The Default Project:

A Survey of the Reasons for Tenant Defaults

in Housing Court Eviction Cases

Findings and Policy Recommendations

Prepared by the Massachusetts Law Reform Institute and the Justice Center for Southeast

Massachusetts upon request of the Massachusetts Access to Justice Commission Housing Working

Group, based on research conducted by AmeriCorps Legal Advocates of Massachusetts

December 2022

2

Executive Summary

In 2018 the Executive Office of the Trial Court provided a report summarizing the number of Housing

Court Summary Process (eviction) cases where a Default Judgment entered against the tenant. An

analysis of the Trial Court’s report revealed that from 2015 to 2017 the court entered a default

judgment in nearly 25% of Housing Court eviction cases statewide – a troublingly high rate since losing

an eviction case puts a household at imminent risk of homelessness. In response to this finding, the

Access to Justice Commission collaborated with the AmeriCorps Legal Advocates of Massachusetts (ALA-

MA) to improve understandings of the reasons for tenant defaults.

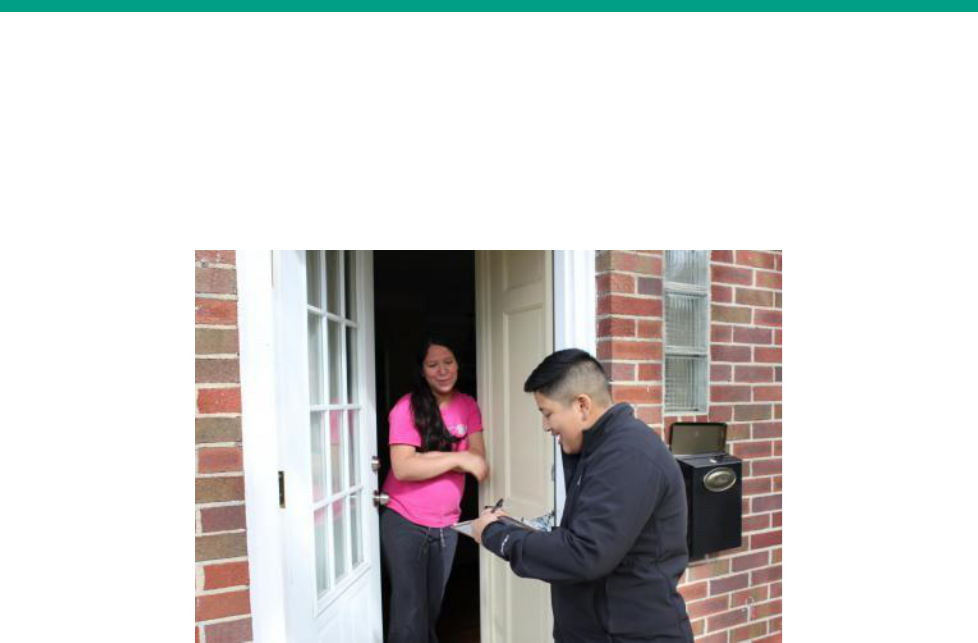

Throughout March 2019, AmeriCorps volunteers attended every Housing Court session across all six

court divisions, ultimately identifying 621 defaults against tenants. The volunteers then tracked these

cases in two ways: (1) they engaged in a door-knocking campaign, completing 123 in-person interviews

to understand the reasons why tenants were defaulted; and (2) they used the Trial Court’s online case

access system, MassCourts, to look up the final outcome of all 621 cases where tenants were defaulted.

This report will outline the findings of the interviews and case outcome analysis, and suggest policy

recommendations to help improve court access for tenants.

Interview Findings:

Most tenants who were interviewed never made it to court. Tenants who did not get to court reported

most frequently that:

• They did not receive the summons and complaint.

• They had paid their arrears and believed they did not need to go to court.

• They had been told by a landlord or property manager that they did not need to go to court.

Tenants who made it to court, or tried to, reported most frequently that:

• They faced challenges with transportation, lack of childcare, medical conditions, and disability.

• They made it to court but were still defaulted because they were late or were unable to locate

the correct courtroom.

Case Outcome Findings:

A review of the outcomes of the 621 cases reveals that over 80% of the tenants who were defaulted

likely lost possession of their home. A forced move-out was the likely result even including cases where

tenants were able to file a motion to remove the default or reached an agreement with their landlords

following the default.

Policy Recommendations:

Courts should place a high priority on the explicit goal of reducing defaults. Like many aspects of

summary process, reducing defaults should be reimagined with active participation from all court users,

and centered upon the needs of those who are accessing the system without representation. In light of

the complexity of the process, the rapid pace of court events, and the overwhelmingly high rate of

3

tenants who do not have legal assistance, courts should emphasize greater simplicity, flexibility, and

accessibility in court processes, court access, and physical courtroom spaces.

• Tenants should not be defaulted on their first court date

• Court forms should provide key information in plain language

• Court correspondences should include multilingual notices indicating that the document should

be translated

• Courts should provide flexibility in proceedings, such as alternative court hours and locations, as

well a “grace period” for tenants to appear on the day of court

• Courts must meaningfully follow existing requirements under the Americans with Disabilities

Act, both in communication and in physical courtroom access.

4

Project History and Methodology

In 2018 the Executive Office of the Trial Court provided a report summarizing the number of Housing

Court Summary Process (eviction) cases where a default judgment entered. An analysis of the Trial

Court’s report revealed that from 2015 to 2017 the court entered a default judgment in nearly 25% of

Housing Court eviction cases statewide.

1

Under the Uniform Summary Process Rules, a tenant’s first court date is ordinarily their trial date.

2

If the

tenant fails to appear in court on that date, or fails to respond when their case is called, the court enters

a “default.” Entry of a default means that a judgment automatically enters against the tenant. When a

default judgment is entered against a tenant they can lose possession of the unit, and even be moved

out, despite never being heard by a judge. Once a default judgment is entered it cannot be appealed,

and within 11 days a tenant can be physically removed from the property.

3

The only way a default

judgment can be removed is by order of the court.

Reducing defaults has long been a key access to justice priority. The 2017 Massachusetts Justice for All

Strategic Action Plan

4

, the result of a collaborative process including representatives of the Access to

Justice Commission, courts, legal aid providers, social services organizations, law schools, bar

associations, litigants, community groups, and other stakeholders, identified defaults as an access to

justice concern and made high level recommendations about minimizing them. However, without a

better understanding of the reasons tenants were not appearing in court, or appearing too late to be

heard, it was difficult to craft effective solutions. The Massachusetts Access to Justice Commission’s

Housing Committee approached ALA-MA about conducting research on the reasons that the default rate

was so high – nearly 25% between 2015 and 2017. With the assistance of the Massachusetts Law

Reform Institute (MLRI) and the Justice Center of Southeast Massachusetts (JCSEM), ALA-MA designed

1

The Executive Office of the Trial Court reviewed available data for FY2015 to FY2017 and compiled a summary

report on the number of disposed summary process cases, by Housing Court division and year of disposition,

where there was a Judgment by Default. The request for data was made by MLRI. See Appendix for the Trial

Court’s summary report and MLRI’s analysis.

2

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Housing Court issued standing orders implementing a two-tier

system for hearing summary process cases. The Tier 1 event is a mediation and status conference with the

Housing Specialist Department, while the Tier 2 event now serves as the trial date. During the COVID-19 State of

Emergency, Standing Order 6-20 provided that a tenant would not be defaulted for failure to appear at the Tier 1

event but would be sent a notice scheduling their case for a Tier 2 hearing (trial), at which point a default could

enter if they again failed to appear. This policy was amended by the Third Amended Housing Court Standing

Order 6-20 and now allows for defaults to enter at the Tier 1 event for any case filed on or after July 1, 2021.

3

Rule 12 of the Uniform Rules of Summary Process (2004).

4

In 2017 the Massachusetts Justice for All Project was awarded a grant to develop a Strategic Action Plan to

improve access to justice in Massachusetts. The Strategic Action Plan adapted recommendations prepared by

the Justice for All Housing Working Group, entitled Access to Justice in Housing: A Housing Stabilization Vision.

Information about the Massachusetts Justice for All Project, including a link the Strategic Action Plan, can be

accessed at http://www.massa2j.org/a2j/?page_id=811.

5

and undertook the research component of this Default Project to better understand the reasons tenants

default in eviction cases.

5

The project involved a statewide research and canvassing effort conducted by AmeriCorps members,

legal services advocates, and other volunteers. The project was guided by the recognition that tenants

are experts in their experience, so in order to better understand the reasons for the high rate of defaults

it was necessary to speak directly to tenants. The primary purpose and focus of the Default Project was

to gather qualitative information, in the form of tenant narratives, and was not intended to present a

strict quantitative analysis. The researchers then supplemented their canvassing and interview findings

with quantitative analysis of case outcomes using publicly available court data.

In March 2020, a year after this research was conducted, the COVID-19 pandemic forced courts to adjust

their procedures in response to emergency public health measures, a process that is still evolving as

conditions change. While some adjustments to court processes have seemed to help address the default

problem, new challenges to court access have arisen. Studying pandemic-era data will be important as

we seek to understand the interventions that are most effective at reducing defaults. As courts continue

to develop their summary process practices, both the information gathered during this project and its

recommendations – including a set of recommendations specific to the Court’s pandemic-era operations

– should serve as a useful resource.

Methodology

Throughout March 2019, approximately 30 advocates and volunteers attended each session of the

Housing Court. This totaled 115 sessions across the six Housing Court divisions. The volunteers identified

621 cases in which a tenant was defaulted in the court session. They then followed up with these

tenants through a door-knocking campaign to ask questions about why they were defaulted by the

court, and to provide information about how to remove a default. They followed up with each tenant

who defaulted and successfully interviewed 123 of the tenants.

Volunteers used an open-ended questionnaire to collect information about tenants’ experiences with

the eviction process. Project coordinators entered the results into a database, standardized the

responses, and analyzed the results. Although some respondents described multiple, overlapping

barriers to accessing the court in their narrative responses, the analysis that follows focuses on the

primary reason for default identified by each tenant.

Although the summary report provided by the Trial Court provided the number of “judgments by

default” for the specified period, it is unclear exactly what the numbers represent. For example, these

numbers do not indicate at what point in a case the default occurred; whether it represents defaults at

the initial trial date or if it also includes defaults later in a case; or whether it includes defaults that were

subsequently removed. The complexities and nuances of this type of data demonstrate the importance

of this Default Report.

5

AmeriCorps members from ALA-Massachusetts participated in the data collection portion of this project. ALA-

Massachusetts and its members do not endorse or support any policy platform or legislation.

6

In the year that followed the initial court-watching and door-knocking campaign, volunteers examined

the outcomes of the 621 cases identified as resulting in a tenant default using MassCourts. The available

records were reviewed to collect the following data points:

1. How many tenants filed a Motion to Remove Default and their rate of success;

2. How many defaults were removed, irrespective of whether a Motion was filed;

3. How many tenants agreed to vacate or had executions issued against them, even when

a default had been removed; and

4. How many tenants retained possession by order of the court or by entering into an

agreement that granted them possession after the default was removed.

7

Interview Findings

Volunteers successfully interviewed tenants in 123 out of the 621 cases identified where a tenant was

defaulted. Tenants who were interviewed were divided into two broad categories: those who made it to

the courthouse and those who did not. The following section describes the reasons for default reported

by tenants.

Tenants who did not make it to court and were defaulted

Most of the tenants we interviewed – 106 of the 123 tenants interviewed – never made it to court.

Analysis of these interviews reveals a number of significant and recurring themes. The chart below

shows each reason for default identified by tenants and the number of tenants who cited each as the

primary reason they were defaulted. Even where not identified as a primary reason, challenges posed by

transportation, lack of childcare, medical conditions, and disabilities were cited by many respondents as

barriers to accessing the court.

The most-cited primary reason tenants did not make it to court was that they had not received a

Summons and Complaint. Although the reasons tenants may not have received the Summons and

Complaint varied, it was consistently identified as a barrier. While some of these tenants had previously

received a bill for rent due or a notice to quit, many had no idea that a case had been filed in court.

Prior to pandemic-related changes, the Summons and Complaint form was the only official court

communication notifying tenants about their court hearing, including critical information such as the

date, time, and location of the trial. During the COVID-19 emergency, housing courts began sending

tenants a notice of first virtual court event (“first tier event”) that includes the date, time, and Zoom

login information. While this additional notice to tenants was welcome, it has unfortunately not been

effective for many tenants because notices are not always sent timely. Many tenants and attorneys

reported receiving this notice very shortly before or even after the court event, when it was too late.

8

The second most cited primary reason for default was that tenants had paid what they owed and

believed they did not need to appear in court. This reason is closely related to the third most common

reason, which was that tenants were affirmatively told that they did not need to attend court. This

information was often relayed to the tenant by a landlord or property manager, sometimes even in

writing, typically because the tenant had paid what was owed. Because the majority of eviction cases

are filed for non-payment of rent, it is significant that nearly 30% of tenants surveyed reported that they

had paid what they owed but were still saddled with a default judgment. These tenants may have

defaulted precisely because they paid and were led to believe that their presence in court was not

necessary. It is noteworthy that for certain tenants, their presence may not in fact have been required,

as a legal cure would require the landlord to dismiss the case.

The fourth most cited primary reason for default was a disability or medical issue. One tenant had

undergone a series of unexpected surgeries resulting from a recent cancer diagnosis. She knew that her

household had fallen behind on rent but was not aware that an eviction case had been filed and did not

recall receiving a letter from court due to her sudden illness and extensive treatment. Barriers cited by

other tenants included chronic illness, mobility difficulties, mental health challenges, and family deaths.

Some tenants experienced medical emergencies, including a tenant who fell and hit her head, requiring

stitches on the morning of her hearing, and another whose elderly mother fell down the stairs before

court. Both of these tenants called the court in the morning but were not given realistic options and

were defaulted.

One tenant who called the court prior to the hearing was told there was nothing the court could do and

that the tenant could file a motion to remove the default later. This cavalier response diminishes the

real harm that is inflicted on tenants who default, implying that simply “filing a motion” will put tenants

back into the position they had been in if they had appeared in court. Tenants must be informed of the

many steps required to remove a default. The court must explain tenants are on a short deadline, what

motion to file and how to file it, and what that motion must include. The standard for successfully

overcoming a default is quite high, and the court’s own standardized form does not clearly articulate

what a tenant must demonstrate to prevail in such a motion.

The SJC recently recognized the difficulties litigants with disabilities face, explicitly confirming that

Massachusetts Trial Courts must provide reasonable accommodations to litigants with disabilities. In

Adjartey v. Housing Court Central Division, the Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) highlighted the “complex

and fast-moving” nature of summary process cases, which pose particular difficulties for unrepresented

litigants, noting that the overwhelming majority of tenants appear in summary process cases without

attorneys.

6

Citing the Massachusetts Court System ADA Accessibility Policy, the SJC noted the duty

“where reasonable to ‘provide appropriate aids and services to qualified persons with disabilities so they

can participate equally in the services, programs, or activities of the Judiciary.’”

7

Unfortunately, there is

a lack of transparency about how litigants can request reasonable accommodations, and some courts do

not fully honor these requests.

6

Adjartey v. Central Division of the Housing Court Department, 481 Mass. 830 (2019), available at

http://masscases.com/cases/sjc/481/481mass830.html

7

Id. at 849

9

Recent pandemic-era changes have also exacerbated access issues for litigants with disabilities. One of

the emergency Housing Court provisions implemented in 2020 was the near-exclusive use of the Zoom

platform for hearings. This has posed different and additional challenges for disability access to the

court system, ranging from technology, literacy, and physical challenges.

The fifth most cited reason for default was that respondents had inaccurate information about the date,

time, or location of court. Some of these tenants had received the court papers but were still unclear

about this information. Several tenants who did not know their court date reported that, although they

were aware a court case had been filed, they had been communicating with their landlords (or property

managers) and were getting confusing, conflicting or misleading information about the case.

Difficulties with work or childcare were the sixth and seventh most cited reason for default. Several

respondents were unable to take time off work, and one could not find a babysitter for an autistic child

who had a school vacation the day of court.

“I went to the office and the manager told me since I

had paid, I did not need to go to court.”

— Tenant response as recorded by Default Project volunteers

10

Tenants who made it to court but were defaulted

There were 17 additional respondents who actually made it to court but were nonetheless defaulted.

Some of these respondents arrived within an hour of the start of the court session – some within 15

minutes – but were still defaulted. One of those tenants arrived early, was directed by a court staff

person to wait at a certain hallway in the courthouse, where he waited for one hour for his name to be

called. After speaking to another tenant in the hallway he went into a courtroom (which was on a

different floor) and was told he had been defaulted and that the landlord’s attorney had left. Other

tenants arrived and did not find the courtroom but met their landlord’s attorneys or accessed other

resources (such as RAFT, or Residential Assistance for Families in Transition). While the availability of

resources is important for litigants, once a default judgment has been entered it generally remains there

unless the court orders it removed or removal is specified in an agreement. This means the landlord

could still get an execution and move the tenant out, and the judgment could remain on the tenant’s

record, potentially affecting future access to credit or rental housing.

Some of the tenants who made it to court were delayed because of transportation problems. Two

tenants had car trouble or no car available and walked to court (one with her daughter). One tenant was

late because her train stopped running. Two tenants went first to the wrong courthouse; one of these

tenants stated that he went to the courthouse listed on the Summons and Complaint (which lists the

primary courthouse for the division) when in fact his case was being heard in a “satellite” session. One

tenant was sick with food poisoning and went to court later in the afternoon, as soon as she was able,

but had been defaulted. Another tenant’s children were sick the day of court, so she had to find

childcare, then spent half an hour looking for parking.

“The court officer told me told me to go to the 3rd floor.

I waited for almost an hour for my name to be called. I

spoke to another tenant in the hallway who told me to

check in inside the court room. When I went in, I was told

I had defaulted and the attorney already left.”

— Tenant response as recorded by Default Project volunteers

11

Case Outcome Findings

Case outcomes following a default

Beginning in 2020, the Default Project reviewed all the March 2019 cases where tenants were defaulted

to find out what, if anything happened in the case following the initial default. Specifically, the Default

Project wanted to learn how many of these cases concluded with default judgments and how many of

those defaults were successfully removed, if any. This research revealed that the vast majority of cases

concluded with the entry of a default judgment against a tenant, revealing that most tenants who

were defaulted lost possession and likely had to move out.

The court’s own data confirm that default judgments are rarely removed: a 2021 report by the Trial

Court Department of Research and Planning indicates that between 2017 and 2019, 93% of initial

default judgments were never removed, meaning that the final legal outcome of the case was a

default against the tenant.

8

Default process overview

Removing a default is time consuming and requires in-depth knowledge of Summary Process rules and

procedures – yet must happen quickly. Following the entry of a default a tenant has just 24 hours to try

to remove the default before a default judgment enters in the case. This means that only tenants who

were aware of their hearing date and can get to the court the same day or the following morning will

have any chance of removing the default before the court enters judgment against them. Once the court

has entered a default judgment the tenant may still seek to remove the default judgment, but they will

be subject to a higher standard of relief as set out in the Mass. R. Civ. Pr. 60(b), which is more difficult

than the “good cause” standard for motions to remove defaults before judgment has entered. If the

tenant fails to file a Motion to Remove Default within ten (10) days from entry of judgment, an

execution for possession and damages will be issued to the landlord, granting them authority to

physically remove the tenant. Although the court is required to mail notice of the entry of judgment to

the parties “forthwith,” the exact timing is not specified and same-day mailing is not required.

Weekends are not excluded from the 10-day window. Assuming three days for mailing, even a slight

delay in the tenant’s receipt of notice could result in the tenant having no idea they need to file a

motion until an execution has issued to the landlord and the sheriff or constable is serving a notice that

the tenant must move out in 48 hours. Many tenants do not receive this in time to take action, if they

receive it at all.

If a tenant is fortunate enough to know they missed a hearing date, they still face a series of barriers to

successfully removing a default. They must first be aware that they need to file a motion within a limited

time period. They must then find the correct motion to file and figure out how to file it with the court

and serve it on the landlord within the deadline. The motion must make specific legal arguments which

the tenant must be able to articulate at the hearing. A Motion to Remove Default will only be allowed

where the tenant successfully argues both good cause for failing to appear and that they have a

8

Report available at https://www.mass.gov/info-details/trial-court-statistical-reports-and-dashboards#statistical-

reports-

12

meritorious defense to the eviction. This means that a tenant with meritorious eviction defenses may be

denied the opportunity to advance them if, in a judge’s discretion, they did not have “good cause” for

failing to appear. Conversely, if a judge finds that a tenant has “good cause” for failing to appear but the

tenant is unaware of, or unable to articulate, their defenses, as is common for litigants unfamiliar with

summary process laws, they may still be denied the removal of default.

If a tenant fails to file a motion within the 10-day period allowed for filing a Motion to Remove Default

and is still in the unit, they will also need to seek a stay of levy of the execution to prevent the landlord

from moving them out before the Court can hear the motion.

Although the parties may choose to enter into an agreement following the entry of a default – either

before or after the judgment enters – landlords often have very little incentive to do so, since the tenant

has the sole burden for removing the default and the landlord has, or will soon have, the ability to

regain possession of the unit without incurring the time or expense of litigating the case.

Default Project case outcome findings

The Default Project review consisted of analyzing MassCourts case records for each of the 621 cases

recorded in March 2019 and noting the activity following the entry of the initial default.

Agreements between the landlord and tenant were reached in about 152 of the 621 cases, or 24%, most

of which required the tenant to move out. A small number of the case records, 30 of the 621, indicate

that the case was either dismissed, proceeded to further litigation, or were inconclusive. We further

analyzed two separate categories of cases: 1) outcomes of cases where tenants filed a motion to remove

the default and the outcomes, and 2) outcomes of cases where tenants reached an agreement with

their landlords. Our analysis found that tenants still lost possession in both circumstances.

1. Tenants who filed a Motion to Remove Default

Less than 20% of tenants who defaulted filed a Motion to Remove Default. Only 1/3 of those

tenants who filed a Motion to Remove Default were successful.

Tenants filed a Motion to Remove Default in only 118 of the 621, or 19%, of cases identified. Of

those, only about 34% of the 118 cases where a motion was filed resulted in a removal of the

default, either by the Court allowing the Motion or by the parties reaching an agreement in

which the default was removed.

2. Tenants who reached Agreements following the default.

About 1/4 of the cases where tenants were defaulted resulted in Agreements. Over half of

those cases resulted in the tenant losing possession.

Regardless of whether a Motion to Remove Default was filed, 152 of the 621 cases, or 24%,

resulted in some form of agreement following the initial default. These agreements were

reviewed to determine whether the terms addressed the tenant’s possession of the unit.

Tenants agreed to vacate their units in 60 of the 152 agreements (40%). Of the remaining 92

agreements, the overwhelming majority included terms allowing the landlord to regain

13

possession if the tenant failed to comply with certain conditions. Although such provisional

agreements theoretically provide tenants an opportunity to regain possession, tenants can be

quickly evicted if, upon the filing of a motion by the landlord, the court determines that the

tenant has violated a material term of the agreement. The court could immediately issue an

execution that the landlord can use to physically evict the tenant.

Landlords filed motions to issue execution in 22 of the 92 cases (24%) where agreements were

reached. Most of these motions for execution, 17 of 22 (77%), were allowed.

Taken together, the cases in which tenants agreed to vacate and those in which the court issued

an execution totaled 77 of 152 (51%), meaning that in over half of the cases where an

agreement was made following a tenant default, the tenant lost possession.

This review of available court records reveals a troubling outcome: out of the 621 cases in which a

tenant defaulted, only 103 tenant households, or 16%, appear to have retained possession; the

remaining 518 cases, about 84%, likely resulted in the tenant losing possession and moving out.

9

9

Although landlords are required to return an execution satisfied as to possession once a tenant vacates or is

removed by a constable or sheriff, this rarely happens in practice. Therefore, we cannot definitively state that

these households vacated or were removed, but what is certain is that at the conclusion of their case, they no

longer had a legal right to retain possession.

14

Policy Recommendations

Taken together, the interview and the case outcome findings reveal many significant barriers tenants

face in accessing the courts. Defendants in Housing Court eviction cases tend to be lower income,

exacerbating the challenges presented in getting to court, such as childcare, transportation,

employment, and disability related issues. In addition, the court process is confusing and fast-moving,

making it difficult for anyone unfamiliar with the process to navigate. In particular, the notices tenants

receive related to their eviction case include complex legal language, are written primarily in English,

and often are not received by tenants. Once a default has entered it is extremely difficult to remove it

without legal expertise. The result is that significant numbers of people lose their homes without the

opportunity to present their case or even to be heard.

In response to these devastating findings, Massachusetts Law Reform Institute and the Justice Center of

Southeast Massachusetts, with input from the Access to Justice Commission Housing Working Group,

crafted a series of recommendations aimed at reducing the default rate.

A note about COVID-19 policies:

While we were encouraged to see the courts adopt some of these recommendations during the COVID-

19 state of emergency, some of that progress has already been reversed as the pandemic wears on.

Recognizing that other policies may change, we present the original recommendations in full, and have

also included specific recommendation to address the recent standing orders, which we encourage the

court to either keep in place or reinstitute regardless of whether court operations are remote or in

person. Recommendations specific to the standing orders are indicated in italics.

1. Amend summary process procedures so that the initial court date is not a trial date.

▪ If the initial court date is a mediation or status date (not trial), amend rules so that

defendants cannot be defaulted on that date.

▪ During the COVID-19 State of Emergency, the Housing and District Courts took this

approach, instituting a “Tier 1” event as the first event where parties were sent to virtual

mediation on Zoom. Tenants could not be defaulted for missing a Tier 1 event; therefore,

even if a tenant did not receive notice of the Tier 1 event, or receive it timely, they had a

second opportunity to participate in their cases at the Tier 2 event before a judge.

Following the end of the State of Emergency, the Housing Court allowed defaults to be

entered at Tier 1, while the District Court continued with the pandemic-era policy of

declining to enter defaults at the mediation/case management stage. We recommend

that the Tier 1 event be made permanent, timely notice of the Tier 1 event be provided

to tenants, and that no default be permitted to issue at Tier 1. The Trial Court should

also examine the effect of holding virtual check-ins prior to court events and how it

affects the default rate, as well as potential disparate effects on certain tenants.

15

2. Amend Summons and Complaint form to include key information in plain language,

including:

▪ That tenants must appear in court regardless of what the landlord tells them or whether

they have paid any monies alleged to be owed

▪ The consequences of not appearing in court

▪ Disability access rights and information, including information about the court’s

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) coordinator

▪ Space for litigants’ telephone numbers to appear on the form so the court can send

automated messages to remind parties about court dates

▪ Instructions about how to look up case information on masscourts.org

3. Send tenants a separate communication about the trial date, including exact time and

specific location, well in advance of the hearing date.

▪ This notice should be combined with notice about available resources, including

potential access to counsel, and how to look up case information on masscourts.org

▪ The court should use text message reminders to notify parties of hearing dates. The

Housing Court has piloted an opt-in text message system, and other states have

successfully implemented text message reminders.

▪ Since the COVID emergency the court has been sending Summons & Complaint forms

with no date indicated, followed by a second notice of Tier 1 (first court) event with the

date, time, and Zoom information. However, these notices are sometimes sent too late

for tenants to attend the hearings.

4. Include a multilingual notice on all court correspondence. This should be in large font

and placed in a prominent location, stating that it is an important document and

should be translated.

5. Amend service of process to be more certain of receipt by requiring proof of mailing

and photographic proof of service.

6. Require landlords to show that tenants were properly served, for example, by

instituting a colloquy between landlord and court before default may enter; the Court

could inquire about whether or not tenants were properly served and may have

cured.

7. Require landlords to provide rent receipts to tenants that include notice that they still

need to appear in court unless the court has indicated otherwise.

8. Ensure courts honor requests for reasonable accommodation, and establish clear

protocols to address parties who contact the court with medical emergencies or

disability-related barriers.

▪ Ensure all courthouses and courtrooms are fully ADA accessible

▪ Ensure all courthouses and courtrooms have posted notices regarding disability access

rights, including contact information for the ADA coordinator

16

9. Establish easier navigation in all courthouses to ensure parties are in the correct

location.

▪ Provide clear signage, such as court information posted on a screen in multiple

languages

▪ Provide in-court navigators to assist parties in finding the correct courtrooms

10. Establish greater flexibility for parties to appear in court.

▪ Provide alternative days and times for court hearings; for example, evening hearings

▪ Make childcare available in courthouses where necessary, and ensure parties know they

may bring children to court

▪ Ensure that attorneys may appear for represented parties

11. Institute a “second call” of the case/docket list on court days.

▪ Some courts were using a second call prior to moving to all-remote hearings, which

helped reduce defaults

12. Provide support to community organizations and/or advocates to do outreach via

telephone, text, or canvassing to notify people about court dates

▪ Allow for more time between the entry of case and answer due date to enable outreach

13. Assist with transportation to court.

▪ Coordinate with local MBTA, RTA, The RIDE, Councils on Aging, or court-provided

options, to ensure transportation to court is available to those who require it

The following recommendations build upon recommendations made in the

Massachusetts Access to Justice Strategic Action Plan.

10

1. Establish procedures ensuring a default does not enter where parties arrive late if the opposing

party or their counsel is still in the building and that if counsel or party is no longer in the

building, they should be called to see if the case can proceed that day or be rescheduled to

another date.

2. Establish a court check-in system where a party’s presence is noted (possibly electronically) so

that even if a tenant is not in the courtroom when their case is called, they are not defaulted;

for example, if a tenant is getting help from the Lawyer for the Day Program, Tenancy

Preservation Program, or other day-of-court assistance.

3. Do not enter a default where one person in a household appears in court but the others do not,

and instead offer a one-week continuance for all defendants to appear

4. Make simple forms for removing defaults available, in multiple languages, in the clerk’s offices

and on the court’s website.

10

Massachusetts Access to Justice Strategic Action Plan (2017), pp 52 - 53, available at

www.massa2j.org/a2j/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Massachusetts-JFA-Strategic-Action-Plan.pdf

17

5. Call parties to ensure they have notice and opportunity to be heard where extraordinary relief

is being sought, such as a preliminary injunction or issuance of execution that would result in

speedy eviction.

Temporary Modifications to Court Operations Due to COVID-19

The following recommendations highlight some of the recommendations above and include additional

protections needed to prevent defaults as the court relies on virtual technologies during the COVID-19

crisis and beyond.

1. Translate all prompts to Zoom/telephonic hearings into multiple languages so that tenants are

not defaulted because they did not understand how to get into the virtual hearing room.

2. Establish a system where court staff checks in with parties before a hearing to prevent

confusion about hearing dates, deadlines, and next steps. A call from the court prior to

mediation or a court hearing would provide a party with a meaningful opportunity to request

an interpreter, access needed disability accommodations, and receive information about how

to contact legal services and housing assistance to help them access rental assistance funds.

3. Develop an effective first communication for tenants that includes information about where to

access other resources. While we appreciate the Court’s efforts in developing a resource sheet,

it should be simplified to provide basic information on how to access legal services, the

Tenancy Preservation Program, and housing stabilization resources and assistance. This

information must reach tenants well before their court date.

4. Enable tenants to file court forms from the online Massachusetts Defense for Eviction (MADE)

site directly to the Tyler system. MADE is a mobile-friendly website that helps tenants complete

their court Answer forms online; it is available in multiple languages and has been a critical tool

during COVID-19 allowing tenants to complete and file answers without going to a courthouse.

5. Extend the cure date for tenants to pay rental arrears to the date of the trial to enable tenants

more time to access rental assistance and stabilize housing.

6. If a tenant has not appeared for their first Zoom/telephonic hearing, include language in the

notice of the Tier 2 or next event that they can physically come to the courthouse if they do not

have Zoom or telephone access and the court will provide a way to access their hearing.

7. Ensure that attorneys may appear for litigants without the parties present; for example, when

a party does not have access to a computer, is unable to access Zoom, or does not have enough

minutes on their phone.

18

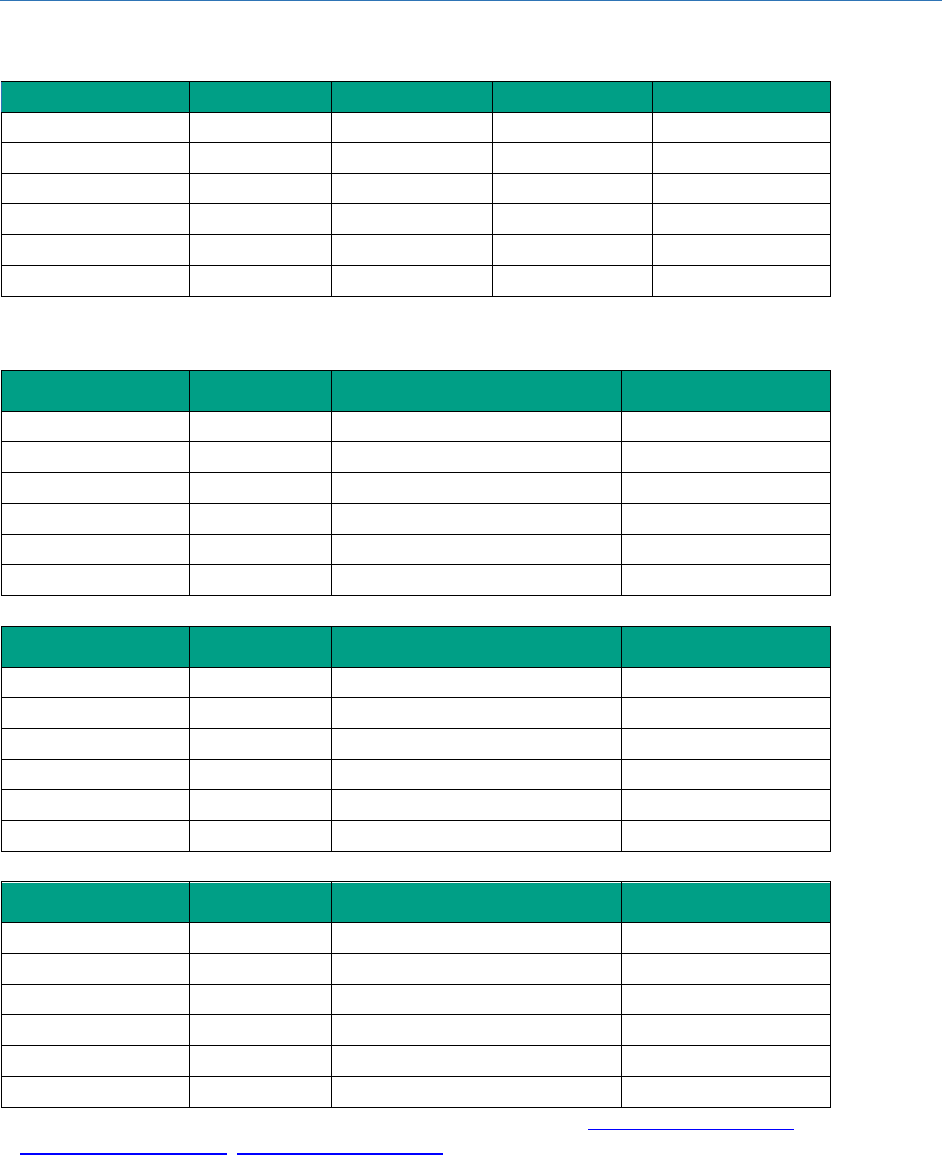

Appendix: Defaults in Summary Process Cases

FY 2015-2017

Disposed Summary Process Cases by Year of Disposition, “Judgment by default” FY2015 to FY2017,

Data compiled by the Executive Office of the Trial Court, July 10, 2018

Division/FY2017

2015

2016

2017

Total Defaults

Boston

1,157

1,168

1,253

3,578

Northeast

1,483

1,385

1,538

4,406

Southeast

1,483

1,469

1,509

4,461

Western

1,232

1,273

1,369

3,874

Worcester

1,409

1,403

1,408

4,220

Total

6,764

6,698

7,077

20,539

Percentage of Defaults FY2015 to FY2017

Analysis prepared by Massachusetts Law Reform Institute

Division/FY2015

Defaults

Total SP Cases Disposed*

% Defaults

Boston

1,157

6,054

19%

Northeast

1,483

5,642

26%

Southeast

1,483

5,988

25%

Western

1,232

5,469

23%

Worcester

1,409

5,404

26%

Total

6,764

28,557

24%

Division/FY2016

Defaults

Total SP Cases Disposed*

% Defaults

Boston

1,168

5,328

22%

Northeast

1,385

5,378

26%

Southeast

1,469

6,128

24%

Western

1,273

5,359

24%

Worcester

1,403

5,377

26%

Total

6,698

27,570

24%

Division/FY2017

Defaults

Total SP Cases Disposed*

% Defaults

Boston

1,253

5,445

23%

Northeast

1,538

5,732

27%

Southeast

1,509

6,067

25%

Western

1,369

5,669

24%

Worcester

1,408

5,181

27%

Total

7,077

28,094

25%

* Housing Court Department Filings and Dispositions by Court Location, Fiscal Year 2017 Statistics,

Fiscal Year 2016 Statistics, Fiscal Year 2015 Statistics.