U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy

EXITING THE MARKET:

UNDERSTANDING THE FACTORS

BEHIND CARRIERS’ DECISION TO

LEAVE THE LONG-TERM CARE

INSURANCE MARKET

July 2013

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

The Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) is the

principal advisor to the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services

(HHS) on policy development issues, and is responsible for major activities in the areas

of legislative and budget development, strategic planning, policy research and

evaluation, and economic analysis.

ASPE develops or reviews issues from the viewpoint of the Secretary, providing a

perspective that is broader in scope than the specific focus of the various operating

agencies. ASPE also works closely with the HHS operating divisions. It assists these

agencies in developing policies, and planning policy research, evaluation and data

collection within broad HHS and administration initiatives. ASPE often serves a

coordinating role for crosscutting policy and administrative activities.

ASPE plans and conducts evaluations and research--both in-house and through support

of projects by external researchers--of current and proposed programs and topics of

particular interest to the Secretary, the Administration and the Congress.

Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy

The Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy (DALTCP), within ASPE, is

responsible for the development, coordination, analysis, research and evaluation of

HHS policies and programs which support the independence, health and long-term care

of persons with disabilities--children, working aging adults, and older persons. DALTCP

is also responsible for policy coordination and research to promote the economic and

social well-being of the elderly.

In particular, DALTCP addresses policies concerning: nursing home and community-

based services, informal caregiving, the integration of acute and long-term care,

Medicare post-acute services and home care, managed care for people with disabilities,

long-term rehabilitation services, children’s disability, and linkages between employment

and health policies. These activities are carried out through policy planning, policy and

program analysis, regulatory reviews, formulation of legislative proposals, policy

research, evaluation and data planning.

This report was prepared under contract #HHSP23320100022WI between HHS’s

ASPE/DALTCP and Thomson Reuters. For additional information about this subject,

you can visit the DALTCP home page at http://aspe.hhs.gov/office_specific/daltcp.cfm

or contact the ASPE Project Officer, Samuel Shipley, at HHS/ASPE/DALTCP, Room

424E, H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C.

20201. His e-mail address is: Samuel.Shipley@hhs.gov.

EXITING THE MARKET:

Understanding the Factors behind

Carriers’ Decision to Leave the

Long-Term Care Insurance Market

Marc A. Cohen, PhD

Chief Research and Development Officer

LifePlans, Inc.

Ramandeep Kaur, MA

Heller School, Brandeis University

Bob Darnell, ASA, MAAA

Independent Consultant

July 2013

Prepared for

Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Contract #HHSP23320100022WI

The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect

the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, the contractor or any other funding

organization.

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... vi

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ v

I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1

II. PURPOSE ................................................................................................................. 3

III. METHOD AND ANALYSIS ....................................................................................... 4

A. Published Information Sources .......................................................................... 4

B. Survey of Industry Executives ............................................................................ 5

IV. FINDINGS .................................................................................................................. 7

A. Entering the Long-Term Care Insurance Market ................................................ 7

B. Market Evolution .............................................................................................. 11

C. The Decision to Exit the Market ....................................................................... 27

D. Current Market Activity ..................................................................................... 41

E. Factors that Might Lead Companies to Re-Enter the Market ........................... 45

V. IMPLICATIONS ....................................................................................................... 50

VI. CONCLUSION ......................................................................................................... 54

ii

LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES

FIGURE 1. Primary Motivations for Entering the Market .............................................. 8

FIGURE 2. Initial Business Strategy ............................................................................. 9

FIGURE 3. Evaluation of Most Volatile or Greatest Potential Future

Challenge at the Time of Market Entry..................................................... 10

FIGURE 4. New Sales of Individual Policies .............................................................. 16

FIGURE 5. Number of Insured Lives Covered by Year .............................................. 17

FIGURE 6. Annual Growth in Total Covered Lives..................................................... 18

FIGURE 7. Industry-Wide Actual Annualized Incurred Claims ................................... 20

FIGURE 8. Single Most Important Reason that the Company Left the

Market ...................................................................................................... 30

FIGURE 9. Moody’s Yield on Seasoned Corporate Bonds--All Industries,

AAA and Ten Year U.S. Treasury Note Yield Rate .................................. 32

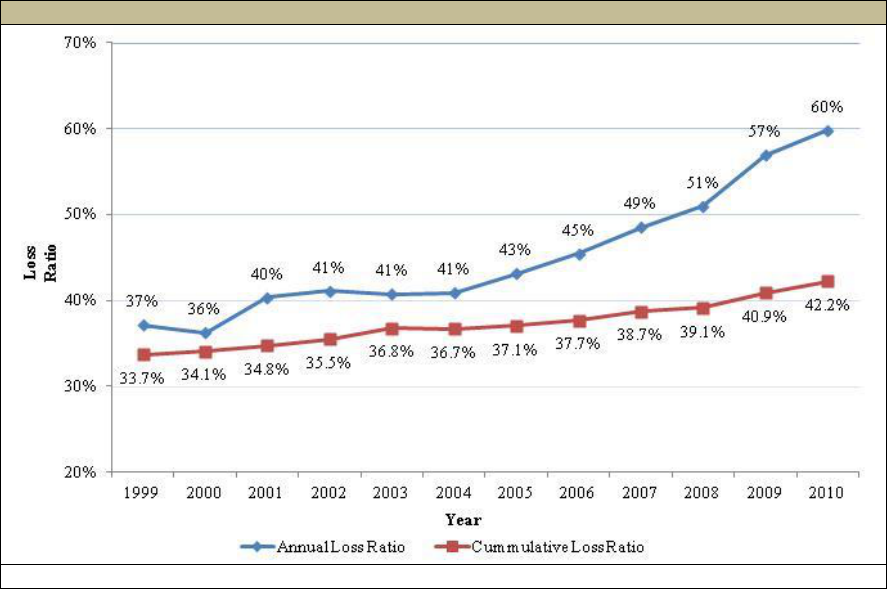

FIGURE 10. Annual and Cumulative Loss-Ratio .......................................................... 37

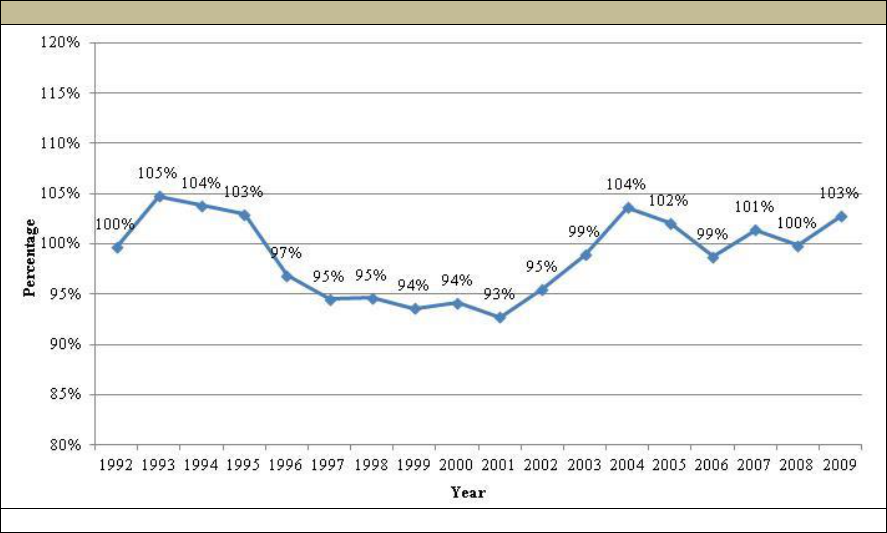

FIGURE 11. Industry-Wide Actual Losses to Expected Losses ................................... 38

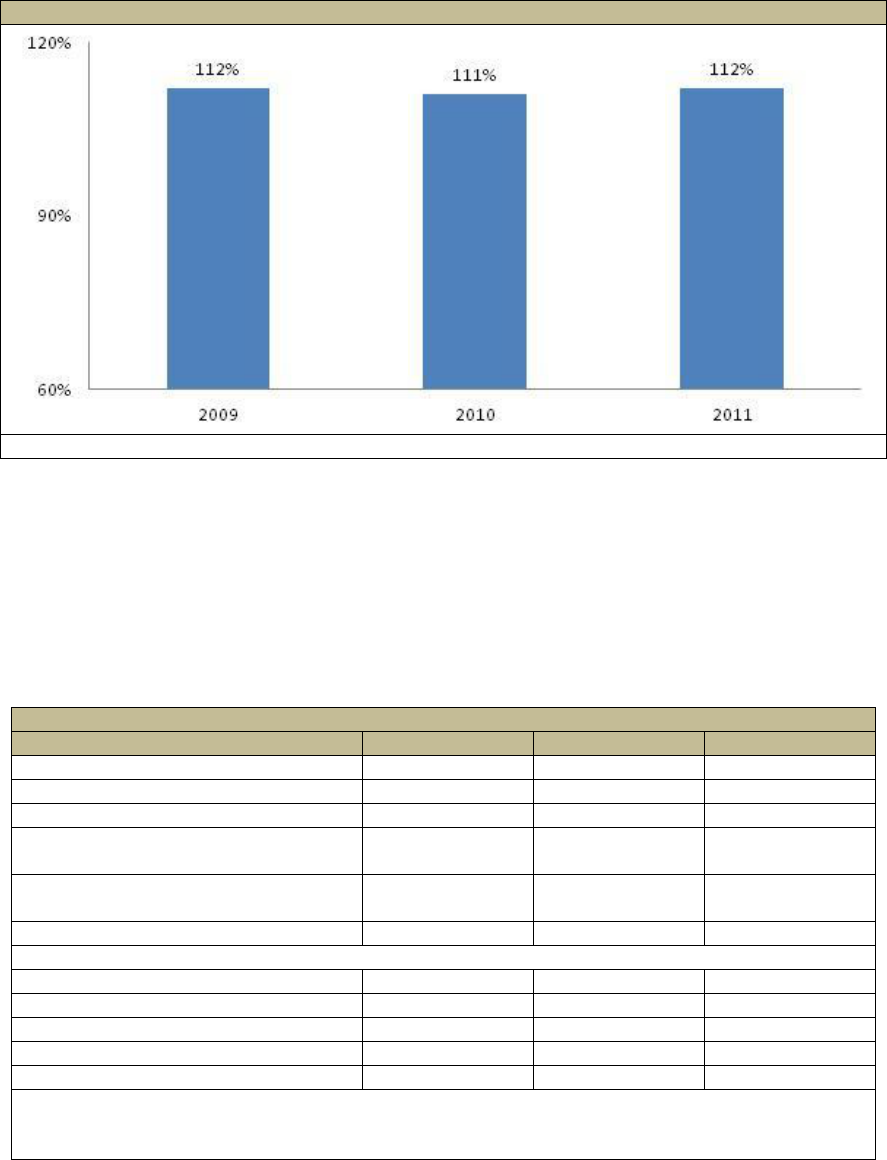

FIGURE 12. Industry Actual to Expected Annual Incurred Claims:

2009-2011 ................................................................................................ 39

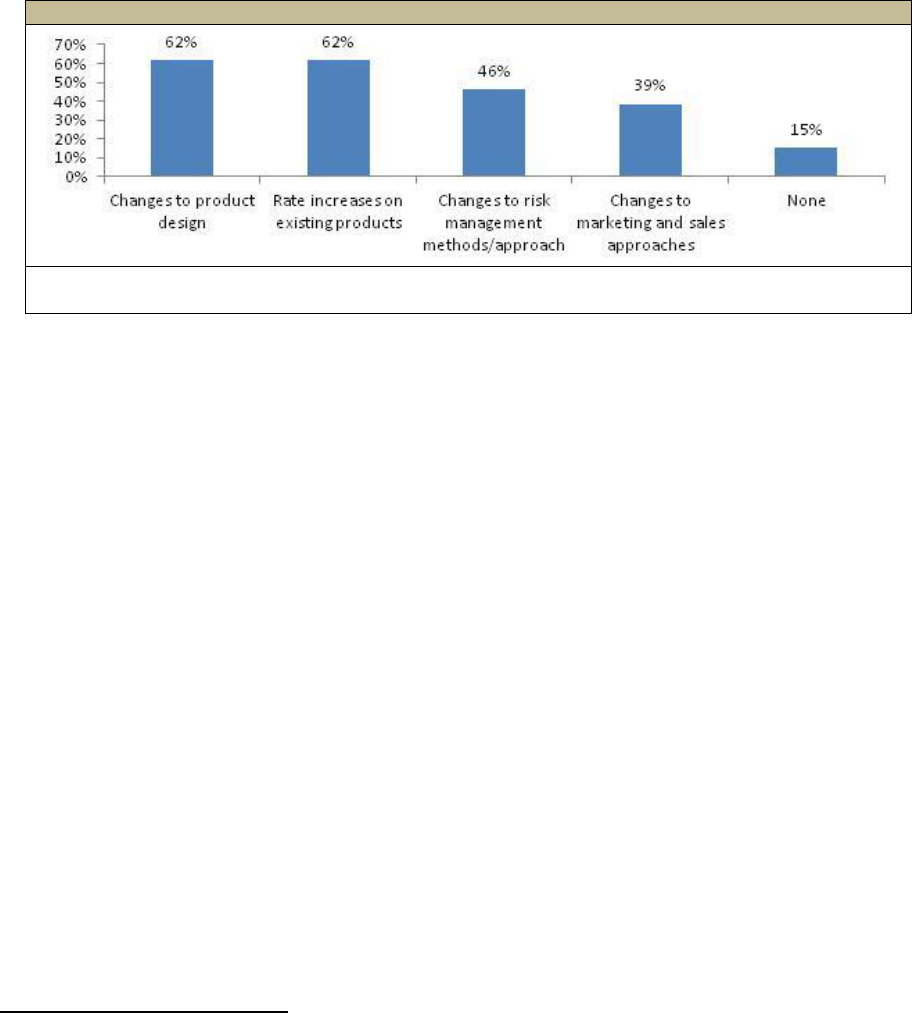

FIGURE 13. Actions taken Prior to Leaving the Market ............................................... 40

FIGURE 14. Level of Concern about Selling the Product if In-Force Rates

had to be Raised ...................................................................................... 41

FIGURE 15. Market Indicators by Company Sales Status 2009 .................................. 45

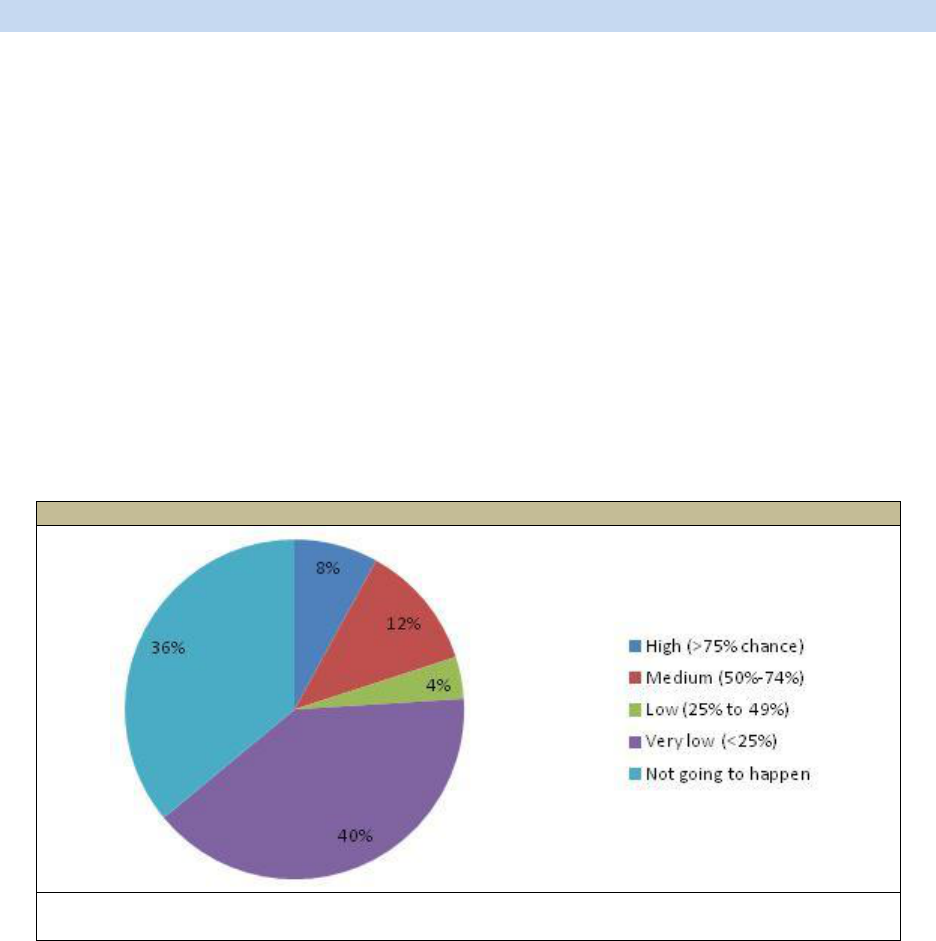

FIGURE 16. Chance that the Company would begin Selling LTC

Insurance Again ....................................................................................... 46

FIGURE 17. Circumstances under which the Company would Consider

Re-Entering the Market ............................................................................ 49

iii

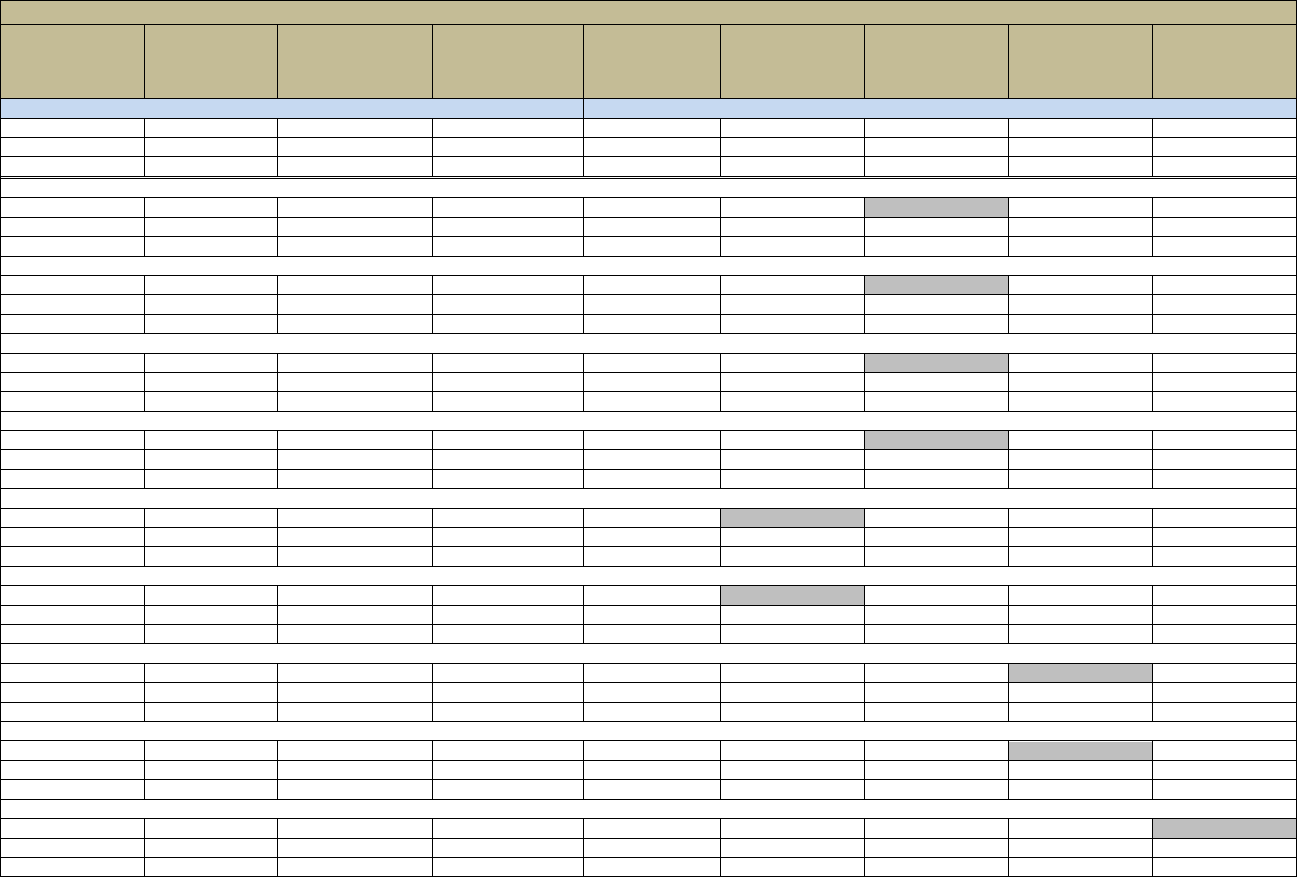

TABLE 1. Participating Companies ............................................................................... 5

TABLE 2. Characteristics of Policies Selling in the Market: 1990-2010 ...................... 13

TABLE 3. Characteristics of Individual LTC Insurance by Purchase Year .................. 21

TABLE 4. Key Pricing Assumptions in Developing LTC Insurance

Premiums ................................................................................................... 24

TABLE 5. Impact of Alternative Assumptions on Profitability of LTC

Insurance .................................................................................................... 25

TABLE 6. Distribution of Sample by Year of Market Exit ............................................ 28

TABLE 7. All of the Reasons Cited by Exiting the Market ........................................... 29

TABLE 8. Factors Influencing the Decision to Exit the Market .................................... 34

TABLE 9. Summary of Key Industry Parameters: 2000-2010 ..................................... 39

TABLE 10. Experience of 1995 Top Writers of Individual LTC Insurance in

2011 ........................................................................................................... 43

TABLE 11. Distribution of LTC Insurance Companies by Current Market

Status ......................................................................................................... 44

TABLE 12. Factors Potentially Influence the Decision to Re-Enter the Market ............. 47

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to gratefully acknowledge the partial support that we received for the

survey development, analysis, and report writing for this project from the Office of the

Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services (HHS), Washington, D.C. and specifically our Project Officer, Sam

Shipley.

We would also like to thank all of the executives from long-term care insurance and

reinsurance companies who participate in this survey and set of unstructured

discussions who shared their views in a candid and honest manner.

As well, a number of individuals both inside and outside HHS provided valuable

input and insights into earlier drafts of this paper. We would like to thank Brian Burwell,

Eileen Tell, Al Schmitz, Jodi Anatole, Malcolm Cheung, Richard Frank and the staff of

ASPE for their important contributions to this report.

Of course any and all errors in this report are the sole responsibility of the authors.

v

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s a growing number of private insurers began

providing insurance for long-term care (LTC). The market grew rapidly through the

early part of this decade. By 2003, however, growth in annual sales came to an abrupt

end and the market experienced a major decline. Whereas in 2002, there were 102

companies selling policies, by the end of the decade, there were roughly a dozen

companies still actively selling a meaningful number of policies in the market.

The sheer magnitude of the projected growth in the retiree population along with

the significant exposure to financial risk suggests that there still exists a business

opportunity for companies to provide LTC coverage. As well, there has been consistent

public policy effort in the form of state and federal tax incentives, Partnership Programs

across a growing number of states, and public awareness and education campaigns in

support of private insurance. All of this points to a strong desire on the part of public

policymakers that the private insurance market grows and prospers. Yet, this has

clearly not happened, and the question is, why not?

In this study we provide a systematic understanding of the growth and

development of the LTC insurance market with a particular focus on the reasons why

companies both entered and exited the market. We characterize the market and how it

has changed over time in terms of its size, product offerings, consumer characteristics,

regulatory framework, and financial performance. We also focus on firms’ initial

motivations for entering the market, their expectations and experience while in the

market, and ultimately why so many exited the market.

A review of industry data as well as structured interviews with executives and

decision makers from 26 major LTC insurance companies reveals the following key

selected findings:

Market Entry

About half of the companies entered the market because they believed it

represented a profitable opportunity. Others began providing the insurance to

demonstrate market leadership and to provide new products to their sales force

to keep them engaged and committed to selling the company’s other products.

More than half of companies were most concerned with the future claims risk or

the fact that the LTC risk had a “long-tail”.

Few companies were concerned with what turned out to be the two most

significant drivers of future poor financial performance -- the interest rate and

voluntary lapse rate assumptions built into the pricing of the product.

vi

During the first five years after market entry, roughly two-in-five companies

indicated that sales objectives had not been met and half indicated that either

underlying pricing objectives (25%) or initial profitability targets (25%) had not

been met.

Market Exit: Profitability Challenges

The issue of profitability is one of many factors related to why companies

entered the market but it is an absolutely central factor in understanding why

many of these same companies ultimately exited the market.

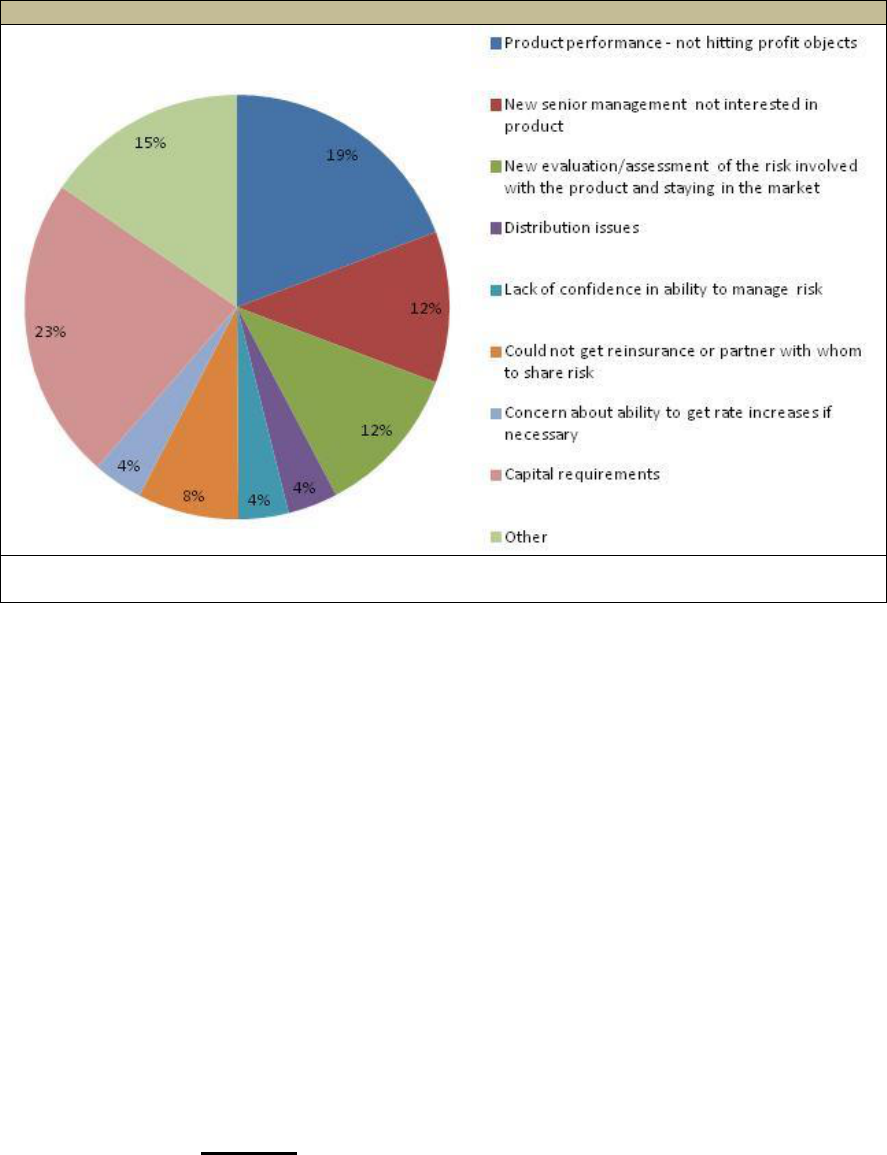

Product performance and more specifically, not hitting profit objectives was the

most cited reason for leaving the market.

High capital requirement to support the product was cited most frequently as the

single most important reason for market exit.

Other reasons for market exit related to challenges around marketing and sales,

risk management strategies, regulatory policy, and the lack of reinsurance

coverage.

The key drivers of profitability are embedded in the underlying pricing

assumptions used to develop premiums and are a function of company strategies

related to under-writing and claims management, product design, premium

structure, inflation adjustment rates, sales and marketing costs and investment

strategies.

Small variations in actual experience compared to expected performance of each

of the pricing assumptions can have a major impact on product profitability.

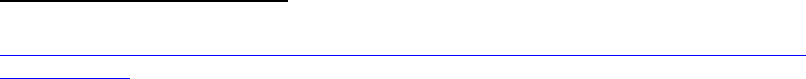

Since the late 1990s, all of these major determinants of premium and product

profitability have been going in the wrong direction: interest rates are

significantly lower than what was priced for, voluntary lapse rates are lower than

for any other insurance product, morbidity is somewhat worse than expected and

mortality is actually improving.

Regarding regulatory policy, the most cited factors having a moderate influence

on a company’s decision to exit the market have to do with the ability to obtain

rate increases in a timely manner or at all, as well as having the necessary

flexibility to engage in appropriate risk management activities.

The costs of regulatory compliance and the possibility that such compliance

encumbers product innovation were not seen as factors in the market exit

decision.

vii

Current Market Activity

Fewer than 15 companies are actively selling stand-alone LTC policies in 2012.

As of the end of 2011, policy sales for these companies were well below 1990

levels.

Market concentration has increased over the decade, with the top ten companies

now accounting for slightly more than two-thirds of covered lives and the top five

accounting for more than half of all policyholders.

Given the recent exodus of additional companies from the market, such

concentration is likely to grow.

While there has been variability in cumulative industry claims performance over

the last decade, recent data suggests that performance is deteriorating. Over the

past three years, new incurred claims are 112% higher than what was expected.

In 2010, annual premiums for companies still selling policies in the market totaled

$5.3 billion compared to $4.7 billion for those who exited the market and were

administering “closed-blocks” of business. On a cumulative premium basis,

however, closed-blocks represented 55% of all earned premiums.

By 2010, 55% of policyholders were being serviced by companies who had

exited the market.

Regarding claims, in 2010, closed-block companies represented 53% and 57%

of annual and cumulative total claims costs.

Factors that might lead Companies to Re-Enter the Market

About 42% of respondents affirmed their belief that the “door remained open” to

re-entering the market at some time in the future; however, only one-quarter

indicated that the chance was greater than 25% and the other 75% said that the

chance was very low or that it simply was not going to happen.

There were very few specific policy design changes or regulatory modifications

presented to respondents that would lead companies to definitely reconsider their

decision to exit the market.

The ability to file multiple premium schedules that would be based on alternative

levels of interest rates -- which in part helps to mitigate the investment (interest

rate) risk -- was cited most frequently as a change that would potentially lead to a

reconsideration of the decision.

viii

Expansion of combination-products to include LTC-disability, LTC-critical illness,

or others was viewed as something that might cause companies to think about

getting back into the market.

One-in-three respondents suggested that allowing policies to be funded with pre-

tax dollars also would lead them to potentially reconsider their decision.

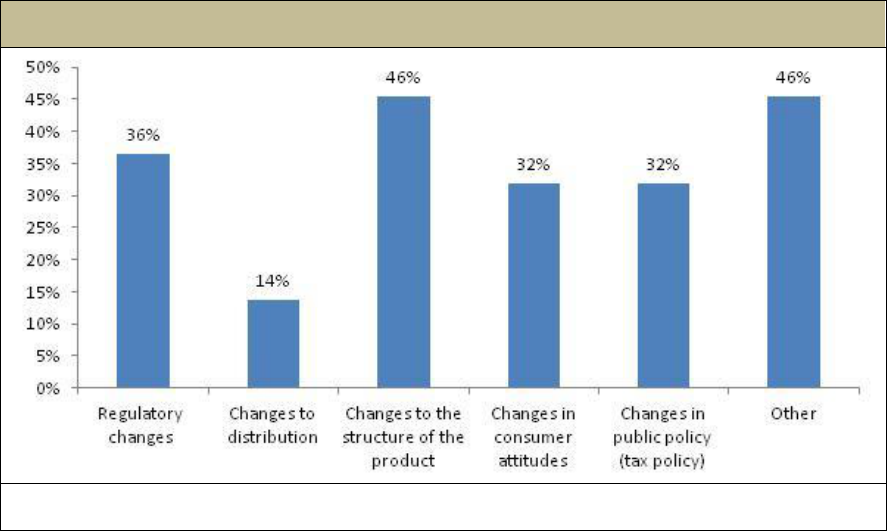

In answer to a broad question about factors that would encourage a

reconsideration of the decision to exit the market, product structure changes

were cited most often as likely to have a meaningful influence; many of these had

to do with the level-funded nature of the product, the “long-tail risk”, and the fact

that the product is complicated.

Those citing regulatory requirements pointed to high capital requirements, as well

as a general sense that carriers needed to have more flexibility in product design.

Implications

Changes to the underlying funding structure of products should be considered

with designs that are less interest rate sensitive like term-priced products and

indexation of both premiums and benefits. These approaches make the product

more affordable for consumers and reduce the level of initial reserves that must

be set up by the company, which in turn eases the amount of capital required to

support the product.

Deploying more sophisticated investment strategies designed to hedge against

the inflation and interest rate risks can also help insurers protect underlying

product profitability.

Providing companies with more certainty regarding the anticipated actions of

state insurance departments vis-à-vis requested rate adjustments is also very

important to enhancing the attractiveness of the market.

By taking some of the most risky elements out of the product, high capital

requirements would no longer be justified which would remove a major barrier to

entry and help justify the deployment of capital to support the product.

Solutions to the challenge and cost of selling the product can include linking LTC

insurance to health insurance, simplifying the product, providing more support for

employer-sponsorship of insurance, educating the public about the risk and costs

of LTC, forcing active choice, and implementing targeted subsidies.

Provision of state-based organized reinsurance pools to provide a “back-stop” for

industry experience, may also encourage more suppliers to enter the market.

ix

Conclusions

The lessons learned about pricing and managing the risks associated with LTC

insurance from those who have left the market can help set the industry on a

more solid financial foundation and make entry for new carriers a more attractive

proposition.

Identifying strategies that produce a level of profitability attractive enough to draw

capital into the market is a key to assuring a robust and competitive market of

insurers.

Public policy and regulatory approaches designed to lower the cost of policies,

allow greater product funding-flexibility, support new forms of combination-

products, and encourage strategies that help to minimize risks outside of the

control of companies, could provide needed support for a market “re-set”.

1

I. INTRODUCTION

Paying for long-term care (LTC) continues to be one of the great financial risks

facing Americans during retirement. Current estimates suggest that the annual costs of

care in a nursing home are roughly $85,000 and that home health care can cost

upwards of $25,000 per year.

1

Given that one-in-five individuals can expect to spend

more than two years in need of care, this represents a significant financial risk. In 2010,

total spending for LTC was $208 billion or roughly 8% of all personal health care

spending.

2

For the most, part such care is provided and paid for by families whereas

the largest public payer of LTC services is the means-tested Medicaid program, which

pays more than 40% of costs. Medicaid is one of the fastest growing health programs

in the country, and is creating significant budgetary pressures on the states. Private

insurance covers a small -- less than 10% -- but growing share of LTC expenses.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s a growing number of private insurers began

providing insurance for LTC, as an alternative to public coverage (i.e., Medicaid) or to

out-of-pocket payments by the elderly and their families. At first, such insurance

policies covered care provided only in a nursing home. Gradually, coverage expanded

to include payments for home care services, assisted living, adult day care, and other

community options. By the mid to late 1990s more than 100 companies were selling

policies to individuals and to individuals in group markets (i.e., employer settings).

3

Moreover, annual sales increased almost every year throughout the decade. In 1990,

380,000 individual policies were sold; by 2002, 755,000 policies were sold in that year.

4

In 2003, the pattern of annual increases in sales came to an abrupt end. In fact,

LTC policy sales began to decline rapidly. Between 2003 and 2009 individual policy

sales declined by 9% per year.

5

Thus, in 2009, fewer policies were sold than had been

sold in 1990. Moreover, while in 2002, there were 102 companies selling policies by

2009, most of these companies had exited the market; that is, they had stopped selling

new policies.

6

1

Mature Market Institute (2011). Market Survey of Long-Term Care Costs: The 2011 MetLife Market Survey of

Nursing Home, Assisted Living, Adult Day Services, and Home Care Costs. October.

2

O’Shaughnessy, CV. The Basics: National Spending for Long-Term Services and Supports. National Health

Policy Forum, 2012. http://www.nhpf.org/library/the-basics/Basics_LongTermServicesSupports_02-23-12.pdf.

Washington, DC.

3

America’s Health Insurance Plans (2004). Long-Term Care Insurance in 2002. Research Findings, Washington,

DC. June.

4

LifePlans, Inc. (2012). 2011 Long-Term Care Top Writers Survey Individual and Group Association Final Report,

Waltham, MA. March.

5

Ibid.

6

America’s Health Insurance Plans (2004). Long-Term Care Insurance in 2002. Research Findings, Washington,

DC. June.

2

The sheer magnitude of the projected growth in the retiree population -- from 12

million today to 27 million by 2050 -- along with the significant exposure to financial risk

suggests that a business opportunity exists for companies to provide LTC coverage. As

well, there has been consistent public policy support in the form of state and federal tax

incentives, Partnership Programs across a growing number of states, and public

awareness and education campaigns in support of private insurance. All of this points

to a strong desire on the part of public policymakers that the private insurance market

prospers and grows. Yet, this has clearly not happened, and in fact, the number of

companies actively selling LTC insurance continues to decline at a pace far in excess of

the small number of companies entering the market.

3

II. PURPOSE

The purpose of this study is to provide a systematic understanding of the growth

and development of the LTC insurance market with a particular focus on the reasons

why companies both entered and exited the market. We will characterize the market

and how it has changed over time in terms of its size, product offerings, consumer

characteristics, regulatory framework, and financial performance. We will also focus on

firms’ initial motivations for entering the market, their expectations and experience, and

ultimately why so many exited the market.

Specifically, we provide information on the following issues or questions:

1. What were the primary motivations and expectations of firms when they began

providing LTC insurance?

2. How has the market changed in terms of product, pricing, consumer profile,

regulatory environment, supplier characteristics, aggregate market

characteristics and performance indicators?

3. What are the primary reasons why companies who actively marketed LTC

insurance ceased selling policies?

4. What would be required for such companies to consider re-entering the market?

By addressing these issues we intend to paint a picture of the industry in terms of its

historical growth and development, as well as its current and future challenges.

4

III. METHOD AND ANALYSIS

In order to address these issues, we relied on a variety of sources of published

information as well as on new information provided by discussions with insurance

executives from 29 companies who had been in the market and chosen to exit.

A. Published Information Sources

We rely on data and information from America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP),

the Life Insurance Marketing and Research Association (LIMRA), industry analyst

reports from Moody’s and Standard & Poors, the academic research literature, and the

National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) Long-Term Care Experience

Reports for 2000, 2009, 2010 and 2011.

7,8,9,10,11

Reports from this latter source present

the most accurate information on key market parameters regarding premiums, claims,

growth of in-force business, as well as historical performance indicators like actual-to-

expected claims experience and data that enables calculation of measures of volatility

in performance. Almost all companies are required to file detailed data on an annual

basis with the NAIC, and such data is compiled and published in these annual reports.

These reports typically provide country-wide experience for companies. While the

forms are relatively consistent, there have been a number of changes in 2010. The

reports now provide additional information related to lapsation of policies but there is no

longer detailed durational loss-ratio information provided in these reports. Thus, after

2009, one can no longer track the year-by-year loss-ratio (incurred claims divided by

earned premiums) for a specific policy, based on how long that policy has been in-force.

Nevertheless, the data in these reports is extremely valuable and allows us to “size the

market” for companies still selling policies and for companies who exited the market.

An important caveat is that one of the large carriers to exit the market, Penn Treaty

Network America, is currently in rehabilitation status under the auspice of the State of

Pennsylvania. For this reason, the company was not required to provide data to the

7

National Association of Insurance Commissioners (2001). Long-Term Care Insurance Experience Reports for

2000.Kansas City, KS. November.

8

National Association of Insurance Commissioners (2010). Long-Term Care Insurance Experience Reports for

2009.Kansas City, KS. November.

9

National Association of Insurance Commissioners (2011). Long-Term Care Insurance Experience Reports for

2010.Kansas City, KS. November.

10

National Association of Insurance Commissioners (2012). Long-Term Care Insurance Experience Reports for

2011.Kansas City, KS. November.

11

While interim years were available from NAIC, in order to capture the trend over the decade, we focused

exclusively on these years.

5

NAIC in 2009 and 2010. We solicited such information directly from the company and

this allowed us to include their data with the aggregate NAIC reports.

B. Survey of Industry Executives

The second source of information was discussions with key executives who were

either directly involved in the decision making process relating to leaving the market, or

to those with intimate knowledge about their company’s decision to exit the market. The

instrument was administered in two ways: (1) in-person and telephonic interviews with

executives, and (2) a web-based survey that was sent to those individuals who did not

complete the in-person/telephonic interview. In total, executives from 29 companies

that have exited the market or exited specific market segments over the last 15 years

responded to the survey. Of these companies, three surveys were with executives from

reinsurance companies, and the other 26 from direct writers of LTC insurance. In-

person or telephonic interviews were completed with executives from16 companies and

the other 13 were completed on-line.

Executives from the following companies were interviewed and/or provided

responses to the survey.

TABLE 1. Participating Companies

Ability Re

Aetna

Allianz

American Family Mutual Insurance

Company

American Fidelity Assurance Company

CNA

Conseco

CUNA Mutual

Employers Reassurance Corp

Equitable

Great American Financial

Guardian--Berkshire

Hannover Life Reassurance Company of

America

Humana Insurance/Kanawha

John Hancock Group LTC Insurance

MetLife

Munich Re

Nationwide Financial

Penn Treaty

Physicians Mutual Insurance Company

Principal Financial Group

Prudential

RiverSource Life Insurance Company

Southern Farm Bureau Life

Standard Life and Accident Insurance

Company

Teachers Protective Mutual Life

Transamerica

a

Union Labor Life Insurance Company

UNUM

a. Note that Transamerica has since re-entered the market and the interview related to the

reasons for the initial decision to exit the market.

Based on an analysis of data for 2010 (and excluding Transamerica, which is now

back in the market), these companies represent slightly more than 95% of the total

earned premium and 90% of covered lives of companies among the top 100 of all

companies who have left the market. Thus, the results of the survey can be generalized

to the population of companies that have left the market.

6

The survey instrument itself typically resulted in an interview time of between 30

minutes to an hour. All data was captured and put into an analytic database so that

frequencies and cross-tabulations could be completed. Additional information from the

interviewees provided contextual information to many of the responses. This too is

included where appropriate. The survey results that are reported here focus exclusively

on the direct writers of LTC insurance; when appropriate, the issue of reinsurance is

addressed separately and responses from the three participating reinsurance

companies are reported.

Analytic Lens for Understanding Insurer Behavior

A primary focus of this study is to understand why firms have recently left the

market. Therefore, having a frame for understanding such behavior can be helpful in

interpreting the aggregate data as well as company-specific information. We use the

frame of “profit maximization” which posits that firms either enter a market or exit a

market depending on whether they are able to obtain a target return or profit level

commensurate with their expectations. Thus, the basic concept is that companies exist

and make decisions in order to maximize profits.

12

Clearly, the model of profit

maximization is a simplification of reality and assumes that profits are not the only

relevant goal of the firm. In fact, additional objectives may affect profits indirectly or be

equally as important such as sales maximization, public relations, gaining market share,

increasing the attractiveness of complementary products, acquiring power and prestige,

and other goals more related to managers maximizing their own utility rather than

insurer profit maximization. We do not ignore these other goals and in fact test their

validity by asking direct questions to the executives about the various motivations

underlying their decision making.

We begin by presenting information on why firms entered the market and then

present abridged summaries of key historical developments in the market focusing on

changes in product design, marketing and sales, risk management, consumer profiles,

and the regulatory framework that has developed over the past 30 years.

13

This is

followed by a discussion of why in recent years most firms have left the market. We

focus on a number of key issues affecting profitability such as pricing strategies, capital

requirements and distribution challenges. We conclude with an examination of the

factors that might influence firms to consider re-entering the market, and present some

specific actions that might encourage them do to so.

12

This theory of the firm parallels the theory of the consumer which states that consumers seek to maximize their

overall well-being (utility).

13

It is important to note that the information about firm entry to the market is based primarily on interviews with

companies that have since left the market. The exception is the presentation of some historical information on

Amex Life -- currently Genworth Financial.

7

IV. FINDINGS

A. Entering the Long-Term Care Insurance Market

LTC insurance has been selling in the marketplace for the better part of 30 years.

Early versions of the insurance were called “nursing home insurance.” This is because

such policies only covered care provided in nursing homes, primarily skilled facilities. In

the late 1970s, early 1980s there were a small number of companies providing such

coverage some of whom included Penn Treaty, Equitable, and Medico. They entered

the market at a time when expenditures on LTC were less than $20 billion which then

quickly grew to $30 billion in 1980 and over $70 billion within a decade.

14,15

Most of the

costs were borne by individuals and their families and already such care represented an

uncovered and potentially catastrophic expense. The problem of LTC financing was

recognized by policymakers who in the late 1980s debated a number of bills aimed at

paying for substantial LTC costs.

16

This occurred against the backdrop of more than 1.7

million private policies having been sold to individuals during that time.

Most of the firms providing nursing home products in the 1980s also distributed

other types of insurance. All were multi-line companies, the most prominent of which

was the Fireman’s Fund, which then became Amex Life in the late 1980s and G.E.

Capital and Genworth Financial (1990s). These early pioneers were motivated by the

perceived opportunity represented by demographic trends, but more importantly, the

sense that this coverage was not all that different from the Medicare Supplement

policies that were beginning to proliferate in the market. In some sense early nursing

home policies were viewed as a variant of such policies. This view, shaped early

approaches toward pricing, which will be discussed in a subsequent section.

We asked executives in the sample to recount why their company had initially

entered the market. Three of these companies began selling policies in the 1970s, ten

in the 1980s and almost all of the remainder in the 1990s. When these companies

entered the market most (73%) offered a nursing home-only policy -- many having

entered in the 1970s or 1980s -- and slightly more than half (57%) also offered

comprehensive policies covering both nursing home and home care services -- all

companies that entered the market in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

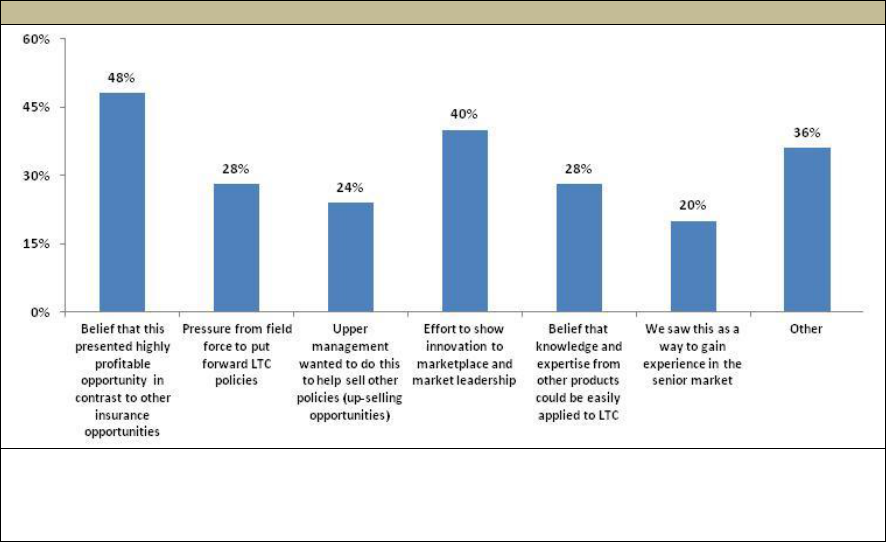

Consistent with our model of firm behavior, Figure 1 shows that almost half of the

companies entered the market because they believed it represented a profitable

14

Long-Term Care for the Elderly and Disabled (1977). Congressional Budget Office, Congress of the United

States, Washington, DC. February.

15

Health Care Financing Administration, Office of the Actuary, Data from the Office of National Health Statistics in

Health Care Financing Review, Fall 1994, Volume 16, Number 1.

16

Among others, these included the Mitchell Bill, which proposed paying for the care of individuals who stayed

more than two years in a nursing home and the Kennedy Bill which proposed paying for front-end LTC costs.

8

opportunity. However, profit maximization was not the only reason for entering this

market. Many companies felt that such a strategy supported efforts to show market

leadership and to provide new product to their sales force to keep them engaged and

committed to selling the company’s other products. During detailed discussions with

respondents, it was clear that compelling demographics and a perception of increasing

consumer need drove many companies to enter this market to take advantage of an

opportunity that they knew existed, even if they were not completely certain about how

to exploit it profitably. Not shown in the figure is the fact that among these companies

who left the market, 80% had senior management that was either supportive or very

supportive of the decision to initially enter the marketplace.

FIGURE 1. Primary Motivations for Entering the Market

SOURCE: Survey of executives from 26 LTC carriers who exited the market or exited segment of

the market.

NOTE: Numbers sum to more than 100% because respondents could check more than a single

motivation.

Even 30 years later, the need for a product addressing the catastrophic costs

associated with LTC needs persists. The consequence of demographic trends, a lack of

comprehensive public solutions, and an inadequate private market is that LTC remains

the largest unfunded health-related liability faced by elders during retirement. While

demographics and consumer need have remained constant over the period,

perceptions about the actual profit opportunity presented by this market have definitely

changed.

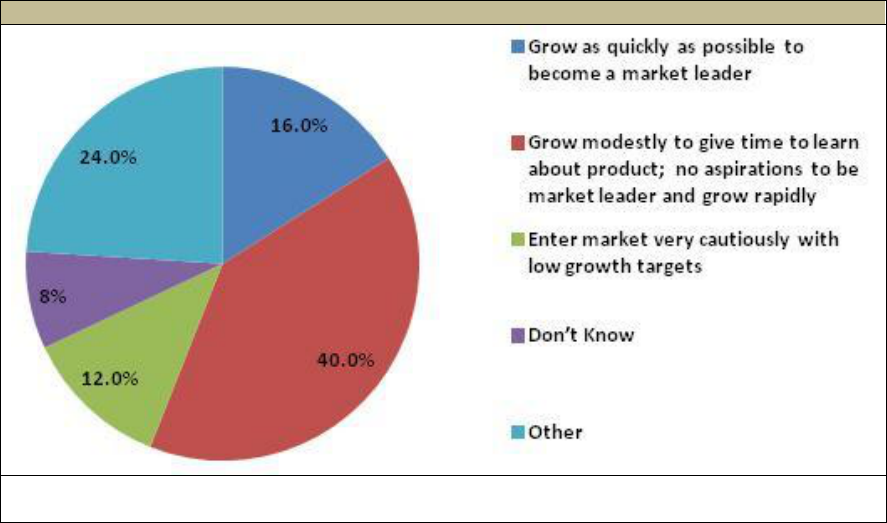

Figure 2 highlights the initial business strategy of companies and demonstrates

that for 40% of the companies that left the market, their initial business strategy was to

grow modestly in order to learn the business and improve their management of the

product over time. Only 16% had aspirations of becoming market leaders.

9

FIGURE 2. Initial Business Strategy

SOURCE: Survey of executives from 26 LTC carriers who exited the market or exited segment of

the market.

We also asked which business metric was viewed as the most important to

measuring the success of the endeavor during the first five years after market entry.

Slightly less than half (48%) of companies indicated that meeting sales targets was

most important. Profitability and meeting underlying pricing assumptions during the first

few years of sales were cited by fewer than 25% of respondents; this suggests that

there was a realistic understanding that given the long-term nature of the underlying

risk, as well as the relatively high initial costs associated with selling and underwriting

new policies, profit emergence and credible actuarial experience would be relatively

slow in developing. The first measurable goal would be sales.

Most companies tried to differentiate themselves from their competitors through

innovative product design as well as sales incentive plans. Some of the innovation

proved to be confusing for consumers, and in particular, competition related to the

benefit eligibility trigger. Some companies made eligibility for benefits dependant on the

ability to perform varying numbers of activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental

activities of daily living. It was nearly impossible for an individual to know which set of

conditions they were likely to meet 20 years into the future to qualify for insurance

payments. Benefit trigger standardization did not occur until the passage of the Health

Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. Companies also

expanded coverage for more community services including caregiver support and

respite care, restoration of benefits, transportation services, and other ancillary benefits.

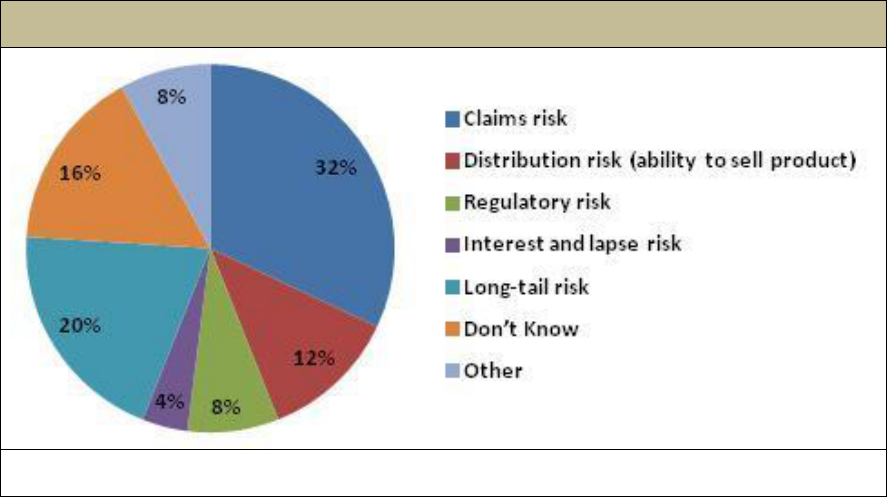

Figure 3 shows how companies evaluated the key risks associated with this

product. More than half of companies were most concerned with the future claims risk

or the fact that this risk had a “long-tail”. In other words, they were not certain how long

an individual with LTC needs would require paid services. A relatively high percentage

10

of policies had lifetime or uncapped benefit durations, which meant that they would pay

benefits for as long as someone had continued need -- which represented an uncapped

liability to the company.

FIGURE 3. Evaluation of Most Volatile or Greatest “Potential Future Challenge”

at the Time of Market Entry

SOURCE: Survey of executives from 25 LTC carriers who exited the market or exited segment of

the market.

It is somewhat ironic that few companies were concerned with what turned out to

be the two most significant drivers of future poor financial performance -- the interest

rate and voluntary lapse rate assumptions built into the product. Lower than expected

interest rates and voluntary lapse rates have forced almost all companies to seek rate

increases, and this may have contributed negatively to sales as well as to the reputation

of both the product and to a number of companies. As will be demonstrated in a

subsequent section, errors in these assumptions had a major negative impact on

product profitability.

We also asked companies which objectives were not met during the first five years

of market entry. Roughly two-in-five indicated that sales objectives had not been met

and half indicated that either underlying pricing objectives (25%) or initial profitability

targets (25%) had not been met. Thus, fairly early on, for a clear majority of these

companies, the key metrics established to judge whether the initial decision to enter the

market had been a good one, were not being met. Moreover, early undefined goals

may have led to later disappointments.

Since the time when most firms entered the market, the industry has experienced

a number of major changes, many of them directly and indirectly contributing to the

current picture of the industry. These include changes in product, risk management

strategy, sales approaches, and the regulatory and public policy environment. We

summarize these key trends in order to provide an historical view of industry

developments through the first decade of this century.

11

B. Market Evolution

1. Product Design

As mentioned, LTC insurance -- nursing home insurance -- has been selling in the

marketplace for the better part of 30 years. Thus, it may still be considered a relatively

new insurance product that continues to evolve. The implication is that one might

reasonably expect “wrong turns” along the way, as the product and industry adapts to

new information, changing market conditions, and accumulated actuarial experience.

Through the 1970s and up to the late 1980s, the coverage was linked to the structure of

Medicare coverage. Like many supplemental private health insurance policies, nursing

home insurance focused on what Medicare “did not cover”. Medicare paid for skilled

nursing home care for up to 100 days and private insurance began coverage when

Medicare ceased providing benefits. For this reason, early product configurations had

elimination periods (i.e., deductibles) that were typically defined as 100 days -- the

period of care that Medicare covered -- and the coverage was focused exclusively on

skilled nursing home care resulting from a prior three day hospitalization -- precisely in

line with Medicare policy. If care was initially considered to be “medically necessary”,

private insurance carriers would continue to pay benefits even when the need for skilled

care ceased and only custodial (i.e., maintenance) care was required. Thus, while

these early private policies “keyed off” of Medicare coverage, their innovation was that

they paid for custodial care, where Medicare did not. In essence, this extended

coverage from a limited amount of skilled nursing care (paid by Medicare) to a much

more generous amount of skilled and custodial nursing home care (paid by private

insurance and also by Medicaid for selected populations).

Early Medicaid policy also shaped the conception of LTC as synonymous with

nursing home care.

17

Over time, LTC -- and now long-term services and supports -- has

come to reflect the reality that the need for care, which is based on functional limitations

and/or cognitive impairment, requires a broader set of service responses. These

include home and community-based care and a variety of residential care settings such

as assisted living, adult day care and others.

Regarding the pricing of early policies, there was little basis on which to develop

an estimate for future morbidity (i.e., the chance that someone would develop a

condition that required use of LTC services) in the context of private insurance. In order

to price these early policies actuaries relied on national data sources like the 1977 and

1985 National Nursing Home Surveys. As they considered home care coverage, they

focused on the 1982, 1984, and 1994 National Long-Term Care Surveys for incidence

and continuance data; again, such data was not directly transferrable to the private

insurance context since it was neither insured data nor was the underlying population

17

Kemper, Peter (2010). Long-Term Services and Supports. The Basics: National Spending for Long-Term

Services and Supports. Presentation to the National Health Policy Forum, Washington, DC. June 18.

12

likely to reflect purchasers of insurance. For other pricing parameters, like voluntary

lapse rates and mortality, there was a reliance on the experience of Medicare

Supplement policies and standard mortality tables. For this reason, voluntary lapse

rates priced into initial policies were much higher than what they ultimately turned out to

be. (In fact, there is no other voluntary insurance product in the market that has

experienced lower voluntary lapse rates than what is found in LTC insurance policies.)

Policies were always sold as guaranteed renewable -- they could only be cancelled

for non-payment of premium -- and as level-funded. That is, while the premium charged

varied by age at purchase, once an individual purchased a policy, the premium was

designed to be level for life. Theoretically, an individual buying a policy at age 65 for a

premium of $1,000 per year could be expected to pay that same annual premium

throughout their lifetime, so long as the underlying pricing assumptions employed by the

actuaries were accurate. The level-funded nature of the product persists to this day,

and poses unique challenges to insurers. This will be discussed in a subsequent

section. Finally, almost all policies reimbursed the actual costs of care up to a daily

benefit maximum.

Relatively sluggish sales of LTC insurance policies in the 1980s suggested that the

then current product design was not going to reach a broader part of the public. Selling

insurance to cover something that no one wanted to access, except under the most

extreme of circumstances, did not seem to be an attractive value proposition for fueling

growth in the market. Moreover, Medicare, as well as certain Medicaid plans under

special waivers, began to pay for support services in peoples’ homes. Medicare

covered such services primarily when they were deemed to be medically necessary.

Medicaid also expanded its coverage for home and community-based care but still

severely restricted access to these services.

As agents and brokers came to play a larger role in the LTC product development

process, it was clear that for the coverage to sell, it needed to pay for custodial services

where people desired them most -- in their own homes. This presented a dilemma for

insurers because the primary risk management tool for managing claims was based on

policyholder behavior: no policyholder really wanted to go into a nursing home, and this

served as a brake on potential moral hazard and over-utilization of services. If policies

began covering services in settings that people desired, like the home, this “brake” on

moral hazard would disappear with the potential for making the underlying economics of

the product unsustainable.

It became clear that in order for the market to grow, the product would have to

cover home and community-based services in a manner that enabled insurers to

effectively manage what were viewed to be the primary risks of the product: adverse

selection and moral hazard. This was accomplished in part by changing the basis on

which benefits were paid from a medical necessity model to a functional and cognitive

impairment model. There had been a growing realization, encouraged by professionals

with geriatric experience who entered the industry or consulted with it, that measures of

13

functional abilities were most closely related to the need for covered services --

including home care.

In the mid to late 1980s and early 1990s, carriers began to provide limited

coverage for home and community-based care -- either through riders or as part of the

underlying basic policy design. They felt comfortable doing so because access to

insurance benefits was made contingent on an insureds inability to perform a certain

number of ADLs or the need for assistance due to a severe cognitive impairment.

These were more easily measurable and predictable benefit eligibility criteria. Also, a

number of third party assessment companies entered the market to assist insurers in

evaluating whether such deficits existed. It is not surprising, therefore, that consumer

demand, coupled with the sense that companies could manage the underlying risk,

fueled rapid growth in market share of comprehensive policies. This is clearly displayed

in Table 2, which highlights the changes in product design over the past 20 years.

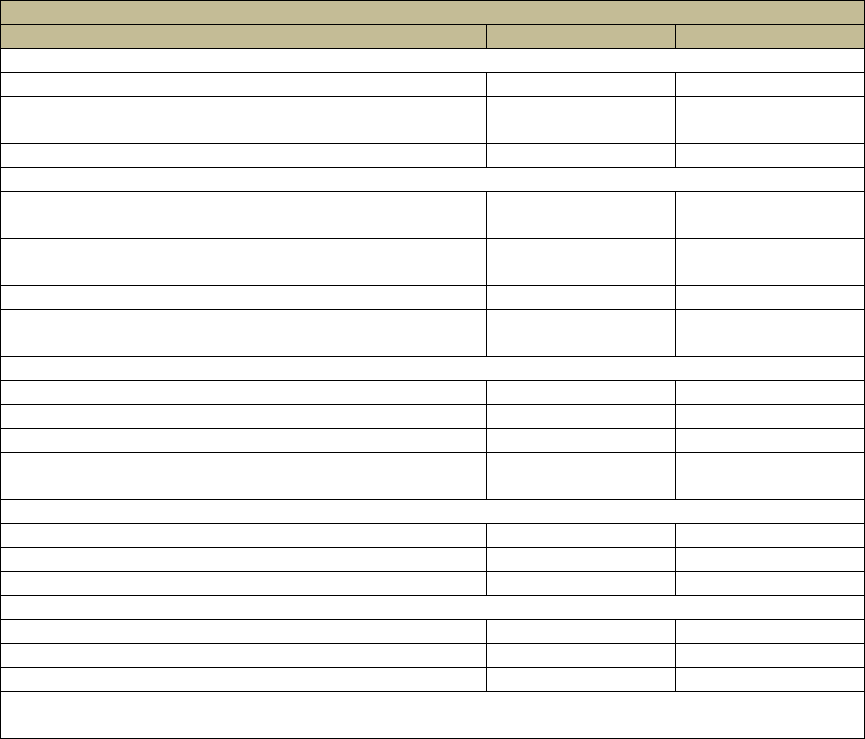

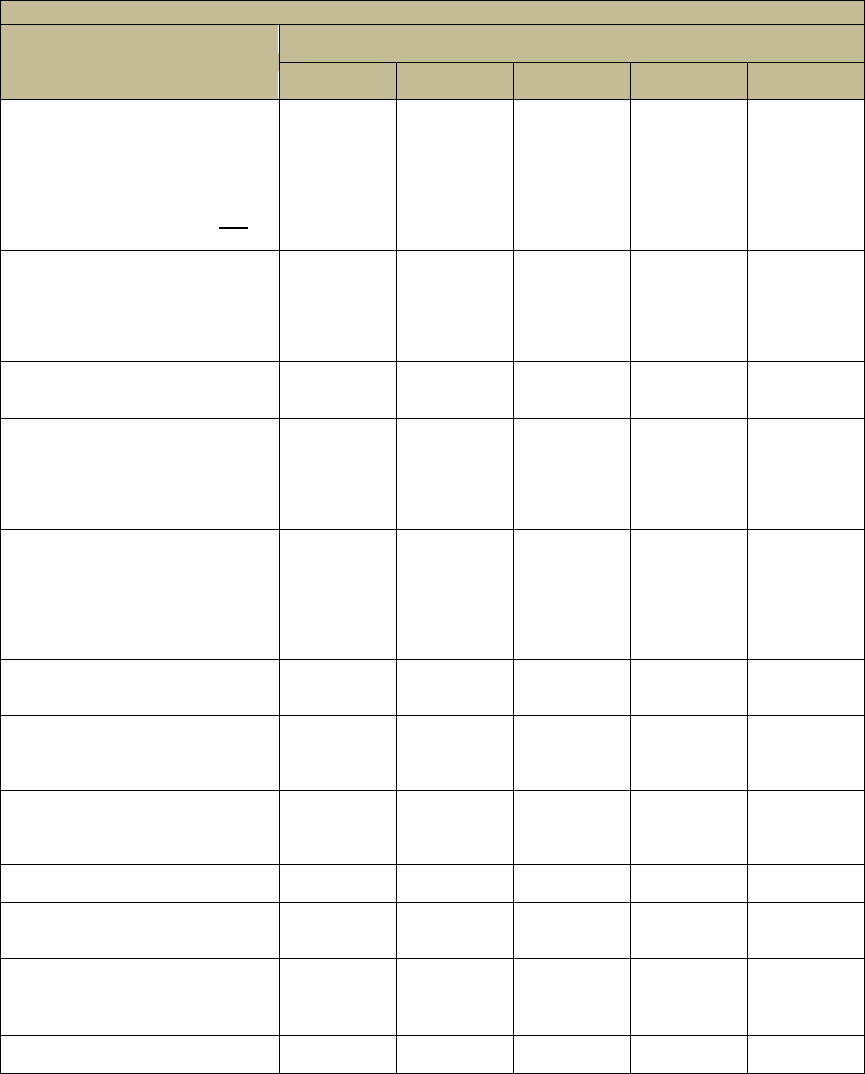

TABLE 2. Characteristics of Policies Selling in the Market: 1990-2010

Policy Characteristics

Average

for 1990

Average

for 1995

Average

for 2000

Average

for 2005

Average

for 2010

Policy Type

Nursing Home-Only

63%

33%

14%

3%

1%

Nursing Home & Home

Care

37%

61%

77%

90%

95%

Home Care Only

---

6%

9%

7%

4%

Daily Benefit Amount for

Nursing Home Care

$72

$85

$109

$142

$153

Daily Benefit Amount for

Home Care

$36

$78

$106

$135

$152

Nursing Home-Only

Deductible Period

20 days

59 days

65 days

80 days

85 days

Integrated Policy

Deductible Period

---

46 days

47 days

81 days

90 days

Nursing Home Benefit

Duration

5.6 years

5.1 years

5.5 years

5.4 years

4.8 years

Inflation Protection

40%

33%

41%

76%

74%

Annual Premium

$1,071

$1,505

$1,677

$1,918

$2,283

SOURCE: LifePlans analysis of 8,099 policies sold in 2010, 8,208 policies sold in 2005, 5,407 policies

sold in 2000, 6,446 policies sold in 1995 and 14,400 policies in 1990. Reported in: Who Buys Long-Term

Care Insurance in 2010-2011? A Twenty-Year Study of Buyers and Non-Buyers (in the Individual Market),

AHIP, 2012.

Coverage limited to nursing home or institutional alternatives only has virtually

disappeared from the market. Deductible periods have increased and are roughly equal

to three months of care. Moreover, the percentage of individuals purchasing some level

of protection for increasing LTC costs is about three-in-four with roughly half buying

compound inflation protection.

The average daily nursing home benefit has increased significantly over the period

-- by an annual rate of roughly 4%. Given the mix of home care and nursing home

service use, this is roughly in line with the rate of inflation in these services over the

period; the $153 daily benefit amount in 2010 would cover 70% of the average daily

cost of nursing home, 155% of the daily cost of assisted living, and roughly eight hours

14

of home care a day seven days a week.

18

Over the period, there has been a decline in

the number of policies with unlimited benefits, a particularly risky policy design, given

the uncapped liability faced by the insurer. The desire of companies to move away from

this policy design stems in part from pressure by ratings agencies and fewer

reinsurance options.

19

It represents one of a number of actions insurers have taken to

“de-risk” the product.

Finally, annual premiums have increased significantly over the period, as policy

value has increased and as insurers have a body of credible experience on which to

make changes to a number of key underlying pricing assumptions. Clearly new policies

reflect a more conservative set of pricing assumptions, especially with respect to

interest rates and voluntary lapses. This will be discussed in more detail in a

subsequent section.

2. Marketing and Sales

Like other types of insurance, LTC insurance is sold in a variety of ways and

through a number of distribution channels. Most policies are sold by agents and

brokers directly to individuals. The distribution channel which is growing the most

quickly, however, is the employer group market. Here agents are able to market and

sell group policies to a large number of individuals, each of whom receives an individual

certificate of insurance under a group plan. In 2000, new individual sales accounted for

75% of the market and group sales -- primarily employer-sponsored -- represented only

25% of new sales. By 2010, new individual sales had fallen to 58% of the market and

group channels comprised 42% of new sales.

20,21

While most agents are independent -- this indicating that they can represent and

sell policies from a variety of insurers -- a number of companies do have what are called

“captive agents”. In these companies agents can only sell that company’s specific

policy. Only a very few companies have specialist LTC agents, whose sole focus is

selling LTC insurance policies. Currently there are fewer than 10,000 agents selling any

meaningful number of policies.

Commissions for LTC insurance tend to be “heaped”. This means that first-year

commissions relative to premiums are high -- 40%-60% of premium with some

companies approaching 100% -- and then they tend to drop down to between 5% and

18

Market Survey of Long-Term Care Costs (2010). The 2010 MetLife Market Survey of Nursing Home, Assisted

Living, Adult Day Services, and Home Care Costs. MetLife Mature Market Institute.

19

Moody’s: Long-Term Care Insurers Face Uncertain Future (2012). Moody’s Investor Service, Global Credit

Research, New York, NY. September 19.

20

Cohen, M. (2011). Financing Long-Term Care: The Private Insurance Market. Presentation to the National

Health Policy Forum, Washington, DC. April 15.

21

It is important to note that a number of companies exiting the market have transferred their group business to

other carriers and in some cases this may be counted as a “sale”, even if individuals purchased their coverage years

beforehand. Thus, some of the 42% of new sales could have been comprised of such takeover activity, which was

particularly prevalent in 2010-2012.

15

15% of ongoing renewal premiums.

22

This compensation structure does cause

significant first-year cash flow challenges for companies. Moreover, it delays the timing

of profit emergence as companies may be in a loss position for the first year after a

policy is sold.

The 1990s were characterized by companies competing for the allegiance of large

distribution forces by paying higher commissions to attract and encourage them to

represent and sell their, rather than competitors’, policies. This led to a situation where

the costs of the product increased and market share shifted rapidly between companies

as agent groups focused on selling the product that paid the highest commissions. The

higher commissions did not appear to draw enough new agents into the market to

effectively increase overall market size significantly over the past decade.

It is often said by industry participants that LTC insurance is not “bought” by

consumers, but rather, it is “sold” to consumers. Challenges related to individuals’ lack

of understanding about future risk, an incorrect belief that government will pay for LTC,

confusion about products, belief that other products already address the risk, its cost in

relation to the value that people believe it has, and a lack of belief in the underlying

value proposition have all contributed to the overall challenge of growing the market.

23,24

Even in the presence of such challenges, however, two-thirds of surveyed individuals

from the general population age 50 and over in 2010 indicated that they were aware of

companies that offer this insurance, and about 40% had been approached or had

considered purchasing it.

25

It often takes agents 2-3 visits to close a sale. Still agents are critical in the

process and are viewed very positively by buyers; in a study of buyers in 2000, more

than 90% reported that the agent they had dealt with was knowledgeable, explained the

product well, and helped them select a policy that met their needs. Moreover, after a

spouse, agents were seen to be the most important in individuals’ decision to purchase

a policy.

26

In terms of overall sales and market penetration, the first half of the 1990s

represented the fastest growth over the 20 year period and coincided with the

proliferation of policies covering home care and nursing home care. The precipitous

22

Note that for life insurance first-year commissions are commonly above 100% and the dollar value of annuity

commissions is often greater than the value of LTC commissions. Thus, LTC commissions are not out of line with

other voluntary insurance products.

23

Stevenson, D., Cohen, M., Tell, E. and Burwell, B. (2010). The Complementarity of Public And Private Long-

Term Care Coverage. Health Affairs, 29:1. January.

24

Brown, J.R., Coe, N.B., and Finkelstein, A. (2007). Medicaid Crowd-Out of Private Long-Term Care Insurance

Demand: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Survey. In J.M. Poterba, Ed., Tax Policy and the Economy, Vol.

21, pp.1-34.

25

Based on analysis of 500 individuals age 50 and over surveyed in 2010, 2005, and 2000 as well as 1,000

individuals age 55 and over surveyed in 1995 as reported in Who Buys Long-Term Care Insurance in 2010-2011? A

Twenty-Year Study of Buyers and Non-Buyers (in the Individual Market), AHIP, 2012.

26

Long-Term Care Insurance 2000: A Decade of Study of Buyers and Non-Buyers. The Health Insurance

Association of America, July 2000.

16

decline in sales in the early part of this century coincides with a growing number of

companies exiting the market, the general declines in the stock market which affected

demand, and the significant price increases in new policies offered by insurers.

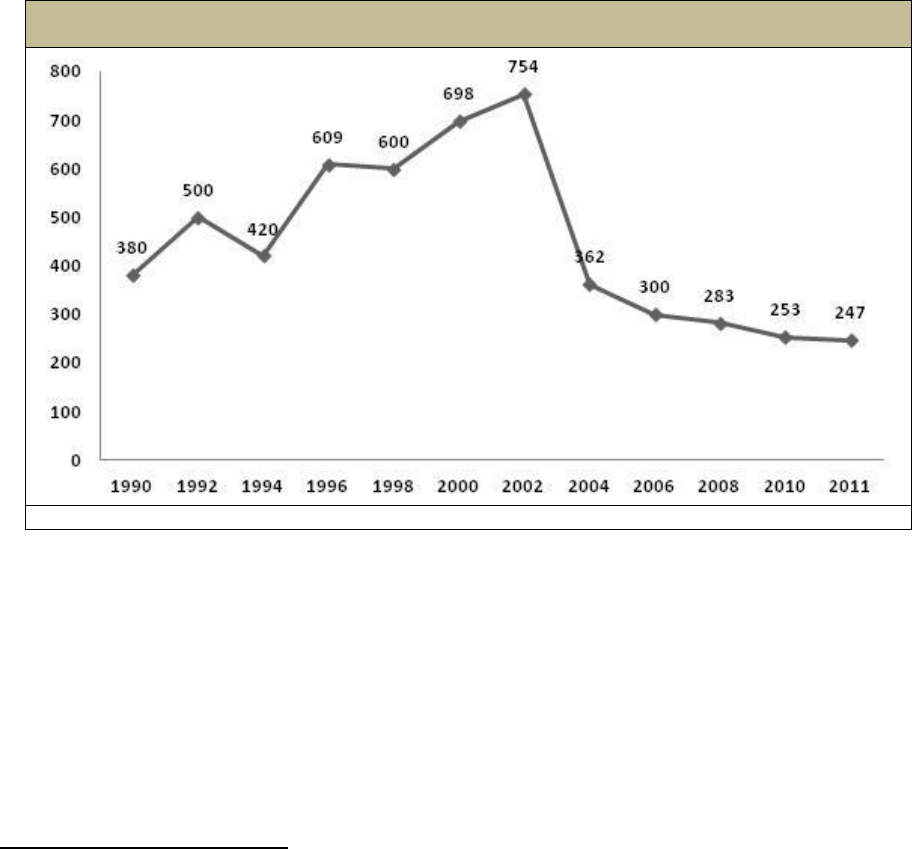

Figure 4 shows sales patterns for new individual policies over the past 20 years.

27

FIGURE 4. New Sales of Individual Policies

(thousands)

SOURCE: LifePlans analysis based on AHIP, LIMRA and LifePlans sales surveys, 2011.

Clearly, as policies became more attractive to consumers in the 1990s, the market

grew significantly both in terms of covered lives and insurance premium. It is also worth

noting that during the 1990s, there were minimal changes in the underlying pricing

assumptions of policies. In fact, between 1990 and 2000, the average value in policies

-- as measured by changes in average value of policy benefits -- increased more quickly

than the average premium during the period.

28

This trend foreshadowed a later criticism

and concern with LTC policies expressed by ratings agencies that early designs of

policies offered benefits that were too generous relative to factors like actual benefit

utilization.

29,30

27

Note that the decline in sales in 1994 coincided with the Clinton health care reform debates which included

provisions for expanded home and community-based care. This was seen to depress demand as potential buyers

waited to see whether or not the legislation would pass.

28

Authors calculations based on policy design data from more than 10,000 policies in 1990, 1995 and 2000 as

reported in Who Buys Long-Term Care Insurance in 1994? Profiles and Innovations in a Dynamic Market (2005).

Health Insurance Association of America, Washington, DC, and Who Buys Long-Term Care Insurance in 2005? A

Fifteen Year Study of Buyers and Non-Buyers (2006). America’s Health Insurance Plans, Washington, DC.

29

Bazer, L. (2012). An Outsiders View: The State of the LTCI Industry--Long Term Care from a Rating Agency

Perspective. Presentation at the 12th Annual Intercompany Long Term Care Insurance Conference, Las Vegas,

March. Moody’s: Long-Term Care Insurers Face Uncertain Future (2012). Moody’s Investor Service, Global

Credit Research, New York. September 19.

17

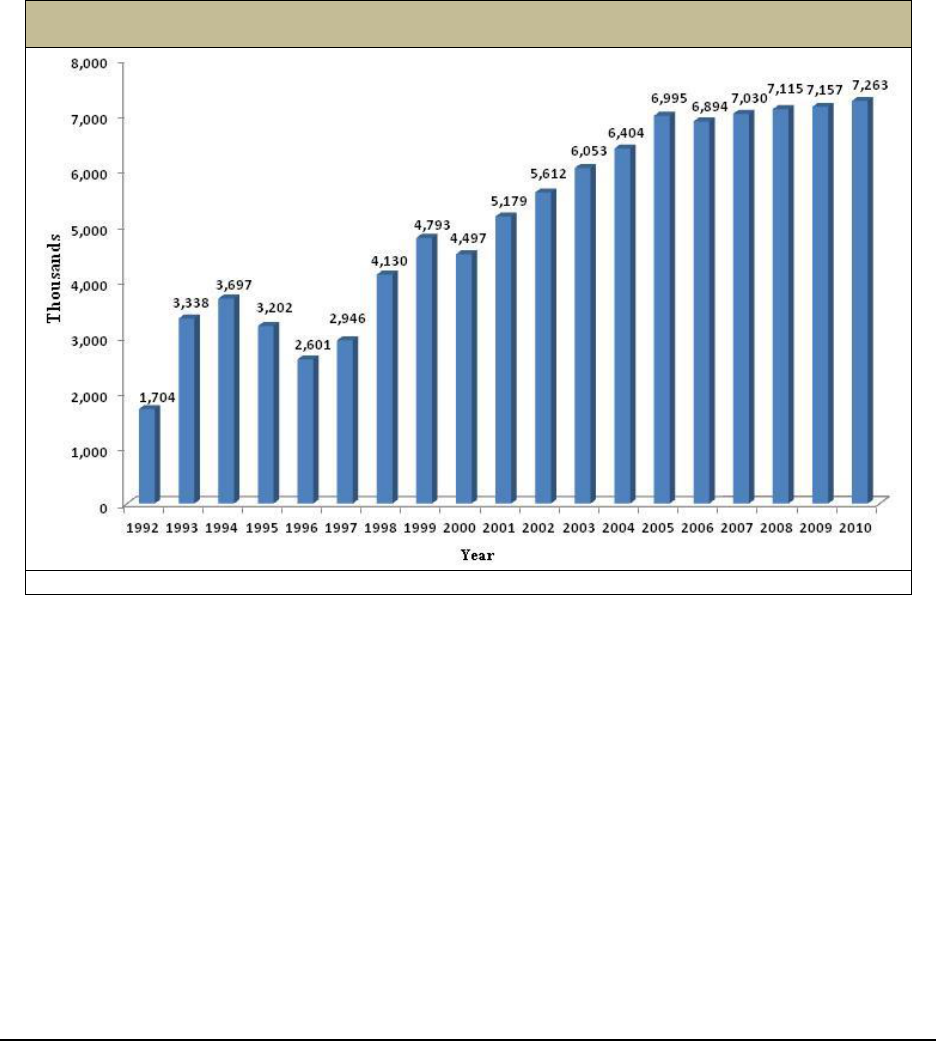

Figure 5 shows that in 2010, the total number of individuals with LTC insurance

coverage was 7.3 million. This does not represent all people who have ever had

policies, only those who still have them. Changes in covered lives reflect both growth in

annual sales as well as changes in the number of policyholders who maintain their

coverage over time.

FIGURE 5. Number of Insured Lives Covered by Year

(thousands)

SOURCE: NAIC Experience Reports, 2011.

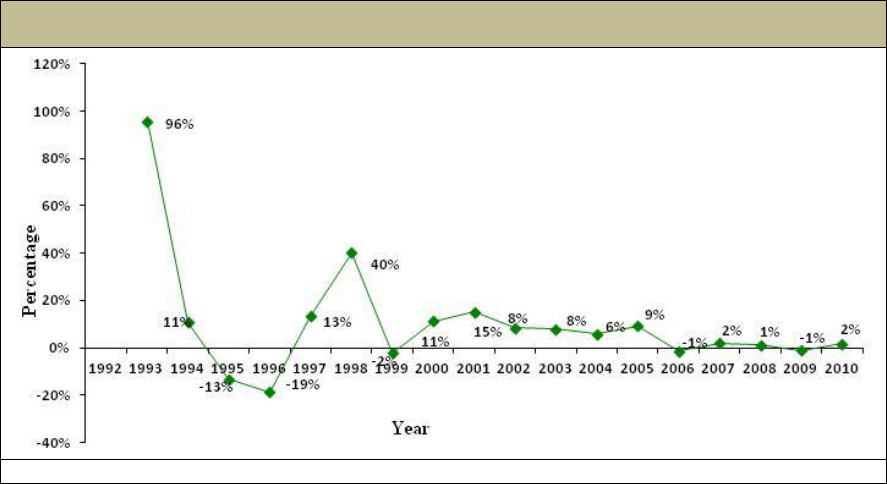

Figure 6 shows the annual change in covered lives over the period. As shown,

between 1992 and 2000 there was tremendous variation in the growth rate of covered

lives and after 2003, there has been a relatively steady yet small annual increase in

covered lives. Given the aging of the individuals with policies, this suggests that the

growth in sales throughout the decade has declined or been relatively flat.

30 Meyer, D. (2012). Why Get in? Why Get out? Ratings Agency Perspective on Long-Term Care. Fitch

Ratings, presentation at the 12th Annual Intercompany Long Term Care Insurance Conference, Las Vegas, March.

18

FIGURE 6. Annual Growth in Total Covered Lives

(thousands)

SOURCE: LifePlans analysis of NAIC data, 2010.

3. Risk Management

For first generation policies sold in the 1970s and 1980s, insurers were convinced

that because nursing homes were viewed as places of last resort to receive care, there

would be little moral hazard because it was well known that most people viewed nursing

home residency as a “dreaded event”. Not surprisingly, little attention was paid to

underwriting and claims management for these early policies. So long as an applicant

was not already in a nursing home, they could apply for coverage and would likely be

issued a policy. Given that the average age of new buyers at the time was 68, most

carriers still expected to see significant claims activity only 10-15 years in the future.

As companies began to market and sell comprehensive coverage they well

understood that the aversion to using nursing homes was no longer an impediment to

moral hazard; hence, companies felt a need to invest in more robust approaches to

managing the two primary risks associated with product performance that were

completely under their control: underwriting to guard against adverse selection, and

claims management, to protect against moral hazard.

In the early 1990s, insurers began to employ more vigorous approaches to the

underwriting of policies; these approaches focused on two broad dimensions: (1)

medical criteria; and (2) tools and requirements gathering. Regarding medical criteria,

the three domains on which companies focused their attention were the medical,

functional, and cognitive status of individuals. Risk managers tried to better identify

factors that put the individual at immediate or near term need for the services that were

being insured for, namely, human assistance required to compensate for an individual’s

inability to perform ADLs due to functional deficits or to cognitive issues. Diagnoses

were viewed as markers for current or future manifestations of functional need. Data

mining, as well as more comprehensive reviews of the medical literature resulted in the

19

development of detailed medical underwriting guides by companies. The information in

these guides was considered proprietary, since the ability to perform more effective risk

selection was seen as a competitive advantage for a company. At the same time,

cognitive testing was adopted in the early 1990s and became a standard business

practice. The availability of third party assessment companies serving the industry

significantly enhanced the ability of insurers to perform their risk management functions

both for underwriting and for claims management.

Companies also invested in more robust information gathering. The most common

tools included information provided from the application, telephone interviews, medical

records or attending physician statements, medical exams, in-person assessments and

pharmacy databases. Many of these tools are in use today. An analysis of underwriting

practices across the industry suggested that over the last decade, as companies have

been able to link their up-front underwriting strategies with back-end claims experience,

there has been a marked shift toward more conservative underwriting practices.

31

In

2009, underwriting rejection rates across the industry were at 19.4%. For applicants

under age 45, declination rates are below 10% whereas for those over age 80, rates

increase to more than two-in-five.

32

Regarding claims, insurers focused on managing three major types of risks

associated with a claim: (1) the incidence risk, which is the risk that someone becomes

disabled and requires LTC services covered by the policy; (2) the intensity risk, which

focuses on the level of service and associated expenditure required to compensate for

the individual’s functional or cognitive deficits; and (3) the continuance risk, the amount

of time that an individual would require paid services. Companies typically deploy --

through third party vendors -- nurses into the homes of claimants to measure whether

the benefit eligibility trigger has been met and these same nurses are also involved in

the development of care plans. These benefit assessments are fairly standard across

the industry, especially when someone is claiming home care or assisted living benefits.

For nursing home care, many companies rely on nursing notes or the Minimum

Dataset Survey to obtain the information necessary to adjudicate a claim. The latter is

an assessment that must be completed on all nursing home residents. Companies also

conduct regular follow-up with claimants to assure that they remain eligible for benefits

under the terms of the insurance contract. Over the last decade insurers have invested

significant resources into claims management systems and are far more active in terms

of helping claimants navigate the LTC system and get services in place.

33

31

Tolerating Risk: A Look at LTC Underwriting Strategies. Behind the Data, Issue 2, January 2011. LifePlans,

Inc., Waltham, MA.

32

Ibid.

33

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy (2008).

Private Long-Term Care Insurance: Following an Admission Cohort over 28 Months to Track Claim Experience,

Service Use and Transitions. Final Report. Washington, DC. April.

http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2008/coht28mo.htm.

20

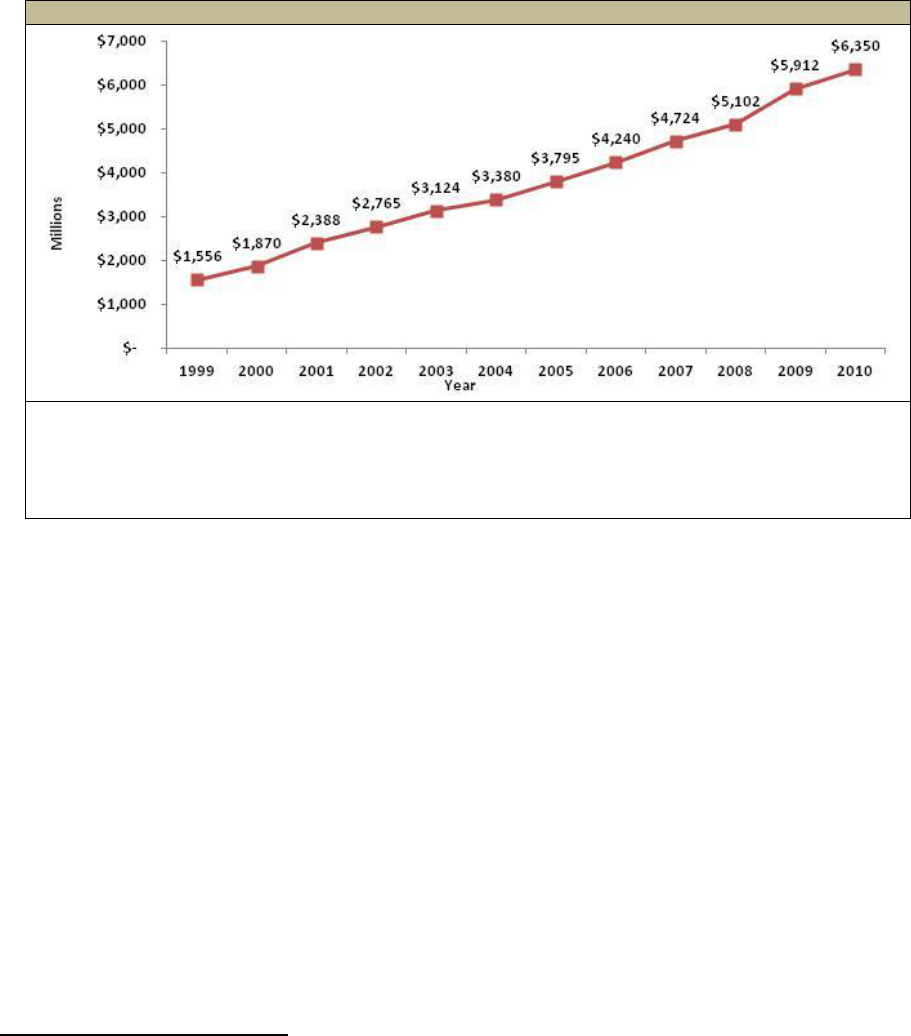

This investment is clearly warranted given the rapid growth in claims payments.

Figure 7 shows the growth in new claims over the period. The average growth in

annual incurred claims over the period is 13%. Although not shown in the figure,

through 2010, companies reported paying out on a cumulative basis over the last two

decades slightly less than $50 billion in incurred claims; on an annual basis, the liability

covered from private LTC insurance is roughly $6 billion, which is less than 5% of total

expenditures on LTC services in the United States.

FIGURE 7. Industry-Wide Actual Annualized Incurred Claims

SOURCE: NAIC Experience Reports, 2011.

NOTE: The growth in incurred claims in and of itself does not translate to underlying profitability

or performance for the industry, nor does its relationship to changes in earned premiums (which

are not shown in Figure 4) relate directly to profitability. Profitability is related in part to the actual

relationship between claims and premiums over the life of a policy.

4. Consumers of Long-Term Care Insurance

Roughly seven million individuals have a LTC insurance policy. The LTC

Financing Strategy Group estimated that penetration among individuals who are

considered to be suitable purchasers (i.e., have incomes in excess of $20,000 and are

not currently eligible for Medicaid) is 16% of the over age 65 group and about 5% of the

age 45-64 age group.

34

The profile of individuals purchasing LTC insurance has

changed dramatically over the last 20 years. As products have become more

comprehensive and costly, the proportion of middle income buyers of insurance has

declined. Table 3 summarizes key characteristics of buyers in the individual market.

The average age of buyers continues to decline, and most purchasers are working,

married college-educated and have significant levels of income and assets. In the

group market, the average age is roughly 46 years. Not shown in the table is the fact

that most people purchase the insurance to protect current consumption patterns (e.g.,

34

LTC Financing Strategy Group, 2008. Washington, DC.

21

maintain standard of living, avoid dependence, maintain affordability of services) rather

than to protect assets.

35

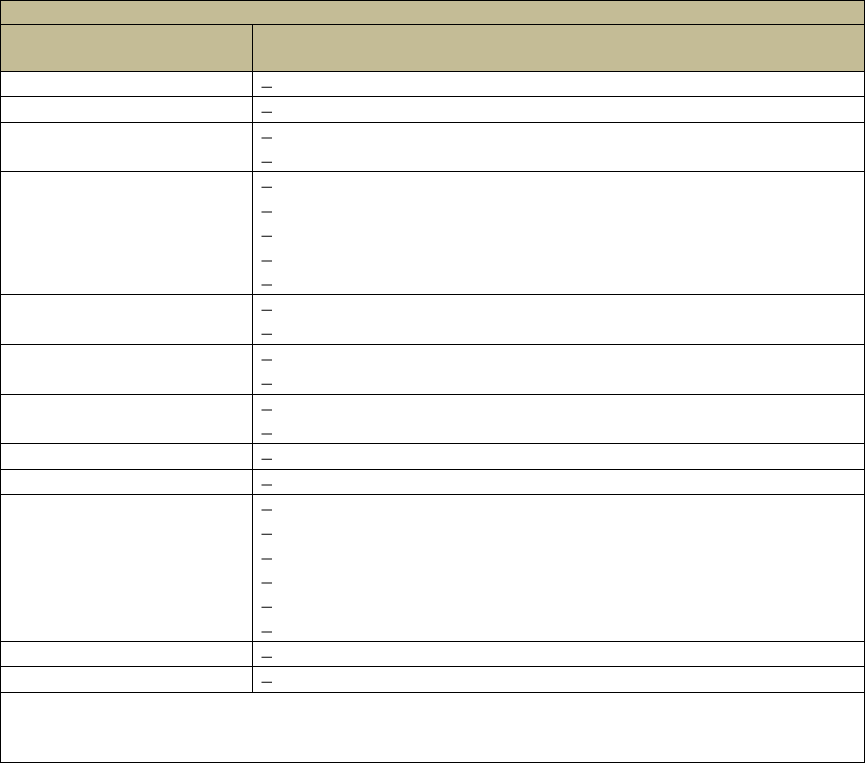

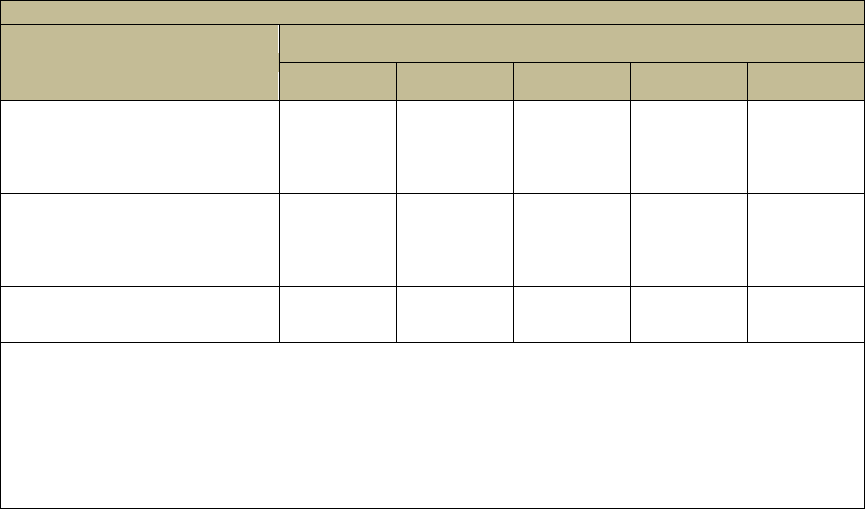

TABLE 3. Characteristics of Individual LTC Insurance by Purchase Year

Socio-Demographic

Characteristics

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Average Age

68

69

67

61

59

70 and over

42%

49%

40%

16%

8%

Percent Female

63%

61%

55%

57%

54%

Percent married

68%

62%

70%

75%

72%

Median Income

$27,000

$30,000

$42,500

$62,500

$87,500

% Greater than $50,000

21%

20%

42%

71%

77%

Median Assets

N.A.

$87,500

$225,000

$275,000

$325,000

% Greater than $75,000

53%

49%

77%

83%

82%

Percent College-Educated

33

36

47

61

71

Percent Employed

N.A.

23%

35%

71%

69%

SOURCE: Who Buys Long-Term Care Insurance in 2010-2011? A Twenty-Year Study of Buyers and

Non-Buyers (in the Individual Market), AHIP, 2012.

One of the ways policymakers have worked to expand the private insurance

market to reach middle income adults is to support Partnership Programs. These

programs -- which represent a partnership between state Medicaid programs and the

private insurance industry -- are designed to enable individuals who purchase qualified

LTC insurance policies to access Medicaid benefits without having to spend down their

assets to Medicaid levels, if and when their LTC insurance benefits are exhausted. A

growing number of states -- upwards of 45 by the end of 2012 -- have implemented

such programs.

36

Even so, few people age 50 and over -- less than 25% -- actually

know whether or not their state has a Partnership Program. However, the Program

does hold appeal: fully 45% of a random sample of individuals over age 50 indicated

that they would be likely to purchase a policy if their state participated in a Partnership

Program.

37

For individuals who have been approached by agents and choose not to buy a

policy, most cite cost as the primary impediment to purchase. Other far less prevalent

reasons typically include the difficulty of choosing a policy, a lack of confidence in

insurers to pay benefits as stated, and the desire to wait to see if better policies come

on the market.

38

5. Regulatory Framework and Public Policy

The first reported interest in developing a regulatory framework for private LTC

insurance was in 1985 when a series of conferences between legislators, regulators

and industry representatives were held; there was also growing interest in Congress in

35

Authors’ analysis of data summarized in AHIP Study of Buyers and Non-Buyers of Private LTC Insurance in

2010, Washington, DC.

36

Website on Partnership Programs: http://w2.dehpg.net/LTCPartnership.

37

Who Buys Long-Term Care Insurance in 2010-2011? A Twenty-Year Study of Buyers and Non-Buyers (in the

Individual Market), AHIP, 2012.

38

Ibid.

22

the area of nursing home insurance.

39

As a result of a sustained effort, NAIC adopted

the first Model Act in December 1986, followed by the first model regulation in 1987.

Many states adopted these model regulations. In fact, by 1989, more than two-thirds of

states had adopted the NAIC model act and/or regulation.

40

The model regulations

became the reference point for companies developing or modifying policies they were