overview

CITIZENS UNITED

v. F.E.C., 2010

CritiCal EngagEmEnt QuEstion

Assess whether the Supreme Court ruled correctly in

Citizens United v. F.E.C., 2010, in light of constitutional

principles including republican government and

freedom of speech.

lEarning objECtivEs

Students will:

• Understand the Founders’

reasons for affording

political speech the greatest

protection.

• Apply principles of republican

government and freedom

of speech to evaluate the

decision in Citizens United v.

F.E.C., 2010

matErials

Handout A: Agree or Disagree

Handout B: Citizens United v. F.E.C.,

2010, Background Essay

Handout C: Citizens United v. F.E.C.,

2010

gradE lEvEl and timE

Two 50-minute high school classes

standards

CCE (9-12): IIC2; IID3; IID5

NCHS: Era 3, Standard 3; Era 7,

Standard 1; Era 10, Standard 1

NCSS: Strands 2, 5, 6 and 10

Common Core (Grades 9-10):

9. Analyze seminal U.S.

documents of historical and

literarysignicance(e.g.,

Washington’s Farewell Address,

the Gettysburg Address,

Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms

speech, King’s “Letter from

Birmingham Jail”), including how

they address related themes and

concepts.

Common Core (Grades 11-12):

8. Delineate and evaluate the

reasoning in seminal U.S. texts,

including the application of

constitutional principles and use

oflegalreasoning(e.g.,inU.S.

Supreme Court majority opinions

and dissents) and the premises,

purposes, and arguments in

worksofpublicadvocacy(e.g.,

The Federalist, presidential

addresses).

9. Analyze seventeenth-,

eighteenth-, and nineteenth-

century foundational U.S.

documents of historical

andliterarysignicance

(includingTheDeclarationof

Independence, the Preamble

to the Constitution, the Bill of

Rights, and Lincoln’s Second

Inaugural Address) for their

themes, purposes, and

rhetorical features.

During his 2010 State

of the Union address,

President Barack Obama

did something very few

presidents have done:

he openly challenged a

Supreme Court ruling in

front of both chambers of

Congress and members of

the Supreme Court of the

United States. That ruling,

Citizens United v. F.E.C.

(2010),andthePresident’s

commentary on it,

reignited passions on both

sides of a century-long

debate: to what extent

does the First Amendment

protect the variety of

ways Americans associate

with one another and

the diverse ways we

“speak, ” “assemble,” and

participate in American

political life? It is this

speech – political speech

– that the Founders knew

was inseparable from

the very concept of self-

government.

2

Why Does a Free Press Matter?

NOTES

LESSON PLAN

DAY I

Warm-up

15 minutes

Distribute Handout A: Agree or Disagree, and have students work

individually or with a partner to mark each statement. Reconvene as a large

group and share responses. You may wish to tell students that statements 1-3

contain actions which, according to the majority in Citizen United, would be

felonies had the BCRA provision at issue in the case not been struck down

by the ruling. Statements 4-6 are all from the majority opinion.

activity

25 minutes

Distribute Handout B: Citizens United v. F.E.C., 2010, Background Essay and

have students read independently, or read aloud as a class.

Wrap-up

10 minutes

As a class, go over the critical thinking questions. Have students write

complete responses for homework.

DAY II

Warm-up

10 minutes

Asaclass,gooverdenitionsoftheconstitutionalprinciplesofrepublican

government and freedom of speech. Republican governments, also called

representative governments or mixed governments, are those where power

of government resides with the people or is lent to their representatives.

Freedom of speech is an example of a right the Founders believed was

inalienable and necessary for self-government.

activity

30 minutes

Distribute Handout C: Citizens United v. F.E.C., 2010. Have students work

in pairs or trios to go over the documents and answer the scaffolding

questions. Depending on students’ reading levels and familiarity with

primary sources, you may wish to divide the documents among groups.

Wrap-up

10 minutes

Spend focused time on the majority opinion in Citizens v. United,

encouraging students to share their evaluations of the ruling, grounding

their answers in the Constitution. You may wish to reveal, if you did not do

so earlier, that the statements 1-3 on Handout A contained actions which,

according to the majority in Citizen United, would be felonies had the BCRA

provision at issue in the case not been struck down by the ruling. Statements

4-6 are all from the majority opinion.

Have students write their essay responses for homework or in class next time.

3

© The Bill of Rights Institute

Citizens United

A

AGREE OR DISAGREE?

Directions: Mark each statement with an “A” if you agree or a “D” if you disagree.

_______ 1. Government should be able to punish the Sierra Club if it were to run an ad

immediately before a general election, trying to convince voters to disapprove of a

Congressman who favors logging in national forests.

_______ 2. GovernmentshouldbeabletopunishtheNationalRieAssociationifitwereto

publish a book urging the public to vote for the challenger because the incumbent

U. S. Senator supports a handgun ban.

_______ 3. Government should be able to punish the American Civil Liberties Union if it creates

a website telling the public to vote for a presidential candidate in light of that

candidate’s defense of free speech.

_______ 4. “TheFirstAmendmentprotectsspeechandspeaker,andtheideasthatowfrom

each.”

_______ 5. “IftheFirstAmendmenthasanyforce,itprohibitsCongressfromningorjailing

citizens, or associations of citizens, for simply engaging in political speech.”

_______ 6. “When Government seeks to use its full power, including the criminal law, to

command where a person may get his or her information or what distrusted source

he or she may not hear, it uses censorship to control thought. This is unlawful. The First

Amendmentconrmsthefreedomtothinkforourselves.”

4

Citizens United

© The Bill of Rights Institute

B

BACKGROUND ESSAY

Citizens United v. F.E.C., 2010

During his 2010 State of the Union address,

President Barack Obama did something very few

presidents have done: he openly challenged a

Supreme Court ruling in front of both chambers

of Congress and members of the Supreme

Court of the United States. That ruling, Citizens

United v. F.E.C.(2010),andthePresident’s

commentary on it, reignited passions on both

sides of a century-long debate: to what extent

does the First Amendment protect the variety

of ways Americans associate with one another

and the diverse ways we “speak,” “assemble,”

and participate in American political life? It is this

speech – political speech – that the Founders

knew was inseparable from the very concept of

self government.

Since the rise of modern “big business” in the

Industrial Age, Americans have expressed

concernsabouttheinuenceofcorporationsand

other “special interests” in our political system. In

1910 President Teddy Roosevelt called for laws

to “prohibit the use of corporate funds directly or

indirectly for political purposes…[as they supply]

one of the principal sources of corruption in our

political affairs.” Already having made such

corporate contributions illegal with the Tillman Act

of 1907, Roosevelt’s speech nonetheless prompted

Congress to amend this law to add enforcement

mechanisms with the 1910 Federal Corrupt

Practices Act. Future Congresses would enlarge

the sphere of “special interests” barred from direct

campaign contributions through – among others

-theHatchAct(1939),restrictingthepolitical

campaign activities of federal employees, and

theTaft-HartleyAct(1947),prohibitinglaborunions

from expenditures that supported or opposed

particular federal candidates.

Collectively, these laws formed the backbone of

America’scampaignnancelawsuntiltheywere

replaced by the Federal Elections Campaign

Acts(FECA)of1971and1974.FECAof1971

strengthened public reporting requirements of

campaignnancingforcandidates,political

partiesandpoliticalcommittees(PACs).TheFECA

of1974addedspeciclimitstotheamountof

money that could be donated to candidates by

individuals, political parties, and PACs, and also

what could be independently spent by people

who want to talk about candidates. It provided for

the creation of the Federal Election Commission,

an independent agency designed to monitor

campaigns and enforce the nation’s political

nancelaws.Signicantly,FECAleftmembers

of the media, including corporations, free to

comment about candidates without limitation,

even though such commentary involved spending

money and posed the same risk of quid pro quo

corruption as other independent spending.

In Buckley v. Valeo (1976), however, portions

of the FECA of 1974 were struck down by the

Supreme Court. The Court deemed that restricting

independent spending by individuals and groups

to support or defeat a candidate interfered

with speech protected by the First Amendment,

so long as those funds were independent of a

candidate or his/her campaign. Such restrictions,

the Court held, unconstitutionally interfered with

the speakers’ ability to convey their message

to as many people as possible. Limits on direct

campaign contributions, however, were

permissible and remained in place. The Court’s

rationale for protecting independent spending

was not, as is sometimes stated, that the Court

equated spending money with speech. Rather,

restrictions on spending money for the purpose

of engaging in political speech unconstitutionally

interfered with the First Amendment-protected

righttofreespeech.(TheCourtdidmentionthat

direct contributions to candidates could be seen

as symbolic expression, but concluded that they

were generally restrict-able despite that.)

The decades following Buckley would see a

great proliferation of campaign spending. By

2002, Congress felt pressure to address this

spending and passed the Bipartisan Campaign

FinanceReformAct(BCRA).Akeyprovision

of the BCRA was a ban on speech that was

deemed “electioneering communications”

– speech that named a federal candidate

within 30 days of a primary election or 60 days

of a general election that was paid for out of a

“specialinterest’s”generalfund(PACswereleft

5

© The Bill of Rights Institute

Citizens United

BACKGROUND ESSAY

Citizens United v. F.E.C., 2010

comprehension and critical thinking Questions

1. Summarizethewaysinwhichvariouscampaignnancelawshaverestrictedthepolitical

activities of groups, including corporations and unions.

2. What was the main idea of the ruling in Buckley v. Valeo?

3. What political activity did the group Citizens United engage in during the 2008 primary

election? How was this activity potentially illegal under the BCRA?

4. How did the Supreme Court rule in Citizens United v. F.E.C.? In what way is it connected to the

ruling in Buckley?

5. DoyoubelievethattheFirstAmendmentshouldprotectcollectivespeech(i.e.groups,including

“special interests”) to the same extent it protects individual speech? Why or why not?

6. What if the government set strict limits on people spending money to get the assistance of

counsel, or to educate their children, or to have abortions? Or what if the government banned

candidates from traveling in order to give speeches? Would these hypothetical laws be

unconstitutional under the reasoning the Court applied in Buckley and Citizens United? Why or

why not?

untouched by this prohibition). An immediate First

Amendment challenge to this provision – in light

of the precedent set in Buckley – was mounted in

McConnell v. F.E.C. (2003). But the Supreme Court

uphelditasarestrictionjustiedbytheneed

to prevent both “actual corruption…and the

appearance of corruption.”

Another constitutional challenge to the BRCA

would be mounted by the time of the next general

election.CitizensUnited,anonprotorganization,

was primarily funded by individual donations,

with relatively small amounts donated by for-

protcorporationsaswell.Intheheatofthe2008

primary season, Citizens United released a full-

lengthlmcriticalofthen-SenatorHillaryClinton

entitled Hillary: the Movie.Thelmwasoriginally

released in a limited number of theaters and on

DVD, but Citizens United wanted it broadcast to a

wider audience and approached a major cable

company to make it available through their “On-

Demand” service. The cable company agreed

and accepted a $1.2 million payment from Citizens

United in addition to purchased advertising time,

making it free for cable subscribers to view.

SincethelmnamedcandidateHillary

Clinton and its On-Demand showing would fall

within the 30-days-before-a-primary window,

Citizens United feared it would be deemed an

“electioneering communications” under the

BCRA. The group mounted a preemptive legal

challenge to this aspect of the law in late 2007,

arguing that the application of the provision

to Hillary was unconstitutional and violated the

First Amendment in their circumstance. A lower

federal court disagreed, and the case went to

the Supreme Court in early 2010.

In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled in

Citizens United v. F.E.C. that: 1) the BCRA’s

“electioneering communications” provision did

indeed apply to Hillary and that 2) the law’s

ban on corporate and union independent

expenditures was unconstitutional under the First

Amendment’s speech clause. “Were the Court

to uphold these restrictions,” the Court reasoned,

“the Government could repress speech by

silencing certain voices at any of the various

points in the speech process.” Citizens United v.

F.E.C. extended the principle, set 34 years earlier

in Buckley, that restrictions on spending money

for the purpose of engaging in political speech

unconstitutionally burdened the right to free

speech protected by the First Amendment.

6

Citizens United

© The Bill of Rights Institute

C

CITIZENS UNITED V. F.E.C., 2010

Directions: Read the Background Essay and Key Question. Then analyze Documents A-L. Finally, answer

the Key Question in a well-organized essay that incorporates your interpretations of Documents A-L, as

well as your own knowledge of history.

key Question

Assess whether the Supreme Court ruled correctly in Citizens

United v. F.E.C., 2010, in light of constitutional principles including

republican government and freedom of speech.

Document A: Federalist # 10, James Madison, 1787

Document B: Thomas Jefferson to Edward Carrington, 1787

Document C: The First Amendment, 1791

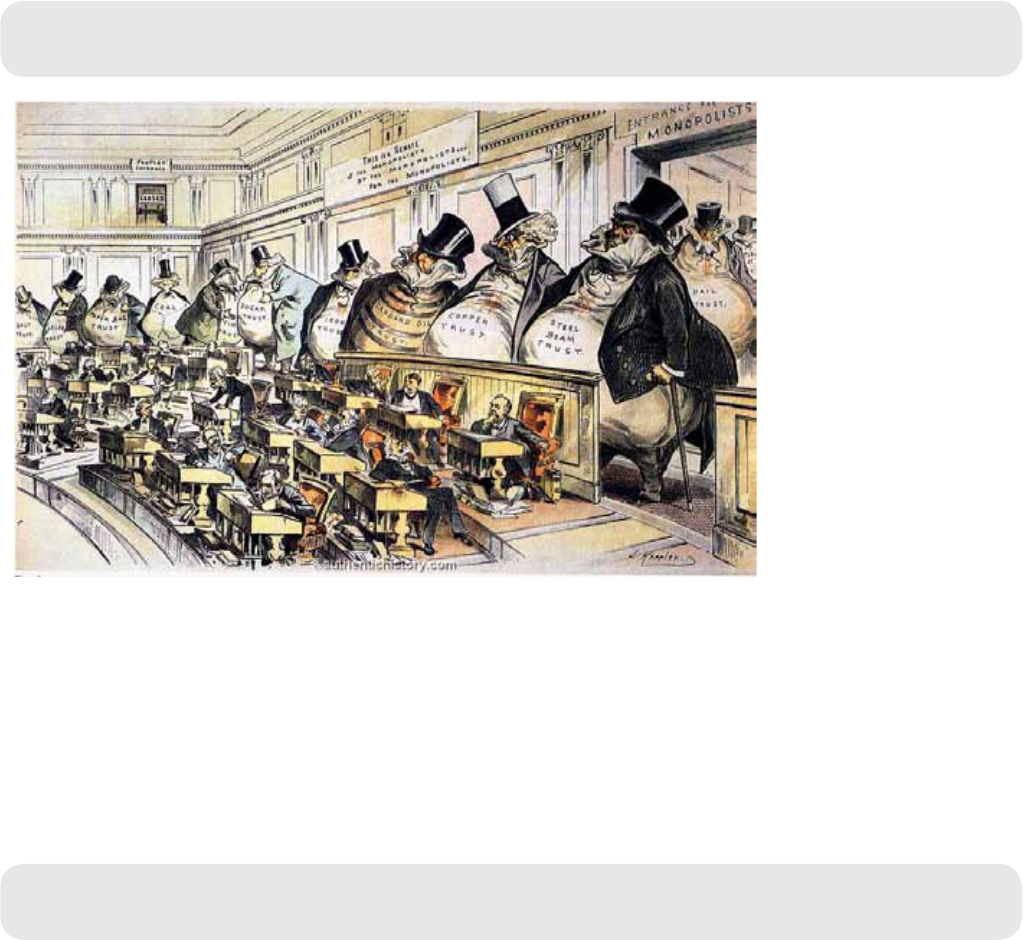

Document D: “The Bosses of the Senate,” Joseph Keppler, 1889

Document E: New Nationalism Speech, Teddy Roosevelt, 1910

Document F: Buckley v. Valeo, 1976

Document G: Citizens United Mission Statement, 1988

Document H: McConnell v. F.E.C., 2003

Document I: Citizens United v. F.E.C., 2010

Document J: Dissenting Opinion, Citizens United v. F.E.C., 2010

Document K: Concurring Opinion, Citizens United v. F.E.C., 2010

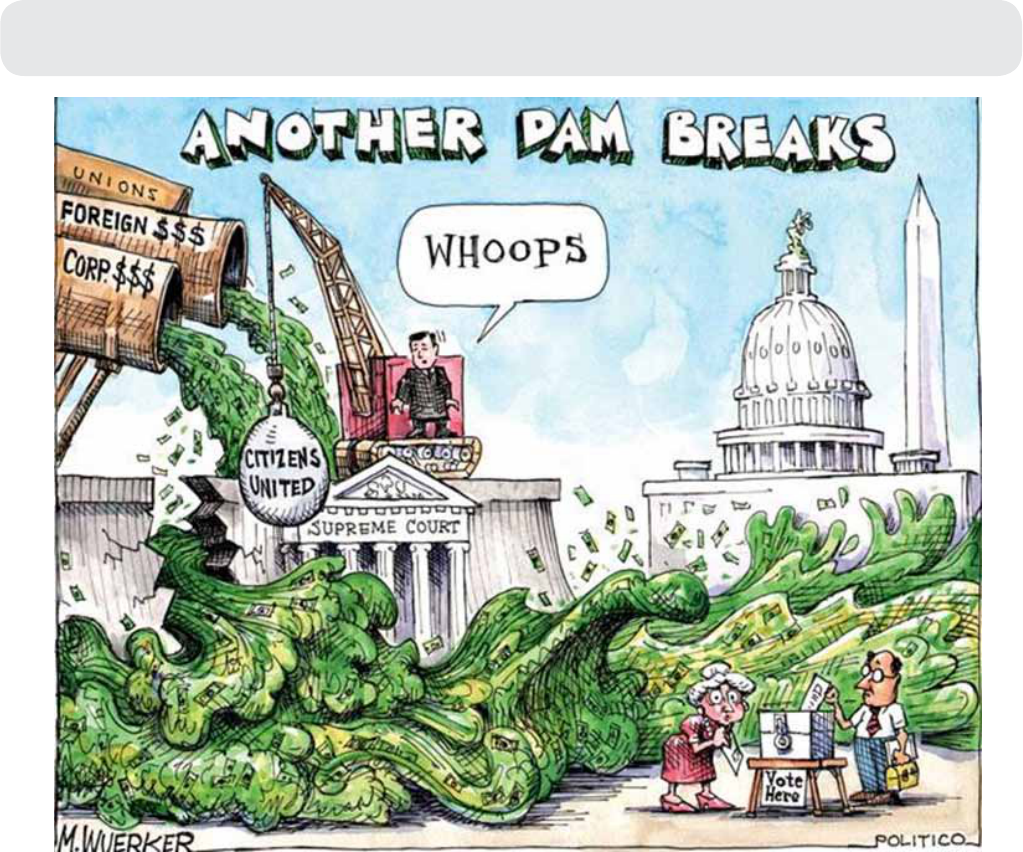

Document L: “Another Dam Breaks,” Matt Wuerker, 2010

7

© The Bill of Rights Institute

Citizens United

document a:

Federalist # 10

, James madison, 1787

By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority

of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest,

adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the

community.

There are two methods of curing the mischiefs of faction: the one, by removing its causes; the

other, by controlling its effects.

There are again two methods of removing the causes of faction: the one, by destroying the

liberty which is essential to its existence; the other, by giving to every citizen the same opinions,

the same passions, and the same interests.

Itcouldneverbemoretrulysaidthanoftherstremedy,thatitwasworsethanthedisease.

Libertyistofactionwhatairistore,analimentwithoutwhichitinstantlyexpires.Butitcouldnot

be less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than

it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life, because it imparts to

reitsdestructiveagency.

[Because] the causes of faction cannot be removed…relief is only to be sought in the means

of controlling its effects…If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the

republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views by regular vote.

1. How does James Madison dene a faction?

2. What does Madison argue serves as a “check” on the inuence various factions may

have on society?

3. Would the Federalist Papers have been legal under the BCRA?

8

Citizens United

© The Bill of Rights Institute

document B: thomas JeFFerson to edWard carrington, 1787

I am persuaded myself that the good sense of the people will always be found to be the best

army. They may be led astray for a moment, but will soon correct themselves. The people are

the only censors of their governors: and even their errors will tend to keep these to the true

principles of their institution. To punish these errors too severely would be to suppress the only

safeguard of the public liberty. ... The basis of our governments being the opinion of the people,

theveryrstobjectshouldbetokeepthatright;andwereitlefttometodecidewhetherwe

should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should

not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter. But I should mean that every man should receive

those papers and be capable of reading them….

If once they become inattentive to the public affairs, you and I, and Congress, and Assemblies,

judges and governors shall all become wolves.

1. What does Jefferson believe is “the basis of our governments”?

2. What does Jefferson believe is “the only safeguard of the public liberty”?

3. What does Jefferson seem to believe is a possible disadvantage of press freedom? Why

does he nd it acceptable?

4. What does Jefferson predict will happen if the people become inattentive to public

affairs?

document c: the First amendment, 1791

Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of

the people peaceably to assemble and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

1. Why did the Founders deem speech and assembly so vital to self-government?

2. List a variety of ways you see Americans “speak” and “assemble” in political life.

9

© The Bill of Rights Institute

Citizens United

document d: “the Bosses oF the senate,” Joseph keppler, 1889

1. How does this cartoon express the concern of “quid pro quo” corruption?

2. What is the signicance of the closed door with the sign above it in the upper left hand

corner of the cartoon?

3. Did Madison’s assertion in Federalist 10 (Document A) – that the republican principle will

serve as a check on the inuence of factions – apply in the cartoon’s time period? Does it

apply today?

document e: neW nationalism speech, teddy roosevelt, 1910

[O]urgovernment,NationalandState,mustbefreedfromthesinisterinuenceorcontrolof

special interests. Exactly as the special interests of cotton and slavery threatened our political

integrity before the Civil War, so now the great special business interests too often control and

corruptthemenandmethodsofgovernmentfortheirownprot.Wemustdrivethespecial

interests out of politics. … [E]very special interest is entitled to justice, but not one is entitled

toavoteinCongress,toavoiceonthebench,ortorepresentationinanypublicofce.The

Constitution guarantees protection to property, and we must make that promise good. But it

does not give the right of suffrage to any corporation.

1. What does Roosevelt mean by “special interests”?

2. How does this concept relate to Madison’s denition of “faction”?

10

Citizens United

© The Bill of Rights Institute

document F:

Buckley v. valeo

, 1976

Advocacyoftheelectionordefeatofcandidatesforfederalofceisnolessentitledto

protection under the First Amendment than the discussion of political policy generally or

advocacy of the passage or defeat of legislation...Discussion of public issues and debate on

thequalicationsofcandidatesareintegraltotheoperationofthesystemofgovernment

established by our Constitution. The First Amendment affords the broadest possible protection to

such political expression in order to assure unfettered exchange of ideas for the bringing about

of political and social changes desired by the people…A restriction on the amount of money

a person or group can spend on political communication during a campaign necessarily

reduces the quantity of expression by restricting the number of issues discussed, the depth of

their exploration, and the size of the audience reached. This is because virtually every means of

communicating ideas in today’s mass society requires the expenditure of money.

1. Restate this excerpt from the Buckley ruling in your own words.

document g: citizens united mission statement, 1988

Citizens United is an organization dedicated to restoring our government to citizens’ control.

Through a combination of education, advocacy, and grass roots organization, Citizens United

seeks to reassert the traditional American values of limited government, freedom of enterprise,

strong families, and national sovereignty and security. Citizens United’s goal is to restore the

founding fathers’ vision of a free nation, guided by the honesty, common sense, and good

will of its citizens…Citizens United has a variety of different projects that help it uniquely and

successfullyfulllitsmission.CitizensUnitediswellknownforproducinghigh-impact,sometimes

controversial,butalwaysfact-baseddocumentarieslledwithinterviewsofexpertsandleaders

intheirelds.

1. Do you believe James Madison would consider Citizens United a faction? Why or why

not?

2. Is Citizens United an “assembly” of people seeking to engage in political “speech?” Why

or why not?

11

© The Bill of Rights Institute

Citizens United

document h: maJority opinion,

mcconnell v. F.e.c.

, 2003

Because corporations can still fund electioneering communications with PAC money, it is ‘simply

wrong’ to view the [BCRA] provision as a ‘complete ban’ on expression…

We have repeatedly sustained legislation aimed at ‘the corrosive effects of immense

aggregations of wealth that are accumulated with the help of the corporate form’ …[T]he

government has a compelling interest in regulating advertisements that expressly advocate

theelectionordefeatofacandidateforfederalofce…corporationsandunionsmaynance

genuineissueadsduringthosetimeframesbysimplyavoidinganyspecicreferencetofederal

candidates, or…by paying for the ad from a segregated fund [PAC].

1. Restate the McConnell opinion in your own words.

2. In your opinion, is the McConnell ruling consistent with the ruling in Buckley (Document F)

in its interpretation of the First Amendment?

12

Citizens United

© The Bill of Rights Institute

document i:

citizens united v. F.e.c.

, 2010

TheF.E.C.hasadopted568pagesofregulations,1,278pagesofexplanationsandjustications

for those regulations, and 1,771 advisory opinions since 1975. … given the complexity of the

regulations and the deference courts show to administrative determinations, a speaker who

wants to avoid threats of criminal liability and the heavy costs of defending against F.E.C.

enforcement must ask a governmental agency for prior permission to speak.

IftheFirstAmendmenthasanyforce,itprohibitsCongressfromningorjailingcitizens,or

associations of citizens, for simply engaging in political speech. All speakers, including individuals

and the media, use money amassed from the economic marketplace to fund their speech. The

First Amendment protects the resulting speech.

Atthefounding,speechwasopen,comprehensive,andvitaltosociety’sdenitionofitself;there

were no limits on the sources of speech and knowledge….By suppressing the speech of manifold

corporations,bothfor-protandnonprot,theGovernmentpreventstheirvoicesandviewpoints

from reaching the public and advising voters on which persons or entities are hostile to their interests.

Factions will necessarily form in our Republic, but the remedy of ‘destroying the liberty’ of some

factions is ‘worse than the disease’ [Federalist 10]. Factions should be checked by permitting them

all to speak, and by entrusting the people to judge what is true and what is false...

When Government seeks to use its full power, including the criminal law, to command where a

person may get his or her information or what distrusted source he or she may not hear, it uses

censorshiptocontrolthought.Thisisunlawful.TheFirstAmendmentconrmsthefreedomto

think for ourselves.

Theappearanceofinuenceoraccess,furthermore,willnotcausetheelectoratetolosefaith

inourdemocracy.Bydenition,anindependentexpenditureispoliticalspeechpresentedto

the electorate that is not coordinated with a candidate. The fact that a corporation, or any

other speaker, is willing to spend money to try to persuade voters presupposes that the people

havetheultimateinuenceoverelectedofcials.

Rapid changes in technology—and the creative dynamic inherent in the concept of free

expression—counsel against upholding a law that restricts political speech in certain media or

by certain speakers. Today, 30-second television ads may be the most effective way to convey

a political message. Soon, however, it may be that Internet sources … will provide citizens with

signicantinformationaboutpoliticalcandidatesandissues.Yet,[theBCRA]wouldseemtoban

a blog post expressly advocating the election or defeat of a candidate if that blog were created

with corporate funds. The First Amendment does not permit Congress to make these categorical

distinctions based on the corporate identity of the speaker and the content of the political speech.

1. Why does the Court say that current F.E.C. regulations results in citizens needing

“permission to speak”?

2. Why does the Court say that “The First Amendment conrms the freedom to think for

ourselves”?

3. The Court reasoned, “The appearance of inuence or access, furthermore, will not cause

the electorate to lose faith in our democracy.” Do you agree? What effect, if any, does

this ruling have on the republican principle of the United States government?

13

© The Bill of Rights Institute

Citizens United

document J: dissenting opinion,

citizens united v. F.e.c.

, 2010

[In] a variety of contexts, we have held that speech can be regulated differentially on account

of the speaker’s identity, when identity is understood in categorical or institutional terms. The

Government routinely places special restrictions on the speech rights of students, prisoners,

members of the Armed Forces, foreigners, and its own employees.

Unlike our colleagues, the Framers had little trouble distinguishing corporations from human

beings, and when they constitutionalized the right to free speech in the First Amendment, it was

the free speech of individual Americans that they had in mind. … [M]embers of the founding

generation held a cautious view of corporate power and a narrow view of corporate rights…

and…they conceptualized speech in individualistic terms. If no prominent Framer bothered to

articulate that corporate speech would have lesser status than individual speech, that may well

be because the contrary proposition—if not also the very notion of “corporate speech”—was

inconceivable.

On numerous occasions we have recognized Congress’s legitimate interest in preventing

themoneythatisspentonelectionsfromexertingan‘undueinuenceonanofceholder’s

judgment’andfromcreating‘theappearanceofsuchinuence.’Corruptionoperatesalong

a spectrum, and the majority’s apparent belief that quid pro quo arrangements can be neatly

demarcatedfromotherimproperinuencesdoesnotaccordwiththetheoryorrealityof

politics….A democracy cannot function effectively when its constituent members believe laws

are being bought and sold.

A regulation such as BCRA may affect the way in which individuals disseminate certain

messages through the corporate form, but it does not prevent anyone from speaking in his or

her own voice.

At bottom, the Court’s opinion is thus a rejection of the common sense of the American people,

who have recognized a need to prevent corporations from undermining self-government since

the founding, and who have fought against the distinctive corrupting potential of corporate

electioneering since the days of Theodore Roosevelt. It is a strange time to repudiate that

common sense. While American democracy is imperfect, few outside the majority of this Court

wouldhavethoughtitsawsincludedadearthofcorporatemoneyinpolitics.

1. How does the reasoning in the dissenting opinion differ from that of the Majority

(Document I)?

2. How would you evaluate the dissenters statement, “A democracy cannot function

effectively when its constituent members believe laws are being bought and sold.”

14

Citizens United

© The Bill of Rights Institute

document k: concurring opinion, citizens united v. F.e.c., 2010

TheFramersdidn’tlikecorporations,thedissentconcludes,andthereforeitfollows(asnightthe

day) that corporations had no rights of free speech.

The lack of a textual exception for speech by corporations cannot be explained on the ground

that such organizations did not exist or did not speak. To the contrary…both corporations

and voluntary associations actively petitioned the Government and expressed their views in

newspapers and pamphlets. For example: An antislavery Quaker corporation petitioned the First

Congress, distributed pamphlets, and communicated through the press in 1790. The New York

Sons of Liberty sent a circular to colonies farther south in 1766. And the Society for the Relief and

Instruction of Poor Germans circulated a biweekly paper from 1755 to 1757.

The dissent says that when the Framers “constitutionalized the right to free speech in the First

Amendment, it was the free speech of individual Americans that they had in mind.” That is

no doubt true. All the provisions of the Bill of Rights set forth the rights of individual men and

women—not, for example, of trees or polar bears. But the individual person’s right to speak

includes the right to speak in association with other individual persons. Surely the dissent does

not believe that speech by the Republican Party or the Democratic Party can be censored

because it is not the speech of “an individual American.” It is the speech of many individual

Americans, who have associated in a common cause, giving the leadership of the party the

right to speak on their behalf. The association of individuals in a business corporation is no

different—or at least it cannot be denied the right to speak on the simplistic ground that it is not

“an individual American.”

1. Why does this Justice argue that the original understanding of the First Amendment does

not allow for limitations on the speech of associations such as corporations and unions?

Do you agree?

15

© The Bill of Rights Institute

Citizens United

document l: “another dam Breaks,” matt Wuerker, 2010

1. What does the cartoonist predict will be the effect of the Citizens United ruling?

2. What assumptions does the cartoonist seem to make about voters? Are they valid

assumptions? Explain.

16

Citizens United

© The Bill of Rights Institute

lesson ansWer key

Handout A: Agree or Disagree

1. Governments could place no restraints on

publication in advance.

2. The law did not impose a prior restraint. That is,

it did not prevent publication in advance.

3. The Court ruled that a broad claim of national

security did not justify a prior restraint under the

First Amendment. Accept reasoned answers.

4. The Court reasoned that free and open debate

abouttheconductofpublicofcialswasmore

important than occasional, honest factual errors

thatmighthurtordamageofcials’reputations.

Accept reasoned answers.

5. Accept reasoned answers.

Handout B: Citizens United v. F.E.C., 2010

Background Essay

1. The banning of direct campaign contributions

bycorporations(TillmanAct,1907),limitations

onactivitiesoffederalemployees(HatchAct,

1939), banning direct campaign contributions

bylaborunions(Taft-Hartley,1947),public

reporting requirements and dollar-amount

limitationsoncontributions(FECA,1971

& 1974), and a ban on “electioneering

communications” within a set time period prior

toelections(BCRA,2002).

2. The Court deemed that restricting independent

spending by individuals and groups to support

or defeat a candidate interfered with speech

protected by the First Amendment, so long as

those funds were independent of a candidate

or his/her campaign. Such restrictions, the

Court held, unconstitutionally interfered with

the speakers’ ability to convey their message

to as many people as possible.

3. CitizensUnited,anon-protgroupfunded

by donations, produced a feature-length

movie critical of presidential candidate

Hillary Clinton. The movie was to be shown

nationwide in select theaters and through a

major cable company’s On-Demand service.

It potentially ran afoul of the BCRA’s limitation

on “electioneering communications” within

30-days of a primary election or 60-days of a

general election, paid for by a corporation’s

general fund.

4. Citizens United v. F.E.C. extended the principle,

set 34 years earlier in Buckley, that restrictions

on spending money for the purpose of

engaging in political speech unconstitutionally

burdened the right to free speech protected

by the First Amendment.

5. Accept reasoned answers.

6. Using the same reasoning as the Court did in

Buckley, these laws would be unconstitutional.

They would be unconstitutional not because

“spending [on a lawyer] amounted to

[assistance of counsel] protected by the [Sixth]

Amendment,” or that “spending [on a private

education] amounted to [private education]

protected by the [Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment],” or that “spending

[on an abortion] amounted to [an abortion]

protected by the [Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment].” Rather, the reasoning

would be that banning such spending

unconstitutionally interfered with the rights

to assistance of counsel, private education,

or an abortion. Likewise, a government ban

on candidates from traveling in order to

give campaign speeches would likely be

unconstitutional because the ban on travel

unconstitutionally burdened the right to speak.

citizens united dBQ ansWer key

Document A: Federalist # 10, James Madison, 1787

1. According to Madison, a faction is a number

of citizens who are 1) united by a common

interest and 2) opposed to the rights of

others and/or the permanent interest of the

community.

2. ForMadison,onecheckontheinuenceof

factions is regular elections.

3. Accept reasoned answers.

Document B: Thomas Jefferson to Edward

Carrington, 1787

1. The opinion of the people

2. “The only safeguard of the public liberty” is, for

Jefferson, the ability of the people to speak

and publish their opinions on governmental

matters freely. Too much information is

preferable to too little.

17

© The Bill of Rights Institute

Citizens United

3. A disadvantage to press freedom is that

the people may be led astray at times. This

possibility is acceptable to Jefferson because

he believes their good sense will win out, and

they will correct themselves. Also, for all the

faults that people are prey to, government

censorship would be more dangerous than

public error.

4. Those with power will “become wolves,” which

is to say they will oppress those without power.

Document C: The First Amendment, 1791

1. Accept reasoned answers.

2. Giving speeches, speaking persuasively

to friends or larger audiences, producing

creative works, writing for a newspaper or

other publication, keeping a blog, posting to

YouTube, Facebook, or other social media,

writing letters to the editor, attending political

rallies, meeting in clubs or other groups.

Document D: “The Bosses of the Senate,” Joseph

Keppler, 1889

1. “Quid pro quo” refers to a more or less equal

exchange. In the context of political discourse,

the term often suggests bribery. “Quid pro

quo” refers to an expectation that, if wealthy

contributors donate large sums of money to

a political campaign, the person receiving

thisbenetwill,onceelected,usehisorher

inuencetoprovidesomespecialbenetto

the donor.

2. The cartoonist believes that, through their

nancialsupportofcandidates,thebusiness

interests of the industrial age have seized

control of the Senate, and are the “bosses”

of the Senators. The concern of quid pro quo

corruption is indicated by the position and

size,relativetotheSenators,ofthegures

representing business interests.

3. The closed door leading to the public gallery

above the Senate reinforces the author’s

message that the government is no longer

open to “the people.”

4. Accept reasoned answers. Students may note

that in the cartoon’s time period, Senators

were appointed by state legislatures.

Document E: New Nationalism Speech, Teddy

Roosevelt, 1910

1. Business interests that seek to “control and

corrupt the men and methods of government

fortheirownprot.”

2. Roosevelt’s description of “special interests”

seems very similar to Madison’s concept of

“faction.”

Document F: Buckley v. Valeo, 1976

1. Speech about candidates deserves the same

First Amendment protection as other kinds

of political speech. Civil discourse on politics

is essential for self government. Engaging in

speech requires spending money. Therefore,

limits on spending by individuals and groups

unconstitutionally burden their ability to speak

freely. The First Amendment protects the ability

to speak for or against a candidate, and was

meant to ensure such speech could occur in a

variety of ways.

Document G: Citizens United Mission Statement, 1988

1. Probably not. While Citizens United is “a number

of citizens…united and actuated by some

common…interest,” its activities do not satisfy

thesecondpartofthedenitionoffaction:

“adversed to the rights of other citizens, or to

the permanent and aggregate interests of the

community.”

2. Accept reasoned answers.

Document H: McConnell v. F.E.C., 2003

1. Since the BCRA leaves PACs free to engage in

political speech, corporations and unions are

not limited in their ability to speak, they merely

must do so through their PACs.

2. Accept reasoned answers.

Document I: Citizens United v. F.E.C., 2010

1. The Court reasons that, because laws

governing “electioneering communications”

are so voluminous and complicated, the

presumption has become that speech is illegal,

rather than free.

2. Citizens can and must judge for themselves

which voices they will listen to.

3. Accept reasoned answers.

18

Citizens United

© The Bill of Rights Institute

Document J: Dissenting Opinion, Citizens United v.

F.E.C., 2010

1. The dissent argues that the right to free speech

was designed to protect an individual’s right to

speak, and was never understood to apply to

corporations, which are business associations,

not political ones. The notion of “corporate

speech” was foreign to the Founders, and

the First Amendment doesn’t protect it at the

same level. Congress has a legitimate interest

inprotectingagainst“undueinuence”

and corruption, and the vast resources of

corporations – in comparison to individuals –

makesthis“undueinuence”morelikely.The

BCRA’s ban may regulate how a person, or

persons, may speak, but it does not prevent

anyone from speaking “in his own voice.”

2. Accept reasoned answers.

Document K: Concurring Opinion, Citizens United v.

F.E.C., 2010

1. This dissenting justice argues that corporations

existed at the time of the Founding. They

not only engaged in speech and petitioned

the government, but were understood

by the authors of the First Amendment to

have speech rights equivalent to individual

Americans. Further, the First Amendment does

not allow restrictions to be made on the basis

of who is speaking.

Document L: “Another Dam Breaks,” Matt Wuerker,

2010

1. The cartoonist believes the Supreme Court’s

ruling in Citizens United has “broken the dam”

holding back union and corporate money from

overwhelming American voters with political

speech. The resulting wave of “special interest”

moneythreatenstodrowntheinuenceand

voices of individual voting Americans.

2. Accept reasoned answers.

EnjoyFREE shipping!

StopbytheBillofRightsBookstoreandreceive

FREEshippingonyourENTIREorderifyou

placebeforeNovember30,2012.

Atcheckoutusepromocode“CITIZENSDBQ”

Visitthestoreat:http://BillofRightsInstitute.org/products ‐page/