An

interactive approach

introductory finance class

ABSTRACT

Within the introductory finance course, students learn that a financial manager needs to

increase the intrinsic value of his/her firm and that the value

the

firm’s expected future cash flows, discounted by the weighted

(WACC). The WACC

equation represents

introductory class such as time value of money and capital budgeting

WACC should highlight

the formula’s link to

statement information.

Because practitioners apply WACC in several different ways, coverage

should also address issues such as the Capital Asset Pricing Model, the dividend growth model,

and the effect of book and

market value inputs. Because of

introductory course, finance professors must consider the appropriate pedagogical style to use for

effectively teaching WACC. This

instill

in students a strong grasp of WACC concepts.

Keywords: Business education,

active learning,

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

interactive approach

to teaching WACC

concepts in an

introductory finance class

Anne Drougas

Dominican University

Richard Walstra

Dominican University

Steve Harrington

Dominican University

Within the introductory finance course, students learn that a financial manager needs to

increase the intrinsic value of his/her firm and that the value

is derived from

the present value of

firm’s expected future cash flows, discounted by the weighted

average cost of capital

equation represents

a critical component

for several topics within the

introductory class such as time value of money and capital budgeting

. Instructor coverage of

the formula’s link to

accounting by

drawing data from financial

Because practitioners apply WACC in several different ways, coverage

should also address issues such as the Capital Asset Pricing Model, the dividend growth model,

market value inputs. Because of

time constraints within the

introductory course, finance professors must consider the appropriate pedagogical style to use for

effectively teaching WACC. This

paper describes a technology-

based assignment intended to

in students a strong grasp of WACC concepts.

active learning,

weighted average

cost of capital

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

1

concepts in an

Within the introductory finance course, students learn that a financial manager needs to

the present value of

average cost of capital

for several topics within the

. Instructor coverage of

drawing data from financial

Because practitioners apply WACC in several different ways, coverage

should also address issues such as the Capital Asset Pricing Model, the dividend growth model,

time constraints within the

introductory course, finance professors must consider the appropriate pedagogical style to use for

based assignment intended to

cost of capital

INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Teaching introductory finance is a challenge, even for experienced instructors

(Biktimirov

& Nilson, 2003). Part of the challenge relates to instructing general business majors

who might not see the relevancy of the finance course nor easily grasp the concepts (Hess, 2005).

The course is vital, however, in that it builds upon its prerequisite, f

(McWilliams & Peters, 2012), and affords the non

few curricular opportunities, to meaningfully link financial statement information with

managerial decision-making.

Although

relevancy of the introductory course’s topical coverage, the course further challenges faculty to

identify teaching tools that engage students in an active learning process. Brown (2005) proposed

that active learning involve

s a new paradigm based on understanding and discovery versus

memorization and recall. S

tudents are visual learners (Baker & Post, 2006) who prefer

assignments that clearly communicate the relevance of topics, such as finance, within the

workplace (Bale & D

udney, 2000). As Biktim

need an “arsenal” of teaching tools at their disposal to develop student

engage students at a level “appropriate” for the curriculum and course objectives (Ha

Saunders, 2009).

Regarding topical coverage in the introductory finance class, seminal studies by Berry

and Farragher (1987) and Cooley and Heck (1996) surveyed finance professors and the results

demonstrated an emphasis on cost of capital. The Be

identified cost of capital/capital structure as one of the three primary topics at both the

undergraduate and graduate level, and within that area,

Surveys by Gup (1994) and Lai

, Kwan

practitioners also placed a high value on cost of capital. Student surveys have echoed these

results (Krishnan, Bathala, Bhattacharya, & Richie, 1999; Balachandran, Skully, Tant, &

Watson, 2006; Lai, et al., 2010).

T

he concept of WACC is central to the field of finance and pervades many other

however,

finance professors must balance their coverage of WACC with other priorities. The

sheer volume of material available within an introductory finance textb

design extremely difficult. As an example, a review of the

finance textbook (Brigham & Houston, 2013) reveals the scope of the challenge. Early chapters

address core topics such as time value of money, r

chapters explore other finance topics including cost of capital and capital structure. Relative to

cost of capital, faculty must decide when to introduce the concept and to what degree of detail.

Early on, many instr

uctors might simply incorporate an assumed rate. Others might elect to

carefully guide students through the components of the WACC calculation. Additionally, faculty

must determine the extent to which they will challenge students to use detailed financial

statements as a source for cost of capital data. In a review of finance textbooks, McWilliams and

Peters (2012) found little integration of financial statement information.

The assignment described below

of WACC within the introductory finance class. By incorporating an interactive Excel

worksheet, instructors can (1) develop student knowledge of the WACC formula and the factors

that affect WACC, (2) reinforce the importance of financial statements

between topics generally covered earlier in the course (e.g., bond and stock valuation) with those

covered nearer to the end (e.g., capital budgeting, cash flow and risk estimation). The assignment

helps students discover how el

ements of the financial statements drive WACC and allows them

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Teaching introductory finance is a challenge, even for experienced instructors

& Nilson, 2003). Part of the challenge relates to instructing general business majors

who might not see the relevancy of the finance course nor easily grasp the concepts (Hess, 2005).

The course is vital, however, in that it builds upon its prerequisite, f

inancial accounting

(McWilliams & Peters, 2012), and affords the non

-

finance major an opportunity, perhaps one of

few curricular opportunities, to meaningfully link financial statement information with

Although

finance majors ar

e more likely to understand the

relevancy of the introductory course’s topical coverage, the course further challenges faculty to

identify teaching tools that engage students in an active learning process. Brown (2005) proposed

s a new paradigm based on understanding and discovery versus

tudents are visual learners (Baker & Post, 2006) who prefer

assignments that clearly communicate the relevance of topics, such as finance, within the

udney, 2000). As Biktim

ir

ov and Nilson (2003) suggest, finance educators

need an “arsenal” of teaching tools at their disposal to develop student

-

centric assignments that

engage students at a level “appropriate” for the curriculum and course objectives (Ha

Regarding topical coverage in the introductory finance class, seminal studies by Berry

and Farragher (1987) and Cooley and Heck (1996) surveyed finance professors and the results

demonstrated an emphasis on cost of capital. The Be

rry and Farragher survey, for example,

identified cost of capital/capital structure as one of the three primary topics at both the

undergraduate and graduate level, and within that area,

WACC

was the principal sub

, Kwan

, Kadir, Abdullah and Yap

(2010) disclosed that

practitioners also placed a high value on cost of capital. Student surveys have echoed these

results (Krishnan, Bathala, Bhattacharya, & Richie, 1999; Balachandran, Skully, Tant, &

he concept of WACC is central to the field of finance and pervades many other

finance professors must balance their coverage of WACC with other priorities. The

sheer volume of material available within an introductory finance textb

ook can make course

design extremely difficult. As an example, a review of the

twenty-one

chapters of a popular

finance textbook (Brigham & Houston, 2013) reveals the scope of the challenge. Early chapters

address core topics such as time value of money, r

isk analysis, and valuation. Additional

chapters explore other finance topics including cost of capital and capital structure. Relative to

cost of capital, faculty must decide when to introduce the concept and to what degree of detail.

uctors might simply incorporate an assumed rate. Others might elect to

carefully guide students through the components of the WACC calculation. Additionally, faculty

must determine the extent to which they will challenge students to use detailed financial

statements as a source for cost of capital data. In a review of finance textbooks, McWilliams and

Peters (2012) found little integration of financial statement information.

The assignment described below

presents a student-

centric approach to teaching th

of WACC within the introductory finance class. By incorporating an interactive Excel

worksheet, instructors can (1) develop student knowledge of the WACC formula and the factors

that affect WACC, (2) reinforce the importance of financial statements

, and (3) create a “bridge”

between topics generally covered earlier in the course (e.g., bond and stock valuation) with those

covered nearer to the end (e.g., capital budgeting, cash flow and risk estimation). The assignment

ements of the financial statements drive WACC and allows them

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

2

Teaching introductory finance is a challenge, even for experienced instructors

& Nilson, 2003). Part of the challenge relates to instructing general business majors

who might not see the relevancy of the finance course nor easily grasp the concepts (Hess, 2005).

inancial accounting

finance major an opportunity, perhaps one of

few curricular opportunities, to meaningfully link financial statement information with

e more likely to understand the

relevancy of the introductory course’s topical coverage, the course further challenges faculty to

identify teaching tools that engage students in an active learning process. Brown (2005) proposed

s a new paradigm based on understanding and discovery versus

tudents are visual learners (Baker & Post, 2006) who prefer

assignments that clearly communicate the relevance of topics, such as finance, within the

ov and Nilson (2003) suggest, finance educators

centric assignments that

engage students at a level “appropriate” for the curriculum and course objectives (Ha

milton &

Regarding topical coverage in the introductory finance class, seminal studies by Berry

and Farragher (1987) and Cooley and Heck (1996) surveyed finance professors and the results

rry and Farragher survey, for example,

identified cost of capital/capital structure as one of the three primary topics at both the

was the principal sub

-topic.

(2010) disclosed that

practitioners also placed a high value on cost of capital. Student surveys have echoed these

results (Krishnan, Bathala, Bhattacharya, & Richie, 1999; Balachandran, Skully, Tant, &

he concept of WACC is central to the field of finance and pervades many other

topics;

finance professors must balance their coverage of WACC with other priorities. The

ook can make course

chapters of a popular

finance textbook (Brigham & Houston, 2013) reveals the scope of the challenge. Early chapters

isk analysis, and valuation. Additional

chapters explore other finance topics including cost of capital and capital structure. Relative to

cost of capital, faculty must decide when to introduce the concept and to what degree of detail.

uctors might simply incorporate an assumed rate. Others might elect to

carefully guide students through the components of the WACC calculation. Additionally, faculty

must determine the extent to which they will challenge students to use detailed financial

statements as a source for cost of capital data. In a review of finance textbooks, McWilliams and

centric approach to teaching th

e topic

of WACC within the introductory finance class. By incorporating an interactive Excel

worksheet, instructors can (1) develop student knowledge of the WACC formula and the factors

, and (3) create a “bridge”

between topics generally covered earlier in the course (e.g., bond and stock valuation) with those

covered nearer to the end (e.g., capital budgeting, cash flow and risk estimation). The assignment

ements of the financial statements drive WACC and allows them

to explore how changes to the various components of the formula will affect WACC. By gaining

an understanding of the intricacies of WACC, students are better prepared to move on to more

advanced finance topics.

The financial

educator’s charge

Saunders (2001) called for greater use of multiple teaching methods and assessment

techniques within the introductory finance course. In a national survey, Saunders

the majority of finance professors relied heavily on traditional lecture and in

way to deliver key material. Hamilton and Saunders (2009) updated this survey and found no

difference in teaching strategies within the intro

educator (1) used the Brigham and Houston (concise) text or some version of the Brigham series,

(2) utilized financial calculators (undergraduate) and formulas (graduate) to solve financial

problems, and (3) relied on in-

class testing as a major determinant for a student’s final grade.

The authors acknowledged the efforts of finance educators who have attempted to engage

students within the introductory finance class through the implementation of case studies

(Nun

nally & Evans, 2003), team projects (Faulk & Smolira, 2008), s

2008

), instant messaging (Michelson & Smith, 2008), and podcasting (Reimers & Singleton,

2008). However, these pedagogies appear to represent exceptions to the rule.

A review of the literature on student learning offers many calls for student

learning. Angelo (1993) encouraged an active, interactive process. Citing the work of Angelo,

Ardalan (2006) stated

“understanding learning styles helps to improve teachi

enhance student learning” (p. 3).

strategies to engage all students.

lecture-

driven “instructor paradigm” to a “learning par

teaching and assessment techniques. This becomes particularly important when educating the

current generation of college students, often ref

members have been described as high

to explore (Windham, 2005). If financial educators are to reach these students, they must first

understand them and then adapt teaching methodologies to suit them. “The Net Gen is oriented

toward

inductive discovery or making observations, formulating hypotheses, and figuring out the

rules. They crave interactivity” (Oblinger & Oblinger, 2005, p. 2.7).

Finance faculty can build an interactive finance course suitable for the Net Gens by

incorporatin

g technology. Faculty have used technology in a number of different ways

(Saunders, 2001); however, they have not always done so successfully (Cudd, Lipscomb, &

Tanner, 2003). Cudd, Lipscomb, and Tanner claim “spreadsheet analysis is the primary tool of

th

e financial manager” (p. 246) and the tech

2005). Technology, therefore,

can bridge students’ abilities with

states, “by using IT properly in the classroom, teaching and learning

new dimension” (p.4.2). The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business

has also emphasized the importance of technology. In its 2002 report by the Management

Education Task Force, AACSB encouraged instructors t

decisions utilizing technology (McWilliams & Peters, 2012).

Recent efforts by

Villanova University to answer AACSB’s call for curriculum change

have reiterated the importance and need to incorporate financial statements within the finance

curriculum. The university created

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

to explore how changes to the various components of the formula will affect WACC. By gaining

an understanding of the intricacies of WACC, students are better prepared to move on to more

educator’s charge

: Emphasizing student-centered learning

Saunders (2001) called for greater use of multiple teaching methods and assessment

techniques within the introductory finance course. In a national survey, Saunders

the majority of finance professors relied heavily on traditional lecture and in

-

class testing as a

way to deliver key material. Hamilton and Saunders (2009) updated this survey and found no

difference in teaching strategies within the intro

ductory finance course. The typical finance

educator (1) used the Brigham and Houston (concise) text or some version of the Brigham series,

(2) utilized financial calculators (undergraduate) and formulas (graduate) to solve financial

class testing as a major determinant for a student’s final grade.

The authors acknowledged the efforts of finance educators who have attempted to engage

students within the introductory finance class through the implementation of case studies

nally & Evans, 2003), team projects (Faulk & Smolira, 2008), s

preadsheet tools (Hallows,

), instant messaging (Michelson & Smith, 2008), and podcasting (Reimers & Singleton,

2008). However, these pedagogies appear to represent exceptions to the rule.

A review of the literature on student learning offers many calls for student

learning. Angelo (1993) encouraged an active, interactive process. Citing the work of Angelo,

“understanding learning styles helps to improve teachi

ng performance and

Ardalan believed finance faculty s

hould use diverse teaching

Barr and Tagg (1995)

advocated movement away from a

driven “instructor paradigm” to a “learning par

adigm” encompassing a variety of

teaching and assessment techniques. This becomes particularly important when educating the

current generation of college students, often ref

erred to as the Net Generation

(Net Gen)

members have been described as high

achievers, technically adept, and multi-

taskers with a need

to explore (Windham, 2005). If financial educators are to reach these students, they must first

understand them and then adapt teaching methodologies to suit them. “The Net Gen is oriented

inductive discovery or making observations, formulating hypotheses, and figuring out the

rules. They crave interactivity” (Oblinger & Oblinger, 2005, p. 2.7).

Finance faculty can build an interactive finance course suitable for the Net Gens by

g technology. Faculty have used technology in a number of different ways

(Saunders, 2001); however, they have not always done so successfully (Cudd, Lipscomb, &

Tanner, 2003). Cudd, Lipscomb, and Tanner claim “spreadsheet analysis is the primary tool of

e financial manager” (p. 246) and the tech

-

savvy Net Gen prefer to learn by doing (McNeely,

can bridge students’ abilities with

industry’s

needs. As McNeely

states, “by using IT properly in the classroom, teaching and learning

are enhanced and given a

new dimension” (p.4.2). The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business

has also emphasized the importance of technology. In its 2002 report by the Management

Education Task Force, AACSB encouraged instructors t

o equip students to make better business

decisions utilizing technology (McWilliams & Peters, 2012).

Villanova University to answer AACSB’s call for curriculum change

have reiterated the importance and need to incorporate financial statements within the finance

curriculum. The university created

a six-

credit hour course integrating the introductory financial

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

3

to explore how changes to the various components of the formula will affect WACC. By gaining

an understanding of the intricacies of WACC, students are better prepared to move on to more

Saunders (2001) called for greater use of multiple teaching methods and assessment

techniques within the introductory finance course. In a national survey, Saunders

discovered that

class testing as a

way to deliver key material. Hamilton and Saunders (2009) updated this survey and found no

ductory finance course. The typical finance

educator (1) used the Brigham and Houston (concise) text or some version of the Brigham series,

(2) utilized financial calculators (undergraduate) and formulas (graduate) to solve financial

class testing as a major determinant for a student’s final grade.

The authors acknowledged the efforts of finance educators who have attempted to engage

students within the introductory finance class through the implementation of case studies

preadsheet tools (Hallows,

), instant messaging (Michelson & Smith, 2008), and podcasting (Reimers & Singleton,

A review of the literature on student learning offers many calls for student

-centered

learning. Angelo (1993) encouraged an active, interactive process. Citing the work of Angelo,

ng performance and

hould use diverse teaching

advocated movement away from a

adigm” encompassing a variety of

teaching and assessment techniques. This becomes particularly important when educating the

(Net Gen)

whose

taskers with a need

to explore (Windham, 2005). If financial educators are to reach these students, they must first

understand them and then adapt teaching methodologies to suit them. “The Net Gen is oriented

inductive discovery or making observations, formulating hypotheses, and figuring out the

Finance faculty can build an interactive finance course suitable for the Net Gens by

g technology. Faculty have used technology in a number of different ways

(Saunders, 2001); however, they have not always done so successfully (Cudd, Lipscomb, &

Tanner, 2003). Cudd, Lipscomb, and Tanner claim “spreadsheet analysis is the primary tool of

savvy Net Gen prefer to learn by doing (McNeely,

needs. As McNeely

are enhanced and given a

new dimension” (p.4.2). The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business

(AACSB)

has also emphasized the importance of technology. In its 2002 report by the Management

o equip students to make better business

Villanova University to answer AACSB’s call for curriculum change

have reiterated the importance and need to incorporate financial statements within the finance

credit hour course integrating the introductory financial

accounting and introductory finance course

throughout the course (McWilliams & Peters, 2012). After conducting an extensive review of the

popular textbooks in finance, McWilliams and Peters discovered that many introductory finance

texts use “skeletal financial statements

financial statements

” (p. 312). Furthermore, the authors suggested that many finance topics,

including the cost of capital, should be taught with a more explicit focus upon financial

statements.

The

financial educator’s charge: Highlighting relevancy of financial applications

In addition to the challenge finance educators face in developing an active, engaging

learning environment, they must focus the learning around topics that are relevant within

finance profession. Sometimes, topics emphasized by financial educators are different than

topics deemed important by practitioners. For example,

practitioner perspective and discovered that CEOs place a higher valu

capital factors than finance professors.

and capital budgeting. Current research highlights papers with a student

to both TVM (e.g., Bianco

, Nelson

2010

). The cost of capital, however defined or measured, underpins both calculations.

In light of the importance of cost of capital from a practitioner’s

coverage of WACC with

in the finance curricula

For example, Pagano and Stout (2004) considered the cost of capital to be fundamental to the

work of finance and accounting professionals and they identified several uses for the tool

addition, Adelman and Cross (2005

by courts and regulators for rate setting in industries such as insurance and utilities. In both

papers, WACC was presumed to be the formula for the cost

Partington, and Peat (2008) conducted a practitioner survey and their findings showed firms used

cost of capital 88% of the time for evaluation techniques

they developed an estimate of WAC

As students gain an

appreciation

must recognize

the purpose of WACC as a rate of return used for valuing a stream of expected

cash flows. Students need to appreciate how the discount rate drives b

decisions and the TVM. Additionally, students must understand that value

organization hinges on capital investment

FEATURES OF THE WACC SPREADSHEET

The spreadsheet assignment provides an interactive approach to the topic of WACC

within the introductory finance course.

from the lead author upon request.

equation with students during class. Next, the instructor describes the spreadsheet students will

use to explore the components of WACC. The starting point for the assignment is a set of

condensed financial statements for a fictitious company. Th

and equity components within the statements. The pre

macros and VBA-

coded control buttons that guide students in a step

various factors that influence

WACC. The spreadsheet minimizes the need for mathematical

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

accounting and introductory finance course

s. Financial stateme

nts were a prevalent theme

throughout the course (McWilliams & Peters, 2012). After conducting an extensive review of the

popular textbooks in finance, McWilliams and Peters discovered that many introductory finance

texts use “skeletal financial statements

without actual integration or derivation of numbers in

” (p. 312). Furthermore, the authors suggested that many finance topics,

including the cost of capital, should be taught with a more explicit focus upon financial

financial educator’s charge: Highlighting relevancy of financial applications

In addition to the challenge finance educators face in developing an active, engaging

learning environment, they must focus the learning around topics that are relevant within

finance profession. Sometimes, topics emphasized by financial educators are different than

topics deemed important by practitioners. For example,

Lai, et al. (2010) investigated the

practitioner perspective and discovered that CEOs place a higher valu

e on accounting and cost of

capital factors than finance professors.

The two primary topics are

time value of money (TVM)

and capital budgeting. Current research highlights papers with a student

-

centric focus pertaining

, Nelson

& Poole, 2010) and capital budgeting (Ben-

Horin & Kro

). The cost of capital, however defined or measured, underpins both calculations.

In light of the importance of cost of capital from a practitioner’s

perspective, increasing

in the finance curricula

will better

prepare students for the workplace.

For example, Pagano and Stout (2004) considered the cost of capital to be fundamental to the

work of finance and accounting professionals and they identified several uses for the tool

addition, Adelman and Cross (2005

)

also highlighted the breadth of applications including its use

by courts and regulators for rate setting in industries such as insurance and utilities. In both

papers, WACC was presumed to be the formula for the cost

of capital. Lastly, Truong,

Partington, and Peat (2008) conducted a practitioner survey and their findings showed firms used

cost of capital 88% of the time for evaluation techniques

while

84% of the respondents indicated

they developed an estimate of WAC

C.

appreciation

of the cost of capital and learn to calculate WACC, they

the purpose of WACC as a rate of return used for valuing a stream of expected

cash flows. Students need to appreciate how the discount rate drives b

oth capital budgeting

decisions and the TVM. Additionally, students must understand that value

creation

organization hinges on capital investment

returns exceeding the cost of capital.

FEATURES OF THE WACC SPREADSHEET

The spreadsheet assignment provides an interactive approach to the topic of WACC

within the introductory finance course.

An electronic copy of the spreadsheet can be obtained

from the lead author upon request.

The instructor begins the process by reviewing

equation with students during class. Next, the instructor describes the spreadsheet students will

use to explore the components of WACC. The starting point for the assignment is a set of

condensed financial statements for a fictitious company. Th

e financial data emphasizes the debt

and equity components within the statements. The pre

-

formatted spreadsheet includes embedded

coded control buttons that guide students in a step

-by-

step fashion through the

WACC. The spreadsheet minimizes the need for mathematical

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

4

nts were a prevalent theme

throughout the course (McWilliams & Peters, 2012). After conducting an extensive review of the

popular textbooks in finance, McWilliams and Peters discovered that many introductory finance

without actual integration or derivation of numbers in

” (p. 312). Furthermore, the authors suggested that many finance topics,

including the cost of capital, should be taught with a more explicit focus upon financial

financial educator’s charge: Highlighting relevancy of financial applications

In addition to the challenge finance educators face in developing an active, engaging

learning environment, they must focus the learning around topics that are relevant within

the

finance profession. Sometimes, topics emphasized by financial educators are different than

Lai, et al. (2010) investigated the

e on accounting and cost of

time value of money (TVM)

centric focus pertaining

Horin & Kro

ll,

). The cost of capital, however defined or measured, underpins both calculations.

perspective, increasing

prepare students for the workplace.

For example, Pagano and Stout (2004) considered the cost of capital to be fundamental to the

work of finance and accounting professionals and they identified several uses for the tool

. In

also highlighted the breadth of applications including its use

by courts and regulators for rate setting in industries such as insurance and utilities. In both

of capital. Lastly, Truong,

Partington, and Peat (2008) conducted a practitioner survey and their findings showed firms used

84% of the respondents indicated

of the cost of capital and learn to calculate WACC, they

the purpose of WACC as a rate of return used for valuing a stream of expected

oth capital budgeting

creation

within an

The spreadsheet assignment provides an interactive approach to the topic of WACC

An electronic copy of the spreadsheet can be obtained

The instructor begins the process by reviewing

the WACC

equation with students during class. Next, the instructor describes the spreadsheet students will

use to explore the components of WACC. The starting point for the assignment is a set of

e financial data emphasizes the debt

formatted spreadsheet includes embedded

step fashion through the

WACC. The spreadsheet minimizes the need for mathematical

calculation of WACC by incorporating

students to study how changes

in

magnitude and direct

ion of WACC. Because students do not need to perform calculations or

gather information, they are able to focus on expanding their knowledge of the WACC formula

and recognizing several factors that influence WACC.

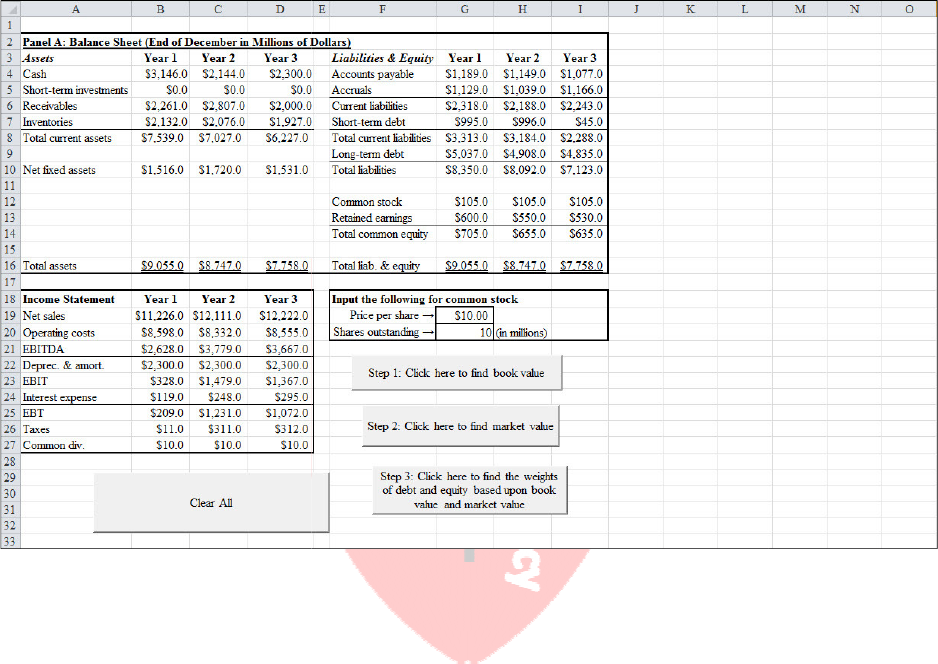

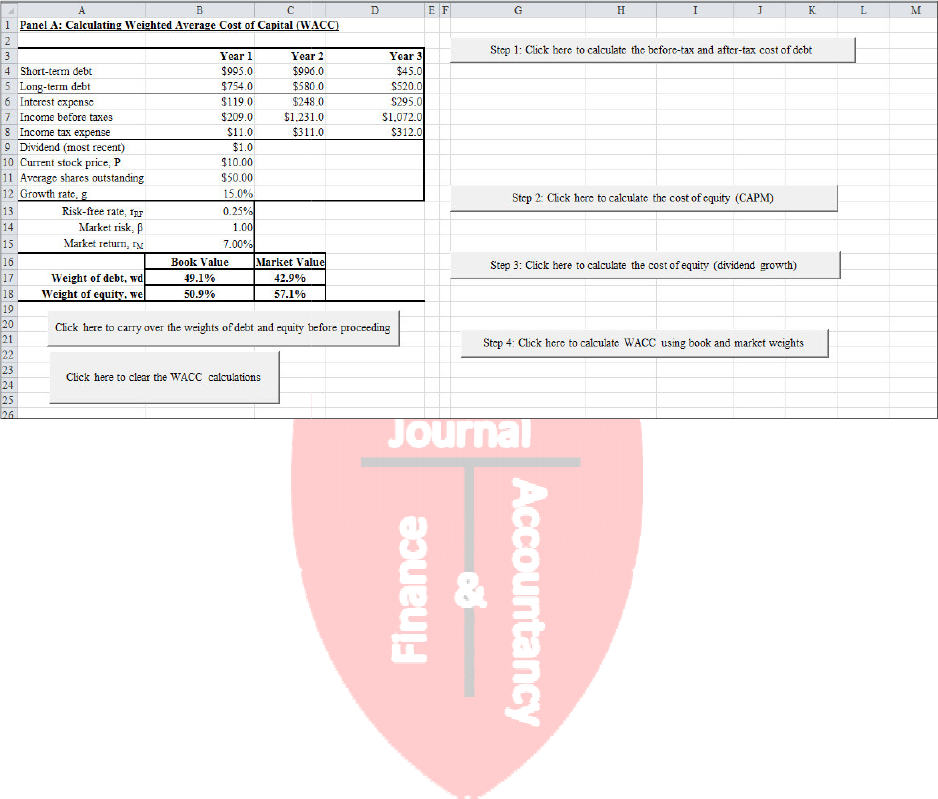

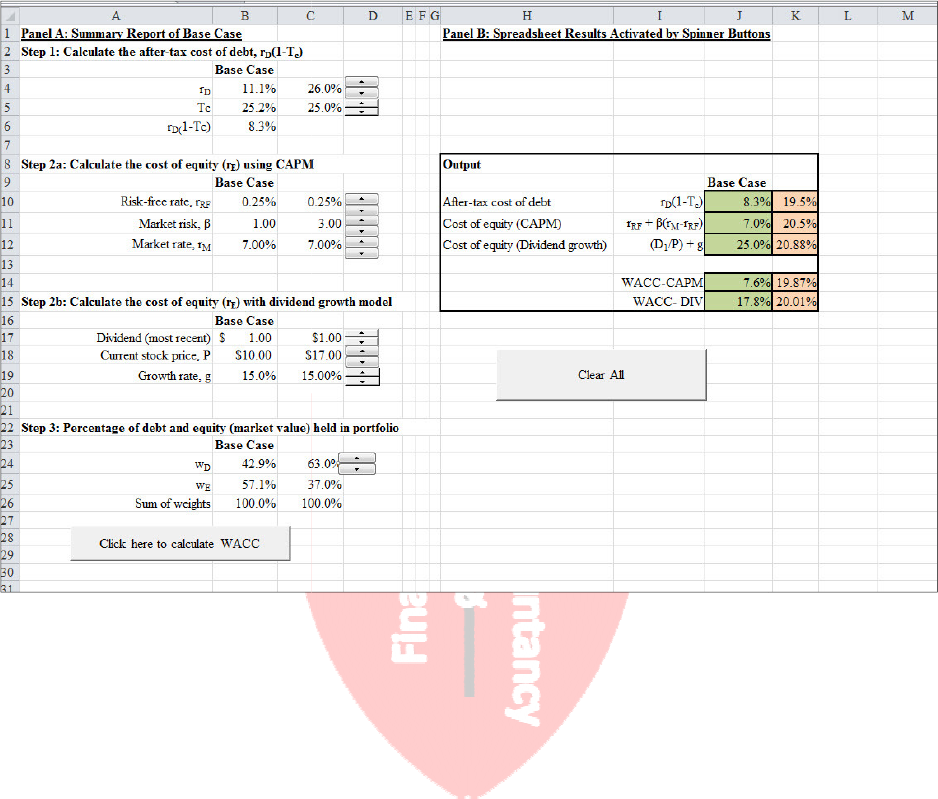

The spreadsheet consists of three exhibits

with the financial statement and market data that drive the WACC calculation. The exhibit

highlights the differences between book and market values since both valuations are used by

practitioners in the deter

mination of WACC (Truong, Partington, & Peat, 2008). Exhibit 2A

builds on the previous exhibit by reflecting cost of debt on a pre

presenting the cost of equity under the CAPM and dividend

gives st

udents the opportunity, through the use of

that affect the cost of debt and the cost of equity under both the CAPM and DIV models.

Students can also modify the strategic mix of debt and equity. Further detail o

the exhibits follows:

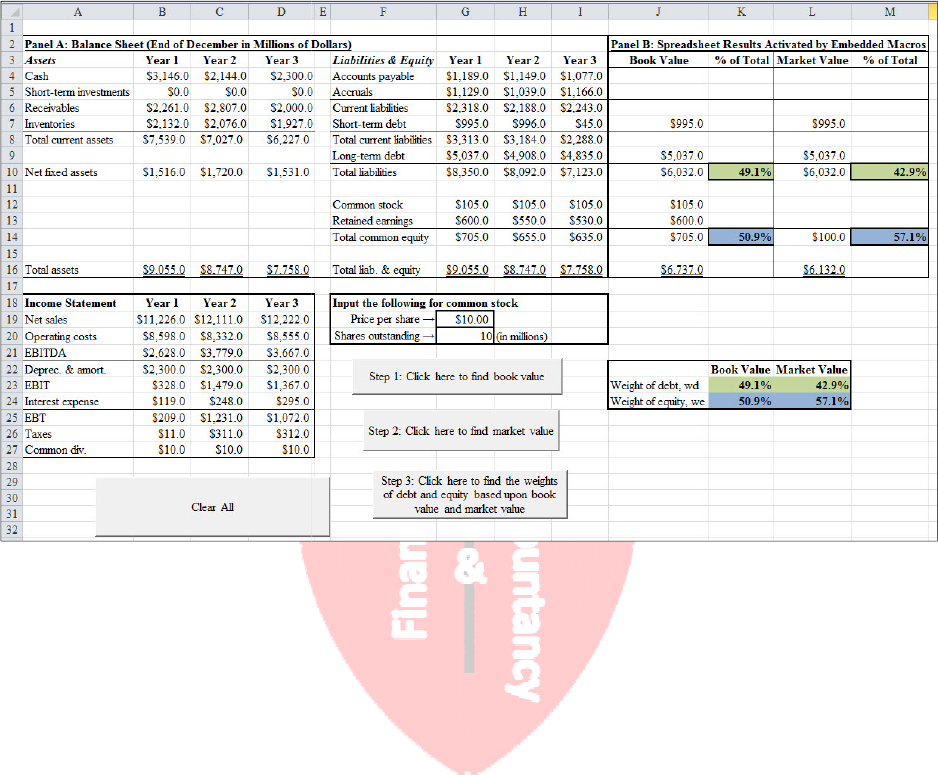

Exhibit 1A and Exhibit 1B: Weights of debt (w

As indicated in Exhibit 1A (Appendix), the spreadsheet contains financial statement

information with embedded macro buttons, prompting students to

weights and market value weights of debt and equity, respectively. As indicated in Exhibit 1B

(Appendix), the macro buttons trigger book value calculations, market value calculations, and a

summary table for w

D

and w

E,

respectively

students identify the source for each calculation. Within this first worksheet, all students have a

common starting point for WACC calculations as they tie WACC back to financial statement

analysis. Instr

uctors may wish to prompt students to consider how a change in a firm’s stock

price or the number of shares outstanding impacts w

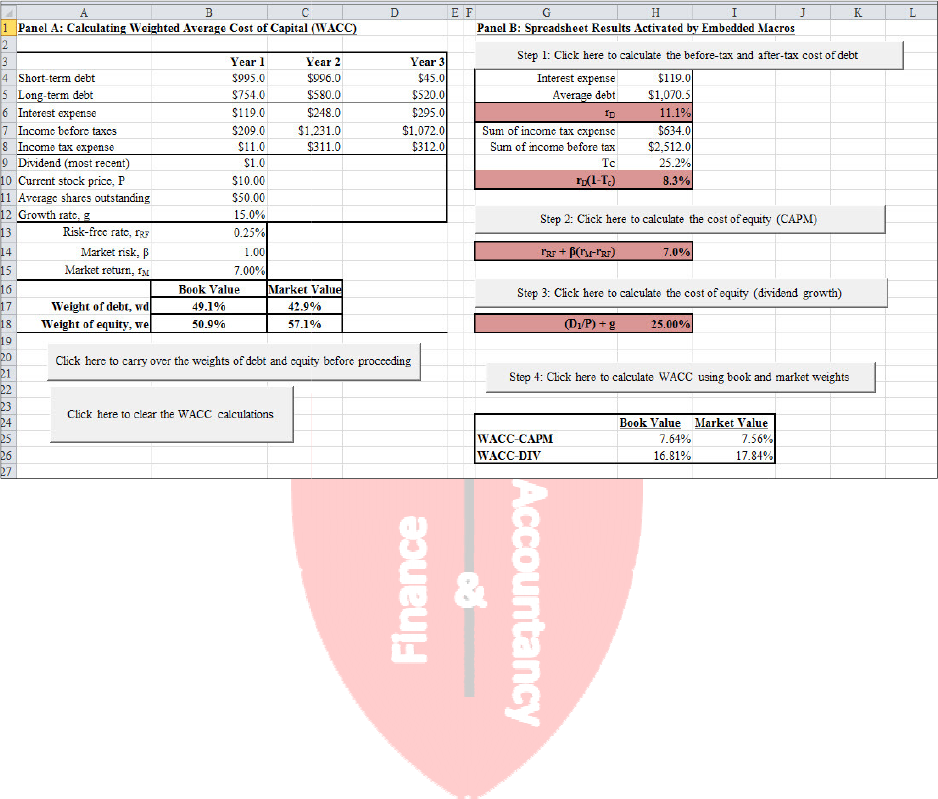

Exhibit 2A and Exhibit 2B: The cost of debt (r

As indicated in Exhibit 2A (Appendix),

relevant financial statement information from the first worksheet (see Exhibits 1A and 1B) to the

second worksheet. The summary schedule presented in Exhibit 2A reminds students of the

importance of interes

t expense, dividends, and other key financial statement items necessary for

completing the WACC calculation. As students begin to click the sequence of macro buttons,

they can track the calculations for r

When students ac

tivate the r

visualize the importance of average debt, income tax expense, and income (before taxes) in

deriving r

D

(Morrison Analytics, 20

methods for calculating r

E

. As students click the final macro button, the spreadsheet reveals a

summary table for WACC using both the CAPM method (WACC

growth model (WACC-

DIV). Students can identify how the method used to derive r

WACC.

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

calculation of WACC by incorporating

spinner buttons (“spinners”)

. These buttons allow

in

one or more variables within the WACC equation impact the

ion of WACC. Because students do not need to perform calculations or

gather information, they are able to focus on expanding their knowledge of the WACC formula

and recognizing several factors that influence WACC.

The spreadsheet consists of three exhibits

. Exhibit 1A allows students to become familiar

with the financial statement and market data that drive the WACC calculation. The exhibit

highlights the differences between book and market values since both valuations are used by

mination of WACC (Truong, Partington, & Peat, 2008). Exhibit 2A

builds on the previous exhibit by reflecting cost of debt on a pre

-tax and post-

tax basis and

presenting the cost of equity under the CAPM and dividend

-

growth (DIV) models. Exhibit 3A

udents the opportunity, through the use of

spinners

, to make changes to the base factors

that affect the cost of debt and the cost of equity under both the CAPM and DIV models.

Students can also modify the strategic mix of debt and equity. Further detail o

n the features of

Exhibit 1A and Exhibit 1B: Weights of debt (w

D

) and equity (w

E

)

As indicated in Exhibit 1A (Appendix), the spreadsheet contains financial statement

information with embedded macro buttons, prompting students to

calculate the book value

weights and market value weights of debt and equity, respectively. As indicated in Exhibit 1B

(Appendix), the macro buttons trigger book value calculations, market value calculations, and a

respectively

. The color-

coded cells within the spreadsheet help

students identify the source for each calculation. Within this first worksheet, all students have a

common starting point for WACC calculations as they tie WACC back to financial statement

uctors may wish to prompt students to consider how a change in a firm’s stock

price or the number of shares outstanding impacts w

D

and w

E

.

Exhibit 2A and Exhibit 2B: The cost of debt (r

D

) and the cost of equity (r

E

)

As indicated in Exhibit 2A (Appendix),

students click a control button to carry forward

relevant financial statement information from the first worksheet (see Exhibits 1A and 1B) to the

second worksheet. The summary schedule presented in Exhibit 2A reminds students of the

t expense, dividends, and other key financial statement items necessary for

completing the WACC calculation. As students begin to click the sequence of macro buttons,

they can track the calculations for r

D

, r

E,

and WACC (see Exhibit 2B).

tivate the r

D

calculation via the embedded macro button, they can

visualize the importance of average debt, income tax expense, and income (before taxes) in

(Morrison Analytics, 20

12). Also

, Exhibit 2B presents students with two different

. As students click the final macro button, the spreadsheet reveals a

summary table for WACC using both the CAPM method (WACC

-

CAPM) and the dividend

DIV). Students can identify how the method used to derive r

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

5

. These buttons allow

one or more variables within the WACC equation impact the

ion of WACC. Because students do not need to perform calculations or

gather information, they are able to focus on expanding their knowledge of the WACC formula

. Exhibit 1A allows students to become familiar

with the financial statement and market data that drive the WACC calculation. The exhibit

highlights the differences between book and market values since both valuations are used by

mination of WACC (Truong, Partington, & Peat, 2008). Exhibit 2A

tax basis and

growth (DIV) models. Exhibit 3A

, to make changes to the base factors

that affect the cost of debt and the cost of equity under both the CAPM and DIV models.

n the features of

As indicated in Exhibit 1A (Appendix), the spreadsheet contains financial statement

calculate the book value

weights and market value weights of debt and equity, respectively. As indicated in Exhibit 1B

(Appendix), the macro buttons trigger book value calculations, market value calculations, and a

coded cells within the spreadsheet help

students identify the source for each calculation. Within this first worksheet, all students have a

common starting point for WACC calculations as they tie WACC back to financial statement

uctors may wish to prompt students to consider how a change in a firm’s stock

students click a control button to carry forward

relevant financial statement information from the first worksheet (see Exhibits 1A and 1B) to the

second worksheet. The summary schedule presented in Exhibit 2A reminds students of the

t expense, dividends, and other key financial statement items necessary for

completing the WACC calculation. As students begin to click the sequence of macro buttons,

calculation via the embedded macro button, they can

visualize the importance of average debt, income tax expense, and income (before taxes) in

, Exhibit 2B presents students with two different

. As students click the final macro button, the spreadsheet reveals a

CAPM) and the dividend

DIV). Students can identify how the method used to derive r

E

impacts

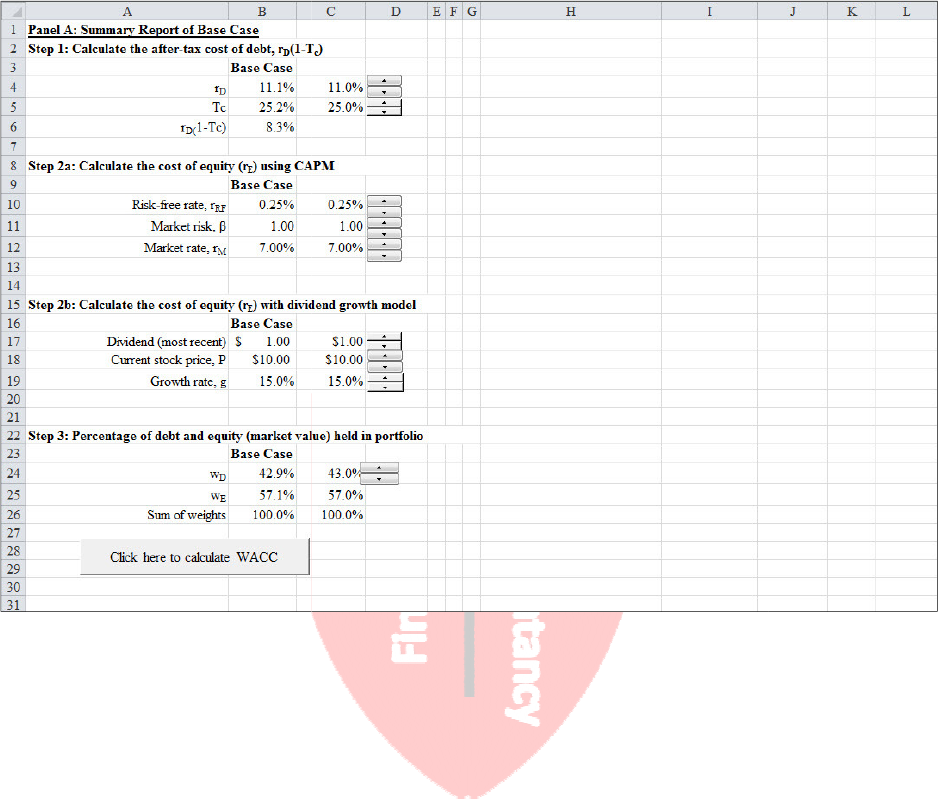

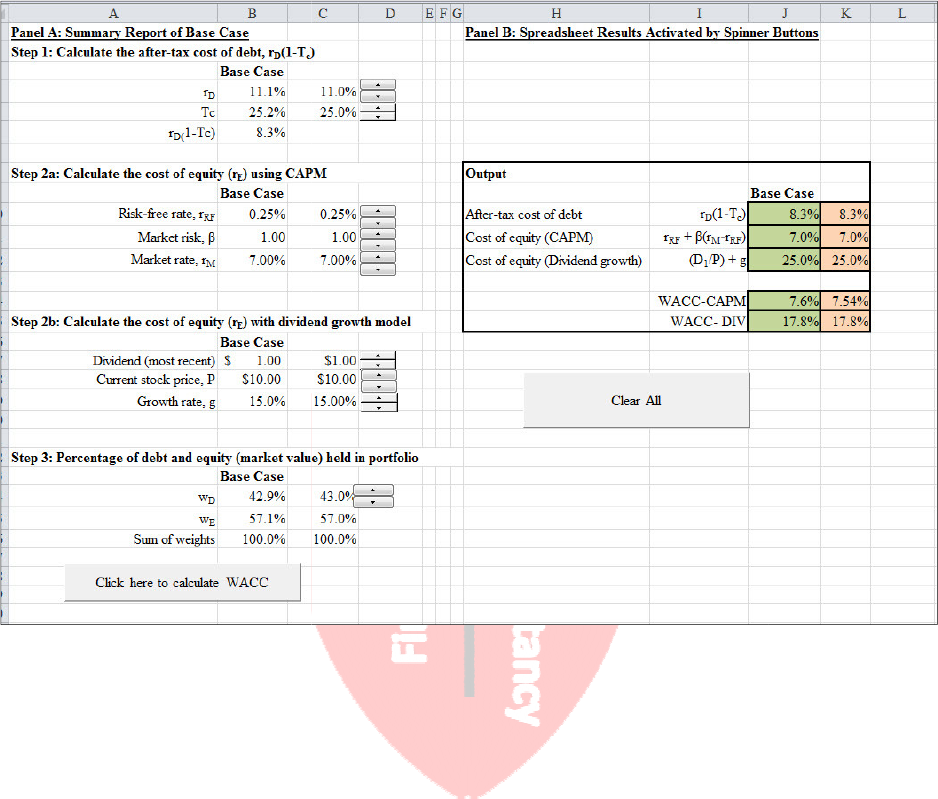

Exhibit 3A and Exhibit 3B: Computing variations to WACC (w

As indicated in Exhibit 3A (Appendix), students click a control button to carry forward r

and r

E

from the second worksheet and redisplay the WACC calculations. The starting point for

the spinners

aligns the original inputs and the solutions from Exhibit 2B. Students

recognize that the WACC calculation they explored through the previous

WACC calculation derived via the spinners. Next, students use the

changes in one or more variables impact the output. Initially, the

presented in earlier exhibits. Using the

in the tax rate leads to an increase in r

company’s beta leads to an increase in r

note that a

change in dividends would only impact WACC

the “clear all” button to return to the summary table of results.

OPPORTUNITIES IN TEACHING WACC

Krishnan, et al. (1999) considered the scope of material available for the

finance class and suggested it “would be impossible to do justice to all topics in a one

course” (p. 80) and recommended “keeping coverage practical and simple” (p. 81). According to

Parrott (2009), WACC appears to be a straightforwa

limit coverage through a streamlined approach. However, the WACC equation plays a pivotal

role in the introductory course and detailed coverage of the topic through an interactive

spreadsheet serves several purpos

Create a bridge between introductory finance topics

Highlighting WACC serves as a bridge between multiple topics within the course.

Faculty will have covered TVM early in the introductory course, and a study of WACC

reinforces its central role for d

iscounting cash flows. In TVM analysis, students learned how to

use the present value tool to assess projects. Students can now learn how and why WACC

represents an appropriate discount rate. Later in the course, faculty typically cover capital

budgeting t

hrough which students learn to calculate net present value (NPV) under various

scenarios. By understanding what drives changes in WACC, students begin to appreciate the

effect on NPV. The WACC formula also reinforces the dividend growth model developed in

finance course’s stock valuation material. If faculty decide to engage students in a review of

capital structure theory, knowledge of WACC supports their understanding of operating income

(EBIT), interest expense, and leverage.

Students appreciate “bo

undary

Instructors could choose to briefly discuss applications of WACC in other fields, such as the

mutual insurance industry (Adelman & Cross, 2005) or the hospitality industry (Jung, 2007).

This may prom

ote relevance to the general business major. Instructors can expose students to

excerpts from Fama and French (

which identify how practitioners apply WACC to solve business problems. From the Truong

al. survey, students learn that WACC is “widely used” (p. 98) as a discount rate. They also learn

that 60% of practitioners use expected weightings of debt and equity to calculate WACC, 51%

use the market value of financial instruments, and 69% adjust f

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

Exhibit 3A and Exhibit 3B: Computing variations to WACC (w

D

r

D

(1-

t) + w

As indicated in Exhibit 3A (Appendix), students click a control button to carry forward r

from the second worksheet and redisplay the WACC calculations. The starting point for

aligns the original inputs and the solutions from Exhibit 2B. Students

recognize that the WACC calculation they explored through the previous

worksheet matches the

WACC calculation derived via the spinners. Next, students use the

spinners

to identify how

changes in one or more variables impact the output. Initially, the

spinners

reflect the base case as

presented in earlier exhibits. Using the

spinners, students can observe,

for example, that a decline

in the tax rate leads to an increase in r

D

and an increase in WACC, or that an increase in a

company’s beta leads to an increase in r

E

and an increase in WACC. In addition, students may

change in dividends would only impact WACC

-

DIV. At any point, students can click

the “clear all” button to return to the summary table of results.

OPPORTUNITIES IN TEACHING WACC

Krishnan, et al. (1999) considered the scope of material available for the

finance class and suggested it “would be impossible to do justice to all topics in a one

course” (p. 80) and recommended “keeping coverage practical and simple” (p. 81). According to

Parrott (2009), WACC appears to be a straightforwa

rd concept and faculty might be tempted to

limit coverage through a streamlined approach. However, the WACC equation plays a pivotal

role in the introductory course and detailed coverage of the topic through an interactive

spreadsheet serves several purpos

es.

Create a bridge between introductory finance topics

Highlighting WACC serves as a bridge between multiple topics within the course.

Faculty will have covered TVM early in the introductory course, and a study of WACC

iscounting cash flows. In TVM analysis, students learned how to

use the present value tool to assess projects. Students can now learn how and why WACC

represents an appropriate discount rate. Later in the course, faculty typically cover capital

hrough which students learn to calculate net present value (NPV) under various

scenarios. By understanding what drives changes in WACC, students begin to appreciate the

effect on NPV. The WACC formula also reinforces the dividend growth model developed in

finance course’s stock valuation material. If faculty decide to engage students in a review of

capital structure theory, knowledge of WACC supports their understanding of operating income

(EBIT), interest expense, and leverage.

undary

-

spanning business thinking” (AACSB, 2002, p. 20).

Instructors could choose to briefly discuss applications of WACC in other fields, such as the

mutual insurance industry (Adelman & Cross, 2005) or the hospitality industry (Jung, 2007).

ote relevance to the general business major. Instructors can expose students to

excerpts from Fama and French (

1992

) and a study by Truong, Partington, and Peat (2008)

which identify how practitioners apply WACC to solve business problems. From the Truong

al. survey, students learn that WACC is “widely used” (p. 98) as a discount rate. They also learn

that 60% of practitioners use expected weightings of debt and equity to calculate WACC, 51%

use the market value of financial instruments, and 69% adjust f

or the interest rate shield on debt.

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

6

t) + w

E

r

E

)

As indicated in Exhibit 3A (Appendix), students click a control button to carry forward r

D

from the second worksheet and redisplay the WACC calculations. The starting point for

aligns the original inputs and the solutions from Exhibit 2B. Students

should readily

worksheet matches the

to identify how

reflect the base case as

for example, that a decline

and an increase in WACC, or that an increase in a

and an increase in WACC. In addition, students may

DIV. At any point, students can click

introductory

finance class and suggested it “would be impossible to do justice to all topics in a one

-semester

course” (p. 80) and recommended “keeping coverage practical and simple” (p. 81). According to

rd concept and faculty might be tempted to

limit coverage through a streamlined approach. However, the WACC equation plays a pivotal

role in the introductory course and detailed coverage of the topic through an interactive

Highlighting WACC serves as a bridge between multiple topics within the course.

Faculty will have covered TVM early in the introductory course, and a study of WACC

iscounting cash flows. In TVM analysis, students learned how to

use the present value tool to assess projects. Students can now learn how and why WACC

represents an appropriate discount rate. Later in the course, faculty typically cover capital

hrough which students learn to calculate net present value (NPV) under various

scenarios. By understanding what drives changes in WACC, students begin to appreciate the

effect on NPV. The WACC formula also reinforces the dividend growth model developed in

the

finance course’s stock valuation material. If faculty decide to engage students in a review of

capital structure theory, knowledge of WACC supports their understanding of operating income

spanning business thinking” (AACSB, 2002, p. 20).

Instructors could choose to briefly discuss applications of WACC in other fields, such as the

mutual insurance industry (Adelman & Cross, 2005) or the hospitality industry (Jung, 2007).

ote relevance to the general business major. Instructors can expose students to

) and a study by Truong, Partington, and Peat (2008)

which identify how practitioners apply WACC to solve business problems. From the Truong

et

al. survey, students learn that WACC is “widely used” (p. 98) as a discount rate. They also learn

that 60% of practitioners use expected weightings of debt and equity to calculate WACC, 51%

or the interest rate shield on debt.

Finally, instructors can emphasize the role of CAPM within the WACC equation and how

academics

struggle to derive a good estimate for the market rate of return (Rogers, 2009).

Brigham (as cited in Gup, 1994) stated stud

does not produce neat, precise answers” (p. 108). Carrithers, Lin

against well-

structured problems with right answers and instead advocated ill

“messy” problems that te

ach critical thinking skills. Given the breadth of cost of capital

applications by practitioners, students benefit by exploring a full range of concepts rather than

solving for a single solution to WACC.

Clarify the importance of the discount rate

Intro

ductory finance textbooks typically provide the rate used to discount cash flows

within TVM and capital budgeting problems. After performing numerous present value

calculations, students might be left with the impression that the associated discount rate i

given or that a single, “correct” rate exists. Exploring WACC provides instructors with an

opportunity to clarify the importance of discount rates and present the detail embedded in the

WACC formula. Similarly, exploring WACC allows students to c

discounting with a financial manager’s debt

Highlight financial relationships

Coverage of the WACC formula gives instructors the opportunity to (1) introduce

students to balance sheet and income statement information, (2) highlight differences between

book and market values, and (3) illustrate how managers extract relevant data from

statements for decision-

making purposes.

THE ASSIGNMENT

By emphasizing the relationship between financial statement items and WACC, this

assignment forces a student to assume the role of a financial manager and consider how a change

in various

factors might impact WACC. Because the spreadsheet reveals calculations in a step

by-

step fashion, students can spend time reflecting on the significance of their findings rather

than becoming frustrated or lost in a myriad of calculations.

The assignment

consists of two sections. In the first section, students begin with a

WACC-

CAPM of approximately 8% (i.e., the base case) and use

increases and decreases in CAPM variables impact WACC. In the second section, students begin

with a WACC-

DIV of approximately

dividend growth model variables impact WACC. To complete the assignment, students prepare a

written report on their findings. The instructor can also fol

student results. The specific assignment steps are presented below:

Section I: Calculating WACC using CAPM (WACC

1.

The CFO anticipates that WACC (based upon the CAPM method) will increase from the

rate presented in the base case (approxima

Factors which may impact WACC

a.

The cost of debt (r

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

Finally, instructors can emphasize the role of CAPM within the WACC equation and how

struggle to derive a good estimate for the market rate of return (Rogers, 2009).

Brigham (as cited in Gup, 1994) stated stud

ents must understand “the CAPM in the real world

does not produce neat, precise answers” (p. 108). Carrithers, Lin

g

, and Bean (2008) argued

structured problems with right answers and instead advocated ill

-

structured or

ach critical thinking skills. Given the breadth of cost of capital

applications by practitioners, students benefit by exploring a full range of concepts rather than

solving for a single solution to WACC.

Clarify the importance of the discount rate

ductory finance textbooks typically provide the rate used to discount cash flows

within TVM and capital budgeting problems. After performing numerous present value

calculations, students might be left with the impression that the associated discount rate i

given or that a single, “correct” rate exists. Exploring WACC provides instructors with an

opportunity to clarify the importance of discount rates and present the detail embedded in the

WACC formula. Similarly, exploring WACC allows students to c

onnect the rate used for

discounting with a financial manager’s debt

-equity decisions.

Highlight financial relationships

Coverage of the WACC formula gives instructors the opportunity to (1) introduce

students to balance sheet and income statement information, (2) highlight differences between

book and market values, and (3) illustrate how managers extract relevant data from

making purposes.

By emphasizing the relationship between financial statement items and WACC, this

assignment forces a student to assume the role of a financial manager and consider how a change

factors might impact WACC. Because the spreadsheet reveals calculations in a step

step fashion, students can spend time reflecting on the significance of their findings rather

than becoming frustrated or lost in a myriad of calculations.

consists of two sections. In the first section, students begin with a

CAPM of approximately 8% (i.e., the base case) and use

spinners

to explore how

increases and decreases in CAPM variables impact WACC. In the second section, students begin

DIV of approximately

8% and again use spinners

to explore how changes in

dividend growth model variables impact WACC. To complete the assignment, students prepare a

written report on their findings. The instructor can also fol

low

up with a classroom di

student results. The specific assignment steps are presented below:

Section I: Calculating WACC using CAPM (WACC

-CAPM)

The CFO anticipates that WACC (based upon the CAPM method) will increase from the

rate presented in the base case (approxima

tely 8%) to approximately 20% next year.

Factors which may impact WACC

-CAPM next year include:

The cost of debt (r

D

)

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

7

Finally, instructors can emphasize the role of CAPM within the WACC equation and how

struggle to derive a good estimate for the market rate of return (Rogers, 2009).

ents must understand “the CAPM in the real world

, and Bean (2008) argued

structured or

ach critical thinking skills. Given the breadth of cost of capital

applications by practitioners, students benefit by exploring a full range of concepts rather than

ductory finance textbooks typically provide the rate used to discount cash flows

within TVM and capital budgeting problems. After performing numerous present value

calculations, students might be left with the impression that the associated discount rate i

s always

given or that a single, “correct” rate exists. Exploring WACC provides instructors with an

opportunity to clarify the importance of discount rates and present the detail embedded in the

onnect the rate used for

Coverage of the WACC formula gives instructors the opportunity to (1) introduce

students to balance sheet and income statement information, (2) highlight differences between

book and market values, and (3) illustrate how managers extract relevant data from

financial

By emphasizing the relationship between financial statement items and WACC, this

assignment forces a student to assume the role of a financial manager and consider how a change

factors might impact WACC. Because the spreadsheet reveals calculations in a step

-

step fashion, students can spend time reflecting on the significance of their findings rather

consists of two sections. In the first section, students begin with a

to explore how

increases and decreases in CAPM variables impact WACC. In the second section, students begin

to explore how changes in

dividend growth model variables impact WACC. To complete the assignment, students prepare a

up with a classroom di

scussion of

The CFO anticipates that WACC (based upon the CAPM method) will increase from the

tely 8%) to approximately 20% next year.

b.

The corporate tax rate (T

c. The risk-

free rate (r

d.

The market risk (β

e.

The market rate of return (r

Using spinners

, adjust each of the

they impact WACC-

CAPM.

2.

Returning to the base case with the “Clear All” button, minimize and maximize one of

the aforementioned factors and comment on the effect of that variable on WACC

3. Returning to

the base case, minimize and maximize a different factor. Comment on the

sensitivity of that variable on WACC

Section II: Calculating WACC using the dividend growth model (WACC

1.

The CFO anticipates that WACC (based upon the dividend growth

from the rate presented i

n the base case (approximately

year. Factors which may impact WACC

a.

The cost of debt (r

b.

The corporate tax rate (T

c. The dividend rate

d.

Current stock pric

e.

Growth rate in dividends (g)

Using spinners

, adjust each of the aforementioned factors and briefly comment on how

they impact WACC-

DIV.

2.

Returning to the base case with the “Clear All” button, minimize and maximize one of

the aforementioned factors a

Returning to the base case, minimize and maximize a different factor. Comment on the

sensitivity of that variable on WACC

SAMPLE STUDENT RESULTS

To assess student understanding of WACC, the ins

students within a small introductory finance class. Prior to its distribution, the instructor

motivated students by dedicating class time to the importance of the discount rate within the

bond and stock valuation mode

ls developed earlier in the course. In addition, the instructor

emphasized the importance of WACC to future topics such as capital budgeting, cash flow and

risk analysis, and valuation-

based management models (i.e., adjusted present valuation

techniques).

The students were provided one week to complete the assignment. The student

deliverables included electronic submittal of spreadsheet results to the instructor and a brief

narrative of their findings.

Student commentaries signaled a level of discomfort wit

students correctly identified which factors directly (e.g., r

impacted WACC, the typical student response only highlighted numerical relationships (e.g., if

r

M

increased by 1%, then WACC

sample student results.

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

The corporate tax rate (T

C

)

free rate (r

RF

)

The market risk (β)

The market rate of return (r

M

)

, adjust each of the

aforementioned factors and briefly comment on how

CAPM.

Returning to the base case with the “Clear All” button, minimize and maximize one of

the aforementioned factors and comment on the effect of that variable on WACC

the base case, minimize and maximize a different factor. Comment on the

sensitivity of that variable on WACC

-CAPM.

Section II: Calculating WACC using the dividend growth model (WACC

-

DIV)

The CFO anticipates that WACC (based upon the dividend growth

model) will increase

n the base case (approximately

8%) to approximately 20% next

year. Factors which may impact WACC

-DIV next year may include:

The cost of debt (r

D

)

The corporate tax rate (T

C

)

Current stock pric

e (P)

Growth rate in dividends (g)

, adjust each of the aforementioned factors and briefly comment on how

DIV.

Returning to the base case with the “Clear All” button, minimize and maximize one of

the aforementioned factors a

nd comment on the effect of that variable on WACC

Returning to the base case, minimize and maximize a different factor. Comment on the

sensitivity of that variable on WACC

-DIV.

SAMPLE STUDENT RESULTS

To assess student understanding of WACC, the ins

tructor distributed the spreadsheet to

students within a small introductory finance class. Prior to its distribution, the instructor

motivated students by dedicating class time to the importance of the discount rate within the

ls developed earlier in the course. In addition, the instructor

emphasized the importance of WACC to future topics such as capital budgeting, cash flow and

based management models (i.e., adjusted present valuation

The students were provided one week to complete the assignment. The student

deliverables included electronic submittal of spreadsheet results to the instructor and a brief

Student commentaries signaled a level of discomfort wit

h WACC concepts.

students correctly identified which factors directly (e.g., r

M

) and inversely (e.g., stock prices)

impacted WACC, the typical student response only highlighted numerical relationships (e.g., if

increased by 1%, then WACC

-CAPM increased by 0.5%).

Exhibit 4 (Appendix) presents

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

8

aforementioned factors and briefly comment on how

Returning to the base case with the “Clear All” button, minimize and maximize one of

the aforementioned factors and comment on the effect of that variable on WACC

-CAPM.

the base case, minimize and maximize a different factor. Comment on the

DIV)

model) will increase

8%) to approximately 20% next

, adjust each of the aforementioned factors and briefly comment on how

Returning to the base case with the “Clear All” button, minimize and maximize one of

nd comment on the effect of that variable on WACC

-DIV.

Returning to the base case, minimize and maximize a different factor. Comment on the

tructor distributed the spreadsheet to

students within a small introductory finance class. Prior to its distribution, the instructor

motivated students by dedicating class time to the importance of the discount rate within the

ls developed earlier in the course. In addition, the instructor

emphasized the importance of WACC to future topics such as capital budgeting, cash flow and

based management models (i.e., adjusted present valuation

The students were provided one week to complete the assignment. The student

deliverables included electronic submittal of spreadsheet results to the instructor and a brief

h WACC concepts.

Although

) and inversely (e.g., stock prices)

impacted WACC, the typical student response only highlighted numerical relationships (e.g., if

Exhibit 4 (Appendix) presents

Section I: Student Results

(WACC

Student results suggested proficiency in adjusting CAPM variables to achieve an increase

in WACC from roughly 8% to 20%. Students noted the

cost of debt calculation. More specifically, many recognized interest expense is tax deductible on

bonds and that as the tax rate increases, debt becomes less costly, and WACC

Using the spinners, student

adjustments. One student noted that r

find in the market, usually expressed as the return on Treasury bonds.”

t

he student suggested Treasury rates set the economy’s floor for interest rates and that changes

do not necessarily change the market risk premium. He

firms reduce spending. This, in turn, will lower

premium stable.

A third student noted that a “high” beta (greater than 1.0) implies a firm’s stock adds

more risk to a well-

diversified portfolio. The student noted the higher the beta, the higher the

required return for inve

stors, leading to a higher WACC

When describing WACC

-

abstract theory presented in the chapter preceding WACC. Students gained insight into how

CAPM could be used by analysts and how changing the i

For example, Brigham and Houston (2013) indicated that the value used to represent r

a significant effect on the calculated beta.

Section II: Student Results

(WACC

Regarding WACC-

DIV, students recognized

increase dividends leads to a higher cost of equity. Students also recognized that a higher stock

price implied that the dividend yield (D

pressure on WACC-DIV.

When students attempted to minimize and maximize variables simultaneously, their

comments reinforced their lack of comfort with the WACC equation. Exploring WACC through

an interactive worksheet provided students with a view of its complexities. Students

that if a financial manager increases the proportion of debt, then the weight of low

increases and the weight of high

-

the assignment and asked for student feedback, stu

changing the capital structure impacts all variables in the WACC equation.

Student Review

After distributing results to the students, the instructor asked them to participate in a 15

minute discussion about the

assignment before proceeding to capital budgeting. Students

observed that while the WACC formula is fairly straightforward, the spreadsheet provoked them

to comment on relationships between key components and WACC. One student commented,

“This spreadsheet

forces a student to think like a financial manager and what happens to WACC

if a recession occurs and r

M

falls.” Another student indicated that instead of busily solving

equations via Excel or a financial calculator, he gained an appreciation for complicat

capital issues that managers might face in the boardroom.

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

(WACC

-CAPM)

Student results suggested proficiency in adjusting CAPM variables to achieve an increase

in WACC from roughly 8% to 20%. Students noted the

tax rate plays a fundamental role in the

cost of debt calculation. More specifically, many recognized interest expense is tax deductible on

bonds and that as the tax rate increases, debt becomes less costly, and WACC

-

CAPM falls.

Using the spinners, student

s noticed little change in WACC due to risk-

free rate (r

adjustments. One student noted that r

RF

reflects the return on “the least risky investment one can

find in the market, usually expressed as the return on Treasury bonds.”

Within his commentary,

he student suggested Treasury rates set the economy’s floor for interest rates and that changes

do not necessarily change the market risk premium. He

further

suggested that during a recession,

firms reduce spending. This, in turn, will lower

r

RF

and r

M

tog

ether, keeping the market risk

A third student noted that a “high” beta (greater than 1.0) implies a firm’s stock adds

diversified portfolio. The student noted the higher the beta, the higher the

stors, leading to a higher WACC

-CAPM.

-

CAPM, students recognized that CAPM is more than just

abstract theory presented in the chapter preceding WACC. Students gained insight into how

CAPM could be used by analysts and how changing the i

nputs impact the WACC calculation.

For example, Brigham and Houston (2013) indicated that the value used to represent r

a significant effect on the calculated beta.

(WACC

-DIV)

DIV, students recognized

that a financial manager’s decision to

increase dividends leads to a higher cost of equity. Students also recognized that a higher stock

price implied that the dividend yield (D

1

/P) would fall, everything else equal, placing downward

When students attempted to minimize and maximize variables simultaneously, their

comments reinforced their lack of comfort with the WACC equation. Exploring WACC through

an interactive worksheet provided students with a view of its complexities. Students

that if a financial manager increases the proportion of debt, then the weight of low

-

cost equity (w

E

) falls. However, after the instructor collected

the assignment and asked for student feedback, stu

dents were tentative in acknowledging that

changing the capital structure impacts all variables in the WACC equation.

After distributing results to the students, the instructor asked them to participate in a 15

assignment before proceeding to capital budgeting. Students

observed that while the WACC formula is fairly straightforward, the spreadsheet provoked them

to comment on relationships between key components and WACC. One student commented,

forces a student to think like a financial manager and what happens to WACC

falls.” Another student indicated that instead of busily solving

equations via Excel or a financial calculator, he gained an appreciation for complicat

capital issues that managers might face in the boardroom.

Journal of Finance and Accountancy

An Interactive Approach, Page

9

Student results suggested proficiency in adjusting CAPM variables to achieve an increase

tax rate plays a fundamental role in the

cost of debt calculation. More specifically, many recognized interest expense is tax deductible on

CAPM falls.

free rate (r

RF

)

reflects the return on “the least risky investment one can

Within his commentary,

he student suggested Treasury rates set the economy’s floor for interest rates and that changes

suggested that during a recession,

ether, keeping the market risk

A third student noted that a “high” beta (greater than 1.0) implies a firm’s stock adds

diversified portfolio. The student noted the higher the beta, the higher the

CAPM, students recognized that CAPM is more than just

abstract theory presented in the chapter preceding WACC. Students gained insight into how

nputs impact the WACC calculation.

For example, Brigham and Houston (2013) indicated that the value used to represent r

M

can have

that a financial manager’s decision to

increase dividends leads to a higher cost of equity. Students also recognized that a higher stock

/P) would fall, everything else equal, placing downward

When students attempted to minimize and maximize variables simultaneously, their

comments reinforced their lack of comfort with the WACC equation. Exploring WACC through

an interactive worksheet provided students with a view of its complexities. Students

surmised

that if a financial manager increases the proportion of debt, then the weight of low

-cost debt (w

D

)

) falls. However, after the instructor collected

dents were tentative in acknowledging that

After distributing results to the students, the instructor asked them to participate in a 15

-

assignment before proceeding to capital budgeting. Students

observed that while the WACC formula is fairly straightforward, the spreadsheet provoked them

to comment on relationships between key components and WACC. One student commented,

forces a student to think like a financial manager and what happens to WACC

falls.” Another student indicated that instead of busily solving

equations via Excel or a financial calculator, he gained an appreciation for complicat

ed cost of

During this exercise, students recognized that the cost of capital is affected by factors that

are outside of

a firm’s control. These include stock prices, the market risk premium, and t

set by Congress (Brigham & Houston, 2013). Students also recog

control over

internal factors such as

CONCLUSION

AND FUTURE RECOMMENDATIONS

Hamilton and Saunders (2009)

level appropriate to a university’s curriculum and course objectives. Such activities should assist

students in developing the decision

in t

he learning (and application) of finance concepts regardless of a student’s major. Through an

interactive, exploratory process, this assignment represents a step in that direction. In the

assignment, an Excel spreadsheet serves as a “bridge” between the bo

chapters using TVM and chapters culminating the introductory course (e.g., capital budgeting,

cash flow estimation). The spreadsheet provides a sequential approach for calculating WACC

which is appropriate for the Net Gen student. Th

how incremental changes in various factors impact WACC. By deemphasizing WACC