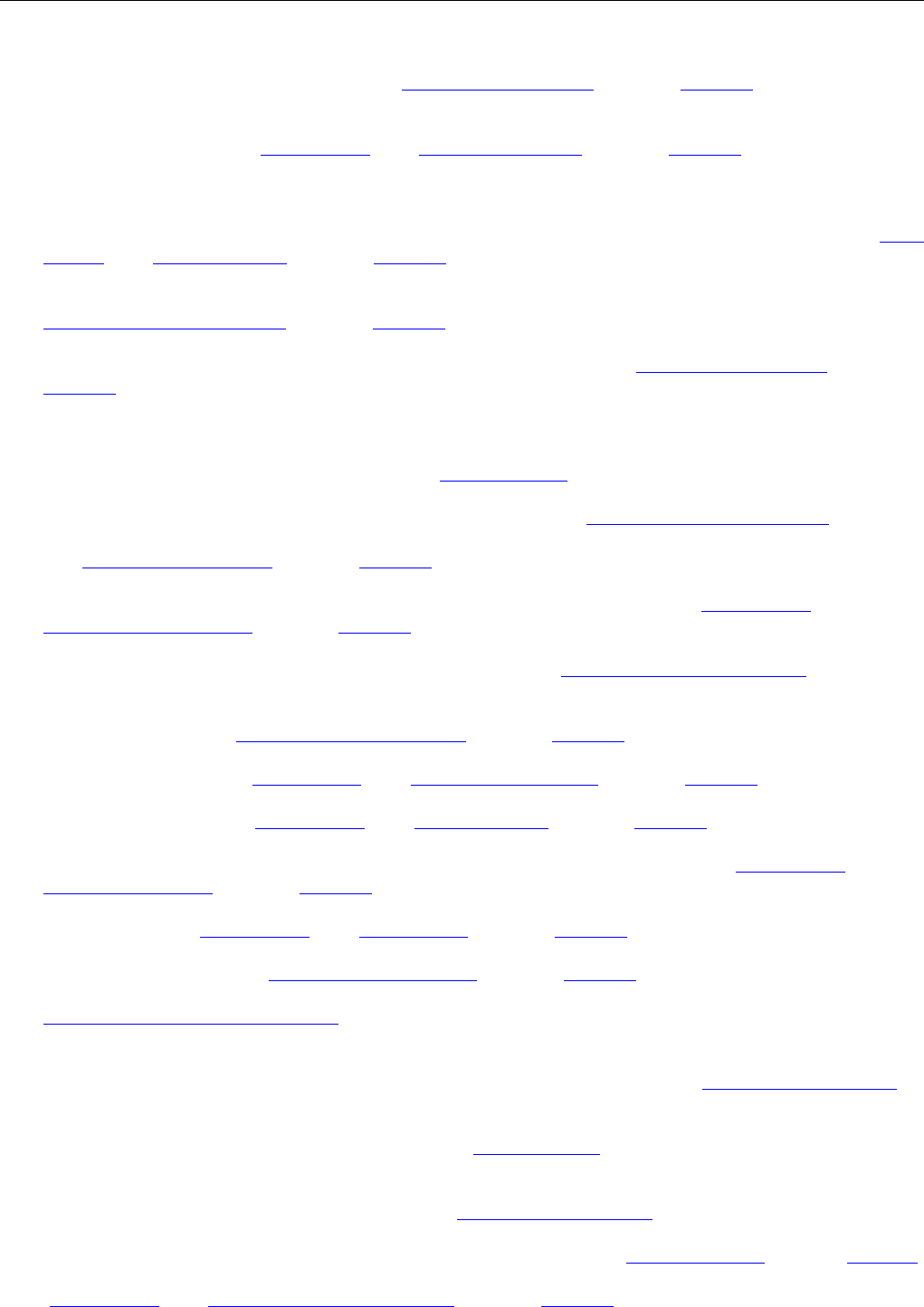

Our results showed how patients with an implanted ICD device

engaged with and made sense of activity data from the Fitbit in

the context of chronic illness and self-care. Most (18 of the 27

participants) related their real-time heart rate, sleep, and step

count data directly to their heart disease (Table 1). The

remaining participants, however, connected the data to leisure

activities, wellness, and exercise. Some portrayed themselves

as not being a patient, explaining that they mostly did not have

symptoms. Two patients chose to opt out after only wearing the

tracker a few times owing to finding the wristband annoying to

wear or simply losing interest (P6, P7). Patients used the activity

tracker for an average of 26.1 weeks and took breaks from using

it an average of 5.9 weeks.

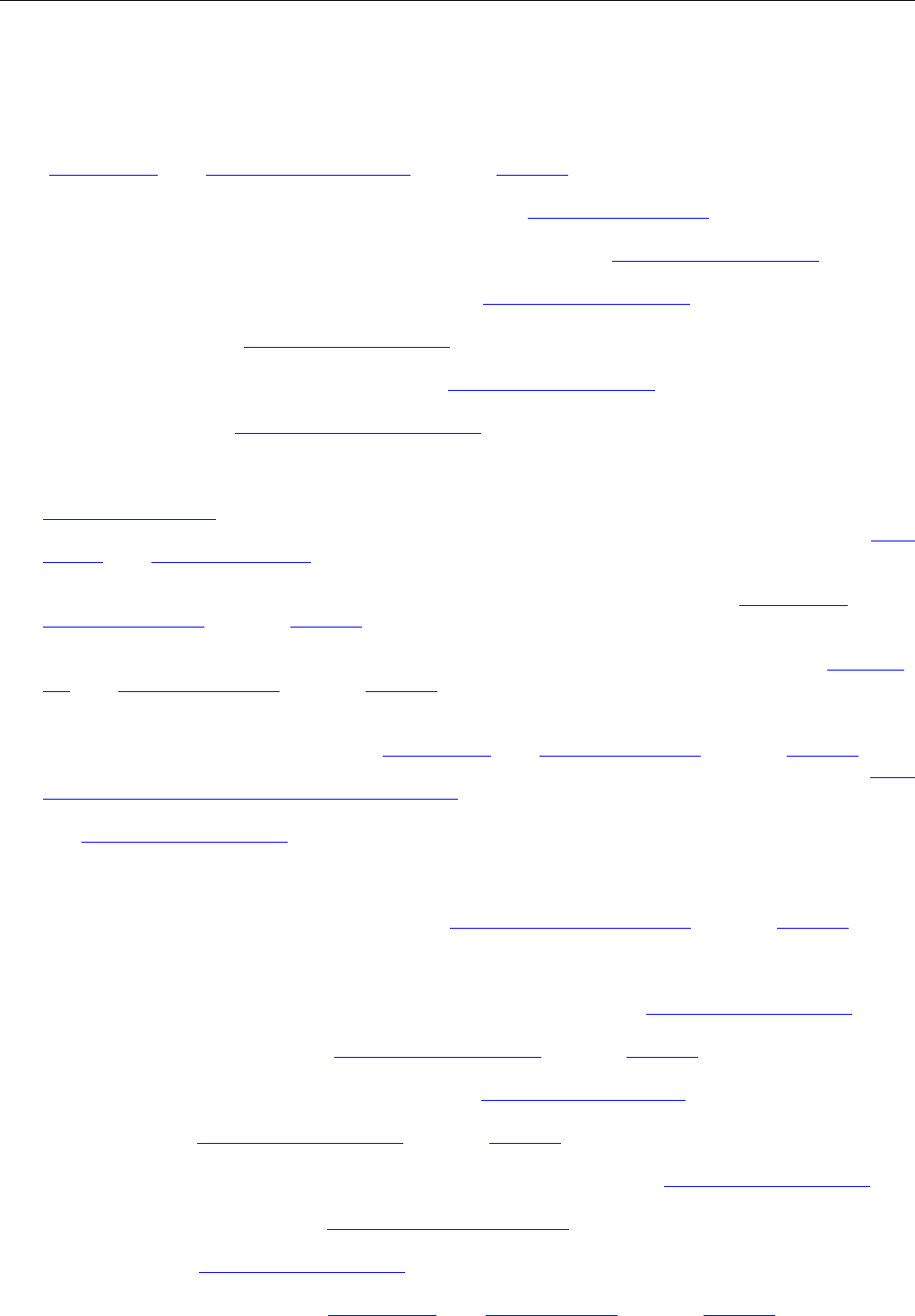

The patients who did relate the data directly to their illness did

so in 3 overall dimensions (Table 2): as something that generated

new knowledge, as something that raised affective responses,

and as something that could be used to evaluate themselves and

their overall health. Within these 3 dimensions of experience,

patients accounted for a range of positive, negative, and

ambivalent experiences with activity data. For an extended

analysis of the affective dimension and the consequences for

patients’ interpretation of Fitbit data, see [47].

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 4https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

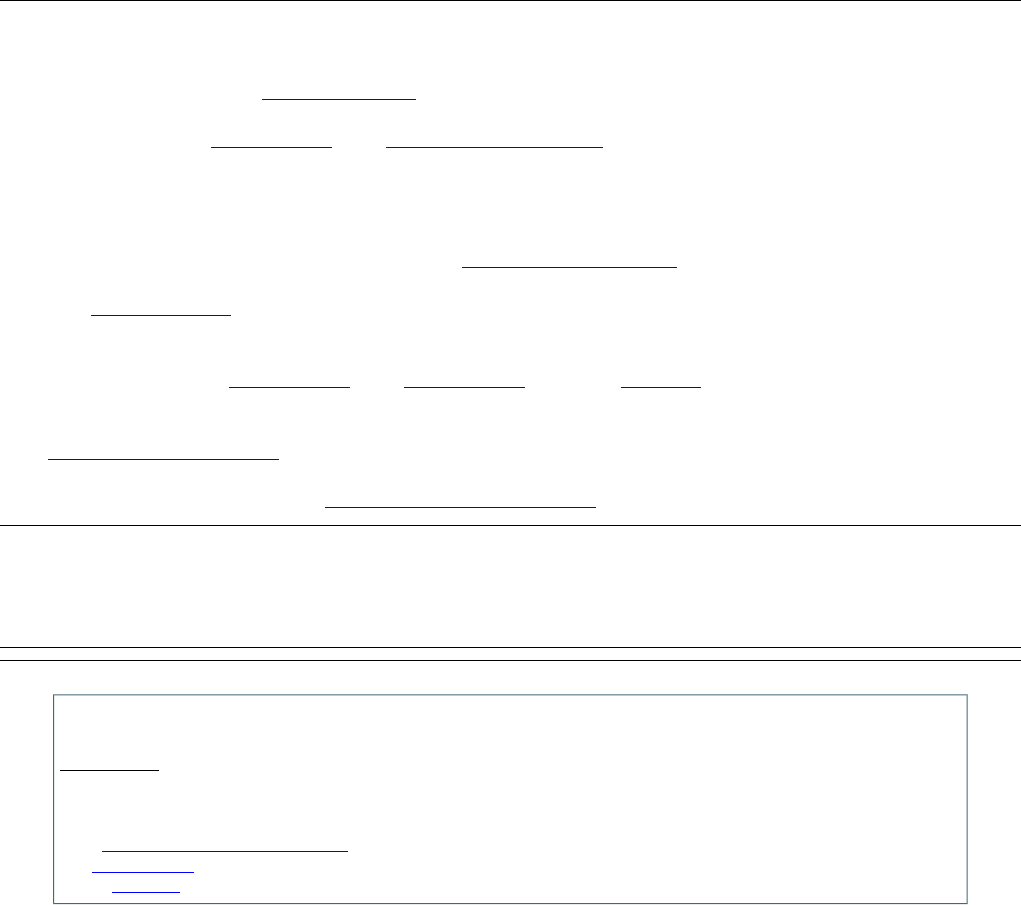

Table 1. Overview of participating patients with chronic heart disease and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (n=27).

Experienced Fitbit da-

ta relating to heart

disease

Number of weeks

using the Fitbit

(not using)

Symptoms experienced

Year of ICD

a

implant

SexAge

(years)

Patient

number

No18 (0)

No symptom experiences; experienced palpitations

before1998Male67P1

Yes47.5 (0.5)Severe chest pain and shortness of breath2015Male61P2

No41 (6)

No symptom experiences; experienced shortness of

breath before2009Male41P3

Yes13 (5)Dizziness and sometimes fainting2014Male55P4

Yes8 (23)Dizziness and sometimes fainting2010Male66P5

N/A

b

9.5 (1.5)No symptom experiences2015Male67P6

N/A6 (3)No symptom experiences2008Male28P7

Yes36.5 (11)No symptom experiences (primary prophylaxis)2015Male69P8

Yes33,5 (14.5)No symptoms experiences related to his heart disease;

lung disease; difficulties exercising

2008Male47P9

Yes30 (8)Sometimes feeling very tired2010Male61P10

Yes8.5 (0.5)Shortness of breath and sometimes sleep problems;

finds it difficult to feel his heart rate

2006Male59P11

Yes49 (0)Dizziness and sometimes fainting; anxious about get-

ting a shock and experiences depression

2015Male66P12

Yes44.5 (0.5)No symptom experiences; rarely experience fainting;

leg tenderness and muscle fatigue

2017Male67P13

No49 (0)No symptom experiences2008Female52P14

Yes14 (1)No symptom experiences; sometimes being anxious

about the ICD/irregular heartbeats

2004Female61P15

No35.5 (11.5)Dizziness and sometimes fainting2014Male47P16

Yes35 (7)Dizziness and shortness of breath during high activity

levels

2013Male45P17

Yes18 (29)No symptom experiences2009Male67P18

No20.5 (1.5)Palpitations daily; experiences periods of depression

and has restless leg syndrome

2005Male66P19

Yes39.5 (8.5)No symptom experiences, except sometimes shortness

of breath

2014Male69P20

Yes13.5 (0)No symptom experiences; worries daily about having

a cardiac arrest again

2008Male38P21

Yes19.5 (0.5)Shortness of breath and sometimes dizziness when

exercising and running; rapid heartbeats and chest pain

2001Male59P22

Yes47 (2)No symptom experiences2017Male49P23

Yes42.5 (6)No symptom experiences2017Male74P24

No9 (15)No symptom experiences2014Male51P25

No4 (0)No symptom experiences; sometimes feels palpitations

and shortness of breath

2010Male56P26

Yes12 (5)Shortness of breath; sometimes sleep problems; knee-

pain due to osteoarthritis

2014Male58P27

a

ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

b

N/A: not available because the patient did not describe a relation between the activity data and his or her heart disease.

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 5https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Table 2. Dimensions of how patients experienced activity tracking related to their disease.

ExperienceExperiential dimension

Knowing

Learning that heart disease increases one’s average resting heart rate (P2, P4)Positive: gaining insight

Learning that medication influences the heart rate (P5, P22, P23, P27)

Learning that activity improves one’s average heart rate (P4, P21)

Using activity data to monitor heart pumping ability (P10)

No new learnings: Sensing is more useful than activity data (P1, P5, P16, P22)Negative: evoking doubts

Doubting heart rate data (P2, P22)

When doubt becomes mistrust (P12)

Feeling

Feeling safe through Fitbit reassurance (P11, P12, P17)Positive: being reassured

Reassurance prompts activity (P24)

Both insights and doubts can introduce new anxieties (P12, P13, P15, P23)Negative: becoming anxious

Evaluating

Being nudged and getting praise (P19, P20, P23, P24)Positive: promoting improvement

Recognizing a nudge but not knowing what to do about it (P13)Negative: exposing failure

Not getting the proper reward: the invisibility of “good” activities (P18)

Self-disappointment with poor numbers (P8, P17, P24)

Ignoring or resisting nudges (P18, P19)

Knowing: Gaining Insight and Evoking Doubts

As part of their motivation for participating in the study, many

participants expressed an interest in knowing more about their

health and body and about the possible relationships between

their daily activities and their heart. In our interviews, it became

clear that patients actively sought knowledge about their heart

and health through the readings on the Fitbit and that some

gained insight from the data. For others, the knowledge they

gained from sensing their own bodies was more useful than the

Fitbit data. Finally, some participants experienced that the data

did not align with their activities and sensory experiences; thus,

they doubted the accuracy and trustworthiness of the data.

Learning That Heart Disease Increases One’s Average

Resting Heart Rate

One patient gained insight into his average resting heart rate

and discovered it was higher than he expected:

My resting heart rate ought to be 60, but it is 80, and

as soon as I start moving, it goes up to 100 or 120.

[P2]

It did not concern him since there is not much the clinicians can

do about it, as he said. Another patient had the same kind of

insight:

Then, the pulse is in a zone where I am physically

active. That is what it signals. But I am not physically

active. I am just walking. That has been an

eye-opening experience. [P4]

Learning That Medication Influences the Heart Rate

Several patients knew, speculated, or learned about how

medication can affect the heart rate. By looking at the Fitbit

data, P5 noticed that his average heart rate decreased when on

vacation, and he considered that his medication might have an

effect. P27 also noticed that his medication influenced his heart

rate:

Obviously, the heart rate follows how active you are;

but, for healthy people, it’s not abnormal that it

reaches 116. But I get 13 pills in the morning and 3

in the afternoon.

P23 also noticed that medication influences his heart rate:

My beta blockers have been reduced in dose, which

may also have something to do with the changes in

the resting heart rate.

P22 had always been exercising; however, after an event a few

years ago, he was prescribed a double dosage of beta-blockers,

and it was decided to reduce the dosage again because his heart

rate had dropped too low. Now, he finds it exciting to use Fitbit

to learn about the relationship between medication, exercise,

and heart rate and to confirm his heart rate data:

I still monitor what happens. This morning I saw an

increase in my average heart rate of 12% and my

maximum heart rate of just over 15%. And that's

what’s fun and what I use it for because it has

annoyed me extremely that I couldn't run like I used

to.

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 6https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Learning That Activity Improves One’s Average Heart

Rate

P21 noticed that there is a relationship between exercising and

average heart rate:

After serious ice hockey training, the average heart

rate is higher on the day after, and then it drops in

the weekend.

Similarly, P4 discovered that when he is more active, his average

heart rate drops:

During the 20 days I have been wearing the Fitbit, I

have seen a drop in my heart rate by 10 heartbeats

per minute. I think that’s crazy. I have been more

active, yes, and I have been walking more. I have set

exercise goals.

He experienced this as a positive thing:

I think it’s fine that my resting heart rate goes down

because, if it goes down, the heart does not have to

work as hard. It makes a difference whether my heart

rate is 70 or 60 beats per minute when resting.

Using Activity Data to Monitor Heart Pumping Ability

Several patients had experience with other activity trackers.

One patient (P10) described how he used the data to monitor

his heart condition. He was diagnosed with heart failure, and

his heart had a reduced pumping ability, “Down to around half

of what is normal,” he said. He used the Fitbit to address his

concern that his heart rate will drop even lower:

I use it to keep an eye on my condition. When I go

spinning, I do the same intervals, and I can therefore

see if I have burned the same calories in that hour.

So, I can say, okay, I'm fairly stable, or I can see if it

has gone down. Because then it might be my heart

getting worse in its ability to pump.

No New Learnings: Sensing is More Useful Than

Activity Data

Several patients had learned over the years to sense

developments in their heart condition. One patient explained

that, in the past, when he got rapid and dangerous heartbeats

and the ICD began treatment with antitachycardia pacing to

terminate the arrhythmia, he sat down and waited until it passed.

He used to call the Heart Centre when he felt the symptoms to

get confirmation about the episodes. For him, the Fitbit did not

generate any new insights apart from what he already knew

from sensing and listening to his body when exercising in the

gym:

I know I cannot do physically very demanding

exercises. I have come to terms with that. So, I have

not received any new extra information via Fitbit.

[P1]

P22 found it useful to use the activity tracker to get confirmation

on fast heartbeats, for example, when running in the woods.

However, he trusts his senses more:

If there is a connection between what I feel in my body

and what the tracker shows, then I react. But when

the tracker shows something that I don’t notice in my

body, I consider it an IT error.

Another patient explained that he has tried to look at the Fitbit

data when he gets sudden dizziness; however, it provides no

explanation:

Sometimes I suddenly experience a “dive,” and then

I just have to hold on to something. It’s very different

how often it happens. But when I look at [the Fitbit

activity data], it does not show anything. So, I can’t

find the reason for getting so dizzy. [P5]

Similarly, P16 explained that there is no connection between

symptoms and heart rate:

There is no connection. I've tried to get symptoms

when doing gymnastics where I had the pulse all the

way up, and I've tried to get symptoms while I was

sleeping. I have not found any connection at all.

Doubting Heart Rate Data

Heart rate data also created doubt among some participants.

One patient doubted that the heart rate data presented on his

Fitbit were accurate when walking:

But I have seen sometimes when out for a walk, my

heart rate is really high. Average 166—I think that

is a little high. And, sometimes, I have seen it going

up to 197 beats, and I don’t know why. [P2]

Another patient found the heart rate data “weird” at times. He

experienced chest pain a few times when he was out running;

however, no answers could be found in the activity data:

I felt a little uncomfortable — one might suddenly

think of a blood clot. But I can't see in any of the

trackers that the pulse has been particularly high or

particularly low. [P22]

At other times, when he was just walking, there were sudden

peaks in the heart rate data:

It seems strange. It's just right there — a peak up. It

almost seems like a mistake that it goes from 80 to

almost 170. It seems completely messed up what

happens here. [P22]

Several other patients experienced that their heart rate showed

unusual fluctuations on Fitbit.

When Doubt Becomes Mistrust

One patient had disease-related anxiety and had difficulties

sleeping. Initially, the Fitbit data concerning his sleep revealed

that he slept more than he thought he did when he woke in the

morning after a difficult night. However, when he later saw that

the Fitbit had registered “sleep” while he was calmly watching

a movie, he and his wife started distrusting the measurements

of sleep altogether:

This Saturday, we looked at sleep, for instance, and

we could not make the numbers fit because he had

been awake a lot. The data was wrong, and we do not

know how it works. Then you go on to think, can you

trust this device at all? [wife of P12]

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 7https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Across participants, the sleep tracking measures of Fitbit were

noted as unreliable and not reflective of actual sleep. For some

participants, discovering that sleep data were inaccurate led to

mistrust and a general, critical understanding of the

measurements provided by Fitbit.

Feeling: Being Reassured and Becoming Anxious

Being diagnosed with a heart condition often introduces

profound anxiety into patients’ (and their relatives’) lives. It is

well-known that patients with an ICD are at an increased risk

of being diagnosed with depression and anxiety [48]. In our

interviews, some patients had different levels of anxiety and

used the Fitbit to reassure themselves that their heart was doing

okay. For some, this helped them engage more in physical

activity — something they might have held back on owing to

fear of provoking an attack (ie, kinesiophobia) [49]. However,

the Fitbit — partly owing to the doubts and uncertainties

introduced as described — could also spark new and additional

anxieties and negative feelings regarding participants’ health.

Feeling Safe Through Fitbit Reassurance

For some patients, having a heart condition raised their

embodied attention, making them very alert to bodily signs:

As soon as there is even a little thing in these zones

[in his chest region], and I would even say just one,

like a sprain, I get nervous. [P12]

This patient, who is very affected by anxiety and depression,

used the Fitbit to reassure himself that he is not having a cardiac

arrest:

Then, I was out chopping firewood. I felt like it began

to beat both in a weird way, and it felt like it beat

really fast, but it did not. There was nothing. There

was nothing to be seen [on the Fitbit] anyway. [P12]

For this patient, seeing his heart rate within the normal spectrum

reassured and calmed him down:

Now I get certainty. Is something wrong or not.

Another patient, who experienced getting a shock from his ICD

after walking the stairs, explained that:

Being able to see my heart rate is normal creates a

sense of security because I’m not able to feel when

my heart rate rises. A normal rhythm means that there

is nothing to be afraid of — no danger is underway.

[P11]

Similarly, P17 used the heart rate data as support in vulnerable

situations:

I've tried it so many times, to have those VTs [rapid

heartbeat] and I know what it leads to, and that's

what I fear.

One time he was lying down, and he used the heart rate on the

Fitbit tracker to get confirmation on the duration of rapid

heartbeats:

If it lasted more than 5 minutes, I would have called

112 [emergency services]. Because, sometimes, I think

when I get that feeling of fast heartbeats, it may well

be imagination.

Reassurance Prompts Activity

Holding back during physical activity was something several

of the informants touched upon, as some had had a heart attack

while exercising or had experienced an ICD shock when

climbing a flight of stairs. Checking their heart rate while doing

more physically demanding tasks and sports motivated them to

increase their activity:

I’m not afraid to have a high pulse when we do the

Bikefit exercise at gymnastics … because I can see it

goes down again [his heart rate]. [P24]

Both Insights and Doubts Can Introduce New Anxieties

In the first section, we touched upon some of the doubts

concerning the validity of the Fitbit data. For the anxious patient

in need of reassurance, this uncertainty can be stressful, as noted

by the wife of P12. P15 described it as follows:

There are plenty of worries when you have a heart

disease. You don’t need unnecessary things that make

you worry more.

The Fitbit sleep data, for example, created unwanted attention

to what it meant for her health:

What does it mean for my health? Am I sleeping

enough or too little, and what can I do about it? Such

concerns arise, which I could do well without.

She also experienced getting a high pulse that was “completely

unprovoked” and then seeing it on the Fitbit:

But I can't do anything about it, and I can't use it for

anything—unless they can see it in the clinic.

One patient noticed that Fitbit wants him to sleep 8 hours per

night — a goal he rarely reaches:

I have always had this sleep pattern, and it did not

bother me until I got this Fitbit, which says I should

sleep 8 hours a night … I get worried and start to

question whether I ought to sleep more. [P13]

Finally, the introduction of new concerns and anxieties by Fitbit

goes beyond patients’ individual experiences. P23 explained

that he tried to avoid drawing attention to his Fitbit wristband

when being around his teenage kids:

I think it reminds them a little bit of something bad

… it’s interpreted negatively—like someone has to

keep an eye on me.

Evaluating: Promoting Improvement and Exposing

Failure

As we presented in the previous sections, patients used Fitbit’s

numerical representations to make sense of their bodily

sensations in the context of self-care. The fact that the Fitbit

device allows them to see — as numbers, icons, and graphics

— something that they usually relate to as sensations provides

a new form of motivation. Setting targets for activity, getting

notifications, and seeing achievements represented visually can

be encouraging. Concurrently, however, the Fitbit also exposes

unmet goals, thereby inducing self-disappointment or even

shame. The Fitbit does not register or “see” all the activity that

the patients found to be relevant as fair representations.

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 8https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

Being Nudged and Getting Praise

Several of the patients talked about how the Fitbit nudged them

to stay physically active — it is “a kick in the butt,” as one

patient noted (P19). Users can set their activity goals as they

please; however, most went with the default setting of 10,000

steps a day. All patients looked daily to see if they had reached

that goal, and some found it motivating to see the numbers and

get positive feedback (visually provided in the form of stars)

from the user interface. One patient described himself laughingly

as:

Addicted to it because it says you have to walk 10,000

steps a day, and that fits with some of our walks. It

becomes a sport; it gets me going. [P20]

Others noted how the gamification element invoked in the Fitbit

led to small changes in their daily activities. For P23, Fitbit

prompted him to take the stairs instead of the elevator to get

more steps. It also prompted him to get up when it beeped every

hour to take 250 steps by walking up and down the hall during

work breaks. For these patients, Fitbit is “a little push in the

right direction” (P23) and “an inspiration to continue” (P24).

Recognizing a Nudge But Not Knowing What to Do

About It

Whereas simple nudging features such as awarding stars for

accomplishing specific activity benchmarks seemed to motivate

participants, there were also examples of participants becoming

unsure of what constitutes appropriate activity. For example,

Fitbit (by default) beeps once every hour during the day to pace

the wearer to walk 250 steps every hour. For P13, this nudge

suggested that average but regular activity throughout the day

might be preferable to his usual practice of lumping activity

together for more intense periods of exercise. It made him

wonder if he should organize his workout differently, even if

this wondering did not lead him to make any actual change.

Not Getting the Proper Reward: The Invisibility of

“Good” Activities

After wearing the Fitbit for some time and having acquainted

themselves with the collected activity data, some participants

reported being frustrated that the Fitbit did not really measure

all their activity. They did not feel “seen” by the device and

rewarded properly for their efforts. This is particularly the case

for those participants who did cycling, CrossFit, and other

activities beyond walking and running as part of their everyday

life activities. One participant lamented:

It is actually misleading because most of my activity

is on a bike, and it does not register this. But it is also

exercise. [P18]

These experiences added to the doubt in the data and the

accuracy of measurements described previously.

Self-Disappointment With Poor Numbers

If positive feedback is seen as motivating further activity

tracking, conversely, the negative feedback from Fitbit made

some participants feel disappointed with or ashamed of

themselves because it highlighted that they had not been active

enough:

Well, I guess it has to do with that bad conscience

you get the next day, if you cheat. [P8]

This was mentioned by several patients, and, for some, it made

the Fitbit less attractive. P24 talked of self-disappointment when

receiving negative feedback from Fitbit and noted that there

might be someone else looking at their data, surveilling whether

they reached their goals:

Yes, because it gossips all the time, noting that I have

not walked far enough … I think you could always

find an excuse for not walking; like, it’s raining.

For P17, the low step count created negative emotions on “bad

days” and became linked to his heart condition:

It gives me a little guilty conscience that I do not get

much exercise because, I have no doubt, the more

weight I gain, the more fat is generated around my

heart, and the harder it is for the heart to pump.

Ignoring or Resisting Nudges

Some participants tempered their engagement with Fitbit by

actively resisting to do what the device suggests:

I know that it tells me, every once in a while, that it

is time to go for a walk. But I decide when it is time

to go for a walk. And then it says, let’s go, and I’m

like no way because I don’t have the time right now.

[P18]

For some, the Fitbit’s nudging was simply a source of

annoyance:

It can be a little irritating watching all the green

“pling pling.” I don’t want that; I don’t care about

it. I just want the info. [P19]

Yet, for others, such as P18, resisting the nudge to walk every

hour was followed by a deeper reflection about whether activity

tracking is good at all for his health:

I actually think it is a little unhealthy to measure

oneself all the time. It comes to take up a lot, in my

life, and I don’t think it is that important.

Discussion

Principal Findings

Our study contributes to understanding how patients with

chronic heart disease, as opposed to healthy individuals,

experience activity data from consumer self-tracking devices

in self-care. We found that patients with an implanted ICD relate

the activity data to their illness experience and their self-care

activities in 3 overall dimensions: as something that generated

new or destabilized existing knowledge, as something that raised

affective responses, and as something that could be used to

evaluate themselves and their overall health.

The distribution of patients’ experiences on a continuum from

positive to negative suggests that activity data had “dual effects,”

which means that the data created as much as it solved the

problem of chronic illness [50]. The problems that people with

chronic illness have to deal with become mediated in new ways

and what may count as “normal,” “good,” “problematic,” or

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 9https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

“bad” may change accordingly. Positive and negative effects

potentially co-exist and support the experiential ambivalence

that studies of self-tracking and activity data have also found

among leisurely users and quantified self-enthusiasts

[22,45,51,52]. The concept of “ambivalence” unites this stream

of research in which patients’ attitudes towards digital health

devices “neither are consistently negative (implied by the notion

of ‘rejection’) nor consistently positive (implied by the notion

of ‘acceptance’)” [45]. Conflicting or ambivalent experiences

appear constitutive of self-tracking: “doubt, guilt, fear, shame,

dismay, disappointment, and hesitation as well as joy, relief,

excitement, enthusiasm, and pride” [51].

Generating knowledge from interpreting activity data is often

portrayed as the essence of self-tracking. For healthy individuals,

it may comprise discoveries about physical performance in

everyday life and adopting healthier behavior [33,35]. For the

patients in this study, performance-oriented and fitness-oriented

development of self-knowledge also surfaced. Patients obtained

new insights about how exercising improves their average heart

rate and that their heart disease may be the reason for a higher

resting heart rate.

Other more disease-specific reflections surfaced as using Fitbit

data to monitor the status and development of heart failure (heart

pumping ability) and speculating about how heart medication

affects the pulse. Unusually high heart rate data created doubt

when walking or when connected to chest pain while running.

Therefore, Fitbit data became part of generating a type of lay

and personal expertise for, at best, supporting day-to-day

self-care activities and living with a chronic disease and, at

worst, creating uncertainty. This kind of “experiential

knowledge” or “patient knowledge” [53-55] is often considered

distinct from medical and scientific knowledge in that it is a

by-product of bodily sensing and coping with daily practicalities

of the disease as well as it is re-appropriated medical knowledge

used to contribute, but also dispute, the biomedical perspective

[55].

For patients, Fitbit data can provide support for self-care with

informational cues alongside bodily sensations and experiences

in the development of “know-now” [53] (ie, understanding what

is going on or deciding what action to take). As opposed to

healthy individuals’ knowledge-making with Fitbit, the

unsupported lay interpretation of medically unvalidated heart

rate data poses a risk for patients taking inappropriate action,

for example, using Fitbit heart rate numbers to diagnose a

cardiac arrest when running and deciding whether to keep on

running or when getting chest pain and becoming dizzy in the

office and then using Fitbit to decide what to do. The practical

implications of patient knowledge generation from Fitbit suggest

that patients should not be left alone with interpreting activity

data as part of self-care. Deploying self-tracking and activity

data in chronic care should be carefully accompanied by a

purposeful clinical intervention such as rehabilitation and

training programs where clinical staff can support patients in

interpreting activity data, and data visualization should be

designed to support meaningful action in the context of self-care.

The affective dimension of self-tracking when living with a

chronic heart disease also emerged as loaded with ambivalence.

Fitbit numbers may provide numerical reassurance, which can

relieve acute anxiety related to unclear bodily sensations and

provide confidence to exercise. Concurrently, heightened

attention to Fitbit data can also introduce new uncertainties and

anxieties. Moreover, it is important to underline that the

reassurance of the Fitbit data is not based on clinical evidence

and, while reduction of acute anxiety is important to patients’

wellbeing, there is a risk that the numbers provide pseudoproof

not sufficiently reliable to indicate anything clinically relevant

about the patient’s condition. Given the prevalence of mental

health issues, such as anxiety and depression, related to heart

disease and the lack of mental health services for these patients,

it is vital to consider the potential negative interactions between

health tracking and mental health. Patients with chronic mental

health comorbidities should not be left to try to cope with serious

mental health issues alone with consumer devices.

Taken together, we see a tension between Fitbit’s promotion of

success and exposure of failure to comply with set standard

activity levels in the actual experience of using Fitbit. The

ambivalence of knowing, feeling, and evaluating one's chronic

health condition against activity data from consumer devices,

as opposed to clinically validated instruments, poses a concern

for how engagement with data is placed in chronic care contexts

as well as the purposes inscribed in the design of these new

devices. In their analysis of ambivalence in mobile health for

HIV care, Marent and colleagues [45] argued for the need to

consider how the tension implied with ambivalence is embodied

by particular bodily conditions and embedded in particular

relationships and environments. Our study concerns people

who, in clinical terms, have a chronic condition; however, the

embodiment of this condition varies among participants. For

some, the disease has a continuous and very challenging

presence related to managing and coping with severe symptoms

(see Table 1), while others tell us they do not feel sick at all.

We suggest that the ambivalence of Fitbit data is more

problematic when used by people who have a chronic condition

and even more so for people who feel very challenged by their

disease.

This relates to a second point about embeddedness. The

ambivalence of Fitbit data should be understood in relation to

its embeddedness in everyday contexts unrelated to clinical

contexts of treatment. To what extent do people in these contexts

have support from others such as relatives, peers, or health

professionals who choose to engage in handling the

ambivalences they encounter? What resources can they mobilize

to act when experiencing doubt, anxieties, or other concerns

when self-monitoring with Fitbit? With our paper being

specifically concerned with patients who engaged with Fitbit

data outside the established relationships of health care

institutions, these questions become critical. Navigating benefits

and harms of this form of active engagement with personal

health data is, to a large degree, dependent on individual

circumstances, resources, and networks, leaving inequalities

potentially less mitigated by public health systems. We find

that these are very central insights to take into account in

research that focuses on how self-care practices can be furthered

by harnessing the power of data and personal health technology.

Too often, this literature focuses narrowly on individual

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 10https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

information processing and empowerment while disregarding

the relational and situational embeddedness of chronic disease

management. It not only neglects insights from health

information-seeking literature, which has convincingly shown

that patients’ information behavior is more often based on

serendipity, avoidance, blissful ignorance, indolence,

bewilderment, and indolence than on rational choices and

reflections [56], but also neglects that self-care practices are

always collective in the sense that they are embedded in complex

sociomaterial relationships [57,58]. What our study further adds

to the literature on self-care and technology, then, is that

technology and data mobilized outside the established

arrangements of health care with consumer tracking devices

may introduce new ambivalences that some patients may have

difficulties managing without professional assistance.

For human-computer interaction research and the design of

activity-data visualization for patients, our study aligns with

the understanding that data supports different levels of reflection

and serves multiple purposes [59]. The implications of our study,

we suggest, is that consumer activity-tracking devices deployed

in health care contexts should be designed to also support

collaborative reflection (ie, “co-reflection”) with health

professionals, rather than focusing mainly on individual

reflection [60]. Research on ways to support the shared work

of tracking [61], co-reflection, and “co-care” [62] might be

necessary to consider for personal informatics research in

chronic self-care [25,47,63].

As an increasing number of people are generating and interacting

with digital and individual health data outside the context of

clinical practice, issues of inequality in health must be

considered. Thus, there are important implications to consider

in this typically optimistic, yet blurred, realm of “personal health

data” (actualized for wellness purposes) and “patient-generated

data” (actualized for clinical purposes).

Conclusions

We presented the findings from an explorative intervention

study of how patients with a heart arrhythmia who have an

implanted ICD experience activity data from Fitbit concerning

their self-care and chronic illness. The aim was to further

emergent literature and offer crucial empirical insight into the

introduction of wellness tracking devices to various forms of

chronic care management and the associated user experiences.

Through repeated semistructured interviews with 27 patients

equipped with a Fitbit wristband, we offer support and further

elaboration on existing work on patients’ ambivalent

experiences. We found that wearable activity trackers actualize

patients’ experiences across 3 dimensions on a spectrum: (1)

gaining new knowledge versus evoking doubt, (2) feeling

reassured versus becoming anxious, and (3) evaluating one’s

health by celebrating improvements and exposing failure. The

experiences of individual patients can reside more on one end

of the spectrum, can reside across all 3 dimensions, or can

combine contrasting positions and even move across the

spectrum over time. While activity data from wearable devices

may be a resource for self-care through reassurance and

motivation, they may also constrain patients and create increased

uncertainty, fear, and anxiety.

The ramifications of knowing, feeling, and evaluating one’s

chronic health condition against activity data from consumer

devices, as opposed to clinically validated instruments, are

largely unexplored. Our study suggests that we need critical

attention in scholarship and health care practice concerning how

engagement with such data is practiced in chronic care contexts,

not least to assess how the purposes inscribed in the design of

these new devices may be molded and twisted in self-care when

meeting the logics, needs, and abilities of patients in different

health care circumstances. Designers and health authorities

should consider this complexity and ambiguity when

determining the usefulness of self-tracking data in chronic

illness.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the patient participants and their relatives who shared their experiences with us for this study. We

also thank Tanja Munk Warmdahl, Amalie Lund Bendtsen, Oliver Carl Clemmensen, Andreas Millarch, and Anders Riis

Vestergaard for their collaboration in interviewing, transcribing, and analysis workshops. This study is cofunded by the Innovation

Fund Denmark #72-2014-1 and the University of Copenhagen, Vital Beats, and Medtronic. This study was also, in part, supported

by a grant from the Danish Velux Foundations #33295.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

1. Shin G, Jarrahi MH, Fei Y, Karami A, Gafinowitz N, Byun A, et al. Wearable activity trackers, accuracy, adoption,

acceptance and health impact: A systematic literature review. J Biomed Inform 2019 May;93:103153. [doi:

10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103153] [Medline: 30910623]

2. Piwek L, Ellis DA, Andrews S, Joinson A. The Rise of Consumer Health Wearables: Promises and Barriers. PLoS Med

2016 Feb;13(2):e1001953 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001953] [Medline: 26836780]

3. Garge GK, Balakrishna C, Datta SK. Consumer Health Care: Current Trends in Consumer Health Monitoring. IEEE

Consumer Electron. Mag 2018 Jan;7(1):38-46. [doi: 10.1109/mce.2017.2743238]

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 11https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

4. Weiner K, Will C. Thinking with care infrastructures: people, devices and the home in home blood pressure monitoring.

Sociol Health Illn 2018 Feb;40(2):270-282. [doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12590] [Medline: 29464773]

5. Mercer K, Giangregorio L, Schneider E, Chilana P, Li M, Grindrod K. Acceptance of Commercially Available Wearable

Activity Trackers Among Adults Aged Over 50 and With Chronic Illness: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation. JMIR Mhealth

Uhealth 2016 Jan 27;4(1):e7 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4225] [Medline: 26818775]

6. Zhu H, Colgan J, Reddy M, Choe E. Sharing Patient-Generated Data in Clinical Practices: An Interview Study. 2016

Presented at: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings; 2016; Chicago, IL p. 1303-1312.

7. Ancker JS, Witteman HO, Hafeez B, Provencher T, Van de Graaf M, Wei E. "You Get Reminded You're a Sick Person":

Personal Data Tracking and Patients With Multiple Chronic Conditions. J Med Internet Res 2015 Aug 19;17(8):e202 [FREE

Full text] [doi: 10.2196/jmir.4209] [Medline: 26290186]

8. Cook DJ, Thompson JE, Prinsen SK, Dearani JA, Deschamps C. Functional recovery in the elderly after major surgery:

assessment of mobility recovery using wireless technology. Ann Thorac Surg 2013 Sep;96(3):1057-1061. [doi:

10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.092] [Medline: 23992697]

9. Perez MV, Mahaffey KW, Hedlin H, Rumsfeld JS, Garcia A, Ferris T, et al. Large-Scale Assessment of a Smartwatch to

Identify Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2019 Nov 14;381(20):1909-1917. [doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901183] [Medline:

31722151]

10. Liu YH, Scifleet P, Given LM. Contexts of Information Seeking in Self-tracking and the Design of Lifelogging Systems.

2014 Presented at: MindTheGap@ iConference; 2014; Berlin, Germany p. 44-50.

11. Nunes F, Verdezoto N, Fitzpatrick G, Kyng M, Grönvall E, Storni C. Self-Care Technologies in HCI. ACM Trans.

Comput.-Hum. Interact 2015 Dec 14;22(6):1-45. [doi: 10.1145/2803173]

12. Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions:

a review. Patient Education and Counseling 2002 Oct;48(2):177-187. [doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00032-0]

13. Schermer M. Telecare and self-management: opportunity to change the paradigm? J Med Ethics 2009 Nov 30;35(11):688-691.

[doi: 10.1136/jme.2009.030973] [Medline: 19880706]

14. Greenwood DA, Young HM, Quinn CC. Telehealth Remote Monitoring Systematic Review: Structured Self-monitoring

of Blood Glucose and Impact on A1C. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2014 Mar 21;8(2):378-389 [FREE Full text] [doi:

10.1177/1932296813519311] [Medline: 24876591]

15. Piras EM, Miele F. Clinical self-tracking and monitoring technologies: negotiations in the ICT-mediated patient–provider

relationship. Health Sociology Review 2016 Aug 05;26(1):38-53. [doi: 10.1080/14461242.2016.1212316]

16. Chau JP, Lee DT, Yu DS, Chow AY, Yu W, Chair S, et al. A feasibility study to investigate the acceptability and potential

effectiveness of a telecare service for older people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Med Inform 2012

Oct;81(10):674-682. [doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.06.003] [Medline: 22789911]

17. Burri H, Senouf D. Remote monitoring and follow-up of pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Europace

2009 Jun 26;11(6):701-709 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1093/europace/eup110] [Medline: 19470595]

18. Eysenbach G. Medicine 2.0: social networking, collaboration, participation, apomediation, and openness. J Med Internet

Res 2008 Aug 25;10(3):e22 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.2196/jmir.1030] [Medline: 18725354]

19. Swan M. Emerging patient-driven health care models: an examination of health social networks, consumer personalized

medicine and quantified self-tracking. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2009 Feb;6(2):492-525 [FREE Full text] [doi:

10.3390/ijerph6020492] [Medline: 19440396]

20. Fiske A, Prainsack B, Buyx A. Data Work: Meaning-Making in the Era of Data-Rich Medicine. J Med Internet Res 2019

Jul 09;21(7):e11672 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.2196/11672] [Medline: 31290397]

21. Piras EM. Beyond self-tracking: Exploring and unpacking four emerging labels of patient data work. Health Informatics J

2019 Sep;25(3):598-607. [doi: 10.1177/1460458219833121] [Medline: 30848690]

22. Ruckenstein M, Schüll ND. The Datafication of Health. Annu. Rev. Anthropol 2017 Oct 23;46(1):261-278. [doi:

10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116-041244]

23. Kaziunas E, Ackerman M, Lindtner S, Lee J. Caring through Data: Attending to the Social and Emotional Experiences of

Health Datafication. 2017 Presented at: CSCW '17: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported

Cooperative Work and Social Computing; Feb 2017; Portland, Oregon p. 2260-2272. [doi: 10.1145/2998181.2998303]

24. Figueiredo MC, Caldeira C, Reynolds TL, Victory S, Zheng K, Chen Y. Self-Tracking for Fertility Care: Collaborative

Support for a Highly Personalized Problem. 2017 Dec 06 Presented at: Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer

Interaction (CSCW); 2017; Portland, Oregon p. 1-21. [doi: 10.1145/3134671]

25. Andersen TO, Andersen PRD, Kornum AC, Larsen TM. Understanding Patient Experience: A Deployment Study in Cardiac

Remote Monitoring. 2017 May Presented at: the 11th EAI International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies

for Healthcare; 2017; Barcelona, Spain p. 221-230. [doi: 10.1145/3154862.3154868]

26. Treacy D, Hassett L, Schurr K, Chagpar S, Paul SS, Sherrington C. Validity of Different Activity Monitors to Count Steps

in an Inpatient Rehabilitation Setting. Phys Ther 2017 May 01;97(5):581-588. [doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzx010] [Medline: 28339904]

27. Benzo R. Activity monitoring in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2009;29(6):341-347

[FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181be7a3c] [Medline: 19940638]

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 12https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

28. Rosenberg D, Kadokura EA, Bouldin ED, Miyawaki CE, Higano CS, Hartzler AL. Acceptability of Fitbit for physical

activity tracking within clinical care among men with prostate cancer. 2016 Presented at: AMIA Annual Symposium

Proceedings; 2016; Chicago, IL p. 1050-1059.

29. Thorup CB, Grønkjær M, Spindler H, Andreasen JJ, Hansen J, Dinesen BI, et al. Pedometer use and self-determined

motivation for walking in a cardiac telerehabilitation program: a qualitative study. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 2016;8:24

[FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1186/s13102-016-0048-7] [Medline: 27547404]

30. Ruckenstein M, Pantzar M. Datafied Life: Techno-Anthropology as a Site for Exploration and Experimentation. Techné:

Research in Philosophy and Technology 2015;19(2):191-210. [doi: 10.5840/techne20159935]

31. Didžiokaitė G, Saukko P, Greiffenhagen C. The mundane experience of everyday calorie trackers: Beyond the metaphor

of Quantified Self. New Media & Society 2017 Mar 24;20(4):1470-1487. [doi: 10.1177/1461444817698478]

32. Sharon T, Zandbergen D. From data fetishism to quantifying selves: Self-tracking practices and the other values of data.

New Media & Society 2016 Mar 09;19(11):1695-1709. [doi: 10.1177/1461444816636090]

33. Kristensen DB, Ruckenstein M. Co-evolving with self-tracking technologies. New Media & Society 2018 Feb

21;20(10):3624-3640. [doi: 10.1177/1461444818755650]

34. Lomborg S, Thylstrup NB, Schwartz J. The temporal flows of self-tracking: Checking in, moving on, staying hooked. New

Media & Society 2018 May 31;20(12):4590-4607. [doi: 10.1177/1461444818778542]

35. Lomborg S, Frandsen K. Self-tracking as communication. Information, Communication & Society 2015 Aug

03;19(7):1015-1027. [doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2015.1067710]

36. Lupton D, Pink S, LaBond C, Sumartojo S. Digital Traces in Context: Personal Data Contexts, Data Sense, and Self-Tracking

Cycling. International Journal of Communication 2018;12:647-665.

37. Schüll ND. Data for life: Wearable technology and the design of self-care. BioSocieties 2016 Oct 13;11(3):317-333. [doi:

10.1057/biosoc.2015.47]

38. Lupton D. Self-Tracking Modes: Reflexive Self-Monitoring and Data Practices. SSRN Journal 2014 Aug:2483549 [FREE

Full text] [doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2483549]

39. Ehn M, Eriksson LC, Åkerberg N, Johansson A. Activity Monitors as Support for Older Persons' Physical Activity in Daily

Life: Qualitative Study of the Users' Experiences. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018 Feb 01;6(2):e34 [FREE Full text] [doi:

10.2196/mhealth.8345] [Medline: 29391342]

40. Puri A, Kim B, Nguyen O, Stolee P, Tung J, Lee J. User Acceptance of Wrist-Worn Activity Trackers Among

Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Mixed Method Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017 Nov 15;5(11):e173 [FREE Full

text] [doi: 10.2196/mhealth.8211] [Medline: 29141837]

41. Lyons EJ, Swartz MC, Lewis ZH, Martinez E, Jennings K. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Wearable Technology Physical

Activity Intervention With Telephone Counseling for Mid-Aged and Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial.

JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017 Mar 06;5(3):e28 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.2196/mhealth.6967] [Medline: 28264796]

42. Hjerteforeningen (Danish Heart Association). ICD (Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator). HjerteTal. 2018. URL: https:/

/hjerteforeningen.dk/alt-om-dit-hjerte/hjertetal/hjertetaldk [accessed 2020-03-20]

43. Timmermans S, Tavory I. Theory Construction in Qualitative Research. Sociological Theory 2012 Sep 10;30(3):167-186.

[doi: 10.1177/0735275112457914]

44. Blaikie N. Abduction. In: Lewis-Beck MS, Bryman A, Liao TF, editors. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research

Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2004.

45. Marent B, Henwood F, Darking M, EmERGE Consortium. Ambivalence in digital health: Co-designing an mHealth platform

for HIV care. Soc Sci Med 2018 Oct;215:133-141. [doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.09.003] [Medline: 30232053]

46. Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE

Publications; 1998:1-169.

47. Lomborg S, Langstrup H, Andersen TO. Interpretation as luxury: Heart patients living with data doubt, hope, and anxiety.

Big Data & Society 2020 May 08;7(1):205395172092443-205395172092413. [doi: 10.1177/2053951720924436]

48. Pedersen SS, von Känel R, Tully PJ, Denollet J. Psychosocial perspectives in cardiovascular disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol

2017 Jun 16;24(3_suppl):108-115. [doi: 10.1177/2047487317703827] [Medline: 28618908]

49. Hoffmann JM, Hellwig S, Brandenburg VM, Spaderna H. Measuring Fear of Physical Activity in Patients with Heart

Failure. Int.J. Behav. Med 2017 Dec 11;25(3):294-303. [doi: 10.1007/s12529-017-9704-x]

50. Lehoux P. The duality of health technology in chronic illness: how designers envision our future. Chronic Illn 2008

Jun;4(2):85-97. [doi: 10.1177/1742395308092475] [Medline: 18583444]

51. Salmela T, Valtonen A, Lupton D. The Affective Circle of Harassment and Enchantment: Reflections on the ŌURA Ring

as an Intimate Research Device. Qualitative Inquiry 2018 Sep 22;25(3):260-270. [doi: 10.1177/1077800418801376]

52. Fotopoulou A, O’Riordan K. Training to self-care: fitness tracking, biopedagogy and the healthy consumer. Health Sociology

Review 2016 Jun 02;26(1):54-68. [doi: 10.1080/14461242.2016.1184582]

53. Pols J. Knowing Patients: Turning Patient Knowledge into Science.. Science, Technology, & Human Values 2013 Sep

13;39(1):73-97. [doi: 10.1177/0162243913504306]

54. Hartzler A, Pratt W. Managing the personal side of health: how patient expertise differs from the expertise of clinicians. J

Med Internet Res 2011 Aug;13(3):e62 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.2196/jmir.1728] [Medline: 21846635]

J Med Internet Res 2020 | vol. 22 | iss. 7 | e15873 | p. 13https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e15873

(page number not for citation purposes)

Andersen et alJOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH

XSL

•

FO

RenderX

55. Storni C. Patients' lay expertise in chronic self-care: a case study in type 1 diabetes. Health Expect 2013 Aug

28;18(5):1439-1450. [doi: 10.1111/hex.12124]

56. Johnson DJ. Health-related information seeking: Is it worth it? Information Processing & Management 2014

Sep;50(5):708-717 [FREE Full text] [doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2014.06.001]

57. Pols J. Care at a Distance. On the Closeness of Technology. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press; 2012:1-163.

58. Mol A. The logic of care: Health and the problem of patient choice. London and New York: Routledge; 2008:1-95.