GHANA

MDG ACCELERATION FRAMEWORK

AND COUNTRY ACTION PLAN

MATERNAL HEALTH

July 2011

18605 Ghana omslag.indd 1 25/05/11 00.30

MDG ACCELERATION FRAMEWORK

AND COUNTRY ACTION PLA

MATERNAL HEALTH

July 2011

Copyright © Ministry of Health (MoH), Government of Ghana and United Nations

Country Team in the Republic of Ghana

All rights reserved.

Acknowledgements:

The Ministry of Health, Ghana Health Service and the UNDP wishes to express

its appreciation to the task team and all who in diverse ways worked tirelessly to

develop the MDG Acceleration Framework Country Action Plan. Members of the

task team involved in the preparation of the action plan include:

George K. Amofah, Deputy Director General, Ghana Health Service; Patrick Kuma-

Aboagye, Deputy Director, RCH, Ghana Health Service; Kyei-Faried, Deputy Director,

DCD, Ghana Health Service; Pa Lamin Beyai, Economic Advisor, UNDP; Akua Dua-

Agyeman, MDG Support Advisor, UNDP; Siaka Coulibaly, MDG Advisor, RSC UNDP,

Dakar; Daniela Gregr, Policy Specialist, UNDP; Ayodele Odusola, MDG Advisor,

UNDP; Shantanu Mukherjee, Policy Advisor, UNDP; Robert Mensah, NPO-RH, UNFPA;

Rhoda Manu, PMTCT-MH Specialist, UNICEF; Charles Fleischer-Djoleto, NPO-FHP,

WHO; Joseph Adomako, DDHS-Amansie West District, Ghana Health Service. We

are grateful to the consultants Alhaj Mohammed Bin Ibrahim and Moses Aikins for

their hard work in guiding the development of this document.

Design:

Phoenix Design Aid A

a carbon neutral company.

Cover photo credits:

UNDP Kayla Keenan

18605 Ghana omslag.indd 2 25/05/11 00.30

JULY 2011

GHANA

MDG ACCELERATION FRAMEWORK

A

ND

C

O

UNTRY ACTION PLAN

MATERNAL HEALTH

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................... 2

ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................ 8

FOREWORD ..................................................................... 10

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION.................................................... 12

CHAPTER 2 PROGRESS AND CHALLENGES IN ACHIEVING MDG 5................. 22

GHAPTER 3 STRATEGIC INTERVENTIONS ………………………………………....... 40

CHAPTER 4 BOTTLENECK ANALYSIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

CHAPTER 5 ACCELERATING MDG PROGRESS: IDENTIFYING SOLUTIONS.......... 52

CHAPTER 6 MDG ACCELERATION PLAN: BUILDING A COMPACT.................. 62

6.1 COUNTRY ACTION PLAN ............................................... 63

6.2 IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING PLAN............................ 72

ANNEXES ....................................................................... 80

ANNEX 1 POLICY DOCUMENTS AND REPORTS....................................... 81

ANNEX 2 QUESTIONNAIRE ADMINISTERED TO DDHS GROUP ........................ 82

ANNEX 3 MDG 5 DOCUMENTS, RECOMMENDATIONS AND LEVEL OF

IMPLEMENTATION.......................................................... 84

ANNEX 4 REFERENCES ............................................................... 87

CONTENTS

5

6

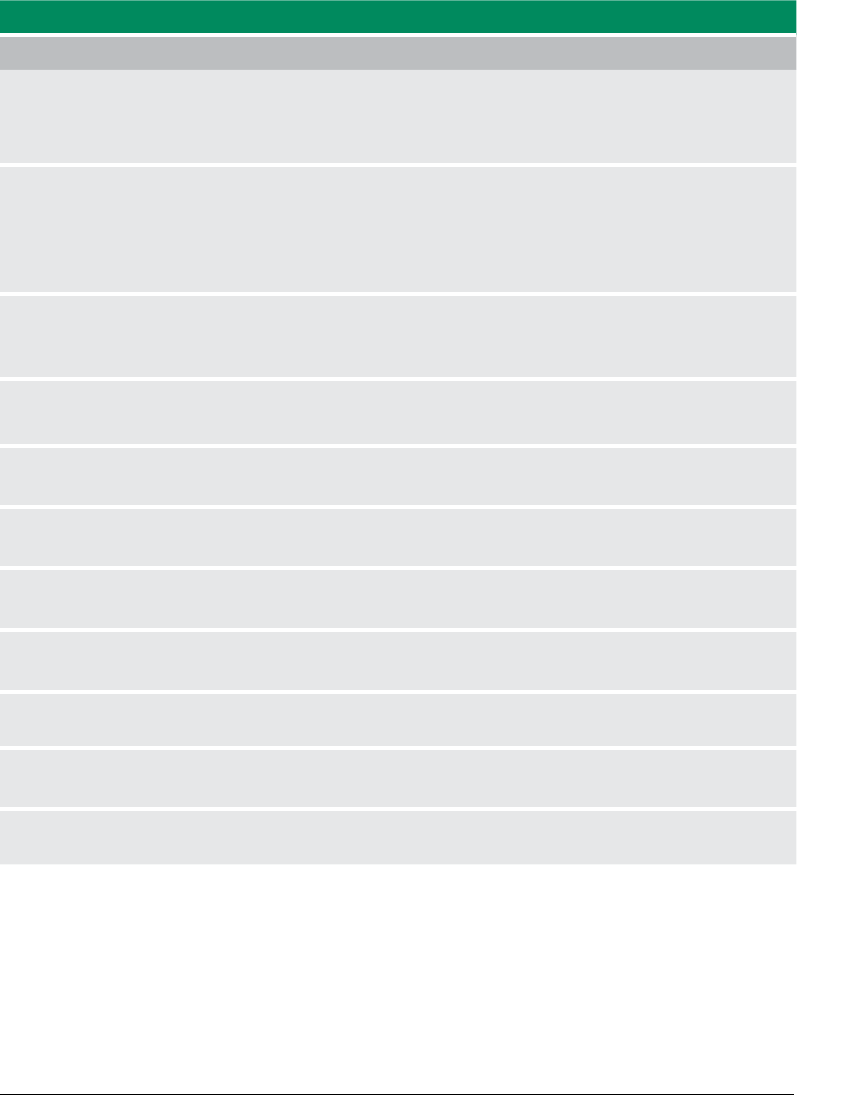

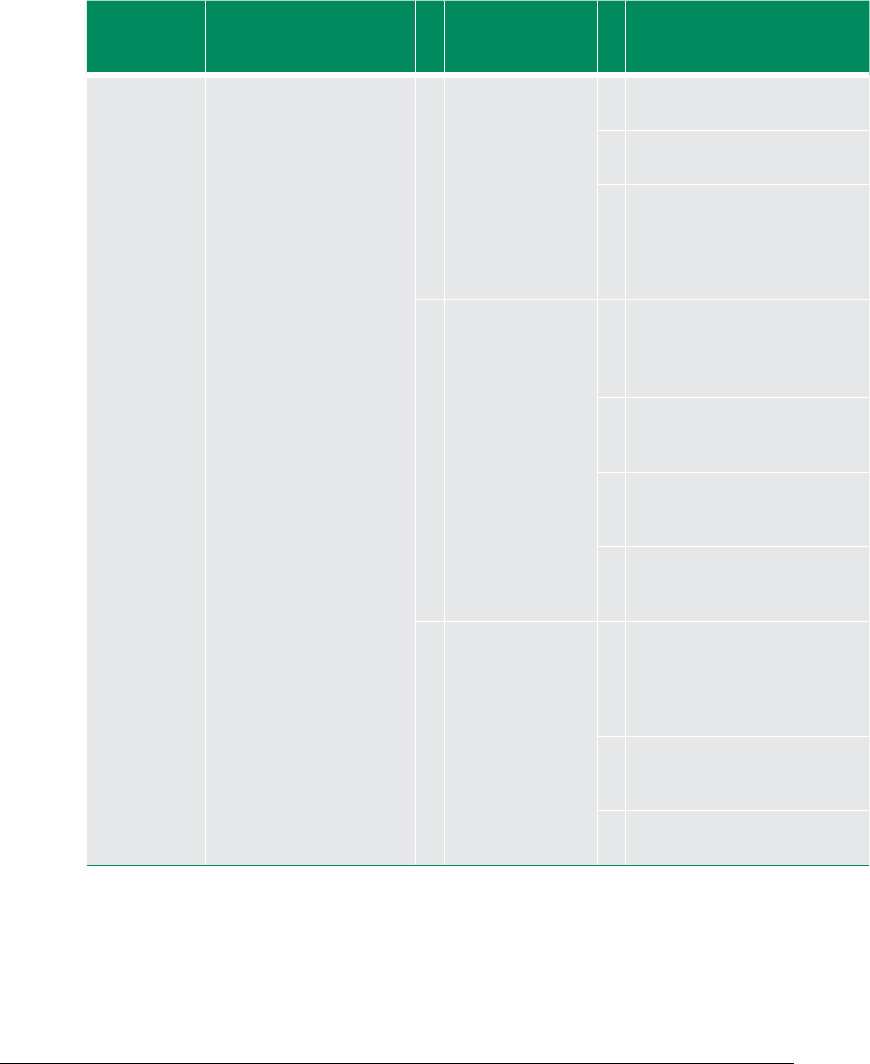

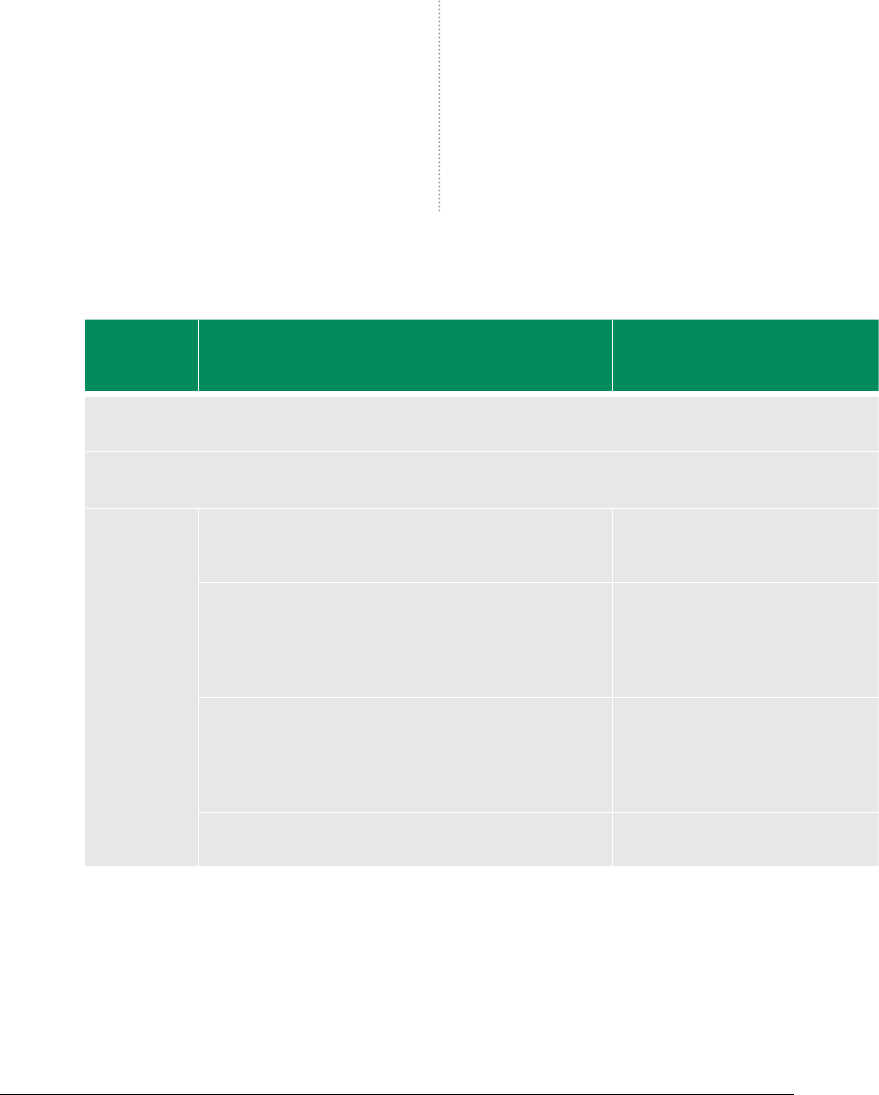

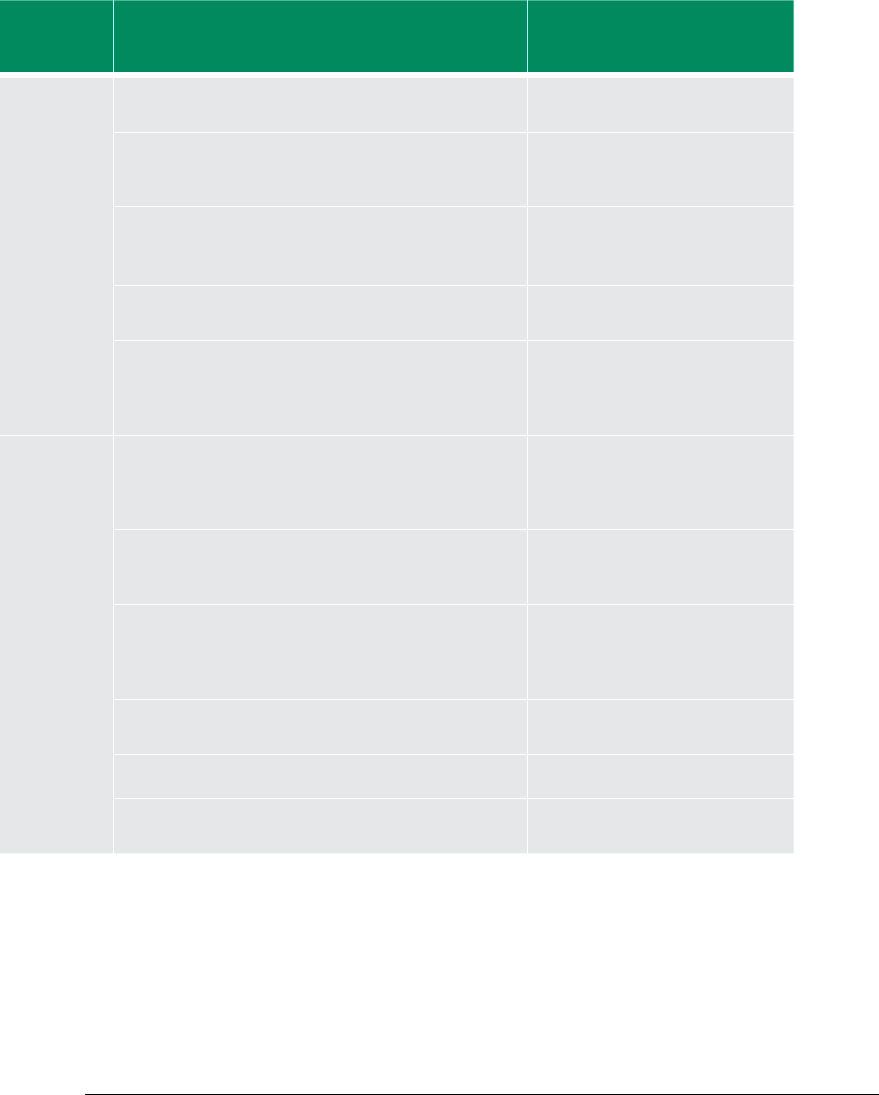

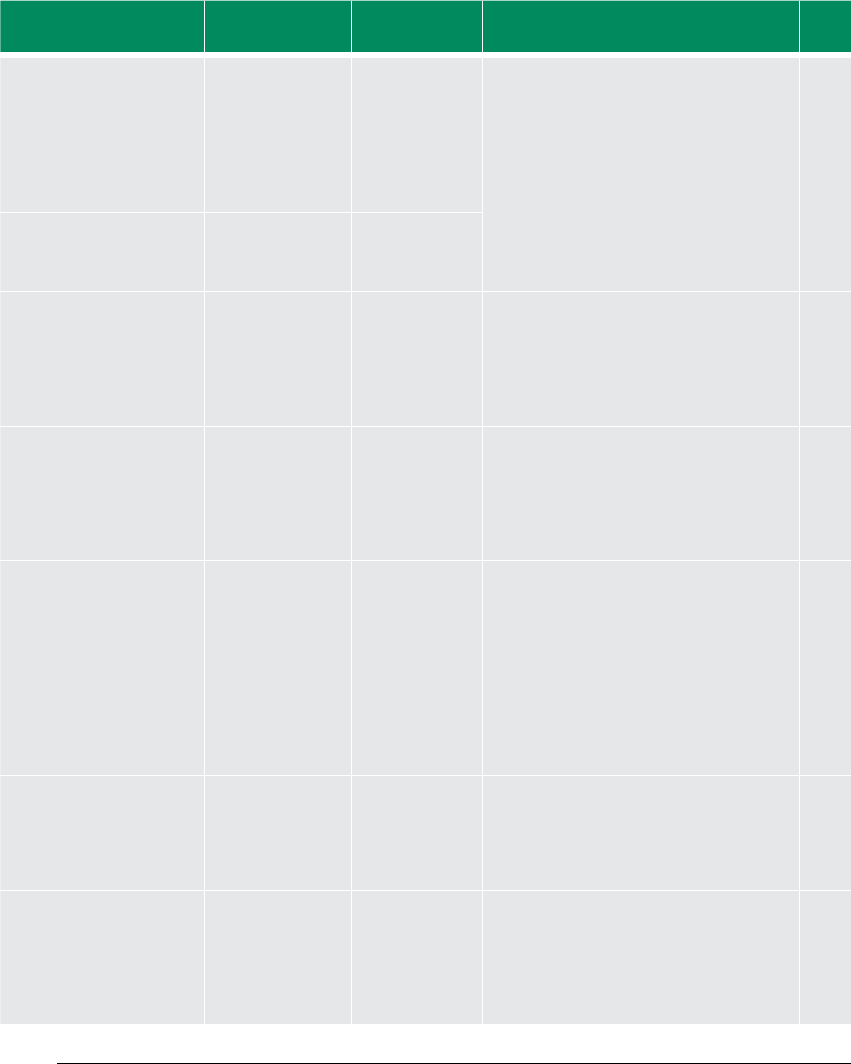

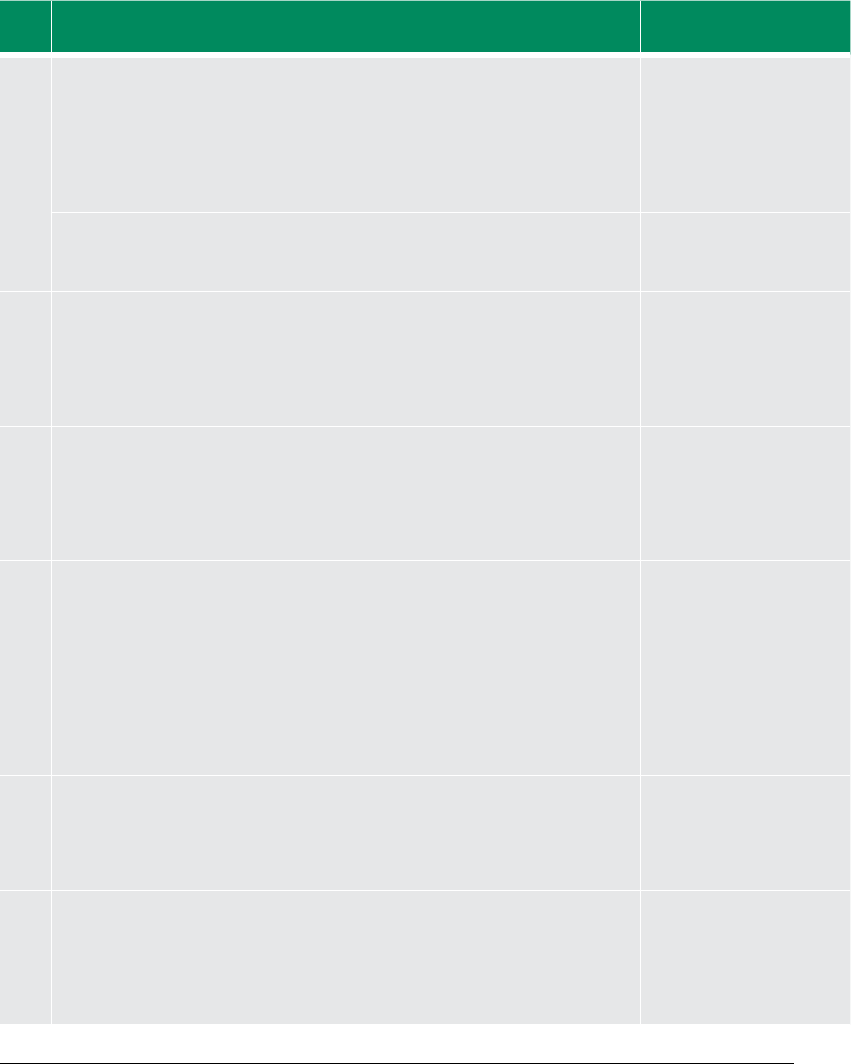

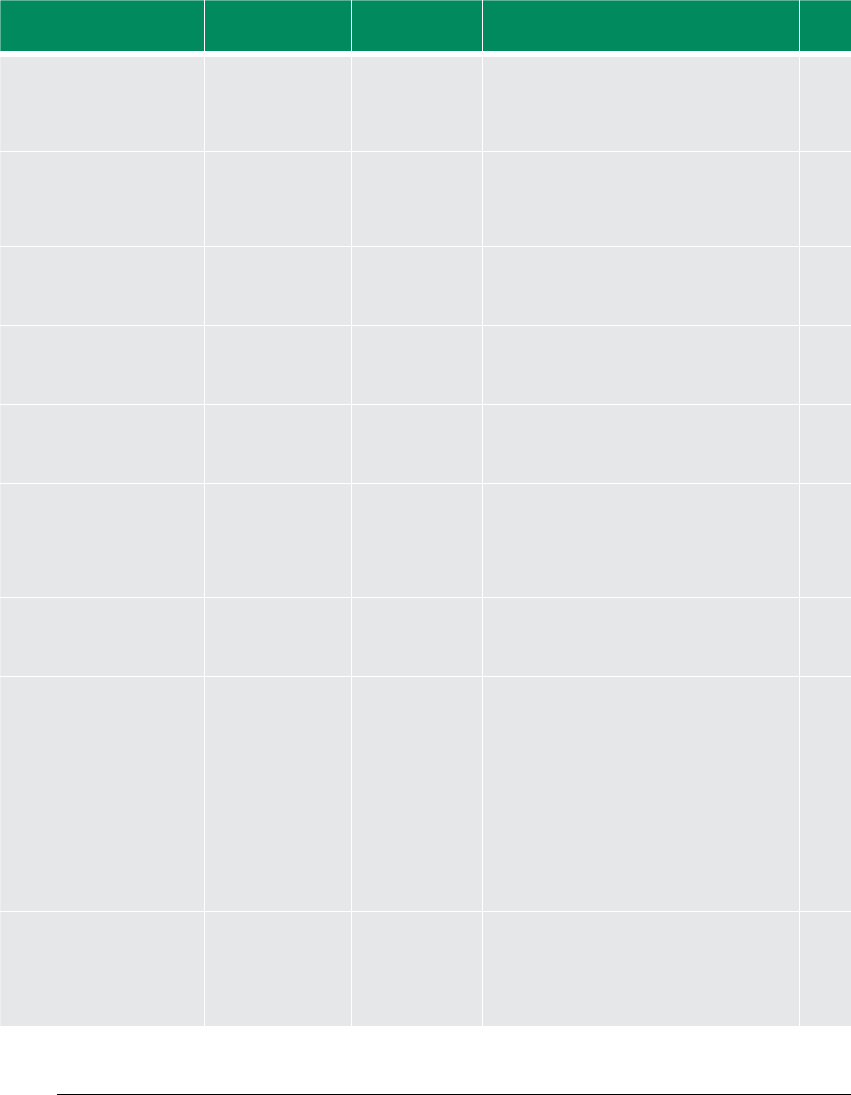

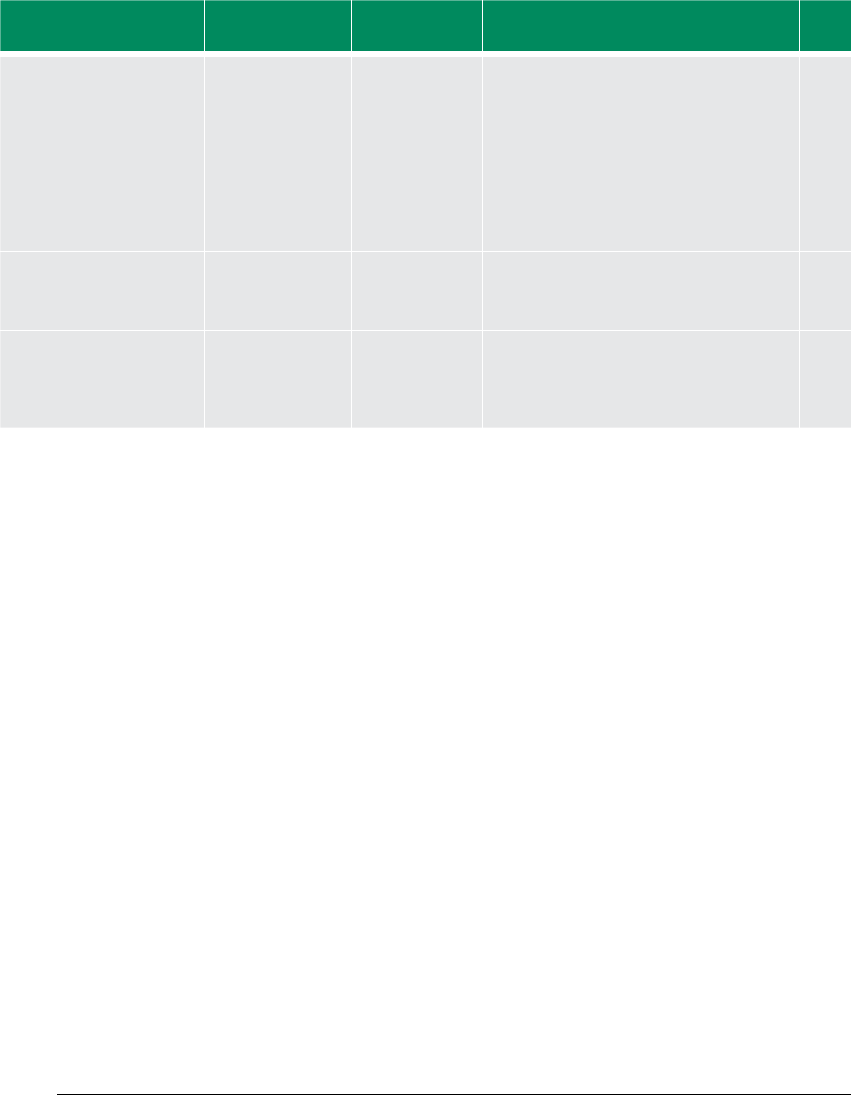

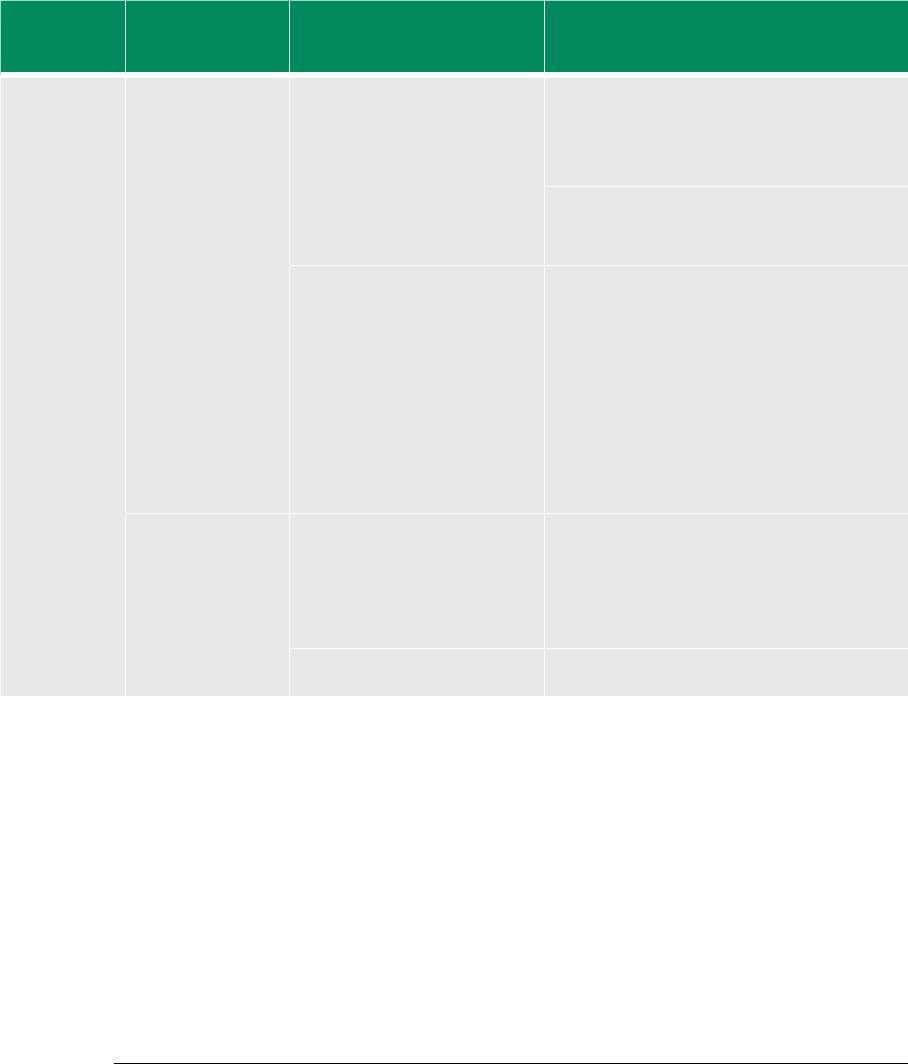

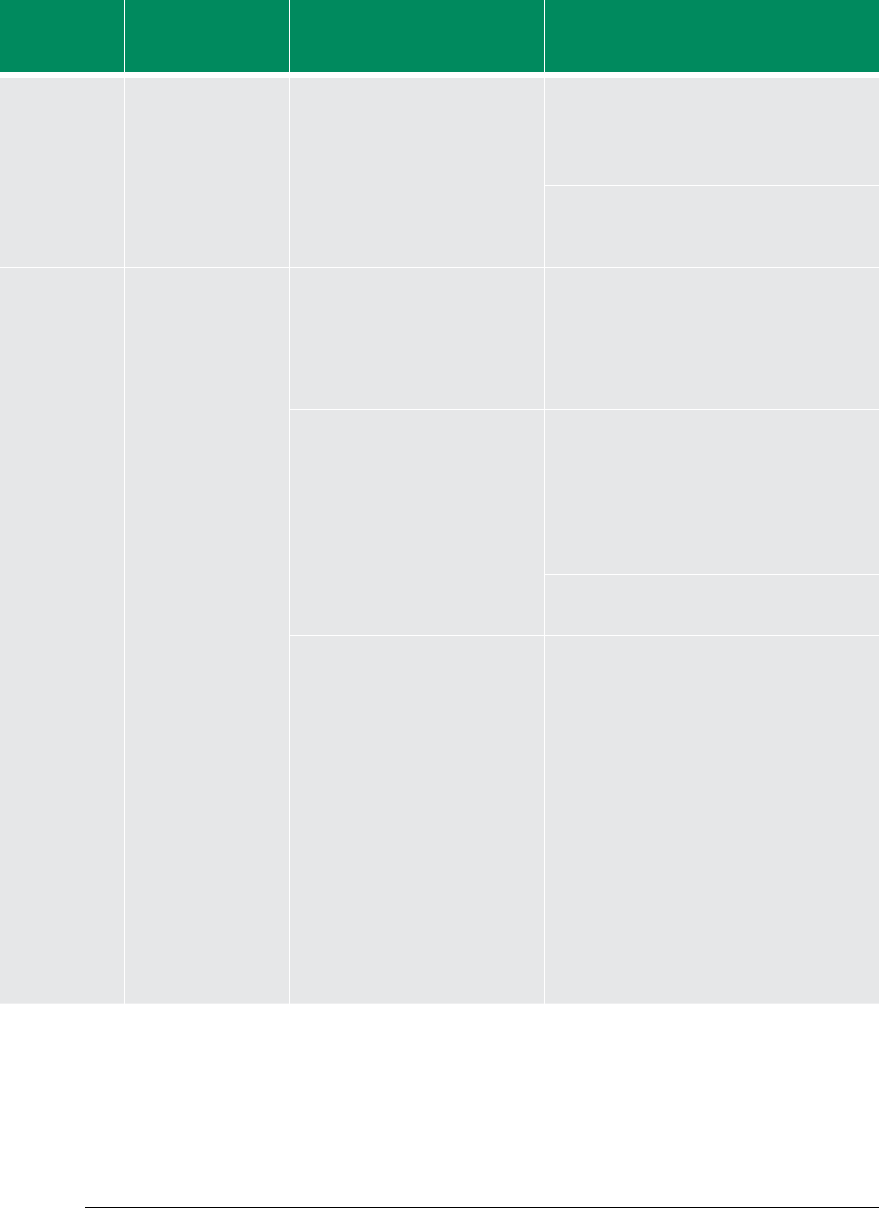

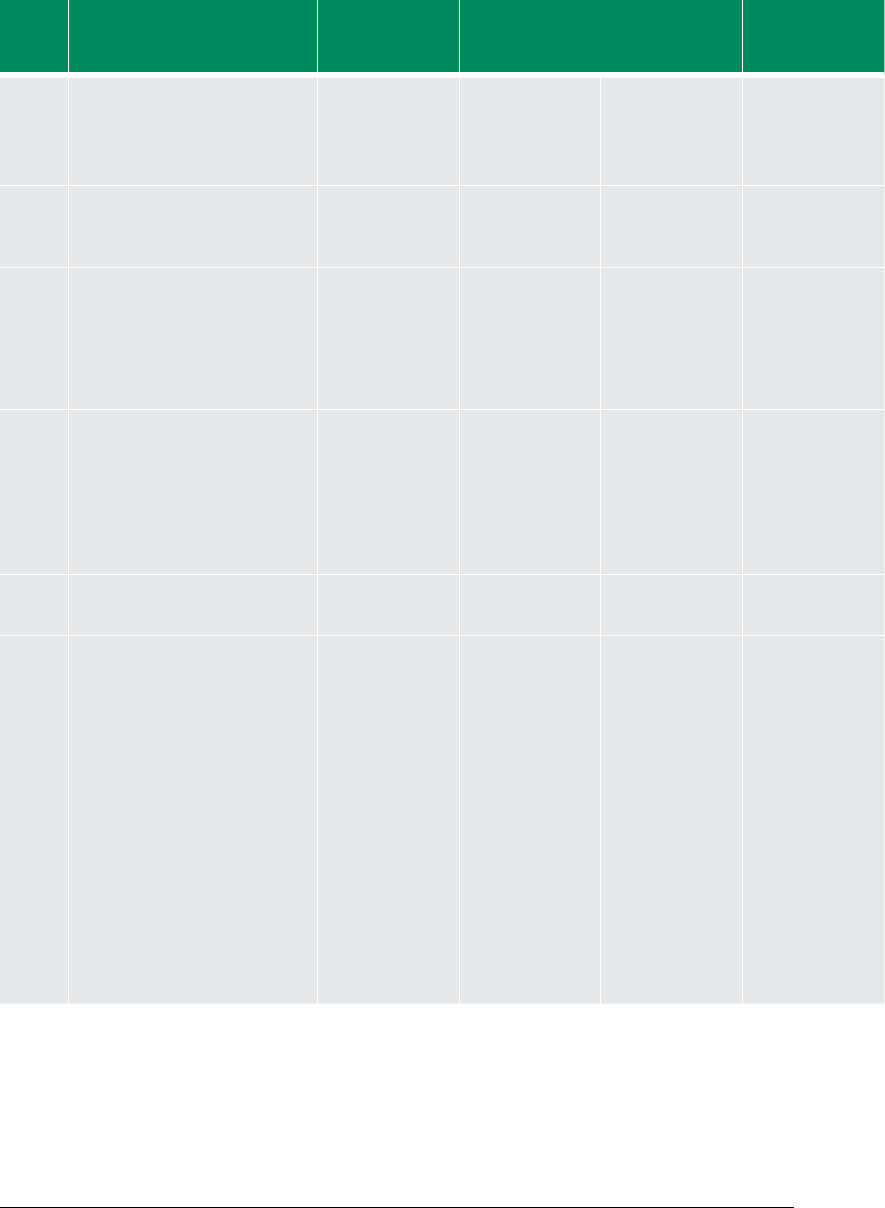

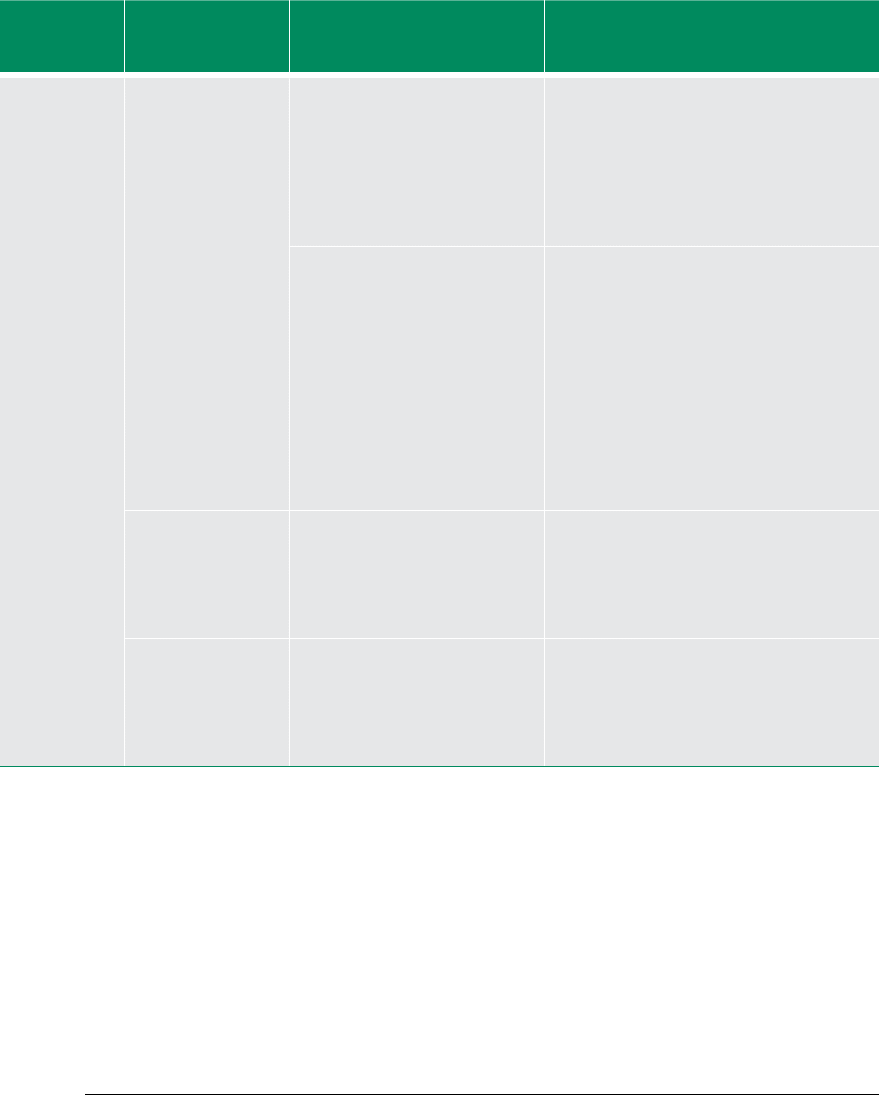

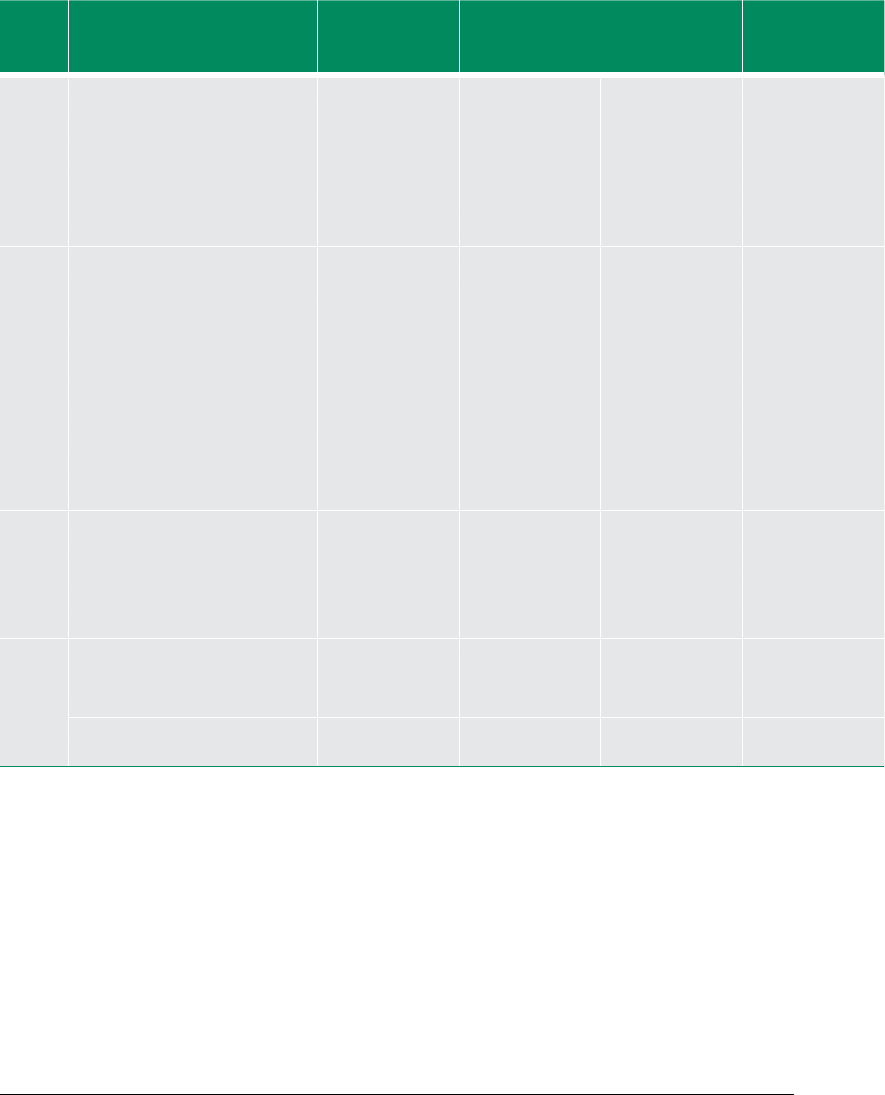

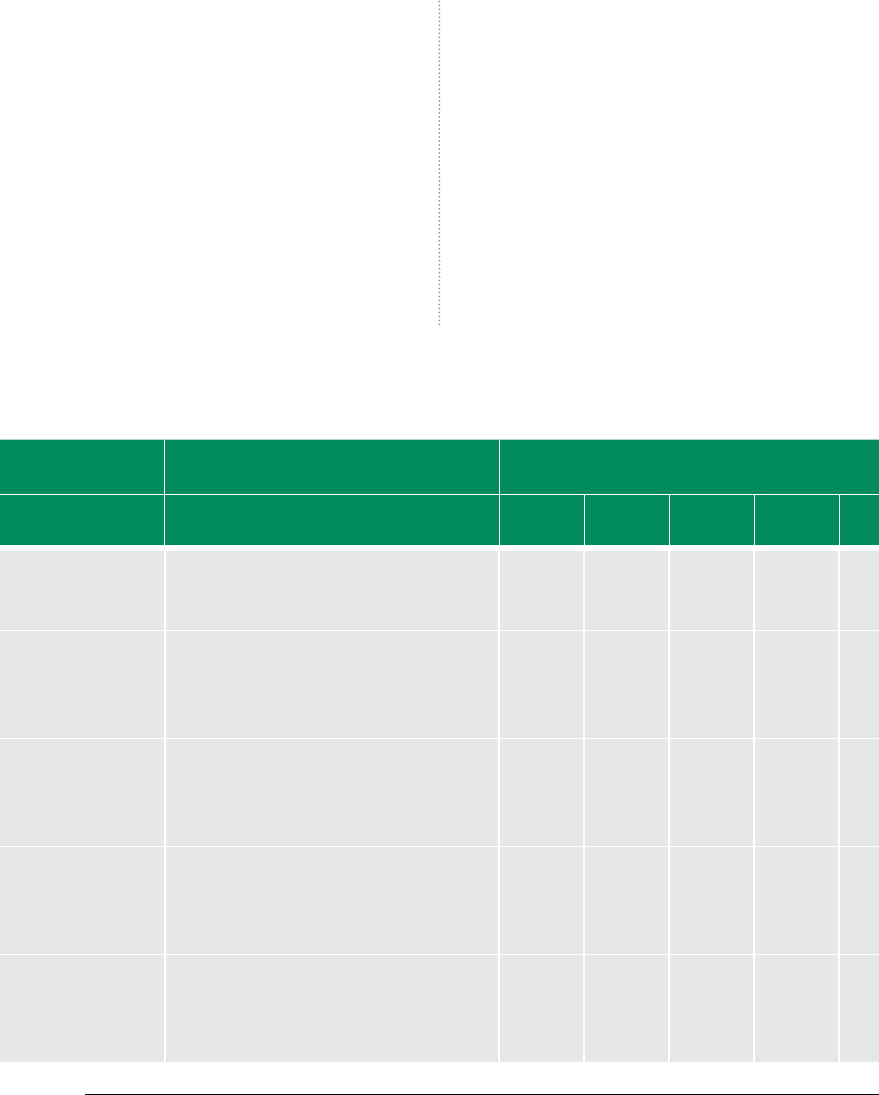

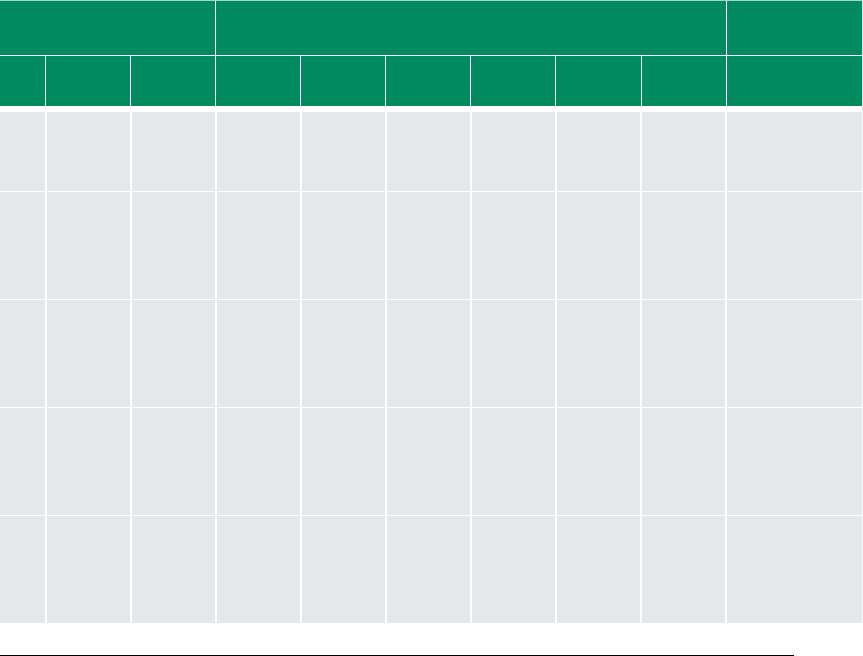

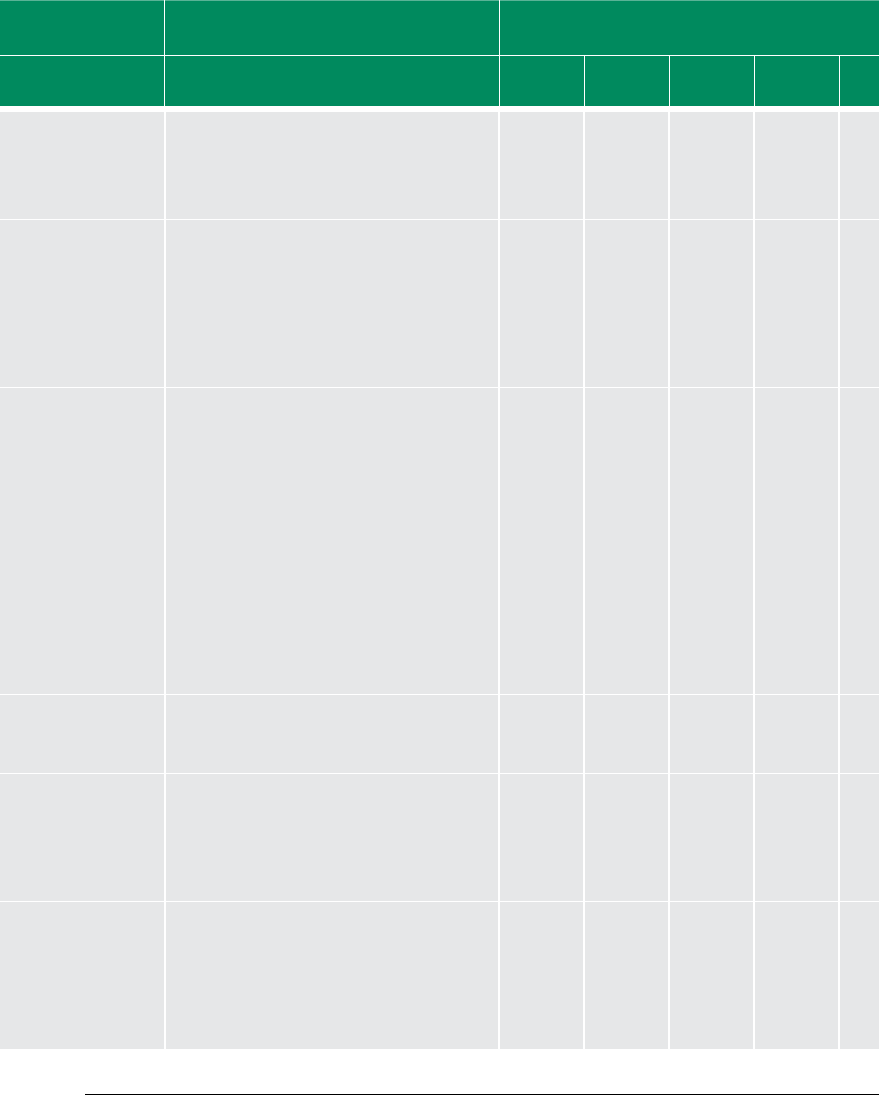

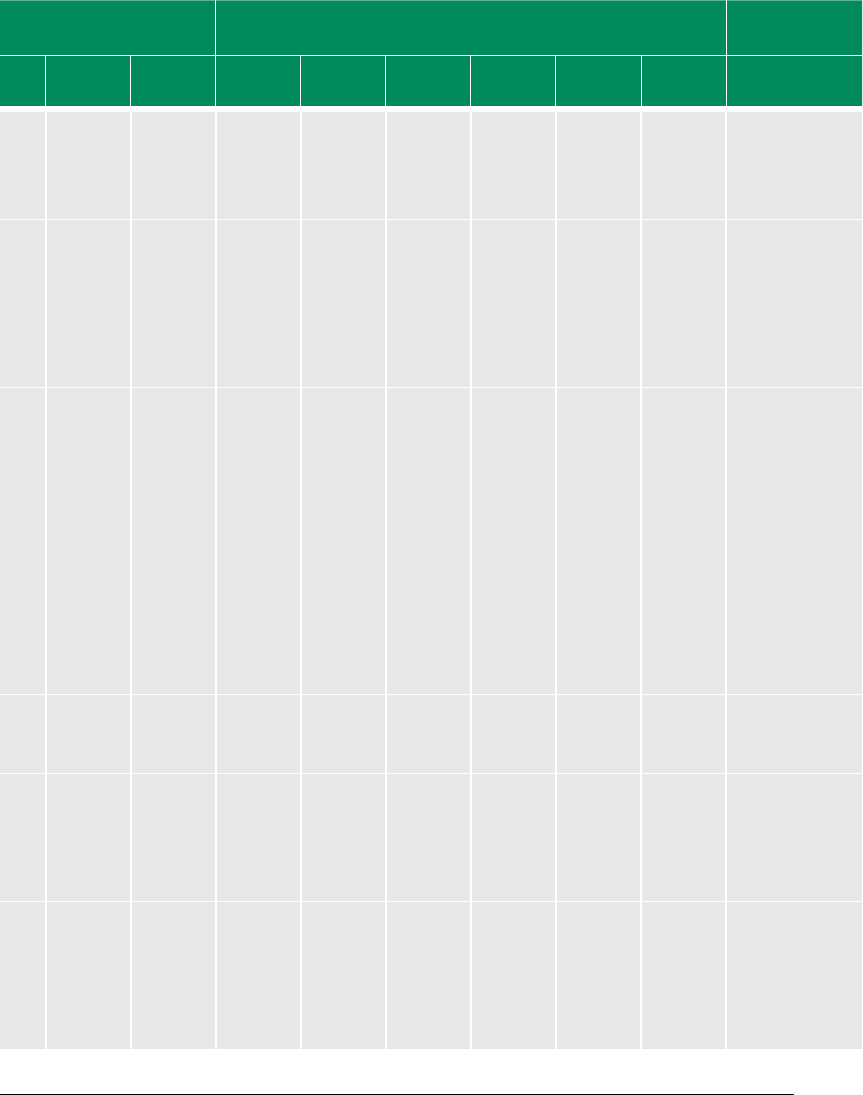

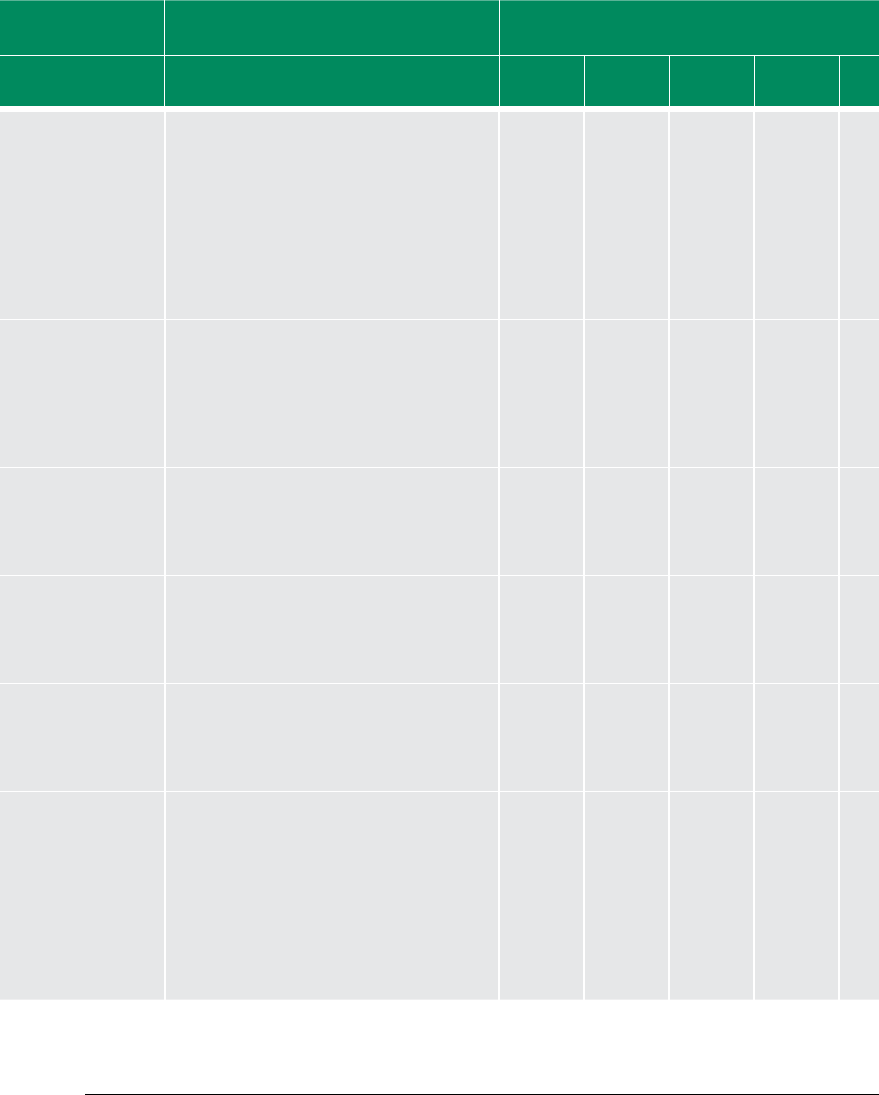

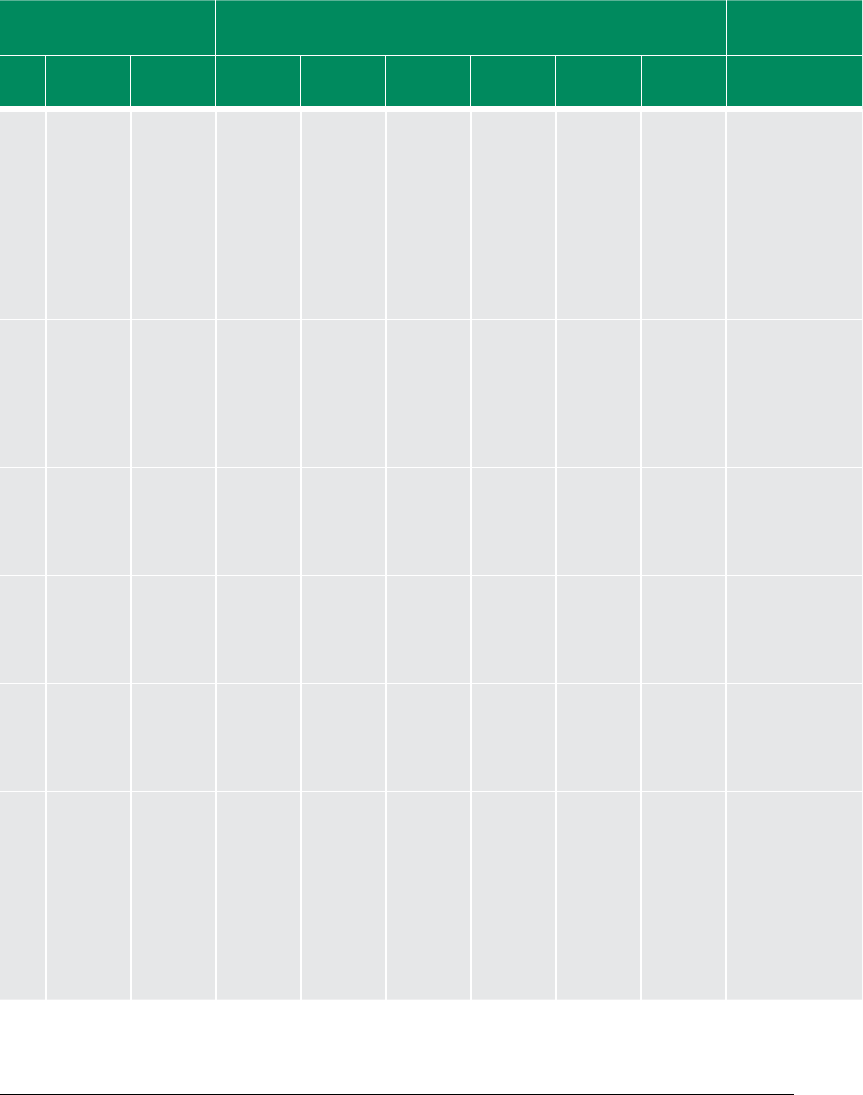

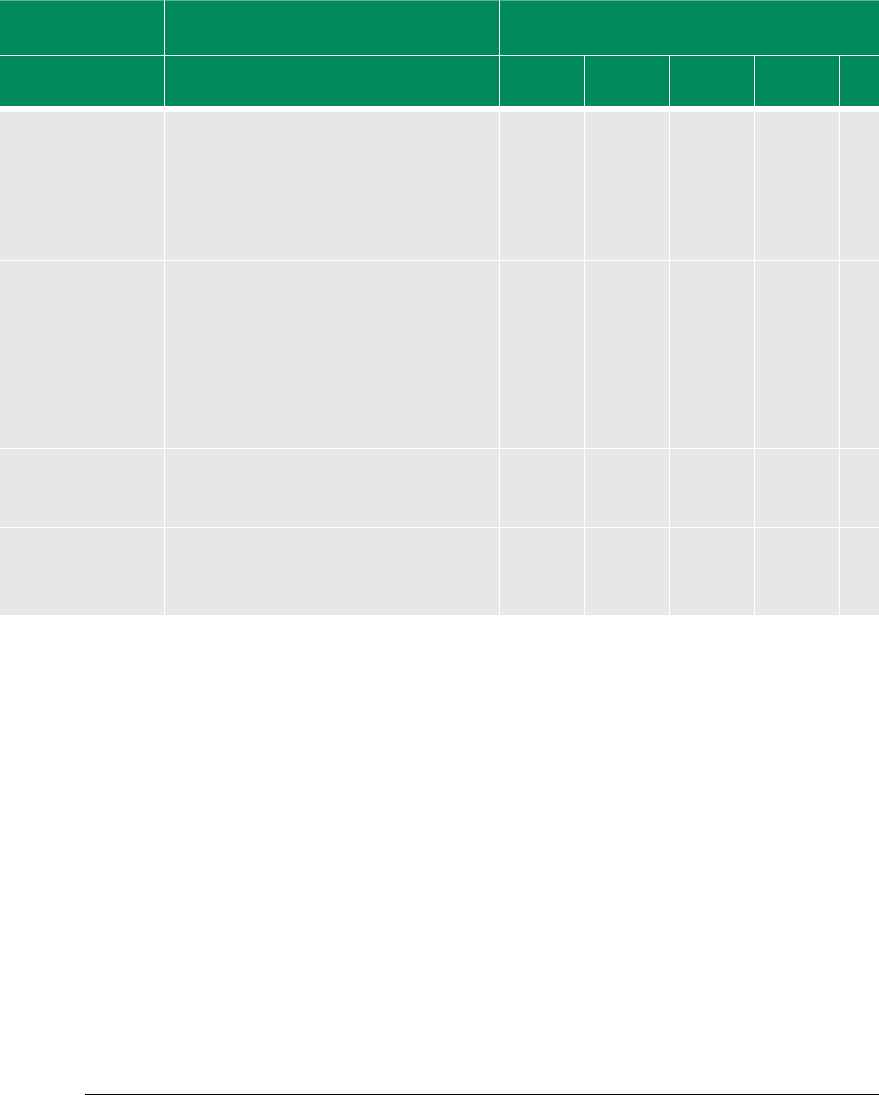

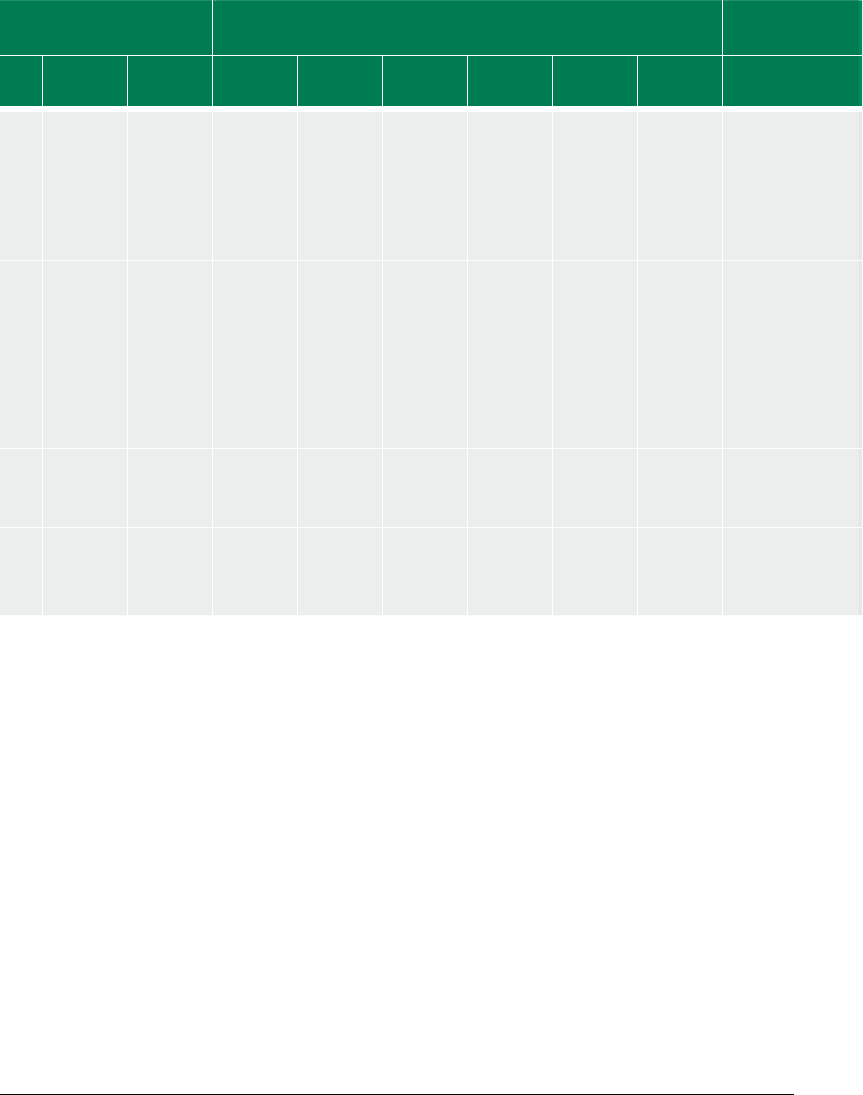

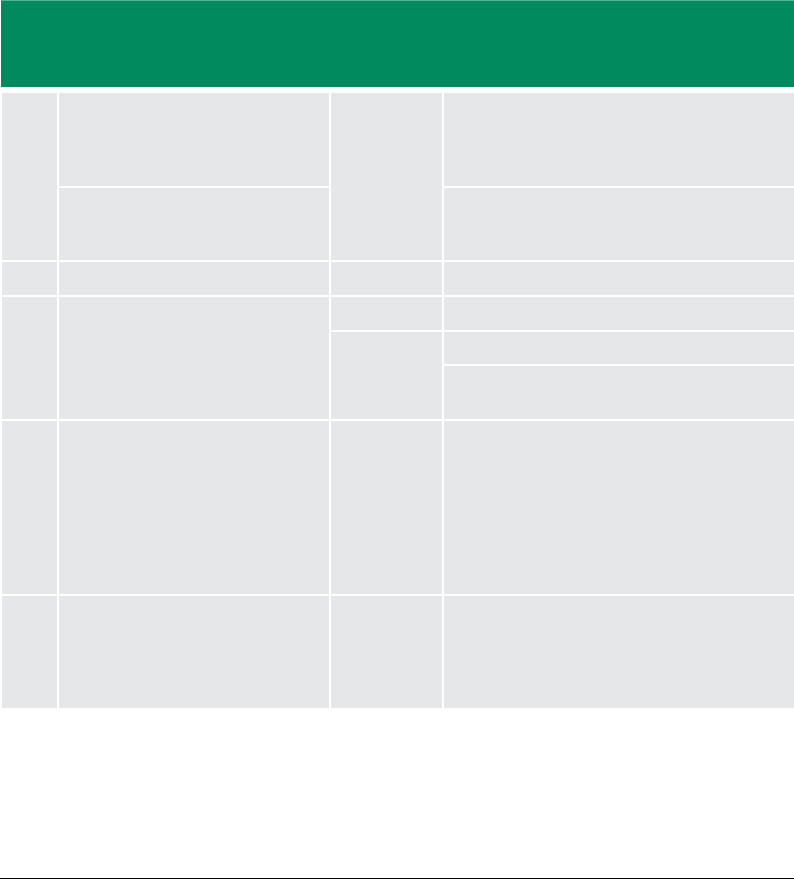

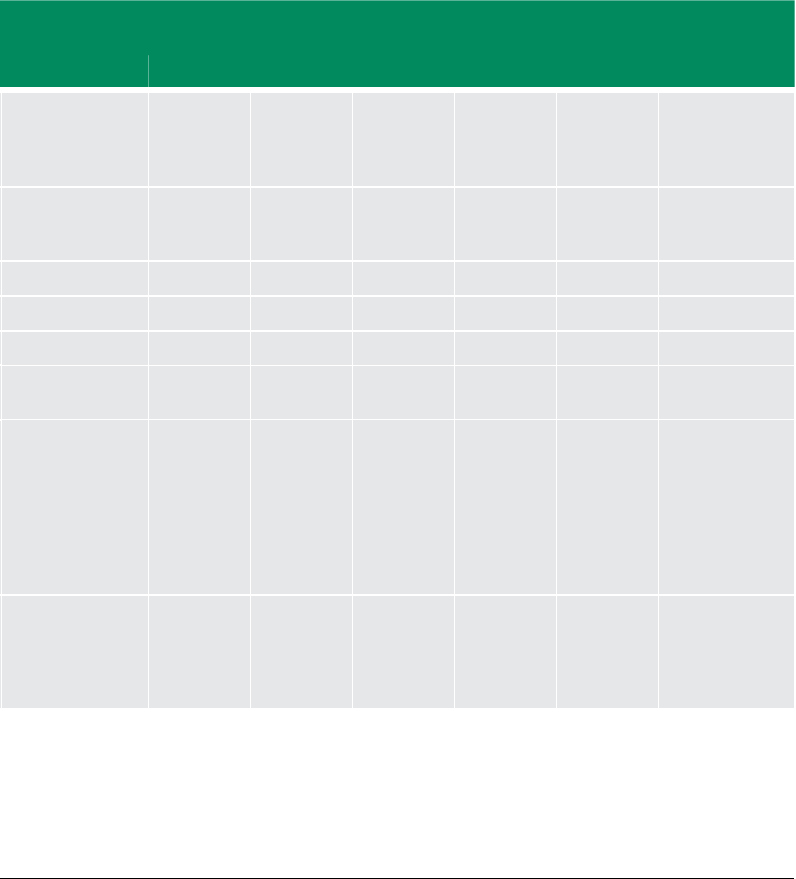

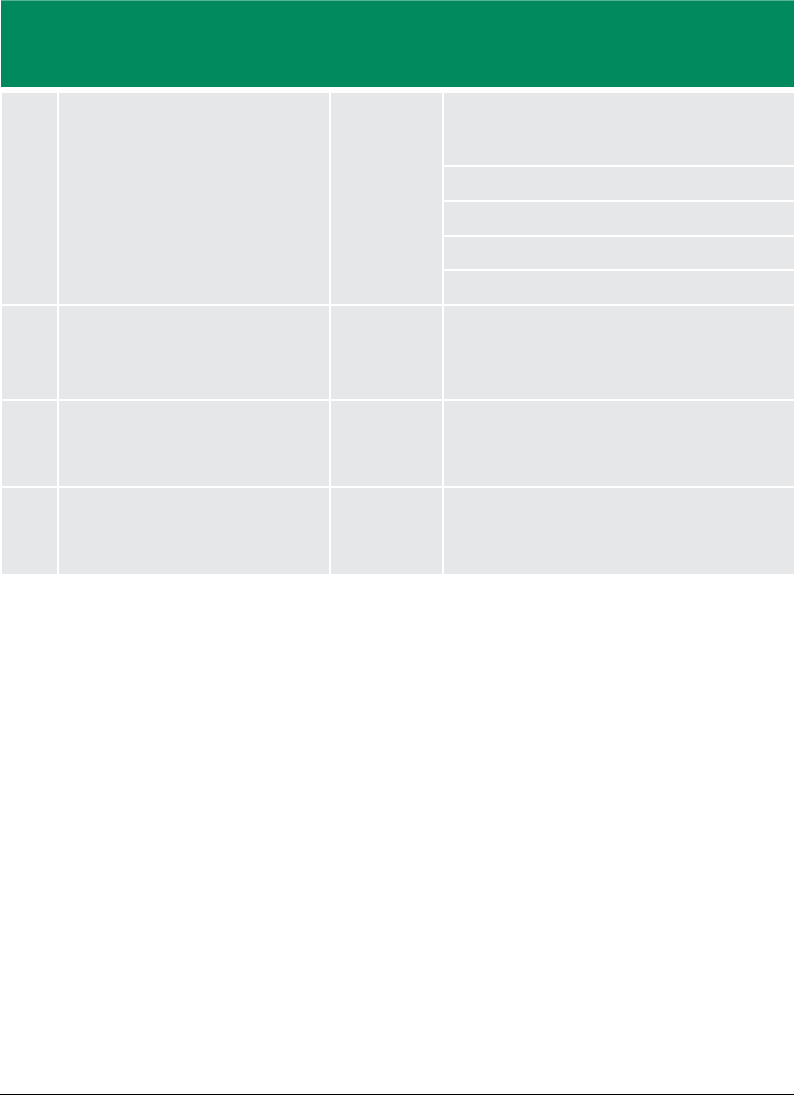

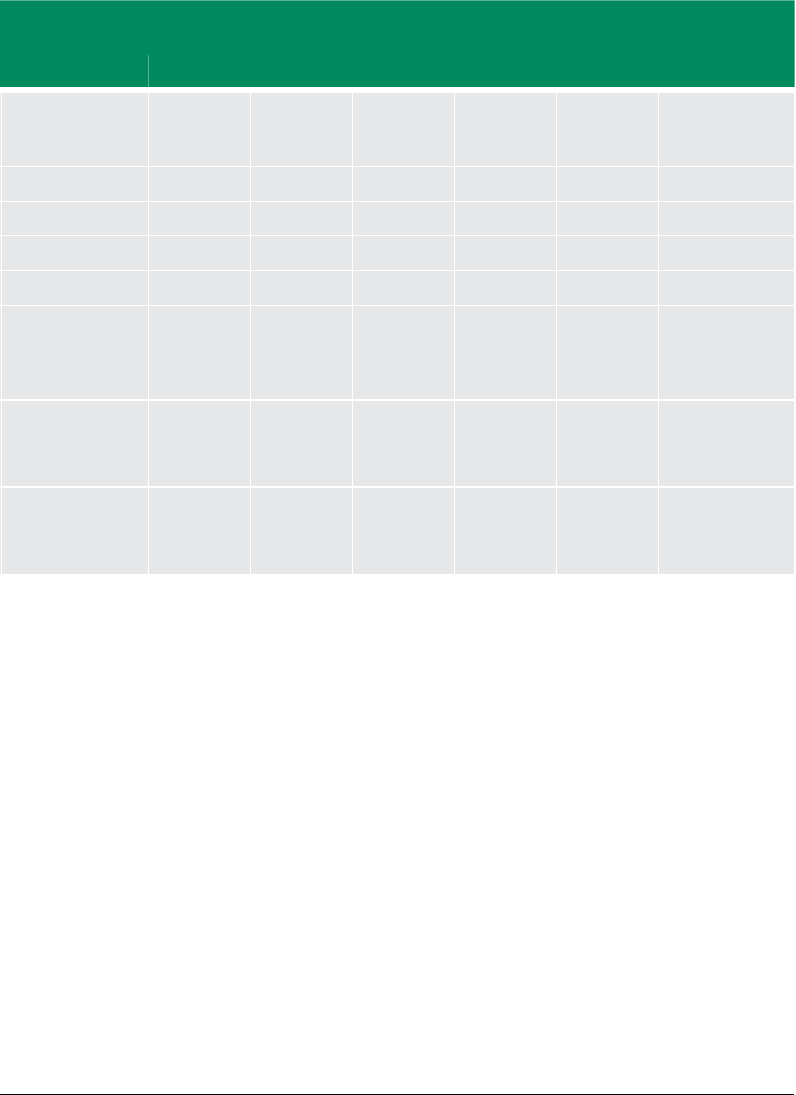

TABLE 1. HEALTH BUDGET 20062009.....................................................26

TABLE 2. TOTAL CONTRACEPTIVES FUNDING REQUIREMENTS BY PROGRAM, 20102012..30

TABLE 3. STATUS OF MDGS AND TRENDS TOWARDS ACHIEVING THEM ...................32

TABLE 4. HUMAN RESOURCE REQUIREMENTS 2010 AND STATUS AS OF 2007, GHANA ..43

TABLE 5. SUMMARY MATRIX OF KEY PRIORITY INTERVENTIONS AND INDICATIVE

INTERVENTIONS, GHANA ........................................................45

TABLE 6. SUMMARY TABLE OF BOTTLENECKS TO KEY PRIORITY INTERVENTIONS TO

ACHIEVE MDG 5 TARGETS, GHANA ...............................................49

TABLE 7. PRIORITIZED SOLUTIONS FOR ACCELERATING PROGRESS TOWARDS

MDG 5, GHANA ..................................................................56

TABLE 8. GHANA MDG 5 ACCELERATION ACTION PLAN ...................................64

TABLE 9. GHANA MDG 5 IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING PLAN.....................72

TABLES

7

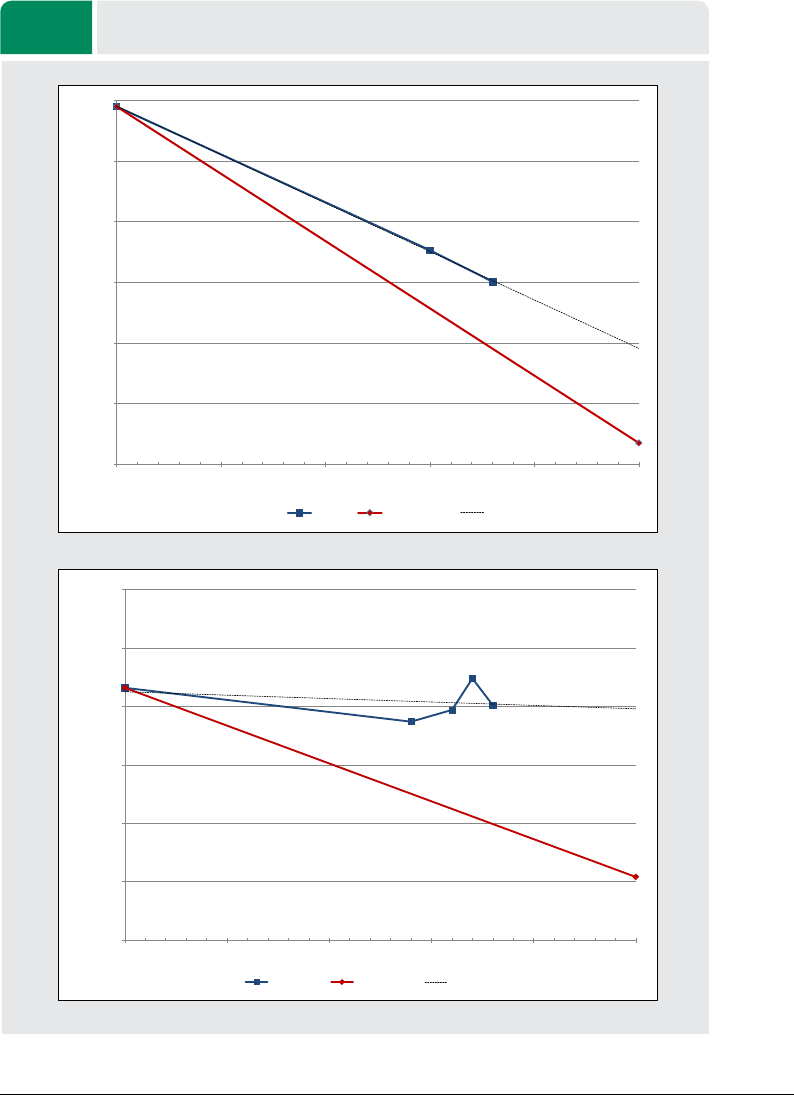

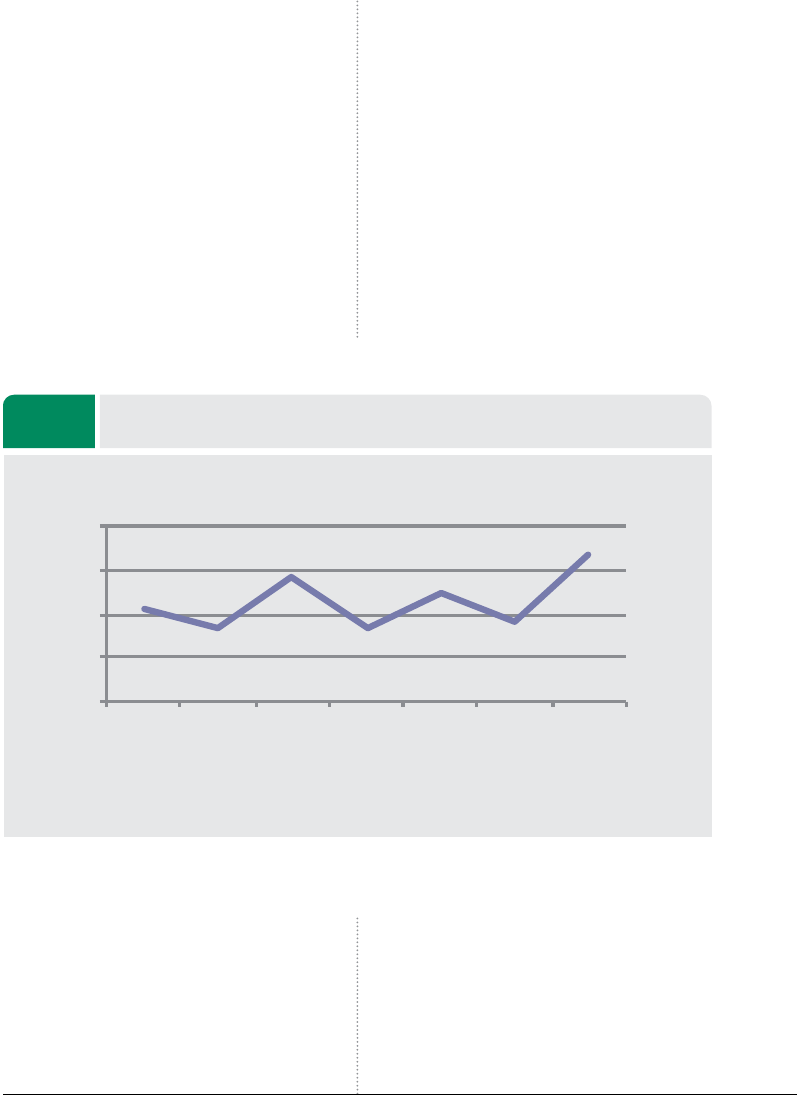

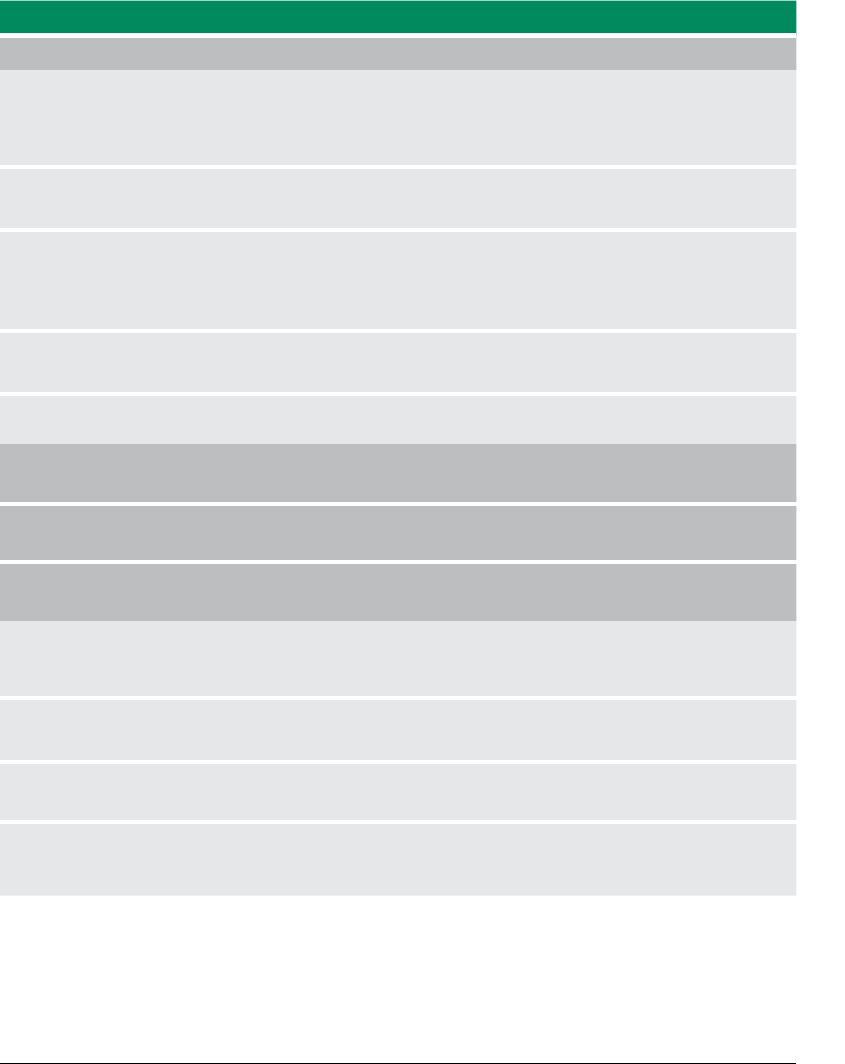

FIGURE 1. TRENDS IN MATERNAL MORTALITY .............................................24

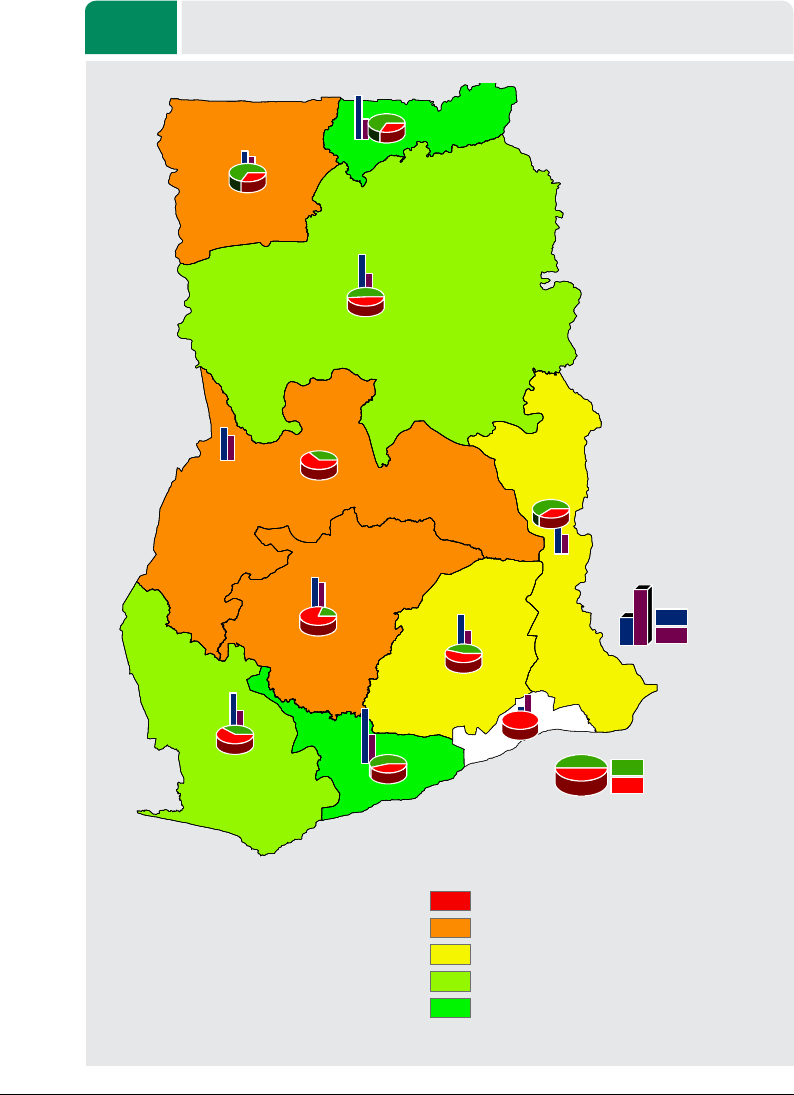

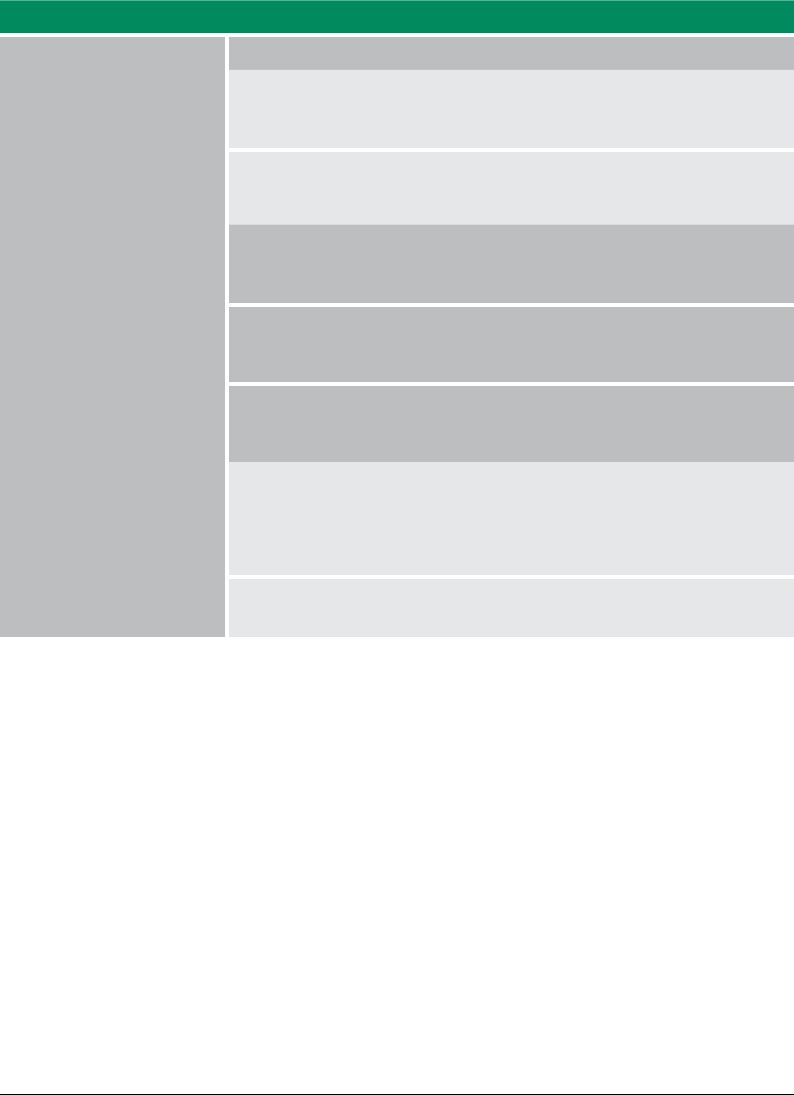

FIGURE 2. MAP OF INSTITUTIONAL MATERNAL MORTALITY RATIO IN GHANA BY REGION . 25

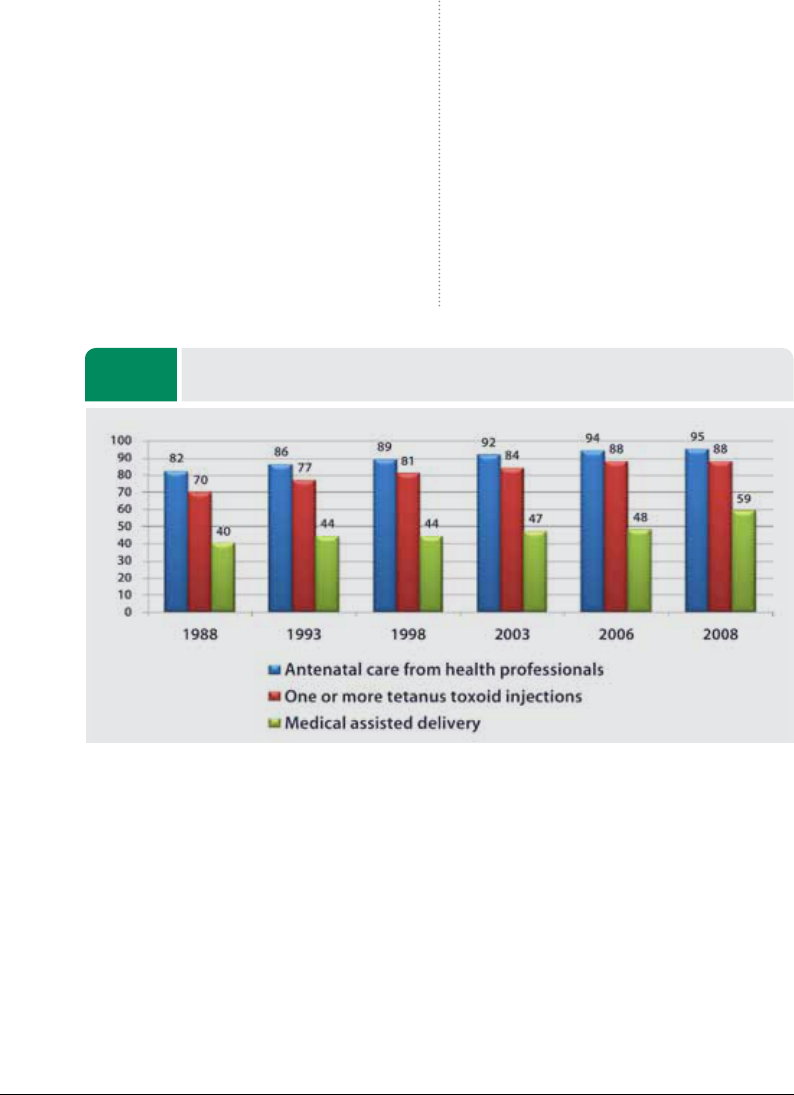

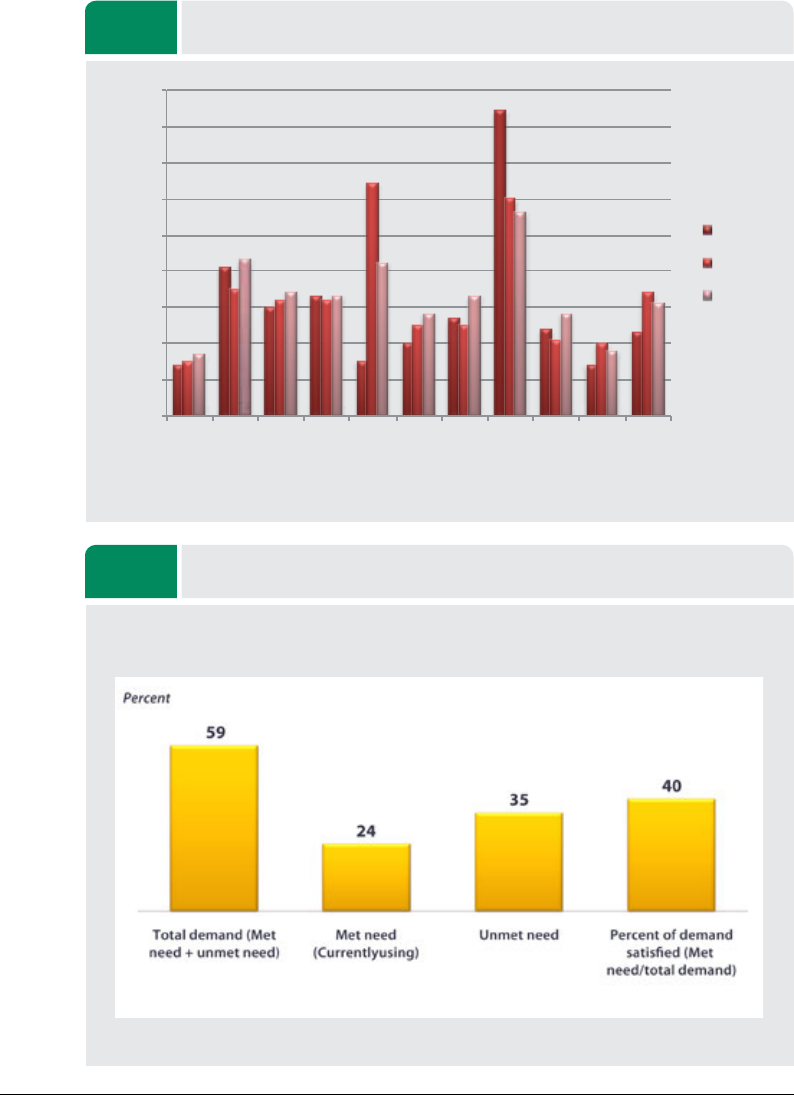

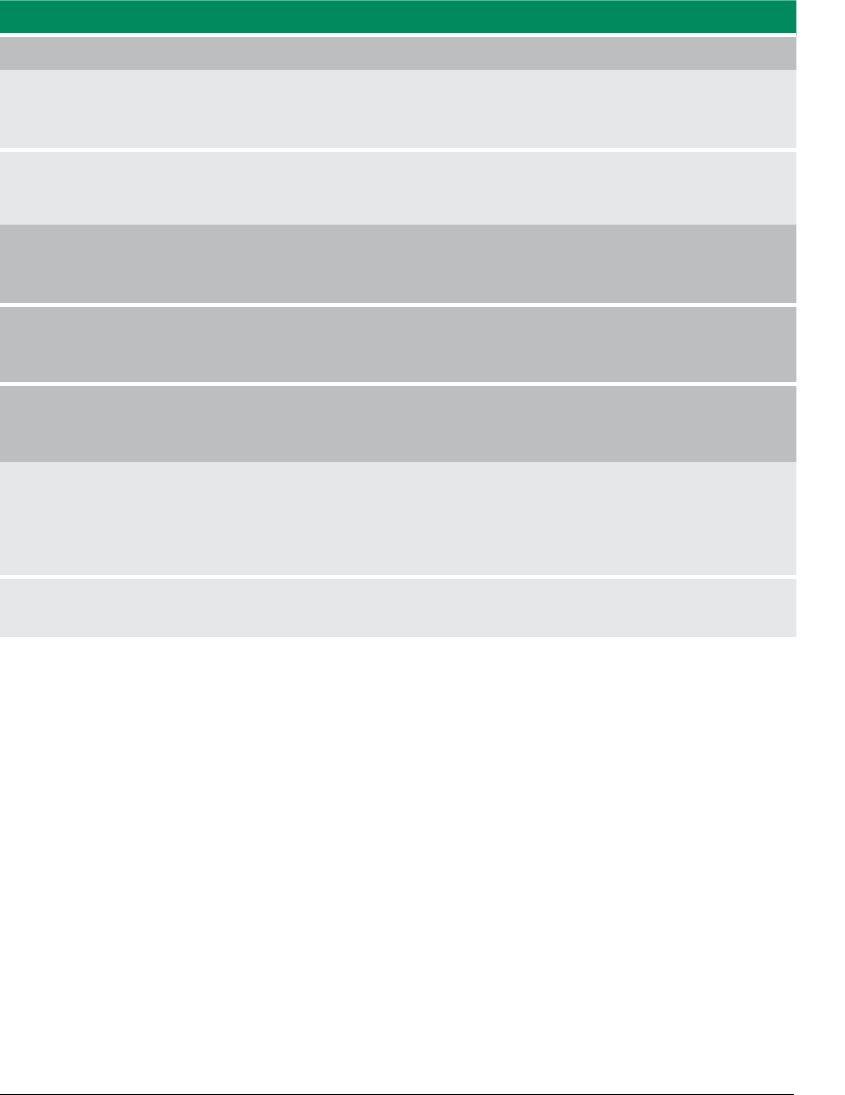

FIGURE 3. SELECTED INDICATORS OF REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH CARE, 19882008 .........27

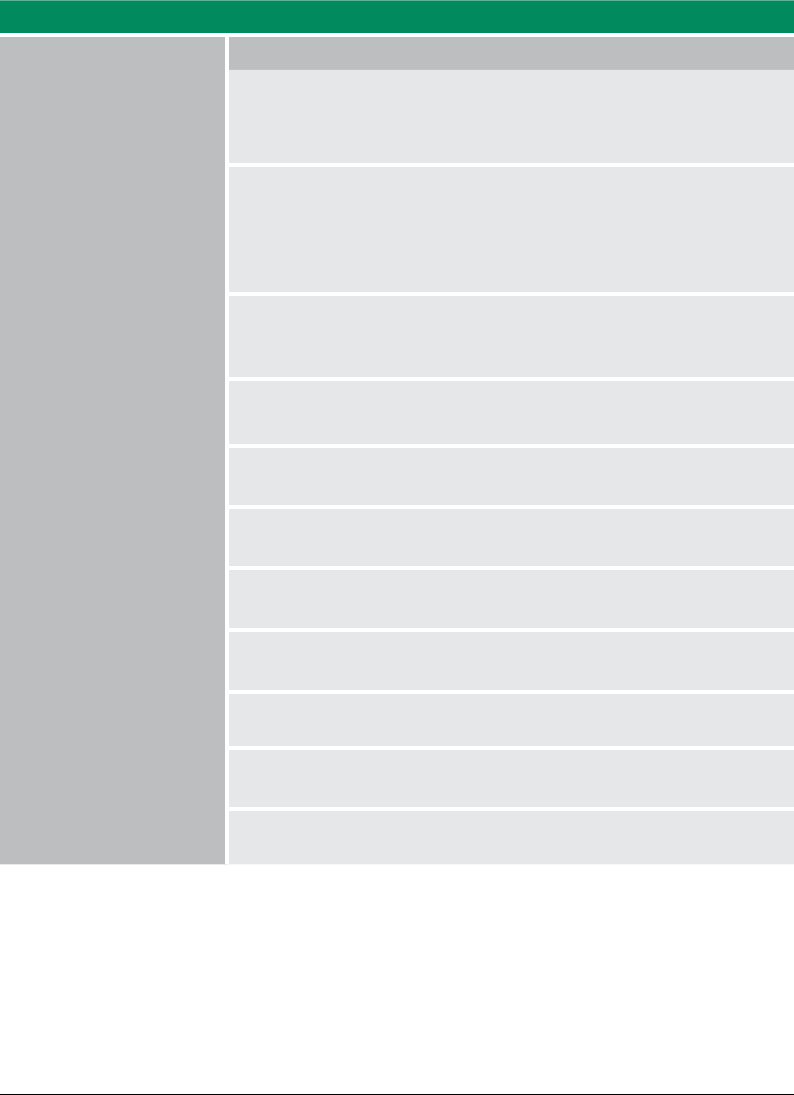

FIGURE 4. POSTNATAL CARE COVERAGE...................................................28

FIGURE 5. FAMILY PLANNING ACCEPTOR RATE BY REGION, 20072009 ....................29

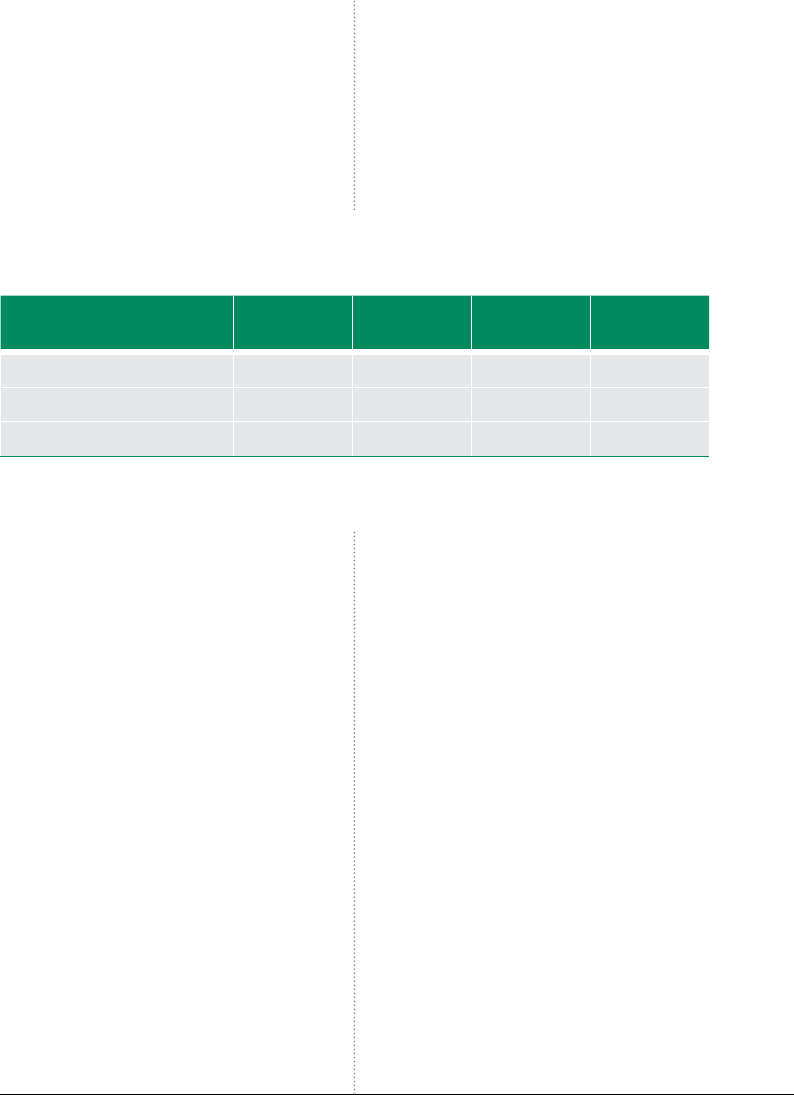

FIGURE 6. DEMAND FOR FAMILY PLANNING AMONG CURRENTLY MARRIED WOMEN .....29

FIGURE 7. VARIATIONS IN CHPS DEPLOYMENT TARGETING ................................31

FIGURES

8

ABBREVIATIONS

ANC Antenatal Care

BCC Behavioural Change Communication

BEOC Basic Emergency Obstetric Care

BTS Blood Transfusion Service

CENC Comprehensive Essential Neonatal Care

CEOC Comprehensive emergency obstetric care

CHPS Community Health Planning and Service

CSO Civil Society Organization

DAs District Assemblies

DHIMS District Health Information Management System

DHMT District Health Management Team

ENC Essential Neonatal Care

EmONC Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care

FP Family Planning

GAVI Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GHS Ghana Health Service

GNP Gross National Product

GPRS I Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy I

GPRS II Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy II

GNP Gross National Product

HIRD High Impact Rapid Delivery

HIV/AIDS Human Immunodeficiency Virus/ Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

ICC Inter-Agency Coordinating Committee

IEC Information, Education and Communication

IUD Intrauterine Device

9

LSS Life Saving Skills

MAF MDG Accelerated Framework

MDG Millennium Development Goals

MDRI Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative

MMDAs Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies

MoFEP Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning

MoH Ministry of Health

MoWH Ministry of Works and Housing

MNH Maternal and Neonatal Health

MMR Maternal Mortality Rate

NDPC National Development Planning Commission

NGO Non-Governmental Organization

NHIS National Health Insurance Scheme

PDA Personal Data Assistant

PMTCT/CT Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission/Counselling and Testing

PNC Postnatal Care

SD Skilled Delivery

STI Sexually Transmitted Infection

TOR Terms of Reference

UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

UNCT United Nations Country Team

UNFPA United Nations Population Fund

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

USAID United States Agency for International Development

WHO World Health Organization

WB World Bank

“The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are

achievable by 2015, if supported by the right set of

policies, targeted technical assistance, institutional

capacity, adequate funding and strong political

commitment. The Government of Ghana, in

collaboration with its development partners, is fully

committed to achieving the MDGs by 2015.

Recent experiences in Ghana demonstrate that

success is possible and that evidence-based effective

interventions can be identified for realizing the

MDGs. Nevertheless, although progress has been

satisfactory in MDGs 1, 2, 3, 6 and 8, it has been

less in other areas, MDGs 4, 5 and parts of 7. At the

current pace of progress, Ghana may not meet the

MDG target by 2015 with business as usual. The

present MDG Acceleration Compact capitalizes

on the existing commitment and captures the

evidence available to put forward concrete and

realistic proposals to scale up the achievement of

the MDGs in the next five years…”

This MDG Acceleration Framework (MAF) – Ghana

Action Plan was developed by the Ministry of

Health and Ghana Health Service in collaboration

with development partners particularly the United

Nations Country Team and other stakeholders in

Ghana. The focus of the Action Plan is on MDG

5 because the progress in reducing the maternal

mortality ratio by three quarters by 2015 is off

track. The 2010 MDG Report showed the maternal

mortality rate to be at 451 per 100,000 live births. The

slow progress has been of great concern to policy

decision makers to the extent that Maternal Mortality

was declared a national emergency in July 2008.

Therefore, the main reason for this MAF is to redouble

efforts to overcome bottlenecks in implementing

interventions that have proven to have worked in

reducing the maternal mortality ratio in Ghana. The

MAF focuses on improving maternal health at the

level of both community and health care facilities

through the use of evidence-based, feasible and

cost-effective interventions in order to achieve

accelerated reduction in maternal and newborn

deaths. The three key priority interventions areas

identified are improving family planning, skilled

delivery and emergency obstetric and newborn care.

At the health facility level, emphasis is placed

on the creation of an enabling environment,

including equipment and supplies, for well-trained

professionals to attend to pregnancy, childbirth

and the newborn. The community level focuses on

FOREWORD

10

11

equipping communities with knowledge and skills

to enable them to adopt good health practices and

better health-seeking behaviour and to recognize

danger signs related to pregnancy and childbirth

as well as with the newborn. This document takes

cognizance of the inseparable dyad of the mother

and the newborn as well as the interrelationships

among all the eight MDGs.

The MAF is not aimed at replacing existing

interventions. Rather, it is meant to complement

them with specific focused interventions for the

achievement of MDG 5 by 2015. To achieve that,

the Ghana MAF cannot be the business of the

government alone, but requires the support of UN

agencies, other development partners and CSOs to

better understand the deep-rooted causes militating

against positive outcomes in maternal health care

and collectively work towards overcoming them.

Once the CAP is implemented with the support of all

stakeholders, Ghana will reduce the risks of maternal

deaths and once again be on track to achieving

MDG 5 by 2015.

The declaration of His Excellency Professor John

Evans Atta Mills, President of the Republic of Ghana at

the recent African Union Heads of State Conference

in Kampala, Uganda, that “no woman should die

while giving life” is a vision that the implementation

of this Action Plan seeks people to support it

through resource mobilization, implementation

and Monitoring and Evaluation.

Minister of Health, Ghana

Hon. Dr. Benjamin Kunbuor

UN Resident Coordinator

Ruby Sandhu-Rojon

1212

Making initial plans

and establishing baselines

STAGE 1:

INTRODUCTION

Photo: Kayla Keenan

CHAPTER 1:

13

1.1: BACKGROUND

Ghana, a tropical country on the west coast of Africa,

is divided into 10 administrative regions and 170

decentralized districts. The country has an estimated

population of about 23.4 million (GSS, 2009) with a

population density varying from 897 per km

2

in the

Greater Accra Region to 31 per km

2

in the Northern

Region. Life expectancy is estimated at 56 years for

men and 57 years for women, while the adult lit-

eracy rate (age 15 and above) stands at 65 percent.

The government is a presidential democracy with

an elected parliament and independent judiciary.

The principal religions are Christianity, Islam and

Traditional African. Ghana’s economy has a domi-

nant agricultural sector (small-scale peasant farm-

ing) absorbing 55.8 percent (GLSS 5) of the adult

labour force, a small capital intensive mining sector

and a growing informal sector (small traders and

artisans, technicians and businessmen). Since in-

dependence, Ghana has made major progress in

economic growth. However, a number of questions

arise as to how to accelerate equitable growth and

sustainable human development towards attaining

middle-income country status by 2015.

14

At the turn of the century, in September 2000, Ghana,

along with 189 UN member countries adopted the

Millennium Declaration that laid out the vision for a

world of common values and renewed determination

to achieve peace and decent standards of living for

every man, woman and child. The eight Millennium

Development Goals (MDGs) derived from the Millen-

nium Declaration set time-bound and quantifiable

indicators and targets aimed at halving the proportion

of people living below the poverty line, improving ac-

cess to primary education, promoting gender equality,

reducing child mortality, improving maternal health,

combating and reversing the trends of HIV/AIDS,

malaria and other diseases, ensuring environmental

sustainability, and promoting global partnership for

development between developed and developing

countries by 2015. This set of eight clear, measurable

and time bound development goals were expected

to generate unprecedented, coordinated action, not

only within the United Nations system, including the

Bretton Woods institutions, but also within the wider

donor community and, most importantly, within de-

veloping countries themselves.

Ghana has since mainstreamed the MDGs into the

country’s successive medium-term national develop-

ment policy framework, the Ghana Poverty Reduc-

tion Strategy (GPRS I), 2003 – 2005, and the Growth

and Poverty Reduction Strategy (GPRS II), 2006–2009.

The GPRS I focuses on macroeconomic stability, pro-

duction and gainful employment, human resource

development and the provision of basic services to

the vulnerable and excluded, and good governance;

GPRS II emphasizes continued macroeconomic sta-

bility, human resource development, private sector

competitiveness, and good governance and civic

responsibility. Within the same period of the two

development policy frameworks, Ghana benefited

from the Highly Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) initia-

tive and other international development assistance

support programmes including the Multilateral Debt

Relief Initiative (MDRI), Multi-Donor Budget Support

(MDBS) and the United States-funded Millennium

Challenge Account programme, among others.

In addition to direct poverty reduction expenditures,

government expenditure outlays were also directed

at policies and programmes to stimulate growth,

which have high potential to support wealth crea-

tion and sustainable poverty reduction.

Total poverty reduction expenditure as a percentage

of total government spending declined from 34.56

percent in 2006 to 22.82 percent in 2007 and further

down to 22.3 percent in 2008 (2008 APR). In terms

of sector shares, the largest share of total poverty

spending went to basic education, which accounted

for 41.42 percent in 2007 and 47.24 percent in 2008.

This was followed by health sector spending at 19.5

percent in 2007 and 18.05 percent in 2008. Expendi-

ture on rural electrification, water supply and feeder

roads ranged from 1.57 percent to 7.23 percent in

2007 and 1.36 percent to 5.04 percent in 2008. Such

declines in poverty spending have implications for

the achievement of the MDGs despite the country

being on track to achieve poverty and related targets

which form the focus of subsequent discussions.

1.2 OVERALL PROGRESS IN

ACHIEVING THE MDGS IN GHANA

According to the 2010 MDG Report, Ghana’s progress

in achieving the MDGs is mixed. The country is

largely on track to achieve the MDG 1 target of

reducing by half the proportion of the popula-

tion living in extreme poverty. The overall poverty

rate has declined substantially over the past two

decades from 51.7 percent in 1991–1992 to 28.5

percent in 2005–2006 while the proportion of the

population living below the extreme poverty line

also declined from 36.5 percent to 18.2 percent over

the same period against the 2015 national target of

26 percent and 19 percent respectively. Although

current data on poverty is not available, trends

in economic growth suggest a further decline in

poverty between 2006 and 2008. However, de-

spite the significant decline in poverty at the national

15

level, regional, occupational and gender disparities

exist. Some regions did not record improvements

in poverty, particularly the three Northern regions

where high levels of poverty persist. Over 70 percent

of people whose incomes are below the poverty line

live in the Savannah areas. The 2009 Human Develop-

ment Report (HDR) shows Ghana’s Human Develop-

ment Index (HDI) rank had declined and inequality

remained high. Thus the high growth rate has not

necessarily been consistent with improved human

development indicators as the country continues to

face challenges in health and other social services.

With regard to MDG 1 Target 1C, halving the propor-

tion of people who suffer from hunger, Ghana is on

course to achieving the child malnutrition indicators

ahead of 2015. The prevalence of children suffer-

ing from wasting and stunting that characterized

the late nineties continued to be reversed in 2008.

The incidence of wasting has declined from a peak

level of 14 percent in 1993 to 5.3 percent in 2008,

while the occurrence of underweight children has

declined from about 23 percent in 1988 to 13.9 per-

cent in 2008. In terms of districts facing chronic food

production deficits, the trend has seen continuous

reduction from 22 in 2005 to 15 in 2006, and further

down to 12 in 2008. These achievements were made

possible as a result of numerous programmes and

interventions implemented by government, includ-

ing fertilizer subsidies and the expanded maize and

rice programmes which supported farmers with

agricultural inputs (fertilizers, improved seeds), and

subsidies to meet ploughing and labour costs.

Available data and trend analyses of MDG 2 —

achieving universal primary education — show

that Ghana is on track to achieving both the

gross and net enrolment targets by 2015. The

number of schools and enrolment rates have in-

creased tremendously over the years due to various

reforms and new policy measures instituted by the

government. The number of kindergarten schools

has increased from 14,246 in 2006–2007 to 15,449

in 2007–2008 following the government’s policy of

mandating each primary school to have a kindergar-

ten attached to it. The Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER)

for kindergarten has subsequently increased from 89

percent in 2006–2007 to 89.9 percent in 2007–2008.

The number of primary schools rose from 16,903 in

2006–2007 to 17,315 in 2007–2008, while the GER

increased from 93.7 percent to 95.2 percent over the

same period. The area where challenges exist is the

survival rate which has stagnated at 88 percent in

2007–2008 from 85.4 percent in 2006–2007.

With regard to the MDG 3 target of ensuring gen-

der parity especially at the primary and junior

high school levels, trends show that Ghana is on

track to achieving both targets, although prima-

ry level parity has stagnated at 0.96 since 2006-

–2007, while the parity at the junior high school

level increased slightly from 0.91 in 2006—2007

to 0.92 in 2007–2008. On the other hand, the parity

at the kindergarten level has declined slightly from

0.99 in 2006–2007 to 0.98 in 2007–2008. Progress to-

wards increasing the number of women in public life

suffered a setback with the reduction of the number

of women elected into parliament during the 2008

elections declining from 25 to 20. This had reduced

the proportion to below 10 percent, and puts Ghana

under the international average of 13 percent.

Although evidence shows that there has been

signicant reduction in both infant and under-

ve mortality rates in Ghana, it is unlikely that

the 2015 target of reducing the child mortality

rates will be easily met. The Ghana Demographic

and Health Survey (GDHS) 2008 showed a 30 per-

cent reduction in the under-five mortality rate, as

it declined from 111 per 1,000 live births in 2003

to 80 per 1,000 live births in 2008, while the infant

mortality rate in 2008 stood at 50 per 1,000 live births

compared to 64 per 1,000 live births in 2003. The

neonatal mortality rate also saw a decrease from

43 per 1,000 live births in 2003 to 30 per 1,000 live

births in 2008. The proportion of children aged 12

to 23 months who received the measles vaccine

increased from 83 percent in 2003 to 90 percent in

16

2008, showing an improvement in coverage in one

of the key child survival interventions (MoH, 2008;

GHS, 2003).

The key child health interventions are antenatal care

(ANC), delivery care, postnatal care, immunization,

nutrition, management of childhood illnesses and

malaria prevention. In the last decade some progress

has been made to improve child survival. Household

ownership of insecticide-treated nets has improved

to 61.6 percent (urban) and 66 percent (rural) areas,

immunization coverage is high (Penta3 87 percent,

see GHS 2008

1

), National Health Insurance Scheme

(NHIS) coverage is high, antimalaria combination

therapy is universally available and infant and child

mortality have declined (see GSS 2008

2

; MICS

3

).

Maternal health care has improved over the past

20 years albeit at a slow pace. Between 1990 and

2005, maternal mortality ratio reduced from 740

per 100,000 live births to 503 per 100,000 live

births, and then to 451 per 100,000 live births

in 2008. If the current trends continue, maternal

mortality will be reduced to only 340 per 100,000 by

2015, instead of the MDG target of 185 per 100,000

by 2015. The improvement, however, is not the same

for all regions. There are disparities in the institutional

maternal mortality rate (MMR) across the 10 regions

in Ghana from 1992 to 2008 in the Northern and

Western Regions; 120.1 per 100,000 in Volta and the

Eastern Regions; and 59.7 per 100,000 in the Upper

West, Brong Ahafo and Ashanti regions. The only

region where the ratio has worsened is in Greater

Accra (by 87.6 per 100,000). Maternal death was

declared notifiable within seven days in Ghana in

January 2006 and the notification rate in 2007 was

71.8 percent. A quarter (75.4 percent) of 751 maternal

deaths in Ghana (2007) were audited.

After a decline from a high of 3.2 percent in 2006

to a low of 2.2 percent in 2008, evidence from

the 2009 Sentinel surveillance report suggests

an increase in the HIV/AIDS prevalence rate in

Ghana to 2.9 percent in 2009. According to the

Ghana AIDS Commission, the current up-and-

down movement in the prevalence rate between

2003 and 2008 signals a leveling eect or stabi-

lization of the epidemic.

On MDG 7 – ensuring environmental sustainabil-

ity – Ghana is on track to achieve the target of

halving the proportion of people without access

to safe water. Critical challenges exist in achieving

the targets for reversing the loss of environmental

resources, reducing the proportion of people with-

out access to improved sanitation, and achieving

significant improvement in the lives of people living

in slum areas. Although up-to-date data on the rate

of forest depletion is unavailable, evidence suggests

that the country is depleting its forest cover at an

alarming rate. Between 1990 and 2005, the forest

cover declined from 32.7 percent to 24.2 percent.

While access to safe water services in rural areas

has improved considerably, there has been slow

progress on access to safe water within urban areas.

Even though Ghana has made progress in reducing

the proportion of the population without access to

improved sanitation, the target may not be achieved

by 2015 if the current trends continue. If the current

trend is maintained, the proportion of the population

with access to improved sanitation will reach 21.2

percent by 2015 instead of 52 percent. The propor-

tion of the urban population with access to improved

sanitation will be 23.4 percent instead of 55 percent

by 2015, while in the rural areas, it would be only

20.6 percent instead of 50.5 percent. Also, though

the proportion of urban population living in slums

shows a decline, if the current pattern continues, a

significant proportion (about 14 percent) will still be

living in slum areas by 2020.

In terms of global partnerships for development,

many developed countries have not met the 0.7

percent GNP target for aid. However, aid inflows to

Ghana appear to have increased in nominal terms

from $578.96 million in 2001 to $1,433.23 million

in 2008. The current concern, however, is the level

1) GHS, Disease Control and Prevention Department 2008 Annual report.

2) GSS, Demographic and Health Survey 2008.

3) MoH, Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2006.

17

of increases in real terms and the quality of the aid

the country receives. In real terms, ODA inflows to

Ghana have stagnated at about 8.7 percent of GDP

between 2002 and 2008, after an initial rise from

6 percent of GDP in 1999 to 15 percent of GDP in

2001. The portfolio of aid inflows continued to be

dominated by project aid, which constitutes more

than 60 percent of ODA inflows. The global financial,

oil and food crisis appear to have impacted nega-

tively on the public debt position of Ghana, which is

gradually approaching unsustainable levels. Ghana’s

public debt as a percentage of GDP increased from

41.4 percent in 2006 to 55.2 percent in 2008.

1.3: Past and emerging

challenges and their impact on

achieving the MDGs

The global food and energy crisis, as well as the

effect of the global economic crisis and the presi-

dential and parliamentary elections between 2006

and 2008 adversely affected pro-poor expenditures.

While the debt relief fund for Highly Indebted Poor

Countries continued to fund activities in support of

both poverty reduction and growth enhancement,

the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative(MDRI) which

came into effect in 2006 addressed the energy crisis

as well.

Prior to the onset of the financial crisis, foreign in-

flows (export earnings, investment and remittances)

were buoyant. In the beginning of 2009, however,

the country recorded a budget deficit of 14.5 percent

of GDP excluding divestiture receipts, and 11.5 per-

cent of GDP including divestiture receipts; as well as a

large current account deficit of 20.87 percent of GDP.

The country faced a high base interest rate of 27.22

percent and an average annual inflation of 18.13

percent in 2008. Average depreciation recorded was

20.6 percent and 16.1 percent against the US dol-

lar and the Euro, respectively. Ghana’s high level of

dependence on the world economy, with as much

as 30 percent of budget support from international

partners, and her strong trade links with the US and

Europe, may imply that any disturbance emanating

from the international financial system is bound to

have an effect on the domestic economy. In terms of

international trade and foreign direct investment, the

global financial crisis does not show to have created

a major setback as far as Ghana is concerned. Gold

and cocoa, Ghana’s main exports, were resilient in

the face of the crisis and as a result of investments

in the oil and gas fields, foreign direct investment

has increased. It cannot therefore be argued that

developments in international trade and FDI nega-

tively affected the achievement of any of the MDGs

in Ghana. However, the crisis brought with it negative

consequences for the financial markets. Banks have

been reluctant to provide credit to households, to

small and medium enterprises (SMEs) as well as to

big businesses, for fear of loan defaults. In addition,

discount, interest, prime and lending rates have in-

creased. As far as the stock market is concerned, the

all-share index fell drastically and trade volume has

also decreased. These developments have affected

share prices paid to clients which may have further

affected incomes of households.

The impact of climate change is now more than

ever before being felt. There is clear evidence that

the potential negative impacts of climate change

are immense, and Ghana is particularly vulnerable

due to its lack of capacity to undertake adaptive

measures to address environmental problems and

the socio-economic costs of climate change (EPA,

2000). For instance, in agricultural areas, particularly

in the central and northern regions of the country,

climate change has contributed to the deterioration

of rural livelihoods, reflected in declining incomes,

malnutrition and hunger. The flooding of coastal

areas, which are already undergoing erosion, and low

operating water levels of the only hydro-generating

dam in the country are further problems. The vul-

nerability of people to daily shocks and stresses is

intrinsically tied to the human adaptive capacity —

and strategies created — to respond to floods, high

18

temperatures, coastal erosion, rises in the sea level,

and other climate-related events. Climate change

is likely to exacerbate these shocks and stresses,

particularly among the poorest and most vulnerable

populations and, therefore, may inhibit the attain-

ment of the MDGs. The evidence of the implications

of these phenomena for the attainment of the MDGs

in Ghana may have been underreported. It is impor-

tant that this is given the needed attention since

it has the potential of not only eroding the gains

already made, but also pf frustrating efforts being

made to achieve the goals.

1.4: THE MAF, CAP AND

OBJECTIVES

Various studies have indicated that globally achiev-

ing MDG 5 is off track and is not likely to be achieved

in many countries, Ghana included, as both targets

for measuring progress appear not to have been

reached so far. A number of reviews have been made,

challenges to implementation identified and various

recommendations made. The number of policy

documents, strategic plans and review reports on

maternal health and reducing maternal mortality

is very impressive. But implementation has almost

always stalled, leading to minimal impact on the

MMR. In the opinion of one of our development

partners, “Many action plans, initiatives and working

groups exist in Ghana to tackle MDG 5. We know

the specific interventions required to achieve MDG

5 — these are well detailed in the various plans and

initiatives. Several of these initiatives have been fully

costed, so we even have a sense of the resources

required. We do not require another action plan

specifying what interventions to carry out, nor do we

need another analysis of why maternal mortality is

high in Ghana.” He goes on to indicate that “what we

need is why the specific interventions have not been

implemented”. Unfortunately, these recommenda-

tions for implementing the proposed interventions

and overcoming identified bottlenecks are scattered

in many documents, making it difficult to monitor

the progress of implementation. As we approach

the target year of 2015, all the identified bottlenecks,

recommendations and action plans scattered in the

various documents need to be brought together to

help understand why the known specific interven-

tions were not implemented.

The MAF, introduced by the UN System, falls in line

with the concerns and priorities of the Government

of Ghana. Thus the selection of Ghana along with 10

countries (four in Africa — Ghana, Tanzania, Togo and

Uganda) to develop a Country Action Plan (CAP) or

the acceleration of MDG 5, which is off track. MDG 5

is not likely to be attained by 2015 if efforts are not

redoubled. The Ghana CAP contains the elaboration

of the key prioritized interventions that are required

to achieve MDG 5, identifies the bottlenecks to the

interventions and suggests cost-effective solutions

to address the bottlenecks and accelerate progress.

The CAP includes an implementation and monitor-

ing plan for tracking progress. This is expected to

enable Ghana to address the critical constraints that

hamper the progress towards achieving MDG5 and

put maternal mortality target back on track by 2015.

1.4.1: MAF objectives

The MAF aims at supporting national governments,

UN agencies and other development partners and

civil society organizations ( CSOs) working in the

MDG areas to better understand the key causes af-

fecting positive outcomes in a particular MDG, find

key solutions and develop an action plan that can

help to reduce the risks hampering progress of that

MDG. In the case of Ghana, the MAF objectives

seek to:

• reviewexistingpoliciesandinterventionsinthe

area of MDG 5 i.e., maternal health care;

19

• identifythekeybottleneckstotheimplementa-

tion and attainment of MDG 5;

• identifygapsinexistingpoliciesandinterventions;

• developcost-eectivesolutionsthatcanacceler-

ate progress towards the attainment of MDG 5;

• designanactionplanforimplementingtheindica-

tive interventions and monitor progress.

1.4.2: Methodology used in

preparing the MAF CAP

An interactive and participatory approach was

adopted for the MAF roll-out. A National Technical

Team was established and two resource persons

were recruited to manage day-to-day activities. A

desk review of national policy documents, reports

and roadmaps was undertaken covering 30 national

reports on maternal health care delivery and 37 Na-

tional Policy Documents. To fill in the information

gaps, focus group discussions and rapid survey ques-

tionnaires to District Directors of Health Services

were also carried out. Consultative meetings of the

technical team were organized to review the initial

findings (in terms of interventions and bottlenecks)

and answer the question: Why have the specific

interventions not been implemented? The key inter-

ventions, bottlenecks and solutions were prioritized

using the method of ranking (high/medium/low)

and selection criteria (impact, sustainability, speed,

resources). Based on the findings, the technical team

worked during workshops and consultations to de-

velop the draft CAP.

1.4.3: MAF consultative process

The process of the MAF roll-out, including the prepa-

ration of the CAP, was nationally driven, interactive

and participatory, and carried out under the overall

leadership of the MoH. Ownership was further en-

hanced by engaging multiple stakeholders drawn

from key sector ministries, CSOs, the UN Country

Team (UNCT) and development partners involved

in supporting maternal health care interventions.

Stages for the MAF roll-out and preparation of the

CAP were as follows:

A UNDP-led consensus building and introduction

of the MAF with the key government sector, MoH,

which in turn led to close consultation with key UN

agencies (WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, UNDP) to establish

an inter-agency National Technical Team. The Minis-

try of Health(MoH) and UN agencies identified the

MAF as timely and in line with their efforts to finding

a solution to the high maternal mortality in Ghana.

• AnationalproposalontheMAFroll-outwasde-

veloped and Ghana entered into a collaboration

with the global UNDP MAF team for financial,

technical and advisory support for the process.

• TheGovernmentofGhanaorganizedanincep-

tion meeting with selected partners including

the UNCT and agreed on the methodology and

identified bottlenecks for analysis, and reviewed

and adopted the action plan for MAF implementa-

tion.

• ANationalTechnicalTeamthatcomprisedthe

MoH, UNICEF, UNFPA, WHO and UNDP was es-

tablished by the MoH to support the MAF roll-

out. While the specialized UN agencies provided

technical inputs, UNDP played a coordinating role

and provided quality assurance.

• Twonationalconsultantswererecruitedtofurther

support the Technical Team and manage the day-

to-day process of the MAF roll-out.

• Initialactivitiesinvolved(i)adeskreviewofNa-

tional Policy Documents, reports and roadmaps

(30 national reports on maternal health care

20

delivery, 37 National Policy Documents). The re-

cently completed MDG Report for 2010 provided

additional data and information on the MDGs

including the impact (existing/potential) of the

global economic crises and climate change on the

attainment of the MDGs. Focused group discus-

sions and rapid survey questionnaires to District

Directors of Health Service were also conducted.

•

The National Technical Team with the consultants

and the UN inter-agency team, including a Re-

source Person from UNDP Regional Service Center,

Dakar, undertook a five-day working session in

Kumasi and reviewed the necessary interventions,

identified and prioritized bottlenecks as well as se-

quenced the solutions to remove the bottlenecks

for effective implementation to accelerate MDG 5.

• TheTechnicalTeamfurtherreconvenedinAccra

to prepare the draft CAP including the Monitoring

& Evaluation framework. At that point, additional

resource persons from UNDP Regional Bureau for

Africa (RBA) and Bureau for Development Policy

(BDP) joined the team to share global experiences

in the MAF process and provided technical inputs for

quality assurance in line with the global programme.

• TheNationalTechnicalTeambriefedUNCTaday

prior to the validation meeting to share the find-

ings, and received inputs for consideration mainly

in the areas of nutrition, gender empowerment,

girls’ education, HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted

infections in pregnancy and childbirth.

• On12August2010,avalidationmeetingwas

organized with the wider stakeholders to discuss

and build consensus on the draft MAF CAP. The

validation provided further comments and recom-

mendations that further enhanced the quality and

ownership for the CAP. In all, 15 Agencies and 35

participants were represented.

• TheNationalTechnicalTeam,includingtheUN

Country Team, incorporated stakeholders’ com-

ments and contributions into the MAF CAP.

• Thedocumentwasdulyendorsedandnalizedas

a true reflection of Ghana’s MAF National Action

Plan for the acceleration of MDG 5 over the next

five years until the target date of 2015.

From the review of the existing policies and interven-

tions available for attaining MDG 5 in Ghana, the

team assessed the implementation status (whether

partially or not implemented) and the expected con-

tributions to the acceleration of MDG 5. It identified

and ranked the various interventions by using the

following set of criteria: impact, sustainability, speed,

coverage and available capacity for the intervention.

The three key interventions that emerged as having

great impact on maternal health were family plan-

ning (FP); skilled delivery services (SD); and emer-

gency obstetrics and neonatal care (EmONC).

Using the above three key intervention areas, the

team identified and prioritized the key bottlenecks

by answering questionnaires and ranking the bot-

tlenecks as high, medium or low/small, in the areas

of policy/planning, financing, service delivery, service

utilization and cross-cutting on the interventions.

The bottlenecks that emerged from this ranking

included accessibility, availability, coverage, knowl-

edge, acceptance, poverty, quality and intersecto-

ral coordination. Using available costing, the team

developed cost-effective solutions for the three in-

terventions to accelerate progress of MDG 5 using

‘accelerating solutions prioritization criteria’ based

on impact (magnitude, speed and sustainability)

and feasibility (governance, capacity and funding

availability).

The outputs from the overall MAF process included

(i) an analysis of the national-, regional- and

district-level constraints to implementing the

well-defined actions required to make progress on

MDG 5, with emphasis on answering the question:

21

Why have the specific interventions not been im-

plemented; (ii) a two-to-three-year business plan/

CAP outlining how all stakeholders could work to-

gether to implement the various plans and initiatives.

The CAP elaborates on key prioritized interventions

that are required to achieve MDG 5, identifies the

bottlenecks, and suggests cost-effective solutions

to address the bottlenecks and accelerate progress.

It also contains an implementation and monitoring

plan for tracking progress. All these are with a view

to addressing the critical constraints that hamper

progress towards reducing maternal mortality in

Ghana and once again put the country on track to

achieving MDG 5 by 2015.

1.4.4: September 2010 MDG

Summit

In September 2010, 10 years after the historical event

of the MDG declaration in 2000, the global leaders

involved in formulating the declaration met again to

review the progress made, and galvanized political

commitment and collective action towards the 2015

deadline. In line with the country’s own concerns and

plans, Ghana was selected by the UN system along

with 10 countries (four in Africa — Ghana, Tanzania,

Togo and Uganda) to develop a CAP for the accelera-

tion of MDG 5. The results of the pilot, which was part

of a synthesis report, was tabled at the 2010 MDG

Summit in September 2010 in New York.

PROGRESS AND CHALLENGES

IN ACHIEVING MDG 5

Photo: Kayla Keenan

CHAPTER 2:

23

2.1: OVERVIEW OF MDG REPORT

2010 ON MDG 5 MATERNAL

MORTALITY IN GHANA

Although Ghana has achieved progress in the past

10 years of MDG implementation, challenges of in-

equalities, geographical disparities and sustaining

progress still remain. With only five years remaining

to the MDG deadline, Ghana will have to accelerate

its efforts towards the achievement of all the MDGs,

especially those lagging behind such as MDG 4 (child

mortality), MDG 5 (maternal health) and part of MDG

7 (environment). The death of a mother, especially

during pregnancy, is a calamity for the family, com-

munity and society at large, something that has

been long accepted by all societies. Consequently,

it has been a concern of the international commu-

nity and various governments to initiate policies,

programmes and strategies to improve maternal

health and reduce maternal mortality and morbidity.

Unfortunately, the MMR is just too high in developing

countries, including Ghana, and the indicator is ac-

cepted as a key to assessing the level of development

of a particular country. While the MMR in developed

regions was 9 per 100,000 live births in 2008, the ratio

was 450 per 100,000 in developing regions (MDG

Report 2010). Obviously, a lot needs to be done in

developing regions to bring down the MMR if MDG

5 is to be achieved.

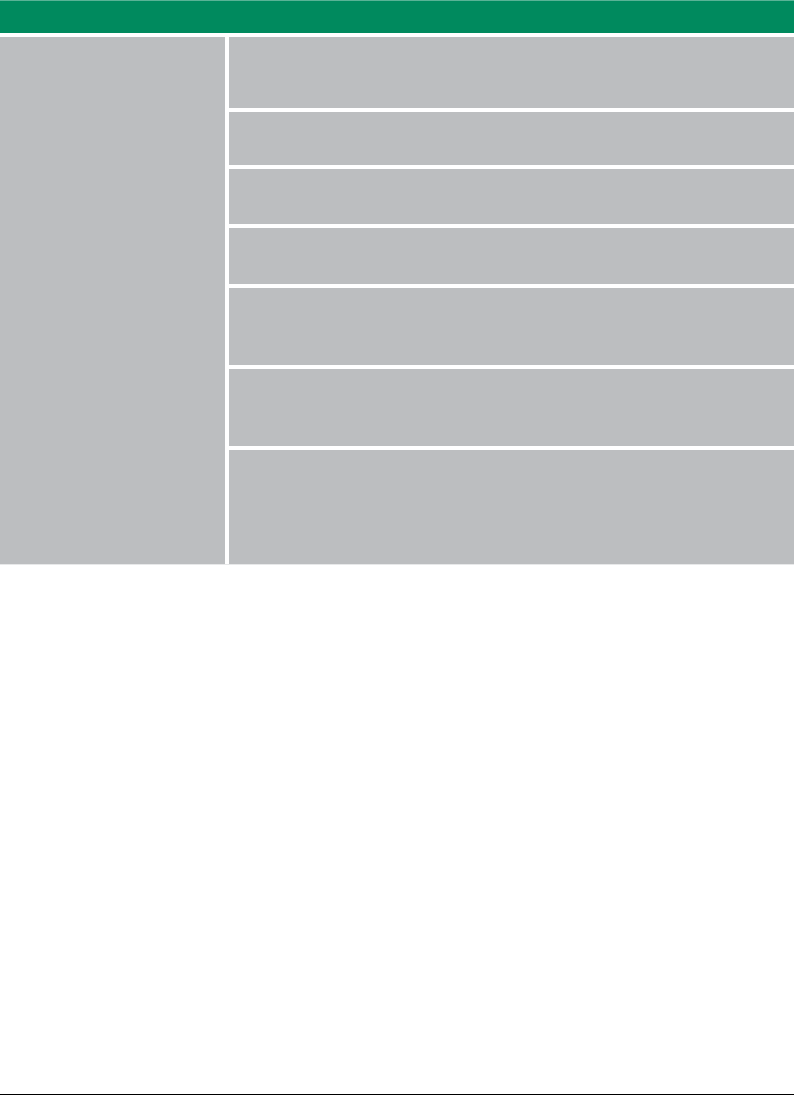

The MMR as captured by both survey and insti-

tutional data has shown an improvement over

the past 20 years. However, the pace has been

slow. Between 1990 and 2005, it reduced from

740 to 503 per 100,000 live births and then to 451

deaths per 100,000 live births in 2008. This trend

is also supported by institutional data which suggest

that maternal deaths per 100,000 live births have

declined from 224 per 100,000 in 2007 to 201 per

100,000 in 2008, after an increase from 187/100,000

in 2004 to 197 per 100,000 in 2006. If the current

trends continue, maternal mortality will be reduced

to only 340 per 100,000 by 2015 instead of the MDG

target of 185 per 100,000 by 2015. Moreover, the

improvements recorded are not evenly distributed.

There are disparities in the MMR (institutional) across

the 10 regions in Ghana from 1992 to 2008. The MMR

has decreased to 195.2 per 100,000 in the Central and

Upper East regions; 141 per 100,000 in the Northern

and Western Regions; 120.1 per 100,000 in Volta and

the Eastern Regions; and 59.7 per 100,000 in the

Upper West, Brong Ahafo and Ashanti regions. The

only region where the MMR has worsened is Greater

Accra (by 87.6 per 100,000) (fig. 2). This shows a clear

inequity in the per capita distribution of health facili-

ties and health personnel across the various regions

and districts and underscores the need to improve it.

Unless extreme efforts are made by all stakeholders,

Ghana is unlikely to meet the MDG target (fig.1). The

Ghana Maternal Health Survey 2007 found that 14

percent of deaths of women within the reproductive

age are childbirth-related and identified hemorrhage

(24 percent) as the largest single cause of maternal

deaths; abortion was the second single largest cause

of death, accounting for 15 percent. Hypertensive

disorders, sepsis, and obstructed labour were also

cited as causes of maternal death.

The MMR remains unacceptably high in Ghana in

spite of the efforts being made to reduce it. Maternal

health has remained a national priority and as such,

has become a core indicator for poverty reduction

in the Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy (GPRS).

Additionally, improving maternal health and thereby

reducing maternal mortality is one of the priorities

of the health sector’s programme of work (POW).

24

Figure 1 TRENDS IN MATERNAL MORTALITY

Source: Ghana’s Health Sector Review Report, 2009; MOH, 2008.

740

503

451

150

250

350

450

550

650

750

1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Maternal Mortality Rate (per 100,00 live births)

Survey

Survey Path to Target Linear Trend

216

187

197

224

201

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015

Maternal Mortality Rate (per 100,00 live births)

Instuonal

Instuonal Path to Target Linear Trend

25

Source:

Centre for Health Information Management

Ministry of Health

Northern (141.9)

Brong Ahafo (59.7)

Ashanti (42.7)

Volta (113.9)

Western (130.2)

Eastern (120.1)

Upper West (42.4)

Upper East (179.2)

Central (195.2)

Greater Accra (-87.6)

Baseline

Current Status

Portion of target met

Portion remaining

Maternal Mortality Ratio - Institutional

Change in affected population 1992 - 2008

Condition worsened by -87.6 per 100,000

Improved by up to 59.7 per 100,000

Improved by up to 120.1 per 100,000

Improved by up to 141. per 100,000

Improved by up to 195.2 per 100,000

Prepared for National Planning Commission (Ghana)

By African Centre for Statistics, UNECA

April 2010

Figure 2 MAP OF INSTITUTIONAL MATERNAL MORTALITY RATIO IN GHANA

BY REGION

26

While acknowledging the importance of focusing on

MDG 5, we also recognize that all the eight MDGs

are interrelated and mutually reinforcing. Poverty,

gender inequality, low productivity, inadequate

income opportunities, poor education, environ-

mental non-sustainability are all undermined

if health care is poor and the reverse is true in

some cases. For instance, MDGs 4, 5 and 6 are close-

ly linked. The mother is the fulcrum around which

family life revolves and her death jeopardizes the

survival of her young children. For example, the risk

of death for children under five is higher for those

whose mothers die in childbirth than those with

living mothers. Reducing death in pregnancy and

childbirth does not only improve the productivity

of women, and increase labour supply and the eco-

nomic well-being of communities, but is arguably

also a human r

ights issue. Given the numerous is-

sues that beset maternal health care leading to slow

progress in achieving MDG 5, and the inter-linkages

between improved maternal health and MDG 4, the

MAF roll-out in Ghana chose to focus on MDG 5. The

status of the MDGs in Ghana over the last 10 years

is shown in table 3.

2.2: OVERALL ASSESSMENT OF

PROGRESS TOWARDS MDG 5

Policy measures for improving health care services

in general, and maternal care in particular, are en-

shrined in the national development policy frame-

works including the GPRS I, GPRS II and the draft

Medium-Term National Development Policy Frame-

work 2010–2013 as well as specific health sector poli-

cies. Furthermore, Ghana has numerous initiatives in

place to address the issue of maternal mortality but

the results have not led to desirable improvement

in MDG 5. Particular initiatives put in place to ad-

dress the high levels of maternal deaths include the

Safe-Motherhood Initiative, Ghana Vitamin A Supple-

ment Trials (VAST) Survival Programme, Prevention

of Maternal Mortality Programme (PMMP), Making

Pregnancy Safer Initiative, Prevention and Manage-

ment of Safe Abortion Programme, Intermittent

Preventive Treatment (IPT), Maternal and Neonatal

Health Programme and the Roll Back Malaria Pro-

gramme. However, funding and other cross-cutting

constraints have hampered the full implementation

of some of the initiatives.

Resource allocation to the health sector in nominal

terms has increased over the years. However, as a

percentage of the national budget it declined from

16 percent in 2006 to about 12.76 percent in 2009.

TABLE 1 HEALTH BUDGET 20062009

Year 2006 2007 2008 2009

MoH 478,654,800 563,756,400 752,233,368 921,929,472

National budget 2,948,398,300 3,869,832,200 5,059,808,063 7,226,913,484

Total share of health in the

national budget 16.23% 14.60% 14.90% 12.76%

Source: Annual Budget Statement, MoH, Government of Ghana.

27

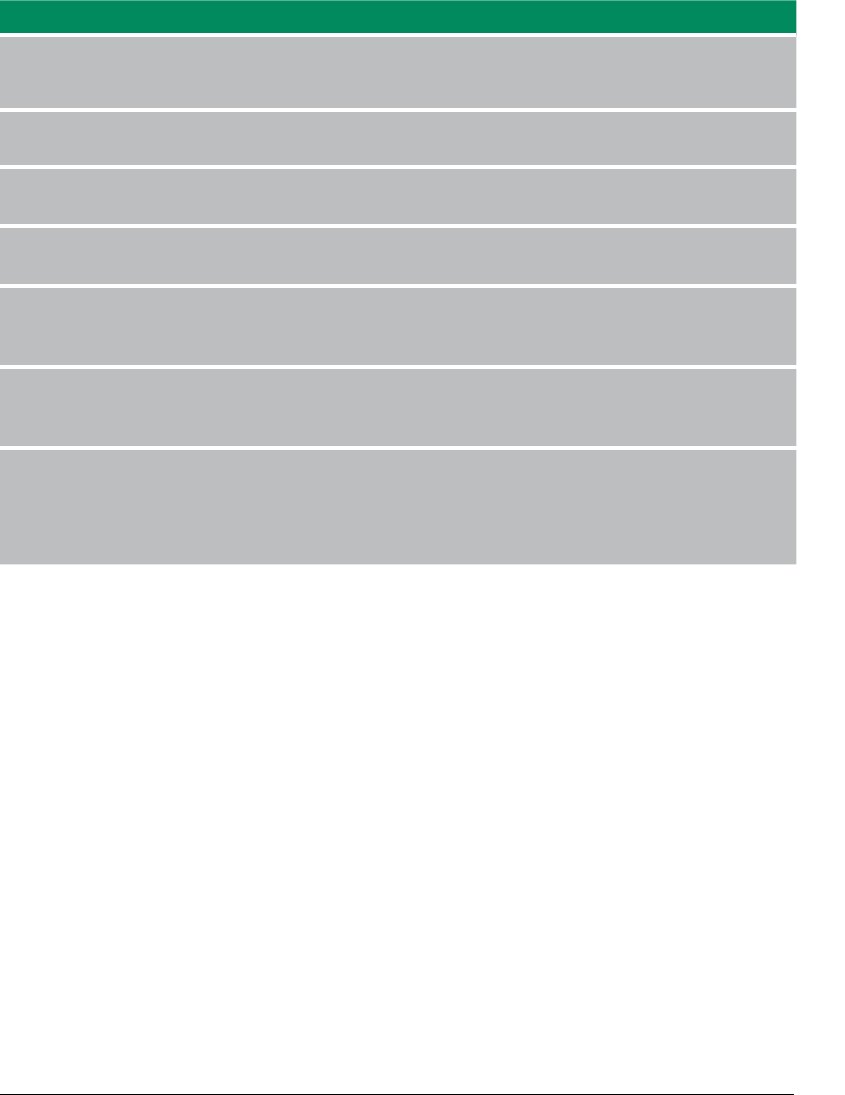

Apart from the general bottlenecks that affect the

entire health system of the country, there are also

specific urban and rural challenges with implica-

tions for maternal mortality. Antenatal care from

health professionals (nurses, doctors, midwives

or community health officers) increased from 82

percent in 1988 to 95 percent in 2008 (see figure

3). However, the progress is unevenly distributed.

While women in urban areas receive more antenatal

care from health professionals (98 percent) than

their rural counterparts (94 percent) the regional

figures are different: 96 percent to 98 percent of

women across all the regions received antenatal

care from health professionals. The exception is

women in Volta and the Central regions whose

antenatal care access rate is estimated at 91 percent

and 92 percent respectively. However, the lack of

information available to women about signs of

complications in pregnancy, and access to basic

laboratory services, particularly in the Northern and

Upper West regions, affect the quality of antenatal

care. In the Northern and Upper West regions, only

six in 10 pregnant women, and two in three have

access to urine testing and blood testing respec-

tively. These are against the national average of 90

percent access to these services.

Figure 3 SELECTED INDICATORS OF REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH CARE,

19882008

Source: Ghana Statistical Service (2005, 2008), Ministry of Health (2006).

28

Deliveries that were assisted by a health profes-

sional recorded slow progress, increasing from

40 percent in 1988 to 59 percent in 2008. In the

Northern region, one in four compared to four in

five children in the Greater Accra region are likely

to be delivered in a health facility. Professional

assistance at birth for women in urban areas was

found to be twice as likely to occur as in rural

areas (MOH, 2008a). The available data show that

over 40 percent of women did not deliver in a

health facility because some of them thought

it was unnecessary to do so, while others cited

lack of money, accessibility problems like distance

to a health facility, transportation problems, not

knowing where to go, and the unavailability of

someone to accompany them to the facility. The

Reproductive and Child Health Policy recom-

mends a minimum of four visits per client and a

haemoglobin check at registration and at term.

The four-plus visit coverage has stayed below

60 percent against the target of 80 percent and

the proportion of women whose haemoglobin is

checked at term remains below 10 percent.

While puerperal sepsis is a significant cause of

maternal deaths, postnatal care coverage has per-

sistently remained low and stagnated between 53

percent and 56 percent from 2001 to 2007 (fig. 4).

Figure 4 POSTNATAL CARE COVERAGE

FP prevents unwanted pregnancy and reduces the

risk of maternal deaths from pregnancy-related com-

plications and unsafe abortions. But the FP acceptor

rate has seen only a marginal rise from 21.2 to 25.4

percent of women in their reproductive age between

2007 and 2009. Greater Accra and the Western and

Ashanti regions have particularly low acceptor rates.

The Upper West and Brong Ahafo regions record

the highest FP acceptor rates (fig. 5). The preferred

methods are Depo (44.3 percent), male condom

(27.7 percent), combined pills (15.9 percent) and

injectable Norigynon.

54.2

53.4

55.7

53.3

55

53.7

56.7

50

52

54

56

58

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Postnatal Care Coverage(%)

29

Figure 5 FAMILY PLANNING ACCEPTOR RATE BY REGION, 20072009

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

AS BA CR ER GAR NR UE UW VR WR NAT

2007

2008

2009

Figure 6 DEMAND FOR FAMILY PLANNING AMONG CURRENTLY MARRIED

WOMEN

30

Ghana has a National Contraceptive Security (CS)

Strategic plan, supported by a Financial Sustain-

ability Plan (FSP). In 2007, however, there was a “near

crisis” in the supply of male condoms as the country

almost ran out of stock of Neo Sampoon spermicide,

which is the most preferred type. The demand for

FP among currently married women is 59 percent,

out of which only 24 percent have their demand

satisfied and 35 percent have an unmet need (fig.

6). The main challenges in FP include contraceptive

security issues (funding gap in procurement, and in

information, education and communication) and

method-specific issues (low patronage of contracep-

tive devices such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) and

female condoms due to low male involvement and

fear of side effects). The current funding requirement

(2010–2012) prior to the MAF process is estimated

at $41.2 million as shown in table 2.

TABLE 2 TOTAL CONTRACEPTIVE FUNDING REQUIREMENTS BY PROGRAMME, 20102012

IN MILLIONS USD

Product 2010 2011 2012 Total

MoH (PPAG/MBI) 11.6 8.4 13.5 33.5

EXP SM 2.9 2.4 2.4 7.7

TOTAL 14.5 10.8 10 41.2

The Community Health Planning and Service (CHPS)

was initiated in Ghana in 2000 to bridge the equity

gap in health services by partnering health pro-

vider and community efforts, to bring health services

closer to the doorstep of households. It involves

subdividing sub-districts (15,000–30,000 population)

into zones with a population of 2,000 to 5,000, as-

signing trained health workers, providing them with

logistics and with support from community health

volunteers, delivering preventive and curative care

and in some cases midwife services. Currently, it is

estimated that 2,200 CHPS zones are functional in

Ghana (fig. 7). While the concept is good, it is chal-

lenged by inconsistent targeting (both in numbers

and in relation to the Ghana poverty map), lack of

human resources and very often a different interpre-

tation of what constitutes a functional CHPS zone.

31

Behavioural change communication (BCC) is another

key initiative to create awareness about pregnancy

risk factors and danger signs, and increase demand

and utilization of antenatal services, SD services,

EmONC and postnatal care. The programme uses

the media to inform, educate and communicate

messages to promote the adoption of desired be-

haviours; prints posters, leaflets and fliers; engages in

advocacy; involves traditional leaders and religious

leaders and groups, and so on. Recently, with support

from UNICEF, the Health Promotion Department of

the Ghana Health Service (GHS) developed a com-

mon framework for behavioural change termed

‘Communication for Development’ (C4D).

The high maternal mortality in the country was de-

clared a national emergency in 2008 and therefore

emphasized the need to assign a higher priority to

reproductive health services. Unfortunately, resource

allocation was not aligned to match this good pol-

icy declaration. Furthermore, there is no systematic

tracking of set targets such as focused antenatal

care coverage, the percentage of facilities offering

basic emergency obstetric care (BEOC), the percent-

age of districts offering comprehensive emergency

obstetric care (CEOC), and the percentage of districts

with transfusion service. Issues of accessibility often

emerge as a bottleneck for pregnant women, par-

ticularly in rural areas. Sometimes, pregnant women

are not able to afford transport or do not know where

to access maternal health services.

Figure 7 VARIATIONS IN CHPS DEPLOYMENT TARGETING

0 0 0 0

73

-58

-38

-62

-22

-56

-16

-19

-14

5

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 )2015

CHPS Deployment Differences in Target

Yearly difference

32

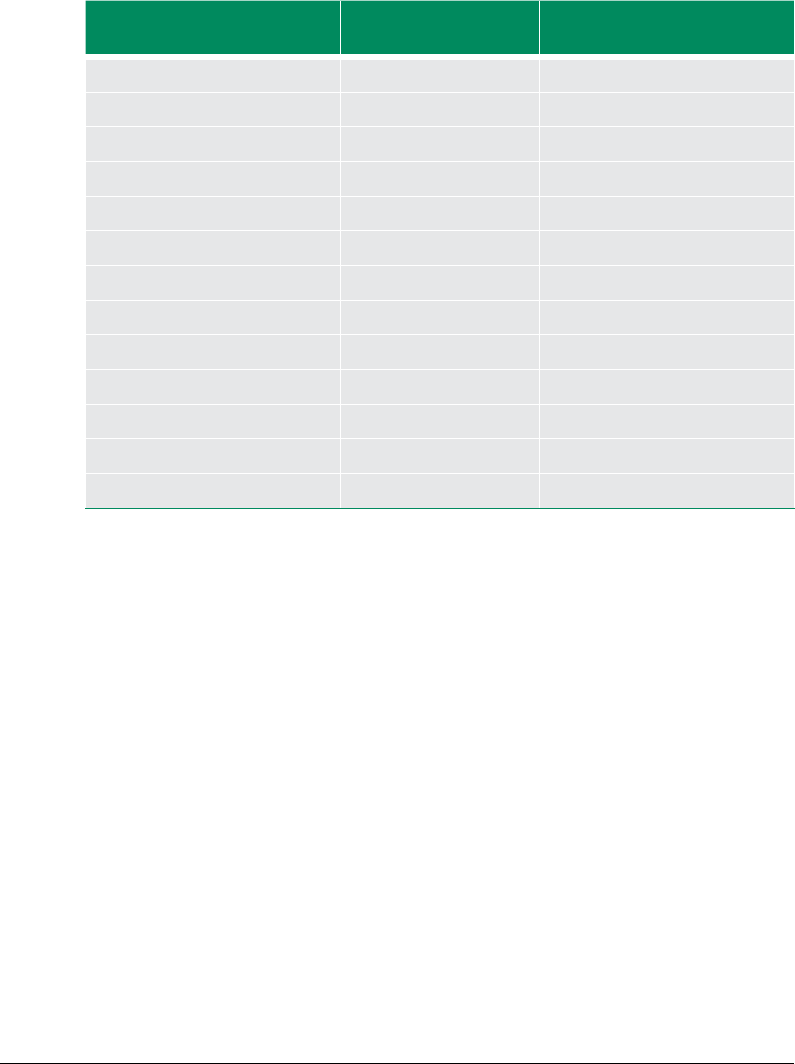

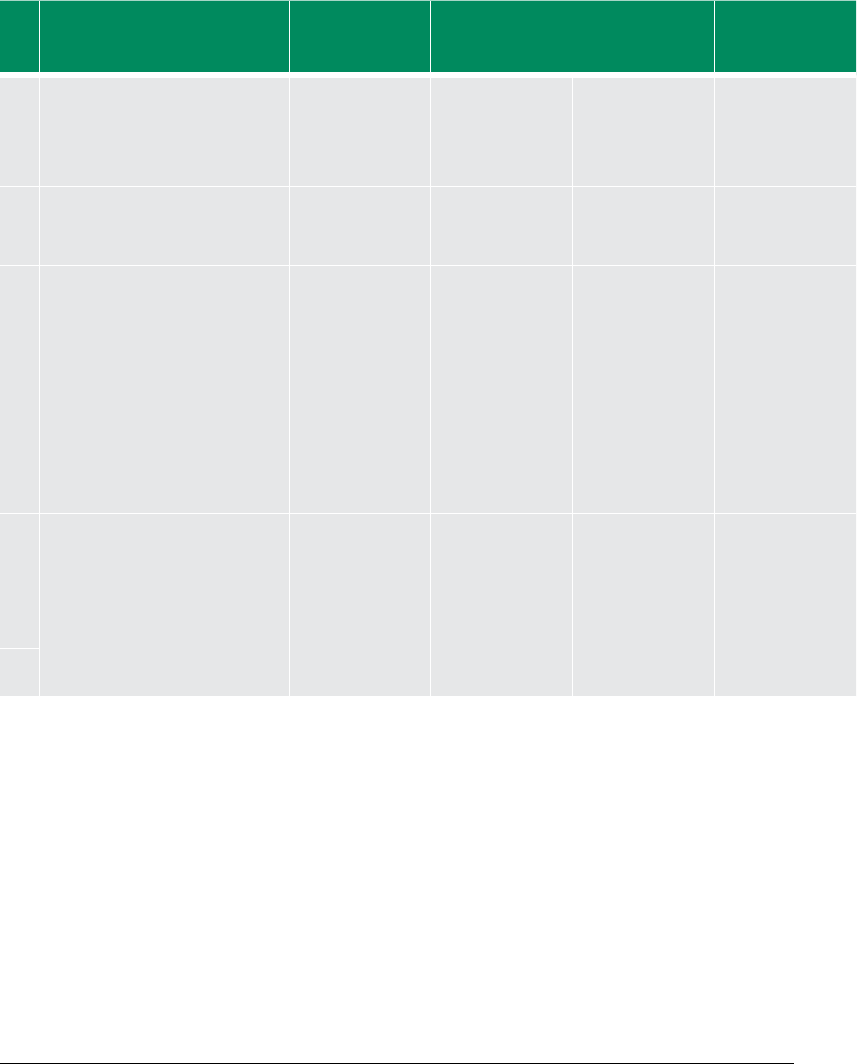

TABLE 3 STATUS OF MDGS AND TRENDS TOWARDS ACHIEVING THEM

Goals/Targets Indicator Indicator Status MDG Target

1999 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2015

Goal 1. Eradicate Extreme

Poverty and Hunger

a. Halve the proportion of

people below the extreme

poverty line by 2015

b. Halve the proportion of

people who suer from hunger

Proportion below

extreme poverty

(national basic needs) line (%)

Proportion below

upper poverty line (%)

Proportion of children

malnourished (%)

-Underweight

- Stunting

- Wasting

26.8

39.5

23 (1988)

34

(1988)

9

(1988)

-

-

23

33

(1993)

14

(1993)

-

-

20 (1998)

31

(1998)

10.0

(1998)

-

-

18

35

8

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

18.0

28.5

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

13.9

28

9

18.5

25.8

15.5

15

3.8

Goal 2: Achieve Universal

Primary Education

Achieve universal access to

primary education by 2015

- Gross enrolment ratio (%)

- Net primary

enrolment ratio (%)

- Primary completion/

survival rate (%)

72.7 (1990)

54 (1990)

63 (1990)

79.5 (2000)

61 (2000)

63 (2000)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

83.2

85.7

59.1

82.6

92.1

69.2

75.6

93.7

81.1

85.4

95.2

83.7

88.0

100

100

100

Goal 3: Promote Gender

Equality and Empower Women

a. Eliminate gender disparity in

primary and junior secondary

education by 2009

b. Achieve equal access

for boys and girls to senior

secondary by 2009

Ratio of females to males in

primary schools (%)

Ratio of females to males in

junior secondary schools (%)

Ratio of females to males in

senior secondary schools (%)

Percentage of female

enrolment in senior secondary

schools (%)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

0.92

0.88

-

-

0.77

0.88

-

-

0.93

0.88

-

-

0.95

0.88

-

43.5

0.95

0.88

-

49.5

0.96

0.91

-

-

0.96

0.92

-

-

1.0

1.0

-

-

33

TABLE 3 STATUS OF MDGS AND TRENDS TOWARDS ACHIEVING THEM

Goals/Targets Indicator Indicator Status MDG Target

1999 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2015

Goal 1. Eradicate Extreme

Poverty and Hunger

a. Halve the proportion of

people below the extreme

poverty line by 2015

b. Halve the proportion of

people who suer from hunger

Proportion below

extreme poverty

(national basic needs) line (%)

Proportion below

upper poverty line (%)

Proportion of children

malnourished (%)

-Underweight

- Stunting

- Wasting

26.8

39.5

23 (1988)

34

(1988)

9

(1988)

-

-

23

33

(1993)

14

(1993)

-

-

20 (1998)

31

(1998)

10.0

(1998)

-

-

18

35

8

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

18.0

28.5

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

13.9

28

9

18.5

25.8

15.5

15

3.8

Goal 2: Achieve Universal

Primary Education

Achieve universal access to

primary education by 2015

- Gross enrolment ratio (%)

- Net primary

enrolment ratio (%)

- Primary completion/

survival rate (%)

72.7 (1990)

54 (1990)

63 (1990)

79.5 (2000)

61 (2000)

63 (2000)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

83.2

85.7

59.1

82.6

92.1

69.2

75.6

93.7

81.1

85.4

95.2

83.7

88.0

100

100

100

Goal 3: Promote Gender

Equality and Empower Women

a. Eliminate gender disparity in

primary and junior secondary

education by 2009

b. Achieve equal access

for boys and girls to senior

secondary by 2009

Ratio of females to males in

primary schools (%)

Ratio of females to males in

junior secondary schools (%)

Ratio of females to males in

senior secondary schools (%)

Percentage of female

enrolment in senior secondary

schools (%)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

0.92

0.88

-

-

0.77

0.88

-

-

0.93

0.88

-

-

0.95

0.88

-

43.5

0.95

0.88

-

49.5

0.96

0.91

-

-

0.96

0.92

-

-

1.0

1.0

-

-

34

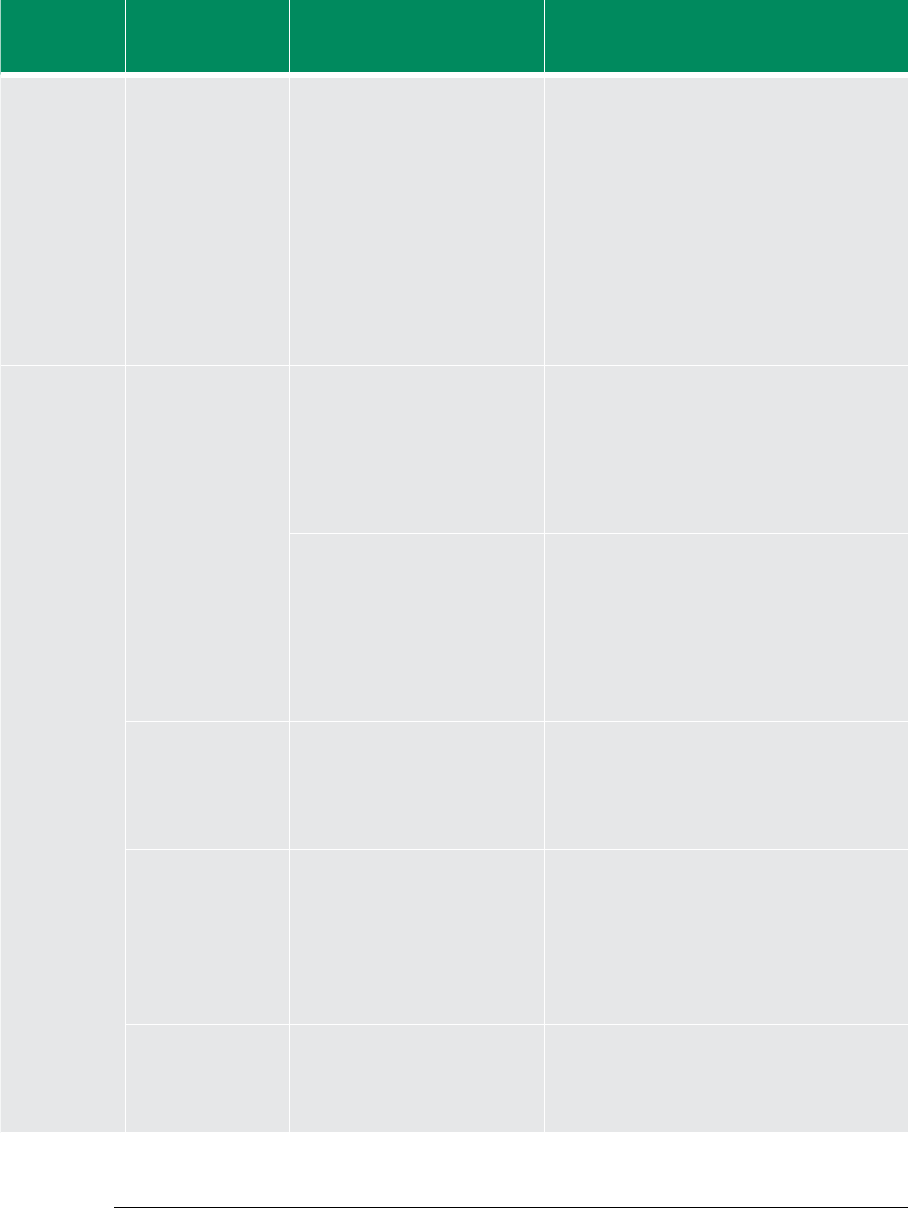

Goals/Targets Indicator Indicator Status MDG Target

1999 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2015

Goal 4: Reduce Child Mortality

Reduce under-ve mortality by

two-thirds by 2015

- Under-ve mortality rate

(per 1,000 live births)

- Immunization coverage (%)

122

(1990)

61

(1990)

110

(1995)

70

(2000)

109

(2000)

-

111

83

-

-

-

84

111

85

-

89

80

90

39.88

100

Goal 5. Improve Maternal

Health

Reduce maternal mortality

ratio by three quarters by 2015

- Maternal mortality per

100, 000 live births (survey)

- Maternal mortality

per 100, 000 live births in

health facilities (institutional)

- Births attended by skilled

health personnel (%)

740

(1990)

216

(1990)

40

(1988)

-

260

44

(1993)

-

204

44

(1998)

-

205

47

-

187

-

503

205

-

-

197

48

-

224

-

451

201

59

185

54

100

Goal 6. Combat HIV/AIDS &

Malaria, and Other Diseases

a. Halt and reverse the spread

of HIV/AIDS by 2015

b. Halt and reverse the

incidence of malaria

National HIV prevalence

Rate (%)

Under-ve malaria case

fatality (Institutional) (%)

1.5

-

2.9

-

3.4

2.9

3.6

2.8

3.1

2.7

2.7

2.4

3.2

2.1

2.6

-

2.2

-

≤1,5

-

35

Goals/Targets Indicator Indicator Status MDG Target

1999 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2015

Goal 4: Reduce Child Mortality

Reduce under-ve mortality by

two-thirds by 2015

- Under-ve mortality rate

(per 1,000 live births)

- Immunization coverage (%)

122

(1990)

61

(1990)

110

(1995)

70

(2000)

109

(2000)

-

111

83

-

-

-

84

111

85

-

89

80

90

39.88

100

Goal 5. Improve Maternal

Health

Reduce maternal mortality

ratio by three quarters by 2015

- Maternal mortality per

100, 000 live births (survey)

- Maternal mortality

per 100, 000 live births in

health facilities (institutional)

- Births attended by skilled

health personnel (%)

740

(1990)

216

(1990)

40

(1988)

-

260

44

(1993)

-

204

44

(1998)

-

205

47

-

187

-

503

205

-

-

197

48

-

224

-

451

201

59

185

54

100

Goal 6. Combat HIV/AIDS &

Malaria, and Other Diseases

a. Halt and reverse the spread

of HIV/AIDS by 2015

b. Halt and reverse the

incidence of malaria

National HIV prevalence

Rate (%)

Under-ve malaria case

fatality (Institutional) (%)

1.5

-

2.9

-

3.4

2.9

3.6

2.8

3.1

2.7

2.7

2.4

3.2

2.1

2.6

-

2.2

-

≤1,5

-

36

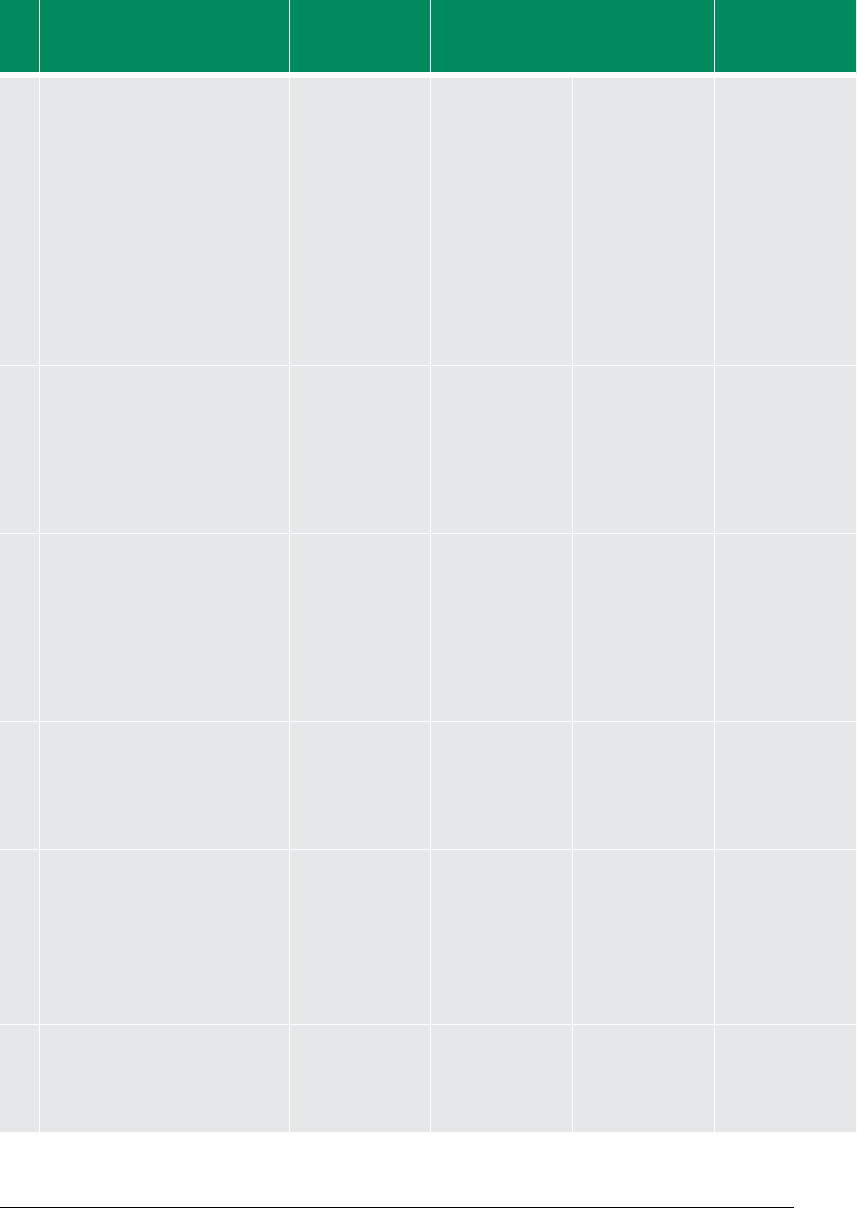

Goals/Targets Indicator Indicator Status MDG Target

1999 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2015

Goal 7:

Ensure Environmental

Sustainability

a. Integrate the principles

of sustainable development

into country policies and

programmes and reverse the

loss of environmental resources

b. Halve the proportion of

people without access to safe

drinking water

by 2015

a. Proportion of

land area covered by

forest (ha/annum)

b. Annual rate of

deforestation (%)

Proportion of population with

access to safe drinking water (%)

-Urban

-Rural

Proportion of population with

access to improved sanitation (%)

-Urban

-Rural

Population with access to

secure housing (%)

Population living in slums (%)

6,229,400

(27.4 % of

total land

area)

1.82

(135,400 ha)

56

(1990)

86

(1990)

39

(1990)

-

-

-

-

27.2 (1990)

-

1.89

(115,400 ha)

67

(1993)

90

(1993)

54

(1993)

4

(1993)

10

(1993)

1

(1993)

-

25.5

-

-

70

(1998)

94

(1998)

63

(1998)

5

(1998)

11

(1998)

1

(1998)

-

-

-

-

69

83

55

8

15

2

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

5,517,000

(24.3% of

land area)

1.7

(93,789 ha)

-

-

-

-

-

-

11

21

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

11.4

20.7

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

12

20

-

-

83.8

93

76.6

12.4

17.8

8.2

12.5

19.6

≥7,448,000 ha

≤1.82%

78

93

69.5

52

55

50.5

18.5 (2020)

<13

37

Goals/Targets Indicator Indicator Status MDG Target

1999 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2015

Goal 7:

Ensure Environmental

Sustainability

a. Integrate the principles

of sustainable development

into country policies and

programmes and reverse the

loss of environmental resources

b. Halve the proportion of

people without access to safe

drinking water

by 2015

a. Proportion of

land area covered by

forest (ha/annum)

b. Annual rate of

deforestation (%)

Proportion of population with

access to safe drinking water (%)

-Urban

-Rural

Proportion of population with

access to improved sanitation (%)

-Urban

-Rural

Population with access to

secure housing (%)

Population living in slums (%)

6,229,400

(27.4 % of

total land

area)

1.82

(135,400 ha)

56

(1990)

86

(1990)

39

(1990)

-

-

-

-

27.2 (1990)

-

1.89

(115,400 ha)

67

(1993)

90

(1993)

54

(1993)

4

(1993)

10

(1993)

1

(1993)

-

25.5

-

-

70

(1998)

94

(1998)

63

(1998)

5

(1998)

11

(1998)

1

(1998)

-

-

-

-

69

83

55

8

15

2

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

5,517,000

(24.3% of

land area)

1.7

(93,789 ha)

-

-

-

-

-

-

11

21

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

11.4

20.7

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

12

20

-

-

83.8

93

76.6

12.4

17.8

8.2

12.5

19.6

≥7,448,000 ha

≤1.82%

78

93

69.5

52

55

50.5

18.5 (2020)

<13

38

Goals/Targets Indicator Indicator Status MDG Target

1999 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2015

Goal 8: Develop a Global

Partnership for Development

Deal comprehensively

with debt and make debt

sustainable in the long term

Public debt ratio (% of GDP)

External

Domestic

Total

External debt service as a

percentage of exports of

goods & services

ODA Inows (% of GDP)

Total

Programme Aid

152.8

(2000)

28.9

(2000)

181.65

(2000)

7.8

(1990)

6

30

114.8

26.8

141.61

10.1

15

39

105.4

28.5

133.85

10.2

8

58

100.7

20.5

121.26

5.2

9

49

73

21.2

94.18

5.6

10

40

59.6

18.8

78.35

5.8

9

35

17

24.4

41.42

3.2

8.1

37.6

24.6

26.2

50.87

-

8.1

31

27.7

27.5

55.2

4.3

8.6

37

-

-

-

-

-

-

Source: Ghana MDG Report 2010.

* As reported in MoH-MNCH Strategy (2009–2015).

** MoH has changed the target from 80 percent to 55 percent in the MNCH Strategy (2009-2015).

***Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Forestry Sector Strategy.

39

Goals/Targets Indicator Indicator Status MDG Target

1999 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2015

Goal 8: Develop a Global

Partnership for Development

Deal comprehensively

with debt and make debt

sustainable in the long term

Public debt ratio (% of GDP)

External

Domestic

Total

External debt service as a

percentage of exports of

goods & services

ODA Inows (% of GDP)

Total

Programme Aid

152.8

(2000)

28.9

(2000)

181.65

(2000)

7.8

(1990)

6

30

114.8

26.8

141.61

10.1

15

39

105.4

28.5

133.85

10.2

8

58

100.7

20.5

121.26

5.2

9

49

73

21.2

94.18

5.6

10

40

59.6

18.8

78.35

5.8

9

35

17

24.4

41.42

3.2

8.1

37.6

24.6

26.2

50.87

-

8.1

31

27.7

27.5

55.2

4.3

8.6

37

-

-

-

-

-

-

STRATEGIC

INTERVENTIONS

Photo: Kayla Keenan

CHAPTER 3:

41

3.1: STRATEGIC INTERVENTIONS

OF HIGH IMPACT FOR THE

ACHIEVEMENT OF MDGS

Most of the interventions that have been pursued

to curb the high incidence of maternal mortality

over the years are similar to those for under-five