ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Temporal factors in motor vehicle crash deaths

C M Farmer, A F Williams

...............................................................................................................................

See end of article for

authors’ affiliations

.......................

Correspondence to:

Charles M Farmer,

Insurance Institute for

Highway Safety, 1005

North Glebe Road,

Arlington, VA 22201–

4751, USA; cfarmer@

iihs.org

.......................

Injury Prevention 2005;11:18–23. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.005439

Objective: To summarize fatal motor vehicle crash deaths in the United States by time of day, day of week,

month, and season, and to determine why some days of the year tend to experience a relatively high

number of deaths.

Method: Crash deaths were identified and categorized using the Fatality Analysis Reporting System. Days

of the year with relatively high crash deaths were compared to the two days that occurred exactly one

week before and one week after.

Results: On average, motor vehicle crashes in the United States result in more than 100 deaths per day,

but there is much day-to-day variability. During 1986–2002 the single day fatality count ranged from a

low of 45 to a high of 252. Summer and fall months experience more crash deaths than winter and spring,

largely due to increased vehicle travel. July 4 (Independence Day) has more crash deaths on average than

any other day of the year, with a relatively high number of deaths involving alcohol. January 1 (New

Year’s Day) has more pedestrian crash deaths on average, plus it has the fifth largest number of deaths per

day overall, also due to alcohol impairment. On other days the high numbers of deaths are likely due to

increases in holiday or recreational travel.

Conclusion: Every day of the year results in many crash deaths, but certain days stand out as particularly

risky. The temporal and geographic spread of crash deaths, as well as the view of driving as a routine

task, inures the public to this continuing problem. Innovative strategies are needed both to raise awareness

and to work toward a solution.

M

otor vehicle crashes in the United States result in

more than 40 000 deaths per year. From 1975 to 2002

there were a total of 1 241 796 crash deaths, ranging

from a high of 51 093 in 1979 to a low of 39 250 in 1992.

1

On

average, more than 100 people are killed each day, but there

is a great deal of day-to-day variability. Weekend days tend to

result in more fatal crashes than midweek days, and summer

months experience more fatal crashes than winter months.

12

Fatal motor vehicle crashes are more prevalent during

holiday periods,

3–5

during which there is an increase in

recreational travel as people visit family and friends. Such

travel may involve long distances, unfamiliar roads, and high

speeds, all characteristics associated with increased crash

risk. Some recreational driving may involve alcohol. However,

this type of travel also may be concentrated on interstate

highways, which are by design much safer than other types

of roads.

This report chronicles the temporal patterns in motor

vehicle crash deaths during 1986–2002. In particular, the

days of the year that tended to have the highest fatality

counts are examined, as well as days with the lowest fatality

counts. This 17 year period was chosen specifically to balance

the effects of weekend travel. During this time period each

day of the week occurred exactly 887 times, and each day of

the year (except February 29) covered each day of the week at

least twice.

METHOD

Electronically coded descriptions of fatal crashes that

occurred during 1986–2002 were extracted from the United

States Department of Transportation’s Fatality Analysis

Reporting System (FARS). FARS is an annual census of

motor vehicle crashes occurring on public roads that result in

a fatality within 30 days. Information gathered includes date

and hour of the crash and characteristics of the vehicles and

people involved. For the study period all fatality records

contained information on the month of the crash, but 189

records did not have the exact date of the crash. Blood

alcohol concentration (BAC) is often reported for drivers and

pedestrians involved in fatal motor vehicle crashes. However,

during the period of this study, 29% of the fatally injured

drivers and 39% of the fatally injured pedestrians did not

have reported BACs. For cases in which BAC is not reported

the Department of Transportation uses a multiple imputation

procedure to obtain estimates, which are then included in

FARS.

6

Vehicle miles of travel on public roads, estimated

monthly, were obtained from the Federal Highway

Administration.

7

Motor vehicle crash deaths, categorized by month, day, and

hour of the crash, were averaged over the 17 year study

period. For some of the days with relatively high crash

deaths, deaths were categorized by role of the person killed,

age, BAC, and time of day. For comparison, the same

categorizations are given for the average of the two days that

occurred exactly one week before and one week after to

eliminate the confounding effects of season and day of the

week.

RESULTS

There were a total of 727 438 motor vehicle crash deaths in

the United States during 1986–2002. August averaged the

highest number of motor vehicle crash deaths per day (132)

during these 17 years (table 1). In fact, the six months with

the most fatalities (averaging 120 to 132 deaths per day) were

the summer and fall months, June through November.

January and February averaged the lowest number of deaths

per day (98); however, these two months also had the lowest

vehicle miles traveled per day. October and December

averaged the highest death rate per mile (19.1 deaths per

billion vehicle miles traveled), whereas March had the lowest

rate (16.4 deaths per billion vehicle miles traveled).

Abbreviations: BAC, blood alcohol concentration; FARS, Fatality

Analysis Reporting System

18

www.injuryprevention.com

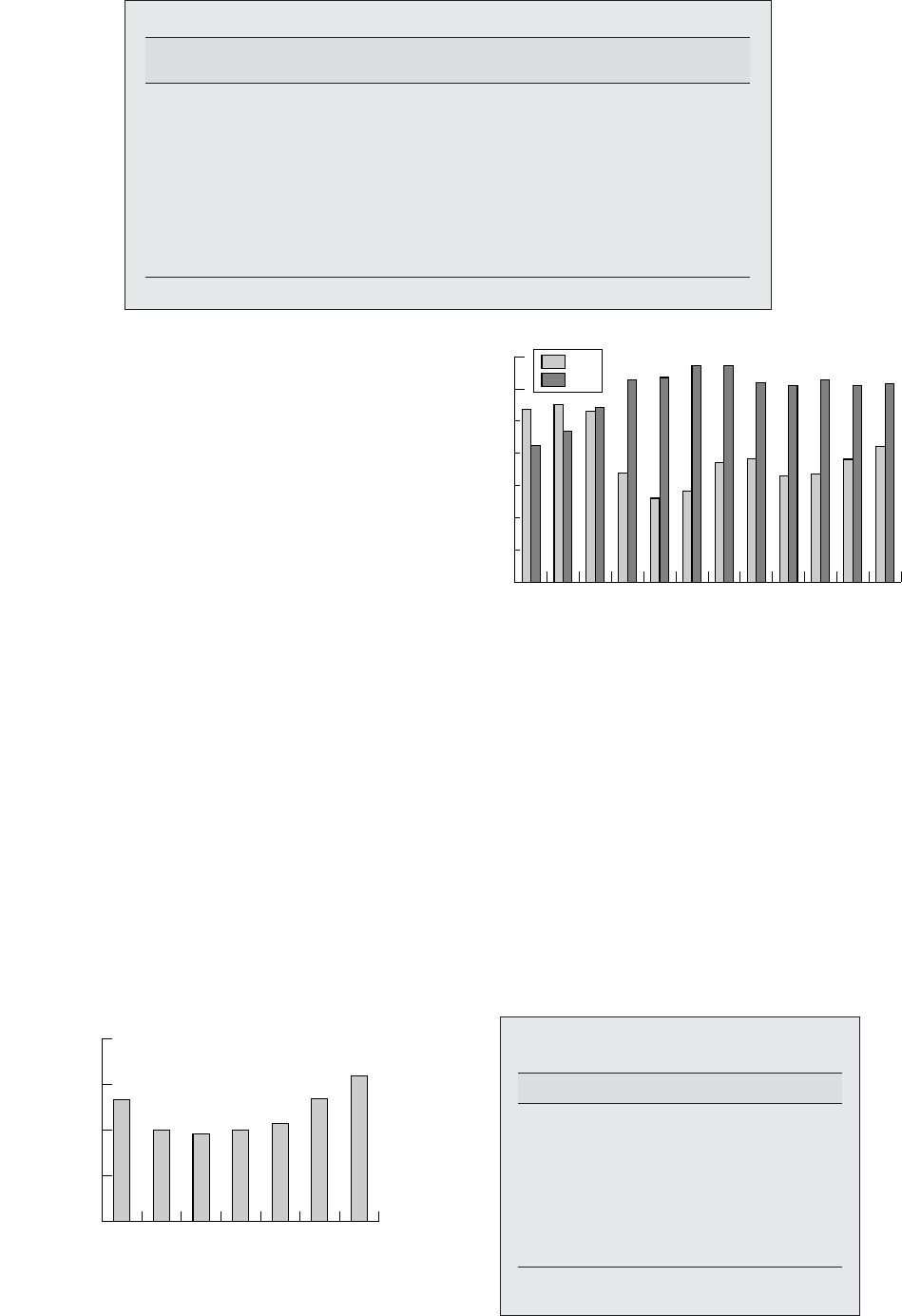

Saturday by far averaged the highest number of crash

deaths per day (158) (fig 1). Friday had the second highest

number of deaths, averaging 133 deaths per day, followed by

Sunday at 132 deaths. Tuesday averaged the fewest number

of deaths (95).

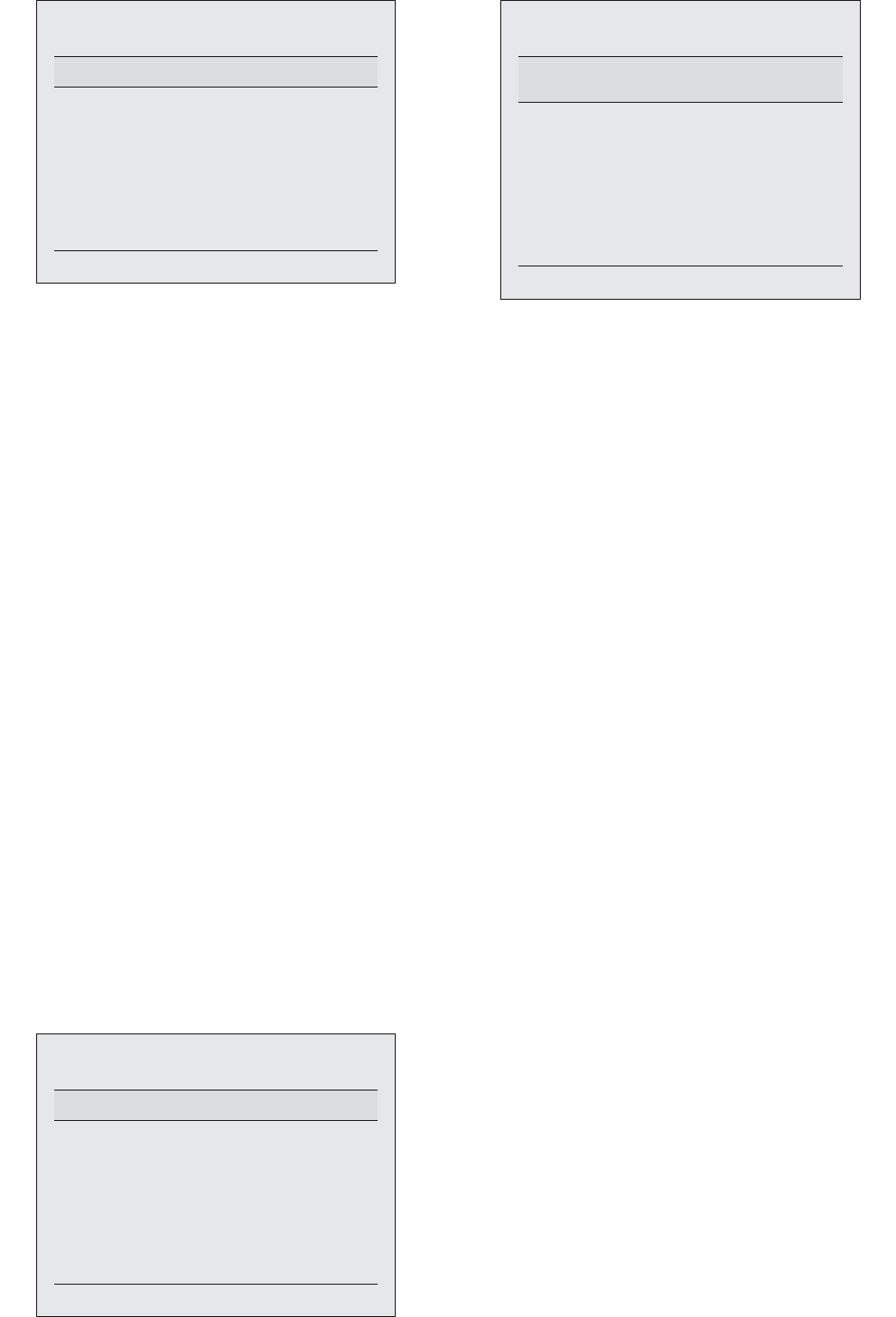

Crash deaths were highest during afternoon and evening

hours (fig 2). The hours between 5 pm and 7 pm had the

most fatalities, each averaging 6.6 deaths per hour. The

12 hours with the greatest number of fatalities occurred

between 2 pm and 2 am. The 4 am hour had the fewest

fatalities, with an average of 2.6 deaths.

The 10 days of the year with the highest number of crash

fatalities totaled over the 17 year period are listed in table 2.

July 4 (Independence Day), although rarely experiencing the

greatest number of deaths in any particular year, averaged

the highest number of crash deaths (161). July 3, only one

day earlier, averaged the second highest number of deaths

(149). Six of the 10 days with the greatest number of deaths

occurred near major American holidays: July 2–4, December

23 (Christmas), January 1 (New Year’s Day), and September

2 (Labor Day). The remaining four days were in August,

which had a greater amount of vehicle travel than any other

month (table 1). Another 10 days of the year averaged

between 135 and 137 deaths per day, and all were during the

months of August, September, October, and December. The

single date with the highest number of deaths during 1986–

2002 was Saturday, August 9, 1986 (252 deaths).

The 10 days of the year with the fewest number of crash

fatalities averaged between 91 and 94 deaths per day. All

occurred in January and February, the months with the least

amount of vehicle travel. January 8, with the fewest average

number of deaths per day (91), follows exactly one week

after January 1, one of the days with the highest number of

deaths (table 2). The single date with the lowest number of

deaths during 1986–2002 was Monday, March 2, 1992 (45

deaths).

Motor vehicle crash deaths result from a variety of crash

types. The majority of deaths (about 75%) are to occupants of

passenger vehicles (cars, pickup trucks, sport utility vehicles,

and passenger/cargo vans). Table 3 lists the 10 days of the

year with the most deaths to passenger vehicle occupants.

July 4 had the most passenger vehicle occupant deaths on

average (117), followed by December 23 (116) and January 1

(111).

Pedestrians account for about 13% of all crash deaths. The

days of the year with the most pedestrian deaths on average

were January 1 and October 31, each with about 24

pedestrian deaths per day (table 4). December 23 had the

next highest number of pedestrian deaths (22 per day). All of

the other days that averaged at least 20 pedestrian deaths

Table 1 Crash deaths by month of year, 1986–2002

Month VMT (in millions) Deaths

Deaths per billion

VMT

Average deaths per

day

January 2 996 148 51 694 17.3 98

February 2 860 326 47 247 16.5 98

March 3 32 7 688 54 645 16.4 104

April 3 327 528 55 710 16.7 109

May 3 534 141 62 426 17.7 118

June 3 525 655 64 152 18.2 126

July 3 657 624 68 099 18.6 129

August 3 676 891 69 731 19.0 132

September 3 365 709 63 965 19.0 125

October 3 476 625 66 553 19.1 126

November 3 237 169 61 145 18.9 120

December 3 257 765 62 071 19.1 118

VMT, vehicle miles traveled.

200

150

100

50

0

Average deaths per day

132

Sunday

98

Monday

95

Tuesday

98

Wednesday

105

Thursday

133

Friday

158

Saturday

Figure 1 Crash deaths by day of week, 1986–2002.

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

Hour beginning

am

Average deaths per hour

12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

pm

Figure 2 Crash deaths by hour of day, 1986–2002.

Table 2 Days of year with most crash deaths,

1986–2002

Date Deaths Average deaths per day

July 4 2743 161

July 3 2534 149

December 23 2470 145

August 3 2413 142

January 1 2411 142

August 6 2387 140

August 4 2365 139

August 12 2359 139

July 2 2340 138

September 2 2336 137

Note: Highest single day fatality count during this period was

252 on Saturday, August 9, 1986.

Temporal factors in motor vehicle crash deaths 19

www.injuryprevention.com

occurred during October, November, and December. The day

of the year that averaged the fewest pedestrian deaths was

March 12 (11 per day).

Motorcyclists account for about 7% of the total crash

deaths. Forty one percent of the motorcyclist deaths during

1986–2002 occurred during the summer months of June,

July, and August. The 10 days of the year with the most

motorcyclist deaths on average also were during the summer

(table 5). The day with the most motorcyclist deaths on

average was July 4 (18 per day). The day with the fewest

motorcyclist deaths on average was December 27 (two per

day).

Tables 6–9 summarize the results for some days with

relatively high crash deaths (July 4, December 23, January 1,

and August 6) as categorized by role of the person killed, age,

and BAC. Results are compared with those for the two days

occurring exactly one week before and one week after.

July 4 was the day of the year with the most deaths to both

passenger vehicle occupants and motorcyclists. It also had

more pedestrian deaths on average than either June 27 or

July 11 (table 6). As compared with June 27/July 11, July 4

had greater proportions of age groups younger than 30

among deaths to both passenger vehicle occupants (56% v

48%) and pedestrians (44% v 37%). For all three person

categories, July 4 had a greater proportion of deaths involving

high BACs than June 27/July 11 (41% v 31% overall).

December 23, the day with the second highest number of

passenger vehicle occupant deaths and the third highest

number of pedestrian deaths, did not exhibit different

patterns of passenger vehicle occupant deaths compared

with December 16 and 30 (table 7). Among pedestrians,

however, December 23 had greater proportions of deaths

involving high BACs (35% v 27%).

January 1 averaged the third highest number of passenger

vehicle occupant deaths and the most deaths among

pedestrians. New Year’s Day had more pedestrian deaths

than either December 25 or January 8 in each of the years

1986–2002. January 1 also had a much greater proportion of

deaths involving high BACs than December 25/January 8

(51% v 33% overall) (table 8). As might be expected, given the

increase in alcohol related deaths, January 1 also had more

deaths between midnight and 6 am than the comparison

days (48% v 20% overall).

August 6 is not close to any national holiday, but it was

among the days with the most deaths to both passenger

vehicle occupants (table 3) and motorcyclists (table 5). As

compared with the days one week before and after, August 6

was similar in the breakdown of deaths by age (table 9).

There were slight differences in the proportion of motorcyclist

deaths involving high BACs (40% v 35%). Overall, however,

August 6 was very similar to the comparison days.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study illustrate the large toll exacted by motor

vehicle crashes in the United States. However, not included

are the much more frequent non-fatal injuries, which average

more than 8000 per day, many of them severe.

1

It is not

surprising that there is substantial variation in numbers of

fatalities by day of week, time of day, and season, primarily

because driving exposure differs by these factors. One other

factor that affects the distribution of fatalities is alcohol

impairment, which is more frequent at night, on weekends,

and on certain days of the year. This helps explain why July 4

and January 1 were among the days with the most fatalities.

July 4 had on average at least 12 more crash deaths per day

than any other day of the year (table 2). Some of these

additional deaths may have been due to increased travel, but

a large part of it was likely due to alcohol impaired travel to

and from picnics, fireworks, and other recreational activities.

The proportion of deaths involving high BACs was much

higher on July 4 than on the comparison days one week

earlier and later.

December 23 was typical of other December days with

regard to who died and when they died. However, for

pedestrians at least there is some evidence of increased

alcohol impairment. Depending on the day of the week,

December 23 can be a high travel day or a day for

celebrations. So the reasons for the high number of crash

deaths on December 23 probably are a combination of

increased travel and alcohol impairment.

Almost half of the crash deaths on January 1 occurred

between midnight and 6 am, a period of light traffic on any

other day. Furthermore, half of the deaths involved alcohol

impairment. This percentage of high BAC deaths was

relatively high in each of the 17 years studied, ranging from

42% in 1995 (a Sunday) to 61% in 2000 (a Saturday). The

increased alcohol consumption due to New Year celebrations

especially affected pedestrians; 58% of the pedestrians dying

Table 3 Days of year with most passenger

vehicle occupant crash deaths, 1986–2002

Date Deaths Average deaths per day

July 4 1990 117

December 23 1975 116

January 1 1881 111

July 3 1873 110

December 24 1872 110

December 22 1776 104

August 3 1770 104

August 6 1755 103

August 4 1739 103

November 1 1733 102

Table 4 Days of year with most pedestrian

crash deaths, 1986–2002

Date Deaths Average deaths per day

January 1 410 24

October 31 401 24

December 23 373 22

December 20 357 21

November 2 351 21

October 26 350 21

November 3 348 20

November 10 344 20

November 1 340 20

December 18 339 20

Table 5 Days of year with most motorcyclist

crash deaths, 1986–2002

Date Deaths

Average deaths

per day

July 4 303 18

July 19 266 16

July 5 247 15

July 16 246 14

August 1 243 14

August 6 243 14

August 9 243 14

June 28 242 14

July 2 240 14

August 25 239 14

20 Farmer, Williams

www.injuryprevention.com

had a high BAC. This accounts for January 1 having more

pedestrian deaths than any other day of the year.

August 6, along with several other days in August, had

relatively high numbers of passenger vehicle occupant and

motorcyclist deaths. However, the pattern of deaths on

August 6 was similar to that of deaths that occurred one

week earlier or later. The increased number of deaths on

August 6 was therefore probably due to increased recrea-

tional travel.

Six of the 10 days with the highest number of crash deaths

occurred during holiday periods. Recognizing this trend,

police agencies sometimes initiate traffic enforcement cam-

paigns during holiday periods. Such campaigns, when well

publicized, have been shown to temporarily reduce crash

rates, especially those involving alcohol.

89

Safety organiza-

tions also warn of the dangers of holiday travel, but this

overlooks the reality that every day of the year results in

many motor vehicle deaths. That is, on each of the 6209

consecutive days included in this study, an equivalent of a

plane-load or more of people died on the roads.

There is not a large public outcry concerning this daily loss

of life. Motor vehicle crash deaths are ‘‘statistical’’ deaths

that, except for the occasional spectacular crash, do not

resonate with the public.

10

The highest number of people

killed in a motor vehicle crash during the study period was 27

on Saturday, May 14, 1988. This particular crash, in which a

driver with a measured BAC of 0.24% struck a busload of

children, sparking a catastrophic fire, received nationwide

attention. However, most deaths (94%) occurred in crashes in

which one or two people were killed, and these were

scattered throughout the country. Daily tallies of fatal crashes

in the United States are not available until many months

have passed.

Motor vehicle crashes and injuries are often acknowledged

to be a social problem, but part of the public indifference may

reflect the fact that almost everyone is a driver. Risk

perception research suggests that people create ‘‘illusory

zones of immunity’’ around routine, everyday activities that

are supposed to be under their control.

11

Related to this is the

belief held by most people that their driving skills are better

than those of others.

12

Thus although motor vehicle crashes

may be recognized as a social problem, it is one that may be

perceived as not particularly affecting them. Whatever the

case, there exists a kind of public apathy about motor vehicle

injuries, one result of which is that motor vehicle injury

prevention efforts are woefully underfunded compared with

other public health problems.

13

These influences, however, can be overcome. Sweden, for

example, adopted an approach called ‘‘Vision Zero’’ in 1997,

with the ultimate goal of no fatal or serious injuries on the

road. Included among Vision Zero principles are that the

objective of a transport system is to move people without

causing serious injury, there is no place for trade-offs

between fatalities and benefits such as faster travel, and

people have the responsibility to drive properly but should

not sustain injury if they do not.

14

Intervention components

of Vision Zero include traffic calming in congested areas,

reducing speeds to within the limits of vehicle crashworthi-

ness, and separating vehicle traffic on two lane roads with

cable barriers. Other countries have adopted similar strate-

gies. The Netherlands has begun a ‘‘Sustainable Safety’’

program, based on the principles of functional, homoge-

neous, and predictable use of the road network by all

parties.

15

In other words, roads must be designed so as to

promote cooperation among road users, and enforcement of

traffic rules should ensure that cooperation.

Table 6 Percentage of crash deaths by age and blood alcohol concentration (BAC), July

4 and comparison days, 1986–2002

Date

Age (years) BAC (%)*

0–29 30–54 55+ 0 0.01–0.07 0.08+

Passenger vehicle July 4 56 30 15 52 7 40

occupants June 27/July 11 48 30 23 63 6 31

Pedestrians July 4 44 37 18 53 4 43

June 27/July 11 37 34 28 61 4 35

Motorcyclists July 4 51 43 7 43 11 47

June 27/July 11 51 44 5 49 10 41

All deaths July 4 54 32 14 52 7 41

June 27/July 11 47 32 21 62 6 31

*BAC imputed for drivers and pedestrians; for passenger deaths, BAC of driver was used.

Table 7 Percentage of crash deaths by age and blood alcohol concentration (BAC),

December 23 and comparison days, 1986–2002

Date

Age (years) BAC (%)*

0–29 30–54 55+ 0 0.01–0.07 0.08+

Passenger vehicle December 23 42 34 24 63 5 32

occupants December 16/

December 30

43 32 25 63 5 32

Pedestrians December 23 21 39 39 60 5 35

December 16/

December 30

28 32 39 68 5 27

Motorcyclists December 23 63 34 3 56 5 39

December 16/

December 30

42 54 4 54 11 35

All deaths December 23 39 35 26 63 5 32

December 16/

December 30

41 33 26 64 5 31

*BAC imputed for drivers and pedestrians; for passenger deaths, BAC of driver was used.

Temporal factors in motor vehicle crash deaths 21

www.injuryprevention.com

The World Health Organization has recently focused

attention on motor vehicle injuries by devoting World

Health Day 2004 to road safety and publishing an extensive

report on road traffic injury prevention.

16

Among the

interventions recommended by the report are proposals for

increasing ‘‘the visibility of vehicles and vulnerable road

users’’. Visibility seems to be a particular problem for

pedestrians in the United States. The days of the year with

the most pedestrian deaths during 1986–2002 occurred

between late October and early January, precisely the season

with the least amount of daylight. Encouraging pedestrians

to wear colorful clothing and to use designated crosswalks

has little effect on adults, especially those with their

judgment impaired by alcohol. Instead, municipal govern-

ments should concentrate on increasing the illumination of

streets and sidewalks near restaurants, bars, shops, and other

areas catering to pedestrians.

The days of the year with the most motorcyclist

deaths during 1986–2002 were all during the summer,

when the weather is more accommodating of two wheeled

vehicles. Good weather can also encourage motorcyclists

(and other motor vehicle operators) to increase their speed.

Motorcyclist fatalities have been increasing in the United

States in recent years, with excessive speed cited as a major

factor.

17

Other factors include alcohol use, lack of proper

licensure, and failure to wear helmets. Thus the most

effective strategies for reducing motorcyclist deaths would

seem to be a strengthening of laws regarding speeding,

alcohol limits, licensure, and helmet use, along with

increased enforcement.

Passenger vehicle occupant deaths tend to increase during

periods of increased recreational travel. This type of travel

may involve alcohol use and excessive speed, so again

increased law enforcement is needed. Such travel, however,

could also involve rural roads, driver distractions, and

fatigue. As these factors increase the likelihood of driver

error, it is essential for all roadways to have well lit and easily

understood traffic signs. Driver error can never be completely

eliminated, so roadside hazards such as trees and utility poles

should be removed or cushioned. Finally, efforts to increase

both the crash avoidance capability and crashworthiness of

passenger vehicles should be continued.

Table 8 Percentage of crash deaths by age and blood alcohol concentration (BAC),

January 1 and comparison days, 1986–2002

Date

Age (years) BAC (%)*

0–29 30–54 55+ 0 0.01–0.07 0.08+

Passenger vehicle January 1 54 33 13 42 8 50

occupants December 25/

January 8

44 32 23 62 5 33

Pedestrians January 1 34 41 24 37 5 58

December 25/

January 8

24 38 36 57 5 38

Motorcyclists January 1 64 34 2 45 7 48

December 25/

January 8

54 41 5 53 6 42

All deaths January 1 51 35 14 42 7 51

December 25/

January 8

42 33 24 62 5 33

*BAC imputed for drivers and pedestrians; for passenger deaths, BAC of driver was used.

Table 9 Percentage of crash deaths by age and blood alcohol concentration (BAC),

August 6 and comparison days, 1986–2002

Date

Age (years) BAC (%)*

0–29 30–54 55+ 0 0.01–0.07 0.08+

Passenger vehicle August 6 47 30 23 60 6 34

occupants July 30/August 13 47 31 22 60 6 34

Pedestrians August 6 40 31 28 62 4 35

July 30/August 13 37 35 27 60 6 35

Motorcyclists August 6 51 44 5 52 8 40

July 30/August 13 54 40 5 53 12 35

All deaths August 6 47 32 21 60 6 34

July 30/August 13 47 33 20 60 6 33

*BAC imputed for drivers and pedestrians; for passenger deaths, BAC of driver was used.

Key points

N

During the years 1986–2002 there were on average

117 deaths per day in motor vehicle crashes in the

United States.

N

There was a great deal of day-to-day variability in

motor vehicle crash deaths, ranging from a low of 45

to a high of 252.

N

Certain seasons (summer, fall), days of the week

(Saturday, Friday, Sunday), and times of day (after-

noon, evening) had high concentrations of crash

deaths.

N

July 4 had on average at least 12 more crash deaths

than any other day of the year, and many of these

involved alcohol.

N

January 1 had more pedestrian crash deaths than any

other day of the year, and more than half of these

involved alcohol.

22 Farmer, Williams

www.injuryprevention.com

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Insurance Institute for Highway

Safety. The authors thank Anastasios Markitsis for his assistance

with the data processing.

Authors’ affiliations

.....................

C M Farmer, A F Williams, Insurance Institute for Highway Safety,

Arlington, Virginia, USA

REFERENCES

1 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic safety facts, 2002.

Report No DOT-HS-809-620. Washington, DC: US Department of

Transportation, 2004.

2 Cerrelli EC. Crash, injury, and fatality rates by time of day and day of week.

Report No DOT-HS-808-194. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic

Safety Administration, 1995.

3 Arnold R, Cerrelli EC. Holiday effect on traffic fatalities. Report No DOT-HS-

807-115. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration,

1987.

4 Harms PL. Driver-following studies on the M4 motorway during a holiday

and a normal weekend in 1966. Report No RRL-LR136. Crowthorne,

Berkshire, UK: Road Research Laboratory, 1968.

5 National Safety Council. Independence Day holiday period traffic fatality

estimate, 2003. Itasca, IL: National Safety Council, 2003. Available at:

http://www.nsc.org/public/issues/indday03.doc (accessed 28 October

2003).

6 Subramanian R. Transitioning to multiple imputation: a new method to impute

missing blood alcohol concentration (BAC) values in FARS. Report No

DOT-HS-809-403. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety

Administration, 2002.

7 Federal Highway Administration. Traffic volume trends. Washington, DC,

2003. Available at: http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/tvtw/tvtpage.htm

(accessed 29 October 2003).

8 Agent KR, Green ER, Langley RE. Evaluation of Kentucky’s ‘‘You drink and

drive, you lose’’ campaign. Report No KTC-02-28. Lexington, KY: Kentucky

Transportation Center, 2002.

9 Ross HL. Britain’s Christmas crusade against drinking and driving. J Stud

Alcohol 1987;48:476–82.

10 Jenni KE, Loewenstein G. Explaining the ‘‘identifiable victim effect’’. J Risk

Uncertain 1997;14:235–57.

11 Douglas M. Risk acceptability according to the social sciences. New York:

Russell Sage Foundation, 1985.

12 Williams AF, Paek NN, Lund AK. Factors that drivers say motivate safe driving

practices. J Safety Res 1995;26:119–24.

13 Institute of Medicine. Reducing the burden of injury. Washington, DC:

National Academy Press, 1999.

14 Tingvall C, Haworth N. Vision Zero: an ethical approach to safety and

mobility. Paper presented to the 6th Institute of Transportation Engineers

international conference on road safety and traffic enforcement: beyond

2000. Melbourne: 6–7 September, 19 99. Available at: http://

www.general.monash.edu.au/muarc/viszero.htm (accessed 28 April 2004).

15 Koornstra M, Lynam D, Nilsson G, et al. SUNflower: a comparative study of

the development of road safety in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the

Netherlands. Leidschendam, Netherlands: SWOV Institute for Road Safety

Research, 2002.

16 Peden M, Scurfield R, Sleet D, et al, eds. The world report on road traffic injury

prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004.

17 Shankar U. Recent trends in fatal motorcycle crashes. Report No DOT-HS-

809-271. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration,

2001.

LACUNAE ...........................................................................................................

Clothing related burn injuries to children

T

he first full year of data from the US CPSC National Burn Center Reporting System,

published in October, showed that gasoline and other flammable liquids are frequently

involved in clothing related burns to children. In a new report, CPSC staff reviewed 209

children’s clothing burn injury reports received from March 2003 through June 2004 and

found that more than one half involved gasoline or other flammable liquids. Developed in

cooperation with the American Burn Association and Shriners Hospitals for Children, the

CPSC’s National Burn Center Reporting System collects comprehensive reports on clothing

related burns to children under age 15 from the 105 burn centers that treat children. These

incidents involve the ignition, melting, or smouldering of clothing worn by children. To

support this effort, the National Association of State Fire Marshals works cooperatively with

CPSC to retrieve and preserve children’s clothing involved in burn injuries—an action that

greatly enhances the investigative process. Garments collected by fire officials are forwarded

to CPSC headquarters for inspection. At the suggestion of the NASFM, a committee

consisting of the National Volunteer Fire Council, National Fire Protection Association, the

International Association of Fire Chiefs, and NASFM developed a protocol for use by ‘‘first

responders’’ across the country. For each incident reported, the burn center provides CPSC

with preliminary information on the incident. A CPSC investigator is assigned to the case to

conduct an in-depth investigation, interviewing the victim when possible, as well as parents,

fire officials, and medical personnel. All reports are reviewed and maintained in CPSC’s

epidemiological databases. The report, which can be downloaded from http://www.cpsc.gov/

cpscpub/prerel/prhtml05/05028.pdf, highlights that of the 213 victims, 179 were injured

while wearing daywear. No incidents appear to have involved tight fitting children’s

sleepwear or infant garments sized 9 months or smaller. The most frequent ignition source

was an outdoor fire, involved in 62 of the 209 incidents, followed by lighters in 37 of the

incidents. More than one half (107) of the 209 incidents involved flammable liquids. Boys,

ages 10 to 14, comprised most of the victims. Many of these incidents were also associated

with outdoor fires. Gasoline was the most frequently reported flammable liquid involved in

these incidents.

Temporal factors in motor vehicle crash deaths 23

www.injuryprevention.com