i

THE COMMUNITY

DEVELOPMENT

GRADUATE GROUP

Handbook and Reference Guide

2020-2021

0

Table of Contents

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT GRADUATE GROUP ...............................................................................2

PURPOSE AND VISION .............................................................................................................................2

GRADUATE GROUP STRUCTURE .................................................................................................................2

WHO IS MY FACULTY ADVISOR? ................................................................................................................3

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT GRADUATE GROUP KEY PERSONNEL .....................................................................4

GRADUATE ADVISORS ........................................................................................................................................ 4

GRADUATE GROUP GOVERNING COMMITTEES AND OFFICERS ................................................................................... 4

CORE STAFF PEOPLE ........................................................................................................................................... 4

II. PLANS OF STUDY & OTHER REQUIREMENTS .................................................................................. 11

PLAN I. THESIS AND THESIS PROJECT OPTION + THESIS DEFENSE ..................................................................... 11

PLAN II. WRITTEN COMPREHENSIVE EXAM + ORALS OPTION ......................................................................... 14

INTERNSHIP REQUIREMENT..................................................................................................................... 15

FILING FEE STATUS ............................................................................................................................... 16

GRADUATION ...................................................................................................................................... 16

CORE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT COURSES (REQUIRED) .............................................................................. 16

METHODOLOGY (REQUIRED) .................................................................................................................. 17

CORE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT COURSES (ELECTIVES) .............................................................................. 18

INTERNSHIP/TA/RESEARCH COURSES ....................................................................................................... 21

THESIS PROPOSAL GUIDELINES ................................................................................................................ 22

THE PROPOSAL................................................................................................................................................ 22

INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD ......................................................................................................................... 23

THE THESIS PROJECT OPTION .................................................................................................................. 24

THE DEFENSE .................................................................................................................................................. 24

SUBMITTING AN ELECTRONIC COPY OF YOUR THESIS ............................................................................................. 24

KEY MILESTONES TO COMPLETING THE M.S. IN 2 YEARS ............................................................................... 25

III. RESOURCES ................................................................................................................................. 27

LOANS, GRANTS, AND FELLOWSHIPS ......................................................................................................... 27

THE ERNA AND ORVILLE THOMPSON GRADUATE STUDENT FUND..................................................................... 27

GRADUATE RESEARCH ASSISTANT – WORK-STUDY ....................................................................................... 27

1

TAS AND READERS ............................................................................................................................... 28

THE CENTER FOR EDUCATIONAL EFFECTIVENESS (CEE) .......................................................................................... 28

THE UC DAVIS CENTER FOR REGIONAL CHANGE .......................................................................................... 29

GETTING BY, GETTING AROUND .............................................................................................................. 30

OTHER RESOURCES ............................................................................................................................... 31

CALIFORNIA STATE LIBRARY ............................................................................................................................... 31

IV. FORMS ....................................................................................................................................... 32

MASTER OF SCIENCE PROGRAM IN COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT ....................................................... 33

SELECTION OF PERMANENT ADVISOR ............................................................................................... 36

CHANGE OF GRADUATE ADVISOR ..................................................................................................... 37

APPOINTMENT OF MASTER’S THESIS COMMITTEE ............................................................................. 38

REPORT ON INTERNSHIP ................................................................................................................... 39

ADVISOR’S REPORT ON MASTERS THESIS PROPOSAL DEFENSE ........................................................... 40

2018-19 GRADUATION/DEGREE DEADLINES FOR MASTER’S STUDENTS ............................................................ 41

V. APPENDICES ................................................................................................................................ 42

APPENDIX I: ........................................................................................................................................ 43

GUIDELINES FOR AWARDING ACADEMIC CREDIT FOR COURSEWORK REQUIRING CONTRACTS ....................................... 43

APPENDIX II: ....................................................................................................................................... 44

HOW TO SELECT A FACULTY SPONSOR FOR INTERNSHIPS ........................................................................................ 44

APPENDIX III: ...................................................................................................................................... 45

STRUCTURE FOR CDGG INTERNSHIPS ................................................................................................................. 45

APPENDIX IV: ..................................................................................................................................... 47

ELECTIVE COURSES OFTEN TAKEN (AND ENJOYED) BY CDGG STUDENTS ................................................................... 47

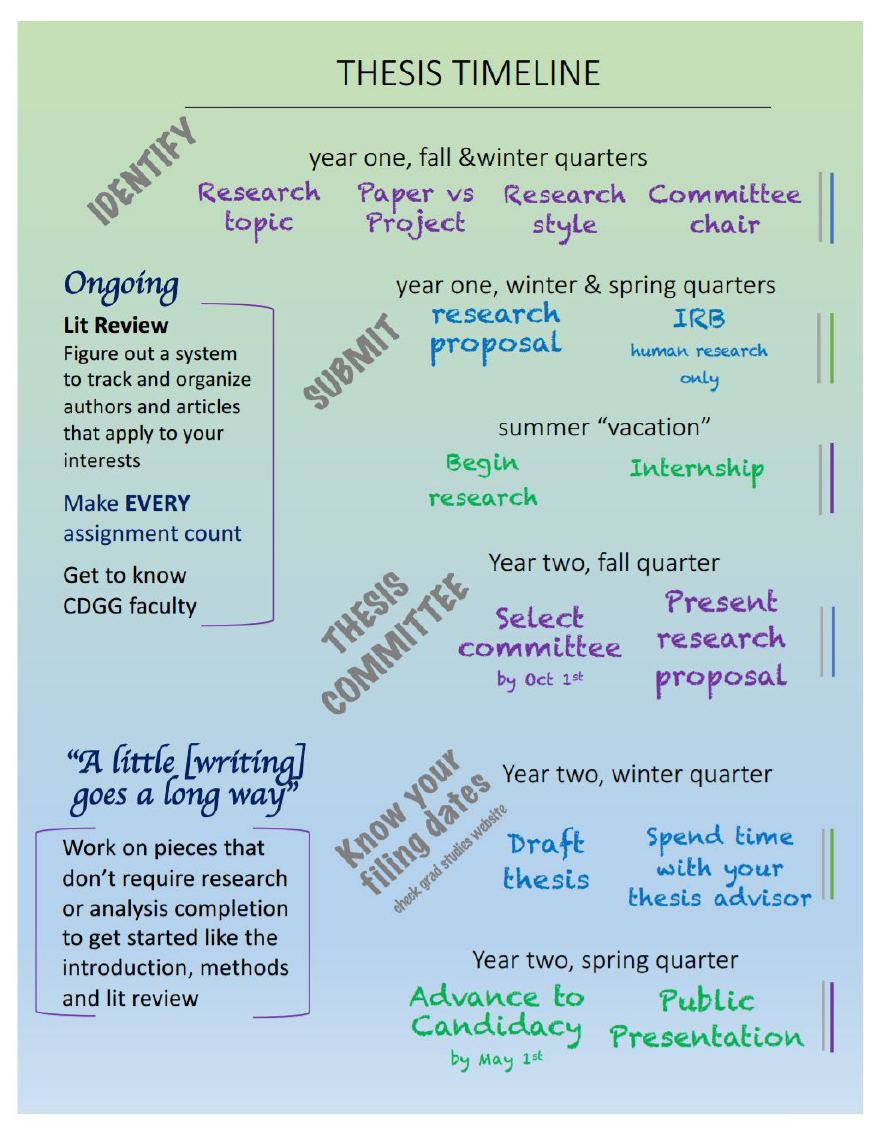

THE STRATEGY FOR A TWO-YEAR THESIS ............................................................................................................. 49

APPENDIX VII:..................................................................................................................................... 50

HOW TO BE AN ADVISEE AND MANAGING YOUR ADVISOR...................................................................................... 50

APPENDIX VIII:.................................................................................................................................... 55

GRADUATE STUDENT GUIDE FOR MANAGING UCD EXPENSES ......................................................................... 55

2

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT GRADUATE GROUP

Purpose and Vision

The CDGG is a community of transformative thinkers building knowledge useful to meet local community

goals in the context of regional, national and global change. The program emphasizes interdisciplinary,

collaborative, and project-based learning, as well as community-engaged scholarship. The CDGG challenges

students to integrate theory and practice, to develop constructive solutions to contemporary problems, and

to lead in building a healthy, sustainable, and equitable society. For more than 40 years the Community

Development Graduate Group has combined social theory and scientific research with the acquisition of

practitioner skills. In our program, we aim to integrate learning, action, and reflection with these goals.

Understand the history of community development and apply theory related to the field

Work with institutions and systems of power within communities

Engage and collaborate with different communities of place, practice, and interest

Build upon community assets and uniqueness to identify constructive solutions

Develop skills and knowledge related to their particular interests

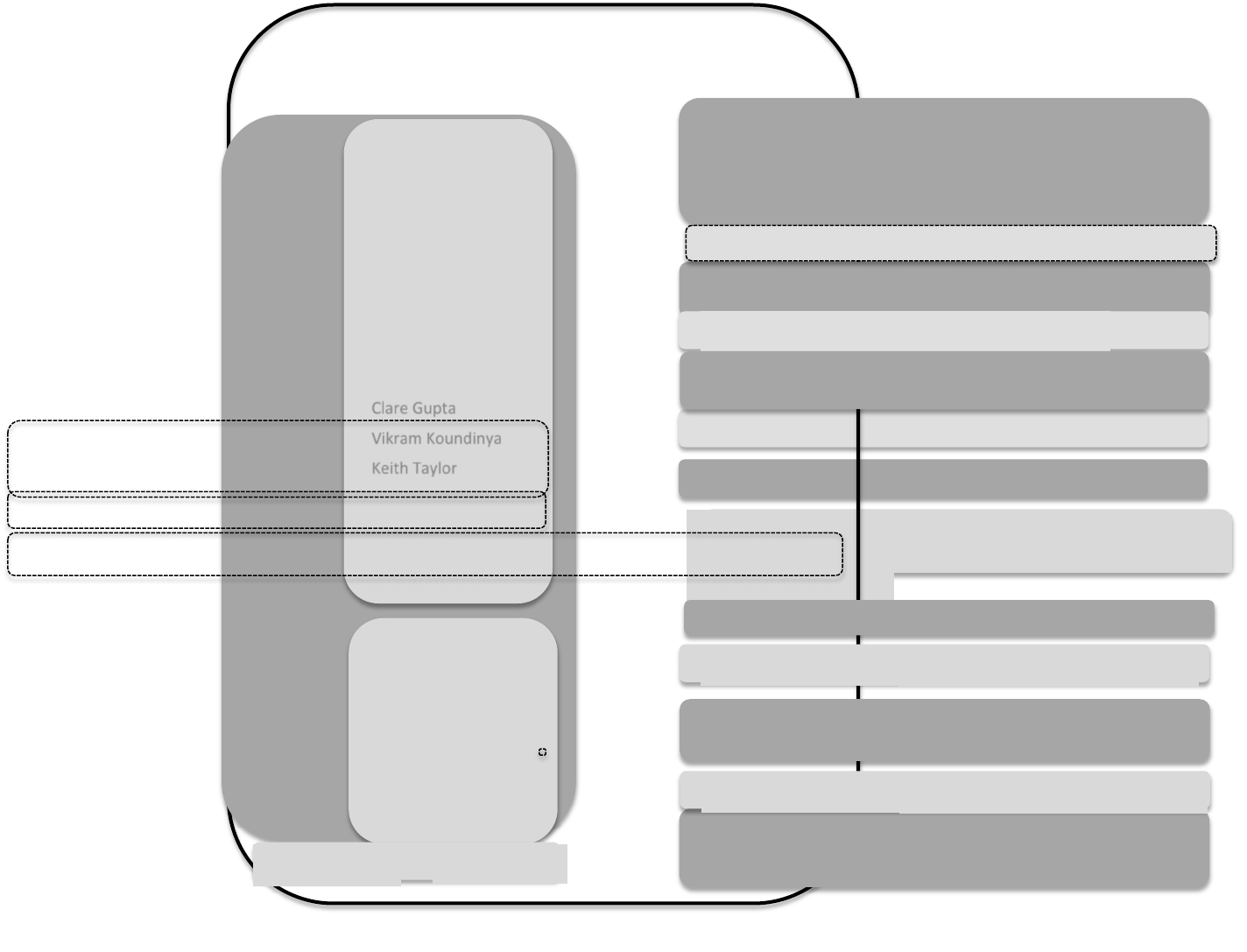

Graduate Group Structure

Welcome to the Community Development Graduate Group! Here’s a breakdown of where you are in the

structure of UC Davis. The university has three undergraduate colleges: (1) Letters and Science, (2)

Engineering, and (3) Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. Cutting across those three colleges is Graduate

Studies, which administers over 80 graduate programs offered by departments and groups within the three

colleges.

The Community Development Graduate Program is sponsored by the Community Development Graduate

Group (CDGG), which has its administrative and financial center in the Community and Regional Development

Program (CRD). CRD is a unit of the Department of Human Ecology, which is in the College of Agriculture and

Environmental Sciences. The Chair of the CDGG is Stephen Wheeler, a Professor in the Landscape Architecture

+ Environmental Design Program (LDA) in the Department of Human Ecology.

There are two types of graduate programs on campus: those directly sponsored by departments and those

sponsored by graduate groups. The CDGG falls in the latter category. About half of all graduate programs

(80+) on campus are sponsored by graduate groups. The primary benefit of the group structure is that it

“permits faculty to be affiliated with graduate programs in more than one discipline and offers students

flexibility and breadth by crossing the administrative boundaries of the various departments, colleges,

schools and sometimes campuses.” The flexibility is very helpful in that it allows students to create their own

paths as much as possible. At the same time, it gives students the sole responsibility of defining their

individual programs. Those students who apply to CDGG tend to be independently driven folks already, but

the task can be daunting (especially at first).

A little confusing, right? What does this mean to you? Knowing the University’s structure can help you figure

3

out who has power to do what, and where to get information. For most CDGG student needs, the program’s

staff advisor (Carrie Armstrong-Ruport), the program’s chair, and your own faculty advisor are the people to

start with.

Who is My Faculty Advisor?

Graduate Council recognizes that the mentoring of graduate students by faculty is an integral part of the

graduate experience for both. Faculty mentoring is broader than advising a student on the program of study

to fulfill coursework requirements and is distinct from formal instruction in a given discipline. Mentoring

encompasses more than serving as a role model. While the faculty advisor will be the primary mentor during

a student’s career at UCD, program faculty other than the student’s advisor may perform many of the

mentoring functions.

Mentoring has been defined as: (1) Providing a clear map of program requirements from the beginning,

making clear the nature of the coursework requirements and qualifying examination, and defining a timeline

for their completion; and (2) Providing clear guidelines for starting and finishing thesis work, including

encouraging the timely initiation of thesis research. Beyond these general expectations of faculty advising,

there are specific advisee requirements of all entering students in Community Development. Two important

steps, outlined below, include meeting with your initial advisor before classes begin and selecting a

permanent advisor before completing your first year. Additional milestones are outlined on p. 21 of this

handbook.

As an incoming student, you will be paired with an initial faculty advisor. The goal of assigning you this

advisor is to provide you with an initial point of contact and get oriented to faculty and resources on campus

in your area of interest. This is a temporary assignment so you will need to choose a permanent advisor by

the end of the first year. At the beginning of the school year, 1

st

year students are required to meet with their

assigned advisor to: (1) discuss and review your list of proposed courses for the year, (2) discuss the

alternative plans of study (Plan I: Thesis Option and Plan II: Comprehensive Exam Option), and (3) Discuss

upcoming deadlines and milestones for the 1

st

year of study. During this meeting, the Degree Requirements

Planner (see p. 28) will need to be signed by your advisor followed by a signature from the CDGG Chair.

Before the end of your first year, you are required to select a permanent advisor that will also serve as your

thesis or exam chair, depending on your chosen plan of study. This is often the same person as your initial

advisor, as every effort is made to pair faculty and students that share research interests. The permanent

advisor will sign your progress report as well as continuing to review and guide your plan of study. In terms of

mentoring, the advisor will assist you in choosing remaining courses to complement your research interests

and guide independent studies related to your thesis topic/professional interests. The advisor will also

provide suggestions concerning the composition of your thesis or exam committee as well as on-going review

of thesis work and necessary steps toward graduation. However, it is worth noting that any forms requiring

signature from the Office of Graduate Studies will need to be signed by one of the “Graduate Advisors” listed

in the next section.

4

Community Development Graduate Group Key Personnel

Graduate Advisors

(These are the people authorized to sign student forms)

Stephen Wheeler, Human Ecology, chair and advisor, 165 Hunt Hall, (530) 754-9332,

Natalia Deeb-Sossa, Chicana and Chicano Studies, advisor, 2105 Hart Hall, (530) 752-2421,

Claire Napawan, Human Ecology, advisor, 131 Hunt Hall, (530) 752-3907,

Amanda Crump, Plant Sciences, advisor, 3045 Wickson Hall, (530)754-0903,

Graduate Group Governing Committees and Officers

Executive Committee: Makes decisions about program requirements and nominates

new faculty members to be voted upon by the CDGG—graduate students nominate new

student members. Current members are: Natalia Deeb Sossa, Catherine Brinkley, David de la

Pena, Stephen Wheeler, and Jonathan London. Usually a student from each of the first and

second year cohorts serves on the committee as well.

Admissions Committee: Reviews Community Development applications to the

program and makes decisions on admissions, fellowships and work-study awards.

Curriculum Committee: convenes as needed. Reviews the classes and makes

recommendations to Grad Studies regarding class content, seminars and colloquium. In

recent years, the Executive Committee has also served as the Curriculum Committee.

Core Staff People

You can find the Graduate Program Coordinator, Carrie Armstrong-Ruport, in Room 129 Hunt Hall (530) 752-

4119 – [email protected]

. She is the first point of contact for all graduate students and the graduate

program. She has records of transcripts and grades, assists with forms and communication between

departments, provides translation of the UC policies, and can offer tips and direction for daily survival on

campus. Carrie sends out a plethora of announcements regarding jobs, classes, and messages from faculty.

She also keeps track of Teaching Assistant and Reader positions for the department, and can help match

students up with these on-campus work opportunities.

5

Carrie assists with internships by keeping in regular contact with certain organizations that have had interns

in the past. She can give tips or suggestions about possibilities that fit students’ interests. You should also talk

with your initial or permanent faculty advisor about possible internships. Please see Appendix 1: Academic

Guidelines for Awarding Academic Coursework Requiring Contracts (p. 37); and Appendix 3: The Rationale

and Structure for Internships (p. 39). If you have any leads for new internship opportunities, we urge you to

let Carrie know this so that she can let other students know and enter the information into her data bank.

Carrie can broadcast these opportunities on our student listserv.

The administration of the Community Development Graduate Group is handled within an administrative

cluster (called Cluster 5) that includes the departments of Environmental Science and Policy, Agricultural and

Resource Economics, and Human Ecology. In nearly all cases, your first point of contact for any

administrative matters should be Carrie Armstrong-Ruport, but at times you may end up interacting with

other administrative support staff, particularly related to TA and GSR hiring paperwork and payroll

submissions, for information technology support, and for office keys, so it is useful to know who they are.

They are all essential and valued staff for ensuring our program and departments continue to thrive. Full

contact information is on the website at: http://caes-cluster5.ucdavis.edu

.

6

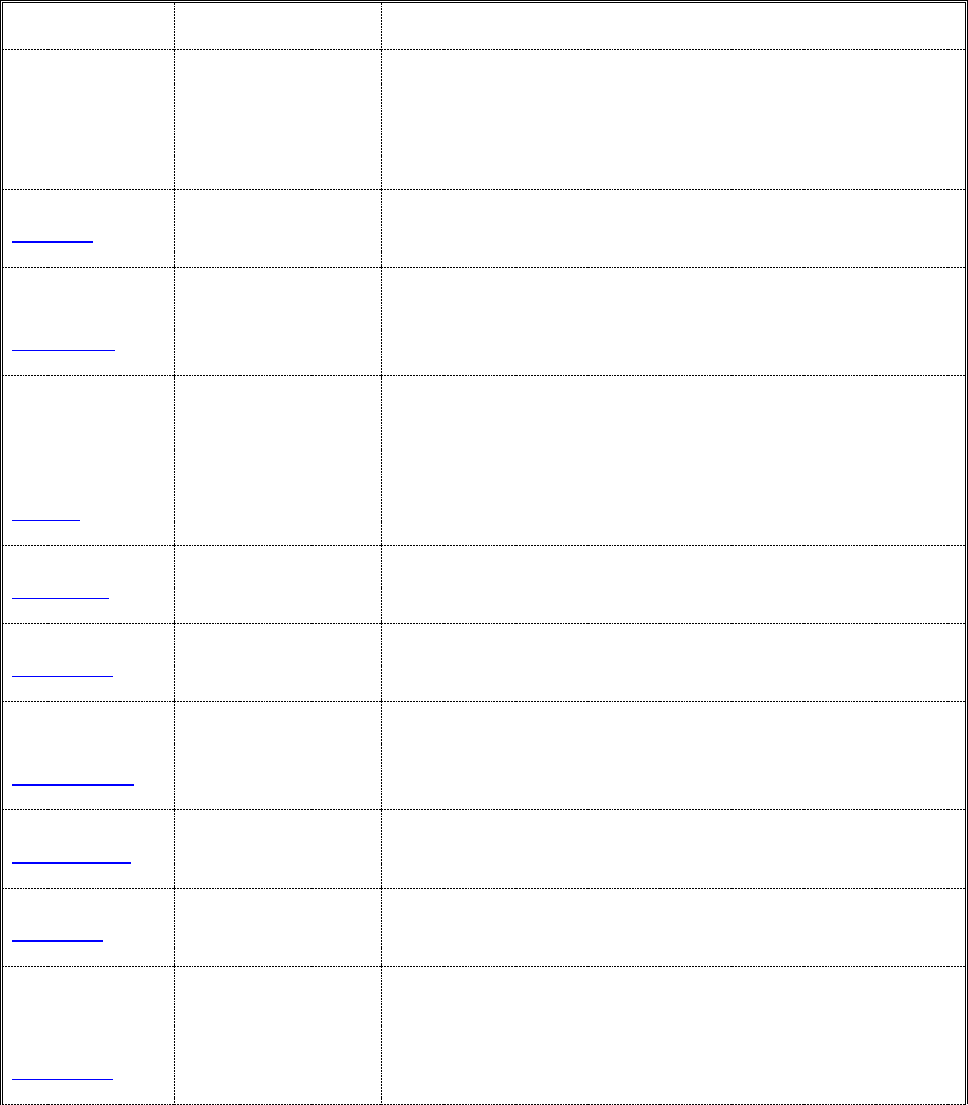

Jesus Barajas

Susan Handy

Tom Tomich

Environmental Science and Policy

Liza Grandia

Beth Rose Middleton

Native American Studies

Natalia Deeb-Sossa

Yvette Flores

Carlos Jackson

Susy Zepeda

Chicana/o Studies

Sociology

Bruce Haynes

David Kyle

Diane Wolf

School of Education

Heidi Ballard

Jesse Drew

Cinema and Digital Studies

Lisa Pruitt

Dept. of

Human

Ecology

Amanda Crump Plant Sciences

Susan Kaiser

Textiles & Clothing

School of Law

Gail Feenstra

Sustainable Ag. Research & Edu. Program

Community Development Graduate Group

CRD

Eric Chu

Martin Kenney

Anne Visser

Catherine Brinkley

Clare Cannon

Noli Brazil

Mark Cooper

William Lacy

Cooperative Extension

Agr Sustainability Inst

Center for Regional Change

Clare Gupta

Vikram Koundinya

Keith Taylor

Jonathan London

Ryan Galt

LDA

David de la Pena

Haven Kiers

Patsy E. Owens

Claire Napawan

Michael Rios

Brett Milligan

Stephen Wheeler

Last update: August 2019

Bettina Ng’weno

African American and African Studies

Julie Sze, Javier Arbona,

Erica Kohl-Arenas

American Studies

Robin Hill

Art

Glenda Drew

Design

7

CDGG Faculty Members

Name

Department

Areas of Interest

Javier Arbona American Studies

Race, space, memory, military landscapes, policing, surveillance, and

global infrastructure

Heidi Ballard Education

Environmental education that links communities, science,

environmental action and learners of all ages.

Jesus Barajas

Environmental Science

& Policy

Studies environmental justice and transportation equity. His work

examines the role planning and policy contributes to access to

opportunity among historically marginalized populations, with a goal

of informing policy agendas that remedy injustices. He has published

on sustainable travel among immigrants, bicycle and pedestrian

safety, and cross-cutting issues in transportation and education

equity.

Noli Brazil Human Ecology

My research focuses on several areas of inquiry linked by an interest

in spatial demography, or more broadly, the connections between

people and places.

Catherine Brinkley Human Ecology

Community Food: Healthy Food Access, Farm-City Networks, One

Health; Community Energy: On-Farm Clean Energy Solutions,

Sustainable Development

Clare Cannon Human Ecology

Political economy and the environment, global and urban

sustainability, gender and society, climate change and disasters, and

mixed-methodologies.

Eric Chu Human Ecology

I study how local governments and communities plan for and adapt

to the impacts of global environmental change. My research is

globally comparative and draws on qualitative, participatory, and

policy design methodologies. Theoretically, I specialize in issues of

local governance, environmental politics, and social inclusion/justice.

Mark Cooper Human Ecology

The role of technological and social innovations in the

decarbonization of the meat & dairy sectors and the plastics

industry; The policy and politics of greenhouse gas mitigation in

California and New Zealand; The geography of field-based scientific

research and the role of space, site, and scale in research design and

research practice.; The development and use of particular measures

8

Name

Department

Areas of Interest

and metrics in private-sector animal welfare standards and

government regulations.

Amanda Crump

Plant Sciences

I focus my research on international and domestic adult

agricultural education and am working to develop evaluation

measures for undergraduate courses and seeking to improve

educational outcomes for women and other vulnerable groups

who have less access to formal education.

Natalia Deeb

Sossa Chicana/o Studies

Examining how Mexican immigrant farm worker mothers, as

cultural citizens, are negotiating power and resisting practices

and policies of educational and health inequity in their local

context. One of her recent articles "

How Race and Ethnicity

Shape Health Care Coverage, Costs and Access" can be found on

the blog for Gender & Society, an outlet of the official journal of

Sociologists for Women in Society.

David de la Pena Human Ecology

Participatory urbanism, design activism, sustainable cities, processes

of community design, landscape education and occupational location

of Hispanics.

Jesse Drew

Techno Cultural

Studies

Theory and practice of alternative and community media,

particularly electronic media, including practices such as blogging,

Low Power FM Radio, social computer networking, cable/satellite

television, peer-to-peer computing, and on-line activism.

Glenda Drew Design

Intersections of visual culture and social change, working class

studies, web and graphic design

Gail Feenstra (SAREP)

Conducting applied and evaluative research that strengthens

community development efforts and coordinating education and

outreach to community-based groups to build their capacity and

leadership skills.

Yvette Flores Chicana/o Studies

Intimate partner violence among Mexicans on both sides of the

border.

Ryan E. Galt Human Ecology

People-environment geography, cultural and political ecology,

agricultural and environmental governance, political economy of

sustainable agriculture, cartographic design.

Liza Grandia

Native American

Studies

Indigenous community development; corporate trade and

globalization; foreign aid and empire; political ecology, biodiversity

conservation, and environmental justice; land grabbing, agrarian

9

Name

Department

Areas of Interest

change and rural development. Countries of interest: Guatemala and

Belize.

Clare Gupta Human Ecology

Translational and interdisciplinary research; alternative food

networks and community food systems; food politics and agro-food

movements (e.g. local food, food sovereignty); community-based

resource management

Susan Handy

Environmental Science

and Policy

Relationships between transportation and land use, including the

impact of land use on travel behavior and the impact of

transportation investments on land development patterns. In

addition, her work is directed towards strategies for enhancing

accessibility and reducing automobile dependence, including land

use policies and telecommunications services.

Bruce Haynes

Sociology

Race and ethnicity, urban, community and sociology of knowledge

Robin Hill Art, Art History

Public art, she believes art is about tuning in to the frequency of daily

life and seeing things as they truly are. “Ideas are encountered,

rather than gotten.

Carlos Jackson Chicana/o Studies

A visual artist and writer, and Director of Taller Arte del Nuevo

Amanecer, a community art center in Woodland, Ca. He is currently

working on a book surveying the history of the Chicana/o Art

Movement.

Susan Kaiser Textiles and Clothing

Fashion theory and feminist epistemologies, Youth style and cultural

anxiety, Cultural studies approach to appearance style and identity,

focusing on intersections among gender, race and ethnicity.

Martin Kenney Human Ecology

Globalization, venture capital, development of innovative clusters,

evolution of high-technology industries, the relocation of services to

developing nations.

Haven Kiers

Human Ecology

Sustainable design, green infrastructure, drought tolerant

planting strategies, and green roofs.

Erika Kohl-Arenas American Studies

Critical studies of philanthropy and the nonprofit sector,

participatory community development, grassroots social

movements and cultural organizing

10

Name

Department

Areas of Interest

Vikram Koundinya Human Ecology

Program evaluation design and capacity-building, qualitative and

quantitative methods, agricultural extension, needs assessments

David Kyle

Sociology

International migration, development and globalization.

William B. Lacy Human Ecology

Sociology of science, organization and structure of agricultural

research and extension (U.S. and international), social psychology of

education and outreach, international research and higher education

policy and practices.

Jonathan London

Center for the Study

of Regional Change

Environmental justice, Environmental/ natural resource policy,

Community and youth participation, Political ecology, Rural

development, Social movements.

Mark Lubell

Environmental Science

and Policy

Watershed management, environmental activism, and agricultural

best management practices.

Beth Rose

Middleton

Native American

Studies

North America and Caribbean. Native American

community/economic development; political ecology; Federal Indian

law; Native American natural resource policy; qualitative GIS;

indigenous geography and cartography; Afro-indigeneity;

intergenerational trauma and healing; participatory research

methods; rural environmental justice; multi-cultural dimensions of

conservation, land use, and planning.

Brett Milligan Human Ecology

Landscape architecture, design activism, environmental design and

planning; climate change adaptation; ethnography and ecology of

infrastructure, sustainable food systems.

N. Claire Napawan Human Ecology

Design of the built environment and investigating the roles in which

landscapes might adapt to provide ever-increasing productive and

infrastructural programs to the global city, given economic, social,

and environmental changes within urban development, including

population growth and climate change

Bettina Ng’weno

African American and

African Studies

Urban and rural communities with a particular focus on space,

citizenship and justice in Latin America and more recently in the

Indian Ocean region.

Patsy Eubanks

Owens Human Ecology Environments of children and adolescents, community participation.

Carolyn Penny

11

Name

Department

Areas of Interest

Common Ground, UC

Davis Extension

Conflict resolution, issue-framing, meeting design, facilitation of

multi-stakeholder decision making, organizational planning,

mediation, facilitation of public engagement processes, training, and

analysis and writing.

Lisa Pruitt School of Law

Law and Rural Livelihoods, Critical Race Theory, Feminist

Jurisprudence, Legal Profession, Critical Whiteness Studies, Torts

Michael Rios Human Ecology

Human geography, urbanism, marginality, social practice of planning

and design, placemaking, political participation, and social

movements.

Julie Sze American Studies

Her research is at the intersection of interdisciplinary fields:

American studies, environmental, urban and ethnic studies. She

focuses on race, class, gender and environment, environmental

justice movement, urban environmentalism and environmental

health.

Keith Taylor Human Ecology

Community economic development, cooperatives, natural resources,

collaboration, rural communities

Tom Tomich Human Ecology

Agricultural sustainability, sustainable food systems, sustainability

metrics and indicators, sustainability science.

M. Anne Visser Human Ecology

The informal economy; non-standard work arrangements; low wage

labor; governance; social and economic integration, equity, and

equality.

Steve Wheeler Human Ecology

Sustainable development; urban design; city and regional planning;

land use; climate change.

Diane Wolf Sociology

Gender and development, family/households, fieldwork, Southeast

Asia, immigration.

Susy Zepeda Chicana/o Studies

Chicana/Latina decolonial feminisms, social justice, critical race and

ethnic studies, U.S. women of color feminist theory, LGBTQI and

queer of color studies, oral history, collaborative methodologies, and

intergenerational healing.

NS OF STUDY & OTHER REQUIREMENTS

Plan I. Thesis and Thesis Project Option + Thesis Defense

12

The Thesis Option requires completion of the following:

• A minimum of 51 upper-division units (>100 series) and graduate units (200 series), including

core courses.

• A 200-hour internship and a written report (7 units) on the internship analyzing the

application of community development concepts to the internship work.

• A thesis, which is a study or research project undertaken in conformance with standards and

practices of scholarly investigation for the topic being studied under the guidance of

student’s Thesis Committee (consisting of three faculty).

• Students should be prepared to give a public presentation of their thesis, either during the

Doing/Debating Development Series, or at some other pre-arranged time.

• The committee will meet with the student for an oral defense of the thesis.

• An oral defense answering questions concerning the research & analysis.

Minimum course distribution is as follows:

Units

Core courses: 24

Concentration & electives: 20

Internship: 7

Total: 51

Remember: The student needs to be the one to keep the process going. You need to stay in touch with

each committee member—keep informed. The faculty and staff won’t do this for you!

CD students who elect this option should take into consideration the following suggestions:

• Begin to organize early. Preferably have research ideas conceptualized if not formalized by

the end of your first year. This is important if you want to conduct research in the summer

between first and second years.

• Consider aligning your internship with your thesis topic. This will give you more time to do

background research and build relationships in your field sites.

• Get your Graduate Studies Thesis Guidelines information from Graduate Studies or from

their webpage. http://gradstudies.ucdavis.edu/forms

• Prepare and submit your Human Subject Protocol with the UC Davis Institutional Review

Board (IRB) if you will be doing research with human subjects. Information on the IRB is

found here: https://research.ucdavis.edu/policiescompliance/irb-admin/

.

13

• Select a thesis chair (this is typically, but not necessarily your existing Major Professor) and a

thesis committee (total three faculty.) The chair must be a member of the Community

Development Graduate Group. The Chair and the student should take the initiative to

determine an appropriate protocol and to set initial deadlines. The thesis committee’s role is

to guide the thesis process. The faculty will help the student plan and monitor research

design and data collection methods, suggest literature to review, edit the student’s thesis

drafts, ask questions during the thesis defense and decide on whether the student passes

the defense and has successfully completed their thesis.

• When forming the committee select individuals who know you and your work and have

knowledge of the field you have studied. Also select people who can help you get jobs or

get into a Ph.D. program if that is your goal.

• The University normally requires three Academic Senate members (faculty) on a thesis

committee. Consult the Graduate Advisor for assistance with this process. Regulations on

committees are at

http://www.gradstudies.ucdavis.edu/gradcouncil/advanced_degree_committees.pdf. Students

working closely with a mentor in their case study organization/ field site sometimes opt to

have this person serve on their committee. One person on the committee (ideally with a

Ph.D. but at minimum a master’s degree and equivalent professional experience.) can be

selected from outside the University, though this requires a petition to Graduate Studies.

• Keep track of the deadlines for the quarter you’re graduating as you need to file for

candidacy before completing the thesis and thesis defense. Anticipate potential delays such

as faculty review time, re-writes and revisions and problems with faculty members being

gone on sabbatical or over the summer.

• All Graduate Studies approval forms (and your transcripts) need to be evaluated by Carrie and

signed by a faculty advisor before you go to Grad Studies with the paperwork.

The thesis defense is generally up to two hours in length. There should not be any surprises if

everyone has reviewed drafts of the student’s thesis in advance. Members of the committee

generally ask the student to make a presentation of ~20 minutes on their thesis, and then ask

questions. Committees frequently request minor changes before the student files the thesis with

Graduate Studies. The oral exam is a great conclusion to the thesis project and a well-deserved

celebration. Ask your faculty committee what you should expect in an oral exam. Some students

take in beverages and food to celebrate (but this is not an expectation of the faculty).

Please make sure to submit an electronic copy of your finally approved thesis to Carrie upon

completion. This will be posted on the CDGG website and with the UC Davis Library to share your

excellent work with the world!

14

Plan II. Written Comprehensive Exam + Orals Option

Examination option call for satisfaction of the following requirements:

• A written comprehensive exam and orals consists of a written and oral examination under

the guidance of the student’s Thesis Committee (consisting of three faculty members).

• Prior to the written examination, the committee members and the candidate agree on a

minimum list of literature and areas of knowledge likely to be covered in the written and

oral exam.

• The committee will meet with the student for an oral defense of the written exam within a

reasonable time after submission of the written exam.

Requirements before the exam:

• A minimum of 55 upper division or graduate units.

• A 200-hour internship and a written report (7 units) on the internship analyzing the

application of community development concepts to the work, written with the supervision

of a faculty member of the Community Development Graduate Group.

• A comprehensive written examination.

Minimum course distribution:

Units

Core Courses: 24

Concentration & electives: 24

Internship: 7

Total: 55

CD students who elect this option should take into consideration the above suggestions as well as the

following, which apply, specifically to the exam option.

The oral exam is intended to test your mastery of three interrelated areas of community

development.

• Begin to organize early. The formal part of the exam option can be completed in one

quarter. However, you should start studying early.

• Form a three-member faculty committee. This committee will give literature suggestions,

prepare written questions, score your exam, and sit on your orals committee. The student

and the committee Chair should set the deadlines that apply to the exam option:

1) The written exam. Each member of the committee formulates questions for the written

15

exam. Students should initiate preparations for the reading list used in their exam. The

areas to be covered and any particular emphasis that you want to develop. You have 72

hours for the exam and it is an open book exam that you can do in your study or home.

You are expected to work alone on it.

2) Normally, students get the questions by email on Friday morning and return their

responses on Monday morning. Students are normally expected to write 10-15

typewritten pages (not including references) in response to each question.

The oral exam is a rigorous defense of the written examination questions. It can also extend beyond

the specific questions to test the student’s ability to integrate other literature on the reading list to

demonstrate analytical capacity in the student’s three chosen areas. Oral examinations normally last

2 hours.

Internship Requirement

This is the “practicum” portion of our program. You should visit Carrie Armstrong-Ruport and talk to

your faculty advisor for ideas and advice about finding an appropriate internship. You may pursue an

internship independently if neither suggests anything that strikes your fancy. Not all internships are

paid, unfortunately. The time commitment amounts to a half-time job for one quarter (or quarter

time for two quarters). You need to arrange for a faculty sponsor before you start your internship

and complete the departmental contract. At the completion of the 200-hour internship, CD students

should complete a report on this internship that becomes part of their file. The format of the report

should be negotiated with the student’s internship Advisor.

You will have to complete 200 hours of internship and receive 7 (seven) units for this requirement.

According to UCD policies, 30 hours of internship work are required for one unit. Thus, the

remaining 10 hours to complete this requirement will be satisfied when you submit a written

account and analysis of your internship experience and the skills learned under the supervision of

your faculty mentor.

See Appendix II & III for more information about Internship requirements.

16

Filing Fee Status

If you want to save considerable money after you’ve finished your coursework, you can go on filing

fee status and pay much less than you would as a full-time student. The Filing Fee was established

expressly to assist those students who have been advanced to candidacy and who have completed

all requirements for degrees, including all research associated with the thesis or dissertation, except

filing theses or dissertations and/or taking final (comprehensive) examinations. However, be aware

that it is a one-way process, and once you are on Filing Fee status you may not:

1. Use any University facilities (e.g. Health Center, Housing, Library, Rec Hall, laboratories, desk

space). However, you may purchase a library card and/or health insurance, if you wish;

2. Make demands upon faculty time other than the time involved in the final reading of the

thesis/dissertation or in holding final examinations;

3. Receive a fellowship, financial aid or academic employment beyond a single quarter;

4. Take course work of any kind;

5. Conduct your thesis research

The University is now also limiting students to one quarter of filing fee status.

You should be aware that many loan agencies do not recognize this status and may require early

repayment of student loans.

Graduation

The program generally takes 2 years (~20 months) to complete. Students can complete the degree in

this time if they select the exam option or begin their thesis research early in their second

year. However, some students finish their writing during the summer following their second year or

take an extra quarter. It is important that students proactively identify any obstacles to completing

the degree on time and discuss them with Carrie and/or their faculty advisor.

After the thesis or exam is completed you will have a final exit interview with Graduate Studies and if

everything is completed to their satisfaction you will be placed on the next final degree list. After

graduation, your UCD email address will remain open for a few months.

If you want to continue to get UC Davis information you can request an alumni email account from

the Alumni Center.

We strongly encourage you to become an active alumnus of the CDGG program to stay connected to

your classmates, contribute your expertise, networks, and financial support to benefit the current

students in the program. Please inform Carrie of your new contact information so you can be added

to the alumni website. Core Community Development Courses (required)

17

CRD 240. Community Development Theory (4)

Lecture/discussion—4 hours. Introduction to theories of community development and different

concepts of community, poverty, and development. Emphasis on building theory, linking applied

development techniques to theory, evaluating development policy, and examining case studies of

community development

organizations and projects.—I.

CRD 250/CRD 200. Professional Skills for Community Development (4)

Seminar—4 hours. Prerequisite: course 240. The intersection of theory and case studies to develop

practical skills needed to work as a professional community developer, program administrator,

and/or policy consultant.—III.

CRD 290. Seminar (1) — Doing and Debating Development

Seminar—1 hour. Analysis of research in applied behavioral sciences. (S/U grading only.)—I. II. III.

• In the Fall, the DDD is typically focused on faculty presentations of their research

• The Winter DDD provides workshops practical skill development

• The Spring DDD is devoted to thesis presentations of the graduating students.

Methodology (Required) - To be taken in the winter of the first year.

LDA 202. Seminar (4)

Methods in Design and Landscape Research

Seminar – 4 hours. Explores many of the research and advanced design and planning methods

employed in landscape architecture. Exercises provide the student with a vehicle for designing

independent landscape research and creative activities. Lectures provide a historical overview of

research methodology. – II.

Not required but strongly recommended for winter of the second year:

CRD 260. Thesis Seminar (2)

Workshop to help finalize thesis proposals and complete thesis. May be repeated for credit.

18

Core Community Development Courses (electives)

Current scheduling as of August 2020 is marked below, but check with the relevant program or

department to get up-to-date listings, as these frequently change.

CRD 241. The Economics of Community Development (4)

Seminar—4 hours. Prerequisite: graduate standing. Economic theories and methods of planning for

communities. Human resources, community services and infrastructure, industrialization and

technological change, and regional growth. The community’s role in the greater economy. To be

offered Fall 2020. Kenney.

CRD 242. Community Development Organizations (4)

Seminar—4 hours. Prerequisite: course 240. Theory and praxis of organizations with social change

agendas at the community level. Emphasis on non-profit organizations and philanthropic

foundations.

CRD 243 Critical Environmental Justice Studies (4)

Seminar- 4 hours. Introduction to the history, theory, policy, and social movement aspects of

environmental justice issues in the United States and around the world. Focuses on the political,

economic, social, and cultural factors that shape disproportionate exposures to environmental

hazards in low-income communities and communities of color as well as the social movements that

mobilize to contest these injustices. To be offered Fall 2020 London.

CRD 244. Political Ecology of Community Development (4)

Lecture – 4 hours. Community development from the perspective of geographical political ecology.

Social and environmental outcomes of the dynamic relationship between communities and land-

based resources, and between social groups. Cases of community conservation and development in

developing and industrialized countries.

CRD 245. The Political Economy of Urban and Regional Development (4)

Lecture—4 hours. Prerequisite: course 157, 244, or the equivalent. How global, political and

economic restructuring and national and state policies are mediated by community politics; social

production of urban form; role of the state in uneven development; dynamics of urban growth and

decline; regional development in California. To be offered Spring 2021 Chu.

CRD 246. The Political Economy of Transnational Migration (4)

Lecture—4 hours. Prerequisite: graduate standing. Theoretical perspectives and empirical research

on social, cultural, political, and economic processes of transnational migration to the U.S. Discussion

of conventional theories will precede contemporary comparative perspectives on class, race,

ethnicity, citizenship, and the ethnic economy..

19

CRD 247. Transformation of Work (4)

Lecture/discussion—4 hours. Prerequisite: graduate standing in history or social science degree

program or consent of instructor. Exploration of the ways that the experience, organization, and

systems of work are being reconfigured in the late twentieth century. The impacts of economic

restructuring on local communities and workers. To be offered Spring 2021 Visser

CRD 249. Media Innovation and Community Development (4)

Seminar – 4 hours. Role of innovative media in communities and social change. Studies historical,

practical and theoretical issues involving media in community organizing, social justice movements,

democracy initiatives, and economic justice. –

CRD 251. Critical Social Science of the Environment (4)

Seminar – 4 hours. Relationships between forces of society and the environment through careful

examinations of the interactions between politics, economics, and global dynamics. Schools of

thought concerning society , gender, environmental dynamics, and political economic arrangements

across local and global spheres. (pending approval).

CRD 298. Group Study (1-5)

GEO 220. Topics in Human Geography (4)

Seminar – 4 hours. Examination of philosophy and theory in human geography with an emphasis on

contemporary debates and concepts in social, cultural, humanistic, political, and economic

geographies. Specific discussion of space, place, scale and landscape; material and imagined

geographies. – II. Pending approval by academic senate

LDA 201. Theory and Philosophy of the Designed Environment (4)

Major theories and ideas of environmental design and planning. The epistemology of design will

serve as a framework to review critical theory in contemporary landscape architecture, architecture,

planning, and urban design. Normative theories of design and planning will be reviewed along with

relevant theories from the social and environmental sciences.

LDA 205 (GEO 233). Urban Planning and Design (4)

The aim is to give students an understanding of how built landscapes evolve, and how they can be

creatively planned and designed in the future so as to meet social and ecological goals. This class is

appropriate for students in community development, geography, landscape architecture, and

environmental planning programs, as well as others interested in land use, sustainable development,

or place-making strategies beyond the building scale. Every Fall. Wheeler.

20

LDA 215. Ecologies of Infrastructure (4)

Focus on design practices and theory associated with ecological conceptions of infrastructure,

including networked infrastructure, region/bioregion/regionalization, ecological engineering,

reconciliation ecology, novel ecosystems, and theory/articulation of landscape change.

LDA 216. Food & the City (4)

Exploration of theory and practice related to the design and planning of alternative and resilient food

systems, including urban agriculture, agrihoods, and agri-/rural tourism. Includes investigation of

urban-rural connections and case studies of regional urban agricultural projects.

LDA 270. Environment & Behavior (4)

Factors that influence humans’ interaction with their surroundings and the mechanisms used for

recognizing and addressing general and specific human needs in community design and development

decisions.

LDA 280. Landscape Conservation(4)

Focus is on land planning, design, and management techniques to further the goal of resource

preservation. Examines current critical theory in the establishment and management of conservation

areas. Offered in Winter 2021 Greco.

21

Internship/TA/Research Courses

292. Graduate Internship (1-12)

Internship—200 hours (7 credits). Individually designed supervised internship, off campus, in

community or institutional setting. Developed with advice of faculty mentor. (S/U grading only.)

299. Research (1-12) (S/U grading only.)

Used when conducting thesis research or other independent study (advised by a faculty member).

396. Teaching Assistant Training Practicum (1-4)

Taken along with employment as a Teaching Assistant. (S/U grading only.)—I, II, III.

NOTE: CRD 396 units are not currently offered for TAs Students employed as TAs should sign up

for research units with their advisor/ major professor.

22

Thesis Proposal Guidelines

A thesis is a research project of your choice undertaken in conformance with standards and practices

of scholarly investigation for the topic being studied. It is developed under the guidance of the

student’s Thesis Committee, usually consisting of three faculty (see Outside Members section

below). Students give a public defense of their thesis, during which they present their work to other

students and members of the broader community, and answer questions from the audience and

their thesis committee. Instead of the traditional research thesis it is also possible for CDGG students

to prepare a professional project, in which students work closely with a client organization to

produce an applied piece of professional work mutually agreed upon in advance. Theses become a

part of UCD’s library holdings and are made available to the public through the CDGG website.

The Proposal

To help clarify your project for both yourself and your committee at the outset, students should

prepare a research proposal. Exact format is up to your committee chair, but in general it is good to

start with a concise two-page outline of your proposed research (brevity encourages focus). Don’t go

on at length describing the context or why this work is important. Include the following:

• Title of your project

• Brief background. A one paragraph explanation of why you want to do this/its importance

and relevance

• Identification of relevant literature and theory from academic and professional sources.

• Research questions and learning goals for the thesis

• Expected findings/hypotheses

• Methods. One paragraph explaining your method and data sources (e.g. interviews, case

studies, focus groups, surveys, ethnography, participant observation, quantitative analysis,

post-occupancy evaluation, site analysis and design, GIS analysis, direct observation and

behavior mapping, etc.)

• Outline of final product (number of pages; a short list of 4-7 chapters with target lengths for

each). Aim for 30-50 double-spaced pages total. Make a separate list of any essential

graphics and maps.

• Committee, (chair plus two other members).

• Timeline. Work backwards from when you want to finish. Include the following:

o Finalize proposal, confirm committee, obtain IRB approval if necessary

o Review literature

o Field research

o First draft to committee (allow them at least 2-3 weeks to read and turn around

comments)

o Comments back from committee (give yourself at least 2 weeks to produce a final

draft)

23

o Final draft to committee (at least 2 weeks before defense)

o Defense date (at least 2 weeks before final submission)

o Final submission to UCD (check with Grad Studies or CD advisor for deadlines &

procedure)

Drafts of professional documents are usually double-spaced. Use 12-point type and 1-inch margins.

Grad Studies has requirements for the final document and other useful information at:

http://gradstudies.ucdavis.edu/students/degree_candidates.html.

Institutional Review Board

If you will be working with human subjects (doing interviews, focus groups, etc.) you will need to get

an exemption or approval from the Institutional Review Board. Your thesis chair can provide

guidance. The IRB will require a copy of your survey or interview questions. Many social science

research projects involving interviews or surveys are exempt under the IRB’s Category 2 Exemption

as long as data from respondents are treated anonymously (no names recorded) or confidentially (no

names provided or use of pseudonyms). Further information and the Exemption Form are available

here: http://www.research.ucdavis.edu. Allow plenty of time to receive IRB exemption or

approval before you start your work. The IRB also regularly provides seminars which are announced

on GradLink.

24

The Thesis Project Option

The thesis project option involves students in working with one or more client organization to

produce some kind of practical product (such as a policy report, curriculum, feasibility or evaluation

study) and then documenting and reflecting upon the product and the process of developing it

through the lens of community development and related theories. The structure is similar to the

standard thesis (including an introduction, methods, literature review analysis, and conclusions) but

the “data” for the thesis is the project product. Projects may be expected to utilize a broader variety

of formats and media than theses. A good rule of thumb is that the thesis project consists of 20%

Introduction/ Theory/ Methods, 60% Professional Project Product and 20% Analysis, Conclusions,

and Recommendations.

For students planning to embark on professional work upon graduation, the project option can

provide an opportunity to work with interesting community organizations and make useful contacts

with professionals.

A letter of agreement between the student and client is required at the beginning of the project,

detailing expected products and the expected working relationship. A second letter is requested

from the client at the conclusion of the project, confirming successful delivery of the agreed-upon

materials.

The Defense

The thesis defense is a session of up to two hours long. At the defense, plan to make a 30-minute

presentation of your work. Committee members will then ask questions. Your Chair will serve as the

moderator. After the question period, your committee members will adjourn to discuss your work in

private, and will then ask you to join them so that they can give you feedback and discuss any

needed revisions. The defense is a great conclusion to your thesis or project and a well-deserved

celebration.

Submitting an Electronic Copy of Your Thesis

In addition to the materials you file with Graduate Studies, provide a complete copy of your final

thesis as a single PDF file to the Community Development Graduate Group master advisor. Your

thesis will be made available to others electronically on the CDGG website.

25

Key Milestones to Completing the M.S. in 2 Years

Key Milestones,

Required Forms and

Target Date

Milestone

Form required to be filed with Carrie

Armstrong-Ruport

Last week of

September incoming

students first year

Meet with Initial Advisor before the

beginning of classes

Degree Requirements Planner form

--signed by Initial Advisor

December 1

st

, each

year

Submit plan for courses to be taken for

the current year

Updated Degree Requirements

Planner form

--signed by Initial Advisor

May 1

st

, first year

Select Permanent Advisor and/or Change

of Graduate Advisor

Selection of Permanent Advisor form

and/or Change of Graduate Advisor

--signed by Permanent Advisor

Spring first year

Select a thesis committee

Develop thesis proposal

Appointment of Master’s Thesis

Committee form

--signed by committee chair

June 1

st

each year

PROGRESS REPORT*

Meet with Permanent Advisor and

signed by Graduate Advisor

End of Spring first year

Present thesis proposal to thesis

committee

Advisor’s Report on Master’s Thesis

Proposal Defense form

--signed by Permanent Advisor

Summer between 1

st

and 2

nd

year

Internship (can also be conducted during

the school year)

Begin thesis research

Report on Internship

--completed by student and

submitted to Carrie Armstrong-

Ruport

May 1

st

, second year

Advanced to Candidacy* (completed all

degree requirements except

Thesis/Exam)

Advanced to Candidacy form signed

by Graduate Advisor

--submitted to grad studies and

Carrie Armstrong-Ruport

26

Spring of 2

nd

year

Defense and completion of thesis

Copy of thesis, including Thesis

Committee Approval page

--signed by thesis committee

Upon Graduation

Submit electronic copy of thesis

Join the CDGG Alumni Association

Copy of thesis submitted to Carrie

Armstrong-Ruport

*Office of Graduate Studies Forms

27

III. RESOURCES

Sources of financial assistance include: loans, grants, fellowships, work-

study, Teaching Assistantships (TAs) and Graduate Student Researchers

(GSRs).

Loans, Grants, and Fellowships

Loans, grants and fellowships are available through the Campus Financial Aid Office, and information

regarding them is available through Graduate Studies, the Graduate Student Association (GSA) and

the Financial Aid Office. Also consult Carrie and your initial or permanent faculty advisor about

financial assistance opportunities. There are listings of UC Davis sources of financial support for

graduate students at: http://gradstudies.ucdavis.edu/ssupport/index.html

There is also a useful

listing of external fellowship opportunities at:

http://gradstudies.ucdavis.edu/programs/external_fellowships.cfm

The Erna and Orville Thompson Graduate Student Fund

The Erna and Orville Thompson Graduate Student Fund is funded by an endowment that is to be

used to support graduate studies in community development, in particular to support research

projects and/or travel to present either a poser or paper at professional meetings. Grants are

awarded based on a competitive review of proposals. A call for proposals, with detailed guidelines,

will be issued early in the winter quarter, with a deadline towards the end of the winter quarter.

This is a good way to fund summer research trips between the first and second year of study.

Specific grant sizes vary from year to year (depending in part on available of funds), but in recent

years the maximum amount for research expenditures has been $2,000, and $500 for travel to

professional meetings.

Graduate Research Assistant – Work-study

Work-Study is basically a grant that partially funds your employment on campus. Graduate Financial

Aid, in collaboration with Graduate Studies and individual academic departments, awards Work-

Study to graduate students based on student eligibility, as determined by the student’s FAFSA need

analysis, and the completion of any open financial or federal aid requirements.

To be considered for Work-Study funding, graduate students are required to:

• File the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), available online at fafsa.ed.gov.

• Work with their academic program to request a Graduate Student Researcher (GSR) Work-

Study position. Academic Program staff hire the GSRs and notify students when Work-Study

awards are posted online.

If you receive a work-study award, you still must find a paid Graduate Student Researcher position

that will enable you to take advantage of it. In a few words, work-study is subsidized employment,

28

which eligible faculty employers like very much. Carrie will put out a call to update your FAFSA and

look for work-study opportunities during Spring Quarter. Research positions don’t necessarily

require a job announcement, and they definitely tend to go to students the faculty member has

already seen in action. So—the best way to get hired is to develop relationships with instructors and

researchers and be persistent. Be up front about desired employment, interest in teaching or the

person’s on-going research. Ask about potential new projects.

TAs and Readers

The department has a limited number of TA and Reader positions. Normally those TAs and Readers

are selected before 1

st

year students arrive. However, many other departments on campus routinely

need TAs and post such jobs throughout the year. Carrie will send out emails about jobs as these

positions become available. Look up the courses you have experience in and would like to TA, then

approach the instructors. It may be a long shot your first time, but these contacts may well bear fruit

the next time the course comes around. It’s a lot like pursuing any job—schmoozing helps. And

when you get a job, be dependable.

If you intend to TA, there’s a mandatory TA training workshop you will need to attend. It is held only

once a year in September and is offered by the campus Center for Excellence in Teaching and

Learning. If you simply want information about TAing or help along the way, the Center is very

helpful (1321 Haring Hall). Student academic jobs vary in intensity of work. Readers simply read and

grade exams. Teaching Assistants take an active role in the teaching process by leading discussions

and giving guest lectures. Not all classes have discussion sections. The department also recognizes a

TAship with special units that count for our overall progress and that will appear on your transcripts.

Traditionally, the responsibilities of reading and grading and copying fall under the job title of

“Reader.” Jobs as TAs Readers and Grad Student Researchers pay relatively well. Carrie can provide

you with the current pay scale. TAs/Readers receive a partial fee remission. To obtain your

remission, however, you must be appointed within one week of the start of the quarter at a

minimum of 25% (10 hours) for the entire quarter. The remission is processed after employment

paperwork has been completed. The deadline for advanced payment of fees is one month prior to

the start of the quarter, but Student Aid Accounting will issue refund checks if your qualifying

appointment is processed after the late fee deadline. Students are responsible for any late

registration fees.

The Center for Educational Effectiveness (CEE)

Offers a wide array of resources, classes and overviews on a wide variety of teaching related topics.

Their activities are listed under http://cetl.ucdavis.edu

and you will additionally get information

about them through the newsletter ‘GRADLINK” of the Graduate Studies. Please note, if you plan to

work as a Teaching Assistant or Reader, you must take the Teaching Resource Center’s Sexual

Harassment Classes held in September.

29

The UC Davis Center for Regional Change

Directed by Jonathan London and Bernadette Austin, this Center conducts interdisciplinary and

solutions-oriented research to support the building of healthy, prosperous, sustainable, and

equitable regions in California and beyond. Information can be found at:

regionalchange.ucdavis.edu) and in the CRC’s Community and Regional Development Mapping

Laboratory in 152 Hunt Hall. The CRC often has paid employment as well as internship and volunteer

opportunities for graduate students on its projects. These projects focus on four major themes: civic

engagement, environmental justice, rural and regional development, and youth well-being and

empowerment.

30

Getting By, Getting Around

One of your first big tasks in settling into the CD graduate program will be to “research” the faculty

relevant to your course of study. Carrie will provide summaries of the respective research interests

and courses taught by the different faculty of our graduate group, which can get you started. Most

likely you’ll find yourself going outside of the grad group to find other faculty involved in your area of

interest. One simple way to find these folks is to go through the course catalog and look up the

instructors of the courses you find interesting. Your Initial Advisor also can help locate appropriate

courses and faculty.

The process of “researching” the University faculty relevant to your studies is basic and essential to

making your graduate studies complete. It may seem a bit daunting or intimidating at first, but you’ll

find most faculty are more than eager to talk to new students interested in their research. Their

research can give you insights that go beyond current literature. Faculty can also turn you on to new

literature, or even take you on board as a researcher or TA. This process is also basic to the nature of

a graduate group—a lot of work is self-initiated, not much is laid out for you as a path—though

previous students’ course lists and experiences can be a guide. It is up to the student to carve

his/her own path of coursework and study, which means researching courses and faculty in other

departments.

To help you understand the structure of the university it is useful to be familiar with the titles of the

academic you will encounter and work with.

• Instructor: Hired on a year to year basis to teach undergraduate classes.

• Lecturer: Usually hired on a year to year basis, primarily to teach undergrad classes.

Members of the Academic Federation. Can serve on a thesis committee, but not as Chair.

• Assistant Professor: A person in a tenure track position and member of the Academic

Senate who is trying to publish and teach at a high enough level (up to seven years) to

achieve tenure as an Associate Professor

• Associate Professor: Tenure is awarded based on the quality and quantity of publications

(research), teaching effectiveness, and University and community service. The rank

subsequent to Associate Professor is Full Professor

• Full Professor: Promotions follow the same criteria, teaching research and service.

• Note: The title of “professor” (Assistant, Associate or Full) is only given to members of the

Academic Senate.

In addition, Cooperative Extension Specialists are hired by UC Agriculture and Natural Resources

(part of all land-grant colleges) for University outreach and engagement. Many Extension Specialists

are members of graduate groups. Senate faculty and CE Specialists with Lecturer without Salary titles

can serve as Chair of thesis committees.

31

Other Resources

California State Library

When you use the University Library’s computer catalogue system, MELVYL, you may occasionally

come across listings that are only available at “CSL.” That is the acronym for the California State

Library, located just to the southwest of the Capitol building in Sacramento. If you are researching

any state or local histories within California, the CSL is often your best source. Fortunately, it’s less

than 20 minutes away by car and accessibly by Yolo Bus. Its text collection and historical archives are

extensive, but unfortunately not available for loan to people who are not State employees. They do

offer an in-house reproduction service of some documents, however.

The UC system is host of CDL, the California Digital Library, which gives you access to vast resources

of databases free of charge. Anyone can access the full range of the library’s licensed databases from

one of the UCD campus libraries. Remote or off campus access, however, is restricted to UCD

students, faculty, and staff. Use your Kerberos User ID and password (obtain at the Information

Technology/IT help desk in Shields) to logon to my.ucdavis.edu, or go to

http://www.lib.ucdavis.edu/ul/services/connect/

for additional ways to connect.

We highly recommend you participate in one of the seminars that Shields Library organizes to make

full use of its resources is recommended. A current schedule can be found on the library’s home

page at www.lib.ucdavis.edu

(path is Library Services/Instruction.) Also, you can download for free a

very useful and easy to master bibliographical program for the MyUCDavis Website (called

“Endnote”) that you should get familiar with as soon as possible and use from the very first day you

start reading and researching.

Electronic mail and Internet. The most important way to communicate is over the E-mail network,

made very accessible to us here on campus. The University has a complete infrastructure of support

for those needing help with or acquaintance to the campus E-mail system and Internet. Nearly

everything you could need is available at: http://iet.ucdavis.edu/

UC Davis expects all students to own a computer with an internet connection, CD-ROM drive, and

printer. Computers must be able to run a word processing program, spreadsheet program, email

program, and Web browser. The campus features a wireless network throughout the majority of the

campus that is free to all UC Davis affiliates. For coverage maps and connection information,

visit wireless.ucdavis.edu

.

There is a computer lab available for your use on the 3

rd

Floor of Hart Hall. Carrie will give you the

combination to the door.

The Community Development Grad Group has its own listserv on which students can send each

other messages and on which Carrie Armstrong-Ruport and Faculty can post information. Note: no

one except current CD students can read your correspondence on this list. To post to this listserv,

send email to: cd-[email protected]

. CD Grad students and CD alumni also have a discussion

33

MASTER OF SCIENCE PROGRAM IN COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

Degree Requirement Planner

(File copy of signed and updated form with Graduate Coordinator)

STUDENT NAME: _______________________________ DATE: _____________

GRADUATE ADVISER:_______________________________ MAJOR PROFESSOR ____________________

Community Development Core Courses (24 Units) Quarter/Year

Planned Completed

CRD 240 Community Development Theory (4) _________ _______

Fall Qtr of Yr 1

CRD 250/CRD 200 Professional Skills for Community Development (4) _________ ________

Spring Qtr of Yr 1

CRD 290 Community Development Seminar (4) (p/np) (4 quarters of enrollment required)

Fall, Winter, Spring Qtr of Yr 1; Spring Qtr of Yr 2 _________ ________

CRD 260 Thesis Seminar (optional; 2 units) _________ ________

Winter, Yr 2

Choose 1 course from the following to complete the research design requirement:

AAS 204 Methodologies in African American and African Studies (4) _________ ________

LDA 202 Methods in Design & Landscape Research (4) _________ ________

Choose 2 courses from the following to complete the core course requirement:

CRD 241 Economics of Community Development (4) _________ ________

34

CRD 242 Community Change Organizations (4) _________ ________

CRD 243 Environmental Justice and Community Development ________ ________

CRD 244 Political Ecology of Community Development (4) ________ ________

CRD 245 Political Economy of Urban & Regional Development (4) ________ ________

CRD 246 Transnational Migration (4) ________ ________

CRD 247 Transformation of Work (4) ________ ________

CRD 248 Social Policy, Welfare Theories and Communities (4)

Not offered 2018-19 ________ ________

CRD 249 Media Innovation and Community Development (4) ________ ________

GEOG 220* Topics in Human Geography (4) ________ ________

LDA 201 Theory and Philosophy of the Designed Environment (4) ________ ________

LDA 204 Case Studies in Landscape Design and Research (4) ________ ________

LDA 205 (GEO 233) Urban Planning and Urban Design (4) ________ ________

LDA 215 Ecologies of Infrastructure (4) ________ ________

Electives (20 elective units plus thesis, or 24 elective units plus exam) Quarter/Year

Courses must be LETTER GRADED and at least HALF of electives must be 200 LEVEL OR HIGHER

One course must be a methods course appropriate to areas of specialization

Number Title

(methods) 1. ______ _______________________________________ ________ ________

2. ______ _______________________________________ ________ ________

35

3. ______ _______________________________________ ________ ________

4. ______ _______________________________________ ________ ________

5. ______ _______________________________________ ________ ________

(exam option) 6. ______ _______________________________________ ________ ________

Internship (Required—200 Hrs or 7 units)

IMPORTANT NOTE: Internship units DO NOT count toward core unit requirements. Meet with Carrie Armstrong-

Ruport, Program Coordinator before pursuing any internship.

Copy of completed Report on Internship must be filed with Carrie Armstrong-Ruport.

Faculty internship sponsor: ________________________________________________

Agency: ________________________________________________________

Dates of Internship: ______________________________________________

Required Signatures:

Faculty Advisor: ____________________________ Date: ___________