May 2024

National Strategy to Improve

Maternal Mental

Health Care

TASK FORCE ON MATERNAL MENTAL HEALTH

i

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 1

The National Strategy to Improve Maternal Mental Health Care: Pillars, Priorities,

and Recommendations .................................................................................................................................. 3

Background ............................................................................................................................................... 3

U.S. Maternal Mental Health .................................................................................................................... 3

Risk Factors and Disparities Addressed in the National Strategy ............................................................. 4

Barriers Related to the Lack of a Supportive Infrastructure and Environment ......................................... 5

Policies Contributing to Stigma and Fears of Parent–Child Separations .............................................. 6

Workforce Shortages and Difficulties Accessing Services ................................................................... 7

A Fragmented Health Care System ....................................................................................................... 8

Lack of Systemic Supports During Postpartum Challenges ................................................................. 9

The Perinatal Period: An Opportunity to Address Mental Health Conditions and SUDs ...................... 10

Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 11

The Audience, Scope, and Vision for the National Strategy .................................................................. 14

Audience ............................................................................................................................................. 14

Scope ................................................................................................................................................... 14

Vision .................................................................................................................................................. 15

Call to Action ...................................................................................................................................... 15

Recommendations from the Task Force on Maternal Mental Health ......................................................... 16

Pillar 1: Build a National Infrastructure That Prioritizes Perinatal Mental Health and Well-Being ....... 16

Pillar 2: Make Care and Services Accessible, Affordable, and Equitable .............................................. 29

Pillar 3: Use Data and Research to Improve Outcomes and Accountability........................................... 42

Pillar 4: Promote Prevention and Engage, Educate, and Partner with Communities .............................. 50

Pillar 5: Lift Up Lived Experience .......................................................................................................... 55

Conclusion .................................................................................................................................................. 61

Appendix A: Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................... A-i

Appendix B: Language Used in This National Strategy ............................................................................ B-i

Appendix C: Task Force Roster ................................................................................................................. C-

i

Federal Staff Members ........................................................................................................................... C-i

Nonfederal Staff Members ................................................................................................................... C-iv

Appendix D: References ............................................................................................................................ D-i

Appendix E: Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................ E-i

Per academic and publishing standards, this document includes bibliographic citations and other attributions to printed and

digital sources and other research materials. This report has also been reviewed with industry-standard plagiarism-screening

software. All flagged instances of potential previously published material have been thoroughly researched and, where

appropriate, cited or attributed accordingly. This report incorporates information obtained from publicly solicited comments

through FR Doc. 2023-28890

and from hundreds of subject matter experts, and where possible, this document cites or attributes

this information appropriately. However, federal solicitations for public comment make possible the incorporation of information

or text from unpublished sources or other sources, which may not be cited or attributed herein.

1

Executive Summary

Maternal mental health conditions, substance use disorders (SUDs), and their co-occurrence have reached

crisis levels in the United States and are among the most common complications of pregnancy. Suicide,

drug overdose, and other incidents and conditions related to mental health and SUDs are the leading cause

of pregnancy-related deaths. The lack of sufficient U.S. infrastructure (i.e., environment, policies,

systems, and programs) and workforce capacity makes it challenging to support maternal mental health

holistically. Although best practices have been developed to address some aspects of the problem, they

have not been implemented uniformly. Because a national infrastructure and workforce capacity are

lacking, our system does not deliver the right care at the right time to all who experience maternal mental

health conditions and SUDs. The lack of a robust infrastructure is an important factor that shapes a

national landscape in which these conditions often remain undetected and untreated. This results in

negative consequences for individuals, their children, their families, and their communities and a high

cost for our nation. Moreover, these conditions and associated negative outcomes disproportionately

affect subgroups with challenging social determinants of health (e.g., economic difficulties, food and

diaper insecurity, experiences of discrimination, a lack of stable housing, a lack of access to

transportation, a lack of access to child care, and a lack of access to health care and insurance) and life

situations (e.g., having these conditions prior to pregnancy and experiencing gender-based violence and

other traumas).

Aligned with broader efforts to address women’s overall health and maternal health across the nation,

Congress directed the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) either to form the Task

Force on Maternal Mental Health or to incorporate specified duties, public meetings, and reports into

existing relevant federal committees or workgroups (

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 [Public Law

117–328, Section 1113]). The Secretary of HHS determined that these duties, public meetings, and

reports should be incorporated into SAMHSA’s Advisory Committee for Women’s Services (ACWS).

ACWS’s Task Force on Maternal Mental Health is a panel of experts from multiple complementary

disciplines—some of whom have lived experience—who represent federal and nonfederal organizations

with a bearing on care for maternal mental health conditions and SUDs. This national strategy features

the ACWS’s task force’s recommendations for a whole-government approach to build the

necessary infrastructure to improve care for maternal mental health conditions and SUDs. The

recommendations in this strategy represent the general consensus of the task force. Single

recommendations may not have the full support of the more than 100 organizations represented by the

members of the task force.

A companion report, The Task Force on Maternal Mental Health’s Report to Congress, provides a

detailed discussion of the U.S. maternal mental health crisis, the task force’s methods, best practices,

existing federal programs and coordination, and feedback from listening sessions with state and local

stakeholders.

The vision set forth by this national strategy is one in which maternal mental health (also known as

perinatal mental health) and substance use care is seamless and integrated across medical,

community, and social systems. The vision includes models of care and support that are innovative and

sensitive to individuals’ experiences, culture, and community and does not distinguish between physical

health care and mental health care. Building upon existing federal government efforts, the task force

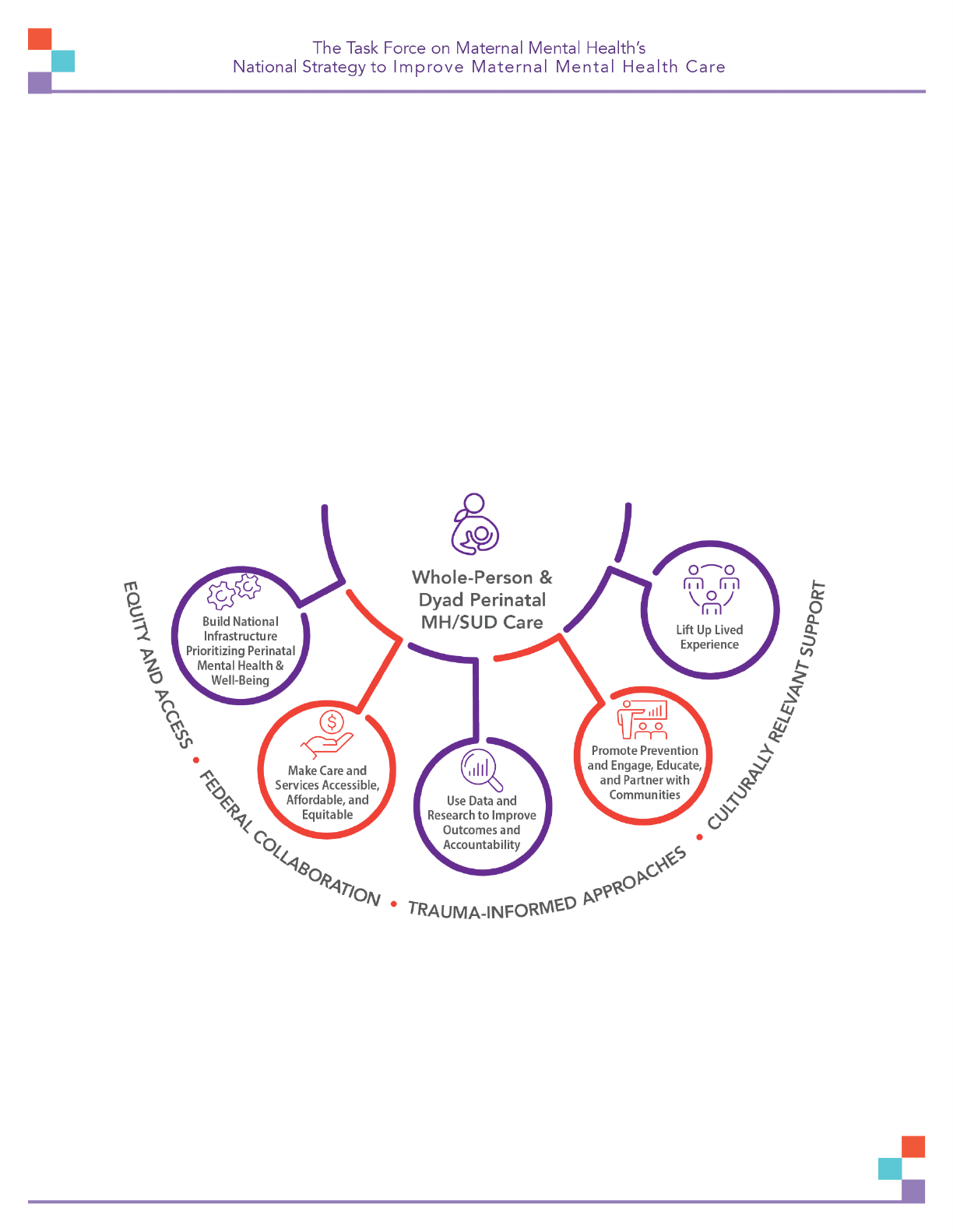

outlines a path to achieve the vision within a framework consisting of the following five pillars, each with

supporting priorities and recommendations.

2

1. Build a national infrastructure that prioritizes perinatal mental health and well-being,

which entails establishing and enhancing federal policies that promote perinatal mental health and

well-being—with a focus on reducing disparities—and federal policies that promote care models

from multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary teams that integrate perinatal care and mental health

and SUD care with holistic support for mother–infant dyads and their families.

2. Make care and services accessible, affordable, and equitable, which will advance the

implementation of culturally relevant and trauma-informed clinical screening, improve linkages

to accessible early intervention and treatment, create accessible and integrated evidence-based

services that are affordable and reimbursable, and build capacity by training, expanding, and

diversifying the perinatal mental health workforce.

3. Use data and research to improve outcomes and accountability, which encompasses the

evidence-driven support of strategies and innovations that improve outcomes and build a

foundation for accountability in prevention, screening, intervention, and treatment.

4. Promote prevention and engage, educate, and partner with communities, which will involve

promoting and funding prevention strategies, elevating education of the public about perinatal

mental health and substance use, and engaging communities with outreach and communications.

5. Lift up lived experience, which includes listening to the perspectives and voices of people with

lived experience and prioritizing their recommendations (many of which overlap with those of the

task force) as outlined in a specially prepared report by the U.S. Digital Service and summarized

in this national strategy.

The five pillars of this national strategy highlight the cross-cutting imperatives of (1) increasing equity

and access, (2) improving federal coordination, (3) elevating culturally relevant supports, and (4) using

trauma-informed approaches to bolster maternal mental health and enhance care for perinatal mental

health conditions and SUDs. The national strategy also spotlights evidence-based, evidence-informed, and

promising practices (e.g., programs) with supporting resources and expertise that can be scaled up for

widespread implementation. Throughout, the task force points out opportunities for the federal

government to collaborate with diverse groups of partners to spearhead the implementation of the national

strategy and lift up the voices of people with lived experience (highlighted in quotation marks). Finally,

the task force notes that this national strategy is a living document that will be regularly updated. It

focuses on ways that the federal government can lead efforts, but it also calls upon many types of partners

(e.g., states, advocates, medical and professional societies, and individuals with lived experience) to help

build the necessary infrastructure to support the mental health and well-being of the nation’s mothers and

their children, families, and communities.

3

The National Strategy to Improve Maternal Mental

Health Care: Pillars, Priorities, and

Recommendations

Background

The ACWS’s Task Force on Maternal Mental Health sets forth this national strategy and the

accompanying report to Congress to address an urgent national public health crisis. As these documents

demonstrate, maternal mental health conditions are among the most common complications of pregnancy.

Currently, the United States does not have the infrastructure, systems, policies, or workforce in place to

support optimal maternal mental health for everyone. Without a supportive infrastructure and

environment, the nation will not be able to address the high prevalence and negative consequences of

maternal mental health conditions, substance use disorders

(SUDs), and their co-occurrence. This national strategy

features the task force’s recommendations for the federal

government to enhance internal, public–private, and state

collaboration and coordination to build the necessary

infrastructure to spearhead efforts to improve care for

maternal mental health conditions and SUDs.

U.S. Maternal Mental Health

Mental health conditions and SUDs during pregnancy and the postpartum period affect an estimated 1 in

5 individuals annually in the United States (American Psychiatric Association, 2023). Maternal mental

health conditions (e.g., mood disorders, anxiety disorders, trauma-related disorders, obsessive-compulsive

disorder, and postpartum psychosis) and SUDs range in type and severity (American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2023; Clarke et al., 2023). Preexisting maternal mental health conditions

and SUDs, including serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorders, may

be affected by pregnancy and the postpartum period with risk of increased relapses (Taylor et al., 2019).

When left untreated, maternal mental health conditions and SUDs can have long-lasting negative effects

on individuals and families—with costs estimated to be more than $14 billion a year in the United States

(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.-a, n.d.-f; Jahan et al., 2021; Luca et al., 2020; Lupton et

al., 2004; Mughal et al., 2019; Prince et al., 2024). For example, research links maternal perinatal

depression and anxiety with problems in children’s social–emotional, cognitive, language, motor, and

adaptive behavior development, all the way into adolescence (Rogers et al., 2020). Ongoing research is

examining the complex biological mechanisms underlying these

links (e.g., elevated maternal glucocorticoids, alteration of

placental function and perfusion, and epigenetic mechanisms)

(Lewis et al., 2015). In our current system, most individuals who

experience maternal mental health conditions and SUDs do not

receive treatment (Byatt et al., 2015; Lynch et al., 2021).

Moreover, clinical screening—one way that these conditions can

be detected—is not typically provided for the most prevalent

conditions (e.g., perinatal depression) (Britt et al., 2023).

The unmet need for treatment of maternal mental health conditions and SUDs has reached a crisis point.

From 2017 to 2019, suicide, drug overdose, and other incidents and conditions related to mental health

and SUDs were the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States—accounting for 22.7

percent of these deaths (Trost, Beauregard, Chandra, Njie, Berry, et al., 2022). By comparison, the next

“Maternal mental health, also known

as perinatal mental health, is a

[person’s] overall emotional, social,

and mental well-being during and after

pregnancy” (Zuloaga, 2020).

“In Massachusetts, we had two

local moms who [died by suicide]

in postpartum 2 to 3 days after

birth and one after a month. It’s on

every new mom’s mind.”

- A provider who coordinates

new-mom groups

4

leading causes of pregnancy-related deaths were hemorrhage (13.7 percent), cardiac and coronary

conditions (12.8 percent), and infection (9.2 percent) (Trost, Beauregard, Chandra, Njie, Berry, et al.,

2022). Pregnancy-related deaths from suicide, drug overdose, and other causes related to mental health

conditions and SUDs are discussed in greater detail in the report to Congress. Here, the task force notes

that these deaths are often preventable, are marked by disparities, and occur up to 1 year postpartum

(Trost, Beauregard, Chandra, Njie, Berry, et al., 2022; Trost, Beauregard, Chandra, Njie, Harvey, et al.,

2022). These findings have heightened attention to the mental health of pregnant and postpartum

individuals and the care and services landscape in the United States. Concern about maternal mental

health conditions and SUDs is further amplified by broader initiatives in response to the high overall U.S.

maternal mortality rate—which is the highest among high-income countries despite our spending the most

on health care per person (Gunja et al., 2023; Hoyert, 2024).

Risk Factors and Disparities Addressed in the National Strategy

The perinatal period is a time of intense physical and emotional demands and physiological and social

changes. Although the factors underlying the risk for mental health conditions, substance use, and SUDs

are complex and multifactorial (e.g., biological factors, environmental factors, and components that entail

the interaction of biological and environmental factors), the task force highlights a number of subgroups

at high risk because they experience challenging situations and stressors. These challenges and stressors

can contribute to mental health conditions, substance use, and SUDs that occur prior to pregnancy and

precipitate onset or relapse during the perinatal period. Therefore, these subgroups are briefly mentioned

here and have been integrated throughout the recommendations of this national strategy.

Subgroups at high risk for these conditions include individuals who are members of the under-resourced

and underserved populations highlighted in “Language Used in This National Strategy,” such as under-

resourced racial and ethnic groups. Additional subgroups at high risk for these conditions include

individuals who are incarcerated; parents of children in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs); people

who have experienced pregnancy loss, forcible displacement, trafficking, or gender-based violence

(GBV); active-duty service members; veterans; and people with preexisting mental health conditions and

SUDs, including those with severe mental illness (Shah & Christophersen, 2010). As described in the

report to Congress, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and trauma

*

are highly prevalent and can be

associated with negative and lasting effects on the risk for mental health conditions and SUDs—

particularly if experienced during childhood, if experienced multiple times, and if treatment is not

received (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.-g; Feriante & Sharma, 2024; Substance Abuse

and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015). The report to Congress also details the intersection of

experiencing ACEs and trauma, including GBV, with maternal mental health conditions and SUDs. The

special considerations for supporting people who experience GBV in general and intimate partner

violence (IPV) in particular are noted throughout this national strategy. For example, the discussion under

some recommendations mentions that not everyone has safe family members or personal networks to

support them during the perinatal period. Because of the high prevalence of ACEs and trauma—including

IPV and other types of GBV—the task force underscores the need for providers, programs, and

organizations to be educated about trauma-informed approaches and to implement them in health care and

services (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.-c; D’Angelo et al., 2022; Foti et al., 2023;

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014).

*

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood—such as abuse or

neglect, experiencing or witnessing violence, household challenges, bullying, and parental mental health and/or

substance use problems [CDC, 2023

]. Trauma is a mental health concern that occurs among individuals who have

experienced an event or circumstance resulting in physical, emotional, and/or life-threatening harm [SAMHSA,

2022].

5

Trauma-Informed Approaches

A trauma-informed approach to care encompasses services that incorporate an understanding of trauma

and an awareness of the impact it has. It also views trauma through a cultural lens and recognizes that

context influences the perception and processing of traumatic events. Importantly, trauma-informed care

anticipates and avoids retraumatizing processes and practices (Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration, 2023).

Of note, when assessing for concerns around trauma, including GBV, traditional screening practices are

not often the best fit, because the goal is not to detect or diagnose but rather to create trauma-informed

safe spaces to enable individuals to discuss their concerns and experiences openly with their providers,

who can then offer support and resources and address any immediate safety concerns.

Challenging life situations and barriers that influence maternal mental health and the risk for maternal

mental health conditions and SUDs often considerably overlap with negative social determinants of health

(SDOH).

†

When discussing maternal mental health conditions and SUDs in the national strategy, the task

force considers SDOH—particularly along the lines of race/ethnicity, educational attainment, income

level, and geographic location, as well as their interaction—as these social drivers tend to accumulate

over the life course, be associated with risk factors, and contribute to the marked health disparities and

inequities in the United States (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021; Puka

et al., 2022). Maternal mental health conditions, substance use, and SUDs disproportionately affect Black

and American Indian/Alaska Native

women and other people in under-

resourced communities (Policy Center

for Maternal Mental Health, 2023a,

2023b). Negative SDOH (e.g., economic

difficulties, food and diaper insecurity,

experiences of discrimination, lack of

stable housing, lack of access to

transportation, lack of access to child

care, and lack of access to health care

and insurance) during the perinatal

period can be enormously stressful and

may contribute to maternal mental health

conditions and SUDs. Subgroups that are

at high risk for maternal mental health

conditions and SUDs also often face

challenges related to SDOH and

systemic barriers to receiving the

supports and care they need (discussed

below in “Barriers Related to the Lack of

a Supportive Infrastructure and

Environment”).

Barriers Related to the Lack of a Supportive Infrastructure and

Environment

This national strategy and its recommendations need to be understood in the context of the systemic

barriers that those who are pregnant and those who are postpartum face. These barriers are not the fault of

†

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn,

work, play, worship, and age that influence health risks and outcomes” [Healthy People 2030].

Accessing Maternity Care Can Be Difficult

• The United States has a critical and growing shortage of

obstetric care providers. More than 2.2 million people

who are of childbearing age live in a maternity care

desert, defined as “any county … without a hospital or

birth center offering obstetric care and without any

obstetric providers” (March of Dimes, 2022). More than

one-third of U.S. counties are designated as maternity

care deserts, and two-thirds of those are in rural

counties (March of Dimes, 2022).

• According to the Policy Center for Maternal Mental

Health, 96 percent of birthing-aged women in the United

States live in an area with a shortage of maternal mental

health professionals. The majority (70 percent) of U.S.

counties lack sufficient maternal mental health

resources (Britt et al., 2023).

• Women in nearly 700 counties face a high risk for

maternal mental health disorders, and more than 150

counties are “maternal mental health dark zones,” with

both high risk and large resource gaps (Britt et al., 2023).

6

the individual. Rather, they occur because the United States lacks the infrastructure and environment

needed to sufficiently support maternal mental health and well-being. An overarching barrier is that

mental health conditions and SUDs in general are seen as nonmedical and are therefore more likely to be

misunderstood, stigmatized, and perceived to be outside the purview of the health care system. Because of

this erroneous classification, mental health conditions and SUDs do not have the same research base,

reimbursement parity, and focus in the medical and health care system. They tend to be addressed in

different care systems. This overarching issue is magnified in the context of maternal mental health. Both

providers, including clinicians (Clarke et al., 2023), and community-based non-clinicians lack specific

education about these conditions. Additionally, stigmatization of people who experience perinatal mental

health conditions and SUDs can affect whether individuals seek care and how they are treated in the

health care and social service systems (Cantwell, 2021; O’Connor et al., 2022). The topic of stigma and

maternal mental health conditions and SUDs is discussed in more detail in the report to Congress.

Policies Contributing to Stigma and Fears of Parent–Child Separations

The perception that mental health conditions and SUDs are nonmedical persists, and their stigmatization

continues. Stigma toward people with SUDs manifests in punitive policies (Adams & Volkow, 2020).

Evidence indicates that family separation, criminalization, and incarceration for SUD during pregnancy is

ineffective at deterring substance use and is harmful to the health of pregnant people and their infants

(American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2020; Office of National Drug Control Policy,

2022). Yet service providers in many states are mandated to report

substance use by pregnant and postpartum individuals. Some state

statutes also have implications for mandated “test and report”

policies—i.e., urine toxicology testing for substances during the

perinatal period and reporting to child protective services. State or

county child protective service departments may take the extreme

measure of removing a child from a parent’s custody. Such policies are often applied in ways that

disproportionately affect Black women—for example, testing them even if they do not have a history of

substance use (Jarlenski et al., 2023). Punitive policies related to child removal also apply to women with

mental health conditions (such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and other mental health

conditions involving psychosis). In the context of experiencing IPV, abusive partners may use punitive

policies as a means of continued control and coercion, as discussed in the report to Congress. Such

policies leave many individuals in understandable fear and cause them to mistrust service providers and

organizations. These factors affect treatment seeking and willingness to have honest conversations about

mental health and substance use (Alderdice & Kelly, 2019; Choi et al., 2022; Megnin-Viggars et al.,

2015; O’Connor et al., 2022). People with lived experience of maternal mental health conditions and

SUDs voice these concerns. (See “Pillar 5: Lift Up Lived Experience.”)

Federal laws (the

Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment

Act [CAPTA]) require states to create policies that

address child abuse and neglect. State policies (such as

mandatory reporting), procedures, and investigation

systems vary across many dimensions, including how

states implement

plans of safe care (POSCs), a

requirement of the Comprehensive Addiction and

Recovery Act (CARA; Public Law 114–198), which

amended CAPTA. POSCs focus on the shared

responsibility of child welfare, hospitals, service

providers, child care and early childhood education

settings, and others to promote the health and well-being

of infants and their caregivers in the context of parental

SUDs (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2022).

“I was terrified my kids would

be taken away from me.”

- S.B., mother of two

Highlighted Resource: The National

Center on Substance Abuse and

Child Welfare Technical Assistance

The National Center on Substance Abuse

and Child Welfare offers technical

assistance (e.g., trainings, videos, and

webinars) to localities on how to

implement CAPTA POSCs. The assistance

is

designed to improve (1) the safety and

well-being of infants affected by prenatal

substance exposure and (2) the recovery

outcomes for their caregivers.

7

Typically, a designated local agency (e.g., child protection services or a public health agency) develops an

individualized POSC for a family that is designed to foster the recovery of any parent with SUD while

ensuring the safety and well-being of the child (or children). POSCs aim to keep children in their homes

with their birth parents when that can be accomplished safely (Office of National Drug Control Policy,

2022), and POSCs should enforce notification (as opposed to reporting) pathways in which maternal

substance use is noted to facilitate appropriate linkages to services and follow-up.

Society and professionals have a duty to keep children safe. In the current policy climate, providers are

concerned about children and the risk of harm and neglect, as well as losing their licenses to practice if

they do not comply with policies. However, the fear that parents with mental health conditions or SUD

have of mandatory reporting of maternal mental health symptoms and substance use to child welfare

services and the possibility of their children being removed from their homes and placed in foster care is a

barrier to their seeking SUD treatment (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2022). In line with the

Biden–Harris administration’s report titled Substance Use Disorder in Pregnancy: Improving Outcomes

for Families, it is crucial that policies, procedures, and practices support family preservation and parental

access to treatment while keeping children safe. Additionally, the racial bias in parent–child separations

must be addressed. In addition to seeing this issue in their professional experience, members of the task

force heard this concern in listening sessions with staff members from state and local agencies and in the

public comments generated by a request for information

. The National Center on Substance Abuse and

Child Welfare offers resources to help providers understand policies and how to implement POSCs.

Ultimately, there are multilayered contributing factors to these punitive policies and practices, and

solutions need to involve greater educational investment and cross-disciplinary collaboration among

policymakers, hospital administrators, health care providers, community leaders, and people with lived

experience.

Workforce Shortages and Difficulties Accessing Services

The shortage of obstetric providers and the lack of a national infrastructure for maternal health care,

services, and supports are systemic barriers that put undue stress on pregnant and postpartum individuals

(March of Dimes, 2022). Additionally, our nation has a chronic shortage and geographic maldistribution

of mental health and SUD care providers, such that the majority of U.S. counties do not have the

resources to support pregnant and postpartum individuals with these conditions (Britt et al., 2023; Health

Resources & Services Administration, 2024a). In particular, this workforce shortage plays a significant

role in both the discomfort referring providers feel with screening and diagnosing these disorders

(because of a lack of referral pathways) and the limited access to timely and appropriate care for patients.

Systemic barriers further intersect with individual challenges, SDOH, and inequities to influence maternal

mental health conditions, substance use, and SUDs. Accessing affordable and comprehensive

reproductive care, maternity care, and care for perinatal mental health conditions and SUDs is difficult for

many individuals (Britt et al., 2023; Choi et al., 2022; Salameh et al., 2019). Difficulties accessing care

occur on many levels (e.g., problems with transportation to

appointments or lack of child care preventing attendance at perinatal

care visits). The task force recognizes those individual barriers but

generally refers to problems with access as the larger systemic

issues that make it difficult for individuals to get the right care that

meets their needs at the right time.

Lack of access is primarily driven by a significant shortage in the workforce members, both clinical and

nonclinical, who provide perinatal services—a shortage that causes widespread maternity care deserts.

Access is also affected by other factors, including the need to go to different facilities for various types of

care and a lack of reimbursement for needed services (e.g., patient education and screening). Only 32

percent of substance use treatment facilities accept pregnant women as patients, according to the 2022

National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (Substance Abuse and Mental Health

“Even if we could have swung it

financially, [paying for therapy]

would have felt indulgent.”

- E.L., mother of one

8

Services Administration, 2023c). Additionally, health care and services that are culturally relevant to the

individual may not be available. Existing health care and social service systems serving this population

are highly fragmented and typically do not meet the needs of the whole person or the mother-child dyad.

For example, billing systems typically support reimbursement for services provided to an individual

patient rather than the mother–child dyad. Fragmented and non-holistic systems contribute to missed

opportunities to identify maternal mental health conditions and SUDs, link people with the appropriate

interventions, and provide the necessary continuity of care (Byatt et al., 2015; Green et al., 2024). Based

on the expertise and experience of the task force, complicated insurance systems and processes can be

difficult and stressful to navigate. The cost of care—and the trend of providers of care for mental health

conditions and SUDs not accepting insurance, causing all fees to be out-of-pocket expenses—is a

significant barrier for many.

Acknowledging the Challenges That Providers Face

Frontline providers who care for pregnant and postpartum individuals and their infants face significant

challenges when addressing maternal mental health conditions and SUDs. The task force has found that

although the nation has many providers who are experts in perinatal mental health and SUD care, topics

in perinatal mental health and SUDs are typically not covered well in education and training systems for

obstetric, pediatric, and primary care providers. Similarly, many mental health and SUD care providers

may lack sufficient training in the unique needs and considerations of pregnant and postpartum

individuals (Clarke et al., 2023). Workforce shortages affect both clinical and nonclinical providers, who

are increasingly asked to perform more services in 15- or 30-minute visits. Other provider challenges

include burnout, administrative burden, and billing issues (Herd & Moynihan, 2021). Providers also may

be unaware of (and often don’t have the staffing to help find) community resources to support people

with maternal mental health conditions, SUDs, and various life situations that affect their well-being (e.g.,

SDOH and experiences of trauma, including GBV). Providers may also have concerns about protecting

the safety and confidentiality of patients/clients experiencing IPV.

A Fragmented Health Care System

Task force discussions focused on the considerable fragmentation of the U.S. health care system and its

effects on access to maternal mental health and SUD care. In the experience of the task force, our system

does not address the holistic needs of the mother–child dyad. The major challenges include integrating

services into the workflow and electronic medical records, issues with insurance reimbursement, the

workforce shortage and need for specific training, and the lack of clinical–community partnerships. For

example, bundled payment for perinatal care often does not incorporate services for mental health

conditions and SUDs, and vice versa. Additionally, clinical facilities (including birthing hospitals) often

lack familiarity with community resources that support maternal mental health and new parents.

Moreover, these facilities are not co-located with the support services that new parents often need. In

contrast, co-located or integrated perinatal (or primary) care provided by interdisciplinary teams offers

access to evidence-based services for mental health conditions and SUDs. Integrated care reduces stigma

and reduces the burdens and negative SDOH that many people face—such as lack of access to

transportation and child care and time constraints—when they need to access these services (including

services for IPV). In areas with workforce shortages, co-located and integrated care can reduce the

number of required support staff members. Facilities that offer integrated care might be more likely to use

perinatal psychiatry access programs to address gaps in expertise rather than refusing to treat perinatal

mental health conditions and SUDs. On-site resources (e.g., team members with the time and expertise to

talk with patients about complex concerns) and established community partnerships also increase the

ability of busy providers to support people who are experiencing IPV, other GBV-related trauma, and/or

negative SDOH. Telehealth collaborations could represent another pathway to better care coordination.

9

Lack of Systemic Supports During Postpartum Challenges

Pregnancy and the postpartum period represent major life course events. The physical, mental, emotional,

and practical challenges—including sleep deprivation, costs associated with medical care and caring for a

newborn, and around-the-clock caregiving on top of other responsibilities—of caring for an infant are

considerable. Our nation lacks the federal- and state-level infrastructure needed to fully support these

major life events. Such infrastructure would include guaranteed paid family and medical leave, universal

child care, full support for parents and infants getting proper nutrition, and equitable, full access to

culturally relevant, trauma-informed medical and mental health care services. Systemic issues—including

mostly separated medical and mental health systems, complicated insurance processes, a lack of

workforce members to address perinatal mental health conditions and SUDs, a lack of knowledge about

support resources, and mandatory reporting and other punitive measures—also present challenges during

the postpartum period. Moreover, the federal government lacks the infrastructure to lead efforts to address

these systemic issues.

The lack of paid family and medical leave remains a primary concern, as well as access to affordable

healthful foods for parents and infants in all communities. Current social safety net programs (e.g., the

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children [WIC

]; the Children’s Health

Insurance Program [CHIP]; Temporary Assistance for Needy Families [TANF]; and the Supplemental

Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP]) and housing assistance significantly mitigate the impact of

poverty and food insecurity; however, given their limitations or requirements—such as insufficient

coverage for those in deep poverty, income limits/requirements, stringent work requirements, difficult

application processes, program implementation challenges, and time limitations on services—these

support programs do not sufficiently address these social problems (Marti-Castanar et al., 2022; Shaefer

et al., 2020; Giannarelli et al., 2017; Danziger, 2010 as cited in Marti-Castanar et al., 2022).

In fact, the United States is one of the few high-income nations that does not yet provide paid family and

medical leave (Livingston & Thomas, 2019). Paid family and medical leave policies allow workers to

receive compensation when taking longer periods of time away from work for qualifying reasons (e.g.,

having a new child, being ill, or having a family member who is ill) (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.).

Currently, no federal law influences these policies for the U.S. private sector. A growing number of states

have established their own policies. Paid family and medical leave policies are important because they

permit workers to engage in employment and other economic activities rather than exit the workforce to

care for loved ones (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.). Although the

Family and Medical Leave Act of

1993 is available, researchers have pointed out that the

law’s requirements for a minimum number of hours

worked, duration of employment, and employer size

generate inequities (Heymann et al., 2021). Some

researchers have argued that policies for national paid leave

(such as paid sick leave) could help reduce health and

socioeconomic inequities (Heymann & Sprague, 2021).

On the whole, our nation’s fragmented infrastructure and limited resources often put the burden of

managing all the challenges of the perinatal period on individuals and families, which strains parental

mental health and well-being. Moreover, some individuals have limited or no support systems to help

with the practical and emotional aspects of pregnancy and the postpartum period. People who lack in-

person and day-to-day support and resources during the initial months after delivery face many challenges

that may affect their mental health. They, in particular, would benefit from a care system that assesses the

level of support that individuals have and bolsters assistance. It is also critical that infrastructure and

systems be tailored to address the unique considerations faced by pregnant and postpartum adolescents

who have little or no support, as their needs will differ from those of adults.

“With my second [child] … I would have

done better if I had taken more time to

properly heal. [That would have been

better for] both … me and [my] baby.”

- C.S., pregnant mother of two

10

As the United States does not have a federal paid family and

medical leave policy, many people must return to work before

they are ready. This situation is compounded by a shortage of

affordable high-quality child care and may negatively affect

maternal mental health. (See “Pillar 5: Lift Up Lived

Experience”). One issue that arises during the postpartum period

as new parents return to work is infant feeding. A postpartum individual’s informed decision of whether

to breastfeed as part of their approach to infant feeding should be supported by their provider and those

they trust. The method of infant feeding is a major consideration for postpartum individuals. Although

there are many clear benefits to both the mother and the baby from breastfeeding—including

breastfeeding’s being associated with improved mental health outcomes—lactation may not always be

easy. Some evidence suggests that people who experience challenges with breastfeeding that do not

match their expectations may be likelier to experience negative mental health outcomes (Yuen et al.,

2022). The necessary supports to start and succeed at breastfeeding (e.g., high-quality breast pumps,

lactation consultants, coaches, and peer support programs) may not be available, covered by insurance, or

affordable. Lack of infrastructure in the workplace (e.g., designated rooms for lactation, refrigerators, and

time accommodation for pumping) may be a barrier. Pressure from others may play into the decision of

whether to breastfeed and its effects on mental health. Maternal conditions, including mental health

diagnoses or SUDs, may require medications, and risks and benefits must be taken into consideration

when choosing optimal infant feeding strategies. Both providers and patients need current, evidence-

based information so they can engage in shared decision-making about the risks and benefits of

breastfeeding for their individual situation and also about continuation of medications during pregnancy

and in the postpartum period. Mental health repercussions should be routinely recognized and addressed.

The Perinatal Period: An Opportunity to Address Mental Health

Conditions and SUDs

The perinatal period offers a unique opportunity to engage pregnant and postpartum individuals in

discussions about mental health and substance use and to intervene with those who have mental health

conditions and SUDs. It also provides opportunities to address issues that affect maternal mental health

and well-being, such as negative SDOH and experiences of GBV and other trauma. Generally, pregnant

and postpartum individuals are actively engaged in the health care

system. A person with an uncomplicated pregnancy has an average

of 25 interactions with health care providers during the perinatal

period. But some experiences, such as NICU hospitalization of the

infant or prolonged hospitalization of the mother, may disrupt

screening opportunities for perinatal mental health conditions and

SUDs. System supports could help ensure that opportunities for

detecting these conditions are not missed. Additionally, pregnant

and postpartum individuals often interact with nonmedical community-based providers—such as doulas,

childbirth educators, lactation consultants, home visitors, and community health workers. These

nonmedical community-based providers often have strong and trusted relationships with their clients and

are well situated to provide education about maternal mental health conditions, SUDs, and other issues, as

well as sharing resources. The perinatal period also offers a unique opportunity to have a two-generation

approach by addressing these issues that, if left untreated, can have long-term negative effects on the life

course of the parent and the life course of the child.

“I felt like I had to do it all, like

Superwoman. I didn’t disclose

that I was sad or crying.”

- J.S., mother of one

“Being asked about my mental

health made me feel that

mental health and emotions

were a legitimate concern.”

- S.B., mother of two

11

Introduction

Congress’s authorization of the task force’s meeting and reporting requirements aims to address the crisis

of maternal mental health by calling for greater collaboration within the federal government, emphasizing

best practices related to maternal mental health conditions and substance use disorders (SUDs), and

requiring the Task Force on Maternal Mental Health to develop a national strategy to serve as a blueprint

for improving maternal mental health and SUD care. Congressional action was prompted by the

individual and societal consequences of these conditions when left untreated, as well as advocacy efforts.

HHS formed the Task Force on Maternal Mental Health as a subcommittee of SAMHSA’s ACWS in

response to a directive from Congress to address this public health crisis (

Consolidated Appropriations

Act, 2023 [Public Law 117–328, Section 1113]). The members of the task force developed the

recommendations in this national strategy based on their collective expertise and discussions, review of

the relevant literature, listening sessions with state- and local-level stakeholders, and public comments.

The task force also considered input from people who have direct knowledge and experience of these

conditions (including providers). (See “Pillar 5: Lift Up Lived Experience.”) Given the urgency of the

maternal mental health crisis, the publication of this document and the complementary Task Force on

Maternal Mental Health’s Report to Congress was expedited to accelerate implementation of the task

force’s recommendations. The report to Congress details the committee’s methods.

The task force is a subcommittee of SAMHSA’s ACWS and falls under the Federal Advisory Committee

Act (FACA). The lead agencies are the HHS Office of the Assistance Secretary for Health’s (OASH)

Office on Women’s Health (OWH) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

(SAMHSA).

12

At a Glance: Task Force Members and Methods

Task Force Members

• Experts in obstetrics and gynecology, maternal and child health, clinical and research psychology,

psychiatry, counseling, gender-based violence (GBV), strategic policy, community behavioral

health, federal–community partnerships, and other relevant areas

• More than 100 members from diverse backgrounds

• Both federal and nonfederal members

• Federal members leading departments and agencies (or the designees of leaders) with purviews

that include maternal and child health and health care, services for mental health conditions and

SUDs, and surveillance efforts and data collection

• Nonfederal members with expertise in maternal mental health, recruited through multiple notices

in the Federal Register, including advocates, representatives from nonprofit entities,

representatives from policy centers, providers, representatives from medical and professional

societies, industry representatives, and those with lived experience

• Individuals with lived experience of maternal mental health conditions and SUDs (including as

providers of care)

Task Force Methods

• The task force consulted federal and national program reviews, consulted a literature review, held

four 1-hour virtual listening sessions for state- and local-level input from representatives of key

national groups of stakeholders, obtained public comments through a request for information

(RFI), and consulted the report titled Maternal Mental Health: Lived Experience, completed by the

U.S. Digital Service (USDS).

• Five task force workgroups met virtually about 40 times (1–2 hours each time) between November

2023 and April 2024 to generate the findings and write recommendations for this national strategy.

• There were 10 workgroup co-chair check-in meetings between November 2023 and April 2024.

• There were five meetings of the entire task force and two meetings of federal task force members

to refine drafts of the national strategy in March and April 2024.

• There were two meetings with the ACWS to approve the national strategy and its

recommendations (the first meeting was for approval in principle, and the second meeting was for

approval of the final language) in April 2024.

• There is ongoing work to update and supplement the report to Congress and national strategy

regularly, with a sunset date of September 30, 2027.

Participating Federal Agencies

• Administration for Children and Families (ACF)

• Administration for Community Living (ACL)

• Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

• Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

• Center for Faith-based and Neighborhood Partnerships (Partnership Center)

• Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)

• Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

• Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)

• HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH)

• HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE)

• HHS Office of Intergovernmental and External Affairs (IEA)

• Indian Health Service (IHS)

• National Institutes of Health (NIH)

• Office of Management and Budget (OMB)

13

At a Glance: Task Force Members and Methods

• Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

• U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS)

• U.S. Department of Defense (DOD)

• U.S. Department of Labor (DOL)

• U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)

• U.S. Digital Service (USDS)

The Task Force on Maternal Mental Health’s national strategy and report to Congress are an important

part of broader federal efforts to address women’s overall health (including their mental health) and

maternal health in particular across the nation. The task force’s documents are aligned with multiple

ongoing initiatives, including the following:

• The White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research

;

• White House Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health Crisis;

o The task force notes that the White House Blueprint for Addressing the Maternal Health

Crisis makes recommendations that address maternal mental health, including:

improving data collection

focusing on veterans

expanding the National Maternal Mental Health Hotline

integrating supports for mental health conditions and SUDs in community

settings

o To accompany the blueprint,

Substance Use Disorder in Pregnancy: Improving

Outcomes for Families was developed by the Office of National Drug Control Policy

with input from other federal agencies, including SAMHSA.

• The HHS Secretary’s Postpartum Maternal Health Collaborative with six states (Iowa,

Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, and New Mexico);

• The Hear Her (with resources for American Indian/Alaska Native individuals) campaign (CDC);

• The Maternity Care Action Plan (CMS);

• The Transforming Maternal Health Model (CMS);

• The Enhancing Maternal Health Initiative (HRSA);

• The National Maternal Mental Health Hotline (HRSA);

• The Talking Postpartum Depression campaign (OWH); and

• The State Technical Assistance Maternal Mental Health Learning Communities (SAMHSA).

Coordination among federal agencies, along with collaboration with the federal government’s many

partners, is essential to maximize the impact of these efforts. With the release of this national strategy, the

Task Force on Maternal Mental Health indicates a path forward for the whole federal government to

coordinate its many ongoing activities, initiatives, and programs with the goal of addressing the barriers

discussed. Individual federal agencies provided information on federal programs discussed for the

recommendations, and some of the text quotes or paraphrases their websites and agencies’ other

publications and materials. The federal government’s work must include ongoing partnerships with states,

U.S. territories, local jurisdictions, and tribes. Although the report to Congress and this national strategy

discuss recommendations and potential partnerships with states, the task force will also develop a report

to all governors in the U.S. that details further opportunities for local- and state-level partnerships and

recommendations specific to states. Federal government collaborations also must include public–private

entities, industry, advocates, medical and professional societies, communities, and individuals with lived

experience and their families. Throughout this national strategy, there is a focus on leveraging and

expanding federal programs, resources, and expertise—as well as evidence-based practices.

14

Implementation of the national strategy will provide a blueprint for building the necessary infrastructure

to support the mental health and well-being of all pregnant and postpartum individuals, their children,

their families, and communities across the nation.

The Audience, Scope, and Vision for the National Strategy

Audience

The primary target audience for this national strategy is the federal government—namely, Congress and

the executive branch, including the many federal departments and agencies that spearhead the provision

of health care and services in communities. Note that at times the recommendations specify a particular

entity within the federal government and that at other times no particular agency or entity is specified

because it is implied that a whole-government approach is needed.

However, the federal government’s work cannot be carried out without collaborations and partnerships

with states, public–private entities, industry, advocates, medical and professional societies, communities,

and individuals with lived experience and their families. Therefore, this national strategy also speaks to

those collaborators and partners and identifies opportunities for them to come together to change the

national landscape of perinatal mental health and substance use care.

Scope

Congress charged the task force with lifting up best practices and improving federal coordination to

address perinatal mental health, substance use, and their co-occurrence (Consolidated Appropriations Act,

2023). Per the authorizing legislation, the scope of the national strategy is to describe how the Task Force

on Maternal Mental Health (as well as those federal departments and agencies represented on the task

force) “may improve coordination with respect to addressing maternal mental health conditions, including

by:

• Increasing the prevention, screening, diagnosis, intervention, treatment, and access to maternal

mental health care, including clinical care and non-clinical care—such as those provided by peer-

support and community health workers, through the public and private sectors;

• Providing support relating to the prevention, screening, diagnosis, intervention, and treatment of

perinatal mental health conditions, including families, as appropriate;

• Reducing racial, ethnic, geographic, and other health disparities related to prevention, diagnosis,

intervention, treatment, and access to maternal mental health care;

• Identifying opportunities to modify, strengthen, and better coordinate existing federal infant and

maternal health programs to improve perinatal mental health and SUD screening, diagnosis,

research, prevention, identification, intervention, and treatment with respect to maternal mental

health; and

• Improving planning, coordination, and collaboration across Federal departments, agencies,

offices, and programs.”

The task force highlights the following cross-cutting imperatives throughout this national strategy:

• The need to improve equity and access to perinatal care and services by directing resources to

the individuals, families, and communities that disproportionately experience these maternal

mental health conditions, substance use, and SUDs;

• The important role of federal coordination in building an infrastructure and an environment that

support maternal mental health and families;

• The essential contribution of culturally relevant support and care provided by workforce

members who understand the role of perspectives of mothers from under-resourced communities

in bolstering maternal mental health; and

• The need for trauma-informed approaches to care and services and the importance of training

and education in this area among providers, programs, and organizations.

15

Vision

The task force expects that its work—this national strategy, the report to Congress, and subsequent

reports and updates—will improve maternal mental health and well-being for all individuals and

communities across the nation. The task force envisions that perinatal mental health and substance

use care in our nation will be seamless and integrated across medical, community, and social

systems, such that there will no longer be a distinction between physical and mental health care and

that models of care and support will be innovative and sensitive to individuals’ experiences, culture,

and community.

Call to Action

The task force summarizes the current national landscape for maternal mental health conditions and

SUDs:

• There is a high prevalence of pregnancy-related deaths, and maternal mental health conditions

and SUDs are significant contributors to that.

• Disparities disproportionately affect individuals at higher risk for perinatal mental health

conditions and SUDs.

• GBV and social determinants of health (SDOH) are contributing factors.

• There is a lack of cohesive policies, programs, and systems; and

• There have been many missed opportunities to engage pregnant and postpartum individuals.

Given this landscape, the task force calls for the following in order to achieve the aforementioned vision:

• Regular and respectful education about, discussion of, and screening for maternal mental health

conditions and SUDs (along with consideration of SDOH and GBV) for all individuals during the

perinatal period;

• Clear pathways to connect individuals affected by maternal mental health conditions and SUDs

with care that is holistic, equitable, affordable, trauma-informed, patient-centered, and culturally

and linguistically relevant; and

• Adequately staffed care that focuses on the mother–infant dyad with two-generational approaches

and ensures that the right treatment is available at the right time.

As described in the report to Congress, federal programs, as well as and state and local efforts, are

ongoing to realize this vision. These efforts employ evidence-based, evidence-informed, and promising

practices (see definitions in “Language Used in This National Strategy”), many of which are also detailed

in the report to Congress. Throughout this national strategy, the task force highlights some federal

programs, state and local efforts, models, and best practices—suggesting ways that federal coordination

could scale up these effective measures. The task force also outlines what the federal government could

do—in collaboration with its diverse array of public and private partners—to promote maternal mental

health and prevent SUDs for all pregnant and postpartum individuals.

Some of the recommendations described in this national strategy are actionable in the short term, whereas

others represent aspirational goals to work toward over many years. The national strategy is framed

around five pillars, each of which is supported by priorities and recommendations to improve care and

services for maternal mental health conditions and SUDs. The voices of people with lived experience are

uplifted throughout this national strategy, including in quotations from Maternal Mental Health: Lived

Experience. The Task Force on Maternal Mental Health will regularly update the national strategy—a

living document that will inform Congress of the federal government’s efforts and describe the current

status of this crucial area of public health in the United States.

16

Recommendations from the Task Force on

Maternal Mental Health

As a subcommittee of the ACWS, the Task Force on Maternal Mental Health developed

recommendations to coordinate and improve federal activities related to addressing maternal mental

health conditions and SUDs. Its parent FACA committee approved all of the recommendations, which are

presented within the framework of five pillars (with priorities under each). The recommendations do not

necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or positions of any of the participating departments or agencies.

The organizational framework for the recommendations is shown in the figure below. Although the

background section of this national strategy provides the overarching reasons for the recommendations as

a whole, each recommendation is supported by a brief rationale (“Why?”) and suggested federal

government implementation activities (“How?”). The activities are broad and ambitious and will depend

on federal collaboration with multiple partners—including state, local, tribal, and territorial governments;

industry; professional and scientific associations; community-based organizations; and communities

across the country—to change the national landscape of perinatal mental health and substance use care

and ultimately improve the lives of people with these conditions.

Pillar 1: Build a National Infrastructure That Prioritizes Perinatal

Mental Health and Well-Being

Our nation currently lacks the infrastructure and environment to sufficiently support maternal mental

health and well-being. There is a lack of federal laws and policy to support parental leave and child care;

activities at the federal level require better coordination; systems of care are often fragmented and do not

meet the needs of the mother–infant dyad; and some policies are stigmatizing and punitive, especially

17

around maternal substance use disorders (SUDs). Recommendations supporting Pillar 1 include

establishing relevant federal laws, policies, programs, and mechanisms to prioritize and destigmatize

perinatal mental health and SUD care; improving disparities; integrating physical and mental health care;

and implementing universal education, prevention, screening, treatment, and recovery support for

maternal mental health conditions and SUDs.

Priority 1.1: Establish and Enhance Federal Policies That Promote Integrated

Perinatal and Mental Health/SUD Care Models with Holistic Support for Mother–Infant

Dyads and Families from Multidisciplinary and Interdisciplinary Teams

Recommendation 1.1.1

Enact federal laws and align incentives for states, the District of Columbia (D.C.), and territories to

mirror the expansion, funding, and enhancement of federal- and state-level integrated perinatal

and mental health/SUD care models involving multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary teams that

extend from pregnancy through at least 1 year postpartum—including two-generation (maternal

and pediatric care) practices, evidence-based screening and prevention, provision of treatment, and

linkages to follow-up and support services.

Why?

In integrated health care, teams of multidisciplinary health professionals collaborate to provide patient

care. This approach features a high degree of collaboration and communication among members of the

health care team. All health professionals on the team share patient care information so an individualized

comprehensive treatment plan can be developed (American Psychological Association, 2013). In the

experience of the task force, integrated perinatal care is holistic and considers the effects of life situations

(e.g., social determinants of health [SDOH] and intimate partner violence [IPV]) on health and the ability

to engage in care. Integrated care models do not separate physical and mental health, and they focus on

health promotion and prevention rather than treatment. This recommendation also builds on a strategic

priority outlined in the

HHS Roadmap for Behavioral Health Integration.

In the experience of the task force, integrated care models facilitate universal screening of perinatal health

conditions and SUDs—a practice that reduces stigma and offers opportunities to provide patient

education and resources (e.g., brochures, videos, mobile apps, and websites). Existing evidence-based

integrated care models are effective and could be enhanced and expanded, with the potential for a

significant increase in positive outcomes. For example, Seattle and King County’s public health system’s

implementation of MOMCare for pregnant women with major depressive disorder or dysthymia led to a

reduction in depression severity. This program—which was found to be cost-effective—improved rates of

adherence to care and depression remission (Grote et al., 2015). As described in the task force’s report to

Congress, federal programs that offer integrated care include the Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) Model

and Perinatal Reproductive Education Planning and Resources (PREPARe).

Research supports extending coverage for pregnancy care for up to 1 year postpartum. Among pregnancy-

related deaths from suicide, drug overdoses, and other causes associated with mental health conditions

and SUDs analyzed between 2008 and 2017, nearly two-thirds (63 percent) occurred 43–365 days

postpartum (compared with 18 percent of deaths from other causes) (Trost et al., 2021). Among women

who reported postpartum depressive symptoms at 9 to 10 months, 57.4 percent did not report these

experiences at 2 to 6 months—a finding that underscores the importance of attending to maternal mental

health throughout the year after giving birth (Robbins et al., 2023). Extending pregnancy coverage

ensures continuity of care, warm handoffs, and referrals and linkages to primary care or mental health

support systems.

18

How?

• This recommendation calls for the integration of mental health care and substance use care across

all relevant perinatal settings, such as obstetricians’ offices, primary care offices, pediatric

outpatient settings, emergency rooms, inpatient settings (including medical units), labor and

delivery settings, postpartum units, and neonatal intensive care units (NICUs).

• Services embedded in these integrated care models should include evidence-based screening,

prevention, assessment, treatment, referral, and follow-up services; evidence-based dyadic

(parent–child) treatment services to address both the parental mental health conditions and SUDs

and associated early childhood mental health concerns when they are present; nonclinical support

personnel—such as community health workers, doulas, and peer support specialists—to facilitate

culturally responsive linkages to services in the community and assist with screening and

providing resources to address SDOH; guidance on how atypical locations for care and services

(such as jails, prisons, and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and

Children [WIC] offices) can integrate mental health and SUD treatment into their service

provision; screening, patient education, and services for gender-based violence [GBV] and other

trauma; and coordination with community-based organizations to provide at least 1 year of

follow-up support in the community.

• All components of the integrated care models should be embedded in a practice’s electronic

health records or equivalent documentation systems and be accounted for when billing.

• There should be incentives established and support provided to states for offering increased

reimbursement for screening and treatment services related to perinatal mental health and

substance use conditions (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, n.d.).

• Established guidelines on integration—such as those in the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Guide for Integrating Mental Health Care into Obstetric Practice,

the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Guide for Integration of Perinatal Mental Health in

Maternal and Child Health Services, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s

(AHRQ) information on behavioral health integration for pregnant and postpartum women—

should be followed.

• Federal policies and incentives should be established and expanded to encourage all states to

promote and sustain permanency of pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage.

• Congress and the executive branch should enact laws that do the following:

o Require (versus only offer an option to) all states, all territories, and D.C. to expand

Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) coverage from 60 days to 1

year after pregnancy, as well as providing information on how to use these benefits to

providers, patients, and communities (MOMMIES Act, 2023).

o Require all states, D.C., and all territories to provide Medicaid coverage of nonclinical

support staff members, such as community health workers, doulas, health navigators,

peer support specialists, lactation consultants, and GBV counselors/specialists.

o Require all states, D.C., and all territories to provide Medicaid coverage for dyadic

family mental health and SUD services. Ensure that providers can bill for services

provided to both the mother and the baby during the same visit (i.e., not having just one

of them be the identified patient).

• There should be incentives and support for states and private payers to implement the same

coverage as outlined above.

• In the absence of federal law, federal agencies should encourage more states to opt in to Medicaid

benefits for services provided by nonclinical support personnel, such as community health

workers, doulas, and peer support specialists. As of July 1, 2022, 29 states that had responded to

KFF’s 22nd annual Medicaid Budget Survey reported allowing Medicaid payment for the

services of community health workers (Haldar & Hinton, 2023).

19

• Models that have worked, including the following, should be funded, scaled up, and

disseminated:

o The Integrated Maternal Health Services (IMHS) program fosters the development and

demonstration of integrated maternal health service models, such as the Maternity

Medical Home, with a focus on advancing equity and supporting comprehensive care for

pregnant and postpartum people from under-resourced communities.

o The AIMS Center at the University of Washington offers a comprehensive

implementation guide for the Collaborative Care Model, which is an evidence-based

model demonstrating positive outcomes in the primary care setting (Melek et al., 2018)

and has also been shown to reduce racial disparities in care (American Psychiatric

Association Committee on Integrated Care, n.d.). The behavioral care manager serves as

the linchpin of the Collaborative Care Model. Care managers (often clinical social

workers, psychologists, or nurses by training) act as the primary point of contact for both

patients and obstetricians.

o The Integrated Behavioral Health Academy at Denver Health uses existing mental health

and substance use treatment systems and staffing to create a universal screen-to-treat

process for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in obstetric clinics (Lomonaco-Haycraft

et al., 2019).

o The New Jersey Birth Equity Funders Alliance has an effective model for providing

grants to community-based organizations that focus on reducing disparities.

• Training should be incorporated into federal technical assistance programs, and training programs

that have been effective should be disseminated (e.g., the training programs for integrated care

managers identified by Miller and colleagues [2020]).

• Maternity care centers (MCCs) could be created to address the problems of having a limited

workforce and maternity care deserts and provide integrated care (modeled on certified

community behavioral health clinics [CCBHCs] and federally qualified health centers [FQHCs]),