Minnesota State University Moorhead Minnesota State University Moorhead

RED: a Repository of Digital Collections RED: a Repository of Digital Collections

Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies

Spring 5-12-2023

Throwing away the Late Work Penalty Throwing away the Late Work Penalty

Anthony Orttel

anthony[email protected]

Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis

Part of the Secondary Education Commons

Researchers wishing to request an accessible version of this PDF may complete this form.

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Orttel, Anthony, "Throwing away the Late Work Penalty" (2023).

Dissertations, Theses, and Projects

. 768.

https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/768

This Project (696 or 796 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a

Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an

authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact

Throwing away the Late Work Penalty

A Quantitative Research Methods Proposal

By

Anthony J Orttel

ED 603

Methods of Research

Master of Science in Curriculum and Instruction

March 2023

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..……3

Brief Literature Review…………………………………………………………………...5

Statement of the Problem………………………………………………………………….5

Purpose of the Study………………………………………………………………………5

Research Question(s)…………………………………………………………………...…6

Definition of Variables……………………………………………………………6

Significance of the Study………………………………………….………………………6

Research Ethics………………………………………….……………………………...…7

Permission and IRB Approval……………………………………………...……..7

Informed Consent……………………………………………………………...…..7

Limitations. ………………………………………….……………………………7

Conclusions………………………………………….………………………………….…8

CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction………………………………………….……………………………….……9

Body of the Review………………………………………….……………………………9

Context………………………………………….…………………………………9

Background on Late Work Penalties …..…………………………………………9

The Purpose for Grading………………………………………….………...……10

Reasons for Late Work…………………………………………………………..12

Penalties for Late Work………………………………………………………….13

Consequences of not Accepting Late Work……………………………………...14

Theoretical Framework……………………………….……………………………….…15

Research Question(s) ……………………………….……………...……………………16

Conclusions……………………………….………………………………………...……16

CHAPTER 3. METHODS

Introduction……………………………….…………………………………………...…17

Research Question(s) ……………………………….…………………………...………17

2

Research Design……………………………….…………………………………………17

Setting……………………………….………………………………………………...…18

Participants……………………………….………………………………………………18

Sampling……………………………….………………………………………...19

Instrumentation……………………………….………………………………………….19

Data Collection……………………………….………………………………….19

Data Analysis……………………………….……………………………………19

Research Question(s) and System Alignment……………………………….…...20

Procedures……………………………….……………………………………………….21

Ethical Considerations……………………………….…………………………………..21

Conclusions……………………………….……………………………………………...21

CHAPTER 4. ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATIONS

Data Collection……………………………………………………...………………...…22

Results………………………………………………………………..………………..…22

Table 1………………………………………………………………………….……..…23

Table 2…………………………………………………………………………..……….24

Data Analysis………………………………………………………………………..…...25

Conclusion………………………………………………………………………...……..28

CHAPTER 5. IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Action Plan………………………………………………………...……………………..29

Plan for Sharing……………………………………………………………………....….30

REFERENCES……………………………….………………………………………………….31

3

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Introduction

Some of the greatest challenges of being a teacher are to find a perfect grading system to

implement and trying to come up with a fair and equitable late work policy (Dueck, 2014;

Knight & Cooper, 2019). There are several benefits and drawbacks teachers must consider while

drafting a late work policy that works well for their classroom. Some teachers make policies on

late work with no room for forgiveness, such as policies that do not accept late work at all, or

ones that cost students a great deal of points on an assignment. Other teachers have no policy

against late work and accept any assignment at any time.

Teachers usually have their reasons for implementing specific policies, for example,

when students can turn in late work without penalty, it can create a backlog of work for the

instructor to go through and grade (Bosch, 2020). When students fall behind in class and are

trying to complete missing work, they often do not put in the necessary effort to understand the

new information and to complete current laboratory work, because they tend to focus on missing

work rather than current work (Bosch, 2020). This can result in missed learning opportunities

and lower test scores (Dueck, 2014). On the other hand, when students can turn in late work

without penalty, it gives them a chance to learn the information without rushing to complete the

assignment before the deadline. It may also provide the needed motivation for students who

would otherwise fail the course, to complete the missing work (Knight and Cooper, 2019).

During this study, the researcher will be investigating the impact of allowing students to turn in

4

late work with no penalty and will particularly focus on the number of missing assignments that

students have at the end of a quarter.

Brief Literature Review

Implementing a fair and equitable grading system is often the responsibility of the

classroom teacher. However, grades cannot be fair and equitable if teachers grade behaviors

instead of their knowledge and application of the content standards (Wormeli, 2005). It is hard to

point the blame at teachers on this issue because many teachers do not fully understand how to

make grading fair and equitable, and many do not even realize that they are grading behaviors

(Wormeli, 2005). The grading of behaviors can be intentional or unintentional. For instance, a

teacher might fail a student on an assignment because they decided not to complete it. Another

teacher might fail a student on that same assignment, even if it was fully complete, on the

grounds that it was handed in late (Dueck, 2014). The literature details many instances of this

kind of unintentional and intentional grading of behaviors, and ultimately calls for an end to

draconian style late work policies.

One study focused on punitive grading policies and how they affected students (Wormeli,

2005). The researcher emphasized that not allowing students to turn in late work does not teach

them accountability. The researcher discouraged grading based on a student's behavior and

warned of the future consequences for the child that it could have, including not getting admitted

into certain colleges, or not being eligible for scholarships. Another study agreed with Womeli’s

(2005) findings and added “the number of grading penalties a student incurs has little effect on

his or her future homework behavior,” (Dueck, 2014). Dueck (2014), argues that punitive

5

grading penalties do not work because they do not teach accountability, and because there are

many more reasons students do not turn in work other than simply being lazy.

Statement of the Problem

For too long, teachers have been grading student behaviors instead of student mastery of

standards (Dueck, 2014; Knight & Cooper, 2019). Some of the graded behaviors include effort,

work completion, work timeliness, attendance, class participation, compliance with rules and

expectations (Knight and Cooper, 2019). If students are graded based on their behaviors instead

of content standards, then there is no way to ensure that students have met the expectations that

have been placed upon them. Furthermore, when students are graded based on behaviors, many

stakeholders inside and outside of the school (e.g., employers, military, and college recruiters,

etc...) cannot accurately predict how a potential candidate may perform in their institution

(college, basic training, customer service, etc...) (Dueck, 2014). This type of grading also could

lead to students not being admitted to college, or a student not scoring a job.

In this study, the researcher will focus on the effects of implementing a penalty-free late

work policy. Specifically, the researcher will search for correlations between a late work policy

that allows students to turn in late assignments with no penalty, and the number of missing

assignments that students have by the end of the quarter. The researcher will also be looking for

correlations between implementing a no-penalty late work policy and student’s average grades.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to examine the effects of implementing a no point deduction

policy for late work, and to particularly focus on the effects this has on the number of missing

assignments students have at the end of a quarter, and the effects it has on their average grades.

6

Too many students are punished with low grades due to the simple behavior of not turning in an

assignment on time. Consequences of these policies reach far beyond high school, and into the

realms of colleges and employment opportunities. If this study finds a positive impact on student

learning and achievement, then it may encourage other teachers to implement similar penalty-

free late work policies.

Research Question(s)

How does implementing a penalty-free late work policy affect the number of missing

assignments at the end of the quarter?

Definition of Variables

The following are the variables of study:

• Independent Variable: The independent variable for this study will be to implement a

penalty-free late-work policy in my classroom.

• Dependent Variable: The dependent variable for this study is the number of late

assignments submitted at the end of the quarter.

Significance of the Study

This study is important to the researcher because it could influence other teachers to take

a more sensitive approach to grading assignments and may encourage them to get rid of or

reduce penalties for late work. This would benefit students of all ages, as well as adults--since

adults had to go through the education system at some point. All students should have access to a

fair and equitable education, and certain behaviors on one particular day should not be on record

7

forever (grades), and they certainly should not dictate what happens to a child's future. Many

teachers realize the benefits and challenges of implementing a fair and equitable grading system,

however, a lot of teachers refuse to try it.

Research Ethics

Permission and IRB Approval. In order to conduct this study, the researcher will seek

MSUM’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval to ensure the ethical conduct of research

involving human subjects (Mills & Gay, 2019). Likewise, authorization to conduct this study

will be sought from the school district where the research project will take place (See Appendix

X and X).

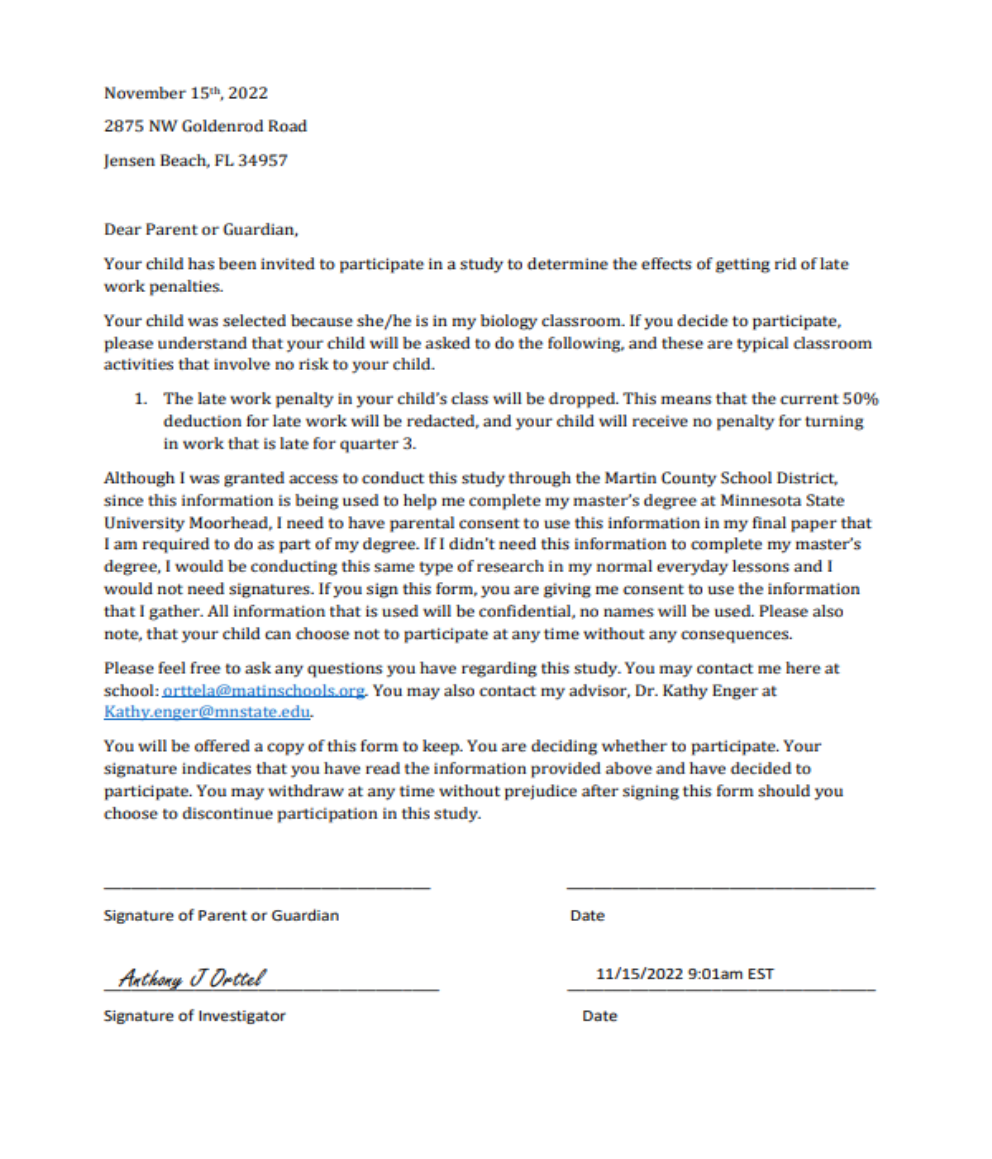

Informed Consent. Protection of human subjects participating in research will be

assured. Participant minors will be informed of the purpose of the study via the Method of

Assent (See Appendix X) that the researcher will read to participants before the beginning of the

study. Participants will be aware that this study is conducted as part of the researcher’s master’s

degree Program and that it will benefit her teaching practice. Informed consent means that the

parents of participants have been fully informed of the purpose and procedures of the study for

which consent is sought and that parents understand and agree, in writing, to their child

participating in the study (Rothstein & Johnson, 2014). Confidentiality will be protected through

the use of pseudonyms (e.g., Student 1) without the utilization of any identifying information.

The choice to participate or withdraw at any time will be outlined both, verbally and in writing.

8

Limitations

There are several possible limitations to this study. This study will be conducted with a

small sample size of ~30 students, over a short period of time--i.e. two academic quarters. The

sample is predetermined by the school (in terms of the classes the researcher was assigned to

teach at the beginning of the year), and only focuses on the limited subject area of biology, as the

students in the sample are biology students and the researcher only teaches biology. This study

also cannot account for students who are absent on a regular basis, or events that take place in

the personal lives of students, that may impact the researchers results.

Conclusions

The researcher believes that this study will encourage teachers to modify their late work

acceptance policies. The researcher hopes that eventually there will be no penalty for submitting

late work, and that schools will shift to standards-based grading, in order to ensure that grades

are being given out fairly and equitably. The researcher also hopes to encourage other teachers

not to grade students based on how they behave in a classroom. In the next chapter, the

researcher will examine literature regarding late work penalties, and the effects they have on

students. The researcher will also lay out a theoretical framework that supports the relevance of

this study.

9

CHAPTER 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction

The dilemma of how teachers should handle late work has been around since the

beginning of public education (Knight & Cooper, 2019). In this chapter, the researcher describes

the late work dilemma, and the implications of lowering grades based on the timeliness of

assignment completion and the effects it has on student learning, accountability, and life after

high school. Purposes for grading, reasons for late work, penalties for late work, and

consequences of not accepting late work are all described. There are several studies that have

examined the effects of implementing penalties for late work that are summarized in this

literature review.

Background on Late Work Penalties

For as long as teachers have been assigning homework, there have been problems with

getting students to complete their assignments on time. Over the years, educators have

implemented numerous late work policies to encourage students to turn in their assignments in a

timely manner. Policies such as taking a few points off for a late assignment, all the way up to

draconian policies where an educator will not consider giving late work a grade have been

implemented, with little to no success (Bosch, 2020). Several studies have been conducted about

how educators handle late work, and the implications that those policies have on students in the

present and in the future.

A study conducted by the National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP)

Bulletin examined the effects that standards-based grading had on student success (Knight &

Cooper, 2019). The study found that allowing students to make multiple attempts at completing

10

an assignment and allowing for flexible due dates without a late penalty, resulted in fewer

missing assignments at the end of the term, and an overall better understanding of the content

standards. The study also found that many educators use late work penalties as a punishment to

teach accountability, not realizing that students often do not perceive these “punishments” as

motivational forces to complete work on time and they certainly do not help them with their

mastery of the standards, nor do they teach accountability (Knight & Cooper, 2019).

The Purpose for Grading

To fully understand the effects that punitive late-work policies have on students; it is

important to examine the purpose for grading in the first place. Multiple studies attempt to

identify the purpose for grading. One thing that all the studies have found is that there is more

than one purpose for grading. To be transparent with all stakeholders, schools should clearly

define their purpose for grading (Feldman & Reeves, 2020). When schools do this, it makes

admissions to colleges fairer, access to scholarships and grants more equitable, and allows

employers to know what to expect from graduates of a particular school—in terms of what

grades they have earned.

According to Anderson (2018), there are three possible reasons for grading; one, to

motivate students to put more effort into their academics, two, to give teachers critical

information about how students are learning and how they can improve their instruction, and

three, to communicate important student-related information to a variety of audiences, from

potential employers to college admission reps. In a study performed in Canada that examined the

purpose for grading, DeLuca (et al., 2017) found similar results, with the additional purposes of

accountability and sorting. Many educators use grades to teach students about accountability, and

many institutions (colleges, employers, prep schools, and high schools) use grades to sort

11

students into various groups. For example, some students could be promoted to the next grade

level based on their grades, while others may be held back. Some students may earn a

scholarship or get accepted into a good school because of their “good” grades, while other

students who did not perform as well may not get those same opportunities.

Knight and Cooper (2019) found that while purposes for grading may be well intended,

many policies are missing the mark, for example, schools may use grades to determine whether a

student has met the required academic standards or not, but there are many non-academic

components to grades that educators also target, such as class participation, compliance with the

rules and expectations, attendance, work completion, and work timeliness. Knight and Cooper

(2019) argue that behaviors and academics should be treated separately, because they are two

separate things. Classroom behavior does not dictate mastery of standards, and mastery of

standards does not control classroom behavior.

Many additional studies, such as (Dueck, 2014; Boleslavsk & Cotton, 2015; Castro, et al.,

2020; Bosch, 2020). have found that grades are often a measure of student behavior, and not

based solely on mastery of concepts. For example, if a student does not participate in class, they

may earn a low mark for the day. If a student was having a rough day, and that was the reason

for them not participating in a classroom activity, the gradebook may reflect that the student did

not meet the standards—however, it would not consider other factors (such as the student having

a bad day), thus, misrepresenting to stakeholders (employers, college admission reps, etc.) what

the student is academically capable of.

Using grading to manage student behaviors also does not take into consideration that

students’ minds are still developing, and neglects the fact that students often act out of impulse,

because they cannot fully understand the long-term implications of their actions (Dueck, 2014).

12

For example, should a student who can show mastery of a concept on an exam, fail an

assignment because they want to play outside with their friends instead of staying indoors and

completing homework? When behaviors are factored into grades, grades become inaccurate and

an unreliable measure of student academic learning (Feldman and Reeves, 2020).

According to Wormeli (2005), “letting the low grade do our teaching is an abdication of

our responsibilities as educators,” (p.17). In other words, if our purpose for grading is punitive in

nature, we are not teaching students to be accountable or responsible. Feedback and assessment

are the best ways to teach accountability to students. Using grades to punish students for

behavior should be avoided at all costs (Knight and Cooper, 2019).

Reasons for Late Work

Several studies have identified reasons why students may turn in their assignments after

the due date. Many students lack time management and organizational skills (Mastrianni, 2015).

With students having up to seven classes to manage their time around (inside and outside of

school), it can be easy to forget when due dates are. It is also very easy for students to get

overwhelmed with the workload that is given to them, and to keep track of late work policies that

vary from teacher to teacher (Santelli et al., 2020).

At the beginning of the Covid-19 Pandemic in 2020, many schools reverted to remote

learning. This put technology into the hands of a lot of students who would have not had access

to it before. Santelli (et al., 2020) argues that since more students have access to technology,

more students will be distracted by the technology, and thus, more assignments will be turned in

late. The argument that an increase to the access of technology by students is contributing to

more late work is also backed up by Mastrianni (2015), who described how students with access

13

to technology are becoming more addicted to it, thus putting in less of an effort on schoolwork,

and more of an effort into using their cellphones.

Mastrianni (2015) claimed that another reason for students turning in late work is due to

procrastination. Santelli (et al., 2020) agreed that procrastination does account for many late

assignments, and poor test performance, however, cautioned educators to be careful when

generalizing students to be procrastinators, noting that they should consider the stressors put onto

students—such as multiple courses, differing due dates for assignments, different late work

policies between instructors, and stressors in their homes. Educators may be quick to label

students as lazy or as procrastinators for not turning in work on time, while failing to realize that

their course is only a small part of a student’s busy day.

Penalties for Late Work

Many educators enforce penalties on students when they submit late work, and their

reasons for enforcing penalties vary. Many educators think that accepting late work is unfair to

other students who have completed their work on time (Santelli et al., 2020) and (Bosch, 2020).

Others feel that accepting late work puts an undue burden on faculty, who may have to go back

and grade something that they thought they were finished grading weeks ago, adding more work

onto their already busy schedules. It should be noted that some school districts mandate late

work penalties, whether the faculty agree with them or not.

Some of the most common late work policies are those in which points are deducted

based on the amount of time an assignment is submitted late. Some examples of late work

policies include the 10/24 policy and the one-point-per-hour policy. With the 10/24 policy,

assignment grades are assessed a 10-point penalty for each 24-hour period they are submitted

late (Bosch, 2020). The problem with the 10/24 policy is that it assesses the same penalty on

14

students regardless of if they are one minute late to submit an assignment, or 23 hours late to

submit an assignment. Bosch (2020) argues that a more fair and equitable late work policy is the

one-point-per-hour policy, because most students who submit late assignments submit them only

a few minutes or a few hours late, not several days late. When he surveyed students at his school,

Bosch (2020) discovered that students perceived the one-point-per-hour policy to be fairer than

the 10/24 policy.

Some educators do not think that students should be penalized for late work. Dueck

(2014), argues that punitive late work policies are not effective because they are measuring a

behavior (turning in an assignment late), versus measuring academic standards. Walstad and

Miller (2016) also agrees that students should not be penalized for late work. They argue that the

discretion that educators have in accepting late work can be helpful to some students, but very

harmful to others. On the other hand, there are several educators who use the “old school”

method, and do not accept late work whatsoever. According to Santelli (2020), most kids

perceive no late work acceptance policies as unfair. It is easy to see how students could get

confused when they go from teacher to teacher, and all their teachers have different late work

acceptance policies.

Consequences of not Accepting Late Work

“A grade is more than a number, it is a quality of life,” (Anderson, 2018). Anderson

(2018) argues that modern grades are built off earlier grading systems that were based on ranking

students instead of rating them. This is part of the reason why there are so many educators that

have differing late work acceptance policies. Many of these policies were built with the mindset

of ranking students, not rating them based on their knowledge of the academic standards. And

with these antiquated policies still in use today, come the consequences associated with them.

15

Grades are still used to sort students. Some students will be accepted into college based on their

“good “grades, while others will be turned away based on their “bad” grades. Having better

grades may mean a better quality of life to some students, and that is why it is important to

ensure that grades are based solely on standards, and not on behaviors (Feldman and Reeves,

2020).

Castro (et al., 2020) acknowledged that there is no perfect solution for the late work

dilemma. Castro (et al., 2020) did mention how during the Covid-19 Pandemic, that in the state

of California, a “do no harm” policy was used when it came to grading work. Teachers were not

allowed to take points off assignments for late work, because students were forced to stay at

home, and not everyone had access to the same resources. Castro (et al., 2020) argued that a

similar policy should be put into place after the Pandemic, to replace antiquated late work

policies. Knight & Cooper (2019) and Dueck (2014), argue that late work penalties are a thing of

the past, and that students should be graded on what they know—not on the behavior of turning

in an assignment on time. Feldman and Reeves (2020) also argued that late homework should not

negatively affect a student’s grade, instead, grades should be based off of what a student can

achieve in class during the school day. This way, equity is insured, and everyone is on a level

playing field.

Theoretical Framework

The research conducted by Richard Ryan and Edward Deci in 1977 led to the Self-

Determination Theory. This theory suggests that in order to grow and develop psychologically,

humans need to feel a sense of autonomy, gain a sense of competence, and have a connection

with, or belong to a group of other people (Patrick & Williams, 2012). When teachers take away

points, or don’t accept late work, solely due to the fact that it is late, then students who have a

16

low sense of self-determination may not complete future assignments because they are stuck in a

self-destructive positive feedback loop because they feel they may have lost control of the

situation. They realize that even if they try hard on an assignment, they will not achieve full

success because they will incur a late penalty. Thus, they may elect not to complete an

assignment. Students lose interest in completing work that they know they won’t be able to finish

on time because of outside factors and end up not completing the assignment because they do not

feel like they have control of the situation, and they certainly do not have hope that they will

succeed on the assignment.

Research Question

How does implementing a penalty-free late work policy affect the number of missing

assignments at the end of the quarter?

Conclusions

There is no perfect way to address the late work dilemma. In each school, there are many

educators with many differing opinions as to how late work should be handled. One thing is

clear; however, schools should have an explicit purpose for grading—and grading policies

should be consistent from teacher to teacher. In the next chapter, the researcher will be exploring

how implementing a penalty-free late work policy will affect the number of missing assignments

at the end of the quarter. If there is a decrease in missing assignments and an increase in overall

grades after implementing such a policy, that might be enough evidence to prove that getting rid

of late work penalties is more positive than negative.

17

CHAPTER 3

METHODS

Introduction

This study was conducted to examine the relationships between getting rid of late work

penalties and the effects it would have on student grade percentages and the number of missing

assignments students have at the end of a quarter. According to Castro et al. (2020), many

teachers implement harsh late work grading penalties that focus on punishing the behavior

(turning in late work) instead of focusing on a students’ mastery of the content. While there are

several ways of handling late work, this study takes a more “radical” approach and examines

what might happen to student grades and the amount of missing work if no late work penalties

are implemented for a grading quarter. In other words, how does implementing a penalty-free

late work policy affect the number of missing assignments at the end of the quarter?

Research Question

How does implementing a penalty-free late work policy affect the number of missing

assignments at the end of the quarter?

Research Design

This study uses a quantitative research design to collect numerical data on the number of

missing assignments students have before and after the implementation of a penalty-free late

work policy. Data is also collected on student grade percentages before and after the

implementation of a penalty-free late work policy. The researcher will not be participating in

class to get a grade, but he will observe the effects this new policy has on his students. The

researcher chose this design because it is the best way to determine the effects of a penalty-free

late work policy.

18

Setting

The setting for this study was a high school biology classroom located in a beach town in

Southeast Florida. The population of the county of where the school is located was over 159,000

individuals in the year 2020, and the school itself has nearly 2,000 students--which is considered

medium by Florida Standards. The main industries in the town are marine (fishing, fish products,

water sports, recreation, etc...) and tourism and hospitality. According to the Florida Department

of Education (FLDOE), this high school serves students from an economically advantaged area,

where the median household income was over $65,000, and the graduation rate of the high

school students is over 95%. This high school has consistently earned an “A” school rating over

the years. According to the FLDOE, the school scores the lowest on the diversity index; where

71% of students are white, 16% are Hispanic, and 7% are African American. Most students are

not eligible for free and reduced lunches; however it is available for those who qualify.

Participants

Participants from this study were 55 students from two of the researchers' biology classes during

the 2022-2023 school year. One class was the researcher’s period 2 class, and the other was the

researchers period 5 class. All students participating were between the ages of 15 and 17. The

demographics of the classes are 58% male and 41.8% female. The ethnicities of the students are

as follows; 63.6% Caucasian, 27.2% Hispanic, and 9% African American. 21.8% of the

participants receive special education services, and 7% of the students receive high intensity ELL

support.

19

Sampling

The participants were selected based on convenience. Participants selected were chosen

because they were already in the researcher’s classroom, and they were all being taught the same

subject. The research's other classes were electives so they could not easily be added to the

study.

Instrumentation

The instrument used to collect data was the researchers Focus Gradebook Software.

Student data was analyzed using Focus during quarter 2 of the academic year, and once again in

quarter 3 of the academic year after the no-penalty late work grading policy was implemented,

for the purpose of comparison. The researcher also used a notebook to keep track of numbers of

missing assignments at different intervals throughout quarter 3, in order to keep track of any

possible early insights into the new policy.

Data Collection.

To collect data, the researcher will keep all grades and missing assignment statuses

updated on the Focus grading software. The researcher will also make notes of the turn in date of

late assignments for all 55 students and will continually monitor the gradebook for accuracy.

Gradebook data collection will stop on the last day of quarter 3.

Data Analysis.

To analyze the data, the researcher examined the grade percentages and number of

missing assignments of all 55 students in quarters 2 and 3 of the 2022-2023 academic year. The

researcher will compare data from both quarters and look for any significant correlations

between the two.

20

Research Question and System Alignment.

How does implementing a penalty-free late work policy affect the number of missing

assignments at the end of the quarter?

Table 3.1.

Research Question(s) Alignment

1

Research

Paradigm

2

Research

Design

3

Research

Question

4

Variables

5

Instrument(s

)

6

Source(s)

and

expected

Sample

Size

7

Data

Analysis

Quantitative

Correlatio

n

How does

implementi

ng a

penalty-free

late work

policy

affect the

number of

missing

assignment

s at the end

of the

quarter?

DV: The number

of late

assignments

submitted at the

end of the

quarter.

IV: Implementin

g a penalty-free

late work policy

Focus

Grading

Software.

Research

Notebook

High

School

Biology

Classroom.

Sample

Size: 55

students in

total

between

my two

on-level

biology

courses.

At the end

of quarter

3, grades

will be

compared

between

quarter 2

and quarter

3. The

researcher

will look

for any

correlation

s of the

number of

missing

assignment

s between

the two

quarters

that are

being

compared.

.

21

Procedures

The researcher is the classroom teacher in this study. The researcher will record the

number of missing assignments between all 55 students during quarter 2 of the 2022-2023 school

year. The researcher will then implement a penalty-free late work policy for all of quarter 3. At

the end of quarter 3, the researcher will compare the number of missing assignments in quarter 3

to the number of missing assignments in quarter 2, between all 55 students. The researcher will

then determine if there was any effect on missing assignments, based on the new penalty-free

late work policy.

Ethical Considerations

All students participating in this study were under the age of 18, and therefore were given

informed consent letters to take home to be signed by their parents/guardians. Students were

informed that they can stop participating in the study at any time. Students and their guardians

were ensured that all students' names will remain anonymous. There should be no need for work

samples since the researcher is pulling grades directly from the gradebook, but if there was a

need for work samples, any student names would be blurred out.

Conclusions

This chapter focused on the methodology of the research completed on eliminating late-

work penalties in the classroom. The results of this research will be reviewed in the next chapter.

22

ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION

Chapter 4

The purpose of this study is to examine the effects of implementing a no point deduction

policy for late work, and to particularly focus on the effects this has on the number of missing

assignments students have at the end of a quarter, and the effects it has on their average grades.

Many teachers deduct points for late work, which could possibly deter students from trying to

complete late assignments at all. The researcher would like to determine if policies that deduct

points from late work should be a thing of the past, or if they still hold some value in today's

society.

Data Collection

To collect data for this study, the researcher used the Focus gradebook software and

examined the grade averages and number of missing assignments at the end of two academic

quarters. During the first quarter, the researcher deducted half of the point value on assignments

that were turned in late, which was the standard procedure at the school. During the second

quarter of the experiment, the researcher instituted a policy that would allow students to turn in

work as late as they wanted to, with no point deduction.

Results

RQ 1: How does implementing a penalty-free late work policy affect the number of missing

assignments at the end of the quarter?

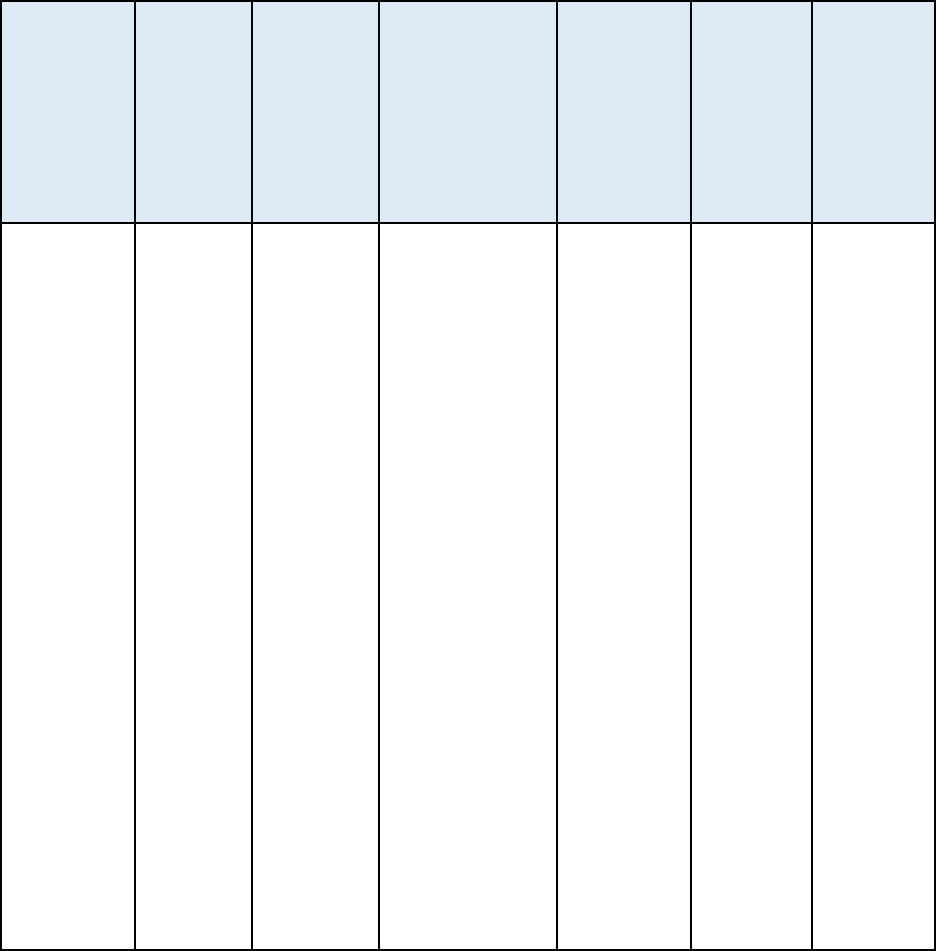

Table 1 shows the number of missing assignments that each student in the researcher's

first period biology class had at the end of academic quarter two and academic quarter three,

before and after the penalty-free late work policy went into place. Table 1 also shows the average

23

percentage at the end of both quarters for each student, before and after the penalty-free late

work policy went into place. The researcher felt that it was important to include both the number

of missing assignments and the average percentage that each student earned in class, in order to

paint a complete picture of student performance. Data table 1 also shows the percent grade

change between both academic quarters and the average number of missing assignments at the

end of both quarters.

Table 1

Period 1 Quarter Two and Three Academic Data

Student

Q2. Missing

Assignments

Q3. Missing

Assignments

Q2 Grade %

Q3 Grade %

% Grade

Change

1

0

0

94

92

-2

2

0

2

81

95

14

3

6

0

92

93

1

4

1

0

96

95

-1

5

1

1

93

96

3

6

1

1

90

94

4

7

1

0

92

90

-2

8

2

1

88

85

-3

9

7

6

65

73

8

10

1

0

92

91

-1

11

4

0

91

93

2

12

6

2

65

75

10

13

7

2

68

75

7

14

3

0

87

88

1

15

1

0

82

79

-3

16

8

4

79

83

4

17

1

1

91

96

5

18

1

2

95

90

-5

19

5

0

81

75

-6

20

0

0

92

97

5

21

0

0

91

94

3

22

0

0

94

98

4

Average

2.54

1

86.3181

88.5

2.2

24

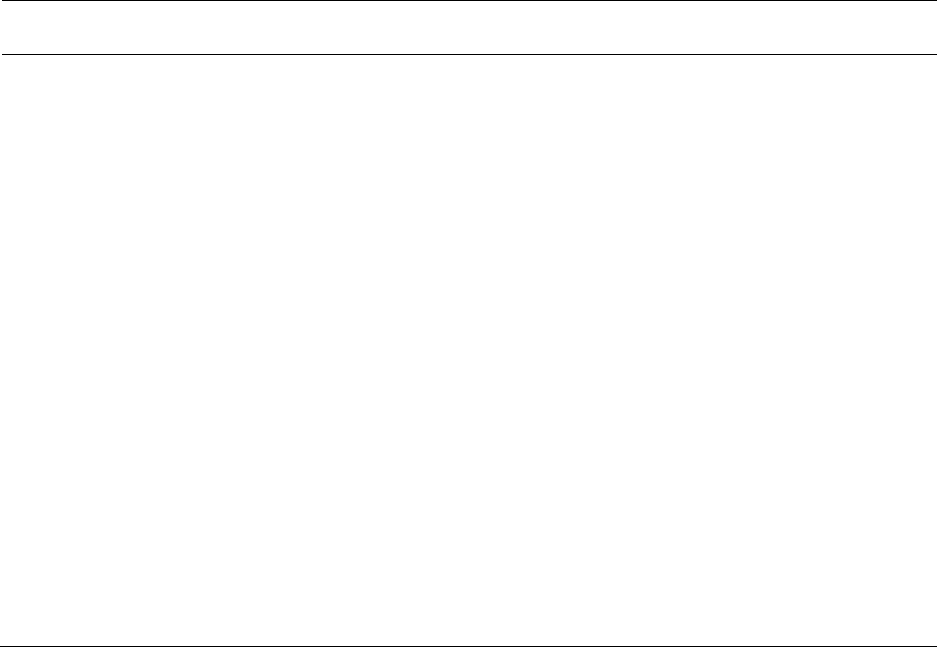

Table 2 shows the number of missing assignments that each student in the researcher's second

period biology class had at the end of academic quarter two and academic quarter three, before

and after the penalty-free late work policy went into place. Table 2 also shows the average

percentage at the end of both quarters for each student, before and after the penalty-free late

work policy went into place. Data table 2 also shows the percent grade change between both

academic quarters and the average number of missing assignments at the end of both quarters.

Table 2

Period 2 Quarter Two and Three Academic Data

Student

Q2. Missing

Assignments

Q3. Missing

Assignments

Q2 Grade %

Q3 Grade %

% Grade

Change

1

13

16

46

41

-5

2

4

3

75

73

-2

3

2

4

71

72

1

4

6

0

70

60

-10

5

5

2

68

76

-8

6

0

1

80

83

3

7

5

6

73

60

-13

8

6

3

63

61

-2

9

3

5

52

61

9

10

15

17

56

27

-29

11

3

1

83

79

-4

12

7

6

66

62

-4

13

8

13

72

54

-18

14

10

9

46

53

7

15

8

12

70

48

-22

16

3

4

74

78

4

17

9

5

76

71

-5

18

16

16

43

45

2

19

6

7

73

55

-18

20

6

4

76

70

-6

21

4

5

61

60

-1

Average

6.62

6.62

66.38

61.38

-5

25

Data Analysis

The results of the study varied widely between the two experimental groups of students.

Both classes received the same instruction during the observed academic quarters in this study.

Both classes were moving through the content at a similar pace, and both classes were assigned

25 assignments during each quarter. In the gradebook, unit tests were worth 50% of the

cumulative grade, quizzes and labs were worth 30%, and homework / classwork was worth 20%.

There were an equal number of tests in both quarters, all with equal point values. Even though

several controls existed in this experiment between the classes, the researcher believes it is worth

breaking down both classes individually, since there is such a difference between the classes in

the results.

Period 1 Data Analysis

The results from the researcher’s period one class generally supports the idea that when

there is no penalty for late work, students will perform better academically. The average grade

earned during quarter two while the penalty was still in place was 86.3%. After the penalty was

removed, the average grade at the end of quarter three was 88.5%, an increase of 2.2%. Each

student had, on average, 2.5 missing assignments during the second quarter. At the end of the

third quarter, the average dropped to 1 missing assignment.

Two students showed an increase of more than 10% between quarter two and three.

Overall, 14 students showed a gain in their grade between quarter two and three, and eight

students showed a decline. It is worth noting that none of the eight students who showed an

academic decline during this time period fell by more than a letter grade. Similarly, only two

students who showed an academic gain, actually gained more than one letter grade. It should also

26

be noted that most of the students in this experimental group did not finish quarter two with

many missing assignments.

One idea for the rise in academic performance and drop in number of missing

assignments between the two quarters could be because the school that the researchers’ students

go to, splits up students by ability level. All of the students in this experimental group were 9th

graders and were high academic achievers. These students generally understand the importance

of education, and many of them have their eyes set on attending college. The students know that

if they want to go to a good college, they need to perform well in high school, and the extra time

they were given to work on assignments could have allowed them to complete them, at a pace

more conducive to the student’s ability and schedule.

There are several possible reasons why students performed better during quarter three

than quarter two. For example, many of the students in this group come from wealthy families,

and supportive homes. Education is valued, and pressure is placed on students to perform well

academically. Many of the kids in this group have above average time management skills, and all

of the students use a planner to keep track of their assignments. More than a quarter of the

students in this group are school choice students, meaning that they need to do well academically

to stay enrolled in this district.

Period 2 Data Analysis

The results from the researchers’ period two class do not support the idea that when there

is no penalty for late work, students will perform better academically. The average grade of the

entire class earned during quarter two while the late work penalty was still in place was 66.3%.

After the penalty was removed, the average grade at the end of quarter three was 61.3%, a

decrease of 5%. Each student had, on average, 6.6 missing assignments during the second

27

quarter. At the end of the third quarter, the average remained unchanged, at 6.6 missing

assignments.

Of the 21 students in the researchers’ class, only six showed academic gains between the

two quarters. 15 students showed a drop in their grade averages, and of those 15, six showed an

academic decrease of 10% or more--which is a whole letter grade. It should be noted that the

majority of students in this group ended quarter two with several missing assignments, and that

there was not a meaningful difference in the number of missing assignments at the end of quarter

three.

The students in this group are all 10th graders, who are academically behind many of

their peers in other classes. Many of the students in this group are on IEPs for learning

disabilities, and many of the students in this group do not come from as wealthy backgrounds as

some of their peers in other classes do, and many are lacking an academic support structure at

home. Many of these students come from blue collar families, and many of the families do not

place the same level of importance on education as some other families.

A possible reason for the decline in performance of this experimental group could be that

they are not as good at organizing and planning their time as their peers in the researchers’

period one class. Many of the students did not start working on their assignments until after they

were due. It did not take long before several of the students started falling behind on work. For

example, there were several instances during this study where the researcher observed students

working on past due assignments, while they were supposed to be working on current

assignments. This created a positive feedback loop for the students, where the number of their

missing assignments was rising, and their overall class grades were plummeting. Several of the

students did not make full use of the new (no point deduction for late work) policy and ended up

28

with more missing work at the end of quarter three than the end of quarter two. Many of the

students seemed to get so overwhelmed with work that they stopped trying to complete it, despite

the extra time given. This was not observed in the period one experimental group.

Conclusion

The data collected for this study shows two dramatically different results. The first period

group of students, who were academically higher achievers, showed an overall gain in

performance. They had higher grade averages with the no point deduction for late work policy

than without it. They also had fewer missing assignments on average, than they did with the old

policy. This seems to show that when there is no late work penalty, academic achievement is

higher. The second period group of students showed completely different results. The majority of

the second period group had more missing assignments with the new policy, and they had the

same amount of missing work over both quarters. The variation in results between the two

student groups--especially in class grades-- makes the researcher wonder if the no penalty for

late work policy hurt students more than it helped them. More research is needed on this topic to

make conclusive results.

29

Chapter 5

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

This study was conducted to determine the effects on student achievement, of removing

penalties for late assignments. Many teachers deduct points from students for work that is turned

in late. While usually these point deduction policies are put into place for sincere reasons, many

educators who use them face criticism for punishing student behaviors in the gradebook (turning

in late assignments), instead of purely measuring student academic achievement. This study

showed that among academically high achieving students, a no point deduction for late work

policy may be effective. However, in lower academically achieving classes, this type of policy

could potentially lower achievement. More research is needed to determine the effects of getting

rid of the late work penalty.

Action Plan

This study showed that there is a good possibility that having a no point deduction late

assignment policy could benefit high achieving students. It would allow them to complete

assignments at their own pace since many students lead busy lives with extracurriculars. This

policy would allow students to take their time on assignments, and to process the material better.

The researcher plans to keep this policy in place with his higher achieving classes.

This study also showed that there is a real possibility that not having a late assignment

penalty in place for lower-performing classes could cause more harm than good. The researcher

plans to implement a new version of the late work penalty into his lower-performing classes.

This policy would be drastically different from the previous policy of an automatic 50%

deduction for late assignments. The researcher will let his students in lower-performing classes

turn in late work with no deduction, up until the end of the current academic unit. If late work is

30

turned in after the unit, it will still be accepted for 70% of its original value. The intent of this

policy is to encourage students to complete work, but to stay focused on the current material

being presented in class. The researcher will take notes on how effective the new policies are and

adjust as necessary.

This study is important to other teachers because it shows that draconian-style penalties

for late assignments are not very effective. While educators should try to grade only the

standards met by the students when possible, sometimes, in certain situations, light late work

penalties may be effective at holding students accountable, and improving their overall academic

performance. More research is needed in this area.

Plan for Sharing

The researcher will share the results of this study at his next professional learning

community meeting. The biology faculty have shown an interest in the researchers' study, and

are curious to see the final results, because they are still using the 50%-point deduction late work

penalty. The results of this study may make some of the researchers' coworkers reconsider their

late work policies that they have in place. This research could also potentially help the

researcher's school adopt a new school-wide late work policy that all teachers will use.

31

REFERENCES

Anderson, L. W. (2018). A Critique of grading: Policies, practices, and technical matters.

Education Policy Analysis Archives, 26, 49. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.26.3814

Boleslavsky, R., & Cotton, C. (2015). Grading standards and Education quality. American

Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 7(2), 248–279. https://doi.org/10.1257/mic.20130080

Bosch, B. (2020). Adjusting the late policy: Using smaller intervals for grading deductions.

College Teaching, 68(2), 103–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2020.1753644

Castro, M., Choi, L., Knudson, J., & O'Day, J. (2020, April). Grading policy in the time of

COVID-19: Considerations and implications for equity. American Institutes for Research.

Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://www.air.org/resource/brief/grading-policy-

time-covid-19-considerations-and-implications-equity

DeLuca, C., Braund, H., Valiquette, A., & Cheng, L. (2017, December 21). Grading policies and

practices in Canada: A landscape study. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration

and Policy. Retrieved October 12, 2022, from

https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cjeap/article/view/16331

Demir, M., & Souldatos, I. (2019, November 30). Exploring students' online homework

completion behaviors. International Journal for Technology in Mathematics Education.

Retrieved October 12, 2022, from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1270336

Dueck, M. (2014, March). The problem with penalties. ASCD. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from

https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/the-problem-with-penalties

32

Feldman , J., & Reeves , D. (2020, September). Grading during the pandemic: A conversation.

ASCD. Retrieved October 4, 2022, from https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/grading-during-

the-pandemic-a-conversation

Hanna, R., Linden, L., Welch, K., & Kuzmova, V. (2016). Discrimination in grading. AEA

Randomized Controlled Trials, 146–168. https://doi.org/10.1257/rct.1086

Knight, M., & Cooper, R. (2019). Taking on a new grading system: The interconnected effects of

standards-based grading on teaching, learning, assessment, and student behavior. NASSP

Bulletin, 103(1), 65–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192636519826709

Mastrianni, T. M. (2015, November 30). When the due date is not the “do” date! Learning

Communities Research and Practice . Retrieved October 6, 2022, from

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1112523.pdf

Neeley-Bertrand, D. Q. (2020, August 25). Education policy issues for the COVID-19 ERA.

Aurora Institute. Retrieved October 4, 2022, from https://aurora-

institute.org/blog/education-policy-issues-for-the-covid-19-era/

Santelli, B., Robertson, S. N., Larson, E. K., & Humphrey, S. (2020). Procrastination and

delayed assignment submissions: Student and faculty perceptions of late point policy and

Grace. Online Learning, 24(3). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v24i3.2302

Sun, X.-L. (2017). An action research study from implementing flipped classroom model in

professional English teaching and learning. Proceedings of the 3rd Annual International

33

Conference on Social Science and Contemporary Humanity Development, 1–12.

https://doi.org/10.2991/sschd-17.2017.63

Walstad, W. B., & Miller, L. A. (2016). What's in a grade? grading policies and practices in

principles of Economics. The Journal of Economic Education, 47(4), 338–350.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2016.1213683

Wormeli, R. (2005, November 30). Accountability: Teaching through assessment and feedback,

not grading. American Secondary Education. Retrieved October 12, 2022, from

https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ746326

34

APPENDIX A: INFORMED CONSENT FORM

35

APPENDIX B: IRB APPROVAL LETTER

36

37

APPENDIX C: MARTIN COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT APPROVAL LETTER