667

Primary Ameloblastoma of the Sinonasal Tract

A Clinicopathologic Study of 24 Cases

BACKGROUND.

Ameloblastomas are locally aggressive jaw tumors with a high pro-

Duane R. Schafer,

D.D.S., CDR, DC, USN

1

pensity for recurrence and are believed to arise from the remnants of odontogenic

Lester D. R. Thompson,

M.D., LCDR, MC,

epithelium. Extragnathic ameloblastomas are unusual and primary sinonasal tract

USNR

2

origin is extraordinarily uncommon.

Brion C. Smith,

D.D.S., LTC, DC, USA

1

METHODS.

Twenty-four cases of ameloblastoma confined to the sinonasal tract

Bruce M. Wenig,

M.D.

2

were retrieved from the Otorhinolaryngic-Head & Neck Pathology and Oral-Maxil-

lofacial Pathology Tumor Registries of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology

1

Department of Oral-Maxillofacial Pathology,

between 1956 and 1996.

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washing-

ton, DC.

RESULTS.

The patients included 5 females and 19 males with an age range of 43–

81 years, with a mean age at presentation of 59.7 years. The patients presented

2

Department of Endocrine and Otorhinolaryn-

with an enlarging mass in the maxillary sinus or nasal cavity (n Å 24), sinusitis (n

gic-Head & Neck Pathology, Armed Forces Insti-

tute of Pathology, Washington, DC. Å 9), or epistaxis (n Å 8). Unilateral opacification of the maxillary sinus (n Å 12)

was the most common radiographic finding. Histologically, the tumors exhibited

the characteristic features of ameloblastoma, including peripherally palisaded co-

lumnar cells with reverse polarity. The majority of the tumors showed a plexiform

growth pattern. Fifteen tumors demonstrated surface epithelial derivation. Surgical

excision is the treatment of choice, ranging from conservative surgery (polypec-

tomy) to more aggressive surgery (radical maxillectomy). Five patients experienced

at least 1 recurrence, usually within 1 year of initial surgery. With follow-up inter-

vals of up to 44 years (mean, 9.5 years), all 24 patients were alive without evidence

of disease or had died of unrelated causes, without evidence of disease.

CONCLUSIONS.

Primary ameloblastoma of the sinonasal tract is rare. In contrast

to their gnathic counterparts, sinonasal tract tumors have a predilection for older

age men. Therapy should be directed toward complete surgical resection to prevent

Presented at the American Academy of Oral and

local tumor recurrence. Cancer 1998;82:667–74. q 1998 American Cancer Society.

Maxillofacial Pathology Annual Meeting, Van-

couver, British Columbia, Canada, May 3–7,

1997.

KEYWORDS: ameloblastoma, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, treatment, prognosis.

The authors wish to thank Drs. Dennis K. Hef-

A

fner and Harvey P. Kessler for their critical re-

meloblastomas are locally aggressive jaw tumors with a high pro-

pensity for recurrence that are believed to arise from remnants of

view of the article.

odontogenic epithelium, lining of odontogenic cysts, and the basal

layer of the overlying oral mucosa.

1

Suggested sources for the odonto-

Address for reprints: Duane R. Schafer, D.D.S.,

CDR, DC, USN, National Naval Dental Center,

genic epithelium include cell rests of the dental lamina, a developing

Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology,

enamel organ, the lining of an odontogenic cyst, basal cells of oral

8901 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda, MD 20889-

mucosa, or heterotopic embryonic organ epithelium.

1

Ameloblasto-

5602.

mas can occur in either the maxilla or mandible at nearly any age,

but most frequently are discovered as a painless expansion in the

The opinions or assertions contained herein are

the private views of the authors and are not to

mandible of patients in their 20s –40s.

2

The age range is broad and

be construed as official or as reflecting the

the mean age of occurrence has varied from 35–45 years.

3

Gender or

views of the Department of the Navy, Depart-

race predilection in gnathic ameloblastomas has not been demon-

ment of the Army, or the Department of De-

strated.

fense.

Approximately 15–20% of ameloblastomas have been reported

to originate in the maxilla

4–6

with just 2% arising anterior to the pre-

Received May 23, 1997; revision received Au-

gust 18, 1997; accepted August 18, 1997.

molars.

3

There are numerous studies documenting the presence of

q 1998 American Cancer Society

/ 7bb2$$0788 01-24-98 11:03:42 canal W: Cancer

668 CANCER February 15, 1998 / Volume 82 / Number 4

ameloblastomas within the sinonasal cavity.

7–25

In the patient’s race was documented in 21 of the 24 cases.

There were 19 whites and 2 African-Americans.majority of these reports, the tumor was found to have

originated from the maxilla.

7–12,15,21– 23,25

However, rare The patients usually presented with a mass lesion

and nasal obstruction (n Å 15). Additional signs andcase reports document true primary sinonasal amel-

oblastomas without connection to gnathic sites.

13,14,16–20

symptoms included sinusitis (n Å 9), epistaxis (n Å 8),

facial swelling, dizziness, and headaches. The durationIt is due to the rarity of primary sinonasal tract amel-

oblastoma that this study was undertaken. Our goal was of symptoms ranged from 1 month to several years.

Nine of the 24 ameloblastomas involved only the nasalto better characterize the clinicopathologic features of

sinonasal tract ameloblastomas and to determine the cavity (including the nasal septum, lateral wall, middle

or superior turbinate), 6 tumors were confined to theprobable histogenesis of this tumor. To the best of our

knowledge, this represents the single largest report of paranasal sinuses (maxillary, frontal, ethmoid, or

sphenoid) and 9 involved both the nasal cavity andprimary sinonasal tract ameloblastomas.

the paranasal sinuses at presentation.

In contrast to the characteristic multilocular and

MATERIALS AND METHODS

radiolucent presentation of ameloblastomas within

Twenty-four cases of ameloblastoma with primary

the jaws, the sinonasal lesions most often were de-

involvement of the sinonasal tract were retrieved from

scribed radiographically as solid masses or opacifica-

the files of the Otorhinolaryngic-Head & Neck Pathol-

tions filling the nasal cavity, maxillary sinus, or both

ogy and Oral-Maxillofacial Pathology Departments of

(Fig. 1A) Bone destruction, erosion, and remodeling

the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP). These

(remnant of bony shell delimiting the lesion as it grew)

cases represent consultative material submitted be-

was noted in a minority of cases (Fig. 1B). Primary

tween 1956 and 1996 from military, Veterans Adminis-

origin in, or continuity with, the maxillary alveolar pro-

tration, and civilian hospitals. Of 19,658 sinonasal tract

cess could not be demonstrated in any of the cases

tumors seen in consultation between 1970 and 1996,

examined.

21 (0.11%) were diagnosed as ameloblastomas. In con-

trast, ameloblastomas comprised 43.1% of all oral cav-

Pathologic Features

ity, mandibular, and maxillary odontogenic cysts or

On gross examination, the tissue specimens ranged

tumors accessioned to the AFIP over the same time

in size from several millimeters to 9.0 cm in greatest

period. Hematoxylin and eosin stained histologic

aggregate dimension. Although several of the lesions

slides were reviewed with characteristic histologic fea-

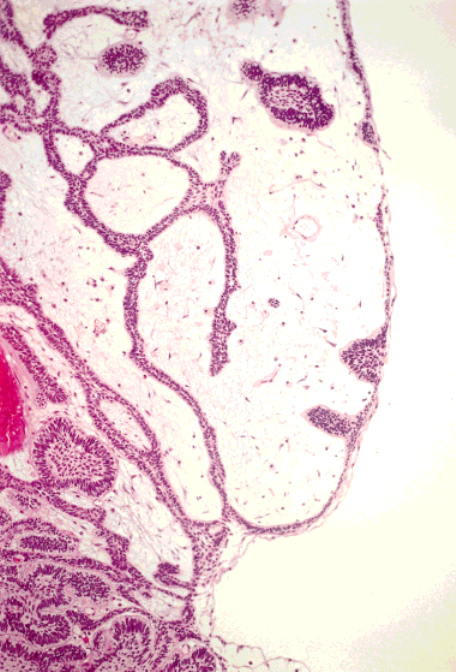

confined to the nasal cavity had retained a polypoid

tures,

26

precluding the necessity for histochemical, im-

appearance (Fig. 2), most of the tissue had been frag-

munohistochemical, or electron microscopic studies.

mented during surgical harvest. The tissue most fre-

Clinical and demographic data were summarized from

quently was described as predominantly solid in ap-

the admitting history, physical examination, radio-

pearance with glistening gray-white, pink, or yellow-

graphic study reports, and pathology requisitions pro-

tan color and a consistency varying from rubbery to

vided by the contributing facilities. Follow-up data re-

granular. The lesions were not described as cystic. Re-

garding patient outcome was obtained wherever pos-

sidual bone of the sinonasal cavity was present in a

sible. This included 1) a description of the treatment

number of the specimens.

rendered (both initial and subsequent, whether sur-

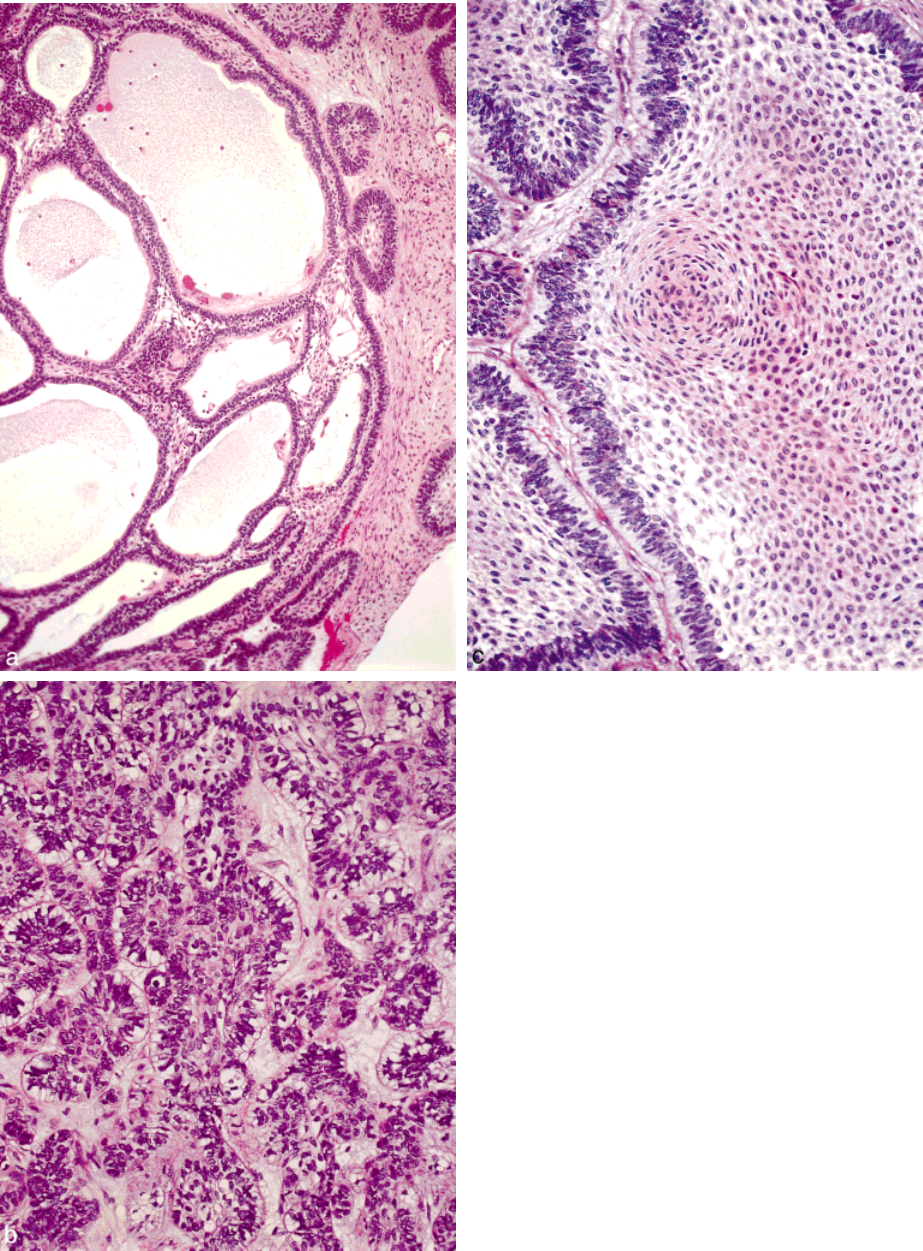

By light microscopic examination, the plexiform

gery, radiation, or chemotherapy); 2) radiographic or

pattern, comprised of a network of long anastomosing

clinical evidence to verify the site of origin; 3) recur-

cords of odontogenic epithelium, was the sole or pre-

rence data; and 4) morbidity for all cases. Attention

dominant histologic pattern in 22 of 24 cases (92%)

was centered on the review of available imaging stud-

(Fig. 3A). The epithelial strands are bounded at the

ies and/or radiology reports to determine the exact

periphery by a layer of columnar cells exhibiting hyp-

anatomic location and extension of the tumor.

erchromatic, palisaded, and reverse polarized nuclei,

along with subnuclear cytoplasmic vacuolization (Fig.

3B). The stellate reticulum-like component associated

RESULTS

Clinical

with the other patterns of ameloblastoma often is less

conspicuous in association with the plexiform histo-The clinical features are detailed in Table 1. In brief,

the patients included 19 males and 5 females, demon- logic type. The acanthomatous pattern, characterized

by squamous metaplasia and keratin formation of thestrating a male predilection of 3.8:1. The age at presen-

tation ranged from 43–81 years, with an overall mean central portions of the epithelial islands, was the next

most common histologic pattern observed, but wasage at presentation of 59.7 years. This average age was

approximately about 15–25 years later than in patients limited to a secondary or focal component (Fig. 3C).

In two patients, the tumor presented with a predomi-with ameloblastoma occurring within the jaws.

3

The

/ 7bb2$$0788 01-24-98 11:03:42 canal W: Cancer

Sinonasal Tract Ameloblastomas/Schafer et al. 669

TABLE 1

Clinical Information and Follow-up

Age Predominant

Case (yrs) Gender Clinical presentation Location histologic type Recurrence Follow-up interval

1 43 F Nasal obstruction and Left nasal cavity and Plexiform 3 (at 1, 2 and 3 yrs) Alive, NED, 44 yrs

epistaxis with maxillary sinus

paresthesias

2 47 M Nasal obstruction Right maxillary sinus Plexiform 3 (at 1, 3 and 7 yrs) Dead, NED, 23 yrs

3 50 F Epistaxis Left posterior nasal cavity Plexiform N/A LTF

4 65 M Nasal obstruction and Left nasal cavity Follicular 1 (at 1 yr) Alive, NED, 16 yrs

sinusitis

5 66 M Nasal obstruction and Right nasal cavity Plexiform None Alive, NED, 7 yrs

sinusitis

6 62 F Nasal obstruction with Left nasal cavity Plexiform None Alive, NED, 16 yrs

polypoid mass

7 57 M Nasal obstruction with Left nasal cavity Plexiform None Dead, NED, 10 yrs

sinusitis

8 63 M Epistaxis Right nasal cavity Plexiform None Alive, NED, 10 yrs

9 61 M Epistaxis and polypoid Left nasal cavity and Plexiform 1 (13 yrs) Alive, NED, 14 yrs

mass maxillary sinus

10 70 M Nasal obstruction with Left nasal cavity, ethmoid Plexiform None Alive, NED, 11 yrs

sinusitis and maxillary sinus

11 55 M Nasal obstruction and Right nasal cavity, ethmoid Plexiform None Alive, NED 11 yrs

epistaxis and maxillary sinus

12 62 M Nasal obstruction and Left nasal septum, ethmoid Plexiform None Alive, NED, 9 yrs

epistaxis and maxillary sinus

13 72 M Sinusitis Right maxillary sinus Plexiform None Alive, NED, 6 yrs

14 61 M Sinusitis Right nasal cavity and Plexiform 2 (at 10 and 20 yrs) Alive, NED, 24 yrs

maxillary sinus

15 81 M Nasal obstruction Right nasal cavity Plexiform None Alive, NED, 3 yrs

16 50 M Sinusitis and headaches Left maxillary and sphenoid Plexiform None Dead, NED, 2 yrs

sinuses

17 58 M Nasal obstruction and Left nasal cavity and Plexiform None Alive, NED, 2 yrs

epistaxis maxillary sinus

18 62 M Sinusitis Left nasal cavity Plexiform None Alive, NED 2 yrs

19 53 M Facial swelling Right ethmoid and Plexiform None Alive, NED, 2 yrs

maxillary sinus

20 45 F Nasal obstruction Left maxillary sinus Plexiform None Alive, NED, 2 yrs

21 45 F Eye tearing Left nasal cavity, ethmoid Plexiform None Alive, NED, 2 yrs

and frontal sinuses

22 59 M Nasal obstruction with Left nasal cavity and Follicular None Alive, NED, 1 yr

mass maxillary sinus

23 71 M Nasal obstruction, Left maxillary and frontal Plexiform None Alive, NED, 1 yr

epistaxis, and sinusitis sinus

24 74 M Polypoid mass Right nasal cavity Plexiform None Alive, NED, 1 yr

M: male; F: female; NED: no evidence of disease; N/A: nonapplicable; LTF: lost to follow-up.

nantly follicular histologic pattern characterized by is- ratory epithelium in areas adjacent to the ameloblas-

tomatous proliferation, and a mixed chronic inflam-lands of epithelium resembling enamel organ epithe-

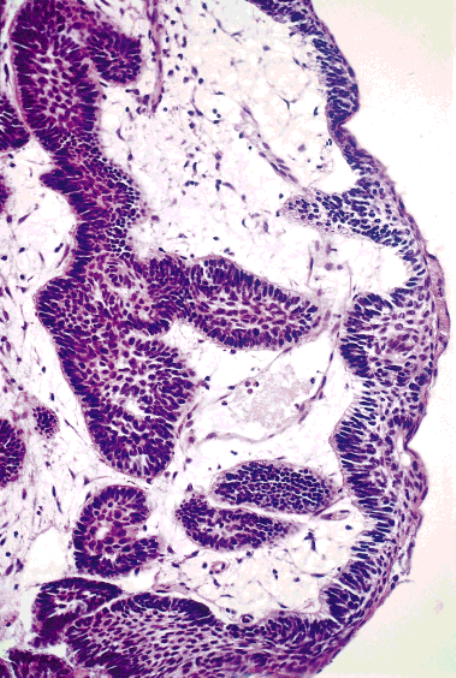

lium. In 15 cases, the ameloblastomatous proliferation matory cell infiltrate with edematous changes within

the lamina propria.could be observed arising in direct continuity with the

intact sinonasal surface mucosal epithelium (Fig. 4).

In the remaining nine cases, the surface epithelium

Treatment and Prognosis

Surgical excision was the treatment of choice in allwas not identifiable due to ulceration or sampling,

precluding the identification of an association be- cases. The type and extent of surgery varied per indi-

vidual case and encompassed conservation surgerytween the ameloblastomatous proliferation and the

sinonasal surface epithelium. (i.e., polypectomy) and more aggressive surgical pro-

cedures, including Caldwell-Luc resection, lateral rhi-Other histologic changes identified included the

presence of squamous metaplasia of the surface respi- notomy, and partial or radical maxillectomy. Radiation

/ 7bb2$$0788 01-24-98 11:03:42 canal W: Cancer

670 CANCER February 15, 1998 / Volume 82 / Number 4

FIGURE 1.

(A) (Case 23). Com-

puted tomography (CT) scan show-

ing an ameloblastoma confined to

the maxillary sinus and nasal cav-

ity. Radiographic survey and surgi-

cal exploration confirmed an intact

sinus floor. (B) (Case 18): Coronal

CT scan of a large ameloblastoma

filling the entire left maxillary sinus

and nasal cavity with bony erosion

of the lateral sinus wall and orbital

floor.

was used in conjunction with maxillectomy in the most positively with complete surgical eradication

when performed in conjunction with thoroughly de-treatment of one patient (Case 2) after the third recur-

rence. Five patients (21%) experienced at least 1 recur- tailed radiographic imaging.

Follow-up was available for 23 of 24 patientsrence. Recurrence of the tumor generally occurred

within 1 to 2 years of the initial procedure but 1 patient (96%), all of whom were either alive without evidence

of disease or had died of unrelated causes without(Case 9) did not experience recurrence until 13 years

after his initial surgery. The histologic appearance of evidence of recurrence. Follow-up periods ranged

from 1–44 years (average, 9.5 years). One patient (Caseall recurrent tumors was identical to that of the pri-

mary neoplasm. Overall treatment success correlated 3) was lost to follow-up.

/ 7bb2$$0788 01-24-98 11:03:42 canal W: Cancer

Sinonasal Tract Ameloblastomas/Schafer et al. 671

staxis.

13,14,16–20

Our findings parallel those of the litera-

ture with the average age at presentation in the late 6th

decade of life (59.7 years) and a clinical presentation

of sinonasal-related symptoms, including obstruction

and epistaxis. None of our patients presented prior to

the fifth decade of life and almost all the patients were

men. In contrast to sinonasal tumors, ameloblastomas

of the oral cavity typically occur in younger age pa-

tients (15 –25 years younger) without gender predilec-

tion. We are unsure why the sinonasal cavity amel-

oblastomas show a preference for older age men. The

gender predilection most likely is a chance occurrence.

An explanation for the older age at onset could be that

the sinonasal ameloblastomas require a longer period

of time before attaining sufficient size to present with

symptoms. These tumors may have been present at

an earlier age but remain clinically silent or produce

nonspecific symptoms (e.g., sinusitis) until they are

large enough to become clinically evident. This is en-

tirely speculative but we do not have another explana-

tion for the unusual demographics associated with si-

nonasal ameloblastomas.

The embryologic derivation of the sinonasal tract

and odontogenic apparatus is closely related. The si-

nonasal tract arises from the ectodermally derived na-

sal pits that invaginate to cover the oronasal mem-

brane, conchae, primary and secondary palatine pro-

cesses, and diverticula of the lateral nasal wall. The

odontogenic apparatus is a combination of an endo-

FIGURE 2.

Proliferating cords of ameloblastic epithelium imperceptibly

phytic proliferation of the basal layer of the ectoder-

blend with the surface epithelium. The polypoid architecture and loose

mally derived oral cavity epithelium and the mesoder-

myxoid stroma resemble an inflammatory polyp.

mally derived mesenchyme.

30,31

The sinonasal tract

and oral cavity communicate freely until closure of

the palatine shelves. Although hypothetical, it appears

quite likely that this embryologic approximation

DISCUSSION

Ameloblastomas are epithelial-derived odontogenic allows the sinonasal tract mucosa either to incorporate

odontogenic epithelium or to acquire cells capable oftumors that typically originate in jaw bones, primarily

involving the mandible and less often the maxilla.

2

odontogenesis during development.

The epithelial source of origin for gnathic amel-Ameloblastomas originating separate from normally

situated odontogenic epithelium represent a rare oc- oblastomas still is being debated.

1,27,32–34

Although

there are extragnathic ameloblastomas that have beencurrence.

27–29

Included among the extragnathic sites

of origin of ameloblastomas is the sinonasal tract. Pre- shown to have arisen from misplaced odontogenic

rests,

10

there was no evidence in any of our cases ofvious documentation of sinonasal tract ameloblasto-

mas include those case reports in which the tumors the ameloblastomas arising from a preexisting odonto-

genic lesion. When considering the possible histogen-were identified as a primary sinonasal tract lesion

without extension from a gnathic ameloblas- esis of these sinonasal tract tumors, parallels can be

made with peripheral ameloblastomas, which also aretoma.

13,14,16–20

In contrast, Tsaknis and Nelson

7

re-

ported 24 cases of maxillary ameloblastomas that in- believed to originate outside the boundaries of the

odontogenic apparatus. In the early 1900s, Bakay

32

cluded patients whose tumors were identified clini-

cally extending into the sinonasal region from a proposed the basal cell layer of the surface epithelium

as the origin of these peripheral ameloblastomas. Ap-primary gnathic origin.

Previous case reports of primary sinonasal tract proximately 50 years later, Stanley and Krogh

27

sug-

gested odontogenic epithelial rests outside the jaw-ameloblastomas indicate that these tumors primarily

affect individuals in the sixth to eighth decades of life bone proper as the progenitor cell for peripheral amel-

oblastomas. In addition, Gardner

33

grouped peripheralpresenting with nasal obstruction, sinusitis, and epi-

/ 7bb2$$0788 01-24-98 11:03:42 canal W: Cancer

672 CANCER February 15, 1998 / Volume 82 / Number 4

FIGURE 3.

(A) Plexiform histologic pattern of ameloblastoma with back-

to-back anastamosing cords of epithelium. (B) The columnar peripheral cells

with reverse polarity of their nuclei is the most common and recognizable

histologic feature of ameloblastoma. Basal cytoplasmic vacuolization and

hyperchromasia of the nuclei are additional features. (C) Squamous metapla-

sia within the center of the ameloblastoma islands is characteristic of the

acanthomatous growth pattern.

/ 7bb2$$0788 01-24-98 11:03:42 canal W: Cancer

Sinonasal Tract Ameloblastomas/Schafer et al. 673

ameloblastomas occurs after some inductive process

on the sinonasal epithelium that results in the neo-

plastic transformation of retained or acquired odonto-

genic cells toward ameloblastomatous differentiation.

The presence of chronic sinusitis and squamous meta-

plasia in the areas adjacent to the ameloblastoma

could be that initiating event. An argument against

this proposal would be that, if true, other types of

odontogenic tumors also should be found as primary

sinonasal tract neoplasms, but the reality is that this

occurs rarely. Alternatively, the ameloblastomatous

epithelium could have originated in the submucosa

and secondarily extended to involve the surface epi-

thelium rather than originating from this epithelium.

However, we could not identify any cell source, such

as odontogenic dental lamina, within the submucosa

that might represent the source for the development

of these tumors. Furthermore, in our departments’

collective experience, odontogenic remnants rarely, if

ever, are found in sinonasal mucosal tissues. Although

the surface epithelium appears to represent the likely

site of origin, the histogenesis for the primary sinona-

sal ameloblastomas remains unknown.

Given the classic histologic features of these tu-

mors, the differential diagnosis is limited. Of primary

importance is to exclude extension into the sinonasal

tract from a primary gnathic ameloblastoma. The only

other consideration might be a craniopharyngioma.

Craniopharyngiomas arise from Rathke’s pouch in the

area of the pituitary gland or along the developmental

FIGURE 4.

Transition from ciliated respiratory epithelium (right) to an

tract leading to Rathke’s pouch and the pituitary gland.

epithelium with squamous metaplasia from which an ameloblastomatous

Histologically, craniopharyngiomas are epithelial neo-

proliferation at the basal cell layer is observed giving rise to infiltrative

plasms comprised of centrally situated stellate cells

ameloblastoma into the submucosa.

with small nuclei and clear cytoplasm surrounded by

a row of basaloid-appearing columnar cells with polar-

ized nuclei in a palisaded arrangement. Degenerativeameloblastomas with the so-called basal cell carci-

noma of the gingiva, proposing that remnants of den- necrobiotic changes, such as ghost cells and calcifica-

tion, can be identified in the tumor. These featurestal lamina or surface epithelium were the source for

extragnathic ameloblastomas. closely resemble the appearance of gnathic ameloblas-

tomas. However, the clinical features of craniopharyn-In their case report, Woo et al.

34

stated that the

possible origins for peripheral ameloblastoma of the giomas markedly contrast with those of sinonasal tract

ameloblastomas so that the lesions should be readilybuccal mucosa included either pluripotential cells in

the overlying epithelial basal layer or from native or separable.

35

Primary sinonasal tract ameloblastomas are un-ectopic epithelial rests. Woo et al.

34

rejected the origin

was dental lamina rests due to the infrequent, if at all, common tumors. Our findings indicate that amel-

oblastomas can originate in the sinonasal tract withoutoccurrence of these rests in the buccal mucosa. These

authors believed that the peripheral ameloblastomas an association with the gnathic area. These tumors

have a distinct predilection for men in the sixth tomost likely originate from pluripotential cells in the

basal layer of the buccal mucosa, thus reaffirming Ba- eighth decades of life. The signs and symptoms are

those of unilateral nasal obstruction accompanied bykay’s proposition.

32

We concur with Bakay

32

and Woo

et al.

34

As we previously noted, direct continuity with opacification of the adjacent maxillary sinus. The

treatment of choice is complete surgical resection. Ifthe sinonasal surface epithelium was found all of our

cases in which the surface epithelium was identifiable. possible, conservative surgery can be used if an as-

sured complete removal can be performed. Incom-This finding supports a mucosal surface epithelial der-

ivation. Perhaps the development of sinonasal tract plete resection may result in local recurrence. In our

/ 7bb2$$0788 01-24-98 11:03:42 canal W: Cancer

674 CANCER February 15, 1998 / Volume 82 / Number 4

17. Reaume C, Wesley RK, Jung B, Grammer FC. Ameloblastoma

cases, neither distant metastasis nor tumor-related

of the maxillary sinus. Case 31, Part 1. J Oral Surg 1980;38:

deaths occurred. Based on our histologic findings,

435–7.

there is strong evidence to propose origin of these

18. Reaume C, Wesley RK, Jung B, Grammer FC. Ameloblastoma

tumors directly from the sinonasal tract epithelium.

of the maxillary sinus. Case 31, Part 2. J Oral Surg 1980;38:

520–1.

However, further studies are indicated to substantiate

19. Wenig BL, Sciubba JJ, Cohen A, Goldstein A, Abramson AL.

the histogenesis of these tumors.

An unusual case of unilateral nasal obstruction: ameloblas-

toma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1985; 93:426–32.

REFERENCES

20. Pantoja E, Kopp EA, Beecher TS. Maxillary ameloblastoma:

1. Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. Odontogenic tumors. In:

report of a tumor originating in the antrum. Ear Nose Throat

A Textbook of oral pathology. 4th edition. Philadelphia:

J 1976; 55:358–61.

W. B. Saunders Co., 1983:258–317.

21. Komisar A. Plexiform ameloblastoma of the maxilla with

2. Waldron CA. Odontogenic cysts and tumors. In: Neville DW,

extension to the skull base. Head Neck 1984; 7:172–5.

Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE, editors. Oral and maxillo-

22. Bredenkamp JK, Zimmerman MC, Mickel RA. Maxillary

facial pathology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1995:

ameloblastoma. A potentially lethal neoplasm. Arch Otola-

493–540.

ryngol Head Neck Surg 1989;115:99–104.

3. Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ. Odontogenic tumors. In: Oral pathol-

23. Porter J, Miller R, Stratigos GT. Ameloblastoma of the max-

ogy: clinical-pathologic correlations. 2nd ed. Philadelphia:

illa. Report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

W. B. Saunders Co., 1993:362–97.

1977;44:34–8.

4. Small IA, Waldron CA. Ameloblastoma of jaws. J Oral Maxil-

24. Weissman JL, Snyderman CH, Yousem SA, Curtis HD. Amel-

lofac Surg 1955;8:281–97.

oblastoma of the maxilla: CT and MR appearance. AJNR Am

5. Robinson HBG. Ameloblastoma. A survey of 379 cases from

J Neuroradiol 1993;14:223–6.

the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1937;23:831–43.

25. Kieserman SP, Baker P, Eberle R. Ameloblastoma of the max-

6. Sehdev MK, Huvos AG, Strong EW, Gerold FP, Willis GW.

illa: a series of three cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;

Ameloblastoma of the maxilla and mandible. Cancer 1974;

116:395–8.

33:324–33.

26. Vickers RA, Gorlin RJ. Ameloblastoma: delineation of early histo-

7. Tsaknis PJ, Nelson JF. The maxillary ameloblastoma: an

pathologic features of neoplasia. Cancer 1970;26:699–710.

analysis of 24 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1980;38:336–42.

27. Stanley HR Jr., Krogh HW. Peripheral ameloblastoma. Report

8. Weiss JS, Bressler SB, Jacobs EF Jr., Shapiro J, Weber A,

of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1959;12:760–5.

Albert DM. Maxillary ameloblastoma with orbital inva-

28. Klinar KL, McManis JC. Soft-tissue ameloblastoma. Oral

sion. A clinicopathologic study. Ophthalmology 1985;92:

Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1969; 28:266–72.

710–3.

29. Wallen NG. Extraosseous ameloblastoma. Oral Surg Oral

9. Kwartler JA, Labagnara J Jr., Mirani N. Ameloblastoma pre-

Med Oral Pathol 1972; 34:95–7.

senting as a unilateral nasal obstruction. J Oral Maxillofac

30. Langman J. Head and neck. In: Medical embryology. 4th

Surg 1988; 46:334–6.

edition. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1981:268 –96.

10. Scaccia FJ, Strauss M, Arnold J, Maniglia AJ. Maxillary amel-

31. Ten Cate AR. Embryology of the head, face, and oral cavity

oblastoma: case report. Am J Otolaryngol 1991;12:20–5.

and structure of the oral tissues. In: Ten Cate AR, editor.

11. Cheney ML, Wolf C, Cox RH, Kreutziger KL. Ameloblastoma

Oral histology: development, structure, and function. St.

presenting as chronic sinusitis. J La State Med Soc 1986;138:

Louis: C. V. Mosby Company, 1985:13 –77.

11–4.

32. Bakay L. Az a

´

llkapocs ko¨zponti ha

´

mdaganata

´

nak sza

´

rma-

12. Pantazopoulos PE, Nomikos N. Adamantinoma of the maxil-

za

´

sa. Orv Hetil 1908; 52:473–8.

lary sinus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1966;75:1160–8.

33. Gardner DG. Peripheral ameloblastoma. A study of 21 cases,

13. De Gandt J-B, Gerard M. A propos d’un ame

´

loblastome du

including 5 reported as basal cell carcinoma of the gingiva.

sinus maxillaire. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg 1974;28:365– 8.

Cancer 1977; 39:1625–33.

14. Gaillard J, Haguenauer JP, Pignal JL, Dubreuil C. Ame

´

loblas-

34. Woo S-B, Smith-Williams JE, Sciubba JJ, Lipper S. Peripheral

tome du sinus maxillaire. J Fr Otorhinolaryngol 1981;30:107–

ameloblastoma of the buccal mucosa: case report and re-

10.

view of the English literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pa-

15. Marsot-Dupuch K. Sinusite maxillaire re

´

va

´

latrice d’une lo-

thol 1987; 63:78–84.

calisation nasosinusienne d’un ame

´

loblastome. Ann Radiol

35. Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. Tumors of the central nervous

(Paris) 1991; 34:131–2.

system. In: Rosai J, Sobin L, editors. Atlas of tumor pathol-

16. Seabaugh JL, Templer JW, Havey A, Goodman D. Ameloblas-

ogy. Fascicle 10. Third series. Washington, DC: Armed Forces

toma presenting as a nasopharyngeal tumor. Otolaryngol

Institute of Pathology, 1994:349 –54.

Head Neck Surg 1986; 94:265–7.

/ 7bb2$$0788 01-24-98 11:03:42 canal W: Cancer