Hospital emergency

response checklist

An all-hazards tool for

hospital administrators and

emergency managers

Supported by

The European Commission

Health Programme

2008-2013

Together for Health

Hospital emergency response

checklist

An all-hazards tool for hospital administrators

and emergency managers

Hospitals play a critical role in providing communities with essential medical care during all types of disaster. De-

pending on their scope and nature, disasters can lead to a rapidly increasing service demand that can overwhelm

the functional capacity and safety of hospitals and the health-care system at large. The World Health Organization

Regional Office for Europe has developed the Hospital emergency response checklist to assist hospital administrators

and emergency managers in responding effectively to the most likely disaster scenarios. This tool comprises current

hospital-based emergency management principles and best practices and integrates priority action required for rapid,

effective response to a critical event based on an all-hazards approach. The tool is structured according to nine key

components, each with a list of priority action to support hospital managers and emergency planners in achieving:

(1) continuity of essential services; (2) well-coordinated implementation of hospital operations at every level; (3) clear

and accurate internal and external communication; (4) swift adaptation to increased demands; (5) the effective use

of scarce resources; and (6) a safe environment for health-care workers. References to selected supplemental tools,

guidelines and other applicable resources are provided. The principles and recommendations included in this tool

may be used by hospitals at any level of emergency preparedness. The checklist is intended to complement existing

multisectoral hospital emergency management plans and, when possible, augment standard operating procedures

during non-crisis situations.

This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein

can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union.

Keywords

EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES

EMERGENCY SERVICE, HOSPITAL

DELIVERY OF HEALTH CARE

HOSPITAL PLANNING

Address requests about publications of the WHO Regional Office for Europe to:

Publications

WHO Regional Office for Europe

Scherfigsvej 8

DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark

Alternatively, complete an online request form for documentation, health information, or for permission to quote or

translate, on the Regional Office web site (http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest).

Abstract

© World Health Organization 2011

All rights reserved. The Regional Office for Europe of the World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its

publications, in part or in full.

The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of

the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its

frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health

Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are

distinguished by initial capital letters.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the pub-

lished material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material

lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. The views expressed by authors, editors,

or expert groups do not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the World Health Organization.

5

Page

Main authors ....................................................................................................6

Glossary ...........................................................................................................7

Introduction .....................................................................................................9

Key component 1. Command and control .................................................10

Key component 2. Communication ............................................................12

Key component 3. Safety and security .......................................................13

Key component 4. Triage ...........................................................................14

Key component 5. Surge capacity .............................................................15

Key component 6. Continuity of essential services .....................................16

Key component 7. Human resources .........................................................17

Key component 8. Logistics and supply management ...............................19

Key component 9. Post-disaster recovery ..................................................20

References .....................................................................................................21

Recommended reading .................................................................................22

Contents

6

Dr Brian S. Sorensen

Attending Physician, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Associate Faculty, Harvard Humanitarian Initiative

Instructor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School

Boston

United States of America

Dr Richard D. Zane

Vice Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School

Boston

United States of America

Mr Barry E. Wante

Director of Emergency Management, Center for Emergency Preparedness

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Boston

United States of America

Dr Mitesh B. Rao

Emergency Physician, Yale-New Haven Hospital

New Haven, Connecticut

United States of America

Dr Michelangelo Bortolin

Emergency Physician, Torino Emergency Medical Services

Adjunct Faculty, Harvard-affiliated Disaster Medicine Fellowship

Torino

Italy

Dr Gerald Rockenschaub

Programme Manager, Country Emergency Preparedness Programme

WHO Regional Office for Europe

Copenhagen

Denmark

Main authors

Back

7

Capacity

The combination of all the strengths, attributes and resources available within an organization that can be used to

achieve agreed goals (1).

Command and control

The decision-making system responsible for activating, coordinating, implementing, adapting and terminating a pre-

established response plan (2).

Contingency planning

A process that analyses potential events or emerging situations that might threaten society or the environment and

establishes arrangements that would enable a timely, effective and appropriate response to such events should they

occur. The events may be specific, categorical, or all-hazard. Contingency planning results in organized and coordi-

nated courses of action with clearly identified institutional roles and resources, information processes and operational

arrangements for specific individuals, groups or departments in times of need (1).

Critical event

Any event in connection with which a hospital finds itself unable to deliver care in the customary fashion or to an ac-

cepted standard, event resulting in a mismatch of supply (capacity, resources, infrastructure) and demand (patients),

and requiring the hospital to activate contingency measures to meet demand.

Disaster

Any event or series of events causing a serious disruption of a community’s infrastructure – often associated with

widespread human, material, economic, or environmental loss and impact, the extent of which exceeds the ability of

the affected community to mitigate using existing resources (1).

Emergency

A sudden and usually unforeseen event that calls for immediate measures to mitigate impact (3).

Emergency response plan

A set of written procedures that guide emergency actions, facilitate recovery efforts and reduce the impact of an

emergency event.

Incident action plan

A document that guides operational activities of the Incident Command System during the response phase to a

particular incident. The document contains the overall incident objectives and strategy, general tactical actions, and

supporting information to enable successful completion of objectives (4).

Incident command group

A multidisciplinary body of the incident command system, which provides the overall technical leadership and over-

sight for all aspects of crisis management, coordinates the overall response, approves all action, response and mitiga-

tion plans, and serves as an authority on all activities and decisions.

Incident command system

The designated system of command and control, which includes a combination of facilities, equipment, personnel,

procedures, and means of communication, operating within a common organizational structure designed to aid in the

management of resources for emergency incidents (4).

Glossary

Back

8

Memorandum of understanding

A formal document embodying the firm commitment of two or more parties to an undertaking; it sets out the general

principles of the commitment but falls short of constituting a detailed contract or agreement (5).

Mutual-aid agreement

An agreement between agencies, organizations and jurisdictions, which provides a mechanism whereby emergency

assistance in the form of personnel, equipment, materials and other associated services can be obtained quickly. The

primary objective of the agreement is to facilitate the rapid, short-term deployment of emergency support prior to, dur-

ing and after an incident (6).

Policy

A formally advocated statement or understanding adopted to direct a course of action, including planning, command

and control, preparedness, mitigation, response and recovery (7).

Preparedness

The knowledge and capacities developed by governments, professional response and recovery organizations, com-

munities and individuals to effectively anticipate, respond to and recover from the impacts of likely, imminent, or cur-

rent hazardous events or conditions (1).

Recovery

Restoring or improving the functions of a facility affected by a critical event or disaster through decisions and action

taken after the event (8).

Resources

The personnel, finances, facilities and major equipment and supply items available or potentially available for assign-

ment to incident operations.

Response

The provision of emergency services and public assistance during or immediately after a disaster in order to save lives,

reduce health impacts, ensure public safety, and meet the basic subsistence needs of the people affected (1).

Risk assessment

A methodology for determining the nature and extent of risk, which involves analysing potential hazards and evaluating

their impact in the context of existing conditions of vulnerability that, together, could harm exposed people, property,

services, livelihoods, and the environment on which they depend (1).

Standard operating procedure

A complete reference document or operations manual that describes the purpose of a preferred method of performing

a single function or a number of interrelated functions in a uniform manner and provides information about the dura-

tion of the operation, the authorities of those involved and other relevant details. (6).

Surge capacity

The ability of a health service to expand beyond normal capacity to meet an increased demand for clinical care (9).

Triage

The process of categorizing and prioritizing patients with the aim of providing the best care to as many patients as

possible with the available resources (2).

Back

9

During times of disaster, hospitals play an integral role within the health-care system by providing essential medical

care to their communities. Any incident that causes loss of infrastructure or patient surge, such as a natural disaster,

terrorist act, or chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or explosive hazard, often requires a multijurisdictional and

multifunctional response and recovery effort, which must include the provision of health care. Without appropriate

emergency planning, local health systems can easily become overwhelmed in attempting to provide care during a

critical event. Limited resources, a surge in demand for medical services, and the disruption of communication and

supply lines create a significant barrier to the provision of health care. To enhance the readiness of health facilities to

cope with the challenges of a disaster, hospitals need to be prepared to initiate fundamental priority action. This docu-

ment provides an all-hazards list of key actions to be considered by hospitals in responding to any disaster event.

Hospitals are complex and potentially vulnerable institutions, dependent on external support and supply lines. In addi-

tion, with the current emphasis on cost-containment and efficiency, hospitals frequently operate at near capacity. Dur-

ing a disaster, an interruption of standard communications, external support services, or supply delivery can disrupt

essential hospital operations and even a modest unanticipated rise in admission volume can overwhelm a hospital

beyond its functional reserve. Employee attrition and shortage of critical equipment and supplies can reduce access to

needed care and occupational safety. Even for a well-prepared hospital, coping with the consequences of a disaster is

a complex challenge. Amid these challenges and demands, the systematic implementation of priority actions can help

facilitate a timely and effective hospital-based response.

In defining the all-hazards priority action required for a rapid, effective response to a critical event, this checklist aims

to support hospital managers and emergency planners in achieving the following: (1) the continuity of essential ser-

vices; (2) the well-coordinated implementation of hospital operations at every level; (3) clear and accurate internal and

external communication; (4) swift adaptation to increased demands; (5) the effective use of scarce resources; and (6) a

safe environment for health-care workers. The tool builds on previous work by the World Health Organization to assist

hospitals with pandemic management [Hospital preparedness checklist for pandemic influenza: focus on pandemic

(H1N1) 2009].

The tool is structured according to nine key components, each with a list of priority actions. Hospitals experiencing

an excessive demand for health services due to a critical event are strongly encouraged to be prepared to implement

each action effectively and as soon as it is required. The “recommended reading” listed for each component includes

selected tools, guidelines and other resources, which are considered relevant for that component.

Hospital emergency management is a continuous process requiring the seamless integration of planning and re-

sponse efforts with local and national programmes. The principles and recommendations outlined in this tool are

generic, applicable to a range of contingencies and based on an all-hazards approach. The checklist is intended to

complement existing multisectoral hospital emergency-management plans and, when possible, augment standard

operating procedures during non-crisis situations.

Introduction

Back

10

The following tool is designed to assist hospital administrators and emergency managers to

respond effectively to disasters of all types.

Health facilities experiencing an excessive demand for health services due to a disaster-re-

lated event should verify the status of implementation of each of the actions listed.

Health facilities at risk of an increase in demand for health services should be prepared to

implement each action promptly.

Hospital emergency

response checklist

An all-hazards tool for hospital administrators and emergency managers

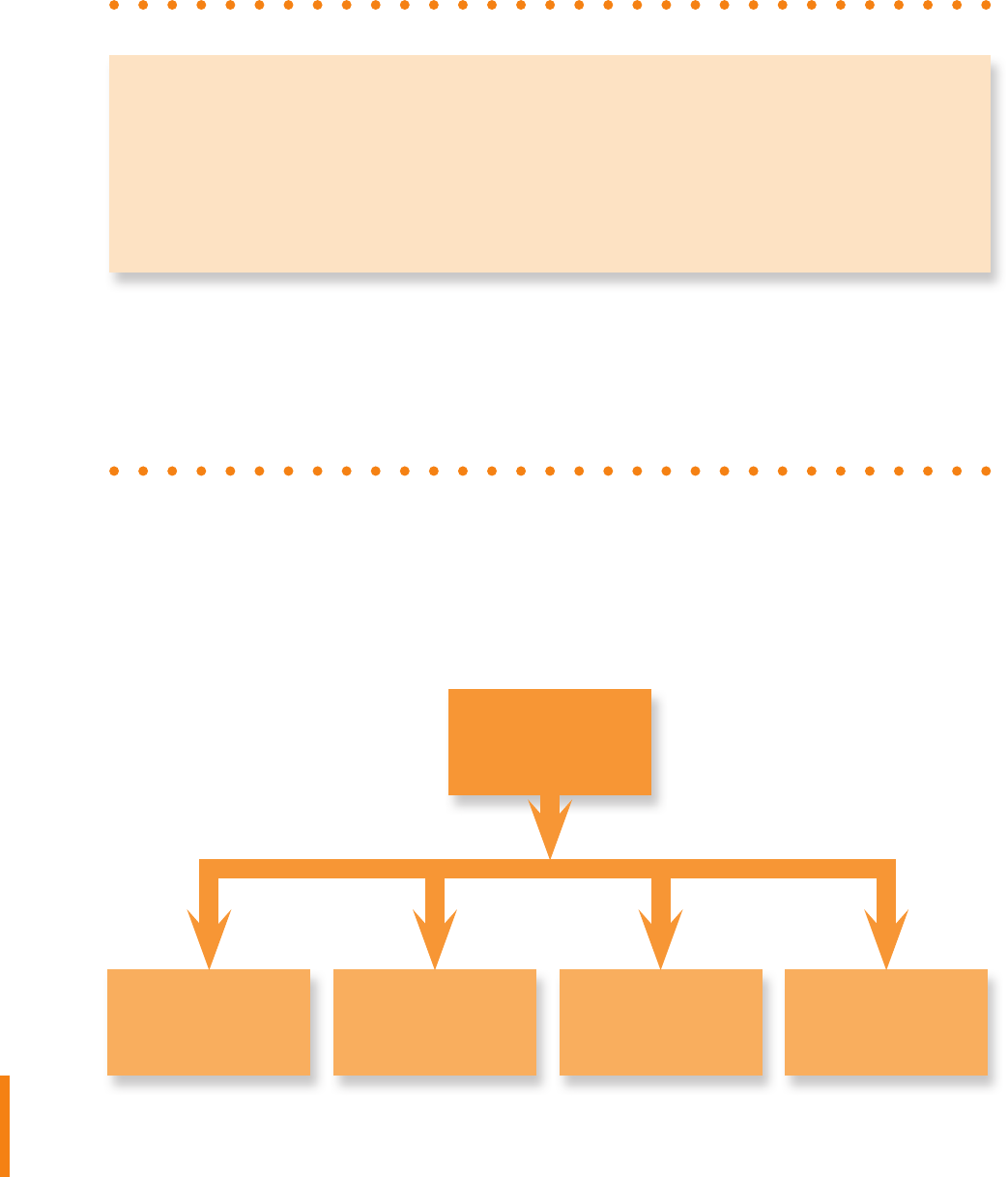

A well-functioning command-and-control system is essential for effective hospital emergency-

management operations (Fig. 1) (Recommended reading 1).

Key component 1

Command and control

Operations

Command

Planning Logistics

Finance/

Administration

Fig. 1. Organizational structure of the incident command system

Back

11

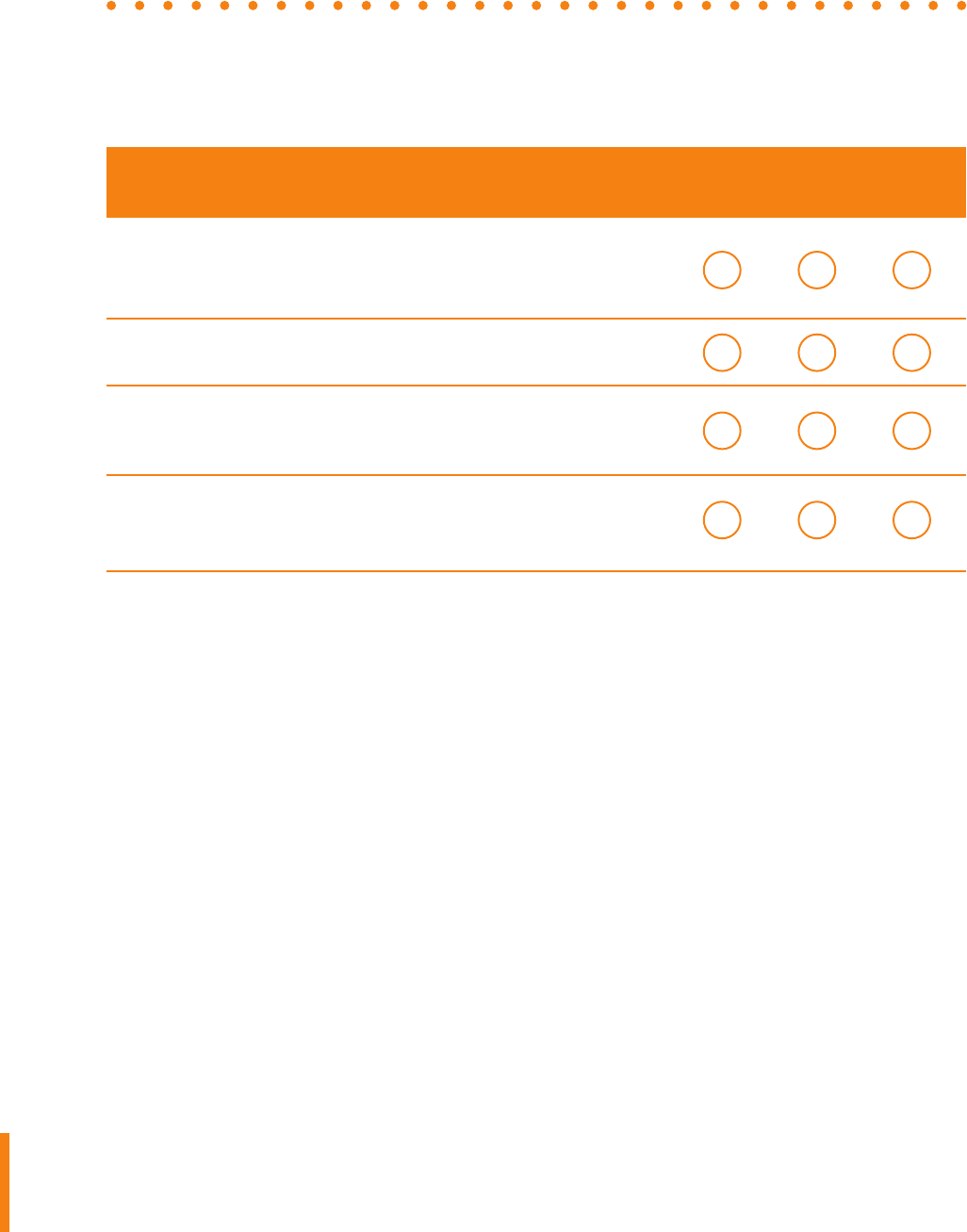

Pending In

Recommended action review progress Completed

Activate the hospital incident command group (ICG) or establish an ad hoc

ICG, i.e. a supervisory body responsible for directing hospital-based emer-

gency management operations (Box 1).

Box 1. Ad hoc hospital incident command group

If NO mechanism is in place for coordinated hospital incident management (e.g. a hospital ICG), the

hospital director should promptly convene a meeting with all heads of services in order to create an ad

hoc ICG. An ICG is essential for effective development and management of hospital-based systems

and procedures required for successful emergency response.

When organizing a hospital incident command group, consider including representatives from the following

services:

In addition, medical staff working, for example, in emergency medicine, intensive care, internal medicine or

paediatrics, should be represented.

•

hospital administration

•

communications

•

security

•

nursing administration

•

human resources

•

pharmacy

•

infection control

•

respiratory therapy

•

engineering and maintenance

•

laboratory

•

nutrition

•

l aundry, cleaning, and waste management

Due for In

Recommended action review progress Completed

Designate a hospital command centre, i.e. a specific location prepared to

convene and coordinate hospital-wide emergency response activities and

equipped with effective means of communication.

For each of the nine key components listed in this document, designate an

individual (focal point) to ensure the appropriate management and coordina-

tion of related response activities.

Designate prospective replacements for directors and focal points to guar-

antee continuity of the command-and-control structure and function.

Consult core internal and external documents (e.g. publications of the

national health authority and WHO) related to hospital emergency manage-

ment to ensure application of the basic principles and accepted strategies

related to planning and implementing a hospital incident action plan (Rec-

ommended reading 1).

Implement or develop job action sheets that briefly list the essential qualifi-

cations, duties and resources required of ICG members, hospital managers

and staff for emergency-response activities (Recommended reading 1).

Ensure that all ICG members have been adequately trained on the structure

and functions of the incident command system (ICS) and that other hospital

staff and community networks are aware of their roles within the ICS (Rec-

ommended reading 1).

Back

12

Clear, accurate and timely communication is necessary to ensure informed decision-making,

effective collaboration and cooperation, and public awareness and trust (Recommended read-

ing 2). Consider taking the following action.

Key component 2

Communication

Due for In

Recommended action review progress Completed

Appoint a public information spokesperson to coordinate hospital commu-

nication with the public, the media and health authorities.

Designate a space for press conferences (outside the immediate proxim-

ity of the emergency department, triage/waiting areas and the command

centre).

Draft brief key massages for target audiences (e.g. patients, staff, public) in

preparation for the most likely disaster scenarios.

Ensure that all communications to the public, media, staff (in general) and

health authorities are approved by the incident commander or ICG.

Establish streamlined mechanisms of information exchange between

hospital administration, department/unit heads and facility staff

(Recommended reading 2).

Brief hospital staff on their roles and responsibilities within the incident ac-

tion plan.

Establish mechanisms for the appropriate and timely collection, processing

and reporting of information to supervisory stakeholders (e.g. the govern-

ment, health authorities), and through them to neighbouring hospitals,

private practitioners and prehospital networks (Recommended reading 2).

Ensure that all decisions related to patient prioritization (e.g. adapted admis-

sion and discharge criteria, triage methods, infection prevention and control

measures) are communicated to all relevant staff and stakeholders.

Ensure the availability of reliable and sustainable primary and back-up

communication systems (e.g. satellite phones, mobile devices, landlines,

Internet connections, pagers, two-way radios, unlisted numbers), as well as

access to an updated contact list.

Back

13

Well-developed safety and security procedures are essential for the maintenance of hospital

functions and for incident response operations during a disaster (Recommended reading 3).

Consider taking the following action.

Key component 3

Safety and security

Due for In

Recommended action review progress Completed

Appoint a hospital security team responsible for all hospital safety and

security activities.

Prioritize security needs in collaboration with the hospital ICG. Identify areas

where increased vulnerability is anticipated (e.g. entry/exits, food/water ac-

cess points, pharmaceutical stockpiles).

Ensure the early control of facility access point(s), triage site(s) and other

areas of patient flow, traffic and parking. Limit visitor access as appropriate.

Establish a reliable mode of identifying authorized hospital personnel, pa-

tients and visitors.

Provide a mechanism for escorting emergency medical personnel and their

families to patient care areas.

Ensure that security measures required for safe and efficient hospital evacu-

ation are clearly defined.

Ensure that the rules for engagement in crowd control are clearly defined.

Solicit frequent input from the hospital security team with a view to identify-

ing potential safety and security challenges and constraints, including gaps

in the management of hazardous materials and the prevention and control

of infection.

Identify information insecurity risks. Implement procedures to ensure the

secure collection, storage and reporting of confidential information.

Define the threshold and procedures for integrating local law enforcement

and military in-hospital security operations.

Establish an area for radioactive, biological and chemical decontamination

and isolation (Recommended reading 3).

Back

14

Maintaining patient triage operations, on the basis of a well-functioning mass-casualty triage

protocol, is essential for the appropriate organization of patient care (Recommended reading 4).

Consider taking the following action.

Key component 4

Triage

Due for In

Recommended action review progress Completed

Designate an experienced triage officer to oversee all triage operations (e.g.

a trauma or emergency physician or a well-trained emergency nurse in a

supervisory position).

Ensure that areas for receiving patients, as well as waiting areas, are effec-

tively covered, secure from potential environmental hazards and provided

with adequate work space, lighting and access to auxiliary power.

Ensure that the triage area is in close proximity to essential personnel,

medical supplies and key care services (e.g. the emergency department,

operative suites, the intensive care unit).

Ensure that entrance and exit routes to/from the triage area are clearly

identified.

Identify a contingency site for receipt and triage

of mass-casualties.

Identify an alternative waiting area for wounded

patients able to walk.

Establish a mass-casualty triage protocol based on severity of illness/in-

jury, survivability and hospital capacity that follows internationally accepted

principles and guidelines (Recommended reading 4).

Establish a clear method of patient triage identification; ensure adequate

supply of triage tags (Recommended reading 4).

Identify a mechanism whereby the hospital emergency response plan can

be activated from the emergency department or triage site.

Ensure that adapted protocols on hospital admission, discharge, referral

and operative suite access are operational when the disaster plan is acti-

vated to facilitate efficient patient processing.

Back

15

Surge capacity – defined as the ability of a health service to expand beyond normal capacity to

meet increased demand for clinical care – is an important factor of hospital disaster response

and should be addressed early in the planning process (Recommended reading 5). Consider

taking the following action.

Key component 5

Surge capacity

Due for In

Recommended action review progress Completed

Calculate maximal capacity required for patient admission and care based not

only on total number of beds required but also on availability of human and es-

sential resources and the adaptability of facility space for critical care.

Estimate the increase in demand for hospital services, using available planning

assumptions and tools (Recommended reading 5).

Identify methods of expanding hospital inpatient capacity (taking physical

space, staff, supplies and processes into consideration).

Designate care areas for patient overflow (e.g. auditorium, lobby).

Increase hospital capacity by outsourcing the care of non-critical patients to

appropriate alternative treatment sites (e.g. outpatient departments adapted

for inpatient use, home care for low-severity illness, and chronic-care facilities

for long-term patients) (Recommended reading 5).

Verify the availability of vehicles and resources required for patient transportation.

Establish a contingency plan for interfacility patient transfer should traditional

methods of transportation become unavailable.

Identify potential gaps in the provision of medical care, with emphasis on criti-

cal and emergent surgical care. Address these gaps in coordination with the

authorities and neighbouring and network hospitals.

In coordination with the local authorities, identify additional sites that may be

converted to patient care units (e.g. convalescent homes, hotels, schools,

community centres, gyms) (Recommended reading 5).

Prioritize/cancel nonessential services (e.g. elective surgery) when necessary.

Adapt hospital admission and discharge criteria and prioritize clinical interven-

tions according to available treatment capacity and demand.

Designate an area for use as a temporary morgue. Ensure the adequate sup-

ply of body bags.

Formulate a contingency plan for post mortem care with the appropriate part-

ners (e.g. morticians, medical examiners and pathologists).

Back

16

A disaster does not remove the day-to-day requirement for essential medical and surgical services

(e.g. emergency care, urgent operations, maternal and child care) that exists under normal circum-

stances. Rather, the availability of essential services needs to continue in parallel with the activation of

a hospital emergency response plan (Recommended reading 6). Consider the taking following action.

Key component 6

Continuity of essential services

Due for In

Recommended action review progress Completed

List all hospital services, ranking them in order of priority.

Identify and maintain the essential hospital services, i.e. those that need to

be available at all times in any circumstances.

Identify the resources needed to ensure the continuity of essential hospital

services, in particular those for the critically ill and other vulnerable groups

(e.g. paediatric, elderly and disabled patients) (Recommended reading 6).

Ensure the existence of a systematic and deployable evacuation plan that

seeks to safeguard the continuity of critical care (including, for example,

access to mechanical ventilation and life-sustaining medications) (Recom-

mended reading 6).

Coordinate with the health authorities, neighbouring hospitals and private

practitioners on defining the roles and responsibilities of each member of

the local health-care network to ensure the continuous provision of essen-

tial medical services throughout the community.

Ensure the availability of appropriate back-up arrangements for essential life

lines, including water, power and oxygen.

Anticipate the impact of the most likely disaster events on hospital supplies of

food and water. Take action to ensure the availability of adequate supplies.

Ensure contingency mechanisms for the collection and disposal of human,

hazardous and other hospital waste (Recommended reading 6).

Back

17

Effective human resource management is essential to ensure adequate staff capacity and the

continuity of operations during any incident that increases the demand for human resources

(Recommended Reading 7). Consider taking the following action.

Key component 7

Human resources

Due for In

Recommended action review progress Completed

Update the hospital staff contact list.

Estimate and continuously monitor staff absenteeism.

Establish a clear staff sick-leave policy, including contingencies for ill or

injured family members or dependents of staff.

Identify the minimum needs in terms of health-care workers and other hos-

pital staff to ensure the operational sufficiency of a given hospital depart-

ment (Recommended reading 7).

Establish a contingency plan for the provision of food, water and living

space for hospital personnel.

Prioritize staffing requirements and distribute personnel accordingly.

Recruit and train additional staff (e.g. retired staff, reserve military personnel,

university affiliates/students and volunteers) according to the anticipated

need.

Address liability, insurance and temporary licensing issues relating to ad-

ditional staff and volunteers who may be required to work in areas outside

the scope of their training or for which they have no licence.

Establish a system of rapidly providing health-care workers (e.g. voluntary

medical personnel) with necessary credentials in an emergency situation, in

accordance with hospital and health authority policy.

Cross-train health-care providers in high-demand services (e.g. emergency,

surgical, and intensive care units).

Provide training and exercises in areas of potential increased clinical de-

mand, including emergency and intensive care, to ensure adequate staff

capacity and competency.

Continued on next page

Back

18

Effective human resource management is essential to ensure adequate staff capacity and the

continuity of operations during any incident that increases the demand for human resources

(Recommended Reading 7). Consider taking the following action.

Key component 7 - continued

Human resources

Due for In

Recommended action review progress Completed

Identify domestic support measures (e.g. travel, child care, care for ill or

disabled family members) to enable staff flexibility for shift reassignment and

longer working hours.

Ensure adequate shift rotation and self-care for clinical staff to support

morale and reduce medical error.

Ensure the availability of multidisciplinary psychosocial support teams that

include social workers, counsellors, interpreters and clergy for the families

of staff and patients (Recommended reading 7).

Ensure that staff dealing with epidemic-prone respiratory illness are pro-

vided with the appropriate vaccinations, in accordance with national policy

and guidelines of the health authority.

Back

19

Continuity of the hospital supply and delivery chain is often an underestimated challenge during

a disaster, requiring attentive contingency planning and response (Recommended reading 8).

Consider taking the following action.

Key component 8

Logistics and supply management

Due for In

Recommended action review progress Completed

Develop and maintain an updated inventory of all equipment, supplies and

pharmaceuticals; establish a shortage-alert mechanism.

Estimate the consumption of essential supplies and pharmaceuticals, (e.g.

amount used per week) using the most likely disaster scenarios (Recom-

mended reading 8).

Consult with authorities to ensure the continuous provision of essential

medications and supplies (e.g. those available from institutional and central

stockpiles and through emergency agreements with local suppliers and

national and international aid agencies).

Assess the quality of contingency items prior to purchase; request quality

certification if available.

Establish contingency agreements (e.g. memoranda of understanding, mu-

tual aid agreements) with vendors to ensure the procurement and prompt

delivery of equipment, supplies and other resources in times of shortage

(Recommended reading 8).

Identify physical space within the hospital for the storage and stockpiling of

additional supplies, taking ease of access, security, temperature, ventilation,

light exposure, and humidity level into consideration. Ensure an uninter-

rupted cold chain for essential items requiring refrigeration.

Stockpile essential supplies and pharmaceuticals in accordance with na-

tional guidelines. Ensure the timely use of stockpiled items to avoid loss due

to expiration.

Define the hospital pharmacy’s role in providing pharmaceuticals to patients

being treated at home or at alternative treatment sites.

Ensure that a mechanism exists for the prompt maintenance and repair

of equipment required for essential services. Postpone all non-essential

services when necessary.

Coordinate a contingency transportation strategy with prehospital networks

and transportation services to ensure continuous patient transferral.

Back

20

Post-disaster recovery planning should be performed at the onset of response activities.

Prompt implementation of recovery efforts can help mitigate a disaster’s long-term impact on

hospital operations (Recommended reading 9). Consider taking the following action.

Key component 9

Post-disaster recovery

Due for In

Recommended action review progress Completed

Appoint a disaster recovery officer responsible for overseeing hospital

recovery operations.

Determine essential criteria and processes for incident demobilization and

system recovery (Recommended reading 9).

In case of damage to a hospital building, ensure that a comprehensive

structural integrity and safety assessment is performed (Recommended

reading 9).

If evacuation is required, determine the time and resources needed to com-

plete repairs and replacements before the facility can be reopened (Recom-

mended reading 9).

Organize a team of hospital staff to carry out a post-action hospital invento-

ry assessment; team members should include staff familiar with the location

and inventory of equipment and supplies. Consider including equipment

vendors to assess the status of sophisticated equipment that may need to

be repaired or replaced (Recommended reading 9).

Provide a post-action report to hospital administration, emergency man-

agers and appropriate stakeholders that includes an incident summary, a

response assessment, and an expenses report.

Organize professionally conducted debriefing for staff within 24–72 hours

after the occurrence of the emergency incident to assist with coping and

recovery, provide access to mental health resources and improve work

performance.

Establish a post-disaster employee recovery assistance programme ac-

cording to staff needs, including, for example, counselling and family sup-

port services.

Show appropriate recognition of the services provided by staff, volunteers,

external personnel and donors during disaster response and recovery.

Back

21

1. UNISDR terminology on disaster risk reduction. Geneva, United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Re-

duction, 2009 (http://www.unisdr.org/eng/library/lib-terminology-eng%20home.htm, accessed 28 May 2011).

2. A practical tool for the preparation of a hospital crisis preparedness plan, with special focus on pandemic influ-

enza. 2nd edition. Copenhagen, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2007 (http://www.euro.

who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/90498/E89763.pdf, accessed 28 May 2011).

3. Internationally agreed glossary of basic terms related to disaster management. Geneva, United Nations Depart-

ment of Humanitarian Affairs, 1992 (http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/004DFD3E15B69A67C1

256C4C006225C2-dha-glossary-1992.pdf, accessed 28 May 2011).

4. Medical surge capacity and capability. A management system for integrating medical and health resources during

large-scale emergencies. Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007 (http://www.

phe.gov/preparedness/planning/mscc/handbook/pages/default.aspx, accessed 28 May 2011).

5. Oxford English dictionary, 2nd edition. New York, Oxford University Press, 1989.

6. National Incident Management Resource Center [web site]. Washington, D.C., Federal Emergency Management

Agency, 2011 (http://www.fema.gov/emergency/nims/Glossary.shtm#S, accessed 28 May 2011).

7. A dictionary of epidemiology, 4th edition. New York, Oxford University Press, 2001.

8. Mass casualty management systems. Strategies and guidelines for building health sector capacity. Geneva,

World Health Organization, 2007 (http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/MCM_guidelines_inside_final.pdf, ac-

cessed 28 May 2011).

9. Pandemic flu. Managing demand and capacity in health care organizations. (Surge) London, Department

of Health, 2009 (http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/

dh_098750.pdf, accessed 28 May 2011).

References

Back

22

1. Command and control

Establishing a mass casualty management system. Washington, D.C., Pan American Health Organization, 1995

(http://publications.paho.org/product.php?productid=644, accessed 29May 2011).

Guide for all-hazards emergency operations planning. Washington, D.C., Federal Emergency Management Agency,

1996 (http://www.fema.gov/pdf/plan/slg101.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Hospital incident command system guidebook. Sacramento, California Emergency Medical Services Authority, 2004

(http://www.emsa.ca.gov/HICS/files/Guidebook_Glossary.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

National incident management system. Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2008 (http://www.

fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nims/NIMS_core.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

2. Communication

Creating a communication strategy for pandemic influenza. Washington, D.C., Pan American Health Organization,

2009 (http://www.paho.org/English/AD/PAHO_CommStrategy_Eng.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Effective media communication during public health emergencies: a WHO handbook. Geneva, World Health Organiza-

tion, 2005 (http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/WHO%20MEDIA%20HANDBOOK.pdf, accessed 29 May

2011).

Effective media communication during public health emergencies: a WHO Field Guide. Geneva, World Health Organi-

zation, 2005 (http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/WHO%20MEDIA%20FIELD%20GUIDE.pdf, accessed 29

May 2011).

Effective media communication during public health emergencies: a WHO Wall Chart. Geneva, World Health Organi-

zation, 2005 (http://www.who.int/entity/csr/resources/publications/WHO%20MEDIA%20HANDBOOK%20WALL%20

CHART.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

World Health Organization outbreak communication planning guide. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2008 (http://

www.who.int/ihr/elibrary/WHOOutbreakCommsPlanngGuide.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

3. Safety and security

American Hospital Association chemical and bioterrorism preparedness checklist. Washington, D.C., American Hospi-

tal Association (www.aha.org/aha/content/2001/pdf/MaAtChecklistB1003.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Emergency preparedness checklist: recommended tool for effective health care facility planning. Baltimore, Centers

for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2009 (https://www.cms.gov/SurveyCertEmergPrep/downloads/S&C_EPCheck-

list_Provider.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Guidelines for vulnerability reduction in the design of new health facilities. Washington, D.C., Pan American Health

Organization, 2004 (http://www.paho.org/english/dd/ped/vulnerabilidad.htm, accessed 29 May 2011).

Hospitals safe from disasters: reduce risk, protect health facilities, save lives. Geneva, United Nations International

Strategy for Disaster Reduction, 2008 (http://www.unisdr.org/eng/public_aware/world_camp/2008-2009/iddr-

2008/2008-iddr.htm, accessed 29 May 2011).

Hospital safety index. Guide for evaluators. Washington, D.C., Pan American Health Organization, 2008 (http://www.

paho.org/english/dd/ped/SafeHosEvaluatorGuideEng.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Recommended reading

Back

23

Preparedness for chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosive events: Questionnaire for health care facili-

ties. Rockville, Agency for Health care Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2007

(www.ahrq.gov/prep/cbrne/cbrneqadmin.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Safe hospitals. A collective responsibility. A global measure of disaster reduction. Washington, D.C., Pan American

Health Organization, 2006 (http://www.paho.org/English/dd/Ped/SafeHospitals.htm, accessed 29 May 2011.

4. Triage

Challen K et al. Clinical review: mass casualty triage – pandemic influenza and critical care, Critical Care, 2007,

11(2):212. (http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2206465, accessed 29 May 2011).

Emergency triage assessment and treatment (ETAT). Manual for participants. Geneva, World Health Organization,

2005 (http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2005/9241546875_eng.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Koenig KL, Schultz CH, eds. Koenig and Schultz’s disaster medicine: comprehensive principles and practices. New

York, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Lerner EB et al. Mass casualty triage: an evaluation of the data and development of a proposed national guideline.

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2008, 2(1):25–34.

5. Surge capacity

Alternative care site selection matrix tool. In: Cantrill SV, Eisert SL, Pons P et al. Rocky Mountain Regional Care Model

for Bioterrorist Events: Locate Alternate Care Sites During an Emergency. AHRQ Publication No. 04-0075, Rockville,

Agency for Health care Research and Quality, Rockville, 2004 (http://www.ahrq.gov/research/altsites/ accessed 29

May 2011).

Disaster alternative care facilities: selection and operation. Rockville, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Agency for Health care Research and Quality, 2010 (http://www.ahrq.gov/prep/acfselection/dacfrep.htm, accessed 29

May 2011).

Donald IP et al. Defining the appropriate use of community hospital beds. British Journal of General Practice, 2001,

1(463):95–100 (http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1313942, accessed 29 May 2011).

Field manual for capacity assessment of health facilities in responding to emergencies. Manila, World Health Organi-

zation Regional Office for the Western Pacific, 2006 (http://www.wpro.who.int/publications/PUB_9290612169.htm,

accessed 7 June 2011).

Hospital surge model. Rockville, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Health care Research

and Quality, 2010 (http://www.ahrq.gov/prep/hospsurgemodel, accessed 29 May 2011).

Kelen GD et al. Inpatient disposition classification for the creation of hospital surge capacity: a multiphase study. Lan-

cet, 2006, 368(9551):1984–90.

Kraus CK, Levy F, Kelen GD. Lifeboat ethics: considerations in the discharge of inpatients for the creation of hospital

surge capacity. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2007, 1(1):51–6.

Medical surge capacity and capability: a management system for integrating medical and health resources during

large-scale emergencies. Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007 (http://www.phe.

gov/Preparedness/planning/mscc/handbook/Documents/mscc080626.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Smith HE et al. Appropriateness of acute medical admissions and length of stay. Journal of the Royal College of Physi-

cians, 1997, 31(5):527–32 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9429190, accessed 29 May 2011).

Back

24

Surge hospitals: providing safe care in emergencies. Washington, D.C., Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health

care Organizations, 2006 (http://www.premierinc.com/safety/topics/disaster_readiness/downloads/surge-hospitals-

jcr-12-08-05.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

6. Continuity of essential services

Care and resource utilization: ensuring appropriateness of care. London, Department of Health, 2006 (http://www.

dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_063265, accessed 29 May

2011).

Media Centre [web site]. Health-care waste management (fact sheet no. 281). Geneva, World Health Organization,

2004 (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs281/en/index.html, accessed 29 May 2011).

Hospital evacuation decision guide. Rockville, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Health care

Research and Quality, 2010 (http://www.ahrq.gov/prep/hospevacguide, accessed 29 May 2011).

Mass casualty disaster plan checklist: a template for health care facilities. St. Louis, Center for the Study of Bioterror-

ism and Emerging Infections (www.bioterrorism.slu.edu/bt/quick/disasterplan.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Mass casualty management systems: strategies and guidelines for building health sector capacity. Geneva, World

Health Organization, 2007 (http://www.who.int/entity/hac/techguidance/MCM_guidelines_inside_final.pdf, accessed

29 May 2011).

Wisner B, Adams J, eds. Environmental health in emergencies and disasters: a practical guide. Geneva, World Health

Organization, 2003 (http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/hygiene/emergencies/emergencies2002/en/, ac-

cessed 29 May 2011).

7. Human resources

Human resources for health action framework [web site]. Chapel Hill, The Capacity Project, 2011 (http://www.capaci-

typroject.org/framework/, accessed 29 May 2011).

Human resource management rapid assessment tool for public- and private-sector health organizations. A guide for

strengthening HRM systems. Cambridge, Management Sciences for Health, 2005 (http://erc.msh.org/toolkit/toolkit-

files/file/English1.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Geneva, Inter-agency Standing

Committee, 2007 (http://www.who.int/hac/network/interagency/news/mental_health_guidelines/en, updated 29 May

2011).

Toolkit: resources to help managers who lead. In: Miller J, Bahamon C, Timmons NK, eds. Managers who lead: a

handbook for improving health services. Cambridge, Management Sciences for Health, 2005:173–270 (http://www.

msh.org/Documents/upload/MWL-2008-edition.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Mental health in emergencies. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2003 (http://www.who.int/mental_health/media/

en/640.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Recommended hospital staff core competencies for disaster preparedness. Tallahassee, Florida State Hospital Core

Competency Sub Committee and Health, Medical, Hospital, and EMS Committee Working Group, 2004 (http://www.

emlrc.org/pdfs/disaster2005presentations/HospitalDisasterMgmtCoreCompetencies.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Back

25

8. Logistics and supply management

Handbook of supply management at first-level health care facilities. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2006 (http://

www.who.int/management/resources/procurement/handbookforsupplymanagement.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Humanitarian supply management and logistics in the health sector. Washington, Pan American Health Organization,

2001 (http://www.paho.org/English/Ped/supplies.htm, accessed 29 May 2011).

Mutual aid agreements and assistance agreements. Washington, U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency

(http://www.fema.gov/emergency/nims/Preparedness.shtm#item2, accessed 29 May 2011).

WHO model list of essential medicines. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2009 (http://www.who.int/selection_med-

icines/committees/expert/17/sixteenth_adult_list_en.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

9. Post-disaster recovery

Analysing disrupted health sectors –- a modular manual. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2009 (http://www.who.

int/hac/techguidance/tools/disrupted_sectors/adhsm_en.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Hospital assessment and recovery guide. Rockville, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Agency for

Health care Research and Quality, 2010 (http://www.ahrq.gov/prep/hosprecovery/hosprec2.htm, accessed 29 May

2011).

Guidance for health sector assessment to support the post-disaster recovery process. Version 2.2. Geneva, World

Health Organization, 2010 (http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/tools/manuals/pdna_health_sector_guidance/en/

index.html, accessed 29 May 2011).

10. Other

Health care at the crossroads: strategies for creating and sustaining community-wide emergency preparedness sys-

tems. Oakbrook Terrace, Joint Commission of Accreditation of Health care Organizations, 2003 (http://www.jointcom-

mission.org/assets/1/18/emergency_preparedness.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Hospital preparedness checklist for pandemic influenza: focus on pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Copenhagen, World Health

Organization for Europe, 2009 (http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/78988/E93006.pdf, accessed

29 May 2011).

Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in disaster response. Geneva, The Sphere Project, 2004 (http://www.

sphereproject.org/content/view/27/84/lang,English/, accessed 29 May 2011).

Standing together: an emergency planning guide for America’s communities. Oakbrook Terrace, Joint Commission

of Accreditation of Health care Organizations, 2005 (http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/FE29E7D3-22AA-

4DEB-94B2-5E8D507F92D1/0/planning_guide.pdf, accessed 29 May 2011).

Back

World Health Organization

Regional Office for Europe

Scherfigsvej 8, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark

Tel.: +45 39 17 17 17. Fax: +45 39 17 18 18.

E-mail: [email protected]

Web site: www.euro.who.int

The WHO Regional

Ofce for Europe

The World Health Organization (WHO)

is a specialized agency of the United

Nations created in 1948 with the primary

responsibility for international health

matters and public health. The WHO

Regional Ofce for Europe is one of six

regional ofces throughout the world,

each with its own programme geared

to the particular health conditions of the

countries it serves.

Member States

Albania

Andorra

Armenia

Austria

Azerbaijan

Belarus

Belgium

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bulgaria

Croatia

Cyprus

Czech Republic (the)

Denmark

Estonia

Finland

France

Georgia

Germany

Greece

Hungary

Iceland

Ireland

Israel

Italy

Kazakhstan

Kyrgyzstan

Latvia

Lithuania

Luxembourg

Malta

Monaco

Montenegro

Netherlands

Norway

Poland

Portugal

Republic of Moldova

Romania

Russian Federation (the)

San Marino

Serbia

Slovakia

Slovenia

Spain

Sweden

Switzerland

Tajikistan

The former Yugoslav

Republic of Macedonia

Turkey

Turkmenistan

Ukraine

United Kingdom (the)

Uzbekistan

Original: English

Hospital emergency response checklist

An all-hazards tool for hospital administrators

and emergency managers