This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau

of Economic Research

Volume Title: Reducing Inflation: Motivation and Strategy

Volume Author/Editor: Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer, Editors

Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press

Volume ISBN: 0-226-72484-0

Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/rome97-1

Conference Date: January 11-13, 1996

Publication Date: January 1997

Chapter Title: How the Bundesbank Conducts Monetary Policy

Chapter Author: Richard H. Clarida, Mark Gertler

Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8890

Chapter pages in book: (p. 363 - 412)

10

How

the Bundesbank Conducts

Monetary Policy

Richard Clarida and Mark Gertler

10.1

Introduction

Over the last decade there has been a growing belief among economists and

policymakers that the primary objective of monetary policy should be to con-

trol inflation. Two kinds of arguments are cited. First, experience suggests that

fine-tuning the economy is not a realistic option and that inflation is difficult

to lower. By taking preemptive steps to avoid high inflation, a central bank can

reduce the likelihood of having to engineer a costly disinflation. Second, a

central bank that establishes a clear commitment to controlling inflation may

be able to maintain low inflation for far less cost than if it did not have this rep-

utation.

In this context German monetary policy is of great interest. From the

breakup of Bretton Woods in

1973

until the year prior

to

reunification,

1989,

average annual inflation in West Germany was lower than in any other Organi-

zation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) country. Based

in large part on this historical performance, the Deutsche Bundesbank

is

known for its commitment to fighting inflation, perhaps more than any other

central bank. The institutions of German monetary policy, further, appear spe-

cifically geared toward controlling inflation. Each year since 1974 the Bundes-

bank has set targets for both inflation and monetary growth.

Richard Clarida is professor of economics at Columbia University and a research associate of

the National Bureau of Economic Research. Mark Gertler is professor of economics at New York

University and a research associate of

the

National Bureau of Economic Research.

Thanks for helpful comments to Rudi Dombusch, Willy Friedman, Jeff Fuhrer, Jordi Gali, Dale

Henderson, Otmar Issing, Christy Romer, Dave Romer, Chris Sims, Mike Woodford, and seminar

participants at the Federal Reserve Board, Boston University, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston,

Yale University, the University of Miami, the Bundesbank, the Massachusetts Institute of Technol-

ogy, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. Special thanks to Eunkyung Kwon for tireless

research assistance. Thanks also to Rosanna Maddalena. Gertler acknowledges support from the

National Science Foundation and the C.

V.

Stan Center.

363

364

Richard Clarida and

Mark

Gertler

This paper provides

a

broad-based description of German monetary policy.

The goal is to learn about the mechanics of maintaining low inflation, and

about the net benefits and costs of doing

so.

In the end we provide

a

description

of how the Bundesbank conducts monetary policy that is based on both

a

read-

ing of the historical evidence and a formal statistical analysis of the Bundes-

bank’s policy rule.

What makes the general problem of evaluating Bundesbank policy challeng-

ing is that for much of the last fifteen years the performance of the real econ-

omy has been mixed. Unraveling the precise role of monetary policy in this

performance is

a

complex issue, one that our analysis cannot fully resolve. By

closely studying the record of monetary policy, however, we try to shed light

on the matter.

Section 10.2 describes the institutions of German monetary policy. Here we

outline the system of inflation and monetary targeting.

As

is commonly under-

stood by close observers of the Bundesbank, the targets are meant

as

guide-

lines. In no sense do they define

a

strict policy rule. In terms of operating

procedures, the Bundesbank chooses a path for short-term interest rates to

meet its policy objectives, similar in spirit to the Federal Reserve Board.

Section

10.3

reviews the history of Bundesbank policy since the breakup of

Bretton Woods. Here our objective is to obtain narrative evidence on how the

Bundesbank operates in practice.

As

one might expect, we find that the Bunde-

sbank is aggressive in managing short-term interest rates to dampen inflation-

ary

pressures, the exception being the period between the two major oil shocks,

1975 to early 1979. On the other hand, it clearly factors in the performance of

the real economy in setting rates, though perhaps not explicitly. For example,

it often cites exchange rate considerations to pursue what closely resembles

a

countercyclical policy. We

also

find,

as

have others, that curtailing inflation is

not

a

costless process for the Bundesbank, despite its reputation.

Sections 10.4 and 10.5 supplement the narrative evidence with

a

formal sta-

tistical analysis of Bundesbank policy. Specifically, we attempt to identify

a

policy reaction function that characterizes how the Bundesbank sets the short-

term interest rate. In general, estimating

a

policy reaction function involves

a

number

of

formidable identification issues,

as

we discuss. We take

a

two-step

approach. We first obtain

a

reaction function by estimating

a

structural vector

autoregression

(VAR).

This approach permits us to formally characterize how

the Bundesbank adjusts short-term rates in response to different disturbances

to the economy, using only

a

minimal set of identifying assumptions.

As

we

show, the results are highly consistent with the narrative evidence. The disad-

vantage of this approach is that the reaction function is difficult to summarize

intuitively because it is based on the entire information set in the

VAR.

Section 10.5 presents the second step. We place additional structure on the

model to obtain

a

more conventional-looking reaction function based on infla-

tion and output objectives. We estimate a reaction function for the German

365

How

the Bundesbank Conducts Monetary

Policy

short-term rate that is close in general form to the one developed by Taylor

(1993) to characterize how the Federal Reserve Board has set the funds rate

during the Greenspan era. In particular the central bank adjusts the short-term

interest rate in response to the gaps between inflation and output and their

respective targets. One key difference from Taylor is that under our rule the

central bank is forward-looking in the sense that it responds to expected future

inflation as opposed to lagged inflation. To form these expectations, our rule

uses the information about the economy that is contained in the VAR model.

Another key difference is that we allow for an asymmetric policy response to

inflation; that is, we allow for the possibility that the Bundesbank may tighten

more aggressively when expected inflation is above target than it eases when

expected inflation

is

below target.

Overall, the estimated reaction function does a reasonably good job of char-

acterizing the path of the German short-term rate over the post-Bretton Woods

era. In addition the Bundesbank does appear to respond asymmetrically to the

inflation gap. Finally, as we show, our modified “Taylor” rule provides a useful

benchmark to gauge the position of policy at different critical junctures of the

economy. Taken all together, our results suggest that Bundesbank policy since

1973 may be characterized as being reasonably similar to Federal Reserve pol-

icy under Alan Greenspan.

Section

10.6

offers concluding remarks.

10.2

Institutions

of

Bundesbank Policy

As is commonly presumed, the overriding objective of German monetary

policy

is

to control inflation. The institutional design supports this goal in two

main ways. First, formal legislation explicitly restricts political influence. Sec-

ond, each year the Bundesbank clearly articulates an inflation objective and

then establishes a target for the growth of a key monetary aggregate, based on

this objective.

At the same time it is important to recognize that the system allows for

flexibility, The monetary and inflation targets, for example, are only guidelines

and not legal mandates. Events in the real economy can (and often do, as we

will see) induce the Bundesbank to deviate from these guidelines, though not

without some kind of official explanation.

With these general observations in mind, we proceed to characterize the

institutional design

of

Bundesbank policy. Section 10.2.1 describes the organi-

zation and jurisdiction of the German central bank. Section 10.2.2 discusses

the practice of monetary and inflation targeting. Section 10.2.3 describes the

operating procedures for conducting monetary policy. Here we argue that, de-

spite the focus on monetary aggregates, short-term interest rates provide a bet-

ter overall indication

of

the thrust

of

policy than do the aggregates. In this

respect there are some strong similarities with

U.S.

monetary policy.

366

Richard Clarida and Mark

Gertler

10.2.1

Much as the experience of the Great Depression shaped the development

of monetary and financial institutions in the United States, memories of the

hyperinflation influenced the design of the German central bank. Article

3

of

the Deutsche Bundesbank Act of 1957 empowers the German central bank

to regulate the amount of currency and credit in circulation with the aim of

safeguarding the currency. To ensure that this goal is feasible, legal mandates

free monetary policy from the demands of fiscal policy. To avoid the mistakes

of the hyperinflation, article 20 of the act prohibits the central bank from fi-

nancing government deficits. Decisions on the course of monetary policy are

made by a council that is independent of the federal government. Article

12

of

the act makes this independence explicit.'

The formal body that sets monetary policy is the Central Bank Council,

which closely resembles the federal Open Market Committee. It consists of

the Bundesbank Board (analogous to the Federal Reserve Board) and the presi-

dents of the German

Land

central banks (analogous to the presidents of the

regional reserve banks). The Bundesbank Board consists of a president, vice

president, and up to six other board members. The federal government nomi-

nates the board members, while the state governments nominate the presidents

of the

Land

central banks. Terms are for eight years. Except for the constraint

of mandatory retirement, council members typically are invited to serve a sec-

ond term. The long terms are justified as a means to insulate the governing

body from political pressures.

From the perspective of political independence, any differences between the

institutional setup of the Bundesbank and the Federal Reserve are not dramatic.

Grilli, Masciandaro, and Tabellini (1991) assign the German central bank a

slightly higher independence rating than its

U.S.

counterpart because the

Bundesbank president is guaranteed a longer term than is the Federal Reserve

Board chair (eight years versus four years.)

Finally, the Bundesbank's jurisdiction is not completely independent of the

federal government. The latter has discretion over exchange rate agreements.

At least in practice, however, the government cannot force the Bundesbank to

maintain agreements that threaten domestic price stability. Before Germany

entered the European Monetary System (EMS), for example, the Bundesbank

won a provision from the federal government that it could deviate from the

exchange agreement if it was deemed necessary to do

so

in order to maintain

low inflation (Neumann and Von Hagen 1993). In effect this meant that the

Bundesbank assumed a clear leadership role in the EMS. At least for a period

Central Bank Design and Jurisdiction

1.

Article

12

encourages the Bundesbank to cooperate with the economic objectives of the

federal government, but not to the extent that doing

so

may conflict with the overriding goal of

price stability. The article explicitly forbids the federal government to formally participate in mon-

etary policy decisions.

367

How

the Bundesbank Conducts Monetary Policy

of time, this was a suitable arrangement for the other countries involved. Be-

cause

of

its reputation the Bundesbank served as an informal nominal anchor.

On numerous occasions other central banks simply followed the response of

German interest rates to exogenous shocks.2

10.2.2

Monetary and Inflation Targeting

The Bundesbank is widely known for its practice of setting monetary tar-

gets. Perhaps its most distinctive feature, though,

is

its simultaneous practice

of

setting inflation targets. Inflation targeting is slowly increasing in popularity

among central banks, and is currently a popular subject

of

academic discus-

sion. It is perhaps not widely appreciated, however, that always underlying

Germany’s announced monetary target is an explicitly stated goal for inflati~n.~

This contrasts with the United States, for example, where in the past monetary

targets have been set without any explicit public rationalization.

Also not widely appreciated is the flexibility built into the policy rule. There

is no blind commitment to hitting the monetary

target^.^

The view is that the

monetary policy will be judged on its inflation scorecard, and it will not be

penalized for missing monetary targets if inflation is under control. In addition

there has not been a unilateral focus on inflation.

As

we show later, on a num-

ber of occasions, the Bundesbank has tolerated deviations from the targets in

order to pursue what may be construed as a countercyclical p01icy.~

The Targeting Procedure

The practice of targeting began in

1975,

after the breakup of Bretton Woods.

The Bundesbank felt the need to maintain some kind of explicit nominal an-

chor to guide policy in the post-Bretton Woods era. The procedure works as

follows: Each year the Bundesbank first establishes a goal for inflation.

A

tar-

get growth rate for a designated monetary aggregate is then established that is

meant to be consistent with the inflation goal. In particular the money-growth

2.

Uctum (1995). among others, provides some formal evidence

for

the

Bundesbank‘s leadership

role in the EMS. The paper identifies a clear causal relationship between German short-term inter-

est rates and the short-term interest rates of other countries.

3.

Bundesbank officials are resistant to equating their selection

of

an inflation goal with inflation

targeting. They maintain that the ultimate target is price stability. Any deviation

of

the inflation

goal from price stability is due to what they term “unavoidable” factors.

4.

The notion that the targets serve as guidelines rather than as rigid mandates is a prominent

theme in many studies

of

Bundesbank behavior.

See,

for

example, Bemanke and Mishkin (1992);

Kahn and Jacobson (1989); Trehan (1988);

Von

Hagen (1994).

In

addition, Bundesbank officials

themselves are rather open about the flexibility inherent in the system.

For

example, to quote,

Otmar Issing (1995,5), the current head of the Bundesbank’s research department, “Even in Ger-

many, where

a

high degree of stability of financial relationships was observed,

the

central bank

has never seen fit to transfer monetary targeting to an ‘autopilot,’ as it were.’’

5.

Even in its official publications, the Bundesbank makes clear that circumstances may justify

deviating from the targets. It states that, while the monetary targets “include a recognizable steady-

ing element, they

are

not meant to preclude any reaction to the developments of economic activity,

exchange rates, costs, and prices” (Deutsche Bundesbank 1989,99).

368

Richard Clarida and Mark

Gertler

target is backed out of a conventional quantity-theory equation that links

money, velocity, prices, and output. As inputs into the equation, the Bundes-

bank uses the target rate of inflation and estimates of the trend growth

of

veloc-

ity and the trend growth

of

capacity output. The motive for using estimates of

trend as opposed to near-term output and velocity growth in the calculation is

to avoid trying to fine-tune inflation.6 Instead, the objective is to maintain a low

long-run average inflation rate. By clearly signaling its intent to gear policy

toward achieving this long-term inflation goal, the Bundesbank seeks to influ-

ence private-sector wage and price adjustments.’

Originally, a fixed money target was announced. After two years, however,

this was changed to a fixed range. The move to the range reflects the reality

that the monetary aggregate is difficult to tightly regulate and that both output

and velocity may deviate considerably from trend in the short run. Additional

flexibility is provided by a midyear review

of

targets, which allows changing

the targets in light of new information. The Bundesbank has made use of this

option only once, however, during 1991, in the early stages

of

reunification.

Finally, the targets are fixed for a fourth-quarter-to-fourth-quarter growth rate

of

a

variable. Originally, they were from December to December, but the

monthly pinpointing introduced too much transitory noise.

How does the Bundesbank set its inflation target? The official goal is to

keep inflation from rising above its “unavoidable” level. Using this criteria, the

Bundesbank has set a goal

of

2%

annual inflation for each year since 1986 (see

table 10.1). The Bundesbank refrains from reducing the target to 0% because

the official price index may overstate the true inflation rate since it tends to

undercompensate for improvements in the quality

of

goods. Fixing the target

at

2%

ensures that measurement error in the price index will not inadvertently

induce the Bundesbank to tighten (Issing 1995).

In the past the Bundesbank has also taken into account stabilization consid-

erations in fixing the target inflation rate, at least implicitly. In the initial year

of targeting, 1975, it set the inflation goal at 4.5%. This objective was picked

with the aim of gradually reducing inflation over time. At the time, Germany

(like the United States) was experiencing stagflation, due to the oil shocks of

1973 and 1974. The target was reduced to

2%

gradually over time. The fact

6. Indeed, Bundesbank officials state explicitly that the central bank

does

not try to fine-tune

either inflation

or

money growth in the short term. To quote Issing (1995,

8)

again: “in the short

term the relationship between the money stock and the overall domestic price level is obscured by

a

host of influencing factors. Any attempt at keeping the money stock

on

the desired growth path

at all times would therefore inevitably spark

off

considerable interest rate and exchange rate fluc-

tuations, provoke shocks to the trend of economic activity and hence cause unnecessary economic

costs in the shape

of

adjustment on the part

of

economic agents. Accordingly, the Bundesbank has

time and again pointed to the medium term nature

of

its strategy which is aimed at cyclical stabili-

zation.”

7.

In

particular the Bundesbank states that an important purpose of the targeting procedure is to

“make the aims

of

monetary policy clearer to labor and management, whose cooperation is

essen-

tial

if

inflation

is

to be brought under control without detrimental effects to employment”

(Deutsche Bundesbank 1989, 97).

369

How the Bundesbank Conducts Monetary Policy

Table

10.1

History

of

Money-Growth Targets and Unavoidable Inflation

Money Growth Inflation

Year Target Actual Target Actual

1975

1976

1977

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

8

8

8

8

6-9

5-8

4-7

4-7

4-7

4-6

3-5

3.5-5.5

3-6

3-6

5

4-6

4-6

3.5-5.5

4.5-6.5

10

9

9

11

6

5

4

7

7

5

4.5

8

8

6.7

4.6

5.6

5.2

9.4

7.4

4.5

4.5

3.5

3

.O

3.0

4.0

3.8

3.5

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.5

2.0

2.0

2.0

2.0

2.0

2.0

2.0

-

5.6

3.7

3.3

2.6

5.4

5.3

6.7

4.5

2.6

2.0

1.6

-1.0

1

.o

1.9

3

.O

2.7

4.2

3.7

3.7

Sources:

Kole

and Meade

1994;

Von Hagen

1994

Notes:

From

1975

to

1984

the Bundesbank announced a rate

of

“unavoidable” inflation as its input

to the determination

of

money-growth targets. From

1985

to

1993

the objective was the rate of

inflation consistent with “price stability.”

that the target was not set lower initially suggests that, while controlling infla-

tion may be its primary goal, the Bundesbank is not willing to do it at any cost.*

As

further evidence of the Bundesbank’s pragmatism, the previous year’s

performance of inflation relative to its target does not directly affect the current

target choice. The targets are simply rebenchmarked, implying that the Bunde-

sbank accommodates any overshooting in the previous year. It thus does not

try to target a path for the price level. We return to this point in section

10.3,

during the historical review of monetary policy.

Choice

of

a Monetary Aggregate

What determines the monetary aggregate that the Bundesbank targets? The

desired aggregate must satisfy two conventional criteria. First, it should be

reasonably controllable. Second, it should obey a relatively predictable rela-

tionship with nominal

GDP. These criteria quickly eliminate narrow money

8.

The Bundesbank officially acknowledges that the need for a gradualist approach to reducing

inflation influenced its targeting decisions. It states that in setting the targets “it took account

of

the fact that price increases which have already entered the decisions

of

economic agents cannot

be

eliminated immediately, but only by degrees” (Deutsche Bundesbank

1989,97).

370

Richard Clarida and Mark

Gertler

aggregates like M1. Substitution between demand deposits and near-money

substitutes (e.g., time and savings deposits) make this aggregate difficult to

regulate. It also induces large fluctuations in M1 that are unrelated to the

course of economic activity.

The Bundesbank originally settled on a construct it termed central bank

money (CBM). The idea underlying the construct was to develop an aggregate

that was a weighted average of all existing monetary instruments, where the

weights reflect the relative “moneyness” of each instrument. The elements of

CBM are, roughly speaking, the sum

of

currency held outside the banking

system and the components

of

the broad aggregate M3 (which corresponds to

M2 for the United States) weighted by the respective reserve requirement that

existed in 1974. Thus, CBM is roughly the monetary base minus excess re-

serves. It differs by not including reserves against foreign deposits and by us-

ing the 1974 reserve requirements as opposed to the current ones. The rationale

for using reserve requirements to weight the aggregates was that reserve re-

quirements reasonably reflected the relative liquidity of each bank deposit lia-

bility.

In 1988 the Bundesbank switched to targeting the broader money aggregate

M3. Strong currency growth in 1987 (due possibly to low interest rates) led to

a rapid expansion of CBM. The Bundesbank felt that the broader aggregate

was less susceptible than CBM to gyrations stemming from currency substitu-

tion (Trehan 1988). The decision to change the target aggregate is one

of

a

number of pieces of evidence that the Bundesbank does not conduct policy on

automatic pilot. New market developments can influence policy.

A

number

of

studies have demonstrated that the relation between M3 and

nominal GDP has been fairly stable over time (e.g., Trehan 1988). Some papers

have argued that the early stages of reunification have not disrupted this rela-

tionship (e.g., Von Hagen 1994; Kole and Meade 1994). Very recently, how-

ever, there has been considerable financial innovation, patterned after what has

occurred in the United States over the last five to ten years.9 There is some

possibility that this development may introduce the same kind of instability in

M3 that the United States has experienced with its M2 aggregate.

If

this does

occur, we should not be surprised

to

see a new target aggregate emerge.

10.2.3 Operating Procedures

Despite the public focus on monetary aggregates, the daily management

of

policy is concerned with the setting of short-term market interest rates. Like

many other central banks, the Bundesbank translates its main policy goals

(e.g., controlling inflation) into near-term interest rate objectives. It in turn

supplies bank reserves to meet these objectives. Even in its official publica-

tions, the Bundesbank states (in its own oblique way) that, in the short run,

9.

For

a

description

of

how

recent financial innovation

is

affecting the monetary aggregates in

Germany, see

German

Economic

Cornmenrur?:

(Goldman Sachs), no.

42

(1994).

371

How

the Bundesbank Conducts Monetary Policy

moderating market interest rate fluctuations takes precedence over meeting

monetary targets.1° In section 10.4 we present formal evidence that supports

this contention.

Until the mid- 1980s the Bundesbank manipulated short-term market interest

rates (and bank reserves) via discount window lending to commercial banks.

It made available two types of credit: discount and Lombard. Banks could re-

ceive discount credit at a preferred rate, up to a fixed quota.

To

meet short-

term liquidity needs beyond the quota limit, they could obtain Lombard credit

at a premium rate. Under normal circumstances Lombard credit was generally

available in elastic supply. In periods of tightening, though, limits could also

be placed on the use of this credit.

Both the discount and Lombard rates

are

posted rates. The market rate that

discount window lending most directly affects is the rate in the interbank mar-

ket for reserves, known as the day-to-day rate or the call money rate.

As

in the

United States, reserve management policy is geared toward influencing the

interbank rate.” Short-term variation in this rate therefore reflects the intention

of monetary policy.

As

figure 10.1 indicates, the day-to-day rate tends to fluc-

tuate in the band fixed by the discount and Lombard rates.

Since 1985 the Bundesbank has supplied banks with reserves mainly via

repurchase agreements, which

are

essentially collateralized loans with a matu-

rity of two to four weeks. Lombard credit has largely dried up. Nonetheless,

the Bundesbank still posts a Lombard rate, mainly as a way to signal its inten-

tions. Reserve management continues to directly influence the day-to-day rate,

which still tends to fluctuate between the discount and Lombard rates,

as

figure

10.1

illustrates. Further, the day-to-day rate also tends to move closely with the

rate on repurchase agreements, known as the rep0 rate. Despite the midstream

change in operating procedures, therefore, it is still reasonable to view the day-

to-day rate as the Bundesbank’s policy instrument

for

the full post-Bretton

Woods era.

10.3

A

Narrative Description

of

Bundesbank Policy

In this section we provide a selective review of Bundesbank policy during

the post-Bretton Woods era.12 Our goal is to obtain narrative evidence on how

the Bundesbank operates in practice.

It is useful to divide the review into four episodes:

(1)

1973-78, the period

10.

For

example, the Bundesbank states that, because commercial banks’ demand for reserves

is “virtually inelastic” in the short run, it “has no choice but to meet the credit institutions’ need

for

central bank balances in the short

run.

At times

it

may

even

have to provide more central bank

balances than

are strictly compatible with the growth in the money stock” (Deutsche Bundesbank

1989,

105).

I

1. Bernanke and Blinder (1992) propose treating the funds rate

as

the operating instrument

for

U.S.

monetary policy, Bernanke and Mihov (1995) present evidence

in

support of this approach.

12. For

additional information on the history

of

postwar Bundesbank policy,

see

Tsatsaronis

(1993).

372

Richard Clarida and Mark Gertler

16.00

14.00

12.00

1.0.00

8.00

6.00

4.00

2.00

0.00

'

73 76 79

82 85 88 91

94

Fig.

10.1

German short-term interest rates

immediately after Bretton Woods was abandoned and after the first major oil

shock occurred; (2) 1979-83, when the second major oil shock occurred and

the United States tightened monetary policy; (3) 1983-89, the era of stagnation

and late recovery in West Germany; (4) 1990-93, the early years of reunifica-

tion. After a brief discussion

of

each episode, we summarize the key lessons

about the conduct

of

Bundesbank policy.

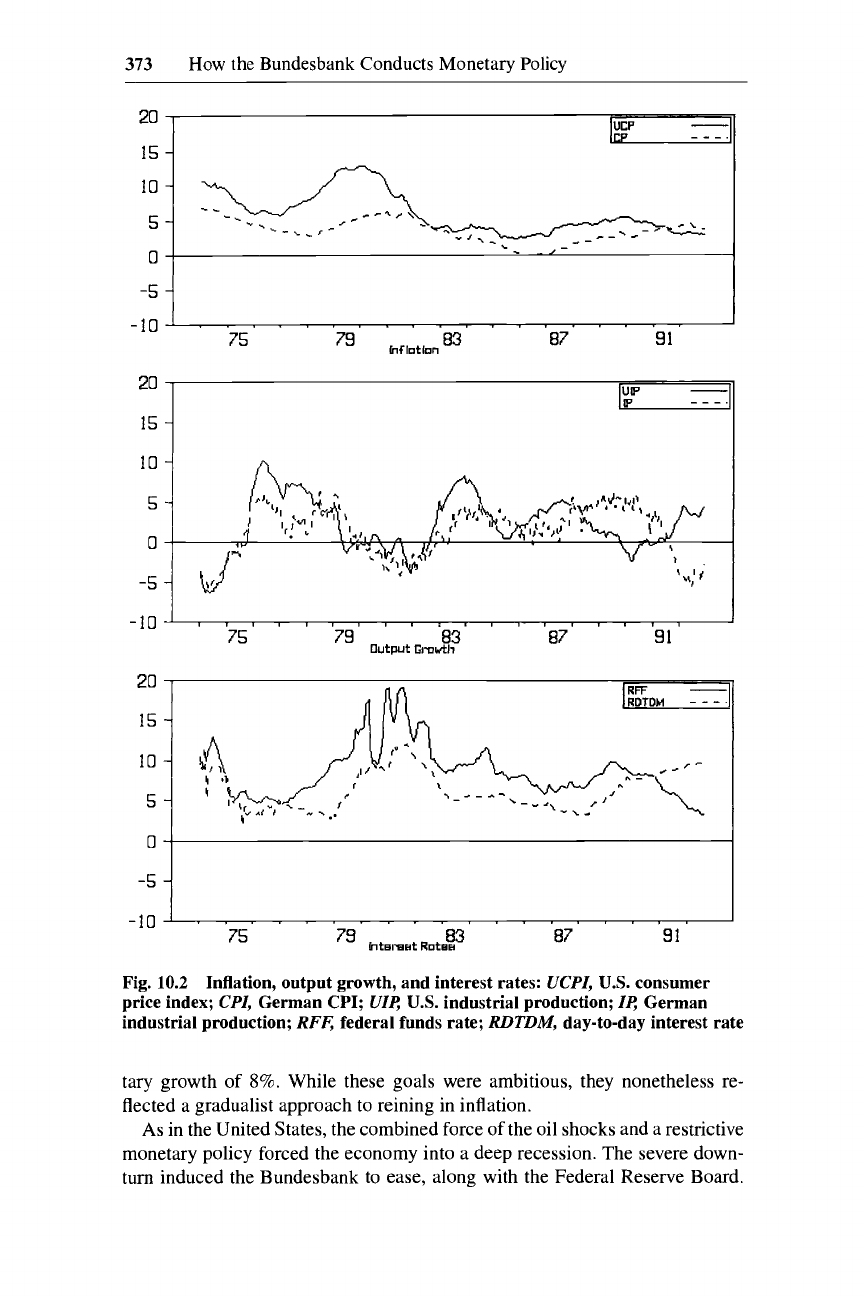

To aid the discussion, we refer (often implicitly) to figure 10.2, which plots

consumer price index

(CPI)

inflation, the growth rate

of

industrial production,

and the day-to-day rate, all for West Germany. To provide a benchmark, the

figure also plots the analogous variables for the U.S. economy. In addition

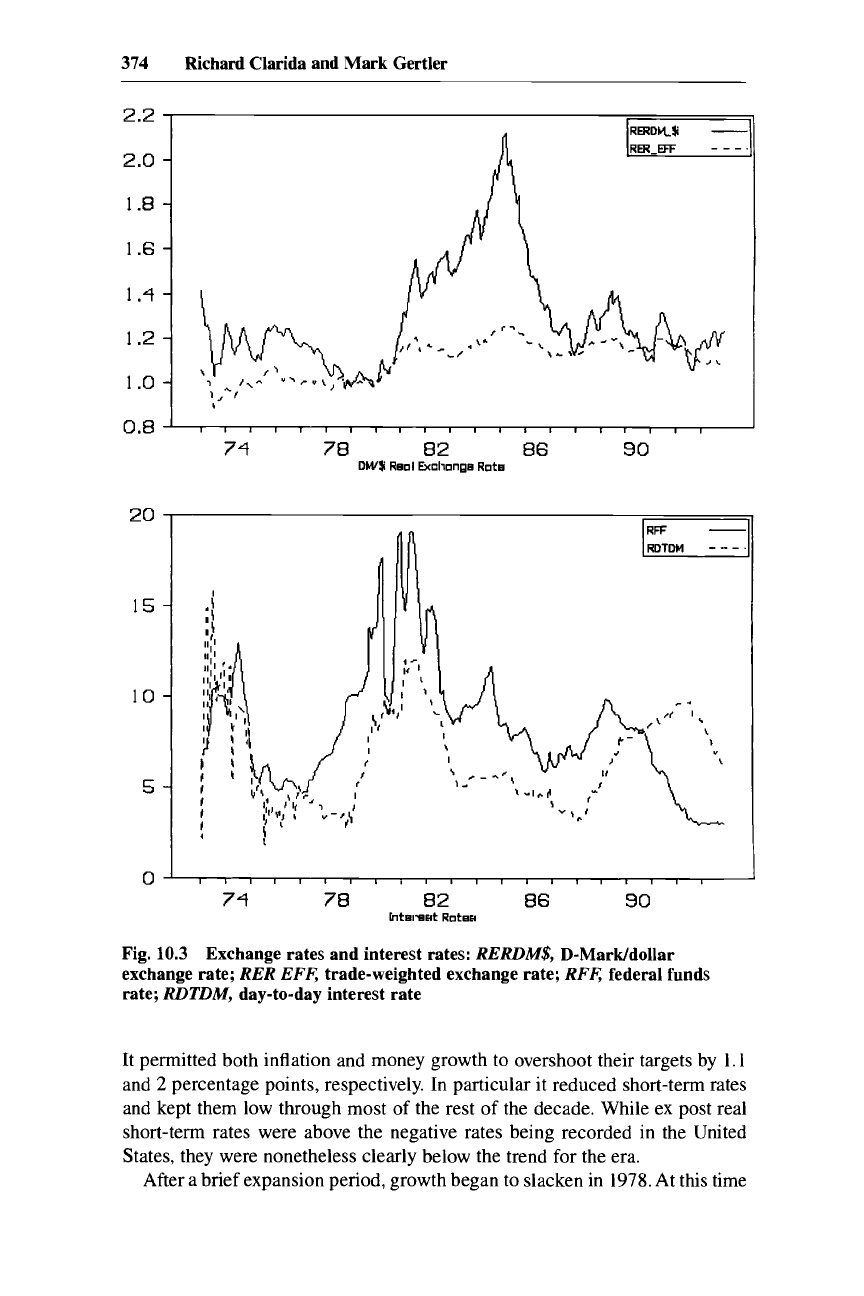

figure 10.3 plots the behavior

of

both the real D-marMdollar exchange rate,

and the trade weighted exchange rate.

10.3.1 1973-1978

Shortly after it was freed from its obligations under Bretton Woods in early

1973, the Bundesbank raised short-term interest rates dramatically in order to

curtail steadily rising inflation. On a number

of

occasions during this period

it

publicly announced a commitment to maintaining

d

tight monetary policy until

inflation was under control (Tsatsaronis 1993). Unfortunately, later in the year

came the first major oil shock. Thus, despite a restrictive policy through most

of 1973, inflation climbed above 7% by the end

of

1974. Though below the

nearly double-digit level reached

in

the United States, this rate was clearly high

by West German standards.

The Bundesbank continued to signal its intent to combat inflation. By the

end of 1974, it had the system

of

inflation and monetary targeting intact. It

announced a target rate of inflation for 1975 of 4.5% and a target rate of mone-

373

How

the Bundesbank Conducts Monetary Policy

15

-

-

UP

P

I

15

-I

RFF

-

RDTDM

-

-

-'

20

-5

1

87

91

-10'

'.

' ' '

*

'

''

'

'

'

'.

. . . .

'

83

79

ht6lmst Rot6H

75

Fig.

10.2

Inflation, output growth, and interest rates: UCPZ,

U.S.

consumer

price index; CPZ, German

CPI;

UZe

U.S.

industrial production;

Ze

German

industrial production;

RFe

federal funds rate;

RDTDM,

day-to-day interest rate

tary growth

of

8%.

While these goals were ambitious, they nonetheless re-

flected a gradualist approach to reining in inflation.

As

in the United States, the combined force of the oil shocks and

a

restrictive

monetary policy forced the economy into a deep recession. The severe down-

turn induced the Bundesbank to ease, along with the Federal Reserve Board.

374

Richard Clarida and Mark Gertler

2.2

2

.o

1.8

1.6

1.4

1.2

1

.o

20

15

10

5

Fig.

10.3

Exchange rates and interest rates:

RERDM$,

D-MarWdollar

exchange rate;

RER EFF,

trade-weighted exchange rate;

RFF,

federal funds

rate;

RDTDM,

day-to-day interest rate

It permitted both inflation and money growth to overshoot their targets by

1.1

and

2

percentage points, respectively. In particular it reduced short-term rates

and kept them low through most of the rest of the decade. While ex post real

short-term rates were above the negative rates being recorded in the United

States, they were nonetheless clearly below the trend for the era.

After a brief expansion period, growth began to slacken in

1978.

At

this time

375

How

the Bundesbank Conducts Monetary Policy

the Bundesbank cited an appreciating mark to justify continued easing. In ef-

fect the Bundesbank was easing rates to stimulate a softening real economy.

While it is not always so forthcoming, it has acknowledged that concern for

the real economy influenced its behavior during this period.13

10.3.2 1979-1 983

Just prior to 1979, macroeconomic conditions in West Germany were more

favorable than in the United States. Output growth was roughly similar. While

the inflation rate was still stubbornly high by West German standards, it was

well below the U.S. inflation rate. Fortunes were reversed, however, in the eight

years after.

The first oil shock and the subsequent shift in U.S. monetary policy ushered

in a return to tight money. The Bundesbank was committed to avoiding (what

it viewed as) its earlier mistake of largely accommodating the increases in oil

prices during 1973 and 1974 (Tsatsaronis 1993). In addition the sharp rise in

U.S. interest rates precipitated a sharp and steady depreciation of the mark

relative to the dollar that lasted until 1985.

The Bundesbank responded to these events by raising the day-to-day rate

from about 3% in 1979 to about 12% in the first quarter of 1981. In terms of

basis points, this increase was similar in magnitude to the rise in the U.S. funds

over same period. Ex post real rates rose sharply, as they did in the United

States.

Again, its pragmatic side showed through: the Bundesbank raised the target

rate of inflation from 3% in 1979 to 4% in 1980. And it still permitted inflation

to overshoot its target by 1.3%. The weakening of the real economy at the time

was again apparently a factor in the Bundesbank’s decision making. For the

next two years it continued the gradualist policy, tolerating above-target infla-

tion in order to avoid further weakening a recessionary economy.

From the period of peak inflation to the beginning of 1983, the contraction

in real activity in West Germany was of similar magnitude to that in the United

States. On the other hand, the drop in inflation over the same time interval was

far more dramatic in the United States. At the start of the period the U.S. infla-

tion rate was nearly double that in West Germany. By the end it was roughly

equal. These facts correspond closely to Ball’s observation (1994) that the sac-

rifice ratio in Germany actually exceeds its counterpart for the United States.

Many have found this outcome surprising. Underlying this view is the belief

that the Bundesbank’s reputation for fighting inflation should have made the

transition to lower inflation less painful in this country relative to other coun-

tries at the time. This in turn raises the possibility that the practical gains from

establishing credibility in fighting inflation may not be substantial. Fully re-

13.

The Bundesbank states that when the D-mark appreciated “excessively” in

1978

(and also

in 1986-87),

it

felt “forced to pursue a more expansionary monetary policy and allow interest rate

reductions

. .

.

which led to an overshooting

of

the monetary target. Otherwise the appreciation

shock would have too much for the economy, while inflationary pressures were being moderated

by the appreciation” (Deutsche Bundesbank 1989,

103).

376

Richard Clarida and

Mark

Gertler

solving this issue is well beyond the scope of this paper, though we return

to

the matter later.

For now we simply note two considerations. First, the sacrifice ratio could

be highly nonlinear in practice, something for which the Ball calculation does

not allow. One could imagine why trying to move an economy from

6%

to 2%

inflation might result in greater short-run output loss than, say, trying to move

it from 10% to

6%.

This nonlinear relationship could resolve at least some of

the differences in the

U.S.

and West German experience.

Second, and somewhat related, at the beginning of 1979 the public percep-

tion of the Bundesbank’s commitment to reduce inflation below

56%

may

have been more ambiguous than it is today.

As

we have discussed, the Bundes-

bank pursued

a

relatively lax monetary policy in the roughly four years prior

to the shift to tightening. Again, we turn to this issue later.

10.3.3 1983-1989

While the U.S. economy staged a strong recovery following the 1981-82

recession, the same was not true of the West German economy. Growth was

slightly below trend in 1983 and only slightly above trend in 1984 and 1985.

The unemployment rate continued to rise steadily, reaching 9.3% in 1985. On

the other hand, a product of the weak economy was receding inflation. Inflation

was below target from 1983 to 1985. During this period the Bundesbank re-

turned short-term nominal rates to slightly above pre-1979 levels. Lower infla-

tion, however, implied significantly higher real interest rates than during the

late 1970s.

As

we show in section 10.5, real rates during this period hovered

slightly around and above long-run equilibrium.

Why the West German economy (along with the rest of the European econ-

omy) performed poorly over this period is

a

complex issue, another that is well

beyond the paper’s scope. It is plausible that high real interest rates were a

factor. Real rates were similarly high in the United States at this time. The

United States, however, had shifted to an expansionary fiscal policy. The same

kind

of

fiscal stimulus was not present in West Germany.

Another often-cited possibility is that the German economy was experienc-

ing structural labor market problems at this time (e.g., Kahn and Jacobson

1989). This would imply that the stagnant economy was due mainly to supply-

side problems, that

is,

declines in capacity output. It is true that real wages

grew rapidly from 1973 through 1989. The period 1982-85, though, does not

appear to have been a period of rapid wage growth. While we do not claim

to

resolve the issue, later we examine more carefully the behavior of output rela-

tive to capacity and real interest rates over this period.

In

mid-1984 the United States began a systematic reduction of the funds rate

in an effort, among other things, to reduce the value of the dollar. In early 1985

the mark began a steady appreciation against the dollar that lasted through early

1988. In response to the appreciating mark, the real economy weakened. Out-

put growth declined over 1986 and 1987. Inflation fell below the

2%

target.

The weak economy prompted the Bundesbank to once again demonstrate

377

How

the Bundesbank Conducts Monetary Policy

its flexibility in both actions and language. Citing an appreciating mark, the

Bundesbank eased short-term interest rates. Real short-term rates fell, though

not to the levels of the mid- to late 1970s. Following the easing, output growth

picked up

in

1989. A strong recovery finally materialized.

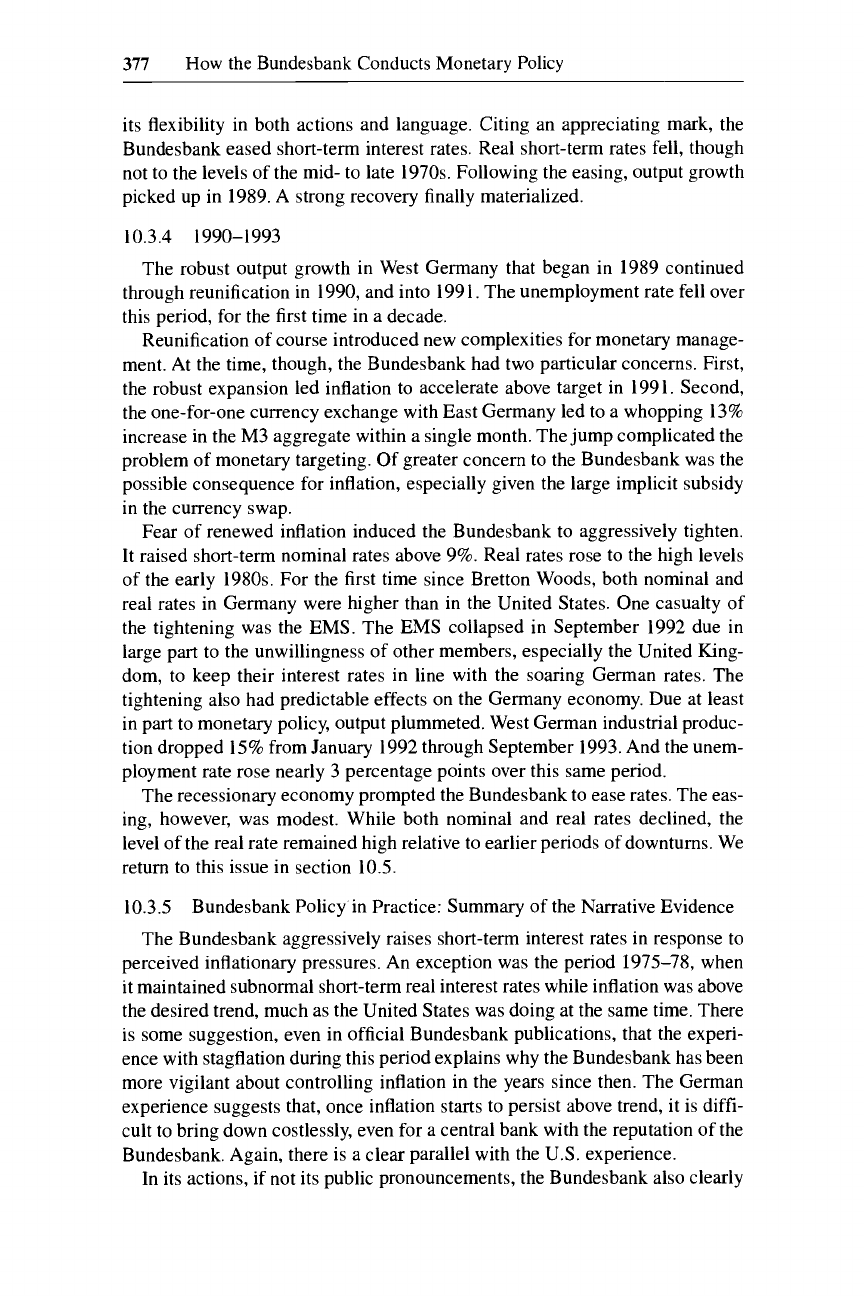

10.3.4 1990-1993

The robust output growth in West Germany that began in 1989 continued

through reunification in 1990, and into 1991. The unemployment rate fell over

this period, for the first time in a decade.

Reunification of course introduced new complexities for monetary manage-

ment. At the time, though, the Bundesbank had two particular concerns. First,

the robust expansion led inflation to accelerate above target in 1991. Second,

the one-for-one currency exchange with East Germany led to a whopping 13%

increase in the M3 aggregate within a single month. The jump complicated the

problem of monetary targeting. Of greater concern to the Bundesbank was the

possible consequence for inflation, especially given the large implicit subsidy

in the currency swap.

Fear of renewed inflation induced the Bundesbank to aggressively tighten.

It raised short-term nominal rates above 9%. Real rates rose to the high levels

of the early 1980s. For the first time since Bretton Woods, both nominal and

real rates in Germany were higher than in the United States. One casualty of

the tightening was the EMS. The

EMS

collapsed in September 1992 due in

large part to the unwillingness of other members, especially the United King-

dom, to keep their interest rates in line with the soaring German rates. The

tightening also had predictable effects on the Germany economy. Due at least

in

part to monetary policy, output plummeted. West German industrial produc-

tion dropped 15% from January 1992 through September 1993. And the unem-

ployment rate rose nearly 3 percentage points over this same period.

The recessionary economy prompted the Bundesbank to ease rates. The eas-

ing, however, was modest. While both nominal and real rates declined, the

level of the real rate remained high relative to earlier periods

of

downturns. We

return to this issue in section 10.5.

10.3.5

Bundesbank Policy in Practice: Summary of the Narrative Evidence

The Bundesbank aggressively raises short-term interest rates in response to

perceived inflationary pressures. An exception was the period 1975-78, when

it maintained subnormal short-term real interest rates while inflation was above

the desired trend, much as the United States was doing at the same time. There

is some suggestion, even

in

official Bundesbank publications, that the experi-

ence with stagflation during this period explains why the Bundesbank has been

more vigilant about controlling inflation in the years since then. The German

experience suggests that, once inflation starts to persist above trend, it is diffi-

cult to bring down costlessly, even for a central bank with the reputation of the

Bundesbank. Again, there is a clear parallel with the U.S. experience.

In its actions, if not its public pronouncements, the Bundesbank also clearly

378

Richard Clarida and Mark

Gertler

takes into account the performance of the real economy. While it desires to

control inflation, it will not do

so

at

any cost. Conversely, a soft economy with

an appreciating D-mark normally induces the Bundesbank to ease.

A

case can

be made, though, that in recent years the easings have been more modest rela-

tive to the overall condition of the economy.

What role does targeting play in the day-to-day formulation of policy? The

targets do not define a rigid rule for money growth. In the period

1975-93

the

Bundesbank failed to meet its money-growth target in

9

of

19

possible in-

stances. Rather, as the Bundesbank has made clear on numerous occasions, the

targets are to be viewed as guidelines. They provide the policy decision with a

clear reference point. The Bundesbank is free to deviate from this reference

point. But it is expected to explain the circumstances that lead it to do

so.

In

this way the targets place discipline on the policymaking process.

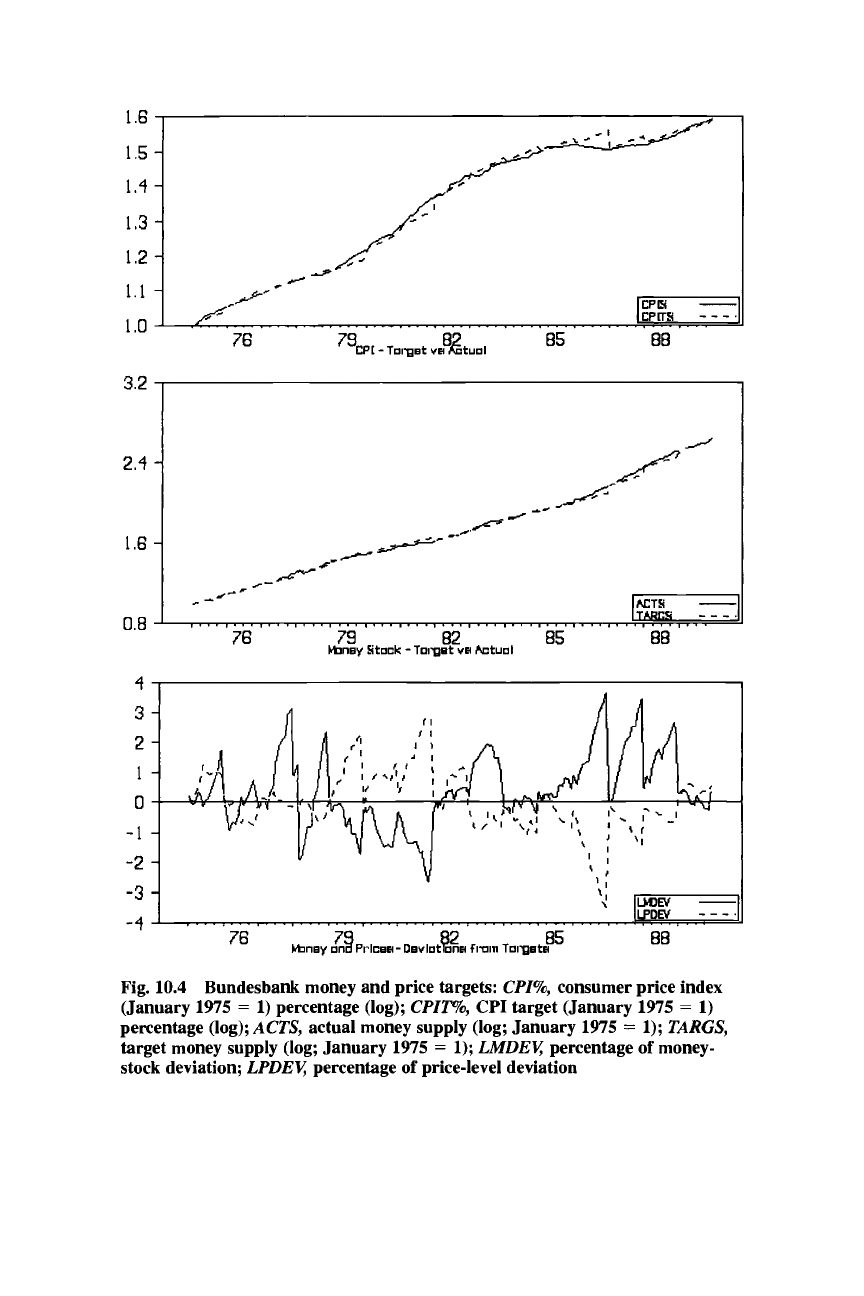

The pattern of deviations from the inflation and money-growth targets are

in our view symptomatic of the implicit stabilization component in the Bunde-

sbank policy rule. The top panel of figure

10.4

plots the target price level (in

logarithms) implied by the sequence of target inflation rates, relative to the

actual price level. The middle panel does the same for the money supply. Note

that during the high inflation of the late

1970s

and early

1980s

the Bundesbank

persistently accommodated overshooting of the price target by simply rebench-

marking the path for the target price each year. That is, it made no attempt to

target a long-term path for the price level, presumably because it feared the

consequences for the real economy.

The bottom panel plots the percentage deviation of each variable from its

target. Note that between

1979

and

1989

the two series are almost mirror im-

ages of one another. This strong negative relationship between the price-level

and money-stock deviations also reveals an element of stabilization within the

policy rule. Generally speaking, when the price level significantly overshoots

its target, the Bundesbank pursues a contractionary policy that tends to push

the money supply below target.

As

we have been emphasizing, the Bundes-

bank’s toleration of this overshooting is evidence of a stabilization concern. In

a way, the simultaneous undershooting of the money-growth target provides it

with a formal justification not to tighten further.

Conversely, in periods where the price level is significantly under target, the

Bundesbank often pushes money growth above target. The undershooting of

the price target presumably gives it leeway to ease monetary policy. In these

situations, as we have discussed, it usually cites an overvalued D-mark to ratio-

nalize its aims.

10.4

Identifying the Bundesbank’s Policy Reaction Function:

A

Structural VAR Approach

In section

10.3

we developed a set of informal conclusions about the nature

of Bundesbank policy. In this section and the next we probe the issues further

1.6

1.5

1.4

1,3

1.2

1.1

1

.o

3'2

I

2.4

1.6

0.8

Fig. 10.4 Bundesbank money and price targets:

CPZ%,

consumer price index

(January 1975

=

1) percentage (log);

CPZT%,

CPI target (January 1975

=

1)

percentage

(log);

ACTS,

actual money supply (log; January 1975

=

1);

TARGS,

target money supply (log; January 1975

=

1);

LMDEY

percentage

of

money-

stock deviation;

LPDEY

percentage

of

price-level deviation

380

Richard Clarida and Mark

Gertler

by estimating policy reaction functions. Based on the previous discussion, we

take as the Bundesbank's policy instrument the day-to-day interest rate. Our

goal then is to identify an empirical relationship that is useful for characteriz-

ing how the Bundesbank adjusts the short-term rate over time.

In general, identifying

a

reaction function for central bank policy involves

confronting two basic complex issues. First, one has to take

a

stand on the set

of information to which the central bank responds. The central bank may have

a primary goal of stabilizing inflation and output, for example. But it may (and

in general does) take account of

a

far broader set of information than simply

inflation and output. Additional information may be useful for forecasting fu-

ture inflation and future output. Good examples are exchange rates and com-

modity prices. Also, the central bank may make use of intermediate targets

such

as

the exchange rate or the money supply, either because it cannot directly

observe current inflation and current output or because it desires some kind

of

commitment device. Indeed, the discussion in section

10.3

suggests that both

the money supply and exchange rates are factored into Bundesbank policy de-

cisions in an important way.

Second, there is a problem of simultaneity between the policy instrument

and the information set. The Bundesbank may adjust short-term interest rates

in light of news about exchanges rates, for example. But, certainly, the change

in the short-term rate will feed back into the behavior of the exchange rate.

We take

a

two-pronged approach to the identification problem. The first

prong, which we pursue in this section, is to estimate

a

policy reaction function

for the day-to-day rate that is derived from

a

structural VAR model of the Ger-

man macroe~onomy.'~ With this reaction function we can characterize in

a

fairly general way how the Bundesbank adjusts policy in response to distur-

bances, such

as

supply shocks, changes in

US.

monetary policy, exogenous

exchange rate shifts, and

so

on. The benefit of this approach is that we can

address the identification issues by employing relatively few

a

priori restric-

tions (at least relative to other approaches). The cost is that because the esti-

mated reaction function includes all the variables in the VAR it is difficult to

interpret. Therefore, in section

10.5

we move on to the second prong, which

involves imposing additional structure on the basic empirical model developed

in this section.

10.4.1

The General Ident$cation

Strategy

Let

y,

be

a

vector of macroeconomic variables and

e,

be an associated vector

of structural disturbances. The elements of

e,

are mutually orthogonal iid dis-

turbances. They are structural shocks in the sense that they are the primitive

Using

a

Structural VAR to Identify Policy Rules

14.

For

some useful descriptions

of

the structural

VAR

methodology, see Blanchard 1989;

Cali

1992; Sims and Zha 1994; Kim and Roubini 1995; Bernanke and Mihov 1995.

381

How

the

Bundesbank Conducts Monetary Policy

exogenous disturbances to the economy.

A

very general representation of a

macroeconomic framework that determines

y,

is

y,

=

Cy,

+

~A;Y,-~

+

e,,

(1)

where

C

and

Ai

are conformable square coefficient matrices, and where the

diagonal elements

of

C

are equal to zero. Equation

1

simply states that within

this macroeconomy each variable may depend on its own lagged values plus

the current and lagged values of all the other variables in the system. The feed-

back policy rule we are interested in identifying is the equation for the element

of

y,

that is the central bank policy instrument.

The logic of the structural VAR approach

is

to place a priori restrictions on

the contemporaneous interactions among the macroeconomic variables in or-

der

to

identify the coefficient matrix

C.

Once estimates of

C

are available, then

it is possible to identify the dynamic impact of the structural shocks on the

elements of

y,

without placing any further restrictions on the data." For the

element of

y,

that is the policy instrument, the exercise leads to a policy reac-

tion function.

Subtract from each side of equation

1

E,-l{y,},

the expected value of

y,

im-

plied by the model, conditional on information at

t

-

1.

Then define

y,

=

y,

-

E,-,(y,}

as

the forecast error to obtain (dropping time subscripts for conve-

nience):

u

=

Cu

+

e.

(2)

In practice u is calculated as the forecast error of the reduced-form (ie., VAR)

representation of equation

1

(see note 15). Comparison

of

equations

1

and

2

indicates the restrictions on the contemporaneous interactions among the

variables boil down

to

restrictions on the contemporaneous interactions be-

tween the reduced-form innovations. The identifying assumptions, therefore,

take the form of restrictions on

C

(e.g., exclusion restrictions) based on as-

sumptions about causality among the elements of

u.16

Nonpolicy

versus

Policy

Variables

To

organize the identifying assumptions, it is useful to divide elements of

y

into nonpolicy and policy variables.

For

the purpose of studying monetary pol-

icy, we take as a policy variable any variable that the central bank may influ-

-

i=

I

15.

To

see

this, note that the reduced form of equation

1

is

y,

=

x

BJ-,

+

u,,

where

B,

=

(I

-

C)-'A,

and

u,

=

(I

-

C)-'e,.

Since the lagged values of

y,

are orthogonal

to

the vector of reduced-

form disturbances

u,,

estimates of

the

B,

may be readily obtained using least squares. Knowing

both

C

and the

B,

then makes it possible to trace the impact of a shock to any element of

e,

on the

path of any element in

y,.

16.

Roughly speaking, a necessary condition for identification is that the number of restrictions

on

C

(beyond the

zero

restrictions on all the diagonal elements of

C)

be at least as large as the

number of parameters in

C

to be estimated.

E=1

382

Richard Clarida and

Mark

Gertler

ence within the current period (e.g., within the current month). This definition

thus includes not only the central bank's direct policy instrument (e.g., the day-

to-day interest rate), but also observable "jump" variables such

as

the exchange

rate, over which it exerts indirect influence within the period. Due to the

within-period simultaneity, the central bank is effectively choosing values

of

all the variables that move contemporaneously. Presumably, when the central

bank adjusts the short-term interest rate, for example, it takes into account the

implied contemporaneous reaction of the exchange rate.

The dual implication

of

our classification scheme is that nonpolicy variables

respond only with

a

lag to movements in the policy variables. Output may react

over time to a shift in interest rates, for example, but due to adjustment costs

and

so

on, it does not respond instantaneously. From the standpoint of identi-

fication, innovations in the nonpolicy variables are exogenous to the innova-

tions in the policy

variable^.'^

To identify the equation for the policy instru-

ment, therefore, we need to worry only about addressing the possible

contemporaneous simultaneity among the policy variables (e.g., how the day-

to-day rate responds to the exchange rate and vice versa).

10.4.2

The Empirical Model

Variables

We use eight variables to describe the German macroeconomy. Five are non-

policy variables. Of these, three are meant to characterize the state of the Ger-

man economy: industrial production

(ip),

retail sales

(ret),

and the consumer

price level

(p).

The two others reflect important external factors that influence

the German economy: real commodity prices

(cp)

(meant to capture supply

shocks) and the

U.S.

federal funds rate

(8).

The three Bundesbank policy variables are the day-to-day (i.e., short-term)

interest rate

(rs);

the real money supply

(m)

(specifically the broad money ag-

gregate M3 divided by the price level), and the real D-mark/dollar exchange

rate

(er).

We treat the short-term interest rate

as

the Bundesbank's policy in-

strument, for reasons discussed in section 10.2.3.

17. In particular the contemporaneous exogeneity of the nonpolicy variables implies a set of

useful exclusion restrictions on the coefficient matrix

C

in equation

2.

Let u* be the vector of

reduced-form disturbances to the elements of

y

that are nonpolicy variables and let

up<''

be the

vector of reduced-form disturbances to the policy variables. Then equation

2

may be disaggregated

as follows:

where the diagonal elements

of

the submatrices

P

and

CP''

are all equal

to

zero.

The recursive

structure implies we can separate the problem of identifying the equations for nonpolicy variables

from that of doing the same for the policy innovations.

It

also implies that we can use the nonpolicy

innovations as instruments in the policy-innovation equations. We will make

use

of

both

of

these

implications.

383

How

the Bundesbank Conducts Monetary Policy

The real money supply and real exchange rate fit our policy-variable classi-

fication, since the Bundesbank can quickly influence these variables (via its

choice of the short-term interest rate), and because its choice of interest rates

presumably is influenced by these variables.'8 We use the D-marWdollar rate

since our reading of the narrative evidence suggests that it is this exchange rate

that has had the the most influence over Bundesbank policy.

Identifying

Assumptions

the reduced-form innovations are as follows:

Our identifying assumptions about the contemporaneous interactions among

Among the five nonpolicy variables, there is a recursive causal relationship,

ordered as follows: commodity prices, industrial production, retail sales, the

price level, and the funds rate.

The reduced-form money and interest rate innovations (i.e.,

the

money-

demand and money-supply innovations) are given by

(3)

(money demand), and

(4)

(money supply).

The exchange rate innovation

(u")

may be influenced by any of the other

seven innovations in the system (i.e., we place

no

restrictions on the exchange

rate equation).

urn

=

a,uiP

+

a2urS

+

em

u"

=

p,ucp

+

P2um

+

P3uer

+

ers

In general our main results

are

robust to different orderings among the non-

policy variables. Nonetheless, some specific considerations motivated the par-

ticular sequence we picked. Over our sample, oil price shocks primarily drove

movements in real-world commodity prices. Since oil shocks contain a large

idiosyncratic component (due to the Organization of Petroleum Exporting

Countries [OPEC], etc.), it seems reasonable to order commodity prices first

in the system. Also, since movements in the

U.S.

funds rate are unlikely to

affect German output and prices within the period, it seems reasonable to order

this variable last among the nonpolicy variables. We place retail sales after

production, based on the view that production adjusts to movements in demand

with a lag.

Equation

4

reveals our assumptions about the contemporaneous information

that the Bundesbank uses to adjust the short-term rate. This equation is key.

We make two assumptions. First, any contemporaneous information the Bun-

desbank employs in its decision making must actually be available within the

18.

Kim and Roubini

(1995)

also develop a structural VAR model with a nomecursive relation-

ship between the interest rate and the exchange rate.

384

Richard Clarida and

Mark

Gertler

period of its decision. Since news about industrial production, retail sales, and

consumer prices become available only with

a

lag, we exclude innovations in

these variables from the Bundesbank's information set. On the other hand, we

let the Bundesbank adjust the interest rate to contemporaneous innovations in

commodity prices, the money supply, and the exchange rate, since these vari-

ables are directly observed within the period. The second assumption, follow-

ing Kim and Roubini (1995), is that within the period the Bundesbank only

cares about the implications of news in the

U.S.

funds rate for the D-mark/

dollar rate. Thus, the innovation in the funds rate does not enter the reaction

function independently

of

the exchange rate.

The only other relation we restrict is money demand. Equation 3 relates the

demand for real money balances to real output and the nominal interest rate,

in keeping with standard convention.

Intuitively, the identification scheme works as follows: Excluding certain

nonpolicy variable innovations from the money-supply equation

4

permits us-

ing these innovations

as

instruments for the two endogenous right-hand-side

variables, specifically the exchange rate and money-supply innovations. Our

decision criterion (which was based on assumptions about the timing of data

release) led us to exclude more nonpolicy variables than was necessary to

achieve identification. The results, however, do not rely on overidentification.

We also consider

a

just identified version of the model and show that the results

are essentially unchanged.

Sample Period and Estimation

Since our key identifying restrictions are based on assumptions about timing

(e.g., variable

X

affects variable

Y

only with

a

lag), we use monthly data, the

shortest frequency available. The sample period is August 1974 to September

1993. We begin shortly after the dismantling of Bretton Woods and continue

through the early stages of reunification. To ensure that our results are not

influenced by structural changes stemming from reunification, we also con-

sider the sample period August 1974 to December 1989. In general we find

that the results

do

not change over the two different samples.

We estimate the eight variable VARs, entering all variables in log-difference

form except the two interest rates, which are in levels. In addition we impose

two cointegrating relationships: between retails sales and industrial produc-

tion, and between real money balances and industrial production.'" In each

case, cointegration tests justified imposing these long-run restrictions. Finally,

in the VAR we include six lags of each variable, but we stagger the lags

as

follows: 1,

2,

3,

6,

9,

12.

Convention dictates using twelve lags with monthly

19.

We include

a

time trend in the cointegrating vector for real money balances and industrial

production. We use the error-corrcction form rather than the standard log level representation

because in the next section we need to make use of the model's forecasts

of

long-run equilibrium.

Because the error correction imposes long-run restrictions among variables, it is better suited for

making long-run forecasts.

385

How

the Bundesbank Conducts Monetary Policy

data to avoid problems of seasonality. However, because the sample period is

short relative to the number of variables and because we also want to use the

model to make long-horizon forecasts in the next section, we opted for a more

parsimonious parameterization.

10.4.3 Results

We are interested in assessing how the Bundesbank adjusts the short-term

interest rate to disturbances to the economy, particularly in light of the narra-

tive evidence developed in section 10.3. We first report evidence on how the

Bundesbank adjusts the day-to-day rates to within-period news. We then ana-

lyze the response of the interest rate over time to various shocks to the econ-

omy. In this way we are able to characterize policy reaction function for the

Bundesbank.

Policy Response

to

Contemporaneous News

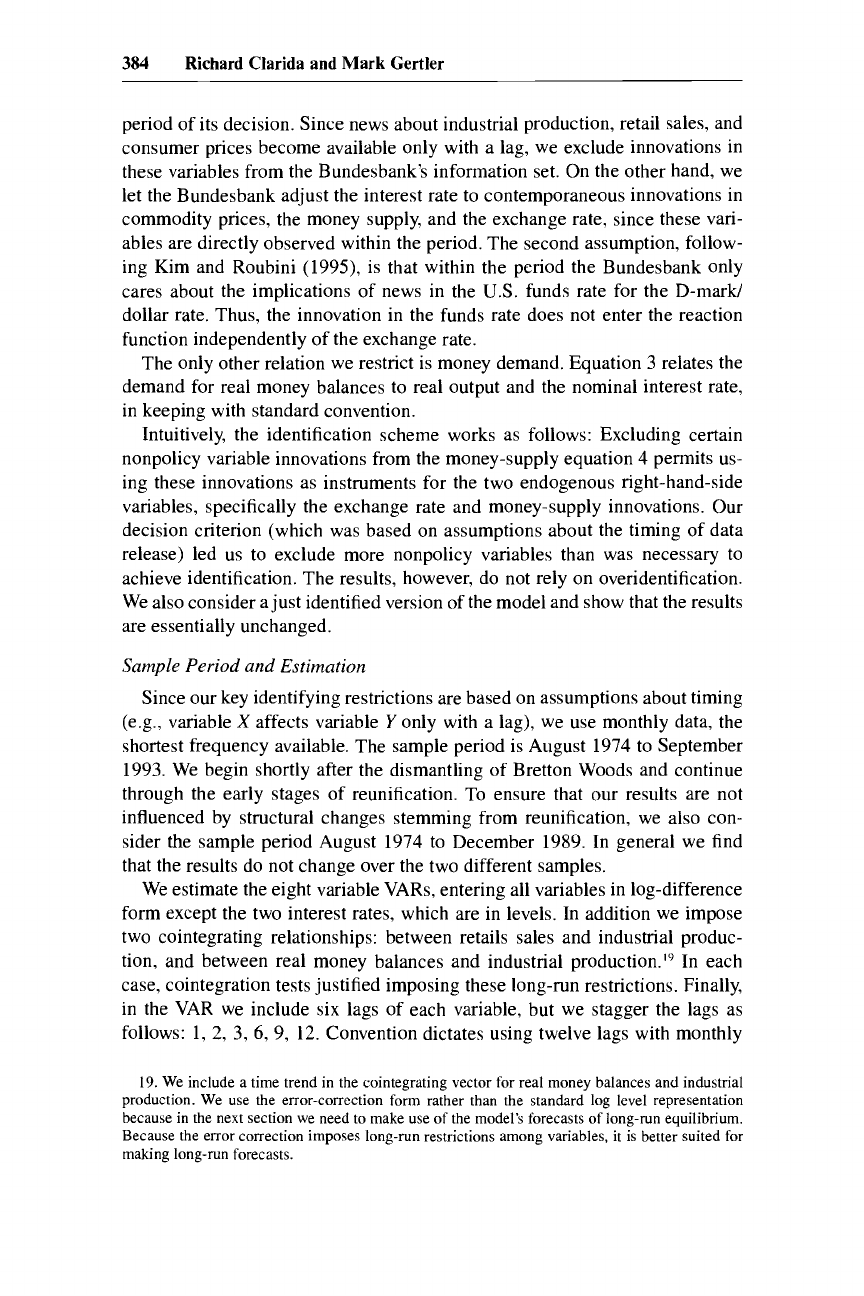

Table 10.2 reports estimates of money-supply equation

4,

which relates the

innovation

in

the interest rate to the innovations in commodity prices, the

money supply, and the exchange rate. The point estimates are as one would

expect. The Bundesbank lets the short-term rate rise in response to news of

increases in inflationary pressures, manifested in either a rise in commodity

prices, a rise in the money supply, or a depreciation of the exchange rate. None

of the news variables is statistically significant, however. This suggests that the

Bundesbank does not try to tightly meet monetary or exchange rate targets

within the month. It also suggests that it is mainly lagged rather than current

information that is fed into the Bundesbank’s policy rule. Within a given month

the Bundesbank tends to maintain a desired short-term rate, given the informa-

tion available at the start of the period.

As

a check that our identification scheme is reasonable, we

also

report the

estimates

of

the two other equations that enter the policy block, the money-

demand and exchange rate relations. In both cases the outcomes are quite sen-

sible. Money demand has a significant negative interest elasticity. An innova-

tion in the funds rate causes the exchange rate to depreciate significantly, while

an innovation in the German short-term rate does the reverse. Finally, a just-

identified version

of

the model yields very similar coefficient estimates for all

three equations.

Dynamic Policy Response

to

Various

Shocks

We next assess how the Bundesbank adjusts the short-term rate over time to

disturbances to the economy,

To

do

so,

we report the response to each of the

eight structural shocks of a subset of four core variables that characterize the

overall state of the economy and policy: industrial production, inflation,

the short-term interest rate, and the real exchange rate. In addition we report

the response

of

the variable that is shocked. Figures

10.5

and 10.6 show the

results, the mean responses of the variables and their

95%

confidence intervals.

386

Richard Clarida and Mark

Gertler

Table

10.2

Structural

VAR

Estimates

Overidentified Model

u"'

=

O.O24u'8

~

0.003~"

+

e"'

(0.021)

(0.001)

u"

=

0.459uLp

+

12.39~"'

+

4.25~"

+

e"

(0.727)

(13.51)

(5.75)

U"

=

0.09u'P

-

0.03u'P

-

0.03~"'

-

0.50uP

-

0.01~"

(0.12) (0.04) (0.09)

(1.01)

(0.003)

(0.002)

(0.39)

+

0.008~~~

-

0.423~"

+

err

Exactly Identified

Model

"1"

=

0.032U'P

(0.019)

u"

=

0.427u'p

(0.756)

uer

=

0.09u'p

(0.12)

+

0.008u"

(0.003)

-

0.003~"

+

,

. .

+

em

+

11.45~"

+

4.04~"

+

.

.

.

+

erb

(0.001)

(13.95) (5.75)

-

0.03u'P

-

0.03~"'

-

0.45uP

-

0.01~"

(0.04)

(0.09)

(1.01)

(0.004)

(0.39)

-

0.392~'"

+

e"

Notes:

The sample is August 1974-September 1993. Estimation is by instrumental variables.

For

the

urn

equation, the instruments are

uC~',

u'p,

u"",

up,

&',

and

e".

For

the

u"

equation the instruments

are

ucp,

u'~,

ur',

up,

and

&'.

For

the

up"

equation, the instruments are

ucp,

u'p,

ZP',

up,

Un,

e",

and

em.

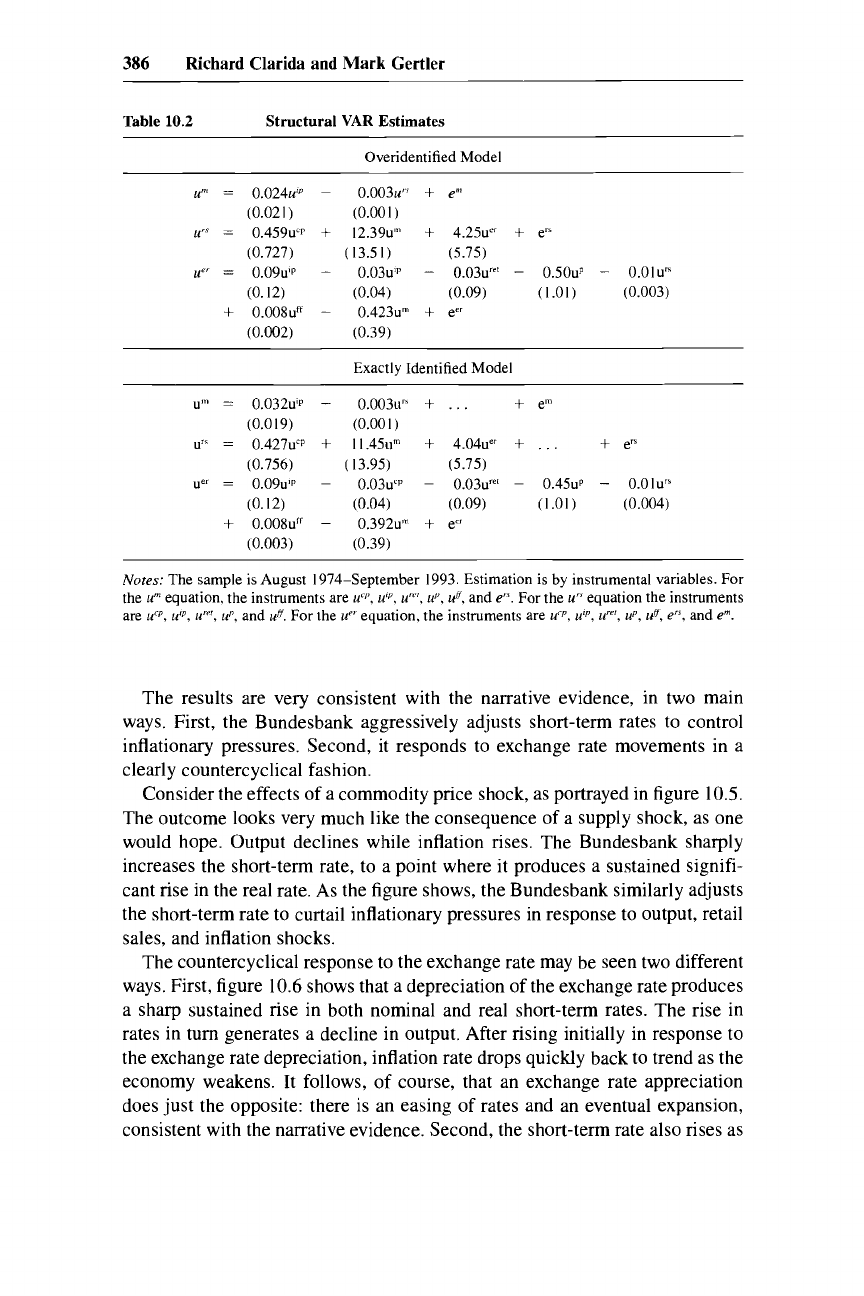

The results are very consistent with the narrative evidence, in two main

ways. First, the Bundesbank aggressively adjusts short-term rates to control

inflationary pressures. Second, it responds to exchange rate movements in a

clearly countercyclical fashion.

Consider the effects

of

a commodity price shock, as portrayed in figure

10.5.

The outcome looks very much like the consequence of a supply shock,

as

one

would hope. Output declines while inflation rises. The Bundesbank sharply

increases the short-term rate, to a point where it produces a sustained signifi-

cant rise in the real rate. As the figure shows, the Bundesbank similarly adjusts

the short-term rate to curtail inflationary pressures in response to output, retail

sales, and inflation shocks.

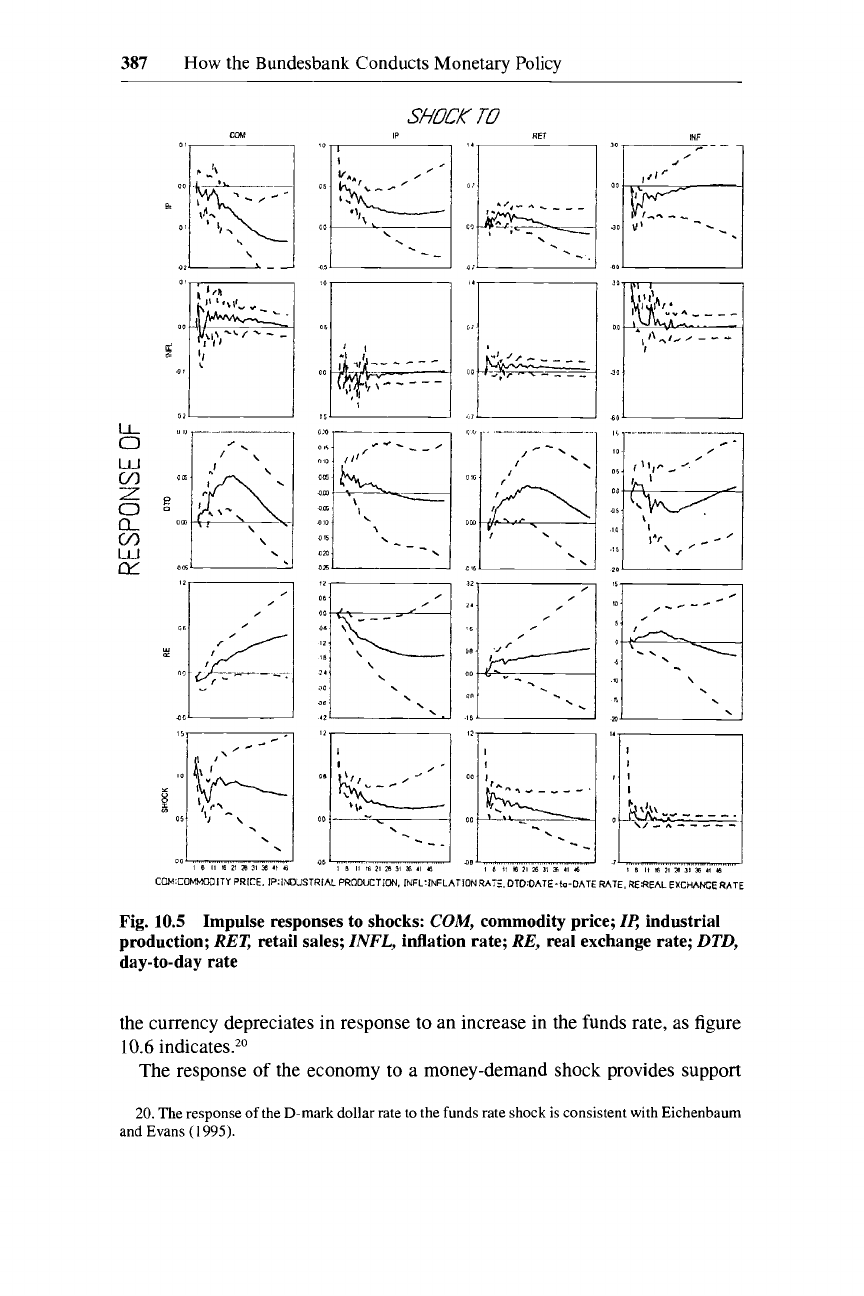

The countercyclical response to the exchange rate may be seen two different

ways. First, figure

10.6

shows that a depreciation of the exchange rate produces

a sharp sustained rise in both nominal and real short-term rates. The rise in

rates in turn generates a decline in output. After rising initially in response to

the exchange rate depreciation, inflation rate drops quickly back to trend

as

the

economy weakens. It follows, of course, that an exchange rate appreciation

does just the opposite: there is an easing

of

rates and an eventual expansion,

consistent with the narrative evidence. Second, the short-term rate also rises as

387

How

the Bundesbank Conducts Monetary Policy

IP

RFl

SHDCK

727

IT-?--

1

-I-

C0M:CD~ITY PRICE. IP:IWUSlRlhL PRNAJCTION. 1NFL:INFLATION

RAX

DT0:OATE-C-DATE RATE, RE:REAL

EXCHANGE

RATE

Fig.

10.5

Impulse responses to shocks:

COM,

commodity price;

Il:

industrial

production;

RET,

retail sales;

INFL,

inflation rate;

RE,

real exchange rate;

DTD,

day-to-day rate

the currency depreciates in response

to

an increase in the funds rate, as figure

10.6

indicates.*"

The response of the economy to a money-demand shock provides support

20.

The

response

of

the D-mark dollar rate

to

the funds rate shock is consistent with Eichenbaum

and Evans

(1

995).

388

Richard Clarida and Mark Gertler

03,

I

FF:FEOERAL FUNDS

RATE.

MIP:MCNEY

SUPPiY.

1ML:INLATICNRATE. DiJ:MTE-Io-OATE

RATE,

REREAL

EXCHANGE

RAiE

Fig.

10.6

supply;

DTD,

day-to-day rate;

RE,

real exchange rate;

INFL,

inflation rate;

14

industrial production

Impulse responses to shocks:

FK

federal funds rate;

M/P,

money

for the view that the Bundesbank treats the short-term interest rate as its policy

instrument. Under strict money targeting, money-demand shocks should in-

duce interest rate fluctuations that in turn affect the real economy. Figure

10.6,

on the other hand, suggests that the Bundesbank accommodates money-

demand shocks. Shocks to money demand have no significant affect on interest

rates or on any other variables, except for real money balances.

389 How

the Bundesbank Conducts Monetary Policy

Impact

of

a Day-to-Day

Rate

Shock

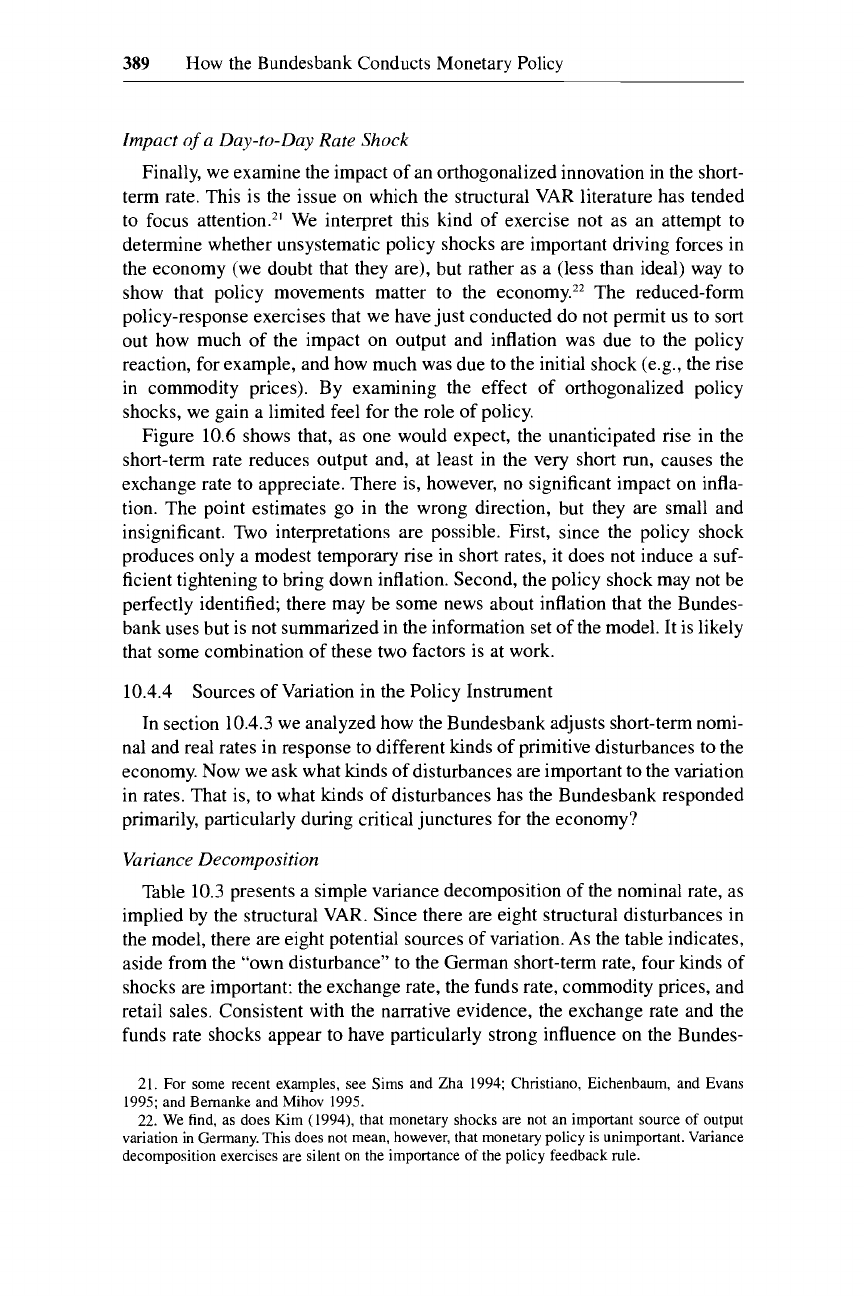

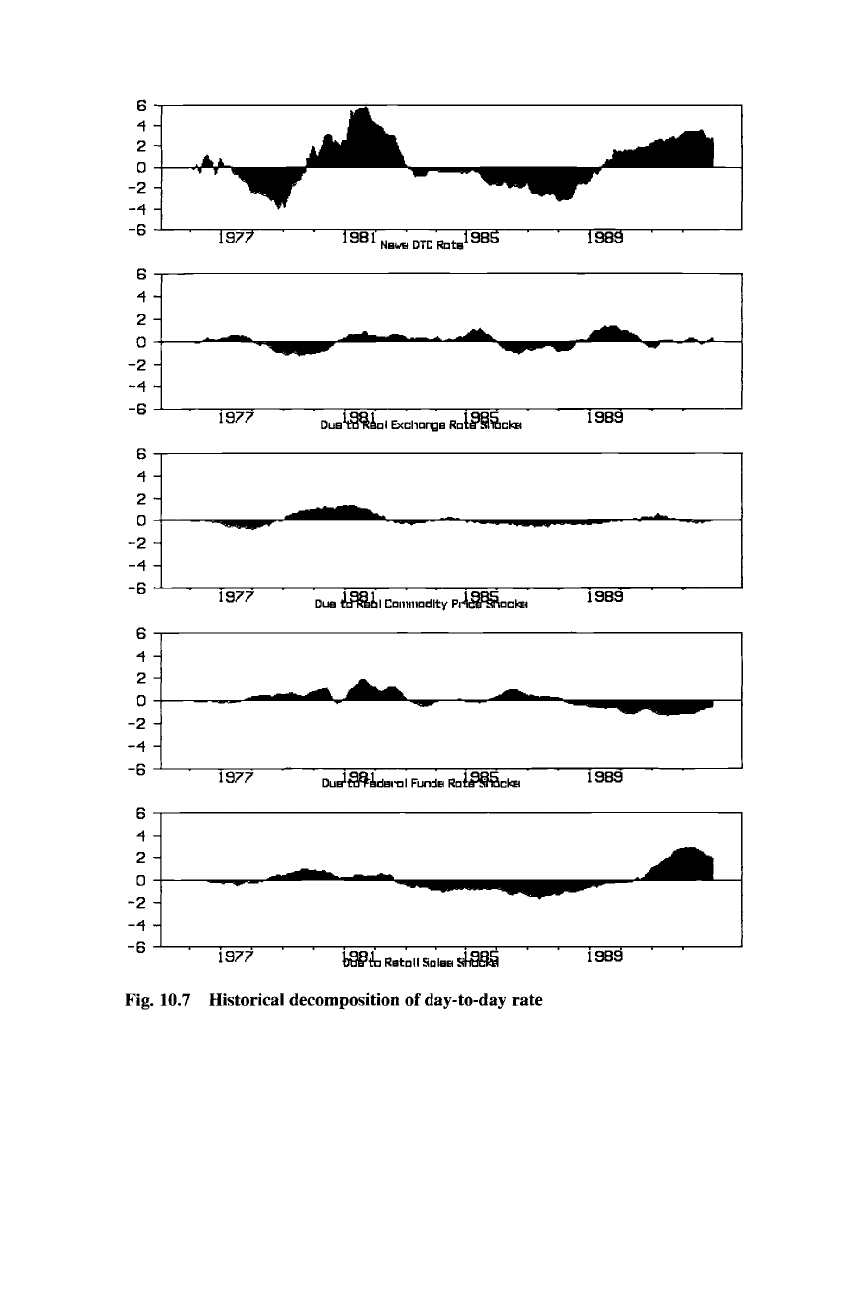

Finally, we examine the impact of an orthogonalized innovation in the short-

term rate. This is the issue

on

which the structural VAR literature has tended

to focus attention.z’ We interpret this kind of exercise not as an attempt to

determine whether unsystematic policy shocks are important driving forces in

the economy (we doubt that they are), but rather as a (less than ideal) way to

show that policy movements matter to the economy.22 The reduced-form

policy-response exercises that we have just conducted do not permit us to sort

out how much of the impact on output and inflation was due to the policy

reaction, for example, and how much was due to the initial shock (e.g., the rise

in commodity prices). By examining the effect

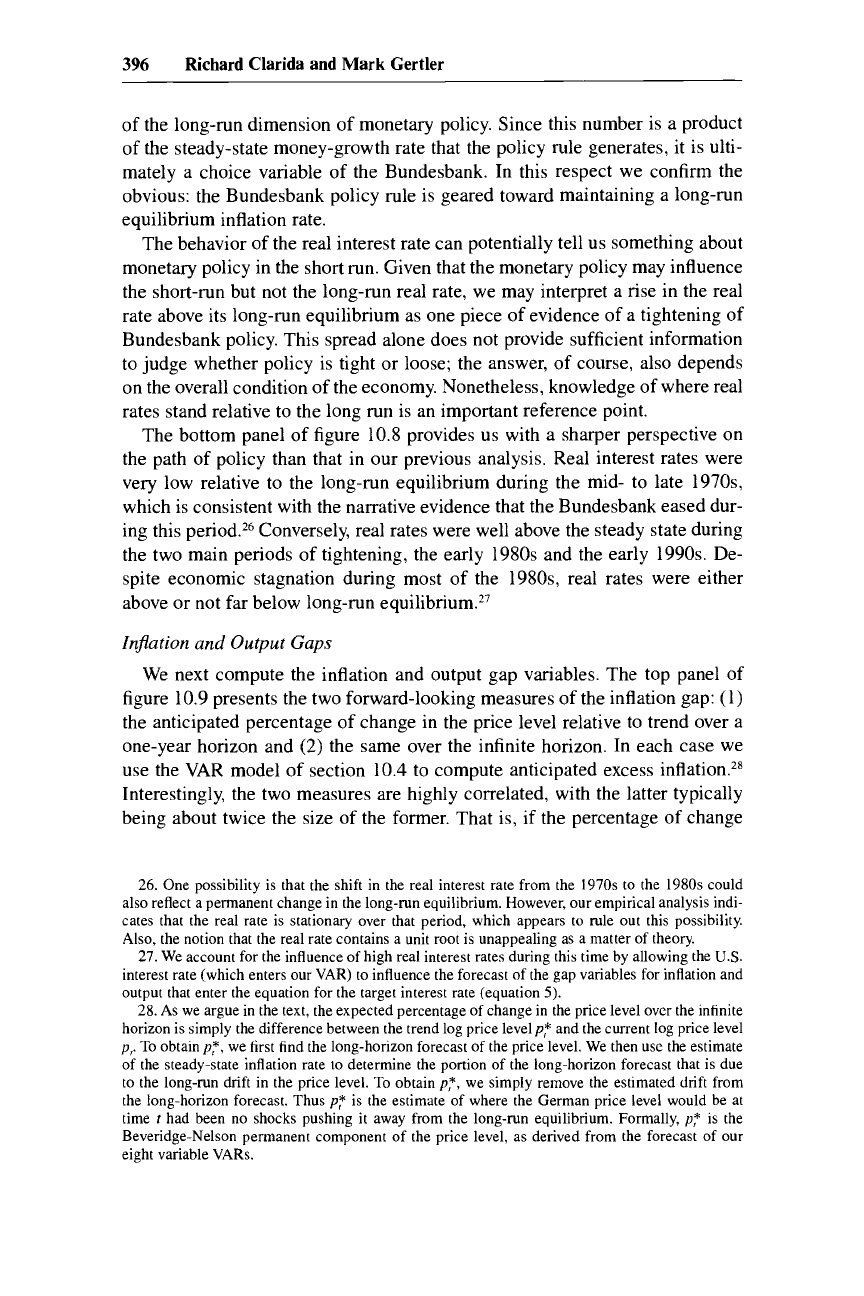

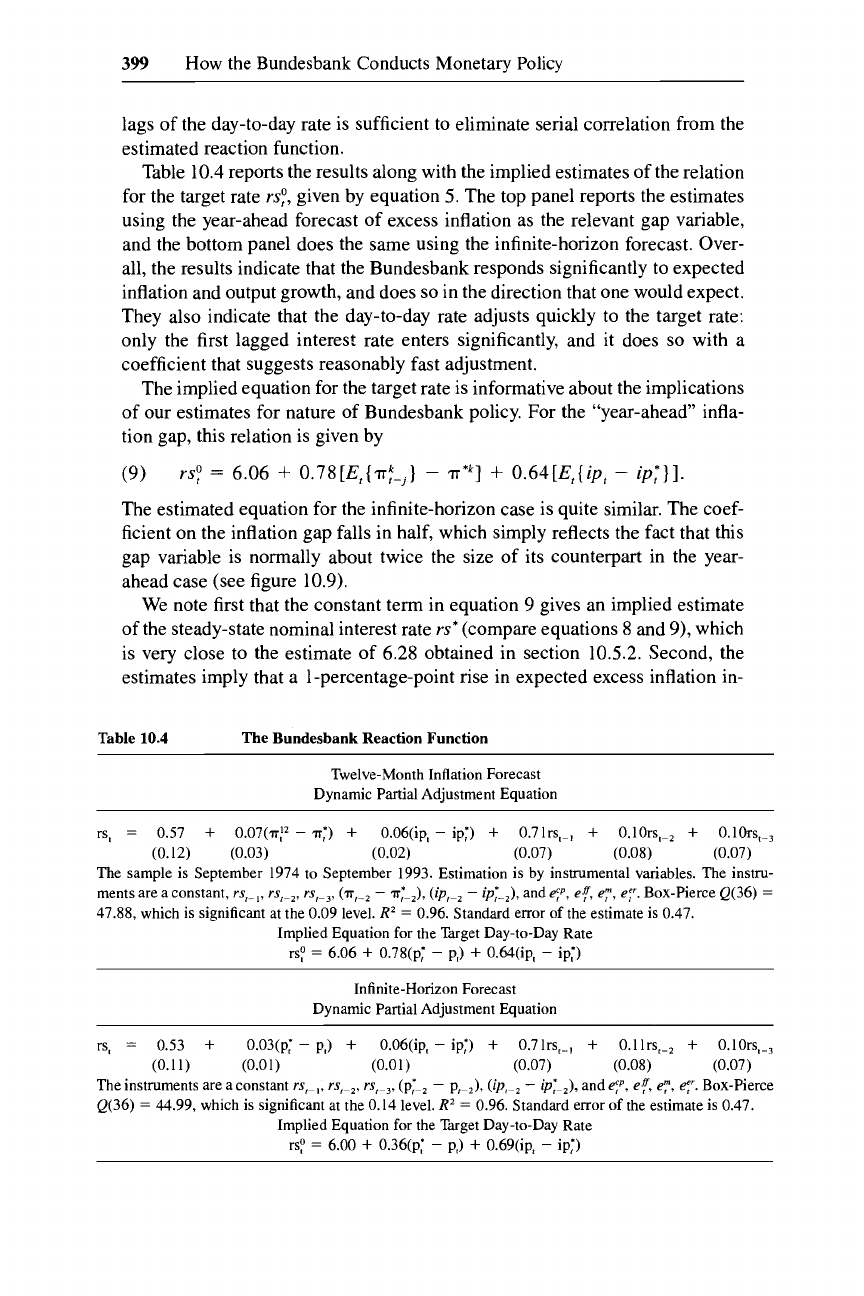

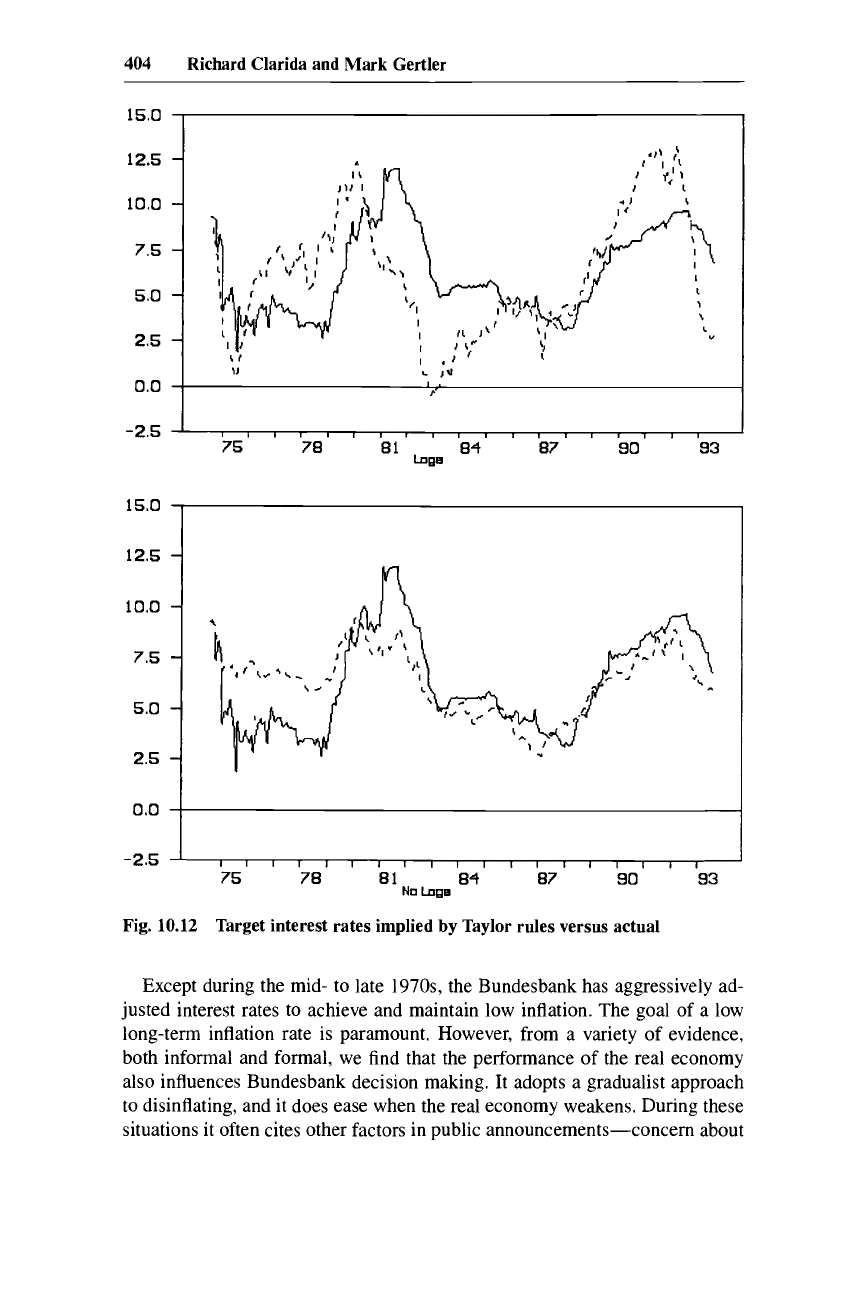

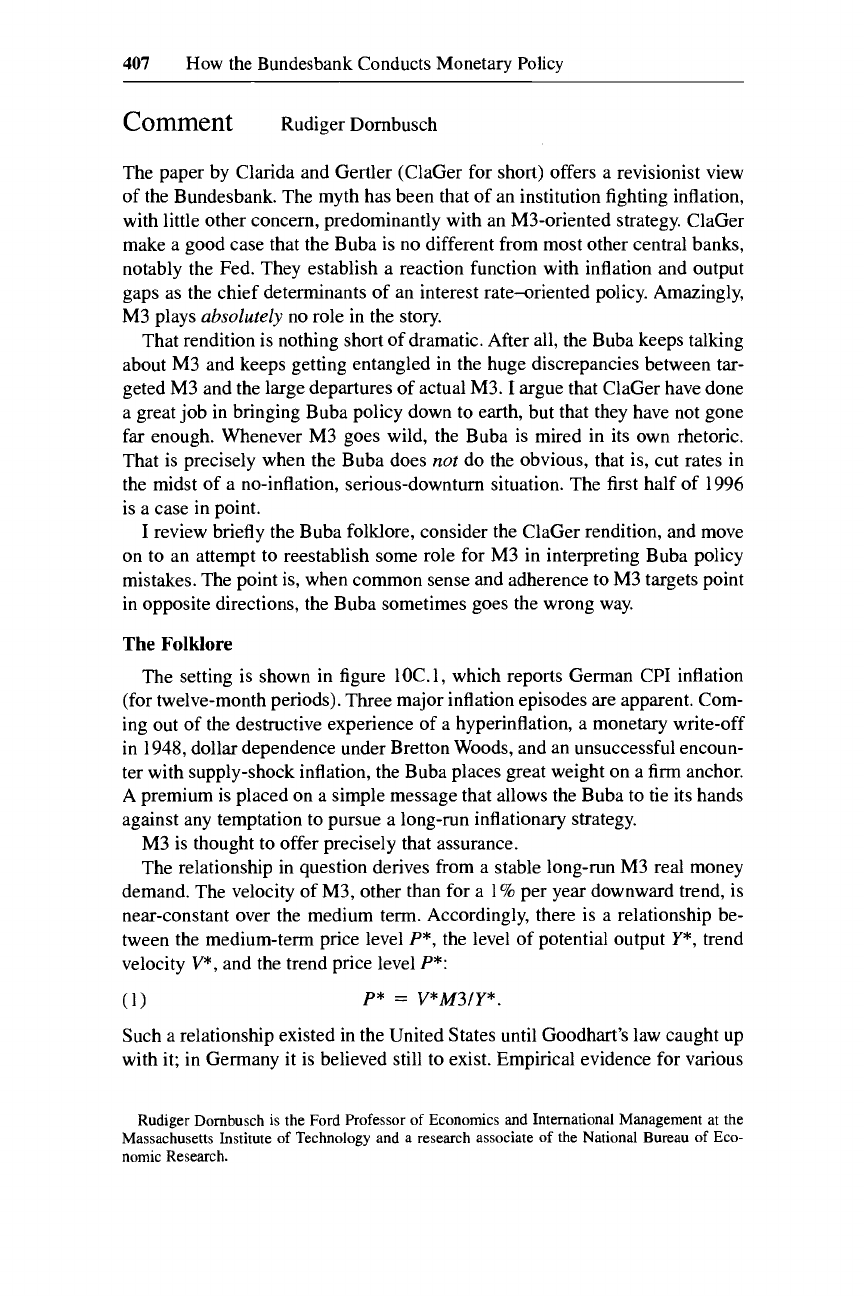

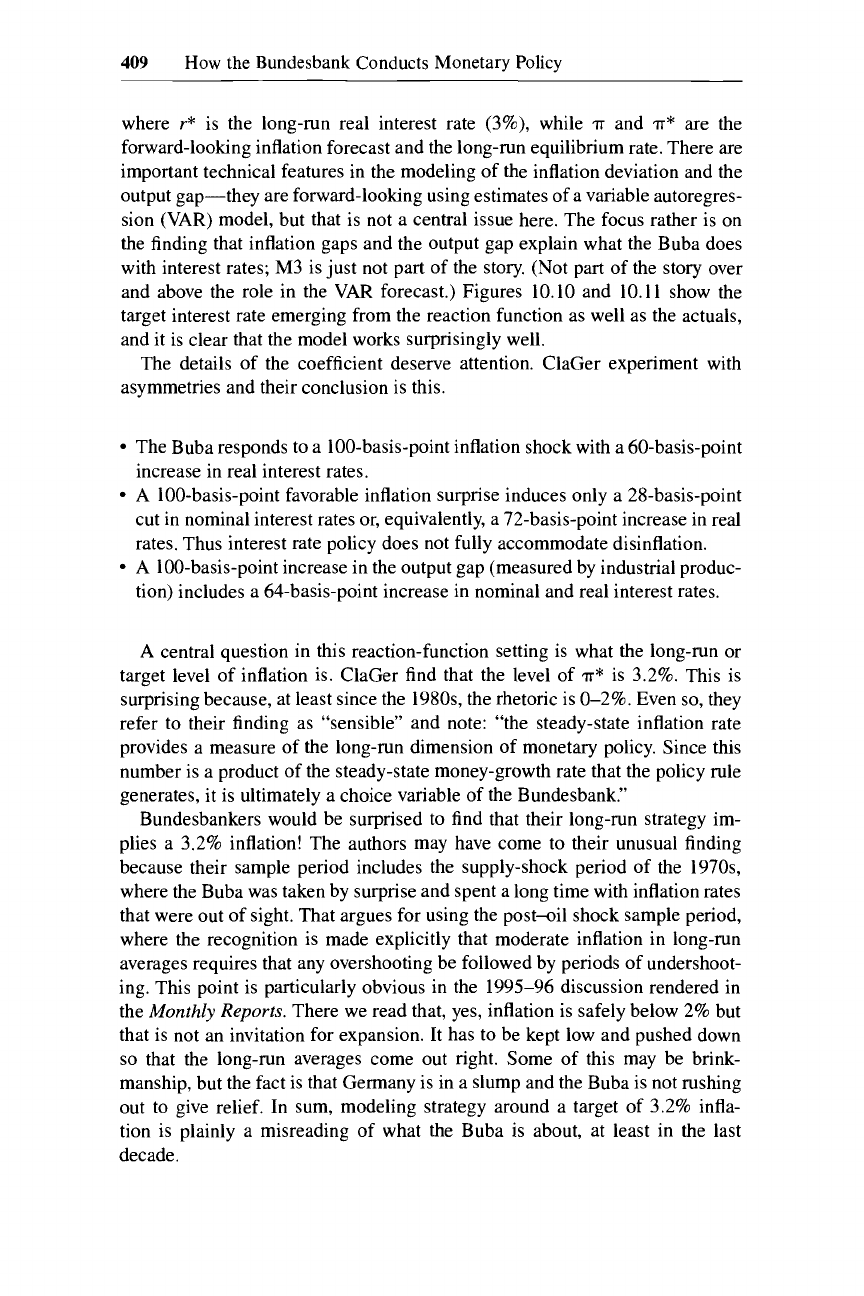

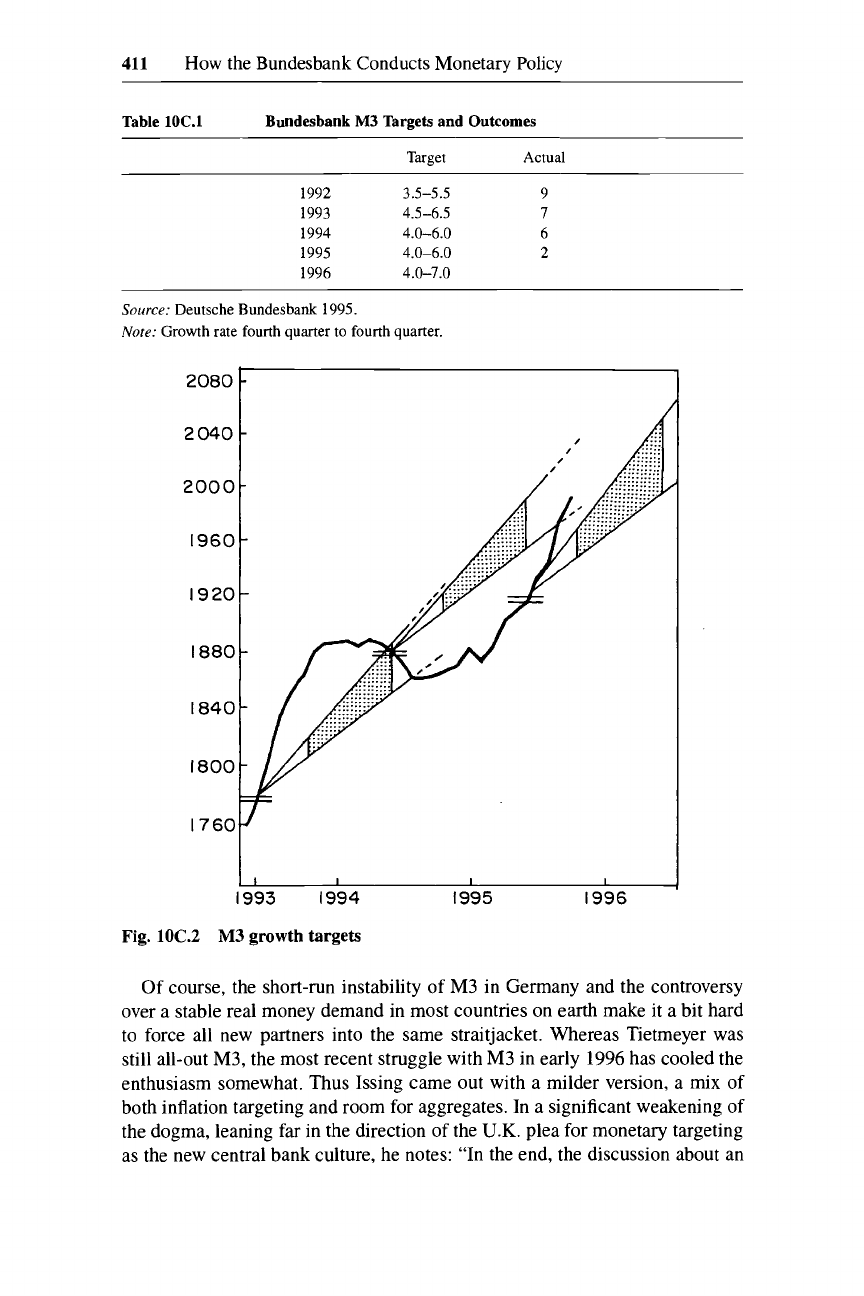

of