Multinational Corporations and their Influence

Through Lobbying on Foreign Policy

∗

In Song Kim

†

Helen V. Milner

‡

December 2, 2019

Abstract

Multinational corporations (MNCs) play significant roles in shaping the global economy.

Despite the prevalence of the economic activities of MNCs across the globe, few studies exist that

examine their political influence on foreign policy-making. This chapter develops a theoretical

framework for understanding how MNCs’ unique positions in the market affect their political

activities. Specifically, we argue that MNCs’ economic dominance reduces the relative cost

of engaging in political activities, while their large-scale transnational activities increase the

marginal benefits of influencing policy-making individually. To examine this empirically, we first

introduce a novel dataset of lobbying in the US encompassing lobbying activities of all public

firms from 1999 to 2019. We then employ the difference-in-differences identification strategy

to estimate the effect of MNC status on lobbying. We find strong evidence for an increase in

lobbying expenditures when firms become multinational. Furthermore, we find that MNCs tend

to lobby on a more diverse set of foreign policy issues. Our findings suggest that MNCs are

important political actors whose distinct interests and influence should be incorporated into our

understanding of foreign policy-making.

Key words: multinational corporations (MNCs), firms, foreign policy, lobbying

∗

We thank Lukas Wolters and Dominic De Sapio for their excellent research assistance.

†

Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA,

‡

Professor, Department of Politics, Princeton University, Princeton NJ 08544. Email: [email protected],

URL: https://scholar.princeton.edu/hvmilner/home

1 Introduction

Multinational corporations (MNCs) play significant roles in shaping the global economy. For exam-

ple, MNCs in the U.S., which has the world’s largest economy, make disproportionate contributions

to the national economy: They represent a very small number of total American firms (less than

1%), but a large fraction of GDP, exports, imports, research and development, and private-sector

employee compensation; Specifically, U.S. MNC parent companies in 2016 constituted more than

24% of private sector GDP (value-added) and 26% of private-sector employee compensation (Bu-

reau of Economic Analysis 2018a); U.S. MNCs are engaged in more than half of all U.S. exports and

more than 40% of U.S. imports (Bureau of Economic Analysis 2018b). Likewise, MNCs throughout

the world dominate the global economy as well as their national economies. The OECD (2018)

estimates that MNCs account for half of global exports, nearly a third of world GDP (28%), and

about fourth of global employment. These firms all generate a significant share of their revenue from

abroad as well.

1

Importantly, their transnational activities have transformed the nature of interna-

tional trade, investments, and technology transfers in the era of globalization. The extensive global

value chains (GVCs) prevalent in today’s world economy have been driven by how MNCs structure

their global operations through outsourcing and offshoring activities. In fact, their decisions have

enormous implications for a wide range of policy issues—such as taxation, investment protection,

immigration—across many countries with different political and economic institutions. MNCs also

may have strong political influence domestically. Indeed, their global economic dominance may go

hand-in-hand with their powerful domestic political position.

Recent political developments bring multinational lobbying efforts into stark relief. Multina-

tional firms have vocally opposed the Trump Administration’s escalation of trade tensions, tighten-

ing of immigration restrictions, and disruption of global value chains. Intensive lobbying, however,

does not always equate with political power. While the Trump Administration has largely rebuffed

MNC’s efforts to preserve existing trade agreements, individual firms have lobbied successfully

to win tariff exemptions. In other policy domains such corporate taxation and the proposed

Destination-Based Cash Flow Tax, multinationals lobbied on both sides of the issue. Despite the

prevalence of the economic activities of MNCs across the globe, few studies exist that examine

their political influence on foreign policy-making.

In this regard, the main contribution of this chapter is to investigate MNCs’ distinct roles as

political actors. We focus mostly on the US and on one form of political activity, lobbying. We

try to address several general questions however. First, are MNCs different from other firms in

1

Manyika et al. (2018) calculated that the top 1% of firms with annual revenue greater than $1 billion dollars

source more than 42% of total sales from outside their home country.

2

their political activities? In particular, do the global connections of these firms lead them to have

distinct policy preferences from domestic firms? Second, do the political activities of MNCs differ

even from those of big domestic firms? Past research notes that big firms are different; they have

more political activity generally and usually do so more alone. Are MNCs just global versions of

these big firms? Third, do MNCs care about the same set of issues that all firms, or all big firms,

concentrate on? We address these questions by reviewing much past research and then providing

new empirical analyses.

We begin by pointing out MNCs’ unique economic characteristics compared to other firms that

compete primarily in domestic markets. In doing so, we relate our discussion to the theoretical

framework of heterogeneous firms in international economics to describe MNCs’ unique positions

in the global economy. Specifically, we discuss how MNCs’ engagement in international trade and

foreign investment affects their policy preferences. We show that MNCs policy preferences are

likely to differ greatly from those of purely domestic firms on issues related to foreign economic

policy. This implies that these firms will differ from domestic firms, even big ones, in the the issues

they care about most. And it means their positions on many issues will diverge from those of the

much more numerous domestic firms, who will be less likely to organize collectively for political

action. In addition, because of their size, global reach and leading role in the national economy,

they will have more means to affect politics and more reasons to do so.

The second contribution of this chapter is to empirically examine MNCs’ political activities

in the US. We introduce a new database of lobbying—LobbyView—to study MNCs’ engagement

in lobbying (Kim 2018). This database, based on the lobbying reports filed under the Lobbying

Disclosure Act of 1995, provides highly granular data on lobbying that scholars and practitioners

can use to evaluate special interest group politics. We merge this data with a firm-level finance

database to investigate whether MNCs exhibit different political activities compared to purely

domestic firms. To estimate the independent effect of the change in a firm’s status from domestic to

multinational, we employ a difference-in-differences identification strategy. Specifically, we compare

the difference in lobbying expenditure of firms that became multinational against those of domestic

firms that are similar in their size and previous lobbying activities. We find strong evidence for

an increase in lobbying expenditures when firms become multinational. Furthermore, we find that

MNCs tend to lobby on a more diverse set of foreign policy issues. To be sure, our study in

this chapter is limited to the US, recent years, and individual firm lobbying activity. However,

our findings lay an empirical foundation for future research of MNCs’ political activities across

various countries, in different periods, and their connections to lobbying through larger industry

associations.

3

In sum, MNCs are politically distinct as well as economically. They act politically in ways that

differ from domestic firms, and even from large domestic ones. Our findings suggest that MNCs are

important political actors whose distinct interests should be incorporated into our understanding

of foreign policy-making. While we cannot fully assess their political influence, we do note that

many of the policy positions they alone have championed have become US policy in recent decades

and indeed have helped create the globalized world economy that we live in today.

2 The Political Influence of Multinational Corporations

This section considers the roles that MNCs play in both economic and political marketplaces. To

begin, we discuss their unique economic characteristics compared to other firms that primarily

serve domestic market and how these differences will affect MNCs’ policy preferences. We then

discuss MNCs’ political activities in affecting foreign policy-making that have been documented by

many social scientists.

2.1 Firm-level Heterogeneity and the Policy Preferences of MNCs

A first step in understanding the political influence of multinational corporations (MNCs) is to

differentiate them from other firms.

2

In fact, there exists ample empirical evidence that MNCs

differ in a number of important ways from purely domestic firms: they tend to be large and highly

productive (e.g., Bernard, Jensen, and Schott 2009). They also tend to be the largest exporters, the

most integrated into GVCs, employers of the most high skilled workers, and the largest spenders

on R&D (Autor et al. 2017). This gives them a valuable position in any economy.

The uniqueness of MNCs has a close theoretical connection to the studies that examine firm-

level heterogeneity in their engagement in international trade. In earlier work, Bernard, Jensen,

and Lawrence (1995) show that exporters in manufacturing are very different than purely domestic

firms.

3

While exports from the US only account for about 12.2% of GDP, exporting firms overall

play a large role in the US economy. Exporting firms are larger, more productive, more capital

intensive; and they pay higher wages and employ many workers, especially the most productive

ones.

4

Bernard et al. (2007) point out that this evidence about exporting firms supports the new,

new trade theory and its focus on productivity differences among firms. As heterogeneous firm

models predict, these firms benefit from trade and its liberalization; they tend to grow bigger and

2

We define a MNC as a corporation that owns or controls production of goods or services in at least two countries.

Our definition stems from data availability using Compustat databases (see Section 3.1); other scholars use different

definitions, often ones that focus on the percentage of ownership for subsidiaries abroad which they obtain from the

the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)’s confidential databases.

3

Almost all MNCs export but not all exporters are MNCs.

4

Note that entry into and exit from exporting is frequent. That is, exporting today is no guarantee of success for

the firm in the future.

4

more productive while less productive firms exit the market. That is, a very small number of firms

within an economy dominate export markets and tend to export many different goods to many

other markets. Moreover, roughly half of the firms that export also import and thus are probably

part of global value chains (GVCs).

While not all importers or exporters are multinational firms, almost all MNCs export and/or

import (Yeaple 2009), accounting for over 80 percent of US trade (Bernard, Jensen, and Schott

2009). These MNCs sit atop the productivity ladder of all firms, being the largest, most capital and

skill intensive, and the most innovative (Tomiura 2007; Bernard, Jensen, and Schott 2009; Doms

and Jensen 1998; Slaughter 2004). Among MNCs, as theory implies, there exists variation in where

they invest and how much. A “pecking order” arises where only the most productive firms invest

in all types of foreign locations while the least productive firms invest in only the most productive

locations (Yeaple 2009). Although their numbers are small, they have a large presence within any

economy. And because of these characteristics, they have been viewed as powerful actors within

any country where they operate, whether their host or home one (Prakash and Potoski 2007; Luo

2001; Jensen et al. 2012).

A second important step is to identify the preferences of MNCs in terms of foreign policy overall,

and especially economic policies such as trade, foreign investment, immigration, and exchange rates.

To understand if firms have political influence, researchers have studied what they want (especially

ex ante) and whether it differs from what other groups want. In International Relations, for

example, a long standing question has been whether business favored war or peace. Indeed, the so

called security preferences of business have been an important issue from Karl Marx’s time onward,

and many scholars saw business or capitalism itself as a driver of war and conflict, especially

colonialism (Cohen 1973; Staley 1935). The claims about the “military-industrial complex” and

its benefits from war are part of this tradition. On the other hand, more recent research has cast

mostly doubt on this claim. In particular, Brooks (2005) argues that business firms in the modern

period are strong proponents of peace, not war. Building upon this, a literature now exists on

the capitalist peace, arguing the capitalism and its agents are central to peace among countries

(Gartzke 2007; Kirschner 2007; McDonald 2009).

Others have studied firm-level preferences regarding foreign economic policies, such as trade,

foreign investment, and immigration. In the trade area, it has long been recognized that firms will

have different preferences depending on their ties to the international economy. Domestic firms

that face import competition will opt for protectionism, while big exporters and multinationals

will want freer trade (Milner 1988; Gilligan 1997; Kim and Osgood 2019). The preferences for

freer trade at home and abroad are reinforced for multinationals if they are part of global value

5

chains. In more recent work, Jensen, Quinn, and Weymouth (2015) argue that MNCs in GVCs

should not use trade remedies like antidumping as much as domestic firms and that trade disputes

in their sectors should be less. In terms of foreign investment and financial markets, many of the

same divides are expected. Small domestic banks and firms should care most about protecting the

domestic market and keeping large foreign firms and banks out. Big banks and multinationals,

on the other hand, should press for open capital markets, protection for foreign investments, and

greater capital mobility (Frieden 1991). Recent work also links firms’ preferences to immigration.

Peters (2017) argues that firms will press for open migration policies especially if they face strong

international competition and are limited to operating in their home country; once firms can move

production anywhere in the world, their concerns about immigration end and they no longer press

for open immigration policies.

Finally, MNCs are also the main proponents of preferential trade agreements and bilateral

investment treaties, according to numerous studies (Manger 2009; Kim 2015). And MNCs have

been the main advocates of the inclusion of provisions protecting investment and intellectual prop-

erty rights and liberalizing services in preferential trade agreements, as means to gain an edge

over MNCs from other countries, which are excluded from the trade agreements (Baccini 2019;

D¨ur, Baccini, and Elsig 2014; Rodrik 2018). Baccini, Pinto, and Weymouth (2017) argue that

intra-industry political divisions over preferential trade agreements exist and they show that large

and productive firms engaged in offshore production are the biggest beneficiaries and the most

ardent supporters. Some research also suggests that MNCs increasingly prefer to have decisions

made at the supranational level — that is, in international institutions like the WTO and IMF

or at international tribunals like International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes —

where they may have even greater influence than domestically (Prakash and Hart 1999; Levy and

Prakash 2003). Other studies show that they are the most likely to lobby for national compliance

in WTO Dispute Settlement rulings (Kim and Spilker 2019; Yildirim 2018). Generally, much of

the recent literature sees a large divide between domestic firms and large, global ones in terms of

their foreign economic policy preferences. Firms may also have significant preferences about more

domestic policies, especially tax, regulatory, and labor ones. Whether preferences regarding these

break down along domestic vs international lines seems less clear. The next question, however,

is whether all firms pursue political influence to secure their preferences and then how the battle

among firms and with other groups plays out in the political arena.

2.2 Political Influence of MNCs

The means of political influence that MNCs employ may differ from issue to issue and country to

country. In this regard, scholars as exemplified by Nye (1974) have identified three main channels

6

through which firms may exert their influence over foreign policy-making: direct influence through

lobbying, indirect influence as an instrument of the state, and unintentional influence via their

agenda-setting power. First, firms may directly engage in political activities such as lobbying and

campaign contributions to affect policy making or to press political leaders to address their de-

mands. In doing so, they can also work with industry associations and political action committees

to advance their interests. MNCs can leverage their bargaining power by offering both “induce-

ments” or promises of new investment and “deprivations” or threats of withdrawal of investment

(Nye 1974). Grossman and Helpman (1994) in their famous “Protection for Sale” model show

how lobbying activities of interest groups may change trade policy. In addition to direct lobbying,

firms can leverage informal ties to to political leaders that enable them to provide information and

persuasion (Bauer, Pool, and Dexter 1972; Denzau and Munger 1986). While this is inside pressure

(Culpepper 2011), these influence attempts can also involve the public. Outside lobbying includes

the use of public communication channels rather than exchanges with political elites, and involves

tactics such as contacting journalists, issuing press releases, establishing public campaigns, and

organizing protest demonstrations (Kollman 1998; De Bruycker and Beyers 2018).

Second, other scholars have argued that MNCs hold an unintended role in foreign policy as

instruments of the state (Gilpin 1975). In this view, governments have used MNCs to further

the national interest by strengthening the effects of sanctions through MNC production networks,

facilitating capital transfers through firms to strengthen monetary policy, or enabling MNC’s foreign

affiliates to assist in intelligence gathering (Nye 1974, p. 157). Finally, firms can hold considerable

agenda-setting power from their mere presence abroad. Firms’ “privileged position” in the view

of governments (Lindblom 1977) assists political leaders’ in defining problems, devising policies,

and prioritizing objectives. As Ray (1972, 82) long along noted, “[t]he influence of corporations on

American foreign relations stems primarily from their ability to shape the external environment

from which problems, conflicts, and crises grow, and their ability to define the axiomatic.” While

indirect and incidental lobbying are important avenues of influence, our empirical analyses below

focus on the first type of political influence, firms’ lobbying activities.

The literature on firms’ political influence points out that the most consistently interesting

explanatory factors of political activity in home countries have been firm size, degree of government

regulation, and the amount of firm or industry sales to the government (Mitchell, Hansen, and

Jepsen 1997; Drope and Hansen 2006). Countering the pressures of other groups that oppose their

interests (so called counter-mobilization) has also been an important reason for influence attempts

by firms (Austen-Smith and Wright 1994). The larger the firms, the more they try to exercise

political influence (Ansolabehere, de Figueiredo, and Snyder 2003; Hansen, Mitchell, and Drope

7

2004; Drope and Hansen 2006; Bombardini and Trebbi 2012; Naoi and Krauss 2009). The more

firms interact with the government and its regulations, the more political action they seem to

take. These large firms also tend to act on their own and not in coalitions or industry associations

(de Figueiredo and Richter 2014). There remains debate over whether connections or expertise

and information matter more for lobbying. In addition, the target of influence attempts has been

studied. Research suggests that firms target supporters and allies of their positions mostly and

some wavering groups in the middle of the political spectrum (Hall and Deardorff 2006; Gawande,

Krishna, and Olarreaga 2012). They are less likely to try to convince opponents to change their

positions.

The literature at least for the US shows that business lobbying entails far more funds than do

campaign contributions. Milyo, Primo, and Groseclose (2000) demonstrate that lobbying expen-

ditures at the US federal level are five times those of campaign contributions to political action

committees. Firms of all sizes may suffer from collective action problems that deter political action

which is costly; however, large firms and hence MNCs may be less affected by this problem (Alt

et al. 1996). Firms’ political activities may lead to actual policy changes.

5

Gordon and Hafer

(2005) and Blonigen and Figlio (1998) demonstrate that lobbying by firms can affect national

policies and influence on individual legislators. Fisman (2001) and Faccio (2006) also find that po-

litically connected firms benefit economically from these ties, and that larger firms, which are more

likely to be MNCs, are more likely to have such connections. Furthermore, there is additionally

some evidence that firms which lobby become bigger as a result, thus underscoring their successful

influence (Huneeus and Kim 2018; Akcigit, Baslandze, and Lotti 2018).

A key finding of the research on business political activity is that large firms lobby the most.

Numerous studies demonstrate that large firms spend the most on direct lobbying (Boies 1989;

Grier, Munger, and Roberts 1994; Ansolabehere, de Figueiredo, and Snyder 2003; Hansen and

Mitchell 2000; Hansen, Mitchell, and Drope 2004; Drope and Hansen 2006; Bombardini and Trebbi

2012; Naoi and Krauss 2009). This arises for several reason. First, these firms have the most

resources. The size of the firm reduces the “two primary costs of lobbying”: the initial costs

to establish a lobbying presence and the actual amount spent to influence policy (Kerr, Lincoln,

and Mishra 2014; Hafner-Burton, Kousser, and Victor 2015, p. 10). Bigger firms have a greater

capacity to pay the upfront costs of establishing a lobbying presence (Bertrand, Bombardini, and

Trebbi 2014; Kerr, Lincoln, and Mishra 2014; Kerr et al. 2017). Therefore, large firms “select into”

lobbying whereas smaller firms cannot (Blanga-Gubbay, Conconi, and Parenti 2019; Alt et al.

1996).

Moreover, larger firms utilize their resources to actually spend more (Kim 2017; Dellis and

5

See Baumgartner et al. (2009) for a debate on this issue.

8

Sondermann 2017; Igan, Mishra, and Tressel 2012) and forge closer ties with politicians (Fisman

2001; Faccio 2006). Because bigger firms have more expendable resources to influence politicians

whereas policymakers are resource-poor (Drope and Hansen 2006), these firms hold an advantage.

The biggest firms are also able to leverage considerable informational advantages (e.g., expert and

technical information) which help to reduce uncertainty for policymakers (Helleiner 2011; Lall 2012;

Young 2012).

By shouldering the initial upfront costs and engaging in lobbying, firm lobbying usually begets

more lobbying. Kerr, Lincoln, and Mishra (2014, p. 166) “report a 92% probability that a firm

will lobby in a given year conditional on lobbying in the prior year” (de Figueiredo and Richter

2014). Bigger firms may also hold a first-mover advantage where regulators become more amicable

to protecting the firm to preserve the reputations of the firm and the bureaucrats. This leads to

“protection without capture” or consistently favorable treatment by regulators (Carpenter 2004).

A second reason for larger firms to be more politically active is because policies are becoming

increasingly granular (e.g., product-specific trade policy), and therefore lobbying becomes a cost-

benefit analysis of individual firms. In fact, scholars have consistently found that large firms

and MNCs often choose to lobby alone and lobbying is becoming increasingly “particularistic”

(Mizruchi 2013). Gilligan (1997, p. 455) argued that since firms involved in “intra-industry trade

are monopolists, lobbying essentially becomes a private good” and thus they are willing to lobby

alone and bear the costs. Further, as Johns, Pelc, and Wellhausen (2019, p. 732) demonstrate

growing globalization has led to not “only an overall increase of lobbying but more lobbying by

individual firms rather than through industry associations, thus contributing to what Drutman

(2015) has described as ‘growing particularism’ in corporate lobbying.”

To be sure, lobbying through industry associations still serves as an important channel through

which firms exert their political powers. However, there are other reasons why firms might choose

to lobby alone. Large firms are more likely to have in-house lobbying offices which reduces the

importance of trade associations (Vogel (1996) as cited in Walker and Rea (2014, p. 11)). Finally,

lobbying alone can be more effective than a coalition of strange bedfellows with a cacophony of

voices, diluting the overall message (Nelson and Yackee 2012) or a large coalition when the salience

of the issue among policymakers is low (Junk 2019). Following these findings about the importance

of lobbying by firms themselves, our research focuses on this particular aspect of political activity.

As pointed out above, much of the research on the political activity of business has shown that

big firms are distinct. But are MNCs different from big firms in general? Recent work on MNCs

and foreign economic policy shows that these firms are very active and powerful political actors,

maybe even more than big domestic firms. They may have different preferences in foreign policy,

9

be more active, and more likely to act on their own. In particular, the new, new trade theory

with its heterogeneous firm models of trade has changed our understanding of trade politics. The

largest, most productive firms within an industry tend to be the main exporters and multinationals

and hence should favor trade and other forms of engagement with the world economy since they

benefit hugely from this. Furthermore, these pro-trade firms may have sizable advantages in terms

of political action, both in association with other large firms and on their own. Large global firms

have both greater financial resources to invest in political influence and the scale to make those

investments profitable given that political investment has fixed costs (Kim and Osgood 2019).

Because of their large benefits from trade and their small number, they also may avoid collective

action problems (Gilligan 1997; Kim 2017).

MNCs may have distinct preferences from domestic firms and they may be focused on different

issues. Studies also show that large global firms are significantly more likely to support trade

liberalization and to lobby for it in a variety of countries, including the US, Japan, and Costa

Rica (Plouffe 2017; Osgood et al. 2017).

6

Osgood (2018) points out that the gains from trade are

highly concentrated in a few firms in the US and that these firms have GVCs that are specific

to certain countries or regions. These facts mean that MNCs in the US lobby extensively in

a pro-trade direction and support strongly trade agreements with the specific set of countries

they deal with. These MNCs outweigh and out lobby domestic firms that oppose trade and they

overcome collective action issues because each firm gains greatly from trade and lobbies on different

agreements according to their GVC partners. Further, Kim (2017) shows that international firms

lobby individually to reduce trade barriers on highly specific products, again because they anticipate

large gains from such liberalization on their products.

Other research also shows that MNCs have particular preferences in trade that probably shape

their attempts at influence. Kim et al. (2019) demonstrate that for many types of firms, the

standard trade policy measures of the past —tariffs and subsidies— are no longer their most

important concerns; instead, the nature of firms’ involvement in global value chains shapes their

preferences so that other policy issues, such as the protection of foreign investments, are most

important for multinational corporations these days. These distinctive preferences and outsized

resources mean that MNCs, even more than big domestic firms, may prefer to be very active and

to operate alone in the political arena. It also suggests that MNCs may be interested in different

issues than domestic firms.

6

Moreover, the labor force involved in firms may follow the preferences and political actions of their firms, rather

than their industry or union. The heterogeneous impact of globalization on firms in an industry produces hetero-

geneous effects on workers such that those employed in larger and more globally competitive firms will be likely to

support trade and those in small, uncompetitive firms will be more likely to oppose trade (Dancygier and Walter

2015). However, offshoring may complicate this: workers doing offshorable tasks may be especially opposed to trade

if they work at large, globally engaged firms (Rommel and Walter 2018).

10

Foreign multinationals in the US are also involved in political activity. Mitchell, Hansen, and

Jepsen (1997) shows that foreign-owned firms in the US form and join fewer PACs and give smaller

campaign contributions than do similar sized domestic firms. In later work Lee (2018) studies

foreign multinational corporations in the US and concludes exactly the opposite. She shows that

they seem to use their subsidiaries in the US as local political agents who can influence the US

government. Using PAC contribution data, she finds that US subsidiaries of foreign firms have a

greater likelihood to sponsor a PAC compared to similarly sized American firms, and to also give

much greater amounts of campaign contributions. These studies also show, however, that foreign

MNCs tend to be large, powerful political contributors in the US.

While our research is more focused on the US, it is very likely that MNCs play similar roles in

other countries and perhaps exert even more influence there because of their even greater presence

in smaller economies. There has been a long literature on MNC influence in developing countries

which are hosting their investments. The dependency literature, as its name suggests, focused

attention on how MNCs could realize their preferences and obtain better deals with these host

countries because of their bargaining advantages (Biersteker 1978; Moran 1973, 1978; Evans 1979).

Other early research indicated that foreign investors could be at a disadvantage over time and that

they faced an obsolescing bargain where the host country could expropriate them once they had

invested (Vernon 1971, 1980). Much evidence now suggests that the obsolescing bargain is not very

evident and that firms have developed lots of strategies to prevent this from occurring (Hillman,

Zardkoohi, and Bierman 1999; Eden, Lenway, and Schuler 2005; Henisz and Zelner 2005). The

stress more recently has been on how MNCs protect their investments in host countries and what

characteristics of host countries are most propitious for safeguarding them. The business literature

notes how foreign firms can use alliances with domestic partners and host governments to mitigate

risk (Malesky 2008; Eden and Molot 2002; Stopford and Strange 1991; Pinto 2013; Pinto and

Pinto 2008). They can also integrate into global supply chains (Johns and Wellhausen 2016), build

political ties with host-state policy makers (Henisz and Zelner 2005), ally with politically powerful

multilateral institutions (Nose 2014), and threaten and pursue investor-state arbitration using the

global network of bilateral investment treaties (Salacuse 2010; Allee and Peinhardt 2011; Simmons

2014; Johns and Wellhausen 2016).

Another branch of the literature focuses on choices of MNCs about which host country to

invest in. This range of choice is often seen as giving MNCs great leeway to negotiate better deals

with host countries and to influence their politics. In particular, the number of veto players in

the government, the degree of private property protection, and the extent of democracy all may

affect whether MNCs can protect their investments and hence whether they invest in the first place

11

(Jensen 2003; Li and Resnick 2003; Henisz and Williamson 1999; Henisz 2000). First, more veto

players, on the one hand, makes it harder for governments to change policies and thus reduce any

ex post attempts to change the bargain with MNCs. However, more veto players may also mean

more access points for MNCs and make it easier for them, especially in combination with other

foreign and domestic firms, to influence policy (Ehrlich 2007, 2008; Pyle 2006; Gillespie 2006).

Second, more democracy and better private property protection, on the one hand, enable MNCs

to be more likely to find allies in the host country that will help them. On the other, more political

competition and more space for different interest groups in vigorous democracies seem to weaken

MNCs and lessen their influence (Jensen et al. 2012). Finally, MNCs can call on their home country

government for assistance (Krasner 1978; Lipson 1985; Fisman 2001; Wellhausen 2014; Truex 2014;

Lee 2019; Gertz 2018). When political leaders desire foreign investment, this ability to choose

locations enables MNCs to exercise important influence over the host country and its politics. The

conditions that maximize MNC political influence are still much debated, however.

In particular, a large number of studies have pointed out how MNCs have shaped the economic

reform process in many developing host countries. They show that MNCs can affect local policy

decisions in host countries by providing information and policy expertise about regulations in

other countries, by lobbing officials, especially in alliance with local actors, by promising benefits

such as more employment and access to new technology, by threatening to cut employment or

withdraw, and by helping leaders to overcome entrenched local interests by offering more revenue

or employment (Li and Reuveny 2003; Rudra 2005; Mosley and Uno 2007; Malesky 2009; Jensen

et al. 2012). Many of these influence techniques for host countries are the same as noted for home

countries.

It is also important to note that MNCs may influence international institutions as well as

domestic governments; Hanegraaff et al. (2015) point out that the most organized domestic interest

groups such as MNCs are also the most potent actors in many international organizations like the

WTO. Indeed some studies claim that MNCs are now more powerful than ever in their influence

due to globalization and the capital mobility it creates (Vernon and Spar 1989; Strange 1996; Levy

and Prakash 2003). These studies suggest that MNCs have a plethora of means to exert powerful

influences over the countries they choose to operate in. These issues and forms of influence are

very important to keep in mind when assessing the power of MNCs. But here our attention is on

their political activity in the US. In some ways this is a hard case for finding MNC influence since

the US political system is highly institutionalized and filled with checks and balances.

The past research surveyed above leads us to focus on at least three key issues. First, are there

differences in the type or level of political activities of MNCs and domestic firms? Second, are any

12

differences we see in political activity among firms due just to differences in their size or are they

due to their extent of global ties? Third, do MNCs focus on different issues than domestic firms in

their political activity? These questions have been less systematically addressed in previous work.

3 Data

Despite the significance of MNCs in foreign policy making, quantitative studies of their political

activities have been limited by the absence of direct measures of their economic and political

activities. In this section, we describe two key firm-level variables that we develop for our empirical

analysis in Section 4: 1) multinationality, and 2) lobbying activities.

3.1 Measuring Multinationality

We begin by measuring a firm’s status as a multinational. This is key for our empirical analysis as

our goal is to examine whether firms’ lobbying activities change after they become multinational.

We define a MNC as a corporation that owns or controls production of goods or services in at least

one country other than its home country. We develop a binary measure of firms’ multinationality

based on the financial statements of all public firms available through Compustat database.

Following Dyreng et al. (2017), we begin by computing the ratio of a firm’s pretax foreign income

to its total pretax income in a given year. In fact, the use of this measure is justified by the section

§210.4-08(h)(1), Income Tax Expense, of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

rules, which mandates the disclosure of the components of income as either domestic or foreign.

7

Note that this is still a noisy measure of firms’ multinationality as some foreign income might be

generated by other activities that are not directly related to the production of goods or services

such as tax avoidance.

8

Thus, we further improve the measure by identifying a cutoff in the pretax foreign income

to total income ratio such that the resulting binary measure of multinationality approximates

the distribution of some known statistics of multinational firms in the BEA data. Specifically, we

compare the distribution of MNCs’ sales against the corresponding numbers reported in Faulkender

and Smith (2016), which is one of very few studies that directly measures multinationality based

on the BEA data and calculates the aggregated characteristics of the MNCs using Compustat

dataset. This allows us to directly merge the economic data with the lobbying dataset. We utilize

the numbers that appear in Table 1 of their paper, where the authors report logged sales data

separately for all Compustat firms, MNCs from the BEA data, and Compustat firms that aren’t

7

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) defines foreign income as the income generated from

operations outside of the U.S. that is over 5% of the total income.

8

Dyreng et al. (2017) proposes six alternative measures of multinationality.

13

Number of Firm−year Observations

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

0 500 1000 1500

Pretax Foreign Income / Total Income

Figure 1: Histogram of Continuous Multinationality Measure: This figure shows the dis-

tribution of the ratio of firms’ pretax foreign income to its total pretax income. The vertical red

dotted line corresponds to the cutoff (= 0.02139) that we used to match the mean logged sales of

MNCs reported based on the BEA data in Faulkender and Smith (2016). We code the firm-year

as multinational if the ratio is above the cutoff and domestic otherwise.

in the BEA data (i.e., domestic firms).

9

This provides a valuable opportunity for us to match the

sales distribution of MNCs in our data that approximates that of the BEA data. We took the mean

sales (logged) among Compustat firms, and then identify a cutoff in the continuous measure such

that the mean sales of the firms above the cutoff matches exactly the number reported in the paper

based on the direct measure of multinationality. Figure 1 shows the cutoff that we identified in

the distribution of pretax foreign income to total income ratio, i.e., 0.02139. Using this cutoff, we

define firm i as multinational at year t if its pretax foreign income to total income ratio is above

the cutoff and domestic otherwise.

We then carefully check the validity of our measure both quantitatively and qualitatively. First,

we compare the employment size of multinationals that are published by the BEA employment

numbers

10

against the number computed by our own measure of multinationality. According to

the BEA, MNCs employed 28, 022, 900 workers in the U.S. in 2016. Using the binary measure

of multinationality that we developed, we find that MNCs employed 27, 352, 666 people, which

matches remarkably well with the ground truth number based on the BEA data. Note that one

9

We note two issues. First, the authors claim to report “the natural logarithm of sales” yet they report numbers

of 5000 and more. We suspect these numbers are not logged. Second, they report a total of 39,894 Compustat

observations from 1995 to 2011. The Compustat data over that period, however, includes 172,425 observations. The

authors report using only those observations for which “relevant variables are non-missing.” Thus, we try to replicate

their strategy by eliminating observations that have missing data for shareholders’ equity (teq) and long-term debt

(dltt), arriving at the comparable number of 41,265 observations.

10

See https://apps.bea.gov/scb/2018/09-september/0918-multinational-enterprises.htm#mnes

14

0−500 501 − 1,000 1,001 − 10,000 10,000 +

Number of Employees

Number of Firms

0 200 400 600 800 1000

All Industries

BEA

Our Measure

0−500 501 − 1,000 1,001 − 10,000 10,000 +

Number of Employees

Number of Firms

0 100 200 300 400 500

Manufacturing Industries

BEA

Our Measure

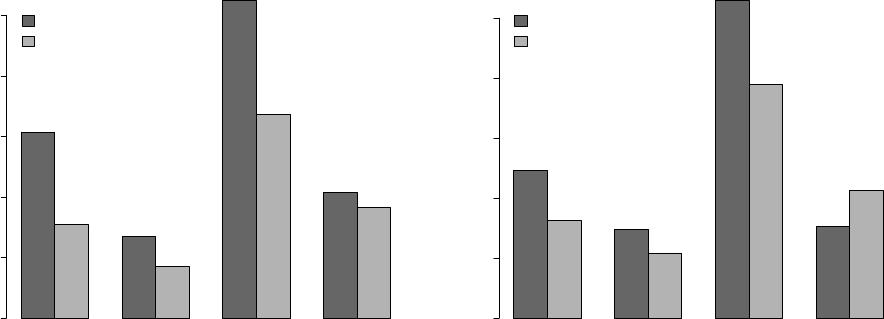

Figure 2: Comparison of Number of Employees: This figure compares the distribution of

MNCs based on four different size categories in terms of the number of employees. The left and

right panel shows the distribution across all industries and manufacturing industries, respectively.

Dark gray bar represents the numbers reported in Barefoot and Mataloni Jr (2011) who used the

BEA data. The light gray bar on the right represents the number of MNCs in each category

computed based on our measure of multinationality. It shows that we reasonably approximate the

true distribution. Note that the BEA data includes both public and private firms while we only

consider public firms using Compustat database.

cannot directly compare the numbers as the BEA data include both private and public companies,

whereas the Compustat data only include public entities.

Second, we perform another validity check by looking at the number of MNCs as reported in

Barefoot and Mataloni Jr (2011) who use the BEA data from 2009 to present some stylized facts

about U.S. MNCs. In particular, in their Table 6 they report the number of MNCs by employment

size. Note again that as they use all of the BEA data, their numbers include both private and

public firms, and thus there will be more firms in the BEA data. Figure 2 compares the numbers

reported in Barefoot and Mataloni Jr (2011) with the proposed measure. As expected, we find that

there are more multinational firms in the BEA data. However, we find that the overall distribution

across different employment sizes based on our measure resembles that of the BEA data.

Finally, we validate the accuracy of our measure manually. Specifically, we took a random

sample of companies in the Compustat data for 2014 and checked whether we accurately code

their multinationality status. Table 1 displays the list of firm names that we randomly sampled. To

ensure the validity of our measure across firms with different sizes, we sampled firms based on their

sales. We checked each firm online and verified that our measure indeed captures multinationality.

For example, the Federal National Mortgage Association, also known as Fannie Mae, is a U.S.

government sponsored enterprise that provides mortgage-backed securities, and we accurately code

15

Domestic Multinational

Big companies

Federal National Mortgage Association Primerica Inc

Cracker Barrel Old Country Store Inc Grainger (W.W.) Inc

Saia Inc Outerwall Inc

Heartland Payment Systems Inc II VI Inc

Denbury Resources Inc. Tiffany & Co.

Time Warner Cable Inc Cabot Corp

Neiman Marcus Inc PTC Inc

Voya Retirement Insurance and Annuity Co Total System Services Inc.

Steel Dynamics Inc Invacare Corp

MSC Industrial Direct Co Inc. Verizon Communications Inc

Medium companies

Griffin Industrial Realty Inc CUI Global Inc

Capitol Federal Financial Inc Royal Gold Inc

Entercom Communications Corp. Powell Industries Inc

Canterbury Park Holding Corp Zynga Inc

Palmetto Bancshares Inc RealNetworks Inc

Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia Inc. FalconStor Software Inc

Empire Resorts Inc RealD Inc

Flagstar Bancorp Inc. Daegis Inc

AtriCure Inc PFSweb Inc

Sequenom Inc Delta Apparel Inc

Small companies

Cellular Biomedicine Group Inc Success Holding Group International Inc

International Barrier Technology Inc BeyondSpring Inc

Notis Global Inc Histogenics Corp

Alpha Network Alliance Ventures Inc EPIRUS Biopharmaceuticals Inc

Ecosphere Technologies Inc Uranium Energy Corp

Viaspace Inc Alimera Sciences Inc

Anterios Inc Brainstorm Cell Therapeutics

Matinas BioPharma Holdings Inc SurePure Inc

XZERES Corp Generex Biotechnology Corp

Infinite Group Inc Midway Gold Corp

Table 1: Sample of Companies examined.

it as domestic. On the other hand, Primerica is a marketing company with a 2017 net income of

$300 million, operating mostly in the U.S. and Canada.

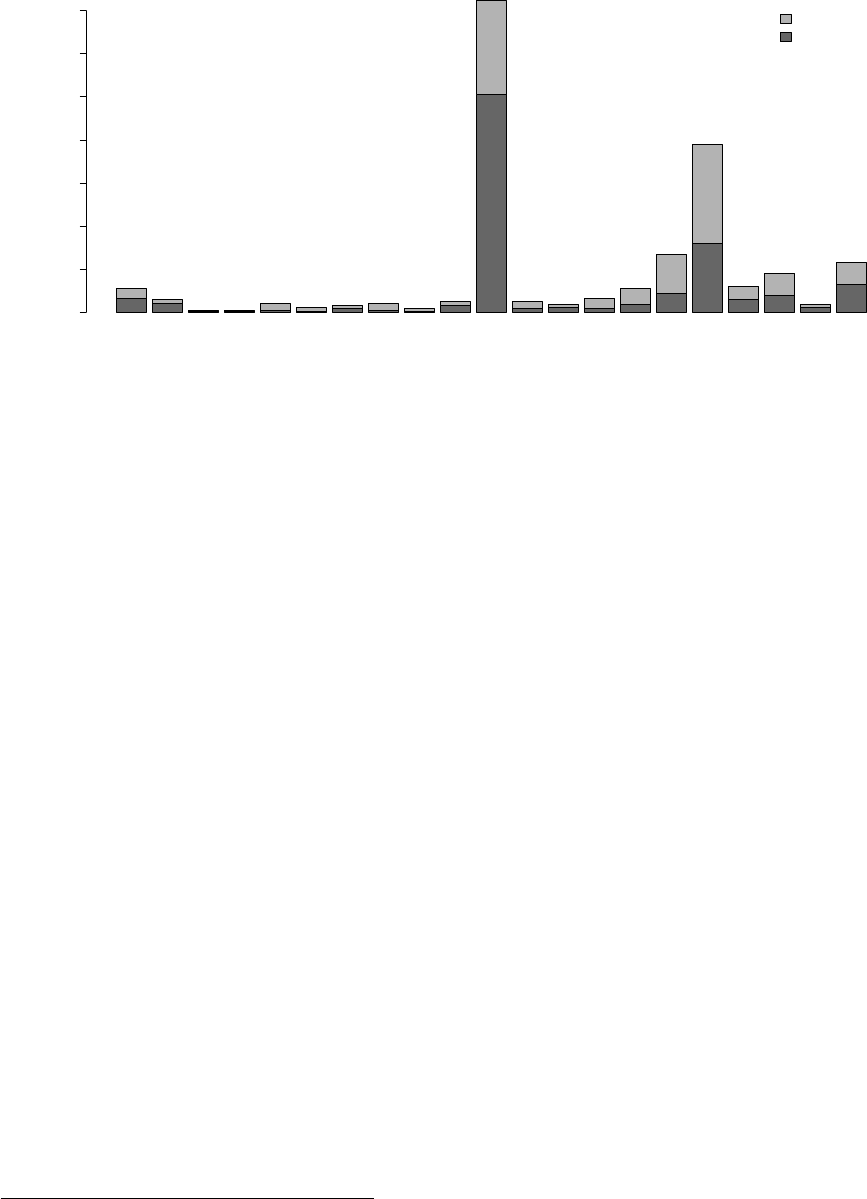

Figure 3 shows the distribution of MNCs across various manufacturing industries.

11

On average,

we find that 46% of Compustat firms are multinationals. This number is comparable to the one

reported in Dyreng et al. (2017), who find that about 40% of the same firms in their analysis

are multinationals.

12

Having defined and identified public firms in the US that are multinational

and differentiating them from domestic firms, we can now compare the lobbying activities between

MNCs and domestic firms within each industry in Section 4.

3.2 Measuring Lobbying Activities

The Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 (amended by the Honest Leadership and Open Government

Act of 2007) requires lobbyists (e.g., K-street lobbying firm) to file quarterly reports on behalf of

11

In terms of total sales of all public firms, manufacturing industry accounts for about 37% of total sales (about $

10 trillion) in the U.S. economy as of 2018. Out of this, about half of the sales is from MNCs.

12

They find that the number increases up to 70% in 2012.

16

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700

Multinational

Domestic

Number of Firms

Food

Beverage and Tobacco

Textile Mills

Textile Product Mills

Apparel

Leather

Wood

Paper

Printing

Petroleum and Coal

Chemical

Plastics and Rubber

Nonmetallic Minerals

Primary Metal

Fabricated Metal

Machinery

Computer and Electronics

Electrical Equipment

Transportation Equipment

Furniture

Miscellaneous

Figure 3: Distribution of MNCs across Manufacturing Industries: This figure displays

the distribution of MNCs across three digits NAICS industries in 2017. On average, 46 percent

of Compustat firms are multinationals. Note that Chemical industry has the largest number of

firms while it accounts for about 17% of the total sales in manufacturing industry.

their clients (e.g., MNC) describing lobbying activities. In doing so, they should report lobbying

expenses (or their income), lobbied issues (e.g., international trade), and lobbied congressional bills

among others.

We use LobbyView database that parses through the universe of 1, 111, 859 lobbying reports

filed from 1999 to 2019 (Kim 2018). The primary benefit of using LobbyView is that it provides

unique firm-level IDs linked to the Compustat data. Using the identifier, we are able to merge the

lobbying data with Compustat so that we can use the multinationality measure that we developed

in the previous section to examine political activities of MNCs across time. The lobbying reports

also contain detailed information about firms’ political activities. There exist a list of 79 issue

categories specified in the Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 such as international trade (TRD),

defense (DEF), and immigration (IMM).

13

For each issue category, lobbying firms are required to

describe lobbying activities on behalf of their clients. For example, Figure 4 shows that Panasonic

Corporation of North America actively engages in lobbying activities affecting various trade

policies such as the Rules of Origin (RoO) in NAFTA.

14

13

The complete list of Lobbying Issues is available from https://lda.congress.gov/LD/help/default.htm?turl=

Documents%2FAppCodes.htm

14

The original report is available from https://soprweb.senate.gov/index.cfm?event=getFilingDetails&filingID=234D3211-

32EA-4C8E-B4EC-01540AEE2036&filingTypeID=51 Note that Panasonic Corporation of North America does not

enter in our empirical analysis below as we focus on public firms in the U.S.

17

Border Adjustment Tax (BAT) - Tax on imports with exemption on exports - Explain negative impact

of BAT on company sales and U.S. employment Office of the United States Trade Representative Docket

USTR-2017-0006 - Request for Comments on Negotiating Objectives Regarding Modernization of the

North American Free Trade Agreement With Canada and Mexico - Rules of Origin for products man-

ufactured in Canada and Mexico S. 2098, H.R. 4311 - Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization

Act of 2017 - National Security reviews of foreign investment or technology transfers H.R. 4170 - FARA

(Foreign Agents Registration Act) Reform - Disclosing foreign influence requirements.

Figure 4: First Quarter Report by Panasonic Corporation of North America in 2018

4 Empirical Results

In this section, we investigate whether firms tend to increase their lobbying expenses after they

become multinational. We first compare the differences between MNCs and domestic firms in

their economic and political activities at a given time. We find that MNCs are (1) larger and more

productive, (2) spend more on lobbying, and (3) lobby on a more diverse set of issues than domestic

firms. To account for various confounding factors and selection bias in our analysis, we employ the

difference-in-differences (DiD) identification strategy. We find that a firm tends to spend more on

lobbying when it becomes multinational than it only serves the home market.

4.1 Differences between MNCs and Domestic Firms

Many researchers find that MNCs differ from domestic firms in terms of their economic activities

(Tomiura 2007; Bernard, Jensen, and Schott 2009; Doms and Jensen 1998; Slaughter 2004). Among

others, MNCs are found to be larger, more productive, and more capital intensive than domestic

firms. We begin our analysis by checking the differences between MNCs and domestic firms based

on the measure that we developed in Section 3.1.

Figure 5 shows that MNCs are indeed larger and more productive than domestic firms, consis-

tent with the literature. The figure also sheds an important light on our empirical analyses: there

exist sufficient overlaps in the size and productivity distributions between MNCs and domestic

firms. This allows us to investigate the independent effect of multinationality on firms’ political

activities, while holding other factors that potentially drive firms’ preferences towards foreign pol-

icy constant. Indeed, the new, new trade theory predicts that more productive firms are more

likely to engage in exporting and benefit from trade liberalization. Figure 5 shows that there exist

highly productive domestic firms that are not multinational. To the extent that they do engage in

international trade (i.e., not all exporters are MNCs), therefore, we can compare the differences in

political activities between MNCs and domestic firms due to their differences in multinationality,

while accounting for the fact that they both engage in international trade and are similar in size.

Next, we examine MNCs’ lobbying activities. We construct two outcomes variables. First, we

compute the total lobbying expenditure by aggregating all the lobbying expenses across lobbying

18

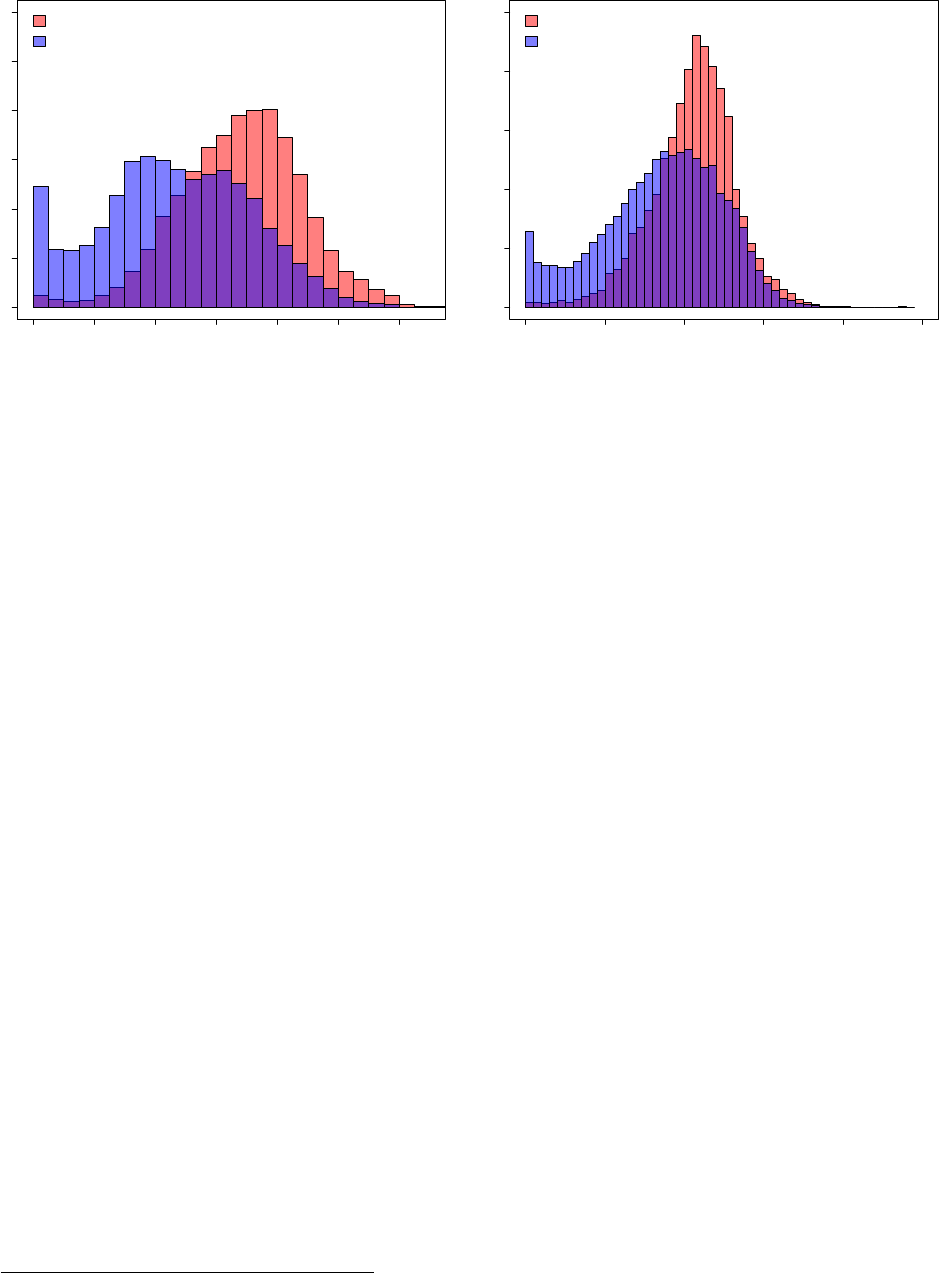

Density

0 2 4 6 8 10 12

0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15 0.20 0.25 0.30

Multinational

Domestic

Sales (logged)

Density

0 2 4 6 8 10

0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5

Multinational

Domestic

Productivity (logged)

Figure 5: Overlaps in the Distribution of Sales and Productivity: This figure compares

the distribution of firm size and productivity (measured as value-added per labor) between do-

mestic and multinational firms. It confirms that multinational firms tend to be bigger and more

productivity consistent with the findings in the literature. It also shows that there exist sufficient

overlaps in the two distributions. In our later analysis, we will match on these firm-level character-

istics in order to account for the possibility that these variables confound the relationship between

multinationality and lobbying activities.

reports filed on behalf of each firm. Note that there are multiple reports filed in a given year

because each lobbying firms (either in-house lobbying department or K-street lobbying firms) must

file quarterly reports. Second, we identify the set of issues, out of the 79 categories, that are

reported to have been lobbied at least once in each report. This allows us to identify the differences

in lobbying activities between MNCs and domestic firms.

Table 2 summarizes our analysis based on the OLS regression. In this analysis, we consider

all publicly traded firms that have lobbied at least once between 2007 and 2017. Models (1)–

(4) use lobbying expenditure, while models (5)–(8) consider the number of lobbied issues as the

outcome variable. We find that MNCs tend to spend more on lobbying and that they lobby on

more issues. To examine the differences between MNCs and domestic firms within industries (see

Figure 3 for example), we include the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS)

3-digit industry-level fixed effects. Our finding suggests that firms differ in their political activities

even when they are in the same industry. This is in contrast to the existing studies of trade politics

that tend to focus primarily on inter-industry differences (e.g., Hiscox 2002). We also control for

year fixed effects to account for the heterogeneity across time. Finally, we include capital size

and the existence of an in-house lobbying department as firm-level controls.

15

In sum, MNCs are

15

We include the existence of in-house lobbying department as a control because organization expenses using

LDA expense reporting method differs from lobbying firm income. See https://lobbyingdisclosure.house.gov/

amended_lda_guide.html for details.

19

Lobbying Expenditure Number of Issues Lobbied

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8)

Multinational 0.899

∗∗∗

1.239

∗∗∗

1.203

∗∗∗

0.461

∗∗∗

1.649

∗∗∗

2.198

∗∗∗

2.182

∗∗∗

0.858

∗∗∗

(0.061) (0.074) (0.074) (0.067) (0.072) (0.094) (0.095) (0.077)

Capital 3.035

∗∗∗

4.141

∗∗∗

(0.063) (0.072)

In-house 0.0002

∗∗∗

0.001

∗∗∗

(0.00002) (0.00002)

Constant 11.535

∗∗∗

12.316

∗∗∗

12.151

∗∗∗

11.128

∗∗∗

3.783

∗∗∗

4.432

∗∗∗

4.401

∗∗∗

2.838

∗∗∗

(0.035) (0.557) (0.563) (0.487) (0.041) (0.710) (0.719) (0.559)

NAICS3 FE X X X X X X

Year FE X X X X

Observations 14,732 9,385 9,385 9,327 14,732 9,385 9,385 9,327

R

2

0.014 0.107 0.110 0.319 0.034 0.188 0.189 0.498

Adjusted R

2

0.014 0.100 0.101 0.313 0.034 0.181 0.181 0.494

Note:

∗

p<0.1;

∗∗

p<0.05;

∗∗∗

p<0.01

Table 2: Lobbying Expenditure and Number of Issues Lobbied by MNCs: This table

displays estimated effects of MNCs on lobbying expenditures and the number of lobbied issues by

firms in all industries. We find that MNCs tend to (1) spend more on lobbying and (2) lobby on

more issues than domestic firms, on average.

clearly different in their political activity from domestic firms; holding size and industry constant,

they lobby more and do so on more issues.

4.2 Matching Analysis

Although the analysis in the previous section shows that MNCs exhibit different lobbying ac-

tivities compared to domestic firms, there are many potential endogeneity problems that prevent

researchers from drawing causal inferences in observational studies, especially when firms are highly

heterogeneous. For example, our focus on the firms that lobbied at least once (i.e., intensive margin)

may introduce a bias if firms have distinct organizational structures that determine the propen-

sity of their lobbying activities (i.e., extensive margin). Others may have distinct trends in their

growth which might be correlated with their economic and political activities (see, Meyer 1995, for

an overview).

In this section, we apply a difference-in-differences (DiD) estimator to investigate the causal

effect of multinationality on lobbying behavior. We proceed in three steps. First, we identify a

total of 210 companies whose multinationality status changed between 2007 and 2017. To ensure

that they indeed turned from domestic to multinational, we then carefully investigate each one of

them relying on public information available from the media and online resources. We find that we

correctly capture the treatment status as well as its timing for most of them using our measurement

strategy described in Section 3.1. For example, we find that ABM Industries became a MNC in

2014. In fact, the firm made a number of acquisitions around the period, including that of GBM

Support Services Group Limited, a U.K. company. We also find that Metlife is measured as MNC

since 2010. This firm purchases American Life Insurance Company (ALICO), with operations in

20

Japan and a number of European countries. Similarly, we are able to find that Autozone became

a MNC when the company opened its first store in Brazil. Note that a subsidiary, Autozone

de Mexico, opened in 2003.

16

Note that a majority of these companies became MNCs through

purchases and mergers with multinational or foreign companies.

17

Second, for each “treated” firm i that became a MNC at year t (i.e., X

it

= 1), we find the set

of all domestic firms that have an identical treatment history only up to year t − 1, i.e., firms that

remain to be domestic at t. Formally,

M

it

= {i

0

: i

0

6= i, X

i

0

t

= 0, X

i

0

t

0

= X

it

0

for all t

0

= t − 1, . . . , t − L} (1)

where X

it

denotes the MNC status for firm i at year t. Out of these domestic firms, we find

the set of five closest “matched control” firms in the set M

it

that are similar in terms of their

pre-treatment observable characteristics including sales, productivity, employment size, presence

of in-house lobbying department, and number of issues lobbied in years t − 3 to t − 1.

18

We

compute the average Mahalanobis distance measure between the treated observation and each

control observation over time.

19

Simply put, we find domestic firms that are comparable to the

firm that turned into a MNC in terms of their economic and political characteristics.

Finally, using these matched control firms, we compute the DiD estimate. Specifically, we

compare the difference in lobbying expenses of the treated multinational firm i between year t and

year t + F against the mean difference in lobbying expenses during the same period among the

matched control domestic firms. Under the parallel trends assumption, this gives an estimate of

the effect of the firm’s turning into a MNC on its lobbying expenditure. We then take the average

of this estimate across all treated firms to gain our average treatment effect estimate. Formally,

our quantity of interest is given by:

ˆ

β =

1

N

N

X

i=1

(Y

i,t+F

− Y

i,t−1

) −

1

|M

it

|

X

i

0

∈M

it

Y

i

0

,t+F

− Y

i

0

,t−1

(2)

16

Other examples include: OneMain Holdings, formerly known as Springleaf Holdings, acquired OneMain Fi-

nancial from Citi; Danaher Corp merged with Beckman Coulter, an American company that also entertains

operations in Japan. In 2012, it also acquires the British company Naveman Wireless; Jefferies Financial Group

(then named Leucadia) merges with Jefferies Group, an American multinational investment bank with operations in

Europe and Asia. In 2015, the company makes an investment in FXCM, a British firm; Delcath Systems obtained

authorization to market and sell one of their products in Europe; MannKind Corp is a pharmaceutical company

that has products in clinical trials in the US and Europe; Boulders Brands purchased Davies Bakery, a British

company; InfuSystem Holdings is a medical devices company that currently sells its products and services in the

US and Canada.

17

Based on our measurement strategy, we do not find any firms reverting back to purely domestic.

18

We adjust for past outcomes as we are concerned that past outcomes may affect both the treatment and the

current outcome.

19

Formally,

1

3

P

3

`=1

q

(V

i,t−`

− V

i

0

,t−`

)

>

Σ

−1

i,t−`

(V

i,t−`

− V

i

0

,t−`

) where V

it

0

is the pre-treatment observable co-

variates that we match (such as sales and productivity) and Σ

it

0

is the sample covariance matrix of V

it

0

.

21

●

●

●

●

−0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5

Time

Estimated Effects of Treatment Over Time

t+0 t+1 t+2 t+3

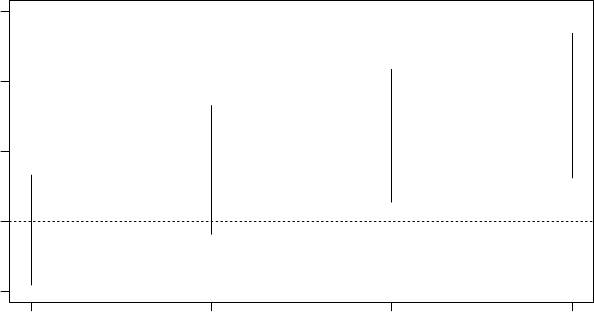

Figure 6: Effects of Multinationality on Lobbying Expenditure: This figure displays the

estimated treatment effects of firm’s turning to multinational corporation at time t on its lobbying

expenditure from time t to t +3. We find an increase in lobbying expenditure over time. We match

firms based on their size, productivity, employment, number of lobbied issues, and the existence of

in-house lobbying department.

We use the bootstrap standard errors developed by Imai, Kim, and Wang (2018) for statistical

inference.

In Figure 6, we present our main finding based on the DiD estimator in equation (2). We find

that firms increase their lobbying expenditure after they become a MNC. The estimated effects are

positive and become statistically different from zero (the horizontal dashed line) two years after

the treatment status change (see t + 2 and t + 3). The effect size is substantively significant as well:

we find that firms increase their expenditure about 50% (≈ exp(0.4) − 1) two years after becoming

a multinational.

Furthermore, we investigate the differences in lobbying activities for a few firms. We find that

AAR Corp (a firm in the aviation and defense industry) lobbied mostly on DoD appropriations

before it became a MNC, but started lobbying also on State Department appropriations in 2016 af-

ter becoming an MNE in 2014. Danaher lobbied on Title 1 of Senate bill S.2091 (112th Congress),

which deals with tax exemptions for foreign dividends and income in 2012, one year after becoming

an MNE. Sysco Corp (a company producing food products) reports that it lobbied on 2013 Farm

Bill, H.R. 2393 (114th Congress) two years after it became a MNC which would repeal the require-

ment for meat products to be labeled with their country of origin. Similarly, Berkeley W.R.

Corp (an insurance company) starts lobbying the year it becomes an MNC in 2011 on “legislation

related to tax treatment of underwriting and investment profits of foreign-owned insurance compa-

nies.” Finally, Pandora Media (a music streaming firm) increased its lobbying expenditure after

22

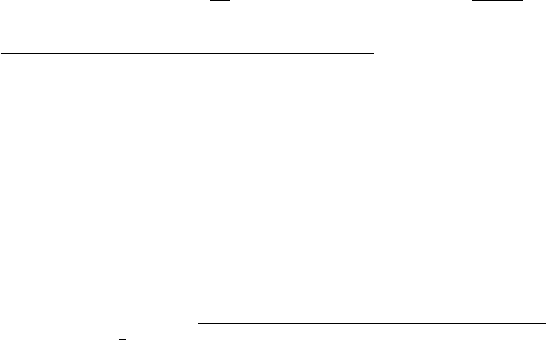

●

●

●

●

0.00 0.02 0.04 0.06

Time

Estimated Effects of Treatment Over Time

t+0 t+1 t+2 t+3

●

●

●

●

−0.2 −0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2

Time

Estimated Effects of Treatment Over Time

t+0 t+1 t+2 t+3

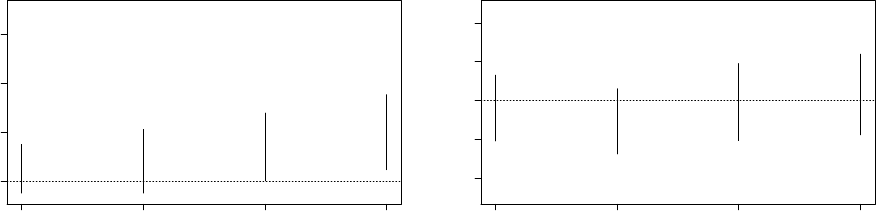

Figure 7: Effects of Multinationality on the Likelihood to Lobby on Tariff and Taxa-

tion Related Issues: This figure displays the estimated treatment effects of firm’s turning to

multinational corporation at time t on the likelihood of lobbying regarding Tariff (left panel)

and Taxation (right panel) policies. We find that multinational firms are more likely to lobby on

tariff policies. However, we find limited evidence for an increase in lobbying activities related to

taxation.

becoming a MNC in 2012. In addition to music licensing, it also began to lobby issues regarding

intellectual property, including online infringement, copyright, and patent litigation. Our findings

provide strong evidence that multinational play important roles in foreign policy-making.

We conclude this section by investigating whether certain issues are more likely to be lobbied

when firms become MNCs. We first shed light on the above finding that MNCs tend to lobby

on more issues (see Table 2). Specifically, for each firm that changed the status from domestic to

multinational, we check the set of new issues that are lobbied after firms became multinational.

We find that Energy/Nuclear (ENG), Budget/Appropriations (BUD), Defense (Defense), Health

Issues (HCR), Banking (BAN), and Foreign Relations (FOR) are the top lobbied issues. This is

expected as the policy issues are related to firms’ foreign operations.

To be sure, these issues may be as important for domestic firms as for multinationals. Fur-

thermore, there might exist various reasons why certain issues become more/less salient for both

domestic and multinational firms in certain industries across time. Thus, we again rely on the

difference-in-differences identification strategy to compare the changes in MNCs’ lobbying behav-

ior against the changes of lobbying activities by similar domestic firms in terms of their size,

productivity, and lobbying expenses. To minimize the difficulty in distinguishing foreign vs. do-

mestic policy, we focus on two specific policy domains that are comparable with each other with

differences in their international and domestic focus: (1) tariffs and (2) taxation. Figure 7 displays

the estimated effects. We find little evidence for any change in lobbying activities regarding taxa-

tion policies. However, we find that firms tend to lobby more on tariff policies once they became

multinational compared to domestic firms that are similar to them. In fact, Kim (2017) shows

23

that large and productive firms tend to lobby more on trade-related issues; in addition, he finds

that the differentiated products that they produce tend to have lower tariff rates on average. Our

findings suggest that more attention should be paid to MNCs’ political activities and their direct

effects on foreign policy-making.

5 Conclusion

MNCs are economically different than other firms, as many economists have now shown. But do

they differ politically? The past research on this topic has been limited for various reasons, one

being lack of systematic data on political activity. Past research points out that MNCs are likely

to have distinct preferences on foreign economic policy. As international actors who benefit from

access to a global market, they are likely to be more favorable to policies that foster an open

world economy. Furthermore, they may be more attuned to trying to harmonize regulations across

borders. Reducing all costs for global activities is key for them. Moreover, being larger and more

productive than most domestic firms, they have more means to try to influence politics. Studies of

particular countries, firms, sectors, and issues often reveal the strong influence of MNCs (Vernon

1971; Strange 1991; Sampson and Sampso 1973; Gereffi 1983; Manger 2012; Osgood 2017; Kim

2017). But systematic evidence across firms, sectors, and issues has been harder to bring to bear.

Our study here tries to do this using new data. We first devise a method of identifying firms as

multinational versus domestic. After validating this measure, we use it to show that indeed those

we identify as MNCs have the particular characteristics that economists have noted that MNCs

should possess: they are larger, more productive, and more export-oriented. Then we show that

MNCs spend more on lobbying and lobby across a more diverse set of issues than do domestic

firms. To more closely causally identity this, we also show that when a firm turns multinational

its political activity changes: it becomes more active, lobbying more and over more issues, as

compared to other firms. Past research has shown that big firms are different politically, but we

show that MNCs are even distinct from big domestic firms. MNCs are politically different, as well

as economically.

There are several important limitations to our study. First, we focus on one form of political

activity only: lobbying. As our review of past research shows, firms have many means of exercising

influence. We have touched on but one of many. Informal lobbying and connections, illegal bribery,

threats of exit or promises of new employment, campaign contributions and PACs are all unexplored

here. We assume that all these influence strategies are complements. But if they are substitutes,

then our findings may not approximate the overall activity of MNCs. Second, we focus on individual

firm activity and not trade associations. Past research suggests that this individual activity is most

24

common among MNCs and thus more salient for our research. But more research about MNCs use

of industry-wide collective action would be useful. Finally, we focus on the US alone. But we think

that many of our findings are likely to carry over to other countries. As we claimed above, the

US case for MNC influence may be a hard one to make given the country’s well-institutionalized

and very divided government. Other smaller and poorer countries faced with the resources and

capabilities of these large, global firms may be even more vulnerable to their pressures and hence

more likely to generate MNC political activity.

Do MNCs have outsized influence over politics? And relative to whom? Domestic firms, the

public and the median voter, or other interest groups? Our data cannot directly answer this critical

question. We can say that they have greater means and seem to use them to exert more influence

than other firms, even big domestic ones. But are they more able to convert these means into success

politically? Again our data cannot give a direct answer. But the direction of US foreign economic

policy in the past decades suggests they have been very powerful. The lowering of trade barriers

via the GATT/WTO and various preferential trade agreements, the opening of capital markets and

signing of bilateral investment treaties and economic agreements with investment protections, and

the harmonization of regulations in many areas in preferential trade agreements are all policies that

the US government has pursued actively and ones that MNCs have championed. MNC preferences,

versus those of purely domestic firms, seem to be very congruent with much of recent American

foreign economic policy. Rodrik (2018) claims, for example, that preferential trade agreements are

tools for MNCs: “Trade agreements are shaped largely by rent-seeking, self-interested behavior on

the export side. Rather than rein in protectionists, they empower another set of special interests

and politically well-connected firms, such as international banks, pharmaceutical companies, and

multinational corporations” (as cited in Blanga-Gubbay, Conconi, and Parenti 2019, p. 4). Indeed,

some have claimed that MNCs are ruling the world, as many nations have adopted similar policies

fostering globalization. Also notable is how the Trump administration’s policies that have rolled

back America’s support for globalization have been met with great concern by many MNCs. Our

research may then reveal one of the mechanisms for the powerful political influence of these global

firms over the years.

25

References

Akcigit, Ufuk, Salom´e Baslandze, and Francesca Lotti. 2018. “Connecting to Power: Political Con-

nections, Innovation, and Firm Dynamics.” NBER Working Paper Series, No. 25136. Available

from https://www.nber.org/papers/w25136.

Allee, Todd, and Clint Peinhardt. 2011. “Contingent Credibility: The Impact of Investment Treaty

Violations on Foreign Direct Investment.” International Organization 65 (3): 401–432.

Alt, James E, Jeffry A Frieden, Michael J Gilligan, Dani Rodrik, and Ronald Rogowski. 1996.

“The Political Economy of International Trade: Enduring Puzzles and an Agenda For Inquiry.”

Comparative Political Studies 29 (6): 689–717.

Ansolabehere, Stephen, John M. de Figueiredo, and James M. Snyder. 2003. “Why is There so

Little Money in U.S. Politics?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 17 (feb): 105–130.

Austen-Smith, David, and John R. Wright. 1994. “Counteractive Lobbying.” American Journal of

Political Science 38 (1): 25–44.