Virginia Commonwealth University

VCU Scholars Compass

,+,*2',)&$'&) ),+*)!&)+"-!'$)*!"(

Cultural Appropriation and the Plains' Indian

Headdress

Marisa Wood

Virginia Commonwealth University

'$$'.+!"*&"+"'&$.')#*+ !3(**!'$)*'%(**-,,,+,*

)+'+! '"'$' /',$+,)'%%'&*

12,+!')*

2"*'"$"&*"*)', !++'/','))&'(&**/!'$)*'%(**+!*&(+')"&$,*"'&"&,+,*2',)&$'

&) ),+*)!&)+"-!'$)*!"(/&,+!')"0%"&"*+)+')'!'$)*'%(**')%')"&')%+"'&($*'&++

$"'%(**-,,

'.&$')'%

!3(**!'$)*'%(**-,,,+,*

A U C T U S // VCU’s Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creativity // Social Sciences// May 2017

Introduction

“Cultural appropriation” can be dened as the borrowing from someone else’s culture

without their permission and without acknowledgement to the victim culture’s past. Recently

there has been a conversation taking place between Native American communities and non-In-

dian communities over cases of cultural appropriation, specically the misuse of the Plains’

Indian headdress, which Natives compare to the Medal of Honor. e “hipster subculture”,

which can be dened as a generally pro-consumerist, anti-capitalist group of middle-to-upper

class non-Indian Americans, has selectively appropriated aspects of many minority cultures;

this action has heavily trended toward aspects of Native American culture. As a result, Native

Americans have reacted with outrage as they perceive the oenses to be products of insensitiv-

ity, ignorance and prejudice.

Although there are many justications behind the actions of the hipster subculture,

ultimately, studies suggest that the reasons for appropriation have been subconscious and un-

known even to the subculture itself. Because they do not have a consistent body of rites and

cultural traditions, middle-to-upper class non-Indian Americans who belong to the hipster

subculture selectively appropriate aspects of minority culture such as the Plains’ Indian head-

dresses, not to oend its signicance, but in order to subconsciously make it, and all they

believe it stands for, a part of their own culture.

Cultural Appropriation and the Plains’ Indian Headdress

According to many accounts, non-Indian Americans belonging to the hipster subcul-

ture generally appropriate in an eort to appear worldly. Due to a sincere lack of education,

these eorts appear oensive and insensitive. Many hipster subculture members wear the Plains’

Indian Native American headdress in a highly sexualized manner, which perpetuates stereo-

types of Native women and strips the headdress of its spiritual signicance.

Professors and authors of Introduction to Cultural Appropriation: A Framework for Anal-

ysis, Bruce H. Zi and Pratima V. Rao dene cultural appropriation as a “taking from a culture

that is not one’s own, intellectual property, cultural expressions and artifacts, history and ways

of knowledge” (14). In most cases, cultural appropriation borrows from a minority culture

without acknowledgement of a sensitive past of oppression or other. In addition, Rebecca

Tsosie, author of “Reclaiming Native Stories: An Essay on Cultural Appropriation and Cultur-

al Rights” (2002), claims that cultural appropriation can include tangible as well as intangible

aspects and items such as symbols, songs, and stories. All of these components are pertinent

to the survival of Native Americans as “distinctive cultural and political groups” (Tsosie 301).

Although cultural appropriation can include a variety of aspects and items, the headdress has

become a particular target for controversy. Susan Scadi, author of the article “When Native

American Appropriation Is Appropriate,” suggests a plausible explanation for this controversy

claiming; “ere is a dierence between fashion inspiration and cultural appropriation; only

many people do not understand how to distinguish their actions as one or the other.” Amer-

icans have a notable inability to distinguish cultural inspiration from cultural appropriation,

Cultural Appropriation and the

Plains’ Indian Headdress

1

By Marisa Wood

resulting in many public apologies by corporations, celebrities and other institutions.

As previously mentioned, the most prominent object of appropriation is the Plains’

Indian headdress made of eagle feathers. According to Phillip Jenkins, author of Dream Catch-

ers: How Mainstream America Discovered Native Spirituality, this is the most powerful image

and the most popular image when non-Indians “play Indian” (4). Native Americans like to

compare this headdress with the United States Medal of Honor in hopes that the comparison

will provide perspective that non-Indian Americans can understand. For the most part, the

deep spiritual signicance of this item is not common knowledge for a non-Indian in the 21st

century. Although this fact may lighten the criticisms many non-Indians receive for wearing

the Plains’ headdress, it does not change the eect this appropriation has on Native Americans

of today.

Many Natives have reacted to headdress sightings with outrage against the hipster sub-

culture and non-Indians alike. Author of article “Appreciation or Appropriation,” Tara MacIn-

nis, includes a direct quote from an email written by Kim Wheeler, an Ojibwa-Mohawk from

Winnipeg, to H&M after they introduced headdresses in their Canadian stores. Wheeler

claims that the headdresses are extremely signicant, worn by chiefs as a symbol of respect and

honor, and “they shouldn’t be for sale as a cute accesso-

ry” (Wheeler). Native American Adrienne K, the

founder of the blog forum, Native Appropriations,

claims that “donning a faux feather headdress oends

and stereotypes Native peoples, denies the ‘deep spiritu-

al signicance’ of indigenous garments and makes light

of a ‘history of genocide and colonialism’” (Adrienne

K).

According to Wheeler, the Native American

community has been ghting “the whole ‘hipster head-

dressing’ for a while now” (Wheeler). Although the idea

of cultural appropriation is not new and Native Ameri-

can’s have been ghting their stereotypes for decades, it

has become a trend across the nation and grown in pop-

ularity in recent years. Because many minorities have

made so many strides in the past fty years, the evi-

dence against Native Americans challenges those very

successes. Abaki Beck, author of “Miss Appropriation:

Why Do We Keep Talking About Her?” asserts that

Americans still nd it funny to dress up like an Indian

woman for Halloween and that this undermines the

equality and modern society that America promotes (2). Beck concludes that although the

United States believes they have “reached an exceptional state of being” in a “post ‘racial soci-

ety,’” cultural appropriation does perpetuate harmful and racist stereotypes (2). e mockery

of Native American traditions and rites continues to be condoned nationwide and the eects

are real.

e Eects of Cultural Appropriation

e cultural appropriation of the Plains’ Indian headdress is a pertinent issue in Native

American communities because if this issue can be resolved, it will be the beginning of the end

of the stereotypes that confuse Native American identity in the eyes of both the Indian and the

non-Indian—in this case, the hipster subculture.

2

A U C T U S // VCU’s Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creativity // Social Sciences // May 2017

Figure 1. presents a young woman

donning a Plain’s Indian headdress and

represents the misuse of the headdress as a

cute accessory (Imgarcade).

ere are four clear arguments for the damage caused by cultural appropriation, out-

lined by Zi and Rao. e rst argument is that cultural appropriation harms the appropri-

ated community because it interferes with the community’s

ability to dene itself and establish its own identity (Zi and

Rao 8). Native American identity is already a very strained

concept and it is dicult to see where best to begin rewriting

all the convolution of history. Native Americans have been

forcibly assimilated to forget their culture, languages, and

self, but as contemporary society today and Native American

communities continue to rebuild after all this time, appro-

priation and stereotypes only further propel this culture into

an invisible Otherness. For example, Beck and MacInnis re-

port that Native American outts and Halloween costumes

“draw attention to the hyper-sexualization of First Nations

women” (MacInnis). is sexualization is perhaps one of the

most popular aspects in the 21st century, as pictures of

women lightly clothed in headdresses circulate the Inter-

net constantly. Beck also supports this claim by address-

ing the Native-inspired bikini and oor length headdress

worn by Karlie Kloss on the Victoria Secret catwalk in

2012, as well as the Navajo inspired panties and drinking

asks sold at Urban Outtters in 2011.

Tsosie also sees the continuation of both the Prin-

cess stereotype—Pocahontas—and the Squaw stereo-

type—one “corrupted by the material artifacts of white culture” and “was willing to prostitute

herself to white men” through appropriation (311). Maureen Schwarz, author of Fighting Co-

lonialism with Hegemonic Culture: Native American Appropriation of Indian Stereotypes, claims

that other stereotypes include the Savage Reactionary, the Drunken Indian, Mother Earth, the

One-with-Nature or Ecological Indian, the Spiritual Guide and the Rich Indian (9). ese

images have convoluted the Native American’s own idea of himself or herself for years and

further confused the non-Indian’s understanding of Native Americans.

e second argument is that cultural appropriation can damage or transform culture

practices and harm cultural integrity (Zi and Rao 8). Author of “Of Kitsch and Kachinas:

A Critical Analysis of the ‘Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990” (2010), Hapiuk claims that

“the fear is that native arts and crafts traditions will die out” (1021). If this were to continue

as extremely as it might, it could result in the disappearance of “a valuable national resource”

(1021). Native American arts and crafts are currently a facet of American culture and must

be kept up in their authenticity and practice in order to remain a relevant part of American

culture.

A third argument is that cultural appropriation wrongly allows cultural outsiders to

materially benet themselves from, and at the expense of, the injured group (Zi and Rao 8).

In support of this argument, Hapiuk claims that “as much as $160,000,000 has been unfairly

stolen from the pockets of Indians” due to the sale of “fake goods passed o as genuine” Native

American arts and crafts (1017). Headdresses have been featured in H&M and Navajo print

clothing in Urban Outtters, evidence that Native American cultural items are not being sold

by Native Americans themselves. is is also evidence that these items have become devalued

commodities in the 21st century United States.

e fourth and nal argument asserts that there are two separate harms caused by an

3

A U C T U S // VCU’s Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creativity // Social Sciences // May 2017

Figure 2. is picture of Karlie Kloss

at the Victoria Secret fashion show

serves as an example of the hyper-sexual-

ization of Native American women and

the misuse of the headdress (Getty).

inability to discern “alternative conceptions of what should be treated as property or own-

ership in cultural goods” (Zi and Rao 8, 9). First of all Native Americans’ conceptions of

sovereignty and rights are subsumed within the American legal structure, and second of all,

the American institutions transform Native cultures into property, promoting the right of pri-

vate entrepreneurs to control and sell Native culture (Zi and Rao 8, 9). Hapiuk asserts that

“Native Americans should be able to curtail appropriation of their culture and to maintain

their own culture’s survival” (1021). Although they’ve been trained in the past to assimilate,

contemporary America no longer holds them to that American standard.

Most importantly, cultural appropriation ignores the histories of Native discrimina-

tion and cultural examination eorts by the larger non-Native society (Beck 2). According

to the author of American Indians: Stereotypes & Realities, Devon Mihesuah, these histories

include events such as the Indian Crania Study in the early-to-mid 1800s—a study that re-

quired the U.S. Army to send hundreds of Cheyenne Indians’ heads they had decapitated to

the Smithsonian Institution (43)—and the forced assimilation of Native Americans into the

Carlisle Indian Industrial School—a school established to serve as an example of how military

discipline, harsh punishment, and rigorous studies could ‘kill the Indian and save the man’

(45). ese sensitive histories are also not common knowledge of the average non-Indian

American in the United States. It makes it easier for the hipster subculture to participate in cul-

tural appropriation. However, what this subculture doesn’t understand about the future is that

this continuation dismisses the existence of Native Americans, categorizing them further into

some Otherness (Beck 2). It not only dismisses Native communities culturally, but politically

as well.

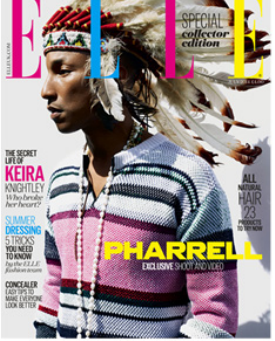

According to Scadi, artist Pharrell Williams’ error on

the 2014 cover of Elle Magazine received criticism because he

wore a Plains’ Indian headdress without either regard for its

cultural signicance or an attempt to turn some of its elements

into something new. Williams made an honest mistake and

did apologize to the Native American community for his ig-

norance. Although cultural appropriation has negative eects,

it does not mean that all Native American culture is o-lim-

its. By denition, cultural appropriation occurs when there

is no acknowledgement toward the culture and no regard for

taboo items. Author of “Henna and Hip Hop: e Politics

of Cultural Production and the Work of Cultural Studies,”

Sunaina Maira, adds that in order to reproduce trends from

another culture, one must work with that culture (354).

If not, one runs the risk of denying the harsh history that

many minorities have endured, a history of which one may

not even be aware.

Hipster Identity

e hipster subculture appropriates cultures while simultaneously taking advantage of

the many benets of membership in the middle-to-upper class society. is demographic uses

and consumes Native American imagery because they wish to distance themselves from their

non-Indian American culture and heritage due to negative actions by their ancestors, includ-

ing colonialism and white imperialism.

For the sake of argument, “hipster subculture” will be dened by several sources. In her

“Postmodern Authenticity and the Hipster Identity” (2013), Kelsey Henke denes the term

4

A U C T U S // VCU’s Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creativity // Social Sciences // May 2017

Figure 3. Pharrell Williams on the

cover of Elle Magazine emphasizes

Scadi’s evidence of cultural appro-

priation in the fashion industry (Elle

UK).

“hipster” as a contemporary subculture of a fashion-forward, creative group of individuals

belonging to the middle or upper class who share a “personal aesthetic of minority culture

symbols and appropriated countercultural fashions. Although this group presents themselves

excluded, uninterested and self-exiled, the hipsters never cut themselves o from their cultur-

ally and economically dominant status in society”. According to Jenkins, as American values

change, the country’s citizens “look to Indians to represent ideals that the mainstream Eu-

ro-American society is losing” (2). In this paper, “the country’s citizens” will only include those

belonging to the hipster subculture.

is subculture is notable for their consumption of minority cultures, best explained

in Henke’s term: “an anti-capitalist pro-consumerist group” that consumes tangible and intan-

gible cultural products in order to self-express. But while they appropriate minority cultures,

they simultaneously take advantage of the many benets of the middle-to-upper class society

to which they naturally belong. ey simultaneously reject and nd comfort in their majority

status. Murphy claims that the popularity of Pocahontas chic-fashion inspired by traditional

Native American dress-and the appropriation of indigenous and other non-white cultures can

be pinpointed to individuals associated with the contemporary hipster subculture. In accor-

dance Scadi argues, “ose of us blessed with choice naturally go in search of cultural capital

and varied experience,” characterizing the vain attempt of hipsters to appear cultured. e

hipster subculture by denition has the nancial advantages to consume, and because they are

fortunate to have a choice in matters of consumption, they express themselves in a cultured

and worldly manner. Native American culture is a victim of this consumption among many

other minority cultures and the Plains’ Indian headdress just one object of curiosity for the

hipster subculture.

Henke and Murphy both claim that lately the hipster subculture has “heavily trended

towards appropriations of Native American culture” (Murphy 2). However, contrary to initial

reactions from Native Americans, Henke suggests that hipsters do have a genuine appreciation

for the cultural capital it produces. ey consume tangible and intangible cultural products

such as media, art, and nostalgia. Consumerism is their primary means of self-expression,

not solely a tool for a rebellious end, and their purchases consist of retooled, old countercul-

tural symbols. Most hipsters are more concerned with consuming cool rather than creating

it. Henke and other cultural commentators see a possible correlation between the adoption

of minority symbols and the rebellion against one’s own class. ey want to create as much

distance as they can between themselves and an ordinary “Christian-inspired existence,” “me-

diocre,” “a slow suicide” (11). In conclusion, the eorts of hipsters to appropriate do show to

be genuine signs of appreciation and respect, although these eorts do not appear that way to

Native Americans, evident by reactions such as those by Kim Wheeler and Adrienne K. Mur-

phy suggests a dierent perspective, that perhaps this demographic appropriates Native Amer-

ican imagery “in an attempt to manifest revolutionary identities and assuage white imperialist

guilt” (2). is idea suggests that cultural appropriation is aected more by the identity crisis

hipsters are facing and less by the identity crisis that Native Americans are facing.

While Kulis, Brown, Wagaman, and Tso demonstrate no outside strain on the identity

of Native American youth (292), Murphy claims that the hipster subculture that is appropriat-

ing Native American culture does not identify with their heritage. e hipster wishes to “dis-

tance herself from the whiteness of the Bush era, globalization and corporate personhood and

return to a pre-colonized America that she perceives as genuine, peaceful and pure” (Murphy

3). In the recent 2008 recession the American dream was shattered, “leaving once potentially

prosperous youth with conicted feelings of deance and remorse” (Murphy 4).

According to Mark Greif, turning to minority suering as a source of identication

5

A U C T U S // VCU’s Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creativity // Social Sciences // May 2017

can free white Americans from their whiteness, with its stain of Eisenhower, the bomb, and

the corporation (9). Murphy suggests that Native American culture represents a pre-colonized

America—genuine, peaceful, and pure—and therefore, the hipster subculture wishes to em-

body these characteristics, while still maintaining the economic and social mobility granted

by their privileged majority backgrounds (5). Murphy claims that, not only do these hipsters

make attempts to identify themselves, but also that they wish to breathe in new life and new

modes of self-expression because ethnicity becomes a spice or seasoning that can liven up the

dull dish that is mainstream white culture (6). Murphy observes one universal defense for this

trend in question given by the demographic in question: “but I just think it’s cool” (9). Mur-

phy claims that nothing is ever just cool; there is always an unconscious structure to it all, like

the unspoken connotation of the feather headdress, the chieftain, and the dream catcher, that

represent exotic freedom and purity.

Author of “How to Live Without Irony,”

Christy Wampole suggests that hipster’s adopt irony

because (1) our society has exhausted its ability to

produce new culture and (2) the inuences of the In-

ternet, which allow greater media consumption and a

reprioritization of the importance of virtual life over

reality. American society lacks a strong traditional

cultural community, compared to societies world-

wide. Because the nation is a mixed salad bowl of

dierent cultures, over the years, citizens have been

exposed to very dierent cultural norms. It has creat-

ed a raised awareness, and perhaps, due to this, Hen-

ke suggests the hipster subculture is “[celebrating] low

culture they’ve been instructed to avoid” (13). e

historical stain of whiteness has pushed American cit-

izens to nd comfort in other cultures for their rigid morality or at least rigid list of practices.

Henke also claims that through a collective reworking of symbols subcultures engage in a con-

scious act against social injustices. e forced assimilation and removal of Native Americans

is a viable social injustice against which these hipsters are ghting. With this new perspective

behind the motives and minds of the hipster subculture, the original criticism they received can

be reconsidered and directed elsewhere.

Contributing Factors

e most inuential factors contributing to the hipster subculture’s appropriation of

the Native American headdress would be their (1) lack of awareness of the signicance of the

Plains’ Indian headdress, (2) corporations’ marketing of culturally appropriated merchandise,

(3) Native Americans’ own stereotypical self-representation, and (4) the false notion that the

Native Americans are no longer a relevant community.

Universally the preponderance of evidence indicates that education would be the most

successful solution for cultural appropriation of Native American culture. Annette Jaimes

claims that a lot of racism that Native Americans face in American today remains unexposed

to the public—there is a gap in non-Indians’ knowledge of Native Americans (40). Similarly,

Beck asserts that these oensive actions occur because the vast majority of Americans do not

know much about Native American culture and are not educated enough to understand the

signicance of the traditions that they appropriate (2). Sanitized versions of Native American

6

A U C T U S // VCU’s Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creativity // Social Sciences // May 2017

Figure 5. Two young men stand in notable

spiritual poses in face paint and headdresses

to represent the general association between

spirituality and Native American culture

(Apihtawikosisa).

history make it impossible for upper to middle class non-Indians to access a full understanding

of accurate U.S. history. It disables them from making their own intelligent decisions, especially

when it comes to expressing themselves. Murphy points out those wearers of the Plains’ Indi-

an headdress often believe that they are honoring Native culture as opposed to perpetuating

racism. is supports the notion of an education gap— an immense lack of knowledge on

the subject of Native American culture in non-Indians in the United States (7). According to

Jenkins, most of the people wearing headdresses “think of it as a homage to native peoples and

some misguided attempt at respect” (1). ey’re not doing it maliciously but they are coming

at it in the wrong way (Jenkins 1). If the hipster subculture can make it a priority to educate

themselves on the actions in which they are participating, it could be enough to stop them from

participating at all. For now, it is their responsibility to educate themselves.

It does not help the diluted understanding of Native Americans that corporations and institu-

tions are also partaking in the appropriation of Native American culture. According to Beck,

those who do view non-Native girls on blogs wearing headdresses on blogs like “this-is-not-

racist-.tumblr.com” need to know that the true villain is the evil CEO, the racist designer,

and bigoted corporate America. e fashion industry is continuously on watch especially after

Victoria’s Secret, H&M, Urban Outtters, and Elle Magazine, among others, faced the re that

they did due to their thin distinctions between inspiration and appropriation. It is not only the

corporations at fault.

Author of “Becoming the White Man’s Indian: An Examination of Native Ameri-

can Tribal Web Sites,” Rhonda S. Fair argues that some

Native Americans capitalize on the commodication of

their culture as well (1). Member-focused Internet sites

run by Native Americans use historical photographs but

also provide context and emphasize contemporary Na-

tive American tribal events. Native-run cites catered to

non-Indians generally play upon “the phantom image of

e Indian” (Fair 5). In order to draw in consumers, these

Native American’s will represent themselves on their web-

sites in the very way that non-Indians expect—the false

expectations made up of the longstanding stereotypes.

According to Fair, when a website is directed toward

tribal members, a chief or council member is likely to

appear in a suit and tie or dress, while a web site direct-

ed toward outsiders shows the chief wearing traditional

or “authentic” clothing (206). ese sites will be pre-

pared with black-and-white photographs, people don-

ning headdresses and traditional dress, and people participating in actions such as carving. Fair

asserts that Native Americans merely appropriate the White Man’s Indian for economic gain

and appropriation seems too supercial—tribes are doing more than just appropriating; they

seem to be identifying with these images in daily life (208). It is as much the responsibility of

the Native Americans as it is the responsibility of the non-Indians to rework these stereotypes.

e many Native Americans that have capitalized on the commodication of their own culture

discredit other Native’s arguments against misappropriation and continuation of stereotypes. In

order to create a widespread universal understanding and clear confusion for non-Indians, all

Native Americans have to agree that they will not contribute to the problem.

Beck claims that the non-Indians engaging in and supporting cultural appropriation

believe that they can comment on it—that one doesn’t have to know who Tecumseh was to

7

A U C T U S // VCU’s Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creativity // Social Sciences // May 2017

Figure 5. Sioux Indians photograph

demonstrates an example of images

that promote the phantom image of

Native Americans (Brenchley).

know what a headdress is and that everyone has the right to defend what they wear and what

they consider beautiful (2). e United States’ main ideals do support a person’s right to ex-

press oneself as he or she desires. Tsosie defends the hipster subculture in this respect, claiming

that non-Indians may nd it dicult to understand why Indian people would seek to con-

trol intangible aspects of their culture or why Indian people would protest the appropriation

(301). Many non-Indian responses demonstrate a disregard for Native reactions to appropri-

ation, believing them to be oversensitive. Author of “American Indian Intellectualism and the

New Indian Story,” Elizabeth Cook-Lynn asserts that nobody really cares what Indians think

about any particular current national or global issue because the place of Indians is in a mythi-

cal past, painted in cartoons like Pocahontas, John Wayne westerns, or the plethora of western

and romance novels that capitalize on stereotypes about

Indians as either noble or bloodthirsty savages (57). Ac-

cording to Murphy’s source, lmmaker Jim Jarmusch,

“Native Americans ‘are now [considered] mythological;

they don’t even really exist – they’re like dinosaurs’” (9).

Beck claims that most non-Indians are unaware that Na-

tive Americans are still part of white culture and soci-

ety (2). According to Mihesuah that “there are approx-

imately 2.1 million Indians belonging to 511 culturally

distinct federally recognized tribes or an additional 200

or so unrecognized tribes” in America alone today (23).

In addition, Beck claims that schools we only teach about

Native Americans “in relation to war or that illusionary

phrase ‘the West’” (2). Generalized terms and stereotypes

allow Americans to distance themselves from these issues

and detach themselves from the material conditions of living Americans (Beck 2). Beck argues

that this knowledge gap contributes to the idea that Natives are usually thought about in the

past tense (2). MacInnis claims that the distinction between appreciation and appropriation is,

ultimately, the responsibility of the consumer. Cultural appropriation will only stop when the

consumers understand what it is they are doing and why it upsets Native Americans the way

that it does.

According to Tsosie, the United States is the ultimate cosmopolitan liberal union so

Americans nd it dicult to understand why control of Native culture should “belong” to

Native people. Under liberal tradition, if non-Indians want to dress up like Indians then they

should have the freedom to do so (Tsosie 310). Although the United States generally prides

itself on being post-racial and accepting of all people, the United States also prides itself on the

freedoms of its citizens. ese two ideals do not always work together perfectly, supported by

the general fact that racism is not extinguished. Freedom of expression allows cultural appro-

priation amongst other things, so it is not a matter of the government to deal with this issue. It

is between these two communities—the Native Americans and the hipster subculture—to work

things out together and come to an understanding.

Conclusion

Modern Native American communities have expressed emotionally charged reactions,

both passionate and angry, about the cultural appropriation of the Plains’ Indian headdress for

a variety of valid reasons outlined in this research paper. e passion and anger of the Native

American population is unfairly aimed at the hipster subculture. It is not necessarily the fault

of hipsters that they lack a full and comprehensive understanding of Native American history

8

A U C T U S // VCU’s Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creativity // Social Sciences // May 2017

Figure 6. e image shows members

of Native American tribes performing

a tribal chant at a Pow Wow in 2009

and demonstrates the relevancy and

closeness of their culture (Moeller).

and Native American culture. e headdress is a symbolic image for Native culture, but it is

more than the headdress for the Native community—this issue represents the disregard of

Native American histories and of their relevancy in the 21st century; it represents the faults

in the educational systems that are meant to provide young citizens with a well-rounded and

unbiased perspective of history. Hipsters appropriate the headdress due to a convoluted un-

derstanding of Native American’s past, present, and future. ese ideals are embedded in the

minds of Americans, therefore there is a great feat before the United States—the rewriting of

Native American stereotypes and the rewriting of their stories in textbooks. Native Americans

were the rst to civilize the land of the United States. Today, they are barely recognized as a

relevant and modern ethnicity, their traditions misunderstood by the majority of the nation.

If this disregard continues, it will create a further divide between non-Indians and Indians

further pushing them into some Otherness, disregarding them as a culture/ethnicity. Although

Europeans made a systematic attempt to extinguish Native American culture, there is now a

chance to rebuild and ll in the holes between what remains of this culture. e ndings of

this research do not apply solely to the members of the minority culture, but to members of

all cultures. It is an imperative United States principle to protect the equality and freedoms of

all its citizens, to welcome all cultures with open arms. In order to abide by this principle, the

Native American culture will be restored, respected, and honored.

9

A U C T U S // VCU’s Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creativity // Social Sciences // May 2017

10

A U C T U S // VCU’s Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creativity // Social Sciences // May 2017

References

Apihtawikosisa. “Spare Me” Photo. Apihtawikosisan. Apihtawikosisan, 5 July 2012. Web. 3

December 2014.

Brenchley, Julis. “Sioux” Photo. Brenchley Collection. Maidstone Museum & Bentlif Art Gal-

lery. Web. 3 December 2014.

Cook-Lynn, Elizabeth. “American Indian Intellectualism and the New Indian Story” American

Indian Quarterly 20.1 (1996): 57-76. JSTOR. Web. 7 October 2014.

Elle UK. “Not Everyone Is Happy About Pharrell Williams’ Elle UK Cover” Photo. Hungton

Post. eHungtonPost.com, Inc, 4 June 2014. Web. 8 December 2014.

Fair, Rhonda S. “Becoming the White Man’s Indian: An Examination of Native American

Tribal Web Sites” Plains Anthropologist 45.172 (2000): 203-213. JSTOR. Web. 28 October

2014.

Greif, Mark, Kathleen Ross and Dayana Tortorici, eds. What Was the Hipster? A Sociological

Investigation (Brooklyn, NY: n+1 Foundation, 2010), 9. Web. 12 October 2014.

Getty. “Karlie Kloss Wears Native American Headdress At Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show.”

Photo. Hungton Post. eHungtonPost.com, Inc, 8 November 2012. Web. 2 Decem-

ber 2014.

Hapiuk, William. “Of Kitsch and Kachinas: A Critical Analysis of the ‘Indian Arts and Crafts

Act of 1990” Stanford Law Review 53.4 (2001): 1009-1075. JSTOR. Web. 22 September

2014.

Henke, Kelsey. “Postmodern Authenticity and the Hipster Identity.” Forbes & Fifth 3.11

(2013): 114-129. Oce of Undergraduate Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity. Web.

23 October 2014.

“Festival Face Hipster.” Photo. Imgarcade. Disqus. Web. 7 December 2014.

Jaimes, Annette. “American Racism: e Impact on American-Indian Identity and Survival.”

Race. Ed. Roger Sanjek and Steven Gregory. Piscataway: Rutgers UP, 1994. 41-61. Web.

6 September 2014.

Jenkins, Phillip. Dream Catchers: How Mainstream America Discovered Native Spirituality. Ox-

ford: Oxford University Press, 2004. 1-21. Web. 6 September 2014.

K., Adrienne. “But Why Can’t I Wear a Hipster Headdress?” Native Appropriations (blog), 27

April 2010. Web. 12 October 2014.

Kulis, Stephen, Alex Wagaman, Crescentia Tso, and Eddie Brown. “Exploring Indigenous

Identities of Urban American Indian Youth of the Southwest.” Journal of Adolescent Re-

11

A U C T U S // VCU’s Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creativity // Social Sciences // May 2017

search 28.3 (2013): 271-298. SAGE Publications. Web. 8 October 2014.

MacInnis, Tara. “Appreciation or Appropriation.” e Genteel. e Genteel, 9 September

2013. Web. 23 October 2014.

Mihesuah, Devon. American Indians: Stereotypes & Realities. Gardena: SCB Distributors, 2009.

Web. 15 September 2014.

Moeller. “Dance for Mother Earth Powwow Moves O-Campus” Photo. Michigan Daily. Uni-

versity of Michigan, 5 April 2009. Web. 6 December 2014.

Murphy, Jessyca. “e White Indin’: Native American Appropriations in Hipster Fashion.”

Academia.Edu. Diss. e New School for Public Engagement, 2013. Web. 12 October

2014.

Scadi, Susan. “When Native American Appropriation Is Appropriate.” Time. Time Inc., 6

June 2014. Web. 21 October 2014.

Schwarz, Maureen. Fighting Colonialism with Hegemonic Culture: Native American Appropri-

ation of Indian Stereotypes. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2013. Web. 25

September 2014.

Tsosie, Rebecca. “Reclaiming Native Stories: An Essay on Cultural Appropriation and Cultur-

al Rights” Arizona State Law Journal 34 (2002): 299-358. Social Science Electronic Publish-

ing Inc. Web. 7 October 2014.

Wampole, Christy. “How to Live Without Irony.” NY Times. e New York Times Company,

17 November 2012. Web. 19 November 2014.

Zi, Bruce and Pratima Rao. “Introduction to Cultural Appropriation: A Framework for

Analysis.” Borrowed Power. Piscataway: Rutgers UP, 1997. 1-26. Web. 20 November 2014.