COMMUNITY-BASED

PARTICIPATORY

RESEARCH

FOR HEALTH

COMMUNITY-BASED

PARTICIPATORY

RESEARCH

FOR HEALTH

Advancing Social and

Health Equity

third edition

NINA WALLERSTEIN

BONNIE DURAN

JOHN G. OETZEL

MEREDITH MINKLER

Editors

Copyright © 2018 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-Bass

A Wiley Brand

One Montgomery Street, Suite 1000, San Francisco, CA 94104-4594—www.josseybass.com

Edition History

John Wiley and Sons, Inc. (2e, 2008; 1e, 2003)

The right of Nina Wallerstein, Bonnie Duran, John Oetzel, and Meredith Minkler to be identied as the authors of the editorial

material in this work has been asserted in accordance with law.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section107 or 108 of the 1976 United

States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the

appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400,

fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the

Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or

online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book,

they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and

specically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or tness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created

or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable

for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable

for any loss of prot or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other

damages. Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have

changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care

Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print

versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD

that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more

information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wallerstein, Nina, 1953- editor.

Title: Community-based participatory research for health: advancing social

and health equity / edited by Nina Wallerstein, Dr.P.H, Professor of

Public Health, College of Population Health Director, Center for

Participatory Research, University of New Mexico (UNM), Bonnie Duran,

Dr.P.H., Associate Professor, University of Washington School of Social Work,

Director of the Center for Indigenous Health Research, Indigenous Wellness

Research Institute, John G. Oetzel, Professor, Waikato Management School,

University of Waikato, Meredith Minkler, Dr.P.H., MPH, Professor, Graduate

School, Community Health Sciences, University of California, Berkeley,

Professor Emerita, School of Public Health.

Description: Third edition. | Hoboken, NJ : Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer Imprints,

Wiley, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references. |

Identiers: LCCN 2017018499 (print) | LCCN 2017021064 (ebook) | ISBN

9781119258865 (epdf) | ISBN 9781119258872 (epub) | ISBN 9781119258858

(paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Public health—Research—Citizen participation. | Public

health—Research—Methodology. | Community health services. | BISAC:

MEDICAL / Public Health.

Classication: LCC RA440.85 (ebook) | LCC RA440.85 .C65 2017 (print) | DDC

362.1072—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017018499

Cover design: Wiley

Cover image: © MAGNIFIER/Shutterstock

Printed in the United States of America

PB Printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

From Nina: To my late parents, Robert and Judith Wallerstein,

who modeled for me values of justice and compassion.

From Bonnie: Gratitude to my parents, siblings, and community

members for sharing their values, wisdom, and patience.

From John: To my children, Spencer and Ethan, who inspire me

to make a positive contribution in the community.

From Meredith: To Roy and Fran Minkler, who as parents and

human beings taught by example the power of deep concern

with fairness, caring, keeping a sense of humor,

and never giving up.

CONTENTS

The Editors xiii

The Contributors xv

Preface xxxiii

Camara Phyllis Jones

Acknowledgments xxxvii

PART ONE: INTRODUCTION: HISTORY AND PRINCIPLES

ONE: ON COMMUNITY-BASED PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH 3

Nina Wallerstein, Bonnie Duran, John G. Oetzel, and Meredith Minkler

TWO: THEORETICAL, HISTORICAL, AND PRACTICE ROOTS OF CBPR 17

Nina Wallerstein and Bonnie Duran

THREE: CRITICAL ISSUES IN DEVELOPING AND FOLLOWING

CBPR PRINCIPLES 31

Barbara A. Israel, Amy J. Schulz, Edith A. Parker, Adam B. Becker,

Alex J. Allen, III, J. Ricardo Guzman, and Richard Lichtenstein

PART TWO: POWER, TRUST, AND DIALOGUE:

WORKING WITH DIVERSE COMMUNITIES

FOUR: UNDERSTANDING CONTEMPORARY RACISM, POWER,

AND PRIVILEGE AND THEIR IMPACTS ON CBPR 47

Michael Muhammad, Catalina Garzón, Angela Reyes, and

The West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project

FIVE: TRUST DEVELOPMENT IN CBPR PARTNERSHIPS 61

Julie E. Lucero, Kathrine E. Wright, and Abigail Reese

viii Contents

PART THREE: CBPR CONCEPTUAL MODEL: CONTEXT

AND PROMISING RELATIONSHIP PRACTICES

SIX: SOCIO-ECOLOGIC FRAMEWORK FOR CBPR:

DEVELOPMENT AND TESTING OF A MODEL 77

Sarah L. Kastelic, Nina Wallerstein, Bonnie Duran, and John G. Oetzel

SEVEN: YOUTH-LED PARTICIPATORY ACTION RESEARCH (YPAR):

PRINCIPLES APPLIED TO THE US AND DIVERSE GLOBAL SETTINGS 95

Emily J. Ozer and Amber Akemi Piatt

EIGHT: PARTNERSHIP, TRANSPARENCY, AND ACCOUNTABILITY:

CHANGING SYSTEMS TO ENHANCE RACIAL EQUITY IN CANCER

CARE AND OUTCOMES 107

Eugenia Eng, Jennifer Schaal, Stephanie Baker, Kristin Black,

Samuel Cykert, Nora Jones, Alexandra Lightfoot, Linda Robertson,

Cleo Samuel, Beth Smith, and Kari Thatcher

NINE: SOUTH VALLEY PARTNERS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE:

A STORY OF ALIGNMENT AND MISALIGNMENT 123

Magdalena Avila, Shannon Sanchez-Youngman, Michael Muhammad,

Lauro Silva, and Paula Domingo de Garcia

PART FOUR: PROMISING PRACTICES: INTERVENTION

DEVELOPMENT AND RESEARCH DESIGN

TEN: CBPR IN HEALTH CARE SETTINGS 141

Margarita Alegría, Chau Trinh-Shevrin, Bowen Chung, Andrea Ault,

Alisa Lincoln, and Kenneth B. Wells

ELEVEN: NATIONAL CENTER FOR DEAF HEALTH RESEARCH:

CBPR WITH DEAF COMMUNITIES 157

Steven Barnett, Jessica Cuculick, Lori Dewindt, Kelly Matthews, and Erika Sutter

TWELVE: CBPR IN ASIAN AMERICAN COMMUNITIES 175

Nadia Islam, Charlotte Yu-Ting Chang, Pam Tau Lee, and Chau Trinh-Shevrin

Contents ix

THIRTEEN: ENGAGED FOR CHANGE: AN INNOVATIVE CBPR

STRATEGY TO INTERVENTION DEVELOPMENT 189

Scott D. Rhodes, Lilli Mann, Florence M. Simán, Jorge Alonzo,

Aaron T. Vissman, Jennifer Nall, and Amanda E. Tanner

PART FIVE: PROMISING PRACTICES: ETHICAL ISSUES

FOURTEEN: CBPR PRINCIPLES AND RESEARCH ETHICS

IN INDIAN COUNTRY 207

Myra Parker

FIFTEEN: DEMOCRATIZING ETHICAL OVERSIGHT

OF RESEARCH THROUGH CBPR 215

Rachel Morello-Frosch, Phil Brown, and Julia Green Brody

SIXTEEN: EVERYDAY CHALLENGES IN THE LIFE CYCLE OF CBPR:

BROADENING OUR BANDWIDTH ON ETHICS 227

Sarah Flicker, Adrian Guta, and Robb Travers

PART SIX: PROMISING PRACTICES

TO OUTCOMES: CBPR CAPACITY AND HEALTH

SEVENTEEN: EVALUATION OF CBPR PARTNERSHIPS AND OUTCOMES:

LESSONS AND TOOLS FROM THE RESEARCH FOR IMPROVED

HEALTH STUDY 237

John G. Oetzel, Bonnie Duran, Andrew Sussman, Cynthia Pearson,

Maya Magarati, Dmitry Khodyakov, and Nina Wallerstein

EIGHTEEN: PARTICIPATORY EVALUATION AS A PROCESS

OF EMPOWERMENT: EXPERIENCES WITH COMMUNITY

HEALTH WORKERS IN THE UNITED STATES AND LATIN AMERICA 251

Noelle Wiggins, Laura Chanchien Parajón, Chris M. Coombe,

Aileen Alfonso Duldulao, Leticia Rodriguez Garcia, and Pei-Ru Wang

NINETEEN: ACADEMIC POSITIONS FOR FACULTY OF COLOR:

COMBINING LIFE CALLING, COMMUNITY SERVICE, AND RESEARCH 265

Lorenda Belone, Derek M. Grifth, and Barbara Baquero

x Contents

PART SEVEN: PROMISING PRACTICES TO OUTCOMES:

HEALTHY PUBLIC POLICY

TWENTY: COMMUNITY-BASED PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH

FOR HEALTH EQUITY POLICY MAKING 277

Lisa Cacari-Stone, Meredith Minkler, Nicholas Freudenberg,

and Makani N. Themba

TWENTY ONE: IMPROVING FOOD SECURITY AND TOBACCO

CONTROL THROUGH POLICY-FOCUSED CBPR: A CASE STUDY OF

HEALTHY RETAIL IN SAN FRANCISCO 293

Meredith Minkler, Jennifer Falbe, Susana Hennessey Lavery,

Jessica Estrada, and Ryan Thayer

TWENTY TWO: CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM THROUGH

PARTICIPATORY ACTION RESEARCH 305

Saneta deVuono-Powell, Meredith Minkler, Evan Bissell, Tamisha Walker,

LaVern Vaughn, Eli Moore, and The Morris Justice Project

TWENTY THREE: GLOBAL HEALTH POLICY: SLUM SETTLEMENT

MAPPING IN NAIROBI AND RIO DE JANEIRO 321

Jason Corburn, Ives Rocha, Alexei Dunaway, and Jack Makau

APPENDIX 1: CHALLENGING OURSELVES: CRITICAL

SELF-REFLECTION ON POWER AND PRIVILEGE 337

Cheryl Hyde

APPENDIX 2: GUIDING CBPR PRINCIPLES: FOSTERING

EQUITABLE HEALTH CARE FOR LGBTQ+ PEOPLE 345

Miria Kano, Kelley P. Sawyer, and Cathleen E. Willging

APPENDIX 3: QUALITY CRITERIA OF THE INTERNATIONAL

COLLABORATION FOR PARTICIPATORY HEALTH RESEARCH (ICPHR) 351

Michael T. Wright

Contents xi

APPENDIX 4: CULTURAL HUMILITY: REFLECTIONS

AND RELEVANCE FOR CBPR 357

Vivian Chávez

APPENDIX 5: FUNDING IN CBPR IN US GOVERNMENT

AND PHILANTHROPY 363

Laura C. Leviton and Lawrence W. Green

APPENDIX 6: REALIST EVALUATION AND REVIEW FOR

COMMUNITY-BASED PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH: WHAT WORKS,

FOR WHOM, UNDER WHAT CIRCUMSTANCES, AND HOW? 369

Justin Jagosh

APPENDIX 7: PARTNERSHIP RIVER OF LIFE: CREATING

A HISTORICAL TIME LINE 375

Shannon Sanchez-Youngman and Nina Wallerstein

APPENDIX 8: PURPOSING A COMMUNITY-GROUNDED RESEARCH

ETHICS TRAINING INITIATIVE 379

Cynthia Pearson and Victoria Sánchez

APPENDIX 9: PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENTS: A PRACTICAL

GUIDE TO DEVELOPING DATA SHARING, OWNERSHIP,

AND PUBLISHING AGREEMENTS 385

Patricia Rodríguez Espinosa and Al Richmond

APPENDIX 10: INSTRUMENTS AND MEASURES

FOR EVALUATING COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

AND PARTNERSHIPS 393

Nina Wallerstein

APPENDIX 11: PARTICIPATORY MONITORING AND EVALUATION

OF COMMUNITY HEALTH INITIATIVES USING

THE COMMUNITY CHECK BOX EVALUATION SYSTEM 399

Stephen Fawcett, Jerry Schultz, Vicki Collie-Akers, Christina Holt,

Jomella Watson-Thompson, and Vincent Francisco

xii Contents

APPENDIX 12: POWER MAPPING: A USEFUL TOOL FOR

UNDERSTANDING THE POLICY ENVIRONMENT AND ITS

APPLICATION TO A LOCAL SODA TAX INITIATIVE 405

Jennifer Falbe, Meredith Minkler, Robin Dean, and Jana Cordeiero

APPENDIX 13: CBPR INTERACTIVE ROLE-PLAYS: THREE SCENARIOS 411

Michele Polacsek and Gail Dana-Sacco

AFTERWORD 417

Budd Hall and Rajesh Tandon

INDEX 419

NINA WALLERSTEIN, DrPH, professor of public health, College of Population Health, and

director, Center for Participatory Research (cpr.unm.edu), University of New Mexico (UNM),

has been developing CBPR and empowerment, Paulo Freire–based interventions for more

thanthirty years. She has written over 150 articles and chapters and seven books, including the

Freirean Problem-Posing at Work: A Popular Educator’s Guide. In 2016, she received the inau-

gural Community Engaged Research Lecture award from UNM. She’s had a long-term CBPR

research relationship with several New Mexican tribes to support intergenerational culture-

centered family prevention programming with children, parents, and elders; and she has worked

with the Healthy Native Community Partnership for more than ten years. Since 2006, she has

worked to strengthen the science of CBPR and community-engaged research. She is currently

principal investigator (PI) of Engage for Equity, an NINR-funded RO1 to assess promising

partnering practices associated with outcomes and to develop partnership evaluation and reec-

tion tools and resources. She has collaboratively produced with Latin American colleagues an

empowerment, participatory research, and health promotion curriculum available in Spanish,

Portuguese, and English (http://cpr.unm.edu/curricula-classes/empowerment-curriculum.html)

and cosponsors an annual summer institute in CBPR for health at the University of New Mexico.

BONNIE DURAN, DrPH (mixed-race Opelousas and Coushatta) is professor in the department

of health services, University of Washington School of Public Health and is also Director of the

Center for Indigenous Health Research at the Indigenous Wellness Research Institute (www.

iwri.org). Using Indigenous theories to guide her work, Bonnie’s research includes intervention

and prevalence studies of substance abuse and other mental disorders, violence, and treatment

seeking in Native communities. Her overall aims are to work with communities to design inter-

ventions and descriptive studies that are empowering, culture-centered, sustainable, and that

have maximum public health impact.

JOHN G. OETZEL is a professor in the Waikato Management School at the University of

Waikato. He uses CBPR to collaboratively work with communities to address various health

issues to improve health equity. His current work includes the collaborative development of

interventions with two Māori health organizations in New Zealand related to pre-diabetes and

positive aging. He is also a member of the Engage for Equity research team investigating prom-

ising practices for CBPR in the United States. He contributes expertise in research design and

evaluation and believes in the importance of collaborative design to ensure that the research

evaluation ts the context and needs of communities as well as to ensure interventions are

culturally centered. He is author or coauthor of three books: Managing Intercultural Commu-

nication Effectively (with Stella Ting-Toomey, 2001, Sage); Intercultural Communication: A

Layered Approach (2009, Pearson); and Theories of Human Communication, 11th ed. (with Ste-

phen Littlejohn and Karen Foss, 2017, Waveland). He is coeditor of two other books: The Sage

THE EDITORS

xiv The Editors

Handbook of Conict Communication (with Stella Ting-Toomey, 2006, Sage, and 2ndedition in

2013). In addition, he is also author of more than ninety articles and book chapters.

MEREDITH MINKLER, DrPH, MPH, is professor in the Graduate School, Community

Health Sciences, University of California, Berkeley, and professor emerita in the School of

Public Health. Founding director of the UC Berkeley Center on Aging, Minkler continues to

work with community and other partners to help develop the evidence base for implementing

healthy public policy in areas including healthy retail in low-income neighborhoods, environ-

mental exposures, immigrant worker health and safety, criminal justice reform, and HIV/AIDS.

A recent Fulbright specialist in South Africa in CBPR, she has offered trainings on community-

engaged research in Hong Kong, Singapore, Australia, the United Kingdom, and in numerous

states and provinces in the United States and Canada. Minkler has coauthored close to two

hundred articles and coauthored or edited nine books, including Community Organizing and

Community Building for Health and Welfare (Rutgers, 2012).

THE CONTRIBUTORS

MARGARITA ALEGRÍA, PhD, is the chief of the Disparities Research Unit at Massachusetts

General Hospital and professor in the Departments of Medicine and Psychiatry at Harvard

Medical School. Alegría has served as PI on more than fteen federally funded research

grants and has published more than two hundred professional publications on topics such as

the improvement of health care services delivery for diverse racial and ethnic populations,

conceptual and methodological issues with multicultural populations, and ways to bring the

community’s perspective into the design and implementation of health services.

ALEX J. ALLEN, III, MSA, is the president and CEO of the Chandler Park Conservancy. He

collaborates with residents, stakeholders, local institutions, business, government, and the phil-

anthropic community to transform Chandler Park into a campus with exceptional educational,

recreational, and conservation opportunities for youth and families on Detroit’s eastside and

the region. He has effectively led organizations, collaborative initiatives, and has improved the

quality of life for people who live, work, play, and visit communities in the United States. His

experience includes managing grants for compliance and budget integrity, convening stake-

holders for planning and project implementation, supervising and monitoring youth programs,

fund-raising, reporting and evaluation, and CBPR.

JORGE ALONZO, JD, is a research associate at Wake Forest School of Medicine and is part

of a team that specializes in HIV-prevention research using CBPR with immigrant Latinos.

He has been involved in the design, implementation, and evaluation of HIV-prevention inter-

ventions for Latino gay and bisexual men and men who have sex with men (MSM) and Latina

transgender women. He has also been involved in projects exploring the impact of immigration

enforcement on access to and use of public health services among Latinos.

ANDREA AULT, PhD, MPA, is the senior director of the Mental Health Innovation Lab in

the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. She was previously the

associate director of the Health Equity Lab at Cambridge Health Alliance, where her research

focused on racial-ethnic disparities in mental health care, dissemination and implementation

research, and CBPR.

MAGDALENA AVILA, DrPH, MPH, MSW, is associate professor, community health educa-

tion, Department of Health, Exercise and Sports Science, College of Education, University of

New Mexico. She self-identies as an activist scholar in community health and CBPR, in her

partnering with Latino and other Indigenous communities of color, and in her use of a social

justice framework. Her areas of research are environmental health, environmental racism, and

community health impact assessments in working with rural and urban communities, and she

has expanded her research capacity by incorporating digital story making into her CBPR work

with Latino communities.

xvi The Contributors

STEPHANIE BAKER, PhD, MS, PT, is assistant professor of public health at Elon Univer-

sity and a member of the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative. Her work is focused

on social determinants of racial inequities in health, community organizing as a tool for public

health change, antiracism pedagogy, and CBPR.

BARBARA BAQUERO, PhD, MPH, is assistant professor of community and behavioral

health at the University of Iowa, College of Public Health. She is a founding member of the

Healthy Equity Advancement Lab (HEAL), an academic-community research lab dedicated to

advancing health equity through research and training. She serves as PI and deputy director of

the University of Iowa, Prevention Research Center, funded by the CDC.

STEVEN BARNETT, MD, is associate professor of family medicine and public health sci-

ences at the University of Rochester and director of the Rochester Prevention Research Center:

National Center for Deaf Health Research. He is a sign language–skilled family physician

researcher with a career focus on health care and collaborative health research with deaf sign

language users and people with hearing loss, their families, and communities.

ADAM B. BECKER, PhD, MPH, is associate professor of pediatrics and preventive med-

icine in the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University. He is also execu-

tive director of the Consortium to Lower Obesity in Chicago Children (CLOCC) at Ann

and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. He has used CBPR to examine and

address the impact of stressful community conditions on the health of women raising chil-

dren, youth violence prevention, and the impact of the social and physical environment on

physical activity.

LORENDA BELONE, PhD, MPH, (Diné/Navajo) is assistant professor at the University of New

Mexico (UNM) College of Education. She is a senior fellow with the Center for Participatory

Research, a center that supports networks of research with community partners in New Mexico

addressing health inequities, and a senior fellow with the UNM Center for Health Policy. Since

2000, she has been actively engaged in CBPR research that has involved southwest Native

American communities. She currently is co-PI on a NIDA-funded RIO multi-tribal implemen-

tation and evaluation study (1R01DA037174-03).

EVAN BISSELL, MPH, MCP, is an artist based in the Bay Area. He teaches art and social

change at UC Berkeley and is involved in participatory research and art projects in multiple set-

tings across the country that support equitable systems and liberatory processes. His work has

been exhibited in institutions and galleries across the country. He is the creator of knottedline

.com and freedoms-ring.org.

KRISTIN BLACK, PhD, MPH, is a postdoctoral fellow in the Cancer Health Disparities

Training Program in the Department of Health Behavior at the University of North Carolina at

Chapel Hill. Her PhD is in maternal and child health, and her career commitment is to use CBPR

approaches to understand and address race-specic inequities in cancer survivorship and repro-

ductive health.

The Contributors xvii

JULIA GREEN BRODY, PhD, is executive director and senior scientist at Silent Spring

Institute, an independent research group founded in 1994 by breast cancer activists to create a

“lab of their own” focused on environmental factors and prevention. Her research, supported by

the National Institutes of Health, investigates everyday exposures to carcinogens and endocrine-

disrupting chemicals from consumer products, workplaces, and pollution.

PHIL BROWN, PhD, is University Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Health Sciences

at Northeastern, where he directs the Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute.

His books include No Safe Place: Toxic Waste, Leukemia, and Community Action; Toxic Expo-

sures: Contested Illnesses and the Environmental Health Movement; and Contested Illnesses:

Citizens, Science, and Health Social Movements. He directs an NIEHS training program “Trans-

disciplinary Training at the Intersection of Environmental Health and Social Science.”

LISA CACARI-STONE, PhD, MA, MS, is associate professor in the College of Population Health

and assistant director with the RWJF Center for Health Policy at the University of New Mexico.

Her scholarly interests focus on upstream determinants of health, including societal and political

structures and relationships that differentially affect population health and policy interventions

that inuence health equity. Her community-engaged research with Latino and US-Mexico border

communities encompass macro-level determinants (e.g., immigration policy, health reform); the

community level (e.g., impact of neighborhood context and migration on substance use); and the

interpersonal level (e.g., the role of promotores de salud in chronic disease management among

Latinos). Cacari Stone is widely trusted for her work in translating and disseminating data for

policy making with governments, community-based organizations, coalitions, and foundations.

CHARLOTTE YU-TING CHANG, DrPH, MPH, is coordinator of research to practice and

evaluation and associate project scientist at the Labor Occupational Health Program, School

of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley. Her work has focused on advancing the

movement of research into practice in worker health and safety, with a particular interest in the

role and processes of research partnerships with workers and community members. She has

worked and written on a range of projects involving immigrant worker populations and commu-

nities as well as on research to practice lessons learned in construction health and safety.

VIVIAN CHÁVEZ, DrPH, is associate professor of health education at San Francisco State

University. A storyteller by nature, she has collaborated with community-based organiza-

tions to disseminate their work. She coedited Prevention Is Primary: Strategies in Community

Well-Being, coauthored Drop That Knowledge: Youth Radio Stories, translated Media Advocacy

into Spanish, and made a lm about cultural humility that is widely accessible. Her work inte-

grates the language of the arts, culture, and the body for health and social change.

BOWEN CHUNG, MD, MSHS, is associate professor–in-residence of psychiatry at the UCLA

David Geffen School of Medicine, an adjunct scientist at the RAND Corporation, and an

attending physician at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. He has been a PI and co-PI on ten feder-

ally funded research grants and is the author of more than thirty scientic publications. He has

been working with the same community partners for nearly fteen years.

xviii The Contributors

VICKI COLLIE-AKERS, PhD, MPH, is associate director of health promotion research at the

KU Center for Community Health and Development. She serves as an investigator on several

projects promoting health equity and reduction in health disparities in the Kansas City met-

ropolitan area. Additionally, she directs several evaluation projects that support partners who

are working to promote health through their comprehensive initiatives. Her research pri-

marily focuses on applying a CBPR orientation to understand how collaborative partnerships

and coalitions can improve social determinants of health and equity and reduce disparities in

health outcomes.

CHRIS M. COOMBE, PhD, MPH, is assistant research scientist in the Department of Health

Behavior/Health Education at the University of Michigan School of Public Health and is afl-

iated with the Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center. She has extensive expe-

rience designing, implementing, and evaluating collaborative research and interventions using

CBPR. Coombe’s work focuses on understanding how urban social and physical environments

contribute to racial and socioeconomic inequities and translating that knowledge into policy

interventions to promote health and equity.

JASON CORBURN, PhD, MCP, is professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning

and the School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley. He directs the Institute of

Urban and Regional Development and the Center for Global Healthy Cities. He is the author

of a number of award-winning books on community-based action research for health equity,

including Street Science (MIT Press, 2005), Toward the Healthy City (MIT Press, 2009), and

Slum Health (University of California Press, 2016).

JANA CORDEIERO, MPH, is an independent public health and nonprot consultant, strate-

gist, and researcher with more than twenty-ve years of experience working with universities,

foundations, community-based organizations, and health departments to develop and evaluate

effective public health policies and programs. She worked with other advocates in the Bay Area

to successfully pass public health policies to prevent chronic diseases fueled by sugary drinks,

including warning label legislation, sugary drink taxes on distributors, and resisting pouring

rights contracts at universities.

JESSICA CUCULICK, PhD, is associate professor, Department of Liberal Studies, at the

National Technical Institute for the Deaf, Rochester Institute of Technology. Cuculick coor-

dinates the applied liberal arts associate degree program and is the professional development

director for the Rochester bridges to the doctorate program (www.deafscientists.com). She is

codirector for the Deaf Health Lab and the PI for the deaf health literacy research project. Cucu-

lick has been involved with CBPR with the National Center for Deaf Health Research (NCDHR)

at the University of Rochester, such as breastfeeding and cardiovascular health perspectives in

the Deaf community.

SAMUEL CYKERT, MD, is a professor of medicine at UNC-CH in the Division of General

Internal Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology. He also serves as the director of the UNC School

of Medicine program on health and clinical informatics. Combining his research training and

The Contributors xix

interest in health policy, he currently serves as a PI on multiple projects that address health

disparities in cancer treatment and chronic care management.

GAIL DANA-SACCO, PhD, MPH, is on the faculty of the Center for American Indian Health

at the Johns Hopkins University, where she works with tribal communities to research vio-

lence and injury and to develop and implement structural and behavioral strategies to improve

health outcomes.

ROBIN DEAN, MPH, MA, is a public health consultant offering health advocacy and qualitative

research services to clients working to create healthy, connected communities in which

everyone has a voice. In 2014, she advocated through coordinating writers’ media submissions

for soda tax campaigns in San Francisco and Berkeley, and in 2016 she secured endorsements

for Oakland’s and San Francisco’s winning soda tax measures. Robin has produced case studies

and evaluations, including a Berkeley Media Studies Group issue brief on an Oregon affordable

housing coalition’s media advocacy effort and a case study of girls’ education in Mali.

SANETA DEVUONO-POWELL, JD, MCP, is a city planner and attorney who works on

community health. She is currently senior planner at Changelab Solutions and has written

on incarceration and its impacts on families as well as on community-based participatory

action research. Her current work is focused on racial disparities in health and the links

between health disparities and housing.

LORI DEWINDT, MA, is health project coordinator, Rochester Prevention Research Center:

National Center for Deaf Health Research (RPRC/NCDHR), University of Rochester Med-

ical Center. DeWindt has worked in the eld of Deaf community health as a RPRC/NCDHR

research coordinator and as a psychotherapist at the Deaf Wellness Center at the University of

Rochester.

PAULA DOMINGO DE GARCIA is a resident of the South Valley and one of the main pro-

motoras of the S.V.P.E.J. research team. She is an immigrant from the Indigenous community

Nahua de Cuentepec in Temixco, Mexico. Before coming to New Mexico, she worked with the

Independent Commission of Human Rights of Morelos to save her native language, Nahuatl,

and with the National Council to Promote Education in the rural community of Tlatepetl, Tepoz-

tlan. She currently works as a teaching assistant at Dolores Gonzales Elementary School and as

a federal court interpreter translating from Nahuatl to Spanish. She is currently studying for her

AA in Early Childhood Multicultural Education.

AILEEN ALFONSO DULDULAO, PhD, MSW, is the maternal, child, and family health epi-

demiologist for the Multnomah County Health Department in Portland, Oregon. She has held

research fellowships from the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of

Minority Health and Health Disparities, and the University of Washington Institute for Trans-

lational Health Sciences. Her social work background includes extensive experience in direct

social service provision with immigrant and refugee communities experiencing domestic vio-

lence, sexual assault, mental illness, poverty, and employment discrimination.

xx The Contributors

ALEXEI DUNAWAY is the executive director of Ongoza, an accelerator for youth-led social

businesses in Nairobi, Kenya. Previously he contributed to several human rights trials in Spain,

the United States, and El Salvador; conducted research for Human Rights Watch and the Council

on Foreign Relations; and helped coordinate the world pilot of a youth-led community mapping

initiative at the Centro de Promoção da Saúde (CEDAPS) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He also

served as a Fulbright research scholar in Mozambique.

EUGENIA ENG, MPH, DrPH, is professor of health behavior at the Gillings School of Global

Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has more than thirty years of

CBPR experience, including eld studies conducted with rural communities of the US South,

Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia to address socially stigmatizing health problems such

as pesticide poisoning, cancer, and STI-HIV. Her CBPR projects include the NCI-funded

Accountability for Cancer Care through Undoing Racism and Equity, the CDC-funded Men

As Navigators for Health, the NCI-funded Cancer Care and Racial Equity Study, the NHLBI-

funded CVD Black Church: Are We Our Brother’s Keeper? In addition to her coedited book,

Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research for Health, she has more than 115 pub-

lications on the lay health advisor intervention model, the concepts of community competence

and natural helping, and community assessment procedures.

JESSICA ESTRADA is a health program coordinator at the San Francisco Department of

Public Health Community Health Equity & Promotion Branch, and formerly co-coordinator

of the Tenderloin Healthy Corner Store Coalition. She received her bachelor of science from

the University of California, Davis, and has worked in public health, youth development, and

community organizing, with a passion for health equity, since 2006.

JENNIFER FALBE, ScD, MPH, is an assistant professor of nutrition and human development

at the University of California, Davis. Her research focuses on evaluating policies and programs

to reduce health disparities and improve diet quality, such as soda taxes, healthy retail pro-

grams, and primary care and community interventions.

STEPHEN FAWCETT, PhD, is senior advisor in KU Center for Community Health and

Development, and codirector of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for

Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas. Author of nearly two hundred

publications and cofounder of the Community Tool Box, his research examines how collabora-

tive action affects improvements in population health and equity.

SARAH FLICKER, PhD, is associate professor in the Faculty of Environmental Studies at

York University in Toronto, Canada. Her program of research focuses on youth environmental,

sexual, and reproductive justice issues. Her research has informed policy at the municipal, pro-

vincial, and federal levels. Flicker and her teams have won a number of prestigious awards for

youth engagement in health research.

VINCENT FRANCISCO, PhD, is Kansas Health Foundation Professor of Community Leader-

ship and senior scientist with the Schiefelbusch Institute for Life Span Studies. He is codirector

The Contributors xxi

of the KU Center for Community Health and Development, a World Health Organization

Collaborating Centre at the University of Kansas.

NICHOLAS FREUDENBERG, DrPH, is Distinguished Professor of Public Health at the City

University of New York Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy, where he also

directs the CUNY Urban Food Policy Institute. For the past thirty years, he has developed,

implemented, and evaluated community health policies and programs designed to improve the

health and reduce health inequalities facing vulnerable urban populations.

CATALINA GARZÓN, PhD, has coordinated CBPR, leadership development, action planning,

and curriculum development partnerships with environmental and social justice organizations

and coalitions for more than twenty years. Her recent collaborations include a photo-novella

on alternatives to the criminalization of youth with Communities United for Restorative Youth

Justice and a Health Impact Assessment of freight transport planning with the Ditching Dirty

Diesel Collaborative. Garzón is a recipient of the Thomas I. Yamashita Prize honoring out-

standing social change activists who serve as a bridge between academia and the community.

LAWRENCE W. GREEN, DrPH ScD (Hon), emeritus professor of epidemiology and biosta-

tistics at the University of California at San Francisco, served as director of the US Ofce of

Health Information and Health Promotion under the Carter Administration and director of the

Ofce of Science and Extramural Research at CDC. He has been on the full-time faculties of

UC Berkeley, Johns Hopkins University, Harvard, the University of Texas, and the University

of British Columbia. He headed a Canadian team in producing the rst study of participatory

research in health promotion for the Royal Society of Canada.

DEREK M. GRIFFITH, PhD, is associate professor of medicine, health, and society and

founder and director of the Center for Research on Men’s Health at Vanderbilt University. In

November 2013, Grifth was presented with the Tom Bruce Award by the Community-Based

Public Health Caucus of the American Public Health Association in recognition of his leader-

ship in community-based public health and for his research on “eliminating health disparities

that vary by race, ethnicity, and gender.”

ADRIAN GUTA, MSW, PhD, is assistant professor at the School of Social Work, University

of Windsor, Canada. His research examines the social, cultural, and ethical dimensions of HIV

prevention, treatment, and care; related clinical and social service programing; and public health

interventions through a combination of critical theoretical work and applied CBPR.

J. RICARDO GUZMAN, MSW, MPH, served as CEO for the Community Health and Social

Services Center (CHASS), a federally qualied health center, in Detroit from 1982 through

2016. During his tenure, he increased funding for the uninsured and underinsured residents

of Detroit, focusing on African American and Latino communities, and broadened services to

include domestic violence and sexual assault programs and CBPR efforts to address underlying

causes of health disparities in minority populations. He has received national and local awards

for his role in expanding access to culturally and linguistically appropriate health services.

xxii The Contributors

Guzman currently serves as chairperson of the board of directors for the National Association of

Community Health Centers in Washington, DC.

BUDD HALL, PhD, is professor of community development at the University of Victoria and

UNESCO co-chair in community- based research and social responsibility in higher education.

He has been working within a participatory research framework since 1973.

SUSANA HENNESSEY LAVERY, MPH, is health educator with the San Francisco Department

of Public Health, Community Health Equity and Promotion Branch (1992 to present). She

codesigns and implements the CAM (community action model) for policy development with

San Francisco’s diverse communities. She played a lead role in development of healthy retail

efforts, is the SFDPH staff member for the HealthyRetailSF program, and sits on the steering

committee of the Tenderloin Healthy Corner Store Coalition. For more than a decade, she has

participated on the Bay Area committee of Vision y Compromiso, a statewide community health

worker network. She is coauthor of numerous professional publications.

CHRISTINA HOLT serves as the associate director for Community Tool Box services at the KU

Center for Health Promotion and Community Development, where she directs the Community

Tool Box, a free global resource that offers seven thousand pages of practical guidance for cre-

ating change and improvement. She has served as a speaker and technical consultant for groups

including the World Health Organization, World Bank, United Nations, Peace Corps, and Insti-

tute of Medicine.

CHERYL HYDE, MSW, PhD, is associate professor at Temple University, School of Social

Work. Her primary areas of scholarship and teaching are organizational and community capacity

building, multicultural education, feminist praxis, social movements and collective action, and

socioeconomic class issues. She is a past president of the Association for Community Organi-

zation and Social Administration, former editor of the Journal of Progressive Human Services,

and a member of several social science and social work editorial boards and has practice expe-

rience in feminist, labor, and anti-oppression movements.

NADIA ISLAM, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Population Health at

NYU School of Medicine. She is deputy director of the NYU Center for the Study of Asian

American Health and the research director for the NYU-CUNY Prevention Research Center.

She serves as PI on numerous federally funded initiatives evaluating the impact of culturally

adapted community- clinical linkages strategies on improving health outcomes in racial and

ethnic minority communities. Islam’s work has been featured in Diabetes Care, the American

Journal of Public Health, and other peer-reviewed journals.

BARBARA A. ISRAEL, DrPH, MPH, is professor of health behavior and health education,

School of Public Health, University of Michigan. She has published widely and is actively

involved in a number of CBPR partnerships examining and addressing, for example, the social

and physical environmental determinants of health inequities in cardiovascular disease and

childhood asthma and capacity building for and translating research ndings into policy change.

The Contributors xxiii

JUSTIN JAGOSH, PhD, is honorary research associate, Institute for Psychology, Health and

Society, University of Liverpool, and director for the Centre for Advancement in Realist Eval-

uation and Synthesis (www.liv.ac.uk/cares). He was coinvestigator on a comprehensive realist

review and evaluation of the CBPR. He runs regular training workshops in realist methodology,

including an annual summer school and a biennial international realist methodology conference.

See his website at www.realistmethodology-cares.org.

CAMARA PHYLLIS JONES, MD, MPH, PhD, a family physician and social epidemiolo-

gist, focuses on naming, measuring, and addressing the impacts of racism on the health and

well-being of the nation. Her allegories on race and racism illuminate topics that are otherwise

difcult for many Americans to understand or discuss. She is past president of the American

Public Health Association and a senior fellow at the Satcher Health Leadership Institute and

Cardiovascular Research Institute at the Morehouse School of Medicine. She was previously an

assistant professor, Harvard School of Public Health (1994 to 2000), and a medical ofcer at the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000 to 2014).

NORA JONES, MS, is executive director of the Partnership Project and the founding president

of Sisters Network Greensboro, a national breast cancer survivorship organization for African

American women. Currently, she is the lead community coinvestigator for the ACCURE

(Accountability for Cancer Care Through Undoing Racism and Equity) Research Study.

MIRIA KANO, PhD, research investigator, Department of Family and Community Medi-

cine, University of New Mexico, is the director of regional coordination for the geographic

management of cancer health disparities program region 3. She served as PI on the Patient-

Centered Outcomes Research Institute Pipeline to Proposal Award (highlighted in Appendix 2).

Kano has been a coinvestigator and research team member on four federally funded research

grants, as well as senior program manager for the New Mexico Center for the Advancement

of Research, Engagement and Science on Health Disparities, a P-20 center funded through the

National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities.

SARAH L. KASTELIC, PhD, MSW, is executive director of the National Indian Child Wel-

fare Association, where she serves as PI on several federally funded projects addressing the

well-being of American Indian and Alaska Native children. She is a citizen of the Native village

of Ouzinkie near Kodiak, Alaska, and the founding director of the Policy Research Center at the

National Congress of American Indians.

DMITRY KHODYAKOV, PhD, is senior behavioral-social scientist at RAND and core fac-

ulty member at Pardee RAND Graduate School. He specializes in methods of stakeholder and

patient engagement, expert elicitation, and intervention evaluation. Khodyakov is the author of

more than forty-ve peer-reviewed publications and has served as PI or co-PI on research pro-

jects funded by PCORI, NIEHS, and CMS, among others.

LAURA C. LEVITON, PhD, is senior advisor for evaluation at the Robert Wood Johnson

Foundation in Princeton, New Jersey, having overseen more than 120 national, state, and local

xxiv The Contributors

evaluations and a wide variety of other social research related to health. Leviton has coauthored

three books: Foundations of Program Evaluation (Sage, 1991), Confronting Public Health

Risks (Sage, 1997), and Managing Applied Social Research (Wiley, 2017).

RICHARD LICHTENSTEIN, PhD, recently retired as S. J. Axelrod Collegiate Professor of

Health Management and Policy at the University of Michigan School of Public Health, where

he taught for more than forty years. His research interests include CBPR, racial and ethnic dis-

parities in health, barriers to health insurance coverage for low-income children, and efforts to

increase diversity in the health workforce.

ALEXANDRA LIGHTFOOT, EdD, is research assistant professor in the Department of Health

Behavior in the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina

at Chapel Hill. She also directs the Community Engagement, Partnerships and Technical

Assistance Core at the Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, a CDC-sponsored

prevention research center. She conducts research using the CBPR approach in collaboration

with communities across North Carolina and provides training and technical assistance to build

and strengthen community-academic research partnerships.

ALISA LINCOLN, MPH, PhD, is interdisciplinary professor of Sociology and Health Sciences

and the director of the Institute on Urban Health Research and Practice at Northeastern Univer-

sity. Lincoln’s research examines the way that social exclusion and marginalization contribute

to and are a consequence of poor mental health. She has led the way in developing innovative

models by which we can increase the involvement of stakeholders and mental health service

users in the process of research through her NIMH-funded CBPR projects.

JULIE E. LUCERO, MPH, PhD, is assistant professor in the School of Community Health Sci-

ences at the University of Nevada, Reno. She is a mixed-methods researcher who uses CBPR to

promote social justice and health equity. She researches trust in community-academic partner-

ships, social determinants, diversity and inclusion, and research ethics.

MAYA MAGARATI, PhD, is a sociologist at the Indigenous Wellness Research Institute (IWRI)

in the University of Washington’s School of Social Work, where she serves as the associate

director of the Community Engagement and Outreach Core. She has served as a coinvestigator

in multiple federally funded participatory research studies to cocreate knowledge with Indige-

nous communities focused on culture-centered behavioral health protective factors.

JACK MAKAU is executive director of Shack/Slum Dwellers International–Kenya (SDI-

Kenya). He has almost twenty years of experience with mapping and surveying informal set-

tlements. He has worked in cities across Africa and advised the UN-Habitat, World Bank, and

numerous organizations on participatory slum upgrading.

LILLI MANN, MPH, is research associate in the Department of Social Sciences and Health

Policy at Wake Forest School of Medicine. She is involved in the development, implementation,

and evaluation of CBPR studies, focusing on interventions promoting health services access,

The Contributors xxv

sexual and reproductive health, HIV prevention, HIV care linkage, and retention among racial

and ethnic minority and sexual and gender-identity minority communities.

KELLY MATTHEWS, BSW, is outreach coordinator for the Rochester Prevention Research

Center: National Center for Deaf Health Research. Matthews has worked in the Deaf community

in the elds of HIV/AIDS, mental health, supported employment, obesity, and multiple public

health initiatives.

ELI MOORE, MA, was cofounder of the Safe Return Project and has facilitated CBPR processes

with environmental justice communities, farm workers, youth, and others over the last fteen

years. Eli is currently a program manager at the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society

at UC Berkeley.

RACHEL MORELLO-FROSCH, PhD, is an environmental health scientist and professor in the

School of Public Health and the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management

at the University of California, Berkeley. Her research examines social determinants of environ-

mental health disparities among diverse communities in the United States with a focus on envi-

ronmental chemicals, air pollution, and climate change.

THE MORRIS JUSTICE PROJECT (MJP) is a collaborative research team of neighborhood

residents in the south Bronx and members of the Public Science Project, the CUNY Graduate

Center, John Jay College, and Pace University Law Center. The project was founded in 2011

after a group of local mothers, whose sons had been harassed by police as a result of a stop-

and-frisk policy disproportionately affecting African Americans and Latinos, decided to take

action. MJP’s research includes large community surveys and “sidewalk science,” for example,

temporary art installations in public spaces to gather and share data on residents’ concerns. The

collective has shared its research in numerous venues including the 2015 Citizen Science Forum

at the White House.

MICHAEL MUHAMMAD, PhD, is the current Paul B. Cornely Postdoctoral Fellow in the

University of Michigan’s School of Public Health Center for Research on Ethnicity, Culture,

and Health (CRECH). His work focuses on contemporary racism, eugenic ideology, struc-

tural inequality, and the evaluation of CBPR partnerships including the Detroit Community-

Academic Urban Research Center University of Michigan.

JENNIFER NALL, MPH, is health-promotion disease-prevention director at the Forsyth County

Health Department in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. She has worked in the eld of HIV/STIs

for more than fteen years and has experience with HIV counseling and testing, community-

based interventions, and program evaluation.

EMILY J. OZER, PhD, is clinical-community psychologist, professor of community health

sciences at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health, and cofounder of the Innovations for

Youth (I4Y) Center. She has authored more than sixty articles in participatory research, trauma

and resilience, and school-based interventions (funded by NIDA, NICHD, William T. Grant

xxvi The Contributors

Foundation, and CDC). Learning experiences with participatory research in India and Latin

America inspired her dual foci on youth-led participatory research and psychological resil-

iency in the face of stress and trauma. Ozer seeks equitable and sustained collaborations to

challenge rigid notions of evidence and to highlight insider expertise in changing the conditions

for positive development of marginalized adolescents and their communities.

LAURA CHANCHIEN PARAJÓN, MD, MPH, is the medical director and cofounder of the

nonprot organization AMOS Health and Hope. Based in Nicaragua, AMOS is dedicated to

using community-based and empowering approaches to reduce health disparities in Nicaragua.

She is passionate about applying CBPR frameworks in global health as well as training health

professionals and community health workers in CBPR principles and practice.

EDITH A. PARKER, DrPH, MPH, is professor and chair of the Department of Community

and Behavioral Health, University of Iowa College of Public Health, and was previously

associate professor at University of Michigan School of Public Health. Her research focuses on

community- engaged health promotion interventions. She has served as the PI or Co-PI on more

than twenty federally funded grants.

MYRA PARKER, JD, PhD, is an enrolled member of the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes and serves

as an assistant professor in the Center for the Study of Health and Risk Behavior in the University

of Washington School of Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry. Her research experience as a

coinvestigator on public health research with American Indian and Alaska Native communities

involves CBPR and disparities research funded through NIMHD, NIAAA, NIDA, and NIDDK.

CYNTHIA PEARSON, PhD, is the director of the research at the Indigenous Wellness Research

Institute. She is the author of more than sixty scientic publications and has served as a principal

and coinvestigator on more than thirty-two federally funded grants using an CBPR approach in

developing ethical research training curriculum, conducting studies on epidemiology of HIV

prevention and co-occurring mental and drug use disorders, and developing trauma-informed

HIV-prevention interventions among American Indian and Alaska Natives.

AMBER AKEMI PIATT, MPH, works at PolicyLink with the Convergence Partnership, advising

funders on strategies to advance health and equity through policy and practice changes. She

also serves on the Innovations for Youth (I4Y) community advisory board, Alameda County

Human Relations Commission, and the Sea Change Program’s advisory board. She has worked

on CBPR and YPAR projects since 2010 and sees participatory research as a critical way to

democratize knowledge and build community power.

MICHELE POLACSEK, PhD, MHS, is associate professor of public health at the University

of New England and recently served as PI on three grants examining school food and bev-

erage marketing environments, including digital marketing. She also recently served as lead

investigator on two studies evaluating innovative approaches to promote nutrition among low-

income populations in a supermarket setting. Michele has taught CBPR online and worked to

develop innovative teaching tools for this setting.

The Contributors xxvii

ABIGAIL REESE, CNM, MSN, is a doctoral candidate in health policy at the UNM College

of Nursing, and a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Nursing and Health Policy Collabora-

tive Fellow. She is a certied nurse-midwife with extensive clinical and teaching experience in

diverse practice settings. She currently serves as the program director for the New Mexico Peri-

natal Collaborative. Her research focuses on access to care for underserved women.

ANGELA REYES, MPH, is the founder and executive director of Detroit Hispanic Development

Corporation, a nonprot community-based organization that works to create individual-level

change with youth and families and community systems–level change. She is also a founding

board member of the Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center, established in

1995, which involves multiple funded collaborative research and intervention projects aimed at

increasing knowledge and addressing factors associated with health disparities of residents in

Detroit, Michigan.

SCOTT D. RHODES, PhD, MPH, FAAHB, is professor and chair of the Department of

Social Science and Health Policy, Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, North

Carolina. He is director of the Program in Community Engagement within the Wake Forest

Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Rhodes currently has published more than 150

articles and thirty book chapters. His community-engaged and CBPR has been funded by the

National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Health

Resources & Services Administration (HRSA), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, amfAR:

The American Foundation for AIDS Research, the Cone Health Foundation, and the Kate B.

Reynolds Foundation.

AL RICHMOND, MSW, executive director of Community Campus Partnerships for Health

(CCPH), has a career that has uniquely blended social work and public health to address racial

and ethnic health disparities. As an international community health leader, Richmond advocates

for transformative partnerships to address the most critical issues facing our society. He is ada-

mant that “no meaningful and impactful change in our society is possible without partnerships.

Partnerships are not an option, but an imperative.”

LINDA ROBERTSON DrPH, RN, MSN, is associate director, health equity, education

and advocacy at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) and assistant pro-

fessor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. She focuses her efforts and research on

building community partnerships and addressing health equity issues along the cancer care

continuum.

IVES ROCHA is a psychologist from Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and has worked

with public health, health promotion, and grassroots development since 2007. He is program

technical advisor of CEDAPS—The Centre for Health Promotion—and coordinator of youth-

led digital mapping in Brazil, a global initiative of UNICEF. He develops and monitors par-

ticipatory methodologies, especially with adolescents and young people. Ives is procient in

Construção Compartilhada de Soluções Locais social technology, consisting of participatory and

local-based diagnostic, plans of action, monitoring, and evaluation of grassroots experiences.

xxviii The Contributors

PATRICIA RODRÍGUEZ ESPINOSA, MS, MPH, is a doctoral candidate in clinical

psychology, University of New Mexico; a Robert Wood Johnson fellow, UNM Center

for Health Policy; and a psychology intern with VA Palo Alto Health Care System, afl-

iated with Stanford. Her research centers on the health of Latino and other minorities in

the U.S. with special attention to the role of cultural and social determinants of health in the

development of health disparities. She is interested in the application of CBPR in multicul-

tural psychology.

LETICIA RODRIGUEZ GARCIA, MPH, Community Health Worker (CHW) is a graduate

research assistant at Portland State University. She has more than fteen years of experience as

a CHW. Her research interests include CBPR, the roles of CHWs, and health disparities among

immigrant communities. She has presented at various local and national conferences on CHW

research–related efforts.

CLEO SAMUEL, PhD, is assistant professor of health policy and management at the University

of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is a health services researcher with expertise in cancer

care disparities and health informatics.

VICTORIA SÁNCHEZ, DrPH, associate professor in the College of Population Health at

the University of New Mexico, focuses her research on how people come together and build

capacity to enhance health equity and community well-being.

SHANNON SANCHEZ-YOUNGMAN, PhD, is a research assistant professor and political

scientist at the University of New Mexico. Her research focuses on the development and impact

of health and social policy on women of color and children in the United States.

KELLEY P. SAWYER is a PhD candidate in anthropology at the University of New Mexico.

JENNIFER SCHAAL, MD, retired ob-gyn, is a founding member of the Greensboro Health

Disparities Collaborative (GHDC) and an active antiracist organizer. She was a clinical

investigator for hormone replacement research while in practice and has participated actively

in the CBPR work of the GHDC. She has served on community research advisory boards for

local and national research grants; has copresented multiple CBPR workshops, keynotes, and

research presentations; and has coauthored peer-reviewed publications and book chapters.

JERRY SCHULTZ, PhD, is co-director of the KU Center for Community Health and

Development at the University of Kansas. His work is focused on building the capacity of

communities to solve local problems, understanding community and systems change, eval-

uating community health and development initiatives, and developing methodologies for

community improvement. He has coauthored numerous articles on evaluation, empowerment,

and community development. He has been a consultant to foundations, community coalitions,

and state agencies. Schultz was given the Society for Community Research and Action Award

for Distinguished Contribution to the Practice of Community Psychology in 2007 and is a fel-

low of the Society for Applied Anthropology.

The Contributors xxix

AMY J. SCHULZ, PhD, MPH, is professor of health behavior and health education at the

University of Michigan School of Public Health. She has served as PI for the Healthy

Environments Partnership since 2000 and multi-PI for community action to promote healthy

environments since 2014, both CBPR partnerships focused on environmental justice and health

equity in Detroit. She has authored more than 130 professional publications and has served as

PI on eleven federally funded research grants.

LAURO SILVA is a native-born New Mexican from the Capitan Mountains. As a grassroots

organizer and legal professional, Lauro has worked for social justice for ve decades with rural

and urban communities in public policy, community organizing, and law, especially for poor

Chicanos/as, Mexican immigrants, and Native Americans. He has worked with New Mexico’s

asylum refugees from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador; with the Migrant Farmworker

Councils and Clinics; and with the environmental civil rights health movement. Among

many positions, he has been president of the Mountain View Neighborhood Association and

community PI of the South Valley Partners for Environmental Justice in Albuquerque.

FLORENCE M. SIMÁN, MPH, is the director of health programs at El Pueblo, an organiza-

tion based in Raleigh, North Carolina, whose mission is for Latinxs to achieve positive social

change. Florence is a founding board member of El Pueblo. She has worked on several pho-

tovoice projects, some led by UNC students, and is passionate about using photos as a tool to

encourage dialogue and to advocate for social justice.

BETH SMITH, RN, NE-BC, MSN, is the professional services practice manager at the

Cone Health Cancer Center. She has served as the oncology navigator for the ACCURE

Research Study.

ANDREW SUSSMAN, PhD, MCRP, is assistant professor in the Department of Family and

Community Medicine at the University of New Mexico. He is the director of RIOS Net, a

practice-based research network and has conducted research on a variety of primary care health

disparities topics among medically underserved populations in New Mexico.

ERIKA SUTTER, MPH, is deputy director of the Rochester Prevention Research Center: National

Center for Deaf Health Research at the University of Rochester Medical Center. She has worked

with RPRC/NCDHR since 2004 and is skilled in American Sign Language (ASL). Her research

experience includes the design, implementation, and dissemination of research studies and

community- based initiatives in the areas of Deaf health, health disparities, community health and

CBPR, adolescent health and mental health, adolescent access to care, and youth development.

RAJESH TANDON, PhD, is internationally acclaimed in participatory research, and founder and

director of the Society for Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA), providing support to grassroots

initiatives in South Asia. He has championed capacity building of the marginalized through their

knowledge and empowerment and has authored more than one hundred articles, a dozen books,

and training manuals on democratic governance, civic engagement, participatory research, and

people-centered development. For his work on gender, he received the Government of India’s

xxx The Contributors

Social Justice award, 2007; is the rst Indian inducted into the International Adult and Continuing

Education Hall of Fame, 2011; and was appointed UNESCO co-chair on Community-Based

Research and Social Responsibility in Higher Education (2012–2016 and 2016–2020).

AMANDA E. TANNER, PhD, MPH, is associate professor in the Department of Public Health

Education at the University of North Carolina Greensboro. Her research focuses on sexual and

reproductive health with specic areas of expertise including HIV and sexually transmitted

disease prevention, HIV care, intervention science, and microbicide and contraceptive access

and acceptability. She has served as PI or coinvestigator on multiple federally funded research

grants and has more than fty peer-reviewed publications.

PAM TAU LEE, BA, is a retired instructor at City College of San Francisco and a former

project director at the Labor Occupational Health Center, School of Public Health, University of

California, Berkeley. She also was a founding member of the Chinese Progressive Association,

San Francisco, and the Asian Pacic Environmental Network. A long-time activist and practi-

tioner of popular education, community organizing, and CBPR, she has made major contribu-

tions to improving the working conditions of immigrants and women.

KARI THATCHER, MPH, is the prevention specialist at the North Carolina Coalition Against

Domestic Violence and began serving as cochair of the Greensboro Health Disparities Collab-

orative in January 2017. She takes a network-oriented approach to community and institutional

organizing, driven by a belief in the importance of leadership and capacity building at the neigh-

borhood level. She also works independently, training and consulting with organizations and

communities working for racial equity.

RYAN THAYER, MA, is a community organizer and co-coordinator of the Tenderloin Healthy

Corner Store Coalition. As a sixth-generation San Franciscan, he holds a BA in urban studies and

planning from San Francisco State University and an MA in urban affairs from the University of

San Francisco. Since 2010, Thayer has cultivated community leadership to participate in a food

system that promotes equity and justice.

MAKANI N. THEMBA is chief strategist at Higher Ground Change Strategies based in Detroit,

Michigan. A social justice innovator and pioneer in the eld of change communications and

narrative strategy, she has spent more than twenty years supporting organizations, coalitions,

and philanthropic institutions in developing high-impact change initiatives. Higher Ground

Change Strategies is her newest project, which she describes as “a place where change makers

can get the support they need to take their work to the next level.” Higher Ground helps partners

integrate authentic engagement, systems analysis, and change communications and more for

powerful, vision-based change.

ROBB TRAVERS, PhD, is associate professor and chair, Department of Health Sciences,

Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario. He is director of the Equity, Sexual Health and

HIV Research Group at Laurier’s Centre for Community Research, Learning and Action. His

CBPR focuses on social exclusion and its impact on the health of gender and sexual minorities.

The Contributors xxxi

CHAU TRINH-SHEVRIN, DrPH, is associate professor of population health and medicine at

the NYU School of Medicine and directs the Department of Population Health’s Section for

Health. Trinh-Shevrin is PI and founding director of the NIH NIMHD Center of Excellence, the

Center for the Study of Asian American Health, and co-PI of a CDC-sponsored NYU-CUNY

Prevention Research Center. She has more than ninety peer-review scientic and professional

publications.

LAVERN VAUGHN is case manager for Catholic Charities of San Francisco and a founding

member of The Safe Return Project in Richmond, California. The Safe Return Project is a

participatory action research process involving formerly incarcerated residents in conducting

research, engaging community members, and developing policy proposals to reduce recidivism

and improve community health and safety. During her years with Safe Return, Vaughn and

seven other Safe Return leaders conducted an extensive survey of recently released residents,

interviewed more than six hundred community members, and researched and developed pol-

icies that have been adopted at the city, county, and state level. Vaughn is a lifelong Richmond

resident, mother, grandmother, and passionate advocate for justice and her community.

AARON T. VISSMAN, PhD, MPH, is associate director of the Center for Health and Human

Services Research at Talbert House in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has published mixed-methods

research investigating correlates of antiretroviral adherence and the effectiveness of multilevel

HIV/AIDS prevention interventions. He received the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research

Service Award (2013–2015). Ongoing studies investigate multilevel correlates of naloxone dis-

tribution and the effectiveness of opioid overdose and HCV prevention interventions.

TAMISHA WALKER is founder and executive director of Safe Return Project. Walker has

been a Richmond-based community organizer and known advocate on issues related to mass

incarceration and racial disparity in the criminal justice system since her release from incar-

ceration in 2009. Tamisha shares a powerful personal story about the journey to healing and

successful reentry. She has six years of community-organizing experience in a city affected

by trauma and economic inequality, including her own personal experience with trauma and

poverty growing up in Richmond, California. Her educational experience includes professional

training in research and advocacy for the formerly incarcerated and their families, violence-

prevention strategies, and conict mediation to reduce urban gun violence.

PEI-RU WANG, PhD, is senior research and evaluation analyst at the Multnomah County

Health Department Community Capacitation Center in Oregon. She leads a number of eval-

uation projects on community health worker and community leadership programs. She is also

a seasonal facilitator and trainer using popular education, inspired by Paulo Freire. She has

years of experience working in a nonprot organization supporting CHWs in the Asian Pacic

Islander, African, and Slavic communities.

JOMELLA WATSON-THOMPSON, PhD, is associate professor of applied behavioral sci-

ence and associate director for the KU Center for Community Health and Development at the

University of Kansas. She leads participatory research and evaluation efforts in the areas of

xxxii The Contributors

adolescent substance abuse prevention, community and youth violence prevention, and positive

youth development.

KENNETH B. WELLS, MD, MPH, is afliated adjunct staff at RAND and David Weil

Endowed Professor of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences at UCLA David Geffen School of

Medicine and of Health Policy and Management at UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. He

is director of the Semel Institute Center for Health Services and Society and codirector of the

California Behavioral Health Center of Excellence and Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars

Program at UCLA. His research focuses on improving mental health outcomes, particularly

depression, through a community-partnered, participatory research approach.

WEST OAKLAND ENVIRONMENTAL INDICATORS PROJECT (WOEIP) is a nonprot

dedicated to working with neighborhood organizations, physicians, researchers, and public

ofcials to ensure West Oakland residents have a clean environment, safe neighborhoods, and

access to economic opportunity. It is codirected by Brian Beveridge, and Margaret Gordon, who

has received multiple city, county, and Bay Area honors for her environmental justice work.

NOELLE WIGGINS, EdD, MSPH, is director of Capacity Building and Collaboration, Whole

Person Care Program, LA County Dept. of Health Services. Previously, director at Multnomah

County Community Capacitation Center Portland, Oregon, she has more than thirty years training

and supervising community health workers (CHWs). Publications and presentation topics include

CHWs, popular education, participatory research and evaluation, and empowerment theory and

measurement.

CATHLEEN E. WILLGING, PhD, is center director and senior research scientist at Behavioral

Health Research of the Southwest, Pacic Institute for Research and Evaluation. As a medical

anthropologist, her research focuses on public mental health and substance use services in the

United States, health care reform, implementation science, and the advancement of culturally

and contextually relevant programs to support populations affected by health and health care

disparities.

KATHRINE E. WRIGHT, MPH, is a public health doctoral student at the University of Nevada,

Reno, specializing in social and behavioral health. She received her master of public health

degree at Michigan State University, where she specialized in public health nutrition. Her

research interests include using CBPR to address the causes and impacts of food insecurity and

hunger to promote health equity in marginalized populations.

MICHAEL T. WRIGHT, LICSW, MS, has been involved in community-based health initiatives

since 1984 in the United States and Germany, having served as a psychotherapist, program man-

ager, clinical supervisor, researcher, and consultant. Wright was formerly the director of inter-

national relations at the Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe, the national German AIDS organization. He is

currently professor for research methods, Catholic University of Applied Sciences, Berlin, and

heads the central ofce of the International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research. He

is coordinator of PartKommPlus, a national research consortium in Germany applying partici-

patory health research to examine integrated municipal strategies for health promotion.

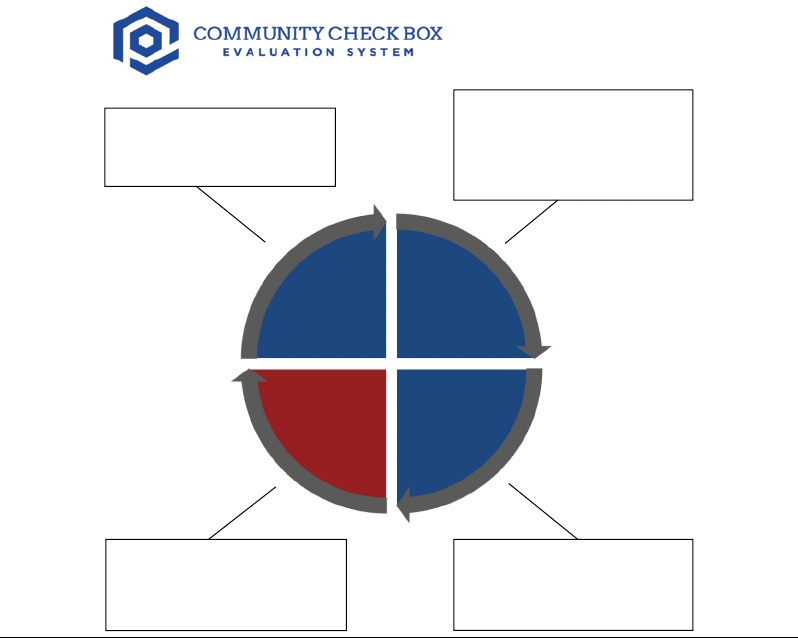

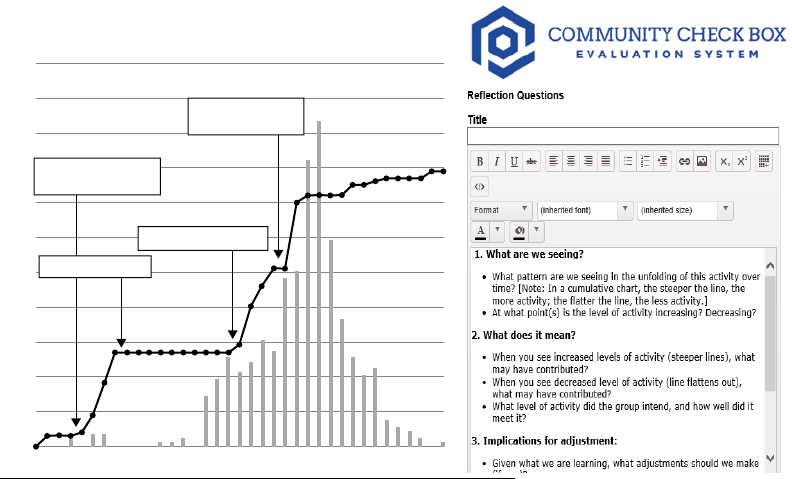

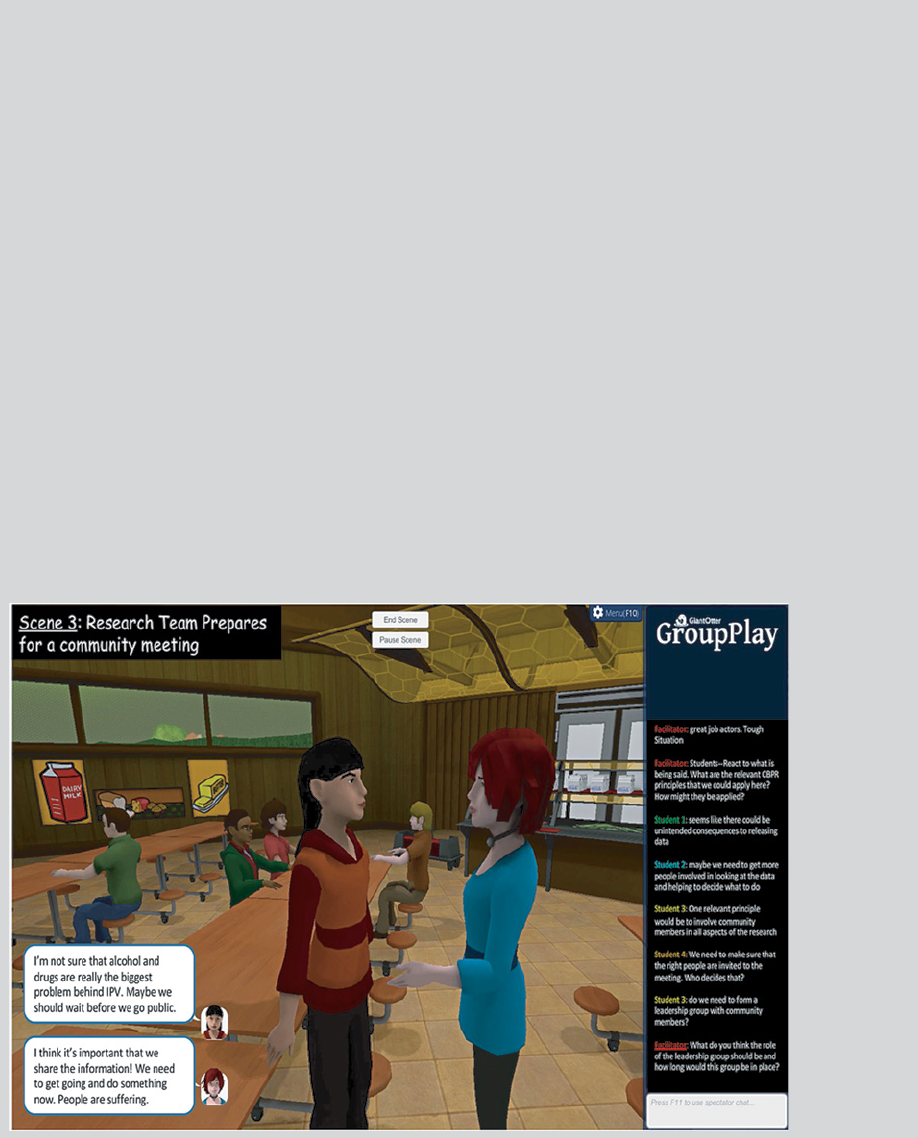

Health equity is assurance of the conditions for optimal health for all people.